Abstract

While we know that professionalization improves outcomes for teachers, education policy has effectively deprofessionalized teachers, especially those who serve immigrant English Learners. Based on a three-year case study, this paper explores how teachers in an immigrant-serving school exercised autonomy and authority over their instruction and professional development. Drawing on staff interviews and observations of teacher meetings, this paper further describes how these professional conditions positioned teachers to better serve their student population. Our study also revealed the underlying conditions that made teacher autonomy possible, including the negotiation of external policy and a robust model of shared decision-making. By providing rich descriptions of teacher work, this paper moves beyond abstractions of professionalization and toward a concrete set of practices that other schools can employ to reprofessionalize teachers. Moreover, we argue that reprofessionalizing teachers can better equip teachers to create learning opportunities that are responsive to students’ needs. In so doing, the paper speaks to the potential short-sightedness of policies that further undermine teacher autonomy.

Teachers are entrusted with one of our nation’s greatest responsibilities—educating our children and youth—but with little authority over how to do so. Ingersoll (Citation2007) describes this unique paradox of the teaching profession as “long on responsibility and short on power” (p. 194). Control over one’s work, he argues, is a defining, if not the defining, characteristic of professionalism. Jobs that position individuals as professionals grant those individuals substantial authority and a large degree of self-governance because they are seen as experts (Ingersoll et al., Citation2011).

The professionalization of teachers, in particular, positively affects teacher commitment, satisfaction, and retention (Ingersoll, Citation1997; Smith & Ingersoll, Citation2004). Teaching, however, has been deprofessionalized over several generations as teachers have been cast as a primary source of education crises rather than a critical lever for change (Goldstein, Citation2014; Kumashiro, Citation2012; Race, Citation2002). Despite what we know about how professionalization improves outcomes for teachers, teachers tend to have little authority or decision-making power in their schools. Consider that most teachers do not choose the instructional and curricular materials they use; have little say over the disciplinary structures in place at their schools; are rarely consulted about class size and configuration or even the subject and grade level they will teach; and are typically uninvolved in budgetary decisions (Menken & Garcia, Citation2010; Pease-Alvarez et al., Citation2010). Try to superimpose these conditions on a highly professionalized occupation (e.g., lawyer, doctor) and it is nearly impossible to imagine how individuals within the profession could function with such little autonomy.

Teachers who are typically assigned to teach students designated as immigrant English Learners (ELs)Footnote1 in their schools are afforded even less autonomy. These teachers are typically under greater surveillance (or work in schools under greater scrutiny) and forced to comply with policy demands related to curriculum, testing, and language requirements (Martin, Citation2016; Sunderman, Kim, & Orfield, Citation2005). They also tend to be physically marginalized in their own buildings, separated from the rest of the staff, and deprofessionalized through overt and subtle messaging about their skills and value (Gichiru, Citation2014). These conditions, which fail to recognize teacher expertise or provide authentic opportunities for growth, contribute to higher rates of attrition (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, Citation2017; Ingersoll et al., Citation2018; Wronowski & Urick, Citation2019, Citation2021) and ultimately negative outcomes for students (Ronfeldt et al., Citation2013; Sorensen & Ladd, Citation2020).

Based on a 3-year case study of an immigrant-serving school, this paper explores the professional conditions that shape the practice of teachers who serve immigrant ELs. The questions guiding our study were twofold: How, if at all, do the professional conditions in this site promote teacher autonomy and authority? How, if at all, do these conditions influence learning opportunities for immigrant ELs? Drawing on staff interviews and observations of professional meetings, our findings showed how teacher autonomy and authority over curriculum and professional growth positioned teachers to better serve their students. Our study also revealed important organizational features that promoted teacher autonomy, including the school’s negotiation of external policy and a robust model of shared decision-making. The findings from this study aim to contribute to the sociology of teaching and inform educational practice by showing how reprofessionalizing teachers can benefit teachers and cultivate more responsive schooling for students who are often denied access to fully professionalized teachers.

The current context: School accountability and the deprofessionalization of teachers

Teaching is not a highly esteemed profession in the United States. Research that compares teaching to other occupations on a range of characteristics associated with professional work (e.g., credentialing, degree of specialization, compensation, etc.) finds that teaching is, at best, considered a “semi-profession” (Ingersoll et al., Citation2011). The marriage of high-stakes accountability with market and managerial reforms has produced what sociologists refer to as the “new professionalism” (Anderson & Cohen, Citation2015), conceptualized by Evetts (Citation2011) as a shift from “notions of partnership, collegiality, discretion and trust to increasing levels of managerialism, bureaucracy, standardization, assessment and performance review” (Anderson & Cohen, Citation2015; Evetts, Citation2011, p. 407).

Policy reforms in the U.S., including No Child Left BehindFootnote2 (and its replacement, Every Student Succeeds Act) have called to hold teachers accountable for student outcomes. Moreover, explicit performance standards and standardized curricula have led to heightened control and surveillance of teachers and a reduction of teacher authority and professional influence (Ball et al.,Citation1996; Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, Citation2018; Martin, Citation2016). Ingersoll aptly describes that the deterioration of teaching as a profession is the logical result of education policy which increasingly seeks to “teacher-proof” education. Under current accountability policies, teachers frequently lack the ability to make decisions about curriculum, how students are grouped in their classes, how space is used, or how discretionary funds for classroom materials are spent (Ingersoll, Citation2007). This deprofessionalization of teachers has demoralized teachers and constrained the scope of teaching and learning as teachers increasingly focus on evaluation targets and protecting themselves against negative evaluation rather than the pedagogical needs of students (Holloway, Citation2019; Villavicencio et al., Citation2021).

Professionalization and the teachers of immigrant ELs

The heightened control and surveillance of teaching under current accountability regimes most deeply affects teachers who serve populations of students who do not test well on standardized tests (including ELs and students with disabilities), which are the metrics used to measure success under these policies (Berliner, Citation2011; Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, Citation2018; Martin, Citation2016). A few scholars have engaged in research focused on the professional identities and status of EL teachers, providing insight into the deprofessionalization and isolation of these teachers. Harper et al. (Citation2008) find that the policies that emerged from the language in laws, such as NCLB, have led to devaluing teacher expertise. In outlining that ESL (English as a Second Language) teachers do not need to be “highly qualified,” the policy “reinforces the common assumption that teaching ELs requires little more than a set of pedagogical modifications applied to other content areas” (p. 271). The proliferation of top-down mandates has also decreased the authority of EL teachers over their work as they are increasingly required to defer to policies that fail to consider students’ needs or teachers’ professional knowledge (Menken & Garcia, Citation2010; Pease-Alvarez et al., Citation2010).

In addition to being devalued, scholars from the U.S., United Kingdom, Australia, and Taiwan find that teachers of ELs are physically marginalized within schools (e.g., teaching in makeshift and inferior spaces) and professionally marginalized—unable to access support from colleagues (Arkoudis, Citation2006; Creese, Citation2002; Davison, Citation2006; Ernst-Slavit & Wenger, Citation2006; Gardner, Citation2006; Liggett, Citation2010). Feeling demoralized, the teachers in Liggett’s (Citation2010) study described their status as “being at the bottom,” “a little bit marginalized,” and “shoved aside.” They identified a lack of structures for communication or collaboration between general education teachers and teachers serving ELs that ultimately negatively influenced students’ academic outcomes. Ernst-Slavit and Wenger’s (Citation2006) study of bilingual paraprofessionals also shows that even though paras were important advocates for ELs and served as “hidden teachers,” they were overlooked and subject to inequitable school staffing and finance policies.

Prior literature highlights the importance of recognizing and developing the expertise of EL teachers (Babinski et al., Citation2018; Umansky et al., Citation2018). For example, in a survey of EL teachers in California (Gándara et al., Citation2005), teachers who reported greater preparation in terms of professional development (PD) related to teaching ELs and collaboration with peers reported greater teacher confidence in working with their students. Similarly, a randomized control trial of effective PD for teaching ELs showed how engaging in productive collaboration with general education teachers improved instructional practice (Babinski et al., Citation2018). Indeed, though the policy landscape has resulted in the deprofessionalization of teaching at large, there are sites of resistance against a policy environment that might otherwise determine the professional identity of teachers. Villavicencio et al. (Citation2021) documented how a school leader strategically resisted teacher evaluation policies that she felt were incoherent with the learning needs of teachers and ELs in her school. Similar research considers how teacher collaboration empowered teachers to respond to the needs of immigrant students (Bartlett & García, Citation2011; Villavicencio et al., Citation2021). This paper contributes to this literature by exploring the professional conditions in such a site of resistance, showing how they have served to reprofessionalize EL teachers whose autonomy and authority have historically been undermined.

Conceptual framework: Teacher professionalization and authority

Building on an understanding of the relationship between one’s identity and practice (Wenger, Citation1998), this study conceptualizes teacher professional identity as a dynamic process in which individuals make sense of their everyday experiences within the broader discursive context to build a set of beliefs of what it means to work within the teaching profession (Flores & Day, Citation2006; Weiner & Torres, Citation2016). Teachers’ conceptions of their professional identities shift over time based on interactions with the local contexts of schools as well as prevailing discourses and policy conditions (Day et al., Citation2006; Ruohotie-Lyhty, Citation2013). While there is much debate about what constitutes professionalism within teaching, sociologists of education have explored the different dimensions of professionalization within the field.

Ingersoll et al. (Citation2011), in particular, developed a model to assess the professionalization of teachers in different types of schools across the country that included the following characteristics: credentialing, induction of new members, professional development opportunities, degree of specialization, decision-making authority, compensation, and prestige. One key area of their analysis was professional authority—or the level of control teachers have over the work for which they are responsible—including the influence that faculty have over hiring and school policies as well as the degree of individual autonomy teachers have over their planning and teaching in their classrooms (Ingersoll et al., Citation2011). As Ingersoll and colleagues argue, “The rationale behind professional authority is to place substantial levels of control into the hands of the experts—those who are closest to and most knowledgeable of the work” (p. 207).

Research on teacher professionalization and commitment finds that when teachers have a voice in decision-making, they are more likely to be invested in their work. Ingersoll (Citation2007) finds that: “Schools in which teachers have more control over key schoolwide and classroom decisions have fewer problems with student misbehavior, show more collegiality and cooperation among teachers and administrators, have a more committed and engaged teaching staff, and do a better job of retaining their teachers” (para. 17). This echoes earlier findings, which suggested that increased participation of teachers in school decision making resulted in shared ownership of teachers’ work (Duke et al., Citation1980; Lieberman, Citation1988; Wasley Citation1991). This paper contributes to this scholarship by empirically examining the central role of teachers’ autonomy and authority in promoting teacher professionalization. Further, while this body of research provides important insights into the relationship between teacher professionalization and teacher commitment and retention, it does not provide insights into what these dimensions of teacher professionalization look like on the ground or the conditions that sustain them. Our research makes an important contribution to the literature in this area by examining school-level practices that contribute to teacher professionalization and providing rich empirical examples that show how teacher professionalization contributes to collective responsibility for immigrant ELs.

Methods

Research context

This paper draws on data from a 3-year study of a public high school network in New York City that serves recently arrived immigrant students who are classified as English Learners. The Every Student Succeeds Act defines a recently arrived immigrant English Learners as a student who has been enrolled in U.S. schools for less than 12 months. Recently arrived immigrant English learners include many different subgroups, including students with refugee status, unaccompanied minors, and students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFEs) (Umansky et al., Citation2018). Given their recently arrived status, these students not only share a need to acquire English proficiency, but they also often have physical, social, and mental needs that other EL students may not. These may be related to dislocation, trauma, limited or interrupted formal schooling, and adjustment to the norms of a new community (Short & Boyson, Citation2012; Suárez-Orozco, et al., Citation2009). We selected this network of schools for study because of the students they serve and their notable academic outcomes (Gross, Citation2017; Hernández, et al. Citation2019; Stavely, Citation2019). Students who attend these schools come from 119 countries and speak 90 different languages. Nearly all—90%—are considered low-income and many are undocumented. The core philosophy of the network includes integrating language learning into all subjects and developing teachers to understand the broader educational and non-educational needs of immigrant ELs, while employing an asset-based lens to recognize the capital and resources of the communities they serve (Villavicencio et al., Citation2021).

The larger study included in-depth case studies of two network schools and two non-network schools to explore the conditions, policies, and practices employed by network schools that are related to their success. We used both within-case and cross-case analysis to compare how similar processes related to serving immigrant ELs were enacted across different educational contexts (Bartlett & Vavrus, Citation2016). This paper, however, focuses on one of the cases from the broader set of case studies—Crossroads School for International Learners (a pseudonym)—because it represents an extreme or exemplary case (Yin, Citation2017) of a school that supports teacher professionalization among teachers of immigrant ELs. In particular, case study data for this paper includes rich illustrations of the school’s teacher induction processes, curriculum planning meetings, and teacher portfolios to show how professional conditions in this site promote teacher authority and autonomy, ultimately creating better learning opportunities for immigrant ELs.

Study site

Founded in the mid-1990s, Crossroads is located in New York City and shares a building with two other high schools. Within a two-block radius of the school are restaurants, shops, public transit, and university buildings. Crossroads is the most ethnically and linguistically diverse of all the schools within the network: Its students come from 30 countries or regions such as China, Ecuador, Haiti, Mexico, Tibet, Ecuador, Uzbekistan, and Yemen. Moreover, there is not one majority group in terms of country of origin or home language. provides an overview of the school’s enrollment and student population. Almost half of its student population is Latinx (45%), followed by Asian (24%) and Black (21%) students. In the years that we conducted research in Crossroads, all incoming ninth graders were designated ELs, but only three-fourths of total enrolled students were classified as ELs, since many students test out of the official designation by the time they graduate. The 4-year graduation rate for Crossroads at the time of our study was 80%, which was higher than the city average of 77.3% for the same year and far higher than the city average for ELs, which was 41%.

Table 1. School characteristics.

As mentioned above, Crossroads is part of a network of schools serving recently arrived immigrant students. Recognizing that effectively serving newcomer immigrant ELs requires extensive PD, the network provides a series of induction workshops and an annual conference held by the network, while creating learning communities among practitioners in the network. Network schools also utilize school teams to foster collaboration focused on developing curricula to address students’ needs. In addition, teachers participate in school-based PD throughout the year that is organized by a school-based PD committee. They also meet weekly with their instructional teams and in disciplinary groups to design interdisciplinary project-based curricula for their students that is aligned with state standards. Rather than rely on established or mandated curricula, these teachers co-design thematic unit plans that span across content areas, are linguistically responsive, and are culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, Citation1995).

Positionality

At the heart of this research is a commitment to understanding the conditions that will best serve immigrant youth and a critical stance toward policy and practice that further marginalizes historically underserved students. To that end, the authors of this paper share an interest in research that not only surfaces the unique challenges faced by immigrant youth, but sheds light on how schools and educators can design alternative environments that defy traditional norms of education. These commitments are born out of our personal and professional experiences: Each author was once a teacher serving immigrant communities and three of us are also children of immigrants. Collectively, our research commitments and lived experiences influenced the generation of our research questions, our selection of an exemplary site, and our interpretation of the data through an asset-based lens. In terms of our specific roles on the project, every author participated in data collection at Crossroads throughout the study. Two of the researchers belong to the racial/ethnic groups that represent large populations of the school, which provided us with a level of cultural familiarity within the site and made communication in Spanish and Mandarin possible, further engendering trust and rapport. The authors engaged in data analysis and writing collectively, leveraging both our unique insights and shared sensemaking as researchers aspiring to improve education for immigrant youth.

Data collection

This paper draws on (a) five 60-minute interviews with school leaders including the principal, assistant principals, and guidance counselors; (b) two 45-minute focus group interviews with ninth and 10th grade teachers and two 45-minute focus groups with four 11th and 12th grade teachers; (c) six observations of 45-minute professional meetings; and (d) reviews of relevant documentation, such as meeting agendas and teacher portfolios. In particular, we designed interview protocols to help us understand the roles and responsibilities of teachers within the larger mission of the school. We designed protocols for focus groups with teachers to capture details about the school’s professional community, including teacher collaboration, professional growth and evaluation, and participation in school decision-making. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

To triangulate interview data, we also selected several professional meetings to observe, including grade-level planning meetings and teacher portfolio meetings used by Crossroads in lieu of a traditional teacher evaluation. Team members wrote extended field notes after each observation following a chronology of activities and events (Emerson et al., Citation1995). Our observation protocol also paid specific attention to questions related to the professional community, including interpersonal dynamics, meeting structures, opportunities for collaboration, and teacher decision-making. In total, we collected qualitative data over 30 days of fieldwork, which occurred from fall 2017 to fall 2019; the interviews and observations reported on in this paper represent a total of 12.5 hours. The variety of data sources and methods allowed the researchers to triangulate both the method and data to create a comprehensive portrait of teacher professionalization at Crossroads (Patton, Citation2002).

Data analysis

The research team used Dedoose, an online qualitative analysis platform, to collectively analyze transcripts and fieldnotes. To ensure the reliability of our analyses, we employed a multi-step and interactive coding process (Hruschka et al., Citation2004), which included team discussion to create a coding scheme, testing the scheme with data, and modifying the scheme to achieve strong interrater reliability. For the larger study, our first-round coding generated an initial codebook with seven broad parent codes: leadership, school culture, professional conditions, curriculum/instruction or pedagogy, immigrant context, community/partners, and policies. To answer the research questions guiding this paper, we focused our analysis on the data coded as professional conditions. Within this parent code, we created six subcodes, including collaboration, hiring and enculturation, and teacher autonomy (displayed in ). For each of these subcodes, the authors produced analytic memos (Yin, Citation2017) to capture the specific practices, routines, and norms that characterized each (e.g., the facilitation of teacher team meetings to produce an in-house curriculum). The team then analyzed our memos to draw out cross-cutting themes about how the school’s professional conditions promoted teacher autonomy and authority and how these affordances allowed teachers to be responsive to students.

Table 2. Codes related to professional conditions with corresponding definitions.

Findings

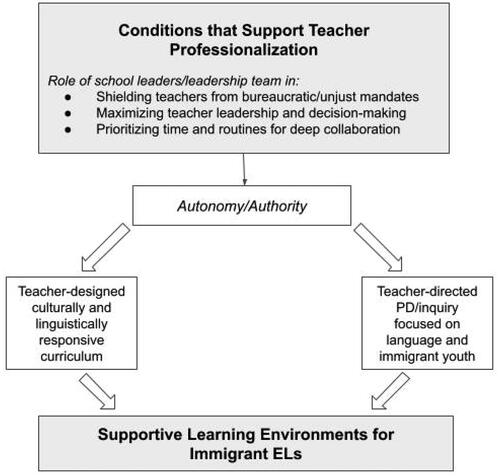

Our study of the professional conditions at Crossroads School for International Students revealed a high level of autonomy and authority among teachers in two areas of their work. First, teachers displayed total decision-making over curriculum and instruction. Teachers described how this expression of authority signaled a level of respect for their expertise and provided them the freedom to collectively create culturally and linguistically responsive classrooms for immigrant ELs. Second, we found that teachers at Crossroads also exercised decision-making over their professional development and evaluation, thereby allowing teachers to build the capacities required to serve the population. To further inform educational practice in other contexts, we end by describing important organizational features at Crossroads that promote teacher autonomy and authority. displays the relationships between these conditions, the ways teachers are professionalized, and the benefits for immigrant ELs.

“I was a teacher on a cart”: Re-positioning teachers as instructional experts

Many teachers of ELs face professional conditions that heavily dictate and constrain their teaching, thereby communicating a lack of respect for their expertise and pedagogical skills (Martin, Citation2016; Sunderman et al., Citation2005). Compounding this disadvantage, EL teachers are often isolated from other teachers—similar to how many of their students are physically and academically marginalized from their peers. Consider the way this Crossroads teacher remembers her student teaching experience:

I was a teacher on a cart. We had a kind of sandwich board-style whiteboard that was on wheels with everything I could manage to put on it. Then we wheeled into a room and sat in the corner. Some of those students had been in the country for less than a year. Some of those students had been labeled as ELs for five years, and everybody was, like, “What’s wrong with them?” We were either in the corner of the classroom or, when I asked for additional space, we were put into the library. We were always pushed off into another space. It was never this idea of, these students are learning at the same time as everyone else. It was always, “You are separate and you get what’s on this cart.”

In contrast, the positioning of teachers as instructional experts at Crossroads became evident in how teachers described their work. In focus groups with teachers across the grade levels, respondents consistently used the word “freedom” to characterize their teaching. A seasoned 11th grade teacher described:

Before coming to this school, I was very much hamstrung by the curriculum. It was only after coming here that I felt that I was actually teaching because I was allowed to teach what I wanted, how I wanted, and given the freedom to do what I needed to do.

As a point of comparison, coming from a very traditional school was very different for freedom in curriculum writing and how I structured my class. When I arrived here and asked what I should teach, the principal said, “Whatever you think is important.” The respect for me as a professional was very different.

Teachers also described how authority over curriculum and instruction allows them to create learning opportunities that are uniquely beneficial for immigrant ELs. When asked about why she appreciated teaching at Crossroads, one 9th and 10th grade teacher explained:

I would say, the opportunity to design my own curriculum. Also, the encouragement I’ve gotten to look at the curriculum I’m creating from the perspective of the students is really powerful. To think: What will the students get out of this? Will they actually get that or what will their experience be?

The thing in this school is that you’re allowed to work on your own curriculum and have the freedom to teach. I think the difference between this school and the other school I worked at is the focus is on advocating for ELs and immigrant students.

Though the teachers at Crossroads emphasized the “freedom” to teach what and how they want, autonomy was not synonymous with isolation. Crossroads teachers meet twice a week in grade-level teams to collectively create project-based, interdisciplinary units. Our observations of these curriculum planning meetings revealed a process that is driven by teacher expertise and motivated by the identities, experiences, and needs of students. We observed, for example, how teachers co-generated an interdisciplinary project on access to clean water designed to integrate language instruction, math, and science content. The unit was culturally responsive, allowing students to link their own backgrounds to the topic of inquiry by drawing on data from their native countries (Gay, Citation2010; Miranda & Cherng, Citation2018; Sepúlveda, Citation2011). It was also academically rigorous and linguistically supportive, allowing students to conduct research and speak in their native language with peers and providing opportunities to practice public presentations in English. Thus, an important byproduct of a collaborative process fully led by teachers is curricula that is responsive to the students they serve. As one teacher shared:

Instead of being asked, “Why didn’t you teach standards 3a through 5b?,” it’s more like, “Well, we believe that you are teaching students what they need to know, because you’re in there with them. You’re the expert on what they need,” which is not easy, but is very validating as a teacher.

Leveraging teacher expertise: Teacher-directed PD and evaluation

While professional development (PD) and teacher evaluation are typically externally driven and mandated processes, teachers drive both at Crossroads. These processes thus reposition teachers as professionals with expertise and specialized knowledge, rather than deprofessionalized technicians whose function is to comply with standards, curricula, and procedures determined by outsiders.

To ensure that professional development is aligned with teacher and student needs, a PD committee (comprised of teacher representatives from every grade team) identifies areas of professional growth to explore throughout the year. Topics in the recent past have included mastery grading, trauma-informed approaches, mentorship for student portfolio assessments, and restorative justice practices. Generally, Crossroads prefers to conduct in-house PD sessions led by their own educators. As one of the assistant principals explained, “I think the fact that we’ve got so many people with a lot of experience…people prefer to leverage the experience of their colleagues and find that more meaningful than bringing someone in from outside.” Teachers at Crossroads also lead inter-school PD and conduct intervisitations across schools in their network. This approach to PD assumes that teachers have valuable expertise and serves to reprofessionalize teachers who have been in environments where PD is dictated and led by outsiders (Ingersoll et al., Citation2011). Moreover, teacher-led PD allows teachers to center the needs of their population in the PD they provide, thus ensuring that best practices for immigrant ELs are at the heart of professional learning.

To grant teachers more decision-making over their own learning and growth, leaders at Crossroads also developed an alternative teacher evaluation system hand-in-hand with teachers. The PROSE system,Footnote3 as implemented at Crossroads, incorporates substantial teacher agency within the school’s teacher evaluation system. In a document that describes the evaluation system to teachers, the principal wrote:

The goal is to create a professional learning experience that really moves our practice forward. You decide the focus, so we know it will be relevant. The key to growth is finding that space that you really need to grow into; to have the honesty and vulnerability to share that with our colleagues; knowing that together and through our collective practice we will strengthen our entire community.

More importantly, this approach to professional learning allowed for greater responsiveness to student needs versus adherence to external mandates. The principal explained how PROSE encourages the type of flexibility and adaptability that teachers need to be successful teachers of ELs. Describing the traditional teacher evaluation system as too rigid to be responsive to the diversity of an EL classroom, she shared:

While I think the portfolio process is ideal for all teachers, I think the impact would be most profound on teachers of ELs. The most powerful teachers of ELs are the ones who are flexible in their understanding of what is possible in the classroom [and] willing to differentiate their curriculum and pedagogy to meet the incredibly diverse linguistic and academic needs of their students.

Creating conditions for teacher autonomy and authority

To illustrate how schools can promote autonomy and authority in other educational contexts, we aim here to describe the organizational conditions that made both possible. These include school leaders (or leadershop teams) taking an active role in protecting teachers from ill-conceived external policies and employing multiple structures to ensure teachers are actively involved in schoolwide decision-making.

First, the leadership teamFootnote4 at Crossroads shields teachers from bureaucratic mandates and students from unjust mandates. One example of a long-lasting policy shift that the school leadership team advocated for dates back to 1995 when the New York State Education Department granted Crossroads a waiver to use Performance Based Assessment Tasks (PBATs) to determine graduation readiness instead of standardized exit exams. The shift from being a testing school to a performance assessment school created conditions for teachers to have more freedom and autonomy in how and what they taught their students. The principal explained, “The waiver encourages openness, creativity because teachers don’t have to be burdened with test prep.” She argued that in testing schools, conditions demand that teachers work independently to make sure their students’ test scores are high enough not to invite scrutiny. In contrast, the PBATs encourage interdisciplinary collaboration and allow teachers to use a project-based approach that is more effective for ELs (Miranda & Cherng, Citation2018). We and other scholars have described the capacity to maneuver around policy as creative policy negotiation (Jaffe-Walter & Villavicencio, Citation2023), creative insubordination (Buskey & Pitts, Citation2009), or creative compliance (Tienken, Citation2019). The term signifies when school leaders find avenues to influence bureaucratic and legal structures in ways that “do less harm, do more good, and maintain ethics of caring and justice within the educational community in which they lead” (Tienken, Citation2019, p. 19).

Second, the leaders at Crossroads incentivize teachers to be involved in school-level policy and decision-making. All teachers can participate in powerful teacher-led committees and are compensated for the extra work. The Assistant Principal explained:

We have committees for everything. We have a Learning Partners Committee. We have a Mastery Collaborative Committee. [The] Mastery Collaborative Team has been working on a grading software that we would be able to implement school-wide, but we’re going to pilot it first. The LPP Committee has been working on creating the six levels of outcomes for school-wide stuff that we want to implement. Each group is doing things that are all reporting out to the Coordinating Council—

[I]f you’re a first-year teacher, we typically ask that you’re not involved in any of these committees, just because it takes so much to transition … to the [Network’s] model, so we ask them to focus on that their first year. Then, in their second year, teachers typically come to us and tell us what they’re interested in. We had a teacher last year, who said “I don’t think mentoring was organized well this year. This is the feedback I got. Can I be in charge of it next year?” Then, there’s a discussion between the previous person in charge, that person, and the administration. Teachers feel comfortable taking ownership of those roles, and…They come to us with what they’re interested in policy-wise and committee-wise.

The leadership team at Crossroads has created an environment where teachers are shielded from bureaucracy and exercise collective decision-making power. Our findings support literature that establishes the importance of school leaders, and the principal in particular, as key players in school culture creation and maintenance (Brooks et al., Citation2010; Elfers & Stritikus, Citation2014; Umansky et al., Citation2018; Scanlan & López, Citation2014; Theoharis & O’Toole, Citation2011). Participation in collective decision-making is also critical to the reprofessionalization of teaching. Instead of “teacher-proofing” the school, leadership at Crossroads attempts to balance including teachers in the decisions that impact their daily professional lives without burdening them with bureaucratic compliance that does not. Bureaucracy-proofing the school has created the conditions for a school culture that supports teacher professionalization, which we argue is particularly important for teachers of immigrant students who are acquiring a new language while facing the complex challenges associated with their immigrant status. As displayed in , creating supportive structures that increase teacher professionalization ultimately increases teachers’ capacity to respond to the needs of immigrant ELs.

Limitations

We should note a few important limitations related to our data collection and site section. First, our data is limited to the six observations and nine interviews/focus groups we conducted in addition to our analysis of several artifacts relevant to teacher professionalization. While the data we collected yielded rich illustrations of how teachers are reprofessionalized at Crossroads and the influence of these conditions on learning opportunities for immigrant ELs, we recognize that more ethnographic data collection methods that relied on other sources beyond the leaders and teachers we interviewed may have revealed even further complexity, contradictions, and/or changes over time. In addition, the unique features of our site may diminish the potential of replicating these practices in other settings. For example, Crossroads is part of a larger school network that explicitly positions teachers as learners and professionals. Doing so has required that the network buffer policies that erode teacher professionalization by working strategically with local policymakers and other advocates to comply with the terms of policy, while also honoring the internal commitments of the network (Jaffe-Walter, Citation2008). In formulating the portable lessons of our study, it is important to consider how external policies position teachers and the professional conditions that emerge in different schools as a result of those policies. In this case, Crossroads is at an advantage in comparison to many traditional schools that do not have a history of leadership and support focused on empowering teachers to better serve their students within a context that undermines teacher authority. Still, as discussed below, many of the norms and practices employed by this school to reprofessionalize its teachers can be exercised in a variety of other secondary school settings.

Discussion and implications

The findings from this case study illustrate how an immigrant-serving school positions teachers of EL students—teachers who are typically marginalized and isolated within a profession that is already deprofessionalized—as autonomous experts. Drawing on conceptualizations of teacher professionalization (Flores & Day, Citation2006; Ingersoll et al., Citation2011; Weiner & Torres, Citation2016), we describe how teachers are reprofessionalized through autonomy and authority over what they teach and how they learn. We theorize that an important element of teacher professionalization is autonomy and freedom within a thick web of collaboration and learning with peers, not one of isolation behind the doors of an individual classroom (Villavicencio et al., Citation2021). By providing rich descriptions of how this degree of autonomy shapes teacher work, this paper moves beyond abstractions of professionalization and toward a concrete set of practices that other schools can employ to reprofessionalize teachers. These practices include granting teachers authority over curricular content and their own professional learning, while providing the time and resources to pursue both effectively. Doing so communicates to teachers that their expertise is valued and that they can be trusted with the primary mission of their schools—to educate children and youth. Implementing these practices also recognizes that teachers are in the best position to understand the constellation of skills and capacities required to fulfill that mission.

These practices and assumptions lie in stark contrast to the typical experiences of EL teachers in public school settings, as reported by the teachers in our sample and in prior research (Harper et al., Citation2008; Liggett, Citation2010). While schools typically relegate EL teachers to the margins (physically and symbolically), hand them prepackaged curricula to use in their classrooms, and force them to comply with policy mandates focused on raising test scores among underperforming students (Pease-Alvarez et al., Citation2010), the experiences of the teachers in our study site show how teachers can be reprofessionalized vis a vis autonomy and authority over the primary dimensions of their work. Further, by reprofessionalizing teachers, the school has developed collective responsibility for educating their immigrant EL students, such that many traditional structures (e.g., top-down teacher evaluation systems) no longer align with the school’s internal commitments to empowering teachers and students.

Our work also speaks to the underlying conditions—typically established by the school leader or leadership team—that support teacher professionalization and remove some of the barriers to teacher autonomy and decision-making created by the policy environment (see also ).

Shield teachers and students from bureaucratic/unjust mandates. At Crossroads, school leaders creatively negotiated compliance around test mandates and teacher evaluation policies in favor of practices that would allow teachers greater autonomy over the process of assessing student and teacher work. Pushing back against the new professionalization characterized by bureaucracy, standardization, and assessment requires specific capacities (Anderson & Cohen, Citation2015). Leaders that seek to position teachers as professionals will likely need to practice forms of creative compliance (Tienken, Citation2019) to protect teachers from harmful policies that would strip away their power.

Maximize teacher leadership and decision-making. School leaders can also create structures or systems that maximize teacher decision-making. The school leadership team established several committees allowing teachers to play leadership roles in the policies and practices that shape the daily lives of teachers and students.

Create structures that support deep collaboration. At Crossroads, school leaders provide teachers with ample time to collaborate around curriculum, professional development, and several other dimensions of the school community. This finding suggests an important distinction between teacher autonomy and isolation. While teachers need autonomy from top-down directives that come from outside their school community, they simultaneously need opportunities for lateral collaboration with their peers. We posit that teacher professionalization requires establishing norms and routines that allow teachers to work together in meaningful ways that leverage their collective expertise.

This paper contributes to existing scholarship on teacher professionalization, specifically for teachers who serve immigrant ELs. By exploring a site that defies historical patterns of deprofessionalization and isolation, this paper examines the role that teacher autonomy and authority play in promoting teacher professionalization, ultimately improving learning opportunities for immigrant ELs. Prior research has established that the professionalization of teachers is associated with numerous benefits, including teacher commitment, satisfaction, and retention (Ingersoll, Citation1997, Citation2007; Ingersoll et al., Citation2011; Smith & Ingersoll, Citation2004). Our study is consistent with this research, as it highlights the freedom and confidence teachers experienced in this context (especially in comparison to their prior experiences as EL teachers with little autonomy). However, our paper also centers on how teacher professionalization benefits students by empowering teachers to create learning opportunities that are more closely aligned with their students’ needs. In our study site—an immigrant-serving school—this finding is particularly important given that immigrant ELs are often underserved in traditional public schools (Callahan, Citation2013; Cimpian et al., Citation2017; Lukes, Citation2015; Ruiz-de-Velasco et al., Citation2000; Thompson, Citation2013). At Crossroads, teachers shape curriculum and own professional learning based on the content and skills they believe will best serve their students. This paper thus illustrates how the reprofessionalization of teachers cultivates responsive schooling for immigrant students. We further argue that conceptualizations of professionalization should be centered on student responsiveness and that this is particularly impactful for traditionally marginalized students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, we use the term "English Learners" or “ELs” to refer to students designated as English Learners by a state or school’s English proficiency test.

2 Concerns about school and teacher quality drove increased centralized control and accountability mechanisms, culminating in the implementation of No Child Left Behind in the early 2000s. Marked by its emphasis on high-stakes testing, NCLB ushered in a period of education policy that expanded the reach of external entities over schools, leaving teachers with even less influence over teaching and learning than they had previously had.

3 PROSE, or the Progressive Redesign Opportunity Schools for Excellence, is an NYC initiative developed by the teacher’s union designed to allow schools with a proven track record of success to create innovations in one more of the following five areas: distributed leadership structures, extending the school schedule, support for increased diversity in student enrollment, teacher intervisitation and interdisciplinary projects.

4 In this context, the “leadership team” includes the principal and assistant principals, teacher leaders, a literacy specialist, counselor, social worker, and the librarian.

References

- Anderson, G., & Cohen, M. (2015). Redesigning the identities of teachers and leaders: A framework for studying new professionalism and educator resistance. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23, 85. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.2086

- Arkoudis, S. (2006). Negotiating the rough ground between ESL and mainstream teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(4), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb337.0

- Babinski, L. M., Amendum, S. J., Knotek, S. E., Sánchez, M., & Malone, P. (2018). Improving young English learners’ language and literacy skills through teacher professional development: A randomized controlled trial. American Educational Research Journal, 55(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217732335

- Ball, S. J., Bowe, R., & Gewirtz, S. (1996). School choice, social class and distinction: The realization of social advantage in education. Journal of Education Policy, 11(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093960110105

- Bartlett, L., & García, O. (2011). Additive schooling in subtractive times: Bilingual education and dominican immigrant youth in the heights. Vanderbilt University Press.

- Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2016). Rethinking case study research: A comparative approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Berliner, D. (2011). Rational responses to high stakes testing: The case of curriculum narrowing and the harm that follows. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2011.607151

- Brooks, K., Adams, S. R., & Morita-Mullaney, T. (2010). Creating inclusive learning communities for ELL students: Transforming school principals’ perspectives. Theory into Practice, 49(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841003641501

- Buskey, F. C., & Pitts, E. M. (2009). Training subversives: The ethics of leadership preparation. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(3), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170909100312

- Callahan, R. (2013). The English learner dropout dilemma: Multiple risks and multiple resources (California Dropout Research Project Report No. 19). University of Santa Barbara

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute.

- Cimpian, J. R., Thompson, K. D., & Makowski, M. (2017). Evaluating English learner reclassification policy effects across districts. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1_suppl), 255S–278S. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216635796

- Creese, A. (2002). The discursive construction of power in teacher partnerships: language and subject specialists in mainstream schools. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), 597–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588242

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute.

- Davison, C. (2006). Collaboration between ESL and content teachers: How do we know when we are doing it right? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(4), 454–475. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb339.0

- Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600775316

- Duke, D. L., Showers, B. K., & Imber, M. (1980). Teachers and shared decision making: The costs and benefits of involvement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 16(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X8001600108

- Elfers, A. M., & Stritikus, T. (2014). How school and district leaders support classroom teachers’ work with english language learners. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(2), 305–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X13492797

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

- Ernst-Slavit, G., & Wenger, K. J. (2006). Teaching in the margins: The multifaceted work and struggles of bilingual paraeducators. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 37(1), 62–81. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2006.37.1.62

- Evetts, J. (2011). Professionalism in turbulent times: Challenges to and opportunities for professionalism as an occupational value. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 27(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.2703

- Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002

- Gándara, P., Maxwell-Jolly, J., Driscoll, A. (2005). Listening to teachers of English language learners: A survey of California teachers’ challenges, experiences, and professional development needs. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edssch&AN=edssch.oai%3aescholarship.org/ark%3a/13030/qt6430628z&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Gardner, S. (2006). Centre-stage in the instructional register: Partnership talk in primary EAL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(4), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb342.0

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.) Teachers College Press.

- Gichiru, W. (2014). Struggles of finding culturally relevant literacy practices for Somali students: Teachers’ perspectives. New England Reading Association Journal, 49(2), 67.

- Goldstein, D. (2014). The teacher wars: A history of America’s most embattled profession. Doubleday.

- Gross, N. (2017). The schools transforming immigrant education. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/07/how-america-educates-immigrants/533484/

- Harper, C. A., de Jong, E. J., & Platt, E. J. (2008). Marginalizing English as a second language teacher expertise: The exclusionary consequence of no child left behind. Language Policy, 7(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-008-9102-y

- Hernández, L., Darling-Hammond, L., Adams, J., Bradley, K., Duncan-Grand, D., Roc, M., Ross, P. (2019). Deeper learning networks: Taking student-centered learning and equity to scale. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/deeper-learning-networks-report

- Holloway, J. (2019). Teacher evaluation as an onto-epistemic framework. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(2), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1514291

- Hruschka, D. J., Schwartz, D., St. John, D. C., Picone-Decaro, E., Jenkins, R. A., & Carey, J. W. (2004). Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods, 16(3), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04266540

- Ingersoll, R. (1997). The recurring myth of teacher shortages. Teachers College Record, 99(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819709900113

- Ingersoll, R. (2007). Short on power, long on responsibility (pp. 129). GSE Publications.

- Ingersoll, R. M., Sirinides, P., & Dougherty, P. (2018). Leadership matters: Teachers’ roles in school decision making and school performance. American Educator, 42(1), 13.

- Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2011). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning math and science teacher attrition. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

- Jaffe-Walter, R. (2008). Negotiating mandates and memory: Inside a small schools network for immigrant youth. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 110(9), 2040–2066. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811000907

- Jaffe-Walter, R., & Villavicencio, A. (2023). Leaders’ negotiation enactment of teacher evaluation policy in immigrant-serving schools. Educational Policy, 37(2), 359–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048211015614

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2012). Bad teacher: How blaming teachers distorts the bigger picture. Teachers College Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Lieberman, A. (1988). Building a professional culture in schools. Teachers College Press.

- Liggett, T. (2010). A little bit marginalized: The structural marginalization of English language teachers in urban and rural public schools. Teaching Education, 21(3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476211003695514

- Lukes, M. (2015). Latino immigrant youth and interrupted schooling: Dropouts, dreamers and alternative pathways to college. Multilingual Matters.

- Martin, P. (2016). Test-based education for students with disabilities and English language learners: The impact of assessment pressures on educational planning. Teachers College Record, 118(14), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811611801409

- Menken, K., & Garcia, O. (Eds.). (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymakers. Routledge.

- Miranda, C. P., & Cherng, H. Y. S. (2018). Accountability reform and responsive assessment for immigrant youth. Theory into Practice, 57(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2018.1425817

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Pease-Alvarez, L., Samway, K. D., & Cifka-Herrera, C. (2010). Working within the system: Teachers of English learners negotiating a literacy instruction mandate. Language Policy, 9(4), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-010-9180-5

- Race, R. (2002). Teacher professionalism or deprofessionalisation? The consequences of school-based management on domestic and international context. British Educational Research Journal, 28(3), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920220137494

- Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831212463813

- Ruiz-de-Velasco, J., Fix, M. E., & Clewell, B. C. (2000). Overlooked and underserved: Immigrant students in U.S. secondary schools. Urban Institute.

- Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2013). Struggling for a professional identity: Two newly qualified language teachers’ identity narratives during the first years at work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 30, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.11.002

- Scanlan, M., & López, F. A. (2014). Leadership for culturally and linguistically responsive schools. Routledge.

- Sepúlveda, E. (2011). Toward a pedagogy of Acompañamiento: Mexican migrant youth writing from the underside of modernity. Harvard Educational Review, 81(3), 550–e573.

- Short, D. J., & Boyson, B. A. (2012). Helping newcomer students succeed in secondary schools and beyond. Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Smith, T. M., & Ingersoll, R. M. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover? American Educational Research Journal, 41(3), 681–714. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041003681

- Sorensen, L. C., & Ladd, H. F. (2020). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. AERA Open, 6(1), 233285842090581. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420905812

- Stavely, Z. (2019). california schools help unaccompanied immigrant students combat trauma, language barriers. EdSource.

- Suárez-Orozco, C., Rhodes, J., & Milburn, M. (2009). Unraveling the immigrant paradox: Academic engagement and disengagement among recently arrived immigrant youth. Youth & Society, 41(2), 151–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09333647

- Sunderman, G. L., Kim, J. S., & Orfield, G. (2005). NCLB meets school realities: Lessons from the field. Corwin Press.

- Theoharis, G., & O’Toole, J. (2011). Leading inclusive ELL: Social justice leadership for English language learners. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(4), 646–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11401616

- Thompson, K. (2013). Is separate always unequal? A philosophical examination of ideas of equality in key cases regarding racial and linguistic minorities in education. American Educational Research Journal, 50(6), 1249–1278. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213502519

- Tienken, C. H. (2019). Cracking the code of education reform: Creative compliance and ethical leadership. Corwin.

- Umansky, I., Hopkins, M., Dabach, D. B., Porter, L., Thompson, K., & Pompa, D. (2018). Understanding and supporting the educational needs of recently arrived immigrant English learner students: Lessons for state and local education agencies. Council of Chief State School Officers.

- Villavicencio, A., Jaffe-Walter, R., & Klevan, S. (2021). “You can’t close your door here:” Leveraging teacher collaboration to improve outcomes for immigrant English Learners. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103227

- Wasley, P. A. (1991). Teachers who lead: The rhetoric of reform and the realities of practice. Teachers College Press.

- Weiner, J. M., & Torres, A. C. (2016). Different location or different map? Investigating charter school teachers’ professional identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.006

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems Thinker, 9(5), 2–3.

- Wronowski, M. L., & Urick, A. (2019). Examining the relationship of teacher perception of accountability and assessment policies on teacher turnover during NCLB. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27, 86. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3858

- Wronowski, M., & Urick, A. (2021). Teacher and school predictors of teacher deprofessionalization and demoralization in the United States. Educational Policy, 35(5), 679–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904819843598

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.