Origin

Integrated water resources management: a promising concept for basin management

The concept of integrated water resources management for a basin is the result of a long gestation.

As early as 1977, at the United Nations Water Conference in Mar del Plata (Argentina), management of freshwater resources was the subject of political discussions between the Member States of the United Nations. The Mar del Plata Action Plan, adopted at the end of the Conference, included eight recommendations and 12 resolutions, several of which laid the foundations of an integrated management and planning policy, although the term integrated water resources management was not used. The decade of water and sanitation (1981–1990) that it inaugurated aimed to achieve universal access to water and sanitation by 1990, via support from Public Development Aid allocated to the construction of drinking water production and sanitation networks and plants. However, it did not address the conditions required for the long-term operation of this equipment: good water resource management in all its aspects, and effective legal and institutional frameworks.

Integrated water resources management really came into existence in 1992. In January, the Dublin International Conference on Water and the Environment applied the concept of ‘sustainable development’ (which first appeared in 1987 in the Brundtland report) to the water sector. The Dublin Declaration sets out four ‘guiding principles’:

Fresh water is a limited, vulnerable resource, essential for life, development and the environment.

Water development and management must be based on a participatory approach involving users, planners and decision-makers at all levels.

Women play a central role in the supply, management and conservation of water.

Water has economic value in all its competing uses and must be recognized as an economic asset.

The Declaration does not directly mention the concept of a river basin, but leads there relatively directly as the ‘natural’ and coherent scale for applying principles 1 and 2.

These ‘Dublin Principles’ are reflected in the conclusions of the United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCTAD or ‘Earth Summit’, Rio de Janeiro, June 1992). They are detailed in these conclusions and accompanied by recommendations on the actions to be implemented in Chapter 18 of Agenda 21 drawn up at the Summit, entitled: ‘Protecting freshwater resources and their quality: applying integrated approaches to the development, management and use of water resources’.

In international water law, 1992 also represents an unprecedented step forward for integrated water resources management in transboundary basins, with the adoption of the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Rivers and International Lakes (Helsinki, 17 March 1992; hereinafter ‘Helsinki Water Convention’). This important trext, initially regional and limited to the Member States of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), is the first major (regional) legal instrument in this field.Footnote1

Therefore, 1992 marks the official start of basin-wide integrated water resources management. The approach seeks to provide a solution to the increasing pressures on water resources. It aims to correct the excesses and negative impacts of a policy of major structural adjustments rolled out in local areas, often without involvement from the stakeholders in those areas, by a highly centralized administration. Its ambition is to improve the balance of water resource management through a new governance framework (including transboundary) that integrates environmental, economic and social dimensions in order to make political decisions and the necessary choices in terms of infrastructure or measures. It is therefore an attempt to translate the logic of sustainable development into water management.

Early criticism of integrated water resources management as being too vague

The Dublin Principles were a significant step forward in promoting a more integrated approach to water management. However, they were also criticized very early on and considered too vague to be of any use on the ground.

First, they are not supported by a clear and concise definition of integrated water resources management. This leaves room for development of as many definitions as there are stakeholders in water management, resulting in misunderstandings and difficulties in dialogue.

Of course, the Dublin principles represent a huge ambition for water management: achieving sustainable development by integrating its three dimensions (environmental, social and economic). However, they only provide very general guidelines for attaining this. They do not specify the structures to be put in place, the measures to be implemented, or the tools and the methods to be used. Their very nature is therefore criticized: they are perceived as an essentially theoretical and conceptual framework (cyclical criticism, also taken up in the 2000s). They are considered too abstract and without real scope, due to the lack of corrective measures to reform existing water management models at global level and to change the practices of resource users at local level.

The insistence of the Dublin principles on recognizing water ‘as an economic asset’ is also criticized. This would seem to prioritize the economic side of sustainable development over the two other dimensions, social and environmental. This criticism was later intensified when the right to water (and sanitation) was recognized as a fundamental human right, and water was recognized as a common good rather than a commodity.

Finally, the Dublin principles are criticized because they neglect local territories, in much the same way as the highly centralized technicist system that they question. Their recommendations remain generic. Although they state that ‘the participatory approach [must] involve users, planners and decision-makers at all levels’, the territorial level at which the action must be prioritized is not defined. This makes it even more difficult to translate these principles into actions on the ground.

Furthermore, integrated water resources management is at times criticized as a moral attitude on good governance, or even as a philosophy, an ideology, or nothing more than a concept. These criticisms have been taken into account to improve the definition and operational implementation of the integrated water resources management concept, making it an effective instrument.

The application of integrated water resources management principles at basin and sub-basin level has in fact enabled to go beyond its over-theoretical aspects and demonstrate the relevance and tremendous adaptability of the approach.

Operationalizing integrated water resources management

From theory to practice: operational implementation of integrated water resources management at river basin level

The theoretical foundations of integrated water resources management were laid in 1992. This was a significant achievement in itself, despite the weaknesses highlighted. The emergence of the concept was accompanied by scientific literature, discussions among industry professionals and a plethora of events. This intellectual activity helped to raise awareness among water management stakeholders about the need for a more reasoned and sustainable change of model.

However, in-depth work was still needed to move from theory to practice and ensure that the actions implemented on the ground benefited all uses and protected the environment.

The International Network of Basin Organizations (INBO) was created for this purpose in 1994 following the Earth Summit. Its mission is to promote an operational approach to integrated water resources management and support its implementation in national and transboundary river basins, lakes and aquifers all over the world.

INBO, its members and partners (in particular the UNECE in charge of the Secretariat of the Helsinki Convention, the UNESCO International Hydrological Programme, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] and the Global Water Partnership) are the main architects of this effort, working together to make integrated water resources management operational.

The Global Water Partnership therefore proposed a definition of integrated water resources management, now commonly adopted: ‘integrated water resource management is a process that promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources in order to maximize economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems’.Footnote2 It should be noted that this definition does not refer to the integrated water resources management territory of application and does not mention the river basin.

Therefore, the INBO completes this definition by associating six key actions with it, designed to make integrated water resources management a success. They respond to the question about the most relevant scale of territory for action (the scale of the hydrographic basins, beyond the administrative borders), the structures to be put in place, the measures to be taken, and the tools and methods to be used.

All of them are part of an intersectoral approach aiming at breaking down silos and making public policy and user behaviour more consistent (water, environment, energy, agriculture, finance, industry, tourism, fisheries, etc.).

Manage surface water and groundwater conjunctively at river basin level to ensure upstream–downstream solidarity and base decision-making on the hydrological and territorial reality of this natural unit, as in the cases of the Spanish river basin confederations or French water agencies, rather than on the constraints imposed by administrative boundaries (intra- or inter-state). This may involve implementing policy reforms and dedicated legal and institutional frameworks, including the creation or strengthening of basin organizations (and other similar structures, including national administrations in charge of water management at basin level). See the ‘Governance’ and ‘Strategy and actions’ sections in this issue.

Document the status of water resources (diagnosis) and inform the decision-making process through water monitoring networks (for quality and quantity), soil and associated resources as well as by creating or strengthening water information systems to reinforce data sharing and knowledge. See the ‘Water information systems’ section.

Develop multi-annual management plans setting long-term objectives (reducing water consumption, combating pollution, protecting and restoring aquatic ecosystems, developing unconventional water resources, etc.). This strategic planning must take into account the available resources, the needs of the environment, demand and current and future pressures (with forward-looking analysis, including on climate changes) of all uses (domestic, agricultural, industrial, energy, etc.) with the aim of intersectoral integration. See the ‘Strategy and actions’ section.

Invest in multi-annual programmes of measures to ensure achievement of the objectives set out in the management plans through activities on the ground, development of infrastructures dedicated to flood and drought protection, pollution prevention and environmental protection and the provision of services (hydroelectricity, irrigation, domestic and industrial water supply, river transport), the benefits of which are generally more visible to people and easier to highlight by decision-makers than the daily (but more underground) actions of basin management that make them possible. See the ‘Governance’ and ‘Strategy and actions’ sections.

Implement sustainable financing mechanisms using available public financial resources (the three OECD ‘T’: (1) General and allocated taxes, such as fees; (2) Tariffs and payments for services rendered, in the form of bills for drinking water, sanitation, irrigation, etc.) and (3) Economic incentives such as the polluter-payer/user-payer principle, which penalizes resource degradation and subsidizes virtuous water management. See the ‘Governance’ section.

Involve users and more broadly water management stakeholders (state, local authorities, civil society organization, water users) at each stage (diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation, correction). Beyond the moral value that might be intrinsically associated with it, participatory management is a factor in efficiency: it facilitates the emergence of shared diagnoses, adherence to collectively agreed objectives, ownership of the measures to be implemented, accountability of all involved in terms of results, as well as reconciliation or arbitration of divergent interests in the different uses of water. It may take the form of a deliberative body (traditionally a basin committee or council) associated with the executive body responsible for planning integrated water resources management (traditionally a basin organization). See the ‘Governance’ and ‘Strategy and actions’ sections.

All these actions are integrated into a cyclical, iterative process. In other words, the diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation and correction steps follow each other and are improved with each cycle.

This process is largely inspired by the French water management model, initiated in 1964 by establishing basin organizations (water agencies – formerly basin financial agencies) and deliberative bodies (basin committees).

The experience of recent decades has shown that this model is robust enough to be tested and adapted in a very diverse range of cultural, political, economic, social, climatic conditions according to the river basins, including transboundary ones.

This operational process, briefly described here, was covered in the ‘Handbook for Integrated Water Resources Management in Basins’ (INBO, 2009). Published by INBO and Global Water Partnership, this guide combines theory with practice. It details the tools to be implemented and presents case studies of good practices implemented in national and transboundary basins relating to all these recommended key actions ().

Box 1. INBO manuals.

Performance indicators

Many projects are designed to gradually improve governance at river basin level. They involve governments, the basin organizations themselves where they exist, users, citizens, and sometimes the assistance of bilateral or multilateral funders.

It can be interesting to characterize the developments achieved, both in terms of governance, but also in terms of concrete results ‘on the ground’.

Two groups of indicators can therefore be developed:

Governance indicators that assess how basin organizations are organized with regard to integrated water resources management objectives (political aspects, legal, institutional and organizational framework, financing mechanisms, planning methodologies, participation processes, monitoring and information systems, communication).

Indicators describing the development of the ‘situation on the ground’, which therefore assess the basin and the pressures experienced from a quantitative, qualitative and aquatic biodiversity point of view. They can also describe the solutions provided to each of the basin’s major challenges.

The range of indicators always depends on the context and must be interpreted according to the provisions specific to the basin (mandate, financing, etc.), the hydrological conditions, the stage of economic development, the capacity of the organization, etc.

All the indicators can be applied generally to the entire basin, but some of them also work at sub-basin level.

The increasing role of Integrated Water Resources Management at basin level in European regulations

The European region is a key player in the emergence of integrated water resources management at basin level, but also in the increasing role it plays on the global scale: Dublin Principles (1992), Helsinki Water Convention (1992), creation of the INBO (1994), then the Global Water Partnership (1996) with their respective headquarters in Paris and Stockholm.

First, the European Commission adopted the Water Framework Directive in 2000. This policy framework confirms the hydrographic basin as the implementation perimeter for integrated, sustainable water management. It covers the integrated water resources management’s operational process, including its participatory and iterative nature, with six-year planning cycles with the ultimate objective of achieving ‘good ecological status’. It is largely inspired by the wealth of experience of some of its Member States, pioneers in the field of integrated and participatory management at basin level, who were committed to this approach well before the conceptualization of integrated water resources management:

the French water management model, its water agencies and basin committees (created in 1964), its planning tools at basin level (the Water Development and Management Masterplans – SDAGE – appeared in 1992, the logic of which is reproduced in the Water Framework Directive’s River Basin Management Plans) and sub-basin level (SAGE) and its financing principles (‘water pays for water’, according to which the costs of drinking water and sanitation are borne by drinking water users; ‘polluter-payer’, as presented above);

the local water management offices in the Netherlands (Waterschappen) responsible for qualitative and quantitative management of the resource (Hoogheemraadschap van Rijnland is the oldest of these offices, dating from 1255);

the Spanish Hydrographic Confederations, the first of which was founded in 1926 for the Ebre river basin.

The European choice of this operational approach through the Water Framework Directive has contributed to its recognition and dissemination well beyond the 27 Member States of the European Union. For example, within the framework of the European Union Water Initiative, the tools and methodologies and purposes of the Water Framework Directive have been tested and adapted in other regions and countries (e.g., European Union Water Initiative [EECCA] for Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia; China–Europe Water Platform [CEWP]; India–Europe Water Partnership). Adapting the model and in particular its purpose has proved particularly useful in emerging and developing countries. For example, the European Union Water Initiative has investigated how basin-wide integrated water resources management could help reduce poverty in Africa and combat water shortages in the Mediterranean.

Integrated water resources management at transboundary basin level: international law, the United Nations and funders

International law has made a major contribution to promoting operational integrated water resources management at basin level by seeking to establish a legal framework for cooperation on transboundary watercourses.

The Helsinki Water Convention has played a particularly important role in this regard. Its entry into force for States that are Parties to the pan-European region of the UNECE (1996) then its global opening to all United Nations Member States (2013) significantly reinforced the customary principles of international law specific to integrated water resources management in transboundary basins:

the due diligence obligation to prevent, control and reduce transboundary impacts (‘no harm’ principle);

the principle of equitable and reasonable use;

the cooperation principle.

The balance between the first principle (favourable to downstream states) and the second principle (favourable to upstream states), together with the third principle, mean that making the basin the area for cooperation and upstream–downstream solidarity is an obligation.

Although not the first global legal framework in chronological terms (the first global convention being the Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, adopted in 1997 in New York and in force in 2014), the Helsinki Water Convention, since its inception, has gradually established itself as the main international legal instrument for cooperation on transboundary watercourses. It has a secretariat provided by the UNECE, which actively works to implement it, contributing to the development of agreements in transboundary basins, the creation of transboundary basin organizations and the strengthening of cooperation in key areas (planning, data sharing, dispute resolution).

In Southern Africa, another regional legal instrument has the same advantage and impetus: the Protocol on shared watercourses (adopted in 1995, the 2000 revision entering into force in 2003). Its secretariat is provided by the Southern African Development Community. It provides support to implement the Protocol and strengthen Integrated Water Resources Management capacities for Member States and transboundary basin organizations in the region (Limbopo Watercourse Commission, Okavango River Basin Water Commission, Orange-Senqu River Commission and Zambezi Watercourse Commission).

Some United Nations agencies (in particular the UNESCO International Hydrological Program, the World Meteorological Organization, the United Nations Development Program and the Environment Program) and international financial institutions have also strongly supported the implementation of integrated water resources management at basin level.

For instance, the World Bank has significantly supported reforms of the legal and institutional frameworks so that this model can be applied. In addition, the model of integrated water resources management at basin level was one of the factors that, in 2003, helped to relaunch the financial support provided by the World Bank to dam projects, which had been suspended since 1993 in response to criticism of their social and environmental impacts following publication of the Report by the World Commission on Dams.Footnote3 The Bank assesses the quality and sustainability of the large dam projects it instructs, in order to approve or refuse their financing.

Several multilateral funders have committed themselves to supporting Integrated Water Resources Management through specific programs, such as: the Inter-American Development Bank, the Global Environment Fund (especially its project IW:Learn on internationalwatersFootnote4), the Asian Development Bank and its ‘integrated water resources management roadmap’ for 25 river basins in Asia over the period 2006–2010, or the African Development Bank and the African Water Facility. Bilateral cooperation and development agencies (France, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada …) have also demonstrated that this area of intervention is one of their priorities. For example, the Canadian Agency for International DevelopmentFootnote5 supported the creation (in 1999) and strengthening of the Nile Basin Initiative, and from 2002 to 2010 the shared vision of the Niger Basin, alongside the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the European Union, the AFD and the GIZ (German Society for International Cooperation).

The support from these funders was mainly (but not exclusively) directed towards transboundary basins. To a lesser extent, other means of ‘decentralized cooperation’Footnote6 have been gradually utilized to strengthen the integrated water resources management capacities of national basin organizations. For example, for 15 years, the French Water Agencies have been engaged in institutional cooperation projects on integrated water resources management with basin organizations in Africa, Latin America, Asia, Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Conclusions on the increasing role of integrated water resources management

Integrated water resources management focus at basin level

In the absence of a dedicated target in the Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015), the increasing role of integrated water resources management at basin level has lacked global political impact for a long time. However, in 2015, the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals marked a significant turning point, with one target and two indicators dedicated to integrated water resources management.

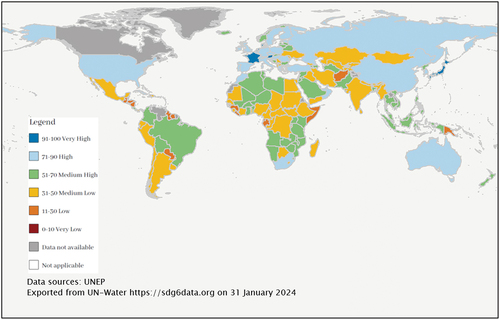

Sustainable Development Goals target 6.5 therefore aims, by 2030, to ensure integrated management of water resources at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation where appropriate. There are two indicators associated with this target, designed to monitor the progress made. The first, indicator 6.5.1, provides information on the degree of implementation of integrated water resource management, by assigning a score in percentage of target achievement (0–100) ().

It appears that the operational integrated water resources management model developed by INBO and its partners is one of the sources of inspiration for the impact assessment framework. This is structured into four key components that, to obtain the best score, must include:

Favourable environment: basin or aquifer management plans based on integrated water resources management and policies, with the laws and strategic planning that govern them.

Institutions and participation: organizations responsible for directing implementation of integrated water resources management at basin or aquifer level, with the institutional framework involving stakeholders in the implementation.

Management tools: sharing data and information at basin level.

Financing: budgets at basin level allocated to hydraulic infrastructure and those allocated to integrated water resources management elements (investments and recurring costs).

In addition to the European countries, China, Brazil and South Africa scored well. Other interesting models can be found elsewhere; for example, in West Africa with the Organization for the Development of the Senegal River Basin.

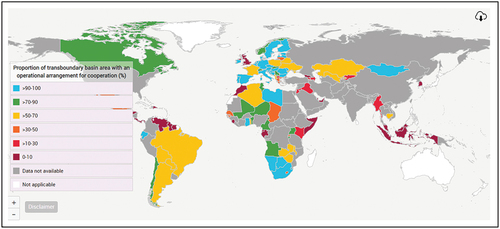

The second, indicator 6.5.2, provides information on the proportion of the surface area of the world’s transboundary basins covered by an operational arrangement for cooperation in the water sector (agreement, treaty, convention or other arrangement providing a framework for cooperation) (). Here, it is the existence or not of a cooperation framework and its operational nature that is examined, with the following as criteria:

The existence of a common organization for cooperation between the riparian States in the transboundary river basin in question.

Regular, formal communication between the riparian states (at least once a year).

The development of joint or coordinated management plans or objectives.

Regular exchange of data and information (at least once a year).

Figure 2. Global status of indicator 6.5.2 Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation (2020).

The adoption of this dedicated target alone is a major focus of integrated water resources management at basin level, as an essential means of achieving sustainable development. Governments are also becoming aware (although belatedly) that the availability of water (in sufficient quantity and quality) for ecosystems and for all uses (drinking water, agriculture, energy, etc.) ultimately depends on the proper management of lake, river and aquifer basins. Finally, there is a recognition of the need to make basin management a major political priority.

Challenges and outlook

First, the challenge of thematic and geographic ‘blind spots’ needs to be addressed when implementing an operational approach to integrated water resources management at basin level. However, the global average of attaining the 6.5 target (54% and 58%, respectively, for integrated water resources management and transboundary cooperation) remains unsatisfactory. The 10 best-ranked countries have a score of 90% or more. European States are at the top of the ranking, with six of the top 10 scores assigned to Member States of the European Union, whose leading role in the rise of integrated water resources management has been highlighted above.

In the future, it is therefore essential to strengthen integrated water resources management at basin level, where the needs are most important, without neglecting support for countries ranked as ‘mid-table’. In the latter, the model of integrated water resources management at basin level is not fully operational: for example, basin organizations exist but lack the institutional, technical or financial autonomy to act.

A strategic challenge has also arisen due to global changes. Pressures on water are increasing and accumulating: population growth, rural exodus and increase in megacities, maldevelopment characterized by the maintenance or establishment of unsustainable consumption and production patterns, degradation of soils and aquatic ecosystems leading to loss of biodiversity, and of course climate change. The unavailability of water resources in sufficient quantity and quality is a threat in itself (water insecurity) as well as a direct threat to national food and energy security. The strategic challenge therefore consists in promoting integrated water resources management actions at basin level as the most efficient water management model to guarantee national security (water, food, energy, etc.).

The outlook is favourable. Competitive models such as water markets, which make the ‘free market’ an effective tool for water management, have shown great difficulty in managing this common asset sustainably in places where this has been attempted (California, Chile, Australia, etc.). Integrated water resources management at basin level has the advantage of an operational process that is both robust and adaptable, ensuring efficiency in a constantly changing environment. It has also been enriched by the contribution of very similar concepts such as Nexus and the ‘from Source-to-Sea’ approach. This approach is paying off: following the 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28, Egypt), the basin was recognized as a particularly relevant scale in the section of the Sharm El-Sheik Implementation Plan dedicated to climate change adaptation.

Ultimately, the most important challenge is still to maintain and strengthen political and financial support for integrated water resources management at basin level. The achievement of integrated water resources management at basin level through the adoption of a dedicated target must translate more clearly into an increase in the financial resources used to reinforce it.

International donors will have to make a greater contribution. Recent efforts can be noted, such as the commitments to strengthen transboundary basin organizations made recently by the World Bank (Global Facility for Transboundary Waters Cooperation), the European Commission (TEI for Africa and for Central Asia) or the African Development Bank (with the DYNOBA Project in Africa). But countries must also increase use of their own endogenous financial resources (the three ‘T’s detailed above). In particular, developing countries can focus on strengthening their tax systems by gradually integrating informal sectors of their economy to ensure the viability of public financing mechanisms. This goes far beyond water policy alone, but guarantees the sovereignty and sustainability of their development policy.

The advent of an unprecedented high-level political segment dedicated to basins within the political process of the 9th World Water Forum (Dakar, March 2022) and its renewal for a second time on the agenda of the 10th World Water Forum (Bali, May 2024) are encouraging political prospects. And these are not the only ones. The United Nations Water Conference (March 2023, New York) was also a key moment for integrated water resources management per basin (promotion of the Dakar Action Plan for Basins), together with the Global Water Summit in December 2022 (launch of the Coalition for Cooperation in the transboundary water sector).

There is definitely a political will to accelerate the achievement of sustainable development (beyond the Sustainable Development Goals), by and for the basins.

Notes

1. As stated below, this regional legal instrument, opened for signature by the United Nations/UNECE Member States in 1992, came into force in 1996. It became a global legal framework (i.e., open to all United Nations Member States) for cooperation on transboundary water resources in 2013.

2. Source: Edition No. 4 of the ‘working documents’ of the Technical Advisory Committee of the Global Water Partnership – Global Water Partnership (2000).

3. This includes the importance of hydroelectric dams to produce low-carbon energy with a view to reducing gas emissions and mitigating climate change, and improving environmental impact assessment methodologies.

4. IW:LEARN is the acronym for the International Waters Learning Exchange and Resource Network.

5. Now known as ‘Global Affairs Canada’.

6. Decentralized cooperation refers to relationships, twinning, partnerships, assistance and exchanges of experience between the local communities of a country and the communities, whether or not equivalent, of other countries. For example, in France, since 2005, the Oudin-Santini Law has enabled water authorities, trade unions and agencies to spend up to 1% of their water and sanitation budget to finance international cooperation actions with local authorities in other countries. Other comparable schemes have been implemented in Switzerland (Solidarit’eau), the Netherlands (VitensEvides International) and Italy (local funds such as ‘L’Aqua è di tutti’ in Tuscany, ‘Acqua bene comune’ in Venice and Treviso and ‘Soldarietà a Torino’ in Turin).