Abstract

Research has shown that multinational enterprises (MNEs) manage international boycotts by demonstrating commitment to shared social values. However, international boycotts often revolve around contentious issues and values that are not universally embraced, requiring firms to implement different strategies to maintain legitimacy across markets. This paper analyses Volkswagen’s management of the Arab League boycott of Israel to develop a typology of MNEs’ management strategies for international boycotts. The Arab League boycott posed a business dilemma: non-compliance endangered revenues in Arab League member states, but compliance risked counterboycotting in the US and Israel. Analysis of corporate and federal archives reveals that Volkswagen used three overarching strategies: prevention, delay, and negotiation. Volkswagen first camouflaged its engagement in Israel to prevent the boycott. When facing the boycott threat, Volkswagen pursued delaying strategies to create room for negotiations with actors from home, host, and third countries that eventually preserved the firm’s legitimacy across markets.

1. Introduction

Boycotts are generally defined as attempts by social movements, governments, and supranational organisations to exclude a targeted party from a market for political and ethical reasons (Feldman, Citation2019; Friedman, Citation1999; Hawkins, Citation2010). Research in business history has treated boycotts as a type of social risk that multinational enterprises (MNEs) have to manage on foreign markets (Bucheli & DeBerge, Citation2024; Casson & da Silva Lopes, Citation2013). Strategies used by MNEs to counter boycott threats have included corporate social responsibility activities in the home market (Glover, Citation2019; Levy, Citation2020), the creation of counternarratives at various levels of the organisation (Minefee & Bucheli, Citation2021), and the establishment of dialogue platforms with boycotters (Pitteloud, Citation2023). Although these strands of research focus on consumer boycotts, boycotts can also be used as an economic weapon by governments when other forms of state power are limited, constrained, or absent (Trentmann, Citation2019).

In recent years, the use of international boycotts as economic weapons by governments has increased in scale, scope, and frequency. US- and EU-led sanctions against Russia and escalating US–Chinese tensions have prompted research in international business (IB) to investigate MNEs’ strategies for managing sanctions and international boycotts (Meyer et al. Citation2023).Footnote1 This research has found that firms have implemented ‘low-profile’ strategies to reduce visibility and commitment in contentious host markets (Meyer & Thein, Citation2014) and completely divested from such markets (Soule et al. Citation2014). To defy boycotts, firms have negotiated with home and host governments (Li et al. Citation2022) and increased their prosocial claims in public relations campaigns to signal their adherence to shared social values in the home market (McDonnell & King, Citation2013).

Public relations campaigns may work well if boycott movements target MNEs for violating widely shared social values, such as MNEs’ involvement in countries with poor human rights records. However, international boycotts often involve highly contentious political and ethical aims that may not be universally embraced by all actors across home, host, and third countries (Li et al. Citation2022; Mohliver et al. Citation2023). For instance, during the 2006 ‘cartoon crisis’, the Danish MNE Arla faced boycotts in the Middle East. In response, the firm launched public relations campaigns in Dubai and Saudi Arabia and signed declarations that the firm would not do business with Israel. Yet, Danish politicians and consumers perceived the firm’s actions as violating Danish values, resulting in boycotts, reputational damage, and sales losses in Arla’s home market (Jensen, Citation2008; Mordhorst, Citation2014). Thus, even when firms’ actions align with the laws and values of one market, they may still evoke objections in others (Casson & da Silva Lopes, Citation2013; Lubinski, Citation2014). In such cases, international firms face the threat of cross-border legitimacy spill-overs: situations in which their actions in one market affect their revenues, reputation, and legitimacy in others (Kostova et al. Citation2008; Kostova & Zaheer, Citation1999; Sun et al. Citation2021).

When the political and ethical reasons associated with a boycott are disputed, we expect that MNEs need to implement sets of different strategies to manage boycotts and preserve their legitimacy across all markets. For example, theoretical research suggests that firms facing competing institutional demands may refrain from completely complying with the demands of one market and instead opt for strategies of partial compliance to retain their legitimacy in both home and host markets (Li et al. Citation2022). Despite increasing academic attention to international boycotts, analyses, particularly long-term ones, of firms managing contentious boycotts are lacking. This gap is significant because, as this paper shows, boycotts can have a lasting impact, affecting corporate decision-making even long before boycotts have been implemented (Meyer et al. Citation2023). A historical perspective is useful to address this gap. Because decision-making in polarised environments is highly sensitive, firms avoid open discussions of their strategies, making it difficult for IB scholars to observe firms’ decision-making processes. By using archives, historians can gain access to previously classified internal documents that open the black box of firms’ internal strategy-making (Bucheli & DeBerge, Citation2024; Meyer et al. Citation2023).

To analyse how MNEs managed international boycotts, this paper focuses on one of the largest international boycott campaigns of the twentieth century: the Arab League boycott of Israel (Hawkins, Citation2010). The Arab League boycott posed a unique business dilemma. Member states of the Arab League proscribed any trade between their countries and Israel in a primary boycott, boycotted businesses with commercial relations to Israel in a secondary boycott, and banned firms from establishing partnerships or joint ventures with blacklisted firms in a tertiary boycott. Non-compliance with the Arab League boycott threatened sales in member states of the Arab League, and firms became tainted in the eyes of other organisations because of the tertiary boycott, causing organisations to avoid business relations with boycotted firms due to fears of association (Fershtman & Gandal, Citation1998; Turck, Citation1977). However, firms bowing to the boycott became subject to counterboycott threats by the Israeli government and Jewish interest groups in the US that endangered firms’ revenues and reputation in key sales markets (Labelle, Citation2014). To avoid these risks, the majority of international firms either voluntarily abstained from exporting to Israel or stayed away from Arab League markets (Turck, Citation1977). However, some firms successfully sold their products in both markets.

One of the firms selling in both markets was the West German automotive firm Volkswagen (VW), whose national origin likely influenced its strategies in the Middle East. Recent business history literature has highlighted the importance of both host and home country actors and emphasised the significance of MNEs’ national origin in shaping firms’ strategies (Glover, Citation2019; Lubinski, Citation2014; Reckendrees et al. Citation2022). Although all MNEs face a liability of foreignness on international markets (Zaheer, Citation1995), a firm’s national origin influences consumers’ perceptions of the firm, its ability to seek diplomatic support from the home government, and may be exploited by firms as strategic asset. For example, Lubinski and Wadhwani (Citation2020) have shown how German MNEs engaged in ‘geopolitical jockeying’ in late colonial India. Capitalising on the Indian boycott of British products, German firms leveraged their national background as a strategic advantage to position themselves as natural competitors to British producers. Thus, the nationality of an MNE can either be an asset or liability and this may vary over time and depend on the political and cultural context of the home and host countries (Lubinski, Citation2014; Lubinski & Wadhwani, Citation2020; Reckendrees et al. Citation2022).

Due to its national origin, VW presents a particularly puzzling case. Although German products were first boycotted and later stigmatised in Israel (Tovy, Citation2020), VW was among the first international automotive firms to export its cars to Israel in 1960. By the mid-1960s and early 1970s, the Beetle had become the most successful import car in Israel, and, in turn, Israel VW’s most important export market in the MENA region.Footnote2 While enjoying success in Israel, the firm faced the threat of an Arab League boycott twice, first in 1964 and later from 1969 to 1977. Because VW was arguably ‘the most German of all German industrial institutions’,Footnote3 the firm’s behaviour in Israel and its response to the Arab League boycott threat attracted international attention in light of the company’s nationality and Nazi past (Kaikati, Citation1978; Turck, Citation1978).

By examining Volkswagen’s strategies to manage the Arab League boycott, this paper answers one overarching research question: What strategies did Volkswagen implement to manage the threat of the Arab League boycott, and why? By answering this question, this paper makes two contributions. Empirically, it analyses how firms managed the Arab League boycott. Understanding the historical origins of boycott movements in the MENA region highlights how firms became and remain intertwined with geopolitics in the region. Markets in the MENA region bear a significance beyond mere export numbers and require corporate strategies that go beyond economic imperatives. Theoretically, this paper adds to the literature on MNEs’ boycott management strategies by inductively deriving a typology of MNEs’ responses to international boycotts (Bucheli & DeBerge, Citation2024; Casson & da Silva Lopes, Citation2013). This typology may provide a framework for classifying MNEs’ boycott management strategies and may be expanded in future research. By adding a historical perspective, this paper also responds to recent calls for ‘firm-level studies of historical sanctions’ to advance our ‘understanding of contemporary challenges confronting IB’ (Meyer et al. Citation2023).

This paper shows that Volkswagen used three overarching strategies to deal with the Arab League boycott: prevention, delay, and negotiation. First, the Arab League boycott compelled VW to adopt prevention strategies in Israel similar to those used by MNEs to manage political risks: camouflaging the firm’s market entry and then keeping a ‘low profile’ in the contentious host market (Kobrak & Wüstenhagen, Citation2006; Meyer & Thein, Citation2014; Wilkins, Citation2004). Second, facing the threat of an Arab League boycott, Volkswagen pursued delaying strategies to create time and room for manoeuvre. Third, using this time as a resource for action (Raaijmakers et al. Citation2015), Volkswagen’s board negotiated concurrently with home-country, export-country, and third-country actors to stimulate resistance to a boycott of the firm, implementing a large diplomatic toolkit that ranged from proposals for compensation investments to government interventions.

To make these contributions, this paper draws on primary sources from federal and corporate archives. These sources include board meeting minutes, internal reports, and internal and external correspondence. To highlight the conflicting demands imposed on MNEs in the MENA region, this article begins with an outline of the history of the Arab League boycott. The second section analyses Volkswagen’s boycott prevention strategies in the Israeli market. The third section examines VW’s delaying and negotiating strategies to mitigate the Arab League boycott threats between 1964 and 1977. The fourth section discusses the typology of boycott responses, and the final section concludes.

2. The Arab League boycott of Israel

Formed in March 1945 as an international association of Arab countries,Footnote4 the Arab League sought to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, enforcing primary, secondary, and tertiary boycotts. The primary boycott commenced in 1946, banning any trade between Palestinian Jews and member states of the Arab League (Fershtman & Gandal, Citation1998; Losman, Citation1972). The secondary and tertiary boycotts were implemented after the establishment of the Central Boycott Office (CBO) in Damascus in 1951. The CBO was the central bureau coordinating the boycott, with regional branches in most member states. The secondary boycott proscribed any trade with businesses engaging in commercial relations with Israel. This included firms that invested directly in Israel or granted licencing agreements to Israeli firms. The tertiary boycott prohibited foreign firms from establishing official partnerships or joint ventures with blacklisted companies. Firms suspected of violating boycott regulations received warning letters, typically granting them a six-month period to provide evidence of compliance. Boycott liaison officers from all member states convened at a biannual boycott conference to vote on whether a firm should be blacklisted, exonerated, or granted deadline extensions (Fershtman & Gandal, Citation1998; Losman, Citation1972; Sarna, Citation1986; Turck, Citation1977).

Even though these regulations were formally unambiguous, they caused fundamental insecurity among international firms, for two reasons (Saltoun, Citation1978).Footnote5 First, CBO-issued decrees were not binding, and each member state applied boycott regulations differently.Footnote6 Second, although regulations did not explicitly indicate that firms based in non-Arab states would face penalties for trading with Israel, the CBO and regional boycott offices occasionally imposed sanctions on firms for political reasons, especially when they feared that trade relations could strengthen Israel’s economic and military potential (Saltoun, Citation1978; Turck, Citation1977).Footnote7 Some firms even had to certify that they were ‘not doing business in Israel in terms of making sales to Israel’.Footnote8 To reduce the risk of being targeted by the CBO, many firms resorted to a voluntary boycott of Israel (Feiler, Citation1998; Steiner, Citation1978).

Besides the inconsistent application of boycott regulations by Arab League member states, the intensity of the Arab League boycott threat varied over time, becoming more pressing at two junctures. First, the election of Mohammed Mahmoud Mahgoub as the new commissioner-general of the CBO in 1963 led to stricter implementation of the Arab League’s boycott regulations. In particular, the boycotts of Coca-Cola, Radio Corporation of America, and Ford received global attention in 1966, with these firms unable to re-enter Arab League markets until the late 1970s and mid-1980s (Feiler, Citation1998; Labelle, Citation2014; Turck, Citation1977).Footnote9 Second, the 1973 Arab–Israeli war, including the October 1973 oil embargo, underscored and increased the financial power of Arab countries. While West Europe and the US suffered an economic crisis, foreign direct investments and trade with Arab League member states expanded. This prompted firms to pay closer attention to boycott regulations (Feiler, Citation1998; Reingold & Lansing, Citation1994; Saltoun, Citation1978; Turck, Citation1977). Consequently, West Germany’s ambassador to Israel informed the West German government in 1975 that the ‘new wealth of the Arabs has created a new reality’ that caused foreign firms to restrict or terminate their business relations with Israel.Footnote10

With the consequences of the boycott becoming more urgent for Israel, the Israeli government and Jewish nongovernmental organisations increased their efforts against the Arab League boycott. In Israel, they threatened counterboycotts against businesses complying with the Arab League boycott.Footnote11 West Germany and Israel had established diplomatic ties in 1965, and in 1968, Israeli ambassador Asher Ben-Nathan stated that Israel would ‘eliminate from our business relations those German companies that submit to the Arab boycott’.Footnote12 In the US, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, the American Jewish Committee, the American Jewish Congress, and the Israeli government lobbied for antiboycott laws. After Jimmy Carter had promised antiboycott legislation in the 1976 pre-election debates (Steiner, Citation1978),Footnote13 the US antiboycott law against complying with foreign boycotts was passed on 22 June 1977. This federal law made it illegal for US residents and enterprises to comply with any boycott against a country friendly to the US. Several US states implemented similar laws (Ludwig & Smith, Citation1978; Saltoun, Citation1978).

Growing public attention to US firms’ behaviour in the MENA region also affected international firms with a strong presence in the US. Jewish NGOs and the Israeli government frequently informed West German officials that they closely monitored German firms’ behaviour in the MENA region.Footnote14 West Germany’s ambassador to Israel noticed in 1970 ‘that Arab boycott threats and subsequent reactions of foreign companies are being followed particularly closely in the US’,Footnote15 and Israel’s government reminded the German government in 1975 that firms’ compliance with ‘the boycott against Israel could lead to countermeasures in places where there is a strong Jewish community, especially in the United States’.Footnote16 Consequently, West German organisations were ‘aware of the consequences of giving in to the Boycott Office, especially in the US’, prompting them ‘to adjust behaviour accordingly’ to avoid accusations of boycott compliance that could result in public and regulatory pressure in the US.Footnote17

The Arab League boycott of Israel began to disintegrate from 1979 to 1980 onwards after Egypt had signed the Camp David Accords, and most Arab states stopped enforcing the boycott in the following decades (Hawkins, Citation2010). The threat of the Arab League boycott thus reached its peak between 1973 and 1978, when the boycott imposed conflicting institutional demands on international firms operating in the MENA region (Feiler, Citation1998).

3. Prevention strategies: Volkswagen in Israel, 1960–1977

To manage these conflicting institutional demands, Volkswagen aimed to implement business strategies in Israel that neither attracted the CBO’s attention nor raised suspicions by US and Israeli stakeholders that the firm complied with boycott regulations. To achieve this, Volkswagen deployed various camouflaging strategies to conceal its market entry in Israel. With the firm’s growing success in the Israeli market, VW’s strategies in the market shifted. VW stopped camouflaging the basic fact of its market entry in Israel. However, the firm kept a ‘low profile’ in the market, hiding the extent of its market involvement (Meyer et al. Citation2023). Avoiding actions that would formally breach boycott regulations, the firm supported its general importers through unofficial channels. VW’s executives hoped that commercial success in Israel would have positive spill-over effects on VW’s business in the US.

3.1. Camouflaging tactics: Volkswagen’s market entry in Israel, 1960–1966

Volkswagen had become a global player by 1960 and was selling its cars in 149 countries, with its primary markets in West Europe and the US. In 1969, one-quarter of the firm’s total production went to the US market, making it Volkswagen’s most important export market by far (Rieger, Citation2013; Wellhöner, Citation1996).Footnote18 At the same time, industrialisation efforts in MENA countries offered favourable export conditions. Even though only one percent of Volkswagen’s total export of 1,400,000 cars went to Israel and Arab League member states in 1969,Footnote19 markets in the MENA region were expected to have strong growth rates in the future, whereas VW’s major sales markets in the US and West Europe had begun to show signs of saturation by the mid-1960s. To supply these smaller markets, Volkswagen reached agreements with independent general importers to keep market entry costs low and to compensate for a lack of local market knowledge. The general importers then set up local dealerships and service networks to guarantee the supply of spare parts and customer services. By 1960, VW exported its cars to most MENA countries except Israel (Wellhöner, Citation1996).

Volkswagen faced three particular challenges in the Israeli market. First, Israel’s protectionist trade policies prohibited car imports until October 1960 and minibus imports until 1963. After car imports were legalised, the market still faced high customs, high tax duties, and high interest rates (Michaely, Citation1975; Rivlin, Citation2010). Second, the operation of German firms in Israel was a highly contentious and politically charged issue. Many Israeli consumers continued to boycott and stigmatise German consumer products throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, with German cars being a particularly prominent target of protests as highly visible consumer products (Swisa, Citation2020; Tovy, Citation2020). And third, the Arab League boycott was a permanent threat to the automotive industry in the MENA region. This is illustrated by the list of firms being blacklisted throughout the years: Renault was boycotted from 1955 to 1959; Ford from 1966 to 1985; the producer of the Land Rover, the British firm Leyland, from 1970 to 1975; and with the exception of Subaru, which had chosen Israel as its sole export market in the MENA region, all Japanese and South Korean car manufacturers complied with boycott regulations until the mid-1980s (Table A1 in the online appendix) (Fershtman & Gandal, Citation1998; Sarna, Citation1986). Consequently, Volkswagen also refrained from participating in the West German-Israeli reparations agreement of 1952 as ‘the potential market in Israel would in no way correspond to what the Arab states are able to offer. Our products in particular would be so conspicuous in economic life that the neighbouring Arab countries would be immediately informed of any deliveries’ (cit. in Wellhöner, Citation1996, p. 211).

Table 1. Volkswagen’s boycott management strategies.

In the face of these risks, why did Volkswagen enter the Israeli market in 1960? Two motives could be anticipated for Volkswagen’s market entry: diplomatic considerations and profit maximisation. However, no evidence in newspapers, corporate documents, or federal archives indicates that Volkswagen faced public or governmental pressure to enter the Israeli market. Consistent with existing research on German firms in the Israeli market (Kleinschmidt, Citation2010), archival sources instead seem to suggest that Volkswagen’s market entry was driven more by commercial motives than diplomatic considerations, but both motives were closely intertwined.

Three reasons support this interpretation. First, the long-lasting import ban and the voluntary absence of major competitors had left Israel’s automobile market underdeveloped. Volkswagen saw the potential to achieve a high market share through early market entry, as ‘sales prospects [are] impossible to overlook’.Footnote20 Second, 250–300 Volkswagen vehicles had already trickled into Israel by 1959, and these were still lacking customer service. Third, representatives of Israel’s transport ministry encouraged the import of the Volkswagen, conveying to VW executives that ‘it’s time for the VW to come in’ and pledging ‘any possible support’ to VW’s general importer. For these reasons, Volkswagen’s representative for the Middle East concluded that ‘despite the Arab League, it seems appropriate, in a very cautious manner, only gradually, and under continuous observation’ to enter the Israeli market. He emphasised that ‘the main reason for this is the current VW stock in the country and the increasing influx of VW, for which some kind of adequate … customer service should be created’. However, Volkswagen had to ‘refrain from any steps and measures that could indicate [the existence of] an authorised VW representative’, with VW only carefully expanding its business ‘in accordance with the specific situation or opportunities of the country’.Footnote21

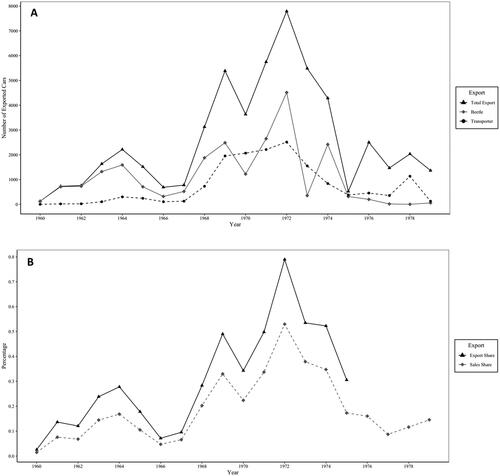

VW therefore remained cautious of the Arab boycott and used tactics to conceal its market entry. Despite its commercial motives for entering the Israeli market, VW did not prioritise profit maximisation. It reached a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ in 1959 with the Vesra Vehicle Trading Co. Ltd., managed by Mordecai Auerbach, to represent Volkswagen’s interest in Israel. Volkswagen thus refrained from concluding an official contract with Vesra as its general importer until 1962. In the first three years after market entry, Volkswagen kept export numbers to Israel low. Although Auerbach pushed for substantial increases in export numbers, Volkswagen only exported a total of just under 1500 Beetles to Israel until 1963 ().Footnote22 VW also prohibited Vesra from using the official VW logo until 1962 and instructed Auerbach to sell its cars in such a subtle manner that it would not reveal the fact that VW was marketing its vehicles in Israel.Footnote23 Finally, the firm camouflaged early deliveries by refusing to supply the general importer from its West German plant in Wolfsburg. Instead, automobiles were delivered from the Belgian car distributor Pierre d’Ieteren and marketed as ‘cars from Belgium: Wolfsburg’, because it was feared that ‘direct vehicle deliveries to Israel would have negative effects on the Arab markets due to the Israel boycott’.Footnote24

Figure 1A. Volkswagen’s exports to Israel, 1960–1979.

Notes. Total export numbers encompass all exports VW made to Israel in each year, including the export numbers of the Beetle, Transporter, and other passenger car models (Source: VWAG 174/1556/1; VWAG Z977). Figure 1B. Percentage of the Israeli market in VW’s annual exports and total sales figures. Export numbers to Israel are derived from archival sources (VWAG 174/1556/1; VWAG Z977). VW’s total export numbers and sales are drawn from Grieger and Lupa (Citation2014), except for the period 1976–1980, where total export figures are unavailable.

Volkswagen likely adopted the idea of using a foreign distributor to supply the Israeli market from other West German firms. German firms had gained experience in cloaking their assets and the national origin of their exports before and during World War II (Kobrak & Wüstenhagen, Citation2006; Wilkins, Citation2004). Because Volkswagen only began exporting its products in 1947, it lacked experience in camouflaging exports (Grieger & Lupa, Citation2014), and Volkswagen’s legal department noted in 1966 that ‘surprisingly, there is no record of who first had the idea of supplying the Israeli market from Belgium’.Footnote25 However, as early as 1954, Volkswagen’s management discussed strategies used by ‘many German firms [that] protected themselves against sanctions by the Arab League by avoiding direct negotiations with the Israeli and instead using their own or foreign trading companies’ (cit. in Wellhöner, Citation1996, p. 211). Consequently, the firm was well informed about the strategies used by other German firms to conceal their involvement in Israel.

After realising in mid-1962 that ‘according to previous experience, the Israel boycott regulations … do not affect direct deliveries from us to Israel’, Volkswagen began shipping its cars from Wolfsburg to Israel. Annual exports grew to 2214 vehicles in 1964, making the Beetle the most popular car imported into Israel.Footnote26 Auerbach expanded the dealership network, which by mid-1964 comprised seven outlets in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, Netanya, and Beersheba. As a result, Auerbach overstretched himself financially. By mid-1965, the company’s debts had reached almost 2.5 million Israeli pounds, and Vesra went bankrupt.Footnote27

Volkswagen’s camouflaging strategies now became the subject of a lawsuit, with VW executives well aware that the firm’s national origin and Nazi past would attract significant attention. Auerbach claimed that Volkswagen had bowed to the boycott by insisting on deliveries from Belgium, which had been more expensive than direct deliveries from Wolfsburg due to higher insurance costs. Newspapers published news dispatches with the headline ‘VW’s Surrender to Arab Boycott Causes Vesra’s Failure’, and VW’s lawyer in Israel informed executives in Wolfsburg that ‘this theme never fails to raise a spirited response from the great majority of citizens who suffered personal loss under the Nazi regime’.Footnote28 Even though Volkswagen’s camouflaging strategies could not be shown to have caused Vesra’s bankruptcy, VW conceded to paying 510,000 Israeli pounds (circa 85,000 US dollars in 1974) in compensation to Auerbach in 1974.Footnote29

3.2. Keeping a ‘low profile’: Volkswagen’s market consolidation in Israel, 1967–1977

VW’s business and reputation in Israel suffered from the bankruptcy of the general importer, as neither spare parts nor vehicles could be imported into Israel. Volkswagen had to find a new general importer who would adopt old inventories, honour customer advance payments made to Vesra, and rebuild the local dealership structure.Footnote30 In this process, VW officials acknowledged that ‘overcoming the “VW past”’ would be essential to ‘fully restore trust’ between consumers and the Israeli VW organisation.Footnote31

Volkswagen eventually came to an agreement with Champion Motors (Israel) Ltd. as its new general importer. This led to years of sustained export growth until 1973, for two main reasons. First, the outcome of the Six-Day War in June 1967 triggered an economic boom in Israel that lasted until the Arab–Israeli War of 1973 (Aharoni, Citation1991; Michaely, Citation1975). Second, the political climate improved for German firms in Israel. The political relationship between West Germany and Israel had been strained in the 1950s and early 1960s, but both countries established diplomatic relations in 1965. In addition, the broad support of the West German government and public for Israel during the Six-Day War had helped to ‘arouse sympathy towards Germany and German products’, resulting in ‘increased opportunities for our business’. Consequently, Volkswagen’s sales swiftly recovered.Footnote32

However, VW continued to be cautious of the Arab League boycott, keeping a ‘low profile’ by hiding the extent of its involvement in the Israeli market. VW officials continued to complain that positive developments in Israel ‘cannot be emphasised by us in public … if we do not want to run the risk of getting into bigger trouble with the Arab boycott offices’.Footnote33 For this reason, Volkswagen avoided a permanent commitment to the Israeli market through foreign direct investments or joint ventures. Yet, the firm aimed to establish and maintain close ties to the Israeli government,Footnote34 and the general importer employed Israeli exmilitary personnel to enhance the firm’s reputation and connections in Israel.Footnote35 In addition, Volkswagen’s export department aimed to capitalise on Israel’s economic boom. One of Volkswagen’s sales managers , directly reporting to Volkswagen’s board, acknowledged that VW supported efforts of the general importer ‘with new means that are not common in other countries’. By these means, the sales manager hoped to ‘have positive effects not only in Israel but ultimately in other countries, especially in the USA. It is not a buzzword … to speak quite rightly of a special situation in Israel. This special situation needs special measures and measuring with different yardsticks’.Footnote36

These measures included engaging in forms of ‘geopolitical jockeying’ (Lubinski & Wadhwani, Citation2020) by intending to increase deliveries to Israel in anticipation of possible counterboycotts against French firms in 1969 in retaliation for a French arms embargo of Israel.Footnote37 VW also ignored the expansion of its general importer into occupied territories after the Six-Day War in 1967 and helped ‘to establish contacts between our importer and the Arab importers who have been affected [by Israel’s territorial expansion]’.Footnote38 And finally, VW’s export and production departments helped Champion Motors in 1970 to establish a remanufacturing plant for VW engines by providing knowhow through unofficial channels. Even though the importer had to ‘explicitly refrain from even hinting at or advertising VW’s assistance in setting up a motor remanufacturing facility in Israel’,Footnote39 Champion Motors seems to have succeeded in opening the plant as VW had found means to support ‘Israel in a way that was not otherwise customary’.Footnote40

As a result of these efforts, VW’s dealership network in Israel expanded continuously, including three authorised workshops and 19 dealerships by 1972, which serviced approximately 36,100 Volkswagen vehicles in Israel. In Wolfsburg, one of Volkswagen’s sales managers announced that it had been possible to ‘achieve first place’ in the Israeli market—’in spite of all the difficulties in this country in particular’.Footnote41 With the exception of 1970,Footnote42 export figures rose continuously until 1972 when they reached the record level of 7792 vehicles. VW officials hoped for positive spill-over effects to the US, but the Israeli market also accounted for 0.78% of Volkswagen’s global exports (). Thus, the Israeli market’s size almost equalled that of all the Arab League states together, underlining its outsized significance for VW in the MENA region.Footnote43

However, the 1973 Arab–Israeli war marked a turning point in Volkswagen’s history in Israel. Israel’s economic growth plummeted (Aharoni, Citation1991; Rivlin, Citation2010), and the oil crisis threw the automotive industry into disarray. Coinciding with VW’s conversion crisis as the firm introduced new models to the international market in an effort to emancipate itself from the Beetle, Volkswagen’s global sales dropped by 40% (Rieger, Citation2010), and VW’s total passenger car exports to Israel fell to a total of 1112 vehicles by 1977. Moreover, Japanese carmakers and Ford rejoined the Israeli market in the 1980s (Fershtman & Gandal, Citation1998). As a result, VW was unable to recover its 1972 sales figures throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote44 And while the outcome of the Arab–Israeli war worsened the firm’s outlook in the Israeli market, it also increased the intensity of another risk: the Arab League Boycott of Israel.

4. Delaying and negotiating strategies: managing Arab league boycott threats, 1964–1977

Volkswagen faced the Arab League boycott threat twice. The first threat emerged in 1964 due to donations from the Volkswagenwerk Foundation to the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Although Volkswagen swiftly averted this boycott threat by offering compensation investments, the threats between 1969 and 1977 lasted longer and were related to Volkswagen’s takeover of NSU AG, which had signed a licencing agreement with Savkel, an Israeli firm. To manage the boycott threat, Volkswagen implemented delaying strategies to create time and room for negotiations with major stakeholders (Raaijmakers et al. Citation2015). During these negotiations, Volkswagen worked towards two solutions. First, it attempted to persuade the CBO and its member states through soft power and governmental pressure to delay a boycott decision and withdraw charges against VW. Second, VW negotiated with Israeli stakeholders to terminate the licencing contract in a manner that would avoid generating negative publicity in either the US or Israel.

4.1. Boycott threat 1964

In spring of 1964, it became public that the Volkswagenwerk Foundation had donated 2.2 million Deutsche mark to the Weizmann Institute.Footnote45 Despite the foundation’s formal independence from VW, representatives from various boycott offices and the CBO clarified that VW could only avert a boycott by freezing payments to the institute or by making similar donations to Arab institutions. In Wolfsburg, officials were certain that ‘the boycott threats … against VW products definitely need to be taken seriously’.Footnote46

As a result, Heinrich Nordhoff, General Manager and CEO of VW (1948–1968), and Gotthard Gambke, Secretary General of the Volkswagenwerk Foundation (1962–1975), coordinated their response to the threats.Footnote47 The Ford Company had faced similar issues due to donations made by the Ford Foundation to the Weizmann Institute and other Israeli institutions in the 1950s (Lewis, Citation1976). Mahgoub reminded VW’s executives that Ford had balanced these investments with similar contributions to Arab institutions. Consequently, the Foundation’s board of trustees decided to identify projects in Arab League countries ‘that could be considered for funding. The Arabs could then be unofficially encouraged to submit a corresponding application’.Footnote48 Satisfied by the Foundation’s offer to fund Arab institutions, Mahgoub informed Nordhoff in June 1964 that the CBO would now acknowledge that there was no organisational or financial connection between Volkswagen and the Volkswagenwerk Foundation.Footnote49

Although the CBO’s demands were quickly resolved, Volkswagen and the Volkswagenwerk Foundation aimed to retain ‘a certain balance in the foundation’s work with the Arab countries’.Footnote50 To retain this balance, visits of foundation representatives to Israel in 1965 had to be offset by similar visits to Arab League member states.Footnote51 Moreover, Gambke emphasised in 1967 the need ‘to pursue Arab projects, even if they do not have the same scientific significance as Israeli projects’ because an exclusive focus ‘on Israel while excluding the Arab countries carries the risk of a boycott of Volkswagen’.Footnote52 Recognising the foundation’s importance in mitigating Arab League boycott threats, the West German Foreign Office continued to suggest in 1974 that ‘it might help if the foundation … gave some funds to Arab countries’, and the foundation agreed to consider applications from Arab countries favourably.Footnote53

4.2. Boycott threat 1969–1977

Whereas Volkswagen’s encounter with the CBO in 1964 was short-lived, its struggles with boycott threats between 1969 and 1977 were long-lasting (Kaikati, Citation1978; Turck, Citation1978). These threats arose from Volkswagen’s acquisition of NSU AG on 21 August 1969, which was later merged with VW’s subsidiary Auto Union and renamed Audi NSU Auto Union AG. In response, several regional boycott offices issued boycott threats against VW in 1969 and 1970, for two reasons. First, one of the largest minority shareholders of NSU was the Israel–British bank, which owned circa 14% of NSU’s shares.Footnote54 Even though Israel–British bank could not influence any decision-making processes, regional boycott office officials warned Volkswagen that ‘any participation of Israeli capital will lead to a boycott of a foreign company, including branches and subsidiaries’. VW was given six months to either liquidate the Israeli capital or sell its own shares in NSU AG.Footnote55 Even though the Israel–British bank initially refused VW’s offer to exchange its stocks, VW eventually bought all the NSU shares owned by the Israel–British bank in November 1971 for 4.5 times their original market price.Footnote56

Whereas VW was able to fulfil these requirements, the second boycott threat stemmed from a licencing agreement between NSU and the Israeli firm Savkel. NSU held the licencing rights for the Wankel engine and had negotiated a licencing agreement with Savkel in May 1969 to produce industrial and boat engines for the next 14 years. Despite VW’s warnings of the Arab League boycott, the contract was eventually signed on 28 August 1969, a week after NSU had officially merged with VW. Several regional boycott offices became aware of the existence of the contract in 1970, and the CBO began to intensify its pressure on Volkswagen after the escalation of the Arab–Israeli conflict in October 1973. The CBO demanded that Volkswagen hand over the contract between Audi NSU and Savkel and, after receiving the contract, required Volkswagen to end the licencing contract between Audi NSU and Savkel, to liquidate any participation in the Wankel patents, or to sell its Audi NSU shares within six months.Footnote57

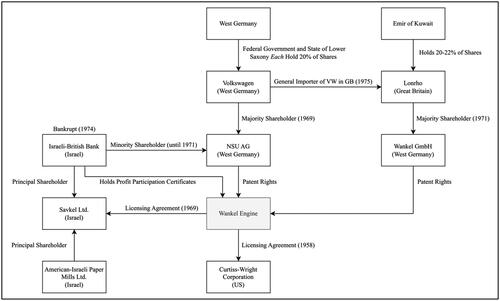

VW’s board could not meet any of these requirements for three reasons. First, Audi NSU was not the sole owner of the licencing rights. The agreement with Savkel had also been signed by the Wankel GmbH, whose majority shareholder became the British Lonrho group in 1971. A termination of the agreement therefore required negotiations with Lonrho, 20–22% of whose shares were owned by the Emir of Kuwait.Footnote58 Second, to convince NSU shareholders to vote for the merger of NSU with Volkswagen, VW had offered them 15-year-long profit participation certificates based upon revenues made from Wankel’s licencing rights. This commitment legally bound VW to maintaining the existing licencing policy (Knie, Citation2002).Footnote59 Third, unknown to the CBO, VW’s board believed that the Israel-British Bank, which also owned 50% of Savkel’s shares,Footnote60 held a significant number of profit participation certificates and therefore had a particular interest in the exploitation of the Wankel patent—and in making public any violations of the agreement by Volkswagen. Aware of Volkswagen’s nationality and Nazi past, VW’s board feared that terminating the contract with Savkel would provoke a ‘fierce Israeli reaction’, leading to legal challenges ‘and sales losses in Israel and the USA … that are more serious than temporary losses in the Arab markets’.Footnote61 Selling Audi NSU was ruled out as a serious option by VW’s board.Footnote62 illustrates the ownership relations.

Figure 2. Ownership relations regarding the Wankel licencing agreement, 1969–1977.

Note. Own drawing.

4.2.1. Delaying strategies

Faced with the options of either terminating the Savkel contract or accepting the Arab League boycott, VW’s board members realised in November 1973 that there ‘is no longer a course of action that is advantageous for VW’.Footnote63 To manage this dilemma, VW’s board first created time and room for manoeuvre by pursuing delaying strategies (Raaijmakers et al. Citation2015). They aimed to secure recurring postponements of the CBO’s six-month deadline, knowing that handing over the contract would provide written proof to the CBO that Volkswagen violated boycott regulations. For this reason, VW’s board exploited information asymmetries, provided only partial information of the contract to the CBO, and delayed providing this information until a few days before deadlines expired. By partially complying, VW’s delegations aimed to demonstrate their intent to meet the CBO’s demands while arguing that the legal intricacies of the case prevented full and swift compliance.Footnote64

When pressure became ‘irrefutable’ in August and September 1975, a Volkswagen delegation provided the CBO with copies of the full contract. These copies provided conclusive evidence of VW’s violation of boycott regulations, but they also proved the involvement of Wankel and Lonrho. In response, Mahgoub informed VW that the boycott conference had postponed a final decision ‘for the sake of justice and equality’ for another six months until a boycott warning had been issued against Lonrho.Footnote65 Seeking deadline extensions beyond February 1976, VW now explored the possibility of demerging the Wankel patents from Audi NSU. While this proved to be legally challenging, VW also entered negotiations with Lonrho over the sale of licencing rights in 1976 ‘to win arguments for another extension request to the Arab League’, in full awareness that selling the patent rights was virtually impossible.Footnote66

4.2.2. Negotiating strategies

While buying itself time, VW negotiated with all parties to raise opposition against a boycott of VW. First, benefitting from its partially state-owned ownership structure, VW’s board members collaborated with the West German government. Second, VW negotiated with Arab League officials, the CBO, and regional boycott offices through various channels to raise the costs of a boycott of VW and to provide incentives for delaying a boycott decision. Third, VW’s board coordinated its actions with Tiny Rowland, CEO of Lonrho, and Lonrho’s Kuwaiti shareholders. Fourth, VW began negotiating with Israeli stakeholders. provides an overview of the strategies and tactics VW used to manage the Arab League boycott.

4.2.2.1. Securing home government support

VW began to coordinate its efforts with the West German government and Foreign Office closely from November 1973 onwards, with Rudolf Leiding, CEO of Volkswagen (1971–1975), claiming that the boycott threats had ‘gained great importance for our company as a result of the heightened tensions in the Middle East’.Footnote67 To secure government support, VW executives used two main arguments. First, they stressed the economic importance of VW for the West German economy and warned of potential layoffs if the Arab market was lost. Second, VW’s board claimed that giving in to the CBO’s demands would jeopardise the fragile Israeli–West German relationship as ‘the Israeli government is following the process and attaches political importance to it’.Footnote68 VW executives were certain that diplomatic assistance was vital to calm the boycott threat because Arab League member states would want ‘to avoid a scandal in the case of VW and possible political tensions in the relationship with the FRG [Federal Republic of Germany]’.Footnote69

The Foreign Office recommended that VW should not bow to the boycott, arguing that the issue of the Arab League boycott threat was handled by the ‘federal government in bilateral negotiations at the highest level’.Footnote70 These negotiations included meetings in 1975 between Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher and the General Secretary of the Arab League, Mahmoud Riad, with Genscher intervening on VW’s behalf.Footnote71 The Foreign Office and the Ministry of Economic Affairs also sent memoranda to all German embassies in Arab League member states on various occasions, requiring diplomats to lobby ‘the representatives of the national boycott office … to vote against a boycott of VW’.Footnote72

4.2.2.2. Exerting soft power

Genscher also informed Toni Schmücker, CEO of VW from 1975 to 1982, that the Wankel licence had not been the primary reason for the boycott threat. Instead, Genscher claimed, ‘the intention is the establishment of a VW assembly plant in an Arab country’.Footnote73 Boycott rules had indeed been modified in 1975 to allow firms to offset investments in Israel by investing similar amounts in Arab states,Footnote74 and Egypt’s president, Anwar El-Sadat, publicly announced in 1976 that he welcomed the prospect that ‘Volkswagen would erect an assembling plant in Egypt’.Footnote75 In negotiations with officials of the Arab League, the CBO, and representatives of Arab League member states, delegations of VW board members claimed that the firm was considering compensation investments in Syria, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Iraq. However, as long as the boycott threat lingered, VW officials emphasised that any investment in Arab League member states would pose too great a risk to the firm.Footnote76

4.2.2.3. Industrial cooperation

At the same time, VW’s efforts with Arab League representatives were jeopardised by Lonrho. The CBO targeted Lonrho from September 1975, after VW disclosed that Wankel GmbH had also signed the licencing agreement.Footnote77 In response to the boycott threat, Lonrho tried to unilaterally and illegally terminate its part of the deal with Savkel. Tiny Rowland also proposed to Mahgoub and Schmücker in January 1976 to buy the rights to the Wankel patent entirely of Audi NSU. VW’s board suspected that Rowland sought cheap access to the entire Wankel licencing rights, and they feared that reaching such agreements with Lonrho would make VW susceptible to blackmailing for concessions in the British market, as Lonrho had become Volkswagen’s general importer in Great Britain in 1975.Footnote78 However, without VW’s and Savkel’s approval, Lonrho could not terminate the contract without facing legal charges, and Lonrho’s actions ‘forced’ Volkswagen’s board to ‘communicate in all clarity the invalidity of the [contract] termination to Mr. Mahgoub’.Footnote79

As the CBO continued to threaten Lonrho and VW over the same contract, the firms began to coordinate their actions more closely. Volkswagen entered façade negotiations with Lonrho ‘in order to be able to prove to the CBO the intention to sell the Wankel patents’.Footnote80 Since neither firm could legally terminate the contract, they agreed on pursuing further delaying strategies. Lonrho now conveyed ‘to the Central Boycott Office that a demerger and … further steps will require a significant amount of time’.Footnote81 Because the Emir of Kuwait was a major shareholder in Lonrho, VW board members also began meeting with representatives of Kuwait in the hope that Kuwait’s active involvement and efforts to avoid the boycott would benefit Volkswagen’s case.Footnote82

4.2.2.4. Strategic patience and contract cancellation

While trying to pressure and lure Arab League member states into voting against a boycott of Volkswagen, VW’s board simultaneously negotiated with Savkel and its shareholders through Audi NSU’s board and VW’s own middlemen. In 1973, Savkel representatives threatened Volkswagen with ‘countermeasures not only in Israel, but also with actions in the US’ in the case of a termination of the contract.Footnote83 However, they hinted at the possibility of a formal cancellation of the contract. Savkel insisted on receiving a substantial compensation sum of 50–60 million Deutsche mark and on continuing the development of the Wankel engine by receiving the licence through a third company, the US firm Curtiss-Wright, which held the licencing rights for North America.Footnote84

Negotiations over a cancellation of the contract did not begin in earnest until mid-1976, for three reasons. First, Mahgoub maintained that terminating the contract between Audi NSU and Savkel was insufficient. Instead, Savkel had to halt developing the engine, and Mahgoub clarified that the CBO would still consider boycotting Volkswagen if Savkel obtained the licence through a third company.Footnote85 Second, Savkel faced difficulties starting serial production of the Wankel engine, and VW’s board hoped that delaying negotiations would weaken Savkel’s negotiation position. Third, Volkswagen’s board feared that entering negotiations with Savkel prematurely might increase the compensation sum and create the impression that VW was giving in to the boycott. The board therefore agreed in March 1976 to engage in a tactic of ‘strategic patience’ and to enter negotiations with Savkel only after either a boycott against VW was implemented or Savkel approached VW.Footnote86

In July 1976, VW’s board received news that Savkel was now willing to cancel the contract on more favourable terms. Audi NSU and Savkel officially terminated the contract in November 1976.Footnote87 Savkel continued developing the Wankel engine, and Israeli newspapers reported in May 1977 that the firm aimed to begin production now.Footnote88 Initially, the CBO insisted that VW take legal action against Savkel for the continued development of the engine. However, in July 1977, the CBO eventually accepted the formal cancellation of the contract to avoid further diplomatic disputes.Footnote89 Besides diplomatic pressure, waning enthusiasm for the Wankel engine likely influenced the CBO’s decision to abandon its boycott threat.Footnote90 Savkel remained one of the few firms working on the engine, but they faced increasing difficulties in fulfilling its debt obligations and were never able to produce the Wankel engine in large numbers.Footnote91

5. The management of international boycotts: a typology

Research has demonstrated that when MNEs face boycott threats for violating widely shared social values, they reinforce their prosocial claims in public relations campaigns to show their alignment with these values (Bucheli & DeBerge, Citation2024; Glover, Citation2019; Levy, Citation2020; McDonnell & King, Citation2013). Yet, when the political and ethical aims associated with international boycotts lack universal acceptance (Li et al. Citation2022; Mohliver et al. Citation2023), public relations campaigns targeting one actor and market may conflict with the values of actors in other markets, thus adversely affecting the firm’s revenues, reputation, and legitimacy in that market (Kostova et al. Citation2008; Kostova & Zaheer, Citation1999; Li et al. Citation2022; Sun et al. Citation2021). To manage the conflicting institutional demands arising from international boycotts, firms are likely to adopt different and more covert strategies. Given that firms do not openly discuss decision-making in sensitive environments, a historical perspective is necessary to identify these strategies (Bucheli & DeBerge, Citation2024; Meyer et al. Citation2023).

For this reason, this study has analysed VW’s management strategies in response to the Arab League boycott of Israel. Using the case study of Volkswagen, this paper has developed a typology of MNEs’ management strategies that can be utilised and expanded upon by future researchers. The typology identifies three major types of strategies to manage international boycotts: prevention, delay, and negotiation. provides an overview of the typology of strategies and tactics to counter boycott threats.

Table 2. Typology of boycott management strategies.

To prevent the Arab League boycott, Volkswagen first implemented camouflaging strategies to hide its market entry in Israel. These strategies are similar to those identified in the literature on the management of political risks (Kobrak & Wüstenhagen, Citation2006; Wilkins, Citation2004). VW concealed exports, suppressed marketing efforts, and kept export figures low. When economic opportunities in the Israeli market brightened in 1967, Volkswagen shifted strategies and kept a ‘low profile’ (Meyer & Thein, Citation2014). The firm stopped camouflaging the basic fact of its market involvement in Israel but also refrained from permanently committing to the market through joint ventures or foreign direct investments. However, VW increased its support for the general importer, ignored the importer’s expansion into occupied territories, covertly shared technical knowhow, and engaged in forms of ‘geopolitical jockeying’ to improve its sales in the Israeli market (Lubinski & Wadhwani, Citation2020). By adopting a historical perspective, this paper has thus demonstrated the enduring impact of sanctions that prompted Volkswagen to implement prevention strategies long before facing an actual boycott threat from the CBO.

Once the CBO threatened Volkswagen, VW pursued delaying strategies to create time and room for manoeuvre (Raaijmakers et al. Citation2015). The firm only partially complied with the CBO’s demands (Li et al. Citation2022), fostering and exploiting information asymmetries by providing the CBO with incomplete information on NSU’s contract with Savkel. To give the impression that the firm was willing to comply with boycott regulations, the firm entered façade negotiations with Lonrho. While these delaying strategies were aimed at creating room for negotiations, delay was also an end in itself. By buying itself time, Volkswagen engaged in a tactic of ‘strategic patience’, hoping that Savkel’s negotiating position would deteriorate over time due to the difficulties of producing the Wankel engine at a large scale.

Thirdly, the firm used time as a resource by initiating negotiations with all external actors (Raaijmakers et al. Citation2015). To raise opposition against a boycott of VW among Arab League member states, Volkswagen’s board exerted ‘soft power’ by using a broad diplomatic toolkit that ranged from the preferential treatment of Arab institutions by the Volkswagenwerk Foundation to negotiations about foreign direct investments in Arab League member states. In addition, Volkswagen began cooperating with Lonrho, agreeing with the firm to follow further delaying strategies. At the same time, Volkswagen engaged in conversations with Savkel to negotiate the cancellation of the licencing contract. Finally, Volkswagen cooperated and coordinated its actions closely with the West German Foreign Office to secure home government support. The Foreign Office’s diplomatic intervention proved crucial as it effectively conveyed to Arab League representatives that a boycott of VW would strain Arab–West German relationships.

Although diplomatic support by the home government was essential for the firm, Volkswagen’s national origin also played a pivotal role in shaping the firm’s strategies in the MENA region, and economic and diplomatic considerations were often inextricably intertwined. The archival evidence suggests that VW’s initial decision to enter the Israeli market was not primarily motivated by corporate atonement (Kleinschmidt, Citation2010). However, Volkswagen’s strategies after entering the market were also never solely focused on maximising profits in Israel. Because Volkswagen relied on the silence of Jewish Americans to regain moral legitimacy in the US market (Rieger, Citation2013), VW’s executives never considered leaving the Israeli market when facing the Arab League boycott. Given the firm’s national origin and Nazi past, the firm feared reputational damages and potential sales losses in the US and Israel that would exceed losses in Arab League markets.Footnote92 Although potential spill-over risks affected all MNEs operating in the MENA region and the US, Volkswagen’s national origin magnified such risks for the company. As a result, VW was keenly aware of how its national origin influenced consumers’ perceptions of the firm’s actions, circumscribing its strategic options in the MENA region.

6. Conclusion

Even though VW’s boycott management strategies were not the sole reasons for Volkswagen’s success in Israel, they were an important prerequisite. The de-stigmatisation of the Beetle in Israel is particularly striking, considering that some cultural products from Germany continue to be boycotted in Israel to this day.Footnote93 The Beetle benefitted from its worldwide reputation, and general developments in the Israeli–West German relationship shaped attitudes towards the car. Yet, Israelis noted Volkswagen’s refusal to bow to the boycott.Footnote94 Books, Israeli government pamphlets, and newspaper articles from the 1970s and 1980s interpreted VW’s lengthy struggle with the CBO as a successful example of how firms can withstand the Arab League boycott threat (Sarna, Citation1986).Footnote95

The significant threat that the Arab League boycott posed for firms in the automotive industry in the MENA region becomes evident when considering the number of companies blacklisted (Table A1). However, the absence of market competitors also provided economic opportunities to firms able to manage boycott risks (Casson & da Silva Lopes, Citation2013; Lubinski & Wadhwani, Citation2020). Whereas Volkswagen’s decision-making in Israel was never solely profit-driven, its boycott management strategies ultimately retained the firm’s legitimacy across all markets, enabling it to exploit the economic opportunities in the Israeli market.

Volkswagen’s executives often compared their behaviour in the region to the actions of Ford and Renault, offering a wider glimpse into the strategic toolkit of carmakers dealing with the boycott risks of the region. Similar to VW, the Ford Foundation made contributions to Arab institutions in the 1950s to offset donations made to the Weizmann Institute (Lewis, Citation1976), and the Ford Motor Company unsuccessfully sought to be removed from the blacklist in 1975 by negotiating with Egyptian authorities over a 230 million dollar investment in Alexandria (Tignor, Citation1990). In contrast to VW, the boycott threat to Ford had already materialised. Not having to appease conflicting expectations, Ford reframed its behaviour in the MENA region as a matter of moral principle to honour free and fair competition (Chernow, Citation1990). Future research has to show in greater detail the degree to which Volkswagen’s reactions to the Arab League boycott were uniquely shaped by its national origin and differed from firms headquartered in other countries.

Even though the Arab League boycott has disintegrated since 1979, strategies to thwart boycott threats in the MENA region remain relevant. Today, social activist groups such as the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement operate through global campaigns and pressure international firms to boycott and divest from Israel (Feldman, Citation2019). Firms complying with these boycott demands still face vigorous counter-responses in Israel and the US. For example, when the ice cream producer Ben & Jerry’s announced in July 2021 that it would stop selling its products in the West Bank, social activist groups lauded the company’s step. However, Ben & Jerry’s decision triggered antiboycott laws in several US states, and US state pension funds divested from Unilever, Ben & Jerry’s parent company.Footnote96 In response, Unilever sold its Ben and Jerry’s business interests in Israel to the Israel-based licensee in June 2022.Footnote97

The behaviour of international firms in the Israeli market thus still reverberates beyond the MENA region, and the case of Volkswagen illustrates how firms have historically managed international boycotts in this region. This paper has taken a historical perspective to inductively derive a typology of MNEs’ boycott management strategies that reveals how international boycotts affected corporate decision-making in the long-term. Volkswagen’s strategies shifted over time from prevention to delaying to negotiation in response to varying boycott threat levels. Volkswagen’s boycott prevention strategies mirror those identified in previous research, but this study has also extended prior findings by demonstrating how Volkswagen intentionally delayed compliance with contentious boycott demands to enter negotiations with political and industrial actors from multiple countries. Ultimately, the firm reached a compromise amid conflicting demands to retain its legitimacy across all markets.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (212.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Gerben Bakker, Karolina Hutková, Ingo Köhler, Tobias Straumann, participants of the Business History Conference 2021, the Workshop on Business History in Central and Eastern Europe 2022, the Business History Beyond Boundaries PhD Summer School 2022, and two anonymous referees for insightful feedback at different stages of the manuscript. I am particularly indebted to Jan Logemann for sparking the idea for this research and providing invaluable guidance in preparing and writing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonas M. Geweke

Jonas M. Geweke is PhD student at the Department of Sociology of the University of Zurich.

Notes

1 Whereas boycotts may target organizations, sanctions are aimed at weakening governments to induce policy changes (Meyer et al., Citation2023). This paper uses the broader term “boycott” to maintain consistency with the term “Arab League boycott” and cover all risks encountered by MNEs in the MENA region.

2 Volkswagen Corporate Archives (VWAG) 1133/289/4.

3 Dornberg, J. (1976, May 23). VW and sinking German work morale. Jerusalem Post, 7.

4 The six founding states include Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan (today Jordan), Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. Yemen joined in May 1945, Libya in 1953, Sudan in 1956, Morocco and Tunisia in 1958, Kuwait in 1961, Algeria in 1962, and Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates in 1971. Egypt’s membership was suspended in 1979 after the signing of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty (Turck, Citation1977).

5 BArch B102/168333.

6 The German Embassy in Washington D.C. noted in 1968 that Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Jordan strictly implemented the boycott, but that Bahrain and Sudan were less strict. Boycott regulations were only formally in place in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, BArch B102/75036.

7 BArch B102/168333.

8 Extension of the export administration act of 1969. (1976). Hearings before the committee on international relations: House of representatives: 94th Congress: Second Session: Part I. U.S. Government Printing Office, 73.

9 Arabs lift boycott on Leyland. (1976, April 4). Jerusalem Post, 2.

10 BArch B102/168334.

11 BArch B102/75034.

12 BArch B102/75036.

13 BArch B102/275361.

14 BArch B102/213299; BArch B102/213297.

15 BArch B102/168333.

16 BArch B102/168335.

17 BArch B102/212236.

18 VWAG, Bericht über das Geschäftsjahr 1969.

19 VWAG 263/404/1.

20 VWAG 263/404/1.

21 VWAG 174/1557/8.

22 VWAG 174/1551/1; VWAG 174/1556/2.

23 VWAG 174/1552/2.

24 VWAG 174/1552/2.

25 VWAG 174/1556/2.

26 VWAG, 174/1556/1.

27 VWAG 174/1557/1.

28 VWAG 174/1552/4.

29 VWAG 74/1556/1.

30 VWAG 174/1551/1.

31 VWAG 174/1557/4.

32 VWAG 174/1557/4.

33 VWAG 174/897/1.

34 VWAG 174/897/1.

35 VWAG 174/1557/4.

36 VWAG 74/1557/4.

37 VWAG 174/1557/5.

38 VWAG 174/897/1.

39 VWAG 263/404/1.

40 VWAG 174/897/1; J’lem plant to refurbish car engines. (1970, July 27). Jerusalem Post, 7.

41 VWAG 174/897/1.

42 The Israeli government increased the customs and tax burden on cars in January 1970, causing export figures to plummet by almost one-third in that year, VWAG 263/404/1.

43 VWAG 373/170/2.

44 VWAG Z977.

45 Even though the donations may have contributed to enhancing Volkswagen’s legitimacy in the Israeli market and beyond, historians have only speculated about whether this was the driving motivation behind the Foundation’s support of the Weizmann Institute (Hestermann, Citation2016).

46 VWAG 69/297/1.

47 VWAG 69/297/1.

48 VWAG 263/396/4.

49 VWAG 69/297/1.

50 VWAG 174/2536/2.

51 VWAG 174/2533/1.

52 VWAG 174/2536/2.

53 BArch B126/77080.

54 BArch B102/168333; Große Wische. (1971, November 7). Der Spiegel.

55 BArch B102/168333.

56 The high price led to legal charges in West Germany by other minority shareholders who had sold their shares at significantly lower prices. Archival sources do not reveal whether considerations regarding the Arab League boycott had informed business decisions in this case, Stueck, H. J. (1971, November 5). VW offering set for Audi shares. New York Times, 72; Große Wische. (1971, November 7). Der Spiegel.

57 BArch B102/168335.

58 BArch B102/168335; VWAG 1133/272/2; VW says Arab boycott could rather be aimed at Kuwait. (1975, March 4). Jerusalem Post, 5.

59 BArch B102/168334; VWAG 1133/272/2.

60 Ater, M. (1969, May 13). Israel gets option to make Wankel engines. Jerusalem Post, 9.

61 VWAG 1133/289/4.

62 VWAG 373/183/2.

63 VWAG 1133/289/4.

64 VWAG 1133/289/4.

65 VWAG 373/182/2.

66 VWAG 373/183/2; VWAG 373/189/1; VWAG 1133/274/4.

67 BArch B102/168333.

68 BArch B102/168334.

69 VWAG 373/183/2.

70 BArch B102/212236.

71 Akten zur Auswärtigen Politik der Bundesrepublik 1975, 358.

72 BArch B102/168334.

73 VWAG 610/588/1.

74 These modifications intended to enable a 230 million dollar investment by the Ford Motor Company in Alexandria, Egypt (Tignor, Citation1990).

75 BArch B126/77080; Volkswagen to build a plant in Egypt. (1981, March 24). New York Times, 8.

76 BArch B102/213297; BArch B102/317427; VWAG 373/180/2.

77 VWAG 373/182/2.

78 VWAG 1133/274/4; VWAG 1133/272/2.

79 VWAG 1133/297/4.

80 VWAG 1373/189/1.

81 VWAG 1133/298/6.

82 VWAG 1133/298/6.

83 VWAG 1133/289/4.

84 VWAG 373/183/2; BArch B102/213297.

85 VWAG 373/182/2.

86 VWAG 373/458/1; VWAG 373/1891/1.

87 BArch B126/77080.

88 Macabee, D. (1977, May 10). Industry saves Galilee. Jerusalem Post, 9.

89 VWAG 373/183/2.

90 GM calls it quit on its $140m. gamble on the Wankel rotary motor. (1977, April 14). Jerusalem Post, 11; Ronnen, M. (1983, April 08). Styling versus design. Jerusalem Post, N.

91 Maoz, S. (1980, May 27). Wankel = Chelm = IS39m. lost. Jerusalem Post, 5; Maoz, S. (1980, July 30). Firm changes name, seeks more aid. Jerusalem Post, 2; Savkal aid approved despite criticism (1980, August 1), Jerusalem Post, 2.

92 VWAG 1133/289/4.

93 Throughout the years, numerous authors have highlighted Israel’s ambiguity in its treatment of West German consumer products and cultural products by referring to the abundant numbers of the Beetle on Israeli streets, e.g. Pelleg, F. (1966, June 24). Chopin too. Jerusalem Post, 10; Boehm, Y. (1974, June 24). Wagner and Strauss – still two of our strongest taboos. Jerusalem Post, 10.

94 For example, in 1966, one Israeli reader wondered whether Israelis who attacked VW had forgotten ‘the substantial contributions made by the Volkswagen Works to the Weizmann Institute, and which unlike Renault, has never bowed to the Arab boycott?’ Juchwid, M. (1966, June 29). ‘If Germany hits back.’ Jerusalem Post, 3.

95 BArch B102/168334; VW deal in Israel kept despite threat of Arab ban. (1975, August 23). New York Times, 3.

96 Nahmias, O. (2021, December 23). Illinois divests from Unilever over Ben and Jerry’s Israel boycott. Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/bds-threat/article-689621; Evans, J. (2022, October 11). Ben & Jerry’s vs Unilever: How a star acquisition became a legal nightmare. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/30efd993-8c23-4f1b-9385-132bbba3d863.

97 Craggs Mersinoglu, Y. (2022, June 29). Ben & Jerry’s sales to continue in Israel after Unilever sells licence. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/de298bbf-305f-4d20-ab8c-74d0ec841317.

References

- Aharoni, Y. (1991). The Israeli economy: Dreams and realities. Routledge.

- Bucheli, M., & DeBerge, T. (2024). Multinational enterprises’ nonmarket strategies: Insights from History. International Business Review, 33(2), 102198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2023.102198

- Casson, M., & da Silva Lopes, T. (2013). Foreign direct investment in high-risk environments: An historical perspective. Business History, 55(3), 375–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.771343

- Chernow, R. (1990). The house of Morgan: An American banking dynasty and the rise of modern finance. Grove Press.

- Feiler, G. (1998). From boycott to economic cooperation: The political economy of the Arab boycott of Israel. Routledge.

- Feldman, D. (2019). Boycotts: From the American Revolution to BDS. In D. Feldman (Ed.), Boycotts past and present: From the American revolution to the campaign to boycott Israel (pp. 1–19). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fershtman, C., & Gandal, N. (1998). The effect of the Arab boycott on Israel: The automobile market. The RAND Journal of Economics, 29(1), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555822

- Friedman, M. (1999). Consumer boycotts: Effecting change through the marketplace and the media. Routledge.

- Glover, N. (2019). Between order and justice: Investments in Africa and corporate international responsibility in Swedish media in the 1960s. Enterprise & Society, 20(2), 401–444. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2018.87

- Grieger, M., & Lupa, M. (2014). From the Beetle to a global player: Volkswagen chronicle. Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft.

- Hawkins, R. A. (2010). Boycotts, buycotts and consumer activism in a global context: An overview. Management & Organizational History, 5(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744935910361644

- Hestermann, J. (2016). Vor der Diplomatie: Deutsch-israelische Wissenschaftsbeziehungen als „Brückenbauer“? Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook, 15, 399–418.

- Jensen, H. R. (2008). The Mohammed cartoons controversy and the boycott of Danish products in the Middle East. European Business Review, 20(3), 275–289.

- Kaikati, J. G. (1978). The Arab boycott: Middle East business dilemma. California Management Review, 20(3), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165280

- Kleinschmidt, C. (2010). Von der “Shilumim” zur Entwicklungshilfe: Deutsch-israelische Wirtschaftskontakte 1950-1966. Vierteljahrschrift Für Sozial- Und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 97(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.25162/vswg-2010-0006

- Knie, A. (2002). Wankel-Mut in der Autoindustrie: Anfang und Ende einer Antriebsalternative. Edition Sigma.

- Kobrak, C., & Wüstenhagen, J. (2006). International investment and Nazi politics: The cloaking of German assets abroad, 1936–1945. Business History, 48(3), 399–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790600791821

- Kostova, T., Roth, K., & Dacin, M. T. (2008). Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159458

- Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. The Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/259037

- Labelle, M. (2014). De-coca-colonizing Egypt: Globalization, decolonization, and the Egyptian boycott of Coca-Cola, 1966–68. Journal of Global History, 9(1), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022813000521

- Levy, J. A. (2020). Black power in the boardroom: Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the anti-apartheid struggle. Enterprise & Society, 21(1), 170–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2019.32

- Lewis, D. L. (1976). The public image of Henry Ford: An American folk hero and his company. Wayne State University Press.

- Li, J., Shapiro, D., Peng, M. W., & Ufimtseva, A. (2022). Corporate diplomacy in the age of U.S.–China rivalry. Academy of Management Perspectives, 36(4), 1007–1032. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2021.0076

- Losman, D. L. (1972). The Arab boycott of Israel. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 3(2), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743800024831

- Lubinski, C. (2014). Liability of foreignness in historical context: German business in preindependence India (1880–1940). Enterprise and Society, 15(4), 722–758. https://doi.org/10.1093/es/khu045

- Lubinski, C., & Wadhwani, D. (2020). Geopolitical jockeying: Economic nationalism and multinational strategy in historical perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 41(3), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3022

- Ludwig, E., & Smith, J. (1978). The business effects of the antiboycott provisions of the export administration amendments of 1977: Morality plus pragmatism equals complexity. Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law, 8(3), 581–660.

- McDonnell, M.-H., & King, B. (2013). Keeping up appearances: Reputational threat and impression management after social movement boycotts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(3), 387–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839213500032

- Meyer, K. E., Fang, T., Panibratov, A. Y., Peng, M. W., & Gaur, A. (2023). International business under sanctions. Journal of World Business, 58(2), 101426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2023.101426

- Meyer, K. E., & Thein, H. H. (2014). Business under adverse home country institutions: The case of international sanctions against Myanmar. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.04.005

- Michaely, M. (1975). Foreign trade regimes and economic development: Israel. Columbia University Press.

- Minefee, I., & Bucheli, M. (2021). MNC responses to international NGO activist campaigns: Evidence from Royal Dutch/Shell in apartheid South Africa. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(5), 971–998. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00422-5

- Mohliver, A., Crilly, D., & Kaul, A. (2023). Corporate social counterpositioning: How attributes of social issues influence competitive response. Strategic Management Journal, 44(5), 1199–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3461

- Mordhorst, M. (2014). Arla and Danish national identity: Business history as cultural history. Business History, 56(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.818422

- Pitteloud, S. (2023). Have faith in business: Nestlé, religious shareholders, and the politicization of the church in the long 1970s. Enterprise & Society, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2023.7

- Raaijmakers, A. G. M., Vermeulen, P. A. M., Meeus, M. T. H., & Zietsma, C. (2015). I need time!: Exploring pathways to compliance under institutional complexity. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0276

- Reckendrees, A., Gehlen, B., & Marx, C. (2022). International business, multinational enterprises and nationality of the company: A constructive review of literature. Business History, 64(9), 1567–1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2022.2118718

- Reingold, R. N., & Lansing, P. (1994). An ethical analysis of Japan’s response to the Arab boycott of Israel. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857451

- Rieger, B. (2010). From people’s car to new Beetle: The transatlantic journeys of the Volkswagen Beetle. Journal of American History, 97(1), 91–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40662819 https://doi.org/10.2307/jahist/97.1.91

- Rieger, B. (2013). The people’s car: A global history of the Volkswagen Beetle. Harvard University Press.

- Rivlin, P. (2010). The Israeli economy from the foundation of the state through the 21st century. Cambridge University Press.

- Saltoun, A. M. (1978). Regulation of foreign boycotts. The Business Lawyer, 33(2), 559–603. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40685850

- Sarna, A. J. (1986). Boycott and blacklist: A history of Arab economic warfare against Israel. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Soule, S. A., Swaminathan, A., & Tihanyi, L. (2014). The diffusion of foreign divestment from Burma. Strategic Management Journal, 35(7), 1032–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2147