Abstract

Aims

The purpose of this research was to understand the experience of older adults who completed an 8-week cervical spine home exercise program (HEP) designed to reduce visual reliance for postural stability, potentially impacting fall risk.

Methods

Nineteen older adults completed a semi-structured, one-on-one interview. Qualitative verbatim data from one open-ended prompt, “Tell me about your experience with the home exercise program,” were analyzed using an inductive, emergent approach.

Results

Eleven subthemes emerged within two overarching themes: motivational factors and perceived barriers. Two subthemes within the motivational factors category aligned with the Self-Determination Theory (SDT): autonomy and competence, impacting motivation. Participants reported a positive HEP experience despite the perceived barriers of time and commitment required for HEP completion.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the experiences of older adults participating in an HEP and highlights the importance of considering their fundamental psychological needs when designing HEPs, impacting motivation and adherence.

Introduction

According to the National Institutes of Health, the population aged 65 and over is defined as older adults.Citation1 Older adults have been identified as one of the most rapidly growing populations in the United States (U.S).Citation2 It is expected, by 2030, that 60% of the population will have more than one chronic condition, with older adults being the group at the highest risk.Citation2 Therefore, health-care efforts that promote healthy and active aging in older adults are warranted. The World Health Organization defines active aging as “the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation, and security to enhance the quality of life as people age.”Citation3 Physical therapists have an important role in assisting older adults achieve optimal health and function. The most recent analysis of practice in physical therapy indicated that 40–43% of patients/clients receiving physical therapy care across diverse practice settings are older adults.Citation4 Older adults are expected to comprise a significant portion of patients/clients that will seek various medical services, including physical therapy, as the U.S. population continues to age.Citation4

Home exercise programs (HEPs) are effective in improving the quality of life of older adults. In a randomized clinical trial conducted by Ambrose et al.Citation5, HEP reduced the rate of subsequent falls in community-dwelling older adults. Also, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, individualized HEPs decreased the number of fallers and led to significant improvements in balance, physical activity, and function in older adults residing in community settings.Citation6 However, the effectiveness of HEPs can be influenced by suboptimal adherence levels. A research study indicated that the adherence level for home-based fall prevention programs was initially 82% over 10 week but decreased to approximately 52% after 12 months.Citation7 Patients require a behavioral change to adhere to exercise programs. A systematic review documented several factors which enhance adherence to HEPs.Citation8 These factors include strong social support and guidance from physiotherapists, limiting number of exercises prescribed (<4), high levels of self-motivation and self-efficacy, and reduced impact of psychological influences such as helplessness, depression, and anxiety.Citation8 Additionally, a scoping review revealed similar factors which underpin the success of behavioral modification.Citation9 These factors encompass an individual’s capability (physical or psychological factors), opportunities (physical, social, or institutional factors), and/or motivation (impulsive or reflective factors).Citation9

Understanding the experiences of older adults engaging in HEPs is vital for gaining insights into the barriers and facilitators that impact their adherence to HEPs. Moreover, this understanding is essential for the development of intervention programs tailored to the specific needs of older adults and the enhancement of evidence-based practice in physical therapy. Published editorials underscore the significance of qualitative research for physical therapists in this regard.Citation10,Citation11 Previous studies have investigated the experiences of older adults with various HEPs designed to reduce the risk of falls.Citation12,Citation13 However, no previous research has explored the experiences of older adults participating in an HEP that was specifically aimed at reducing visual reliance for postural stability. Such understanding may offer new perspectives on enhancing older adults’ rehabilitation experience. The purpose of this exploratory qualitative study was to understand the experiences of the older adults who participated in a physical therapy cervical spine HEP that was intended to reduce visual reliance for postural stability and, potentially, reduce the risk of falls.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study design was exploratory, with qualitative data used to gain insight into the lived experiences of older adults who took part in a cervical spine HEP. To achieve this goal, a phenomenological research approach was applied using qualitative interview data after participant completion of the 8-week HEP. The theoretical framework entailed the constructivist approach, which assumes that an individual’s interpretation and meaning of circumstances is anchored in their own experience.Citation14

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guide was used to ensure qualitative study rigor (Supplementary material).Citation15

This qualitative study was conducted as part of a single-group pretest post-test quantitative study aimed at examining the effects of a HEP that incorporated cervical spine exercises on visual reliance for postural stability and cervical active range of motion in older adults. The HEP consisted of chin-tuck exercises designed to stretch the upper neck extensors and strengthen the deep neck flexors and a scapular retraction exercise for strengthening the shoulder retractors. The scapular retraction exercise included two components: the activation component and the strengthening component. Participants were recruited via flyers, e-mails, and word of mouth. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) older adults aged 65–79 years old; (2) living independently; (3) not using any assistive devices for walking; (4) showing interest in improving posture and postural stability. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) neurologic deficits; (2) disorders causing dizziness; (3) history of neck surgery; (4) any falls in the past six months; (5) administration of medications that could cause frequent dizziness; (6) received health care for neck, shoulder, or back for the past 12 months; (7) moderate to severe neck pain (>3.4 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)). Overall, 19 participants were recruited and individually completed the HEP over an 8-week period. Along with the HEP, participants were provided with behavioral modification instructions to promote the maintenance of an upright posture when sitting, standing, and during daily activities. To improve HEP adherence, participants were provided with comprehensive instructional handouts and an exercise log to document their completed exercises, and they received daily text messages encouraging them to perform their HEP and maintain an upright posture.

Author reflexivity

The authors involved in the qualitative data collection and analysis acknowledge the intrinsic influence of positionality. The first author, who is involved in data collection and data analysis, MJ, is a 38-year-old Caucasian female and a physical therapy doctor of philosophy (PhD) student with experience as a graduate assistant in research and statistics. Exposure to various research concepts and designs has played a significant role in broadening her understanding of research. Her identity as a physical therapist working with geriatric patients impacted her research interest and design. Her additional interest in deeper insights and meanings with the patient’s physical therapy experience impacted her choice to engage in qualitative research. The second author involved in planning qualitative data collection and data analysis, GG, is a 51-year-old Caucasian female and a professor at a parochial university. She is a doctor of physical therapy and has a doctorate of education. Research interest and design were impacted by the identities of practicing clinicians and professors with an interest in effective education and learning. Her previous experience with qualitative research and desire to understand the lived experiences of others affected the research design. Additionally, middle age may provide a unique vantage point in understanding and interpreting the attitudes and practices of participants. For both authors, the intersecting facets of identity inform perspective potentially impacting study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Attunement to how background intersects with the experiences and perspectives of participants is acknowledged as an integral aspect of the research process. Two authors, one male professor (EJ) and one female statistician (ND), worked on study design and manuscript editing; however, they did not complete qualitative data analysis. The additional authors assisted in the study design and quantitative data collection for the associated study and manuscript editing. The authors did not have relationships with participants prior to the initiation of the study. Participants did not know about the personal goals of the authors; however, they were aware that this study was part of a PhD project.

Participants

The purpose of the qualitative study and its interview process were clearly explained in the consent form, which was used for both the quantitative and qualitative studies. After completing the 8-week HEP, participants were reminded of the qualitative study’s purpose and were given the opportunity to reaffirm their willingness to participate. All 19 participants who successfully completed the HEP agreed to take part in this study. Recruitment for this study involved a convenience sample from the U.S.

Data collection

A semi-structured one-on-one interview was conducted by a single researcher (MJ) with guidance and training from GG. The face-to-face interviews occurred on campus in a quiet physical therapy lab, with only the participants and researchers present during the data collection. An interview guide comprising six open-ended questions (as shown in Appendix A) was utilized. Pilot testing of the interview questions was not conducted prior to data collection. All participants were asked the same questions, and the semi-structured protocol enabled researchers to prompt participants to provide further elaboration on their responses. Interviews were conducted during the post-intervention session before the collection of final quantitative data. The interviews varied in duration, ranging from 5 to 12 min, and were recorded using an audio recorder, Otter application, version 3.34.230918.900. The interviews were not repeated, and field notes were not taken during the interviews. The application was installed on a smartphone that was locked to protect data. Numerical identifiers were used to keep data confidential. Subsequently, verbatim qualitative data was imported into a web-based platform for storing, organizing, and analyzing data, Dedoose 8.0.35 (2018). For this study, data analysis focused on exploring participants’ responses to the initial question: “Tell me about your experience with the home exercise program.” A previous systematic review indicated that studies using empirical data achieved saturation within a limited range of interviews (9–17).Citation16 In our study, the number of participants interviewed (19) exceeded this range, indicating that further recruitment was unnecessary.

Data analysis

An inductive, emergent approach was used for data analysis. The responses to the first statement in the interview guide were analyzed. The responses to this statement as a data source were chosen so that participants, without leading prompts, would share their uninfluenced impression of completing the HEP. The responses to the additional questions will be a data source for future research. Two researchers, MJ and GG, completed the initial data coding independently to increase trustworthiness. Meaningful phrases and statements were identified reflecting participants’ lived experiences when completing the cervical spine HEP. The coding tree was emergent as codes were not pre-determined. In an iterative process, the researchers met repeatedly to discuss code agreement, cross-check participants’ responses, and merge repetitive codes. Member checking was not completed as part of the data analysis.

Results

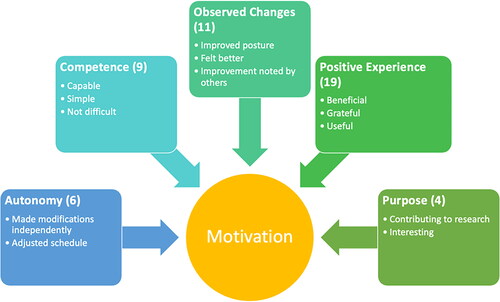

The study sample comprised of all 19 older adults with a mean ± SD age of 72.7 ± 3.4 years. Six (31.6%) participants were males and 13 (68.4%) were females. The study finding revealed 87 initial meaningful phrases, which were subsequently reduced to 27 codes. Codes were iteratively revisited, revealing 11 codes that supporting two main themes regarding the experience of completing the HEP. The two themes from qualitative data were motivational factors and perceived barriers to completing the HEP. Five subthemes, including autonomy, competence, purpose, positive experience, and observed changes, are presented in , supporting the theme of motivational factors with supporting examples. Also, displays the frequency of participants who mentioned each subtheme within their interview. presents five subthemes within the theme of motivational factors, along with their corresponding codes.

Table 1. Codes representing the theme of motivational factors with supporting excerpts.

The strongest subtheme supporting motivational factors from participants was the perception of a positive experience. Participants perceived that the HEP went well; some felt gratitude and reported that the HEP was helpful. Another prominent subtheme was perceived changes by participants. One participant stated, “I am feeling much better,” and another reported, “I am feeling good, emotionally and physically.” More than half of the participants experienced noticeable changes during the exercise program, and they perceived their experience as positive, impacting motivation. The statements “it wasn’t overly strenuous or anything” and “I think they were good. And, of course, they weren’t hard to do” reflects the subtheme of participant competence while completing the program. Six coded phrases represented autonomy as a motivational factor. Some participants reported self-directed behavior and independence in adjusting the HEP to meet individual needs. “I had better success during the exercises when I was at the pool because I could stand up and keep my head and back level” and “I had to alter my positioning because of pain” reflected their confidence in adjusting the HEP. Two of the subthemes related to the motivational factors theme, namely competence and autonomy, align with the self-determination theory (SDT).Citation17,Citation18

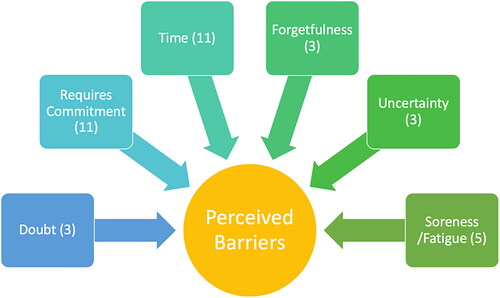

The second theme that emerged organically from data analysis was perceived barriers. Six subthemes, including time, uncertainty, doubt, requires commitment, soreness/fatigue, and forgetfulness, support the theme of perceived barriers and are displayed in with corresponding excerpts and the frequency of participants who noted each subtheme within their interview. displays six subthemes within the theme of perceived barriers, along with their corresponding codes.

Table 2. Codes representing the theme of perceived barriers with supporting excerpts.

Time and commitment were the most frequent subthemes for perceived barriers. A participant stated, “I began to feel very tedious about doing them. I felt like they took like too much time,” while another reported, “It was complicated for me in that I was traveling a lot.” Eleven phrases supported the subtheme of commitment. “Actually, it takes discipline, like I said, so you need to set up a time and a place.” Participants additionally reported that they sometimes forgot: “And after about three or four days, I couldn’t remember if I've done it once or twice or three times.” For some participants, soreness and fatigue were perceived barriers: “you have to persevere the discomfort, and I should say more, even some times pain.” The excerpt “I didn’t think it’s gonna work. Because the exercise is not like difficult is just too simple so I don’t believe that it’s gonna work” reflects the doubt three participants experienced. Overall, the qualitative data revealed two main themes: motivational factors and perceived barriers to completing the physical therapy HEP.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the experience of the aging adult during participation in physical therapy cervical spine HEP. The findings address the paucity of research on the experience of older adults participating in a home exercise program. Two themes arose from the open-ended statement “Tell me about your experience completing the home exercise program”: motivational factors and perceived barriers. Five subthemes supported the theme of motivational factors. Two of the motivational factor subthemes, competence and autonomy, align with the SDT, which describes needs that are required to be met for intrinsic motivation, which then impacts behavior change.

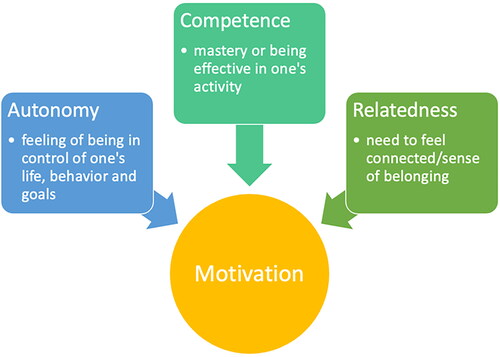

The SDT was proposed by Deci and Ryan in an attempt to understand human behavior and motivation.Citation17 According to the SDT, individuals are naturally driven toward growth and can become self-determined or intrinsically motivated when their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled.17 The self-determination theory is displayed in .

Autonomy pertains to an individual’s capacity to take action and exercise control over their own behaviors.Citation18 Competence refers to the feeling of mastering tasks and acquiring new skills.18 Relatedness signifies an individual’s need to experience a sense of connection and support from others.Citation18 If any of these needs is not fulfilled, it can have a detrimental effect on motivation.Citation17 The SDT distinguishes two types of motivation: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.Citation18 Intrinsic motivation is when individuals perform tasks because they are inherently enjoyable and satisfying.Citation18 Individuals who are intrinsically motivated actively seek challenges and novel experiences to foster learning and personal growth.Citation17 Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is when individuals feel pressured by external factors or do something to attain a separable outcome.Citation19 Different forms of extrinsic motivation exist with various degrees of autonomy.Citation17 The least autonomous form is externally regulated motivation characterized by task completion mainly to attain rewards or avoid punishment. The most autonomous form is integrated regulation, where individuals embrace external regulations and integrate them with their values and needs.Citation17 Facilitating the integration or internalization of external motivation by establishing favorable social environments that support individuals’ fundamental psychological needs can enhance well-being and promote positive behavior.Citation18,Citation20

Human behavior remains the most significant factor affecting healthcare outcomes, despite numerous recent advancements in healthcare delivery.Citation21 An individual’s health depends greatly on lifestyle factors that can be likely controlled by themselves, such as physical activity, diet, smoking, and hygiene. In addition, the effectiveness of most healthcare interventions is closely related to the individual’s adherence to activities that promote their well-being, such as medication adherence and changing unhealthy habits.Citation21 Thus, initiating and maintaining behavior change is fundamental to the prevention and treatment of many health problems. A meta-analysis conducted by Sheeran et al.Citation22 indicated that both autonomous motivation and perceived competency are pivotal targets for behavior change interventions. In a systematic review, exercisers who were provided with autonomous and competence support, experienced greater satisfaction regarding their basic psychological needs.Citation23 This aligns with the principles of SDT. Also, exercisers who actively participated in the decision-making process tended to sustain the exercise routines over extended periods.Citation23 Most health-related behaviors are not intrinsically motivated; thus, individuals who understand their value and benefits are more likely to adopt them.Citation21 Controlled extrinsic motivation is associated with short-term behavioral changes as opposed to long-term.Citation24 Therefore, facilitating intrinsic motivation will benefit physical therapists as they motivate patients by sharing the value of the behavior. Individuals also require a sense of competency to effectively perform given tasks. In this study, results indicated that participants experienced both autonomy and competency. This may partially explain participants’ dedication to the HEP, as, according to the SDT, individuals feel more intrinsically motivated when their basic psychological needs are fulfilled. In the quantitative portion of this study, the adherence level was 94%. One of the reasons older adults often prefer HEPs over group exercise programs is the sense of autonomy they experience with HEPs.Citation12 In contrast, autonomy was perceived as both a facilitator and a barrier to HEP adherence in another study.Citation25 Some older adults found the self-reliance required to adhere to HEP as challenging and undesirable.Citation25 Overall, the theme of motivation, with competency and autonomy subthemes, organically emerged when older adults were asked about their experience completing a HEP. Although each patient is unique, results provide insights into how physical therapists can promote HEP adherence by building on constructs in the self-determination theory for motivation in older adults.

Also, the theme of perceived barriers was revealed during data analysis. Insight regarding perceived barriers by older adults is significant for physical therapists to understand as they design HEPs. An unexpected finding was that older adults perceived a lack of time and the required commitment as a challenge to completing the HEP. Similarly, in another study, but with younger and middle-aged populations, participants also reported the lack of time as a main barrier to physical activity and exercise.Citation26 Additionally, irrespective of age and gender, lack of time is consistently reported to be the main obstacle to physical activity and exercise.Citation27 This is contrary to the belief that older adults generally have more available time than younger adults. These findings suggest that older adults have schedules that are busier than what is assumed or may undervalue and downplay adherence to HEPs. Consequently, physical therapists may need to emphasize education for older patients on the benefits of long-term adherence to HEPs to help them prioritize activities. Supporting this theory, a literature review examining older adults’ perspectives on fall risk and prevention programs reported that older adults were more likely to participate in interventional programs when they perceived them as advantageous to their health.Citation28 Other barriers reported by participants in this study were uncertainty and doubt. This reflects the importance of physical therapists’ meeting regularly with patients/clients to discuss the HEP and address uncertainty regarding exercise performance. Aligning with the current study, researchers exploring the factors hindering HEP adherence following discharge from physical therapy found that low outcomes expectation was a barrier negatively influencing HEP adherence.Citation29 As previously mentioned, exercise adherence increases when patients are aware of the benefits. Therefore, the expected benefits of each exercise should be presented while also avoiding unrealistic expectations, which can inadvertently reduce adherence.Citation30 In addition, it is important to disclose potential risks so patients are informed about all possible outcomes.Citation30 Soreness and fatigue are expected effects of exercises and were reported by participants in this study. If these expected side effects are severe or persist, reduced adherence may commence. This provides insight into the importance of regular assessment and modifications as needed to maintain HEP adherence.

Commitment to HEPs is essential for achieving physical therapy goals, and motivation for behavior can be explained by the principles of SDT.Citation24 As described earlier, individuals who possess a sense of autonomy or experience a less externally controlled motivation are more likely to perceive exercise behavior in a positive way.Citation24 According to a previous study, there are several strategies physical therapists can use to facilitate commitment and foster adherence to exercise programs. Some of these strategies include providing simple and less demanding instructions, addressing cognitive motivational factors, such as self-efficacy and health beliefs, offering social support and reinforcement, and providing reminders.Citation31 Forgetting to exercise is another obstacle to adherence to HEP, which was noted by three participants. Individuals may give more importance to obligations and responsibilities than health and well-being. In the current study, text message reminders encouraged continuity of exercise routine, which may have reduced the frequency of this perceived barrier subtheme. The theme of perceived barriers aligns with other studies that revealed patient-perceived barriers as a significant obstacle to exercise adherence.Citation32

This research study offers valuable perspectives on the experience of older adults who participated in a physical therapy HEP. It underscores the crucial role of addressing foundational psychological needs when implementing home programs, which influences motivation. Strategies to enhance motivation and reduce perceived barriers may contribute to the success of older adults when participating in physical therapy HEPs.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

This study had some limitations. The sampled population included participants who volunteered to participate and were potentially more interested in improving their posture and postural stability, contributing to their commitment to the implemented HEP. An additional limitation includes the timing of the interviews. Qualitative interviews were conducted during the post-intervention session prior to the final quantitative measurements. Some participants provided brief responses because of potential concerns related to the 90-min time frame required for the post-intervention session. A notable limitation was the absence of member checking to confirm the accuracy of recorded qualitative participants’ responses because of interviews occurring during the last scheduled session. Thus, study results may not apply to all older adults. In addition, the interview questions were not pilot-tested before the initiation of the study. Future research recommendations include the qualitative exploration of participants’ “relatedness” or sense of belonging as a construct of the self-determination theory and its impact on HEP adherence. An additional recommendation includes exploring the experiences of older adults completing physical therapy HEPs that are not designed for the cervical spine.

Conclusion

A full understanding of participating in a physical therapy HEP necessitates taking into account aspects that cannot be measured quantitatively. This qualitative research serves as a beneficial window for exploring the experiential phenomena of being an older adult participating in a HEP. The results from this study provide clinicians with valuable insights into how to capitalize on motivational factors and minimize perceived barriers to improve adherence with HEP, ultimately enhancing patient-centered care. Although this study was conducted by physical therapists, other healthcare professionals can likely benefit from the study findings.

Ethical approval

The study received approval from the Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board (Protocol number: 5210004), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Author contribution statement

MJ, GG, EJ, and ND contributed to the conception and design of the work. Also, MJ and GG contributed to drafting the paper and analyzing and interpreting study data. MJ, EJ, MK, and PM collected data for the quantitative study. All authors reviewed the work critically and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Finally, all authors provided approval for the publication of the work.

Data repository

The study data has not been submitted to any data repository.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to our participants for their invaluable contributions to the community.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

There is no data set associated with this paper.

References

- National Institutes of Health. Age. nih.gov. Published 2 Sep 2022. Accessed 9 October 2023. https://www.nih.gov-style-guide/age.

- Charles J. Healthy People 2020 Law and Health: Legal and Policy Resources Related to Older Adults. cdc.gov. Published 19 May 2016. Accessed 9 October 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/hp2020-olderadults.pdf.

- Report of the World Health Organization. Active ageing: a policy framework. PubMed. 2002;5(1):1–37.

- Arena SK, Wilson CM, Boright L, et al. Medical clearance of older adults participating in preventative direct access physical therapy. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e35784. Published 2023 Mar 5. doi:10.7759/cureus.35784.

- Liu-Ambrose T, Davis JC, Best JR, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise program on subsequent falls among community-dwelling high-risk older adults after a fall. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2092–2100. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.5795.

- Hill KD, Hunter SW, Batchelor FA, Cavalheri V, Burton E. Individualized home-based exercise programs for older people to reduce falls and improve physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2015;82(1):72–84. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.005.

- Nyman SR, Victor CR. Older people’s participation in and engagement with falls prevention interventions in community settings: an augment to the Cochrane systematic review. Age Ageing. 2012;41(1):16–23. doi:10.1093/ageing/afr103.

- Bachmann C, Oesch P, Bachmann S. Recommendations for improving adherence to home-based exercise: A systematic review. Phys Med Rehab Kuror. 2017;28(01):20–31. doi:10.1055/s-0043-120527.

- Tzeng HM, Okpalauwaekwe U, Lyons EJ. Barriers and facilitators to older adults participating in fall-prevention strategies after transitioning home from acute hospitalization: A scoping review. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:971–989. Published 2020 Jun 25. doi:10.2147/CIA.S256599.

- Klem NR, Smith A, Shields N, Bunzli S. Demystifying qualitative research for musculoskeletal practitioners, Part 1: What is qualitative research and how can it help practitioners deliver best-practice musculoskeletal care? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(11):531–532. doi:10.2519/jospt.2021.0110.

- Jette AM, Delany C, Lundberg M. The value of qualitative research in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2019;99(7):819–820. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzz070.

- Valenzuela T, Razee H, Schoene D, Lord SR, Delbaere K. An interactive home-based cognitive-motor step training program to reduce fall risk in older adults: Qualitative descriptive study of older adults’ experiences and requirements. JMIR Aging. 2018;1(2):e11975. Published 2018 Nov 30. doi:10.2196/11975.

- Ambrens M, Stanners M, Valenzuela T, et al. Exploring older adults’ experiences of a home-based, technology-driven balance training exercise program designed to reduce fall risk: A qualitative research study within a randomized controlled trial. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2023;46(2):139–148. doi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000321.

- Merriam S, Tisdell E. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, Ca; 2015.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68.

- Van den Broeck A, Ferris DL, Chang CH, Rosen CC. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J Manage. 2016;42(5):1195–1229. doi:10.1177/0149206316632058.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Fortier MS, Duda JL, Guerin E, Teixeira PJ. Promoting physical activity: Development and testing of self-determination theory-based interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):20. Published 2012 Mar 2. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-20.

- Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, Williams G. Facilitating health behavior change and its maintenance: Interventions based on self-determination theory. Eur Health Psychol. 2008;10(1):2–5. https://www.ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/download/ehp.v10.i1.p2/32.

- Sheeran P, Wright CE, Avishai A, Villegas ME, Rothman AJ, Klein WMP. Does increasing autonomous motivation or perceived competence lead to health behavior change? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2021;40(10):706–716. doi:10.1037/hea0001111.

- Rodrigues F, Bento T, Cid L, et al. Can interpersonal behavior influence the persistence and adherence to physical exercise practice in adults? A systematic review. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2141. Published 2018 Nov 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02141.

- Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Ryan RM. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):78. Published 2012 Jun 22. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-78.

- Simek EM, McPhate L, Hill KD, Finch CF, Day L, Haines TP. What are the characteristics of home exercise programs that older adults prefer? A cross-sectional study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(7):508–521. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000000275.

- Felicia Cavallini M, E. Callaghan M, B. Premo C, W. Scott J, J. Dyck D. Lack of time is the consistent barrier to physical activity and exercise in 18 to 64 year-old males and females from both South Carolina and Southern Ontario. JPAR. 2020;5(2):100–106. doi:10.12691/jpar-5-2-6.

- M. Felicia C, Abigail T, Austin J C, David J D. Lack of time is still the main barrier to exercise and physical activity in the elderly, although less so than younger and middle-aged participants. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2022;8(2):151. doi:10.23937/2469-5793/1510151.

- McMahon S, Talley KM, Wyman JF. Older people’s perspectives on fall risk and fall prevention programs: A literature review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2011;6(4):289–298. doi:10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00299.x.

- Forkan R, Pumper B, Smyth N, Wirkkala H, Ciol MA, Shumway-Cook A. Exercise adherence following physical therapy intervention in older adults with impaired balance. Phys Ther. 2006;86(3):401–410. doi:10.1093/ptj/86.3.401.

- Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Pérez AM, Peñacoba C, et al. Key factors associated with adherence to physical exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: An umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):2023. Published 2021 Feb 19. doi:10.3390/ijerph18042023.

- Flegal KE, Kishiyama S, Zajdel D, Haas M, Oken BS. Adherence to yoga and exercise interventions in a 6-month clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7(1):37. Published 2007 Nov 9. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-7-37.

- Argent R, Daly A, Caulfield B. Patient involvement with home-based exercise programs: Can connected health interventions influence adherence? JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(3):e47. Published 2018 Mar 1. doi:10.2196/mhealth.8518.

Appendix a

Interview guide

Tell me about your experience with the home exercise program.

Describe your motivation, if any, to perform the daily home exercise program?

Describe challenges, if any, you may have experienced with the home exercise program?

Describe any changes you have noticed, if any, after completing the 8-week home exercise program?

Describe the impact on your daily life, if any, of completing the 8-week home exercise program?

Do you have any comments regarding the daily text message reminders?