ABSTRACT

Non-accidental violence in women’s gymnastics has gained significant attention, and is a sport where gender is clearly differentiated. Despite the volume of gymnastics research on these themes it seemingly had little impact in preventing harm. We conducted a critical interpretative synthesis of 45 articles to reexamine the literature for understanding of, and connections between, gender and violence. We found that where gender viewed as a structure was explicit, violence was not. Conversely where violence was explicit, gender was implicit and viewed in individualist terms. Only one article explicitly connected gender and violence recognizing violence as a gendered outcome. We encourage researchers to incorporate gender as a structure in analytical inquiries and identify the wider contexts and associated mechanisms through which gender intersects with violence. Doing so can help to develop prevention measures that align with international definitions of gender-based violence.

Introduction

Violence in women’s gymnastics has gained mainstream and worldwide attention, sparked by the 2016 USA Gymnastics Sex Abuse Scandal and the consequent 2020 Netflix documentary Athlete A. A global torrent of gymnasts speaking out about maltreatment and abuse through the #gymnastalliance movement followed to reveal a sport that has historically and systematically violated gymnasts in the pursuit of performance. Since the summer of 2020, several investigations commissioned by national governments, national sports governments, and national gymnastics federations have been conducted into elite women’s gymnastics.Footnote1 In addition, all forms of non-accidental violence (Mountjoy et al., Citation2016) are commonplace in documented accounts and portrayals of gymnastics culture, including research literature (evidenced in this article), investigative journalism (see Ryan, Citation1996) and documentary and popular media (see Netflix documentary Athlete A). Collectively this portrays a global gymnastics culture of intimidation and fear wherein various forms of non-accidental violence, including psychological and emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and physical and psychological neglect, are prevalent and align with current definitions and frameworks in sport (Fortier et al., Citation2020, Mountjoy et al., Citation2015, Citation2016, Stirling, Citation2009). For example, gymnastics coaches can inflict emotional abuse, including verbal threats, humiliation, belittlement, or constant criticism toward gymnasts, significantly impacting their emotional well-being (see Jacobs et al., Citation2017, Salim & Winter, Citation2022). Physical abuse involves the deliberate use of physical force against gymnasts, such as hitting, slapping, pushing, or any form of physical punishment that causes harm or pain (Barker-Ruchti and Tinning, Citation2010, Pinheiro et al., Citation2014). Sexual abuse encompasses any form of unwanted or non-consensual sexual contact, advances, or exploitation of gymnasts by coaches, trainers, or other individuals in positions of authority, such as the USA Gymnastics (see Fisher & Anders, Citation2020). Finally, neglect refers to the failure to provide proper care, support, or supervision to gymnasts, which can lead to physical or emotional harm, for example, the withholding or restriction of food and water (see Stewart et al., Citation2015, Whyte, Citation2022).

Against this backdrop, numerous government-commissioned investigations and accounts show the urgency for change in women’s gymnastics at all levels. These investigations and reports collectively emphasize the necessity for comprehensive and prompt reforms within the sport. Strategies to transform women’s gymnastics include increasing the minimum age to compete in senior competitions (Cervin, Citation2020), suspending abusive coaches and federation officials, and creating independent bodies to report abuse (Kerr & Kerr, Citation2020). Whilst we welcome the recent demand for change, we also feel compelled to draw attention to the disconnect that denotes the observed disparity between the substantial volume of literature available on abuse in women’s gymnastics (over five decades) and the limited tangible effects it has had, particularly concerning addressing the cultural and systemic challenges prevalent within it. Furthermore, the proposed solutions put forth thus far seem to be somewhat reactive rather than a comprehensive approach, failing to address the deep-rooted causes underlying the issues at hand.

One of the deep-rooted and overlooked causes of non-accidental violence in gymnastics is, we believe, the concept of gender. Gymnastics is a sport that exhibits gender distinctions, with separate sex disciplines for boys and men (male) and girls and women (female) participants. In addition to these distinctions, most participants are girls,Footnote2 and women’s artistic gymnastics (WAG) encompasses unique apparatus, performance expectations, judging criteria, uniform requirements, and cultural codes different from those of men’s artistic gymnastics (Cervin, Citation2021). Rhythmic gymnastics (RG) is an Olympic sport exclusively for girls or women. WAG and RG are heavily influenced by traditional notions of femininity, which manifest in physical appearance and behavior during and outside competitions (Weber & Barker-Ruchti, Citation2012). Scholars have noted that given the history of gymnastics, the head coaches of elite girl gymnasts are often men and the paternalistic nature of the relationship has been observed (Cervin, Citation2021). This matters because, although complex and multifaceted, gender is related to violence, acknowledged in the United Nations (UN, Citation1993, Citationn.d.) and the European Commission’s (EC, Citationn.d.) adoption of the term Gender-Based Violence (GBV). Both the UN and EC acknowledge that gender plays a significant role in shaping power dynamics, social norms, and societal expectations, which can contribute to the occurrence and perpetuation of violence.

Despite the significant over-representation of girls and non-accidental violence in women’s gymnastics research, we found ourselves asking why in five decades of research, the concept of gender in relation to violence has received minimal attention. How do we make sense of the gendered dimensions of gymnastics and the levels of reported violence? We also ask that if gender were acknowledged in non-accidental violence in women’s gymnastics, how might the situation change? These questions underscore the importance of critically examining and exploring relations between gender and non-accidental violence in women’s gymnastics. Moreover, they emphasize the potential implications of such a perspective within the sport. Therefore, our study aims to conduct a critical interpretive synthesis (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006) of the available gymnastics’ literature, specifically focusing on the intersection of gender and violence. Through this investigation, we aim to uncover underlying assumptions, power dynamics, and potential biases that impact and shape the research findings to identify systemic challenges and possible avenues for transformative change within gymnastics.

Gender structure theory

Risman’s gender structure theory (Citation2004, Citation2018) synthesizes previous theories from social science traditions (including biology, psychology, and sociology) that have sought to explain gender. This multidimensional framework is helpful for this study. In what follows, we briefly outline the main social traditions identified by Risman (Citation2004), followed by the central tenets of gender structure theory to apply this theoretical lens to the gymnastics literature in this study.

Understanding gender: Traditional and perspectives

The first tradition focuses on the origins of individual sex differences, whether biological or social. Risman (Citation2004) explains that while biological differences between the sexes may exist, they do not necessarily explain or justify gendered behavior or outcomes. She suggests while we can accommodate reproductive differences, there is not a priori reason that we should accept any other role differentiation simply based on biological sex category, arguing:

Before accepting any gender elaboration around biological sex category, we ought to search suspiciously for the possibly subtle ways such differentiation supports men’s privilege. (Risman, Citation2004, p. 19)

The concepts of sex and gender, though not synonymous, are frequently confused or combined, even in the medical world (Bewley et al., Citation2021), despite The World Health Organisation (WHO, Citationn.d.) and the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH, Citationn.d.) clear definitions. The WHO and NIH define gender as the characteristics of women and men that are socially constructed, where individuals act in many ways that fulfil the gender expectations of their society. Sex, on the other hand, refers to those biologically determined characteristics. Psychological explanations of gender have tended to focus on individual-level factors, such as sex-role training, modeling, and socialization, which can lead individuals to internalize gendered norms and expectations. Risman (Citation2004) suggests that individual-level explanations are insufficient for understanding gender as a social structure. Instead, we must also consider the broader social and cultural context in which gender is constructed and reproduced.

Thus, a second tradition emerged and focused on how the social structure (as opposed to biology or individual learning) creates gendered behavior. This approach examines how gender is situated in various social institutions, such as the family, the workplace, and the legal system, and how these institutions create and reinforce gendered behavior and outcomes (Risman, Citation2004). The third tradition, also a reaction to the individualist thinking of the first, emphasizes social interaction and accountability to others’ expectations, focusing on how “doing gender” creates and reproduces inequality (e.g., West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). This approach concerns how individuals construct and perform gender in everyday lives; however, more than simply a matter of individual-level factors, performances are governed by broader social and cultural social norms and expectations. Finally, the fourth tradition is an integrative approach or intersectionality, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of gender with other forms of social inequality, such as race, class, and sexuality. “Intersectionality” stems from Crenshaw’s (Citation1991, p. 1224) acknowledgment that racism and sexism in black women’s lives cannot be captured by looking at the domains of race and gender experience separately. Our current thinking aligns with this tradition, and the perspective advocated by Risman (Citation2004, Citation2018) in her gender structure theory. We agree with the prevailing consensus that understanding gender necessitates an examination that goes beyond isolated analysis and considers the intricate web of intersecting inequalities. This recognition encompasses an awareness of the historical and contextual subtleties that distinguish the mechanisms driving inequality across various categorical divisions, including gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, class, and notably, age. Thus, we acknowledge age as an often overlooked yet highly pertinent domain within the concept of intersectionality. Age assumes particular significance in the realm of gymnastics, where institutional practices contribute to the construction of bodies, perpetuating inequality with considerable influence. The body acts as a distinguishing marker between men and women, adults and children and is subject to diverse interpretations. Ageing bodies are not only employed to demarcate but also to sustain inequalities (Calasanti & King, Citation2015).

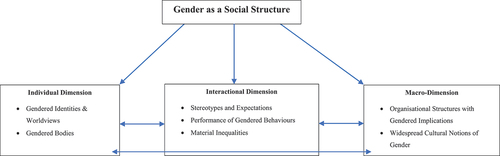

Gender structure theory

Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory is based on understanding structure as a dialectical process with recursive causality (Giddens, Citation1984). Risman’s (Citation2004, Citation2018) perspective is that gender is a structure that shapes an individual’s orientations, interactions with others and larger societal patterns at the macro level. There is a reflexive relationship between structure and individual action, meaning that individuals’ actions are constantly influenced by existing structures, either reinforcing or challenging these structures. Risman (Citation2018) suggests that viewing gender as a structure rather than an individual attribute or difference enables insights into how gender influences ongoing practices at the individual, interactional and macro levels. Material (physical bodies, laws or geographical locations) and cultural (ideological or socially constructed ideas) processes that orientate perspectives and worldviews take place at each level (see ). Crucially she (Citation2004, Citation2018) argues that this perspective can help us reveal how gender intersects with other forms of social inequality, such as race/ethnicity, social class and age.

Figure 1. Gender as a social structure. Adapted from Scarborough and Risman (Citation2017, p. 2).

At the individual level, these processes shape how individuals experience their bodies. At the interactional level, they influence expected behaviors, and how individuals are organized and represented by formal institutions, and at the macro level, these processes affect how individuals are ruled and categorized by governing bodies and legal systems. Differentiating between cultural and material processes at each social dimension, Risman (Citation2018) sheds light on the dynamics of gender progress, stability, and contestation. For example, she acknowledges that gender creates and perpetuates gender stereotypes, expectations, and inequalities but also recognizes that individuals and groups can actively interpret their realities and resist gender structures, leading to changes in gender equality. For this change to occur, she suggests, it is crucial to challenge the expectations attached to being male or female (Risman, Citation2018).

Understanding gender and violence

Non-accidental violence is intentional harm or aggression committed against an individual or a group. It involves deliberate actions that cause physical, emotional, or psychological harm and are not accidental or unintentional (Mountjoy et al., Citation2016). In the context of sport, this encompasses a wide array of aggressive behaviors, abusive acts, and detrimental actions directed at athletes, coaches, officials, and other individuals involved in the sports environment. These manifestations may be physical violence, emotional abuse, sexual misconduct, bullying, hazing, or any conduct designed to inflict harm or exert control. Mountjoy et al. (Citation2016) adopt a comprehensive framework that recognizes the purposeful nature of such behaviors by employing the concept of non-accidental violence as an overarching term. We use the term violence from here on to denote non-accidental violence following Mountjoy et al. (Citation2016).

The role of gender in non-accidental violence has received some attention in sports. Roberts et al. (Citation2020) identifie eight narrative reviews and two systematic reviews about predictive factors that include gender stereotypes, heteronormativity and hegemonic masculinity, and fear of reporting (Bjørnseth & Szabo, Citation2018, Brackenridge & Fasting, Citation2002, Hartill, Citation2005, Kirby et al., Citation2008, MacDonald, Citation2014). Whilst significant, gender is not always clearly defined. It often defaults to meaning at the individual level of the perpetrator and the victim to explain their roles in power and vulnerability. Gender and sex are used interchangeably, which confounds the understanding of violence and abuse, and limits prevention measures (Bekker et al., Citation2018, Forsdike & O’Sullivan, Citation2022, Felipe-Russo & Pirlot, Citation2006).

The United Nations (UN) and the European Commission (EC) recognize gender as a risk factor for violence in their term Gender-Based Violence. The EC (Citationn.d.) defines gender-based violence (GBV) as:

Violence directed against a person because of that person’s gender or violence that affects persons of a particular gender disproportionately. Violence against women is understood as a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women and shall mean all acts of gender-based violence that result in, or are likely to result in

• physical harm

• sexual harm

• psychological harm

• economic harm

• or suffering to women

The term identifies factors such as stereotypes, entitlements, power, objectification, and status to explain violence and abuse, especially against girls and women (Felipe-Russo & Pirlott, Citation2006). Risman (Citation2004) emphasizes that GBV is influenced by gender as a social structure; it is a “gendered outcome.” This term helps explore how violence can emerge because of prevailing gender dynamics in society.

Importantly the term GBV acknowledges that violence can be a gendered outcome in several ways. Firstly, some forms of violence disproportionately affect individuals based on gender, such as domestic violence and sexual assault, which predominantly target women and girls. This is often rooted in patriarchal systems that perpetuate unequal power relations between genders, illuminated by the USA Gymnastics sexual abuse case. Secondly, gender norms and stereotypes can contribute to the perpetuation of violence. Traditional notions of masculinity that emphasize aggression, dominance, and control can create an environment conducive to violence. Similarly, stereotypes about femininity, such as the idea that women are weak or submissive, are harmful and can contribute to the perpetration of violence against women and the underreporting of such incidents.

Methodology

Critical interpretive synthesis

Critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) serves as a methodological alternative to traditional systematic reviews (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). In contrast to other qualitative synthesis approaches, CIS aims to generate new theoretical explanations or synthetic constructs by examining diverse evidence (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019). At its core, CIS embraces an interpretive philosophy, emphasizing a critical perspective that challenges the assumptions and underlying ideologies present in the literature. This critical stance challenges the notion of certainty in literature and recognizes that knowledge is produced from different standpoints, thereby inviting scrutiny of underlying assumptions (McFerran et al., Citation2016, Annandale et al., Citation2007). Researchers practising CIS engage in reflexivity, recognizing their own biases and subjectivity throughout the synthesis process and engage in an iterative process of analysis, synthesis, and refinement, allowing for ongoing reflection and revision of emerging theories. The series of iterative cycles or stages build upon one another to generate new insights and theoretical explanations and ultimately contribute to a deeper understanding of the subject matter. In our research, we specifically opted for CIS due to our focus on theoretical assumptions and the complex landscape of literature surrounding the conceptualizations of gender and violence in women’s gymnastics. Though it is a somewhat flexible exploration given its iterative nature, within this framework, we sought to facilitate transparency and comprehensive reporting as far as possible, guided by ENTREQ (Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the synthesis of Qualitative research) (Tong et al., Citation2012).

Formulating the review question

The review questions in a CIS differ from those in other forms of qualitative synthesis in terms of their scope, focus and analytical approach. In a more traditional qualitative synthesis, questions are typically more straightforward and focus on identifying and summarizing common themes and aggregating findings on a particular topic across the included studies. In a CIS, the review questions are initially emergent and exploratory. They are developed concurrently and iteratively with the analysis and concepts, aligning with the interpretive inquiry tradition (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006, Tong et al., Citation2012). Our initial review questions sought to frame an exploration of the underlying assumptions, power dynamics, and potential biases that impact and shape the research findings, taking a more nuanced and analytical approach as our analysis developed.

The purpose of this research is to examine how gender and violence are conceptualized, articulated and interconnected in the context of women’s gymnastics research literature. To achieve this, we formulated the following review questions:

How is gender explained and conceptualized in the existing gymnastics literature?

How is violence explained and conceptualized in the context of gymnastics literature?

What are the predominant constructs and portrayals of the relationship between gender and violence in gymnastics literature?

In alignment with a CIS methodology, we assert our theoretical standpoint on gender. Our perspective challenges approaches that consider gender as a fixed and natural categorization based on static sexual differences, often viewed in binary terms. Instead, we embrace the notion of gender as a construct akin to social construction feminism (Knoppers & McLachlan, Citation2018, Risman, Citation2018) and align with Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included were empirical and theoretical or conceptual articles containing analyses of women’s gymnastics published between January 1997 and August 2022 that reported on issues of gender and violence. Excluded were articles containing data from other sports and articles on gymnastics that were scientific, technical, and medical and did not report on gender or violence.

Data sources, electronic search strategy and screening methods

We initially identified articles using a research tree compiled and published by the International Socio-Cultural research group on Women’s Artistic Gymnastics (ISCWAG) (https://www.oru.se/english/research/teams/hv/iscwag/research-tree/). The research tree combines ISCWAG’s knowledge in a hierarchized thematic structure, containing seventy-six articles from 11 global gymnastics scholars on or including gymnastics. Twenty-one articles met the inclusion criteria and were accessible in English.

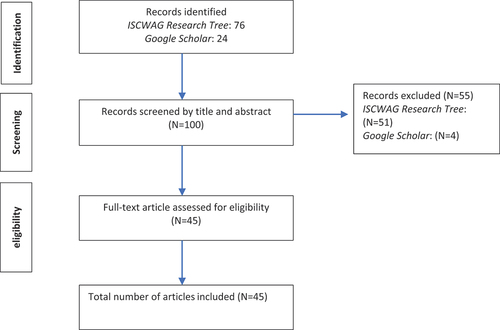

Second, we identified additional articles using electronic databases accessed via our respective university search tools combining databases (for example, including British Medical Journal, SPORTDiscuss and SocINDEX) and Google Scholar. Search terms were: “women”; “gymnastics”; “women’s artistic gymnastics”; “abuse”; “violence”; “harm”; “gender”, revealing an additional 24 articles. We purposively screened articles, a feature of CIS, to select papers that would enable us to answer the review questions. Forty-five articles were included in the final sample (). shows the search strategy and screening process.

Data extraction, software, reviewers, and coding

Each article was analyzed in full, line by line, and discussed by both authors. Text sections were extracted electronically and entered in outliner software WorkFlowy, and a tagging system with an index was created. A preliminary category emerged that distinguished articles whose focus and analysis were explicitly about violence in gymnastics (N = 9, see Appendix A) and those whose focus was not on but contained a discussion of violence and abuse or consequences thereof (N = 36, see Appendix B). We used the term non-accidental violence as an umbrella term for all forms of violence, maltreatment and abuse outlined by Stirling (Citation2009) and Mountjoy et al. (Citation2016), including emotional/psychological, physical, and sexual abuse and physical, emotional, and educational neglect. The tag index was as follows:

#GI (Gender Implicit): Applied to articles where gender was acknowledged but not fully explained in the main arguments or when there was ambiguity in relation to sex.

#GE (Gender Explicit): Applied to articles where gender was an explanatory concept, incorporating socio-cultural dimensions and prominently theorized in the main ideas.

#VE (Violence Explicit): Applied to articles that explicitly focused on violence as a central inquiry or as the article’s aim.

#VI (Violence Implicit): Applied to articles with evidence or acknowledgment of violence, but it was not the primary focus of investigation and analysis.

We combined tags to focus our analysis across the dataset (e.g., #GI #VE). Using Workflowy was an essential first step in identifying the theoretical perspectives of gender employed in the articles. Using Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory, we critiqued how the literature had understood gender and the assumptions it drew upon concerning violence in gymnastics and created a matrix of gender and violence as constructed in articles (see ).

Table 1. The matrix of violence and gender construction.

Results

illustrates the complexity of the dataset. Authors’ positioning across articles may vary, and we guard against absolute and finalized thinking. illuminates those choices (and oversights) that authors may not be aware of, giving us a new picture of women’s gymnastics literature and how we understand the relationship between gender and violence within.

Gender as absent in reporting violence toward gymnasts

Gender as a concept is absent (GA) in 8 articles (see ). Of these, implicit violence (VI) is observed in 7 articles, and explicit violence (VE) is observed in 1. Put another way, seven articles report violence toward gymnasts, such as within the coach-athlete relationship (22), as coaching methods and training practices that are perceived to facilitate gymnastics success but are harmful to gymnasts (16; 45), as overuse and other injuries (18; 39), and when retiring from gymnastics (34), but gender is not acknowledged. One VE article (40) categorizes emotional abuse but does not mention gender. Gender is an oversight in both explicit and implicit reporting of violence in the context of women’s gymnastics, raising concern.

Table 2. The list of the reviewed articles where gender was absent.

Gender as implicit in analyses of violence toward gymnasts

Gender as an implicit concept (GI) represents the most significant number of articles (see , N = 27). In our analysis, gender is not explicitly highlighted as the focus, but we read it in the undertones and assumptions present in scholars’ arguments. Gender and sex are frequently conflated akin to an emphasis on explaining gender primarily at the individual level (Risman, Citation2018) or, in some cases, not at all. Of the 27 articles containing violence, nine explicitly address violence (VE), while 17 implicitly touch upon violence (VI). Crucially, five GI articles directly address the USA sexual abuse case (2, 3, 5, 6, 8), suggesting that gender is not explicitly regarded as an explanatory focus for the cause of sexual abuse among at least 250 female gymnasts.

Table 3. The list of reviewed articles where gender was implicit.

In the following sub-sections, the articles draw attention to their gymnasts’ social roles, interactions with coaches and parents, physical and developmental aspects, scripted movements, and aesthetic ideals within the framework of gender structure theory at the individual and interpersonal levels. However, gender is not explicitly addressed as a central focus for analysis. Gender, we argue, is an absent yet influential presence. We identified two sub-themes: Age (Gender) and Vulnerability and (Gender) and Health.

Age, (gender) and vulnerability

In these articles, gymnasts are portrayed as children first and gendered subjects (girls) second. Gymnasts are assumed to be particularly vulnerable mainly due to their status as children. While the differences in power and social positioning between adults and children are explicitly discussed, the power and social dynamics between men and women at the macro-level are not addressed. This situation presents a concern as the intersectional inequality of being a female and a child, referred to as the “girl child” by the United Nations (UN), is not adequately addressed in gymnastics literature. Gymnasts as girl children appear to be overlooked despite clear evidence of a violent culture.

Among the articles reviewed, nine explicitly address sexual, psychological, emotional, and physical abuse (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Scholars distinguish between the girl and child by highlighting the vulnerability associated with the child’s position, which requires protection from abusive behaviors and situations. They fail to draw adequate attention to the context of adult male coaches coaching girl gymnasts. The influential position of coaches is acknowledged and explained at the macro-level in cultural and hierarchical terms, but gender is not. The authors of these studies adopt various academic perspectives, including human rights (1), unionization (2), (cultural) sport psychology (3; 9), medicine (5) legal (6) and human relations (8). For example, Edelman and Pacella (Citation2019), Mountjoy (Citation2019), and Novkov (Citation2019) center their investigations on the USA sexual abuse case, emphasizing cultural and structural failures, including the portrayal of gymnasts as children and the misuse of power dynamics.

Gender, as a central intersecting inequality, is often overlooked or deemed beyond the scope of the analysis. The title of Jacobs et al.’s (Citation2017) article, “You don’t realize what you see!:” The Institutional Context of Emotional Abuse in Elite Youth Sport’ focuses on emotional abuse in elite youth sport but does not directly address gender or the specific context of gymnastics. Their study involves club directors and coaches, all of whom are men coaching girl gymnasts. The interpretations of abuse toward gymnasts primarily focus on their age, highlighting their vulnerability and lack of autonomy in interactions with coaches. However, the authors do not give attention to the performance of gender as a significant intersecting factor in interpersonal relationships within this context. Instead, their focus lies on cultural processes related to age expectations, evidenced in the following quote from a gymnastics club director discussing coaches and their authority over gymnasts Jacobs et al. (Citation2017, p. 133):

They do not get that power from adults but [get it] only in gymnastics where there is a big difference in age, as there is between them and the girls. They are the bosses in the gym, which is why they have conflicts with the board. They [coaches] do not know how to behave with adults.

Jacobs et al. (Citation2017) acknowledge that they do not explore how femininity contributes to the relationship between male coaches and female gymnasts, as it falls beyond the scope of their article. Including data from parents in the articles also highlights the gymnasts’ ages. The paternalistic father-like coach-gymnast relationship is considered troublesome where parents (mothers) are bystanders. For instance, Smits et al. (Citation2016, p. 75) note that the “responsibility and commitment of the parents seemed to inform modes of interaction that reinforced obedience to the coach.” Gender is relevant to the analysis of the coach as a father figure. Scarborough and Risman (Citation2017) note that the family is a terrain where gender is contested and inequality, though improved, is still prevalent. Power is rooted in cultural notions of gender that guide behavior and perceptions, leading to specific tasks being assigned to women and others to men, historically including control and discipline. These gendered processes affecting family dynamics are likely to spill over into the gymnastics environment when coaches’ identities are associated with being father figures responsible for the care of children. Moreover, the articles suggest that in women’s gymnastics, men are the minority group yet maintain positions of power and advantage.

(Gender), health and the individual

These articles link implicit violence with puberty, weight control, disordered eating, and the ideal (gendered) gymnast body. These elements pertain to gender at the individual and the interpersonal levels of gender structure theory and are complexly intertwined. The articles revealed instances of violence, including verbal abuse from disparaging comments, public weigh-ins, body shaming, and restrictive practices around food and water that resulted in illness. Surprisingly, gender as a concept is not explicitly analyzed in the articles, and, in some cases, it is absent from the text. For example, eating disorders are implicitly acknowledged to be associated with the ideals of femininity (gender), thus primarily affecting female gymnasts rather than male gymnasts (sex) (13, 15, 25, 35, 36, 42, 43) as in the following example:

The research to date clearly indicates that young women and particularly those in aesthetic sports are vulnerable to body dissatisfaction, eating disorders and disordered eating. In addition, comments made by others can have powerful effects on the development and maintenance of disordered eating in young women, including athletes. The purpose of this study therefore was to better understand the eating and weight control behaviours of female gymnasts. (Kerr et al., 2006, p. 30)

Those articles focusing on disordered eating emphasize that female gymnasts (sex) are particularly vulnerable to eating disorders. Definitions of gender are not clear though some cite influences such as the media and the emphasis on gymnastic leanness as primarily responsible. Neves et al. (Citation2017) also linked extrinsic pressure regarding body weight and specific attire (leotards for women and girls) to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating over time. While gender ideals and the leotard’s role are not explicitly explained, both studies acknowledge the role of society and gymnastics culture in promoting body ideals. However, gender’s role as a cause of violence associated with eating disorders remains implicit. The recommendations primarily focus on individual-level solutions, such as educating coaches, gymnasts, judges, and parents on healthy eating and body image. This approach tends to view gender at the individual level rather than at a structural level, for example, in terms of the rules concerning the leotard or cultural meanings of gender.

The connection between gender as a socially constructed concept and violence is not explicitly addressed; instead, it is tacitly equated to sex. The discourse that female gymnasts are naturally predisposed to experiencing such violence implies that responsibility lies at the level of the individual, not society. Prevention recommendations are focused on individuals and the biomedical body, such as educating coaches about nutrition and healthy eating for female adolescent development. The socio-cultural environment is not targeted in the suggested solutions or prevention strategies. As a result, the social construction of gender remains implicit as a cause for violence associated with eating disorders in gymnastics.

In addition to disordered eating, puberty and menarche are reported to be challenging for girls in gymnastics. Deliberately delaying menarche is considered a form of violence and is related to practices that encourage weight loss and the preference for pre-pubescent bodies in gymnastics. This perspective suggests that female gymnasts encounter distinct developmental challenges during adolescence, and the sport of gymnastics can complicate their development (e.g., 43). Attention is drawn to puberty as a biological and psychosocial developmental issue for girls in gymnastics, primarily emphasizing sex and individual factors rather than the environmental context.

Gender as explicit in analyses of women’s gymnastics

Gender as a clear structural concept (GE) represents ten articles (see , column 3). Here we observe gender to be the clear focus of analysis. Of these ten articles, 9 contain VI, focusing on the changes to WAG during the 1970s, especially the transformation from an adult body and a calisthenic-type gymnastics to a child body and a risky acrobatic – type gymnastics (11; 19; 20), representation of gymnasts in the media (21; 44), changes to the rule book, the Code de Pointage (33), the fear gymnasts might experience (23), specific gymnasts and their influence (e.g., Nadia Comaneci), and older gymnasts (27; 30). Among the articles analyzed in the CIS, only one (14) utilized a gender perspective to focus on and interpret violence in women’s gymnastics. This admission indicates that when scholars view gender through a more discursive lens, violence is not the focus. It further means that out of the 45 articles sampled in our CIS, only one incorporated a gender perspective to examine explicit violence in women’s gymnastics. We, therefore, identify two sub-themes: Gender (and Violence) in Women’s Gymnastics and Gender and Violence in Women’s Gymnastics as Inextricable.

Gender (and violence) in women’s gymnastics

In these articles (N = 9, ), gymnasts are viewed as gendered subjects, and the difference in power and social positioning between men and women is acknowledged. Most (N = 5) recognize the girl-child as relevant, and all ten articles are empirical. However, despite addressing gender and identifying its relevance to the context of non-accidental violence in the culture of women’s gymnastics, they do not explicitly explore the connection between gender and non-accidental violence or bring violence to the forefront as their focus. Analyses are focused at the interactional and macro-level levels of Risman’s gender structure theory.

Table 4. The list of reviewed articles where gender was explicit.

In GE VI articles, the gendered history of gymnastics is relevant, i.e., the feminization of female gymnasts. Official documents reveal that governing bodies ensured women’s gymnastics differed from men’s via apparatus and performance requirements (e.g., strength movements for men and dance movements for women). From a gender perspective, male and female bodies are shaped or coded to elicit specific binary opposing meanings (11, 19, 20, 24, 33, 44). For example, Cervin (Citation2020) reveals the International Gymnastics Federation’s (FIG) stratification strategies for women’s gymnastics, including differentiated apparatus, performance requirements, and attire to prevent direct comparisons with men’s gymnastics. Articles emphasize that the feminine-childish appearance, with V-cut leotards, split/straddled legs, arched backs, and propped hips, is the desired image for women and girls in gymnastics, forming a pervasive public perception of the female gymnast.

The articles reveal the heteronormative sexualization and vulnerability of gymnasts based upon the meanings associated with the image of the sexualized girl-child, even where gymnasts are adults. These articles show that the gymnast community values child-like bodies and views femininity as pleasing, making gymnasts objects of (pleasurable and sometimes erotic) consumption. For example, Weber and Barker-Ruchti (Citation2012) found that media professionals use feminization strategies in sports photographs, such as capturing smiling gymnasts, emphasizing their crotch or bottom, and adding sexualized captions.

While we may interpret some differences between male and female bodies as medical facts, here articles highlight how the combination of arched backs, splits, leotards, and artistic expression, set to music, reflects the naturalization of social differences. This observation underscores the belief within the gymnastics community that women’s gymnastics is best suited for child-like bodies, and femininity remains a valued attribute. In this review, it is essential to note that only a limited number of studies explore the emergence of older, more muscular, and powerful women and girls’ gymnastics bodies observed primarily in Western nations (Stewart & Barker-Ruchti, Citation2021). We acknowledge that the balance between these elements may vary based on cultural and country-specific factors.

The articles provide evidence of gender’s influence on women’s gymnastics, shaping current ideals, systems, practices, and experiences. They were published before the 2019 USA sexual abuse case, strengthening our argument that violence was not explicitly connected to gender, indicating we could not see the risk factors for an incident like this to have occurred.

Gender and violence in women’s gymnastics as inextricably linked

Only one article was categorized as GE VE, where gender is explicitly relevant to reported violence. Barker-Ruchti and Tinning (Citation2010) connect gender and forms of corporeal discipline by exploring how women’s bodies are disciplined and objectified and how this discipline reinforces traditional gender stereotypes and ideals. As an illustration, the authors highlight that the female body is frequently perceived as “pathological, excessive, unruly, and potentially disruptive to the established norms” (p. 17). They contend that the demands for discipline and compliance imposed on gymnasts contribute to the notion that the female body requires regulation and correction. Types of non-accidental violence are identified and include adherence to strict training regimes that require gymnasts to push themselves to their physical limits. Barker-Ruchti and Tinning (Citation2010) also discuss how gymnasts’ bodies are disciplined through clothing prescriptions and aesthetic sequences in their routines, arguing that these regulations emphasize the gymnasts’ feminine body line and require them to portray feminine attributes such as gracefulness and elegance. This article connects macro-level rules to gendered bodies and subjectivities at the individual and interactional levels and explains non-accidental violence in all its forms as an outcome.

Further, gender as a structure explains how women coaches can adopt masculine gymnastics coach practices that enable them to inflict violence. Without a gendered understanding, women’s use of violence may go unnoticed and contribute to normalizing the violence women perform. Women fulfil significant roles in coaching women’s artistic gymnasts and are the only coaches in rhythmic gymnastics. Moreover, the coercive regulation of gender identities violates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and Human Rights.

Discussion

The purpose of this critical interpretive synthesis review of gymnastics literature was to shed light on the concepts of gender, violence, and assumptive relationships to achieve critical reflection and offer a new perspective on the existing body of work. Through this investigation, we sought to uncover implicit assumptions, power dynamics, and potential biases that influence research findings. Notably, the relationship between gender and violence has been overlooked in gymnastics literature thus far. Given the complexity of this subject, the CIS approach was well suited to critical orientation and exploration of emerging theoretical ideas (Dixon-Woods, Citation2006).

The findings highlighted different perspectives and understandings of gender at the individual, interpersonal and macro-levels of Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory. These perspectives were evident in reporting violence in a significant body of gymnastics research related to, or that contained violence. Significantly, implicit meanings of gender were associated with traditions, such as developmental psychology, that focus on individualist thinking. In contrast, explicit purposes were associated with traditions, such as sociology and history, that viewed gender as an outcome of social structure. Through the CIS, we can see that gender as a concept is not consistently understood in the context of violence in women’s gymnastics, meaning that violence as an outcome of gender is not always analyzed or recognized as relevant. This state of play has implications for the development of effective prevention strategies.

Approaches that emphasize gender at the individual level have several limitations. One is that a focus at this level overlooks the broader social and cultural context in which individuals make choices and construct identities. For example, we may assume female gymnasts have a personal preference for the leotard, performing effeminate movements to music and hiding puberty instead of looking to gymnastics organizations that govern gymnastics with gendered implications, reinforcing gender stereotypes and expectations at the interactional level. Scarborough and Risman (Citation2017) remind us that while recent studies show biological factors to play a small but significant role in forming gendered personalities, cultural processes are shown to be more influential in shaping gendered selves. The impact of pervasive gender differentiation in the gymnastics environment may cause gymnasts to interpret social phenomena in gendered ways and internalize social patterns (Bem, Citation1993) that masquerade as personal preferences or choices in behavior.

While empowering gymnasts and monitoring coaches are valuable suggestions, they are not the only solutions. Relying solely on these measures can reinforce the idea that gender differences are natural and inevitable. In other words, these suggestions may overlook the systemic issues related to gender and violence in gymnastics. Gymnastics perpetuates gender distinctions at odds with international definitions and policies that promote gender equality. The UN recognizes gender as socially and culturally produced, with equality as a central principle of its values and human rights. In addition, Mountjoy et al. (Citation2016) also draw attention to the need to protect athletes from non-accidental violence, incorporating the gendered nature of violence.

We draw attention to the usefulness of Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory, which conceptualizes that gender is a system of inequality, and we can alter gender inequality through changes to ideals, contexts, materials, and conduct. Effective transformation, therefore, must be at more than the individual and interactional levels; in the case of gymnastics, removing “bad apples” or educating perpetrators on behavior is not enough. While this does not abscond perpetrator responsibility for being violent, it does leave out explanations for how male and female coaches’ identities, behaviors and practices are shaped by gender, which is a risk factor for violence. Expanding gender to the institutional domain allows us to see how male and female coaches’ power is shaped by gender ideology and organizational practices (Roberts et al., Citation2020), which has been overlooked in gymnastics until now. Seeing gender as a structure allows us to understand how female coaches can also be involved in gender-based violence, challenging the assumption that only male coaches should be closely monitored. Female coaches may adopt a more dominant coaching approach necessary to gain respect in gymnastics and enact professional expectations to be perceived as competent and effective coaches. For example, where the dominant image of the female gymnast is associated with femininity and a child-like appearance, female coaches may feel pressure to conform to these expectations, possibly leading to non-accidental violence (such as hiding food, weight shaming) to achieve such ideals. Consequently, gender viewed as a structure means violence can be seen as a gendered outcome.

Through our CIS review, it also became evident that gender is not currently examined from an intersectional perspective and should be. By viewing gymnasts merely as “children” rather than recognizing them as “girl children”, the role of gender as a potential cause of violence toward gymnasts could be downplayed. Risman (Citation2004, p. 16) emphasizes the significance of intersectionality:

We cannot study gender in isolation from other inequalities, nor can we only study inequalities’ intersection and ignore the historical and contextual specificity that distinguishes the mechanisms that produce inequality by different categorical divisions, whether gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, or class.

The CIS has exposed the variations in analyses of gender, challenging the assumptions that might have been made from different perspectives, including psychological, historical and sociological approaches, and aiding a more nuanced understanding.

Researchers of women’s gymnastics should pay greater attention to the broader social context that perpetrates violence in sports. These may reveal uncomfortable truths about the foundations on which women’s gymnastics is based and its role in perpetuating gender stereotypes that the UN and EU are trying to eradicate under their gender equality policies. These include the V-cut leotard, rules, media representations, coach education materials, and governance. Research should recognize the complexity of gender as a phenomenon, highlight resistance to prevention (not only individual but organizational and social) and be able to identify where prevention may be necessary. We have proposed how gender constitutes violence in gymnastics (Barker-Ruchti et al., Citation2020), but more work is needed.

Finally, the lack of explicit focus on non-accidental violence relative to its prevalence in the articles raises concerns about the status of violence in women’s gymnastics research. This may be attributed to researchers’ backgrounds, such as former gymnasts or gymnastics coaches and judges, which could reflect the normalization of violence in gymnastics culture. This observation highlights the advantages of using CIS to critique discourses that guide research fields.

Whilst reading the many articles that came years before the 2019 USA sexual abuse case is disheartening, it strengthens our argument about the need to consider gender as a factor in understanding violence. It is our view that future research should make a conscious effort to be aware of and integrate gender into analyses of gymnastics. We also advocate for an intersectional approach to recognize that gender intersects with other identities, including race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality. In addition, researchers of women’s gymnastics who are cultural insiders should be aware of their oversights regarding non-accidental violence.

Reflections on methodology

Questions of the validity and credibility of this analysis may well be raised. We draw attention to the philosophy of CIS that seeks not reproducibility but to foreground the critical voice and produce a synthesizing argument in our interpretation to offer new insights and empirically valuable questions for future research (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). We have synthesized a sample of papers, and a different team may have selected another selection of articles or produced a different theoretical model. Whilst it is not the aim of a CIS, we have been as transparent as possible with an interpretive and iterative approach that developed over three years. Our analysis offers insight and the rethinking of future research questions on gender and violence in gymnastics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) has shed light on the questions that prompted our inquiry. We have observed that a substantial body of research on women’s gymnastics has overlooked the connection between gender and violence. By employing Risman’s (Citation2018) gender structure theory, we have uncovered the varying understandings and interpretations of gender in the context of violence, sometimes neglecting its relevance as an outcome. Through different disciplinary lenses, we can gain a more nuanced and intersectional understanding of how gender relates to violence in gymnastics. We encourage researchers and practitioners to make a conscious effort to incorporate gender as a central and critical focus and to utilize gender structure theory in their analyses to reveal a diverse range of gendered mechanisms contributing to violence and enable more effective prevention strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. Investigations have been conducted in Australia, Belgium, Germany, New Zealand, Switzerland, The Netherlands, UK, and the USA. These investigations were conducted by independent organizations, such as the Australian Human Rights Commission, law firms, or teams of independent legal professionals, human rights experts, and scientists.

2. In British Gymnastics, over a period of 12 years, 75% of participants were girls under 12 (Whyte, Citation2022).

References

- Annandale, E., Harvey, J., Cavers, D., & Dixon-Woods, M. (2007). Gender and access to healthcare in the UK: A critical interpretive synthesis of the literature. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate & Practice, 3(4), 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426407782516538

- Barker-Ruchti, N., Schubring, A., & Stewart, C. (2020). Gendered violence in women's artistic gymnastics: A sociological analysis. In Routledge handbook of athlete welfare (pp. 57–68).

- Barker-Ruchti, N., & Tinning, R. (2010). Foucault in leotards: Corporeal discipline in women’s artistic gymnastics. Sociology of Sport Journal, 27, 229–250.

- Bekker, S., Ahmed, O. H., Bakare, U., Blake, T. A., Brooks, A. M., Davenport, T. E., Mendonça, L. D. M., Fortington, L. V., Himawan, M., Kemp, J. L., Litzy, K., Loh, R. F., MacDonald, J., McKay, C. D., Mosler, A. B., Mountjoy, M., Pederson, A., Stefan, M. I., Stokes, E., & Vassallo, A. J.… Whittaker, J. L. (2018). We need to talk about manels: The problem of implicit gender bias in sport and exercise medicine. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(20), 1287–1289. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099084

- Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. Yale University Press.

- Bewley, S., McCartney, M., Meads, C., & Rogers, A. (2021). Sex, gender, and medical data. British Medical Journal, 372(735), n735. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n735

- Bjørnseth, I., & Szabo, A. (2018). Sexual violence against children in sports and exercise: A systematic literature review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1477222

- Brackenridge, C., & Fasting, K. (2002). Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: The research context. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 8(2), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600208413336

- Calasanti, T., & King, N. (2015). Intersectionality and age. In J. Twigg & W. Martin (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural gerontology (pp. 193–200). Routledge.

- Cervin, G. (2020, August 4). Girls no more: Why elite gymnastics competition for women should start at 18. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/girls-no-more-why-elite-gymnastics-competition-for-women-should-start-at-18-143182

- Cervin, G. (2021). Degrees of difficulty: How Women’s Gymnastics Rose to prominence and fell from grace. University of Illinois Press.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley, R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

- Eagleman, A. N., Rodenberg, R. M., & Lee, S. (2014). From ‘hollow-eyed pixies’ to ‘team of adults’: Media portrayals of Olympic women’s gymnastics before and after an increased minimum age policy. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 6(3), 401–421.

- Edelman, M., & Pacella, J. M. (2019). Vaulted into victims: Preventing further sexual abuse in US Olympic sports through unionisation and improved governance. Arizona Law Review, 61, 463–504.

- European Commission. (n.d.). What is gender-based violence? Gender-based violence can take different forms and mostly affects women and girls. www.ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/gender-based-violence/what-gender-based-violence_de

- Felipe-Russo, N., & Pirlot, A. (2006). Gender-based violence: Concepts, methods and findings. New York Academy of Sciences, 1087(1), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1385.024

- Fisher, L. A., & Anders, A. D. (2020). Engaging with cultural sport psychology to explore systemic sexual exploitation in USA gymnastics: A call to commitments. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(2), 129–145.

- Forsdike, K., & O’Sullivan, G. (2022). Interpersonal gendered violence against adult women participating in sport: A scoping review. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2116089

- Fortier, K., Parent, S., & Lessard, G. (2020). Child maltreatment in sport: Smashing the wall of silence: A narrative review of physical, sexual, psychological abuses and neglect. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100224

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. University of California Press.

- Hartill, M. (2005). Sport and the sexually abused male child. Sport, Education and Society, 10(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320500254869

- Jacobs, F., Smits, F., & Knoppers, A. (2017). ‘You don’t realise what you see!’: The institutional context of emotional abuse in elite youth sport. Sport in Society, 20(1), 126–143.

- Kerr, R., & Kerr, G. (2020). Promoting athlete welfare: A proposal for an international surveillance system. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.005

- Kirby, S. L., Demers, G., & Parent, S. (2008). Vulnerability/Prevention: Considering the needs of disabled and gay athletes in the context of sexual harassment and abuse. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(4), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671882

- Knoppers, A., & McLachlan, F. (2018). Reflecting on the use of feminist theories in sport management research. In L. Mansfield, J. caudwell, B. Wheaton, & B. Watson (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of feminism and sport, leisure and physical education (pp. 163–179).

- MacDonald, C. A. (2014). Masculinity and sport revisited: A review of literature on hegemonic masculinity and men’s ice hockey in Canada. Canadian Graduate Journal of Sociology and Criminology, 3(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.15353/cgjsc.v3i1.3764

- McFerran, K. S., Garrido, S., & Saarikallio, S. (2016). A critical interpretive synthesis of the literature linking music and adolescent mental health. Youth & Society, 48(4), 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X13501343

- Mountjoy, M. (2019). Only by speaking out can we create lasting change’: What can we learn from the dr Larry Nassar tragedy? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(1), 57–60.

- Mountjoy, M., Brackenridge, C., Arrington, M., Blauwet, C., Carska-Sheppard, A., Fasting, K., Kirby, S., Leahy, T., Marks, S., Martin, K., Starr, K., Tiivas, A., & Budgett, R. (2016). International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121

- Mountjoy, M., Rhind, D. J., Tiivas, A., & Leglise, M. (2015). Safeguarding the child athlete in sport: A review, a framework and recommendations for the IOC youth athlete development model. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(13), 883–886. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094619

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Research on Women’s Health. (n.d.). Sex and gender. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender

- Neves, C. M., Filgueiras Meireles, J. F., Berbert de Carvalho, P. H., Schubring, A., Barker-Ruchti, N., & Caputo Ferreira, M. E. (2017). Body dissatisfaction in women’s artistic gymnastics: A longitudinal study of psychosocial indicators. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(17), 1745–1751.

- Novkov, J. (2019). Law, policy, and sexual abuse in the# MeToo movement: USA gymnastics and the agency of minor athletes. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 40(1), 42–74.

- Pinheiro, M. C., Pimenta, N., Resende, R., & Malcom, D. (2014). Gymnastics and child abuse: An analysis of former international Portuguese female artistic gymnasts. Sport, Education & Society, 19(4), 435–450.

- Risman, B. J. (2004). Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender & Society, 18(4), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265349

- Risman, B. J. (2018). Gender as a social structure. In B. J. Risman, C. M. Froyum, & W. J. Scarborough (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of gender (pp. 19–43). Springer International Publishing.

- Roberts, V., Sojo, V., & Grant, F. (2020). Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.03.001

- Ryan, J. (1996). Little girls in pretty boxes: The making and breaking of elite gymansts and figure skaters. Grand Central Publishing.

- Salim, J., & Winter, S. (2022). “I still wake up with nightmares” the long-term psychological impacts from gymnasts’ maltreatment experiences. Sport, Exercise, & Performance Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000302

- Scarborough, W. J., & Risman, B. J. (2017). Changes in the gender structure: Inequality at the individual, interactional and macro dimensions. Sociology Compass, 11(10), e12515. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12515

- Smits, F., Jacobs, F., & Knoppers, A. (2016). ‘Everything revolves around gymnastics’ how elite athletes and their parents make sense of practices in women’s gymnastics that challenges a positive pedagogical culture. Sports in Society, 20(1), 66–83.

- Stewart, C., & Barker-Ruchti, N. (2021) Bodies of change: Women’s artistic gymnastics in Tokyo. https://olympicanalysis.org/section-3/bodies-of-change-womens-artistic-gymnastics-in-tokyo-2021/

- Stewart, C., Schiavon, L., & Bellotto, M. (2015). Knowledge, nutrition and coaching pedagogy: A perspective from Brazilian Olympic gymnasts. Sport, Education & Society, 22(4), 511–527.

- Stirling, A. E. (2009). Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: Establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(14), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433

- Stirling, A. E., Cruz, L. C., & Kerr, G. A. (2012). Influence of retirement on body satisfaction and weight control behaviors: Perceptions of elite rhythmic gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 24(2), 129–143.

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- United Nations. (1993). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. UN.

- United Nations. (n.d.). International day of the Girl Child 11 October. https://www.un.org/en/observances/girl-child-day

- Weber, J., & Barker-Ruchti, N. (2012). Bending, floating, flirting, flying: A critical analysis of 1970s gymnastics photographs. Sport Sociology Journal, 29(1), 22–41.

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151.

- Whyte, A. (2022). The Whyte review: An independent investigation commissioned by Sport England and UK Sport following allegations of mistreatment within the sport of gymnastics. Sport England. https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2022-08/The%20Whyte%20Review%20Final%20Report%20of%20Anne%20Whyte.pdf?VersionId=fizNx7wABnsdz5GRldCKl6m6bYcIAqBb

- World Health Organisation. (n.d.). Gender and health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1

- Xiao, Y., & Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971