Abstract

The late-eighteenth-century Swedish intellectual C. A. Ehrensvärd visualised his life and relationships in drawings that often represent their modern protagonists as ideal figures from classical art. In his literary works Ehrensvärd argued that ancient Greeks had led their lives in accordance with human nature and had thereby acquired objectively true taste as displayed in their art. In the drawings discussed in this article Ehrensvärd reveals the discrepancy between his vision of the perfect, masculine, virtuous Greeks, and the allegedly corrupt, feminised Northern Europe of his own time. This conflict is often represented humorously, making use of the abundant iconographic layers of classical art, which could load an image with misogynistic, comic, or heroic overtones. These allusions were expected to be recognised and appreciated by the drawings’ intended audience, Ehrensvärd’s friends, such as the sculptor J. T. Sergel. Ehrensvärd’s view of the empirical truth of human nature, embodied in ancient art, left little room for artistic individuality and subjective choice. Yet, by appropriating the authority of the classical nude, Ehrensvärd could portray himself as an individual in defence of real human potential, as opposed to its modern travesty.

Introduction

Carl August Ehrensvärd (1745-1800) was a Swedish count, an admiral, an intellectual, an architect and illustrator. He was very much a representative of his time: endlessly curious about the world around him and an avid collector of empirical evidence that would fit his idea of a wider scheme of things – an idea that he kept formulating and developing in dialogue with the writings of many of the foremost thinkers of the time.Footnote1 One of the major sources of inspiration for Ehrensvärd's thinking was classical antiquity. It represented for him the only time in the history of humankind when a society had been in tune with nature and people had been able to lead a life based on their basic needs. This vision was based only partly on ancient literature. Like Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), Ehrensvärd approached the greatness of the ancient Greeks and Romans through its visual remains. The ancient works of art and architecture he saw during his Grand Tour in Italy in 1780–1782 provided evidence of the harmonious society that had produced them and showed all too well the pitiful state of both art and society in the cold and spiritless North.

Once back home, Ehrensvärd set his mind to demonstrating this to his compatriots. In 1786, he published his Philosophy of the Free Arts (De fria konsters philosophi), in which he argues that the sense of beauty is a natural human condition and that great art is therefore an outcome of a society that allows its citizens and artists to follow their nature, like the Greeks had done. Swedes should follow their example, even if the harsh Nordic climate was not conducive to achieving a similar success. The same year Journey to Italy, 1780, 1781, 1782 (Resa till Italien, 1780, 1781, 1782) was published. Other ambitious works, such as A New Philosophy (En ny philosophi), from the 1780s, Piecemeal Draft for a Philosophy (Utkast styckevis till en philosophi) and Frontispiece to a Moral and Political Handbook (Frontespice på en moralisk och politisk handbok), from the later 1790s, were not printed during Ehrensvärd’s lifetime. His writings and his wide correspondence have been published posthumously, and they have received a fair amount of scholarly attention, most notably by Holger Frykenstedt.Footnote2

In parallel with his writing, Ehrensvärd used the medium of drawing to represent and develop his ideas. Hundreds of his drawings have been preserved in various collections, most importantly Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum. The drawings are generally in ink on paper, and many of them are highly elaborate pieces, sometimes coloured with aquarelle. Whereas Ehrensvärd’s interest in architecture led to some of his building projects being realised, his practice of drawing seems to have been driven by an urge for visual conceptualisation and communication and he participated in the more public art scene only indirectly.Footnote3 The drawings usually include an inscription clarifying the subject and they were often given to friends, one of the most prominent being the Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel (1740–1814).

A particularly interesting aspect of Ehrensvärd’s pictorial production is his use of ancient imagery – the classical male nude, ancient compositions, poses and settings – to depict contemporary situations within his personal circle of experience. In these drawings characters and coincidences of everyday life are given the same treatment as the themes and protagonists of history painting. Ehrensvärd’s deep knowledge of classical culture enabled him to load many of the images with humorous polyvalence.

In this article I ask, what does ancient art stand for in Ehrensvärd’s drawings of himself and his friends. What is the relationship between the classically idealised human figure and the actual living individuals whose appearances it replaces? How does Ehrensvärd’s use of ancient art relate to sex and gender? I focus on a number of drawings made between 1782 and 1797 that have been selected on the basis of their relevance to these questions. They enlighten various aspects of Ehrensvärd’s appropriation of the ancient ideal and connect the present discussion to its scholarly predecessors.

A significant proportion of Ehrensvärd’s drawings, including most of the ones discussed in this article, have been previously studied by Ulf Cederlöf and Sten Åke Nilsson.Footnote4 Whereas the focus of these studies has been on Ehrensvärd’s life and relationships, the aim of this article is to place the drawings in their wider visual and intellectual framework – especially regarding their use of the classical ideal. I point out connections between the drawings and classical works of art and iconography, but most importantly, I discuss the drawings in relation to Ehrensvärd’s theoretical ideas, something that has been undertaken rather cursorily in previous scholarship.

Ehrensvärd’s aesthetic thinking is connected to a wide selection of earlier and contemporary writers, as amply discussed by Frykenstedt.Footnote5 Winckelmann seems to have played a significant role in the early phase of Ehrensvärd’s initiation into the appreciation of ancient art.Footnote6 However, Ehrensvärd’s anti-idealistic approach constitutes a revealing contrast to Winckelmann’s thinking.Footnote7 By considering Ehrensvärd’s drawings in the light of these conceptual differences and other contextualising texts and images, this article paints a variegated picture of the intellectual framework behind the appropriation of the ancient ideal in Swedish art. It shows how antiquity, and the classical nude, could be used to advocate for collectively determined, objective norms of being and the related aesthetic heteronomy, while also enabling proto-individualistic positions of self-determination, paving the way for a subjectivist approach to art and aesthetic experience.Footnote8 The value of the Greek ideal depended on its association with masculinity, but masculinity did not necessarily correspond to a physiologically determined male sex. Ehrensvärd’s often contradictory communication around the subject is telling of the shift in paradigm regarding sex and gender taking place at the time.

“The highest beauty” on a human level

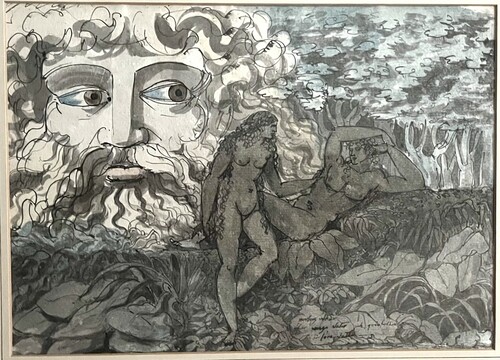

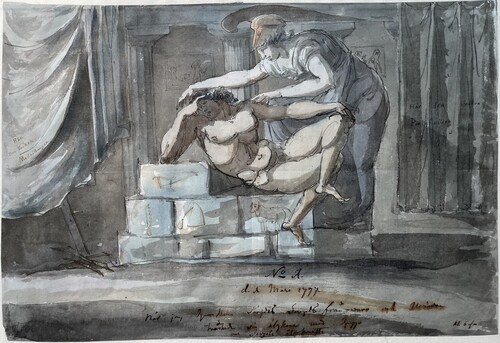

The first drawing in which Ehrensvärd inscribes the names of his friends on a seemingly classical image dates to 1782. It shows the Biblical Fall, Adam and Eve observed by God () and belongs to a group of around 20 drawings representing Christian subjects, probably created in Venice in the Spring of 1782.Footnote9 At the time, Ehrensvärd was returning from the Grand Tour that had brought him to Italy in 1780. During the course of almost two years, spent mostly in Rome and in Naples, he had studied passionately ancient Greek and Roman art and monuments. The Fall and the other Biblical drawings of 1782 represent an attempt to replace traditional Protestant imagery of suffering with what Ehrensvärd now saw as the true visual path to people’s hearts and minds.Footnote10

In the opening chapter of Philosophy of the Free Arts (1786), titled “On the Highest Beauty” (“Om Högsta Skönheten”) Ehrensvärd writes that it is important for people to get a visual shape for God, because the thought of God should arouse both “respect” (“vördnad”) and “pleasure” (“behaget”). In order to have this effect, God should be represented in the form of the most beautiful we know, namely a human figure in its “health/bloom” (“friskhet”).Footnote11 Through beauty we are able to understand nature’s order, since beauty affects “the deepest part of the self” (“det innersta i en sjelf”), which is connected with nature, and follows what appears good for us.Footnote12 Therefore, we also consider beautiful those human works that seem to promise “the fulfilment of the pure needs of man’s healthy nature”.Footnote13 Artists should choose from nature what is beautiful, and those who do this correctly, those who have “the sense of nature’s most secret truths”, have taste.Footnote14 Ancient Greek artists had reached this goal. They had shown “nature as it should be and not as it is” – “noble” (“ädel”) and “health/bloom” (“frisk”) instead of being distorted by nature’s little accidents – and had therefore aroused “a serious and lovable feeling” for it.Footnote15

Ehrensvärd’s words echo Winckelmann’s famous dictum that the essence of the Greek ideal was “a noble simplicity and a calm grandeur” (“eine edle Einfalt und eine stille Grösse”). Like Winckelmann, Sergel and other contemporaries, Ehrensvärd argues that modern artists should not blindly imitate ancient art, but instead try to reach the perspective of the ancients and represent nature as refined by this vision.Footnote16 And yet, the ideal Greek taste had depended on a culture, a society and a climate that had catered to the natural needs of men. Modern Northerners, with their unfavourable circumstances and corrupt habits, were merely trying to find both taste and virtue – the two concepts are significantly equated by Ehrensvärd – with little chance of succeeding.Footnote17

The drawing of The Fall represents Eve and Adam as idealised, sculptural types. The Venus-like, standing Eve leans forward to touch the rib of Adam, who reclines sensually on the ground in a pose adopted from the statue in the Vatican Museums known at the time as Cleopatra (actually Ariadne). Behind the couple is a giant face of a bearded man looking at them out of the corner of his eyes. This is God in person, as made clear by his features of a Hellenistic Zeus. Though more mature than the standard classical nude, Zeus was, according to Ehrensvärd, never depicted as old by the Greeks and his shape thus fitted the health criteria of the highest beauty.Footnote18 The gigantic scale of the head and its immobile presence in the landscape was probably inspired by the pieces of colossal sculpture that Ehrensvärd had seen in Rome.

God observes – and we observe with him – as the humankind he has created in his own image falls from order to disorder. Adam and Eve are still one with Paradise, with the natural state of things. In his Philosophy of the Free Arts, Ehrensvärd writes: “How does beauty work? When the eye gets to see the beautiful, it meets order in nature that sets the matter for the mind in an indescribable way, one feels and understands everything.”Footnote19 In the drawing, Ehrensvärd associates man’s original state in the garden of Eden with the orderly beauty of ancient art, suggesting that we get a glimpse of this paradisiacal state through beauty in art. But for modern viewers, the perfection of ancient art is also a continuous reminder of the loss of this state: we are witnessing the fall into disorder, and, like Adam’s and Eve’s, this fall is our own fall. The face of God could be a reflection of the face of the viewer of the drawing. As it is also reminiscent of a colossal marble head of Zeus, we are vicariously given a pair of ancient Greek eyes through which to witness our own decay.

Despite relying on same beauty standards as Winckelmann and applying them to representations of the divine, Ehrensvärd did not see ancient art’s ideal bodies as a Platonic stepping stone for the viewer’s mind to rise towards the Idea of Beauty, but instead as a demonstration of the concrete physical perfection reached by nature when rightly understood and nurtured.Footnote20 That this perfection is associated with religious subjects is merely a way to engage people with subjects they were familiar with and ready to absorb.Footnote21 Ehrensvärd bitterly resents the Christian religion for its alleged neglect of the actual reality in favour of an imagined one.Footnote22 In his mind, there was no metaphysical law, no immaterial Idea, behind beauty; just characteristics and proportions best suited to fulfil people’s pure natural needs, and therefore considered instinctively desirable.

It might have been his aversion to both Platonic and Christian idealism that made Ehrensvärd turn the classical-Biblical subject of The Fall into a humorously erotic scene that was played out within his immediate social circle. An inscription beneath Adam and Eve, which is written more like an afterthought on a suitable spot than a planned element of the image, states “Norberg watches over the young Suther and womankind seducing Suther”.Footnote23 Ehrensvärd was accompanied on his journey from Rome by the Swedish court preacher Anders Norberg (1748–1820) and “the young Suther”, son of the court jeweller Per Suther (1719–1789). The inscription seems to be an insider joke between fellow-travellers, but it also makes evident that Ehrensvärd wants to communicate with his contemporaries and speak to their concrete reality through the example provided by ancient art.

Mankind and “woman”

The drawing of The Fall, with its allusion to the contemporary reality provides a window to Ehrensvärd’s ideas regarding sex and gender. The insiders of the joke are three men, two of whom – Ehrensvärd and Norberg – were intellectuals, moral preachers, and one of whom – “the young Suther” – is seen as an object of moral concern, but also of erotically tinged admiration. Although “womankind” (“qvinfolken”) in the shape of Eve-Venus is likewise a desirable object for the drawing’s implicit male voyeurs, she is treated as a collective Other, whose corruption of a male individual stands for her corrupting influence on the whole of mankind, making her the rightful culprit of Original Sin.

In his literary works, particularly his correspondence from the year 1782, Ehrensvärd does not pull any punches in accusing women.Footnote24 According to him, the feminisation of values – together with commercialisation and the practice of the Christian religion – was the main reason for the current cultural degradation. Ancient Greeks did not have this problem, since they kept their women inside their homes, where their influence, under the natural order, was beneficial. Yet, in his Philosophy of the Free Arts, Ehrensvärd states that it is right to depict the divine with either male or female gender marks since “one sex ("kön") is not better than the other”.Footnote25 These apparent inconsistencies in Ehrensvärd’s views on women have been associated with his happy marriage, which took place in 1785.Footnote26 A more appropriate way to understand them is to think of the conceptual frameworks of sex and gender that were available to him at the time.

In the spirit of Judith Butler’s thinking, I consider both sex and gender as ultimately indistinguishable from the discourses that claim to describe them.Footnote27 The Swedish word “kön”, used by Ehrensvärd, makes no difference between “sex” and “gender,” and from here on, I use the combined concept of sex-gender in order to avoid the impression that there might be something immutable, obvious, and ahistorical “behind” the studied discourses. Butler sees sex-gender as performative: it is internalised through a constant repetition of discursively produced and maintained norms, which enables the subject to remain socially, culturally, and physiologically recognisable. Even according to Ehrensvärd, people as moral beings were greatly affected by their surrounding environments, but beneath the surface there existed some sort of order of nature, which culture and society should respect.Footnote28 This order is as much a discursive construction as the modern norm of biological sex analysed by Butler. It is discussed visually in the drawing of The Fall, which shows a state of unity between a beautiful man, a beautiful woman, and the landscape flowing from the beautiful image of God. Yet, the corrupting element of femininity is noticeably present. Eve, or “womankind”, is actively approaching, “seducing”, Adam. He has the masculine body of the ancient male ideal, but he is reclining in a languid pose adopted from a famous statue of a sleeping woman. The couple are under the moral surveillance of the unquestionably masculine Zeus-like God.

The conception of sex-gender prevalent in Europe since antiquity regarded the physical body not as the absolute origin of a person’s sex-gender, but as illustrative of a predetermined idea of a “natural” order of things where the standard and normative ideal of human being was manhood and masculinity. Womanhood and femininity, even when apparently observed from the flesh, was derived from this standard as its deformation or its negative. This conception is called by Thomas Laqueur “one-sex/flesh model”.Footnote29 It began to be seriously challenged in the eighteenth century by the idea of two physiologically different sexes with fundamentally distinct prerequisites.Footnote30 Ehrensvärd’s thinking reflects this ongoing change. He is eager to claim that people are “entirely built on Physique,”Footnote31 but the nature of this physical being is mostly anchored in philosophical discourse, and it is seldom clear whether it represents one norm for all, or two distinct “male” and “female” natures.

For instance, in his passionate letters to his newly-wedded wife Sophie Sparre, or “Kickan” (1761–1833), Ehrensvärd writes that she does not “know her sex-gender”, but is on a higher grade, and that she is “full of virtue” and “so perfect in her nature” when thinking of being in the right, that she acquires “a certain height/greatness mixed with a sort of manly will”.Footnote32 Ehrensvärd’s cousin, countess Jeanette von Törne (1748–1803), is praised in his letters for her “genius 500 years in advance of all our centuries”.Footnote33 Modern men, on the other hand, could be characterised by Ehrensvärd as much like the frivolous women allegedly dominating them.Footnote34

Even when Ehrensvärd seems to be constructing an essentialising binary, in practice it provides only one liveable subject position. In his Piecemeal Draft for a Philosophy (late 1790s), Ehrensvärd writes that “modesty” (“blygsamhet”) is part of woman’s physique and “rather a necessity than a virtue” (“snarare [..] ett behov än en dygd”).Footnote35 What would be women’s virtues is left undiscussed, since “woman” is here a negative of whatever is considered ideal in a human being. Her positive attributes – the ability to give birth, modesty, prettiness – are merely aspects of her physical condition.Footnote36 In a letter to Sergel from 1797, Ehrensvärd presents an opposite characterisation of the female body. He writes that the outer appearances of men and women should be understood in non-binary terms, since “actually Apollo is more beautiful than Venus” and a statue of Venus could be made to look great, terrible, and much stronger than Hercules. He sees this view as opposed to that of Kant, who equates beauty (“skjönheten”) categorically with the female figure and the sublime (“det höga”) with the male figure. For Ehrensvärd, the two concepts cannot be separated from each other, and beauty is “a way, not a thing”.Footnote37

Yet, based on The Fall, the shape of Venus does not seem to imply for Ehrensvärd such unconditional ethical greatness as the classical male nude. Whereas the Greek utopia of Ehrensvärd’s drawings made men look like Apollo or Achilles, the only actual woman involved, his wife Sophie, is depicted as Minerva, the fully dressed virgin goddess of wisdom (sophía in Greek) and war. Instead of a Venus, Ehrensvärd’s ideal woman is a de-sexualized emblem of masculine virtue – physical beauty intertwined with an unmistakably respectable way of behaving. Since Sophie-Minerva usually just accompanies her husband, who is the protagonist in the drawings (see below), her exemplary role remains rather static compared to the corrupting activity of the Eve-Venus of The Fall.

Consequently, I suggest that the potential of viewers’ identification in Ehrensvärd’s drawings was not necessarily tied to the apparent sex-gender of the represented figures. Late-eighteenth-century viewers might have disregarded a figure’s sex-gender and related instead to the character and behaviour they were witnessing according to its desirability and acceptability or shamefulness within the relevant normative framework. The Swedish male poet Johan Henric Kellgren (1751–1795) could identify with Psyche in his panegyric (1780) of Sergel’s sculpture representing the girl at the feet of Cupid.Footnote38 Winckelmann had famously adopted the position of a mourning female lover, like Ariadne or Dido in a Pompeian painting, in his metaphor of a historian’s work.Footnote39 The female intellectual Françoise Marguerite Janiçon (1711–1789) had published criticism of women and society’s feminisation parallel to Ehrensvärd’s in Swedish (1767), and in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) pushes women to identify with “manly virtues” since these are, in her mind, the only virtues that ennoble the human character instead of debasing it.Footnote40 Within this normative framework of sex-gender, the threat of “womankind” as represented in The Fall could have been felt by any person aspiring to realise themself as a fully formed person.

Ironic elevations

The mundane significance of Ehrensvärd’s drawing of The Fall seems like an afterthought, a postscript that changes the mode of the image to an ironic one: what would have been God in the shape of an ancient Zeus has become an old moralist, a hypocritical peeping Tom. What would have been a fatal touch between the first human couple has become an average day in the life of a sexually curious youngster on holiday. Ehrensvärd seems to have liked the effect. From the mid-1780s onward he produced dozens of drawings that by their appearance could be classically idealised illustrations of ancient poetry, but which have been inscribed with captions clarifying them as representations of his friends and himself going about their daily lives. The images are clearly created with this dualism in mind. What was Ehrensvärd pursuing in using this mode?

For Ehrensvärd, the sense of beauty depended on utilitarian premises: a healthy and functional body is perceived as desirable because people’s natural impulses tell them that this form best meets their pure basic needs. Following the maxim mens sana in corpore sano, Ehrensvärd claims that such a beautiful appearance was also the outer reflection of equally healthy, functional, and harmonious inner organs.Footnote41 Yet, this maxim depended on a culture’s and society’s ability to enable a life where people could follow their natural instincts. For Ehrensvärd, the Sweden of his time was not such a place. Consequently, even those whom Ehrensvärd admired the most (we might include himself in this group) did not look like ancient sculptures. By drawing them in the shape of ancient heroes and deities Ehrensvärd fantasised about the world as it should be, about how people would look if they were born in ancient Greece. In A New Philosophy (1780s) Ehrensvärd imagines himself in the “ancient South” (“antiqwa tiden i Söder”) among people who were like ancient works of art, both inside and outside.Footnote42

Such idealisation might also be interpreted as an exhortation for the viewers of the drawings to recognise their human potential. According to the prominent art theories of the time, the model of ancient art and poetry should encourage their audience to identify with the virtues embodied by the ancient heroes and their ideal bodies.Footnote43 In 1772, the Swedish intellectual Jacob Jonas Björnståhl (1731–1779) wrote of Sergel’s sculpture of Diomedes in Rome, that it “inspires courage and heroism”.Footnote44 Ehrensvärd himself argues that artists should represent ancestral virtues for the benefit of the public.Footnote45

Yet, the discrepancy between the classical nude and the actual shape of the men Ehrensvärd associated with it, included strong humorous potential. A couple of drawings from around the mid-1780s provide a good example of Ehrensvärd’s deliberate balancing act between the serious and the almost cruelly ironic. At the time, Ehrensvärd was serving as the chief admiral of Sweden’s fleet in Karlskrona and seems to have found a kindred artistic spirit in the figurehead sculptor Johan Törnström (1744–1828).Footnote46 In a finely executed drawing, Ehrensvärd represents Törnström as a handsome nude youth on top of a winged wheel between the graceful figures of two ancient female figures (). The textual description of the drawing, discovered by Cederlöf, reveals that it depicts Törnström about to go on foot to Italy – despite his lamentations of having so little money – escorted by the personifications of “happiness” (Fortuna) and “free arts”. Other symbols present are Minerva’s owl and the horn of plenty.Footnote47

Fig. 2. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Törnström goes to Italy, 1780s, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH A 77/1973. Photo: author.

The drawing itself seems to be encouraging Törnström to dream of undertaking formal training in sculpture in Italy. The tone is celebratory, but the text’s recognition of Törnström’s social disadvantages, which would have made the suggested prospect highly unlikely, also points to the social gap between Ehrensvärd and his subject. The admiral-count imagines here an alternative future for one of his subordinates, and makes it exaggeratedly elevated, incredible, against the realism represented by Törnström’s protesting voice in the written description.

Another drawing of Törnström reveals Ehrensvärd’s upper class perspective even more clearly (). It represents what looks like a lunette below a star-studded vault. In the middle of the semicircular space, a winged Victory pours nectar into a cup held by a figure in a Graecizing dress with a lyre on his back. The figure’s face, with its toothy grin, is made to look like a comic mask from the Greek theatre. The pair are framed by two groups of naked or half-naked women. Below the lunette hangs a valance, on which is written in Greek, but with Swedish spelling: Törnström’s apotheosis.

Fig. 3. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Törnström's apotheosis, 1780s, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH Z 228/1957. Photo: author.

The scene is a parody of a famous Greek vase-painting, known at the time as “the apotheosis of Homer”.Footnote48 The juxtaposition of Törnström and Homer, and the suggestion that the figurehead sculptor would be received as one of the gods, seems ridiculous enough, but Ehrensvärd spoon-feeds the parody to the viewers by replacing the heroic youth of the previous drawing with a comic caricature. The grotesque features of the comic mask were probably a way of accentuating the gap between the idealised beauty of the ancient Greeks in their perfect world and the actual reality – and looks – of a Swedish craftsman. Yet, by exaggerating Törnström’s rough features in the manner of Greek comedy and comic art, Ehrensvärd has also found a way of staying within the impersonal classical mode, while marking the figure as other than classically beautiful. Rather than a modern individual, Törnström becomes a standard type from ancient theatre.

It is impossible to know how heartily Törnström himself laughed at Ehrensvärd’s humour. A third drawing showing Törnström as a grotesque caricature with the legend “But Törnström smiles at the whole world”, suggests that Ehrensvärd might have been inspired by Törnström’s own world-view.Footnote49 Moreover, servant characters in ancient comedy and their derivatives on the modern stage could be grotesquely ridiculous and still able to manipulate their superiors to their own advantage. Törnström’s apotheosis could represent the carnivalesque culmination of such a cunning career – or, more simply, the crowning of a good-natured king of fools.

However, the fact that Törnström’s apotheosis is drawn as if it was a copy of a wall-painting indicates that the point of Ehrensvärd’s parody was targeted towards the tendencies of the art of his time. In the Spring of 1782, Ehrensvärd had complained in a letter that the prevailing taste in art leads painters to produce paintings of “Jupiter, Mars, Apollo, Venus, Minerva and Juno in the shape of naked actors on an uncleaned theatre-stage”.Footnote50 Towards the end of the 1780s, Ehrensvärd was also growing more and more critical of Gustav III and drew a bitter caricature of the king and his desire to be assimilated with Apollo.Footnote51 Perhaps the figure of Törnström was used by Ehrensvärd to criticise mortals with ambitions to be elevated among the Greek gods despite their poor merit, even when compared to a humble craftsman. In Ehrensvärd’s view of the corrupt contemporary world, identification with the virtues represented by ancient art was usually doomed to be superficial and ridiculous.

The creative individual and objectively right taste

During the latter half of the 1790s, Ehrensvärd reconnected with his old friend J. T. Sergel. Their contact burgeoned into a mutually inspiring interchange of visual ideas, motifs, and artistic impulses. The drawings of the two men from this period provide fascinating opportunities to compare their approaches. One of the surfacing tensions is yet again between idealism and empiricism, which now becomes more personal, since what is at stake is the existence of a human spirit or soul. A related tension arises between individual creativity and the objective standard of beauty represented by ancient art.

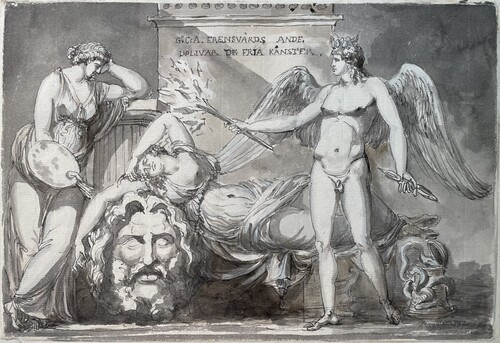

Sergel visited Ehrensvärd's estate of Dömestorp in November 1796, and again from January to March 1797. There, he made a group of carefully finished drawings representing his flattering view of the influence of Ehrensvärd’s “genius” on Sergel’s own spirit.Footnote52 One of the drawings titled Count C. A. Ehrensvärd’s spirit enlivens the free arts (G[re]v[e] C. A. Ehrensvärds ande uplivar de fria kånster) shows a nude winged youth crowned with a pair of eyeglasses and holding a burning torch: Ehrensvärd’s spirit in the shape of a famous ancient sculpture known as Genius Borghese (). The youth approaches two drowsy female figures who are depicted in classical poses. These are the personifications of “the free arts” reanimated by Ehrensvärd. In another drawing titled Genius and Virtue meet in Dömestorp (Geni och dygd möter på Dömelstorp), the same winged youth with eyeglasses greets a corpulent but muscular figure identified as Sergel, the sculptor, through the Belvedere torso at his feet. Behind the youth stands Minerva, the embodiment of virtue, whom both Sergel and Ehrensvärd habitually used as a stand-in for Ehrensvärd’s wife Sophie.Footnote53

Fig. 4. Sergel, J. T., Count C. A. Ehrensvärd’s spirit enlivens the free arts, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH 849/1875. Photo: author.

The idea of “genius”, prominent in Sergel’s drawings and letters, was common currency in popular discourse on human nature in the eighteenth-century. L’Encyclopédie defines it as “the expansiveness of the intellect, the force of imagination and the activity of the soul” and describes it as if it was an animated entity itself, perhaps something like the good horse in front of Plato’s metaphorical chariot of the soul (Phaedrus 253c–254e).Footnote54 The President of Sweden’s Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, överintendent Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz (1716–1796) wrote in a parallel manner in 1789 that “genie” was “the light of innate understanding” which “directs soul with manifold images and high thoughts”.Footnote55 Sergel’s allegories of Ehrensvärd recall Plato’s tale of the encounter between the philosopher’s soul and the Forms (Phaedrus 249b–e). However, whereas Plato’s Forms enlighten the soul, in Sergel’s vision it is the genius of Ehrensvärd who awakes the ancient Ideas from their current slumber.Footnote56

Ehrensvärd shied away from this level of idealism. In his Philosophy of the Free Arts, he writes that genius “is the overflow of capacities to some height above the general public” and discusses it together with taste, which can follow only if these higher capacities are perfectly balanced, in the correct proportion to one other.Footnote57 For him, these capacities were merely the outcome of our natural needs that have refined our organs. In a letter to Sergel from July 1797, Ehrensvärd states: “What we call Soul in an Organic Animal is nothing else than the Sound in a Bell, when the bell is cracked, it sounds bad. This movement-feeling in an organic body we like to define as the soul’s struggle and toil.”Footnote58 In other words, mental issues are a physical affair.Footnote59 Genius, spirit, soul, or whatever names we might give to the workings of the mind, are comparable to the sound of a bell.

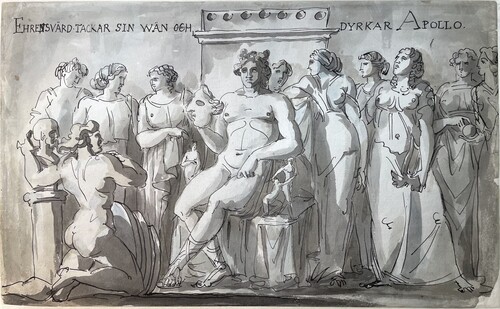

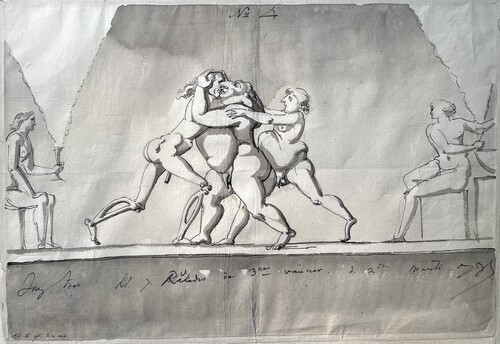

This conviction is tied to Ehrensvärd’s anti-individualistic attitude, as demonstrated by a drawing () that is a response to yet another panegyrical drawing by Sergel. Sergel’s drawing was titled Dömestorp’s Apollo worshipped by the free arts (Dömelstorpska Apollo dyrkas af de fria kånster) and had represented Ehrensvärd in the shape of Apollo, surrounded by the familiar female personifications of “the free arts”.Footnote60 Ehrensvärd exchanges compliments by representing Sergel as Apollo surrounded by the Muses. An idealised male figure has knelt in front of the god. The accompanying inscription explains that this is Ehrensvärd thanking his friend and worshipping Apollo (Ehrensvärd tackar sin wän och dyrkar Apollo).

Fig. 5. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Ehrensvärd thanking his friend and worshipping Apollo, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH A 69/1973. Photo: author.

The details of Ehrensvärd’s drawing are telling of his point of view. Apollo is sitting on a throne, that has armrests made from two of Sergel’s sculptures, Venus rising from the sea (ca. 1772) and Cupid and Psyche (model 1770, marble 1787). In his hand he holds a theatrical mask which bears the facial features of Sergel. This can be interpreted as a claim that Sergel, the individual and artist, was merely a surface under which one could find the harmony of ancient art, represented by Apollo and the Muses. In other words, Sergel had achieved what was the goal set for contemporary artists by both Ehrensvärd and the sculptor himself: he was able to channel the ancient way of looking at and representing nature.

The kneeling man, Ehrensvärd’s alter ego, has no personal attributes. He places his arm around a bust of a male figure and he is gesturing towards it with his mouth open, as if drawing the attention of the god to this figure. The bust has the distinctive shape of Roman portrait busts and its bald head and facial features are reminiscent of Roman portraits such as the so-called Scipio from Herculaneum, or the many portraits of individuals with features emulating those of Julius Caesar. Sergel had made a marble copy of one such bust, using it as a model for an early portrait of his father (1759).Footnote61 The way in which Ehrensvärd’s alter ego holds the bust brings to mind the famous sculpture known as the Togatus Barberini, which represents a Roman patrician carrying the busts of his two ancestors. Through these associations the drawing evokes the thought of dignified ancestors and ancient virtues. Ehrensvärd seems to declare that it is the ancient Greeks and Romans who should be thanked for whatever glory the world is trying to give to his person. It is the ancient wisdom that is voiced through Ehrensvärd – just as it is Apollo, the personification of ancient art, who is acting through Sergel in his best works.

These are momentous claims, since they deprive modern individuals of much of the creative merit for their great works of art or scholarship. Winckelmann had described the viewer’s position in front of the greatness of the Apollo Belvedere as similarly self-obliterating: “The god enters and gains possession of the spectator and makes him its mouthpiece,” to use Alex Pott’s summary of the passage in Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764).Footnote62 Winckelmann assimilates his viewer with the maker of the image and associates both with Pygmalion. Thereby even the artist is transformed from a creative individual into a device in the hands of a higher power.Footnote63 It is noteworthy that in Ehrensvärd’s drawing, it is Apollo the universal god who wears Sergel’s mask, not Sergel the individual who is wearing a mask of Apollo – individual brilliance is revealed as a masquerade hiding the objective truth. Ehrensvärd’s Apollo is a metaphor for true taste based on nature, not Winckelmann’s mystical divine force. But the outcome is parallel: the negation of subjectivity.

In A New Philosophy, written in the 1780s, Ehrensvärd blames modern artists for their subjectivism, which has made them lose the absolute taste and give in to mere genius. Art produced with such “actor’s manners” (“skådespelarens åthäfwor”) denies those frames within which understanding and taste held the arts during the ancient times and destroys all probability of beauty.Footnote64 In contrast, ancient artists so consistently represent the only true taste, that all ancient works of art look as if they came from the hand of a single master.Footnote65 Ancient art provides us with an objective standard of beauty and taste, while individual creativity, or genius, is merely an impulse which gives an artistic form to the standard.

Bacchic hedonism or epic heroism?

What was the ancient utopia that Ehrensvärd imagined for himself and his friends? Two series of drawings created by Ehrensvärd in 1797 propose opposing visions. In the first series, a set of illustrations of a drinking song called On Life’s Arduous Path (På lifvets mödosamma stråt) Ehrensvärd takes a carnivalesque stance and prescribes Bacchic hedonism as a medicine for the frustration of the representatives of true taste within modern corrupt society. The second series of drawings represents Sergel’s final departure from Dömestorp to Copenhagen and paints the utopia with heroic tones, while mocking the modern indulgence in effeminising physical pleasures.

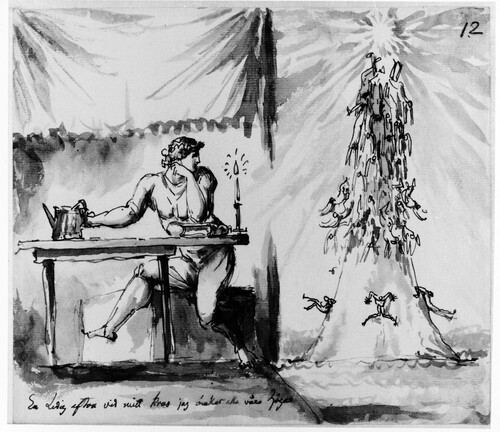

Ehrensvärd and Sergel decided to illustrate On Life’s Arduous Path together, verse by verse, while in Dömestorp. Both artists made their own versions, though clearly under one another's influence.Footnote66 Ehrensvärd's drawings represent a male individual, mostly in the form of an ancient hero, who goes through the hardships of life, associated with the normative pressures of contemporary society, and who decides to take his own path and focus on the pleasures of life: wine, women and friendship ().

Fig. 6. Ehrensvärd, C. A., On Life's Arduous Path -series, no. 12: “En ledig afton vid mitt krus / Jag ömkar alla våra höga”, Nationalmuseum. Photo: Nationalmuseum.

The idea of pleasure achieved through the abandonment of empty modern ambitions aligns to some extent with Ehrensvärd’s serious philosophical thinking, according to which man’s ideal natural state consisted of the fulfilling of the pure needs of a healthy body. In a letter from 1795, Ehrensvärd writes that “pleasure” (“njutning”) is the outcome of this pursuit, the consequence of freedom from the slavery of constant need.Footnote67 This idea is influenced by ancient Stoic philosophy, as discussed by Frykenstedt.Footnote68 It would even accord with the original ideas of Epicurean thinking, focused as it is on a rational distinction between “empty” desires and “natural” ones, were it not for Ehrensvärd’s assertion that pleasure is not the goal in itself, but just a side-effect of the freedom from needs.Footnote69 With this disclaimer he seems to distance himself from Epicureanism, a simplistic sketch of which he criticises in his Piecemeal Draft for a Philosophy (late-1790s).Footnote70 Paradoxically, Ehrensvärd’s criticism is targeted precisely on the type of hedonistic over-indulgence promoted in the drawings for On Life’s Arduous Path.

Rather than conveying original Epicurean ideas, these drawings follow a more popular type of ancient maxim and its derivatives in the Swedish poetry of the latter half of the eighteenth century.Footnote71 A poem by J. H. Kellgren, first printed in 1796, associates the maxim with the Greek lyric poet Anacreon (sixth century BCE), whose style of love poems and drinking songs were widely popular in Europe at the time.Footnote72 Therefore, by embracing the maxim in their drawings, Ehrensvärd and Sergel allied their protagonist with a firm tradition in both ancient and contemporary art. The estranged individual from the beginning of the series On Life’s Arduous Path turns out to be the representative of a merry collective, the follower of an objective doctrine. This illustration-project offered Ehrensvärd a welcome opportunity to show how irreconcilable the ancient, natural state of being was with the follies of the modern world. The over-indulgence celebrated in the drawings is represented as an understandable reaction to the hopeless conflict between the recognised truth and the impossibility of living up to it.

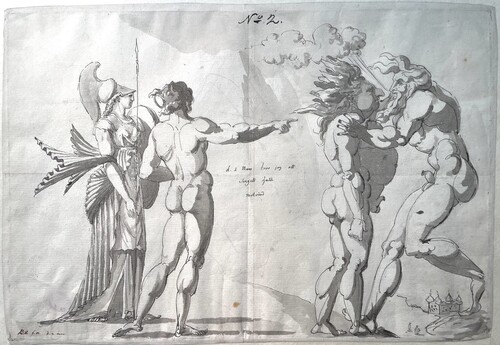

In the drawings representing Ehrensvärd’s view on Sergel’s final departure from Dömestorp on 1 March 1797, the figure of Sergel takes the path from Dömestorp’s Olympus to the corrupt Copenhagen and undergoes a corresponding physical transformation from ancient perfection to modern degeneration.Footnote73 The first plate of the series is carefully finished and coloured with aquarelle (). It shows Ehrensvärd’s sorrow following Sergel’s leave-taking: Minerva (Sophie Ehrensvärd) consoles “her lover”, a beautiful naked youth, reclining on a pile of stone blocks in a clearly Michelangelesque pose. The couple depicted refers to the late-eighteenth century discourse about suffering heroes and the sympathy they arouse.Footnote74 Indeed, on the wall behind the youth and his consoler can be seen two drawings on the life of Achilles, by Sergel. The one to the right shows the hero mourning by the side of Patroclus’s death bed – a clear parallel to Ehrensvärd’s sorrow.Footnote75 The one to the left shows Achilles taking up arms and rejecting his feminine guise as one of king Lycomede’s daughters in favour of the masculine destiny of a hero of the Trojan war.Footnote76 A text written on the curtain to the left indicates that behind it stands Sergel’s “beautiful” portrait relief of Sophie Ehrensvärd.Footnote77 The whole setting pictures Dömestorp as an ancient haven that had nourished Sergel’s artistic output.

Fig. 7. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Ehrensvärd mourning Sergel's departure to Copenhagen, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH A 66/1973. Photo: author.

The second plate in the series includes Ehrensvärd again, this time in the shape of a Homeric hero (now crowned with the emblematic eyeglasses) and the figure of Minerva (). The couple are watching, as a naked Zeus-like figure blows into the face of a muscular, though barrel-bellied male figure bearing Sergel’s profile. According to the accompanying inscription, it is an adverse wind: it is as if divine forces wanted to keep Sergel in Dömestorp’s Olympus. All the male figures in the composition have extraordinarily distinguished musculature, even by the standards of Ehrensvärd’s heroes. Moreover, Sergel and the wind god have their classically modest penises pointing upwards, as if markers of their decent masculine vigour.

Fig. 8. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Sergel had an adverse wind, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH Z 306/1957. Photo: author.

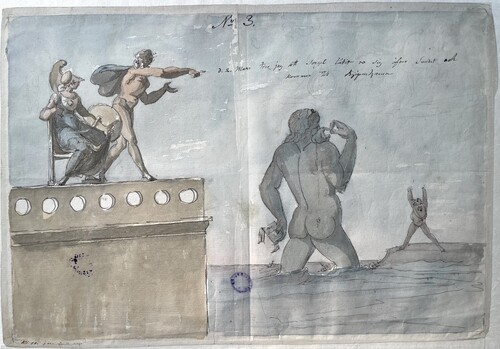

In the third plate of the series, St. Christopher, a representative of the despised Christian religion, has taken Sergel on his shoulder and carries him across the strait to Copenhagen (). Sergel has been turned into a tiny, wide-assed creature with a long beak who is suffering from diarrhoea. On the opposite shore a big-bellied birdman dressed in contemporary clothes decorated with honours is waving enthusiastically. This is baron Jean Jacques De Geer (1737–1809), whom Sergel was supposed to meet in Copenhagen.

Fig. 9. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Sergel crossing the strait to Denmark, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH A 65/1973. Photo: author.

The fourth and final drawing of the series shows Ehrensvärd’s vision of Sergel’s arrival in Copenhagen, where he is greeted by De Geer and the Danish painter N. Abildgaard (1743–1809) (). The way that the three naked men are presented is a far cry from the heroic: Sergel and De Geer have bellies so large that it makes it difficult for them to hug, while Abildgaard is so thin and spindly that his calves are altogether skeletal. All three of them have penises that are pointing towards the ground. The scene is flanked by two nude female figures holding glasses and a punch bowl, as if emblems of the life awaiting Sergel in Copenhagen. The reunion is a reversal of Achilles’s welcoming of his masculine destiny while at the court of King Lycomedes: Sergel has turned his back on his comrade-in-arms Ehrensvärd and embraces the pleasures of the corrupt, effeminising Copenhagen.

Fig. 10. Ehrensvärd, C. A., Sergel meets Abildgaard and De Geer in Copenhagen, 1797, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, inv. no. NMH Z 307/1957. Photo: author.

The way in which Ehrensvärd frames antiquity as the seat of objective truth, a truth that is absent in the erroneous world we live in and thus longed for by the few who are in the know, comes close to the way that Winckelmann pictures the relationship between the modern individual and antiquity. For his own personal reasons, namely his dependent social status and his sexual and romantic feelings for men, Winckelmann was an advocate of individual rights and freedom in his contemporary world.Footnote78 He used antiquity and ancient art as authoritative sources of a righteous way of being and seeing that the modern world had forgotten, thus justifying the desires he felt so keenly in the present moment. For Ehrensvärd, matters were not so pressing, as he could lead the life of a married nobleman according to the norms of the modern “corrupt” society relatively comfortably. Consequently, he could afford to have more utopian views and advocate a collective, anti-individualistic appropriation of the objectively right way of being represented by the ancient Greeks, bypassing the need of individual rights in the present.

Conclusions

In his Philosophy of the Free Arts Ehrensvärd writes that ancient art, even a sketch of a Greek vase-maker, always presents for the eye the important, the fully formed, and composes “to one great purpose such things as man’s expressed action-guiding functions, always displayed within the class of the serious, the noble or the healthy/blooming”.Footnote79 This disposition is crystallised in the word “fullkomlig”, which means “perfect”, and comprises a sense of fullness, of being complete. God should be represented as human figure in its “health/bloom” (“friskhet”), further defined as “nature in its perfection” (“all natur i sin fullkomlighet”). “What is beautiful?”, Ehrensvärd asks and replies: “The perfection” (“det fullkomliga”).Footnote80 This perfection is an amalgam of external and internal qualities. A human being, whose capacities are “on a high level” and rightly balanced, someone with both taste and genius, is hailed as “fullkomlig”.Footnote81

Ehrensvärd’s drawings visualise and discuss this fantasy of a “fullkomlig” man – a human being as perfect and whole as those ancient men whose minds and bodies classical sculpture supposedly reflected. Alex Potts writes about “the Enlightenment fantasy of a self-sufficient oneness of being that would be embodied in a single model of the human subject.”Footnote82 Winckelmann’s discussion of ancient Greek art constituted the classical male nude as the utopian image of this sovereign subject, even as his words paradoxically divested it of traces of individuality and, ultimately, subjectivity.Footnote83 For Ehrensvärd the objectivity and impersonality of the classical ideal was proof of its supremacy compared to the incoherent plurality of the modern world and its less-than-beautiful works of art and people. Greek perfection corresponded to the order of nature, promising in its shape the concrete fulfilment of people’s “pure,” physical needs. It was therefore not just an abstract idea, but empirically true.

This objectively perfect, collectively applicable standard could not help but be in contrast with the reality of the imperfect modern characters that Ehrensvärd placed within his Greek utopia. The drawings discussed in this article use this discrepancy dynamically to underline the gap between what is and what ought to be. They employ the iconographic heritage of classical art to create hyperbolic associations and apparent correspondences that seem to attempt to bridge the gap but are usually too far-fetched to be taken seriously.

Nevertheless, Ehrensvärd’s representations of himself and those closest to him as perfect in the Greek manner were clearly intended to reinforce their identity and self-respect against the surrounding mainstream society. By anchoring the truth of himself in classical form, Ehrensvärd also appropriated its aura of masculinity and virtue. Although constructed through a forceful rejection of femininity and “woman”, this conception owed much to the ancient framework of sex-gender that saw masculinity and manhood as the standard and femininity and “woman” as the peril for all mankind.

Whereas Winckelmann used the authority of antiquity to promote the individual freedom of the sovereign subject, Ehrensvärd claims that free will was an illusion: people merely followed their needs in whatever seemed the easiest way to fulfil them. And yet, within their contemporary conditions, people like Ehrensvärd were forced actively to choose the ancient way over the modern one. Ehrensvärd’s drawings advocated this choice, and thus implicitly participated in the ongoing construction of the modern subjective-individualistic notion of the self.Footnote84 His adoption of the classical body to represent not only the commonly shared ideal, but even his “true” self, renders his drawings early precursors of the twenty-first-century’s gym selfies. The deconstruction of this bodily utopia and its historical trajectory up to today’s norm of flesh and blood is a pressing task for interdisciplinary scholarship, including art historical study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Mostly French philosophers. See Holger Frykenstedt, Studier i Carl August Ehrensvärds författarskap, Stockholm, 1965, pp. 187–362.

2 For Ehrensvärd’s writings I use the standard editions Gunhild Bergh, ed., C. A. Ehrensvärds brev I, Stockholm, 1916; Gunhild Bergh, ed., C. A. Ehrensvärds brev II, Stockholm, 1917; Gunhild Bergh, ed., Skrifter av Carl August Ehrensvärd I, Stockholm, 1923; Gunhild Bergh, ed., Skrifter av Carl August Ehrensvärd II, Stockholm, 1925; Carl David Moselius, ed., Louis Masreliez’ och Carl August Ehrensvärds brevväxling, Stockholm, 1934; Holger Frykenstedt and Sven G. Hansson, eds., Brev till Kickan, Stockholm, 1971. All the translations from Swedish to English are mine. For studies on Ehrensvärd’s writings, see eg. Frykenstedt, 1965 (with a convenient English summary); Holger Frykenstedt, Poetens historia: Carl August Ehrensvärd och Johan Gabriel Oxenstierna, Konstellation i vänskapens och poesins tecken, Stockholm, 1969; Holger Frykenstedt, “Två moralpolitiska serier av C. A. Ehrensvärd,” Historiska och litteraturhistoriska studier, 1977, pp. 197–244; Ragnar Josephson, Den svenska smaken: konstkritik och konsteori från barock till romantik, Lund, 1997, pp. 165–182; Moselius, 1934, pp. 7–40. For Ehrensvärd’s life, see also Ragnar Josephson, Carl August Ehrensvärd, Stockholm, 1963.

3 For Ehrensvärd as an architect, see Sten Åke Nilsson, “Ehrensvärd – arkitekten”, Carl August Ehrensvärd 1745–1800, tecknaren och arkitekten, U. Cederlöf, S. Å. Nilsson and O. Granath, eds., Stockholm, 1997, pp. xxx–yyy; Hedvig Mårdh, “Templet i Mälby”, Sjuttonhundratal, 2012, pp. 110–129.

4 Ulf Cederlöf, “Ehrensvärd – tecknaren”, Carl August Ehrensvärd 1745–1800, tecknaren och arkitekten, U. Cederlöf, S. Å. Nilsson and O. Granath, eds., Stockholm, 1997, pp. 10–230; Ulf Cederlöf, “1700-talets erotiska fantasier”, Lust & Last, U. Cederlöf and I. Lindell, eds., Stockholm, 2011, pp. 129–172; Sten Åke Nilsson, 1700-talets ansikte: Carl August Ehrensvärd, Stockholm, 1996. For Ehrensvärd’s drawings, see also Holger Frykenstedt, Idé och verklighet i C.A Ehrensvärds karikatyrer, Stockholm, 1974; Pontus Grate, “Bildkonsten”, Signums svenska konsthistoria 8, den gustavianska konsten, G. Alm, ed., Lund, 1998, pp. 195–296.

5 Frykenstedt, 1965.

6 See Bergh, 1916, p. 60; Moselius, 1934, pp. 11–40; Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 189–192.

7 See Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 189–192.

8 For aesthetic heteronomy, see Karl Axelsson, Camilla Flodin, and Mattias Pirholt, eds., Beyond Autonomy in Eighteenth-Century British and German Aesthetics, New York, 2021.

9 See Cederlöf, 1997, pp. 99–105; Ulf Cederlöf, Sten Åke Nilsson and Olle Granath, Carl August Ehrensvärd 1745–1800, tecknaren och arkitekten, Stockholm, 1997, cat. 83–93.

10 In his writings from the 1780s Ehrensvärd repeatedly complains about the squalor of Christian art. See eg. Moselius, 1934, p. 102; Bergh, 1923, p. 168.

11 Bergh, 1923, pp. 207–210.

12 Bergh, 1923, pp. 213.

13 “Fyllnad för de rena behofven i menniskans friska natur”. Bergh, 1923, p. 215.

14 “Smak är känslan af naturens aldra hemligaste sanningar.” Bergh, 1923, p. 226.

15 “Ideala stylen är således den […] som visar naturen der hon skal vara och intet der hon är. […] och som ger en alfvarsam och en älskansvärd känsla för naturen.” Bergh, 1923, p. 230.

16 For Ehrensvärd, see eg. Moselius, 1934, pp. 110–111; Bergh, 1923, pp. 226, 230; Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 137–138. For Winckelmann, see Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst, 1755. For Sergel, see Georg Göthe, Sergelska bref, efterskrift till “Johan Tobias Sergel, hans lefnad och verksamhet”, Stockholm, 1900, pp. 28–29; Ragnar Josephson, Sergels fantasi, Stockholm, 1956, pp. 99–100; Josephson, 1997, pp. 151–152; Lisa Maria Ley, Kunst im Zeichen der Aufklärung: Sergels Menschenbild vor dem Hintergrund philosophischer, historischer, gesellschaftspolitischer und psychologischer Ideen des 18. Jahrhunderts, Hamburg, 2007, pp. 56–60.

17 Bergh, 1923, pp. 40, 240–241.

18 Bergh, 1923, p. 266.

19 “Hur verkar skönhet? När ögat får se det sköna, råkar det en ordning i naturen, som sätter saken för sinnet i et outsägeligt begrep, man känner och man begriper alt.” Bergh, 1923, p. 212.

20 For Winckelmann, see Alex Potts, Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History, New Haven, 1994, pp. 67–72, 101–112. For Ehrensvärd, see Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 139, 191–192.

21 See Bergh, 1923, p. 238.

22 See Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 82–83, 94–102, 145–152, 292–302.

23 “norberg vakar öfver unge Suter och qvinfolken förföra Suter”.

24 Moselius, 1934, pp. 77–78, 101–104; Frykensted, 1965, pp. 83, 86, 92–93.

25 “Det ena könet är intet bättre än det andra.” Bergh, 1923, p. 210.

26 Cederlöf, 1997, p. 125.

27 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York, 1990; Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”, New York, 1993.

28 Bergh, 1923, pp. 218, 242–227; Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 273–284.

29 Thomas Walter Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud, Cambridge, MA, 1990, pp. 1–24.

30 Laqueur, 1990, pp. 149–192. For antiquity, see Ville Hakanen, Ganymede in the Art of Roman Campania: Ancient Roman Viewers’ Experience of Erotic Mythological Art, Helsinki, 2022, pp. 76–90. One of the exponents of the new “two-sex model” was Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), who was also Ehrensvärd’s model and his father’s good friend. Linnaeus’s sexual classificatory system of plants seemed to provide evidence of sexual difference as one of the fundamental dichotomies of nature – although the system was constructed by projecting prevalent gender norms onto plants. See Laqueur, 1990, pp. 172–173; Holger Frykenstedt, Carl August Ehrensvärd och Linnétraditionen, Stockholm, 1997.

31 "Menniskjan är en varelse helt och hållen bygd på Physique.” Bergh, 1925, p. 211.

32 “Känner du igen dit kön, men Jan Sparres Doter har intet den äran att känna sitt kön, hon är en grad mer, och i den graden är Du ensamen.” Frykensedt and Hansson, 1971, p. 25. “Du är full med Dygd […] och som du fullkomlig i din natur då du tror dig ha rätt, en viss högd blandad med en Slags karavuln villja.” Ibid., p. 30.

33 “Du haft från vaggan ett Snille 500 år framman för alla våra hundrade tal.” Bergh, 1917, p. 227.

34 Moselius, 1934, p. 77; Bergh, 1923, p. 118.

35 Bergh, 1925, p. 98.

36 See Bergh, 1925, pp. 109, 291, 317, 351.

37 “Men i värket är Apolinne vakrare än Venus […] Skjönhet är ett Sätt och intet en Sak.” Bergh, 1917, p. 144. See section three of Kant’s Beobachtungen über das Gefühl des Schönen und Erhabenen (1764), where he argues that women have a predisposition for feeling and displaying the beautiful (“das Schöne”) and men for the sublime (“das Erhabene”).

38 Johan Henric Kellgren, Carina and Lars Burman and Torgny Segerstedt, Skrifter I: Poesi och prosa, Stockholm, 1995, p. 255.

39 See Potts, 1994, pp. 48–50; Whitney Davis, “Winckelmann divided: mourning the death of art history,” The art of art history: A critical anthology, D. Preziosi, ed., Oxford, 1998, 41–44.

40 Ann Öhrberg, Vittra fruntimmer: författarroll och retorik hos frihetstidens kvinnliga författare, Uppsala, 2001, pp. 227–242; Mary Wollstonecraft, Janet Todd, Marilyn Butler, and Emma Rees-Mogg, The Works of Mary Wollstonecraft: Vol. 5, A Vindication of the Rights of Men; A Vindication of the Rights of Women; Hints, London, 1989, p. 3/5.

41 Bergh, 1923, pp. 208, 229; Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 55–62. For Sergel’s parallel ideas, see Ley, 2007, p. 190.

42 Bergh, 1923, pp. 295–296.

43 Martin Myrone, Bodybuilding: Reforming Masculinities in British Art 1750–1810, New Haven, 2005, p. 4; Potts, 1994, pp. 127–128.

44 “Att se på denne Diomedes […] inspirerar courage och heroisme […]” Jacob Jonas Björnståhl, Resa til Frankrike, Italien, Sweitz, Tyskland, Holland, Ängland, Turkiet, och Grekeland, Stockholm, 1780, I, p. 321.

45 Bergh, 1923, p. 238.

46 For Ehrensvärd’s and Törnström’s relationship, see Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 152–154.

47 “Törnström ska gå till fots till Italien när han slutar sitt arbete, beklagar sig att ha så litet pängar. Lyckan sager det är nog. Minervas uggla flyger förut, fria konsten leder honom vid handen och Rikedomshornet flyger efter.” See Cederlöf, 1997, pp. 123–124.

48 See Pierre-François Hugues d’Hancarville, The Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of Sir William Hamilton, Köln, 2004 [1767–1776], pp. 27, 283–282.

49 “Men Törnström ler åt hela världen.” Nilsson, 1996, p. 261.

50 “[…] derigenom får man taflor af […] Jupiter Mars Apollo Venus Minerva och Juno uti gestalter af nakna Acteurer på en ostädad Theatre.” Bergh, 1916, p. 60.

51 Nationalmuseum NMH 209/1968. See Cederlöf, 1997, fig. 118.

52 See Josephson, 1956, pp. 511–516, figs. 658–668.

53 See Josephson, 1956, pp. 511–513, fig. 658.

54 “L’étendue de l’esprit, la force de l’imagination, & l’activité de l’ame, voilà le génie.” Transl. J.S.D. Glaus.

55 “[…] medfödda förståndets ljus, som kallas genie [… och som] riktar själen med mångfaldiga bilder och höga tankar”. Josephson, 1997, p. 141.

56 For a discussion of Sergel’s idea of genius and artistic creativity, see Ley, 2007, pp. 41–52.

57 “Genie är et öfversvämmande af egenskaper til någon högd öfver almänheten”. Bergh, 1923, p. 240. See Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 229–236.

58 “Utan hvad vi kalla Själ i ett Organiskt Djur är ej annat än det samma som Ljudet i en Ringklocka, när klockan är Sprucken så låter hon illa, hvilken rörelse-kjänsla man i en organisk kropp. behagar bestämma med själa kamp och möda.” Bergh, 1917, p. 175.

59 Bergh, 1917, p. 182; Bergh, 1925, p. 211.

60 Josephson, 1956, p. 512, fig. 661.

61 NMSk 907. See Josephson, 1956, pp. 33–34, fig. 15.

62 Potts, 1994, p. 127.

63 Potts, 1994, pp. 127–128.

64 Bergh, 1923, pp. 317–318. See Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 229–236.

65 Bergh, 1923, pp. 164–165, 314–315.

66 See Ulf Cederlöf, “1790-talet”, Sergel, Stockholm, 1990, pp. 145–157; Cederlöf, 1997, pp. 188–206; Cederlöf, 2011, pp. 148–151, 171–172; Josephson, 1956, pp. 525–538.

67 Bergh, 1917, pp. 53–57.

68 Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 277–279.

69 Bergh, 1917, p. 53. For Stoic and Epicurean thinking on needs and pleasure, see Christopher Gill, The Structured Self in Hellenistic and Roman Thought, Oxford, 2006, pp. 100–126, 130–131, 138–139, 207–290.

70 Bergh, 1925, pp. 292–293. See Frykenstedt, 1965, pp. 279, 336.

71 See Kellgren’s version of Horace’s Ode 1.26, first printed in 1774, and his version of Propertius’s Elegy 2.15, first printed in 1784, both published in his Samlade skrifter (Collected Writings) in 1796. Kellgren et al., 1995, pp. 282, 303–305. As noted by Josephson and Cederlöf, the maxim is represented most famously by Carl Mikael Bellman (1740–1795) in his Fredmans epistlar (Fredman’s Epistles), written from 1768 onwards and published in 1790.

72 Kellgren’s poem, or song, named Epikurismen (Epicureanism), first printed in 1796, but possibly written in 1774 or 1777, is titled “Anacreontic Ode” in the manuscript. Kellgren et al., 1995, pp. 105–106, 439. For 18th century “Anacreontism”, see Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Male Trouble: A Crisis in Representation, London, 1997, pp. 103–114.

73 For Dömestorp as “Olympus”, see Josephson, 1956, fig. 650.

74 See Thomas Lederballe, “Nicolai Abildgaard: Body and Tradition”, Nicolai Abildgaard: Revolution Embodied, T. Lederballe, ed., 2009, pp. 24–38; Myrone, 2005, pp. 89–90; Ley, 2005, p.

75 NMH 207/1963. See Josephson, 1956, fig. 724.

76 See Josephson, 1956, fig. 735. For Ehrensvärd’s slightly humorous versions of the same subject, see NMH Z 311/1957 and NMH Z 312/1957.

77 “Här den vackra Medaillongen”.

78 Potts, 1994, pp. 182–221; Davis, 1998; Robert Deam Tobin, “Winckelmann und die Menschenrechte”, Queer Archaeology: Winckelmann and His Passionate Followers – Queer Archaeology, Egyptology and the History of Arts since 1750, W. Cortjaens and C. E. Loeben, eds., Rahden, Westf., 2022, pp. 69–91.

79 “[…] et ändamål i stort, som ock de exprimerade lifsverkningarne, hvilka altid uttryckas der, inom Classen af det alfvarsamma, eller det ädla, eller det friska.” Bergh, 1923, pp. 229–230. For Ehrensvärd’s definition of “lifsverkningar”, here translated “action-guiding functions”, see Bergh, 1923, p. 255.

80 Bergh, 1923, pp. 207–208, 212, 215, 227. For the parallel use of “fullkomlig” by Adelcrantz, and Sergel, see Josephson, 1997, pp. 141, 147–148, 152.

81 Bergh, 1923, p. 200.

82 Potts, 1994, p. 164.

83 Potts, 1994, pp. 155–164, 180–181.

84 See eg. Raymond Martin and John Barresi, Naturalization of the Soul: Self and Personal Identity in the Eighteenth Century, London, 2000; Louis K. Dupré, The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture, New Haven, 2004, pp. 45–77.