ABSTRACT

This research explores school belonging (SB) experiences of young people in the UK who live under the legal status of a special guardianship order (SGO). A high proportion of these young people have had adverse childhood experiences, some are care experienced. This research uses case study to triangulate the perspectives of the young people, their guardians, and designated teachers (DTs) to develop understanding of school belonging, and considers the implications for educational psychologists (EPs), school policy, and staff practice. Seven case studies were undertaken, each including a young person, their guardian/s and their school DT, resulting in 21 semi-structured interviews. A hierarchical structured approach was used in all adult interviews, and personal construct psychology techniques were used in young people’s interviews. Individual case data were analysed using thematic analysis. Superordinate themes generated included identity, fitting in, diagnosis, agency, individuality and association, school’s community connection, systems as obstacles, relationship and connection to others, protection and autonomy, school processes, support and features, and organisational change. The findings emphasise the broad influences on the school belonging of this group, including individual characteristics, peer and staff relationships, school processes, and the communication and interaction between school, home, and the wider community.

Introduction

What is special guardianship?

Special guardianship (SG) predominantly sits within the broader category of formal kinship care in the UK (Wade et al., Citation2014). Formal kinship care includes children placed officially with family members through a legal order, for example, adoption, special guardianship, or a child arrangements order (Nandy & Selwyn, Citation2013). Common factors for children being required to leave their biological parents are: parental mental, physical illness, or disability; drug or alcohol misuse; child abuse or neglect; death of a parent; and domestic violence (Aldgate & McIntosh, Citation2006; Broad et al., Citation2001). A Special Guardianship order (SGO) is made under the Children Act (Citation1989) for a child to live with an appointed “special guardian” until they are 18. A Special Guardianship order is unlike adoption in that it is not a lifelong order and it does not legally end the child’s relationship with their birth family, but places a child or young person with someone permanently (a guardian) and gives this person enhanced parental responsibility for the child. For the year ending March 2020, 89% of SGOs were made to family members or friends (kinship carers), 9% to the child’s former foster families. There is an expectation of a maintained link with direct family members (Ashley et al., Citation2015) though this is often not specifically stipulated in the SGO. Some children living in guardianship have previously experienced a placement in care whilst a permanent placement is found. This previous care experience may attract additional resources. Literature indicates that there has been a marked increase in the number of SGOs in the UK (Simmonds, Citation2011) with SGOs as the most frequent permanency option for young people leaving care, with 930 placed in England in the first quarter of 2023/24 (CoramBAAF, Citationn.d.-a).

The proportion of breakdowns of guardianship placements is 5 per 100, in comparison to adoption breakdowns of 7 in 1000 (Harwin et al., Citation2019). Despite the rise in numbers of SGOs and the breakdown rates, there are only a handful of significant studies which explore these placements; some include the views of guardians and the young people, with a low focus on school experiences. Harwin, Alrouh, et al. (Citation2019) suggested that a research priority is to explore the views of children and young people living in special guardianship, and the current study aims to contribute to that area.

A high proportion of young people living in special guardianship experience complex emotional and behavioural difficulties (Harwin & Simmonds, Citation2020), specifically in expressing and managing their emotions (J. T. Selwyn et al., Citation2013), perhaps associated with the impact on child development of neglect, maltreatment, and loss pre-placement (J. Selwyn et al., Citation2014; Wade et al., Citation2014). Other reported areas of need include poor communication (J. Selwyn et al., Citation2014), concentration, focus, and confidence (Wade et al., Citation2014), and peer relationships (Aldgate & McIntosh, Citation2006). Wade et al. (Citation2014) found that many of the young people had accessed professional services: therapeutic (34%), educational (33%) or behavioural (52%) and that guardians dealing with the most challenging behaviour experienced higher levels of anxiety and strain; the educational progress and social skills of children with learning difficulties are not as good as in the general population (Wade et al., Citation2014). There is currently no governmental data gathered on the profile of special guardians by type of relative, their ethnicity, or age (CoramBAAF, Citationn.d.-b). However, Wade et al. (Citation2014) reported that in guardianship families (n = 230) 89% of primary carers were female; 111 were lone carers (two of these were male); 51% were grandparents; 41% were aged 50 plus at the start of the order. A disproportionately high level of guardianship families lived in poverty and were often economically disadvantaged; rates of long-term illness or disability amongst carers were higher than in the general population; carers’ wellbeing was significantly below average; respondents rarely felt relaxed, or close to other people; and lacked optimism about the future (Dunne & Kettler, Citation2007; Grandparents Plus, Citation2014; Welland et al., Citation2017).

Schools and special guardianship

Studies of SG provide important information about placements and the children’s wellbeing (Aldgate & McIntosh, Citation2006; Harwin & Simmonds, Citation2020; J. Selwyn et al., Citation2014; Wade et al., Citation2014) but there is a dearth of research about their school experiences. Gore Langton (Citation2017) speculates that, until relatively recently, many school staff thought of children living in guardianship as “simply” living with their grandparents rather than understanding that many were “formerly in care”, (2017, p. 20). The DfE (Citation2018) statutory guidance places a duty on local authorities (LA) with an emphasis on designated teachers (DTs) to develop policy and procedures which support this group of children in schools, particularly those with a pre-placement care experience.

There is an increasing body of research which identifies the potential impact of abuse on child development in predicting lifelong outcomes (Moullin et al., Citation2014; Teicher & Samson, Citation2016). Typically, schools meet the needs of children who have experienced abuse by providing individual interventions underpinned by attachment theory (Bomber, Citation2007; Brooks, Citation2019; Geddes, Citation2006). Smith et al. (Citation2017) contest the sole use of attachment theory in supporting these children, with concern that it may contribute to the “biologisation of how we bring up children to the detriment of sociocultural perspectives” (Abstract). They propose a shift towards complementary ideas which encompass social, political, and community contexts. This concurs with Sroufe (Citation2016) in calling for a more nuanced understanding of the transactional nature of “the many critical influences on development” (Sroufe, Citation2016, p. 1003) and identity formation. Sroufe proposes that it is necessary to view psychological development through an organisational, non-linear lens which includes the emergence of self and personality (Citation2005, p. 351), rather than solely focusing on early relational history. This more transactional understanding of development is congruent with the use of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological framework (Citation1999) and broader psychological concepts, such as school belonging (SB) where focus moves beyond the individual and their school relationships to the way an individual interacts within the wider community environment and the system around them.

School belonging (SB)

Allen et al. (Citation2016) provide a context-related definition of school belonging (SB) and propose that it “is a student’s sense of affiliation to his or her school, influenced by individual, relational and organisational factors inside a broader school community and within a political, cultural and geographical landscape unique to each school setting” (p. 98). SB is a concept which features as an important factor in identity formation, psychosocial adjustment, and transition to adulthood; its development can involve an individual, relational, whole school (Waters et al., Citation2010) and community approach providing a functional concept for school interventions and strategies (Allen & Kern, Citation2020).

Empirical research indicates that pupils’ SB is associated with many long lasting, important psychological benefits related to school life, such as: identity, relationships, agency, and security (Ibrihim & Zaatari, Citation2020; A. R. McMahon et al., Citation2007; Riley, Citation2019); learning, motivation, and engagement (Becker & Luthar, Citation2003; Combs, Citation1982; Osterman, Citation2000); enhanced academic achievement, and psychosocial well-being for students with disabilities (S. D. McMahon et al., Citation2008); and higher end of year grades, and higher student expectations for success and value of school work (Freeman et al., Citation2007). Strong feelings of SB also correlate with positive self-esteem (Ma, Citation2003). Conversely, reduced SB has been associated with lower academic success (L. Anderman, Citation2003; Korpershoek et al., Citation2019) with a predictive link between SB and future mental health problems (Shochet et al., Citation2006). Research indicates that young people who experience a low SB are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, antisocial behaviour, and early sexual activity (McNeely et al., Citation2002; Resnick et al., Citation1993).

Aims of the current research and research questions

This research aims to develop an understanding of the educational experiences of young people living in special guardianship from their perspective, their guardian’s, and their designated teacher’s. It seeks to illuminate the views and amplify the voice of guardianship families by raising awareness of them and of the role schools play in their lives. This will potentially enable others to understand and meet their needs by offering insight into how to improve their sense of school belonging (SB) to promote more positive outcomes.

The research questions are:

How do young people living in special guardianship understand and experience SB?

How do guardians understand and experience SB for their children?

How do designated teachers understand and experience the SB of children living in special guardianship?

Methodology

This research reflects an interpretive philosophical view, with an emphasis on the ontological belief that reality is multiple (Hudson & Ozanne, Citation1988). Epistemological assumptions are that access to multiple socially constructed realities is “only through social constructions such as language, consciousness, shared meanings and instruments” (Moran, Citation2007; Myers, Citation2008, p. 38; Young & Collin, Citation2004). The design involves a qualitative, exploratory, multiple case study approach. Seven cases embed three units of analysis (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994; Yin, Citation2018): young person, guardian, designated teacher. The context is the educational experience within which SB is constructed. The intention of this study is to gain insight by reflecting on the details of each case study, enabling naturalistic generalisation (Hammersley et al., Citation2000) to be formed.

Ethical consent was gained from the host university ethics committee.

Participants

Each participant attended a different school in one local authority (LA) in England. Participant group size was justified by the case study design (Arthur et al., Citation2012). The inclusion criteria were: families with a SGO, young people on roll at a school, aged between 10 and 16, consent from guardians, young person and DT.

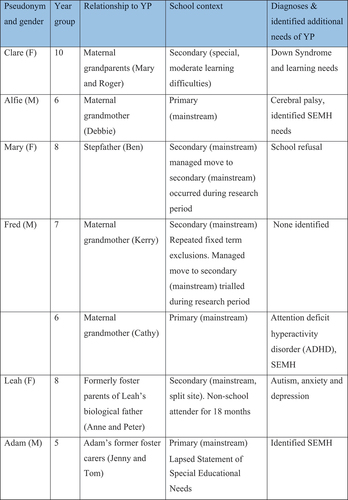

Participants were recruited through the LA’s SG team, who raised the research as an agenda item during their monthly drop-in meetings. Interested guardians were given information letters and asked to email one of the team if they wanted to participate. Each expression of interest was followed up directly by email with the information letter and consent forms, and a follow-up phone call was made days later. Once verbal consent had been gained by the guardian over the phone, the corresponding school’s DT was sent an email explaining why they had been contacted, with an attached information letter and DT consent form. Should any one of the three participants in each case not give written consent or assent, then none of the three interviews were carried out. In five of the cases, the DT was also the SENCo. In Leah’s case the SENCo was interviewed because the DT suggested that her knowledge of the young person was better. Young people and guardians were allocated pseudonyms (). DTs were referred to using their role in school.

Data collection

All interviews were carried out in-person in schools except Leah’s whose family asked to be interviewed at home. Average interview time was 60 min. Interview themes were deductively and inductively developed, refined from extant SB studies, with opportunities to speak freely. Personal construct techniques were used to identify and gather the young person’s constructs of SB (Ravenette, Citation1999; Shier, Citation2001). Each young person was asked to “draw a picture of a time when you felt like you have belonged” and “draw a picture of a time when you felt like you have not belonged” and to identify their feelings of SB related to these two pictures. Pyramiding questions were used to elicit and reveal the subjective meaning of their concept of SB.

Data analysis

Case data were analysed individually followed by a cross case analysis, using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis (TA) (2006; 2021). TA generated superordinate and subthemes. TA flexibly aligns with many epistemological perspectives including social constructionism, with the researcher’s role in knowledge production as central (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2013, Citation2021), integrating their personal and theoretical assumptions (Ide & Beddoe, Citation2023).

Findings

The individual cases provided particularistic, descriptive information about the SB experiences of young people aged between 10–16-years old, living in guardianship, and the views of their guardians and their school’s DT. Each case is presented below with the thematic map.

Clare: Fig 1.0 themes

Protection and autonomy

Clare and the DT highlighted safety as a feature of belonging. “people that belong to me are safe. It feels happy, good. Different places I’m safe at, I’m safe with my family, at school, at (club for children with SEND). Yes”. (Clare)

Identity

Clare raised her physical appearance as something she seeks help with from adults in school, “Sometimes I see them and talk about my body image.”

School support and understanding of SG

Clare identified receiving help as important, “I get different support people. They help me do a lot of things”. Clare has always received a high level of support for her learning needs. She identified her relationship with the TA as a contributory factor to SB (). Mary expressed ambivalence, recognising that TA support helped Clare to manage the demands of a mainstream primary school, but it could sometimes interfere with her parenting of Clare.

Choice of school

When asked why she feels she belongs to the school, Clare said that it was because others chose it for her. The special school is described by the DT and Mary as “protective” which seems to be an important factor in helping the children belong there, “They are in a sort of bubble here; they are very protected … they have a place that they feel safe, they have friends, adults they can talk to who will listen, they feel like they fit in here”, (DT).

Relationships and connection

Adapting to family changes

Clare’s family dynamic and structure may present an obstacle to her SB, which is in contrast to Mary’s perception of the family role. Clare’s family featured repeatedly in her interview including her worry about her care in the future, I can’t say it to you because it will make you sad but if my nan and grandad passed away I’d have to stay with my mum or auntie or uncle…I have it in my head…I just try to think time has to move on. I have to move on too. My great grandad passed away from cancer. I can’t really cope on my own because I’m too young , (Clare).

Quality of relationships

The DT explained that staff/pupil relationships are positive because teachers have received training in attachment, “all the TAs and teachers know the children very well. All the teachers are PACE (playful, acceptance, curiosity, empathy) trained. Most of our TAs too”, (DT). The school has a high pupil:staff ratio and Clare said that the teachers help her to feel happy though she could not name a specific adult, “they’re the same and I can’t really say…all the teachers”, (Clare). Clare’s feelings of SB have been affected both by her losing her primary school friendships and not having developed relationships in secondary school, ‘I want someone there for me but it’s not really there yet…sometimes I’m a bit lonely in myself. But I’m fine “cos my cousin stays with me … but in a different class. I see her but sometimes she wants her own time. I know her name. She’s younger than me”. Clare said, “I can’t remember friends but I had a lot of friends in my old school and in (club for children with SEND).” Mary and Roger concur that Clare has not developed strong friendships in school which has led to her feeling lonely at times.

Communication

The DT identified the limited number of children and their communication skills as problematic. In response, the school runs activities to encourage friendships and will “do friendship or girls groups if we notice that there is a need”, (DT). Clare is aware of the difficulties others have in understanding what she says, which has an impact on her relationships.

Community

The DT acknowledged what losing a school community can mean for children who attend a special school, “They see their peers that they were in school with go to the local high school and stay friends and then they don’t, so I think it impacts upon them,” (DT). In addition, there are often no “close community friendships” because the school might not be located near the child’s home.

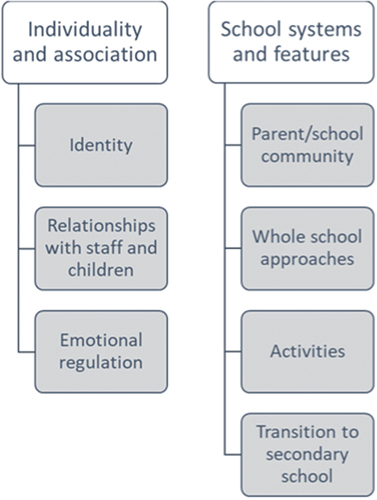

Alfie: Fig 2.0 themes

Individuality and association

Identity

Alfie’s surname has changed over time and is different between contexts, which introduces self-doubt and confusion regarding his association with a school teacher who shares the same name. Recently, Alfie asked Debbie if he is that teacher’s son.

Relationships with staff and children

Alfie identified school belonging as “10” (the highest), “everyone’s nice here, it would make them want to belong”. Alfie’s comments about his SB are incongruent with Debbie’s, who accepts that a strong relationship with staff has strengthened his feeling of belonging, but harbours concern that Alfie is over reliant on adults and has only low quality, unenduring peer relationships.

I do feel that even though he doesn’t say that he doesn’t feel like he belongs, little snippets of things tell you that he doesn’t, and it worries me.I just want him to feel like he is important to other children, (Debbie).

Emotional regulation

The DT’s construct of SB involves feeling safe enough to express a wide range of emotions. Debbie explained SB occurs when you are happy where you are, which is not the case for Alfie. The DT and Debbie reported that Alfie can exhibit unsafe responses, “Alfie will go off and he will scratch himself and say he’s going to kill himself and go through what he is going to do, he’s going to knife himself”, (Debbie).

School systems and features

Parent/school community

Debbie commented about the different family types within the school community, “Surprisingly, there are a lot of children in the same position, living with grandparents, and so when I come to pick Alfie up there are probably as many nannies picking their children up as parents,” (Debbie). The DT mentioned strong communication through school/community activities.

Whole school approaches

The DT spoke about “being inclusive” but nothing explicitly to develop SB, “an inclusive school, quality first teaching but I can’t think of anything specific”, (DT).

Activities

School prioritises activities to promote the physical and mental health of the children within the wider school community, but Debbie’s comments about Alfie’s difficulty in developing friendships, suggest that this approach to building a school community does not meet Alfie’s needs. Consequently, Debbie is seeking help beyond the school community, “I’m going to start taking him to a club on a Tuesday, I haven’t told him yet…It’s for children that have all types of difficulties”.

Transition to secondary

Alfie’s receiving school is planning transition meetings and extra sessions, but Debbie has concerns, “trying to get him into the group is difficult because sometimes he just won’t even walk in through the door”. Alfie comments about his secondary transition and raises bullying concerns, but trusts staff to keep him safe.

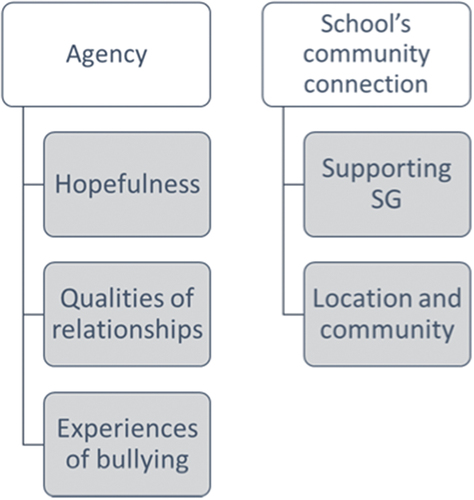

Mary: Fig 3.0 themes

Agency

Hopefulness

Ben’s hopefulness and lack of agency presents a risk to Mary’s belonging, he has not visited nor communicated Mary’s needs to staff at her new school, “today is the first time we phoned anyone, and they seemed really lovely”, (Ben). He is hopeful that Mary’s learning and social interactions will improve, which might lead to stronger SB.

Qualities of relationship

Mary rated her feeling of SB in her new, current school “9”, because others show “support, kindness and listen”, indicating a virtuous cycle, whereby if staff encourage you to speak more, others listen, “you feel like you’re involved”, (Mary).

Experiences of bullying

Ben described Mary’s enduring bullying experiences in her first secondary school, which impacted Mary’s friendships.

School’s community connection

Supporting Special Guardianship (SG)

Ben asked staff at the first secondary school to help Mary to develop her friendships because of her primary school experiences, but nothing happened. The DT suggested that the school system for identifying and helping children who live in guardianship is less robust than it is for adopted children or those in care, ‘We are clear when people are in care but not so much SG … We do ask about adoption but actually not having seen the letter recently I don’t know if there is guardianship on there’ (DT). The DT also described an invitation-only club which would develop young people’s belonging, but Mary was not one of those invited.

Location and community

The DT considers the current school to be closely linked with the local community “I think it is a lovely community and it is a very inclusive school”. Had Mary’s community relationships been more positive, the close home/current school proximity may have supported her SB.

Fred:Fig 4.0 themes

Connection with others

Self-image

Fred describes himself negatively and relies on observable characteristics: clothing, who he is seen with, and his hairstyle, “shoes and uniform. I don’t get why we have to wear it…it’s itchy as well, the shirts”.

Extracurricular activities

Fred associates playing football with SB, “When I lived with my mum, I used to play it a lot, with one of my mates. I can’t remember his name now because I moved”.

“Inside I’m hurting” (Bomber, Citation2007)

Kerry shared Fred’s neglectful experiences with primary school staff and was pleased with their response, “They knew about our situation, so he did have help and they were really good”, (Kerry). Kerry has not shared this information with the secondary school staff. Kerry told staff Fred self-harms, “he cut himself and had to have 5 stitches”, (Kerry) and staff response has been to tell Fred to ask a teacher for help. This assumes that Fred is able both to recognise his feelings and trusts the teachers to ask for help.

Systems as obstacles

Consequences of sanctions

A rigid behaviour management policy involves isolating children for 24 hours for misdemeanours. Fred is confused about why the repeated sanctions do not help him:

Fred: They try to make me have a better education I guess by punishing me with isolation but it doesn’t do anything.

Me: You think that by punishing you they are trying to help your education?

Fred: Yeah. So you don’t keep getting isolation, but I get isolation a lot.

Isolation is detrimental to Fred’s friendships, “I don’t really hang around with many people because of isolation”, (Fred). Fred describes how people who spend time in isolation might feel, “They might feel lonely, sad…maybe depressed”, (Fred).

Communication

Home/school communication relies upon text or email. Kerry and the DT find this unhelpful, “I’ll get a text…it will say your child won’t be home until 4.05 today because they’re in isolation and it doesn’t give me a reason”, (Kerry).

What is a special educational need (SEN)?

Fred is not on the SEN register, his behaviour needs are met by the behaviour management system. The DT identifies the lack of criteria around the category of SEMH as problematic, “That category of need [social, emotional and mental health. (SEMH)] is the hardest, it’s the biggest need within the school but I think we don’t know how to manage and identify it…If we’re not doing something that is ‘additional to and different from’, they shouldn’t go on the register”, (DT).

Daisy: Fig 5.0 themes

Identity

Appearance

Daisy’s self-image is a strong feature of her SB and includes how she looks, her behaviour associated with ADHD, intelligence and self-belief. Together these factors lead to her feeling different to other children and have reduced her feelings of belonging.

Achievement and ability

Daisy’s art ability enables her to explore her appearance, strengthen her friendships and build her self-esteem, strengthening her SB.

Diagnosis of ADHD

Cathy perceives the diagnosis as significant and positive “it was just like, somebody’s actually understood … and the difference it’s made in school is amazing”. In contrast, Daisy indicates that school belonging is not associated with the diagnosis, “even though I don’t fit in it’s not because of my diagnosis”. Daisy’s friendships are most important to SB, “If you’ve had friends for three years and then you have ADHD it’s not going to change them…It’s just a diagnosis”.

Fitting in

The DT and Daisy use the term “fitting in” implying a comfortable placement within a group or space, “belonging is fitting in and feeling like you’re a part of it”, (Daisy), “being part of a group, fitting in to that group and it being reciprocal”, (DT).

Friendships

Daisy’s picture of “belonging” was with friends, “I feel like I belong when I’ve got all of my friends as a support and some of my family,” (Daisy). Cathy said Daisy chose her secondary school “cos a lot of her friends are going there”, (Cathy).

Family-school connection

Previous connection can be both helpful and unhelpful. Daisy likes knowing that her biological mother went to her current school, but asked to move from her previous school because the community knew about her family, “she wanted to be somewhere where people didn’t know…to be normal” (Cathy).

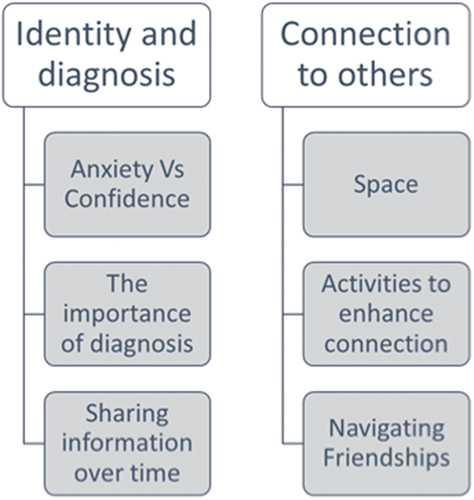

Identity and diagnosis

Anxiety versus confidence

Leah’s constructs were of “real me” and confidence, ‘the real me is not happy, they’re depressed, sad and unhappy all the time unfortunately…

confident me is fine, pretends I have no anxiety’, (Leah). Leah’s anxiety impacts negatively upon her school belonging, “my anxiety stops me from going in, so it stops me from feeling like I belong there”, (Leah).

The importance of diagnosis

Anne and the SENCo consider Leah’s school belonging to rely on an accurate identification of need, but the SENCo considers that Leah’s early relational experiences underpin her anxiety, whereas Anne thinks Leah has autism.

Sharing information over time

Anne and primary school staff also held diverging views about Leah’s needs. Leah’s Year 6 attendance was sporadic, no information was shared at transition from primary to secondary school.

Connection to others

Space

Leah and the SENCo identified physical spaces as important. Leah drew ‘the lower field where everyone sits dotted around chatting … it’s really great’.

Activities to enhance connection

The SENCo identified extracurricular clubs as promoting belonging, “our PE department is very active…surfing, kayaking, the climbing wall … we have the film club … ” (SENCo). However, all of these activities are school-based, currently inaccessible to Leah because of her 2 hour-per-week timetable.

Navigating friendships

Anne and Leah placed emphasis on social skills and friendships respectively, “she can’t do friendships”, (Anne). and “friends are a big factor of school belonging…if you don’t have any friends you can’t laugh with people…I’m most of the time just alone”, (Leah).

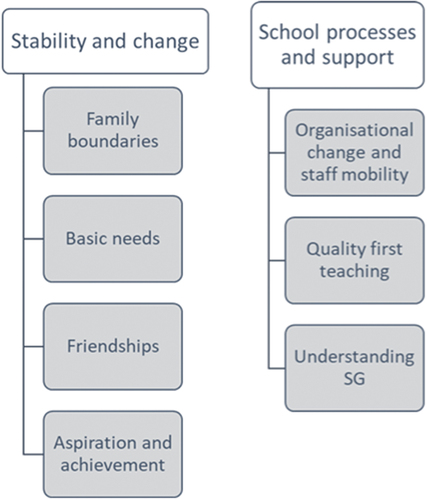

Adam: Fig 7.0 themes

Stability and change

Family boundaries

Family featured heavily in Adam and Jenny’s definitions of belonging. Jenny associated it with stability, providing comfort and safety, but suggested that this is not the case for Adam, I just think that a sense of belonging is just a sense of “this is what it is” isn’t it…I don’t think he has that sense of it will all turn out okay in the end…I don’t think he has that at all’, (Jenny).

Basic needs

Adam’s accounts included his basic needs, e.g. he drew his house and spoke about the availability of food at school.

Friendships

Adam has a large group of friends who visit and stay at his house. Through friendships and positive shared experiences Adam develops his understanding of non-SG families.

Aspiration and achievement

Jenny’s biological daughters’ experiences provide a template for Adam to belong within school and the wider community, “he went to Beavers and Cubs, and our 19-year-old, who has just gone off to university, went to Scouts and Explorers so he can see that this is what he will be doing”,

School processes and support

Organisational change and staff mobility

The school has experienced significant organisational change, and high levels of staff mobility, which has had an impact on the DT’s and pupils’ feelings of belonging, “No one goes to the staff room… It feeds into the children and I’ll be honest that I didn’t really feel a sense of belonging in this school until this last term”, (DT).

Quality first teaching

The DT explained that quality first teaching enables Adam’s needs to be met and described an example, “When we have mother’s or father’s day teachers are mindful of those children who might struggle with that, we ask, ‘is there anyone that you might want to make it (a card) for?’ just to make sure that it is inclusive”. (DT). Jenny thinks that this is insufficient.

Understanding SG

The DT did not accurately understand the breadth of her statutory role, nor processes of identification, information sharing and review. Jenny and the DT described staff’s inconsistent approach to meeting Adam’s needs, ‘a lot of the staff aren’t very big on our nurture provision, they don’t really see the point of it, it’s very much “they need to just listen, be in class”, (DT).

Discussion

RQ1: How do young people living in special guardianship (SG) understand and experience school belonging (SB)?

The young people interviewed provided rich data relevant to the question. The personal construct psychology techniques used in the young people’s interviews meant that their responses were unprompted, except for the use of “belonging” and “SB”. A key factor pertinent to SB was their individual characteristics but the single most important feature of SB was their peer relationships. All of the young people spoke of them; where relationships were positive, friendships were developed by bridging the home-school-community contexts with shared activities, such as sleepovers or club attendance. Friendships were strengthened in relation to the young person’s self-perception of a curriculum strength. Weaker peer relationships involving negative experiences were a source of anxiety, particularly for young people in secondary school who reported diminished SB, leaving them feeling isolated, resulting in some leaving or wanting to change school. These findings reflect Goodenow and Grady’s (Citation1993) definition of SB; “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others in the school environment” (p. 80). They are also consistent with extant literature about young people and their peer relationships (Bower et al., Citation2015; Craggs & Kelly, Citation2018; Gowing, Citation2019; Midgen et al., Citation2019; Murray-Harvey & Slee, Citation2007; Woolley et al., Citation2009).

In the current study, strong adult relationships sometimes enabled SB, which is in line with Midgen et al. (Citation2019) and the Department for Education (Citation2018). There seemed to be a distinction between primary, special, and secondary mainstream school contexts, with those who received higher levels of adult support including it as important to school belonging (Clare, Daisy, Adam). Mainstream secondary school pupils did not mention staff influence, focusing instead on their peer relationships. This finding reflects the conclusions of Gorard and See (Citation2011) who found that of 3,000 secondary school pupils, having friends was pivotal to their enjoyment of school.

Across the cases, the quality of the young people’s relationships with peers was often raised, with descriptions of intense, “all or nothing” relationships, suggesting that although reliable peer relationships were sought, they were often transient, and all young people had either experienced difficulties or were worried about how to maintain positive relationships with their peers over time. In response to these relational experiences, the young people either looked to their own or others’ personal characteristics, for example, their appearance, their behaviour, their identity (“real me” and “fake friends”). In most cases, their behaviour indicated difficulties in emotional regulation, for example, self-harming or running out of class. None of the pupils raised their own early experiences as an explanation of why things might go wrong, which might be associated with their developmental stage or perhaps their locus of control (Lefcourt, Citation1976).

These findings challenge those of Aldgate and McIntosh (Citation2006) who interviewed 30 SG children and concluded that their lives were “positive and ordinary”. They validate the large body of literature acknowledging the importance of early-life relationships and the possible long-term impact of a neglectful early life as a template to the young person’s subsequent relationships (Bowlby, Citation1973; Kim & Cicchetti, Citation2010). They also extend the work of J. Selwyn et al. (Citation2014) and Wade et al. (Citation2014), by suggesting that features of some guardianship families might exacerbate the young person’s emotional, behavioural and communication needs which in turn may lead them to feel different and distanced from their peers, further influencing their feelings of SB.

RQ2: How do guardians understand and experience school belonging for their children?

In concurrence with the young people’s data, the guardians also considered the young person’s peer relationships as important. In most cases they viewed the young people’s friendships less positively, expressing concern about the quantity and quality of their friendships and attributing difficulties to the young person’s social and emotional development. The guardians did not identify the young person’s developmental needs to be associated with their early life experiences, perhaps with an “implicit assumption that permanence mitigates the impact of abuse, neglect, trauma and loss” (Gore Langton, Citation2017, p.17). Instead, the difficulties in peer relationships were linked to environmental factors such as transition between schools, amount of adult support obstructing peer relationships, health conditions, and diagnoses, for example, ADHD, autism, and Down syndrome. Indeed, guardians described feeling a sense of relief at the point of diagnosis, perhaps because a diagnosis provides an explanation of why things are difficult, and a reduction of self-blame for the young person’s experiences. This finding is consistent with research involving biological parents and diagnoses (Avdi et al., Citation2000; Bloch & Weinstein, Citation2010; Rosenthal et al., Citation2001). The guardians’ understanding of the link between the emotional needs of the young people and their early life experiences might be associated with limited training to this group by the LA, which is not yet “equal to the best practice of adoption and foster care” (Harwin, Alrouh, et al., Citation2019, p. 9).

Although some guardians spoke positively about specific staff members, all expressed an overwhelming frustration about staff’s lack of understanding of the needs of the young person and of SG generally, with an inappropriate amount of support; that is, too much help may hinder the young person’s peer relationships, too little may lead to unmet emotional needs and behavioural responses. Guardians’ feelings of frustration introduced a vulnerability to the home-school relationship, and in some cases, communication completely broke down and the young person left or withdrew from the school.

Some guardians raised shared activities across school-community contexts as helpful to SB, whereas the influence of community knowledge of the SG home context was mixed; for example, helpful in providing a supportive network of other guardians, or unhelpful by perpetuating a negative family legacy. Proximity of home to school influences SB with closer schools enabling walking with peers or other family members, which was helpful; this is consistent with the work of E. M. Anderman (Citation2002). Guardians spoke about their aspirations for the young adult, but often this was couched in their concerns about events which were out of their control, for example, transition to secondary school/college, maintaining a relationship with birth family members. This is consistent with the findings of Dunne and Kettler (Citation2007) and Grandparents Plus (Citation2014).

RQ3. How do designated teachers (DTs) understand and experience the school belonging (SB) of children living in special guardianship (SG)?

None of the DTs had previously considered the concept of “SB”, though all defined it as relating to the forming and maintaining of “lasting, positive and significant interpersonal relationships” (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995, p. 497). DTs purported to promote SB through quality first teaching and whole school approaches, including factors such as school uniform, a broad curriculum supported by a range of resources, in-school extra-curricular activities and vigilance of social relationships. SB literature has identified these factors as relevant (Bower et al., Citation2015; Loukas et al., Citation2010; Rahman, Citation2013; J. Selwyn et al., Citation2014).

Sharing information within school, between home-school, and across schools during transitions was key. Information sharing could be influenced by school size, and levels of staff mobility which might lead to the loss of knowledge about the SG family over time. Some DTs spoke of feeling frustrated with health and social care services because of their lack of information sharing which was obstructive to them understanding young people’s needs. Some of them misunderstood the information sharing processes of Social Care.

None of the DTs mentioned the Department for Education (Citation2018) guidance, stipulating relevant LA and school responsibilities to SG. Most of the DTs were relatively new to the role, and some felt a stronger sense of their own belonging to the school organisation than others. Some knew more than others about the processes of SG, most of which was learned on the job and/or from colleagues doing a similar job. Comments were made about SG not being well resourced.

All DTs conveyed an understanding that young people who have experienced early maltreatment may experience emotional and social difficulties, which might impact negatively on their peer relationships and learning. This may reflect the regional training which is underpinned by attachment theory and associated work (Bowlby, Citation1973; Kim & Cicchetti, Citation2010). This focus on early relational experiences contrasts with that of the young people and their guardians, who placed importance on peer relationships. Perhaps, as Smith et al. (Citation2017) posit, this indicates a need for schools to use complementary approaches to attachment theory when considering how to understand and meet the needs of this group.

Primary school DTs provided young people with an intervention aimed at developing a relationship with a staff member who had received training in attachment theory, whereas the secondary school DT’s espoused attachment theory but in practice the emotional and social needs of the young person were sometimes met by systems, underpinned by behavioural theory; for example, a whole school reward/sanction system. Instances of a shared DT/SENCo role meant that SEND processes were understood, although most DTs were unsure about when to consider a young person’s emotional and social needs as a special educational need. This meant an inconsistent response to the young person’s needs as some were identified and met using SEND processes, for example, registered as social, emotional and mental health (SEMH; SEND CoP, 2014), (Daisy, Alfie) whilst others were not (Fred).

Problematically for some families, current statute and guidance provides more support for previously looked after children and does not extend to all SG families. Of the seven cases, four of the young people had been previously looked-after because their grandparents took responsibility for them before applying for the SGO. The onus is on DTs to ask guardians about any legal order and for evidence of previously looked-after status; without this DTs can use their discretion or communicate with the LA for guidance (Department for Education, Citation2018), but none had formal processes in place to gather this information. This study found that although DTs considered information about the young person’s early life to be important to meet their needs, some were reluctant to proactively ask for this detail and preferred instead for guardians to approach them.

Limitations

The use of self-selecting participants encourages those who have a vested interest in the research (Rosnow & Rosenthal, Citation1976). However, if young people or DTs did not consent then the family would not have participated, perhaps reducing the impact of this bias. Also, all guardians were identified at the SG team drop-in, which might suggest that they experienced challenges involving the SG. Alternative ways of accessing SG families presented challenges, for example, approaching schools directly to recruit families was an option, but they may not know who lives in SG and they may have approached families with whom they had a positive relationship which would limit the rigour of the study. The participant group was relatively small, but carefully chosen to provide highly diverse perspectives, and broad, rich data, to reflect the complexity of SB and SG. A case study approach does not aim to find generalisable findings, but to illuminate experiences of a target group; however, findings in relation to this study are likely to provide guidance and perspective to those in similar contexts.

Conclusion and implications for EP practice

This research has highlighted the need for a greater focus on the psychological needs of young people living in special guardianship in relation to their school belonging. EPs have a key role, within LAs and beyond, to encourage and support systemic and within-school changes. Many EP services have close links with virtual school teams and can promote and extend the understanding of young people in SG by providing psychological training, supervision and mentoring to designated teachers (DTs) and other staff supporting SG families in schools. Training to DTs could include an elaborate model of the intersectionality of families for whom the DTs have responsibility. Nationally, formally accredited training would encourage a consistently high standard of DT practice and support of the multiplicity and complexity of young people and their additional needs. EPs could support other professional groups to develop their understanding of SB, the needs of SG families and how to meet them. Findings from the current research might be expected to provide EPs with insight into the multiplicity of factors around school belonging, including how EPs might engage with managing possible problems, and facilitating discussion around solutions for others in similar circumstances.

Terminology, identification and support

This research highlights that clearer identification of what School Belonging (SB) means, who young people living in Special Guardianship (SG) are, and statutory support for those needing it would benefit this group of children. The wide range of terms used for SB weakens it, inhibiting conceptual progress (Podsakoff et al., Citation2016). Without a clear definition a concept can be “everywhere and nowhere” (Peterson et al., Citation2014, p. 16). In schools there is currently no widely understood use of the term or approach to develop SB despite the associated positive outcomes. EPs can promote the use of the term SB and apply the theory across all levels of their work.

SG families are not always identified by school staff. Robust processes should be implemented by all LAs and schools to enable identification and information sharing in order to ensure that guardianship families are sufficiently supported, and multiagency working can take place. EPs can train staff in how to sensitively gather and communicate information, and how to undertake a comprehensive needs analysis, where mutual priorities and interventions can be agreed with a focus on strong community links, transitions between schools, and peer relationships (Gowing, Citation2019). EPs can help staff to understand the link between SEMH and SEND in (Young & Collin, Citation2004) order to ensure timely support and intervention.

Some children living in SG have a previous care-experience; others do not. Current regulation limits the statutory responsibility of LAs to provide a higher level of support only for the former. This study proposes that children living in SG should have greater identification and support based on individual experiences and presenting, with plans for support negotiated between DTs, guardians and young people. Assumptions about early experiences should not be made but adequate resources should be accessible to all SG families. This study recommends that a review of SG policy and practice in LA and the education system is required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aldgate, J., & McIntosh, M. (2006). Looking after the family: A study of children looked after in kinship care in Scotland. Social Work Inspection Agency.

- Allen, K-A., & Kern, P. (2020). Boosting School Belonging: Practical Strategies to Help Adolescents Feel Like They Belong at School. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203729632

- Allen, K., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

- Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects of psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/00220663.94.4.795

- Anderman, L. (2003). Academic and social perceptions as predictors of change in middle school students’ sense of school belonging. The Journal of Experimental Education, 72(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970309600877

- Arthur, J., Waring, M., Coe, R., & Hedges, L. V. (Eds.). (2012). Research methods and methodologies in education. Sage.

- Ashley, C., Aziz, R., & Braun, D. (2015). Doing the right thing: A report on the experiences of kinship carers. Family Rights Group.

- Avdi, E., Griffin, C., & Brough, S. (2000). Parents’ constructions of the ‘problem’ during assessment and diagnosis of their child for an autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Health Psychology, 5(2), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530000500214

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Becker, B., & Luthar, S. (2003). Social emotional factors affecting achievement outcomes among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. Educational Psychologist, 37(4), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3704_1

- Bloch, J. S., & Weinstein, J. D. (2010). Families of young children with autism. Social Work in Mental Health, 8(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332980902932342

- Bomber, L. (2007). Inside I’m hurting: Practical strategies for supporting children with attachment difficulties in schools. Worth Publishing.

- Bower, J., Kraayenoord, C., & Carroll, A. (2015). Building school connectedness in schools: Australian teacher’s perspectives. International Journal of Educational Research, 70, 101109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.02.004

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss (volume 2). Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Broad, B., Hayes, R., & Rushforth, C. (2001). Kith and kin: Kinship care for vulnerable young people. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/kith-and-kin-kinship-carevulnerable-young-people

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1999). Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. In: S. L. Friedman, & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (pp. 3–28). American Psychological Association Press.

- Brooks, R. (2019). The trauma and attachment-aware classroom: A practical guide to supporting children who have encountered trauma and adverse childhood experiences. Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

- Children Act. (1989). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/contents

- Combs, A. (1982). Affective education or none at all. Educational Leadership, 39(7), 495–497.

- Corum, British Association for Adoption and Fostering Academy. (n.d.-a). Kinship Care. https://corambaaf.org.uk/fostering-adoption/kinship-care-and-private-fostering/kinship-care

- Corum, British Association for Adoption and Fostering Academy, (n.d.-b.). Special guardianship. https://corambaaf.org.uk/fostering-adoption/kinship-care-and-private-fostering/specialguardianship

- Craggs, H., & Kelly, C. (2018). School belonging: Listening to the voices of secondary school students who have undergone managed moves. School Psychology International, 39(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034317741936

- Department for Education. (2018). The designated teacher for looked-after and previously looked-after children: Statutory guidance on their roles and responsibilities.

- Dunne, E. G., & Kettler, L. J. (2007). Grandparents raising grandchildren in Australia: Exploring psychological health and grandparents’ experiences of providing kinship care. International Journal of Social Welfare, 17(4), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14682397.2007.00529.x

- Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. A., & Jensen, J. A. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220

- Geddes, H. (2006). Attachment in the classroom: A practical guide for schools. Worth Publishing.

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Gorard, S., & See, B. H. (2011). How can we enhance enjoyment of secondary school? The student view. British Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 671–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.488718

- Gore Langton, E. (2017). Adopted and permanently placed children in education: From rainbows to reality. Educational Psychology in Practice, 33(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2016.1217401

- Gowing, A. (2019). Peer-peer relationships: A key factor in enhancing school connectedness and belonging. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(2), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2019.36.2.64

- Grandparents Plus. (2014). Disadvantage, discrimination and resilience: The lives of kinship carers. https://www.grandparentsplus.org.uk/disadvantagediscrimination-resilience-the-lives-of-kinship-families

- Hammersley, M., Foster, P., & Gomm, R. (2000). Case study and generalisation. In: R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, & P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method: Key issues, key texts (pp. 98–115). Sage.

- Harwin, J., Alrouh, B., Golding, L., McQuarrie, T., Broadhurst, K., & Cusworth, L. (2019). The contribution of supervision orders and special guardianship to children’s lives and family justice. A summary report. Centre for Child and Family Justice Research.

- Harwin, J., & Simmonds, J. (2020). Special guardianship: Practitioner perspectives. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/special-guardianship-a-review-of-the-evidence

- Hudson, L. A., & Ozanne, J. L. (1988). Alternative ways of seeking knowledge in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(4), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/209132

- Ibrihim, A., & Zaatari, W. E. (2020). The teacher-student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(1), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1660998

- Ide, Y., & Beddoe, L. (2023). Challenging perspectives: Reflexivity as a critical approach to qualitative social work research. Qualitative Social Work, 0(0. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250231173522

- Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 51(6), 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x

- Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2019). The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

- Lefcourt, H. M. (1976). Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research. Erlbaum.

- Loukas, A., Roalson, L., & Herrera, D. (2010). School connectedness buffers the effects of negative family relations and poor effortful control on early adolescence conduct problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15327795.2009.00632.x

- Ma, X. (2003). Sense of belonging to school: Can schools make a difference? The Journal of Educational Research, 96(6), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670309596617

- McMahon, S. D., Parnes, A. L., Keys, C. B., & Viola, J. J. (2008). School belonging among low-income urban youth with disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20304

- McMahon, A. R., Reck, L., & Walker, M. (2007). Defining well-being for Indigenous children in care. Children Australia, 32(2), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1035077200011536

- McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x

- Midgen, T., Theodoratou, T., Newbury, K., & Leonard, M. (2019). ‘School for everyone’: An exploration of children and young people’s perceptions of belonging. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(2), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2019.36.2.9

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. (2nd ed.) Sage.

- Moran, M. J. (2007). Collaborative action research and project work: Promoting practices for developing collaborative inquiry among early childhood preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.008

- Moullin, S., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2014). Baby bonds: Parenting, attachment and a secure base for children. Sutton Trust.

- Murray-Harvey, R., & Slee, P. T. (2007). Supportive and stressful relationships with teachers, peers and family and their influence on student’s social/emotional and academic experience of school. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 17(2), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.17.2.126

- Myers, M. D. (2008). Qualitative research in business & management. Sage.

- Nandy, S., & Selwyn, J. (2013). Kinship care and poverty: Using census and microdata to examine the extent and nature of kinship care in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 43(8), 1649–1666. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs057

- Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003323

- Peterson, A., Lexmond, J., Hallgarten, J., & Kerr, D. (2014). Schools with soul: A new approach to spiritual, moral, social and cultural education. RSA Investigate-Ed. Action and Research Centre.

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, B. S., & Podsakoff, P. N. (2016). Recommendations for creating better concept definitions in the organisational, behavioural and social sciences. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 159–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115624965

- Rahman, K. (2013). Belonging and learning to belong in school: The implications of the hidden curriculum for indigenous students. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34(5), 660–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.728362

- Ravenette, T. (1999). Personal Construct Theory in Educational Psychology: A Practitioner’s View. In In A Drawing and its Opposite - an Application of The notion of The “construct” in The Elicitation of Children’ s Drawings. In Personal construct theory in educational psychology: A practitioner’s view. John Wiley and Sons.

- Resnick, M. D., Harris, L. J., & Blum, R. W. (1993). The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 29(1), S3–S9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x

- Riley, K. (2019). Agency and belonging: What transformative actions can schools take to help create a sense of place and belonging? Educational and Child Psychology, 36(4), 13. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2019.36.4.91

- Rosenthal, T. E., Biesecker, L. G., & Biesecker, B. B. (2001). Parental attitudes toward a diagnosis in children with unidentified multiple congenital anomaly syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 103(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1527

- Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (1976). The volunteer subject revisited. Australian Journal of Psychology, 28(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049537608255268

- Selwyn, J. T., Farmer, E., Meakings, S. J., & Vaisey, P. (2013). The poor relations? Children and informal kinship carers speak out: A summary research report. School for Policy Studies: University of Bristol

- Selwyn, J., Wijedasa, D., & Meakings, S. J. (2014). Beyond the adoption order: Challenges, interventions and adoption disruption. Department for Education.

- Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children and Society, 15(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.617

- Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1

- Simmonds, J. (2011). The role of special guardianship: Best practice in permanency planning for children (England and Wales). British Association for Adoption and Fostering.

- Smith, M., Cameron, C., & Reimer, D. (2017). From attachment to recognition for children in care. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(6), 1606–1623. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx096

- Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

- Sroufe, L. A. (2016). The place of attachment in development. In: J. Cassidy, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment 3rd ed., pp. 997–1011. The Guildford Press.

- Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2016). Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 57(3), 241266. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12507

- Wade, J., Sinclair, I., Stuttard, L., & Simmonds, J. (2014). Investigating special guardianship: Experiences, challenges and outcomes. Department for Education.

- Waters, S. K., Cross, D., & Shaw, T. (2010). How important are school and interpersonal student characteristics in determining later adolescent school connectedness, by school sector? Australian Journal of Education, 54(2), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494411005400207

- Welland, S., Meakings, S., Farmer, E., & Hunt, J. (2017). Growing up in kinship care: Experiences as adolescents and outcomes in young adulthood. Grandparents Plus. https://www.grandparentsplus.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2020/02/GUIKC_Full_Report_FINAL.pdf

- Woolley, M. E., Kol, K. L., & Bowen, G. L. (2009). The social context of school success for latino middle school students: Direct and indirect influences of teachers, family and friends. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(1), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608324478

- Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. (6th ed). Sage.

- Young, R., & Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 64(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.12.005