ABSTRACT

Aims

To generate a taxonomy of potentially morally injurious events (PMIE) encountered in veterinary care and develop an instrument to measure moral distress and posttraumatic growth following exposure to PMIE in the veterinary population.

Methods

Development and preliminary evaluation of the Moral Distress-Posttraumatic Growth Scale for Veterinary Professionals (MD-PTG-VP) employed data from veterinary professionals (veterinarians, veterinary nurses, veterinary technicians) from Australia and New Zealand across three phases: (1) item generation, (2) content validation, and (3) construct validation. In Phase 1 respondents (n = 46) were asked whether they had experienced any of six PMIE and to identify any PMIE not listed that they had experienced. In Phase 2 a different group of respondents (n = 11) assessed a list of 10 PMIE for relevance, clarity and appropriateness. In Phase 3 the final instrument was tested with a third group of respondents (n = 104) who also completed the Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT), a measure of posttraumatic stress, and the Stress-Related Growth Scale–Short Form (SRGS-SF) a measure of perceived posttraumatic growth. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated between respondent scores on each of the MD-PTG-VP subscales, the SPRINT, and the SRGS-SF to assess construct validity.

Results

A 10-item taxonomy of PMIE encountered in veterinary care was generated in Phase 1. Items were deemed relevant, clear and appropriate by veterinary professionals in Phase 2. These were included in the developed instrument which measures frequency and impact of exposure to 10 PMIE, yielding three subscale scores (exposure frequency, moral distress, and posttraumatic growth). Assessment of construct validity by measuring correlation with SPRINT and SRGS-SF indicated satisfactory validity.

Conclusions

The MD-PTG-VP provides an informative tool that can be employed to examine professionals’ mental health and wellbeing following exposure to PMIE frequently encountered in animal care. Further evaluation is required to ascertain population norms and confirm score cut-offs that reflect clinical presentation.

Clinical relevance

Once fully validated this instrument may be useful to quantify the frequency and intensity of positive and negative aspects of PMIE exposure on veterinary professionals so that accurate population comparisons can be made and changes measured over time.

Introduction

Potentially morally injurious events (PMIE) are those that carry the potential to elicit psychological distress as a result of a perceived violation of an individual’s ethical or moral code (Crane et al. Citation2013). Also referred to as ethical challenges, Litz et al. (Citation2009) explain that “the event may be a perpetration, witnessing or failing to prevent an act that transgresses moral code”. The specific form of distress (moral distress) triggered by exposure to these events has a similar presentation to traditional posttraumatic stress symptomology (Bryan et al. Citation2016) and encompasses the four symptom clusters of re-experiencing, emotional/behavioural avoidance, negative cognitions/mood, and trauma-related arousal/reactivity outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association Citation2022). A distinguishing feature of moral distress is the emphasis placed on symptoms linked to moral emotions such as shame, guilt and frustration, and less on fear and hypervigilance (Farnsworth et al. Citation2014).

The term “moral distress” is often used interchangeably in the literature with “moral injury”. However, in their discussion of moral stress in military personnel, Grimell and Nilsson (Citation2020) differentiate the two and describe the phenomenon on a trajectory. It is postulated that a moral stressor (PMIE) elicits an acute reaction of psychological tension (moral stress) which can lead to moral distress. If left unresolved, individuals experiencing moral distress may become increasingly unwell and develop more significant and chronic impairment (moral injury). Hence, timely identification and intervention of moral distress is integral in the prevention of moral injury.

Alongside the pathogenic outcomes of moral distress and injury, individuals exposed to PMIE may also experience positive outcomes of posttraumatic growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation1996) distinguish the transformative personal experiences of posttraumatic growth into five domains: openness to new possibilities (e.g. re-prioritising personal aspirations), relating to others (e.g. strengthened interpersonal relationships), personal strength (e.g. enhanced self-efficacy), spiritual change (e.g. strengthened faith) and appreciation of life (e.g. enhanced appreciating the value of life). It is emphasised that moral distress and posttraumatic growth are not mutually exclusive, and both positive and negative outcomes can be experienced following exposure to a PMIE (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation2004).

The relationship between trauma and psychological outcomes has been examined in past research, with interpersonal (i.e. assault, rape) and non-interpersonal trauma (i.e. natural disaster, car accident) being the primary foci of study (Clemens et al. Citation2013; Schleider et al. Citation2021). Comparatively little research has been undertaken examining outcomes of exposure to moral trauma. The subjective nature of trauma and heterogeneous perceptions of potentially traumatic events constrains researchers from identifying a definitive dose–response relationship between trauma exposure and outcomes. This is further highlighted in the examination of moral trauma, with individual moral values creating variation in appraisal of events including PMIE. Significant positive correlations have been observed between years of experience and moral distress in human healthcare professionals (Elpern et al. Citation2005; Dodek et al. Citation2016), suggesting a cumulative effect of exposure on distress. It has also been observed that individuals exposed to multiple traumatic events are likely to experience poorer psychological outcomes (e.g. posttraumatic stress, depressive disorders) than those who experience a single traumatic event (Brewin et al. Citation2000; Green et al. Citation2000; Harvey et al. Citation2016). Although it has been the focus of fewer studies than pathogenic examinations of the dose–response relationship between trauma and outcomes, some research has observed positive outcomes following repeated trauma exposure. Levy-Gigi et al. (Citation2016) found chronically trauma-exposed police officers were able to complete a cognitive paradigm task under both low and high intensity conditions with a similar level of accuracy in each condition. Further, in the high intensity condition, they outperformed a sample of non-trauma exposed civilian individuals. This suggests that in some individuals, frequent exposure to traumatic events may foster the ability for high performance under traumatic conditions. The above study is one of the few examinations of the positive outcomes of chronic/repeated trauma exposure, with most findings relating to outcomes of single-event exposure.

To date, most research relating to PMIE exposure and impacts has been in the context of the defence force (Bryan et al. Citation2016; Williamson et al. Citation2022) and, more recently, human healthcare (Hines et al. Citation2021; Norman et al. Citation2021). Professionals working in the veterinary sector are also exposed to PMIE that are often considered a “part of the job”. Commonly cited PMIE in animal care relate to end-of-life care decisions and euthanasia, such as owners unwilling to euthanise their animals or requesting euthanasia of an animal as a financial or time convenience (Kipperman et al. Citation2018; Quain et al. Citation2021). Professionals have reported being torn between conflicting demands and obligations to their clients, their patients, and the practice they are employed by (Durnberger Citation2020). Occupational roles and statuses may also constrain an individual’s ability to prevent an act they do not agree with from occurring. For example, a veterinary nurse may not agree with the decisions of the surgeon in charge, or existing treatment policies of a clinic may be incompatible with what is considered by staff to be optimal treatment for patients (Lehnus et al. Citation2019). Compounding the impacts of PMIE exposure for professionals are existing occupational stressors and workforce shortages facing the veterinary sector (Connolly et al. Citation2022). This personnel shortage has been compounded by a rise in pet ownership since the emergence of COVID-19 (Animal Medicines Australia Citation2021) and is likely leading to more frequent exposure to PMIE as professionals are working additional hours. In a global sample of veterinary professionals, Quain et al. (Citation2021) found that ethically challenging situations were encountered several times per week. Half of the survey respondents who reported exposure to conflicts between the interests of clients and the interests of their animals rated them as “very” or “maximally” stressful.

Researchers have developed instruments to quantify the impacts of PMIE. These commonly use lists of specific events experienced by those in target occupations and assess the frequency of exposure and impact of each event. While scales have been developed for human healthcare professionals including nurses (Corley et al. Citation2001) and pharmacists (Astbury et al. Citation2017), there is currently no instrument measuring moral distress in veterinary professionals. The development and employment of psychometric instruments tailored to target populations allows for the incorporation of relevant aspects unique to the population being studied, thereby increasing face validity and fostering more meaningful engagement by users (Watson et al. Citation2017). Given the unique PMIE encountered in animal care, it is likely that an instrument comprised of veterinary-specific events and terminology will be more deeply engaged with and thereby yield more accurate results. Additionally, posttraumatic growth and positive outcomes are also largely under-researched in the veterinary profession. The present study represents the development of the first combined instrument measuring both outcomes of moral distress and posttraumatic growth.

The principles guiding the present study in the development of the Moral Distress-Posttraumatic Growth Scale for Veterinary Professionals (MD-PTG-VP) centred on constructing an instrument that accurately reflects the lived experiences of the veterinary population in the current occupational climate. An additional prioritised consideration was ease of administration due to the heavy workloads reported by this population. As such, efforts were made to contain items and responses to the minimum necessary to capture the veterinary experience.

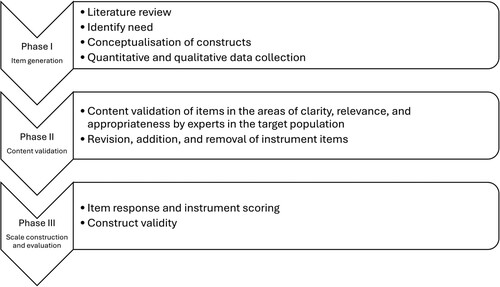

Common criticisms of scale construction in the literature include a lack of thorough psychometric assessment of instrument, poor construct conceptualisation, and a misunderstanding and/or lack of establishing reliability and validity (Morgado et al. Citation2018; Clark and Watson Citation2019). Therefore, the present study was guided by scale construction methodology and recommendations from best practice literature (e.g. Loevinger Citation1957; Boateng et al. Citation2018) and extended across three phases (): (1) conceptualisation, item generation, and development; (2) content validation; and (3) instrument construction and evaluation.

Figure 1. Overview of the phases and steps followed in the development of the Moral Distress-Posttraumatic Growth for Veterinary Professionals (MD-PTG-VP) instrument to measure moral distress and posttraumatic growth following exposure to potentially morally injurious experiences in veterinary professionals.

Therefore, two primary research aims of this study were: to identify and generate a relevant and representative taxonomy of PMIE experienced by veterinary professionals working in Australia and New Zealand (Phase 1); and to develop an instrument to measure frequency of exposure to PMIE, moral distress, and posttraumatic growth in veterinary professionals (Phases 2 and 3).

Materials and methods

Study recruitment

Recruitment for all phases of the study involved email dissemination of survey invitations to veterinary practices and organisations across Australia and New Zealand identified through an online search (terms “veterinary”, “practice”, “organisation”, “Australia”, “New Zealand”). Veterinary professionals were eligible if they were over 18 years of age, were currently practicing as a veterinarian, veterinary nurse, or veterinary technician, and had been doing so for at least 1 year. For all phases of the study, the same recruitment strategy and eligibility criteria applied, participants were provided with the same information sheet including a definition of moral distress and PMIE (see Supplementary Information 1) and consent was stated as being implied at survey submission. Phase 1 invitations were emailed to 100 veterinary practices between February and May 2022.

Data collection for Phase 2 from a separate respondent sample occurred between July and November 2022. It is recommended that potential instrument items be examined and assessed for content validation by both experts and the target population of the instrument (Boateng et al. Citation2018). Therefore, a sample of veterinary professionals were employed (as both experts in the instrument items and as members of the target population) in Phase 2 to assess each item for clarity of wording, and event relevance and appropriateness of terminology. Author KN is a clinical psychologist and ensured that language and terminology relating to the key concepts were accurate and clear.

A final round of data collection from a third separate respondent sample was conducted between May and August 2023. Phase 3 invitations were sent to practices and organisations found in an online search (terms as above) and were disseminated through collegial networks and via advertisement by the Australian Veterinary Association, New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association, Australian and New Zealand Laboratory Animal Association, and Animals Australia.

Approval was sought and received by the Tasmanian Human Research Ethics Committee (S0023759).

Materials

The definition of PMIE coined by Litz et al. (Citation2009) was adopted in item generation as it encapsulates a broad range of situations that corresponds with the heterogeneous experiences encountered in veterinary contexts. Many definitions of moral distress are based in human healthcare (e.g. Wilkinson Citation1989; Corley et al. Citation2001) and subsequently do not incorporate obligations to (human) clients, in addition to animal patients and institutions. Hamric and Blackhall (Citation2007) posited a definition that acknowledges a broader range of constraints and is therefore applicable to veterinary care (“When the practitioner feels certain of the ethical course of action but is constrained from taking that action”). A second definition coined by Kälvemark et al. (Citation2004; “Traditional negative stress symptoms that occur due to situations that involve ethical dimensions and where the healthcare provider feels she/he is not able to preserve all interests and values at stake”) encompasses morally ambiguous events and was also integrated into the present scale development. A decision was made to avoid conceptualisations of both moral distress and posttraumatic growth that explicitly feature components of religion and spirituality. This was done so as not to exclude secular veterinary professionals from engaging with the instrument. The wording of instructions was sufficiently broad as to allow both secular and religious/spiritual interpretation. Tedeschi and Calhoun’s (Citation1996) conceptualisation of posttraumatic growth was employed for this instrument. It was important to distinguish posttraumatic growth from the related concepts of resilience and recovery. In their conceptualisation, Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation2004) emphasise that “[p]osttraumatic growth is not simply a return to baseline – it is an experience of improvement”.

Phase 1 participants were presented with six PMIE frequently discussed in veterinary literature (see Supplementary Information 2) and asked to select those PMIE that they had experienced (if any) in their role as an animal care professional. The second and final question of the survey was a free-text qualitative item asking respondents to identify any PMIE not listed that they had experienced. These two questions intended to capture both PMIE discussed in the literature as well as those not captured in a literature review. Demographic information was not collected in this initial phase of the study.

Phase 2 respondents were asked to review each item of the taxonomy devised in Phase 1 and provide feedback in three domains: relevance, clarity, and appropriateness. Response options for the domain of relevance were in a yes/no format (e.g. “Have you been exposed to this event/situation in your career working as a veterinary professional?”), and options for the domains of clarity and appropriateness were on a three-point Likert scale (see Supplementary Information 3). Space was also provided for respondents to add additional feedback regarding the score they provided in each domain for each item. Demographic information relating to occupation, type of veterinary practice and years of employment in veterinary care was also collected in Phase 2. In line with previous studies developing scales of moral distress in nurses and pharmacists (Corley et al. Citation2001; Astbury et al. Citation2017), data collection was ceased following responses from 11 veterinary professionals (i.e. experts in the field) with little variation in responses. Respondents were from all three occupational groups (veterinarians, veterinary nurses, veterinary technicians) and ranged from 1 to 19 years of experience.

In Phase 3, the final instrument was trialled with the third respondent sample (see Supplementary Information 4 for questionnaire and Supplementary Information 5 for automated scoring spreadsheet). Demographic information was collected relating to respondent gender, occupation, years of experience, and location.

As the three variables of interest comprising the developed instrument (frequency of exposure, moral distress, and posttraumatic growth) are independent of each other, the decision was made to divide the MD-PTG-VP into three subscales yielding three separate scores. The construction of the MD-PTG-VP was guided by the development of established instruments measuring moral distress (Corley et al. Citation2001; Astbury et al. Citation2017), trauma exposure (Wolfe et al. Citation1996), and posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation1996). The final instrument comprised 10 items (each representing a PMIE) with three responses required for each which produced three subscale scores. The optimal number of response points on a Likert scale has been debated but commonly falls between five and seven. Therefore, consistent with similar scales, a 5-point response format was used for each subscale of the MD-PTG-VP. Although the wording used in questions to indicate moral distress and posttraumatic growth (i.e. “negative impact” and “positive impact”) may be broad, they circumvent pigeonholing psychological responses that respondents may not feel fit the criteria of moral distress and posttraumatic growth. It also aligns with conceptualisation of moral distress adopted from Kälvemark et al. (Citation2004) in that moral distress encompasses any negative symptoms elicited through PMIE exposure. The subjective nature of PMIE means an event may be encountered frequently but only elicit mild moral distress, or be encountered on a very rare basis but elicit high levels of distress. As such, the scoring of both the moral distress and posttraumatic growth subscales incorporated frequency of exposure to the event as well as perceived negative or positive impact. This method also acknowledges the impacts of cumulative trauma on professionals. Frequency of exposure to each item (defined as both enacting or witnessing the event) was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = I have never encountered this event to 4 = Daily). Total possible scores range from 0 (not having been exposed to any of the PMIE) to 40 (exposed to each PMIE on a daily basis). If the respondent indicated that they had never been exposed to an event, they were directed to the next PMIE and did not answer additional questions relating to the impacts of that PMIE. The negative (moral distress) and positive (posttraumatic growth) impacts of each event were both measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), with higher scores indicating greater moral distress and posttraumatic growth respectively.

To assess convergent construct validity (i.e. how closely the new instrument is related to existing scales measuring similar constructs), measures of both posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth were employed. The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT; Connor and Davidson Citation2001) is a 10-item measure of posttraumatic stress symptomology. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). As the final two items of the scale relate to perceived efficacy of psychological treatment (e.g. How much better do you feel since beginning treatment?), they were omitted from the present study and the 8-item short form was instead administered. Higher scores on the SPRINT indicate greater posttraumatic stress symptom severity with a suggested cut-off score of 14 warranting further assessment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. The SPRINT was found to have good reliability (internal consistency) in the present study (α = 0.89).

The Stress-Related Growth Scale–Short Form (SRGS-SF; Park et al. Citation1996) was employed as a comparable measure of perceived posttraumatic growth, comprising 15 items that assess positive posttraumatic change in the domains of social relationships, personal resources, coping skills, and outlook on life. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater perceived growth. A reliability coefficient of α = 0.90 was found in the present study, indicating good reliability.

Following completion of each of these surveys, respondents were given the opportunity to enter a draw to receive one of six online gift cards.

Data analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS v.27 (IBM; Armonk, NY, USA) and qualitative data was analysed using NVivo (1.2) (Lumivero; Denver, CO, USA) for all phases of the study. For Phase 1, frequency analysis was conducted to quantify how many respondents had encountered each of the six PMIE and eliminate any events identified as not being relevant. All free-text responses were analysed using thematic analysis and both inductive and deductive coding. Codes were generated for each response and grouped based on similarity of response content. Responses were either combined with one of the six existing PMIE or a new PMIE was created.

Descriptive analysis of demographic variables was conducted in Phase 2. Responses were examined independently by the authors for each of the three rated domains of relevance, clarity, and appropriateness. If applicable, item wording was altered based on respondent feedback.

In Phase 3, descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables, the three subscales of the MD-PTG-VP, the SPRINT, and the SRGS-SF. A total frequency of exposure score was calculated by summing frequency of exposure scores of each PMIE. Moral distress subscale scores were calculated by multiplying a respondent’s frequency of exposure score with the summed negative impact score and dividing by 10 (possible score range 0–160). Posttraumatic growth subscale scores were calculated using the same scoring system as positive impact scores. Frequencies were also calculated for responses of exposure frequency, negative impact, and positive impact for each PMIE. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated between respondent scores on each of the subscales of the MD-PTG-VP, the SPRINT, and the SRGS-SF to assess construct validity.

Results

In Phase 1, 50 responses from veterinary professionals were submitted and 48 were analysed (see Supplementary Table 1 for frequency tabulations of experiences with each PMIE). Two responses could not be analysed due to the ambiguity of response content and responses that reflected misunderstanding of survey questions and were therefore excluded from any analysis. The PMIE most frequently experienced by respondents was Performing euthanasia due to owner inability to afford treatment (experienced by 95.1% of respondents). All respondents indicated that they had encountered at least one of the six listed PMIE. Qualitative analysis of free-text responses provided guidance for adjustments of existing PMIE (e.g. more detail provided in wording) in addition to identifying four additional PMIE not listed. Therefore, the final taxonomy generated comprised 10 PMIE encountered by the Phase 1 sample ().

Table 1. Final taxonomy of potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIE) encountered in veterinary care generated in Study Phase I of a study in which veterinary professionals (n = 48) were asked which of six PMIE they had experienced and suggested additional PMIE.

Data from 11 veterinary professionals were collected and analysed in Phase 2 (demographic variables displayed in ). All PMIE were deemed relevant by at least half of the sample and therefore all 10 were retained in the taxonomy. After reviewing responses for scoring in each domain, minor revisions were made to three PMIE following feedback suggesting that provision of more examples would enhance clarity (e.g. “This may include prolonging the life of a terminally ill animal, providing treatment that benefits the owner more so than the patient [for example, treatment that only serves to keep a pet alive due to an owner not being ‘ready’ for their passing]” was added to the PMIE: “Providing/witnessing excessive treatment that does not improve patient quality of life [including cosmetic/aesthetic procedures]”). There were no instances of conflicting feedback, and all responses were regarded as unambiguous. Therefore, no conflict resolution was required between the authors and all responses were integrated into the existing PMIE taxonomy.

Table 2. Demographic data for veterinary professionals (n = 11) included in Study Phase 2 of a study to develop an instrument to measure moral distress and posttraumatic growth following exposure to potentially morally injurious events, in veterinary professionals. Phase 2 comprised content validation of items included in the instrument.

A total of 104 surveys were returned and included sufficient data for analysis (at least 70% of survey items) in Phase 3, with one respondent being excluded due to reporting an occupation outside the inclusion criteria (see for demographic variables). Respondents had a mean of 14.2 (SD 10.74, min 1, max 46) years of experience.

Table 3. Demographic data for veterinary professionals (n = 103) included in Study Phase 3 of a study to develop an instrument to measure moral distress and posttraumatic growth following exposure to potentially morally injurious events, in veterinary professionals. Phase 3 comprised assessment of convergent construct validity of the instrument.

The PMIE encountered most frequently by professionals was Financial/time expectations from management or patient owner impeding quality of patient care with 24.3% of respondents reporting daily exposure to this event. The PMIE encountered by the most respondents was Performing/witnessing euthanasia due to owner inability to afford treatment (experienced by 99.1% of respondents), followed by Exposure to cases of cruelty and neglect (97.1%), and Owners’ unwilling to euthanise their animal despite poor quality of life (96%). The PMIE eliciting the most moral distress (endorsed by 66% of respondents as “Extremely” or “Quite a bit”) was Exposure to cases of animal cruelty or neglect. Owners’ unwilling to euthanise their animal despite poor quality of life was the PMIE that elicited the most posttraumatic growth indicators, with 7.9% of respondents reporting “Quite a bit” or “Extremely” when asked the extent of posttraumatic growth elicited.

Correlational analysis () revealed strong and weak correlations between the frequency of PMIE exposure and that of moral distress (in accordance with Dancey and Reidy Citation2007; Funder and Ozer Citation2019), and posttraumatic growth, respectively. A weak correlation was also observed between moral distress and posttraumatic growth. A moderate correlation was observed between the moral distress subscale of the MD-PTG-VP and the SPRINT, while the posttraumatic growth subscale was weakly correlated with the SRGS-SF.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlation co-efficients for the Moral Distress-Posttraumatic Growth for Veterinary Professionals (MD-PTG-VP) subscales, the Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) and the Stress-Related Growth Scale–Short Form (SRGS-SF) administered to veterinary professionals (n = 102).

Discussion

The current study extended across three phases and had two primary research aims: to identify and generate a relevant and representative taxonomy of PMIE experienced by veterinary professionals working in Australia and New Zealand, and to develop an instrument to measure frequency of exposure to PMIE, moral distress, and posttraumatic growth in this population.

The results of Phase 1 provide a reflection of the morally stressful experiences of veterinary professionals as endorsed by those with lived experience. These results confirm exposure to events commonly discussed in the literature (e.g. financial restraints preventing the provision of required care, convenience euthanasia; Quain et al. Citation2021; Williamson et al. Citation2022) by professionals currently working in Australia and New Zealand. Results also drew attention to additional issues and events not as commonly discussed, such as interactions with owners who are unwilling to surrender ownership of their animals when necessary for the animal’s wellbeing, and exposure to cases of animal cruelty or neglect. Qualitative data from respondents spoke to the heterogeneous experiences of professionals. An interesting finding in these results was the role of the respondent in the PMIE reported. A common theme of events frequently discussed in the literature centres on direct participation of participants in behaviours that elicit moral distress. In contrast, the events less examined in the literature that surfaced through analysis of qualitative data often involved bearing witness to events, rather than active participation. These findings suggest that the focus needs to be expanded to include not only professionals who actively participate in PMIE but also those who experience secondary exposure through observation. In examinations of general posttraumatic stress, some researchers argue that witnessing traumatic events can be more distressing for individuals and elicit more chronic PTSD symptomology than being a recipient of, or actively involved in, a traumatic event (Warren et al. Citation2009; Atwoli et al. Citation2015). Therefore, veterinary professionals bearing witness to PMIE such as cases of animal cruelty, or those who are required to assist in objectionable euthanasia (but not actually perform the procedure) may be at increased risk of pathological outcomes.

The most commonly reported PMIE of the final 10-item taxonomy employed in Phase 3 (euthanasia due to inability to afford treatment, exposure to neglect/cruelty, and owners unwilling to euthanise despite poor quality of life) are comparable to the findings of occupational stressors reported in other veterinary samples (Andela Citation2020; Quain et al. Citation2021). Self-schemas held by those working in the profession may also play a role in distress if they are incompatible with PMIE encountered. Self-stigma has been highlighted as a barrier to seeking help in professionals who identify with the role of helper/healer of animals (Clough et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, it is likely that the most frequently encountered PMIE (financial/time expectations from management or patient owner impeding quality of patient care) would elicit stress owing to high trait perfectionism reported to be common among those studying and working in the veterinary profession (Bartram and Baldwin Citation2010; Crane et al. Citation2015).

Although culling research animals was only reported to be experienced by 5% of respondents in Phase 1, this is likely a reflection of the proportion of respondents working in research. As demographic data was not collected for this phase of the study, this cannot be confirmed. However, in a recent Australia-wide survey of veterinary professionals, 1% reported working in a laboratory setting and 5% reported working in a university/research setting (Australian Veterinary Association Citation2019). Similar proportions of professionals employed in research/laboratory settings in comparison to clinical settings (i.e. companion animal, equine) have been observed in a 2018–19 workforce survey of professionals working in New Zealand (New Zealand Veterinary Association Citation2020). This is still a valuable PMIE for investigation due to the nature of this line of veterinary work. Ahn et al. (Citation2022) describe the strong human–animal bonds fostered between veterinary carers and animals involved in research. These bonds are likely to place increased psychological strain on professionals at the conclusion of an experiment when they are required to euthanise the animals for which they have been providing healthcare and husbandry. More recently, Thurston et al. (Citation2021) reported the poor psychological outcomes elicited in research veterinarians who were required to euthanise healthy animals following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and related movement restrictions imposed. Therefore, a decision was made by the authors to absorb the event into the theme of Euthanising animals for a non-medical reason in order to retain the event in the taxonomy while limiting the potential for skewed scoring in the final instrument.

The large range of scores (1.40–104) reflects heterogeneous experiences of moral distress in this respondent sample. Future research is required to ascertain norms and identify clinical cut-off scores for low, moderate and high levels of moral distress and posttraumatic growth. Until such time as cut-off scores are confirmed, it would also be valuable to examine MD-PTG-VP scores at the specific PMIE level to examine the events that most elicit distress and comparing these to an individual’s workload and frequency of exposure. For example, examining how often professionals are exposed to PMIE reported to be highly morally distressing could help inform case rotations to avoid overexposure and subsequent distress. The PMIE reported to elicit the most moral distress was Exposure to cases of animal cruelty or neglect. This finding is consistent with previous literature reporting that exposure to animal cruelty negatively impacts mental health and quality of life (Strand et al. Citation2012; Musetti et al. Citation2020).

The PMIE eliciting the most posttraumatic growth indicators (Owners unwilling to euthanise their animal despite poor quality of life) draws parallels with the posttraumatic growth domain of “relating to others” posited by Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation1996). These results suggest that despite the potentially traumatic nature of being exposed to an animal facing reduced quality of life, professionals may be experiencing an enhanced appreciation of owners’ circumstances and points of view. Enhanced communication skills and self-confidence are both discussed as common posttraumatic growth indicators in the literature (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation1996; Muldoon et al. Citation2023). In the context of the present study, professionals may develop the confidence to voice their opinions to animal owners regarding the patient’s quality of life or gain knowledge of how to navigate similar situations in future instances. Nine respondents reported a total posttraumatic growth score of 0. One possible reason for this is veterinary professionals being unfamiliar with the notion of posttraumatic growth and the idea of appraising a morally traumatic event as eliciting positive effects. Exploration of other individual and organisational factors influencing experience of posttraumatic growth (e.g. perceived support) is a valuable area for future research.

In all phases of the present study, every respondent indicated exposure to at least one of the PMIE, further highlighting the need to investigate PMIE and their impacts on mental health and wellbeing of professionals in the veterinary population. The PMIE most frequently encountered (Financial/time expectations from management or patient owner impeding quality of patient care) is consistent with the findings of Quain et al. (Citation2021). They reported that exposure to ethically challenging situations in the veterinary profession has increased to several exposures per week since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The correlations observed between frequency of exposure and moral distress, and frequency of exposure and posttraumatic growth, indicate a dose–response relationship between the variables. The strong correlation with moral distress echoes findings of cumulative trauma exposure eliciting poorer psychological outcomes than single event exposure (Brewin et al. Citation2000; Green et al. Citation2000) and supports the notion that greater exposure to moral trauma is likely to result in greater severity of moral distress symptomology.

The relationship observed between exposure frequency and posttraumatic growth also adds promising evidence to a modest literature base of a potential dose–response relationship between exposure and positive impacts on individuals.

Construct validity analyses of the MD-PTG-VP indicate a moderate relationship between moral distress and posttraumatic stress. Although various thresholds have been suggested, convergent validity is generally accepted at a correlation of 0.50 or higher (Abma et al. Citation2016). Therefore, it was concluded that the moral distress and posttraumatic growth subscales of the instrument had good and weak construct validity respectively.

The limitations of the present study highlight important avenues for future research. Mainly, further evaluation of the MD-PTG-VP with a larger sample needs to be undertaken to confirm reliability and validity of data yielded. Establishing temporal stability and discriminant validity of the instrument are recommended as valuable in further consolidating data validity. As discussed above, further validation in various veterinary subgroups is required to establish cut-off scores that correspond with low, moderate, and high symptom severity and presentation. Given the reported relationship between moral distress and staff attrition or intention to leave in both veterinary and human healthcare (Arbe Montoya et al. Citation2021; Nazarov et al. Citation2024), the relationship between MD-PTG-VP scores and intention to leave the profession would provide insight to managing the staffing shortage in veterinary care. Despite following guidelines of similar studies and best practice literature, the sample sizes of each study phase can be viewed as modest in comparison to other instrument development studies. These sample sizes were due in part to pragmatism, but also with the workload burden of the research population in mind. Over recent years, there has been a proliferation of research examining this population experiencing a staffing shortage (Connolly and Norris Citation2024). Therefore, it is possible that veterinary professionals are experiencing survey fatigue and do not have ample time to engage in multiple studies. In consideration of the time limitations of veterinary professionals, it would benefit research progress to employ the same instrument to ascertain vital population norms, facilitate ease of sub-population comparisons, and assess temporal changes in symptomology following intervention.

This instrument potentially provides an important tool to assess exposure to events that can precipitate and perpetuate symptoms of psychopathology. Without employment of such an instrument, symptoms may not be linked to the (often recurring) cause, resulting in erroneous treatment that is not trauma-informed. The PMIE taxonomy generated in Phase 1 can also be used independently of the instrument by organisations to examine types of events that employees are encountering in their occupational duties, and thereby inform organisation-level interventions (i.e. prevention of exposure to PMIE through event elimination and exposure reduction), as well as appropriate support and training to enhance staff recruitment, retention, wellbeing, and satisfaction.

Conclusion

The current study has presented the first instrument to measure moral distress and posttraumatic growth tailored to the veterinary context. Further evaluation is recommended to strengthen reliability and validity estimates and identify scoring cut-off values. Quantifying both the frequency and intensity of positive and negative impacts of PMIE exposure on veterinary professionals has a range of benefits including identification of professionals experiencing moral distress, acknowledging and observing the positive outcomes that can be elicited through moral trauma exposure, and assessing intervention effectiveness. Once fully validated, this instrument should be widely and uniformly adopted to enable accurate population comparisons and measure changes over time. The impacts of moral distress and injury on the individual, workplace, and the profession suggest that more focus should be placed on PMIE encountered in veterinary care and identifying professionals experiencing pathogenic outcomes following exposure. Given the high frequency of PMIE exposure reported, fostering salutogenic outcomes of posttraumatic growth should also be considered a priority in enhancing the wellbeing of professionals in this population.

Supplemental Material 2

Download MS Excel (16.4 KB)Supplemental Material 1

Download PDF (238 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Angela Martin for her assistance with reviewing and editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abma IL, Rovers M, van der Wees PJ. Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Research Notes 9, 226, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2034-2

- Ahn N, Park J, Roh S. Mental stress of animal researchers and suggestions for relief. Journal of Animal Reproductive Biotechnology 37, 13–6, 2022. https://doi.org/10.12750/JARB.37.1.13

- *American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision. 5th Edtn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Andela M. Burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideations among veterinarians: development and validation of the Veterinarians Stressors Inventory. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 37, 48–55, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.02.003

- *Animal Medicines Australia. Pets and the Pandemic: A Social Research Snapshot of Pets and People in the COVID-19 Era. Animal Medicines Australia, Barton, ACT, Australia, 2021

- Arbe Montoya AI, Hazel SJ, Matthew SM, McArthur ML. Why do veterinarians leave clinical practice? A qualitative study using thematic analysis. Veterinary Record 188, e2, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.2

- Astbury JL, Gallagher CT, O’Neill RC. Development of a tool to measure moral distress in community pharmacists. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 39, 156–64, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0413-3

- Atwoli L, Platt J, Williams DR, Stein DJ, Koenen KC. Association between witnessing traumatic events and psychopathology in the South African Stress and Health Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 50, 1235–42, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1046-x

- *Australian Veterinary Association. Australian Veterinary Workforce Survey 2018. Australian Veterinary Association, Brunswick, VIC, Australia, 2019

- Bartram DJ, Baldwin DS. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: a structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Veterinary Record 166, 388–97, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.b4794

- Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Frontiers in Public Health 6, 149, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68, 748–66, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.748

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Green BA, Etienne N, Morrow CE, Ray-Sannerud B. Measuring moral injury: psychometric properties of the Moral Injury Events Scale in two military samples. Assessment 23, 557–70, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115590855

- Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: new developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychological Assessment 31, 1412–27, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000626

- Clemens SL, Berry HL, McDermott BM, Harper CM. Summer of sorrow: measuring exposure to and impacts of trauma after Queensland’s natural disasters of 2010–2011. Medical Journal of Australia 199, 552–5, 2013. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja13.10307

- Clough BA, March S, Leane S, Ireland MJ. What prevents doctors from seeking help for stress and burnout? A mixed-methods investigation among metropolitan and regional-based Australian doctors. Journal of Clinical Psychology 75, 418–32, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22707

- Connolly CE, Norris K. Measuring mental ill-health in the veterinary industry: a systematic review. Stress & Health e3382, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3382

- Connolly CE, Norris K, Martin A, Dawkins S, Meehan C. A taxonomy of occupational and organisational stressors and protectors of mental health reported by veterinary professionals in Australasia. Australian Veterinary Journal 100, 367–76, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.13167

- Connor K, Davidson J. SPRINT: a brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16, 279–84, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200109000-00005

- Corley MC, Elswick RK, Gorman M, Clor T. Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. Journal of Advanced Nursing 33, 250–6, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2001.01658.x

- Crane MF, Bayl-Smith P, Cartmill J. A recommendation for expanding the definition of moral distress experienced in the workplace. Australasian Journal of Organisational Psychology 6, e1, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/orp.2013.1

- Crane MF, Phillips JK, Karin E. Trait perfectionism strengthens the negative effects of moral stressors occurring in veterinary practice. Austalian Veterinary Journal 93, 354–60, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12366

- *Dancey C, Reidy J. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology. Pearson Education, Harlow, UK, 2007

- Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, Ayas N, Reynolds SC, Keenan SP, Hamric A, Rodney P, Stewart M, Alden L. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. Journal of Critical Care 31, 178–82, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.10.011

- Durnberger C. Am I actually a veterinarian or an economist? Understanding the moral challenges for farm veterinarians in Germany on the basis of a qualitative online survey. Research in Veterinary Science 133, 246–50, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.029

- Elpern EH, Covert B, Kleinpell R. Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care 14, 523–30, 2005. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2005.14.6.523

- Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma JA, Walser RB, Currier JM. The role of moral emotions in military trauma: implications for the study and treatment of moral injury. Review of General Psychology 18, 249–62, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000018

- Funder DC, Ozer DJ. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2, 156–68, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

- Green BL, Goodman LA, Krupnick JL, Corcoran CB, Petty RM, Stockton P, Stern NM. Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13, 271–86, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007758711939

- Grimell J, Nilsson S. An advanced perspective on moral challenges and their health-related outcomes through an integration of the moral distress and moral injury theories. Military Psychology 32, 380–8, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2020.1794478

- Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Critical Care Medicine 35, 422–9, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D

- Harvey SB, Milligan-Saville JS, Paterson HM, Harkness EL, Marsh AM, Dobson M, Kemp R, Bryant RA. The mental health of fire-fighters: an examination of the impact of repeated trauma exposure. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 50, 649–58, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415615217

- Hines SE, Chin KH, Glick DR, Wickwire EM. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 488, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020488

- Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, Westerholm P, Arnetz B. Living with conflicts – ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Social Science and Medicine 58, 1075–84, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00279-X

- Kipperman B, Morris P, Rollin B. Ethical dilemmas encountered by small animal veterinarians: characterisation, responses, consequences and beliefs regarding euthanasia. Veterinary Record 182, 548, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.104619

- Lehnus KS, Fordyce PS, McMillan MW. Ethical dilemmas in clinical practice: a perspective on the results of an electronic survey of veterinary anaesthetists. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 46, 260–75, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaa.2018.11.006

- Levy-Gigi E, Richter-Levin G, Okon-Singer H, Keri S, Bonanno GA. The hidden price and possible benefit of repeated traumatic exposure. Stress 19, 1–7, 2016. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2015.1113523

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review 29, 695–706, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Loevinger J. Objective tests as instruments of psychological theory. Psychological Reports 3, 635–94, 1957. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.3.7.635-694

- Morgado FFR, Meireles JFF, Neves CM, Amaral ACS, Ferreira MEC. Scale development: ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 30, 3, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

- Muldoon OT, Nightingale A, Lowe R, Griffin SM, McMahon G, Bradshaw D, Borinca I. Sexual violence and traumatic identity change: evidence of collective post-traumatic growth. European Journal of Social Psychology 53, 1372–82, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2979

- Musetti A, Schianchi A, Caricati L, Manari T, Schimmenti A. Exposure to animal suffering, adult attachment styles, and professional quality of life in a sample of Italian veterinarians. PLoS One 15, e0237991, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237991

- Nazarov A, Forchuk CA, Houle SA, Hansen KT, Plouffe RA, Liu JJW, Dempster KS, Le T, Kocha I, Hosseiny F, et al. Exposure to moral stressors and associated outcomes in healthcare workers: prevalence, correlates, and impact on job attrition. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 15, 2306102, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2306102

- *New Zealand Veterinary Association. New Zealand Veterinary Association Workforce Report 2018–19. New Zealand Veterinary Association, Wellington, NZ, 2020

- Norman SB, Feingold JH, Kaye-Kauderer H, Kaplan CA, Hurtado A, Kachadourian L, Feder A, Murrough JW, Charney D, Southwick SM, et al. Moral distress in frontline healthcare workers in the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: relationship to PTSD symptoms, burnout, and psychosocial functioning. Depression and Anxiety 38, 1007–17, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23205

- Park C, Cohen L, Murch R. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64, 71–105, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x

- Quain A, Mullan S, McGreevy PD, Ward MP. Frequency, stressfulness and type of ethically challenging situations encountered by veterinary team members during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 8, 647108, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.647108

- Schleider JL, Woerner J, Overstreet C, Amstadter AB, Sartor CE. Interpersonal trauma exposure and depression in young adults: considering the role of world assumptions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36, 6596–620, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518819879

- *Strand E, Poe B, Lyall S, Yorke J, Nimer J, Allen E, Nolen-Pratt T. Veterinary social work practice. In: Dulmus C (ed). Social Work Fields of Practice: Historical Trends, Professional Issues and Future Opportunities. Pp 245–72. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9, 455–71, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry 15, 1–18, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Thurston SE, Chan G, Burlingame LA, Jones JA, Lester PA, Martin TL. Compassion fatigue in laboratory animal personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Association of Laboratory Animal Science 60, 646–54, 2021. https://doi.org/10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-21-000030

- Warren JI, Loper AB, Komarovskaya I. Symptom patterns related to traumatic exposure among female inmates with and without a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 37, 294–305, 2009

- Watson B, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Broadbent J, Skouteris H. Development and validation of a tailored measure of body image for pregnant women. Psychological Assessment 29, 1363–75, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000441

- Wilkinson JM. Moral distress: a labor and delivery nurse’s experience. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 18, 513–9, 1989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1989.tb00503.x

- Williamson V, Murphy D, Greenberg N. Experiences and impact of moral injury in UK veterinary professional wellbeing. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 13, 2051351, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2022.2051351

- *Wolfe J, Kimerling R, Brown PJ, Chrestman KR, Levin K. Psychometric review of the Life Stressor Checklist-Revised. In: Stamm BH (ed). Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Pp 198–201. Sidran Press, Lutherville, MD, USA, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1037/t04534-000

- *Non-peer-reviewed