Summary

In the 24 paintings for the French Queen Marie de’ Medici, painted by Peter Paul Rubens 1622−1625, historic facts are depicted in the shape of mythological gods and symbols resulting in allegorical scenes. When focusing on headdress, the crowns and the wreaths rarely present a challenge in modern interpretations, but a magnificent diadem does. The grand diadem in these paintings appears to be misread in analyses today. At this point in history, the crowns and the wreaths have been transferred from divine spheres and turned into physical objects. The large diadem has not; it is still only a symbol on a goddess or for goddess-like qualities. Today, it is an easy mistake to believe that Rubens copied what he saw instead of heralding a coming fashion. Here, I suggest that it is the highest goddess Juno the Queen is personifying. Juno, a goddess for women in general, was also the saviour of the country and a special counsellor of the state. These roles are what Queen Marie took on when acting as regent for her young son, Louis XIII. By putting Juno’s diadem on Marie’s head, the divine abilities are manifested according to the allegorical language of the Baroque.

1. Introduction

In art as in real life, our attention is captured by other people’s heads, faces and eyes. On top of this central magnet, we find the crown of the head. Symbols put there are prominent and difficult to overlook. And these objects, put on top or around the head, often carry a meaning linked to an identity and a position; a crown for a king, a wreath for an emperor and a halo for a saint.

For some time, I have considered the twenty-four paintings by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) for Marie de’ Medici (1573–1642), painted 1622–1625, for the Queen’s new palace in Paris, today called Palais du Luxembourg, a very interesting example to study.Footnote1 They consist of 300 m2 of oil paintings, now hung in La Galerie Médicis in the Louvre. The large-scale paintings were made to glorify Marie de’ Medici as Queen of France, a position she held both as the wife of King Henry IV and, when widowed, as a regent for her young son, Louis XIII, (1601–1643). In these motifs where her life, until 1625, is shown in pictures, the entity of religion, mythology and regal power shows a grand result unparalleled in its time.Footnote2 They were ordered by the Queen herself for the purpose of reinforcing her position and later on to glorify her posthumous reputation. The paintings show her birth in Florence – where the gods reveal that she has been singled out for great deeds – via her marriage in 1600 to the French king Henry IV (assassinated in 1610) and conversations with the gods, and finally to a mutual understanding with her eldest son, Louis XIII, after the nonpareil civil war, The War of Mother and Son, 1619–1620.Footnote3

Rubens does not disappoint when putting images to this colourful story; with his trademark generosity, a throng of splendour can be seen in all corners of each and every scene here, and often the episode depicted is remodelled into an allegory where the Roman gods may act as alter egos for Marie and her next-of-kin. For a study on the symbolic use of crowns, wreaths and diadems in order to examine how they are to delineate roles and positions in relation to each other, and if these meanings stay the same or seem to be floating, a context like this grand cycle is a rare but essential find. The Baroque combines some important factors which are beneficial to the preferred setting: both the church and the monarchy are standing strong in society; the Renaissance has loosened up some of the stricter rules and let in the languages of antique gods in allegories, and the general use of jewelled hair ornaments in France has, just like earlier in Italy, become a growing fashion both in size and frequency.Footnote4

Needless to say, Peter Paul Rubens and his work have been thoroughly studied from a variety of angles and the research in the field keeps accumulating. Nonetheless, the question at hand seems to be new; when searching Rubenianum’s databases for “Rubens + diadem” no hits appear.Footnote5 When trying “tiara” instead, one short news item was suggested.Footnote6 That finding, a short text, mentions a sketch by Rubens of two putti carrying the papal tiara, the impressive three-layered crown of the Vatican. This demonstrates a key fact to remember; the word diadem is more appropriate to use here than tiara, where a more prominent religious aspect from the time could be considered. Also, the word diadem, Greek for “to tie around”, is more suitable for the goddesses from the antique myths than tiara, being a Persian word for a high, pointed ruler’s crown, much like the Pope’s.Footnote7

The symbol, if used as a sign for a goddess or some of her characteristics, add to the possibility of discovering traces in art of female agency in the early modern period if the symbol is read and interpreted correctly, I would like to argue. That is the reason why this study is of interest; it might show a hint of feminism at the heart of the very patriarchal French court, well-hidden under the pretence of a Roman allegory painted by the accoladed Fleming.

It is of particular significance that these paintings not only cover 300 m2, they also depict a situation where a foreign-born queen acts as regent to assist her minor son, Louis XIII. At the time, France had a strict set of rules concerning successors to the throne, the Salic law. To protect the country from, for example, hostile take-over by a foreign nation, no women could be monarchs. Since princesses could be married to a foreign prince, or they could have come from abroad initially to marry into the French royal family, their links to foreign nations might be strong. No son of a French princess could therefore inherit, only the son of a French king or prince.Footnote8 Other great kingdoms in Europe at the time had women monarchs, ruling queens, to keep the power in the same dynastic family; Austria, England, Russia and Sweden for example.Footnote9 But never France. However, a widow could temporarily serve instead of a young son. They were considered a safe choice, whereas a mother would presumably always protect the interest of her son(s).Footnote10

2. Rubens’s rhetoric plan

To glorify Marie de’ Medici, her life and her reign in majestic paintings, there would be a few rhetorical points to stress. First of all, the traditional female virtues, but also, equally important or maybe even more, the unique gifts making Queen Marie fit for the extraordinary task of ruling the kingdom. For this purpose, Rubens had to dig into a plethora of symbols from royal, mythological or divine spheres. When using them all, a wide array of possibilities opens up. However, in modern days, it might present a challenge to an interpreter.

By pure chance, Rubens was present at Maire de’ Medici’s wedding, in October 1600, in her native Florence.Footnote11 He has immortalized this early meeting with the Queen by inscribing himself in the painting he was commissioned to make in this cycle in the 1620s.Footnote12 By doing that, we are not only told he was an eyewitness, we also know he was given the opportunity for first-hand studies of art in Florence. Being not only a court painter of Vincenzo I Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua (1562–1612), the brother-in-law of the new bride, but also having “representative, diplomatic, and courtly qualities”, Rubens was part of the ducal entourage and probably stayed in the Palazzo Pitti, the residence of the Medici family.Footnote13 By commission of Ferdinand I de’ Medici (1549–1609) the preparations and the festivities were thoroughly documented.Footnote14

During the ten days of celebrations, an opera written for the occasion by Jacopo Peri, Euridice, was performed in the palazzo.Footnote15 This and other court entertainments depended on and reused material from the grand wedding of Ferdinand I to Christina of Lorraine 1589, another well-documented occasion.Footnote16 For the earlier wedding, a series of six intermezzo scenes were performed, where the first and the last showed gods and cosmological figures.Footnote17 The characters were frequently played by men at the time, and the clothes and accessories had to be easily recognized as symbols for the deities.Footnote18 The Libro di Conti from 1589 indicate a number of 320 headdresses for these scenes. They seem to have had a base of textile fabrics with decorations for symbolic communication; corals, jewels, shells, etc.Footnote19

The sketches for the scenes not only indicate gods and goddesses in the sky over the mortals, but the headdresses of the goddesses are also high-rising and pointy, similar to the design Rubens later used for the large diadems in the Marie de’ Medici cycle.Footnote20 The Florentine artist and designer of these scenes, Bernardo Buontalenti, has already been suggested as an early inspiration for parts of the settings.Footnote21 Another aspect of the designs, the headdresses, could therefore in all probability have been developed from the early cloth-based, decorated and high-rising pieces used in plays from 1589 and 1600 symbolizing different deities, to Rubens’s painted, imaginary diadems for the highest goddesses giving the impression of being made from gem-studded solid gold.

As for linking Marie de’ Medici, after the wedding executed per procurationem, the new Queen of France to Juno, the highest goddess, that was done in a spectacular way just after the celebratory dinner in Florence. Bernardo Buontalenti had staged another scene for the wedding party at Palazzo Vecchio: “after dinner, he had two carriages appear behind clouds of smoke. One of them was steered by Juno in the clothes of the future Queen of France alongside the goddess’s symbol, a peacock”.Footnote22

While in Florence, at the wedding in 1600 and during a later sojourn in 1603, Rubens had the opportunity to see the further developed mythological narrative in paintings used by the Medici family since the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote23 In a study from 2020, Ianthi Assimakopoulou describes how an added third level or category to how the family was depicted in mythological representations took form.Footnote24 Firstly, only symbols of the gods are used, this was earlier known. Secondly, the merits and virtues of the gods were suggested, while thirdly, and here is the new occurrence at the time: real historic events of the persons portrayed were shown interlaced with the mythological narrative.

By linking fiction and facts in this way, the intentions, ambitions and aspirations of the person represented were supposedly told in an intricate but clever way.Footnote25 Reading this correctly today may cause difficulties. Here, the focus is on the roles the head attire in general symbolizes, but more specifically the large diadem which makes a few appearances in this cycle of 24 paintings.Footnote26 Transporting the symbol of a diadem from a goddess to represent a few abilities and aptitudes ought to sort in the earlier known categories; the first and the second levels of mythological representation. So even if Rubens and Marie de’ Medici also use the third level of rhetoric in the paintings, the links to more specific historic knowledge, of battles won, alliances, or complications between mother and son, may not be called for in the explanations of the particular paintings in question.Footnote27 The history of the diadem though, as a mere symbol or as a physical item, meaning the difference between an existing or a non-existing headpiece, will be crucial. Also, a range of abilities of the highest goddess will need to be considered.Footnote28

In the paintings showing the birth, childhood and marriage in Florence, Marie de’ Medici is shown with head ornaments portraying her as a “good girl” and an “appropriate bride”.Footnote29 At her birth, she permeates a subtle light; it looks like a nimbus around her head, a sign of being “a chosen one”; a reliable and good person. During her education and when having her portrait presented to Henry IV, she wears jewelled hair ornaments of a modest size. Pearls are chosen for a necklace and for the hair signifying purity and chastity.Footnote30 In the last painting of her, still residing in Florence, at her wedding by proxy, a bridal crown, a definite symbol of virginity, gives her extra height and serene splendour.

The first time Queen Marie herself is inscribed in mythologic scenes taking on the identity of a goddess, is when the King of France has been united with his new bride, . The two of them are portrayed in the sky as Juno and Jupiter. Juno, the highest goddess in Roman mythology, a married woman, has brought her typical peacock and Jupiter, her husband and the highest god, has his eagle beside him.Footnote31 To an observer who has started from the beginning of the cycle, Juno and Jupiter have appeared twice before with more anonymous faces; Juno in the same type of diadem, a high-rising, pointed design in pearl-studded gold, and 5. This time, in , L’arrivée de la reine à Lyon, the faces have changed into those of the King and Queen. Queen Marie has the prominent diadem, King Henry has more of a ribbon tied around his head, something seen on Jupiter before, .

Figure 1. Painting no 10 in the cycle. L’Arrivée de la reine à Lyon, Peter Paul Rubens, 1622–1625. INV 1775; MR 966, height 3.94 m, width 2.95 m. Oil on canvas, photograph © 2003 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier.

The next time this type of diadem can be seen on Marie de’ Medici is in the painting called La félicité de la régence or The Felicity of the Regency, , which is the epitome of the entire cycle of paintings. With a sense of humour, it might be seen as amusing, since this quite central painting was an emergency solution; the original painting showing how Queen Marie was banished from Paris by her son, the new king, was rejected at the very last minute.Footnote32 It was not the Queen herself who was opposed to the motif, but her son and probably cardinal Richelieu who made sure to exclude it.Footnote33 Rubens had to produce another large painting, a scene which would appeal to everyone, in just a few days. This is how we know that this painting was completely made by Rubens’s hand with no help from assistants.Footnote34 It was made in Paris in great haste in spring 1625, just before the grand marriage between one of Queen Marie’s daughters, Henriette Marie or Henrietta Maria, and the future King Charles I of England.Footnote35 Without this painting, the importance of the different interpretations of the diadem might not have been conspicuous. However, with this splendid scene of Marie de’ Medici blissfully reigning from a throne, in addition to knowing that every detail is planned and executed by Rubens himself, the symbol is deliberately chosen for the Queen’s head.Footnote36 But first, before demonstrating the indications, there is a third occurrence of this headpiece on the Queen’s head, .

Figure 2. Painting no 18 in the cycle. La Félicité de la Régence, Peter Paul Rubens, 1625. INV 1783; MR 974, height 3.94 m, width 2.95 m. Oil on canvas, photograph © 2003 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier.

Figure 3. Painting no 19 in the cycle. La Majorité de Louis XIII. La reine remet les affaires au roi, le 20 octobre 1614, Peter Paul Rubens, 1622–1625. INV 1784, MR 975, height 3.94, width 2.95 m. Oil on canvas, photograph © 2003 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier.

The allegory in La majorité de Louis XIII, the painting showing how the Dowager Queen leaves the power to her son at his 13th birthday, the age of majority at the time, might have been seen as a stroke of genius. The picture of France as a ship on the ocean had been utilized frequently within the royal family, and by putting the young king at the helm with the mother close by, would put Marie de’ Medici in a better position – showing her in the centre still – than a motif from the actual coronation setting, where the Queen Mother had a much lower and peripheral position.Footnote37

Nevertheless, this composition is truly disturbing. It is the combination of what Marie de’ Medici is wearing on deck of this mythological vessel which is problematic. Mythological goddesses are never widows dressed in black; their husbands are immortal. And real-life women are in all probability not combining a modest mourning wardrobe with a large, striking piece of jewellery. This scene is, according to Assimakopoulou’s theory, sorting under the third category of mythological motifs, invented in Florence for the Medici family in the sixteenth century, where a historic event is transferred into an allegoric scene full of people and attire from Roman mythology.

In the three large-scale paintings, , the high-rising, gem-studded golden diadem, seen on Juno as herself earlier in the cycle, , is put on the crown of the head of a Queen of France. Rubens uses the same design idea every time. Rubens was a master of decorations, never shying away from ribbons, flowers or pretty little gems.Footnote38 Would not he, of all painters, have been able to show a variation if he intended there to be one? Similarly, or to put it more simply, if the symbols look the same, would they not have been intended to be translated as the same? In a magnificent cycle of mythological allegories, a significant aspect will be the identifying items of each god, and more particularly here, of the highest goddess herself, since it is the Queen of the country who is the protagonist of this painted biography.Footnote39

Figure 4. Painting no 4 in the cycle. Les Parques filant le destin de la reine Marie de Médicis sous la protection de Jupiter et de Junon, Peter Paul Rubens, 1622–1625. INV 1769, MR 960, height 3.94, width 1.55 m. Oil on canvas, photograph © 2003 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequierand.

Figure 5. Painting no 7 in the cycle. Henri IV reçoit le portrait de Marie de Médicis et se laisse désarmer par l’Amour, Peter Paul Rubens, 1622–1625. INV 1772, MR 963, height 3.94 m, width 2.95 m. Oil on canvas, photograph © 2003 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier.

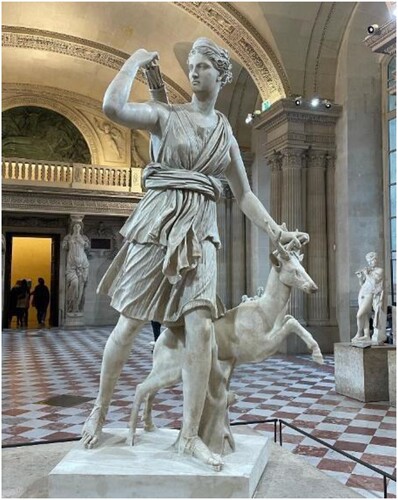

Showing the King and Queen of France as Jupiter and Juno was not innovative. That sorted under the first two categories of mythological allegories, which had been known and used for some time. This very example, Henry IV and his queen, Marie de’ Medici, as Jupiter and Juno, had been done before during their marriage. There is another example, a pair of bronze statuettes of them made some time between 1600–1610.Footnote40 Juno’s peacock is there, and the lack of appropriate attire is only marking the glorious heroic nudeness, a way to indicate that the ordinary laws for humans do not apply, meaning this is a goddess, . There is no diadem, but if there were, it might have been a more generic model, which was often chosen by artists, much like the one that had been seen at the French court since 1556 on the marble statue of the Roman goddess Diana, .Footnote41

Figure 6. Statuette: Marie de Médicis en Junon, Barthélémy Prieur, 1600–1610, bronze, 63 × 30 × 26 cm. © 1990 RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Daniel Arnaudet.

Figure 7. Artémis, déesse de la chasse, know also as “Diane de Versailles”, Italian copy appr. 125–150 A D, marble. MR 152, N 1157, Ma 589, height 200 cm, width 139 cm, depth 103 cm. Musée du Louvre, author’s photograph.

To be consistent and stress the divinity symbol in the 1620s, now that little bejewelled head caps, where pearls were embroidered on cloth on rails of this crescent form, had entered fashion, Rubens himself must have invented a state-of-the-art conversation piece to this end; an image of a truly heavenly piece of expensive jewellery.Footnote42 Considering the fact that nothing similar existed at the time, in terms of material items to put on a living woman’s head for any sort of ceremonial use, this argument is hardly implausible.

3. The impact of the impressive diadem

Today, in an age where material culture is abundant and dominant, where no sumptuary laws restrict different classes from buying or wearing gold, silk or ermine, the mere idea of wearing an imaginary golden diadem in a painting because it is a symbol of someone else’s qualities and agency, can be difficult to fathom. Even when the mythologic setting and its properties, as in this case, overrides the general regal story-telling, the headdress of a goddess is easily confused with an earthly crown for monarchs and regents when put on the head of Queen Marie. But outside the world of arts, it simply did not exist at the time as a material object. Geoffrey C. Munn describes how only artists and very cultivated people kept the general idea of this item alive:

Of all the many types of jewellery, the tiara is without doubt the most flattering and imposing. It is not easy to understand, therefore, why it remained in obscurity for so many centuries. It would be wrong to assume the form had been forgotten, since scholars, painters and sculptors clearly had knowledge of it. Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71), for example, was quite conversant with the jewellery of the Ancients. In his famous memoirs he noted that Pope Clement VIII had shown him an Etruscan gold necklace of seemingly inimitable refinement that had just been found in the ground. The spade and plough were also turning up ancient gold head ornaments for connoisseurs and collectors to marvel at, but little attempts to wear these jewels, or even simulants of them, seem to have been made until the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.Footnote43

Comparing my thoughts on Queen Marie in the eye-catching diadem with that of a few others’, those few whom I have found mentioning it at all, even if just briefly, will explain how divergently the symbol is read. In the tenth painting in the series, , L’arrivée de la reine à Lyon, Juno with diadem and two peacocks sits on a cloud with Jupiter and his eagle, the lady with a bare breast, the man with only a red cloth over his legs, the nudity indicating the mythological realm of the setting. This time, unlike painting no 4 and 7, and , the faces are those of Marie de’ Medici and Henry IV. This is the first time the two spouses meet, after their formal ceremony by proxy a month earlier. Being wedded to the King, personified by the highest god Jupiter, Queen Marie can now be presented as the wife, the highest goddess Juno, a married woman, seen as the protector of women in general and women in confinement. In the Rubens biography from 1998, Kristin Lohse Belkin mentions the Queen in this portrait and identifies the duplicity briefly by stating that “Marie, as Juno, is dressed in classical style, one breast exposed; on her head is a diadem, as befits the status of both women”.Footnote44 By this explanation, Belkin reveals that in her opinion the diadem fits both the goddess and the Queen at the time, as if it existed in a queen’s jewel case in those days, and maybe also that it was an exclusively royal headdress.

From my standpoint, the diadem belongs to Juno and is only an immaterial symbol which is lent to Queen Marie when the latter takes on the identity of the goddess, in an allegorical painting, to show us that the Queen materializes certain values and qualities of this specific deity. Belkin discerns that Queen Marie is shown as Juno, with the breast exposed, but then the diadem, instead of underlining the interpretation, is read as fitting both worlds, when it did not yet exist as a material object. Thereby, Belkin could be missing an important point in this cycle.

The painting called La félicité de la régence, , the one painting that could serve as a brand for the entire cycle of motifs glorifying Marie de’ Medici as the Queen of France, also gives reasons for different readings originating in the symbols. In the comprehensive study from 1989, Heroic Deeds and Mystic Figures – A New Reading of Rubens’ Life of Maria de’ Medici, Ronald Forsyth Millen and Robert Erich Wolf describe the scene: “She is at her most regal, [—]. She is diademed and wrapped in a royal ermine-lined blue mantle strewn with the lilies of France”.Footnote45 The diadem, the ermine, the blue mantle and the French lily are juxtaposed in a royal ensemble of symbols with no consideration to the fact that the diadem is not the crown Queen Marie was given at her coronation, painting no 13 in the cycle, or that it until now only has been used for prominent goddesses.Footnote46 It is simply noted en passant as material regalia, an echo of Belkin’s words mentioned above. But Millen and Wolf still stress the difference from everyday realities: “[…] the artist transformed her from a human queen into an allegorical personification by the simple expedient of baring her right breast, thus exalting her from the plane where human decorum rules”.Footnote47 They land in an allegorical picture – thereby stressing that the breast is not maiden-like – but the diadem is seen as transported out of the mythology and into the secular sphere and its material finery. According to them, the diadem is one of the items linking Marie de’ Medici to a queen on her throne, giving it a worldly meaning, even though they read the overall meaning as an allegory all the same.

This joyous scene, with Marie de’ Medici on a throne in prosperity and bliss, has also been seen as pure mythology by Susan Saward in her dissertation from 1978.Footnote48 Saward calls the painting Marie de’ Medici as Patroness of the Fine Arts, which differs remarkably from the six different, possible titles mentioned in a recent French research summary.Footnote49 All these titles indicate how the Queen rules the country into prosperity.Footnote50 Being a patroness of the arts may be included in that, I am willing to concede, but reducing the entire task to having that field as a sole focus would be belittling. The Queen chose the phrase Pax Optima Rerum, nothing is better than peace, as her motto, and over her head the Roman corona civica is hung, a wreath of oak leaves only given to people who had rendered crucial services to society.Footnote51 That would imply a person of the utmost importance. However, Saward sees a goddess of a lower rank, a virgin who will bring back a Golden age, the young and innocent Astraea.Footnote52 The widowed Queen Mother, regent of France with six children, shown at her throne in full glory, would she voluntarily choose to be portrayed as a lower goddess, a young virgin?

Reading the painting as a woman of innocence would also be possible if trying to find parallels between Queen Marie on her throne and the Queen of Heaven, Virgin Mary. This is a correlation Alexandra L. Ziegler explored in a study from 2015.Footnote53 The motif is, according to Ziegler, the most abstract one in the cycle, and Queen Marie can be seen as a strong and heroic incarnation of Virgin Mary leading to the reconciliation with the son later on in the cycle of paintings. Even if there are a few similarities in the composition with the well-known Marian scenes like the Virgin on the Throne of Heaven, Madonna Lactans where the virgin breastfeeds the child, and Sacra conversazione where Jesus sits in her lap, there is no child in her lap being fed, and there are no saints in conversation with her. Most of all, I adduce that what gives Queen Marie power is the fact that she was married to the King, she is a widow with six recognized royal children – possibly symbolized by the six little ones around her here – and she would not erase her own temporary legitimacy to the throne of her minor son by appearing as Virgin Mary. If the large diadem should be read as the Virgin’s crown, Rubens could have moulded it after the wedding crown, a Marian symbol, in one of the earlier paintings; it would look much more like a circular item.

The question of comparing Queen Marie to Virgin Mary, and the Throne of France to the Throne of Heaven in Rubens’s interpretations has been tried before. In 1972, Robert W. Berger looked into the similarities between the paintings where Marie de’ Medici sits on her throne, no 14 and 18 in the cycle, and those of Virgin Mary in the same position.Footnote54 Berger concludes that Rubens had to be careful balancing on the right side in this daring venture, since Marie de’ Medici had no claims on being portrayed as a religious saint. The Virgin Mary metaphors always stand back, according to him, to the classic symbols from Antiquity. This, in my perspective, could be the reason why Queen Marie is not given a crown, and the solution is in clear sight; the grand headpiece from a goddess is neither a symbol for regal nor religious powers, where crowns could be mistaken for each other.

La félicité de la régence is designed to visualize the good reign during Queen Marie and her regency.Footnote55 The Queen was a widow at this stage in her life, and the only times Rubens decides on not showing her clad in black, after the assassination of her husband, is when the mythological language is strong enough to override this, I believe. Dressing as a widow worked well in her favour, due to the unique position the Salic law provided a Queen Mother.Footnote56 To change this advantage, to be shown as a virgin instead, would not be an enticing alternative. But an allegory of a goddess might work, since Queen Marie would then be able to appear in full glory with bright colours and gold instead of being all in black, when the intention is to show the country’s wealth, prosperity and splendour.

The interpretation made here, after analysing the possibilities at hand, is that Rubens keeps Marie de’ Medici depicted as Juno, the preeminent goddess. Introducing new allegories would be unnecessary risky when having to create a new painting in just days.Footnote57 Keeping the Queen as Juno links her to her Jupiter, her husband the King, which still shows her as a loyal wife. In doing so, she does not lose her role; she reinforces it with the mythological marriage. And therefore, the diadem should be executed as on Juno earlier, and put on the Queen’s head.

When looking into what tasks and abilities Juno supposedly had, finding convincing arguments to why she would be such a desirable match to be compared to, the more elaborate meanings are not often explained in general encyclopaedias. But except for being a matrimonial role model, and a prototype for good wives and mothers, it turns out she had a few important, more political strings to her mythological bow; as the most prominent goddess she was also protectress of the Roman empire and a special counsellor.Footnote58 A description as a “protectress of the country” would suit a widowed mother ruling instead of a minor son very well, and a “special counsellor” could be an appropriate title for a woman who has been allowed into the highest council, where women normally had no admission. These fitting characteristics, where this French Queen meets with all the roles of Juno, could hardly be a coincidence in this case, when portrayed to be immortalized in a grand cycle of paintings by Rubens. These meaningful connections must instead be a perspicacity intentionally planned.

During the probably very turbulent days, when King Henry IV was murdered in the streets of Paris and the Queen was supposed to stand in as a regent for their minor son, Louis XIII, a poem was written in her honour. The main theme is about her apt seamanship and how it will save the ship, France, from foundering.Footnote59 The same theme is what Rubens builds on in the painting La majorité de Louis XIII, , where the Queen this time returns the ship to the succeeding King, her son. The setting, the ship on the ocean, and the crew are collected from mythology, but the young king and his mother are not included in that sphere. The young Louis XIII is dressed in worldly regal attire and the Dowager Queen is in mourning dress. This scene and the story-telling is an example of how a historic event is depicted within the frames of mythology to create a powerful allegory. This is an example of the third level as described earlier by Assimakopouplou, the innovation from Florence and the de’ Medici family, which both Queen Marie and Rubens had met with a few decades earlier in Italy.

The remarkable in the composition is how the balance between the world of the gods and the realm of the living is preserved. The key factor, which is both disturbing and linking these different universes, is the diadem. Take out the King and the Queen, and everything left can be read as mythology.Footnote60 The King is a full and worthy ambassador of the everyday material world as we know it, but the Queen – what does she represent here? Her body, in black mourning, follows an earthly dress code; no goddess is ever widowed, but her head is embellished with the strikingly conspicuous diadem again.Footnote61 This diadem does not exist in the material world at the time, and matching remarkable jewellery with mourning clothes would negate the intention of a widow’s humble black.Footnote62 The Queen seems to be of both worlds, she is a link here between heaven and earth; she stands loyally next to her son, fulfilling the obligations as his mother and as the Dowager Queen, but her mind has divine connections and also the desirable talents of Juno. Queen Marie, in that case, continues to be the “protectress of the state” and the “special counsellor” to her son. She keeps and justifies her place in the centre of the painting, the centre of the country; the natural place in the painted biography of her life this cycle was ordered to depict. And it is the symbol of the diadem, Juno’s noticeable headdress in these paintings, which is the key factor to rhetorically stress her abilities and the fate designed for her by both the Christian god and the Roman deities.Footnote63

4. Rubens’s possible deliberation when putting his divine diadem on Queen Marie

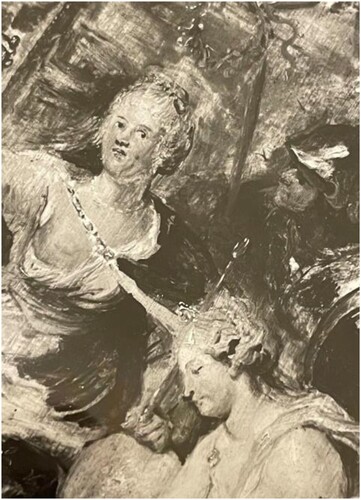

Any elaborate thoughts behind the composition with the divine diadem on Queen Marie’s head, while wearing regal or mourning dress, in the two paintings discussed above, La félicité de la régence and La majorité de Louis XIII, have not been found in archives or other studies, to my knowledge. However, when written documentation is missing, there can sometimes be other elements of interest. What Rubens did not put in writing, he might have put in sketching. For this cycle, there is some early material saved for a handful of the paintings. Luckily, the two above are among those. In and , sketches for and can be compared with the finished result in oil.

Figure 8. Sketch for painting no 18 in the cycle, (photographic copy) photographed by the author in the Louvre archives, 2022-01-21, marked “Glückliche Regierung der Königin, Munich”, detail.

Figure 9. Sketch for painting no 19 in the cycle, for Wikimedia commons by Pinakothek München, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peter_Paul_Rubens_217.jpg.

The matter of interest, what headdress originally used for the Queen, finds an answer; in the goddess next to the Queen has a few details which indicate a high, pointed diadem, but Queen Marie’s head is still uncovered waiting for a decision; in the young King Louis has a crown and his mother wears only a headcloth. The lack of headdress for the Queen is a demonstration, I suggest, of two things; firstly, she did not have a grand diadem for such occasions, and secondly, using the spectacular head-piece of Juno on a mortal was not an amalgamation Rubens used without careful and long deliberation. It was made to prove a point; it was not mere decoration as often though in our time, and by seen as such unfortunately unappreciated as the distinguished role symbol it was and still is in its context.

The question arises whether the grand diadem differs when seen on Juno or on Queen Marie/Juno. Without going into details difficult for a visitor to see from the floor, the top gem on Juno’s diadem is a pearl both times she appears, and , and for the Queen/Juno it varies, perhaps according to what needs to be communicated in the particular situation. When Marie de’ Medici first arrives from Florence, meeting her husband Henry IV, the large top gem is red. Rubies were at the time the costliest of gems.Footnote64 It was also used, along with diamonds, to single out the Medici women in important circumstances, being of the family’s colours.Footnote65 At the time, rubies were considered the second most esteemed stone, after diamonds, according to theories pertaining to the four elements.Footnote66 A large ruby for Marie de’ Medici would therefore represent her rich Florentine family well. It has been argued though, that Rubens favoured the use of the colour red, among the brighter jewel colours, but in this painting an abundance of different pigments is displayed, manifested for example in a rainbow in the top left corner, , contradicting any suspicion of a reduced palette.Footnote67

The second time Queen Marie appears as Juno, on the throne, , the central prong resembles a golden fleur-de-lis. Not only is this giving the diadem an extra elevated design and appearance, but it is also indicating her, in this position, more loyal to France and the royal dynasty than to her original de’ Medici family. The visible gemstones adorning the base seem dark and difficult to identify.

The third and final occurrence, , on the mythological ship, the top gem is a pearl again, linking back to the argument that Queen Marie, even if dressed in mourning, is borrowing the headdress from Juno. Rubens may even had accentuated the point, using the pearl for the middle prong, to remind an observer to read this detail purely mythologically, when the earlier clue, the revealed breast, was incompatible with the black mourning attire. Another detail, indicating the diadem ought to be read as borrowed from Juno, is the hint of a veil at the back of the Queen’s head.Footnote68

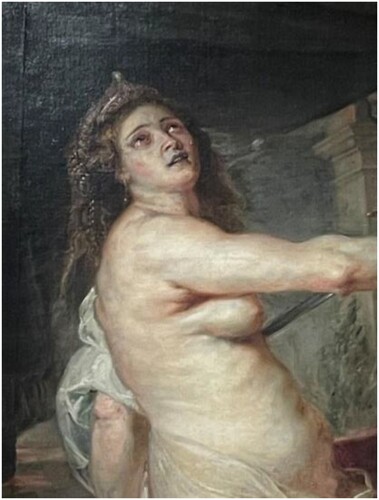

If Rubens hesitated to put this creation of his, a gem-studded, pointed golden diadem, on a mere mortal, even if royalty – did he use it elsewhere, one may wonder. Except for a few more similar ones adorning higher goddesses in the cycle for Marie de’ Medici, Rubens would admittedly have had the chance both before and after 1622–1625. This inquiry, a general headdress survey on all women of every sort painted by Rubens throughout his life, is no subordinate question here, it would deserve better attention. But evidently the question remains, since there were no findings to the search for “Rubens + diadem”, and only one, the Pope’s impressive crown, for “Rubens + tiara”. Browsing through catalogues of his works, it seems Rubens used this model of diadem both before and after the Paris commission, and the examples found are basically from allegories or myths.Footnote69 An example is Dido at the verge of suicide, . Short as the secondary head-piece search has been, it supports the theory of a grand mythological diadem in Rubens’s world, which would be a symbol for divine qualities when transferred to a living woman in allegories, meaning Marie de’ Medici, Queen of France, as a possible unique occurrence. Whether it is the only instance or not, it is a quite exemplary demonstration from the Baroque of how the allegoric narrative builds its fundamental teller’s technique when turning history into visual chronicles.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for all support, interest and generosity during the work process of the original study and this article. Many have assisted in various ways, a special thanks to: Tutor: Carolina Brown Ahlund, Associate Professor, PhD Senior lecturer, Department of Art History, Uppsala University, Sweden. Course director: Johan Eriksson, Associate Professor, PhD Senior lecturer, Department of Art History, Uppsala University, Sweden. The anonymous peer reviewers for their comments and suggestions. John Behnan, for eminent support in matters pertaining to the English language. The Louvre Archives, Paris. Rubenianum, Antwerp. Swedish Institute/Institut Suédois, Paris, researcher-in-residence grant, January 2022 and July 2023.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Louvre has a special introduction for the paintings and the room; www.louvre.fr/en/explore/the-palace/to-the-glory-of-a-queen-of-france, accessed 2022-08-06.

2 Geraldine A. Johnson, “Pictures Fit for a Queen: Peter Paul Rubens and the Marie de’ Medici Cycle”, first published in Art History 16, September 1993, here from Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (ed.), Reclaiming Female Agency – Feminist Art and Theory after Postmodernism, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2005, p. 101.

3 The paintings referred to specifically are no 4 Les parques filant le destin de la reine (the gods plan her destiny), no 5 La naissance de la reine (born with a halo, meaning she was singled out by the Christian god too), no 8 Le marriage par procuration, no 15 Le concert (ou conceil) des dieux and no 23 La parfait reconciliation de la reine et de son fils.

4 Kristina af Klinteberg, “Cennino Cenninis gyllene diadem – en studie kring vad ordet diadema kan betyda i Il libro dell’arte”/ “Cennino Cennini's Golden Diadem: A Study on the Meaning of the Word Diadema in Il libro dell'arte” master’s thesis, Linköpings universitet, Sweden, 2021, pp. 34–35.

5 Results from 2022-02-10.

6 J. G. van Gelder, “Rubens Marginalia 1”, The Burlington Magazine, July, 1978, Vol. 120, No. 904, pp. 450 + 455–457, accessed 2022-02-10.

7 Diadem from Greek “tie around”; the etymology in Oxford English Dictionary, accessed 2022-08-06; https://www.oed.com/dictionary/diadem_n?tab=etymology#6912601 and Tiara from Persian kings' high headdress, in Hans Biedermann, Symbollexikonet, trans. Paul Frisch and Joachim Retzlaff, Forum, Stockholm, 1992 (1989), p. 413.

8 Fanny Cosandey, La reine de France – symbole et pouvoir, XVe – XVIIIe siècle, Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 2000, first chapter “La loi salique”, pp. 19–54.

9 Karin Tegenborg Falkdalen, Kungen är en kvinna: retorik och praktik kring kvinnliga monarker under tidigmodern tid [The king is a woman: the female monarch in rhetoric and practice during the early modern era], diss., Umeå universitet, Umeå, 2003, p. 48.

10 Nicola Courtright, “A New Place for Queens in Early Modern France”, in Fantoni, Marcello, George Gorse and Malcolm Smuts (ed.), The Politics of Space: European Courts ca. 1500–1750, Bulzoni Editore, Rome, 2009, pp. 267–292, p. 279.

11 Ronald Forsyth Millen and Robert Erich Wolf, Heroic Deeds and Mystic Figures – A New Reading of Rubens’ Life of Maria de’ Medici. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1989, p. 15.

12 Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 54.

13 Madeline Delbé, “Peter Paul Rubens in Florence: Between Art, Feasts, and Diplomacy”, in Morselli, Raffella and Cecilia Paolini (eds.), Rubens e la Cultura italiana 1600–1608, I libri di Viella, Rome, 2020, pp. 51–66, pp. 53–54, the quotation on qualities p. 53.

14 Delbé, 2020, 54: Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (1568–1646), Descrizione delle felicissime nozze della cristianissima Maestà di Madama Maria Medici regina di Francia e di Navarra, published 1600.

15 Charles Wilson, The Transformation of Europe 1558–1648, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1976, p. 192.

16 James. M. Saslow, The Medici Wedding of 1589, Florentine Festival as Theatrum Mundi, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1996, p. 3.

17 Saslow, 1996, p. 61.

18 Saslow, 1996, p. 60.

19 Saslow, 1996, p. 65.

20 Stage design, Intermedio 6, Bernardo Buontalenti. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, no. E.1189-1931, 1589, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O748951/drawing/, accessed 2023-08-17, and a headdress design, Bernardo Buontalenti, 1589, www.themorgan.org/drawings/item/187719, accessed 2023-08-17.

21 Riccardo Spinelli, “Feste e cerimonie tenutesi a Firenze per le ‘Felicissime Nozze’”, in Caneva, Caterina and Francesco Solinas (eds), Maria de’ Medici una principessa Fiorentina sul trono di Francia, Firenze Musei, Sillabe, Livorno, 2005, p. 136.

22 Delbé, 2020, p. 56, referring to and partly quoting a letter from Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580–1637) to Rubens, Correspondance de Rubens et documents épistolaires concernant sa vie et ses œuvres, edited by M. Rooses and C. Ruelens, 6 vols., Antwerp 1887–1909 (Codex Diplomaticus Rubenianus), III, no. 293, pp. 57–62: p. 57.

23 Dominique Jacquot (ed.), Rubens: Portraits princiers, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, 2017. p. 9.

24 Ianthi Assimakopoulou, The Offspring of the Medici: A Visual Dialectic between Myth and History (1537–1609), Editoriale Sometti, Mantua, 2020.

25 Assimakopoulou, 2020, pp. 25 f.

26 Juno and/or Marie in the diadem are found in Les parques filant le destin de la reine, La présentation du portrait, La rencontre à Lyon, La félicité de la régence and La majorité de Louis XIII.

27 The period is remarkable indeed, so is the life of the Queen. In Wilson, 1976, p. 235, the author does not mince words: “The seven years of Marie de Medici’s regency inaugurated four decades during which, spasmodically, the monarchy and its ministers were targets for attack by noble faction. She was herself vain, bad-tempered and impressionable”. In the end, her son, Louis XIII, banished her from the country. The cycle of paintings does not cover that part of their lives.

28 Thomas Wentworth Higginson. “The Greek Goddesses”, New England Review (1990-), 28, No. 4, 2007, pp. 194–207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40245042. accessed 2023-08-30 (Higginson lived 1823–1911, this essay was first published in 1869), p. 195, on the personalities of goddesses. Higginson means descriptions often omit too much: “It may be that the mythologists think the view beneath them; but it is hard to find in any language an essay which lays all these abstruser things aside, and treats the deities in their simplest aspect, as so many Ideals of Womanhood”.

29 The paintings are La naissance de la reine, L’instruction (or éducation) de la reine, La présentation du portrait and Le mariage par procuration.

30 Heather L. Sale Holian. “Family Jewels: The Gendered Marking of Medici Women in Court Portraits of the Late Renaissance”, Mediterranean Studies, 17, 2008, pp. 148–182. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41167396, accessed 2023-08-17, p. 157: “Renaissance lapidaries associated pearls with purity and chastity, two virtues highly valued, and indeed essential in a respectable woman. As a result, pearls are a ubiquitous component of every sixteen-century female aristocrat’s dress, regardless of her personal tastes, or the symbolism of any accompanying gemstones”.

31 R. D. Weigel, “The Duplication of Temples of Juno Regina in Rome”, Ancient Society, 13/14, 1982, pp. 179–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44080151, accessed 2023-08-30, p. 179: From a very early date, Romans probably thought of Juno as Regina, as the constort of Jupiter Rex.

32 Susan Saward, The Golden Age of Marie de’ Medici, diss. UMI Research Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1982 (1978), p. 142, and Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 165.

33 Saward, 1982, p. 142.

34 Kristin Lohse Belkin, Rubens, Phaidon Press Ltd, London, 1998, p. 176, and Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 165.

35 Saward, 1982, p. 142.

36 Higginson, (1869) 2007, p. 199: only Hera/Juno commands like a queen.

37 Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 170.

38 J. Vanessa Lyon, Figuring Faith and Female Power in the Art of Rubens, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2020, p. 23. Lyon describes how the word “rubenesque” originally (appr. 1815) was used to describe Rubens’s partiality for decorations such as ribbons and flowers.

39 Higginson, (1869) 2007, p. 199, Hera/Juno acts superior to everyone bar her husband.

40 Marie de’ Medici as Juno and Henry IV as Jupiter, bronze statuettes, 1600–1610, by Barthélémy Prieur (1536–1611), https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010114099 and https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010101101, accessed 2023-08-23.

41 This statue, called “Diane de Versailles”, has been at the centre of the French court since 1556; first at Fontainebleau in the gardens, a gift from Pope Paul IV to Henry II. During Henry IV, 1602, she came to the Louvre in central Paris, and 1696 she was taken to Versailles, according to exhibition text 2022-01-30, catalogue number Ma 589. Today, she resides inside the Louvre.

42 The pearl and jewel-embroidered headpiece from the 1500s and on, can be studied in François Boucher, A History of Costume in the West, Thames and Hudson, London, 1997 (1965), chapter VIII “The Sixteenth Century”, pp. 219–250. The headdresses designed for the operas and plays in Florence 1589 and 1600 might have had the same high-rising silhouettes but were not intended to be used outside a stage, nor were they made of durable, expensive materials according to the Libro di Conti, as earlier mentioned.

43 Geoffrey C. Munn, Tiaras – A History of Splendour, ACC, Woodbridge, 2011, pp. 20–21.

44 Belkin, 1998, p. 185.

45 Millen and Wolf, 1989, pp. 164–165.

46 See appendix 1 of the original study “Crowns, Wreaths and Diadems as Role Symbols in Rubens’s Marie de’ Medici Cycle”, https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1664933/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

47 Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 164.

48 Saward, 1982 (1978), p. 142.

49 Emmanuelle Hénin and Valérie Wampfler, Memento Marie – regards sur la galerie Médicis, EPURE/Éditions et Presses Universitaires de Reims, Reims, 2019.

50 Ibid, p. 14.

51 Birgit Bergmann, Der Kranz des Kaisers: Genese und Bedeutung einer Römischen Insignie, diss., Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York, 2010. The different types of wreaths are listed and explained inside the back cover.

52 Saward, 1982, p. 142.

53 Alexandra L. Ziegler, “Divinity & Destiny: Marian Imagery in Rubens’ Life of Marie de’ Medici”, master’s dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, 2015, pp. 2–3.

54 Robert W. Berger, “Rubens and Caravaggio: A Source for a Painting from the Medici Cycle”, The Art Bulletin, 54, no. 4, Dec. 1972, p. 476, CAA.

55 According to the presentation text at the Louvre, January 2022, and on their website, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010060835. accessed 2022-08-06.

56 Jean-Francois Dubost, Marie de Médicis – La reine dévoilée, Payot & Rivages, Paris, 2009, chapter 30: “Quelle place pour la reine mère? 1619–1624”, s. 626–650.

57 Jacques Maroger, The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters, trans. Eleanor Beckham, Studio Publications, London and New York, 1948, pp. 93–120, “Chapter XI: Rubens”. Maroger, painter and former technical director of the Louvre Museum’s laboratory in Paris and president of the Restaurers of France, is impressed by Rubens’s speed in general, p.103: “We, today, could scarcely believe this speed if we did not have an account of it in the letters of the period”.

58 Weigel, 1982, p. 192: “She gave particular help and inspiration […] and helped bring Rome through the crises of the Second Punic War”, p. 179: there were several cults and temples for Juno(s) in Rome; “A determination of why she needed more than one temple is intricately involved with Roman political, social, military, and religious traditions”. www.britannica.com/topic/Juno-Roman-goddess, accessed 2022-02-01. Also in Collier’s Encyclopedia, vol 13, Macmillan Educational, New York, 1996, p. 677: Juno is described as “the principal protectress of the state”, and in The New Encyclopædia Britannica, vol 6, Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago, 1992, p. 657: as “eventually a saviour of the state”.

59 François de Malherbe, “Ode à la reine sur les heureux succés de sa régence, 1611”, in L. Moland (ed.) Œuvres poètiques, Paris 1896, VII, 252, as referred to by Saward, 1982, s. 161.

60 Millen and Wolf, 1989, pp. 169–173.

61 I have not found the diadem mentioned in any of the analyses earlier read. Millen and Wolf, who connected it to the rest of the regalia in La félicité de la régence, only describe the Queen as very modest in this painting, without any reference to the headpiece: “She is the very image of modesty, humility even: an iron will in net fishu and satin gown”, Millen and Wolf, 1989, p. 170.

62 In the early 1800s, a black diadem made from jet or French jet/Vauxhall glass could be used with black evening wear, this is not it, and it is not yet the time either, see Kristina af Klinteberg, Smycken som huvudsak, Kulturhistoriska Bokförlaget, Stockholm, 2018, p. 73.

63 The halo-like nimbus from her birth as mentioned above, La naissance de la reine, and the Roman gods spinning her destiny; Les parques filant le destin de la reine, paintings no 5 and 4 in the cycle.

64 Holian, 2008, p. 150: Holian refers to Benvenuto Cellinis book from 1898, London, The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture, p. 23.

65 Holian, 2008, p. 152: “[…] this marking always occurred at critical times in the life of the woman depicted vis-à-vis her relationship to the dynasty”.

66 Vannoccio Biringuccio, The pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio [De la pirotechnia], M.I.T. P., Cambridge, MA, 1966, p. 123. The book was first published in Venice in 1540.

67 Maroger, 1948, pp. 115–116: Maroger claims that Rubens sometimes limited his colours to little more than brown, black, white and red, however giving the viewer an impression – from a distance – of perceiving violets, greens, blues, etc.

68 Higginson, (1869) 2007, p. 199: Hera/Juno is the only goddess wearing a diadem and a veil. Rubens also uses this combination on Marie/Juno in .

69 1617: Allegory of Sight in The Five Senses in Five Paintings, The Prado Museum, Madrid; 1634: The Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland, Banqueting House, London; appr. 1635–1638: La mort de Didon, reine de Carthage, The Louvre, Paris, and appr. 1638–1639: The Judgement of Paris, The Prado Museum, Madrid. There is a similar composition on the head of the main lady in Tomyris has the Head of Cyrus the Great Bathed in Blood to Avenge the Death of her Son, 1620–1625, The Louvre, Paris, where the historic queen from the Histories by Herodotus, fifth century B.C., takes her place among mythic legends as an early female avenger.