ABSTRACT

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the factors contributing to NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) status among youth. We identify 43 studies that meet our inclusion criteria in Scopus, PsycINFO, ERIC, British Education Index, Social Science Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Index, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, and ScienceDirect, covering the period from 2010 to October 2023. We find significant associations between NEET status and various demographic, familial, educational, socio-economic, and health-related factors. Gender-specific disparities and evolving trends within distinct demographic cohorts are revealed. Our findings highlight that NEET is associated with a higher suicide risk (OR = 2.8, 1.8–3.8), criminal behaviour (OR = 2.06, 1.47–2.65), and unemployment experience (OR = 1.98, 0.72–3.25), while higher education levels (OR = 0.81, 0.67–0.95) act as a protective factor. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive interventions tailored to the challenges faced by NEET youth. Future research should explore these relationships further to inform policy and practice effectively.

Introduction

There has been increasing concern over the rising number of young people not in employment, education, or training (NEET). NEET status has been found to have negative consequences for individuals, communities, and societies, such as lower well-being, increased social exclusion, and reduced economic growth (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023).

NEET is a global issue affecting young people between the ages of 15 and 24 everywhere. Being a NEET youth can have long-term consequences on health, education, and employment prospects (Thompson, Citation2011). Many stakeholders, including policymakers, researchers, and educators, have emphasized the importance of the NEET phenomenon because it poses significant challenges to the socio-economic development of nations. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of NEET youth has increased (Aina et al., Citation2021). According to a recent study by the International Labour Organization (ILO), the global youth NEET rate showed a 1.5% point increase between 2019 and 2020, reaching its highest level in at least 15 years (ILO, Citation2021).

Current study

Research and policy efforts have mostly focused on understanding the risk factors associated with NEET status among youth (Paabort et al., Citation2023). The transition of NEET youth into productive and fulfilling life paths is challenging and impeded by various barriers. Globally, NEET status has emerged as a rising concern, with prevalence rates from 6 to 30% across OECD countries (Kevelson et al., Citation2020). The majority of NEET youth come from disadvantaged backgrounds and are vulnerable to adversities like poverty, low academic achievement, health issues, and lack of social support, even before they leave education (Filia et al., Citation2023; Matli & Ngoepe, Citation2021; Pitkänen et al., Citation2021).

Diverse individual, family, and societal factors have been associated with an increased risk of NEET status in youth. However, existing evidence on this subject is marked by heterogeneity and uncertainty regarding the comparative strength of different factors or the potential presence of moderating effects (Alfieri et al., Citation2015; Dickens & Marx, Citation2020; Quintano et al., Citation2018). Research on this topic has been fragmented across disciplines, populations, and study designs underscore the need to move beyond an exclusive focus on specific issues, such as improving mental health or reducing school dropout rates. A meta-analysis and systematic review provides a more comprehensive overview of NEET risk factors, synthesizes the literature, reduces heterogeneity in findings, and facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of risk factors across multiple contexts (Cragg et al., Citation2019).

Identifying the factors influencing youth NEET outcomes is crucial to develop effective policy and intervention measures. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of studies published from 2010 onwards examining predictors of NEET status among youth. In the meta-analysis, the evidence can be consolidated across studies, allowing more definitive conclusions about the role of key risk factors and identifying remaining gaps that require further investigation (Gholizadeh & Mohammadkazemi, Citation2022). It is important to effectively address barriers faced by at-risk youth in education and employment; it is imperative to consider comprehensive solutions that account for the complex interactions among risk factors across different domains.

Prior research on NEET youth has investigated various risk factors and individual characteristics. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of risk factors for NEET youth have focused narrowly on a limited number of dimensions, such as psychosocial well-being or mental health, rather than taking a holistic perspective. For example, Tayfur et al. (Citation2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the relationship between psychosocial factors and education and employment outcomes. The study highlighted associations between adolescent behavioural problems, substance abuse, peer problems, prosocial skills, self-reflection, aspirations, and physical activity with education and employment outcomes in young adulthood, often accompanied by common mental health problems. Gariépy et al. (Citation2021) investigated the association between the mental health status of NEETs and problems like mood, anxiety, behaviour disorders, and substance abuse. They found that young people with mental health issues are more likely to become NEETs than those without mental health problems.

Similarly, Li and Wong (Citation2015) examined the role of psychosocial factors in shaping young adults’ educational and occupational outcomes. Their systematic review provided valuable insights into the significance of adolescents’ psychosocial well-being and skill development for a successful transition to adulthood.

Interventions for NEET youth have also been evaluated in various studies. Lindhardt et al. (Citation2022) found that there was robust evidence on the effects of training interventions, such as career guidance and counselling, vocational education and training and entrepreneurship education. Conversely, information services and decent work policies had less supporting evidence. Certain demographic groups, such as older youth, ethnic minorities, and individuals with criminal records, were understudied.

While previous systematic reviews, like that of Mawn et al. (Citation2017), have made significant progress, their scope has often remained narrow, focusing exclusively on employment, health, earnings, welfare receipts, and education. This study emphasizes the need for targeted efforts to assist jobless individuals in securing gainful employment, along with the crucial role of psychosocial interventions in improving NEET youth outcomes. Another perspective is offered by Escudero and López Mourelo (Citation2017), who examined the implementation of Youth Guarantee plans across the European Union. The Youth Guarantee plan is a commitment by all EU member states to ensure that all young people under the age of 30 receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship, or traineeship within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education. This initiative aims to reduce youth unemployment and inactivity by keeping young people in touch with the labour market or ensuring further education. They concluded that better outcomes could be achieved by considering key success factors such as clear eligibility criteria, timely response, appropriate resources, and compliance mechanisms.

The risk factors associated with NEET youth are complex and interconnected. Poverty, for instance, can perpetuate the cycle of disadvantage as both a cause and a consequence of NEET youth (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Ruesga-Benito et al., Citation2018). Social and familial factors can exacerbate the situation, thus highlighting the need for a thorough understanding of the underlying causes and consequences of NEET youth (Apunyo et al., Citation2022). A multi-sectoral approach is necessary to address both individual and structural factors to address this issue effectively. Despite the existing evidence, more research is needed to identify and comprehend the root causes of NEET status. This systematic literature review seeks to shed light on the risk factors associated with NEET youth. The primary objective is to deepen our understanding of the factors contributing to the incidence of NEET status among young individuals.

Data and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis conforms to the guidelines set in 2020 by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Page et al., Citation2021). To identify and extract relevant information from primary studies concerning the impact of risk factors on NEET youth, we adopted a systematic approach involving several sequential steps. As a first step, we conduct an extensive literature search in order to identify potential publications. After screening these publications, we shortlist those that are eligible. The relevant information such as authors, title, paper source, publication year, country, sample size, odds ratio, effect size, and correlation coefficients are extracted from the selected publications. A quality assessment is then conducted in the subsequent step. Finally, we perform statistical analyses to synthesize the evidence and draw conclusions about the impact of risk factors on NEET youth.

Research strategy and selection criteria

The review was conducted through a systematic search of English-language publications published from 2010 to October 2023. We limited our search to papers published since 2010, to include the most recent and relevant studies and because academic research has become increasingly focused on NEET-related issues due to the effects of the global recession on education and employment. Two independent reviewers carried out the search in the following electronic databases: Scopus, PsycINFO, ERIC, British Education Index, Social Science Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Index, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, and ScienceDirect. In addition, we searched grey literature collections such as GLADNET and used Google Scholar as a supplementary source. Each article acquired during the retrieval process was then inputted into Litmaps 2023 (litmaps.com) for manual examination of any newly published articles until October 2023, therefore ensuring a thorough and complete review of the existing literature. This approach helped to identify additional studies that met the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis.

To identify relevant studies for our meta-analysis on risk factors of being NEET youth, we used the search terms in :

Table 1. Search terms used for this systematic and meta-analysis article.

The sample for this study comprised individuals between the ages of 15 and 24 who were categorized as NEET, meaning they were not engaged in employment, education, or training. The rationale for the age range of 15 to 24 was the definition of NEET by the International Labour Organization (ILO, Citation2017). However, we acknowledge that there may be a need to increase the upper age, such as to 29, due to the increase in years of education (Boissonneault et al., Citation2020). Including studies with a wider age range ensured the review was as comprehensive as possible. Consequently, the analysis encompassed studies that involved individuals between the ages of 12 and 35 and those that provided subgroup analyses specifically for NEET participants within the overall population across different countries.

Our review focused on risk factors and determinants that may contribute to NEET status. The review included any risk factor and other behaviours that could be used to identify someone as NEET, as well as an assessment of the impact of single and multiple risk factors on NEET status. Various study designs were considered, including controlled trials, case-control studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, observational studies and case reports about risk factors affecting NEET.

Screening and eligibility criteria

The bibliographic references in this study were organized and managed using EndNote X9.0 software. Duplicate references were identified and excluded from the references. After removing duplicate records, we conducted a preliminary screening by reviewing title and abstract. We specifically focused on identifying publications that investigated the risk factors and characteristics associated with NEET.

To ensure the reliability of our inclusion/exclusion criteria, we conducted a double screening of 40% of all eligible full texts. The open-source artificial intelligence programme ASReview was used for priority screening to verify screening results (ASReview version 1.2.1, available at https://asreview.nl/). This additional screening step is a crucial component of our methodology. It ensures that our inclusion/exclusion criteria are applied consistently and accurately, enhancing our study findings’ validity and reliability.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted the following information from each article: authors, year of publication, study location, sample size, main study objective, study design (including the study population, survey type, and year of data collection), targeted risk factors, methodological approach used in data analysis, and outcomes (including outcome measures). In the present meta-analysis, antecedents and consequences with less than three studies were excluded. The accuracy of the extracted or calculated data was confirmed by comparing the collection forms of the two investigators.

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the included cross-sectional studies using a modified version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2.0. This tool assesses the quality of studies using criteria similar to the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-Randomized Studies (RoBANS). The RoBANS tool assesses bias risk across five domains: participant selection, control of confounding variables, measurement of risk factors or exposures, blinding of outcome assessment, and handling incomplete outcome data. The criteria include: 1) Is there a clear statement of the study objectives and their relevance to the NEET phenomenon? 2) Are the data collection methods explicitly described and designed to minimize bias? 3) Is there a clear description of the methodological approach used in data analysis, and does it align with the study design and research question? 4) Does the study comprehensively examine and justify the targeted risk factors for NEET youth? 5) Are the outcome measures explicitly defined, validated, reliable, and consistently implemented across all study participants?

We also utilized artificial intelligence (Evidence Prime, Hamilton, ON, Canada) to cross-check screening results. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two authors, and any remaining disagreements were resolved by a third author. The total quality score ranged from 0 to 5; studies scoring 4–5 points were considered to have a low risk of bias, those with a score of 2–3 points were regarded as having a moderate risk of bias, and studies assessed with < 2 points were considered to have a high risk of bias.

Data synthesis and analysis

We conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis by pooling odds ratios (ORs), depending on data availability from observational studies. We performed random effect meta-regressions to combine findings from various studies quantitatively. The fixed-effects methodology was used to synthesis the findings of studies that presented multiple independent effect sizes. We used robust variance estimation (RVE) in our random-effects models to do this. This allowed us to investigate the relationships between NEET status and our overarching categories.

RVE offers the advantage of aggregating estimates that might be correlated due to coming from the same groups of participants. Importantly, this method enabled us to incorporate all relevant measures for these categories without specifying their covariance structures explicitly.

Furthermore, our analyses were enhanced with a small-sample correction. This correction is necessary when conducting hypothesis testing using RVE, particularly with smaller sample sizes. For accurate results when using RVE for hypothesis testing, the degrees of freedom must be greater than or equal to four. With fewer than four degrees of freedom, the assumptions underlying the t-distribution approximation, upon which the testing is based, no longer hold. This can lead to a greater likelihood of type I2 errors than indicated by the p-values used for testing.

The I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test assessed statistical heterogeneity. Given that between-study heterogeneity can be misleading when quantified by I2 during a meta-analysis of observational studies. Furthermore, we conducted subgroup analyses and used Jamovi version 2.4.11.0 for data analyses.

Results

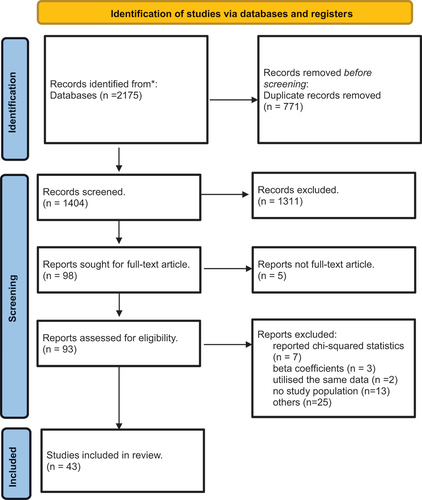

In our initial search we found 2,175 publications. Following de-duplication and screening, 1404 publications were further screened. Then, 1311 articles were excluded by the titles and abstracts, and the remaining 56 articles were removed for different reasons; seven of the studies reported chi-squared statistics, three of them reported beta coefficients from linear regressions, and the rest of them did not report study population or other essential data for odds ratio and Cls. Furthermore, two studies utilized the same data to obtain the same estimations. When we removed low-quality research, the results remained identical. The meta-analysis includes the final 43 publications. shows a PRISMA diagram of the study retrieval procedure.

Study characteristics

The review encompassed studies totalling 1,001,701 unique individuals conducted in various countries. These countries included the United Kingdom (8 studies), Canada (4 studies), Spain (3 studies, all based on the same sample), Norway (3 studies), Australia (3 studies), Finland (3 studies), and 19 studies each from Austria, Mexico, Ireland, Switzerland, Italy and Greece. Methodologically, the studies exhibited a diverse range of designs. The majority of studies adopted a cohort study design (24 studies), followed by cross-sectional (18 studies) and case-control (1 study) designs. Quality assessments were conducted, with study quality ratings ranging from low to high across the studies. Study quality was low in nine studies, moderate in 19 studies, and high in 15 studies.

The median age of participants across studies was 19 years old, ranging from 15.93 to 23.67 years. Gender distribution was also diverse, with males comprising anywhere from 33% to 67% of the samples. in the appendix gives an overview of the included studies.

Main analysis

Due to the presence of heterogeneity both within and across studies, random-effect models were employed in order to calculate the average effect and its precision. This approach was chosen as it provides a more cautious estimation of the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The odds ratio and confidence interval for the link between risk factors and becoming NEET were computed to meta-analyse this relationship. Subgroup analysis was conducted using gender and age categories 15–18 and 18–24 and youth ≥ 25 as moderators to explain the variation in the outcome variable. The absence of control variable information in many studies restricted our ability to conduct comprehensive subgroup analyses based on potential confounders.

Demographic factors

Twenty studies investigated the associations between demographic factors and being NEET. The aforementioned studies were conducted using large cohorts, ensuring that the samples were representative of the entire population. Moreover, the studies exhibited a moderate to high level of quality, as seen in in the appendix. The results of all the research examined in this analysis consistently indicated that the specific outcome was the attainment of NEET status. A summary of the effect sizes for each study can be found in in the appendix.

shows the relationship between demographic factors and being NEET. Five studies reported the odds ratio of ethnicity (Bania et al., Citation2019; Karyda & Jenkins, Citation2018; Maraj et al., Citation2019; Schoon, Citation2014; Yang, Citation2020); the result was equal to 1.15 and CI = 0.74–1.55 (I2 = 3.64%, p < .001). In these analyses, ‘ethnicity’ refers to a different ethnic background than the main ethnic group in the sample.

Our analysis included data from seven studies examining the relationship between migrant status and NEET status (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Kevelson et al., Citation2020; Luthra & Sottie, Citation2019; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Tamesberger & Bacher, Citation2014; Yang, Citation2020). The odds ratio for this relationship was 1.07, with a 95% CI ranging from 0.89 to 1.25. A high level of heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 60%, p < .001). This suggests that the impact of migrant status on NEET outcomes varies across different populations or regions, including differences in educational and employment opportunities, social integration challenges, having difficulties understanding the language, and discrimination (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023). We examined eight studies that investigated the association between marital status and NEET status (Akinyemi & Mushunje, Citation2017; Basta et al., Citation2019; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Lee & Kim, Citation2012; Luthra & Sottie, Citation2019; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Yang, Citation2020). The odds ratio for this relationship was 1.64, with a 95% CI spanning from 0.95 to 2.33. The reference group for this variable consists of single or unmarried youth. Once again, substantial heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 78.05%, p < .001), indicating that marital status might not uniformly predict NEET status and may be influenced by various contextual factors. While ethnicity, migrant status, and marital status demonstrate associations with NEET outcomes, the context plays a vital role in shaping these relationships.

Family factors

Examining 46 studies, our investigation into family-related factors and their association with NEET status underscores their multifaceted impact on youth. Parents being unemployed or out of job and workplace is a key factor, showing a pooled odds ratio of 1.54 (95% CI: 1.17, 1.91; I2 = 45.8%) (Cabral, Citation2018; Duckworth & Schoon, Citation2012; Giret et al., Citation2020; Pitkänen et al., Citation2021; Rodriguez-Modroño, Citation2019; Schoon, Citation2014). This highlights that a jobless parent plays a substantial role in predicting NEET status but can be influenced by various contextual factors. Similarly, parents’ income emerged as an important determinant, revealing a pooled odds ratio of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.54; I2 = 49.3%) (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Lee & Kim, Citation2012; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Pitkänen et al., Citation2021; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Schoon, Citation2014; Schoon & Lyons-Amos, Citation2017; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018). It is essential to note that, in these analyses, parents’ income refers to the economic resources of parents. The reference group for this variable are youth with parents with a high and average income. The odds ratio of 1.29 suggests an association between lower parental income and NEET status when compared to the reference group of youth with high and average parental income. The education level of the parents is an important factor. This was indicated by an odds ratio of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.66, 1.09; I2 = 17.8%), as found in 10 studies (Alfieri et al., Citation2015; Bania et al., Citation2019; Karyda, Citation2020; Karyda & Jenkins, Citation2018; Kevelson et al., Citation2020; Lee & Kim, Citation2012; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Schoon, Citation2014; Su et al., Citation2022; Yang, Citation2020). The reference group for this variable includes parents with a high school degree or less. The level of parental education seems to have a significant impact on youth NEET status (Ringbom et al., 2022). It influences the educational aspirations, access to resources, and career opportunities available to them. Consequently, it shapes their trajectories beyond education (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023).

Our analysis also considered the impact of living with single parent on NEET status (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Cabral, Citation2018; Duckworth & Schoon, Citation2012; Karyda & Jenkins, Citation2018; Pitkänen et al., Citation2021; Rodriguez-Modroño, Citation2019; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Schoon, Citation2014; Selenko & Pils, Citation2019; Tamesberger & Bacher, Citation2014). The pooled odds ratio for this association was 1.03, with a 95% CI of 0.88 to 1.17. Heterogeneity was once again high (I2 = 52.9%), indicating that the effect of living with a single parent may not be uniform and could vary by region or social context. Meanwhile, the impact of the number of siblings is 1.11 (95% CI: 0.85, 1.36; I2 = 36.7%) (Giret et al., Citation2020; Schoon, Citation2014; Selenko & Pils, Citation2019), and care responsibility 1.52 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.99; I2 = 39.09%) on NEET status (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Gutierrez-Garcia et al., Citation2018; Kevelson et al., Citation2020; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Tamesberger & Bacher, Citation2014; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018). shows the relationship between family factors and being NEET.

Education and unemployment experience factors

Our analysis of 15 studies examining education and unemployment experience factors underscores their substantial role in shaping NEET status. Our analysis revealed that the level of education is a critical determinant in predicting NEET status (Alcazar et al., Citation2020; Cabral, Citation2018; Giret et al., Citation2020; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Lee & Kim, Citation2012; Lin & Chiao, Citation2022; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2022; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018; Yang, Citation2020). The pooled odds ratio for this factor was calculated to be 0.81, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 0.67 to 0.95. However, substantial heterogeneity was observed in this analysis (I2 = 51.58%). This suggests that while higher levels of education appear to be associated with a reduced likelihood of NEET status, variations in study contexts may influence the strength of this relationship. In contrast, prior unemployment experience before becoming NEET presented a more complex picture, with a pooled odds ratio of 1.98 (95% CI: 0.72, 3.25; I2 = 74.3%). According to these findings, NEET status and prior unemployment experience are strongly related (Genda, Citation2007; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Rodriguez-Modroño, Citation2019; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018). presents the link between education and unemployment experience factors and NEET status.

Socio-economic factors

The analysis of four studies focusing on deprivation factors revealed a pooled odds ratio of 1.24, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 0.85 to 1.62. This analysis displayed relatively low heterogeneity (I2 = 15.29%). These findings suggest that residing or experiencing socio-economic deprivation is associated with a moderately increased risk of NEET status among young individuals. Another pivotal factor examined was criminal behaviour, as reported in four studies. The pooled odds ratio for this factor was calculated to be 2.06, with a 95% CI spanning from 1.47 to 2.65. However, this analysis demonstrated substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 18.82%). The relationship between Socio-economics factors and NEET status is depicted in . These results imply that engagement in criminal behaviour is a substantial risk factor for NEET status, underscoring the need for interventions targeting youth involved in criminal activities.

Health and well-being factors

We examined various health-related factors in our analysis of factors contributing to NEET status. Among these factors, anxiety emerged as a mental health contributor (Basta et al., Citation2019; Benjet et al., Citation2012; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Holloway et al., Citation2018; Power et al., Citation2015). A meta-analysis of seven studies revealed a pooled odds ratio of 1.29 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.65; I2 = 97.7%). The findings suggest that anxiety plays an important role in contributing to youth’s NEET status, although the strength of this association varies across studies.

We also examined the presence of any psychological problems, with an analysis of 14 studies resulting in a pooled odds ratio of 1.28 (95% CI: 0.89, 1.68; I2 = 81.7%) (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Bania et al., Citation2019; Benjet et al., Citation2012; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Hale & Viner, Citation2018; Henderson et al., Citation2017; Holloway et al., Citation2018; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Lin & Chiao, Citation2022; Maraj et al., Citation2019; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Power et al., Citation2015; Stea, Abildsnes, et al., Citation2019; Tayfur et al., Citation2022). This finding emphasizes the substantial impact of psychological well-being on NEET status among young individuals.

The analysis of depressive disorders, encompassing six studies, showed a pooled odds ratio of 1.51 (95% CI: 0.90, 2.12; I2 = 66.62%), underlining the potential role of depressive disorders in contributing to NEET status (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Holloway et al., Citation2018; Lin & Chiao, Citation2022; Power et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, we explored the association of NEET status with suicidal tendencies, analysing four studies that revealed a significant pooled odds ratio of 2.8 (95% CI: 1.8, 3.8; I2 = 34.9%). These results underscore the severe implications of suicide risk in relation to NEET status (Benjet et al., Citation2012; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Power et al., Citation2015).

Physical health problems were also considered, and the analysis of eight studies indicated a pooled odds ratio of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.67; I2 = 21.8%), emphasizing the importance of physical health in understanding the NEET phenomenon (Bania et al., Citation2019; Cabral, Citation2018; Flynn & Tessier, Citation2011; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Schoon, Citation2014; Su et al., Citation2022; Tamesberger & Bacher, Citation2014).

In our study of substance use as an aspect of overall health and well-being, we examined factors related to addiction. The pooled odds ratio for alcohol use, based on nine studies, was 1.09 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.25; I2 = 10.23%) (Basta et al., Citation2019; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Hale & Viner, Citation2018; Manhica et al., Citation2019; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Tonje H; Stea, Abildsnes, et al., Citation2019). For cannabis use, based on eight studies, the pooled odds ratio was 1.57 (95% CI: 1.06, 2.07; I2 = 59.23%) (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Basta et al., Citation2019; Gariepy & Iyer, Citation2019; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Hale & Viner, Citation2018; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Tonje H; Stea, Abildsnes, et al., Citation2019). Smoking, a specific form of substance use, revealed a substantial pooled odds ratio of 1.77 (95% CI: 1.26, 2.29; I2 = 32.95%) across five studies (Basta et al., Citation2019; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Hale & Viner, Citation2018; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Tonje H; Stea, Abildsnes, et al., Citation2019). Lastly, our analysis of drug use, based on 12 studies, demonstrated a pooled odds ratio of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.93; I2 = 38.73%) (Benjet et al., Citation2012; Flynn & Tessier, Citation2011; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Gutiérrez-García et al., Citation2018; Henderson et al., Citation2017; Holloway et al., Citation2018; Lin & Chiao, Citation2022; Maraj et al., Citation2019; O’Dea, Glozier, et al., Citation2014; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2022; Tayfur et al., Citation2022). The association between Health and well-being factors and NEET status is presented in .

These findings underscore the complex interplay of various health-related factors and their association with NEET status. It is evident that anxiety, along with other factors, contributes significantly to understanding the phenomenon of youth disengagement from education, employment, or training. The high levels of heterogeneity in some of these associations suggest the need for further research to explore the nuances and contextual factors that underlie these relationships. summarizes findings by type of risk factors and the result of pooled OR.

Table 2. Summary of findings by type of risk factors and the result of pooled OR.

Associations by gender

Seven studies conducted a gender-stratified analysis (Alfieri et al., Citation2015; Bania et al., Citation2019; Lallukka et al., Citation2019; Luthra & Sottie, Citation2019; Rodriguez-Modroño, Citation2019; Schoon, Citation2014; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018). According to a study by Bania et al. (Citation2019), ethnicity significantly predicts a higher likelihood of NEET status for men with an odds ratio of 1.58 (1.02 to 2.44, p = 0.039). However, ethnicity was not a significant predictor of NEET status for females with OR of 0.74 (0.46 to 1.17, p = 0.20). Parental lower education significantly increased the risk of experiencing NEET status for both genders, with the risk being higher for men (OR = 3.22, 1.60 to 6.47, p = 0.001) than for women (OR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.21 to 3.69, p = 0.009). Schoon’s research highlights that boys growing up with a single parent (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.87,1.22) are slightly more likely to be NEET than females (OR = 0.43, CI 0.27,0.62) in similar circumstances (Schoon, Citation2014).

Mental health problems were associated with lower odds of becoming NEET in men (OR = 0.88, 0.81 to 0.97, p = 0.008), but not in women (OR 1.04, 95% CI = 0.97,1.11, p = 0.28).

The OR for mental disorders among men was 2.23 (95% CI: 2.10 to 2.36), indicating a substantially increased risk. The OR was also elevated for women but relatively lower at 1.71 (95% CI = 1.61 to 1.81) (Lallukka et al., Citation2019).

Luthra and Sottie (Citation2019) found that having an immigrant history (OR = 1.46, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 1.24,1.72) and living with one’s parents (OR = 1.34, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 1.19,1.52) were characteristics suggesting a greater risk of being NEET for males. However, for women with an immigrant history (OR = 1.01, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 0.83,1.2) and married women (OR = 3.92, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 2.93,5.24), these factors elevated the likelihood of becoming NEET considerably.

Marital status also displayed a gender disparity. The OR for NEET status among unmarried men was 1.49 (95% CI = 1.35 to 1.65), indicating an increased risk. Conversely, unmarried women had a lower OR of 0.91 (95% CI = 0.82 to 1.00), suggesting a reduced risk of NEET status. For divorced individuals, gender differences persist. Divorced men had a considerably higher OR of 2.02 (95% CI = 1.56 to 2.60), while divorced women demonstrated a lower OR of 1.43 (95% CI = 1.17 to 1.75) (Lallukka et al., Citation2019).

The study by Henderson et al. (Citation2017) indicated that substance misuse was associated with being NEET for both men (OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.43, 2.34) and women (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.58; 2.66).

Individuals with a higher level of education are less likely to be in the NEET category. This effect is particularly pronounced among women (OR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.09, 0.59) compared to men (OR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.72). In the case of men, having parents with a low income (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.09, 3.15) increases the likelihood of being a NEET compared to women OR of 1.15 (95% CI = 0.71, 1.86). Having caring responsibilities OR of 2.80 (95% CI = 1.33, 6.01) and unemployment experience OR of 3.19 (95% CI = 1.73, 5.91), considerably enhances the risk of becoming a NEET for women (Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018).

Associations by age

Our comprehensive analysis encompassed various studies, each investigating different age groups: 15–18 years (5 studies) (Bania et al., Citation2019; Benjet et al., Citation2012; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Henderson et al., Citation2017; Lallukka et al., Citation2019), 19–24 years (8 studies) (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Goldman-Mellor et al., Citation2016; Gutierrez-Garcia et al., Citation2018; Hale & Viner, Citation2018; Power et al., Citation2015; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018; Yang, Citation2020), and those aged 25 years and above (3 studies) (Luthra & Sottie, Citation2019; Rodwell et al., Citation2018; Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018; Yang, Citation2020). In the youngest age bracket (15–18 years), there were strong correlations between NEET status and mental health issues, behavioural problems, addiction problems, and caring responsibility. For instance, one study reported a significant association between mental health problems and NEET status 2.70 (95% CI = 1.77, 4.12). The link between behavioural problems and NEET status was also substantial use (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.18, 1.30). The strongest variable in the simple analyses was being a single parent to a child or children under 18 years old, which was suggested almost six times (OR = 5.55, p < 0.001, CI = 4.14, 7.43). Conversely, family factors and health and well-being factors demonstrated weaker associations with NEET status in this age group.

Multiple factors were associated with NEET status in the 19–24 year bracket. These included marital status (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.12, 2.26), responsibility (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.12; 1.55), addiction problems (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.16), mental illness issues (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.21, 2.54), and criminal behaviour (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.08, 1.22). Vancea and Utzet (Citation2018) further noted that, for this age group, a higher educational level significantly reduced the likelihood of NEET status, particularly among women 0.29 (95% CI = 0.08, 0.93), and for men, a higher educational level is 0.47 (95% CI = 0.13, 1.47).

The evidence was mixed in the oldest age group (≥25). Marital status, criminal behaviour, and addiction problems showed inconsistent associations across studies. However, some patterns emerged. For instance, there was an association between marital status and NEET status (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.07, 1.21). Higher education level was associated with a lower likelihood of being NEET 0.22 (95% CI = 0.11, 0.42). For women, having caring responsibilities increased the risk of being NEET OR of 1.96 (95% CI = 1.18, 3.30), while for men, these responsibilities decreased the risk OR of 0.48 and 95% CI (0.25, 0.91) (Vancea & Utzet, Citation2018).

The impact of age on NEET status reveals an interesting pattern. Evidence suggests that the likelihood of being NEET increases with age, particularly for, although some studies have reported higher rates among males as well. Specifically, NEET status was more likely to occur among males aged between 20 and 25, with an odds ratio of 2.42 (95% CI = 1.64 to 3.57) (O’Dea, Lee, et al., Citation2016).

Contrarily, Yang (Citation2020) identified a declining risk of NEET status with age beyond the mid-20s. The odds of being NEET were found to be 14.67 times greater for those aged 26 to 29 and 12.41 times greater for those aged 30 to 35 compared to those aged 16 to 21. This finding suggests a shift in the age-related risk of NEET status, with the risk decreasing as individuals transition from youth to adulthood. This trend is echoed in Luthra’s findings (2019), which indicated a lower likelihood of being NEET for both men (OR = 0.60, p < 0.001, CI = 0.53,0.69) and women (OR = 0.56, p < 0.001, CI = 0.48,0.65) aged 25 years or older.

Holloway et al. (Citation2018) further explored this relationship between age and NEET status, revealing that the relevance of age as a predictor of NEET status varied between adolescents and young adults. For adolescents, increasing age was associated with a near doubling of the risk of NEET status (OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.87, 1.98), while for young adults, the increase was more modest (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.98, 1.11).

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 published studies has shown that a wide range of variables influence NEET status. We have thoroughly examined these aspects, including their overall influence and differentiation based on gender and age cohorts. NEET status elements can be better understood using this approach. We enhanced our comprehension by examining the interconnections among demographic factors, family factors, educational and unemployment experience factors, socio-economic factors, and health and well-being factors, shedding light on the complexity of the NEET phenomenon. Our study highlights the substantial correlations between these characteristics and the NEET phenomenon, enhancing our understanding of its multidimensional nature.

Demographic factors

Demographic factors significantly influence youth’s risk of becoming NEET. There is a modest trend indicating that ethnicity may have a role in becoming NEET youth. However, the confidence interval range across both sides of the unity line underscores the need for careful and measured interpretation. The examination of several studies demonstrates a complex association whereby some ethnic groups are more likely to be classified as NEET than others (Bania et al., Citation2019; Karyda & Jenkins, Citation2018; Yang, Citation2020). Nevertheless, it is crucial to underscore that the effect of ethnicity on NEET is context-dependent to the particular circumstances, as social structures and the varying possibilities accessible within various groups shape it. Ethnicity can influence NEET status through factors such as discrimination, cultural expectations, and access to resources. Language barriers and socio-economic conditions, typically linked to ethnicity, negatively impact education and employment opportunities (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023).

We found a link between migrant status and NEET status. The odds ratio was illuminating but not conclusive. The high level of heterogeneity in the results is an important finding of our analysis. This marked variation may be due to sociocultural, economic, or legal differences across the studied regions. In other words, while migrant status may be a factor in NEET status in one region, it may not be as influential in another due to local policies, societal acceptance, integration programmes, or other contextual factors (Bacher et al., Citation2020). Considerable attention has been paid to second-generation immigrants stemming from low-skilled migration waves. This cohort often navigates educational and employment pathways that demand lower skill levels, as evidenced by previous research (Laganà et al., Citation2014).

Marital status emerges as another demographic factor influencing NEET. The analysis underscores the diversity of contexts within which marital status operates. It is crucial to recognize that, although marital status tends to influence NEET, the extent and nature of this impact are subject to complex dynamics. The impact of marital status on NEET varies based on cultural norms, societal expectations, and economic conditions (Susanli, Citation2016). This finding emphasizes the importance of recognizing the multifaceted nature of marital status and its potential influence on youth.

Family-related factors

When considering family-related factors, it is clear that jobless parents and low income levels have a major impact on the chance of youths becoming NEET (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023). Our research has shown that a jobless parent significantly affects NEET. The statistical significance underscores the important role that a jobless parent holds in shaping the likelihood of individuals becoming NEET. The odds ratio of 1.53 indicates a substantial association between parental worklessness and NEET outcomes. These results highlight the interconnectivity of family relationships and socio-economic situations in defining a young adult’s destiny. Parental unemployment affects the family’s financial situation and also acts as a role model for youth regarding work ethics and ambitions.

Similarly, parental income influences a young person’s path towards school and work by providing critical resources for education and skill development (Rahmani & Groot, Citation2023). This demonstrates the clear influence of financial resources on youth disengagement. A higher parental income might minimize the likelihood of NEET status by allowing access to educational possibilities and career prospects. Our analysis included parents’ education, which is pivotal in shaping youth educational and career trajectories. A higher level of parental education frequently translates into greater access to educational resources, a supportive learning environment, and better career opportunities for their children, and consequently, it significantly influences the aspirations and goals of young individuals (Odoardi, Citation2020). However, the observed odds ratio indicates a moderate impact, suggesting that while parents’ education is influential, it is just one piece of the complex puzzle determining youth’s NEET status.

Education and unemployment experience

Education and unemployment experience are other characteristics that contribute to the complexity of NEET status among youth. The correlation between higher levels of education and a decreased risk of being classified as NEET typically holds true; however, the magnitude of this association differs depending on the specific research settings. As the absence of educational credentials harms all populations (Bonnard, Citation2020), dropping out of school makes young people more vulnerable, especially during economic crises (Salvà-Mut, Thomás-Vanrell, et al., Citation2016). Simultaneously, studies emphasize the vulnerability of young people with higher levels of education, as their access to the job market is dependent on labour market demands, which are dependent on national education and labour market regulations (Scandurra et al., Citation2020). In contrast, experiences of prior unemployment present a more complex dynamic. This calls for a more comprehensive understanding of how prior unemployment experiences may act as risk factors for dropping out altogether and entering the NEET state. This exploration should consider the duration of unemployment and the contextual factors that may influence this relationship. A complex interaction of variables such as economic conditions, the availability of employment options, and individual motives influence the relationship between unemployment experience and becoming NEET.

Socio-economic factors

Socio-economic factors, such as living in deprived areas, also come into play when understanding the NEET phenomenon. Residing in deprived areas is associated with a moderately increased risk of NEET among young individuals. This finding underscores the importance of addressing systemic inequalities and providing equal access to education and employment opportunities for youth living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Szpakowicz, Citation2022). Notably, the heterogeneity among these studies was relatively low (I2 = 26.9%), suggesting consistency in this finding. These results imply that residing or experiencing socio-economic deprivation may contribute to a moderately increased risk of NEET status among young individuals. According to Simões (Citation2018), certain constraints are faced by young individuals residing in rural regions. These constraints hinder the provision of effective support and the implementation of institutional arrangements and practices across multiple domains, such as social affairs, health, education, and employment. Consequently, these inadequacies can lead to disillusionment among young people, potentially resulting in their withdrawal from the labour market (Rikala, Citation2020).

Another significant factor explored in our analysis was criminal behaviour, as reported in four studies. These findings emphasize the critical role of criminal behaviour as a risk factor for NEET status. Interventions aimed at youth involved in criminal activity are critical for preventing or reducing the chance of becoming NEET. Risk behaviour research can be broadly categorized into two main areas. One area focuses on adopting a proactive approach among NEETs to mitigate the risk of becoming NEET if adequate support is not provided. The other area examines the influence of family background on the subsequent impact of risk behaviour among young individuals. When examining young individuals from privileged families, it is observed that engaging in early risk behaviours such as stimulant use and early sexual initiation does not correlate with the acquisition of NEET status. However, for young individuals from less privileged backgrounds, particularly males, exposure to stimulants at an early age (such as smoking and drug abuse) is found to predict negative outcomes later in life. Additionally, it has been confirmed that women in a NEET state are more likely to experience unplanned pregnancies. These findings are supported by the research conducted by Andrade and Jarvinen (Citation2017), Campbell et al. (Citation2020), and Tanton et al. (Citation2021).

Health and well-being

Health and well-being issues add another layer of complication to the NEET phenomenon. We delved into various health-related aspects. Notably, anxiety, a prevalent mental health concern, emerged as a contributor in our investigation. Anxiety significantly influences a young individual’s likelihood of being in the NEET category, although the strength of this association varies across studies. Our examination of psychological well-being provided valuable insights. We found that psychological problems have a significant impact on NEET status, highlighting the complex connection between mental well-being and young people disengaging from education or employment.

Additionally, our analysis indicated that depressive disorders might play a role in increasing the likelihood of youth becoming NEET. This underscores the importance of providing mental health support, especially for individuals dealing with depressive disorders, and emphasizes the need to integrate mental health services into educational and employment settings. Furthermore, considering suicide risk as a factor reveals its severe consequences in the context of NEET status. Our analysis demonstrated a notable link between suicide risk and NEET status. While research suggests a complex and potentially bidirectional relationship between suicide risk and NEET status, with both factors potentially influencing each other, this review focused solely on risk factors for entering NEET status. This decision aligns with the limitations of the included studies, which primarily investigated factors contributing to NEET status, and avoids making causal claims about the influence of NEET status on suicide risk. These findings underscore the urgency of addressing and preventing suicide risk, advocating for mental health and well-being services that cater to young individuals facing the challenges of NEET status. The findings show a significant relationship between mental illness and NEET outcomes, though the strength of this relationship varies across studies. This emphasizes the importance of early detection and support for youth mental health issues and incorporating mental health services into educational and employment programmes (Gariépy et al., Citation2021).

Our analysis also delves into the role of physical health and illness as factors influencing the transition to NEET status. The pooled odds ratio underscores the connection between physical health-related challenges and the likelihood of becoming NEET. The moderate level of heterogeneity suggests that while the overall relationship is present, contextual factors and variations contribute to the differing impact of physical health issues on NEET status.

Our meta-analysis underscores the significance of addiction as a crucial facet of health and well-being contributing to NEET status. The pooled odds for alcohol, cannabis, drug use and smoking emphasize the linkage between addiction and the likelihood of becoming NEET and highlight complex and varied pathways through which addiction influences youth disengagement.

Juberg and Skjefstad (Citation2019) argue that there is limited empirical support for the notion that transitioning into NEET status is directly caused by drug abuse. However, they acknowledge that the alcohol and drug problems experienced by young individuals can significantly impair their long-term employability. Consequently, it is crucial to exercise caution in perpetuating misconceptions regarding NEET youth.

Gender-specific

Despite a limited evidence base and most gender-specific, our study did not identify a distinct gender-based pattern in the relationship between risk factors and NEET status. However, it is evident that NEET experiences are gender-differentiated. Our gender-based associations reveal that while factors such as substance misuse and parental education level influence both genders, their impact is not uniform. For example, mental health issues and immigrant history have disparate implications for men and women. Women are more likely to fall into NEET than men due to factors such as marital status and caring responsibilities that underscore the necessity for interventions tailored to each gender.

Age-specific

The age analysis reveals that while some factors such as mental health issues and addiction problems, affect all age groups, their impact varies. For instance, caring responsibilities have different implications for different age groups. Furthermore, certain factors like marital status and educational level show age-specific trends. The research findings suggest that there is a gradual increase in the likelihood of individuals becoming NEET as they age, although this relationship is not strictly linear. It is worth noting that individuals between the ages of 25 and 30 demonstrate a greater chance of being classified as NEET than other age cohorts. Also, the findings of NEET-related gender-based studies vary from country to country emphasizing the need for age-tailored interventions.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study has several notable strengths. First, all the studies included in this review demonstrated a moderate to high methodological quality, enhancing our findings’ dependability. Second, our review’s strengths include using comprehensive systematic review procedures, which include artificial intelligence-supported dual screening of titles and abstracts, full-text evaluation, risk of bias assessment, and searching pertinent data up to October 2023. Third, this study marks the first attempt to synthesize the comprehensive evidence on the NEET phenomenon. It differs from prior research by taking a more holistic approach to examining demographic, family, educational and unemployment experience, socio-economic, and health and well-being factors rather than relying on a predefined selection of specific terms.

Despite its strengths, this study does exhibit several limitations. Due to the limitations of cross-sectional data and the focus of the included studies, this review cannot establish causal relationships between the identified factors and NEET status. The analysis is limited to exploring associations between factors and the risk of entering the NEET category, not the potential influence of NEET status on other variables. High statistical heterogeneity was observed across meta-analyses, and in one instance, this heterogeneity persisted even after a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. This may impact the precision and generalizability of the findings. Including a limited number of studies in some of the meta-analysis conducted may contribute to biased estimates of the overall effect size, a common challenge in meta-analysis research. The research articles were primarily sourced from frequently used databases, potentially omitting relevant studies not present in these databases. Because control variables were not readily available in many of the included studies, we were unable to conduct comprehensive subgroup analyses that could account for potential confounding factors influencing the relationship between risk factors and NEET status. This limitation restricts the generalizability of the findings beyond the observed associations within each subgroup category (e.g. gender, age). Future research may benefit from a broader range of database sources. Additionally, the analysis in this study exclusively relied on quantitative studies, which might introduce sampling bias, as some pertinent qualitative insights could have been overlooked.

Several potential directions for future research remain unexplored. Firstly, there is a need to broaden the geographical scope of investigations. Research in underrepresented areas is crucial because educational systems differ depending on the country, and successful transition pathways could be diverse across developed and developing countries. Considering that most youth worldwide reside in developing countries, where the influence of psychosocial factors may vary by economic and cultural contexts, it is essential to determine whether the existing research applies to youth in these diverse settings. This issue should be a priority in future research.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to provide stronger evidence for causal relationships between potential risk factors and NEET status and providing insights into the long-term implications of being NEET. Furthermore, future studies could consider expanding the range of databases used for literature retrieval, potentially uncovering research that was missed in this review. Gathering personal information from NEET youth related to mental, emotional, and psychological factors through direct interviews could provide unique insights not typically available in large-scale surveys and also integrating qualitative studies alongside quantitative methods can provide a deeper understanding of the lived experiences and perspectives of NEET youth, offering valuable insights beyond survey data.

Future research should prioritize methodologies that enable the exploration of diverse risk factors associated with NEET status while effectively controlling for potential confounding variables.

The NEET phenomenon warrants further exploration, with future research aiming to test the associations of different factors together and their combined effects. Researchers could enrich the diversity of targeted participants by conducting studies across various subgroups, including those working in high-skilled versus low-skilled jobs and individuals facing different types of vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis significantly contributes to our understanding of NEET youth. We identify robust predictors, including suicide risk, unemployment experience, and involvement in criminal behaviour, along with the protective factor of higher education. Our analysis highlights demographic disparities and evolving trends, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions. These findings have practical implications, such as calling for customized support systems. While our study provides a strong foundation for addressing NEET prevalence, ongoing research is crucial, given the evolving nature of this issue. We hope this research inspires further study and evidence-based policies to empower NEET youth to pursue education, employment, and training.

Ethics approval

The study does not require ethical approval because the meta-analysis is based on published research and the original data are anonymous.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aina, C., Brunetti, I., Mussida, C., & Schicchitano, S. (2021). Even more discouraged? The NEET generation at the age of covid-19.

- Akinyemi, B. E., & Mushunje, A. (2017). Born free but ‘NEET’: Determinants of rural youth’s participation in agricultural activities in eastern cape province, South Africa [article]. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(26), 521–37. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85041176551&partnerID=40&md5=05ad87094e04540c458062d7ec41c43f

- Alcazar, L., Balarin, M., Glave, C., & Rodriguez, M. F. (2020, February 7). Fractured lives: Understanding urban youth vulnerability in Peru. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(2), 140–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1587154

- Alfieri, S., Sironi, E., Marta, E., Rosina, A., & Marzana, D. (2015). Young Italian NEETs (not in employment, education, or training) and the influence of their family background [article]. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i2.901

- Andrade, S. B., & Jarvinen, M. (2017). More risky for some than others: Negative life events among young risk-takers. Health, Risk & Society, 19(7–8), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2017.1413172

- Apunyo, R., White, H., Otike, C., Katairo, T., Puerto, S., Gardiner, D., Kinengyere, A. A., Eyers, J., Saran, A., & Obuku, E. A. (2022). Interventions to increase youth employment: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(1), e1216. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1216

- Bacher, J., Fiorioli, E., Moosbrugger, R., Nnebedum, C., Prandner, D., & Shovakar, N. (2020). Integration of refugees at universities: Austria’s more initiative. Higher Education, 79(6), 943–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00449-6

- Baggio, S., Iglesias, K., Deline, S., Studer, J., Henchoz, Y., Mohler-Kuo, M., & Gmel, G. (2015, February). Not in education, employment, or training status among young Swiss men. Longitudinal associations with mental health and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.006

- Bania, E. V., Eckhoff, C., & Kvernmo, S. (2019, June). Not engaged in education, employment or training (NEET) in an Arctic sociocultural context: The NAAHS cohort study. BMJ Open, 9(3), e023705. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023705

- Basta, M., Karakonstantis, S., Koutra, K., Dafermos, V., Papargiris, A., Drakaki, M., Tzagkarakis, S., Vgontzas, A., Simos, P., & Papadakis, N. (2019). NEET status among young Greeks: Association with mental health and substance use [article]. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.095

- Benjet, C., Hernandez-Montoya, D., Borges, G., Mendez, E., Elena Medina-Mora, M., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2012, July-August). Youth who neither study nor work: Mental health, education and employment. Salud Publica De Mexico, 54(4), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342012000400011

- Boissonneault, M., Mulders, J. O., Turek, K., Carriere, Y., & Lanza Queiroz, B. (2020). A systematic review of causes of recent increases in ages of labor market exit in OECD countries. Public Library of Science ONE, 15(4), e0231897. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231897

- Bonnard, C. (2020). What employability for higher education students? Journal of Education & Work, 33(5–6), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1842866

- Cabral, F. J. (2018). Key drivers of NEET phenomenon among youth people in Senegal [article]. Economics Bulletin, 38(1), 248–261. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85042043242&partnerID=40&md5=98b69368e077c9891978b3d73f22c175

- Campbell, R., Wright, C., Hickman, M., Kipping, R. R., Smith, M., Pouliou, T., & Heron, J. (2020, September). Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence is associated with substantial adverse health and social outcomes in early adulthood: Findings from a prospective birth cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 138, 106157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106157

- Cragg, A., Hau, J. P., Woo, S. A., Kitchen, S. A., Liu, C., Doyle-Waters, M. M., & Hohl, C. M. (2019). Risk factors for misuse of prescribed opioids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 74(5), 634–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.019

- Dickens, L., & Marx, P. (2020). NEET as an outcome for care leavers in South Africa: The case of girls and boys town [article]. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818805891

- Duckworth, K., & Schoon, I. (2012). Beating the odds: Exploring the impact of social risk on young people’s school-to-work transitions during recession in the UK [article]. National Institute Economic Review, 222(1), R38–R51. https://doi.org/10.1177/002795011222200104

- Escudero, V., & López Mourelo, E. (2017). The European youth guarantee: A systematic review of its implementation across countries. ILO Working Papers, 21.

- Filia, K. M., Teo, S. M., Brennan, N., Freeburn, T., Baker, D., Browne, V., Watson, A., Prasad, A., Killackey, E., & McGorry, P. D. (2023). Interrelationships between social exclusion, mental health and wellbeing in adolescents: Insights from a national youth survey.

- Flynn, R. J., & Tessier, N. G. (2011, December). Promotive and risk factors as concurrent predictors of educational outcomes in supported transitional living: Extended care and maintenance in Ontario, Canada. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(12), 2498–2503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.014

- Gariépy, G., Danna, S. M., Hawke, L., Henderson, J., & Iyer, S. N. (2021). The mental health of young people who are not in education, employment, or training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02212-8

- Gariepy, G., & Iyer, S. (2019, May). The mental health of young Canadians who are not working or in school. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 64(5), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718815899

- Genda, Y. (2007). Jobless youths and the NEET problem in Japan [article]. Social Science Japan Journal, 10(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jym029

- Gholizadeh, S., & Mohammadkazemi, R. (2022). International entrepreneurial opportunity: A systematic review, meta-synthesis, and future research agenda. The Journal of International, 20(2), 218–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-021-00306-7

- Giret, J. F., Guégnard, C., & Joseph, O. (2020). School-to-work transition in France: The role of education in escaping long-term NEET trajectories [article]. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 39(5–6), 428–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2020.1796835

- Goldman-Mellor, S., Caspi, A., Arseneault, L., Ajala, N., Ambler, A., Danese, A., Fisher, H., Hucker, A., Odgers, C., Williams, T., Wong, C., & Moffitt, T. E. (2016). Committed to work but vulnerable: Self-perceptions and mental health in NEET 18-year olds from a contemporary British cohort [article]. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 57(2), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12459

- Gutierrez-Garcia, R. A., Benjet, C., Borges, G., Mendez Rios, E., & Elena Medina-Mora, M. (2018, October). Emerging adults not in education, employment or training (NEET): Socio-demographic characteristics, mental health and reasons for being NEET. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6103-4

- Gutiérrez-García, R. A., Benjet, C., Borges, G., Méndez Ríos, E., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2018). Emerging adults not in education, employment or training (NEET): Socio-demographic characteristics, mental health and reasons for being NEET [article]. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6103-4

- Hale, D. R., & Viner, R. M. (2018, June). How adolescent health influences education and employment: Investigating longitudinal associations and mechanisms. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(6), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209605

- Henderson, J. L., Hawke, L. D., Chaim, G., & National Youth Screening Project, N. (2017). Not in employment, education or training: Mental health, substance use, and disengagement in a multi-sectoral sample of service-seeking Canadian youth [article]. Children and Youth Services Review, 75, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.024

- Holloway, E. M., Rickwood, D., Rehm, I. C., Meyer, D., Griffiths, S., & Telford, N. (2018). Non-participation in education, employment, and training among young people accessing youth mental health services: Demographic and clinical correlates. Advances in Mental Health, 16(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2017.1342553

- ILO. (2017). Global employment trends for youth 2017: Paths to a better working future. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_598669.pdf

- ILO. (2021). An update on the youth labour market impact of the COVID-19 crisis. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/briefingnote/wcms_795479.pdf

- Juberg, A., & Skjefstad, N. S. (2019). ‘NEET’ to work?–substance use disorder and youth unemployment in Norwegian public documents [article]. European Journal of Social Work, 22(2), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1531829

- Karyda, M. (2020). The influence of neighbourhood crime on young people becoming not in education, employment or training [article]. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(3), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1707064

- Karyda, M., & Jenkins, A. (2018). Disadvantaged neighbourhoods and young people not in education, employment or training at the ages of 18 to 19 in England [article]. Journal of Education & Work, 31(3), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2018.1475725

- Kevelson, M. J. C., Marconi, G., Millett, C. M., & Zhelyazkova, N. (2020). College educated yet disconnected: Exploring disconnection from education and employment in OECD Countries, with a comparative focus on the U.S [article]. ETS Research Report Series, 2020(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12305

- Laganà, F., Chevillard, J., & Gauthier, J. A. (2014). Socio-economic background and early post-compulsory education pathways: A comparison between natives and second-generation immigrants in Switzerland [article]. European Sociological Review, 30(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct019

- Lallukka, T., Kerkelä, M., Ristikari, T., Merikukka, M., Hiilamo, H., Virtanen, M., Øverland, S., Gissler, M., & Halonen, J. I. (2019, August 01). Determinants of long-term unemployment in early adulthood: A Finnish birth cohort study. SSM - Population Health, 8, 100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100410

- Lee, B.-H., & Kim, J.-S. (2012, July-August). A causal analysis of youth inactiveness in the Korean labor market. Korea journal, 52(4), 139–165. https://doi.org/10.25024/kj.2012.52.4.139

- Lin, W.-H., & Chiao, C. (2022). The relationship between adverse childhood experience and heavy smoking in emerging adulthood: The role of not in education, employment, or training status. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.022

- Lindhardt, L., Storebø, O. J., Bruun, L. S., Simonsen, E., & Mortensen, O. S. (2022). Psychosis among the disconnected youth: A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), 2056306. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2056306

- Li, T. M., & Wong, P. W. (2015). Youth social withdrawal behavior (hikikomori): A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415581179

- Luthra, R., & Sottie, C. (2019). Young adults with intellectual disability who are not in employment, education, or daily activities: Family situation and its relation to occupational status [article]. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1622484. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1622484

- Manhica, H., Lundin, A., & Danielsson, A. K. (2019). Not in education, employment, or training (NEET) and risk of alcohol use disorder: A nationwide register-linkage study with 485 839 Swedish youths [article]. BMJ Open, 9(10), e032888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032888

- Maraj, A., Mustafa, S., Joober, R., Malla, A., Shah, J. L., & Iyer, S. N. (2019, April). Caught in the “NEET trap”: The intersection between vocational inactivity and disengagement from an early intervention service for psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 70(4), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800319

- Matli, W., & Ngoepe, M. (2021). Life situations and lived experiences of young people who are not in education, employment, or training in South Africa. Education+ Training, 63(9), 1242–1257. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2019-0231

- Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C., & Stain, H. J. (2017). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

- O’Dea, B., Glozier, N., Purcell, R., McGorry, P. D., Scott, J., Feilds, K. L., Hermens, D. F., Buchanan, J., Scott, E. M., Yung, A. R., Killacky, E., Guastella, A. J., & Hickie, I. B. (2014). A cross-sectional exploration of the clinical characteristics of disengaged (NEET) young people in primary mental healthcare [article]. BMJ Open, 4(12), e006378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006378

- O’Dea, B., Lee, R. S. C., McGorry, P. D., Hickie, I. B., Scott, J., Hermens, D. F., Mykeltun, A., Purcell, R., Killackey, E., Pantelis, C., Amminger, G. P., & Glozier, N. (2016). A prospective cohort study of depression course, functional disability, and NEET status in help-seeking young adults [article]. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(10), 1395–1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1272-x

- Odoardi, I. (2020). Can parents’ education lay the foundation for reducing the inactivity of young people? A regional analysis of Italian NEETs [article]. Economia Politica, 37(1), 307–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-019-00162-8

- Paabort, H., Flynn, P., Beilmann, M., & Petrescu, C. (2023). Policy responses to real world challenges associated with NEET youth: A scoping review. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 5, 1154464. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2023.1154464

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E. … Whiting, P. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Pitkänen, J., Remes, H., Moustgaard, H., & Martikainen, P. (2021). Parental socioeconomic resources and adverse childhood experiences as predictors of not in education, employment, or training: A Finnish register-based longitudinal study [article]. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1679745

- Power, E., Clarke, M., Kelleher, I., Coughlan, H., Lynch, F., Connor, D., Fitzpatrick, C., Harley, M., & Cannon, M. (2015). The association between economic inactivity and mental health among young people: A longitudinal study of young adults who are not in employment, education or training [article]. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2014.85

- Quintano, C., Mazzocchi, P., & Rocca, A. (2018). The determinants of Italian NEETs and the effects of the economic crisis [article]. Genus, 74(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0031-0

- Rahmani, H., & Groot, W. (2023). Risk factors of being a youth not in education, employment or training (NEET): A scoping review. International Journal of Educational Research, 120, 102198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102198

- Rikala, S. (2020). Agency among young people in marginalised positions: Towards a better understanding of mental health problems [article]. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(8), 1022–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1651929

- Ringbom, I., Suvisaari, J., Kääriälä, A., Sourander, A., Gissler, M., Ristikari, T., & Gyllenberg, D. (2022). Psychiatric disorders diagnosed in adolescence and subsequent long-term exclusion from education, employment or training: Longitudinal national birth cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 220(3), 148–153.

- Rodriguez-Modroño, P. (2019). Youth unemployment, NEETs and structural inequality in Spain [article]. International Journal of Manpower, 40(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2018-0098

- Rodwell, L., Romaniuk, H., Nilsen, W., Carlin, J. B., Lee, K. J., & Patton, G. C. (2018). Adolescent mental health and behavioural predictors of being NEET: A prospective study of young adults not in employment, education, or training [article]. Psychological Medicine, 48(5), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002434

- Ruesga-Benito, S. M., González-Laxe, F., & Picatoste, X. (2018). Sustainable development, poverty, and risk of exclusion for young people in the European Union: The case of NEETs [article]. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(12), 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124708

- Salvà-Mut, F., Thomás-Vanrell, C., & Quintana-Murci, E. (2016). School-to-work transitions in times of crisis: The case of Spanish youth without qualifications [article]. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1098768