ABSTRACT

Few changes have been so abruptly disruptive to apprenticeships worldwide as the global COVID outbreak from early 2020 onwards. Because apprenticeships involve experience in workplaces (normally via employment), as well as participation in education systems, the effects were especially serious. There was extra urgency to policy responses because apprenticeships are disproportionately, and in some countries, exclusively, undertaken by young people. There were no worldwide ‘answers’ as to what to do, as apprenticeship systems vary greatly among countries. The paper examines the development of apprenticeship-related measures in several countries worldwide, with a particular focus on Australia and England. The paper uses statistical data, government announcements, guidance from stakeholders and officials, and also a systematic analysis of presentations by leading country experts at an online international apprenticeship conference in May 2021. Reflecting on common concerns on apprenticeship system, the paper critiques and analyses the effects and potential effects of COVID and post-COVID measures on apprenticeship systems.

1. Introduction

Apprenticeships are one of the oldest forms of vocational training, and over centuries have evolved as economies, societies, and education systems have changed (Smith Citation2010). They involve an apprentice’s relationship with an employer, and an element of learning: on-the-job and also, usually, off-the-job as well. The term ‘dual system’, applied generally to German-speaking countries, refers to the duality of on the job and off the job training. Off-the-job learning usually takes place within vocational education and training (VET) systems, although in some countries ‘degree apprenticeships’ are available, albeit in low numbers (Newton Citation2021). Although apprenticeships are not confined to young people, at least not in most countries, they are often seen as pivotal in so-called school-to-work transition, and are often embedded in political systems, usually with tripartite involvement (OECD Citation2018). Apprenticeships are much more important in some countries than others; numbers vary greatly across countries, but in over 50 countries more than one in a thousand workers is an apprentice (Chankseliani, Keep, and Wilde Citation2017).

In the history of apprenticeships, perhaps few changes have been so sudden and so universal to apprenticeships worldwide as the global COVID outbreak from early 2020 onwards. As apprenticeship systems are intimately linked to employers, employment, education and youth policy, there was no aspect of apprenticeships that was not affected. Moreover, as every country has a different apprenticeship system – in different industries, and targeting different age cohorts – solutions from one country could not necessarily be applied in another.

In the early days of the pandemic and associated lockdowns, there were fears of mass unemployment and of a generation of young people who would experience great difficulty entering the labour market (e.g. Schoon and Mann Citation2020; Hurley Citation2020). Indeed, the pandemic did affect many apprentices and their employers, with worksites closing down or operating quite differently, and apprentices’ off-the-job as well as on-the-job training disrupted. However, economies began to recover much more quickly from the effects of the pandemic than could have been envisaged, with labour shortages rather than unemployment a major feature worldwide by the end of 2022 (e.g. Birch and Preston Citation2022).

What was perhaps forgotten in the early and gloomy predictions about apprenticeships was the way in which governments have always used apprenticeship systems as labour market tools and as social intervention points for young people. Thus there is a long tradition of intervention in economies and labour markets via apprenticeships; apprenticeships do not just react to circumstances. The paper points out that apprenticeship ‘rescue’ measures were designed not just to rescue apprenticeships but to rescue the whole economy by creating more jobs. But, interestingly, apprenticeship ‘rescue’ measures persisted well into the ‘recovery’ stage in some countries, including Australia. The effects of these measures could be potentially dysfunctional, but on the other hand, they could lead to a revival of apprenticeship, which is experiencing a decline in some countries, sometimes attributed to a result of the growth in higher education participation (e.g. Deissinger Citation2017).

2. Background and literature

This section briefly covers the nature of apprenticeship systems, moving onto COVID effects on employment, education and young people, all of which relate to apprenticeships. Finally the small literature specifically on COVID and apprenticeships is discussed.

2.1. Apprenticeship systems

International comparisons are notoriously difficult in apprenticeships (Markowitsch and Wittig Citation2020). For example, in Australia as in England, most apprentices are not teenagers; and apprentices are always employed, unlike in many other countries. German or Swiss apprentices, by contrast, are mainly secondary school students, although they are paid, albeit at a very low rate, for their time in workplaces (Smith, Tuck, and Chatani Citation2018). Nevertheless there are some similarities among countries. Apprenticeship systems typically involve high-level participation by governments, trade employers and trade unions (Bridgford Citation2017) in the formulation of policy (Wolf Citation2002); these negotiations are often contested, as the different parties bring their own agendas to the table in a way that is well-recognised across the worlds(e.g. Phillips KPA Citation2018). These tripartite arrangements also exist at industry level in many countries (e.g. Siekmann and Circelli Citation2021), and at local level, employers collaborate with training providers in delivery matters, although Gessler (Citation2017) notes that the extent of such collaboration is often overstated.

There are also many well-recognised problematic issues in apprenticeship policy and practice (Newton, Hirst, and Miller Citation2019). The role of gender is one; in many countries, apprenticeships are dominated by men (Gessler Citation2019) because they are, or were formerly, in masculinised occupations, although apprenticeships are now generally available in a wider range of occupations, extending female participation. Women have not, in the past, had easy access to well-regarded masculinised occupations although most countries now strive to attract women to such jobs (Gonon Citation2023). Apprenticeships in feminised areas, such as retail and front-of-house hospitality, are seen as less prestigious (e.g. Duemmler and Caprani Citation2017) than traditional apprenticeships typically undertaken by men. In some countries, for example Australia and England, apprenticeships in these occupations became available only in the 1980s, and are often assumed to be of lower quality and less ‘worthy’ (e.g. Richmond and Regan Citation2021; Fuller and Unwin Citation2003). Indeed the title of the paper by Fuller and Unwin (Citation2003) specifically critiques the ‘multi-sector, social inclusion approach to apprenticeships’. Because of these perceptions, differential funding of apprentice training among occupations, with feminised occupations receiving less funding (e.g. Smith Citation2021; Guthrie et al. Citation2014) are rarely challenged. Access to apprenticeships by individuals is also affected by location (with rural areas typically having fewer apprenticeships) and by citizenship status, with some countries not allowing access to apprenticeships to recent migrants or refugees (Smith, Tuck, and Chatani Citation2018).

The role of private training providers, which deliver a substantial proportion of VET in many countries (e.g. OECD Citation2022a; Gekara et al. Citation2014), poses problems for apprenticeships. Private intermediary bodies have also flourished (Smith Citation2019); these perform various brokerage or support services for apprentices and/or their employers; profiteering is common where government funding flows to private bodies, and services to apprentices and their employers may be sub-standard (Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS) Citation2013). All of these issues exist alongside the perennial issue of the low status of apprenticeships and of VET in general (Cedefop Citation2017). Apprenticeship numbers had been falling for some years pre-pandemic in many countries, partly due to the relative attractiveness and prestige of university study for school-leavers (Deissinger Citation2017).

2.2. The effects of COVID on employment

Since apprentices are either employed or have long periods in workplaces through other relationships, any restriction on the availability of workplaces is an immediate issue for apprenticeship systems; during the peak years of the COVID pandemic, many workplaces were unable to operate. The OECD noted that global GDP had already declined by 3% in the first quarter of 2020, even though most countries were only experiencing pandemic effects in March (OECD Citation2020a, 14). Activity continued to decline sharply in the second quarter of that year, with expectations voiced that one-quarter of the economy in many countries could shut down (OECD Citation2020a, 15). Unemployment rose dramatically in most countries by June 2020 (OECD Citation2020a, 17) as did global poverty (Safaei and Saliminezhad Citation2022). Dire predictions of recession were made, comparing the COVID effects to those of the Global Financial crisis (e.g. Mayhew and Anand Citation2020).

It was against this background of crisis that governments were making their initial decisions on how to protect the economy and their citizens’ incomes (as well as, of course, their health). Such measures included short-time wage subsidies to retain people in employment, and encouragement to companies to hire people displaced from the labour market (International Labour Organization (ILO) Citation2022). For example, in the UK, the Job Retention Scheme provided employers with 80% of the wages of workers who were temporarily suspended (or ‘on furlough’) during the pandemic (Mayhew and Anand Citation2020). The latter authors and also Saha, Carreras and Quak (Citation2022) point out that support for businesses (as opposed to support for individual people) to retain employees did not benefit all workers, especially those self-employed or in the informal economy. To help avert recession, governments also provided generous welfare payments to people who were not employed; for example in Australia the JobKeeper response provided increased benefits for individuals, higher than prior unemployment benefits, as well as payments to business to retain workers (Ray Citation2023).

The International Labour Organization (ILO), a tripartite agency of the United Nations, was very active in researching and publicising the effects of COVID on employment and on training. An early global survey of enterprises by the ILO covering March to June 2020 (ILO Citation2020) found that 86% of companies reported high or medium levels of financial impact in 2020, particularly small and medium companies; the majority reported having little or no reserves to cover the situation. However they were striving to retain their workforces (ILO Citation2020). There were, of course, also changes in the nature of work, with lockdowns meaning that people were required to work from home where possible, with restrictions continuing well into 2021 (ILO Citation2021a).

However, even in 2020 and certainly by 2021, the global labour market was recovering, albeit with reliance on job retention schemes at least initially (OECD Citation2022b). The post-COVID economic recovery created labour shortages in many industries, beginning in 2021 (Krumel, Goodrich, and Fiala Citation2023), but with differing impacts across countries (Kiss et al. Citation2022) . Australian unemployment, for example, fell from 5.1% in May 2021, considered to be a normal unemployment rate in pre-pandemic times, to 3.9% in May 2022; by 2022 31% of occupations were in shortage (National Skills Commission (NSC) Citation2022, 34). The U.K. also experienced an unusually tight labour market into 2023, with job vacancies still higher than pre pandemic (House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee Citation2023).

2.3. The effects of COVID on young people

During the COVID period there was a strong belief that young people’s employment prospects would be especially affected (e.g. Mayhew and Anand Citation2020 in the UK; Hurley Citation2020 in Australia). Reference was often made to the Global Financial Crisis (e.g. Schoon and Mann Citation2020), when youth unemployment had reached 40% in many EU countries, and the NEET (not in employment, education or training) figure had peaked at 16% across the EU for those aged 15 to 29 (Eurofound Citation2021, 3). Industry areas in which young people commonly work, such as retail, hospitality, health and arts and entertainment were particularly affected by COVID (Eurofound Citation2021) and therefore young people were more likely to become unemployed. While mental health issues rose for all groups during the pandemic, young people were particularly affected (Eurofound Citation2021). A Swiss study (Vacchiano Citation2022), undertaken after the initial Swiss lockdown, attributed this to young people’s reliance on social activities and networking, and also the loss of ‘weak networks’ fostered through interaction with fellow workers.

2.4. The effects of COVID on education

There has been much discussion of the effects, in all education sectors, of the COVID-necessitated move to online learning, how teachers struggled to learn new skills and adapt their teaching, and the differential effects on learners, arising from matters such as access to computers and connectivity. For example, an early survey in the state of Victoria in Australia listed many difficulties experiences by children and young people, with little support available (Commission for Children and Young People Citation2020). An international review by Tang (Citation2023) highlighted such disparities and documented the learning losses and mental stresses experienced by learners during lockdowns. Avis et al. (Citation2021) argue that students in VET, which include most apprentices, are particularly likely to experience disadvantage and difficulty in accessing online learning.

2.5. COVID and apprenticeships

Apprenticeship systems and apprentices themselves were especially vulnerable to the effects of COVID, involving as they do employment as well as education, and also catering, sometimes exclusively, and in most countries to a significant extent, for young people. The OECD (Citation2020b), early in the pandemic, reported that countries were already responding, with special arrangements for apprentice training, including allowing ‘breaks in learning’ and deferred examinations. Other countries, for example Estonia and Finland, allowed apprentices to make up ‘work based learning’ time with more training-provider based learning time (OECD Citation2020b, 5). Many countries included apprentices in normal COVID ‘furlough’ wage subsidies. While an Australian paper (Hurley Citation2020) forecast a large decline in apprenticeships, based on previous recessions, suggesting there would be a consequent increase of 50% in NEET school-leavers, at the time of the paper’s publication Australia had already introduced a 50% wage subsidy to help small businesses retain their apprentices.

An ILO study published in early 2021 (ILO Citation2021b) found that almost every country had closed face to face learning in VET training providers for at least a period of time; often this had happened almost overnight. The following issues were reported: inadequate electronic infrastructure, access to learning platforms, deficiencies in teacher capability and in knowledge about ways to continue with practical training. While there was a positive outcome in that digital capability in VET delivery improved as a result of the pandemic (Trimboli, Lees, and Zhang Citation2023), this varied greatly among countries (ILO Citation2021b). Some training providers closed down because they were unable to adapt to the new mode of delivery. Chan (Citation2021), in a study of apprentice training at training providers in New Zealand, found that while it was possible to continue with practical skills training, it was not easy. On workplace-based matters, an ILO study of enterprises, specifically on apprenticeships and internships, found that 86% of companies had had some interruption to apprenticeships; over half reported that training periods had been adjusted (ILO Citation2021c). Nearly half of companies mentioned difficulties in providing training, especially practical training, citing varied issues including observing social distancing and the suspension of normal operations such as hotel kitchens (ILO Citation2021c, 26).

A large-scale Austrian study of the mental well-being of apprentices found that overall their mental health results were in line with other adolescents and young adults at the time, but that females and migrants returned lower results, as did apprentices who had lost their jobs (Dale et al. Citation2021). The study contained questions on ‘burdens [faced] as a result of the pandemic’ which were separately analysed (Halder et al. Citation2022). While the largest category of responses related to lockdowns, responses that could be categorised into work and employment, ‘distance learning’ and ‘home office’ were the leading two. Several respondents expressed concern over whether they would pass the final exams considering the type of learning that was mandated.

3. Research method

This paper utilised two main research methods to examine responses of apprenticeship systems to COVID: an analysis of seven country experts’ powerpoint presentations at a small international online conference in May 2021 mounted by INAP, the International Network on Innovative Apprenticeship, and a detailed examination of governments’ COVID and post-COVID measures in Australia and England. The seven-country analysis provided an overview of COVID-related apprenticeships measures in the first year of the pandemic, while the later two-country analysis covered the entire COVID period as well as post-COVID developments. Both analyses involved both the working and the training aspects of apprenticeships.

The INAP conference scheduled for October 2020 in China had been cancelled, and the INAP Board instead decided to hold an online forum, hosted by the Urban Institute in the U.S., on the effects of COVID on apprenticeships in a range of countries, The INAP Board members, all academic experts but also with close links to governments, comprised six of the speakers, with an additional invited speaker from England. The speakers were given guidelines specifying four main content areas (context, type of, apprenticeship system, prior trends in numbers, COVID effects and measures).Footnote1 For this paper, a structured analysis was undertaken of the published powerpoint presentations, using these headings.

The findings are presented in , which also includes information on the size of the countries’ apprenticeship systems.Footnote2 The latter categorisation was derived for this paper from a graph by Chankseliani, Keep and Wilde (Citation2017, p.23) showing the proportion of apprentices in the labour force for the 52 countries for which more than 0.1% of the labour force were apprentices.

Table 1. Apprentice-related COVID actions, seven countries, reported by country experts May 2021.

COVID measures in Australia and England were researched in more detail, with Australia the major focus. In this phase, post-COVID as well as COVID measures and effects were examined. Australia was selected as the focus country partly because of the author’s knowledge of that system, but also because Australia, or at least the Australian state of Victoria, had the most lockdown days of any country (McLaren et al. Citation2023) and therefore might be expected to exhibit extremes of COVID effects. England was selected because its apprenticeship system is similar to Australia’s and comparisons were therefore possible. This phase of the research covered analysis of COVID-related and COVID recovery-related government policy measures; announcements and speeches on apprenticeship by public figures; newsletters of apprentice-related bodies; and conversations with key stakeholders – government officials and apprenticeship intermediary bodies – to guide document and web site searches, including the provision of access to web pages no longer active.

For analysis of the potential effects of the measures, the paper draws firstly on a theoretical model (Smith Citation2018), depicting the effects, on potential functions of apprenticeships, of different emphases in countries’ apprenticeship systems – youth employment and skill development. Secondly, the findings are analysed against the problematic aspects of apprenticeship identified in the literature review.

The paper has some limitations. Firstly, by covering a range of countries, not so much detail could be included as if one country was the sole focus. However it was felt that due to the variety of apprenticeships, it was preferable to include at least limited information from a range of countries. Secondly, the paper relies primarily on document analysis, albeit guided in the second part of the research by stakeholders. Interviews may have elicited more information, as Fassbender (Citation2022) notes in a German paper on VET responses to COVID; however, due to the political nature of the topic, key actors were unlikely to be willing to be interviewed ‘on the record’.

4. Research findings

4.1. Seven country analysis

A summary of the INAP conference powerpoint presentations from May 2021 is provided in . The table includes brief comments on the nature of the apprenticeship systems, showing that the Canadian apprenticeship is for adults and the apprentices are formally employed, while China, Germany and Switzerland, the system is primarily for school students. Somewhat surprisingly, COVID effects and responses varied greatly among countries, with the apprentice systems in China and Switzerland seemingly little affected compared with Canada and Germany.

As explained in the method section, the notes about the size of the systems are taken from Chankseliani, Keep and Wilde (Citation2017, p.23). Examination of the data from the latter paper showed natural breaks after the top 10 countries (over 30 apprentices per 1000 in the labour force, i.e. 3%), and after the following 9 countries (12 or more apprentices per 1000 in the labour force, i.e. 1.2%), with numbers gradually decreasing thereafter. In , therefore, ‘high’ means over 3.0% or more of the labour force in apprenticeships, ‘medium’ means between 1.2% and 3.0%, and ‘low’ means less than 1.2% of the labour force.

Three of the seven country authors presenting at the conference reported severe drops in apprentice numbers due to COVID. Variations did not necessarily correlate with the nature or size of the systems; for example, while Germany has a similar apprentice system to Switzerland, and both have high numbers, the COVID effects on apprentice-employing companies were more severe in Germany, and there were more government interventions. The U.S. presentation did not mention COVID effects; one inference that could be drawn is that apprentice numbers in the U.S. were so low (albeit increasing), and confined to one industry, that apprenticeship was not a vital matter for COVID policy. Off the job training for apprentices was affected in all locations (although Canada and the U.S. did not report on this matter), but there were varying degrees of concern about the efficacy of the off-the-job training and the well-being of learners. Two countries reported flexibilities in assessment and examinations.

Financial measures by governments to encourage employers to recruit or host apprentices were not universal. Four of the seven reported such schemes, although in China the government only provided subsidies for enterprises new to apprenticeships. However, China reported that industry associations also assisted. The Swiss and English presentations were silent on the topic of employment subsidies, and the United States reported only the continuation of existing incentives.

4.2. Research findings on COVID and after from Australia and England

This section provides more detail on the COVID measures in the two systems and adds post-COVID provisions. It begins with a short overview of the two apprenticeships systems.

4.2.1. Overview of the two systems

The apprenticeship systems in Australia and EnglandFootnote3 are reasonably similar, with both showing expansion periods during the 1980s and 1990s, extending apprenticeship opportunities beyond traditional masculinised crafts and trades, typically into retail, hospitality and business in the first instance. In Australia the more recently introduced apprenticeships are known as ‘traineeships’Footnote4 (Smith Citation2010), but in England the one term covers both more traditional and newer apprenticeship programs, although at one time the newer apprenticeships were known as ‘modern apprenticeships’ (Unwin and Wellington Citation1995). In Australia, there are far greater numbers of men than women in the system, partly because masculinised occupations have longer training periods, three or four years compared with one or two years for feminised occupations, but even looking at commencements only, men outnumber women approximately 3 to 2 or more (National Centre for Vocational Education Research Citation2023). In England, by contrast, participation by males and females is almost equal. Both systems have substantial numbers of adults undertaking apprenticeships, and both countries make apprenticeships available to people who are already working for the employer with whom they take up an apprentice contract; although funding restrictions apply in both countries for such people.

shows the top five apprenticed occupations in Australia and England. 2018 figures have been used to represent underlying features and avoid any distortion by pandemic effects. The leading industry areas for apprenticeships are not dissimilar in the two countries, although Australia has a much great concentration in construction occupations, and England in business and administration (although the categories do not neatly align). In both countries, apprentice commencements had been declining up until 2018 (Smith Citation2022).

Table 2. Top five apprentice areas in Australia and England, 2018 figures.

4.2.2. Australia

Specifically in Australia, apprentices (the collective term will be used in this paper to incorporate people in traineeships), are awarded VET (vocational education and training) qualifications, which they study at public or private VET providers. They are formally employed and are generally paid less than a comparable worker of the relevant age. The eight State and Territory governments) fund the off-the-job training, and maintain registers of apprentice contracts. The Federal (known as ‘Commonwealth’) government provides commencement and completion incentive payments for employers plus extra subsidies for identified ‘skill need’ industries and for employing people from designated equity groups; and minor funding schemes for apprentices themselves (for example the ‘living away from home allowance’), but pre-COVID, there were no standard apprentice wage subsidies. Approximately 10% of apprentices are employed by ‘Group Training Organisations’ which are intermediary organisations providing a form of ‘labour hire’ to take administrative burdens from employers (Smith Citation2019).

4.2.3. Apprenticeship responses to COVID in Australia

The June 2020 apprentice statistics, maintained by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), showed an immediate decrease of 3.9% in ‘in training’ figures for the quarter compared with June 2019, with only 266,000 apprentices in training, the lowest number since 1999. In the end, there were only 118,000 commencements during 2020, the lowest since 1997. In fact the 2019 apprentice figures had been very similar to the late 1990s figures, due to a precipitous decline in apprentice commencements from 2012 to 2019. (Smith Citation2021).Footnote5

Analysis of government websites showed that there were four main measures to maintain apprenticeship numbers:

An ‘Apprentice and Trainee Re-Engagement Register’ connecting displaced apprentices and trainees with employers. This was available to anyone who had been employed as an apprentice or trainee between March and June 2020, and was coordinated by the National Apprentice Employment Network (NAEN) – the peak body of Group Training Organisations (NAEN Citation2020).

The ‘Supporting Apprentices and Trainees’ (SAT) initiative enabled employers with fewer than 20 employees to receive a 50% wage subsidy when retaining a displaced apprentice or trainee who had been employed in March 2020, or employing a newly-displaced apprentice. In July 2020, the SAT was extended to medium size businesses, and the subsidy was made available until March 2021, for small and medium businesses. The SAT was expected to cover around 180,000 apprentices.

Attention then turned to commencements rather than just retention. A 50% wage subsidy, the Boosting Apprenticeship Commencements (BAC) program, was made available to anyone taking on a new or recommencing apprentice; the subsidy would apply for up to 12 months, and there was a financial ceiling per quarter per apprentice. The BAC began in 2020 and was later extended and expanded in May 2021, and then extended again to 2022. The program was closed to new entrants in June 2022, with no payments to be made after June 2023.

Finally, a program called ‘Completing Apprenticeship Commencements’ (CAC) provided a 10% subsidy for wages of an apprentice who had been employed under ‘BAC’, reducing to 5% in the third year. It applied to any type of employer, and was available until June 2025, to cover the four-year term of traditional trade apprentices employed under BAC.

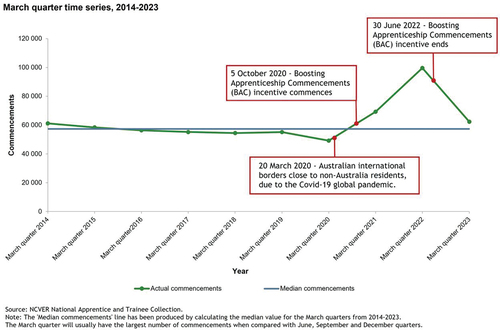

As a result of these measures, NCVER statistics show that by 2022 there were 264,000 apprentice commencements, the highest since 2012. 2012 had shown a temporary peak of commencements due to an upcoming funding change (Smith Citation2022).

Australian apprenticeship commencement figures from 2014 to 2023 clearly show the effects of the pandemic and of the financial incentives (). The diagram, supplied by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research, shows the immediate and substantial effects of the introduction and phasing out of the Boosting Apprenticeship Commencements (BAC) incentive.

In Australia there have been, for some decades, minor financial incentives for employers who take on apprentices, at commencement and upon completion, and also minor payments for apprentices. But wage subsidies had never previously been a feature of the apprenticeship system. In July 2022, however, when most of the payments apart from the minor CAC payment ceased, an announcement was made of a new form of wage subsidy. Occupations on the ‘Australian Apprenticeships Priority List’, a list previously used only, in apprenticeships, for the purposes of allocating funding levels for training, became eligible for wage subsidies to the employer. The subsidies were 10% of wages for the first two years, and 5% for the third year of employment, with maximum caps set. In addition, individual apprentices on the occupations list could receive a ‘support payment’ of up to $5000 AUD for the first two years. The occupations on the list comprised those under the umbrellas of ‘Technicians and trade workers’ and ‘Community and Personal Services’ workers.Footnote6 Employers of apprentices whose occupations were not on the list could only claim a hiring incentive of up to $3500 AUD for one year only, and no payments were available to apprentices themselves in these occupations. In addition, the institution of new infrastructure projects in Australia, such as a ‘Big Build’ project in the State of Victoria, with a strong employment focus, which could be continued during the pandemic as the work was primarily outside, often included minimum requirements for the employment of apprentices.

In off-the-job training, the most common response to COVID was a move to online training by training providers – TAFE (Technical and Further Education), the public provider, and private training providers. There were no especial national government measures to assist training providers, although most needed to undertake rapid upskilling of their teaching staff, and needed to assist apprentices, along with other students, who lacked access to digital infrastructure. State governments provided some assistance, and also provided some exceptions during periods of lockdown for VET teachers to attend their workplaces. Practical classes were postponed as much as possible, leading to delayed apprentice completions.

4.2.4. Apprenticeship responses to COVID in England

As elsewhere, there was a sharp and sudden downturn in apprentice commencements in England. Even by April 2020, apprenticeship commencements were reduced compared with the previous year, and a third of apprentices were ‘furloughed’. A Sutton Trust survey showed that employers reported problems with training providers closing, with apprentices not being able to work from home because of the nature of their work, and a proportion not having appropriate internet connections or computers (Doherty and Cullinane Citation2020).

The English government’s responses can be divided into those related to training and those related to employment. Government web sites showed that employment related responses included:

Employment incentives for business to recruit new apprentices. From August 2020, 1500 U.K. pounds was provided for employing a new apprentices aged 25 and over, and 2000 U.K. pounds for a younger apprentice. From June 2021 the rate was increased to 3000 pounds for each new apprentice;

The application of the general ‘furlough’ scheme to apprenticeships;

During 2020 and 2021, apprentices could take more than the pre-COVID allowable 4 weeks’ break from training, during which time they were not required to complete any training activities.

Breaks between employment contracts could be more than the normally-allowable 30 days if the break was due to COVID.

Electronic signatures were accepted on apprentice employment-related documents

Many of these employment-related measures were ‘switched off’ on 31 December 2021.

As a result of the employment measures, apprentice numbers reached pre-pandemic levels in 2021–2022 but fell again in 2022–2023, possibly due to the ‘switching off’ of the incentives in December 2021 (House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee Citation2023).

Training-related responses (Lawes Citation2023) included flexibilities around assessment methods, timing, and locations to address COVID-related barriers; and the formation of special taskforces to undertake ‘end point assessments’ for 150 apprenticeship qualifications, so that apprentices could qualify. There was also relaxation of rules around the requirement to complete English and Maths qualifications; apprentices were allowed to show equivalent learning, and did not need to complete the qualifications.

Government web sites show changes in assessment methods included apprentices being able to undertake tasks in simulated environments, and being able to undertake exam online instead of on paper. ‘Gateway’ sign-offs, where the employer and training provider sign off the apprentice as being ready for an ‘end point assessment’, were allowed to be undertaken remotely instead of face to face.Footnote7 These web sites were progressively updated over time, with provisions being added or removed. Three of the total ten assessment-related flexibilities were ‘switched off’ at the end of March 2022, but seven were retained to be used if desired.

5. Discussion

The findings show that most countries were undertaking measures to maintain apprenticeship numbers and, to a lesser extent, the integrity of apprentice training. Concerns during the early months of COVID included potential youth unemployment, and future skill shortages due to lower numbers and to apprentices not completing their studies. Less attention was paid to training matters, and where it was, it related to off-the-job training. By mid-2023, with the pandemic under control, labour shortages became a major concern. The case studies of Australia and England show that employment-related measures were largely wound down once the main two years of the COVID crisis ended, except for the retention of a residual wage subsidy in Australia. At the time of the INAP conference presentations in 2021, the pandemic was still ongoing, and therefore the country presentations did not provide data about post-COVID. However, later information about Germany from Fassbender (Citation2022) shows that that the ‘Maintaining training places’ program (see ), for example, was extended from mid-2021 to medium businesses (up to 499 employees) and that ‘short-time work’ due to the pandemic was legitimatised.

5.1. What do the findings show about the multiple purposes of apprenticeship?

(Smith Citation2018) depicts the multiple functions of apprenticeships in national systems: youth employment, enterprise skill formation, national skill development, innovation, and training for innovation. Smith (Citation2018) suggests that an over-emphasis on one function could lead to a lessening of effectiveness in another function; so, for example, an over-emphasis on its role in assuring youth employment could lead to an under-achievement in training for innovation or in enterprise skill formation.

In the COVID crisis it was evident that governments prioritised the youth employment function of apprenticeship; shows that this emphasis was likely also to have an inclusivity function and also a national skill development function. In Germany, Klassen and Schmees (Citation2023) have shown, through an analysis of debates in the Bundestag, that the apprenticeship system was regarded during the pandemic as crucial both for youth employment and for economic strength. In Australia, and to a lesser extent in England, during COVID the governments actively created jobs through a mechanism (i.e. through apprenticeship) that was seen as a legitimate role of government, in a way that a blanket job-creation (as opposed to job-retention) scheme would not have been. It could be argued that ‘training for innovation’ fell by the wayside but other functions may not have been adversely affected, although it was argued in Australia by the National Apprentice Employment Network that the early massive funding provisions of the ‘BAC’ program lessened the appeal of specific targeted funding for equity groups, i.e. the ‘inclusivity’ goal in . Enterprise skill formation was not regarded as of major importance during the pandemic, but came to the fore, at least in Australia and for some industry areas, in the post-pandemic wage subsidies for occupations on the Australian Apprenticeships Priority List.

5.2. How might apprenticeship systems improve as a result?

In the literature review, a number of shortcomings and criticisms of apprenticeship systems were discussed. The potential effects of COVID and COVID measures are now discussed.

Gender and occupational prestige: It has been shown that apprenticeships in some occupations are less valued than those in others, and that the more prestigious occupations are generally masculinised. The findings indicate that COVID support measures were not applied to specific occupations and therefore did not have differential effects, except that some feminised workplaces (e.g. retail, hairdressing) were more likely to be closed, and that infrastructure support projects provided work in masculinised occupations. The most recent extension of post-COVID apprentice wage subsidies in Australia, however, does signal a return to occupational discrimination, with occupations on the Australian Apprenticeship Priority list receiving far great subsidies than others, both for employers and for apprentices; a 2024 expansion of the list goes some way to address the relative underrepresentation of feminised occupations. Post-COVID labour shortages in many masculinised occupations have led to encouragement to women to enter masculinised apprenticeships, as noted by Gonon (Citation2023), and the topic of a current 2024 Australian government consultation,Footnote8 rather than to an equalisation of respect for feminised occupations.

Privatisation in apprenticeship systems and VET: As mentioned earlier, private companies are involved both in the delivery of training and in apprenticeship management and support functions. One feature of the COVID pandemic was that profiteering was common (Avis et al. Citation2021; Kondilis and Benos Citation2023), illustrating the concept of ‘disaster capitalism’ promulgated by Klein (Citation2007). In Australia, a reported ‘hotchpotch of public and private providers’ (Faruqi Citation2020) was involved in health provisions, and the ineffectual management of hotel COVID quarantine for incoming travellers was undertaken by private security firms (Coate and Hon Citation2020). Private profits from apprenticeship measures, however, have been little explored, either during or since the pandemic.

Two Australian examples follow. Firstly, private intermediary companies called ‘ASNs’ (Apprenticeship Support Network providers) receive a fee for every apprentice sign-up, and they were predictably active in trying to encourage companies to take on apprentices. Starting with the BAC wage subsidies, and then into the CAC period, a major employment services provider and ASN provider, Sarina Russo, advertised the CAC subsidies heavily on its web site under the heading ‘Boost your business with a government wage subsidy’.Footnote9 Secondly, it was discovered in 2021 that an anomalous number of apprentices who were existing workers studying at Diploma and above were recruited under the BAC program. The proportion of ‘existing workers’ in apprenticeships from the final quarter of 2019 to the final quarter in 2020 increased by 470%, compared with an increase in other new apprentices of 97%. The government moved very quickly to close the loophole, tightening the numbers and types of existing workers for whom companies could claim the subsidy. The author was unofficially told that it was private training providers, who would benefit from the funding for training, who had been encouraging employers to access the wage subsidies, but there has been no public discussion of the events.

Apprentice numbers and attractiveness: The research showed that the use of apprenticeships as a labour market program meant that apprentice numbers in the two case study countries, Australia and England, revived to pre-pandemic numbers. In Australia, numbers continued to rise post-pandemic but in England this did not occur. The difference could be the continuation of wage incentives in Australia, compared with their ‘switching off’ in England. It might have been supposed that the availability of apprentice jobs, in the absence of other alternative jobs, might have increased the standing of apprenticeship, but no evidence is yet available on this matter.

6. Conclusion

Klassen and Schmees (Citation2023) have noted few calls from German politicians for changes to the apprenticeship system. Continuity rather than change was the general thrust in Australia and England too, apart from the wage subsidy innovation in Australia, and the general agreement on the need for digital upskilling that had been noted at the commencement of the pandemic ( and ILO Citation2021b). Indeed the success of apprenticeship support measures may have entrenched what may be described as the conservativism of apprenticeship systems. For example, the continuation of the wage subsidy in Australia confirmed the preferential treatment of masculinised occupations since the subsidy was confined to occupations on a gendered ‘skills priority’ list. Incremental change and improvement may result, for example in the continuation of some of the assessment flexibilities in England. The rapidly occurring abuse of the early and probably over-generous wage subsidies has provided a salutary policy lesson in Australia.

It is interesting to reflect that, in both Australia and England, it was only because of the expanded apprenticeship systems (albeit with declining numbers of participants pre-pandemic) that governments were able to use apprenticeship levers to retain and expand employment. The ‘multi-sector, social inclusion approach to apprenticeships’ criticised by Fuller and Unwin (Citation2003) proved its worth during the pandemic, for workers and employers alike.

There is an opportunity to reframe policy and academic debates on apprenticeships. However, to do so, more systematic research is needed on post-COVID apprenticeship systems. The considerable work undertaken by international bodies such as the OECD and ILO on COVID’s effects on apprenticeship needs to be followed up by systematic study on the post-COVID era and the potential learning from the pandemic.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people who spoke to me about the topic and/or sent information:

In Australia: Dianne Dayhew, Carl Walsh, Peta Skujins, Chris Ratcliffe, Kim Budgen, Angela Tidmarsh.

In England: Tom Bewick, Richard Marsh, Tanya Lawes, Shona Hutton, Karl Anderson.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The presentations can be accessed at https://www.voced.edu.au/special-collections-key-conferences

2. Chankseliani, Keep and Wilde (Citation2017) do not cover Asian countries in their analysis, hence there is no size information for China in the table.

3. While England is part of the U.K., in the U.K., apprentice systems vary among the constituent countries, unlike general labour market provisions, as apprenticeships are seen as part of education, which is devolved to each country. This paper examines the English apprenticeship system, since England is the largest country.

4. In England, the word ‘traineeship’ has a different meaning, and is not part of the apprenticeship system.

5. Since there had been considerable labour force growth in the two decades, the proportion of the labour force in apprenticeships dropped considerably from 1999 to 2019.

6. The list was expanded on 1 January 2024 to a wider range of occupations; see https://ministers.dewr.gov.au/oconnor/2024-australian-apprenticeship-priority-list

9. The web site was still active even in May 2024: https://www.sarinarusso.com/apprenticeships/resources/boost-your-business-with-government-wage-subsidies/completing-apprenticeship-commencements-wage-subsidy

References

- Avis, J., L. Atkins, B. Esmond, and S. McGrath. 2021. “Re-conceptualising VET: Responses to COVID-19.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 73 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/13636820.2020.1861068.

- Birch, E., and A. Preston. 2022. “The Australian Labour Market in 2021.” Journal of Industrial Relations 64 (3): 327–346. doi:10.1177/00221856221100387.

- Bridgford, J. 2017. Trade Union Involvement in Skills Development: An International Review. Geneva: ILO.

- Cedefop. 2017. Cedefop European Public Opinion Survey on Vocational Education and Training. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Chan, S. 2021. “Supporting ‘Learning by Doing’ When Access to Authentic Learning Becomes Disrupted.” People, Place and Time: Developing the Adaptive VET Teacher, Seventh Annual ACDEVEG Conference on VET teaching and VET Teacher-education, online, December 8. https://www.acde.edu.au/acdeveg-conference-2021/

- Chankseliani, M., E. Keep, and S. Wilde. 2017. People and Policy: A Comparative Study of Apprenticeship Across Eight National Contexts. Doha: WISE Research.

- Coate, J., and The Hon. 2020. “COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry: Final Report and Recommendations, Vols I and II.” Melbourne: Victorian Government. https://www.quarantineinquiry.vic.gov.au/

- Commission for Children and Young People. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Young People: Education. Melbourne: Commission for Children and Young People.

- Dale, R, T O’Rourke, E Humer, A Jesser, P. Plener, and C. Pieh. 2021. “Mental Health of Apprentices during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria and the Effect of Gender, Migrant Background and Work Situation.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (17): 8933. doi:10.3390/ijerph18178933.

- Deissinger, T. 2017. “VET and Universities in the German Context – Substitutes or Complements? A Problem Analysis.” Modern apprenticeships: Widening their scope, sustaining their quality. 7th INAP Conference, Washington DC, United States, October.

- Doherty, D., and C. Cullinane. 2020. COVID-19 and Social Mobility Impact Brief #3: Apprenticeships. London: Sutton Trust.

- Duemmler, K., and I. Caprani. 2017. “Identity Strategies in Light of a Low Prestige Occupation: The Case of Retail Apprentices.” Journal of Education and Work 30 (4): 339–352. doi:10.1080/13639080.2016.1221501.

- Eurofound. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on Young People in the EU. Luxembourg: Eurofound.

- Faruqi, O. 2020. “Radio Broadcast.” https://7ampodcast.com.au/episodes/exclusive-brett-suttons-leaked-call, 14 September.

- Fassbender, U. 2022. “Collective Skill Formation Regimes in Times of Covid-19: A Governance-Focused Analysis of the German Dual Training System.” International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training 9 (2): 167–194. doi:10.13152/IJRVET.9.2.2.

- Fuller, A., and L. Unwin. 2003. “Creating A ‘Modern’ Apprenticeship: A Critique of the UK’s Multi-Sector, Social Inclusion Approach.” Journal of Education and Work 16 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1080/1363908022000032867.

- Gekara, V., D. Snell, P. Chhetri, and A. Manzoni. 2014. “Meeting Skills Needs in a Market-Based Training System.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training 66 (4): 491–505. doi:10.1080/13636820.2014.943800.

- Gessler, M. 2017. “The Lack of Collaboration Between Companies and Schools in the German Dual Apprenticeship System: Historical Background and Recent Data.” International Journal for Research in Vocational Education & Training 4 (2): 164–195. doi:10.13152/ijrvet.4.2.4.

- Gessler, M. 2019. “Concepts of Apprenticeship: Strengths, Weaknesses and Pitfalls.” In Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, edited by S. McGrath, M. Mulder, J. Papier, and R. Suart, 677–709. Switzerland: Springer.

- Gonon, P. 2023. “‘Women in the Playpen’: Female Role Models and Swiss Vocational Education.” Work-o-Witch: Observations on work, employment and education. https://work-o-witch.at/en/

- Guthrie, H., E. Smith, S. Burt, and P. Every. 2014. “Review of the Effects of Funding Approaches on Service Skills Qualifications and Delivery in Victoria.” Melbourne: Service Skills Victoria. http://behc.com.au/REPORT.pdf

- Halder, K., E. Humer, C. Peih, P. Plener, and A. Jesser. 2022. “Burdens of Apprentices Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic and How They Dealt with Them: A Qualitative Study Using Content Analysis One Year Post-Breakout.” Healthcare 10 (11): 2206. doi:10.3390/healthcare10112206.

- House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee. 2023. Post Pandemic Economic Growth and U.K. Labour Markets. London: House of Commons.

- Hurley, P. 2020. Impact of Coronavirus on Apprentices and Trainees. Melbourne: Mitchell Institute, Victoria University.

- ILO. 2020. A Global Survey of Enterprises: Managing the Business Disruptions of COVID. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2021a. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh ed. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2021b. Skills Development in the Time of COVID-19. Taking Stock of the Initial Responses in TVET. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2021c. Skilling, Upskilling and Reskilling of Employees, Apprentices and Interns during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geneva: ILO.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2022. Policy Brief: Policy Sequences during and after COVID-19. Geneva: ILO.

- Kiss, A, M. Morandini, A Turrini, and A. Vaneplas. 2022. Slack and Tightness: Making Sense of Post COVID-19 Labour Market Developments in the EU. Brussels: European Commission.

- Klassen, J., and J. Schmees. 2023. “The Dual Apprenticeship System in Crisis? A Discourse Analysis of Parliamentary Debates in Germany during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The context & purpose of VET: Journal of Vocational Education & Training conference, Oxford, 19-21 July.

- Klein, N. 2007. The Shock Doctrine. London: Allen Lane.

- Kondilis, E, and A Benos. 2023. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Private Health Sector: Profiting without Socially Contributing.” International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services 53 (4): 466–477. doi:10.1177/27551938231201070.

- Krumel, T., C. Goodrich, and N. Fiala. 2023. “Labour Demand in the Time of Post-COVID-19.” Applied Economics Letters 30 (3): 343–348. doi:10.1080/13504851.2021.1985067.

- Lawes, T. 2023. “Apprenticeship Assessment in England: The Lasting Impact of COVID-19.” The context & purpose of VET: Journal of Vocational Education & Training conference, Oxford, 19-21 July.

- Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS). 2013. Apprenticeship Training Agency Model: An Independent Review of Progress, Prospects and Potential. London: LSIS.

- Markowitsch, J., and W. Wittig. 2020. “Understanding Differences between Apprenticeship Programmes in Europe: Towards a New Conceptual Framework for the Changing Notion of Apprenticeship.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74 (4): 597–618. doi:10.1080/13636820.2020.1796766.

- Mayhew, K., and P. Anand. 2020. “COVID-19 and the UK Labour Market.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (1): S215–S224. doi:10.1093/oxrep/graa017.

- McLaren, S, E Green, M Anderson, and M. Finch. 2023. “The Importance of Active-Learning, Student Support, and Peer Teaching Networks: A Case Study from the World’s Longest COVID-19 Lockdown in Melbourne, Australia.” Journal of Geoscience Education 1-15, online, August. doi:10.1080/10899995.2023.2242071.

- National Apprenticeship Employment Network (NAEN). (2020). Annual Report 2019-2020. Canberra: NAEN. https://naen.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NAEN-2020-Annual-Report.pdf

- National Centre for Vocational Education Research. 2023. “Databuilder, Apprentices and Trainees.” https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/data/databuilder

- National Skills Commission (NSC). 2022. “2022 Skills Priority List: Key Findings Report.” National Skills Commission, Canberra. https://www.nationalskillscommission.gov.au/topics/skillspriority-

- Newton, O. 2021. “Degree Model Apprenticeships.” New Zealand Vocational Education and Training Research Forum, online, September 8-9.

- Newton, B., A. Hirst, and L. Miller. 2019. “Editorial: How Do We Solve a Problem like Apprenticeships?” International Journal of Training & Development 23 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12147.

- OECD. 2018. Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2020a. OECD Economic Outlook, June 2020. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2020b. VET in a Time of Crisis: Building Foundations for Resilient Vocational Education and Training Systems: Policy Brief. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2022a. The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2022b. The Post-COVID-19 Rise in Labour Shortages. Paris: OECD.

- Phillips KPA. 2018. Apprenticeships Post 2020: National Apprenticeship Forums 2017-18. Hawthorn East, Vic: Phillips KPA. May.

- Ray, N. 2023. Independent Evaluation of the JobKeeper Payment. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2023-455038

- Richmond, T., and E. Regan. 2021. No Train, No Gain. An Investigation into the Quality of Apprenticeships in England. London: EDSK. https://www.edsk.org/publications/no-train-no-gain/

- Safaei, J., and A. Saliminezhad. 2022. “The Covid-19 Pandemic Economic Impacts and Government Responses across Welfare Regimes.” International Review of Applied Economics 36 (5–6): 725–738. doi:10.1080/02692171.2022.2100329.

- Saha, A., M. Carreras, and E. Quak. 2022. “Investigating Initial Policy Responses to COVID-19: Evidence across 59 Countries.” International Review of Applied Economics 36 (5–6): 762–791. doi:10.1080/02692171.2022.2130187.

- Schoon, I., and A. Mann. 2020. “School-to-Work Transitions during Coronavirus: Lessons from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.” OECD Education and Skills Today, May 19.

- Siekmann, G., and M. Circelli. 2021. Industry’s Role in VET Governance: Using International Insights to Inform New Practices. Adelaide: NCVER.

- Smith, E. 2010. “Apprenticeships.” In International Encyclopedia of Education, Third edition. Vol. 8. edited by P. Peterson, B. McGaw, and E. Baker, 312–319. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Smith, E. 2018. “Revisiting Apprenticeships as a Response to Persistent and Growing Youth Unemployment.” In Skills and the Future of Work: Strategies for Inclusive Growth in Asia and the Pacific, edited by A. Sakamoto and J. Sung, 160–179. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Smith, E. 2019. Intermediary Organizations in Apprenticeship Systems. Geneva: International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/skills/pubs/WCMS_725504/lang–en/index.htm

- Smith, E. 2021. “The Expansion and Contraction of the Apprenticeship System in Australia, 1985-2020.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training 73 (2): 336–365. doi:10.1080/13636820.2021.1894218.

- Smith, E. 2022. “Expanding or Restricting Access to Tertiary Education? A Tale of Two Sectors and Two Countries.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 27 (3): 500–523. doi:10.1080/13596748.2022.2076059.

- Smith, E., J. Tuck, and K. Chatani 2018. ILO Survey Report on the National Initiatives to Promote Quality Apprenticeships in G20 Countries. Geneva: International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/WCMS_633677/lang–en/index.htm

- Tang, K. 2023. “Impacts of COVID-19 on Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Education: A Comprehensive Review and Recommendations for Educational Practices.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 22 (1): 23–61. doi:10.1007/s10671-022-09319-y.

- Trimboli, D., M. Lees, and S. Zhang. 2023. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on VET. Adelaide: NCVER.

- Unwin, L., and J. Wellington. 1995. “Reconstructing the Work-based Route: Lessons from the Modern Apprenticeship.” The Vocational Aspect of Education 47 (4): 337–352. doi:10.1080/0305787950470401.

- Vacchiano, M. 2022. “How the First COVID-19 Lockdown Worsened Younger Generations’ Mental Health: Insights from Network Theory.” Sociological Research Online 28 (3): 884–893.

- Wolf, A. 2002. Does Education Matter? Myths about Education and Economic Growth. London: Penguin.