Abstract

Background: Untreated and under-treated pain represent one of the most pervasive health problems, which is worsening as the population ages and accrues risk for pain. Multiple treatment options are available, most of which have one mechanism of action, and cannot be prescribed at unlimited doses due to the ceiling of efficacy and/or safety concerns. Another limitation of single-agent analgesia is that, in general, pain is due to multiple causes. Combining drugs from different classes, with different and complementary mechanism(s) of action, provides a better opportunity for effective analgesia at reduced doses of individual agents. Therefore, there is a potential reduction of adverse events, often dose-related. Analgesic combinations are recommended by several organizations and are used in clinical practice. Provided the two agents are combined in a fixed-dose ratio, the resulting medication may offer advantages over extemporaneous combinations.

Conclusions: Dexketoprofen/tramadol (25 mg/75 mg) is a new oral fixed-dose combination offering a comprehensive multimodal approach to moderate-to-severe acute pain that encompasses central analgesic action, peripheral analgesic effect and anti-inflammatory activity, together with a good tolerability profile. The analgesic efficacy of dexketoprofen/tramadol combination is complemented by a favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, characterized by rapid onset and long duration of action. This has been well documented in both somatic- and visceral-pain human models. This review discusses the available clinical evidence and the future possible applications of dexketoprofen/tramadol fixed-dose combination that may play an important role in the management of moderate-to-severe acute pain.

Introduction

Pain is a global public health issue, and represents the most common reason for both physician consultation and hospital admissionsCitation1,Citation2. When unrelieved or poorly controlled, it is associated with medical complications, poor patient satisfaction, and increased risk of developing chronic painCitation3. Several studiesCitation4–10 have shown that post-operative pain, not adequately managed, can result in chronic pain. Chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) is a serious problem. Indeed, an incidence as high as 50% has been reported, depending on type of surgery undergone. Besides biomedical factors (such as pre-operative pain, severe acute post-operative pain, modes of anesthesia, and surgical approaches), psychosocial elements (especially depression, psychological vulnerability, stress, and late return to work) show a likely correlation with CPSPCitation11. Recent studies suggest that CPSP may be prevented thanks to the right post-operative analgesic strategiesCitation12,Citation13.

On a global scale, the impact of pain has far reaching effects upon the social structure, function, and economic welfare of society as a whole. Moreover, the burden of pain has a significant impact on healthcare utilization and labor force participationCitation14,Citation15. Hence, effective pain control should be a priority that needs to be fully addressed.

Recent years have seen a progressive unraveling of the neuroanatomical circuits and cellular mechanisms underlying pain initiation, including the identification of molecules able to modulate specific neuronal cell types, which could represent novel targets for innovative pain therapies. Major advances have occurred at all levels, spanning from studies investigating pain transduction mechanisms as well as neuronal plasticity to cortical imaging studies, which have revealed how pain is experienced at the cognitive levelCitation16,Citation17. Furthermore, advances in imaging technology provided pain physicians with advanced tools for the diagnosis of different types of pain, and evaluation of its treatmentsCitation16.

Current pain management: therapeutic challenges

Despite advances in pain medicine, the management of acute pain appears not to be a priority, and is still poorly addressed. Untreated and under-treated pain represent the most pervasive health problem, that is worsening as the population ages and accrues risk for pain-causing diseases and disorders. Indeed, pain care has not yet achieved the synergy that should be afforded through a comprehensive and integrated approach to research, diagnosis, and treatment of painCitation16. Thus, pain management still poses several challenges to all the healthcare professionals. These include deeper appreciation of the complex interplay between peripheral and central nervous systems in pain perception, increased awareness of the multiple mechanisms underlying pain transmission, facilitation and inhibition, as well as a clear identification of the barriers within the global health systems, and among clinicians and healthcare professionals to appropriately assess and manage pain.

Multiple options are currently available for pain management, most of which have predominantly mono-modal mechanisms of analgesic actionCitation18, and cannot be prescribed at unlimited doses due to the ceiling of efficacy and/or safety concernsCitation19. Therefore, the optimal strategy for treating this multifaceted medical condition is one that uses a combination of drugs that acts through multiple modes and sites of action to the therapeutic end-point, i.e. analgesiaCitation18. Combining drugs with different mechanisms and sites of action would yield a better pain relief, with the fewest side-effectsCitation18. This concept is widely accepted in the literature. At the beginning, it was pharmacologically studied in the 1960s by Houde et al.Citation20, then clinically suggested (especially in post-operative pain) in the 1980sCitation21, and a few years later very much diffused by Kehlet and DahlCitation22, who were talking of “multimodal” analgesia. More recently, the “multimodal analgesia” has been deeply studied also to see whether the drugs used together may be simply additive or synergisticCitation23, do well in single-dose analgesic studiesCitation24, and offer several benefits, including a broader spectrum of action, greater efficacy, better compliance, and a better efficacy/safety ratioCitation25. As a result, analgesic combinations are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), American Pain Society (APS), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR)Citation26–29, and are commonly used in clinical practice. Provided the two agents are combined in a fixed-dose ratio, the resulting medication may offer additional advantages over extemporaneous combinations, including ease of administration, reduction of pill burden, and/or requirement for lower dosages of the individual componentsCitation30.

Analgesic drug combinations

In patients with moderate-to-severe pain the general recommendation is the combination of opioid/non-opioid analgesics, based on the increasing pain severityCitation31. A number of analgesic drug combinations have been tested for the management of post-operative pain, including paracetamol with weak (e.g. codeine or tramadol) or strong (e.g. morphine or oxycodone) opioids. Besides being less effective than NSAIDsCitation32,Citation33, paracetamol may not be as safe as originally believed, both from a gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular (CV) perspective, not to mention the well-known hepatotoxicity (especially at doses higher than 3 g daily)Citation34,Citation35. Despite adding codeine to paracetamol producing worthwhile additional pain reliefCitation36, none of the available studies found this combination to be superior to NSAIDs in controlling post-operative painCitation37. Combining an effective NSAID with an opioid could represent, therefore, a better alternative. NSAID/opioid combinations have the advantage of additive analgesic effect, along with a low dose of opioids and, hence, minimal undesirable adverse effectsCitation31. In addition, NSAIDs display a well demonstrated opioid-sparing activityCitation38, allowing a significant opioid dose reduction as well as a significant reduction in nausea, post-operative nausea and vomiting, and potential respiratory depression, always possible at the end of surgery; an effect not observed with selective COX-2 inhibitors or paracetamolCitation39.

The success of a drug combination depends on the proper selection of both the NSAID and the opioid, as well as of the most appropriate ratio for their combination. Given these indices, the resultant medications should provide an enhanced analgesic efficacy and safety, compared with the single drugs administered in monotherapy.

Currently available NSAID-opioid fixed-dose combinations

Hydrocodone/ibuprofen (7.5 mg/400 mg) and Oxycodone/ibuprofen (5 mg/400 mg) are two oral, fixed-dose combination formulations. They are approved in the US for the short-term (up to 7 days) management of acute, moderate-to-severe pain. A single tablet provided better analgesia than low-dose hydrocodone/oxycodone or ibuprofen, administered alone, in most trials, and appeared to be more effective than a single dose of some other fixed-dose combination analgesics. While co-administration of ibuprofen and hydrocodone/oxycodone in experimental models produces synergistic analgesiaCitation40,Citation41, clinical trials in patients submitted to oral surgery showed only an additive effectCitation42,Citation43. Nausea, dizziness, and somnolence were the treatment-related adverse events that occurred most frequently after a single dose or multiple doses.

A fixed dose combination (FDC) of the fast acting NSAID, dexketoprofen trometamol, and the long acting opioid, tramadol hydrochloride, has been recently developed to generate multimodal analgesia at lower and better tolerated doses than those of the single agents used alone. The rationale for developing an oral FDC of dexketoprofen 25 mg and tramadol 75 mg (referred to as DKP/TRAM FDC) lies in their different modes and sites of action, their complementary pharmacokinetic profiles, and the lower incidence of the typical side-effects of each classCitation44–47, providing physicians with an effective and safe analgesic for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acute painCitation48.

Unique pharmacological features of dexketoprofen and tramadol

NSAIDs are very effective drugs, and are widely used for acute and chronic painCitation49,Citation50, but their use is associated with a broad spectrum of adverse reactions involving GI, liver, kidney, CV system, and skinCitation51–53. Different attempts have been made to reduce NSAID-induced gastro-duodenal damageCitation53. These include enteric-coated preparations or soluble formulations of NSAIDs, buffered preparations, non-acidic pro-drugs, and the development of enantiomers. The chiral switch of NSAIDs proved to be a rational approach to improve both the efficacyCitation54 and safetyCitation55 of this class of drugs.

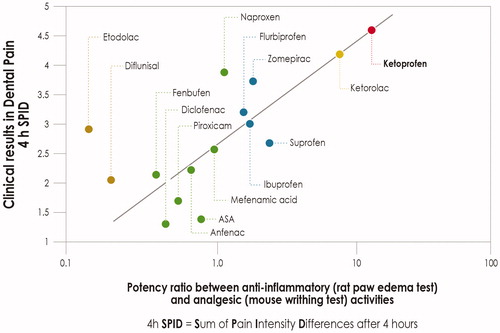

While inhibition of prostanoid synthesis remains an important analgesic mode of action for NSAIDs, both in the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS), other mechanisms should be consideredCitation56. Some NSAIDs, in addition to their effects on prostanoid synthesis, also affect the synthesis and activity of other neuroactive substances, believed to have key roles in processing nociceptive input within the dorsal hornCitation57. It has been argued that these other actions, in conjunction with COX inhibition, may synergistically augment the effects of NSAIDs on spinal nociceptive processing. When the clinical efficacy of NSAIDs in dental pain is plotted against the ratio between anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities in experimental models, ketoprofen appears to be the most effective analgesic amongst the different NSAIDs ()Citation56. Along the same lines, a recent meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 898 patientsCitation58 found that the efficacy of oral ketoprofen in relieving moderate-to-severe pain was significantly better than that achieved with ibuprofen and/or diclofenac.

Figure 1. Correlation between NSAID anti-inflammatory/analgesic potency ratio in experimental models and clinical analgesic activity in a model of post-surgical dental pain. Graphical elaboration from CashmanCitation56.

Dexketoprofen is an anti-inflammatory and analgesic drug inhibiting COX1 and COX2Citation47, and appears to be as effective as the double dose of the racemic ketoprofen, but with a faster onset of analgesiaCitation47,Citation59,Citation60. Compared with the free drug, dexketoprofen trometamol has an increased bioavailability accelerating the onset of the therapeutic effect, with a tmax between 0.25–0.75 hCitation44, thus ensuring rapid pain relief, an important feature for the treatment of acute pain episodes. Dexketoprofen trometamol is an effective analgesic to relieve pain in the acute symptomatic period and its use has been shown as beneficial in a wide range of clinical conditionsCitation44. A systematic review of the clinical studies concluded that dexketoprofen is at least as effective as other NSAIDs or paracetamol/opioid combinationsCitation60. For instance, analgesic efficacy of oral dexketoprofen trometamol is similar to that of ibuprofen in patients with moderate-to-severe dental pain, with a shorter time to onset of analgesiaCitation61.

Dexketoprofen efficacy and rapid onset of analgesic activityCitation44 is complemented by a safety profile that favors dexketoprofen over many other NSAIDs. In fact, its administration is associated with a lower risk of GI bleeding compared to rofecoxib and meloxicamCitation44,Citation47, and this is particularly relevant in the post-operative settingCitation44. However, it is worthwhile to emphasize that gastroprotection is mandatory in patients holding one or more GI risk factorsCitation35,Citation52,Citation53. Data from clinical trials showed that dexketoprofen trometamol is well tolerated, and its adverse event profile appears similar to that of the new generation of NSAIDsCitation47. Thus, dexketoprofen trometamol is an excellent example that chiral switch of NSAIDs, shown to be a rational approach to improve both the efficacyCitation54 and safety of NSAIDsCitation55.

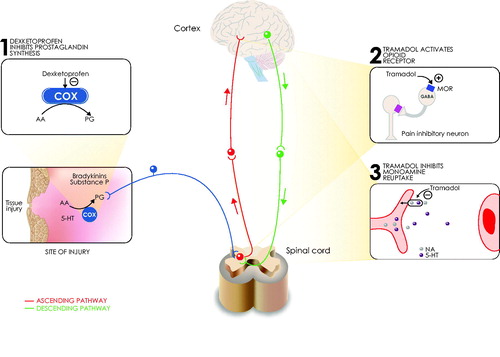

Opioid therapy continues to be an important “mainstream” option for the relief of pain, despite continued debate over the efficacy and safety of the use of opioids in chronic non-cancer painCitation62–66. Tramadol hydrochloride is an analgesic with a dual mode of action: opioid receptor activation (with high affinity for μ-receptors) and inhibition of monoamine re-uptakeCitation45,Citation46 (), and offers a suitable alternative, since these two complementary actions are synergistic, enhancing its analgesic effects and improving its tolerability profile. The dual mode of action may be a reflection of the actions of the two enantiomers that form the racemic mixture of tramadol, with the (+) enantiomer showing higher affinity for μ-receptors and being a more effective inhibitor of serotonin, while the (–) enantiomer is a more effective inhibitor of noradrenaline re-uptakeCitation45. Opioid and non-opioid mechanisms of tramadol are thought to act synergistically on descending inhibitory pathways in the CNS, resulting in the modulation of second order neurons in the spinal cord. Moreover, tramadol inhibition of monoamine re-uptake augments the chemical signal of the descending pain inhibitory pathways, while decreasing the ascending pain impulse. In humans, the central analgesic effect of tramadol is only partially reversed by the opioid antagonist naloxone, thus confirming the involvement of non-opioid mechanisms in its pain-relieving activityCitation67. Compared with codeine (which is a pro-drug), tramadol is an active compound with active metabolites ()Citation68,Citation69.

Table 1. Summary of the pharmacodynamic features of the opiod agonists, usually combined with non-opioid analgesics.

Table 2. Summary of the pharmacokinetic features of the opiod agonists, usually combined with non-opioid analgesics.

Tramadol efficacy for the management of moderate-to-severe pain has been demonstrated both in inpatients and day surgery patients, and was found to be comparable to that achieved using equi-analgesic doses of parenteral morphine or alfentanilCitation45. Tramadol analgesic efficacy is complemented by a long duration of action (t1/2 ∼ 6 h) and by a safety profile that favors tramadol over other opioids. Indeed, tramadol has no relevant effects on CV and pulmonary parameters, causes less constipation and opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, and has a low addiction rateCitation45,Citation46.

Tramadol analgesic efficacy can further be improved by combination with a non-opioid analgesicCitation45. Pre-clinical studies in models of nociceptionCitation70–73 provided first evidence of the analgesic synergism between tramadol and dexketoprofen, and supported the general premise of interaction between drugs with a different mechanism of actionCitation73. Moreover, the anti-nociceptive effect of the combination occurred at doses lower than those necessary for each drug alone to produce comparable effectsCitation70, while the dose ratio corresponding to synergism was identified as dexketoprofen/tramadol 1:3Citation72,Citation73. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction is common, and represents a significant barrier to achieving optimal pain managementCitation74. Animal studies suggested that NSAIDs—when combined with tramadol—may limit constipationCitation75. Accordingly, dexketoprofen was found to be able to counteract tramadol-induced inhibition of GI transitCitation72. It is worthwhile mentioning that constipation represents an adverse effect of tramadol less frequently than for other opioids, when given aloneCitation45. In patients receiving paracetamol-tramadol combination, the incidence of constipation was almost half that observed with paracetamol-codeine combinationCitation76. A Phase I study in healthy volunteers showed that the relevant pharmacokinetic parameters of dexketoprofen and of tramadol remain virtually identical when these two compounds are administered together, showing the lack of drug-to-drug PK interactionCitation77.

Pharmacodynamic profile of dexketoprofen/tramadol FDC

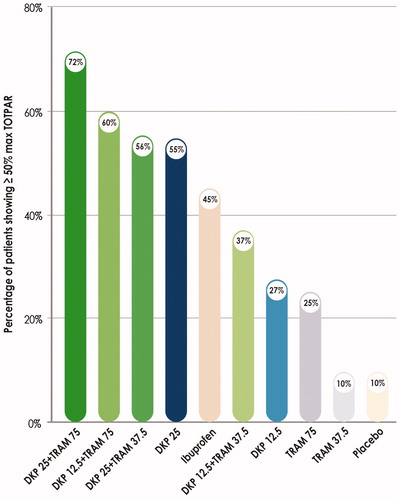

Pre-trial calculations and a dose-finding studyCitation48 selected an optimal combination of doses of dexketoprofen and tramadol, i.e. 25 mg for the former and 75 mg for the latter, thus confirming that the 1:3 ratio leads to analgesic synergism (). Three different but complementary mechanisms of action contribute to DKP/TRAM FDC multimodal analgesia ():

Figure 2. Clinical study in a dental pain model showing the best analgesic efficacy of the dexketoprofen-tramadol combination in a 1:3 ratio. Percentage of patients showing response (≥ 50% max TOTPAR) over 6 h post-dose (Primary end-point). Maximum TOTPAR corresponds to the theoretical maximum possible time-weighted sum of the PAR scores, measured on a 5-point VRS (0 = none to 4 = complete). Graphical elaboration from Moore et al.Citation48

Figure 3. Fixed-dose combination dexketoprofen/tramadol mechanism of action. Different modes of action contribute to dexketoprofen/tramadol analgesic FDC efficacy. A synergy between central analgesic action, peripheral analgesic effect, and anti-inflammatory activity underlies the multimodal analgesia provided by the fixed-dose combination dexketoprofen/tramadol. 5-HT: 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); AA: arachidonic acid; COX: cyclo-oxygenase; GABA: γ-amino-butyric acid; MOR: μ-opioid receptor; NA: noradrenaline; PG: prostaglandin.

the analgesic (and anti-inflammatory) action of dexketoprofen, and its central actionCitation57;

the opioid receptor activation by tramadol, and

the indirect activation of central descending monoaminergic pathways by tramadol, with consequent inhibition of the nociceptive transmission to the brain.

Thus, DKP/TRAM FDC is expected to result in a balanced peripheral and central analgesia, along with an anti-inflammatory actionCitation78, and to meet the most recent guidelines on the management of acute post-operative painCitation27. At least an additive if not a synergistic effect of this combination is anticipated to result in a tramadol-sparing effect, and accordingly DKP/TRAM FDC contains a dose of tramadol lower than that recommended on its own for the treatment of severe acute pain. In the DKP/TRAM FDC, the rapid onset of the analgesic effect of dexketoprofen is complemented by the prolonged duration of action of tramadolCitation78.

In summary, the combination of dexketoprofen and tramadol is rational from both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic standpoints. Also, indeed, phase II and III studies showed a superior analgesic efficacy of the DKP/TRAM FDC over dexketoprofen and tramadol monotherapy in different models of post-surgical painCitation48,Citation78,Citation79, providing evidence for its clinical use.

Dexketoprofen/tramadol FDC in the management of acute, moderate-to-severe pain: efficacy and safety in clinical trials

The DKP/TRAM FDC was approved in Europe with a decentralized procedure on January 2016, and it is under registration in many other extra-European countries. The DKP/TRAM FDC is indicated for the short-term symptomatic treatment of moderate-to-severe acute pain on the evidence of its analgesic efficacy in three well established human modelsCitation80, such as third mandibular molar tooth extractionCitation48, soft tissue surgeries (STS)Citation78, and joint replacement surgeryCitation79, involving some 1,900 patients with moderate-to-severe acute pain.

In 606 patients undergoing third molar tooth extraction, the administration of DKP/TRAM FDC provided a higher response rate (≥50% max total pain relief, TOTPAR) over the 6 h post-dose compared to that achieved by dexketoprofen 25 mg and tramadol 75 mgCitation48. DKP/TRAM FDC exhibited the highest relative risk reduction (RRR), the lowest number needed to treat (NNT = 1.6), and offered the greatest pain relief, lasting up to 8 h. Importantly, patients receiving DKP/TRAM FDC needed less rescue medications. They also had the longest time to re-medication (8 h vs 1.4 h in the placebo receiving patients), and reported the highest scores of patient global evaluation (PGE). Currently, these figures were comparable or even better than those of most other oral treatments for acute painCitation24.

Abdominal hysterectomy is an example of soft tissue surgeries (STS), and it is one of the procedures most frequently associated to pain in the gynecological populationCitation80,Citation81. In 606 patients submitted to abdominal hysterectomy for benign conditions, the analgesic efficacy of DKP/TRAM FDC was assessed both in single-dose (8 h post-dose) and multiple-dose doses (6 consecutive doses) within a 3-days treatment period. At rest, pain relief provided by the DKP/TRAM FDC was superior to that achieved by monotherapy after both single-dose (measured as Summed Pain Intensity Differences at 8 h - SPID8,) and multiple-dose (measured as mean pain intensity on a VAS scale) treatment. Similar results were seen for mean pain intensity on movement over 48 hCitation78. Like the oral surgery trial, the DKP/TRAM FDC was statistically superior to each single component in terms of percentage of responders and PGE scores. Here again, the percentage of patients using rescue medication over 24 h was significantly lower with the FDC than with dexketoprofen or tramadol. In addition, the overall time to first use of rescue medication was longer on DKP/TRAM FDC compared with each single agentCitation78.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an example of joint replacement surgery that has been shown to improve long-term quality-of-lifeCitation80,Citation82. It has been regarded as the surgical intervention with greatest improvement in pain and physical functionCitation79. In 641 patients undergoing primary, unilateral THA, the ability of DKP/TRAM FDC to provide pain relief both at rest and on movement was investigated after single (8-h post-dose) and in multiple-dose (12 consecutive doses) treatment during a 5-days period. The DKP/TRAM FDC showed superior and sustained efficacy in pain control vs the single agents at the same (i.e. dexketoprofen 25 mg) or at higher dose (i.e. tramadol 100 mg). The highest value of SPID8 was reported in patients receiving the DKP/TRAM FDC, 77% of whom were responders (mean pain intensity VAS score <40) 8 h after the single dose. Furthermore, the analysis of pain intensity scores and mean SPID values at rest from the 3–4 h time point onwards confirmed the superiority of the DKP/TRAM FDC over the single components. Analysis of pain intensity scores at rest during the multiple-dose phase study demonstrated the superior analgesic effect throughout 48 h. In line with the findings from the other clinical trialsCitation48,Citation78, patients receiving DKP/TRAM FDC experienced longer time to first use of rescue medication. Since early mobilization is crucial after hip arthroplasty, pain on movement was also investigated on days 2 and 3. Mean scores for worst pain on movement were slightly lower in DKP/TRAM-treated patients compared to those receiving the single agentsCitation79.

The DKP/TRAM FDC combines two drugs with known tolerability profiles and, accordingly, safety data stemming from clinical trials are consistent with those previously reported for dexketoprofen and tramadol, when used alone. The incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was lower with the FDC than with dexketoprofen (25 mg) and tramadol (100 mg), the most frequent ADRs being nausea, vomiting, and dizzinessCitation48,Citation78,Citation79. Moreover, no marked differences in safety outcomes including heart rate, blood pressure, and physical examination were detected.

In conclusion, DKP/TRAM FDC treatment provides effective multimodal analgesia with a good tolerability profile. DKP/TRAM FDC-based therapy is associated with higher percentages of patients experiencing pain relief of short onset, lesser need of rescue medication () and higher PGE scoresCitation48,Citation78,Citation79. The increased clinical benefits of this combination are not accompanied by an increase in the number and/or severity of adverse events.

Table 3. Percentage of pain intensity (PI) responders (achievement of mean pain intensity VAS <40 mm) at rest over the first 8 h and percentage of patients using rescue medication (RM) over 24 h, during the multiple dose phase in clinical trials with DKP/TRAM FDC.

DKP/TRAM FDC: from clinical trials to clinical practice

The unique pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile makes the DKP/TRAM FDC an attractive option for adequate management of different painful conditions. Even in high resource countries, pain management in patients undergoing surgery is sub-optimal, with ∼50% of patients reporting pain intensity >4 on the first post-operative day (NRS 0–10)Citation83,Citation84. Specific areas of improvement in post-operative pain management include the so-called small surgeries with under-estimated levels of pain, like appendectomiesCitation85. Multimodal analgesia (achieved by the combination of opioid and non-opioid analgesics) remains the most widespread approach to treat acute post-operative pain, as recommended by the recent APS guidelinesCitation27. In this connection, the clinical potential of DKP/TRAM FDC is large, and can be effective in minor day case surgeries as well as major surgeries, when the oral route (or the switch to it) is feasible. Its use may also be envisaged for minor surgeries with spinal or regional blocks, such as bunionectomy, rotator cuff repair, as well as for the treatment of breakthrough episodes of pain. Its efficacy in controlling post-operative pain after total hip and knee replacement will allow early patient mobilization, lowering thromboembolic risk, shortening hospitalization, and timely starting of rehabilitationCitation86.

Low back pain and osteoarthritis are highly prevalent in the general populationCitation87, and their therapeutic management should be flexibleCitation88–90 and address the different patterns of pain trajectories (continuous pain along with acute flares) that characterize them. Moreover, pain intensity is dependent on time and exerciseCitation91. DKP/TRAM FDC represents an attractive medication for acute exacerbations of osteoarticular (OA) pain due to its pharmacological profile. OA pain is a mixed phenomenon, where nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms are involved in both the local and central levels and may present with different clinical features: constant and intermittent pain, with or without a neuropathic component, and with or without central sensitizationCitation92,Citation93. There is a wealth of literature showing the analgesic efficacy of dexketoprofenCitation94–96 and tramadolCitation97–99, either single or multiple dosing regimens, in both osteoarthritis and low back pain. Their combination, targeting different sites of action, is, therefore, suitable for this mixed type of pain, arising from different body structures (joints, muscles, ligaments, etc.).

Rehabilitation (exercise and strength training) is widely recommended by international guidelines for managing OA painCitation100, and is even considered by 2014 OARSI guidelinesCitation101 as the core treatment for all patients. Joint mobilization, however, may trigger or increase pain, and often discourage patients from continuing training programs; in this context, the DKP/TRAM FDC could be useful to relieve movement-related acute pain and allow proper rehabilitation.

Conclusions

A fixed-dose combination of dexketoprofen (25 mg) and tramadol (75 mg) (DKP/TRAM FDC) provides a comprehensive multimodal approach for moderate-to-severe acute pain, thanks to the central analgesic effect, peripheral analgesic action, and anti-inflammatory activityCitation27,Citation78,Citation79. Together with an effective analgesic efficacy, the combination shows a good tolerability profileCitation48,Citation78,Citation79. A very recent Cochrane reviewCitation102 concluded that “A single oral dose of dexketoprofen 25 mg plus tramadol 75 mg provided good levels of pain relief with long duration of action to more people than the same dose of dexketoprofen or tramadol alone”. On the grounds of its efficacy and safety, this medication, which results from the combination of two drugs that have stood the test of time, should be considered as a useful addition to our therapeutic armamentarium against pain.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was carried out thanks to an unrestricted educational grant from MENARINI International.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MENARINI did not have any role in design, planning, or execution of the review. The terms of the financial support from MENARINI included freedom for the authors to reach their own conclusions, and an absolute right to publish the results of this work, irrespective of any conclusions reached. WM reports personal fees from Menarini, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Grunenthal, Mundipharma, AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, BioQPharma, and Medicine Company, outside the submitted work. MH, GM, A. Montes, A. Montero, SP, CS, and GV are members of the Scientific Advisory Board and of the Speakers’ Bureau of MENARINI International. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Chiara Degirolamo, PhD (Letscom SRL, Scientific Division, Rome) for her invaluable help during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011;11:770

- Sessle B. Unrelieved pain: a crisis. Pain Res Manag 2011;16:416-20

- Sinatra R. Multimodal management of acute pain: the role of IV NSAIDs. New York,NY: Mac Mahon Pub; 2011. p 571-81

- Gerbershagen HJ, Dagtekin O, Rothe T, et al. Risk factors for acute and chronic postoperative pain in patients with benign and malignant renal disease after nephrectomy. Eur J Pain 2009;13:853-60

- Gerbershagen HJ, Ozgur E, Dagtekin O, et al. Preoperative pain as a risk factor for chronic post-surgical pain - six month follow-up after radical prostatectomy. Eur J Pain 2009;13:1054-61

- Jin J, Peng L, Chen Q, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for chronic pain following cesarean section: a prospective study. BMC Anesthesiol 2016;16:99

- Weibel S, Neubert K, Jelting Y, et al. Incidence and severity of chronic pain after caesarean section: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2016;33:853-65

- Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:77-86

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000435

- Simanski CJ, Althaus A, Hoederath S, et al. Incidence of chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) after general surgery. Pain Med 2014;15:1222-9

- Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Jarvinen I, et al. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) - a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2009;13:719-30

- Dahl JB, Kehlet H. Preventive analgesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2011;24:331-8

- Gritsenko K, Khelemsky Y, Kaye AD, et al. Multimodal therapy in perioperative analgesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2014;28:59-79

- Langley P, Muller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, et al. The impact of pain on labor force participation, absenteeism and presenteeism in the European Union. J Med Econ 2010;13:662-72

- Langley P, Muller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, et al. The societal impact of pain in the European Union: health-related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization. J Med Econ 2010;13:571-81

- Dubois MY, Gallagher RM, Lippe PM. Pain medicine position paper. Pain Med 2009;10:972-1000

- Stucky CL, Gold MS, Zhang X. Mechanisms of pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:11845-6

- Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV Jr, Tallarida RJ. The determination and application of fixed-dose analgesic combinations for treating multimodal pain. J Pain 2010;11:701-9

- Schug SA, Garrett WR, Gillespie G. Opioid and non-opioid analgesics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2003;17:91-110

- Houde R, Wallenstein S, Beaven W. Clinical measurement of pain. In: De Stevens G, editor. Analgesics. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1965. p 75-122

- Varrassi G. Non-opioid drugs in the potentiation of postoperative analgesia [Farmaci non oppioidi nel potenziamento dell’analgesia postoperatoria]. In: Casa Editrice l’Antologia, editor. Varrassi G. Atti 11° Congresso Nazionale AISD. Napoli, Italy:Casa Editrice L'Antologia; 1988. p 53–70. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313439665_Atti_-_XI_Congresso_Nazionale_AISD [Last access March 29th 2017]

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesthes Analges 1993;77:1048-56

- Moore RA, Derry CJ, Derry S, et al. A conservative method of testing whether combination analgesics produce additive or synergistic effects using evidence from acute pain and migraine. Eur J Pain 2012;16:585-91

- Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ, et al. Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev 2011:CD008659

- Raffa RB, Tallarida RJ, Taylor R Jr, et al. Fixed-dose combinations for emerging treatment of pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:1261-70

- Schug SA, Zech D, Dorr U. Cancer pain management according to WHO analgesic guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage 1990;5:27-32

- Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain 2016;17:131-57

- Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1905-15

- Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and chronic cancer pain, 2nd edition. American Pain Society. Clin Pharm 1990;9:601-12

- O’Brien J, Pergolizzi J, van de Laar M, et al. Fixed-dose combinations at the front line of multimodal pain management: perspective of the nurse-prescriber. Nursing Res Rev 2013:9

- Chandanwale AS, Sundar S, Latchoumibady K, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of combination of tramadol-diclofenac versus tramadol-paracetamol in patients with acute musculoskeletal conditions, postoperative pain, and acute flare of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a Phase III, 5-day open-label study. J Pain Res 2014;7:455-63

- da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;387:2093-105

- Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 2015;350:h1225

- Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:552-9

- Scarpignato C, Lanas A, Blandizzi C, et al. Safe prescribing of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with osteoarthritis–an expert consensus addressing benefits as well as gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks. BMC Med 2015;13:55

- Moore A, Collins S, Carroll D, et al. Paracetamol with and without codeine in acute pain: a quantitative systematic review. Pain 1997;70:193-201

- Nauta M, Landsmeer ML, Koren G. Codeine-acetaminophen versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of post-abdominal surgery pain: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Surg 2009;198:256-61

- Varrassi G, Marinangeli F, Agrò F, et al. A double-blinded evaluation of propacetamol versus ketorolac in combination with patient-controlled analgesia morphine: analgesic efficacy and tolerability after gynecologic surgery. Anesth Analg 1999;88:611-16

- Maund E, McDaid C, Rice S, et al. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the reduction in morphine-related side-effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:292-7

- Kolesnikov YA, Wilson RS, Pasternak GW. The synergistic analgesic interactions between hydrocodone and ibuprofen. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1721-3

- Oldfield V, Perry CM. Oxycodone/ibuprofen combination tablet: a review of its use in the management of acute pain. Drugs 2005;65:2337-54

- Betancourt JW, Kupp LI, Jasper SJ, et al. Efficacy of ibuprofen-hydrocodone for the treatment of postoperative pain after periodontal surgery. J Periodontol 2004;75:872-6

- Van Dyke T, Litkowski LJ, Kiersch TA, et al. Combination oxycodone 5 mg/ibuprofen 400 mg for the treatment of postoperative pain: a double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled parallel-group study. Clin Ther 2004;26:2003-14

- Rodriguez MJ, Arbos RM, Amaro SR. Dexketoprofen trometamol: clinical evidence supporting its role as a painkiller. Expert Rev Neurother 2008;8:1625-40

- Scott LJ, Perry CM. Tramadol: a review of its use in perioperative pain. Drugs 2000;60:139-76

- Vazzana M, Andreani T, Fangueiro J, et al. Tramadol hydrochloride: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse side effects, co-administration of drugs and new drug delivery systems. Biomed Pharmacother 2015;70:234-8

- Walczak JS. Analgesic properties of dexketoprofen trometamol. Pain Manage 2011;1:409-16

- Moore RA, Gay-Escoda C, Figueiredo R, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol: randomised double-blind trial and confirmation of empirical theory of combination analgesics in acute pain. J Headache Pain 2015;16:541

- Brooks PM, Day RO. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—differences and similarities. NEJM 1991;324:1716-25

- Tramer MR, Williams JE, Carroll D, et al. Comparing analgesic efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs given by different routes in acute and chronic pain: a qualitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1998;42:71-9

- Aronson JK. Meyler’s side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. 2010 Amsterdam: Elsevier

- Lanas A, Hunt R. Prevention of anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal damage: benefits and risks of therapeutic strategies. Annals Med 2006;38:415-28

- Scarpignato C, Hunt RH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-related injury to the gastrointestinal tract: clinical picture, pathogenesis, and prevention. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2010;39:433-64

- Hardikar MS. Chiral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—a review. J Indian Med Assoc 2008;106:615-8, 22, 24

- Scarpignato C, Bretagne I, de Pouvourville J, et al. Working team report: towards a GI safer anti-inflammatory therapy. Gastroenterol Int 1999;12:186-215

- Cashman JN. The mechanisms of action of NSAIDs in analgesia. Drugs 1996;52(Suppl 5):13-23

- Miranda HF, Sierralta F, Aranda N, et al. Pharmacological profile of dexketoprofen in orofacial pain. Pharmacol Rep 2016;68:1111-14

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Lanata L, et al. Efficacy of ketoprofen vs ibuprofen and diclofenac: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Exper Rheumatol 2013;31:731-8

- McGurk M, Robinson P, Rajayogeswaran V, et al. Clinical comparison of dexketoprofen trometamol, ketoprofen, and placebo in postoperative dental pain. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:46S-54S

- Moore RA, Barden J. Systematic review of dexketoprofen in acute and chronic pain. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2008;8:11

- Mauleon D, Artigas R, Garcia ML, et al. Preclinical and clinical development of dexketoprofen. Drugs 1996;52(Suppl 5):24-45; discussion 46

- Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:828-42

- Brooks A, Kominek C, Pham TC, et al. Exploring the use of chronic opioid therapy for chronic pain: when, how, and for whom? Med Clin N Am 2016;100:81-102

- Cheung CW, Qiu Q, Choi SW, et al. Chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain: a review and comparison of treatment guidelines. Pain Physician 2014;17:401-14

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids guidelines Panel Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10:113-30

- Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Internal Med 2014;160:38-47

- Collart L, Luthy C, Dayer P. Partial inhibition of tramadol antinociceptive effect by naloxone in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1993;35:73

- Reeves RR, Burke RS. Tramadol: basic pharmacology and emerging concepts. Drugs of Today (Barcelona, Spain: 1998) 2008;44:827-36

- Bertilsson L, Dahl ML, Dalen P, et al. Molecular genetics of CYP2D6: clinical relevance with focus on psychotropic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002;53:111-22

- Cialdai C, Giuliani S, Valenti C, et al. Comparison between oral and intra-articular antinociceptive effect of dexketoprofen and tramadol combination in monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2013;714:346-51

- Miranda HF, Prieto JC, Puig MM, et al. Isobolographic analysis of multimodal analgesia in an animal model of visceral acute pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2008;88:481-6

- Miranda HF, Puig MM, Romero MA, et al. Effects of tramadol and dexketoprofen on analgesia and gastrointestinal transit in mice. Fundament Clin Pharmacol 2009;23:81-8

- Miranda HF, Romero MA, Puig MM. Antinociceptive and anti-exudative synergism between dexketoprofen and tramadol in a model of inflammatory pain in mice. Fundament Clin Pharmacol 2012;26:373-82

- Sprawls KS, L.H. E, Spierings E, Tran SaD. Drugs in development for opioid-induced constipation. In: Catto-Smith DA, editor. Drugs in development for opioid-induced constipation, constipation - causes, diagnosis and treatment: InTech; 2012;89-98

- Planas E, Poveda R, Sanchez S, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs antagonise the constipating effects of tramadol. Eur J Pharmacol 2003;482:223-6

- Mullican WS, Lacy JR, Group T-A-S. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets and codeine/acetaminophen combination capsules for the management of chronic pain: a comparative trial. Clin Ther 2001;23:1429-45

- Mazzei P, Milleri S, Paredes Lario I, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dexketoprofen and tramadol given in combination: an open-label, randomized, 3-period crossover study in Healthy subjects. Clin Therapeut 2015;37:e124

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Tomaszewski J, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol 25 mg/75 mg: randomised double-blind trial in moderate-to-severe acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. BMC Anesthesiol 2016;16:9

- McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Berta A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of dexketoprofen/tramadol 25 mg/75 mg in moderate-to-severe pain after total hip arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2016;116:269-76

- Singla NK, Desjardins PJ, Chang PD. A comparison of the clinical and experimental characteristics of four acute surgical pain models: dental extraction, bunionectomy, joint replacement, and soft tissue surgery. Pain 2014;155:441-56

- Calderon M, Castorena G, Pasic E. Postoperative pain management after hysterectomy – a simple approach, hysterectomy. In: Al-Hendy DA, ed. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2012;269-282

- Anastase DM, Cionac Florescu S, Munteanu AM, et al. Analgesic techniques in hip and knee arthroplasty: from the daily practice to evidence-based medicine. Anesthesiol Res Prac 2014;2014:569319

- Benhamou D, Berti M, Brodner G, et al. Postoperative Analgesic THerapy Observational Survey (PATHOS): a practice pattern study in 7 central/southern European countries. Pain 2008;136:134-41

- Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, et al. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:149-60

- Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, et al. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2013;118:934-44

- Young AC, Buvanendran A. Pain management for total hip arthroplasty. J Surg Orthopaed Adv 2014;23:13-21

- Langley PC. The prevalence, correlates and treatment of pain in the European Union. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:463-80

- Perrot S. Should we switch from analgesics to the concept of “Pain Modifying Analgesic Drugs (PMADs)” in osteoarthritis and rheumatic chronic pain conditions? Pain 2009;146:229-30

- Perrot S, Marty M, Legout V, et al. Ecological or recalled assessments in chronic musculoskeletal pain? A comparative study of prospective and recalled pain assessments in low back pain and lower limb painful osteoarthritis. Pain Med 2011;12:427-36

- Perrot S, Poiraudeau S, Kabir-Ahmadi M, et al. Correlates of pain intensity in men and women with hip and knee osteoarthritis. Results of a national survey: the French ARTHRIX study. Clin J Pain 2009;25:767-72

- Marty M, Rozenberg S, Legout V, et al. Influence of time, activities, and memory on the assessment of chronic low back pain intensity. Spine 2009;34:1604-9

- Fusco M, Skaper SD, Coaccioli S, et al. Degenerative joint diseases and neuroinflammation. Pain Pract 2016:n/a-n/a. DOI: 10.1111/papr.12551

- Perrot S. Osteoarthritis pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:90-7

- Beltran J, Martin-Mola E, Figueroa M, et al. Comparison of dexketoprofen trometamol and ketoprofen in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:74S-80S

- Marenco JL, Perez M, Navarro FJ, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind study to compare the efficacy and tolerability of dexketoprofen trometamol versus diclofenac in the symptomatic treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Clin Drug Investig 2000;19:247-56

- Zippel H, Wagenitz A. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of intramuscular dexketoprofen versus diclofenac in the symptomatic treatment of acute low back pain. Clin Drug Investig 2007;27:533-43

- Angeletti C, Guetti C, Paladini A, et al. Tramadol extended-release for the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. ISRN Pain 2013;2013:16 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/245346

- Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, et al. Tramadol for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:543-55

- Reig E. Tramadol in musculoskeletal pain–a survey. Clin Rheumatol 2002;21(Suppl 1):S9–11; discussion S12.

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, et al. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The chronic osteoarthritis management initiative of the U.S. bone and joint initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;43:701-12

- McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363-88

- Derry S, Cooper TE, Phillips T. Single fixed-dose oral dexketoprofen plus tramadol for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database System Rev 2016;9:CD012232