ABSTRACT

Ritual practices as behavior, and the cognitive acknowledgment of life and death, foster a depth in social identity, collective social memory, and a societal worldview. This paper outlines the evidence of Early Bronze Age burial practices in northwestern Iran to discuss the newly discovered chamber tombs at Kohne Tepesi within the broader context of mortuary practices during the middle and last part of the 3rd millennium b.c. The findings from Kohne Tepesi support the idea that, at least for parts of Kura-Araxes society, burial rites and commemoration of the dead played a crucial role in their worldview. Furthermore, this site demonstrates that the changes in symbolic practices and social behavior during the Early Kurgan period were not spontaneous but rooted in the last phases of the Kura-Araxes period and that the perceptions of earlier traditions had been conserved in long-term social memory.

Introduction

Death and the world of the afterlife have been enigmatic features of human societies from the dawn of prehistory. The awareness of mortality makes us human, throughout thousands of years of the experience of death. In some periods, the deceased were simply buried under the floors of the home or extramurally, without offerings, grave goods, or any sign of commemoration (Laneri Citation2007, Citation2018). Other societies, however, enacted burial as a ritualistic performance, materializing a “non-being” to memorialize the deceased. In doing so, the burial became “a stage of active memory,” attaching a physicality to the social identity of a person (Robb Citation2007, 292). Such a performance, exhibited by monumental structures, offerings, or sacrifices, was certainly not spontaneous but would have been a tradition rooted in the collective memory of a society and a part of their experience of “being.”

Across different traditions, there are different ritual behaviors, but even inside one tradition, a variety of patterns may be recognized. These behaviors illustrate interconnected cultural networks and relationships among members of a society and their descendants, as well as a society’s concept of life and death (Hanks Citation2002, 359). Thus, we believe that burial customs, graves, and material markers are not a static showcase of social structures or merely the social position of the deceased individual. Rather, they embody a dynamic interplay among the living members of society, driven by the attitudes and beliefs framed by their perceptions of death (Hanks Citation2002, 359).

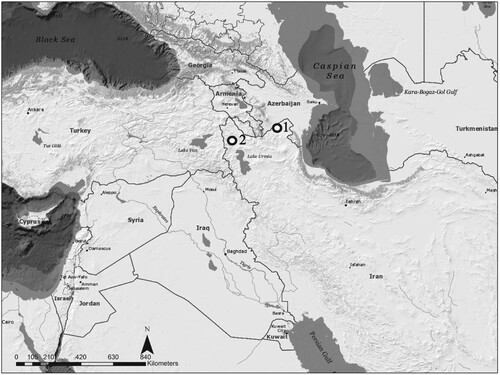

As Chesson stated (Citation2001, 101), when we consider mortuary practices as a part of the process of the creation of social memories, we must then go beyond the description of how they disposed of their dead and begin to consider what their metaphysical world may have been (Smith Citation2019). With this in mind, our archaeological inquiry embarks on a journey to the late Early Bronze Age site of Kohne Tepesi in the Khoda Afarin Plain in the southern basin of the Araxes River in Iran (). The recent excavations at this site have revealed for the first time not only Kura-Araxes (KA) and post-Kura-Araxes burials (Early Kurgan period and Martqopi-Bedeni tradition) but also new types of underground mudbrick chamber tombs, shedding new light on the funerary practices of the Early Bronze Age societies of northwestern Iran and expanding our understanding of their complex cultural and social dynamics.

During the middle of the 4th and 3rd millenniums b.c., the KA cultural tradition, practiced by the inhabitants of the southern Caucasus, involved a characteristic ritual for burying their dead. Within the framework of this ritual, variations in burial customs were practiced across the regions inhabited by the KA, even within a single site (Poulmarc’h Citation2014; Poulmarc’h and Le Mort Citation2016). The migration of parts of KA society in the last part of the 4th millennium b.c. and the resulting diaspora, however, left behind very little evidence of mortuary practices, despite dense settlement distribution. Northwestern, western, and central Iran and northeastern Anatolia as far as the southern Levant are areas that, during the 3rd millennium b.c., members of the KA society migrated to, which we consider to be their diaspora (Maziar Citation2023). Arslantepe’s royal tomb, despite not being directly related to the KA diaspora, represents one of the rare contemporaneous funerary sites outside of the KA core area.

Later, during the middle of the 3rd millennium b.c., when KA settlements were abandoned, a new burial custom known as Early Kurgan (or known as the Martqopi and Bedeni traditions), flourished all along the southern Caucasus. Burying the deceased inside a kurgan was, itself, not a new practice, but the new ritual behavior and burial custom had a different setting that differentiated it from the earlier Chalcolithic or KA burials. Sagona suggested that we are, therefore, presented with crucial changes in symbolic practices and social behavior that appeared around 2500 b.c. (Sagona Citation2004, 480).

In this article, we argue that evidence of behavioral changes existed even earlier, from the final phases of the KA period, based on our new findings from Kohne Tepesi. Furthermore, this article aims to showcase the importance of mortuary rituals in the interpretation of KA and Early Kurgan collective social memory. To provide a comprehensive context, we will begin by reviewing the existing data on mortuary practices among KA and post-KA groups in their core regions. This contextual foundation will pave the way for a detailed examination of the mortuary practices at Kohne Tepesi.

Kura-Araxes and Post-Kura-Araxes Funerary Traditions in the Southern Caucasus: The Archaeological Setting

During the 3rd millennium b.c. in the southern Caucasus, various types of burial structures were present. Kalantaryan, in her study of about 60 Early Bronze Age burials in Armenia, categorized the KA burials into 21 main types (Kalantaryan Citation2007, 72). These findings, however, did not also allow for the distribution and the frequency of each type to be mapped. Sagona (Citation2004) and, later, Palumbi (Citation2008a) categorized the KA burials into three main types: earth pits, stone-lined cists, and horseshoe-shaped tombs. Poulmarc’h was the first to explore the entirety of the southern Caucasus and studied 111 KA sites with burials (Poulmarc’h Citation2014; Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014). She not only provided a general typology of KA burials but also attempted to show the distribution of each type in the southern Caucasus. Following her studies, KA burials may be categorized into six main types: 1) cists, 2) stone-lined graves, 3) horseshoe-shaped tombs, 4) pit graves that are not associated with any structure, 5) pit tombs that were covered by a stone pile on the surface, and 6) kurgans. Her study area, while extensive, has, however, focused just on the core area of the KA tradition, and it remains to be determined whether the KA burials in the diaspora also correspond to these typologies.

Based on Poulmarc’h’s studies, certain burial types are associated with specific regions: for instance, pit tombs have been mostly uncovered in Georgia, and kurgans are only present in Azerbaijan. Stone-lined graves have been found extensively throughout the southern Caucasus (Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014, 239). Cist burials have been found at a few sites dated to KA I (3500–3000/2900 b.c.) and II (3000/2900–2700/2600 b.c.) and have mostly been found in Armenia (Elar) and Georgia (Koda), suggesting that they originated in these regions (Poulmarc’h Citation2014, 233, fig. 3A). In Kvemo Kartli in Georgia, there are mainly stone cist and horseshoe-shaped graves that are dated to KA I and II (Poulmarc’h Citation2014, 234–235; Poulmarc’h and Le Mort Citation2016). The Shida-Kartli province in Georgia has provided the most published information on KA burials (Rova Citation2014, Citation2018). No KA I burials are reported from Shida-Kartli, and most of the burials date to KA II, with some belonging to KA III (2700/2600–2450 b.c.). They are mainly stone-lined pit graves in rectangular or oval forms covered by stones (Puturidze and Rova Citation2012; Rova Citation2018). Wooden roof structures are rarely seen in Shida-Kartli (Puturidze and Rova Citation2012). Pit burials have been found in all KA phases, as well as from the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, and may contain either one or several individuals (Jalabadze and Palumbi Citation2008; Poulmarc’h Citation2014, 236).

Although kurgans have been found across different regions of the southern Caucasus, they occur predominantly in Azerbaijan and are often collective burials (Laneri, Celka, and Palumbi Citation2019). Many individual burials have been found, as well, and sometimes both forms coexist in the same cemetery (Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014, 237, fig. 7B). In western Azerbaijan, we also see more examples of dromos architecture with an entrance. It is assumed that these types of tombs were intentionally set on fire once all the available burial places were filled and the tomb fell out of active use (Jalilov Citation2018). The recently excavated KA kurgans in this area, such as Uzun Rama and Mentesh Tepe, have provided new information on this feature. Uzun Rama is dated to the first phase of the KA period (3600–3100 b.c.) and includes collective burials of varying constructions.

The collective burials are mainly in cist tombs and may represent nuclear or extended families (Palumbi Citation2016, 23). However, we are not certain if the deceased inside a collective burial were immediate family members or if they belonged to the same general kin group. Burying the dead in a particular shaft tomb and repeating this process for multiple individuals supports, at the very least, the idea that those interred belonged to a social group that used the same tomb for their dead over a continuous period and that this constant burial practice itself “creates an identity and reinforces social memories” (Chesson Citation2001, 109).

Animal offerings in KA mortuary contexts are scarce, although they are common in the kurgans of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. In Samshvilde II during the KA period, the remains of domestic animal bones were found inside some cists (Palumbi Citation2008b, 162). Another case is the cemetery of Talin dated to KA I (Hovsepyan and Mnatsakanyan Citation2011, 27). Tomb no. 7 at this site contains the remains of eight humans and the skeletal remains of 10 sheep and goats. In the single burials of Amiranis Gora in southeastern Georgia, bovine bones have been discovered, which were “presumably sacrificed on the occasion of the funerary ritual” (Palumbi Citation2008b, 141).

After the KA period, during the middle and late 3rd millennium b.c., most kurgans are attributed to the Martqopi and Bedeni traditions, during what is known as the Early Kurgan period. There is not yet a clear definition of the Martqopi and Bedeni traditions, despite some criteria that conceptualize and distinguish these two traditions having been identified (Bertram Citation2003; Carminati Citation2014, Citation2017; Rova Citation2018). By some interpretations, Martqopi is earlier than Bedeni and overlaps with the final stages of the Late KA period (Carminati Citation2017, 182). There is scant evidence of Bedeni settlements, which have so far only been found in Berikldeebi (Carminati Citation2017, 177), Khashuri Natsargora (pits) (Puturidze and Rova Citation2012; Rova Citation2018), and in Rabati (Bedianashvili et al. Citation2019). Other scholars argue, however, that it is instead the Late KA period that overlaps with the Early Kurgan tradition. Against this backdrop, our latest findings at Kohne Tepesi seem to introduce a new type or subtype of burial construction that has not been reported elsewhere.

Kura-Araxes and Post-Kura-Araxes Funerary Practices: A View from Iran

As previously described, there is a considerable amount of data on the funerary practices of the KA culture in their core area. In contrast, there is, however, a striking lack of evidence of funerary rites among the areas inhabited by the subsequent KA diaspora.

The earliest evidence of kurgans in Iran was found south of the Urmia Lake. The Se Girdan kurgans and 11 tumuli are the only known sites on the plain of Lake Urmia that date to the 4th millennium b.c. (Muscarella Citation2003, 125). During the past decade, however, recent archaeological projects in the southern part of the Araxes River basin have revealed hundreds of kurgans, providing a rich new opportunity to study the mortuary behaviors from this time period (Iravani ghadim Citation2013; Iravani ghadim and Beikzadeh Citation2018; Kazempour and Niknami Citation2017). All of these kurgan sites are, however, later than Se Girdan and date to the 2nd millennium b.c.

During the last few decades, excavations at Kohne Tepesi and later at Kohne Shahar (Alizadeh, Eghbal, and Samei Citation2015) have revealed the first evidence of KA and post-KA burials in Iran. At Kohne Shahar, a cemetery is located outside a fortified citadel and residential area. In this cemetery, two stone horseshoe-shaped tombs (5B20 and 5C7) were excavated, dated to the KA II period. Both burials appear to be secondary, or alternatively are collective burials that house the remains of successive interments (Asgari Citation2018, 28). In burial 5B20, the remains of 15 individuals were found (Asgari Citation2018, 78). In burial 5C7, there were only bone fragments with a few grave goods, and it is not clear whether the burial originally contained skeletal remains (Asgari Citation2018, 23–25). The presence of horseshoe-shaped burials in this site is an interesting occurrence because, as mentioned above, there were previously only three sites—Kiketi and Amiranis Gora in Georgia and Elar in Armenia—where horseshoe-shaped burials had been reported (Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014, 234–235, fig. 4A). The burial chambers at Kohne Tepesi, however, display a very different picture of mortuary rituals and burial practices, as we elaborate upon below.

The Materiality of Death: Mortuary Practices in Kohne Tepesi during the 3rd Millennium b.c.

Kohne Tepesi is located in northwestern Iran in the Khoda Afarin Plain (see ). The main occupation of the site was during the KA period (Zalaghi et al. Citation2021). During the excavation of this site, two mudbrick chamber burials were discovered. The KA occupation at this site dates to the end of KA II and KA III. These funerary architectural remains provide one of the earliest pieces of evidence of this type of architecture, at least in Iran, from the KA and post-KA periods.

Taking into account the tomb architecture, the nature of the burials (number and position of the deceased), and grave goods, we will delve into the materiality of death at Kohne Tepesi. These archaeological elements offer us unique insights into how the inhabitants of this site conceptualized another form of being, or the world beyond life, and constructed their collective social memory through tangible markers within a landscape that served as a constant reminder of their past.

Tomb I

Tomb construction

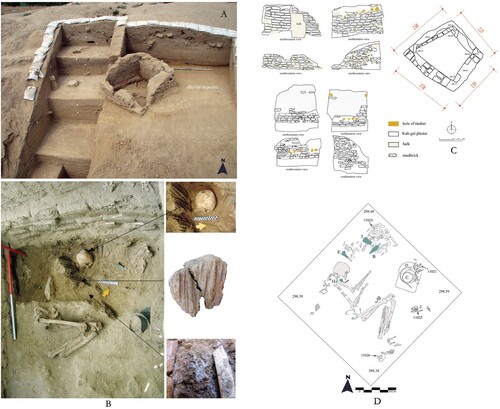

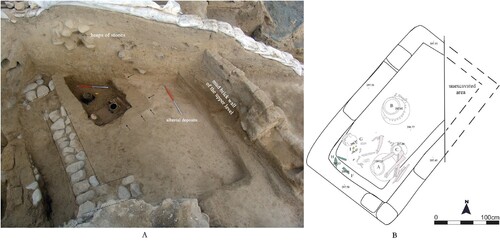

The underground Tomb I was discovered outside the inhabitation area in the southern part of the site (, A). It was dug on the flange of an alluvial terrace, and it seems that a larger pit was cut to give more free space for building the grave and performing the ritual, and this pit was then filled with soil. No remains of stone were found on the surface, and unlike kurgans, it was close to the surface, about 70 cm beneath it. The grave was made of mudbrick (26 × 20 × 10 cm), with two lower levels and a roof composed of timber, thatch, and clay (B–C). The tomb floor was natural soil, and no pavement was observed. Its walls are about 115 cm high, including the roof, which is about 15 cm thick, but the sides of the tomb were otherwise not of equal dimensions (see C). The area of the interior is about 2.7 m2. The corners of the tomb are orientated toward the cardinal directions of the compass, which is an interesting feature. It should be examined whether such a spatial position was a deliberate pattern among other KA burials.

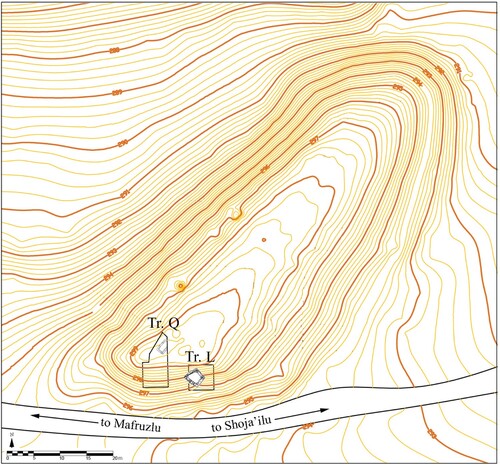

Figure 2. Topographic map of Kohne Tepesi with the excavated chamber tombs: Tomb I (Trench L) and Tomb II (Trench Q) (© A. Zalaghi).

Figure 3. A) General view of Tomb I, in the southern part of the site. B) Human burial of Tomb I, remains of the roof that displaced the skull and remains of the woven-reed mats. C) Sections, top plan, and 3D model of Tomb I. D) The interior of the mudbrick chamber of Tomb I (for letters, see ) (© A. Zalaghi).

On the inner side of the northeastern wall of the tomb, six holes with a diameter of 15–20 cm were found, which would have been for the wooden structure that supported the roof. In the southeastern and southwestern walls, about 100 cm below the roof, there were several other holes, suggesting that the tomb had been covered by two roofs (see C). The lower roof was to separate the space of interment, and the upper roof was the tomb roof. Inside the tomb, there was debris from the mudbrick wall, wood and thatch from the remains of the roof, and the remains of reeds (see B). The entire roof had collapsed into the tomb. Except for the southwestern wall, the upper parts of the inner wall surfaces in the internal space between the upper and lower roofs were covered with Kah-gel plaster (a natural material made from subsoil, water, and straw). Remains of Kah-gel on the exterior surface of the walls were also observed. It, therefore, appears that three sides of the tomb (southeastern, northeastern, and northwestern) were initially built and their interior surface was plastered with Kah-gel. Afterward, the fourth side of the tomb, the southwestern wall, would have been built, accounting for why this wall only has Kah-gel plaster on the outside.

The interments

The burial contained the remains of a tall, male individual, 45–50 years old, lying on their left side in a flexed position and along a northwest-southeast orientation (see B, D). The left and right arms were bent at the elbow and positioned close to the head. The man was wearing a bronze armband on his upper (proximal) right arm. A bronze mace head was found among the faunal remains in the grave, and its handle was close to the skull in the northern corner of the burial (see D). In general, the state of preservation was good except for the pelvis and torso, which were in poor condition. Due to soil pressure and the weight of the roof, the skull seems to have shifted so that the face was turned towards the ground (B). The cranium is also deformed, and the mandible was laterally displaced. The slightly raised position of the pelvis in relation to the torso and the disarticulated position could also be due to the collapse of the upper parts of the tomb and the roof. The head would have been originally positioned along the east-west orientation so that the face was looking east, towards the sunrise. Although the state of the burial designates it as a primary interment, the metatarsals and phalanges of the toes placed next to the left femur possibly indicate that the skeleton was manipulated after decomposition. This burial may therefore be a primary deposition that was disturbed at a later, unknown time. The legs had been placed in a flexed position (45°), and the forearms were flexed almost at 90°. The remains of a cover, probably woven reed mats, were also found on and around the individual, especially in front of the knees and next to the northeastern wall, which may be indicative of a particular ritual or funerary practice (see ).

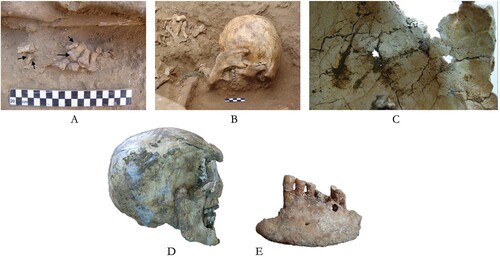

Figure 4. A) Traces of arthritis and severe osteophytic lipping on the edge of the vertebral body and foot phalanges (Tomb I). B–C) Cranial vault porosity (Tomb I). D–E) Calculus formation and a chalky appearance on the labial and buccal surfaces of the teeth (Tomb II; © S. Afshar).

Pathological conditions were diagnosed following Ortner and Putschar (Citation1985) and Buikstra and Ubelaker (Citation1994). Traces of arthritis and severe osteophytic lipping on the edges of the vertebrae and foot phalanges are visible (A), and there is cranial vault porosity (see B–C). Although osteoporosis is normally attributed to advanced aging, it can also be a secondary (type II) pathological finding that can be associated with other skeletal diseases (see Marcus et al. Citation2008; Mays and Cox Citation2000, 191). Two small lytic lesions observed on the cranium might be osteomyelitis (see C) (cf. Marshall Citation2015, 324). These lesions could be associated with punched-out multiple myeloma lytic lesions (Bitelman et al. Citation2016; Ortner and Putschar Citation1985, 192). The arms, legs, and feet are moderately robust, suggesting an active lifestyle.

There was slight to moderate dental attrition, indicative of abrasive food in the diet. A sign of infection was observed in the first left mandibular molar (LM1) in the form of an abscess that affected the pulp cavity and the alveolar bone. The teeth displayed slight to moderate calculus formation and a chalky appearance on the labial and buccal surfaces, as well as the roots (see B). This could be due to hypocalcification, a condition where the tooth’s enamel has an insufficient amount of calcium. When this happens, the teeth take on an opaque or chalky appearance.

Faunal remains

In the northern corner of the tomb, directly in front of the human skeleton’s head, a sacrificed animal had been placed (context 11024, see D). Except for the skull, all skeletal elements of the animal were present. In the southeastern part of the tomb, in front of the human skeleton’s legs, the remains of an animal skull and some rib bones were also found (context 11025). This may be the rest of the animal remains from context 11021 (see D) that had fragmented and been displaced after the roof collapsed. Under the feet of the human body in the southwestern part of the tomb, the remains of other animal skulls with some rib bones were discovered (context 11026). An animal was also intentionally deposited under the human body (context 11027). Unlike the human burial, this animal was buried in a southwest-northeast orientation.

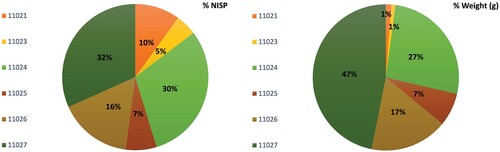

More than 380 elements of animal remains were found in the tomb (, ). By comparing the numbers of the remains and their weight, a differential fragmentation within the six contexts listed above may be observed. The faunal remains are concentrated particularly in contexts 11024 and 11027. We can observe a similarity between the weight and the NISP, meaning that the level of fragmentation was relatively insignificant, as is also the case in contexts 11025 and 11026. In contexts 11021 and 11023, fragmentation was high.

Figure 5. Relative distribution of A) animal remains (%NISP) and B) their weight (%weight g) in various loci of Tomb I.

Table 1. The distribution of animal deposits in the different loci of the Kohne Tepesi tombs.

Zooarchaeological studies reveal that the animal offerings are composed of goats and sheep. According to diagnostic criteria used on cranial and postcranial skeletal parts to distinguish between the two species, it seems that goats outnumber sheep (Boessneck Citation1969; Clutton-Brock et al. Citation1990; Helmer and Rocheteau Citation1994). The number of animal offerings was calculated based on the frequency of skeletal parts (MNIf). The calculated MNI in context 11024 is three, provided by the humeri (). In context 11027, the highest number is provided by the metacarpal bones, where we identified seven partial left specimens, while in context 11026, the maximum MNI is provided by two metatarsals (). As for context 11027, with the highest number of skeletal elements, only three individuals could be recomposed using the scapulae and femurs. In terms of taxonomic identifications, in context 11024, we identified one sheep and one goat based on the morphology of the glenoid cavity of the scapula and the distal part of the first phalanx. In context 11027 and in the other contexts, only goat remains were identified (see ).

Figure 6. Animal deposits in Tomb I (context 11024). A) Ovicaprids: 1) tibia, 2) ribs, 3) humerus, and 4) tibia ( = human skull). B) Ovicaprids: 1) ribs, 2) humerus, 3) radius, 4) ulna, 5) tibia, 6) tibia, 7) coxal, 8) rib, and 9) sternum and intercostal bones.

Figure 7. Animal deposits in contexts A) 11025 (ovicaprini: fragment of maxilla) and B) 11026 (ovicaprini: fragment of mandible).

Figure 8. General view of the human and animal deposits (ovicaprid bones) in context 11027 ( = human bone). Identified ovicaprid bones listed as follows: A) radius right, B) ribs, C) scapula right, D) humerus, E) femur, F) humerus, G) radius left, H) femur right, I) tibia right, J) incisors, K) two 2nd phalanges, L) phalanx 1, M) hemi-mandible, N) sacrum, O) articulated hemi-mandibles, P) two 3rd phalanges, Q) 1st and 2nd phalanges, R) articulated hemi-mandibles, S) occipital bone, T) metatarsal and phalanges, U) metatarsal and phalanges, V) two metacarpals and phalanges, W) metapodial, X) 2nd phalanx, and Y) 1st phalanx.

The deposited animals vary in age. The data on bone fusion and dental wear indicate that juveniles and adults of up to 4 years of age were selected for sacrifice. The youngest animal identified was aged based on the state of fusion of the distal radius and proximal tibia, which were unfused. These bones fuse between 15 and 30 months of age, depending on the breed. Tooth wear is more precise for allocating an age class. The age class (see Payne Citation1973) for the mandible found in Co. 11027 is F, which is 3–4 years of age.

Grave goods

A total of 10 funerary objects, including three ceramic vessels, a bronze hair spiral, an armband, a bronze battle-axe, a spearhead, and a mace head, were found (, ). All of these objects were inside the lower level of the tomb, while a ceramic cup with an accompanying stand was found in the upper space of the tomb (F–G). The ceramic stand (see F) was found on the uppermost level of the tomb, and the cup was found 53 cm below the stand location, suggesting that it had been located on the second floor of the tomb. Inside the lower, interment, part of the tomb, on a mudbrick in front of the knees of the body, we also found another cup with its stand in situ (C–D). Some fruit pits (similar to the pits of cherries or sour cherries) were also found. The cups were decorated with a dimple, and the stand had several grooved lines and a dimple decoration. In the northern corner of the tomb, a third cup was found among the animal bones (A). It is decorated with dimples and is of a very similar shape to the cup pictured in C but larger in size. They are black burnished ware and hand-made with the Nakhichevan style handle. This form of pottery was also found inside the nearby domestic architecture and would have been part of the set of domestic utensils. Cups with Nakhichevan lugs and dimple decoration are the main features of the KA II and III periods.

Table 2. Grave goods of Tomb I and their location relative to the body.

The pot stand found in the tomb is comparable with the pot stand of burial 10 at Elar Tepe in Armenia (Sagona Citation1984, 56, fig. 54, 3). At that site, several stone cist burials were found, and some had a pot stand placed in front of the knees of the body (Palumbi Citation2008a, 194–195, fig. 4.24, 1, 3). In period K of Goey Tepe, several cups were found, as well, and the cups from Kohne Tepesi bear a resemblance to them (Burton-Brown Citation1951, fig. 9, 30, 5).

A spearhead was found close to the ceramic cup (B). This spearhead is comparable to the grave goods of Hasansu I (Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade Citation2012, fig. 2, 2, 4) and Kültepe II (Bakhshaliyev and Marro Citation2009, 76:7; 72:2), seemingly dating to the KA II and III periods. A bronze battle-axe was also discovered (I), an object type that has been found in different regions of the Caucasus, from the Early Bronze Age to the Iron Age. It is comparable with the styles seen at Hasansu I Kurgan in western Azerbaijan (Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade Citation2012, figs. 2, 3) and the metalwork of the Martqopi tradition in the Caucasus (Sagona Citation2004, fig. 17, 4). These forms of axes have also been found in the Arslantepe Royal tomb (Palumbi Citation2008a, fig. 9, b).

The bronze spiral ring was found at the neck, probably used as hair decoration (J). This is one part of the distinctive material culture of the KA tradition that has been found at many burial sites in bronze, silver, and gold (for instance, at Kvatskhelebi: see Palumbi Citation2008a, fig. 6-e). A bronze arm ring was also found on the right arm of the skeleton (H). There do not appear to be any directly comparable objects in the known record, although other types of arm rings have been found in some KA burials in the southern Caucasus and some Iron Age burials.

The last of the objects found is a mace head with a wooden handle, only part of which remains (E). It was placed in front of the face, and perhaps its wooden handle was in the right hand of the deceased. There do not appear to be any similar examples reported. The presence of mace heads in funerary contexts in the KA culture is rare. It is possible that this bronze artifact was cultic and not a military weapon.

It is not possible to associate Tomb I with any household within the settlement. Instead, it appears that during the establishment of Tomb I, the rest of the site was not yet settled, based on the one available 14C date from the settlement. The earliest carbon date of phase I is later, around 2636–2339 cal b.c. Nevertheless, some of the pottery from the tomb shows some degree of similarity with the examples that were found inside the domestic architecture.

Tomb II

Tomb construction

Tomb II is located in the southwestern portion of the site (see , ). It is a rectangular mudbrick tomb in a northeast-southwest orientation, 280 cm long, 177 cm wide, and 70 cm high. A small part of the tomb remained unexcavated. It was constructed of four mudbrick walls with mud mortar. The mudbricks were of various sizes: 25, 32, or 42 cm long × 32 or 30 cm wide × 8 to 10 cm high. Unlike Tomb I, this tomb had no timber roof, and it seems that its interior space was filled with natural soil. On the inner side of the southwestern and southeastern walls of the tomb, a mudbrick platform about 20 cm high had been built. It had likely been used for the placement of grave goods. The tomb was built about 180 cm beneath the current surface level.

Figure 10. A) The location of Tomb II; the stone foundation is part of the KA III structure, and the arrows show the walls of the tomb, which are built into the alluvial sediment. B) The interior of the mudbrick chamber of Tomb II (for the identification letters, see ) (© A. Zalaghi).

There is no apparent cultural association between the tomb and the residential area, although they physically intersect. During the tomb’s construction, its northern/northwestern sides removed part of the stone foundation of a wall belonging to the KA domestic architecture (A). It seems that the KA architecture was already in ruins at the time of the establishment of the tomb. The southern and southwestern sides of the tomb, like the northern sides, are built into the natural soil of the hill. Due to a grave from a later period located about 40 cm above the tomb cutting into the upper parts of the tomb, it is difficult to reconstruct the initial condition of the upper level of the tomb structure. A heap of stones was also found 1 m above the tomb. It is not clear whether these stones originated from a lower level and were originally placed on the tomb, becoming displaced when the later graves had been dug, or whether they are the remains of the debris of a stone wall of the Parthian period. It is, therefore, very difficult to say whether the tomb was a kurgan.

Interments

This burial contained the remains of a probable male individual, 35–45 years old, lying on their left side in a fetal position in a northwest-southwest orientation against the western wall, facing east (B). The soil on top of the skeleton was very fine and contained a white residue, especially on the torso, and may have been the remains of a cover over the burial. The body was parallel to the western wall. Instead of burying the skeleton along the long axis of the tomb, it was buried in a transverse orientation in a fetal position facing east, towards sunrise. The right arm was bent at the elbow towards the head, and the left hand was bent 180° towards the forearm. The pelvis was unfortunately missing. We do not know whether this was due to a taphonomic process or to the displacement or removal of the pelvis.

The interment was accompanied by three storage jars, two large jars and a small jar (see ). One of the large storage jars was placed on the pelvis area of the individual, which was a seemingly intentional arrangement, as if the pelvis had been deliberately displaced to accommodate the pottery. The small jar was discovered near the right side of this large jar. The second large jar was placed close to the face of the individual in the middle of the grave. The location of the skull within the grave indicates that the skull would have originally been in association with the postcranial remains. The skull is deformed due to depositional pressure of the soil (D). The lower limbs were positioned touching the two pelvic jars, and both femurs leaned on the jars. The position of the individual seems cramped, especially in the vicinity of the head and the lower limbs. Nevertheless, the positions of the skull, mandible, forearms, and thoracic vertebrae indicate a primary burial.

In general, the state of preservation was poor except, relatively speaking, for the lower limbs. The position of the individual in the grave is similar to that seen at Kalavan-1 UF9, northeast of Lake Sevan in the valley of the Barepat in Armenia (Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014). The Kohne Tepesi burial has also been the object of post-depositional practice, inferred by the abdominal position of the jars and the compact posture of the lower limbs (see B).

This individual exhibited slight to moderate dental attrition, indicative of the presence of abrasive food in their diet. The teeth displayed slight to moderate calculus formation and a chalky appearance on both the labial and buccal surfaces (E). This could be due to hypocalcification, a condition where the tooth enamel has an insufficient amount of calcium.

Faunal remains

Unlike Tomb I, there is no trace of sacrificed animals. The seven animal remains found inside the tomb are as follows: three fragments of ribs, one nearly complete right scapula, one complete, carbonized left humerus, and one rather complete left radius with the olecranon of an ulna. The humerus and radius were identified as sheep, while the other bones could be attributed to either sheep or goat. Notably, these skeletal elements were not found in an anatomical position. It is challenging to determine whether the left side elements belong to the same individual, and the same uncertainty applies to the scapula, which is derived from the opposite side. The bones were evidently processed for consumption, as evidenced by cut marks on the scapula and the carbonization of the humerus. According to Barone (Citation1999), the fusion age for unimproved sheep/goat breeds for the proximal humerus is 25–35 months, for the proximal radius is between 3 and 5 months, and for the ulna, fusion typically occurs around 25–30 months. On the basis of these observations, the animal remains of Tomb II belong to an adult sheep aged between 2 and 3 years (according to the fusion stage of the humerus and the ulna), and maybe another individual older than 5/7 months, if we consider that the scapula and the radius do not belong to the same animal. However, due to the fragmentation and preservation state of these faunal remains, it is not possible to determine.

Grave goods

In total, 9 grave goods were found in this tomb and are divided into two main groups, as in Tomb I: ceramic vessels and metal artifacts (see , ). The ceramics are comprised of 5 objects: 3 storage jars and 2 cups. Two storage jars were found in close association with the skeleton, and the other jar had been placed at a short distance from the body. Two of the jars are large, and the third one is medium-sized. Jar A has two knob decorations in relief on opposite sides of the body and a decorative handle. Jar B is also decorated with a row of knob decorations in relief and has two hemispherical handles on opposite sides of the body. Jar C is decorated with four knob decorations in relief between a Nakhichevan handle. All of the jars are black-brown burnished wares, and they all have an everted rim and a flat base with a carination around the middle of the body.

Table 3. Grave goods of Tomb II and their location relative to the body.

The other ceramic vessels were two cups: cup D was found inside jar C, and cup E was inside jar B. They are black burnished ware with handles with a carination close to the base. Both are decorated with a dimple and a horizontal line (D–E). These cups found inside storage jars were probably used to hold liquids. No similar storage jars were found inside the residential area.

Four metal artifacts were found in this tomb (F–I), including a gold spiral ring that was at the neck. In KA sites in Iran, no gold artifacts have been found previously. Gold spiral rings are common artifacts elsewhere among societies in the southern Caucasus during the 4th and 3rd millennia b.c., and they have all been found in funerary contexts (Stöllner Citation2021). At Hasansu I, in an intrusive tomb, two gold rings comparable to the one found at Kohne Tepesi were recovered (Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade Citation2012, figs. 3, 5). The gold at Hasansu likely came from the Sakdrisi gold mine in Georgia, which is the only rock gold mine known to have existed in the Caucasus contemporary with the KA culture (Stöllner Citation2021, 113).

Like Tomb I, a flat axe and a spearhead were found on a mudbrick platform beside the skeleton (see F, H). The spearhead consists of two parts that are joined together. The first piece is a triangular-shaped blade that is 17.3 cm long, 5.9 cm wide, and 0.2 cm thick. The other piece is a circular rod that is thicker on one end and tapers towards the other end. The thicker side is pierced by a hole with a 2.6 cm diameter, which was probably for the placement of a wooden handle. These types of metal artifacts are frequently found within the KA and kurgan funerary traditions and have been found from the Early to the Middle Bronze Age. Seven bronze artifacts were also discovered (see G). Two of these were found positioned on the clavicle bones and the others on the cervical vertebrae, which could be a sign of their function as a necklace. They were also entirely oxidized and green in color. Every piece was perforated with a hole for thread, and they probably had been decorated.

Tomb architecture: symbolism and rituals

To bring it all together, based on this detailed examination, it can be said that the tomb architecture at this site embodies the essence of memory and place. These underground mudbrick chamber tombs, meticulously constructed and adorned with symbolic elements, serve as more than mere repositories for the deceased. They are, in essence, monuments to the living community’s collective memory. As individuals were laid to rest within these chambers, the living community actively engaged with the metaphysical and communal dimensions of mortality. Furthermore, the number and position of the deceased within these tombs are deliberate expressions of cultural norms. Some are placed in a manner that suggests a particular orientation, potentially aligning with cosmological beliefs. In the same vein, the choice of specific grave goods, their arrangement, and their symbolism provide further insights into the society’s worldview. While some grave goods, such as specific forms of pottery or metal objects inside the tombs, are tangible expressions of the social identity of the departed, other elements, such as animal skulls, food remains, and beverages, hold spiritual or ritualistic significance, pointing to the society’s metaphysical interpretations of death (Morris Citation2011). In the following section, we delve into the dating of these burial practices to uncover the temporal context that shaped these profound expressions of culture and spirituality.

Chronological Context of the Kohne Tepesi Burial Chambers

Tomb I is located outside of the residential area, and Tomb II was constructed later among the ruins of the KA structure without any apparent relationship to the domestic remains. These circumstances make it very hard to place the tombs chronologically and to determine what association they might have with the people who lived inside the houses of Kohne Tepesi. Furthermore, the number of finds from inside the tombs is too scant to provide much information that might allow the graves to be dated. At the very least, it does appear that the pottery assemblages inside Tomb II do not correspond with the finds within the KA phases of the settlement. Only the cups from Tomb I were comparable to the material from the KA settlement, and they also bear a resemblance to types 21 A and B of Sagona’s typology (Sagona Citation1984, fig. 12). The form of the storage jars from Tomb II is generally comparable to the jar found at Hasansu I (Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade Citation2012, figs. 1, 2), which has been dated to the first half of the 3rd millennium b.c., although other scholars have dated the Hasansu grave to the Early Kurgan Culture (Courcier et al. Citation2016, 29). Bertram believes that the Martqopi tradition resembles or echoes the KA pottery style, while Bedeni is much more distinctive and of a higher quality than the KA pottery (Bertram Citation2005, 63). In our case, on one hand, the rows of knob decorations are more known to be more characteristic of the Bedeni tradition (Rova Citation2018); however, the carinated form of the body and its surface treatment more closely resemble the Martqopi. If we consider Bertram’s criteria, the Tomb II pottery should be considered Martqopi. At this stage of the study, it is not possible to assign the inventories to specific traditions more precisely than this, and we will consider it as a “Martqopi-Bedeni” burial.

Like many other KA settlements, only a few metal objects (such as small pins) were discovered inside the residential remains. The elaborate metal objects that were found inside the graves are unusual and striking. At first glance, the high number of varied metal artifacts in both tombs and the absence of metal artifacts in most KA burial traditions makes it tempting to consider both tombs as belonging to the Early Kurgan Culture (Martqopi-Bedeni phase). Furthermore, the appearance of similar metal artifacts, like the flat bronze battle-axe, spearheads, and spiral rings in both tombs, may reveal a continuity of funerary tradition at Kohne Tepesi. However, the overall analysis suggests it is more likely that the tombs belong to two different periods. The metal objects of Tomb I are more similar to those found at Hasansu I (Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade Citation2012, figs. 2, 3, 5) and Kültepe II (Bakhshaliyev and Marro Citation2009, 76:7, 72:2). The construction and burial tradition of Tomb I also do not bear much resemblance to Hasansu, and the only carbon dating does not support an Early Kurgan date for Tomb I.

Generally, based on the grave goods and the single 14C date, Tomb I could be dated to the end of KA II or the beginning of KA III and Tomb II to the post-KA phase. The carbon dating from Tomb I places it at 2708–2471 cal b.c. No carbon dating is available for Tomb II, but the decoration on the pottery assemblage and metal objects is mostly comparable with the Martqopi-Bedeni tradition. Some scattered sherds from the post-Kura-Araxes phase were also found on the surface of the site, but none of them are comparable to the pottery assemblage of Tomb II.

What Do the Kohne Tepesi Mortuary Practices Tell Us?

As we previously discussed in this article, the burial ritual represents a pivotal juncture wherein an entire community consolidates its social structure and reinforces dominant ideologies by collectively expressing shared beliefs (Laneri Citation2007, 5). The inhabitants of Kohne Tepesi employed material culture to create a ritual space, a place of commemoration. This underscores the profound importance of constructing collective social memory in this locale. The tomb architecture, body treatment, and grave goods exemplify how the tangible aspects of burial practices serve as a gateway into understanding the intangible dimensions of memory, belief systems, and the metaphysical realms.

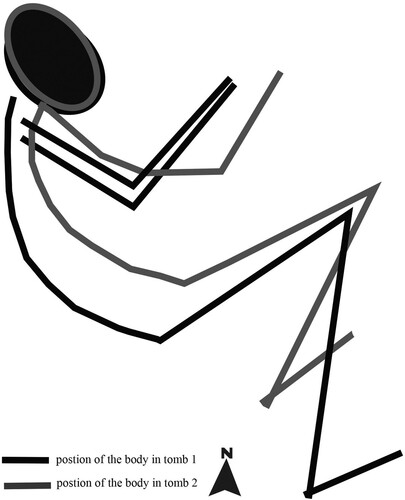

Despite some commonalities, there are many differences between the two tombs. All of the grave goods of Tomb I were placed in front of the body, and in Tomb II, they were positioned on a mudbrick platform behind the body. Tomb I was extramural, at a short distance from the domestic architecture, while Tomb II was very close to the domestic architecture, although not related to it. Tomb I was square with two roofs, and Tomb II was rectangular and unroofed. The floors of both tombs were natural soil without any pavement. There were animals or animal parts deposited under the human skeleton only in Tomb I; however, in both tombs, a meat offering had been part of the ritual. The position of the bodies in both tombs was in a curled position and almost identical (). In both burials, the head was placed towards the northwest and the body was laid on the left side so that the face looked east towards sunrise. In the southern Caucasus, individuals have been known to be buried on either the left or right side. It is not clear whether this represents different types of burial traditions or whether an individual would have been buried on a particular side according to their gender. Museibli, Axundova, and Agalarzade (Citation2012, 108) state that in the southern Caucasus, males were mostly buried on their right and females on their left sides.

Figure 12. Schematic reconstruction of the position of the bodies in both chamber tombs (© A. Zalaghi).

The ceramic vessels of Tomb I only consisted of cups and stands, while in Tomb II, large liquid storage jars with two cups inside of them were found. All ceramic vessels associated with the liquid containers demonstrate the important role of beverages in the ceremonial rituals of the KA people. Meat offerings in Tomb I had a more prominent role than the drink offerings, while in Tomb II, it was the contrary, with the drink offerings being more prominent. The latter is also the case in the burial rituals during KA II to the end of the KA period. But what is particularly notable, when looking at the structure, grave goods, and animal remains, is that there are many discrepancies between the Kohne Tepesi burials and other contemporary burial practices in the southern Caucasus. This divergence from established norms in the region is explicitly addressed in the following sections.

Structure

As mentioned before, Poulmarc’h (Citation2014) categorized KA burials in the southern Caucasus into six main groups. The main question is: to which of Poulmarc’h’s categorizations could the Kohne Tepesi burial tombs be assigned? The stone-lined grave is one of the earlier KA funerary traditions that is widely present, mainly in Armenia and Georgia (Poulmarc’h, Pecqueur, and Jalilov Citation2014, 234). They are mostly collective and rarely individual. However, at Kohne Tepesi, Tomb I is made of mudbrick and is for an individual. It has two roofs, which have not been reported elsewhere. The rectilinear form of the burial is recorded from other KA burials in Armenia or Georgia; however, most of them are stone crypts with a door or dromos that provide access to the chamber, which is not the case in Kohne Tepesi. A mudbrick rectilinear chamber with no entrance and two timber roofs may be one of the rarest examples in the whole of the KA oikumene. The burials could be categorized into a pit grave group, but it is again different from those attested in Georgia (Puturidze and Rova Citation2012; Rova Citation2018), and the mudbrick walls are a major difference between these two styles. Based on the current evidence, no remains of a mound erected above the chamber or the grave were recognized, and there are no remains of stones placed upon it, though we should take into account the probability of later changes during the Parthian period. It seems neither of the excavated tombs in Kohne Tepesi could be assigned to categories designated by Poulmarc’h.

The Early KA kurgans at Uzun Rama revealed more or less comparable kurgans. Although the layout of Kohne Tepesi has nothing in common with Kurgan 8 (maybe just its rectangular form), both were built with mudbrick walls and a wooden beam roof. Kohne Tepesi is, however, different in ritual behavior, as well. Unlike Uzun Rama, there is no tradition of setting the chambers on fire in Kohne Tepesi. Another difference between the Mentesh Tepe and Uzun Rama kurgans versus Kohne Tepesi is in the number and position of the deceased. The former kurgans yielded collective communal burials, while in Kohne Tepesi, we are confronted with an individual burial. The only commonality is a deposit of animal remains inside the burial chambers. In Uzun Rama, the remains of sheep/goat skeletons were found, which shows that burying sheep/goat skeletons were part of the ritual practice in this part of the KA oikumene (Jalilov Citation2018). The lack of such behavior in other recognized burials of the KA period could suggest various hypotheses. It could be a chronological issue. All of these kurgans are dated to the last phases of the KA period, and most others are dated to earlier periods. The lack of carbon dating for most of them makes it hard to verify this. Or perhaps we are confronted with different practices and rituals, which are already demonstrated by different forms of burial, their construction, and materials. However, beyond that, we can see more discrepancies in ritual behaviors.

Despite some commonalities with Tomb I (rectilinear mudbrick chamber), Tomb II clearly has a different construction pattern. Other post-KA burial chambers in the southern Caucasus have some commonalities in form and material with this burial. During the post-KA period, individual burials were more common, and they were usually accompanied by a variety of offerings, as seen in Tomb II. However, most of them were buried deep beneath the earth and mainly outside residential areas. Even if we consider the scattered heap of stones atop this burial not to be remains from the Parthian period, this burial was not as deep as other known kurgans. As said earlier, due to the later transformation of the site, we cannot even be sure if it was in the form of a kurgan.

Grave goods

Grave goods are either interpreted as possessions of the deceased or a reflection of “the living societal members’ choices for the representation of the status or rank of the deceased” (Hanks Citation2002, 368). It seems that in our case, particular areas of the burial pit were used to place grave goods and animal offerings in Tomb I. In Tomb II, despite the available space elsewhere in the tomb for the placement of grave goods and animal parts, it seems that they were deliberately put under the feet of the deceased person. These arrangements suggest a conscious effort to imbue the burial with symbolic significance, likely linked to beliefs surrounding the journey to the afterlife.

Since tools and weapons are rare among KA burials, Tomb I’s inventory is notable. The absence of metal objects in the occupation areas, while finding them exclusively in burial contexts, may signify their symbolic importance. Metal artifacts from both tombs could be divided into two main groups: weapons and adornments. These metal objects were probably used in everyday life, such as for a game or for collecting firewood, not necessarily as military objects. The mace head could also be defined as a prestigious artifact. The other metal objects, like armbands, spiral rings, and necklaces, were probably used as adornments. Spiral rings may have been prestigious ritual objects and a sign of higher societal status (Stöllner Citation2021, 101). The grave goods of Tomb II bear a greater resemblance to the Early Kurgan tradition.

Animal remains

There are different assumptions about animal remains: some believe that the animals were actually the real food that was served in a ceremony (Chapman Citation2003; Cultraro Citation2007, 92), and some others see them as a sacrificial ritual, as a way of maybe giving back to the dead some kind of life force, since the killing of an animal is the spilling of its blood, its life force. The first perspective suggests that communal gatherings may have taken place to commemorate the deceased. In the second viewpoint, the shedding of blood, symbolizing vitality, might have been perceived as a means of nourishing or guiding the departed in their spiritual journey. The act of sacrifices and the deliberate inclusion of faunal remains within these two tombs represent distinctive ritual behaviors. These practices have the potential to reveal valuable insights into the spirituality and belief systems of these people. Building upon this notion, Borenstein (Citation2022) posits that these practices should be regarded as fundamental components in the construction of religious systems within the broader context of KA communities.

The construction of Tomb I before the occupation of the hill may encourage the argument that such monuments served as a social display, potentially enabling the legitimization of rights over the land and the exploitation of the surrounding resources (Laneri Citation2007, XIII). Regarding the spatial placement of the burials, several hypotheses could be raised, and the two tombs could both be interpreted through a variety of scenarios. It could be assumed that these burials belonged to mobile pastoral groups that built the tombs during their seasonal movements and left the deceased near the location where they died. Alternatively, another scenario could be that this location (Kohne Tepesi) was the specifically designated location for interment to encapsulate the deceased’s social memory and that the body was transported after death to be buried in this specially erected tomb. Thus, the enigmatic nature of these tombs invites a multitude of interpretations, each offering a unique lens through which we can glimpse the intricate tapestry of social and funerary practices of the Kohne Tepesi community.

Monuments of Collective Memory: Lives Once Lived by the Dead

While collective burials of KA societies may initially suggest a perception of the deceased as emptied and inherently meaningless, the Kohne Tepesi burials, furnished with various offerings and grave goods, illustrate another picture. What can be concluded based on this study is that these burial practices were not just about death as a biological transition but rather about a “social dying” (Robb Citation2013, 8). This includes a long-term process of preparation, death, and subsequent ceremonies of remembrance. It underscores that the significance of the deceased did not diminish upon death; instead, their memory and impact persisted within the living community.

The structure of the KA burial, particularly Tomb I, resembles a house with mudbrick walls and a thatched roof. An intriguing common thread that binds both these burials together is the profound significance attributed to offerings and libations. These ceremonial acts underscore the enduring connection between the living and the departed, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a spiritual rapport with those who have transitioned to the other world.

As far as the heads of animals intentionally and carefully placed within Tomb I are concerned, it becomes evident that they hold a distinct ritual and metaphysical importance. When we analyze Tomb I in light of its grave goods and architecture, two compelling perspectives emerge. The first one posits Tomb I as the tomb of an elite member of society, thereby symbolizing hierarchy and social differentiation. Alternatively, Tomb I could be viewed as the burial of a typical member of society. In this interpretation, grave goods and animal remains become integral components of performance, embodying aspirations for a higher status in the afterlife. Such rituals may not necessarily signify the deceased’s existing high status but rather reflect the communal desire to secure a favorable position in the world beyond. It’s crucial to recognize that burial customs offer profound insights into how society grapples with the concept of mortality, navigate questions of social identity, and formulates perspectives on the afterlife. Indeed, the structure and organization of these burial practices serve as a captivating window into the profound ideological behaviors that encompass a complex interplay of cultural, spiritual, and social elements. They are manifested through distinct types of tombs, the careful arrangement of bodies within the chambers, and burying them with particular goods.

A more detailed picture may be envisaged if we try to reconstruct the events behind this burial. On one day in an unknown season, several goats and sheep were chosen for slaughter. The choice of these domestic animals demonstrates their importance in the subsistence economy, as well as in the diet of the Kohne Tepesi inhabitants, and the importance of domesticates in the afterlife (Zalaghi et al. Citation2021).

By sealing the chamber, they most likely wanted to separate the living world from the dead, and there was no sign of later use of the burial site. In collective burials, the sites are reused—the worlds of the living and the dead are not separate. The setting of these two monuments and the offerings look as though the deceased was not being laid to rest but as though they are moving to their new home, to another form of being in another kind of place. The burial chamber, a marker constructed in a living landscape, is a signifier to show that the deceased continues to reside in their community. Drawing on the given data, as we said earlier, we can imagine that the burial rite at Kohne Tepesi included a ceremony to commemorate the dead. Hence, for the Bronze Age community at Kohne Tepesi, which could be perhaps extended to their peers elsewhere, dying was a transition to a form of being that, through a ritualistic performance, aimed to preserve their social memory.

To sum up, despite some extensive excavations on KA sites, our understanding of burial practices and funerary traditions among the diaspora is generally very patchy and remains an important topic for further investigation. In this respect, the Kohne Tepesi burial chamber provides valuable evidence of KA mortuary practices. When looking at the various forms of burial practices among KA and post-KA communities, it could be assumed that there would have been equally varied relationships between the deceased and living members of KA society, and hence different forms of social and cultural networks. This means there were different methods of cognitive acknowledgment, materialization, and memorialization of death. Across various regions and periods, these rituals reveal rich beliefs, values, and social dynamics. From collective burials that blur the boundaries between the living and the dead to carefully constructed tombs laden with offerings, these practices attest to the enduring human quest to grapple with the mysteries of existence and commemorate the deceased.

Acknowledgments

The excavation of Kohne Tepesi was carried out as part of the Khoda Afarin dam project with the support of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research (ICAR). The primary bioarchaeological study of Tomb I in the field was conducted by Farzad Foruzanfar, to whom we are grateful. The primary bioarchaeological study of Tomb II was conducted by Zahra Afshar, to whom we are grateful. Carbon dating analysis of Kohne Tepesi was possible with the help and support of Marjan Mashkour (UMR 7209–AASPE–CNRS and Museum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris). We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. All errors are, of course, ours.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sepideh Maziar

Sepideh Maziar (Ph.D. 2016, Goethe University) is an associate researcher at Goethe University Frankfurt. Her research interests include migration, social identity, collective memory, social networks, and resilience strategies in diasporic contexts, with a focus on prehistoric communities of southwestern Asia.

Ali Zalaghi

Ali Zalaghi is a Ph.D. candidate at Johannes Gutenberg University who specializes in landscape archaeology with a focus on the archaeology of Iran.

Bayram Aghalari

Bayram Aghalari (Ph.D. 2017, Hacettepe University) is lecturer at University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Iran. His research interests include the archaeology of the protohistory and historical period of northwestern Iran and eastern Anatolia.

Sepideh Asgari

Sepideh Asgari (M.S. 2018, California State University, East Bay) is a cytologist at SFVAMC. Her research interests include bioarchaeology, paleopathology, burial practices, and the Near Eastern Bronze Age.

Shiva Sheikhi

Shiva Sheikhi (M.A. 2008, University of Tehran) is an archaeozoologist whose thesis was on the faunal remains of Kohneh Tepesi. She currently works as a freelance archaeozoologist in Iran.

Marjan Mashkour

Marjan Mashkour (Ph.D. 2001, Université Paris 1- Panthéon Sorbonne) is an archaeozoologist and Co-director of the Archaeozoology & Archaeobotany joint research group of CNRS and the National Museum of Natural History of Paris. She works on the evolution of subsistence economies of the Iranian Plateau and adjacent countries through classical and molecular multi-proxy approaches.

References

- Alizadeh, K., H. Eghbal, and S. Samei. 2015. “Approaches to Social Complexity in Kura-Araxes Culture: A View from Köhne Shahar (Ravaz) In Chaldran, Iranian Azerbaijan.” Paléorient 41 (1): 37–54.

- Asgari, S. 2018. “Bioarchaeological Analysis of Human Skeletal Remains at Kohne Shahr an Early Bronze Age site in Northwestern Iran.” (MA thesis. California State University). East Bay, unpublished.

- Bakhshaliyev, V., and C. Marro. 2009. The Archaeology of Nakhichevan: Ten Years of new Discoveries. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları.

- Barone, R. 1999. Anatomie Comparée des Mammifères Domestiques. Paris: Vigot édit.

- Bedianashvili, G., C. Sagona, C. Longford, and I. Martkoplishvili. 2019. “Archaeological Investigations at Southwest Georgia: Preliminary Report the Multi-Period Settlement of Rabati, (2016, 2018 Seasons),” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 56: 1–133.

- Bertram, J. K. 2003. Grab-und Bestatungssitten des Spaten 3. und des 2. Jahrtausends v.CHR. im Kaukasusgebiet. Langenweissbach: Beier und Beran.

- Bertram, J. K. 2005. “Probleme der Ostanatolischen/Südkaukasischen Bronzezeit: Ca. 2500-1600 vu.Z.” TÜBA-AR: Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Arkeoloji Dergisi (8): 61–84.

- Bitelman, V., J. Lopes, A. Nogueira, F. Frassetto, and A. Duarte. 2016. “Punched out Multiple Myeloma Lytic Lesions in the Skull.” Autopsy and Case Reports 6: 7–9.

- Boessneck, J. 1969. “Osteological Differences Between Sheep (Ovis Aries Linne´) and Goat (Capra Hircus Linne´).” In Science in Archaeology, edited by D. Brothwell, and E. Higgs, 331–358. London: Thames and Hudon.

- Borenstein, G. B. 2022. “Building Belief: from Symbolism to Social Organization in Early Bronze Age Eurasia (3500-2400 BC).” (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Anthropology, Cornell University.

- Buikstra, J. E., and D. H. Ubelaker. 1994. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series 44. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archaeological Survey.

- Burton-Brown, T. 1951. Excavations in Azerbaijan, 1948. London: John Murray.

- Carminati, E. 2014. “Jewellery Manufacture in the Kura-Araxes and Bedeni Cultures of the Southern Caucasus: Analogies and Distinctions for the Reconstruction.” Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 23: 161–186.

- Carminati, E. 2017. “The Martqopi and Bedeni Components of the Early Kurgan Complex in the Shida Kartli (Georgia): A Reappraisal of the Available Data.” In At the Northern Frontier of Near Eastern Archaeology: Recent Research on Caucasia and Anatolia in the Bronze Age: Proceedings of the International Humboldt-Kolleg Venice (Subartu XXXVIII), edited by E. Rova, and M. Tonussi, 173–188. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Chapman, R. 2003. “Death, Society and Archaeology: The Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices.” Mortality 8: 305–312.

- Chesson, M. S. 2001. “Embodied Memories of Place and People: Death and Society in an Early Urban Community.” In Social Memory, Identity, and Death: Anthropological Perspectives on Mortuary Rituals, edited by M. S. Chesson, 100–113. Arlington: American Anthropological Association.

- Clutton-Brock, J., K. Dennis-Bryan, P. L. Armitage, and P. A. Jewell. 1990. “Osteology of the Soay Sheep.” Bulletin of British Museum (Natural History) 56 (1): 1–56.

- Courcier, A., B. Jalilov, I. Aliyev, F. Guliyev, M. Jansen, B. Lyonnet, N. Mukhtarov, and N. Museibli. 2016. “The Ancient Metallurgy in Azerbaijan from the End of the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age (6th-3rd Millennium BCE): An Overview in the Light of New Discoveries and Recent Archaeometallurgical Research.” In From Bright Ores to Shiny Metals. Festschrift for A. Hauptmann, edited by G. Körlin, M. Prange, T. Stöllner, and U. Yalçin, 25–36. Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau- Museum.

- Cultraro, M. 2007. “Combined Efforts Till Death: Funerary Ritual and Social Statements in the Aegean Early Bronze Age.” In Performing Death: Social Analysis of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, edited by N. Laneri, 81–108. Chicago: Oriental Institute seminars.

- Hanks, B. K. 2002. “Societal Complexity and Mortuary Riltuality; Thoughts on the Nature of Archaeological Interpretation,” in Complex Societies of Central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC; Regional Specifics in Light of Global Models, edited by K. Jones-Bley, D. Zdanovich, 355–373. Washington D.C: Institute for the Study of Man.

- Helmer, D., and M. Rocheteau. 1994. “Atlas du Squelette Appendiculaire des Principaux Genres Holocènes de Petits Ruminants du Nord de la Méditerranée et du Proche-Orient (Capra, Ovis, Rupicapra, Capreolus, Gazella),” Fiche ostéologie animale pour l'archéologie, série B: Mammifères: 1-21.

- Hovsepyan, I., and A. Mnatsakanyan. 2011. “The Technological Specifics of Early Bronze Age Ceramics in Armenia: Tsaghkasar I and Talin Cemetery.” Aramazd 6 (2): 24–54.

- Iravani ghadim, F. 2013. “Excavations in Jafar Abad: Preliminary Report of Kurgan No V.” In Studies Presented in Honour of Sümer Atasoy, edited by Y. Hazirlayan, 217–236. Ankara: Hel Yayincilik.

- Iravani ghadim, F., and S. Beikzadeh. 2018. “Animal Remains Excavated at Jafar Abad and Tu Ali Sofla Kurgans, Northwest Iran (2010 and 2013 Seasons).” TÜBA-AR 23: 101–120.

- Jalabadze, M., and G. Palumbi. 2008. “Kura-Araxes Tombs at Takhtidziri.” In Archaeology in the Southern Caucasus: Perspectives from Georgia (Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 19), edited by A. Sagona, and M. Abramishvili, 117–123. Leuven: Peeters.

- Jalilov, B. 2018. “The Collective Burial Kurgan of Uzun Rama.” TÜBA-AR 2018: 94–105.

- Kalantaryan, I. 2007. “The Principal Forms and Characteristics of Burial Constructions in Early Bronze Age Armenia,” Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies 2: 72-84.

- Kazempour, M., and K. A. Niknami. 2017. “A Fortress and New Kurgan Burials at Zardkhaneh Ahar: Reassessment of the Chronology of the Late Prehistory of Northwestern Iran.” International Journal of Society for Iranian Archaeology 3: 13–36.

- Laneri, N. 2007. “An Archaeology of Funerary Rituals.” In Performing Death: Social Analysis of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, edited by N. Laneri, 1–14. Chicago: Oriental Institute seminars.

- Laneri, N. 2018. “Funerary Customs and Religious Practices in the Ancient Near East,” in Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by C. SMITH. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3257-1.

- Laneri, N., S. M. Celka, and G. Palumbi, eds. 2019. Constructing Kurgans. Burial Mounds and Funerary Customs in the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia During the Bronze and Iron Age. Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Florence (Studies on the Ancient Near East and the Mediterranean 4). Roma: Arbor Sapientiae.

- Marcus, R., D. Feldman, D. A. Nelson, and C. J. Rosen. 2008. Osteoporosis (3rd ed). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.

- Marshall, M. 2015. “Bodies: A Bioarchaeological Investigation of Lived Experiences and Mobile Practices in Late Bronze Age- Early Iron Age (1500-800BC).” (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Chicago.

- Mays, S., and M. Cox. 2000. “Sex Determination in Skeletal Remains.” In Human Osteology in Archaeology and Forensic Science, edited by M. Cox, and S. Mays, 117–130. London, UK: Greenwich Medical Media, Ltd.

- Maziar, S. 2023. “Resilience in Practice; A View from The Kura-Araxes Cultural Tradition in Iran.” In Coming to Terms with the Future: Concepts of Resilience for the Study of Premodern Societies, edited by S. Pollock, R. Bernbeck, and G. Eberhardt, 99–119. Stoneline: Leiden.

- Morris, J. 2011. “Animal ‘Ritual’ Killing: From Remains to Meanings.” In The Ritual Killing and Burial of Animals: European Perspectives, edited by A. Pluskowski, 8–21. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Muscarella, O. W. 2003. “The Chronology and Culture of Se Girdan: Phase III.” Ancient Civilizations 9: 117–131.

- Museibli, N., G. K. Axundova, and A. M. Agalarzade. 2012. “Ağstafa Rayonunda Tunc Dövrünün Qəbir Abidələri.” Azərbaysanda arxeoloji təadqiqatlar 2011: 97–108.

- Ortner, D. J., and W. G. J. Putschar. 1985. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Palumbi, G. 2008a. ““from Collective Burial to Symbols of Power. The Translation of Role and Meanings of the Stone-Lined Cist Burial Tradition from Southern Caucasus to the Euphrates Valley.” Sci. dell’ Antich 14: 17–44.

- Palumbi, G. 2008b. The Red and Black: Social and Cultural Interaction Between the Upper Euphrates and Southern Caucasus Communities in the Fourth and Third Millennium BC. Roma: Sapienza Università di Roma.

- Palumbi, G. 2016. “The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Caucasus,” in Oxford Handbooks online.

- Payne, S. 1973. “Kill-off Patterns in Sheep and Goats: The Mandibles from Aşvan Kale.” Anatolian Studies 23: 281–303.

- Poulmarc’h, M. 2014. “Pratiques funeraires et identite biologique des populations du Sud Caucase du Neolithique a la fin de la culture Kura-Araxe (6eme e 3eme millenaire av. J.-C.): une approche archeo-anthropologique.” (These de doctorat). Universite Lumiere Lyon 2, France.

- Poulmarc’h, M., and F. Le Mort. 2016. “Diversification of the Funerary Practices in the Southern Caucasus from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic.” Quaternery International 395: 184–193.

- Poulmarc’h, M., L. Pecqueur, and B. Jalilov. 2014. “An Overview of the Kura-Araxes Funerary Practices in the Southern Caucasus.” Paléorient 40: 231–246.

- Puturidze, M., and E. Rova. 2012. “The Joint Shida Kartli Archaeological Project: Aims and Results of the First Field Season (Autumn 2009),” in Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Volume 2. Edited by R. Matthews, and J. Curtis, 51–70, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Robb, J. 2007. “Burial Treatment as Transformations of Bodily Ideology.” In Performing Death: Social Analysis of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, edited by N. Laneri, 287–298. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Robb, J. 2013. “Creating Death: An Archaeology of Dying.” In Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial, edited by L. N. Stutz, and S. Tarlow, 441–457. Oxford: Oxford Press.

- Rova, E. 2014. “An Overview of The Kura-Araxes Culture in the Shida Kartli Region of Georgia.” Paléorient 40 (2): 4769.

- Rova, E. 2018. “Burial Customs Between the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age in the Shida Kartli Region of Georgia,” TÜBA-AR: 37–56.

- Sagona, A. 1984. The Caucasian Region in the Early Bronze Age (British Archaeological Reports, International Series 214). Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Sagona, A. 2004. “Social Boundary and Ritual Landscapes in Late Prehistoric Trans-Caucasus and Highland Anatolia,” in A View from the Highlands; Archaeological Studies in Honour of Charles Burney (Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 12), edited A. Sagona, 475–538. Louvain: Peeters.

- Smith, A. T. 2019. “Bronze Age Metaphysics: Burial and Being in the South Caucasus.” In Constructing Kurgans. Burial Mounds and Funerary Customs in the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia During the Bronze and Iron Age. Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Florence (Studies on the Ancient Near East and the Mediterranean 4), edited by N. Laneri, S. M. Celka, and G. Palumbi, 1–20. Roma: Arbor Sapientiae.

- Stöllner, T. 2021. “Sakdrisi and the Gold of the Transcaucasus.” In The Caucasus; Bridge Between the Urban Centers in Mesopotamia and the Pontic Steppes in the 4th and 3rd Millennium BC, edited by L. Giemsch, and S. Hansen, 101–118. Regensburg: Verlag Schnell and Steiner GmbH.

- Zalaghi, A., Maziar, S., Aghalari, B., Jayez, M., Marjan Mashkour, Jayez, M. 2021. “Kohne Tepesi: A Kura-Araxes and Parthian Settlement in the Araxes River Basin, Northwest Iran”, Journal of Iran National Museum 2.2: 49-74.