ABSTRACT

China has a rich Central Asia studies literature and in recent years, it has seen an expansion in the number of research institutions with a regional focus. We apply a Structural Topic Model, a quantitative method that estimates thematic prevalence through machine learning, to analyse publications on Central Asia in Chinese academic and specialist journals to show how the field has evolved over time. Aside from the methodological contribution we offer an original dataset of 10,563 publications scraped from China’s CNKI database. We test our strategy on two assumptions in Western literature on Chinese academics’ understanding of Central Asia: (1) China’s research institutes are primarily concerned with economics and (2) China’s thinking on strategic regions is lacking in local context, unique cultural concepts and insights. We argue that while China's scholarship on the region is often Sinocentric, some research shows diversity and nuance, with more analytical depth that has been traditionally understood.

Introduction

Central Asia has long served as a testing ground for China’s international concepts and political communication strategies. In the early 2000s, China pioneered security concepts such as the ‘Three Evil Forces’ (terrorism, separatism, extremism) in Tashkent through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a multilateral entity set up by China, Russia and the governments of the Central Asian republics. On September 7, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping, on a visit to Kazakhstan, announced the launch of the Silk Road Economic Belt, the land component of what would become the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Central Asia then, is often something of a ‘laboratory’ where China tests its foreign policy positions before implementing them in other parts of the world (Cooley and Nexon Citation2020).

In Western academia there has been growing interest in recent years in the role China plays in Central Asia’s development. For some, the region is a strategic lynchpin in Beijing’s grand strategy to construct Sino-centric trade networks connecting Europe and Asia and undermine U.S. hegemony (Frankopan Citation2019; Hillman Citation2020; Markey Citation2021). This body of work tends to be focused on economic relations, with scholars noting that since the mid-1990s, China’s trade with Central Asia has jumped from under $1 billion to over $45.8 billion in 2021.Footnote1 Other studies have looked at the region as a source of energy security for China and at the role debt plays in the accumulation of political leverage (Dadabaev Citation2020; Karrar Citation2016; Laruelle and Peyrouse Citation2012; Wang Citation2015). Scholars work on the analytical assumption that Beijing is an economic rather than security actor in the region, resulting in the common perception of a division of labour in the region with Russia as the ‘sheriff’ and China in the role of the ‘bank’ (Larson Citation2020). Yet, other studies have focused on security and explored China’s growing arms sales and military exercises in Central Asia, revealing the degree to which internal dynamics inside China’s bordering Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) are driving its security interests in the surrounding region (Jardine and Lemon Citation2020a; Jardine and Lemon Citation2021; Kerr and Swinton Citation2008). These works rest on another common assumption, namely that China’s Central Asia policy is inherently Sinocentric and connected with its own internal dynamics mostly directed to regime survival or protection of the primacy of the Chinese Communist Party.Footnote2

In the broader context of understanding knowledge production in Chinese International Relations, Central Asia emerges as a significant focal point for China's international concepts and political communication strategies (Kavalski Citation2010; Seiwert Citation2023). While Mandarin language publications have extensively covered China's role in the region, little attention has been given to how Chinese scholars and experts perceive and contribute to the understanding of the region. This article aims to bridge this gap by delving into the evolution of China's thinking on Central Asia amongst its community of regional experts in academia and beyond. Starting from the two assumptions above from international (Western) literature, (1) that China views Central Asia through an economic lens and (2) that China’s Central Asia-focused academic and policy communities are Sinocentric, this research explores the Chinese vision of Central Asia through a thematic analysis of Chinese publications on the region.

Employing a Structural Topic Model (STM), the article quantitatively analyses Chinese-language specialist journals to unveil key themes and the evolving research agenda in China's area studies literature on Central Asia. This comprehensive approach contributes a longitudinal understanding to the literature on China's knowledge production in the context of Central Asian studies, which in turn contributes to the literature on Chinese IR and its imagination of regions. We argue that China’s scholarship is often Sinocentric, particularly in the humanities, and that social research is often focused on economic aspects. Yet, some threads of research are richer than normally assumed and informed by local perspectives, and the mix of research includes a strong security focus. We also introduce a new dataset on studies on Central Asia in the Chinese language that we hope can be explored through further qualitative and quantitative research.

The article begins by reviewing common narratives in Western literature on China’s role in Central Asia, before setting out to assess prior studies on China’s knowledge-production system in Central Asian studies. The paper then uses a Structural Topic Model, a method for quantitative document analysis based on machine learning, to analyse research on Central Asia in Chinese-language academic journals to show key themes in China’s area studies literature and how its research agenda in Eurasia has evolved over time.

A review of studies on China’s knowledge-production in Central Asian studies

Many studies, mostly in the tradition of constructivist International Relations, have looked at China’s own imagination of Central Asia to provide a nuanced understanding of the effect of local images of the region in China’s decision making. However, while much work has been done to understand China’s policy-making and the complex constellation of actors involved in regional engagement (Dadabaev Citation2020; Kavalski Citation2010; Sciorati Citation2023; Seiwert Citation2023), less has been done to understand how Chinese academics and researchers think about the region. By exploring both the knowledge production process and its intellectual outputs, we hope to assess China’s developing regional studies over time to gauge thematic prevalence, research priorities, and key researchers advancing research agendas in the study of Central Asia.

Central Asian studies has been growing in Chinese academia. Xiao Bin’s ‘Central Asian Studies in China’ provides valuable insight into the growth and trajectory of regional studies programmes in the PRC using a quantitative assessment of 5148 published papers in China’s CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) search engine about the region from 1992 to 2018 (Xiao Citation2019).Footnote3 According to Xiao, most of the early scholars who studied the region were previously involved in Soviet/communist studies and relied largely on Russian language sources. Central Asia had been treated as a subfield within Soviet studies, and thus, Chinese academics lacked an academic understanding of the region (Xiao Citation2019). These findings correlate with the trajectory of Western scholarship on the region at the time (Tutumlu Citation2021). Xiao notes that most studies rely on traditional methods and use macro-theories rather than cutting-edge micro-level analyses of economic and political issues. Xiao concludes that China’s studies on the region tend to be policy-oriented. In addition, Xiao notes that there is a lack of originality and though there are research teams conducting studies on the region, very few of the researchers have Central Asian expertise, and direct funding for projects on the region is scarce (Xiao Citation2019). Differing from this approach, we do not limit our sampling to the most cited articles. Thanks to the use of machine learning techniques such as the Structural Topic Model, we are able to process big data and assess the evolution of thematic prevalence over time.

He and Liu (Citation2020) instead use qualitative methods to analyse trends in Central Asian studies among Western academics and reflect comparatively with the state of the field in China. This research is based on a project led by He and launched by China's National Social Science Fund in 2015 to translate 10 prominent books by Western scholars of Central Asia into Mandarin (Appendix in the online supplemental data, Table O). They argue that Western studies largely explore ethnic relations and political reforms, concluding that Western scholarship takes better stock of the region’s unique historical and political trajectory than Chinese studies, which tend to be more macro and geopolitical (He and Liu Citation2020). Similarly, Giulia Sciorati conducted a qualitative study of 40 academic papers written in Chinese exploring the normative constitution of Central Asia by Chinese scholars. She focuses on two concepts: ‘self-othering’, the idea that China and Central Asia are at different and hierarchical stages of their development, and ‘neighbouring’, where Chinese scholars construct Central Asia as culturally, geographically and politically connected to China (Sciorati Citation2023). Another central qualitative endeavour is Nadine Godehardt’s book ‘The Chinese constitution of Central Asia’, where the author challenges Eurocentric views of regionalism in Central Asia and explores Chinese insider-outsider perspective through the notion of an expanded Chinese understanding of the region that includes not only neighbouring Xinjiang, but also Afghanistan (Godehardt Citation2014).

Our quantitative approach focuses instead on understanding shifts in research agendas over time. In qualitative analyses, availability and selection bias influence the outcome of research. A qualitative researcher will hardly be able to read the entirety of Chinese-language literature on Central Asia and the selection necessarily impacts findings. At the same time, qualitative studies tend to follow a strongly deductive direction arising from the contextual temporality of the author’s analysis. Godehardt (Citation2014) for example focuses on Chinese interpretation of the 2010 Kyrgyz crisis, something perceived as relevant at the time. This choice tells us about how researchers’ perceptions of the relevance of specific events influence the content of their findings.

We improve the selection bias by looking inductively at themes in Central Asian studies in China and their evolution over time, which allows us to partially detach our positioned perception of what is relevant from the analysis (see methods below). Then we test our findings against some deductive notions coming from Western academic research on China in Central Asia. We look at how Chinese experts look at economic and security aspects of cooperation with the region to understand whether they look at China as a political/security or an economic actor in the region. We also expand the disciplinary focus by investigating whether research in the humanities is Sinocentric and follows political trends. Finally, we look at the prevalence of hot topics and Chinese foreign policy rhetoric in our corpus to understand how much political discourse influences research. We approach these issues in order to advance our central methodological contribution to the study of Chinese research communities: a strategy and a dataset to inductively explore research outputs longitudinally, to then deep dive qualitatively on specific elements of the academic corpus.

Methods

This study uses a Structural Topic Model (STM), a machine-learning method that allows researchers to analyse large amounts of text data to discover topics (themes) and their relationship with metadata (time, source, author, language, etc.) (Roberts et al. Citation2014). The STM has been used for a variety of purposes in the academic literature, from the analysis of Human Rights Reports, political Tweets and foreign policy analysis (Bagozzi and Berliner Citation2016; Combei and Giannetti Citation2020; Maracchione Citation2023; Maracchione, Sciorati, and Combei Citation2024). The main measures it estimates are topic prevalence (the probability of a topic/theme to be found in the corpus of documents and in individual documents) and topic content (the probability of words belonging to the topic) and its most relevant innovation is to allow the estimation of the effect of covariates on both measures (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Citation2019). Given that our study focuses on the thematic evolution of Chinese academic output on Central Asia, the STM offers an important tool to estimate thematic evolution over time. For this purpose, we used the abstracts of the publications as texts in our corpus.Footnote4 At the same time, being mostly unsupervised, the STM partially removes biases arising from manual coding (Barusch, Gringeri, and George Citation2011).

Data selection and collection

We began our data analysis by setting geographic and linguistic parameters to define the boundaries of our corpus of documents. First, we defined what we mean by ‘Chinese scholarship’. Since the aim of this study is to identify shifting patterns of research interest in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the data samples are limited to publications originating within it. We do so by using data from the CNKI, the PRC’s largest research database (Yang Citation2023).

Next, we defined the geographic focus and disciplinary boundaries of Chinese academic papers. We defined Central Asia as the region that includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, but we did not exclude works that discuss other countries and regions that are often included within Central Asian studies such as Xinjiang, Afghanistan or Iran. In terms of disciplinary boundaries, we included research in the social sciences and humanities. The timeframe is limited to research published from 1992, when the Central Asian republics became independent, through to 2022.

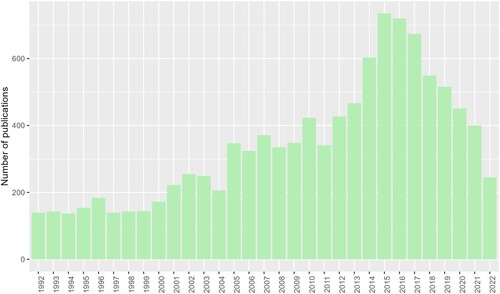

The publications were manually scraped from the CNKI. For our search, we used the keywords: ‘Central Asia’, matched with keywords for each of the five Central Asian countries. We then paired the output with the following variables: author, title, type of publication, journal/publisher, year, abstract, source and keywords. The data was scraped in Mandarin and later automatically translated into English, which is considered reliable for quantitative analyses (Lucas et al. Citation2015), with similar issues arising from automated or manual translation (De Vries, Schoonvelde, and Schumacher Citation2018). For example, a recent paper on the translation of the Chinese language by professional translators has shown that some nuance is lost in the process due to misuse of the English language, or misinterpretation of the original Chinese, while automated translation tools seem to provide translations that take the tone and the linguistic and thematic context into better account (Mokry Citation2022). The present version of the database contains 10,563 publications. shows the breakdown of publications per year, with a substantive increase in research from 2005 on, with a peak between 2013 and 2019, which seems to have slowed down more recently. The peak might be connected to a publication surge in the context of the launch of the BRI, which lost steam after a few years.

China’s Central Asian knowledge-production ecosystem

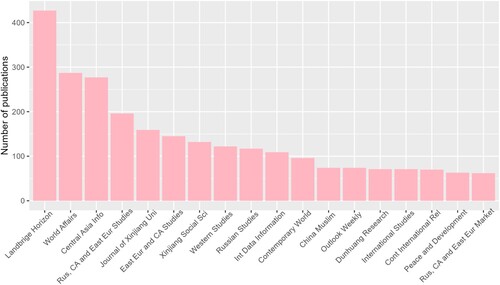

The main research hubs for Central Asian studies are traditionally in Beijing, Shanghai, Lanzhou, Xi’an and Urumqi, all of which host major institutes that teach and research the region. There are more than 20 Chinese research institutions focused on Central Asia. The largest think-tanks studying the region are in Xinjiang: there are at least five distinct institutes studying different areas of cooperation between Central Asia and Xinjiang at the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, located in Urumqi. provides a list of the most prolific publications on Central Asian studies. Three of the top five outlets for Central Asia-related publications are published in the Xinjiang region, including 大陆桥视野 (Landbridge Horizon, 427 articles), 中亚信息 (Central Asia Info, 287 articles) and 新疆师范大学学报哲学社会科学版 (Journal of Xinjiang Normal University, 159 articles).Footnote5

Figure 2. Highest number of publications on Central Asia in Chinese journals (1992–2022).

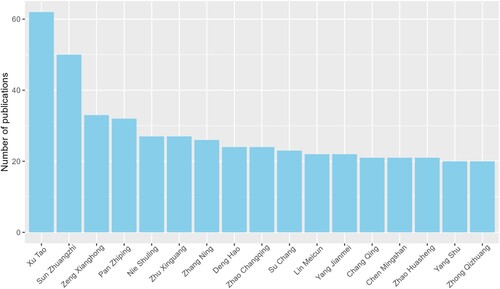

However, the statistics on the most prolific authors show a different trend that seems to move research away from Xinjiang. Of the top 10 most active researchers of Central Asia, only Pan Zhiping 潘志平, Tianshan scholar at Xinjiang University and Nie Shuling 聂书岭, editor of China Info are based in the Western region. Zhu Xinguang 朱新光 instead was trained in Xinjiang and then worked at the Shanghai Normal University. Six are based at institutional research centres in Beijing connected to the Chinese State Council including the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Sun Zhuangzhi 孙壮志, Zhang Ning 张宁, Zhao Changqing 赵常庆 and Su Chang 苏畅), the China Institute for International Studies (Deng Hao 邓浩) and the Development Research Centre of the State Council (Xu Tao 许涛, the most prolific scholar in our dataset with 62 publications as first author). shows a list of the authors that published more than 20 of the articles in our dataset.

Main trends in China’s scholarship on Central Asia: quantitative analysis

After preprocessing our corpus, we proceeded to estimate our Structural Topic Model (STM). We estimated 60 topics quantitatively (for a list see Table B in the appendix) that we subsequently grouped into 10 thematic clusters. Our classification includes clusters in . Some topics such as topic 8 on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) or topic 13 on the Colour Revolutions, are included in more than one cluster since their significance spans across themes. Table A in the Appendix provides an overview of our topics matched with the unsupervised quantitative estimation of common words and qualitative labels and descriptions based on an analysis of the most relevant documents per topic. We notice that most of the topics are in the field of social science (clusters 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9), while only two clusters are in the humanities (clusters 3 and 10). Two additional clusters, cluster 1 on diplomacy and cluster 7 on the academic world, group all the contextual topics, whose top words are not connected to specific themes, but often occur together due to the type of textual typology. We excluded these clusters from our analysis due to their lack of thematic relevance.

Table 1. Qualitative clusters resulting from the Structural Topic Model.

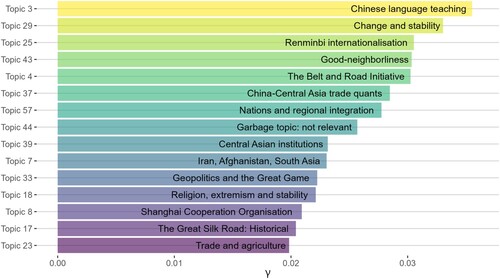

What we can infer from the data is that China’s scholarly engagement with Central Asia seems to be more generous and variegated than depicted in the literature, as can be seen in which visualizes the top 15 most prevalent topics in our corpus. While governmental priorities are very prevalent (topics 43, 4 and 17) and the top five topics are all China-related, the presence of topics 39 and 57 shows an attention to Central Asian internal developments that was not recognized by international scholars. Furthermore, the characterization of China’s scholars as primarily focused on economic development in Central Asia is put into question by the overwhelming focus on security issues – which tracks with the recent security turn in Western scholarship on China’s strategic interests in the region (Cooley Citation2021; Jardine and Lemon Citation2020a).

Figure 4. Top 15 topics for topic prevalence in the corpus.

China’s research on Central Asia in the humanities and sociological studies: state-led cultural diplomacy?

China’s cooperation with Central Asia in historical, archaeological and cultural studies is a key theme in recent international relations literature (Dadabaev Citation2018; Dadparvar and Azizi Citation2019; Sciorati Citation2022). In his book on China’s attempt to revive the concept of the Silk Road, Tim Winter notes China’s ‘geocultural power’, which he depicts as both soft and hard power (Winter Citation2019). Sciorati criticizes this duality and focuses on heritage diplomacy as a form of soft power by describing China’s historicization of transnational World Heritage Sites. The analysis of cultural studies in Chinese academic and research communities provides new depth to these studies by discussing the prevalence of cultural topics over time.

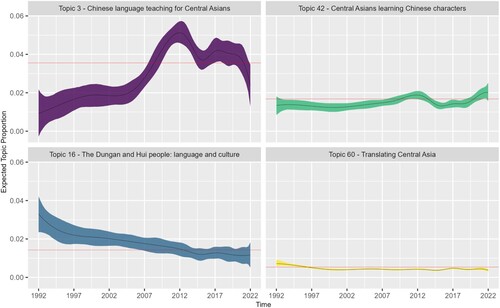

An analysis of our linguistic cluster supports the literature and its temporal design. Topic 3 on Chinese language teaching for Central Asians contains abstracts related to skills and methods to teach Chinese to local students and it is the most prevalent topic in our corpus. An example is the paper 中亚留学生提高汉语写作技能的学习策略(Learning Strategies for Central Asian Students to Improve Chinese Writing Skills) written by Wang and Zhang, which ‘mainly discusses learning strategies used by Central Asian students in writing’ (Citation2013). Another prevalent topic, number 42, focuses more specifically on Chinese characters and the difficulties that Central Asians face in learning them. The two topics also have a clear peak around 2011–14, which tracks with discussions on China’s people-to-people efforts related to the Belt and Road Initiative, as confirmed below by our other cultural clusters. Yet, the peak seems to come earlier than 2013, the year in which the BRI is traditionally collocated (see ). One interpretation is that the public-private partnership in China’s policy-making had begun developing an interest in the region that produced the backbone of BRI soft policies.

Figure 5. Topic prevalence of topics in cluster 3 on language studies over time (1992–2022).

Cluster 9 (anthropology, sociology and human geography) shows a general declining trend partially reverted around 2011–2012 and, more recently, after 2020. The prevalence of studies on religion (topics 18, 38 and 59) seems to be on the rise, potentially in line with the Islamization of Central Asia society (Pikulicka-Wilczewska Citation2021). Yet, it was much more prevalent in the early years of our timeframe (1990s). Finally, our cluster related to the study of the past containing historical and archaeological research contains 12 topics, some in common with the previous cluster, the majority of which are fairly prevalent overall. Again, the China-related topics are the most relevant with topic 17 on the Great Silk Road being in our top 15 (). Topics 41, 22 and 47 respectively, focus on relations between imperial China and Central Asia, the Mongol empires in Central Asia and cultural exchanges between Chinese and Central Asian peoples. All three topics were prevalent around the time of the independence of Central Asian republics and regained a similar level of relevance in recent years. This can be connected to the necessity to find common histories during the establishment of relations between China and Central Asia, and in China’s refocusing on the region in the second half of the 2010s.

An important boost in relevance occurred during the same period for archaeological studies (topics 9 and 52) that gained a lot of attention after 2017–18. Chinese media outlet Global Times reported in 2017 that China was becoming a leading actor in international archaeological projects, mentioning Chinese participation in archaeological excavations in Africa, South Asia and Central Asia. In Central Asia, Uzbekistan was one of the first countries to start archaeological cooperation with China. The Mingtepa site opened in 2012 is the most important fruit of such cooperation (Chen Citation2023). Zhu Yangshi, based at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) Institute of Archaeology and leader of the Mingtepa project mentioned that ‘this trend is the result of China's increasing economic strength and the country's archaeological circle's growing interest in conducting exchanges with their foreign counterparts’ (Global Times Citation2017). The analysis of our cultural clusters seems to suggest that governmental priorities have an important role in guiding research priorities in the humanities and human social sciences. Yet, the different timings of such developments as exposed in the analysis of our linguistic cluster imply a role for research communities in drawing attention to specific policy problems.

China as an economic provider: the role of economics and security in Chinese research on Central Asia

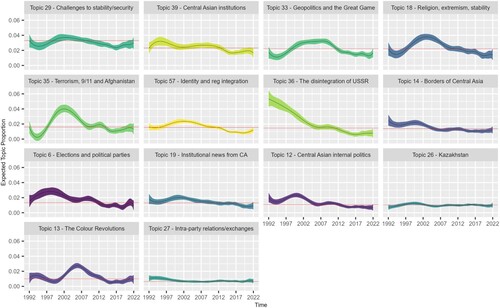

A central argument in the international literature on China and Russia in their relationship with Central Asia is their division of labour where China would be the economic provider and Russia the security guarantor. Yet, this division of labour is increasingly debated as scholars have turned to analysis of China’s complex security partnerships across the region (Jardine and Lemon Citation2020a). Our aim is to discuss whether this division of labour maps into China’s knowledge production on Central Asia and whether Chinese scholars and experts write about Central Asia with economic relations in mind. Around half of the top 15 topics in terms of prevalence are security-related and four are centred on Central Asian internal politics and potential threats to stability. Topic 29 is an important example since it discusses international events and their effect on stability in Central Asia. Examples of these events are the financial crisis, or the war in Afghanistan. A typical article connected to this topic is 当前中亚地区安全局势的特点及走势分析 (A Contemporary Analysis of the Characteristics and Trends of Security in Central Asia) written in 2015 by Jia, Zhang, and Fang (Citation2015). The topic is prevalent over time, but it shows a peak in the late 1990s to early 2000s (see ), probably connected with the role of the war in Afghanistan and the Colour Revolutions, critical points at which China connected its own security concerns in Xinjiang province with the wider Central Asian region (Petersen and Pantucci Citation2022).

Figure 6. Topic prevalence over time of topics in Cluster 8 on security and internal politics (1992–2022).

Yet, the topic seems to show a slight inflection in the second part of our time-frame. This is a trend that is common to most of the topics contained in our cluster on security and internal politics. While some event-specific topics can be expected to decrease in relevance throughout our time-frame (e.g., the topics on terrorism and 9/11), it appears that generally, security topics were more prevalent before 2013. This has an important impact in terms of the way in which international literature sees China in Central Asia. While interest towards Central Asia in China was always portrayed in Western academia in terms of economic reasoning, particularly at the onset, with a focus on energy resources, it seems that security topics were the main focus of Chinese political research on Central Asia until the last decade of our timeframe and many of these security topics trump the topic on natural resources in general prevalence.

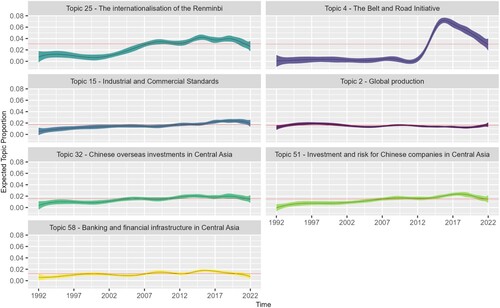

This does not mean economics is irrelevant. Our clusters 2 and 5 on macroeconomy, finance and investment, and on trade and transports contain some of the most important topics in our model. Starting from cluster 5, topics on trade and transport routes in Central Asia are unsurprisingly relevant with only two of the topics falling under the second quartile in terms of general prevalence and two topics in the top 15. These are topic 37 that contains empirical quantitative research on trade between China and Central Asia, and topic 23, a very similar topic that is less about measures and outcomes and contains more qualitative discussions on trade and markets in Central Asia with a focus on agriculture that is common to both topics. The documents contained in this second trade topic are often policy commentaries, while documents connected to topic 37 are mostly from academic sources. An example of the latter is the Citation2016 paper 中国与中亚国家农产品贸易影响因素实证研究 (An Empirical Study on Factors that Influence Agricultural Trade between China and Central Asia) authored by Li and Yang. The article is one of many that deal with agriculture, another important finding of our analysis of trade-related abstracts. Other relevant topics are connected to transport routes. Topic 24 contains documents on the Lianyungang port in Jiangsu, the starting point of the New Eurasian Land Bridge. The topic’s relevance is inflated by the publication of many reports on the theme by the journal 大陆桥视野 (Landbridge Horizon). However, many other documents in our corpus mention the port, making it worthy of some attention. For example, topic 48 contains many commentaries on transport routes for Chinese products via the port and through the many infrastructures that connect China to Central Asia. The topic on natural resources is only the 6th in terms of relevance in the trade cluster and mid-chart in terms of general prevalence. Western attention on natural resources is not mirrored by the Chinese research community. All the topics in the trade cluster show an upward trend in terms of relevance, particularly starting around 2013 in connection with the Belt and Road Initiative (for visualizations see Appendix, Table G).

Moving to cluster 2, most of the topics are in the top two quartiles, with two topics in our top 15 in terms of general prevalence. Amongst these, topic 4 on the Belt and Road Initiative is unsurprisingly prominent. Its relevance peaked in 2013 when the project was first launched (). Topic 25, however, contains a series of macroeconomic analyses that mostly centre on the aim of internationalizing the Chinese currency, the Renminbi. The discussion cuts across fields in that it does not relate to one specific policy (see BRI), but it does show an important aspect of China’s cooperation with Central Asia that is not often discussed in Western academia. The fact that topic 25 is the third most prevalent topic in our corpus is a central finding in terms of Chinese economic research on Central Asia. An example of analyses contained in the topic is the paper written by Li Qinghong in 2010 titled 我国与中亚地区贸易中人民币结算的原因分析 (Analysis of the Causes of Settlements in Renminbi in Trade Between China and Central Asia). The use of Renminbi in economic exchanges between China and Central Asia has become a very relevant topic recently after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as the Yuan is increasingly being used for interactions between Russia, China and the region due to Western sanctions to the Russian Federation (Strongney Citation2023). But in China, the prevalence of debates on Renminbi internationalization and Central Asia has been strong and stable since the late 2000s and has only grown over time (see ). Our finding calls for more research on this aspect in its development over the years, including by reviewing the literature contained in this topic qualitatively.

Figure 7. Topic prevalence over time of topics in Cluster 2 on Macroeconomics (1992–2022).

A final aspect to discuss is the increasing relevance of research related to industrial and investment cooperation between China and Central Asia. Topics 15, 32 and 51 all deal with different aspects of industrial development in the region. Topic 32 on Chinese investment in Central Asia and topic 51 on risk assessments for Chinese companies working in the region are China-focused. Topic 32 is more descriptive grouping documents commenting on business practices of Chinese investors in Central Asia. Topic 51 instead is more analytical and contains mostly research on the risks and opportunities for Chinese investment in Central Asia. For example, Hu Zhaofu (Citation2017) wrote 东道国的政治风险对对外直接投资的影响研究——以中亚国家为例 (A Study of the Impact of Political Risk in Host Countries on Overseas Direct Investment – The Case of Central Asian Countries) that discusses the risks that foreign direct investment in China involves. Topic 15 instead is more focused on technical aspects of economic cooperation such as industrial and commercial standards in Central Asia. These three topics are fairly relevant overall and they show a growing trend over time as can be seen in . This finding supports the idea that China upgrading its economic cooperation with the region, and its attention to local aspects influencing investment, has promoted the diversity and depth of its economic scholarship on Central Asia.

Chinese versus Central Asian priorities: aims and motivations to study Central Asia

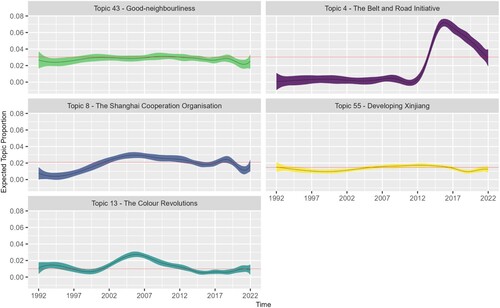

This section will focus on the relevance of topics on internal politics vis-à-vis Chinese governmental priorities and discuss topics related to clusters 4 on Chinese governmental narratives, 6 on international politics and foreign policy and 8 on security and internal issues. Cluster 4 contains common narratives in Chinese political discourse and its foreign policy concepts (Zeng Citation2020). These are topic 43 on good-neighbourliness, topic 4 on the BRI, topic 8 on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, topic 55 on Xinjiang and topic 13 on the Colour Revolutions. It is unsurprising that three of these topics are pivotal in terms of their general prevalence and rank in the top 15 of the general chart. Good-neighbourliness is the most prevalent of these narratives, which has been central for China’s relations with the region for decades. Topics 4 and 8 are also amongst the most prevalent topics, and both have been prisms through which scholars in China, as in the West, have looked at China’s involvement in Central Asia.

We explain this relevance through the prism of state funding and support. Taking the BRI as an example, in December 2013, just after the launch of the BRI, five new think tanks were created in Xinjiang: the Central Asian Research Centre, the Central Asian Centre for Agriculture, the Central Asian Biological Centre, the Central Asian Industrial Incubator Centre and the Central Asian Information Technology Centre. All are designed to facilitate the implementation of several aspects of the Silk Road Economic Belt. In February 2014, in the northwest part of China’s Shanxi Province, three new institutions were founded: the Central Asia Institute, the Institute for the Study of the Silk Road at Northwestern University, and the Central Asia Institute at Xi'an University of Foreign Languages. Hence, it is not surprising that BRI receives such coverage in our corpus. The SCO, meanwhile, was a forum where China negotiated its identity as a Central Asian actor. The SCO founding documents showcase an organization with ambitions to provide an alternative value framework on the world stage. As written in the declaration establishing the SCO, the Shanghai Spirit has six components: ‘mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for multi civilizations, [and] striving for common development’. These principles are an attempt to create a framework that mitigates against power imbalances between members in favour of a consensus-based approach to Central Asian security.

The other two topics, topic 55 on Xinjiang and 12 on the Colour Revolutions are less prevalent overall, but they represent important aspects of China’s engagement with Central Asia that are connected to China’s own security. The first topic is related to China’s border security and national unity, as well as counterinsurgency and ethnic policies (Clarke Citation2011). The second is connected to China’s regime security in relation to revolutions throughout the Eurasian space that have toppled undemocratic regimes (Chen Citation2010). Unlike geopolitical studies in the past, which viewed Central Asia as merely a source of energy to overcome its dependency on sea routes, recent surveys in the West looked at the unique security characteristics of China’s own geography and colonial identity in Xinjiang. Some Western studies argue that China follows a domestically-driven foreign policy in Central Asia, an argument made by Pantucci and Petersen in their book ‘Sinostan: China’s Inadvertent Empire’ (2022). Following this logic, instability in Xinjiang has led to heightened coordination with partners across the border. China has taken a more assertive approach to regional security, opening its first military facility in the region, in Tajikistan in 2016; increasing its share of Central Asian arms imports from 1.5% to 13%; and organizing dozens of joint exercises and officer training activities bilaterally through the SCO (Jardine and Lemon Citation2020b). Our findings confirm the relevance of Xinjiang in China’s research on Central Asia, yet they do not collocate its birth in the recent security turn of Western scholarship on China-Central Asia relations. Our topic 55 is prevalent throughout our timeframe and does not show any recent peak in prevalence, suggesting security interests in China’s research communities are much broader than Western analysts generally observe and there has been sustained interest spanning decades (see ).

Figure 8. Topic prevalence over time of topics in Cluster 4 on Chinese governmental narratives (1992–2022).

It should be noted, however, that many of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy slogans such as the ‘New Type of Great Power Relations’ or the ‘Community of Shared Future for Mankind’, as well as the more recent ‘Global Development Initiative’, ‘Global Security Initiative’ and ‘Global Civilization Initiative’ are not frequent enough in China’s discourse on Central Asia to generate separate topics. On the contrary, Chinese research has dedicated a lot of attention to Central Asian internal issues, suggesting a more nuanced understanding of regional dynamics than western scholars predicted. In cluster 8 on security and internal politics we can find for example topic 39 on Central Asian political institutions. The topic is the ninth most prevalent topic in our corpus and it contains research focussing on regional elites, political parties, democratic institutions, security apparatus and forms of government. A good example here would be Yang Jin’s Citation2014 work 论制约中亚民主政治转型进程的诸因素 (On the Factors Restricting the Process of Democratic Political Transformation in Central Asia), whose focus is entirely internal.

This interest in local politics likely stems from the struggles of many Chinese companies in implementing investment projects in the region, instead generating discontent in local communities, often resulting in protests (Oxus Society Citation2023). For example, one of the early initiatives of the BRI was the modernization of the outdated power plant in Bishkek, which commenced in 2014 financed through a 20-year loan agreement between China’s Export-Import Bank and the Kyrgyzstani government but led to scandals of high-level corruption, mass protests and growing anti-China sentiments (RFE/RL Citation2018). In February 2020, Kyrgyzstan’s government was forced to cancel a $275 million Chinese logistics project after protesters mobilized against it. The Kyrgyz-Chinese Ata-Bashi Free Economic Zone Joint Venture, set up by China’s One Lead One (HK) Trading Limited and a Kyrgyzstani partner, noted that the contract had been annulled because ‘it is not possible to work on a long-term large project in the circumstances’ – referring to widespread local backlash. In response to this, Chinese projects have begun to adapt to cater to local needs and improve at the implementation level, as discussed in the literature review. The prevalence of our topics on internal politics shows that research on Central Asian internal politics exists in China and is a focal discussion in our corpus.

Conclusion

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, China has become a substantial political and economic player in Central Asia. To facilitate its integration with the region, Chinese academia has been expanding regional studies programmes and language training to better understand the region. Our research challenges common assumptions about China’s research interests being predominantly economic in nature. By looking at overall prevalence, it became clear that the characterization of economic relations as the focus on China’s knowledge production on Central Asia is questionable and security and trade/economics have a similar thematic prevalence.

Our data matches well the evolution, expansion and diversification of economic scholarship with China upgrading its economic cooperation with the region, and the localization of Chinese investments. The interest of Chinese research communities about Central Asian internal politics, institutions and societies may be connected to the struggles of many Chinese companies to successfully implement investment projects in the region, which created discontent in local communities, often resulting in protests. In response to this, Chinese companies tried to adapt, by better understanding local needs and improving their reputation on the ground. Contrary to common beliefs, the prevalence of our topics on internal politics shows that research on Central Asian internal politics is a focal discussion in China. So, it is possible that Chinese localization policies are now tapping into this knowledge to support their projects. Yet, the quality of such research cannot be assessed by our research design in detail. Reviewing this literature qualitatively is a potential future avenue for this research agenda. In any case, the focus on Central Asian internal trends implies a focus and attention to local needs that has the potential to tame Chinese self-interested tendencies that seem to have characterized early theorizations of Chinese projects in Central Asia.

Moving to state narratives, themes like the BRI or the concept of good-neighbourliness are clearly pushed by Chinese research communities. But Xi Jinping’s theoretical contributions to foreign policy are not discussed in the Chinese Central Asian studies literature. The ‘New Type of Great Power Relations’, the ‘Community of Shared Future for Mankind’ and the three global initiatives (development, security and civilization) do not generate separate topics due to their lack of relevance in our corpus. Another common theme in Western academia is the role of Xinjiang-related policies in shaping Chinese views on Central Asia. Our findings confirm this trend through the stable relevance of analyses of Xinjiang in Central Asia in our corpus, yet they do not collocate its birth in the recent security turn of Western scholarship on China-Central Asia relations after 2013. Our Xinjiang topic is prevalent throughout our timeframe. In parallel, the analysis of our cultural clusters seems to suggest that governmental priorities did shape research priorities in cultural and sociological studies, for example the extensive focus on the ancient Silk Roads in a historical and cultural perspective or the use of archaeology to find common heritage between the Chinese and Central Asian peoples. Yet, the temporal pattern of thematic development in our linguistic cluster seems to support the role of researchers in attracting attention to specific themes, in this case the need for better methods to teach the Chinese language in Central Asia, due to the relevance of the region.

Our research provides an important methodological contribution that involves a strategy for quantitatively exploring research outputs inductively, which we advise should be followed by qualitative deep dives into specific academic elements of our original dataset that we offer in open access for further research. The strategy reduces selection bias by inductively examining themes in Central Asian studies in China and how they evolve over time. We test our strategy by triangulating deductive notions from Western academic research on China in Central Asia to explore how an inductive quantitative step can provide a nuanced starting point to explore China’s knowledge production on Central Asia.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.5 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their constructive comments. We also would like to thank Dr Edward Lemon for reading and commenting an earlier draft of the article and Anastasia Zhu, who was part of the original team that worked on an earlier stage of this project for the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs.

Data availability

Our dataset can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23648466.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://oec.world/en

2 See Sciorati’s (Citation2022) analysis on this aspect.

3 The authors note that it is important to consider that while increased accessibility to CNKI indicates significant growth in research output, past publications may not have been digitised or categorised, making it hard to quantify how substantial the expansion of regional studies has been in reality.

4 The decision to use abstracts instead of entire papers is connected with accessibility to CNKI from Western academic institutions, as well as for comparability. While analysing publications in their entirety would have provided more nuanced results, it would have limited the analysis to articles that are accessible from the institutions where the authors are based.

5 This study does not inquire into the connections between think tanks and the state in the Chinese context, or toward researchers and government policymaking, but studies that scrutinise funding and research agendas can be found in the work of Haiyun Feng and He (Citation2020).

References

- Bagozzi, B. E., and D. Berliner. 2016. “The Politics of Scrutiny in Human Rights Monitoring: Evidence from Structural Topic Models of US State Department Human Rights Reports.” Political Science Research and Methods 6 (4): 661–677. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.44.

- Barusch, A., C. Gringeri, and M. George. 2011. “Rigor in Qualitative Social Work Research: A Review of Strategies Used in Published Articles.” Social Work Research 35 (1): 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/35.1.11.

- Chen, T. C. 2010. “China’s Reaction to the Color Revolutions: Adaptive Authoritarianism in Full Swing.” Asian Perspective 34 (2): 5–51. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2010.0022.

- Chen, X. 2023. “Joint Archaeology Project Writes new Chapter of China-Uzbekistan Friendship”, Global Times, May 16, 2023. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202305/1290831.shtml.

- Clarke, M. E. 2011. Xinjiang and China's Rise in Central Asia: A History. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203831113.

- Combei, C. R., and D. Giannetti. 2020. “The Immigration Issue in Twitter Political Communication: Italy 2018-2019.” Comunicazione Politica 21 (2): 231–265. http://doi.org/10.3270/97905.

- Cooley, A. 2021. “On the Brink and at the World’s Edge: Western Approaches to Central Asia’s International Politics, 1991–2021.” Central Asian Survey 40 (4): 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2021.1974818.

- Cooley, A., and D. Nexon. 2020. Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190916473.001.0001.

- Dadabaev, T. 2018. “‘Silk Road’ as Foreign Policy Discourse: The Construction of Chinese, Japanese and Korean Engagement Strategies in Central Asia.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 9 (1): 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2017.12.003.

- Dadabaev, T. 2020. “Discourses of Rivalry or Rivalry of Discourses: Discursive Strategies and Framing of Chinese and Japanese Foreign Policies in Central Asia.” Pacific Review 33 (1): 61–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2018.1539026.

- Dadparvar, S., and H. Azizi. 2019. “Confucian Influence: The Place of Soft Power in China’s Strategy Towards Central Asia.” China Report 55 (4): 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445519875233.

- De Vries, E., M. Schoonvelde, and G. Schumacher. 2018. “No Longer Lost in Translation: Evidence That Google Translate Works for Comparative Bag-of-Words Text Applications.” Political Analysis 26(4): 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.26.

- Feng, H., and K. He. 2020. “The Study of Chinese Scholars in Foreign Policy Analysis: An Emerging Research Program.” Pacific Review 33 (3-4): 362–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2020.1738538.

- Frankopan, P. 2019. The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World. London: Bloomsbury.

- Global Times. 2017. “China’s Archaeologists Becoming Major Players at Excavations Around the World”, Global Times, October 11, 2017, www.globaltimes.cn/content/1069823.shtml.

- Godehardt, N. 2014. The Chinese Constitution of Central Asia. Basingstoke: Palgrave and Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137359742.

- He, K., and L. Liu. 2020. “Status Quo of International Central Asian Studies: Based on Collected Translations of Studies on Ethnic Relations and Ethnic Conflicts in Central Asia” (Guoji Zhongya yanjiu xianzhuang fenxi – jiyu “zhongya minzuguanxi yu minzuchontu yanjiu zongyi”).” Russian, East European & Central Asian Studies 3: 143–154. http://www.oyyj-oys.org/Magazine/Show?id = 75038.

- Hillman, J. E. 2020. The Emperor's New Road: China and the Project of the Century. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300256079.

- Hu, Z. 2017. “A Study of the Impact of Political Risk in Host Countries on Overseas Direct Investment- The Case of Central Asian Countries” (dongdao guo de zhengzhi fenxian dui wai zhijie touzi de yingxiang yanjou-yi zhong yazhou guojia wei lie).” Nashui (16): 114–115. https://cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2017&filename=NASH201716087&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=d01EsgdNPUXDDuEko8PdJNBFdekSGv4TipDPdvsDNS-5otmpbuqWQE_nQGBVaKVC.

- Jardine, B., and E. Lemon. 2020a. “In Russia’s Shadow, China’s Rising Security Presence in Central Asia.” Kennan Cable 52. May 2020. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-52-russias-shadow-chinas-rising-security-presence-central-asia.

- Jardine, B., and E. Lemon. 2020b. “Avoiding Dependence: Central Asian Security in a Multipolar World.” Oxus Society, 28 September 2020, https://oxussociety.org/avoiding-dependence-central-asian-security-in-a-multipolar-world/.

- Jardine, B., and E. Lemon. 2021. “Central Asia’s Multivector Defense Diplomacy.” Kennan Cable 68. May 2021, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-68-central-asias-multi-vector-defense-diplomacy.

- Jia, G., W. Zhang, and Z. Fang. 2015. “Dangqian zhongya diqu anquan jushi de tedian ji zoushi fenxi” (A Contemporary Analysis of the Characteristics and Trends of Security in Central Asia).” Journal of Xinjiang University 43 (1): 91–96. https://doi.org/10.13568/j.cnki.issn1000-2820.2015.01.022.

- Karrar, H. H. 2016. “The Resumption of Sino-Central Asian Trade, C. 1983-94: Confidence Building and Reform Along a Cold War Fault Line.” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1155384.

- Kavalski, E. 2010. “Shanghaied Into Cooperation: Framing China’s Socialization of Central Asia.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 45 (2): 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909609357415.

- Kerr, D., and L. Swinton. 2008. “China, Xinjiang, and the Transnational Security of Central Asia.” Critical Asian Studies 40 (1): 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710801959174.

- Larson, D. W. 2020. “An Equal Partnership of Unequals: China’s and Russia’s new Status Relationship.” International Politics 57(5): 790–808. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00177-9.

- Laruelle, M., and S. Peyrouse. 2012. The Chinese Question in Central Asia – Domestic Order, Social Change and the Chinese Factor. London: Hurst.

- Li, L., and N. Yang. 2016. “Zhongguo yu zhongya guojia nongchanpin maoyi yingxiang yinsu shizhengyanjiu” (An Empirical Study on Factors That Influence Agricultural Trade Between China and Central Asia).” Xinjiang nong ken jingji (Xinjiang Farming and Land Reclamation Economy) 7: 41–47. https://oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2021&filename=JGYK202102004&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=ZrXmsYTpyjfXBiamk3yJNuCStfqBmCiFhy6_GVd5rkMjalBRY6jbG7iijNWWh8qY.

- Li, Q. 2010. “Wo guo yu zhongya diqu maoyi zhong renminbi jiesuan de yuanyin fenxi”. (Analysis of the Causes of Settlements in Renminbi in Trade Between China and Central Asia).” Zhejiang Jinrong 4. https://oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2010&filename=ZJJR201004036&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=3hL8aRLP-MEmHN6b1JWkr90AGsKUfd8I4Aq7LbNWmB5EuG-qlo8X1i0UbbdavXyx.

- Lucas, C., R. A. Nielsen, M. E. Roberts, B. M. Stewart, A. Storer, and D. Tingley. 2015. “Computer-Assisted Text Analysis for Comparative Politics.” Political Analysis 23 (2): 254–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpu019.

- Maracchione, F. 2023. “Multivectoral? A Quantitative Analysis of Uzbekistan’s Foreign Policy Communication at the United Nations.” Eurasiatica, 161–191. https://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-667-1/009.

- Maracchione, F., G. Sciorati, and C. R. Combei. 2024. “Changing Images? Italian Twitter Discourse on China and the United States During the First Wave of COVID-19.” The International Spectator, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2023.2299452.

- Markey, D. S. 2021. China's Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190680190.001.0001.

- Mokry, S. 2022. “What is Lost in Translation? Differences Between Chinese Foreign Policy Statements and Their Official English Translations.” Foreign Policy Analysis 18 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orac012.

- Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs. 2023. Database: Tracking Protests in Central Asia. https://oxussociety.org/projects/protests/

- Petersen, A., and R. Pantucci. 2022. Sinostan: China’s Inadvertent Empire. Oxford University Press.

- Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. 2021. “Uzbekistan’s Online Religious Revival”, Foreign Policy, April 22, 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/22/uzbekistan-online-religious-revival-islam-radicalism/.

- RFE/RL. 2018. “Kyrgyz Ex-PM Isakov Charged With Corruption Over Power-Plant Shutdown,” May 30, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/kyrgyz-ex-prime-minister-isakov-charged-corruption-power-plant-shut-down/29258993.html.

- Roberts, M. E., B. M. Stewart, and D. Tingley. 2019. “Stm: An R Package for Structural Topic Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 91 (2): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02.

- Roberts, M. E., B. M. Stewart, D. Tingley, C. Lucas, J. Leder-Luis, S. K. Gadarian, B. Albertson, and D. G. Rand. 2014. “Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Responses.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 1064–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12103.

- Sciorati, G. 2022. “‘Constructing’ Heritage Diplomacy in Central Asia: China’s Sinocentric Historicisation of Transnational World Heritage Sites.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 29 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2022.2141718.

- Sciorati, G. 2023. “Self-Othering e Neighbouring: La costituzione dell’Asia centrale nel discorso internazionalistico cinese con la Belt and Road Initiative” (Self-Othering and Neighboring: The Constitution of Central Asia in the Chinese internationalist discourse with the Belt and Road Initiative).” OrizzonteCina 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.13135/2280-8035/7235.

- Seiwert, E. 2023. “China’s Search for Partners with the Same Worldview: Expanding the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Family.” Asian Affairs 54 (3): 453–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2023.2230796.

- Strongney, A. 2023. “Russia Embraces China’s Renminbi in Face of Western Sanctions,” Financial Times, March 26. https://www.ft.com/content/65681143-c6af-4b64-827d-a7ca6171937a.

- Tutumlu, A. 2021. “Central Asia: From Dark Matter to a Dark Curtain?” Central Asian Survey 40 (4): 504–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2021.1991886.

- Wang, F. 2015. “The effect of the renaissance of the Silk Roads on Chinese foreign aid” (fuxing sichou zhi lu yu zhongguo duiwai yuanzhu).” Heilongjiang National Series (heilongjiang minzu congkan) 2: 48–53. https://doi.org/10.16415/j.cnki.23-1021/c.2015.02.009.

- Wang, X., and X. Zhang. 2013. “Zhongya liuxuesheng tigao hanyu xiezuo jineng de xuexi celüe” (Learning Strategies for Central Asian Students to Improve Chinese Writing Skills).” Yuwen Jianshe (Language Planning) 8(2). https://doi.org/10.16412/j.cnki.1001-8476.2013.24.026.

- Winter, T. 2019. Geocultural Power: China’s Quest to Revive the Silk Roads for the Twenty-First Century. Silk Roads. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226658490.001.0001.

- Xiao, B. 2019. “The Central Asian Studies in China: Knowledge Growth, Knowledge Discovery and Future Direction of Development” (Zhongguo zhongya yanjiu: zhishi zengzhang, zhishi faxian he nuli fangxiang).” Russian, East European & Central Asian Studies 5: 1–26. CNKI:SUN:EAST.0.2019-05-001.

- Yang, J. 2014. “Lun Zhiyue zhongya minzhu zhengzhi zhuanxing jincheng de zhu yinsu” (On the Factors Restricting the Process of Democratic Political Transformation in Central Asia).” Guowai Lilun Dongtai (Overseas Theoretical Developments) (3): 73–79. CNKI:SUN:GWLD.0.2014-03-012.

- Yang, L. 2023. “China to Limit Access to Largest Academic Database”. Voice of America, March 30. https://www.voanews.com/a/china-to-limit-access-to-largest-academic-database-/7029581.html.

- Zeng, J. 2020. Slogan Politics: Understanding Chinese Foreign Policy Concepts. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6683-7.