ABSTRACT

This qualitative study explores the opportunities and challenges of collaboration experienced by social workers and police officers when dealing with cases of intimate partner violence (IPV) and stalking. The study aims to examine their collaborative approaches in risk assessment and risk management by identifying the structures, supports, and foundations crucial for effective collaboration. Our data, collected from twelve interviews and one focus group interview with social workers and police officers, reveals that collaboration was facilitated by assigning specific roles to involved parties, proximity, structure and professionalism. These key factors emerged as crucial and contributing to the effectiveness of the collaborative efforts. Practitioners should consider integrating these key elements into their practices to enhance and improve collaboration when addressing cases of IPV and stalking. The study underscores the need for a well-defined framework and support structures to optimise the collaborative response to such complex and sensitive issues.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) and post-separation violence, such as stalking, constitute pervasive individual, societal and public health problems. Globally, 26% of women report victimisation by a current or former partner (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2021). IPV is framed and understood by The Istanbul Convention as violence against women, characterised as a gendered act resulting in ‘physical, sexual, psychological, or economic harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life’ (European Institute for Gender Equality [EIGE], Citation2019). IPV refers to women’s self-reported experiences of violence perpetrated by a current or former male intimate partner (WHO, Citation2021). In Sweden, the estimated lifetime prevalence of IPV is 24% (BRÅ, Citation2014). Such violence causes a major strain on both victims and society, where resources provided to reduce violence show low effect since both rates of prevalence (WHO, Citation2021) and recidivism after reporting to the police remains high (e.g. Belfrage & Strand, Citation2012; Bennett Cattaneo & Goodman, Citation2005; Petersson & Strand, Citation2017; Richards et al., Citation2014; Tayebi & Strand, Citation2022). Moreover, the quality of life remains low for victims and their children (Hansen et al., Citation2010; Logan & Walker, Citation2010) and societal protection for women often fails or is not tailored to women’s needs (Vikander et al., Citation2023).

While Sweden has a national strategy to promote gender equality and specific goals to prevent men’s violence against women, there are still numerous obstacles and deficiencies in working preventively to counteract violence, as well as shortcomings in violence management. Previous research has indicated that effective prevention efforts necessitate structured risk management through collaborative work between agencies (Logan & Walker, Citation2018; Logan & Walker, Citation2017; Stanley & Humphreys, Citation2014; Youngson et al., Citation2021), a practice that is currently lacking in Sweden. This study aims to explore experiences of opportunities and challenges in inter-agency collaboration between social workers and police officers when working with cases of IPV including stalking.

Risk assessment and risk management in working with IPV

For the police and social services to be able to combat IPV they must master two central parts: risk assessment and risk management. While risk assessment can be defined as a process of determining risk, risk management encompasses the actions and measures identified and taken after the assessment of risk (Thompson & Thompson, Citation2008). Risk management, in turn, consists of protective actions and support that need to be taken to minimise the assessed risk of recidivism, and thus prevent recidivism (Andrews et al., Citation2006, Citation2011). Several challenges to master those tasks have previously been identified, such as professionals inconsistent use of tools, varying expertise in risk management, implementation and providing staff with relevant training and guidelines (Viljoen et.al., Citation2018). Effective risk assessment also requires the use of a validated tool specifically designed for IPV, administered by a professional with expertise and experience (Holt & Lynne, Citation2021; Roehl et al., Citation2005), and a profound understanding of the intricate dynamics of domestic violence (Holt & Lynne, Citation2021). Additionally, and importantly, effective collaboration between all involved parties is essential.

Social services and the police in Sweden have established routines for how risk assessment is to be carried out, but there are different risk assessment methods and a variety of tools. The Freda-method is often used by the social service (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2014), and the B-SAFER is predominantly used by the police (Kropp et al., Citation2010). In Sweden, despite efforts from both police and social services, a reported lack of effective risk management may contribute to recidivism rates of up to 40% among offenders (Belfrage & Strand, Citation2012; Svalin et al., Citation2018; Tayebi & Strand, Citation2022).

Inter-agency collaboration

In Sweden, risk management conducted through collaborative efforts among authorities has been found to be somewhat problematic (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2021; Olsson et al., Citation2023). Despite the existence of several laws and regulations in Sweden, as in many countries, obliging agencies to address both aspects, there is a deficiency in more specific routines on how to handle IPV, as well as lacking routines and structures for collaboration. Despite the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration when social problems cross disciplines, police and social workers often remain ensconced within their disciplinary boundaries and perspectives (Kaip et al., Citation2022; Ward-Lasher et al., Citation2017). This means that police and social service most often work separately from each other and collaborate when they deem it necessary. In addition, communication difficulties can arise in cooperation when actors have different perceptions of the situation, and when they feel excluded from important information, they cannot see the whole picture or they do not have a clear understanding of their role and the roles of their interprofessional colleagues (Ambrose-Miller & Rachelle Ashcroft, Citation2016; Kaip et al., Citation2022). There is often no standardised routine or structure for how collaboration should be carried out, leaving it to individual social workers or police officers to find solutions and develop an effective risk management plan for victims.

Nevertheless, preventing repeated instances of IPV often necessitates coordinated efforts from several actors (Robinson, Citation2006). Despite the shared responsibility for support and protection, the roles and tasks are specific to each agency involved. In this regard, the police are responsible for both the criminal investigation, and the protection of victims (Storey et al., Citation2014). Social services, on the other hand, are responsible for ensuring that victims and their social situation, which also includes children living at home, receive adequate support and help. For example, the police initiate a proposal for sheltered housing as an intervention, while the social service are responsible for planning and costs for the intervention. The police can then assist social services in the effort based on the needs that emerge. Therefore, a continuous collaboration between agencies seems essential to optimise the effort.

For this study we define collaboration between police and social service regarding risk assessment and risk management of IPV as sharing work, knowledge and resources aiming to prevent recidivism as well as re-victimisation. Numerous challenges may arise in this collaborative context. Legal constraints on information sharing and potential gaps in documentation pose significant hurdles. This becomes particularly critical in cases involving protective measures like sheltered housing, where collaboration is crucial. Overall, variations in risk assessment methods, resource constraints, and a lack of collaboration often lead to victims receiving parallel risk management strategies independently implemented by police and social services, rather than through collaborative efforts. Such parallel processes have led to fatal outcomes such as femicide (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2018, Citation2021).

An already existing way of enabling collaboration between agencies is the so-called Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARAC), which are used primarily in Great Britain, but also in Finland. The purpose of these MARAC meetings is to share information between agencies in cases that are assessed to be of high risk of repeated IPV. Collaboration is seen as necessary since no single agency can form a comprehensive understanding of all needs for victims of IPV (Piispa & Lappinen, Citation2014; Robbins et al., Citation2014; SafeLives, Citation2014). Follow-ups on the crime prevention effects of MARAC meetings show positive results, with lower levels of re-victimisation (Piispa & Lappinen, Citation2014; Robinson, Citation2006).

Success factors for collaboration have been shown to be awareness of other disciplines, effective communication, team structure, willingness to collaborate, shared responsibilities and mutual trust (Rumping et al., Citation2019). Moreover, Stanley and Humphreys (Citation2014) state that success factors for a coordinated collaboration where professionals from different agencies jointly perform risk assessments, are a common risk assessment method, a common training that allows learning and development of implementation, co-location or a close placement of the collaborating actors to reduce the gap between authorities and operations, institutional empathy i.e. an understanding of each other’s work including tasks, roles and conditions. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no investigation into experiences related to multi- and inter-agency collaboration in the context of IPV in Sweden thus far.

Aim and research questions

The overall aim of the study was to investigate and understand the experiences, opportunities, and challenges within inter-agency collaboration between social workers and police officers while dealing with risk assessment and risk management to prevent IPV. The study includes the following research questions:

What are the shared perspectives of participants regarding collaboration in risk assessment and risk management of IPV cases?

What are the factors that can enhance functional inter-agency collaboration in risk assessment and management?

Materials and methods

This qualitative study was conducted as part of the longitudinal RISKSAM research programme (2019–2025). This programme aims to improve and implement a sustainable and evidence-based model for risk management and collaboration, the RISKSAM, within the Swedish social services. Additionally, the programme seeks to evaluate the outcomes of implementing this model, focusing on aspects such as violence reduction, cost-effective collaboration with the police, and the improvement of the quality of life for victims in cases of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and stalking. The RISKSAM model is inspired by the work on the collaborative MARAC meetings (Robbins et al., Citation2014; Robinson, Citation2006). The study strictly adhered to the guidelines of The Swedish Research Council (2017) and how to process data (General Data Protection Regulation; GDPR). It has been approved by the Ethics Review Authority (Dnr 2021–05889–02).

Research design

To collect data, we opted for a combination of individual interviews and a focus group interview. This design was considered suitable for uncovering and capturing both individual experiences, and shared perceptions and understandings of social workers and police officers responding to IPV (Gubrium et al., Citation2012). Data collection took place during the spring of 2021. Similar to many Swedish municipalities, the majority of social workers in this study had diverse roles. Participating police officers encompassed IPV investigators. In general, the majority of participants were female, 15 females and 2 males. First, 12 semi-structured interviews were conducted individually with social workers (all female) employed within the Swedish social services. Secondly, a focus group interview with a total of two (male) police officers and three (female) social workers in a countryside county in Sweden was conducted. The informants in this interview already had a close collaboration with regular meetings.

Recruitment of informants

We employed a purposeful sampling, which involves carefully selecting information-rich cases, to gather necessary knowledge from a small sample (Patton, Citation2015). Participants were recruited through the RISKSAM programme to explore how agencies collaborate before implementing the RISKSAM model. The inclusion criteria for informants to participate in any of the interviews were either being a social worker or a police officer and working with responding to (i.e. assessing and managing risk) IPV.

The informants in the individual interviews were recruited from two social services offices in two separate counties: countryside and urban. All informants worked with clients exposed to IPV. Some worked with counselling and support, and others worked with investigations focusing on children or adults regarding their need for support and protection. The median age of our informants was 38 (ranging from 28 to 64 years). The median length of years working specifically with domestic violence was 7.5 years (ranging from 1 to 20 years). A similar range applied to informants in the focus group interview, but no personal data was collected from them.

Procedures and data analysis

For data collection, we employed a semi-structured interview guide, developed with input from social workers. The interview questions were designed to uncover essential factors and challenges for establishing sustainable and effective collaboration in the context of risk assessment and risk management related to IPV. Prior to the interviews, participants were provided with information about our study and signed a consent form. The interviews were conducted remotely through a digital meeting platform, recorded, and subsequently transcribed for analysis.

We chose to conduct a thematic analysis to capture both manifest and latent aspects of our data using a single analytical approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Our analysis followed the six steps or phases advocated by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): First, the authors became familiar with the transcribed text by re-reading it several times. Second, interesting characteristics were sorted into relevant codes. Third, codes were turned into preliminary themes. Fourth, we checked that the themes worked in relation to the coded extracts and the entire data set. Fifth, we defined and refined each theme’s specifics, resulting in four clearly defined and named themes. Finally, we planned how the final analysis would be performed in text and a graphic model in this paper. The analysis process involved joint reflective deliberations until agreement was reached within the research group (Patton, Citation2015). In the findings section, informants are referred to as either Interview Person and number (i.e. IP1, IP2 etc.) or Focus Group Interview (FGI) and profession and number (i.e. social worker: SW1, SW2 etc; and police officer: PO1 or PO2).

Results

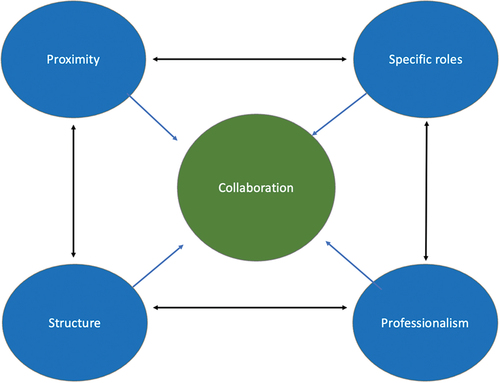

Through our analysis of empirical data, we identified the themes presented in . Although these themes share certain similarities, they effectively communicate the key findings of interest within our dataset.

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes.

Theme 1: specific roles

Specific and well-defined roles for the collaborating actors stands out as a crucial factor for functioning inter-agency collaboration in our study. We could also see that clear roles were supported by the sub-themes: different missions, areas of responsibilities, and shared responsibilities, indicating that well-defined roles were important for effective collaboration between the police and social services.

The social workers described both opportunities and challenges when collaborating with the police. The ability to act depended on how the roles were defined and whether there were well-defined limits to authority and capacity. An important factor was that social services might have classified information about the client that the police did not have access to, and vice versa. Our respondents reported positive collaboration experiences, where a mutual understanding of each other’s missions and roles enabled them to collaborate effectively for the benefit of the client, relying on their respective roles and responsibilities (IP2, IP3, IP4, IP7, IP8). Having insight into each other’s information and roles and being familiar with the professional language of each discipline, facilitated collaboration.

During the focus group interviews, participants emphasised the importance of collaboration across entire spectrum of activities, spanning from initial risk assessment through risk management to subsequent follow-up procedures. They acknowledged that no single agency could manage the entire process in isolation. Instead, they emphasised that effective collaboration necessitated clear communication and coordination between the social workers and police officers involved in the case. As one informant put it: ‘We are probably simply dependent on each other’. (FGI: PO1) This sentiment echoed in individual interviews, where a respondent expressed: ‘Collaboration is A to Z’ (IP7). Several professions must gather around the client and collaborate, and the respondent continued:

Even if I were to work myself to death, I wouldn’t, I’m not enough, it needs more people, it needs other professionals, we kind of need to gather around these people to make things easier, so I think that’s the most important thing. (IP7)

A police officer in the focus group highlighted that effective collaboration is achieved when established teams from both professions work together regularly. This shared responsibility, coupled with mutual respect for each other’s competencies, optimises efforts for the benefit of the clients. Therefore, our findings emphasise the importance of clear roles and responsibilities along with a shared commitment for successful collaboration.

Theme 2: proximity

In our interviews, we discovered that the informants shared the belief that proximity, close relations and trust were key components of effective and successful collaboration in the work with IPV cases. Moreover, they expressed that proximity provided good conditions for functional collaboration between agencies. Our second theme, proximity was supported by the sub-themes trust and consensus.

Both social workers and police officers stated the importance of talking to each other in person or on the phone. On several occasions, it came up how important it was to know people, i.e. that the persons working on the same case knew and trusted each other. One social worker said that she preferred to use her personal contacts within the police (IP1). Guidelines and routines in all respect, but consensus and trust in each other were extremely important for functioning collaboration:

It’s not just this that you must have particular guidelines and routines and do your job in a certain way, but it is about, I think it is about, very much here, that you have trust and confidence in each other. (FGI: SW2)

Our informants in the individual interviews thought that collaboration with the police worked well. One informant considered that this was largely due to the physical proximity and the fact that they were in the same building (IP7). Trust and confidence among those working on the case were also mentioned as important factors for successful collaboration (IP3; IP4). Furthermore, our findings suggest that consensus among the actors involved was often necessary to handle complex cases effectively. This ensured that the risk assessments were well-informed and beneficial for the client. As one social worker stated in the focus group interview:

We need to have a consensus on what we think about the various risk factors, and it is always good to work together sometimes and meet in it and be able to talk about it so that it is as legally secure as possible. (FGI: SW1)

The respondents emphasised the importance of proximity in their collaboration. For example, one informant mentioned that social services and police were in the same building and could easily communicate with each other in person (IP7). Overall, our findings suggest that proximity between professionals can lead to more efficient collaboration, where individuals contribute with their unique skills and knowledge.

Theme 3: structure

The data indicated that professionals highly valued a clear and well-defined structure for collaboration to effectively conduct risk assessments. In our study, the informants defined structure in collaboration between social workers and police as supported by routines, such as regular meetings, explicit forums, and the everyday use of assessment instruments. These elements comprised the three identified sub-themes.

There are established routines in Sweden for how risk assessment in cases with IPV should be carried out. Different agencies, however, may use them differently and practise different models for risk assessment. It also varies if there are routines for collaboration between agencies or not. In our study, we found that effective handling of IPV cases was perceived to be based on good cooperation between professionals (IP3, IP4). The importance of considering the client’s perspective was also underscored, with one participant accentuating the need to coordinate and consolidate meetings so that clients did not have to attend multiple meetings and repeat themselves (IP9). Additionally, a clear and defined structure of meetings and forums was recognised as crucial for successful collaboration. Respondents in the focus group interview gave examples of this meeting structure:

We often have a joint meeting with the client and physically sit down together and see what has happened, and we are both professionals from social services and the police. So together, we make a risk assessment based on what has happened currently, what has happened in the past and what the police know about the perpetrator that we do not know about at the social services. So that is why we get a completely different, overview from the start. (FGI: SW2)

The quote above, describing how a risk assessment meeting between social services and the police typically occurs in a medium-sized municipality in Sweden, emphasises several aspects of effective collaboration. The approach was described as beneficial for the client, illustrating a shared commitment from both social services and the police.

A good structure also makes the areas of responsibility clearer for both professionals and women seeking help. Our informants stressed the importance of using a shared risk assessment method when working with clients. As one of our informants noted, sharing the same method ensures that all professionals involved speak the same language and ask the same questions (IP7). This was also consistent with the consensus we discussed in the previous theme. One example of structure that emerged was regular monthly meetings where everyone could raise questions and urgent needs. In the focus group interview our respondents explained that these meetings were organised with agendas and preparations beforehand (FGI: SW1 & PO2). It became clear that both professions appreciated the collaboration and believed it benefitted all involved actors.

Theme 4: professionalism

Our fourth and final theme, professionalism, stands out as essential and seemed to build on professional workers who were specialised in IPV, were experienced in the field, and sometimes had a strategic responsibility in this area in the organisation. The sub-themes were competencies, professional attitude, and specialists.

During the interviews, there was a strong emphasis on the importance of maintaining a professional attitude for fostering effective collaboration. The informants articulated that professionalism could manifest as an attitude or through professional conduct during client meetings. They highlighted that conducting collaborative meetings and performing risk assessments based on well-structured interactions with the client contributes to creating a professional impression. A professional approach could be facilitated by routines, instruments, and guidelines (IP8) ‘I think it gives a professional impression when they know we have certain methods’, one social worker says. (FGI: SW2)

Collaboration appeared most effective when all involved parties were specialised in handling such cases and clients. In the focus group interview, one informant argued that both social workers and police should possess knowledge about violence as part of their foundational education, along with ongoing education throughout their professional careers (FGI: SW1). Expertise in IPV stands out as crucial for risk assessments, emphasising the need for a shared knowledge base among all involved. In situations without regular dialogue, collaboration becomes more challenging, especially when working with individuals lacking specific skills or experience in this area (FGI: PO1, PO2). One informant claimed that: ‘Someone needs to have the sort of strategic responsibility for this issue in each municipality’. (FGI: SW1)

In smaller communities, a challenge arises due to insufficient resources to train and specialise existing staff. Two respondents in the focus group interview highlighted that individuals lacking expertise and experience in IPV cases are also more challenging to cooperate with (FGI: PO1, PO2). The lack of expertise was identified as a challenge, particularly in rural communities. The findings underscore that the absence of structure, clear roles, and proximity can impede efforts to enhance professionalism. Establishing this collaboration is more challenging in smaller municipalities without specialised staff and family violence teams, setting them apart from larger counterparts.

Discussion

The overall aim of the study was to investigate and understand the experiences, opportunities, and challenges within inter-agency collaboration between social workers and police officers while dealing with risk assessment and risk management to prevent IPV. A specific aim was to identify key factors that contribute to effective and sustainable collaboration between agencies working these cases. Through our analysis, we identified four key themes: Proximity, Specific Roles, Structure, and Professionalism, which all together facilitated and fostered productive collaboration. We believe these factors are interconnected and interdependent, and their effective implementation is key to functional collaboration between the two agencies. The relations between them can be illustrated as in the figure below.

Each of the four components plays a pivotal role in fostering effective collaboration, mutually reinforcing one another. Proximity, for instance, not only facilitates the establishment of a robust structure but also aids in clarifying specific roles, making them transparent and well-understood among team members. Our findings strongly suggest that delineating distinct roles not only enhances professionalism within the team but also in the interactions with clients. Moreover, professionalism serves as both a catalyst for and a product of a well-structured collaboration.

Effective inter-agency collaboration hinges on a shared responsibility for tackling complex issues and specialised roles grounded in knowledge and experience. Professionals emphasised the significance of clear roles in successful collaboration during our interviews, acknowledging the distinct missions of each agency. The relations between the themes are visualised in . Our findings are consistent with those of Storey et al. (Citation2014), Ambrose-Miller and Rachelle Ashcroft (Citation2016), Rumping et al. (Citation2019) and Manthorpe et al. (Citation2010), all showing that clear roles and awareness and understandings of each other’s roles are promoting functioning collaboration and promoting effective risk management. Recognising differences and collaborating within their expertise, social workers and police officers can more effectively address issues of IPV. Interviewees underscored the importance of consensus on client issues and risk assessments, fostering trust and enhancing collaboration between the two agencies. In addition, cooperation between police and social workers was favoured if the police perceived that the social workers were familiar with the language of criminal justice and had knowledge of risk assessment (Ward-Lasher et al., Citation2017).

Our findings of success factors for effective collaboration are in line with other research such as emphasising proximity and trust (Rumping et al., Citation2019), personal relationships (Hesjedal et al., Citation2015), and physical closeness, such as sharing offices or being in the same building. This proximity reduced the gap between the involved professions, fostering a mutual understanding of roles, missions, and conditions (Stanley & Humphreys, Citation2014). Proximity, achieved through physical closeness and regular collaboration, was identified among our social workers and police officers. This form of interaction helped cultivate familiarity and understanding between the agencies.

A recurring theme in our interviews was the importance of a good structure for effective work and collaboration. It has also been shown in previous research, as well as the significance of several actors building a system together (Rumping et al., Citation2019; Stanley & Humphreys, Citation2014). A Swedish study showed that structure provided a sense of security and stability, which enable social service workers to perform their job effectively (Olsson et al., Citation2023). Manthorpe et al. (Citation2010) found that shared policies and methods can help ensure that different actors operate within a common framework and follow established routines. This can foster collective responsibility and shared ownership of the issue.

By having a shared understanding of the frameworks and structures in place, participants in the collaboration can have more discretion to act and make decisions within that framework. Kaip et al. (Citation2022) also suggested joint training initiatives for the police and the social services to improve inter-agency working. Established routines and having access to methods in the form of such as risk assessment support was perceived as facilitating, and at the same time as part of a professional approach. However, their results demonstrated that the police found it problematic to cooperate with non-specialised social services due to the lack of knowledge and difficulty reaching the professionals whereabout. In addition, non-specialised social services expressed a desire for strategic management responsibility for issues specifically focused on family-based violence. Ambrose-Miller and Rachelle Ashcroft’s (Citation2016) research highlighted the potential challenges faced by social workers engaged in interprofessional teams when lacking a comprehensive understanding of their own roles or those of their colleagues. The study revealed that the absence of a well-defined social work role within these teams created opportunities for power differentials during decision-making processes. The significance of this matter is particularly pronounced in sparsely populated and rural areas, where the shortage of specifically trained social workers addressing intimate partner violence (IPV) tasks amplifies the potential impact of these challenges.

Our informants stressed the importance of working as professionals with a professional approach and sophisticated tools to benefit the clients. In environments where actors operate in close proximity, the establishment of a resilient structure becomes more feasible, enabling the pooling of expertise and fostering effective collaboration through well-defined roles and built trust. However, this poses a distinct challenge for centrally located police when partnering with social services in remote and rural areas. Nonetheless, further research is needed to thoroughly explore the challenges and opportunities associated with addressing IPV in sparsely populated and rural regions. The themes and factors identified in our study play a pivotal role in enhancing the success of collaborative efforts. The study underscores the necessity of implementing a well-defined framework and supportive structures to optimise the collaborative response to these complex and sensitive issues.

Implications for research and policy

This study highlights a knowledge gap concerning specific challenges and opportunities faced by police officers and social workers in rural areas when addressing men’s violence towards women. Rural areas present additional challenges in managing risks for IPV where respondents partly mentioned some of them. Edwards (Citation2015) demonstrated in their study that the prevalence of such violence in rural communities is similar to or greater than those in urban communities. Although several studies have shown that IPV in rural and remote areas is characterised as more severe and frequent compared to urban areas (Peek-Asa et al., Citation2011; Strand & Storey, Citation2019), more research is needed to explore the complexity of working with IPV, especially in different international contexts and rural areas. Barlow et al. (Citation2023) highlighted multiple factors complicating initiatives to tackle IPV in rural areas of England, encompassing structural, cultural, and practical aspects. However, there is a need for additional research on the collaboration between social workers and police addressing IPV in rural areas within a Swedish context, which may present distinct challenges when dealing with IPV cases, and specifically post-separation violence such as stalking. The objective would be to develop a sustainable working approach tailored for small municipalities in the long term.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Åsa Källström at Örebro University for her valuable contribution to the collection of a portion of our empirical data through the focus group interview. Additionally, we extend our thanks to all participants in our interviews for generously sharing their thoughts and experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna-Karin L. Larsson

Anna-Karin L. Larsson is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Örebro University, Sweden, with a PhD in History. Her research areas encompass historical studies on the health of children and youth, along with social science research on intimate partner violence and violence involving girls. Currently, she is conducting research within the Risksam programme, where she explores the roles of police officers and social workers in the risk assessment and management of domestic violence and stalking, with a specific focus on rural perspectives. Another area of keen interest for her is understanding the significance of risk management for women affected by these issues. [email protected]

Helén Olsson

Helén Olsson is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work and holds a PhD in Health Science from Karlstad University, Sweden. She has more than twenty years of experience in operational social work in social services. She has been involved in the RISKSAM programme on the implementation of a new model for the collaboration between the police and social services when it comes to intimate partner violence and stalking. Moreover, her research focuses on honour-based violence, victim support and risk assessment. Another area of interest is evidence-based practice and implementation processes and their importance for an organisation. [email protected]; [email protected]

Susanne J. M. Strand

Susanne J. M. Strand is a Professor of Criminology at Örebro University, Sweden. She is also an adjunct at the CFBS - Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia. She researches risks and risk management of violence in different contexts, with applied criminology as the academic base. Her current research concerns risk management for intimate partner violence, stalking and honour-based violence, where her longitudinal research programme RISKSAM (2019-2025) is conducted in collaboration with the police and the social service. [email protected]

References

- Ambrose-Miller, W., & Rachelle Ashcroft, R. (2016). Challenges faced by social workers as members of interprofessional collaborative health care teams. Health & Social Work, 41(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw006

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J. S. (2006). The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime & Delinquency, 52(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128705281756

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, S. J. (2011). The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model. Does adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(7), 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811406356

- Barlow, C., Davies, P., & Ewin, R. (2023). ‘He hits me and that’s just how it is here’: Responding to domestic abuse in rural communities. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 7(3), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868021X16535814891956

- Belfrage, H., & Strand, S. (2012). Measuring the outcome of structured spousal violence risk assessments using the B-SAFER: Risk in relation to recidivism and intervention. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 30(4), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2019

- Bennett Cattaneo, L., & Goodman, L. A. (2005). Risk factors for reabuse in IPV risk factors for reabuse in intimate partner violence a cross-disciplinary critical review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(2), 141–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005275088

- BRÅ, National Council of Crime Prevention. (2014). Brott i nära relationer: En nationell kartläggning. (Report 2014:8). www.bra.se

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Edwards, K. M. (2015). Intimate partner violence and the rural– urban–suburban divide: Myth or reality? A critical review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557289

- European Insitute for Gender Equality. (2019). Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European union. Retrived January 27, 2019, from https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/eiges-studies-gender-based-violence/estimating-costs-gender-based-violence-european-union

- Gubrium, J. F., Holstein, J. A., Marvasti, A. B., & McKinney, K. D. (2012). The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft. SAGE Publications.

- Hansen, R. F., Sawer, G. K., Begle, A. M., & Hubel, G. S. (2010). The impact of crime victimization on quality of life. Journal Trauma Stress, 23(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20508

- Hesjedal, E., Hetland, H., & Iversen, A. C. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration: Self-reported successful collaboration by teachers and social workers in multidisciplinary teams. Child & Family Social Work, 20(4), 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12093

- Holt, S., & Lynne, C. (2021). International review of the literature on risk assessment and management of domestic violence and abuse. In C. Bradbury-Jones, J. Devaney, R. J. Macy, C. Øverlien, & S. Holt (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of domestic violence and abuse (p. 834). Routledge.

- Kaip, D., Ireland, L., & Harvey, J. (2022). ”I don’t think a lot of people respect us” – police and social worker experiences of interagency working with looked-after children. Journal of Social Work Practice, 37(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2022.2036109

- Kropp, P. R., Hart, S. D., & Belfrage, H. (2010). Brief spousal assault form for the evaluation of risk (B-SAFER) version 2: User manual. Proactive Resolutions. Swedish translation.

- Logan, T., & Walker, R. (2010). Toward a deeper understanding of the harms caused by partner stalking. Violence and Victims, 25(4), 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.440

- Logan, T., & Walker, R. (2018). Advocate safety planning training, feedback, and personal challenges. Journal of Family Violence, 33(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9949-9

- Logan, T. K., & Walker, R. (2017). Stalking: A multidimensional framework for assessment and safety planning. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(2), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015603210

- Manthorpe, J., Hussein, S., Penhale, B., Perkins, N., Pinkney, L., & Reid, D. (2010). Managing relations in adult protection: A qualitative study of the views of social services managers in England and Wales. Journal of Social Work Practice, 24(4), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650531003651109

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2014). Manual för FREDA: Standardiserade bedömningsmetoder för socialtjänstens arbete mot våld i nära relationer. Art 2014-6-15. FREDA - Socialstyrelsen.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2018). Dödsfallsutredningar 2016–2017. www.socialstyrelsen.se

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2021). Socialstyrelsens utredningar av vissa skador och dödsfall 2018–2021. www.socialstyrelsen.se

- Olsson, H., Larsson, A. L., & Strand, S. J. M. (2023). Social workers’ experiences of working with partner violence. British Journal of Social Work, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad240

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publication Ltd.

- Peek-Asa, C., Wallis, A., Harland, K., Beyer, K., Dickey, P., & Saftlas, A. (2011). Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources. Journal of Women’s Health, 20, 1743–1749. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2891

- Petersson, J., & Strand, S. (2017). Recidivism of intimate partner violence among antisocial and family-only perpetrators. Criminal Justice & Behavior: An International Journal, 44(11), 1477–1495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817719916

- Piispa, M., & Lappinen, L. (2014) MARAK moniammatillista apua väkivallan uhrille [MARAC – multiprofessional help for victims of violence]. Evaluation report. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Discussion Paper 21.

- Richards, T. N., Jennings, W. G., Tomsich, E., & Gover, A. (2014). A 10-year analysis of rearrests among a cohort of domestic violence offenders. Violence and Victims, 29(6), 887–906. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00145

- Robbins, R., McLaughlin, H., Banks, C., Bellamy, C., & Thackray, D. (2014). Domestic violence and multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs): A scoping review. Journal of Adult Protection, 16(6), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-03-2014-0012

- Robinson, A. L. (2006). Reducing repeat victimization among high-risk victims of domestic violence: The benefits of a coordinated community response in Cardiff, Wales. Violence Against Women, 12(8), 761–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801206291477

- Roehl, J., O’Sullivan, C., Webster, D., & Campbell, J. (2005). Intimate partner violence risk assessment validation study: The RAVE study practitioner summary and recommendations: Validation of tools for assessing risk from violent intimate partners. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/209731.pdf

- Rumping, S., Boendermaker, L., & de Ruyter, D. (2019). Stimulating interdisciplinary collaboration among youth social workers: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(2), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12589

- SafeLives. (2014). Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARAC)g. https://safelives.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/MARAC%20FAQs%20General%20FINAL.pdf

- Stanley, N., & Humphreys, C. (2014). Multi-agency risk assessment and management for children and families experiencing domestic violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.003

- Storey, J. E., Kropp, R. P., Hart, S. D., Belfrage, H., & Strand, S. (2014). Assessment and management of risk for intimate partner violence by police officers. Using the brief spousal assault form for the evaluation of risk. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 41(2), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813503960

- Strand, S. J. M., & Storey, J. (2019). Intimate partner violence in urban, rural, and remote areas: An investigation of offense severity and risk factors. Violence Against Women, 25(2), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218766611

- Svalin, K., Mellgren, C., Torstensson Levander, M., & Levander, S. (2018). Police employees´ violence risk assessments: The predictive validity of the B-SAFER and the significance of protective actions. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 56, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2017.09.001

- Tayebi, N., & Strand, S. J. M. (2022). Policing stalking: The relationship between police risk assessment, risk management, and recidivism in stalking cases. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 9(3), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000186

- Thompson, N., & Thompson, S. (2008). The social work companion. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vikander, M., Larsson, A. K. L., & Källström, Å. (2023). Managing post-separation violence: Mothers’ strategies and the challenges of receiving societal protection. Published online. Nordic Social Work Research, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2023.2285988

- Viljoen, J. L., Cochrane, D. M., & Jonnson, M. R. (2018). Do risk assessment tools help manage and reduce risk of violence and reoffending? A systematic review. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 181–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000280

- Ward-Lasher, A., Messing, J. T., & Hart, B. (2017). Policing intimate partner violence: Attitudes toward risk assessment and collaboration with social workers. Social Work, 62(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx023

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization.

- Youngson, N., Saxton, M., Jaffe, P. G., Chiodo, D., Dawson, M., & Straatman, A. L. (2021). Challenges in risk assessment with rural domestic violence victims: Implications for practice. Journal of Family Violence, 36(5), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00248-7