Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is a public health concern affecting 20–30% of the population of Western countries. Focus groups of people with persistent pain indicated that their overall physical function had deteriorated because of pain, therefore assessment of function should be an integral part of pain assessment. The objective of this study was to establish a consensus on assessment of function in chronic pain primary care patients and to evaluate the use of scales and clinical guidelines in clinical practice.

Methods

A Delphi study (CL4VE study) was carried out. A group of primary care physicians, were asked to rate how strongly they agreed/disagreed with the statements in: general functioning data, and functioning outcomes in chronic pain patients.

Results

Seventy-one primary care physicians were invited to participate. Of these, 69 completed Round 1 (98.5% response rate), and 68 completed Round 2 (97.1%). Under the predefined criterion, a high degree of agreement (91.4%) was observed, this was confirmed in 32 of 35 questions in the second round. Discrepancies were noted, firstly, because functioning was only linked to joint recovery; secondly, in the use of specific scales and questionnaires to measure functioning, and thirdly, that no scale of functioning is used in clinical practice due to complexity and lack of time for assessment.

Conclusions

Physicians agreed on the need for a precise definition of the concept of patient functional impediment to facilitate homogeneous recognition, and for the development of simple and practical scales focused on patients with chronic pain and their needs.

Introduction

Chronic pain is a cause of discomfort and disability that affects a significant percentage of the population worldwide (prevalence ranges from 10% to 30%)Citation1–3. One in six people is estimated to suffer from chronic pain, and they represent up to a 50% of primary healthcare centre consultations in Spain. Most of the medical consultations (up to 80%) are resolved in the primary care setting and the rest are referred to specialists or pain units (PU)Citation4,Citation5.

In addition to the physical symptoms, pain can seriously affect the mental and psychological health of patients. Chronic pain affects cognitive processes such as learning, perception, memory or attentionCitation6,Citation7. This was confirmed using a pan-European survey (15 countries) devised to provide information on the overall impact of chronic pain, where around 40% of respondents felt that their pain prevented them from concentrating, made them feel helpless and meant that they could not function normallyCitation3. Therefore, functioning and quality of life of chronic pain patients deteriorate significantly.

One of the main obstacles in chronic pain treatment is the complex mix of pathophysiological and biochemical factors plus the social, psychological, and economic challenges that patients suffer with their diagnosis. Therefore, when developing a comprehensive treatment strategy, it is very important to identify the specific individual needs of each patient. In the case of chronic pain, treatment should not just focus on reducing pain intensity, it is also essential to consider both the effects on the patient´s functional capacity and their quality of lifeCitation4,Citation8.

Establishing a treatment strategy in a multidisciplinary team, bringing together pain management specialists, psychiatrists and physiotherapists, seems the way to provide a comprehensive approach to the treatment plan, to provide better treatment involving all subdomains affected by the patient’s pain. In this context, each member of the interdisciplinary team will conduct the examinations and diagnoses of the patient, which will then be discussed and compared to draw up a consensual strategyCitation8.

Ideally, the first step in clinical practice should be to identify the underlying cause of the pain, once this is found a treatment strategy can be established, if the specific cause cannot be identified, it should be treated symptomatically so as to improve the patient’s quality of life. To support and facilitate this process, there are a series of international guidelines such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)Citation9. However, taking into account its extent, complexity (it consists of more than 1400 categories) and the individualized experience of pain, its subjectivity and the series of genetic, interpersonal and psychologic factors influencing it. It is not easy to implement in routine clinical practiceCitation10.

Currently, the clinical scenario that targets improving functioning aspects of patient wellbeing is not well-defined when dealing with chronic pain. Efforts are necessary to continue searching for new approaches in primary care settings. The objective of this study is to reach a consensus on the importance of assessing functioning in every patient with chronic pain attending primary care and to evaluate the use of scales and the application of clinical guidelines in daily clinical practice.

Methods

A two-round Delphi study (“The Cl4ve Study”) was conducted within the framework of Spanish public primary care centres attending patients with chronic pain in their routine daily practice. The primary objective of the study was to review the role of improving functioning as a therapeutic objective in the approach to patients with chronic pain. The Delphi method is recommended for use in the health care setting as a reliable means of determining consensus for a defined clinical problemCitation11,Citation12.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research at the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro (PI-19/20) (Spain).

Study procedures

The study was conducted in three phases; (i) scientific committee convened to establish the statements for inclusion in the evaluation, and selection of the panel of experts, (ii) two rounds of Delphi consensus surveys based on a web format, and (iii) a final virtual meeting of the scientific committee to draw up final conclusions.

Phase I: A multidisciplinary expert panel (scientific committee) was composed of 6 Spanish renowned professionals, two specialists in family and community medicine, a traumatology and orthopaedic surgery, a physical rehabilitation and a pain management specialists, all of them with extensive experience in the care of patients with chronic pain. Statements for inclusion in the study were selected by the scientific committee based on their experience and a comprehensive search from textbooks of the clinical specialties and published literature (original research articles). See Supporting Material Appendix 2 for search strategy. An initial list of main points was developed and after consultation for comments, these were then modified and approved as the first draft of the questionnaire. Statements were grouped according to two main areas: those that evaluated functioning with pain “Functioning outcomes”; and those evaluating scales and clinical guidelines in the approach to chronic pain in “Use of specific scales and guidelines”. In addition, physicians were asked to provide the functioning and pain scales they routinely used.

Phase 2: Delphi study. A second group of primary care physicians (n = 71), all of them active with relevant clinical experience and a stated interest in the assessment of chronic pain were invited to participate in the study through an electronic information leaflet with a full description of the objectives and characteristics of the survey. The 70 who expressed interest in participating were emailed and provided with an internet link to the online questionnaire. A consent form was completed electronically and sent with the questionnaire. Members of the scientific committee did not participate in the Delphi surveys.

First round. The first Delphi survey was conducted from 20 July to 25 September 2020. Participants were asked to rate each statement (n = 35) according to their degree of agreement based on a 5-point Likert scale (disagree, partially disagree, partially agree, agree or strongly agree). The study questionnaire is described in the Supporting Information Appendix 3.

Second round. Participants were provided with the two most frequent responses from the first round and were asked to re-grade the statements. The second round took place from 14 October to 19 November 2020.

Phase 3: Delphi Conclusions. In this phase, the scientific committee met again to review the results from the two rounds and draw conclusions based on the degree of agreement reached.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables.

Responses to the 35-statement questionnaire are Likert-type variables that range from disagree to strongly agree (from 1 to 5 respectively) and have been described numerically using measures of central tendency and dispersion: mean, median, mode, standard deviation and quartiles. It was considered that the measure best representing the group opinion was the median, since it expresses the central tendency of the response and from it, the 2 quartiles that allow the dispersion to be assessed were obtained: the first quartile (q1) and the third quartile (q3). The difference between both quartiles (q3–q1) is intended to measure the dispersion of the sample, being inversely proportional to the group consensus, that is, the higher the range, the lower the consensus. In this context and according to the literature, unanimity is achieved when this difference is equal to 0 and an acceptable degree of convergence (consensus) was considered among the experts when the IQR (Interquartile Range) ≤1Citation13,Citation14. Coefficient of variation (in percentage, CV) was used to describe the degree of dispersion of the sample, the higher the CV, the greater the dispersion and the less homogeneity.

Data were analysed using the SAS statistical program (Statistical Analysis Systems, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) version 5.2.

Results

Participants

Out of the 70 expert group members surveyed the response rates were 98.5% (n = 69) and 97.1% (n = 68) for the first and second round, respectively. The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Gender and workplace distribution was consistent in the two rounds. The geographical distribution of the 68 participants was the following: Andalucía (12, 17.6%), Madrid (9, 13.2%), Cataluña (9, 13.2%), Valencia (8, 11.8%), Castilla León (6, 8.8%), Galicia (5, 7.4%), Basque Country (4, 5.9%), Castilla La Mancha (4, 5.9%), Canary Islands (3, 4.4%), Aragón (2, 2.9%), Extremadura (2, 2.9%), La Rioja (1, 1.5%), Cantabria (1, 1.5%), Balearic Islands (1, 1.5%) and Murcia (1, 1.5%).

Most respondents stated that of the patients they attend, between 50 and 75% are of working-age. When asked for the 3 most common chronic pain-related pathologies, cLBP (chronic Low Back Pain) and OA (Osteoarthritis) were reported the most frequent (98,5% and 95,6%), followed by radiculopathies and headaches in 38.2% and 35.3%, respectively.

General functioning data

Results for each question in the first and second rounds are summarised in .

Table 2. Consensus results for first and second Delphi rounds.

Very high percentages of agreement were obtained, particularly for the statements: “I consider the improvement of functioning as a key therapeutic goal/objective” (76.5% strongly agree); “My patients’ ability to work is affected by their chronic pain” (73.5% strongly agree). And even higher agreement for the comments: “Suffering from chronic pain affects patients’ emotional state” (88.2% strongly agree); “Chronic pain decreases the quality of life of patients who suffer from it, so pain reduction is important” (92.6% strongly agree); “Pain assessment should include, in addition to a clinical assessment, a psychosocial assessment” (86.8% strongly agree); and “Management of chronic pain should be individualised, bearing in mind not only pain intensity but also the patient’s functioning” (91.2% strongly agree).

Conversely, 89.7% of the experts showed disagreement with the statement “I do not consider it necessary to perform a specific evaluation of a patient’s functioning”.

Functioning outcomes in patients with chronic pain

In the first round, there was agreement in 88.9% (n = 16) of the 18 statements on the assessment of functioning in patients with chronic pain in GP and in 64.7% (n = 11) of the 17 statements formulated in relation to the assessment of scales and guides. The percentage of consensus increased in the second round to 94.4% (n = 17) for the first area and to 88.2% (n = 15) for the second area. See and for details of the different statements.

Table 3. Results for “Functional outcomes in patients with chronic pain”.

Table 4. Results for “Use of specific scales and guidelines”.

For the first area, 2 out of 18 statements (11.1%) did not reach a consensus in the first round (Statement 3 and 14). In the second round, there was still lack of consensus for the consideration that functioning is only associated with joint recovery (statement 3) ().

Use of scales and clinical guidelines

A level of consensus of 64.7% was reached in the first round. Once the second round Delphi assessment was finished, consensus increased to 88.2%. Lack of consensus remained on the statement 22 referred to the use of specific scales and questionnaires to measure patient functioning “I use specific scales and questionnaires to measure patients’ functioning, note scales and questionnaires used” and the statement 25 “I don’t use any scale of functioning because they are complex.” .

In addition, the group of experts was asked if they used scales to assess pain intensity objectively. All researchers pointed out at least one of them.

In addition, more than 70% of the experts expressed that they feel trained to assess functioning but pointed out that they do not use functioning scales due to lack of time, and, it is important to highlight, more than 67% said it was due to a lack of trained human resources or trained professionals (nurses, colleagues). It was noted that 55.9% partially agreed that they were able to assess patients’ functioning without scales using their clinical experience, while 42.6% partially disagreed, or disagreed with this statement.

Discussion

This survey study provides valuable insight and inputs of a sample of primary care physicians and other specialists, who provide care to chronic pain patients in daily practice. Despite a broad consensus was achieved in relation to functional outcomes assessment in chronic pain patients those are hardly ever used in primary care clinical practice.

Several published articles highlight the importance of evaluating the psychosocial and functional dimensions in the classification and management of people with chronic painCitation15–17. Other studies have collected data on the prevalence of chronic pain and have assessed the impact on functioning and chronic pain on patients’ quality of life in primary healthcare centre consultationsCitation7,Citation8,Citation18–21. However, patient cohorts, definitions, and scales used in the various studies are different, which hinders comparability and precludes drawing firm conclusions. In view of the lack of consensus, this study has sought to assess the key functioning aspects in the management of chronic pain patients.

An initial committee of experts developed a two-part survey with a list of 35 statements in Spanish. This was distributed to a group of general practitioners for scoring each statement in two rounds.

Regarding the first area, more than 70% of the experts strongly agreed that functioning should be a key element of the therapeutic objective. However, 95.6% of the experts agreed, or partially agreed, with the fact that this assessment requires time that is not available in daily practice.

Importantly, all agreed that chronic pain affects mobility, social life, emotional state, ability to work, activities of daily life, and patients’ quality of life. Notably, psychosocial assessment is highlighted as a valuable tool in addition to clinical assessment in the management of the chronic pain patient.

Nearly all experts (97.1% (55.9% strongly agreed)) considered the motivational interview as an essential tool in pain assessment. Notably, experts strongly agreed (> 90%) that pain management should be individualised, considering not only pain intensity but also its impact on functioning.

Expert responses stress the importance of patient inclusion and the consideration of patient´s expectations in the strategies design for the management of the disease. Lastly, experts agreed (> 60%) chronic pain patients have associated comorbidities.

For the second area, more than 70% of the experts agreed that they used scales to assess pain intensity objectively, however, when questioned about functioning scales, great dispersion was observed in the answers provided with no predominant option.

Experts agreed they use pain management clinical guidelines in clinical practice and consider them useful and practical, allowing easy patient classification according to the type of pain. They also confirmed they are up to date on the latest published treatment guidelines. Unexpectedly, they agreed (> 70%) that there are limitations when selecting the ideal treatment for each patient and that they find it difficult to develop a treatment plan. Future research should focus on the reasons that prevent from individualizing therapeutic strategies based on the individual characteristics and comorbidities of the patients.

Finally, they disagreed (>70%) with the fact that it is not necessary to perform a specific assessment of patient’s functioning, only to focus on decreasing pain intensity without considering functioning itself and to establish a scheduled patient follow-up.

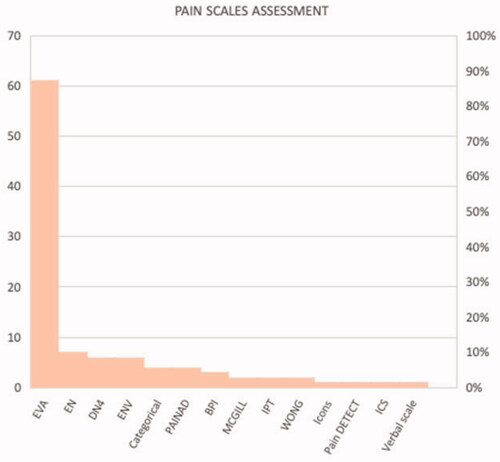

All doctors completing the survey remarked that they used at least one scale to assess pain intensity objectively. Most frequent were simple, visual, and quick-to-administer scales: the EVA (VAS) (89.7%), EN (NPRS) (10.3%), DN4-questionnaire and ENV (VNS) (8.8% respectively). ( and S3 Assessment Scales Description in Supporting Material)

The same answers were not given for the assessment of functioning. Some 19.1% of the experts specified they did not use any scale to assess the functioning of patients with chronic pain.

Quantifying the degree of consensus among experts is an important component of Delphi’s data analysis and interpretation. The IQR is often used as a consensus measure due to its robustness as a statistical measureCitation21,Citation22. The IQR is the range where the mean 50% of the assessments provided are located. According to Bryman and CramerCitation22, this measure is more robust and less sensitive to isolated cases. There are many criteria to establish for the experts to reach a consensus. In fact, depending on the scales used, different thresholds for the IQR can be defined to indicate that consensus has been reached among expertsCitation23,Citation24. In the present study, the consensus criterion adopted was when IQR ≤1 was reached. Under the predefined criterion, a high degree of agreement (91.4%) was observed with the statements selected from the bibliography, being confirmed in 32 of the 35 questions posed in the second round.

Discrepancies with opinions at the two extremes were obtained for three of the statements; firstly, the fact that functioning was only linked to joint recovery, which seems to demonstrate the need for targeted training in this topic. Secondly, in the use of specific scales and questionnaires to measure functioning, and thirdly, in the statement that no scale of functioning is used due to its complexity. This was identified as a crucial issue for improvement by the scientific committee. It was pointed out that definition of functioning needs improvement as does the search for simple and useful assessment scales.

There are potentially a number of limitations inherent to consensus studies that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the results should be interpreted taking into account the observational and exploratory nature of the survey, the number of participants (which limits the representativeness of the study sample), and the use of a non-validated questionnaire. Secondly, the study took place in a primary care setting and it is important to emphasize that 67.6% of the physicians reported they attended between a 50–70% of working age patients in their primary care physician standard panel. Figures are in line with those provided by the INE (Spanish acronym for National Statistical Institute) (date of consultation July 2020) that gives a share of a 66% of working age population (16–65 years) at a national level. Likewise, no specific information was collected on the guidelines of scientific societies, or the guidelines and care processes for pain care in the Autonomous Communities used by experts, with and without assessment of functioning. This point may be the objective of future studies on the functioning-chronic pain binomial.

One of the strengths of this study is that for this Delphi exercise the source of information used has been primary care physicians in active practice with extensive experience in managing chronic pain patients. As stated by Hasson et al. 2000 the commitment of participants to complete the Delphi process is often related to their interest and involvement with the question being examinedCitation25. Therefore, participants were selected for a purpose; to achieve a representative sample of physicians whom could apply their knowledge or expertise to chronic pain management within the confines of the area to be investigated in the Primary Care setting.

During the study, anonymity was maintained in order to avoid negative or positive influences from the dominant members of the group. Importantly, the response rate was high and in the two rounds it remained above 97%. With the feedback offered from the first round, we have sought to obtain convergence of a consensus opinion and this is confirmed in the results of the second round. Although not specifically studied, extrapolating the conclusions to older adults could result in an additional benefit since functionality improvement is expected to impact on quality of life (QoL).

Conclusions

In this study, a panel of experts was able to reach a consensus on most of the statements explored. In general terms, it was concluded that it is critical to incorporate the improvement of functional outcomes as a therapeutic objective in the management of chronic pain, for which it is necessary to overcome certain current limitations. There was agreement that functional recovery could provide even more valuable information than pain intensity measures. After analyzing the results, the experts identified the need for a precise definition of the concept of functioning and the development of simple and practical assessment scales or tools with three to four items for use in the short time usually allocated to the patient in daily clinical practice, focusing on the patient with chronic pain and their needs.

This information can help in future debates and frameworks around the development of guidelines and scales in the assessment of patients with chronic pain in primary care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Grünenthal GmbH. Editorial support for the writing of this article was provided by Alphabioresearch, and was funded by Grünenthal GmbH. The authors retained full editorial control over the content of the article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they are a consultant for Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Nevro.

Author contributions

JS, DR, AA, CM, PS, MS were involved in the conception and design of the study.

The statistical department of Alphabioresearch was responsible for the statistical analysis of the data. JS, DR, AA, CM, PS, MS and AAl were involved in the final interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper or revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution made by Marta Ruiz (alphabioresearch) during the statistical analysis of the data, and also wish to thank panellists to participate answering to questionnaire for the scientific purposes of this research.

The panel of experts, see list under Supporting material S1.

References

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and High-Impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006. Available from:

- Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273–e283.

- Van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH. Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):13–18.

- García Espinosa MV, Prieto Checa I. [Non-oncologic chronic pain: Where we are and where we want to go] . Aten Primaria. 2018;50(9):517–518.

- Torralba A, Miquel A, Darba J. Situación actual del dolor crónico en España: iniciativa “pain proposal”. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2014;21(1):16–22.

- Nueva Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE-11) y el dolor crónico [WWW Document], n.d. https://www.dolor.com/nueva-clasificacion-internacionalenfermedades.html.

- Ortiz L, Velasco M. Dolor Crónico Y Psiquiatría. Rev Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2017;28(6):866–873. Available from: https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmclc.2017.10.008

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. What do clinicians consider when assessing chronic low back pain? A content analysis of multidisciplinary pain Centre team assessments of functioning, disability, and health. Pain. 2018;159(10):2128–2136.

- Røe C, Sveen U, Cieza A, et al. Validation of the Brief ICF core set for low back pain from the Norwegian perspective. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(3):403–414.

- ICF Research Branch. https://www.icf-research-branch.org/download.

- Dalkey NC. The Delphi method: an experimental study of group opinion. Rand corp public RM-58888-PR. Santa Monica: Rand Corp; 1969.

- Graham B, Regehr G, Wright JG. Delphi as a method to establish consensus for diagnostic criteria. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(12):1150–1156.

- Rowe G, Wright G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: issues and analysis. Int J Forecast. 1999;15(4):353–375.

- Turk DC, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, et al. Assessment of psychosocial and functional impact of chronic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(9 Suppl):T21–T49.

- Taylor AM, Phillips K, Patel KV, et al. Assessment of physical function and participation in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(9):1836–1850.

- Lemos B de O, Cunha A. D, Cesarino CB, et al. The impact of chronic pain on functioning and quality of life of the elderly. Braz J Pain. 2019;2(3):237–241.

- Calsina-Berna A, Moreno Millán N, González-Barboteo J, et al. Prevalencia de dolor como motivo de consulta y su influencia en el sueño: experiencia de un centro de atención primaria. Aten Primaria. 2011;43(11):568–575.

- Cabrera-Leon A, Cantero-Braojos MÁ. [Impact of disabling chronic pain: results of a cross-sectional population study with face-to-face interview] . Aten Primaria. 2018;50(9):527–538.

- Langley PC, Ruiz-Iban MA, Molina JT, et al. The prevalence, correlates and treatment of pain in Spain. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):367–380.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–333.

- Landeta J. El método Delphi. Barcelona: Ariel; 1999.

- Bryman A, e Cramer D. Análise de dados em ciências sociais - Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS. Oeiras: Celta Editora; 1993.

- Linstone HA, Turoff M. Delphi: a brief look backward and forward. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2011;78(9):1712–1719.

- Von der Gracht HA, Darkow I-L. Scenarios for the logistics services industry: a Delphi-based analysis for 2025. Int J Prod Econ. 2010;127(1):46–59.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015.