Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

I used an interpretive review of Global North liberal market literature to construct an analytical framework that speaks to the different applied logics of planning, property development, and politics. On closer inspection, the competition among these logics generates several different styles of—and outcomes from—planning. The framework decenters urban planning practice within processes of placemaking. It suggests that, in addition to negotiation and leadership, imagination, creativity, and entrepreneurship can usefully feature more in urban planning education and practice.

Takeaway for practice

Planning educators and practitioners should resist the temptation to reduce urban planning to project management. Practice increasingly may be exposed to the immediacy of digital social media and pressure-group politics. The education and training of planners should incorporate a greater appreciation of the logic of property development and the skills needed to negotiate with developers and persuade politicians as well as greater use of imagination, creativity, and entrepreneurship.

Patterns of development often elude the best of urban planning intentions. This is apparent to all involved in planning practice. However, the disconnects among the logics of planners, property developers, and politicians in patterns and processes of development have rarely been elaborated in much detail in planning theory. Though the politicized nature of planning and the locational conflicts it contends with are recognized (K. R. Cox, Citation1979; Lake, Citation1987), there remains a need for planning literature to appreciate the decision making of property developers (Charney, Citation2012; Coiacetto, Citation2000) and politicians alike.

The contributions I make in this review are threefold. First, against enduring unease over a divorce between planning theory and practice (Alexander, Citation1997; Brooks, Citation2017; Whitehead, Citation1990; Yiftachel & Huxley, Citation2000), I developed a cross-disciplinary framework for understanding the partially complementary rationales of planning, property development, and politics in the development process. Political economy accounts provided high-level abstractions regarding the interactions among planning, development practices, and politics (Haila, Citation1991; Logan & Molotch, Citation1987; Scott & Roweis, Citation1977). I augment these accounts here with an interpretive review of literature that provides the basis for generalizing about the logic or rationales of planners, property developers, and politicians. If planning theory directs attention to what is important (Forester, Citation1989, p. 137) in the “interplay of the technical, political, and moral issues” involved in development (Beauregard, Citation2020, pp. 1–2), then it is important to understand planning logic as it competes and combines with that of property developers and politicians. The combinations of these logics in different styles of planning speak to aspects of the structure and agency and idealism and realism (pragmatism) emphasized in planning theories (Allmendinger, Citation2002; Hoch, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation1980). Second, I identify, in stylized terms, why patterns of development elude the best intentions of urban planning because of contestation among the decision making of planners, property developers, and local politicians. It is the (dis)connects among these three sets of actors that ensure that the value of urban planning can seem obscure. Third, a subsidiary contribution of my review is to demonstrate the value of integrating insights from urban planning with those of other disciplines concerned with space and place (Phelps & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2008).

In the following sections, I detail the methodological basis of this review covering three major liberal market Global North planning systems. I then elaborate the different decision-making rationales of planning, property, and politics, illustrating them with reference to literature pertaining to these settings. Comparison of the three logics and their combinations revealed a variety of urban planning styles, which has important implications for planning theory, practice, and pedagogy.

Methods

The literature from which I offer an interdisciplinary and international interpretation of the logics of planning, property, and politics is drawn from the post–World War II experience in the liberal market Global North planning systems of Australia, England, and the United States. I offer here an interpretive rather than a systematic or metareview, where the value of the former lies in offering fresh interpretations of familiar subject matter, perspective on the meanings generated from taken-for-granted practices, and improved communication between communities such as academic disciplines (Eisenhart, Citation1998).

In terms of theory building, this interpretive review drew on sources within each of the urban planning, real estate, urban geography, politics, and sociology disciplines. I used the literature outside of urban planning selectively to infuse a contribution to urban planning theory with related and relevant conceptualization. In terms of planning practice, I drew together the literature that spoke most consistently to an understanding of the spatial and temporal decision making employed by planners, property developers, and politicians. These decision-making logics might have arisen out of the practical application of reason rather than being essential and immutable.Footnote1 The literature on the temporality of decision making apparent within planning, property development, and politics is modest enough to allow a relatively complete survey. The literature pertaining to the spatial dimensions of planning, property, and political deliberations is extensive, so my review here is selective.

Consideration of the interactions of planning, property development, and political practice in these three nations allowed a comparison of the challenges of planning for contrasting rates and absolutes of population change. In England, in a planning system famed for its urban containment, modest population, and employment growth, pressures have been accommodated in one of two modes: new towns and incremental extension of established urban areas. In Australia and the United States, immigration-fueled rates of population growth have been associated with extensive development contiguous with established urban centers (Clawson & Hall, Citation1973; Tomlinson, Citation2012).

The review-based framework presented here is intended as a contribution to urban planning theory limited to these and other Global North planning systems. First, the framework does not bear extension to Global South conditions. Second, the stylized analysis presented runs the risk of simplifying what is a variety of rationales found across groups of actors in the development process (Phelps, Citation2021). Third, as a summation of some of the realities of processes of urban (re)development, the framework has underplayed the voice of citizens as the recipients of particular styles of urban planning in the discussion presented below.

The Contrasting Logics of Planning, Property Development, and Politics

Patterns and processes of urban development are highly revealing of the contrasting applied logics or rationales of urban planners, property developers, and politicians. Each set of actors shaping the built environment has an interest in the creation and maintenance of a sense of place. Each is also bound by timing: the temporal rhythms of plan making, budgetary decisions, short-term and long-term shifts in aggregate demand and in electoral cycles, and swings in public sentiment. Yet, in their practical application, there is often a tension among the logics of planning, property, and politics. For example, the terms commonly used to decry the outcomes of planning for population and employment growth—sprawl, haphazard and leapfrog development—speak to the illogic of development at the urban fringe (J. L. Grant, Citation2017). It is important, then, from both theoretical and practical points of view, to appreciate how competing rationalities play into styles of urban planning and their outcomes.

Three Logics Compared

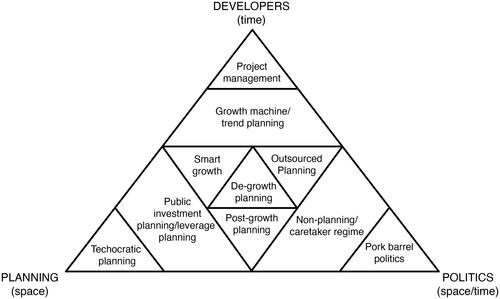

presents stylized contrasts among how planning, property development, and political decision making works, drawing on relevant accounts. These decision-making logics are applied. They could be termed rationales or rationalities that rest on practical reasoning that evolves over time. Although it is important to note, as I do below, that the different actors are multiply invested in particular logics, they each also are relative, not absolute, and are context sensitive in ways that produce a variety of outcomes. Indeed, these sets of stakeholders have been unified in their interest in both space/place and time, or questions of both where and when development takes place. It is surprising, then, how little interdisciplinary dialogue there has been regarding this source of unity. It is also surprising how little productive coincidence in the three logics there often is in practice and how often urban planning is unable to win the day in outcomes that approximate the compromises sought in the planners’ triangle (Campbell, Citation2016). This lack of coincidence in the decision making apparent in planning, property development, and politics in thought and practice underlines the pervasiveness of locational conflict (K. R. Cox, Citation1979) and the fact that “space will always represent an independent constraint upon the allocation of resources” (Pinch, Citation1985, p. 169).

Table 1 Planning, property and politics compared.

Planners have a logic that, on balance, is spatial (Charney, Citation2012). The attitude of planners might be described as idealistic when aiming for the successful spatial arrangement of activities and land uses where the definition of idealism taken from the Oxford Languages Online Dictionary (Citation2024) implies the (possibly unfair) critique of their holding “the unrealistic belief in or pursuit of perfection.” Footnote2 Developers, on balance, are interested in the timing of development, albeit this itself is complicated by multiple rhythms of business, property, and macroeconomic cycles (Brown, Citation2015). Following the Oxford Languages Online Dictionary, the attitude of developers might, on balance, be described as one of realism, “of accepting a situation as it is and being prepared to deal with it accordingly.” The decision-making rationales of urban planning and property development are apparent in key discipline-rooted accounts. Insights on the decision making of local politicians can be drawn from a diverse body of work in urban politics and political geography. Politicians can be considered equally disposed toward space/place and time. However, their logic is rarely principled but opportunistic, defined in the Oxford Languages Online Dictionary as “the taking of opportunities as and when they arise, regardless of planning or principle.”

A further aspect of the simplification in is that these logics are not as mutually exclusive in theory as they are presented here for the purposes of exposition. Nor are they mutually exclusive in practice, not least because “urban planning involves coordination in time as well as space” (Fagin, Citation1955, p. 298). It is important to bear in mind, for example, that each of the categories of planning, property development, and politics are internally heterogenous and include actors (individuals, local governments, businesses) that have logics that are variations on the themes in . Lack of recognition of this heterogeneity of the development industry results in the adoption of unhelpful senses of the “notional developer” (Adams et al., Citation2012, p. 2578) and hinder “appreciation of the industry that planners are meant to direct and regulate” (Coiacetto, Citation2000, p. 353).

The rationalities of planning, property development, and politics are thus far from entirely antithetical. After all, planners, property developers, and politicians each have a keen interest in and knowledge of place that they each seek to mobilize. However, geographic and historical imaginations (Phelps, Citation2021) play into the logics of each of these sets of actors with different emphases that compromise the ability of each of them to realize their ambitions. This includes planning’s own ideal of producing equitable, socially, and economically sustainable places (Campbell, Citation2016). The relationships among the three logics can be summarized in terms of styles of urban planning and their associated outcomes depicted in . and the accompanying discussion draw not only on the planning literature but also relevant real estate, urban geography, politics, and sociology literature. In some respects, then, what urban planning is, or can best be, is reflected in the combinations found in .

The “interface between the public and private sector…creates not only political attrition but also considerable delays (and costs) in land development” (Drewett, Citation1973, p. 175). Moreover, the three logics have recursive effects on each other (Warner & Molotch, Citation2000). For example, urban planning as an ongoing process has recursive effects on the valuation of land and property that landowners and developers respond to swiftly in ways that public authorities often are unable to capture for the benefit of new community building (Phelps & Miao, Citation2023). Political expediency creates uncertainty in decision making when compared with the continuity and certainty generally offered by urban planning (Hall, Citation1980). Planning, development, and political decision making may dominate in different local contexts involving different absolute scales and rates of population growth (or decline) and political reception of them.

Planners are only able to fully exert their ideals for the spatial arrangement of activities and infrastructure in some limited styles of urban planning. Historically, planning logic was applied with political support in perhaps its purest form in the technocratic comprehensive redevelopment of inner-city communities with tokenistic efforts at public participation (Arnstein, Citation1969) or the planning of new communities with new populations by private or public development corporations during the 1950s and 1960s (Wakeman, Citation2016). Otherwise, planning rationales come to the fore as public investment or leverage planning in which the assembly and remediation of land may be needed to mobilize the property industry in economically marginal or derelict localities (Brindley et al., Citation2005).

Political leaders with large or unassailable majorities may be insulated in ways that allow them to align over the longer term with the aspirations of planners and developers. However, the political logic of expediency is visible at its most extreme in pork barrel politics. Here, in settings that can span the range of growth pressures, the resources and externalities conferred upon communities by urban planning are distributed in inequitable ways by politicians to favor parts of the electorate, including through the likes of exclusionary zoning practices. Otherwise, in settings in which anti-growth sentiments prevail, political expediency may take the form of caretaker local political regimes (Stone, Citation1989) or the decision-making paralysis of nonplanning. The southeastern region of England is a good example here. For several decades now, planning for population growth has taken place in a context of substantial political and popular rejection of new development by established communities (Murdoch & Abram, Citation2017; Phelps, Citation2012a; Valler & Phelps, Citation2018; Valler et al., Citation2012). By today, in the same region, political expediency has reached absurd proportions: a combination of the absence of strategic planning at either county or regional scales, the failure of local planning authorities to cooperate (despite a duty to do so), and central government reducing local planning to the release of sufficient land for housing number targets has produced nonplanning.

In some instances, planning decision making may come to mirror the interest of developers in timing, being little more than project management of numerous subdivision developments. This appears common in those contexts in which population growth has been extremely rapid. Even so, much can depend on the structure of the development industry and landownership locally. For example, large, well-funded national or international property developers with large sites typically are able to take a greater interest in placemaking with decision-making rationales closer to those we associate with the best intentions of public-sector urban planning. The temporal logic of the development industry is also apparent in trend planning (Pickvance, Citation1982) and growth machine dynamics (Molotch, Citation1976), where stability of political control of local governments provides for large releases of developable land and permissive urban planning with a strongly developer-influenced flavor.

Potentially, the most productive overlaps in the logics of planning, property development, and politics that exist in principle can result in varieties of planning found at the center of . These styles could be termed collaborative to refer less to the integrity of the processes involved than to the sorts of outcomes aimed for and achieved (Healey, Citation1997). Some of these styles may entail a strong understanding between politicians and planners in nascent post-growth planning ideals (Savini et al., Citation2022). More commonly at present, popular concerns over the sustainability of business-as-usual patterns and processes of development have surfaced in smart- or de-growth planning–style fusions of planning, property development, and political decision making. Finally, there are instances where, either due to a lack of resourcing or by default in the face of successful legal challenges, planning has been outsourced to developers and their planning consultants.

The Spatial Logic of Urban Planning

Although an interest in the when of development is hardly absent from public-sector urban planning, on balance, the primary focus of planners has been on the where of development.

If planning has a value under conditions of uncertainty, irreversibility, indivisibility, and interrelatedness (Hopkins, Citation2001), the focus of attention for public-sector urban planners has been on the latter two conditions, which signal their focus on place. Here planning is multiply attuned to the spatial arrangement of development including the separation of incompatible land uses and the containment and sequencing of development. The primarily spatial deliberations of planners are communicated in the main means deployed by public-sector planners: plans that map current and future land uses, protect environmentally sensitive lands, limit future development, and identify sites and routes for infrastructure. In the Global North liberal market planning systems considered here, this spatial emphasis in planning decision making has shed much of its strategic aspect to become more narrowly focused on regulation, prompting the question: Who exactly plans places (Peiser, Citation1990)?

Fagin (Citation1955) summarized the planning justification for sequencing in terms of five needs: to economize on the costs of municipal facilities and services, to retain control over the eventual character of development, to maintain a desirable degree of balance among various uses of land, to achieve greater detail and specificity in development regulation, and to maintain a high quality of community services and facilities. From an Australian perspective, Gurran (Citation2011, p. 52) noted that “when there are no mechanisms to control sequencing of urban development, the result can be a degraded landscape.” Sequencing is thus important to the quality of planning and yet, despite sequencing of development being a taken-for-granted element of growth planning practice in the liberal market contexts considered here, it has received scant academic attention in major texts (F. S. Chapin, Citation1965; Hack, Citation2018). We can speculate whether this is an analytical oversight or a reflection of the realities of development patterns and processes.

The spatial sequencing of new development can be challenging, but it was a notable triumph of the planning of new urban extension communities in the modest population growth context of South Hampshire (United Kingdom) from the 1960s to the 1980s (Phelps, Citation2012a). However, spatial sequencing in settings of rapid population growth may be impossible. The uncertainties surrounding valuations, ownership, and expectations of land are so significant that they often preclude ideal spatial sequences of development or generate development on multiple fronts at the same time, as Phelps and Nichols (Citation2022) described in the case of the planning of growth at the edge of Melbourne (Australia). Here and in other rapid population growth settings such as Miami–Dade County (FL), the lags in services and infrastructure are endemic and prompt a parallel search in urban planning practice and policy for concurrency of housing development and transportation, environmental, and social infrastructure (Phelps, Citation2015). Thus, sequencing, in the guise of desire for concurrency, is hardly universal as part of growth management across the United States (T. S. Chapin, Citation2012).

Planners’ interest in the timing of development is communicated in the desire for its spatial sequencing. Sequencing responds to the indivisibilities and interdependencies that lie at the heart of the making of coherent places. However, the problems of overload, urgency, and turbulence (Friend & Hickling, Citation2005) can be so great in some contexts that urban planning (whether in the form of strategic spatial planning or statutory development control) is openly spoken of in practice circles as project management. This is an overwriting of the spatial rationale of planning with the temporal rationale of developers (at the apex of ).

The Temporal Logic of Property Development

Property developers share an interest in the spatial arrangement of development with urban planners. Their acquisition of land is a major part of their profitability (Brown, Citation2015). Developers are unable to be fully “systematically rational” in land acquisitions (Drewett, Citation1973, p. 170). They are reliant for their knowledge of place (including the availability, suitability, and development value of land) on networks of specialist advisors—valuers, public and consultant planners, and water and environmental engineers—with an intimate knowledge of place. However, their interest and agency in placemaking is constrained by structural conditions (Charney, Citation2012).

The growth of capitalist economies has been both eventful and contradictory (Sewell, Citation2008). Capitalist economies do not grow in the linear fashion assumed in the forecasting of trend planning (Pickvance, Citation1982). Instead, economies grow rhythmically in several ways that the development industry must respond to. There are regular business cycles (in aggregate demand and supply), long-run transformations in societal values (including the moral economy of land value capture and compulsory purchase), and structural economic changes (Barras, Citation1987; Roulac, Citation1996). Successful timing of development in relation to these partially coincident short- and long-term fluctuations can generate exceptional or windfall profits. By the same token, (mis)timing presents an existential threat to developers (Brown, Citation2015) manifest in numerous zombie subdivisions in the United States and Australia (Holway et al., Citation2014; Kolankiewicz et al., Citation2022). In Australia, where most state planning authorities typically allocate large future developable land supplies by international standards and have been very permissive of residential development in a bid to keep land and house prices affordable, speculation and cyclicality in the market have not decreased. The 41 cycles in housing market development evident across six Australian capital cities from 1993 to 2018 gives some indication of the volatility that can exist for developers (Brugler et al., Citation2020).

Timeliness produces an efficient land development process (Kone, Citation2000). More to the point, “real estate development is a game of large numbers, and timing plays a huge role in profitability,” and at every step the developer hopes to eliminate uncertainty and reduce risk (Brown, Citation2015, p. 189). The twin interests in timeliness and space/place are facets of development over which planning and property logics could (in principle) and ought to (in practice) coincide. However, the spatial emphasis of public-sector urban planning is often trumped by the intrinsic dynamic of the property development industry oriented toward tradability, divisibility, and mobility (Haila, Citation1991). Indeed, the development process itself can be seen as a set of time-linked decision chains (Drewett, Citation1973, p. 165). Thus, even though developers work with pipelines of 10 to 15 years of spatially heterogenous land acquisitions and sites under development, the temporal sequencing of development trumps the spatial sequencing of development, not least because “supply-side and place-specific considerations…are crucial elements in explaining…cyclical development patterns” (Charney, Citation2012, p. 730).

Indeed, developers are multiply sensitized to timing as they acquire land speculatively for the long term but also in the medium term before and during development. Speculative investments designed to deliver windfall profits from land value uplifts have their own timescale and dynamics that are detached from the regular valuations and purchases associated with ongoing development opportunities related to aggregate demand for types of housing or commercial premises (Brown, Citation2015). Regarding the medium-term horizon on which land is held prior to and during development, the evidence from Greater Melbourne has also suggested that profitability can be related to the costs of timely connection to utilities such as sewer, water, electricity, and roads. The profitability of smaller, less well-resourced developers may be dependent on timing vis-à-vis the actions of larger developers who bring infrastructure connections and a place brand on which to coattail smaller-scale and less prestigious development projects (Phelps & Nichols, Citation2022). The sensitivity of developers to timing also depends greatly on the extent to which they are leveraged with respect to finance (Brown, Citation2015). In general, these considerations determine that developers are interested in the speed of cash flow as well as the timing of development to market (Drewett, Citation1973).

The acute sensitivity of developers to time has ensured that they also exert agency in the development process along this dimension. This, at times, may confound the spatial arrangements and sequencing of developments desired by planners. They can “speed up or slow down land development, infrastructure provision, and building production” (Brown, Citation2015, p. 27). Notably, in southeastern England, exertion of this agency has generated concern about excessive land banking by developers as one factor contributing to high house prices, though it has also been observed equally that developers may bring forward cheaper land from their stocks to maintain house prices where demand is price inelastic (Drewett, Citation1973). In this way, and despite property developers working to time frames that could hardly be described as short, “timing has a major impact on the ability to steer urban development” (Charney, Citation2012, p. 729).

The Political Logic of Expediency

Political leadership is important to plan generation and implementation (Han et al., Citation2021), but locally elected governments are not neutral arbiters of the allocation of resources (Pinch, Citation1985). Moreover, the logic of political decision making rests on popular sentiment that itself is reflective of the actions of property developers and urban planners.

Politicians’ feel for the geography of their electorates is innate (as representatives of resident voters), immediate (with elections which are frequent by the standards of planning or property development), or even instant (in response to special interest groups and social media). Political decision making regarding urban planning and other policies with distributional consequences are condensed in instances of turf politics that reveal deeper structures of class conflict (K. R. Cox, Citation1979; K. R. Cox & Johnston, Citation1982; K. R. Cox & McCarthy, Citation1982). Nevertheless, the surface manifestation of such decision making is expediency with respect to space and time. Where developers could be regarded as tenacious with respect to timing and urban planners considered about the spatial arrangement and sequencing of development, politicians are doubly opportunistic with respect to both time and space/place. The spatial arrangement and sequencing of development and its timing are themselves fungible sources of capital for politicians. It is in this connection that I use the term expediency to describe political decision making that is attuned to mobilizing both the where and when of development as it suits the garnering or maintenance of votes.

First, local government politics is expedient regarding where development takes place. The territoriality of local government is critical to the exercise of democracy and the efficient delivery of services. It also is exploited in ways that have significant distributional consequences that remain only partially elaborated in the urban planning literature, even if they are well known to every practicing planner and elected representative. From a political perspective, controversy over localization can be understood as a power contest over territory and land use; as such, it is always a potential source of conflict in society (Strandberg, Citation2000, as cited in Boholm & Löfstedt, Citation2013). Geography literature on the politics of public service provision focuses on the distance decay effects of positive and negative externalities from centers of population (Pinch, Citation1985). However, it has less to say about political decision making in relation to jurisdictional boundaries. One reason why we have an inadequate consideration of the boundary-oriented effects of political decision making is that “we gravitate to the heft and bulk, the easily identified center of…settled places” (Casey, Citation2017, p. xiii). The effects of positive and negative externalities and votes decay with distance in ways that politicians manipulate with respect to both jurisdictional centers and boundaries: the latter results in political bargaining for jurisdictional boundaries (Phelps & Valler, Citation2018; Valler et al., Citation2014).

Because “boundaries are central to the raising and spending of local revenue” (Briffault, Citation1995, p. 1129), political expediency has a positive gloss in the opportunistic approval of developments that bring jobs to, or enhance local economic development opportunities for, communities and attract votes as a consequence. This is the case generally across the United States in a pattern that Molotch (Citation1976) labeled growth machine politics and in which good planning comes to be understood as the permissive allocation of land for development. This is a scenario in in which the logics of planning, development, and politics can be completely aligned in urban planning as project management or otherwise closely aligned as growth machine or trend planning. One effect of this situation in which political and urban planning rationales become so closely aligned with those of developers is that new leapfrog patterns of urban fringe development can appear unplanned (Fisher, Citation1933). In this context, the spatial sequencing of development sought by urban planners becomes fundamentally impossible: It is being overridden by the manner in which developers lobby to time their projects to maximize returns. Arguably, growth machine politics has been most apparent in former rural county and new suburban city jurisdictions across the United States (Phelps & Wood, Citation2011). In settings where the NIMBY sentiments of existing communities are notable, local politics may incorporate tradeoffs of accommodating employment land uses that maintain property taxes and residential values and amenity under stable local political regimes (O’Mara, Citation2015; Phelps, Citation2012b, Citation2015; Teaford, Citation1997).

However, the boundaries of local governments are deeply implicated in the generation of spillovers (Briffault, Citation1995). In communities in which anti-growth sentiments prevail, spillovers of all sorts are the source of negative forms of opportunistic political decision making concerning the planning and permitting of development and the siting of facilities. It is here that political expediency most rubs up against the idealism of both public choice theory regarding the efficiency of the market for local government–provided services (Tiebout, Citation1956) and urban planning regarding the optimal siting of facilities in relation to efficiency/equity tradeoffs (Teitz, Citation1968). In contexts such as southeastern England, where NIMBY and build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone (BANANA) sentiments prevail, politicians seek to minimize the loss of votes from the siting of locally unwanted land uses (LULUs).Footnote3 Here environmental rationalities are at least as strong as growth rationalities in urban planning policy but with distinctive variations in politicized local planning cultures (Murdoch & Abram, Citation2017; Valler & Phelps, Citation2018). Indeed, so strong are these sentiments today across southeastern England that a basic need such as housing has come to be regarded politically as an externality to be planned away (Breheny, Citation2001). In these contexts, perceived externalities frequently are dumped on neighboring constituencies when located at the extremities of local government jurisdictions. Examples of this can be found across South Hampshire and elsewhere in southeastern England where much of the residential and employment land allocations to meet forward estimates of growth and central government housing targets in the past 60 years have reflected a political search for the least worst voting outcomes. As a result, these land allocations are to be found at the boundaries of local government jurisdictions in patterns that have exacerbated urban sprawl (Phelps, Citation2012a). The South Hampshire evidence also suggests that the applied planning rationale of buffering of LULUs from existing populations with the designation of strategic gaps in development can become orthodoxy with little in the way of environmental or planning justification (Lyle & Hill, Citation2003). Instead, the boundaries of—and gaps internal to—jurisdictions become the focus of politicians’ attempts to be (re)elected (Phelps, Citation2012a).

Second, in its march to the insistent rhythm of electoral cycles that are shorter than the rhythms of plan making and development projects, politics is expedient regarding the when of development. One effect of the expediency of politics with respect to time is the impossibility for urban planning to be comprehensive since “politicians are rarely willing to commit themselves to let general and long-range goals statements guide their consideration of lower-level alternatives” (Altshuler, Citation1965, p. 186). Indeed, the “irrationalities of voter behaviour render the political arena a less than perfect reflection of public preferences” (Brooks, Citation2017, p. 149) such that politicians prefer vagueness and the flexibility it affords. However, such vagueness has significant consequences for urban planning outcomes. Hall’s (Citation1980) Great Planning Disasters found that the majority share of uncertainty affecting planning came from the politicized nature of decisions affecting planning, not uncertainty from planning forecasts or in the environment (including property development cycles). The sorts of uncertainties planning deals with primarily are external to the planning system, such that we can speak of the contingent and robust plans made under conditions of uncertainty internal and external to planning processes themselves (Chakraborty et al., Citation2011). The expedient exploitation of space and time by politicians is no accident; as Boholm and Löfstedt (Citation2013) observed for the siting of LULUs, these facilities generate issues of trust that is far easier to destroy than to generate over time, leading politicians to defer decisions involving spillovers. The deferral of major infrastructure decisions has been apparent at the national level in England. However, it is also apparent at local scales in southeastern England. In South Hampshire the political rationale that has guided planning deliberations for major residential land use allocations has typically been one of deferral into a future in which many of the sitting politicians will no longer be in search of votes because they will be retired or deceased (Phelps, Citation2012b).

Implications for Urban Planning

There often is much suspicion and misunderstanding of each other across the local government planner, politician, and private property developer sectors (Peiser, Citation1990). Yet the partial coincidence of planning, property, and political decision-making rationales suggests that concerted and joined-up thinking across the disciplines and actions across these practice communities is possible and almost certainly would result in better placemaking. It is important, then, to reflect on some of the implications of these competing logics of planning, property development, and politics for urban planning practice, theory, and pedagogy.

Implications for Urban Planning Practice

For Fagin (Citation1955, pp. 298–299), “until…planning invents greatly improved methods for regulating the timing of urban development, many attempts at space coordination must continue to fail.” Some evidence for the improved regulation of the timing of development is visible in the project management style of urban planning I allude to above. Here, the challenges of urgency, overload, and turbulence (Friend & Hickling, Citation2005) have driven the triaging of development permitting processes, the creation of urban planning teams dedicated to prioritizing certain developers, and expediting particular individual projects. However, there are significant issues of going too far with “planning as project management” because it involves “actions in the present that connect to the future only by directly creating it” (Hopkins & Zapata, Citation2007, p. 5) and may forego longer-term and more holistic approaches to placemaking.

What urban planning can achieve in terms of placemaking is related to the adequacy of land value capture measures. This, in turn, depends on the negotiation and bargaining skills of planners to close funding gaps that open in the valuations made by developers and those made by public authorities for the purposes of compensation and provision of the transport, environmental, and social infrastructures necessary for the building of sustainable communities (Phelps & Miao, Citation2023). As a result, urban planners “require an ever more sophisticated understanding of development to help them realise how they might best influence developer activity” (Adams et al., Citation2012, p. 2578).

At least a couple of societal developments offer some hope that a more principled, less expedient interest in place can come to the fore in the patterns of political decision making described above. First, there is evidence to suggest that politicians have become increasingly interested in place branding (Pasotti, Citation2010). To an extent, this reflects the brute bankability (ability to leverage finance) of some city brands. However, to the extent that city brands are not the weak competition (on the basis of factor costs) response to the branding activities of other cities but rather the strong competition (based on inimitable assets and skills; K. R. Cox, Citation1995) encompassing the enduring social, economic, and political complexion of a city, including its urban planning culture (Neuman, Citation2007), politics may yet contribute to better placemaking. Possibilities for political solidarity at the metropolitan scale may also hold promise in curtailing some of the worst excesses of political expediency within and among individual local governments. This is the promise of new community building in a web of intermunicipal collaboration or in the absence of jurisdictional walls in Orfield’s (Citation2000) American Metropolitics and Frug’s (Citation2001) City Making. These intermunicipal alliances exist, though they have mainly reshaped the distribution of resources from city to suburbs rather than curtailing the spillovers among suburban municipalities (Kim, Citation2019).

However, these aspirations for local government politics seem forlorn in the face of the challenges to urban planning practice presented in some contexts by the increasing divorce of local politics from either local urban planning deliberations or local developer interests in the face of population growth pressures. The use of social media by interest groups to influence, and regular voters to respond to, political decision making in local government with respect to new urban development means that local politics can be reduced to the paralysis of nonplanning. The best example of this is contemporary local plan making across southeastern England. Here, urban planning cultures are desperately in need of new ideas to help shape the mobilization of real-time, big data, and social media platforms to more constructive public participation ends. City government in Helsinki (Finland) has been able to mobilize the public’s high levels of trust in government and familiarity with mobile devices and digital platforms to generate high levels of public participation in policy deliberations. The tradition of grassroots politics in Spain has been mobilized in a recent shift in smart city policies in Barcelona (Spain) toward mass public participation based on open city data and digital platforms. This has allowed experimentation in the deliberations initiated by fundamental disagreements rather than communication or consensus (Aragón et al., Citation2017). These political cultures cannot easily be transplanted or fashioned elsewhere, so alternative approaches are much in need if local politicians are to engage more meaningfully in modes of joint decision making with planners and property developers.

Some measure of the competition among planning, property development, and political decision-making rationales may be overcome from the greater license that might be given to the property development sector, albeit the best-resourced, legacy-seeking, or community builder portion of what is a heterogenous sector. It is salutary to remember the origins of new town building in private enterprise in both the United Kingdom and the United States. In these instances, private-sector new community builders historically were the promoters and bore significant risks associated with the developments that have since come to be regarded as exemplars of good urban planning practices and principles, including the capture of land value increases for the provision of amenity and social welfare (Weiss, Citation1987).

Implications for Planning Theory and Pedagogy

To the extent that suspicions among urban planning and development practitioners and political leaders feature in planning pedagogy, this can be unfortunate and counterproductive from the point of view of communicating an understanding of what planning is and does and what is to be gained in terms of placemaking in myriad instances of development. The major analytical approaches to understanding urban land and property dynamics are not as mutually exclusive as often presented. Urban planning theory can be integrative of these interests in ways that present the dynamics involved neither as entirely exceptional nor entirely the same as the political economic dynamics of capitalism in general (Haila, Citation1991). In this connection, my attempt to distinguish the logics of planning, property development, and politics and some of their overlaps is intended to aid analytical understanding of what can be expected in urban (re)development processes.

Important contributions notwithstanding (Ambrose, Citation1994; Healey, Citation1991, Citation1992), in broad disciplinary terms, there has been a significant gap among the characterization of property in the disciplines of urban planning, geography, and sociology and that in the disciplines of property, applied economics, financial analysis, and valuation (Charney, Citation2012; Guy & Henneberry, Citation2000). Theoretical academic discussions of urban planning retain a large measure of normative idealism when compared with the theoretical realism of property development and (to some extent) the pragmatism of urban planning practice. Planning and development are intimately linked: Development processes are shaped by planning regulations, whereas planning cannot help but adjust to development practices and processes (Charney, Citation2012). Thus, Hopkins (Citation2014) has argued for a greater emphasis to be placed on time rather than space in urban planning theory. This likely would help overcome some of the sharpest divisions drawn in the logics of urban planning, property development, and politics described above. Nevertheless, any incorporation of an appreciation of time into planning education and practice needs to be tempered with a recognition of the limits of equating urban planning with project management.

From the standpoint of property development practice, urban planning can often be conflated with politics. Indeed, from the point of view of politicians, the ability to elide political and planning decisions has been one of the reasons why planning often ends up taking the blame for public discontent over development proposals and outcomes (M. Grant, Citation1999). Little wonder, then, that there generally has been greater appreciation of the politicization of urban planning in planning scholarship than of the potential connections between the interests of planners and developers described above. The politically inflected nature of urban planning has been given prominent consideration in general treatments of the national character of planning systems (A. Cox, Citation1984; Healey et al., Citation1988), though less so in ways that shed analytical light on the concrete difficulties faced in local planning practice. Here it is apparent that although political leadership can be important to the success of plan generation and implementation, “municipal leadership changes with electoral cycles: Plan-making is iterative, and plan implementation is incremental. These multiple temporalities can lead to synergies or contradictions between plan objectives and strategies and elected officials’ interests and priorities” (Han et al., Citation2021, p. 211).

The relationships among planning, property development, and politics presented here are mediated by an expanding array of specialist knowledge providers found in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors. Urban planning systems have themselves become more complex with more regulations, standards, and responsibilities thrust upon them that require the sourcing of this specialist expertise. Developers also rely extensively on expert knowledge providers from public-sector and consultant planners, civil and environmental engineers, valuers, and the like. A primary role in re-enchanting suburban living in the United States has been accorded to exchange professionals (Knox, Citation2009), yet it is clear elsewhere that the bureaucratic administration of new development can also leave little room for intermediaries to exert much of a system- or market-changing effect (Phelps et al., Citation2023). The role of intermediaries in shaping a greater or lesser coincidence in the rationales of urban planners, property developers, and politicians can usefully be better understood. The system-maintaining or -reforming credentials of urban planning and urban planners (Marcuse, Citation1976) must be seen in the context of this increasing roundaboutness of the policymaking and implementation process (Majone, Citation1989) as it applies to the production of the built environment.

Conclusion

In this review I have discussed the competing decision-making logics of planning, property development, and politics as one way of understanding some of the limits of what urban planning can achieve in practice. Though these logics are by no means entirely antithetical, the challenge remains for urban planning and urban planners to find their place in the making of place.

Read positively, the fact that the decision-making rationales of planning, property, and politics are at least partly reconcilable—in the location and timing of development—means that public-sector urban planning continues to have a value as perhaps the activity seeking integration of otherwise competing rationales and to avert the worst possible development outcomes. Here, planning’s role in shaping development processes—in shaping places—emerges less as one of neutral coordination but as a guardian of a residual sense of the public interest. However, that sense of the public interest is increasingly fractured, and the possibilities for securing it appear increasingly to lie outside of representative local politics and public-sector statutory planning processes (Phelps, Citation2021).

Read pessimistically, the dilution of planning decision-making rationales in the (re)making of places is to be expected, and the greater failures in this respect can lead to the impression that development is hardly planned at all. We might say that plans and planning appear to fail because they are at the center of the recursive relationships among planning, property development, and politics I have outlined here. Plans and planning processes add their own unintended and unanticipated effects into spatial and temporal patterns of growth and ensure that capitalism’s contradictions gain latitude over time (Harvey, Citation1985; Scott & Roweis, Citation1977). In these respects, the temporalities of the governmental superstructures of capitalist economies within which urban planning and political decision making exist and through which developers seek to have effect could usefully be made the focus of future urban planning scholarship (Abram, Citation2014).

Greater integration of insights relating to planning, property development, and local government politics is important in urban planning education if graduates entering the practice are to be properly appraised of the compromises that they will face in their daily decision making. The analysis presented here decenters urban planning within diverse processes of—and outcomes from—development. Among the development outcomes that may yet best embody smart, post-, or de-growth planning are those collaborations in which urban planning thought and public-sector practice may not be as central from a pedagogical perspective as we have commonly regarded. If the planning imagination is fundamentally distributed (Phelps, Citation2021), we may have to accept that the logic that urban planners seek to apply may not be the most important in sustainable placemaking. That said, the collaborations among planners, property developers, and elected politicians that are possible underline the opportunities for urban planning to be taught and accredited as an activity of imagination, entrepreneurialism, negotiation, and leadership capable of productive alignment with both property development and politics.

Acknowledgments

I thank the three reviewers and the editors for their constructive comments on previous drafts of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicholas A. Phelps

NICHOLAS A. PHELPS ([email protected]) is professor and chair of urban planning and associate dean international in the Faculty of Architecture Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. He is also a visiting professor in the School of Architecture at Southeast University, China.

Notes

1 One curiosity beyond the scope of this article is how the practical reason apparent in planning policies may become locked in, giving the impression of immutability.

2 The qualifier on balance is important here. Clearly there will be some instances where urban planning has a logic that is realistic, where politicians are idealistic, or where developers are better characterized as being opportunistic, for example.

3 These terms should be used with care because they have pejorative connotations that imply optimal solutions rather than what are actually complex, multiscalar societal tradeoffs.

References

- Abram, S. (2014). The time it takes: Temporalities of planning. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 20(S1), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12097

- Adams, D., Croudace, R., & Tiesdell, S. (2012). Exploring the ‘notional property developer’ as a policy construct. Urban Studies, 49(12), 2577–2596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011431283

- Alexander, E. R. (1997). A mile or a millimeter? Measuring the ‘planning theory—practice gap’. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 24(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1068/b240003

- Allmendinger, P. (2002). Planning theory. MacMillan.

- Altshuler, A. (1965). The goals of comprehensive planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(3), 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978165

- Ambrose, P. J. (1994). Urban process and power. Routledge.

- Aragón, P., Kaltenbrunner, A., Calleja-López, A., Pereira, A., Monterde, A., Barandiaran, X. E., & Gómez, V. (2017). Deliberative platform design: The case study of the online discussions in Decidim Barcelona. In G. L. Ciampaglia, A. Mashhadi, & T. Yasseri (Eds.), Social informatics: 9th International Conference on Social Informatics Part II (pp. 277–287). Springer.

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Barras, R. (1987). Technical change and the urban development cycle. Urban Studies, 24(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988720080021

- Beauregard, R. A. (2020). Advanced introduction to planning theory. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Boholm, A., & Löfstedt, R. E. (2013). Introduction. In A. Boholm & R. E. Löfstedt (Eds.), Facility siting: Risk, power and identity in land use planning (pp. xii–xxv). Routledge.

- Breheny, M. (2001). Housing is not a disease: Reflections on PPG3 and regional planning guidance. Journal of Planning and Environmental Law (Supplement Occasional Paper), 29, 79–89.

- Briffault, R. (1995). The local government boundary problem in metropolitan areas. Stanford Law Review, 48(5), 1115. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229382

- Brindley, T., Rydin, Y., & Stoker, G. (2005). Remaking planning: The politics of urban change. Routledge.

- Brooks, M. (2017). Planning theory for practitioners. Routledge.

- Brown, P. H. (2015). How real estate developers think: Design, profits, and community. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Brugler, J., Nasiri, M., & He, R. (2020). The duration and amplitude of Australia’s housing cycles. Victoria’s Economic Bulletin, 4, 1–14. https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/Victorian%20Economic%20Bulletin%20-%20Volume%204.pdf

- Campbell, S. (2016). The planner’s triangle revisited: Sustainability and the evolution of a planning idea that can’t stand still. Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(4), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1214080

- Casey, E. S. (2017). The world on edge. Indiana University Press.

- Chakraborty, A., Kaza, N., Knaap, G. J., & Deal, B. (2011). Robust plans and contingent plans: Scenario planning for an uncertain world. Journal of the American Planning Association, 77(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2011.582394

- Chapin, F. S., Jr. (1965). Urban land use planning (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press.

- Chapin, T. S. (2012). Introduction: From growth controls, to comprehensive planning, to smart growth: Planning’s emerging fourth wave. Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2011.645273

- Charney, I. (2012). The real estate development industry. In R. Weber & R. Crane (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of urban planning (pp. 722–738) Oxford University Press.

- Clawson, M., & Hall, P. (1973). Planning and urban growth: An Anglo-American comparison. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Coiacetto, E. J. (2000). Places shape place shapers? Real estate developers’ outlooks concerning community, planning and development differ between places. Planning Practice and Research, 15(4), 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450020018790

- Cox, A. (1984). Adversary politics and land: The conflict over land and property policy in post-war Britain. Cambridge University Press.

- Cox, K. R. (1979). Location and public problems: A political geography of the contemporary world. Blackwell.

- Cox, K. R. (1995). Globalisation, competition and the politics of local economic development. Urban Studies, 32(2), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989550013059

- Cox, K. R., & Johnston, R. J. (1982). Conflict, politics and the urban scene: A conceptual framework. In K. Cox & R. J. Johnston (Eds.), Conflict, politics and the urban scene (pp. 1–19). Longman.

- Cox, K. R., & McCarthy, J. (1982). Neighborhood activism as a politics of turf: A critical analysis. In K. Cox & R. J. Johnston (Eds.), Conflict, politics and the urban scene (pp. 196–219). Longman.

- Drewett, R. (1973). The developers: Decision processes. In P. Hall, H. Gracey, R. Drewett, & R. Thomas (Eds.), The containment of urban England (Vol. 2, pp. 163–193). George Allen and Unwin.

- Eisenhart, M. (1998). On the subject of interpretive reviews. Review of Educational Research, 68(4), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068004391

- Fagin, H. (1955). Regulating the timing of urban development. Law and Contemporary Problems, 20(2), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.2307/1190331

- Fisher, E. M. (1933). Speculation in suburban lands. American Economic Review, 23, 152–162.

- Friend, J. K., & Hickling, A. (2005). Planning under pressure: The strategic choice approach. Routledge.

- Forester, J. (1989). Planning in the face of power. University of California Press.

- Frug, G. E. (2001). City making. Princeton University Press.

- Grant, J. L. (2017). Growth management theory: From the garden city to smart growth. In V. Watson, A. Madanipour, & M. Gunder (Eds.), The Routledge book of planning theory (pp. 41–52). Routledge.

- Grant, M. (1999). Planning as a learned profession. Unpublished paper to the Royal Town Panning Institute.

- Gurran, N. (2011). Australian urban land use planning: Principles, systems and practice. Sydney University Press.

- Guy, S., & Henneberry, J. (2000). Understanding urban development processes: Integrating the economic and the social in property research. Urban Studies, 37(13), 2399–2416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020005398

- Hack, G. (2018). Site planning: International practice. MIT Press.

- Haila, A. (1991). Four types of investment in land and property. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 15(3), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1991.tb00643.x

- Hall, P. (1980). Great planning disasters. Methuen.

- Han, A. T., Laurian, L., & Dewald, J. (2021). Plans versus political priorities: Lessons from municipal election candidates’ social media communications. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1831401

- Harvey, D. (1985). The urbanisation of capital. Blackwell.

- Healey, P. (1991). Models of the development process: A review. Journal of Property Research, 8(3), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599919108724039

- Healey, P. (1992). An institutional model of the development process. Journal of Property Research, 9(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599919208724049

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning. MacMillan.

- Healey, P., McNamara, P., Elson, M., & Doak, A. (1988). Land use planning and the mediation of urban change: The British planning system in practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoch, C. (2019). Pragmatic spatial planning: Practical theory for professionals. Routledge.

- Holway, J., Elliott, D. L., & Trentadue, A. (2014). Arrested developments: Combating zombie subdivisions and other excess entitlements. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Hopkins, L. D. (2001). Urban development: The logic of making plans. Island Press.

- Hopkins, L. D. (2014). It is about time: Dynamics failure, using plans and using coalitions. Town Planning Review, 85(3), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2014.19

- Hopkins, L. D., & Zapata, M. A. (2007). Engaging the future: Tools for effective planning practices. In L. D. Hopkins & M. A. Zapata (Eds.), Engaging the future: Forecasts, scenarios, plans, and projects (pp. 1–17). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Kim, Y. (2019). Limits of fiscal federalism: How narratives of local government inefficiency facilitate scalar dumping in New York State. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(3), 636–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18796511

- Kolankiewicz, V., Nichols, D., & Taylor, L. (2022). Ghostly visions and cartographic tombstones. In N. A. Phelps, J. Bush, & A. Hurlimann (Eds.), Planning in an uncanny world: Australian urban planning in international context (pp. 149–168). Routledge.

- Knox, P. (2009). Metroburbia USA. Rutgers University Press.

- Kone, D. L. (2000). Land development (9th ed.). Home Builder Press.

- Lake, R. W. (1987). Introduction. In R. W. Lake (Ed.), Resolving locational conflict (pp. xv–xxviii). Center for Urban Policy Research.

- Logan, J. R., & Molotch, H. (1987). Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. University of California Press.

- Lyle, J., & Hill, D. (2003). Watch this space: An investigation of strategic gap policies in England. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350307980

- Majone, G. (1989). Evidence, argument, and persuasion in the policy process. Yale University Press.

- Marcuse, P. (1976). Professional ethics and beyond: Values in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 42(3), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944367608977729

- Molotch, H. (1976). The city as a growth machine: Toward a political economy of place. American Journal of Sociology, 82(2), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1086/226311

- Murdoch, J., & Abram, S. (2017). Rationalities of planning: Development versus environment in planning for housing. Taylor & Francis.

- Neuman, M. (2007). How we use planning: Planning cultures and images of futures. In L. D. Hopkins & M. A. Zapata (Eds.), Engaging the future: Forecasts, scenarios, plans, and projects (pp. 155–174). Lincoln Land Institute.

- O’Mara, M. (2015). Cities of knowledge. Princeton University Press.

- Orfield, M. (2000). American metropolitics: The new suburban reality. Brookings Institution Press.

- Oxford Languages Online Dictionary. (2024). Oxford University Press. https://languages.oup.com/

- Pasotti, E. (2010). Political branding in cities: The decline of machine politics in Bogotá, Naples, and Chicago. Cambridge University Press.

- Peiser, R. (1990). Who plans America? Planners or developers? Journal of the American Planning Association, 56(4), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369008975453

- Phelps, N. A. (2012a). An anatomy of sprawl: Planning and politics in Britain. Routledge.

- Phelps, N. A. (2012b). The growth machine stops? Urban politics and the making and remaking of an edge city. Urban Affairs Review, 48(5), 670–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087412440275

- Phelps, N. A. (2015). Sequel to suburbia: Glimpses of America’s post-suburban future. MIT Press.

- Phelps, N. A. (2021). The urban planning imagination: A critical international introduction. Polity.

- Phelps, N. A., Buxton, M., & Nichols, D. (2023). Melbourne’s suburban landscapes: Administering population and employment growth. Built Environment, 49(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.49.1.132

- Phelps, N. A., & Miao, J. T. (2023). ‘It’s the hope I can’t stand’: Planning, valuation and new community building. Journal of Property Research, 40(3), 252–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2023.2183887

- Phelps, N. A., & Nichols, D. (2022). Can growth be planned? The case of Melbourne’s urban periphery. Journal of Planning Education and Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221121248

- Phelps, N. A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2008). If geography is anything, maybe it’s planning’s alter ego? Reflections on policy relevance in two disciplines concerned with place and space. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 33(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1231629

- Phelps, N. A., & Valler, D. (2018). Urban development and the politics of dissonance. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(1), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1231629

- Phelps, N. A., & Wood, A. M. (2011). The new post-suburban politics? Urban Studies, 48(12), 2591–2610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011411944

- Pickvance, C. (1982). Physical planning and market forces in urban development. In C. Paris (Ed.), Critical readings in planning theory (pp. 69–82). Pergamon Press.

- Pinch, S. (1985). Cities and services: The geography of collective consumption. Routledge Kegan Paul.

- Roulac, S. (1996). Real estate market cycles, transformation forces and structural change. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1996.12089519

- Savini, F., Ferreira, A., & von Schönfeld, K. C. (Eds.). (2022). Post-growth planning: Cities beyond the market economy. Routledge.

- Scott, A. J., & Roweis, S. T. (1977). Urban planning in theory and practice: A reappraisal. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 9(10), 1097–1119. https://doi.org/10.1068/a091097

- Sewell, W. H., Jr. (2008). The temporalities of capitalism. Socio-Economic Review, 6(3), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwn007

- Stone, C. N. (1989). Regime politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988. University Press of Kansas.

- Strandberg, U. (2000). Contested territory: The politics of siting controversy [Paper presentation]. Proceedings from the ESREL 2000 and SRA – Europe Annual Conference on Foresight and Precaution, Edinburgh, UK, 14–17 May 2000.

- Taylor, N. (1980). Planning theory and the philosophy of planning. Urban Studies, 17(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988020080321

- Teaford, J. C. (1997). Post-suburbia: Government and politics in the edge cities. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Teitz, M. B. (1968). Toward a theory of urban public facility location. Papers in Regional Science, 21(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5597.1968.tb01439.x

- Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/257839

- Tomlinson, R. (Ed.). (2012). Australia’s unintended cities: The impact of housing on urban development. CSIRO Publishing.

- Valler, D. C., & Phelps, N. A. (2018). Framing the future: On local planning cultures and legacies. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1537448

- Valler, D. C., Phelps, N. A., & Radford, J. (2014). Soft space, hard bargaining: Planning for high-tech growth in ‘Science Vale UK’. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(5), 824–842. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1268r

- Valler, D. C., Phelps, N. A., & Wood, A. M. (2012). Planning for growth? The implications of localism for 'Science Vale’, Oxfordshire, UK. Town Planning Review, 83(4), 457–488. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2012.27

- Wakeman, R. (2016). Practicing utopia: An intellectual history of the new town movement. University of Chicago Press.

- Warner, K., & Molotch, H. (2000). Building rules: How local controls shape community environments and economies. Westview Press.

- Weiss, M. A. (1987). The rise of the community builders: The American real estate industry and urban land planning. Columbia University Press.

- Whitehead, P. (1990). Planning theory—The emperor’s clothes? Planning Outlook, 33(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/00320719008711861

- Yiftachel, O., & Huxley, M. (2000). Debating dominance and relevance: Notes on the 'communicative turn’ in planning theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(4), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00286