Abstract

This paper explores disappearing vernacular architecture in the Karachay region (Karachay-Cherkessk Republic, Russian Federation). Recent research at the University of West Bohemia in cooperation with Karachay-Cherkessk University focused on the last preserved examples of block buildings in the mountain villages of Greater Karachay in the central Caucasus. Such buildings mostly disappeared in the late twentieth century due to both the Stalinist deportation of the Karachay people and modern development. Dendrochronological evidence has helped to date the surviving vernacular buildings to the late eighteenth to early twentieth centuries. Interviews with local inhabitants revealed the cultural context of the traditional housing and attitudes towards it. Possibilities for tracing cultural links and elucidating the historical context of this neglected building culture are also discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The Department of Archaeology at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen has organised several research expeditions to Karachay-Cherkessia in 2013–19 in close cooperation with the Karachay-Cherkessk State University. The research explored a variety of topics, such as the identification of cultural connections between Europe and Asia in the Middle Ages and interactions between sedentary communities and nomadic groups. In the mountain villages of Greater Karachay, ethno-archaeological research focused on material traces of the recent past represented by deserted settlements and farms, and included a survey of the last preserved examples of little-known archaic log buildings that are the subject of this study.Footnote1

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

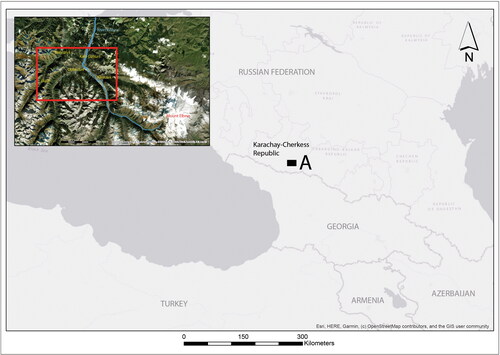

Karachay is a historical and ethno-cultural region in the central Caucasus situated north-west of Mount Elbrus along the uppermost conflux of the Kuban River and its tributaries (). The Karachays, whose Karachay-Balkar language belongs to the Turkic branch of the Uralo-Altaic languages, makes up the largest part of the population of the Karachay-Cherkessk Republic of the Russian Federation.Footnote2 It is assumed that the Karachays descended from Turkic people who came to the steppe planes north of the Caucasus in several waves from Central Asia during the early Middle Ages; however, the formation of this ethnic group may have also been influenced by the local Caucasus population.Footnote3 The region belonged to medieval Alania, which was attacked by the Mongolian invasion in the 1220s and 1230s and was destroyed in the 1390s by Timur’s military expeditions into the North Caucasus. Islam began to supplant Christianity in the region during the late medieval and early modern period.Footnote4 The Karachays may have been mentioned for the first time in 1404 as the ‘Kara-Cherkess’ (Black-Cherkess), living in the central Caucasus Mountains.Footnote5 The Karachay Principality was probably formed in the fifteenth century, and it developed under the influence of Ottoman Turkey and the Crimean Khanate in the early modern period.Footnote6

Figure 1. Karachay-Cherkess Republic of the Russian Federation (A and the red rectangle shows the location of the study area—Greater Karachay) (map by P. Vařeka; source ArcGIS Basemap Online)

In the eighteenth century, the northern Caucasus became a zone of increasing political and military struggle between Russia and Turkey. The Russian imperial army began to advance systematically into the territory of Karachay-Cherkessia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. After several military engagements, the Karachays were defeated in the Battle of Khasaukinsk in 1828.Footnote7 The principality was annexed to Russia, the elite were forced to swear allegiance to the Russian Empire and the people became the tsar’s subjects. Colonial domination led to conflicts and resistance; however, the subjugation of the northern Caucasus by Russia was completed by 1864. As a manifestation of their disapproval with colonial rule, many Karachays, as well as members of other nations, left the region and moved to parts of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote8

Extensive influences from European Russia spread throughout the region, permanently affecting traditional culture and society, as well as the local economy. After the October Revolution, the Karachay-Cherkessk Autonomous Area of the Soviet Union was established in 1922, from which the Karachay Autonomous District was detached in 1928. The Karachays were heavily affected by the Stalinist purges of 1936–8, especially the elite.Footnote9 During the Second World War, the Karachays were accused of collaborating with the German Army during its advance into the central Caucasus in 1942. Based on unfounded charges, a collective sentence fell on the whole population, who were deported to central Asia in November 1943. The autonomous district was dissolved, the territory divided between the Russian and Georgian Soviet Republics, and overrun by new settlers. Following the death of Stalin, the Karachays were allowed to return to their homeland in 1957, when the Karachay-Cherkessk Autonomous District was re-established. Full rehabilitation was not granted until the Gorbachev era in 1989–91.Footnote10 In 1992, the Karachay-Cherkessk Republic was declared a part of the Russian Federation.

SETTLEMENT, ECONOMY AND TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

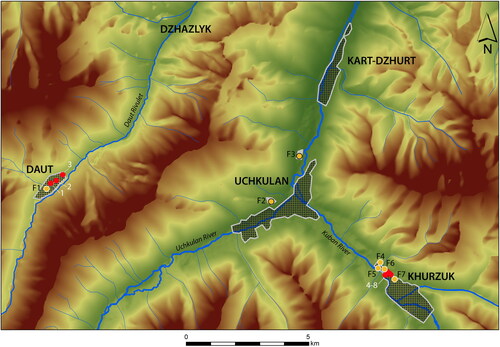

Greater Karachay is situated at the north-western foot of Elbrus, the highest Caucasus mountain (5642m), and consists of five mountain settlements ():Footnote11 Kart-Dzhurt, Khurzuk and Uchkulan are located in the Kuban river valley (1200–1480m above sea level); Daut and Dzhazlyk are located in the side valley of the Daut rivulet (1520–1850m above sea level).Footnote12 The earliest census from the 1860s provides not wholly reliable data on the Karachay population, which may have peaked at around 18,000.Footnote13

Figure 2. Greater Karachay showing the location of buildings mentioned in the text. The numbering system includes traditional farms which consisted of several components (prefixed by F) and isolated log buildings which were not associated with original farms (numbers with no prefix) (map by J. Chaibulin-Koštial and P. Vařeka)

Unlike some other Caucasus areas, the Karachay villages are not hilltop settlements, but are situated in the narrow valley floors stretching several kilometres in length (). Defensive stone-built towers, which are a typical feature of many Caucasus settlements, are found only in Khurzuk and Uchkulan (one tower in each village); however, they are situated outside settlement areas on the tops of strategic hills overlooking the whole micro-region.Footnote14 Villages consisted of several quarters (tiire), which were inhabited by members of one clan (tukum) and had their own mosques and cemeteries.Footnote15

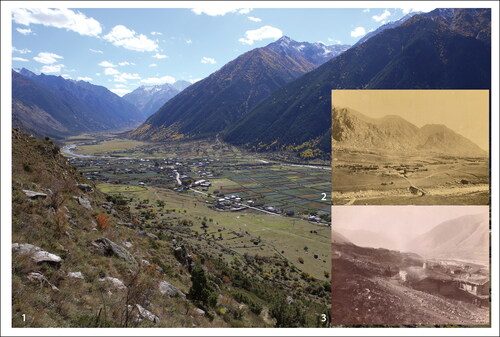

Figure 3. 1) Khurzuk. General view from the guard tower at Mamiya Kala looking towards the south-east (photo by P. Vařeka); 2) Khurzuk. View from the west (beginning of the twentieth century); 3) Kart-Dzhurt. View from the north (beginning of the twentieth century) (courtesy Khanafi Khasanov)

The traditional economic system of the Karachays was based on cattle farming, which utilised natural grazing resources in both montane and sub-montane zones. Herds consisting of large-horned cattle, horses, sheep and goats grazed on the high summer grasslands (dzhailyk) from June to August and spent the winters in the valleys or foothills of the Caucasus or in the lowlands (kyshlyk). The Karachays gained a great reputation in the nineteenth century as pastoral farmers, both for their dairy production and the cattle bred in the region. Pastoralism was complemented with montane agriculture.Footnote16 Forced collectivisation in the late 1920s and 1930s heavily affected the traditional social and economic system, as many industrial complexes of cooperative farms (kolkhoz) and state farms (sovkhoz) were built in the region.Footnote17 Many of these are currently empty and ruined due to the restitution of private farming in the 1990s.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both travellers and scholars had noticed that Karachay vernacular architecture differed from other building traditions in the Caucasus for its impressive block timber construction and earth-covered roofs.Footnote18 The only similar traditional housing can be found in the Baksan Valley east of Mount Elbrus, which is inhabited by the culturally and linguistically related Balkars.Footnote19 Although descriptions of Karachay architecture have been published, as yet, there has been no detailed survey, nor any attempt to explore the origin of these buildings.Footnote20

Until the late nineteenth century, the basic type of Karachay dwelling was a two-compartment rectangular house (ullu yui = big house) built of logs. A gabled roof was covered with a thick layer of earth. Farms comprised several log houses and outbuildings, such as byres and stables.Footnote21 They were designed to accommodate a large patriarchal family comprising parents, grandparents, children and the families of all married sons. In addition to the dwelling house, there was a separate house for guests (konak yui), and smaller, houses for older children and their families (otoy), or separate rooms for those who lived in the parents’ ‘big house’.Footnote22

Distinctive farms having covered yards (bashi dzhabyl’gan arbazy) were preserved in a few cases down to the twentieth century. These unique settlement units were considered to be prestigious ancient structures, reminiscent of fortresses. They were of a rectangular plan with an area reaching up to several hundred square metres. The central yard, which was covered completely with a roof, was lined with houses and outbuildings of block construction adjoining one another. The heavy roof above the yard was topped with a thick layer of earth and rested on load-bearing posts and block-pillars. Narrow openings, reminiscent of arrow loops, were placed in corners of the yard, providing some daylight.Footnote23

As a seasonal dwelling connected with the summer grazing of cattle and horses in the sub-alpine or alpine zone, a chalet (koshk) was used. Whole villages emptied in late May, and most families spent the summer in the mountains until early September. Usually only the oldest family members stayed in the village houses during the summer. Chalets were typically single-roomed buildings, the construction of which depended on locally available material.Footnote24

Wide-ranging colonial domination had a strong impact on the traditional Karachay culture, including its vernacular architecture. Since the late nineteenth century, Russian-style houses began to be adopted by local communities, initially by wealthy families. New houses can be characterised as square, two-storeyed, multi-room buildings of timber and masonry construction. The ground floor, which fulfilled mostly economic functions, was stone built. Newly introduced water-powered saw-mills produced the timbers used for the construction of the upper floor. Porches along one or more sides of the upper floor, originally accessed by external steps, represent a typical feature of these houses at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as well as large, glazed windows and hipped or gabled roofs covered with metal sheets.Footnote25

FIELD RESEARCH

AIMS AND METHODS

A survey of mountain villages in Greater Karachay was carried out during three expeditions, in 2013, 2014 and 2016. The research focused on five main areas: 1) the contemporary state of preservation of the specific log-building tradition; 2) a detailed examination of the farms, building forms, construction techniques and the spatial organisation of the log houses; 3) dating the log architecture; 4) the perception of the log houses among contemporary communities; and 5) contextualising the log houses’ tradition in the northern Caucasus. In the first phase, the survey of mountain villages detected preserved log houses which were documented photographically and located using GPS. Accessible buildings were sampled for detailed study, which included a building survey, plan documentation and, in selected cases, photogrammetry. Where possible, samples for dendrochronological dating were taken from different sections of the buildings.Footnote26 In the case of deserted farms, which survive as archaeological sites, standard techniques of non-invasive surface and topographic survey were used.

LOCATION AND PRESERVATION OF LOG BUILDINGS

The villages of Kart-Dzhurt, Khurzuk and Uchkulan, which are situated on the Kuban river valley are inhabited, although some houses are abandoned and the remains of deserted farms can be seen on the margins of the villages. The settlements in the valley of the Daut rivulet are mostly deserted due to the deportation of Karachays in 1943. Dzhazlyk is completely abandoned and partly overgrown with vegetation, and its location is marked by the surface remains of the former farms and field systems. The village of Daut is partly deserted, but some buildings are still used, especially during summer grazing.

The largest concentration of log architecture was found in the western section of the village of Khurzuk, where four farms were studied. Two of these were completely abandoned, and the incomplete remains of the other two were situated next to modern inhabited houses. In addition, another five log buildings were found within inhabited farms. These were used as byres or incorporated into later building complexes. The building survey in Daut produced information regarding one abandoned farm consisting of two log houses and the preserved remains of three other buildings. In Uchkulan, the whole westernmost quarter of the village has been deserted, including a cemetery which was intentionally destroyed after the deportation of Karachays. The only deserted farm in which log buildings have been partly preserved was selected for survey, using both building survey and non-invasive archaeological techniques. In addition, one abandoned farm at the northern edge of the village was documented (). Archaic log houses have not been identified in the village of Kart-Dzhurt. A reconstruction of a traditional block house was built by master carpenters here in the 1980s as a memorial to the local scholar U. A. Aliev, who was executed during Stalinist purges in 1937 and after whom Karachay-Cherkessk University was later named. The building represents a copy of Aliev’s birthplace (he was born in 1895) and is a good representation of an archaic log house unaffected by later reconstructions (: 1).

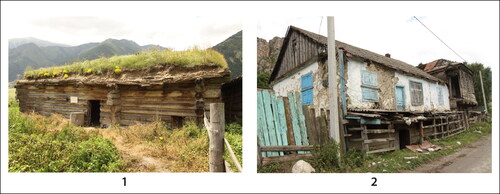

Figure 4. 1) Reconstruction of U. A. Aliev’s birthplace in Kart-Dzhurt (1980s). 2) Modern timber house in Khurzuk, built on top of the earlier log house, which has been dated to 1894+ (K-5) (photos by P. Vařeka)

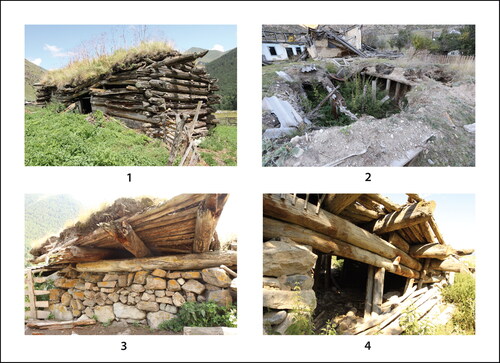

All 26 of the log buildings studied were in very poor condition or ruined. Nineteen were situated within inhabited farms, and a few were still in use as byres. A number of abandoned houses were also being used as byres.

The owners of these buildings, and other local people, perceive log houses as an important part of their history and cultural heritage, of which they are very proud. Many families consider the original block houses as ‘family monuments’ and have preserved these buildings within their farms. Furnished with new, large windows, modern ovens and other innovations, some log houses were still in use during the twentieth century, but are now abandoned. Some were given a new function, with cattle housing on the ground floor and a new floor above (: 2). Others were used as separate outbuildings. However, oral testimonies have shown that old log houses were in most cases dismantled and their building material reutilised during the twentieth century. The Stalinist deportation caused the ruthless devastation of mountain villages by new settlers in the 1940s and 1950s, including the use of many farms as a source of building material or firewood.Footnote27

Despite the strength of feeling towards these buildings in the area, there appears to have been no systematic attempt to protect or conserve the log architecture in Greater Karachay. The owners use various improvised techniques to preserve the buildings, such as the inclusion of posts to support the roof frame or covering roofs with metal sheets. Rapidly progressing decay caused by the harsh mountain climate was documented during the survey period. Some of the buildings which were nearly intact in 2013 had totally collapsed by 2019. It seems inevitable that most of the block houses will soon disappear.

FARMS

The mountain environment shaped settlement forms of a typical linear pattern with farms situated along main or side roads. Narrow valley floors provided only restricted areas for farms, which were mostly built in the sloping terrain. The village quarters originally associated with kinship (tiire) can be still recognised. The farms ranged in size from 1600m2 to 5700m2. Vegetable gardens and orchards were situated behind the built-up section of the plot, followed by a narrow zone of former fields interwoven with irrigation ditches, which are currently used as pastureland.

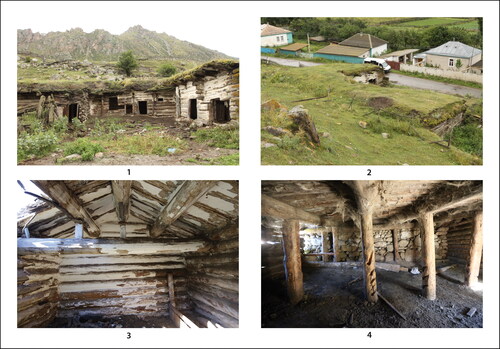

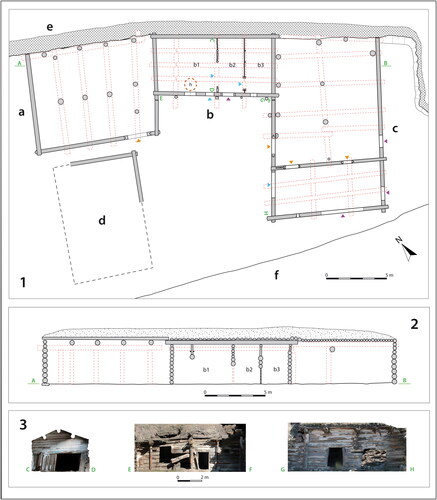

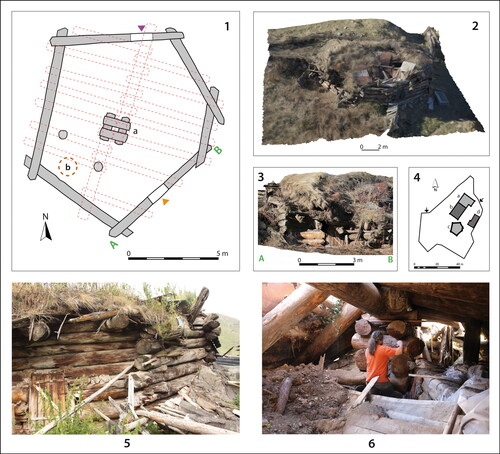

Most of the farms studied were rectangular or polygonal in plan and were demarcated by stone or wooden enclosures. A U-shaped plan was recorded in only one farm (: K–F1; and ). The farm was built into a hill on an artificial terrace, reinforced by a wall built of large stones. The mostly ruined farm complex had a plan of 18m by 30m with two wide side-wings used as byres (at orun) and stables (bau) and a narrow rear wing formed by a dwelling house (ullu yui) (). The longer axis of the yard is oriented towards the road (south-south-east), where a gate must have been originally placed. According to dendrochronological dating, the dwelling and the western wing were probably built in 1852/3, and the eastern wing was likely added in 1856/7.

Figure 5. Farm in Khurzuk (K-F1). 1) View into the yard from the south-west. 2) View from the north-west taken from the upper terrace. 3) Interior of the dwelling house (north-western part of the dwelling room). 4) Byre (western wing) (photos by P. Vařeka)

Figure 6. Khurzuk (K-F1). 1) Plan of the farm: a – byre (1852/3); b – dwelling house (b1 – dwelling room, b2 and b3 – storage rooms, h – probable placement of the heating equipment; (1852/3); c – byre and stable (1852/3); d – ruined outhouse; e – stone wall (revetment of the terrace); f – road; orange triangles – original entrances; blue triangles – adapted original entrances; violet triangles – secondary entrances. 2) Cross-section of the northern part of the farm. 3) Photogrammetry of selected sections of the farm (plan by P. Vařeka and P. Netolický; photogrammetry by J. Chaibulin-Koštial)

The six other farms surveyed have an irregular clustered structure comprising the dwelling house and up to four outbuildings, primarily byres and stables. It is possible that there were additional outbuildings that are no longer extant. Separate dwellings were also documented: a separate habitation for married sons’ families (otoy) and a building for receiving guests (konak yui).

One completely preserved farm of an irregular polygonal plan (1590m2) was documented in Daut (: F1; ). It consisted of a gabled log house, dendrochronologically dated to 1871/2, with an annexed byre (5.4m × 22m), a recent shed situated on the other side of the yard, and a hexagonal log building in the back, which was later used as byre. This single-roomed building was dated to 1847/8 and, according to oral testimony, it represented the original dwelling house of the farm.Footnote28

Figure 7. Hexagonal log house in Daut (farm D-F1). 1) Plan of the hexagonal building D-F1-2 (a – block pillar; b – probable placement of the heating equipment; orange triangle – original entrance; violet triangle – secondary entrance (1848/9). 2) 3D model of the hexagonal house remains (2014). 3) Photogrammetry of the south-east wall. 4) Plan of the farm: a – dwelling (section of the later house dated to 1871/2; b – byre; c – hexagonal house; d – recent shed. 5) View from the south-east (2014). 6) Interior of the hexagonal house with the block pillar (plan and photo by P. Vařeka; 3D model and photogrammetry by J. Chajbulin-Koštial)

RECTANGULAR DWELLING HOUSES

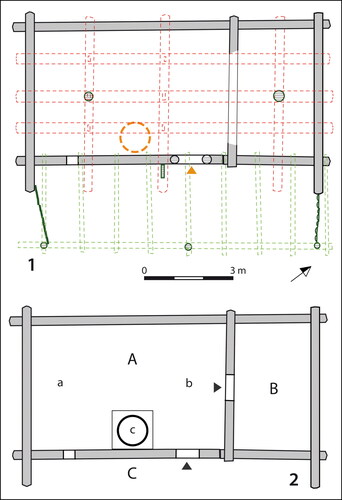

Thirteen dwelling houses were documented, eight of which were well preserved and five of which were partially preserved. Ten of these were dendrochronologically dated to the period from the 1790s to the 1890s. With the exception of one hexagonal house (see below), all of the houses had rectangular plans. Two main types of rectangular dwellings were identified. The first type is a freestanding building comprising a living area with a storeroom (: 1, 2 and F4; ). The reconstructed house in Kart-Dzhurt (U. A. Aliev’s memorial) is of this type (: 1). The second type comprises a living area plus storeroom with the addition of one or two more rooms (such as a byre or another living area) under the same roof (: F1–F3, F6; : 4). The farm complex in Khurzuk (: F7) bridges these two types, as the storage room is divided into two narrow rooms ().

Figure 8. Rectangular two-compartment log dwelling in Daut, later used as byre (D-1, 1877+). 1) Plan of the building (green lines represent later extension and constructions; orange triangle the original entrance). 2) Reconstruction of the internal structure of the house (A – dwelling room; B – storage room; C – porch; a – male section, b – female section, c – hearth) based on oral testimonies and ethnographic evidence (plan by P. Vařeka)

The houses were constructed of logs laid horizontally and interlocked at the crossed corners. Slots between individual logs were filled with daub. The straightness of available trunks limited the length of the walls to a maximum of 10m–11m. In both types of houses, the size of the dwelling unit (living area plus store) ranged from 4.2m–5.4m by 8.1m–11m, with a maximum area of 51m2. Where the size of the building exceeded the maximum length of timber available, additional rooms were tied in using tongue-and-groove or half-lap scarf joints. The maximum documented house length was 23m, comprising multiple joins.

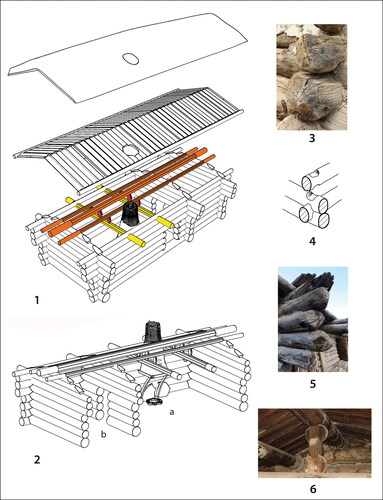

The timber used was pine (Pinus sylvestris), the diameter of which varied from 0.25m to 0.5m. Cradle joints were formed by simple half-round cuts or sockets (: 3–4). Dendrochronology dates the surviving timbers to the 1790s–1870s. This includes timbers which have clearly been cut by axe (e.g. : 3 and 9: 5) and those which have sawn straight ends (e.g. : 1, 2, 5 and 6); both techniques were in use throughout this period. Two rectangular holes cut with a chisel at one end of each log were used for threading the rope for the ox sled, which enabled the transportation of logs from the forest to the building site (interviews in 2013 and 2014; transcriptions of all interviews are deposited at the Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, University of West Bohemia, Plzeň/Pilsen). Logs were thoroughly stripped of bark and knots and laid in such a way that the side with the thinner annual rings faced the exterior of the house as this side would be more durable and resistant to rot. The discrepancy in taper was resolved by reversing the butt end of alternate logs. The house walls consisted of six to ten rows of logs reaching 2m to 3m in height. The log ends were usually exposed up to 1m in the uppermost section and 0.2m–0.5m in the lower section of the walls (). The log walls rested on simple stone foundations or footings. One house (U-F1-1) was built of half-logs, positioned with their flat side innermost. By the late nineteenth century, deforestation had led to a shortage of suitable timber for building and so half-logs began to be used. The dendrochronological dating of this house was not possible. However, the dating of the nearby byre of the same farm to 1912/13 (U-F1-2) corresponds with the suggested introduction of local saw-mills.

Figure 9. 1–2) Isometric drawings of archaic Karachay log dwelling (‘ullu yui’) based on reconstruction of the U. A. Aliev’s house reconstruction in Kart-Dzhurt (yellow – arkaı; orange – aralyk; red – maimul; a – dwelling room; b – storage room). 3–5) Examples of the log construction from Khurzuk with horizontal trunks interlocked at the crossed corners. 6) Traditional roof-frame with ‘maimul’ in Khurzuk (K-F4-2) (drawing by J. Chaibulin-Koštial; photos by P. Vařeka)

Figure 10. Log houses in Greater Karachay. 1) Khurzuk (K-2, 1794+). 2) Khurzuk (K-F3-1, 1848/49). 3–4) Daut (D-1, 1877+). 5) Khurzuk (K-1, 1850+). 6) Daut (D-F1-1, 1871/2 (photos by P. Vařeka)

Both types of dwelling have the same two-room plan comprising a main room with a smaller storeroom accessible from it (: 1b; ; : 1–2). The entrance (tysh eshik) faced mostly east, south-west or south-east. In several cases, the original entrance was a simple opening cut in the front wall. In some cases, two door-posts, around 1.5m high, and a door-sill (bosag’a) created by the lowest log, formed the doorframe (: 4). The original timber doors have not been preserved. The internal partition wall was of log construction, tied into the external front and rear walls. In some cases, the lower half of the partition was constructed with thinner vertical poles set into grooves in the lowest log and a sill beam resting on the floor.

The gable roof frame is an integral part of the block construction, comprising interconnecting transverse and longitudinal logs (: 1–2; : 3, 5 and 6). The gable end comprises horizontal logs interlocked with two log purlins (maimul) and a ridgepole (aralyk) (). The ridgepole was between 2.8m and 3.6m above the floor. These longitudinal load-bearing components are supported internally by two tiebeams (arkaı) with vertical struts supporting the purlins, and the internal partitioning wall. The maimuls (‘monkeys’), which are usually carved from thick boards, are typically convex, but sometimes straight. Each component of the roof frame had a strong sacral and symbolic meaning, as did the lowest row of logs and the hearth, all of which are reflected in various traditional proverbs and curses. For example, house offerings were deposited underneath the lowest log. The threshold that formed both the physical and symbolic barrier between the dangerous outer and inner, culturally adapted space, had to be crossed only with the right foot, and no one was allowed to step on it. The tiebeam is another sacred component of the house for it bears the roof. One of the worst curses is attached to it since its being broken means not only the destruction of the house, but also misfortune to the whole family.Footnote29

Half-logs placed with their flat sides down were laid between the wallhead and the ridgepole and secured by wooden pegs. An additional log was pegged to these along the wallhead. The roof cover comprised a layer of juniper branches and straw, on which was laid a thick stratum of earth, turf and charcoal to a depth of 0.5m–1m.Footnote30 The slope of the roof is about 30 degrees (: 1–2) and the earthen cover is held on each side of the roof by planks running along the wallhead and from wallhead to ridgepole at each end. The ends of the tiebeams and the logs protruding from the gables and the partition wall were used to support an extended roof that covered a narrow space along the front long wall forming a porch. This was used particularly in the summer, when housework was performed there (dzhatma).

The entrance led to the dwelling room, which was originally equipped with an open hearth (otdzhak) situated by the wall to the left of the door.Footnote31 The open hearth was replaced in the late nineteenth–early twentieth century by a cooking stove. Originally, there was only one small window (tereze) in the house, measuring approximately 0.3m × 0.5m, which was cut into the front wall. Larger windows were introduced from the late nineteenth century.Footnote32 The smaller room (gezen) was situated on the gable side furthest from the hearth and was accessed through a door from the dwelling room. It was used for the storage of food and valuables. The floor of both rooms was made of tamped clay mixed with chaff and straw. The interior walls were covered with a thin clay plaster and whitewashed with lime.

The original spatial organisation of the living room in the early nineteenth century ‘ullu yui’ can be reconstructed from ethnographic evidence and oral testimony (: 2; : 1–2).Footnote33 The room served as a kitchen, living room, dining room and bedroom and was symbolically (but not physically) divided into two parts. The ‘honourable’ or male part was situated behind the hearth. The large bed for the head of the family was placed here (muldzhar). It was stowed away, covered with felt mats and used for sitting on as a divan during the daytime. Weapons, musical instruments and a prayer rug were hung on the wall next to the bed and prestigious decorated dishes and festive clothing were also displayed here. Distinguished guests were received in this section of the house. The opposite part of the room, in front of the hearth, where both the entrance to the house and door leading to the storage room were situated, was ruled by the lady of the house (also considered the ‘firekeeper’). Wooden dishes and cooking wares were stored here, as well as other household equipment. The hearth, which was perceived as the sacral core of the house, was formed by a shallow pit lined with stones set into the floor. A metal kettle hung above the permanently burning fire, which was used not only for heating and cooking, but also to provide light. Smoke escaped through a wooden chimney, covered with daub, placed above the hearth (: 1–2). The lowermost part of the log wall by the hearth was protected from flames by large, flat stones. There was no fixed table in the dwelling room. Low, round three-legged tables with stools were set out at meal times and could be arranged according to the number of people who gathered in the room.

HEXAGONAL HOUSE

A hexagonal log house which was documented in the village of Daut was believed by locals to be the oldest building in the village.Footnote34 The surviving remains were dendrochronologically dated to 1848/9 (). This unique single-celled building was formed by six rows of thick logs, 0.3m–0.5m in diameter. The bottom log rested on stone footings and the ends of the logs extended at each corner. The length of individual wall sections varies from 2.9m to 8m, and they form different acute and obtuse angles. The external circumference was 35m and the total area of the building was 86m2. The original height of the walls was around 2.5m. The roof had collapsed, but it was possible to approximate its original construction. The roof frame was supported by a very specific load-bearing component situated in the centre of the hexagonal building, which was formed by a block pillar with dimensions of 0.9m by 1.3m; its original height was about 3.2m. It was constructed of seven pairs of very thick logs (0.48m– 0.61m in diameter) laid horizontally across, one on top of the other, interlocked at corners with their ends exposed by only a few centimetres. Two thick logs which were laid with one end on the pillar and the other resting on the top of the south-western and north-eastern walls constituted a ridge that formed the roof axis of the building. Nine rafters were laid on the ridge from both sides. This frame created an irregular semi-gable-pyramidal roof, and its earthen cover rested on thinner logs laid side by side on rafters parallel with the ridge.

The original spatial organisation of the dwelling is only indicated by a door facing south-east and the position of heating equipment by the western wall close to the western corner. This was indicated by two vertical posts that supported rafters but also a wooden chimney, the location of which is shown by a typical opening in the roof.

OTHER HOUSES AND OUTBUILDINGS

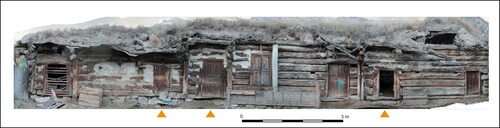

In most parts of the Caucasus, the houses of large families would typically include an otoy, a separate room or building that would house the married sons’ families. A well-preserved ‘long house’ (8.3m by 23m) consisting of three such rooms under the same roof was documented in Khurzuk (K-F3-2) and was dated to 1845/6 (). Separate guest-houses (konak yui) were a typical component of old farms in Greater Karachay and can be found also in other parts of Caucasus. One such feature has been preserved among the remains of another farm in Khurzuk (K-F4-2).

Figure 11. ‘Long house’ in Khurzuk (K-F3-2, 1845/6). Photogrammetry of the house elevation: orange triangles mark entrances giving access to the three habitation cores for married sons’ families (otoy). (photogrammetry by J. Chajbulin-Koštial)

In addition to dwelling houses, ten outbuildings (byres and stables) were also surveyed. Most of these were separate buildings, while some were attached to dwelling houses or larger building complexes. According to their form and construction, these outbuildings can be divided into four types: 1) log construction with gable roof (dating to the 1870s; : 1); 2) log construction with flat roof (dating to the 1850s; ); 3) combining stone, block and post construction and flat roof (one byre dated to 1912/13; : 3–4); and 4) sunken building with stone and post construction (one byre dated to 1905/6; :2).

ORIGINS OF THE KARACHAY TRADITIONAL HOUSING

In comparison with other building traditions in the Caucasus, the singularity of the Karachay vernacular architecture lies in its log construction, roof trussing and covering. There is limited evidence of log construction in some other parts of the Caucasus.Footnote35 These buildings can be found only in Greater Karachay and the Baksan valley, which were settled by ethnically related Balkars on the other side of Mount Elbrus. There is strong evidence to suggest mutual influences in Karachay and Balkar vernacular architecture. Many similarities can be found regarding the structure of farms and the internal organisation of traditional dwellings.Footnote36 Outside of the Baksan valley, the Balkars lived in rectangular houses of identical size and structure; however, the walls were mostly constructed of stone. The combination of stone walls, two or three rows of logs and flat roofs covered with earth and supported by thick posts, documented in the case of several outbuildings in Greater Karachay, is a typical feature of houses in neighbouring Balkaria to the east.Footnote37 The presence of Balkarian stonemasons, who frequently built massive constructions, was documented in the oral tradition in Karachay villages and, conversely, Karachay carpenters often worked in Balkaria.Footnote38 The distinctive block pillar which supports the roof of the hexagonal house in Daut is a widespread load-bearing component in Balkar vernacular architecture.Footnote39 Similar log pillars supported the roof covering the yard in bashi dzhabyl’gan arbazy farms in Karachay.Footnote40 Unfortunately, none survives.

Unlike its construction, the layout of the Karachay house is similar to vernacular architecture in neighbouring regions. Single-storey one or two-compartment post-and-wattle built houses of a rectangular plan of a similar size with a gable roof were a typical, traditional dwelling of the neighbouring Chelrkess, Kabardins,Footnote41 AbazinsFootnote42 and Adyghe people.Footnote43 Many attributes of the spatial organisation of the living room can be found in rural housing not only in the near regions of the western Caucasus but also in the eastern Caucasus, such as the multifunctionality of the living space and its division of the living room into male and female areas, and the use of similar heating equipment and furnishings.Footnote44

Scholars have suggested that in both Karachay and Balkaria the most archaic dwelling was the single-roomed square or rectangular house with an open hearth in the centre.Footnote45 The only one-compartment house documented by the present survey is the hexagonal building, the heating equipment of which was not situated in the centre where the log pillar was placed, but against the entrance by the wall. Earlier ethnographic research noted the prior existence of such polygonal log dwellings in Karachay villages; however, it was believed that these buildings had not been preserved.Footnote46 Tree-ring dating did not confirm the expectation of the house’s extraordinary old age shared among the local people in this highest and most distant village of the Greater Karachay. It showed that the building was constructed in the 1840s and was contemporary with rectangular houses, so that these two different house forms were used side by side.

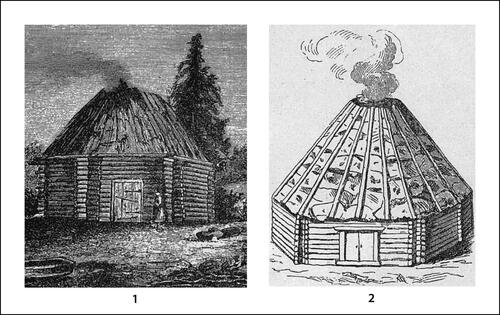

It seems that there is no other evidence of similar multi-sided houses in other parts of the Caucasus or neighbouring areas. The nearest analogies appear to be found 4000km further east in Altai in southern Siberia, where ‘log yurts’ were widespread among Turkic ethnical groups. Turkic nomads built both movable felt yurts and fixed buildings such as polygonal (mostly hexagonal or octagonal) timber-framed yurts with pyramidal bark or earthen roofs, which were used in winter settlements in forested areas ().Footnote47 The construction and size of these yurts is very similar to the Daut dwelling, with the only exception being the central log pillar and asymmetrical placement of the heating equipment by the wall.

Similarities can also be seen in the spatial organisation of the Turkic dwellings in Altai and living rooms of the Karachay houses in the Caucasus. The entrance providing access to the yurt was always oriented to the east. There is a strong inclination in orientation of the studied Karachay house entrances to the east, with some shifts to the south-west or south-east occasioned by the orientation of mountain valleys. In the Karachay house, the male area is to the left of the entrance (to the south); the female area is to the right (to the north). Turkic yurts of southern Siberia had an identical division of the internal space, with strong semantic opposites such as male/female, southern/northern, upper/lower or positive/negative. There are also many similarities in customs and rites connected with the traditional dwelling between Altai Turks and Karachays (and Balkars).Footnote48

Karachay log houses can be seen as evidence of complicated cultural processes regarding the built environment and as one of the key components of traditional material culture. The Caucasus, located on the boundary of Europe and Asia, has always been a crossroads for diverse cultural streams. Very specific cultural traces were left by various nomadic groups who penetrated along the Euro-Asian steppe zone from Central Asia and beyond in the Middle Ages. Pastoral nomads who settled in the steppes along the northern foothills of the Caucasus kept their way of life, including movable dwellings, until the modern era.Footnote49 In the mountain areas, pastoral farming occurred on hill slopes, with the adjacent lowland steppes providing winter grazing. The Karachay traditional house seems to have been developed from the influence of both the rural architecture of the local sedentary population and the nomadic dwelling. The rectangular house plan, its division into the dwelling room and storeroom, placement of the heating equipment by the wall, and furnishings are typical for many other house types in the northern Caucasus. On the other hand, the enduring occurrence of the single-celled multi-sided buildings, the internal layout of the house and its associated customs have more in common with the traditional dwellings of Turkic nomads in distant southern Siberia. This research has demonstrated that a hexagonal log yurt, similar to those in Altai, was built in the mountain village of Daut as late as the mid nineteenth century and that this type of dwelling was perceived as ‘ancient’ and ‘archetypal’ among local people. The distribution of structures using the impressive block building technique in Greater Karachay corresponds to the extent of one of the most densely forested territories of the Caucasus, a primeval pine forest, unaffected by massive deforestation until the nineteenth century, which provided a plentiful supply of logs. But it is probable that the monumental block architecture was not simply a response to the easy availability of materials but as much the product of the deeper cultural forces described above, since there are no analogies for the building form elsewhere in the region despite them being equally heavily forested.

CONCLUSIONS

This research documented a sample of the last remains of log architecture in three of the mountain villages of Greater Karachay. Except for a few examples of log construction that have been incorporated into later farm complexes, all of the houses and outbuildings that were identified are rapidly decaying, and hardly any preserved remains will be left in the near future. Log buildings are deeply embedded in the world view of the local families and are perceived as silent testimonies of a memorable but also troubled past. Although these components of the traditional built environment are acknowledged as valuable monuments of history and folk culture among local people, no steps have been taken towards their systematic protection and preservation.

Tree-ring dating showed that the log houses identified were built over the course of one century, between the end of the eighteenth and the end of the nineteenth centuries, with no apparent developmental changes regarding their form and construction. The documented outbuildings date from the 1850s to the beginning of the twentieth century. The absence of earlier log buildings is difficult to explain, as there are surviving examples of medieval and post-medieval block houses in several parts of Europe.Footnote50 It may be due, in part, to the impact of the Caucasian war in 1817–64 which saw the burning of mountain settlements during military operations, and the dismantling of mountain villages by new settlers in the 1940s and 1950s during the Stalinist repressions.

Historically, the north Caucasus was an area of mutual cultural influences between the sedentary population and nomadic groups. This complicated process also seems to be reflected in Karachay vernacular architecture. The concept of a multi-sided log yurt, widespread among nomads in southern Siberia, seems to have been used and adapted in the mountain environment of the central Caucasus, where it was utilised by Karachays until the nineteenth century. In addition, the rectangular house form, similar to local building traditions, has been adopted. However, some features of the internal spatial organisation and customs can be linked to the traditional dwellings of Turkic nomadic groups. In the Caucasus, the use of earth and turf as roof covering material was known only in Karachay and in Balkaria, although it was widespread elsewhere. Due to the absence of surviving buildings from the period before 1800, it is not possible to study the material evidence of the medieval and post-medieval rural housing of the region to further explore the origins of Karachay’s vernacular architecture. This is the task for future archaeological research.

Table 1. Karachay: list of dendrochronologically dated buildings (see Supplementary Data).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (109 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to my colleagues from the Karachay-Cherkessk State University for their cooperation and support of our research expeditions, as well as to the many residents of the mountain villages whom we interviewed. In addition to the Department of Archaeology, members of other departments of the Faculty of Arts at the University of West Bohemia were involved in research activities in Karachay-Cherkessia, especially the Department of Middle Eastern Studies and the Department of Political Sciences and International Relations. My special thanks go to staff members Aneta Gołębowska-Tobias, Petr Charvát, Petr Netolický, David Šanc, Václav Trejbal and Zdeňka Vařeková, and archaeology students Roman Brejcha, Mikhail Burobin, Josef Chaibulin-Koštial, Lukáš Holata and Jindřich Plzák. I am also grateful to both anonymous reviewers of the paper for their comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03055477.2023.2271537.

Notes

1 This work was supported by the Funding Agency of the University of West Bohemia under Grant number SGS-2018-053.

2 218,000 people according the 2010 census (Minority Rights Group International, Karachay and Cherkess; Reports on the Results of the 2010 All-Russian Population Census).

3 The language is close to that of the Kipchak, a nomadic group that appeared in the eastern European steppes in the eleventh century. Khatuev, “Etnicheskaia istoria,” 40–1; Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 243.

4 Khatuev, “Politicheskaya istoria,” 41–51, 56–61.

5 Galonifontibus, Svedenia o narodach Kavkaza, 9–10.

6 Begeulov, Historický vývoj Karačaje, 83–159; Khatuev, “Politicheskaya istoria,” 61–7.

7 Begeulov, Historický vývoj Karačaje, 192–215.

8 Begeulov, Historical Overview of Karachay; Khatuev, “Politicheskaya istoria,” 80–8.

9 Begeulov, Historický vývoj Karačaje,.

10 For the deportation of Karachays (sürgün), see Aliev, Karachayevcy. Vyselenie i vozvrashchenie; Chomayev, Nakazannyi narod; Koichuev, “50 let deportatsii.”

11 The mountain settlement is called el’ or dzhurt in the Karachay language, and aul in Russian.

12 Aliev, Karachaevcy: Istoriko-etnologicheskiy, 16–18; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 62–3. Kart-Dzhurt is perceived as the earliest settlement among the Karachays (kart-yurt = old-settlement; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 63; interview in 2013).

13 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 67.

14 Dating of the defence towers is uncertain, similarly their builders and historic tenure; e.g. Miziev, Srednevekovye bashni, 46–7, 49–53. An archaeological surface survey of the Khurzuk tower (Mamiya Kala) in 2016 produced finds of high to late medieval pottery, which indicate the very early settlement of this site; Hložek and Vařeka, “Mamiya Kala.”

15 Shamanov, “Ekonomicheskaya istoria,” 130; Shamanov, “Skotovodstvo,” 71–81; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 71.

16 Kaloev, Zemledelie narodov severnogo Kavkaza, 60, 66; Shamanov, “Ekonomicheskaya istoria,” 91–8, 100–9; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 7–14, 39–50, 222–3.

17 The first kolkhoz in Karachay was established in 1928; Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 246–7.

18 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 158.

19 Bernshtein, Arkhitektura balkarskogo narodnogo zhilishcha.

20 Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy”; Shamanov, “Ekonomicheskaya istoria,” 129–35; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 147–239.

21 Only a small number of cows were kept on the farm for milk. Most of the cattle were left to graze on summer or winter pasturelands and not stabled in the farm; interviews in 2013 and July 2014.

22 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 161–6.

23 Kobychev, “Tipy zhilishcha,” 159–60; Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 251–4; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 159–60.

24 Shamanov, “Skotovodstvo,” 84–91; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 223–4.

25 Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 254–5.

26 Details are provided in the online Appendix to this article.

27 Interviews in 2013 and 2014.

28 Interview in 2014.

29 Terminology and symbolism; interviews in 2013, 2014, 2016 and Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 173–226.

30 A high concentration of charcoal was detected in the earthen roof cover of several houses, which would have served to reduce the load.

31 Only one documented case showed the placement of the heating equipment to the right of the entrance (K-F3-1).

32 Interviews in 2013 and 2014; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 178.

33 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 179–85, 225–31; interviews in 2013 and 2014.

34 Interviews in 2014 and 2016.

35 Kobychev, Tipy zhilishcha, 157–63; Kobychev, Poselenia i zhilishche, 83.

36 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 150, 158, 164, 166.

37 Especially in the Chegem valley; Bernshtein, Arkhitektura balkarskogo narodnogo zhilishcha, 87–9. Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 188. Generally, the gable roof is characteristic of vernacular architecture in the western Caucasus with more intense precipitation, whereas flat roofs are used in the eastern Caucasus.

38 Kobychev, Poselenia i zhilishche, 102, fig. 30; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 162.

39 Bernshtein, Arkhitektura balkarskogo narodnogo zhilishcha, 28, fig. 110.

40 Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 159–60.

41 Studenckaia, “Kabardinci i Cherkesy,” 161–2.

42 Lavrov, “Abaziny,” 239.

43 Autlev and Zevakin, “Adygeicy,” 205–6.

44 E.g. Kaloev, “Chechency,” 258–9; Kaloev, “Ingushi,” 378; Takoeva, “Osetiny,” 317.

45 Bernshtein, Arkhitektura balkarskogo narodnogo zhilishcha, 19; Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 251; Tekeev, Karachaevcy i Balkarcy, 163.

46 Studeneckaia and Sergeeva, “Karachaevtsy,” 251. A unique undated photograph of a multi-sided house in Khurzuk was kept in the State Ethnography Museum in Leningrad. Ibid., 252, .

47 Kharuzin, Istoria razvitia zhilishcha, 56–61; Lvova et al., Tradicionnoe mirovozrenie, 57.

48 Spatial organisation and symbolics of the southern Siberian Turkic yurt. See Lvova et al., Tradicionnoe mirovozrenie, 61–6.

49 E.g. Kuzheleva, “Nogaicy,” 393–5, 398–401.

50 E.g. in the Alps—Bedal, “Spätmittelalterlicher bäuerlicher Hausbau,” 248–9; Descœudres, Herrenhäuser; Furrer, “Living in a Wooden Box”; Kirchner and Kirchner, “Ein spätmittelaterliches Bauernhaus”; Kühtreiber, “Bauen, Umbauen”; or in Bohemia—Vařeka, “The Formation.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aliev, U. A. Karachaevcy: Istoriko-etnologicheskiy I kulturno-ekonomicheskiy ocherk. Rostov-na-Donu: Krainatzizdat-Sevkavkniga, 1927.

- Aliev, I. I., ed. Karachayevcy. Vyselenie i vozvrashchenie. Cherkessk: PUL, 1993.

- Autlev, M. G. and E. S. Zevakin. “Adygeicy.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 200–31. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Bedal, K. “Spätmittelalterlicher bäuerlicher Hausbau in Süddeutschland. Versuch eines Überblicks—Bestand, Formen und Befunde.” In Ruralia 4, Památky archeologické—Supplementum 15, edited by J. Klápště, 240–56. Prague: Institute of Archaeology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 2002.

- Begeulov, R. “Historický vývoj Karačaje.” In Karačaj. Archeologie, historie a etnologie, edited by P. Vařeka. Plzeň: Vydavatelství Západočeské University (University of West Bohemia Press), in preparation.

- Bernshtein, E. B. Arkhitektura balkarskogo narodnogo zhilishcha. Moskva: Diksi, 1993.

- Chomayev, K. I. Nakazannyi narod. Cherkessk: PUL, 1993.

- Descœudres, G. Herrenhäuser aus Holz. Eine mittelalterliche Wohnbaugruppe in der Innerschweiz. Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters 34. Basel: Schweizerischer Burgenverein, 2007.

- Furrer, B. “Living in a Wooden Box: Late Medieval Log Houses in Central Switzerland and Northern Tessin.” In Ruralia 4, Památky archeologické—Supplementum 15, edited by J. Klápště, 143–50. Prague: Institute of Archaeology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 2002.

- Galonifontibus de, J. Svedenia o narodach Kavkaza (1404 g.). Baku: Elm, 1980 (Russian translation).

- Hložek, J. and P. Vařeka. “Mamiya Kala. Obranná věž v Churzuku.” In Karačaj. Archeologie, historie a etnologie, edited by P. Vařeka. Plzeň: Vydavatelství Západočeské University (University of West Bohemia Press), in preparation.

- Kaloev, B. A. “Chechency.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 345–74. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Kaloev, B. A. “Ingushi.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 375–90. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Kaloev, V. A. Zemledelie narodov severnogo Kavkaza. Moskva: Nauka, 1981.

- Kharuzin, N. Istoria razvitia zhilishcha u kocjevych i polukochevych tiurskikh i mongolkikh narodnostei Rosii. Moskva: Levenson, 1896.

- Khatuev, R. T. “Etnicheskaia istoria i etnogenez.” In Karachay s drevneishikh vremen do 1917 goda, edited by K. T. Laipanov, R. T. Khatuev and I. M. Shamanov, 8–42. Cherkessk: NKO Alanskii Ermitazh, 2009.

- Khatuev, R. T. “Politicheskaya istoria.” In Karachay s drevneishikh vremen do 1917 goda, edited by K. T. Laipanov, R. T. Khatuev and I. M. Shamanov, 43–88. Cherkessk: NKO Alanskii Ermitazh, 2009.

- Kirchner, W. and W. Kirchner. “Ein spätmittelalterliches Bauernhaus in Gröden, Süd Tirrol.” In Haus und Kultur im Spätmittelalter, Quellen und Materialen zur Hausforschung in Bayern 10, edited by K. Bedal, S. Fechter and H. Heidrich, 213–21. Bad Windsheim, 1998.

- Kobychev, V. P. “Tipy zhilishcha u narodov severo-zapadnogo Kavkaza v seredine XIX v.” Kavkazkii etnograficekii sbornik 5 (1972): 150–67.

- Kobychev, V. P. Poselenia i zhilishche narodov severnogo Kavkaza v XIX i XX vv. Moskva: Nauka, 1982.

- Koichuev, A. D. “50 let deportatsii karachaevskogo Naroda.” In Repressirovannye narody: istoria i sovremennost, edited by A. Kh. Tarashao, A. D. Koichuev and I. M. Shamanov, 8–43. Karachaevsk: Karachaevo-cherkesskii gosudarstvenyi pedagogicheskii universitet, 1994.

- Kühtreiber, T. “Bauen, Umbauen, Wohnen und Arbeiten.” In Die Rainerkeusche: Ein mittelalterliches Kleinbaurnhaus aus dem Lungau, edited by M. Brunner-Gaurek and H. Waitzbauer, 45–89. Großgmain: Veröffentlichungen des Salzburger Freilichtmuseums, 2018.

- Kuzheleva, L. N. “Nogaicy.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 391–402. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Lavrov, L. I. “Abaziny.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 232–42. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Lvova, E. L., I. V. Oktyabrskaya, A. M. Sagalaev and M. S. Usmanova. Tradicionnoe mirovozrenie tiurkov juzhnoi Sibiri. Prostranstvo i vremia. Veshchnyi mir. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1988.

- Minority Rights Group International. Karachay and Cherkess. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://minorityrights.org/minorities/karachay-and-cherkess/

- Miziev, I. M. Srednevekovye bashni i sklepy Balkarii i Karachay. Nalchik: Elbrus, 1970.

- Reports on the Results of the 2010 All-Russian Population Census. Accessed January 15, 2021. http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612.htm

- Shamanov, I. M. “Skotovodstvo i khoziaistvennyi byt karachaevcev v XIX–nachale XX v.” Kavkazkii etnograficheskii sbornik 5 (1972): 67–97.

- Shamanov, I. M. “Ekonomicheskaya istoria.” In Karachay s drevneishikh vremen do 1917 goda, edited by K. T. Laipanov, R. T. Khatuev and I. M. Shamanov, 89–148. Cherkessk: NKO Alanskii Ermitazh, 2009.

- Studeneckaia, E. N. “Kabardinci i Cherkesy.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 138–99. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Studeneckaia, E. N. “Karachaevtsy.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 243–69. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Takoeva, N. F. “Osetiny.” In Narody Kavkaza I, edited by M. O. Kosven, L. I. Lavrov, G. A. Nersesov and Kh. O. Khashaev, 297–344. Moskva: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Tekeev, K. M. Karachaevcy i Balkarcy. Tradicionnaia Sistema zhizneobespechenia. Moskva: Nauka, 1989.

- Vařeka, P. “The Formation of the Three-Compartment Rural House in Medieval Central Europe as a Cultural Synthesis of Different Building Traditions”. In Buildings of Medieval Europe. Studies in Landscape and Social Contexts of Medieval Buildings, edited by D. Berryman and S. Kerr, 139–55. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow, 2018.