Abstract

The scholars in Disability Studies in Education (DSE) have explored critical connections between race, disability, and other markers of identity. This article specifically explores narrative accounts of two first generation Black African immigrant students’ educational navigation and their English as Second Language (ESL) and special education experiences. A pluralistic theoretical approach including Disability Critical Race Studies (DisCrit) and Ethnic Racial Identity (ERI) Formation framework is employed. The author proposes a disability-integrated ERI (D-ERI) framework. Some important findings from participant narratives suggest their awareness of the ESL as a formalized system leading to special education placement, and their acts of resistance against the deficit perceptions about their intersectional ethnic-racial identities in U.S. schools.

Introduction

The growing immigrant student population in U.S. schools is subjected to racist nativism,Footnote1 white supremacy, and cultural hegemony within educational spaces and the larger U.S. and global society (Artiles, Citation2015). The deficit thinking, language, and assumptions (Patton Davis & Museus, Citation2019; Valencia, Citation2010) about immigrants’ multiple identities in the political and social climate calls for re-exploring the educational experiences of recently migrated first generation students experiencing deficit policies and practices. Some of these educational policies include hyper-surveillance of immigrants and refugees within English as Second Language (ESL) and special education classrooms, and the standardized assessments and educational disparities for racially and ethnically marginalized students in schools (Artiles et al., Citation2005; Bal, Citation2009, Citation2014; Ladson-Billings, Citation2006; Migliarini et al., Citation2019).

Scholars have identified a need for research that accounts for the educational experiences of growing immigrant student populations in the U.S. (Artiles, Citation2015; Kiramba & Oloo, Citation2019). First generation students especially students from Africa experience cultural racism, linguicism, and ableism in their host culture and schools (Artiles, Citation2015), a pattern of discriminatory practices that have long defined public education in the U.S. (Ladson-Billings, Citation2006). However, scholars have argued that the diverse cultures, traditions, and linguistic competencies that immigrant students bring to U.S. schools need to be recognized and valued, especially those competencies that are not aligned with White, middle-class norms and culture (Artiles, Citation2011, Citation2013; Kiramba & Oloo, Citation2019).

A growing body of research literature has focused attention on the disproportionate representation of students from multiply marginalized communities in special education (Artiles, Citation2011, Citation2013; Artiles et al., Citation2005; Brayboy et al., Citation2007; Cavendish et al., Citation2018; Cooc & Kiru, Citation2018; Voulgarides et al., Citation2017). However, little is known about the educational experiences of first-generation immigrant students with dis/abilitiesFootnote2 and how they navigate their intersectional identities within schools (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Bal, Citation2009; Migliarini et al., Citation2019). This research paper aims to present the narrative accounts of two first generation Black African male students’ educational experiences in the U.S. K-12 education system. The purpose of this research paper is to explore their meaning making of English as Second Language (ESL) and Special Education experiences, their navigation of intersectional identities in the U.S. education systems, and intersectional identity formation in their new schools in the U.S. Specifically, the following research questions were asked:

How do first generation Black African immigrant students, with dis/abilities, make meaning of English as a Second Language and Special Education experiences?

How do first generation Black African immigrant students, with dis/abilities, experience schooling and navigate their intersectional identities on a daily basis?

Theoretical and conceptual foundations

The following study is grounded in the interdisciplinary and intersectional field of Disability Studies in Education (DSE) (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Connor et al., Citation2008). I specifically incorporated a plurality of theoretical frameworks (Baglieri et al., Citation2011; Connor et al., Citation2011) including Disability Critical Race Studies (Annamma et al., Citation2013) and Dis/ability-Integrated Ethnic-Racial Identity Formation (Umaña-Taylor et al., Citation2014). The scholars within DSE community have argued for an interdisciplinary theoretical and analytic engagement for exploring students’ intersectional experiences and how they adopt and perform strategies and practices in a new culture; i.e., engage in praxis and resist certain deficit ideologies (Artiles, Citation2015; Bal, Citation2009, Citation2014; Bal & Arzubiaga, Citation2014; Giddens, Citation2005; De Certeau, Citation2005).

DisCrit is an interdisciplinary theoretical framework engaging the fields of Disability Studies (DS) and Critical Race Theory (CRT) in which race and disability are socially constructed categoriesFootnote3 in society which are (re)produced by hegemonic power structures working in tandem (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Ladson-Billings, Citation1998). I interpret hegemonic power structures in the U.S. as the dominant White middle-class able-bodied ways of thinking, acting, and speaking that favors white people by allowing them to exercise domination over people of Color. Whiteness as property is “a type of status in which white racial identity provide(s) the basis for allocating societal benefits both private and public … [to white people, while] … continues to serve as a barrier to effective change as the system of racial classification operate[s] to protect entrenched power.” (Harris, Citation1993, p. 1709). DisCrit follows the lineage of DS and CRT to share the lived and educational experiences of people of Color, including first generation immigrants and refugees, and to demonstrate their navigation and resistance to these hegemonic power structures which values whiteness and ability as “normed” reality (Harris, Citation1993; Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011). Within the context of this study, I used the seven tenets of DisCrit to understand how first-generation immigrant students navigated their day-to-day schooling:

DisCrit focuses on ways that the forces of racism and ableism circulate interdependently, often in neutralized and invisible ways, to uphold notions of normalcy.

DisCrit values multidimensional identities and troubles singular notions of identity such as race or dis/ability or class or gender or sexuality and so on.

DisCrit emphasizes the social construction of race and ability and yet recognizes the material and psychological impacts of being labeled as raced or dis/abled, which sets one outside of the Western cultural norms.

DisCrit privileges voices of marginalized populations, traditionally not acknowledged within research.

DisCrit considers legal and historical aspects of dis/ability and race and how both have been used separately and together to deny the rights of some citizens.

DisCrit recognizes Whiteness and Ability as property and that gains for people labeled with dis/abilities have largely been made as the result of interest convergence of White, middle-class citizens.

DisCrit requires activism and supports all forms of resistance.

(Annamma et al., Citation2013, p. 11)

I also employed a Dis/ability-Integrated Ethnic-Racial Identity (D-ERI) framework to understand participants’ sense of self in a new culture. Umaña-Taylor et al. (Citation2014) defined ethnic-racial identity as “a multidimensional, psychological construct that reflects the beliefs and attitudes that individuals have about their ethnic–racial group memberships, as well as the processes by which these beliefs and attitudes develop over time” (p. 23). Within the domain of ethnic-racial identity formation, race and ethnicity are socially constructed and fluid constructs that are embedded in context (Echols et al., Citation2018; Gaither et al., Citation2013; Nishina et al., Citation2010). Taking a disability studies approach, I understand that dis/ability is also a socially constructed identity in the education system and society. From this perspective, I introduce a Dis/ability-Integrated Ethnic Racial Identity formation (D-ERI) framework as a lens to understand the tension and multiplicity of students’ identity formationFootnote4 as they navigate their on-going ethnic, racial, dis/ability and other multidimensional experiences in a dialogic relationship with the cultural artifacts in schools. By cultural artifacts I mean the artifacts and nomenclature produced and promoted in school culture and larger society that categorize and sort students into different identity categories (Artiles et al., Citation2016; Holland et al., Citation1998; McDermott et al., Citation2011; Nasir & Hand, Citation2006), such as standardized tests and exams, models of disability, cultural labels, relationships, schooling practices and activities and different learning placement or locations embedded. I was specifically interested in how students experienced and negotiated these cultural artifacts in schools, while also at times using them to their benefit (De Certeau, Citation2005; Giddens, Citation2005).

Methodology

I used qualitative methods (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007); specifically hermeneutic phenomenology (Cohen, Citation2000; Eatough & Smith, Citation2017; Finlay, Citation2012; Merleau-Ponty, Citation1964), to analyze the data. Hermeneutic phenomenology allows qualitative researchers to engage multiple layers of critical interpretations of participants’ experiences (Finlay Citation2012). I present these layers of interpretation through (a) hermeneutics of empathy and (b) hermeneutics of suspicion (Ricoeur, Citation1974). Ricoeur (Citation1974) explained interpretation as “the work of thought which exists in deciphering the hidden meaning in the apparent meaning, in unfolding the levels of meaning implied in the literal meaning” (p. xiv). While I assumed an empathic stance of what it is like to be the participant, I also engaged with the participants as they reflected on deeper meaning. This engagement allowed for ongoing dialogue that created a space for participants to reflect deeper on their experiences beyond simple description of what is and is not.

Participants selection process

This study is part of a larger study with four participants who were residents of two small Midwestern urban cities, Sugar Valley and Lake View.Footnote5 My understanding of small urban cities is based on Milner’s (Citation2012) categorization of urban emergent cities (fewer than 1 million people) that share many of the same characteristics of the larger urban cities. Both cities are growing from their once white, northern European population into a more ethnically diverse population. Currently, immigrants and refugees from Liberia, Burundi and Congo are the largest growing population after the Burmese and Bosnians. The participants for this study were members of the Liberian community. The larger study (Iqtadar, Citation2022) provided an intersectional analysis of first-generation African immigrant and refugee students’ identity formation in their new schools in the U.S., the meaning making of their Special Education and English as Second Language (ESL) experiences, and navigation of intersectional identities in the education system (Connor et al., Citation2011; Holland et al., Citation1998). I used a purposive and convenience sampling technique (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007; Creswell, Citation2013; Glesne, Citation2016; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, Citation2007) to directly recruit participants in the local community. A local church supported participant recruitment.

This article presents the narratives of two participants’ schooling experiences in the ESL and special education classes in public schools. At the time of this study, Kabaka was an eight-grade student who had migrated to the U.S. with his family six years prior to the beginning of this study. Mandla, who also received ESL and special education services, was a high school senior starting his first job at a local community sport facility. Mandla’s family recently moved to the U.S. two years prior. Both Mandla and Kabaka’s families came to the U.S. from Liberia through the lottery system and lived in the same apartment complex.

As a first-generation immigrant myself, there were many challenges that I encountered during the data collection phase. I did not really know any African families in the community to begin with. The initial contact made was with the school district and the local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working with the school district to recruit participants. Despite the successful initial meetings with the district administration, I was unable to secure permission to conduct this research. Some challenges were related to the deficit belief and assumptions about immigrants and refugees (Patton Davis & Museus, Citation2019; Valencia, Citation2010) and the school district’s reliance on the “vulnerability” status of the students according to federal regulations regarding research with human subjects. I strongly believe that student voice (Gonzalez et al., Citation2017) should be centered to understand their systemic experiences in the education system. The challenges encountered with local NGOs were related to minimum access to participants (one interview with each participant) in the presence of one member of the NGO. I finally edited the research protocol and sought participation through community resources. The study was approved from the Author’s institutional review board.

Researcher positionality

My interest in the educational experiences of first-generation immigrant students stemmed from my experiences as a Muslim, South Asian multilingual female immigrant to the U.S. I acknowledge that while I have experienced countless moments of implicit and explicit racism, the ability supremacy of English language, and xenophobic remarks within higher education, my participants’ experiences are unique within K-12 education system. Additionally, I am mindful of the power dynamics and privilege inherent within my research (Armour et al., Citation2009). I acknowledge that while I self-identify as a person of Color in the U.S. because of my day-to-day experiences, my “lighter skin tone” and researcher status renders me a privileged position in educational and social situations (Dumas, Citation2016). This is critical because my participants are first-generation Black African students with unique intersectional experiences and while I have interacted with African international students on campus, I don’t really know any Black people. Understanding that the institutional stratification—implicit and/or explicit—based on one’s skin tone and the bias for one’s skin pigmentation is an endemic problem in education and society (Crutchfield et al., Citation2021), I documented researcher journal entries and shared personal experiences with my participants to understand their unique experiences in the system.

Data collection procedures

The data collection procedures for the study involved 3 in-depth interviews with Kabaka and Mandla each, reviewing their Individualized Education Plan (IEP) documents, and collecting expansive field notes of the interview interactions (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation1982; Foster, Citation2009). Each interview lasted between one and a half to two hours. The semi-structured interview protocol permitted further probing for rich and thick data of their experiences and to “co-construct” the dialogue with participants (Creswell, Citation2013). Expanded questions and reflections were used to unpack participants’ stories. Throughout the data collection and data analysis phase, I maintained confirmation checks and reflective journal entries to ensure trustworthiness and credibility (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007; Creswell, Citation1998).

All interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, and were audio recorded and transcribed before the next interview. Parental consent was sought to interview Mandla and Kabaka as per the requirement of the Author’s institutional review board. Additionally, both Kabaka and Mandla’s parents were invited and sat through the interviews as the interviews were conducted. I read through each transcription, highlighted the missing information, and wrote clarifying questions in addition to the questions that originated from the previous interview. Embedded in hermeneutics and narrative approaches, presents an example of the data collection procedures (Eatough & Smith, Citation2017). The first column represents the planned interview question with the follow-up question and/or comment that expanded the dialogue. Third column illustrates an example of member checking questions to develop rigor and trustworthiness, while the last column represents excerpts from my reflective journaling as appeared in my field notes in relation to the specific dialogue.

Table 1. Data collection procedures.

Data analysis procedures

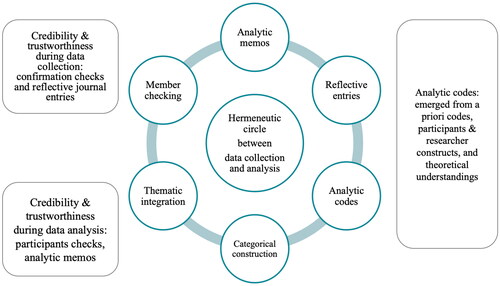

Data analysis began simultaneously with the data collection procedures (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007) (see ). My in-field analysis included immersing myself into transcripts with iterative reading of the transcripts, reflective journal and field-notes entries, and emerging thoughts as documented in the form of analytical memos (Ajjawi & Higgs, Citation2007). I revisited the data after every interview to identify the emerging questions and point of discussions for the next meeting. At the beginning of the next interview, I revisited these points with the participants for additional questions by moving between this emerging data, their narratives, and my reading of the literature (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007; Eatough & Smith, Citation2017).

Following the tradition of hermeneutics phenomenology, my initial codes emerged from this interactive process of in-field analysis, including an interpretation based on the a priori codes emerged from the qualitative research synthesis (QRS) that I conducted in 2020, the theoretical and conceptual frameworks, and the empirical literature I was immersed in and my personal positionality—which I termed researcher constructs (Suddick et al., Citation2020; ). The analytic codes () represent the hermeneutic circle of this immersion into the transcript data, theoretical and empirical literature, and the participant and researcher constructs (Suddick et al., Citation2020). From an analysis of the initial coding, categorical construction was developed based on concepts from DisCrit and D-ERI models (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Umaña-Taylor et al., Citation2014). A constant-comparative analysis across the constructed categories was used to develop themes and to establish the credibility and trustworthiness of the analysis.

Table 2. Hermeneutic circle process for data analysis.

I also approached this research with the underlying assumption that bracketing, or reduction is impossible (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1964). Thus, I recognize that their stories are first mediated through their own recollection and second through my sharing of them (Gallagher, Citation1995). I maintained “researcher constructs” within the reflective journal to unpack my own assumptions and biases while documenting participant’s experiences (Suddick et al., Citation2020). I shared those reflections with Mandla and Kabaka to expand my ongoing analysis. The result is a careful retelling of two recent African immigrant male students’ stories in U.S. school and society.

Mandla’s story

Resettlement narrative: Cultural, racial, and linguistic navigation

Mandla had just turned 18 when I interviewed him in the Spring of 2021. He migrated to the U.S. from Liberia three years prior to conducting this study and lived with his father and older brother, Elijah, in an apartment complex. Since their arrival Mandla’s family moved three times and finally resettled in the current neighborhood with predominantly immigrant and refugee families from Africa. When I first visited Mandla I was greeted by his brother at the door as Mandla got ready for work. I casually probed about his work and Mandla shared that he had been working in the local community sport facility for almost six months and has recently been promoted for a permanent position. I could sense his excitement for the new job. He was excited for the independence that came with job security but most importantly he was happy to be contributing financially to his family.

Mandla’s father spoke Mano (a language widely spoken in Liberia) as his first language. However, Mandla struggled with speaking the language and preferred “Liberian English” as a source of communication. His racial and ethnic identities are important to him, and he understood his cultural navigation in a contrasting manner between the Liberian and U.S. society and education system. He self-identified as an African and was proud of his “African background.” This is important as Mandla’s schooling experiences included cultural and linguistic racism that he endured in school spaces.

Mandla understood his cultural and racial self in contrast to his understanding of U.S. culture. He often saw his Liberian culture in contrast with the U.S. education system, life struggles and opportunities, basic differences in Liberian and U.S. English, and work opportunities between the two countries. One important aspect of his cultural navigation was economic stability, and he discussed the financial differences and its impact on life opportunities of people in the two cultures.

You know [in Liberia] you got to wake up in the morning… you gotta walk to school… because down there it is all about walking… you don’t have much money, so you have to walk to school… and then come back home and go to work… while here [in the U.S.]… you have everything here… you don’t walk to school… I mean some people will walk to school… but not all.

Moving to the U.S. and recently getting the work at local sport facility Mandla, like many recent immigrants to the U.S., was drawing comparisons between his family’s financial conditions in Liberia and the U.S. In our conversations, Mandla spoke fondly of his financial goals to support his family.

Educational journey: English as second language (ESL) leading to special education placement

Mandla valued learning, however he consistently questioned the need for English as Second Language (ESL) and special education placement for newcomer students (DisCrit, Tenet 4). Elaborating on his ESL placement, Mandla said that placement in a separate classroom should not be about “learning to speak English,” as one can “learn language better with general education peers.” Throughout his schooling Mandla was placed in an ESL classroom. He felt that his English was better and that he should have been moved to the general education classes. Despite his disapproval Mandla was placed in ESL and special education classes until the very end of his high school education. This resulted in Mandla skipping classes to show resistance to placement decisions (DisCrit, Tenet 7). In our conversations, he consistently discussed being “controlled” by the education system and questioned how that placement decision was made for him without giving him a choice. He questioned who created the rules for the segregated education system for students:

but I don’t know, I feel like I don’t have a choice. Like who created these rules? Who’s doing all of this? I don’t know. You know saying I don’t have a choice, my brother told me he said the school is controlling you. They don’t want you to be doing something by yourself. So you know that’s a question I want to ask somebody. I don’t know but I want to ask, and I don’t have a choice. They tell me I don’t have a choice. And I am like what? Why don’t I have a choice?

Mandla experienced the similar difference-deficit-dis/ability “web.” One of the continued topics of discussion was his placement in the special education classroom. He felt compelled to speak like his American peers and discussed being marginalized and segregated within the special education classroom for his Liberian accent and reading and writing skills. Mandla stated that his needs were only related to reading and writing. However, he was made to spend most of his day in the special education classroom. He said “they had me in a special class for me to learn how to read and write. I just spent the whole time there for the rest of the day.” When I reviewed Mandla’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) document, I learned that Mandla’s IEP goals were related to reading, writing, and Math. Specifically the reading goals stated:

Reading: Mandla is an Emergent reader. Mandla identifies/states the name of all letters in the alphabet. He states the most sound of all letters. He reads almost all 100 sight words on list 1. The focus for Mandla this year is to read and comprehend words from applications and forms. When provided with 50 survival/work/personal information related words, Mandla read 28 of those words independently.

The abovementioned excerpt from Mandla’s IEP indicates that he was placed in the special education classroom because he was an “emergent reader” which is troubling for the above-mentioned reason of academic language acquisition of bilingual and/or multilingual students. From DisCrit perspective, it represents how legal structures and programs (i.e., ESL to special education pipeline in this case) are often used “separately and together to deny the rights of some citizens”; thus restricting Mandla’s general education placement and socialization with general education peers (Tenet 5, p. 11). During my conversations with Mandla, his discontent with the special education placement was rooted in his understanding that the academic support he needed for reading, writing, and Math should be provided in the general education setting. However, reading his IEP goals made me realize how often students from ethnic, racial, and linguistic diversity are represented within special education classrooms; meaning their movement and placement in ESL and special education classrooms is more fluid and is often a result of subjective “deficit” assumptions about immigrant and refugee students (DisCrit, Tenet 1) (Artiles, Citation2003; Artiles et al., Citation2010).

In other words, this difference-to-deficit-to-disability “web” (Brown, Citation2004; Gonzalez, Citation2001) fails to account for cultural or linguistic diversity prior to referral for special education “assessment” and eligibility for services (DisCrit, Tenet 1 & 6). The challenge to distinguish the need for special education services from “English language proficiency” (Klingner et al., Citation2014; Park, Citation2019; Guiberson & Atkins, Citation2012; Shenoy, Citation2014) contributes to the overidentification of bilingual and/or multilingual students into special education placements; social construction of race and dis/ability (DisCrit, Tenet 3) (DeMatthews et al., Citation2014; Sanatullova-Allison & Robison-Young, Citation2016). While the label “emergent bilingual” is intended to replace deficit framing labels such as “limited English proficient (LEP)” (Przymus & Alvarado, Citation2019), I realized that the description in Mandla’s IEP confirms the different-to-deficit-to-disability web, particularly given the timeline of his special education “eligibility” determination.

Resisting hegemony

Mandla consistently shared his lack of willingness to sit in the special education classes. The following quote represents his active resistance to the special education placement decision (DisCrit, Tenet 7).

I don’t like going to school because of the class [special ed. class] I’m in. I will miss my class … They all keep asking why you are missing class, because I don’t want to be in that class. That’s why I would be skipping the class … I get “mad” and I don’t want to sit there, and so I skip class … I tell them but they don’t listen.

Mandla’s decision was rooted in the embarrassment he felt when asked about special education classes by peers, and his discontent with the placement decision.

Additionally, he found it problematic to learn to speak the American accent. In one of our conversations, he shared that most of his friends were immigrant students from other countries because they were more accepting of the accent differences as compared to his American peers. He shared: “and yeah I would be more friends with them…You know Asian, Puerto Rican… yeah… so I have more friends from different countries … we don’t have issues with accent you know …” This did not mean that Mandla disapproved of school and education in general. He found ways to “fit in” the different components of the education system and society, such as the work experience class, engaging in sports activities, and finding a job as early as possible:

I’m also in work experience. I’m in this class where you learn about work experience. It’s like learning how to work … So in work experience they are teaching me how to work. It teaches me when I go somewhere, you know how I can write applications and do something for myself

Kabaka’s story

Kabaka’s education journey in the U.S. began as a fifth grader in 2016. When I interviewed Kabaka in 2021, he was an eighth-grade student receiving ESL and special education services. Like Mandla, Kabaka migrated to the Midwest from Liberia with his parents and younger sister. The immigration process presented many economic, cultural, and racial challenges for the family. In our initial conversations Kabaka shared “like comparing the U.S. with Liberia just to get here [U.S.] is hard. You have to spend a lot of money, go through a lot of processes.” Despite these economic difficulties, his family was hopeful for better life opportunities in the U.S.

Linguistic navigation leading to dis/ability “identification”

Kabaka speaks his mother tongue, Bassa, but his first language is Liberian English. Like Mandla, the linguistic difference presented many challenges for Kabaka in school. One of the difficulties in school was that the teachers could not understand Kabaka well enough during reading or speaking in class. Kabaka was also sent to the ESL and then to the special education classroom for linguistic “difference” and his “accent”; interdependence of race and special education categorization (DisCrit, Tenet 1 & Tenet 3). He repeated fifth grade and started receiving special education services in the second year of him attending the school. Kabaka recalled that his placement in the special classroom was rather abrupt and at the time he and his dad were not aware about what was going on. Do you remember the first individualized education program (IEP) meeting and how did it go, I asked? Kabaka shared:

I mean we went together and so the teacher was telling the Pastor and my dad how I was doing and she said I was doing good in this class, and she said that I might need help in the other class. Then after that she said my reading level is like a 4th grader level. I mean, I was not pretty sure about that. I didn’t really believe that. I would say my reading was getting better.

Thinking now I don’t think they really explained it. I mean they just told me that and to the teacher. They just introduced me to the teacher and said that you will work with this teacher for a year. I said okay …

Kabaka shared that the services had helped him “go slow;

The thing that really holds me back when I am reading, most of the words I am going to know but then I am like a “slow” reader. I have to think about what the word says before I read it. I can’t think about it and just start to read it at the same time.

He hoped for extra support from his teachers in the general education classroom. However, like Mandla and many other immigrant students, Kabaka’s path was already established to the ESL leading to the special education trajectory.

Navigating “smartness” as “whiteness”

During our initial conversations it appeared that Kabaka wanted to “assimilate” to “fit into” the system: “we go out… we are all cool, play basketball together. Like basketball team I’m the fastest. I have many friends. We are all friends in school.” Over time the statements such as “we are all friends in school” changed to the stories of resistance where he discussed feeling “different” in class. The racial and cultural “territories” in his class were so visible that Kabaka did not feel welcome to sit in specific areas of the class, specifically with his White peers. Annamma and Morrison (Citation2018) identified these classroom racial territories as a result of “dysfunctional educational ecologies” where interactions are based on power imbalance among students of Color and their white counterparts. Kabaka’s dissatisfaction with the education system was rooted in feeling systemically discriminated against through the formalized education system as well as experiencing racial-cultural discrimination and ability supremacy by peers and teachers alike. He discussed feeling that all his White U.S. born peers were “smarter” than him. Why would you feel different, I asked for clarification? “Because they expect you to be “smart” so for some reason everybody expected me to be like them [White students]” (DisCrit, Tenet 3, 4 & 6). At this point, I realized that what Kabaka experienced was a common thread that many first-generation immigrant students, and many Black, Brown and Indigenous Youth of Color (B*IYOC) experience in U.S. schools (Barillas-Chón, Citation2010; Braye, Citation2018; Iqtadar et al., Citation2020). The concept of whiteness was used as a “tool for stratification” and classify him as “other” based on racial and ability supremacy (Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011, p. 2212). He was made to feel that the “different” him was not “smart enough” and needed to assimilate through a formalized system of ESL and special education to be as “smart” as his White peers.

As a first-generation immigrant graduate student at the time myself, I understood the feeling that Kabaka had experienced in those moments. It was as if we both were reliving the moments where we experienced similar discomfort of being looked down upon in education spaces. Do you think that is true, I asked? Lowering his voice, Kabaka responded in one word: “No.” What made you say that, I probed? To this he shared that his white peers appeared to be “smarter” in academics because they received elementary education in the U.S. and already know the system: “coz they were born here… They went to the elementary schools or kindergarten here… I came here in 5th grade so yeah just got from Africa. I came to the Midwest.” Kabaka’s resistance to the deficit understanding about his multiple identities was rooted in his agency to counter these deficit narratives and his refusal to be seen as someone who needs “fixation” by the system.

Resisting hegemony

Kabaka demonstrated both explicit and implicit acts of resistance to the bullying, cultural and linguistic racism, and ableism he experienced. In one of our conversations, he shared that the physical and verbal resistance often led to detentions without much nuanced understanding of the racism, ableism and linguicism he experienced in classrooms. During one of the classroom incidents, Kabaka recalled:

Cuz those kids … they are calling me something … and then I get pretty mad… and then I fight them and then the teacher came in and told me to go to office … then I tell them [the counselor] that they’re making fun of my language and my race and calling me gorillas and stuff then she just told me why don’t you just move seats …

Additionally, he resisted the deficit ideas about his multiple identities. Like Mandla he did not see special education and dis/ability as an identity that represented him; social construction of dis/ability based on language difference (DisCrit, Tenet 3). Kabaka constantly resisted the idea that he does not deserve quality education. He understood that he had certain needs, and his education should be individualized within the general education setting. To him, he deserved quality education with his general education peers, and that education should be differentiated for his needs.

Discussion

This paper presents the narratives of two first generation male African students in K-12 education who experienced cultural racism, ableism, and linguicism as intertwined in the U.S. education system and society (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Iqtadar et al., Citation2021). Given that this study involved only two participants, the aim was not to theorize on a larger scale. Instead, Mandla and Kabaka’s narratives provide first-hand stories of experiencing racism and ableism as first generation African male immigrant students. Scholars such as Annamma (Citation2013), Artiles (Citation2015), Bal (Citation2009), Migliarini et al. (Citation2019) and others have argued that first generation immigrants and refugees endure intersectional disablism on a regular basis (Iqtadar et al, Citation2020). Assuming that these first-generation students differ in their ways of thinking, learning and abilities from their white peers (Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011; Valencia, Citation2010), the difference is indexed in cultural “others” and needing to be “fixed” (Annamma et al., Citation2013); thus continuing to perpetuate “whiteness as valued social identity” in educational spaces (Harris, Citation1993, p. 1758). Such as in both Mandla and Kabaka’s case their ESL to special education placement dictate how education system and programs (such as ESL to special education trajectory) are programmatically and ideologically used to deny Black bilingual first generation students of Color their right to receive quality general education (DisCrit, Tenet 5). The root cause of this denial is the belief in the superiority of whiteness, english language and ability supremacy where these three are considered the “normed” and accepted reality of U.S. public schools (Bonilla-Silva, Citation2006).

Embedded in DisCrit and D-ERI (Annamma et al., Citation2013; Iqtadar, Citation2022), the difference-to-deficit-to-disability “web” was confirmed when Mandla discussed that his racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse self was viewed from a deficit approach, and that those deficits were mechanically viewed as dis/abilities (Artiles, Citation2003; Connor, Citation2019). This is highly problematic and needs immediate attention of educational scholars engaged in the identity formation of first generation immigrant and refugee students. Recognizing how well-intentioned programs such as ESL and special education may serve as a proxy for ethnic-racial segregation and enforce cultural artifacts embedded in whiteness, linguistic and ability supremacy (Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011). Adding to existing ethnic racial identity formation framework (ERI), participants’ narratives provide classic cases of dis/ability as a socially created category in the education system for these first-generation immigrant students; hence disability-integrated ethnic-racial identity formation (D-ERI). Specifically, Scholars in Disability Studies in Education (DSE) argue that within the school spaces ESL leading to special education placement practices are used as ability tools and as a pipeline to segregate multilingual and multicultural students and to maintain and preserve hegemonic systems of able-bodiedness, ability supremacy and ability-centric narratives (Waitoller & Artiles, Citation2013).

Annamma et al. (Citation2013) conceptualize race and dis/ability as socially enforced identities in schools and society.

DisCrit focuses on the interdependent ways that racism and ableism shape notions of normalcy. These mutually constitutive processes are enacted through normalizing practices such as labeling a student “at-risk” for simply being a person of color, thereby reinforcing the unmarked norms of Whiteness, and signaling to many that the student is not capable in body and mind (p. 35).

Mandla and Kabaka’s experiences dictate that ESL practices are a formalized system intended to create a pathway to (a) linguistic assimilation, (b) preserve cultural hegemony of the White Middle class norms, language and accent, and (c) maintain structural segregation of their racial, cultural and ethnic selves in U.S. schools (Harris, Citation1993; Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011). They were supposed to “catch up” with their English-speaking peers and “catch on” using “correct” or American English. For both participants, this formalized placement led to special education placement within their first two years in U.S. schools.

My participants also discussed feeling discriminated against and consistently resisted the deficit perceptions that led to assigned racist and ableist labels (DisCrit, Tenet 7). They resisted for not being able to receive quality education and being considered equal partners in their education (Annamma et al., Citation2013). This resistance was also depicted in their interactions with peers when bullied and with educators when misunderstood for their racial and ethnic selves. They also employed acts of resistance for “forced assimilation” in ESL and special education classrooms and demonstrated “physical and verbal resistance” by skipping the school and by speaking up for themselves and their friends against the racialized territories in the classroom, such as in the case of Kabaka. These acts of resistance had an impact on participants’ emerging sense of self, their agency and identity formation and educational outcomes in new school settings.

Participants also recognized whiteness and ability as property (DisCrit, Tenet 6) valued in schools and that the relationship between educational practices, cultural artifacts, as well as activities conducted in schools that marginalize and “sort” students confer a depth to figure landscape that extends beyond the figured world of schooling and the interactions at personal and interpersonal levels (Annamma et al., Citation2018; Giddens, Citation2005). From the intersectional perspective of structural and political levels, they discussed how the education system privileges White middle-class cultural ways of being and questioned the role of education in maintaining these racial, cultural, ability, and linguistic hierarchies (Crenshaw, Citation1991; Leonardo & Broderick, Citation2011). For example, Mandla questioned the existence and maintenance of special education and ESL classrooms by asking who creates these rules to segregate students.

While they mostly resisted the hegemony of ability-centric placements and identity grouping, their agency was also represented in their “use” and “consumption of” specific strategies and cultural artifacts for making informed and liberatory decisions in school and social life (De Certeau, Citation2005; Umaña-Taylor et al., Citation2014). According to Holland and Cole (Citation1995) cultural artifacts have both ideal and material realities. They are living artifacts which coordinate joint activities and are used to assign the subjects certain positions, roles and tasks. Within the figurative world of schools, Mandla specifically employed strategies for future benefits. For example, despite him disliking the school, he continually attended work experience class and used it to find a job so that he could financially support his family.

In current education practice the cultural artifacts are framed to extend existing racist and ableist practices and policies in ways which seem to “empower” newcomer students. However, Mandla and Kabaka’s narratives depict that these artifacts, such as placement in ESL and special education classrooms, may further limit access to quality education for first generation students (DisCrit, Tenet 3). Future work with immigrant students should complicate D-ERI lens with DisCrit to understand intersectional identity formation and focus analytic attention at personal, interpersonal, structural and political levels of society (Crenshaw, Citation1991). Centering the voices of those marginalized in intricate ways in the new system would engage the issue of salience to analyses of the ways in which an ever-emerging identity engages with the systems of power. This would have implications to understanding the impact of variables such as economic, cultural, social and emotional difficulties in the life of first-generation immigrants with and without dis/abilities.

Implications

Even though this study involved only two participants, Kabaka and Mandla’s narratives provide valuable insights for teachers, both pre-service and in-service, and other professionals working with students with multilingual and multicultural backgrounds. The findings suggest that educators working with diverse student population be more sensitive to the World Englishes in their day-to-day teaching and curriculum, and to avoid linguistic racism that may blind individual’s English dialect and linguistic variation and lead to biased special education referrals.

One way to support such an inclusive environment is by incorporating a Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy (CSP) along with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (CAST, Citation2018; Paris & Alim, Citation2014). Educators engage CSP with an aim to sustain, value, and use students’ linguistic, literate and cultural practices as assets in the classroom (Ladson-Billings, Citation2014; McCarty & Lee, Citation2014; Paris, Citation2012; Paris & Alim, Citation2014). Coupled with UDL, which seeks to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all students while eliminating the systematic and educational barriers (CAST, Citation2018), a pedagogy that is responsive to the needs of diverse student populations emerges.

The proposed blending of CSP with UDL can further provide an important tool to educators to engage activism in schools and counter the deepening inequities against diverse student populations, such as to counter the ESL to special education pipeline, and the difference-deficit-dis/ability “web” (Annamma & Morrison, Citation2018; Artiles, Citation2015; Artiles & Dyson, Citation2005; Suárez-Orozco, Citation2001; Waitoller & King Thorius, Citation2016). Specifically, this hybrid pedagogy will provide teachers with tools, resources, techniques, and strategies which defy the existing racist and ableist assumptions against monolingual and/or bilingual students of Color with and without dis/abilities.

Finally, the study also asks for a re-exploration of the current U.S. education policy which is structured through the statues of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Every Student Succeed Act (ESSA). Scholars have identified that the current education policy fails to consider students’ intersectional identities, and privileges singular notions of identity, such as race or dis/ability or social class (Annamma et al., Citation2013; McCall & Skrtic, Citation2009). Additionally, current education policy facilitates a deficit-based assimilationist model of education (Artiles et al., Citation2016; Erevelles et al., Citation2006), which requires students of Color with and without dis/abilities to assimilate into a hegemonic “normed” “White middle-class” education structure (Artiles et al., Citation2011; Connor, Citation2019). Specifically, IDEA’s categorization of dis/ability labels is based on the deficit medical model of dis/ability which places individuals with dis/abilities at the margins of society by identifying a “problem” within the child (Patton Davis & Museus, Citation2019). Kabaka and Mandla’s narratives suggest that rather than focusing on the deficit model approach and “remediating” children, special education law must recognize intersectionality to contextualize and visualize students’ rich and diverse backgrounds (Crenshaw, Citation2015). Rather than anchoring educational policy with an assimilation framework which constrains student agency, educational law must shift toward cultural inclusion.

Disclosure statement

The author reports there are no competing conflicts of interests to declare.

Notes

1 “the assigning of values to real or imagined differences, in order to justify the superiority of the native, who is to be perceived white, over that of the non-native, who is perceived to be People and Immigrants of Color, and thereby defend the right of whites, or the natives, to dominance” (Huber et al., Citation2008, p. 43).

2 I understand that both disability and ability are historically and politically constructed categories in society. My use of slash is to disrupt this social construction which exerts control on the life of people with dis/abilities through this binary construction; including national and international laws and policies (Iqtadar et al., Citation2021; Ribet, Citation2011). I further acknowledge that the term is often used in the academy and may not be supported by people with disabilities. They would rather “say the word” for identity and disability pride. For this purpose, I also use the term “disability” or “disabilities” throughout, whenever appropriate.

3 Disability Studies (DS) and Critical Race Theory (CRT) vary in their explanation of disability as a social vs. medical or biological identity. While scholars in DS understand disability as a social and political identity, CRT scholarship conceives disability as a biological category (Erevelles & Minear, Citation2010). Similarly, scholarship in DS for a long time, painted the field as what Bell (Citation2006) termed a white disability studies. Annamma et al. (Citation2013) developed a framework of DisCrit to both address race and racism within the field of DS, and highlight CRT scholars’ failure to focus disability and ableism within their framework.

4 From a sociocultural perspective, identity formation is an individual’s complex and emerging sense of self, mediated by the social, cultural, and historical processes, and is continually produced in and by the dialectical social relationship and interaction with the world (Holland et al., Citation1998).

5 all names of people and places are pseudonyms in accordance with institutional review board approval.

References

- Ajjawi, R., & Higgs, J. (2007). Using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate how experienced practitioners learn to communicate clinical reasoning. Qualitative Report, 12(4), 612–638.

- Annamma, S. (2013). Undocumented and under surveillance. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal, 7(3), 32–41.

- Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

- Annamma, S. A., Ferri, B. A., & Connor, D. J. (2018). Disability critical race theory: Exploring the intersectional lineage, emergence, and potential futures of DisCrit in education. Review of Research in Education, 42(1), 46–71. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18759041

- Annamma, S. A., & Morrison, D. (2018). DisCrit classroom ecology: Using praxis to dismantle dysfunctional education ecologies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.008

- Armour, M., Rivaux, S. L., & Bell, H. (2009). Using context to build rigor: Application to two hermeneutic phenomenological studies. Qualitative Social Work, 8(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325008100424

- Artiles, A. J. (2003). Special education’s changing identity: Paradoxes and dilemmas in views of culture and space. Harvard Educational Review, 73(2), 164–202. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.73.2.j78t573x377j7106

- Artiles, A. J. (2011). Toward an interdisciplinary understanding of educational equity and difference: The case of the racialization of ability. Educational Researcher, 40(9), 431–445. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11429391

- Artiles, A. J. (2013). Untangling the racialization of disabilities: An intersectionality critique across disability models. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 10(2), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000271

- Artiles, A. J. (2015). Beyond responsiveness to identity badges: Future research on culture in disability and implications for response to intervention. Educational Review, 67(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2014.934322

- Artiles, A. J., Dorn, S., & Bal, A. (2016). Objects of protection, enduring nodes of difference: Disability intersections with “other” differences, 1916 to 2016. Review of Research in Education, 40(1), 777–820. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X16680606

- Artiles, A. J., & Dyson, A. (2005). Inclusive education in the globalization age: The promise of comparative cultural historical analysis. In D. Mitchell (Ed.), Contextualizing inclusive education (pp. 37–62). Routledge.

- Artiles, A. J., Klingner, J., Sullivan, A. L., & Fierros, E. (2010). Shifting landscapes of professional practices: ELL special education placement in English-only states: English learners and restrictive language policies. In Forbidden language: English learners and restrictive language policies (pp. 102–117). UCLA Civil Rights Project.

- Artiles, A. J., Kozleski, E. B., & Gonzalez, T. (2011). Beyond the allure of inclusive education in the United States: Facing power, pursuing a cultural-historical agenda. Revista Teias, 12(24), 285–308.

- Artiles, A. J., Rueda, R., Salazar, J., & Higareda, I. (2005). Within-group diversity in minority disproportionate representation: English language learners in urban school districts. Exceptional Children, 71(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100305

- Baglieri, S., Valle, J. W., Connor, D. J., & Gallagher, D. J. (2011). Disability studies in education: The need for a plurality of perspectives on disability. Remedial and Special Education, 32(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510362200

- Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Multilingual matters.

- Bal, A. (2009). Becoming learners in US schools: A sociocultural study of refugee students’ evolving identities. Arizona State University.

- Bal, A. (2014). Becoming in/competent learners in the United States: Refugee students’ academic identities in the figured world of difference. International Multilingual Research Journal, 8(4), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2014.952056

- Bal, A., & Arzubiaga, A. E. (2014). Ahıska refugee families’ configuration of resettlement and academic success in US schools. Urban Education, 49(6), 635–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085913481363

- Barillas-Chón, D. W. (2010). Oaxaqueño/a students’(un) welcoming high school experiences. Journal of Latinos and Education, 9(4), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2010.491043

- Bell, C. (2006). Introducing white disability studies: A modest proposal. In L. Davis (Ed.), The disability studies reader., 275–282. Psychology Press.

- Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1982). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. Allyn and Bacon.

- Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. (5th Edition). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., Castagno, A. E., & Maughan, E. (2007). Chapter 6 equality and justice for all? Examining race in education scholarship. Review of Research in Education, 31(1), 159–194. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07300046159

- Braye, T. (2018). [Overcoming barriers: Factors of resiliency in refugee students pursuing higher education]. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Abilene Christian University].

- Brown, C. L. (2004). Reducing the over-referral of culturally and linguistically diverse students (CLD) for language disabilities. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 2(1), 225–243.

- Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). (2018). The UDL Guidelines. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

- Cavendish, W., Connor, D., Gonzalez, T., Jean-Pierre, P., & Card, K. (2018). Troubling “the problem” of racial overrepresentation in special education: A commentary and call to rethink research. Educational Review, 72(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1550055

- Cohen, M. Z. (2000). Introduction. In M. Z. Cohen, D. L. Kahn, R. H. Steeves (Eds.), Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Sage.

- Connor, D. J. (2019). Why is special education so afraid of disability studies? Analyzing attacks of disdain and distortion from leaders in the field. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 34(1), 10–23.

- Connor, D. J., Gabel, S., Gallagher, D., & Morton, M. (2008). Disability studies and inclusive education—Implications for theory, research, and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5–6), 441–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377482

- Connor, D. J., Gallagher, D., & Ferri, B. A. (2011). Broadening our horizons: Toward a plurality of methodologies in learning disability research. Learning Disability Quarterly, 34(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/073194871103400201

- Cooc, N., & Kiru, E. W. (2018). Disproportionality in special education: A synthesis of international research and trends. The Journal of Special Education, 52(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918772300

- Crenshaw, K. (2015). Why intersectionality can’t wait. The Washington Post, 24(09), 2015.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Crutchfield, J., Sparks, D., Williams, M., & Findley, E. (2021). In my feelings: Exploring implicit skin tone bias among preservice teachers. College Teaching, 70(4), 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1979456

- Cummins, J. (1981). Empirical and theoretical underpinnings of bilingual education. Journal of Education, 163(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748116300104

- De Certeau, M. (2005). The practice of everyday life: “Making do”: Uses and tactics. In G. M. Spiegel (Ed.), Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn (pp. 213–223). Psychology Press.

- DeMatthews, D., Nelson, T., & Edwards, D. (2014). Identification problems: U.S. special education eligibility for English Language Learners. International Journal of Educational Research, 68, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.08.002

- Dumas, M. J. (2016). Against the dark: Antiblackness in education policy and discourse. Theory into Practice, 55(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852

- Eatough, V., & Smith, J. A. (2017). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: C. Willig & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative psychology (2nd ed., pp. 193–211). Sage. ISBN 9781473925212.

- Echols, L., Ivanich, J., & Graham, S. (2018). Multiracial in middle school: The influence of classmates and friends on changes in racial self identification. Child Development, 89(6), 2070–2080. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13000

- Erevelles, N., Kanga, A., & Middleton, R. (2006). How does it feel to be a problem? Race, disability, and exclusion in educational policy. In E. Brantlinger (Ed.), Who benefits from special education? Remediating [fixing] other people’s children (pp. 77–99). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Erevelles, N., & Minear, A. (2010). Unspeakable offenses: Untangling race and disability in discourses of intersectionality. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 4(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2010.11

- Finlay, L. (2012). Debating phenomenological methods. In Hermeneutic phenomenology in education (pp. 17–37). Sense Publishers.

- Foster, J. (2009). Insider research with family members who have a member living with rare cancer. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(4), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800404

- Gaither, S. E., Sommers, S. R., & Ambady, N. (2013). When the half affects the whole: Priming identity for biracial individuals in social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 368–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.12.012

- Gallagher, D. J. (1995). In search of the rightful role of method: Reflections on conducting a qualitative dissertation. In T. Tiller, A. Sparkes, S. Karhus, & F. Dowling Naess (Eds.), The qualitative challenge: Reflections on educational research (pp. 17–35). Casper Forlong.

- Giddens, A. (2005). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration: Elements of the theory of structuration. In G. M. Spiegel (Ed.), Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn (pp. 135–156). Psychology Press.

- Glesne, C. (2016). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Pearson.

- Gonzalez, T. E., Hernandez-Saca, D. I., & Artiles, A. J. (2017). In search of voice: Theory and methods in K-12 student voice research in the US, 1990–2010. Educational Review, 69(4), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1231661

- Gonzalez, V. (2001). The role of socioeconomic and sociocultural factors in language minority children’s development: An ecological research view. Bilingual Research Journal, 25(1-2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2001.10162782

- Guiberson, M., & Atkins, J. (2012). Speech-language pathologists’ preparation, practices, and perspectives on serving culturally and linguistically diverse children. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 33(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740110384132

- Harris, C. I. (1993). Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review, 106(8), 1707–1791. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787

- Holland, D., & Cole, M. (1995). Between discourse and schema: Reformulating a cultural- historical approach to culture and mind. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 26(4), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1995.26.4.05x1065y

- Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Jr., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Huber, L. P., Lopez, C. B., Malagon, M. C., Velez, V., & Solorzano, D. G. (2008). Getting beyond the ‘symptom,’ acknowledging the ‘disease’: Theorizing racist nativism. Contemporary Justice Review, 11(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580701850397

- Iqtadar, S. (2022). [Educational experiences of first generation Black African students with and without dis/abilities]. [Dissertations and Theses] University of Northern Iowa. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/1236

- Iqtadar, S., Hern, D. I., & Ellison, S. (2020). “If it wasn’t my race, it was other things like being a woman, or my disability”: A qualitative research synthesis of disability research. Disability Studies Quarterly, 40(2), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v40i2.6881

- Iqtadar, S., Hernández-Saca, D. I., Ellison, B. S., & Cowley, D. M. (2021). Global conversations: Recovery and detection of Global South multiply-marginalized bodies. Race Ethnicity and Education, 24(5), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2021.1918412

- Kiramba, L. K., & Oloo, J. A. (2019). “It’s OK. She doesn’t even speak English”: Narratives of language, culture, and identity negotiation by immigrant high school students. Urban Education, 27(2), 171–187.

- Klingner, J., Boele, A., Linan-Thompson, S., & Rodriguez, D. (2014). Essential components of special education for English language learners with learning disabilities. Division for Learning Disabilities of the Council for Exceptional Children. 29(3), 93–96.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: Aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in US schools. Educational Researcher, 35(7), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X035007003

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/095183998236863

- Leonardo, Z., & Broderick, A. A. (2011). Smartness as property: A critical exploration of intersections between whiteness and disability studies. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 113(10), 2206–2232. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811111301008

- McCall, Z., & Skrtic, T. M. (2009). Intersectional needs politics: A policy frame for the wicked problem of disproportionality. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 11(2), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.56829/muvo.11.2.b231w504658752q7

- McCarty, T., & Lee, T. (2014). Critical culturally sustaining/revitalizing pedagogy and Indigenous education sovereignty. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.q83746nl5pj34216

- McDermott, R., Edgar, B., Scarloss, B., & Press, H. E. (2011). Global norming. In Inclusive education: Examining equity on five continents (pp. 223–235). Harvard Education Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). The primacy of perception: And other essays on phenomenological psychology, the philosophy of art, history, and politics. Northwestern University Press.

- Migliarini, V., Stinson, C., & D’Alessio, S. (2019). ‘SENitizing’ migrant children in inclusive settings: Exploring the impact of the Salamanca Statement thinking in Italy and the United States. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(7–8), 754–767. (https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1622804

- Milner, H. (2012). But what is urban education? Urban Education, 47(3), 556–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085912447516

- Nasir, N. I. S., & Hand, V. M. (2006). Exploring sociocultural perspectives on race, culture, and learning. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 449–475. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076004449

- Nishina, A., Bellmore, A., Witkow, M. R., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2010). Longitudinal consistency of adolescent ethnic identification across varying school ethnic contexts. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1389–1401. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020728

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. Qualitative Report, 12(2), 238–254.

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

- Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.982l873k2ht16m77

- Park, S. (2019). Disentangling language from disability: Teacher implementation of tier 1 English language development policies for ELs with suspected disabilities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.004

- Patton Davis, L., & Museus, S. D. (2019). What Is deficit thinking? An analysis of conceptualizations of deficit thinking and implications for scholarly research. Currents, 1(1), 117–129.

- Przymus, S. D., & Alvarado, M. (2019). Advancing bilingual special education: Translanguaging in content-based story retells for distinguishing language difference from disability. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 19(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.56829/2158-396X.19.1.23

- Ribet, B. (2011). Emergent disability and the limits of equality: A critical reading of the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal, 14, 155.

- Ricoeur, P. (1974). The conflict of interpretation: Essays in hermeneutics. Northwestern University Press.

- Sanatullova-Allison, E., & Robison-Young, V. A. (2016). Overrepresentation: An overview of the issues surrounding the identification of English Language Learners with learning disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 31(2), 1–13.

- Shenoy, S. (2014). Assessment tools to differentiate between language differences and disorders in English Language Learners. Berkeley Review of Education, 5(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.5070/B85110048

- Suárez-Orozco, M. (2001). Globalization, immigration, and education: The research agenda. Harvard Educational Review, 71(3), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.71.3.7521rl25282t3637

- Suddick, K. M., Cross, V., Vuoskoski, P., Galvin, K. T., & Stew, G. (2020). The work of hermeneutic phenomenology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920947600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920947600

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross, W. E., Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., Syed, M., Yip, T., … & Seaton, E. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12196

- Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. Routledge.

- Voulgarides, C. K., Fergus, E., & King Thorius, K. A. (2017). Pursuing equity: Disproportionality in special education and the reframing of technical solutions to address systemic inequities. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X16686947

- Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 319–356. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905

- Waitoller, F. R., & King Thorius, K. A. (2016). Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and universal design for learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 366–389. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.366