ABSTRACT

This study investigates how purpose manifests itself among purposeful Finnish student teachers (N = 12) using Schwartz’s framework of personal values and Westheimer and Kahne’s model of citizenship to further the understanding of what purposeful student teachers’ sources of purpose are, how they contribute to the world beyond the self, and what actions they take to realize these contributions. Purpose is defined as personally meaningful long-term engagement to a goal with consequences for the world beyond the self. The interviews showed that although teachers’ work was deemed important, purpose contents associated with the value of benevolence, such as family and friends, were student teachers’ main content of purpose and their beyond-the-self motivations mostly manifested as actions intended to contribute within the familial circle. To increase student teachers’ future willingness to act on participatory and justice-oriented levels, more effort needs to be invested in the development of purpose and civic engagement-oriented higher education.

Introduction

In this age of existential threats and increasing inequality, individuals willing and able to contribute at the communal and societal level are needed. Such individuals hold self-transcendent values in high regard, inspire participation, and alter institutional structures when necessary (Schwartz, Citation2012; Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). Teachers are well positioned to meet this need and can assume a leading role in promoting self-transcendent values and citizenship throughout society.

In recent decades, the prevalence of neoliberal ideals in Finnish universities has increased (Kallo, Citation2009, Citation2021; Poutanen et al., Citation2022) and self-enhancing values have become more common among the young in the West (Marcus et al., Citation2022; Urukovičová, Citation2022) while their interest in civic participation has dwindled (Loader et al., Citation2014; Melo & Stockemer, Citation2014; Sloam, Citation2014). In addition, the public image of teaching in Finland has suffered and work dissatisfaction among Finnish teachers has increased (Punakallio & Dervin, Citation2015; Finnish Government, Citation2020 respectively). Paradoxically, globalization and the international rise of neoliberalism have simultaneously expanded the concept of citizenship to encompass moral and cultural aspects (Veugelers, Citation2021). As a result, teachers are increasingly tasked with promoting competencies (e.g., critical thinking, interaction and leadership skills) and are expected to promote values like equality, inclusion, and social justice among their pupils to support moral development, increase agency, and promote harmonious co-existence within and between nations (Joris et al., Citation2022; Westheimer, Citation2022).

These developments also raise concerns. Can Finnish teacher education prepare future teachers to become active citizens capable of serving their country and humanity, one of the ultimate goals of Finnish university education (UNIFI, Citation2020; Universities Act, Citation2009)? Are they equipped with the skills and knowledge needed to advance active citizenship to increase sociocultural cohesion, civic participation, and the moral development of their pupils emphasized by the Finnish state and European Union (Joris et al., Citation2022; Rautiainen et al., Citation2020)?

Finnish teachers are viewed as ethical professionals supporting their pupils’ holistic development, as critical thinkers equipped with reflection skills and high autonomy (Tirri, Citation2018). However, education for democratic citizenship is not an explicit goal of Finnish teacher education (Rautiainen et al., Citation2020). The focus has been on developing student teachers’ competencies from psychological and pedagogical perspectives to provide them with skills and knowledge to function in the classroom. Hence, the means for promoting it remain under-defined in policies and regulations guiding Finnish teacher education and there persists a lack of understanding about concrete methods for promoting student teachers’ ability to adopt and foster citizenship (Joris et al., Citation2022; Rautiainen et al., Citation2020). Consequently, democracy and human rights issues are secondary in routine operations in teacher education (Rautiainen et al., Citation2020) and of scant interest to student teachers (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a; Citation2023b). As a result, Finnish teacher education continues to educate teachers who focus mainly on their students’ socialization to the existing societal, cultural, and value structures, not on developing competencies or the will needed for their critical examination and alteration (Rautiainen et al., Citation2020).

It has been suggested that discovering and adopting a purpose in life may support future teachers in practising and fostering self-transcendent values and citizenship (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Tirri, Citation2018). Damon et al. (Citation2003) have defined purpose as an active commitment to goals that are meaningful to oneself and produce significant consequences beyond the self. Purpose supports well-being (Bronk et al., Citation2009; Chen & Cheng, Citation2020; Heng et al., Citation2017; Van der Walt, Citation2019), enables questioning of prevailing norms and structures (Damon & Colby, Citation2015), enhances commitment to long-term action (Hill et al., Citation2014; Lund et al., Citation2019; Sharma & Yukhymenko-Lescroart, Citation2018; Yeager et al., Citation2014), and supports acting in challenging situations (Frankl, Citation2020).

There has long been a focus in Finnish teacher education on educating teachers capable of goal setting, networking, and of critically reflecting on their own values, motives, and actions (Lavonen, Citation2018; Tirri, Citation2018). Yet supporting student teachers in adopting a purpose in life is not a priority in Finnish teacher education. Hence, discovering such purpose is relatively rare among Finnish student teachers (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a; Citation2023b).

How will citizenship be realized by future teachers, who play a key role in preparing the up-and-coming generations to serve the needs of their country and humanity? To shed light on this, the present study explores how purpose manifests itself among purposeful Finnish student teachers by utilizing Schwartz’s (Citation2012) framework of personal values and Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) model of citizenship. We also hope to stimulate discussion on adopting purposefulness as a goal of moral education in higher education to increase student teachers’ democratic citizenship and to support them in embracing a purpose in life.

What is meant by purpose in life?

After the Second World War, Victor Frankl started to emphasise purpose and meaning as unique promoters of well-being and resilience. Frankl (Citation2020) pointed out that lack of purpose in life can lead to a state of existential threat characterized by feelings of emptiness, alienation, and aimlessness. It is through active engagement with the world, within the confines one’s unique life circumstances, that real self-actualization leading to lasting contentment can be achieved (Frankl, Citation2020).

Since the decades following Frankl’s notions, the concept of purpose has been expanded and developed by others (e.g., Crumbaugh & Maholick, Citation1964; Ryff & Singer, Citation2008). In 2003, Damon et al. conceptualized the most comprehensive definition of purpose to date as ‘a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something that is at once meaningful to the self and of consequence to the world beyond the self’ (p. 121). According to this definition, purpose consists of three dimensions: 1) personally meaningful intention, 2) a realization of beyond-the-self motivation, 3) long-term engagement in action (Bronk, Citation2014).

Personally meaningful intention (i.e., source of purpose) provides motivation and encourages commitment to the pursuit of self-transcendent purpose. Beyond-the-self motivation reflects interest in contributing towards others, nature, and society. Long-term engagement refers to consistent actions to achieve one’s purpose. These are prerequisites for systematic progression towards a purpose that can be seen as a relatively stable and far-reaching base for one’s life (Bronk, Citation2014; Damon et al., Citation2003).

In purpose studies, five profiles (1) purposeful, (2) dreamers, (3) dabblers, (4) self-oriented, and (5) disengaged are often used to describe different levels of purposefulness (Damon, Citation2008; Moran, Citation2009). Purposeful individuals have found and actively pursue a self-transcendent purpose that includes all three dimensions of Damon et al.’s (Citation2003) definition. Dreamers may hold self-transcendent values and express an interest in making contributions beyond the self, but they are not committed to or actively striving towards this (Damon, Citation2008). Dabblers may be engaged in meaningful and self-transcendent activities but lack sustained and long-term commitment and intention. Self-oriented individuals are actively engaged and committed to the pursuit of self-serving goals (Moran, Citation2009). In the lives of the disengaged none of the dimensions of purpose are present (Moran, Citation2009).

Being purposeful is relatively rare. North American studies have found that only about 20–30% of the young are committed to a purpose in life (Bronk, Citation2014; Damon, Citation2008; Moran, Citation2009). However, a considerable proportion (55% according to Damon, Citation2008) display signs that at least one of the three dimensions of purpose is present in their lives. Only few studies have investigated the nature and prevalence of purpose in the context of Finnish higher education. Tirri and Kuusisto (Citation2016) found that 24% of student teachers had found their purpose in life and were firmly committed to its realization. In another study, Kuusisto and Tirri (Citation2021) found that 43% of student teachers were pursuing a self-transcending purpose while 46% were working towards self-oriented life goals like happiness, relationships, and self-actualization.

While comparing students studying in Finnish and Dutch universities Kuusisto et al., (Citation2023a) found 33% of Finnish and 45% of Dutch humanities, social, and educational sciences students to be purposeful. However, from the open-ended responses of the Finnish students, a strong self-orientation emerged even among those profiled as purposeful (Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a).

Students found to be purposeful by Kuusisto et al. (Citation2023a) are the object of inquiry in the present study. Due to the inconsistent picture painted by this group’s survey and open-ended question responses it is important to examine by means of qualitative interviews exactly how these purposeful student teachers understand their own purpose. Also, purposeful individuals have not been the focal point of any studies previously conducted in Finland and most Finnish purpose studies have been quantitative in nature. Hence, focusing solely on purposeful students from a qualitative perspective may produce novel information about the manifestations of purpose among Finnish student teachers.

Schwartz’s model of personal values

Kuusisto et al. (Citation2023c) found that analysing students’ personal values using Schwartz’s model (Schwartz, Citation2012) in tandem with their sources of purpose provides a framework that can support the organization of various purpose content. Values related to life purposes (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c) can be defined as durable long-term beliefs that guide thinking, choices, and actions (Sagiv & Schwartz, Citation2022).

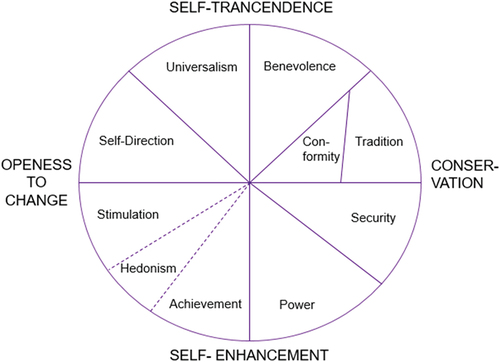

Schwartz’s (Citation2012) model organizes universally prominent personal values based on their content and motive using a circular structure. It consists of ten content areas: universalism (appreciation for the whole of humanity and the natural world), benevolence (concern for the members of one’s in-group), tradition (reverence for customs of one’s culture or religion), conformism (upholding social expectations and norms), security (safety, health), power (social status, dominion over human/nonhuman capital), achievement (individual success), hedonism (gratification through pleasure, joy, etc.), stimulation (newness and challengingness), and self-direction (agency manifested as exploration, novel thinking, etc.). Schwartz’s model and the ten content categories are presented in .

Values with different underlying motivations are placed opposite each other in the circle to highlight two underlying dimensions. The first dimension reflects whether values are oriented towards contributing to others’ (self-transcendence; universalism, and benevolence) or improving one’s own position and self-gratification (self-enhancement; power, achievement, and hedonism) (Schwartz, Citation2012). This dimension captures the dynamics present in Damon’s conceptualization of purpose and lays the foundation for the categorization of different purpose sources (Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c). The second dimension highlights whether there is an interest in expansion (openness to change; self-directedness, stimulation) or towards self-protection (conservation; security, conformity, and tradition) (Schwartz, Citation2012).

Rankings of human values have been found to be similar across the globe (Sagiv & Schwartz, Citation2022). Values of universalism, benevolence, and self-direction are praised cross-culturally, the importance of conservation, conformity, and tradition varies between countries, and power is universally valued least (Sagiv & Schwartz, Citation2022). However, there are significant variations in value priorities between individuals and groups (Fischer & Schwartz, Citation2011). Universalism is reportedly a more prominent value and content of life purpose among students of humanities and social sciences, while business and technology students are more prone to espouse values and sources of purpose related to self-enhancement (Arieli et al., Citation2020; Kuusisto & Schutte, Citation2022; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c).

Westheimer and Kahne’s model of citizenship

Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) model is utilized in this study to categorize manifestations of Finnish student teachers’ beyond-the-self motivations. Their conceptualization of citizenship includes a moral and socio-political focus that manifests itself through contributions made by individuals to society on personal and intrapersonal levels (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). This orientation to contributing beyond the self is highly reminiscent of the conception of Damon et al. (Citation2003) of self-transcendent purpose.

According to the model, personally responsible citizens make choices in their own lives based on virtuous character traits that promote the common good and make them responsible actors in their community. Such a person might donate money to advance a worthy cause or promote ecological sustainability by being a vegan (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004).

Participatory citizens are active members of their community (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). They strive to promote the well-being of others by taking initiatives and organizing resources to tackle societal challenges like social and economic inequality. They understand how established systems and structures work and have strategies for tackling collective problems by working within them.

Justice-oriented citizens are critical assessors of social, political, and economic structures on local, national, and global levels (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). They are interested in the root causes of pervasive problems and strive to tackle these by establishing better societal structures and institutions. Critical thinking and the will to question things are key characteristics of a justice-oriented citizen (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004).

It seems plausible that having a purpose in life could fuel future teachers’ desire to practise the forms of citizenship proposed by Westheimer and Kahne. Purposeful individuals tend to dedicate their lives to the pursuit of human rights, equality, and justice through politics, religion, activism, etc. (Damon & Colby, Citation2015; Kuusisto & Schutte, Citation2022) and are committed, determined, and adaptable (Damon & Colby, Citation2015). These are mediums and characteristics that personally responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented citizens also use to enact change (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004).

Research questions

This qualitative study investigates how purpose manifests itself among purposeful Finnish student teachers to initiate discussion about developing teacher education to promote purposefulness and active citizenship among future teachers. This study aims to answer the research question ‘How do the three dimensions of purpose manifest themselves in the lives of purposeful Finnish student teachers?’

- What are the contents of their purpose?

- What are their beyond-the-self motivations?

- What are they doing to achieve these purposes?

Data and methods

Interview protocol

A modified version of the interview protocol developed by Malin et al. (Citation2014, Damon, Citation2008), which takes into consideration the three dimensions of purpose was used. The protocol was translated into Finnish and tested by conducting pilot interviews (n = 5). The interviewees were bachelor’s and master’s students at Tampere University. According to the interviews, the protocol was capable of eliciting manifestations of purpose.

The principles of responsible conduct of research (RCR) were respected and followed throughout the data collection and storage process (TENK, Citation2022). Most interviews were conducted face to face but due to the prevailing circumstances a few were carried out remotely using Zoom or Teams. Regardless of the form of implementation, each interview followed the same format.

At the beginning, the interviewees were offered the opportunity to freely ask questions about data collection and processing. Next, interviewees gave their written consent. During each interview the themes of the modified protocol were presented to the participants in the same order to improve the internal consistency of the study and to facilitate comparison, classification, and compilation of the data during the analysis. Interviews were recorded using two devices (computer and smartphone) and the original recordings were destroyed immediately after the production of anonymized copies. These and the text-based transcripts produced were stored in the data-protected electronic systems at Tampere University for the duration of the study. Data are now stored at the Finnish Social Science Data Archive.

Participants

In total seventy people who had been identified as purposeful (Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a) and who had given their contact information for future interviews were approached by e-mail. Fifteen people agreed to be interviewed. Two subjects were rejected because they were not studying educational sciences. One subject was also rejected because of the sensitive information provided during the interview which compromised the subject’s privacy and the integrity of our analysis.

The final group of subjects consisted of twelve interviewees: four classroom student teachers, six early childhood education student teachers, and two adult educator students from a lifelong learning programme. Seven were studying for a master’s, four for a bachelor’s, and one for a doctoral degree. The age of the interviewees ranged between 22 and 43, the mean age being 27 years. Nine of the interviewees were women and three were men. The names of the student teachers presented in the following sections are pseudonyms to ensure their anonymity.

Analyses

An abductive approach (Graneheim et al., Citation2017) was used to analyse the content of participants’ life purposes. After initial familiarization, the first author read through and coded the entire data set in Excel. The units of analysis were single-word or multi-word sentences containing a single manifest or latent meaning (Graneheim et al., Citation2017). All units indicating the personal significance of a thing, activity, or a person were coded and are referred to from here on as purpose content. They are targets of the subject’s intention, act as a motivational force driving active engagement (actions), and may contain an orientation towards oneself or others (beyond-the-self motivation) (Bronk, Citation2014)

Schwartz’s model (Citation2012) was used to categorize the purpose content identified under four dimensions (self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, conservation) to assess their content in relation to their underlying values (Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c).

To determine whether purpose content was aimed at benefitting oneself or others, further examination was undertaken with reference to Kuusisto and Tirri’s (Citation2021) earlier study. The beneficiaries of aspirations were introduced as the second unit of analysis. If the interviewee explicitly mentioned beneficiaries directly affected by their purpose content, this was taken to indicate that other orientation (beyond-the-self dimension) was included. If no beneficiaries were explicitly mentioned, self-focus was assumed.

Illustrations of these analytical processes are presented below using representative data excerpts. The content categories, Schwartz’s value categories, and self or other orientations are presented in square brackets:

- love for oneself and appreciation for oneself as a person. It’s number one [content: love for oneself; value: self-direction; orientation: self]. Second, I would say my support network, by which I mean my closest friends and family [content: family, friends; value: self-transcendence; orientation: self]. Thirdly, I say freedom, because it enables me to do with my future what I want, where I want. [content: freedom; value: self-direction; orientation: self]. (Sarah, 22 years, classroom student teacher)

Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) three forms of citizenship were utilized to capture interviewees’ beyond-the-self motivations based on their level of manifestation. Contributions enacted in personal life (e.g., raising one’s own children, recycling) which had little or no impact beyond the immediate field of influence were deemed Personally responsible. Contributions conducted at community or societal levels through existing structures and systems aimed at tackling societal challenges (e.g., reducing inequality) were labelled as Participatory. If an interviewee described engaging in action(s) to alter existing structures/systems and aimed to bring about fundamental societal changes their contributions were coded as Justice-oriented.

During the analysis, Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) model of citizenship proved ineffective in capturing all the meanings expressed by the student teachers related to their beyond-the-self motivations. Hence, the model was expanded by forming a subcategory called beyond-the-self dreams [BTS dreams] to capture meanings manifested by student teachers of contributing to the world that lacked commitment and active engagement. The category was formed abductively based on previous purpose studies (Damon, Citation2008; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a) and work by Moran (Citation2009), who identified Dreamers as one of the top purpose profiles.

Actions of engagement were analysed by establishing nine categories that captured different forms of action based on their context and form. For instance, if an action took place in a school setting and was aimed at educating a student, it was deemed to be an educational action or if an interviewee described engaging in conversation with friends to discuss environmental matters, they were taken to be engaged in social action.

Illustrations of the analytical processes used to identify beyond-the-self contributions and actions of engagement made by the interviewees are presented below. Categories and codes are presented in square brackets:

- during teaching internships, there have been moments when I’ve stopped to think [category: actions of thought; code: reflect] and realized that this is why I’m studying to become a teacher - - They have usually been moments when a student has had a difficult day and I have somehow managed to help him forward [category: educational actions; code: educate] - - that’s why I’m doing this - - It’s not just about the salary [category: participatory; code: working as a teacher]. (Richard, 24 years, classroom student teacher)

The analysis process was captured by the construction of a codebook to increase the transparency and replicability of the coding process and to conduct internally consistent and reflective analysis (MacPhail et al., Citation2016). The code book contained 64 codes accompanied by a description of their meaning and instructions for and examples of their use.

To study interrater reliability, segments of data (10% of the data analysed) were coded separately by both authors referring to the codebook. The results of this round of coding were discussed by the authors and modifications to the codebook were made. Finally, another 10% of the data was coded separately by the authors, kappa values for each category were calculated and they indicated a satisfactory level of agreement, i.e., above .06 (MacPhail et al., Citation2016).

Results

Contents of purpose

Forty-five different units of purpose content were identified and categorized under the four dimensions using Schwarz’s values framework. Contents were also grouped according to their orientation. The results of the analysis are shown in .

Table 1. Content of life purposes, beyond-the-self contributions and BTS dreams, and actions of engagement.

Content associated with the value of benevolence (N = 12; f1 = 309, %f1 = 20), like family and friends was the most important content of purpose for the student teachers (), as the following quote from Jane demonstrates:

- Family always comes first. (Jane 27 years, adult educator student)

Their second most significant source of purpose was content associated with the values of achievement (N = 12; f1 = 152, %f1 = 10) which in the case of student teachers meant working as teachers at different levels of the education system and studying to become experts in the field ().

- my best opportunities to make a difference come about through teachers’ work by influencing future generations. I want to study more about societally relevant issues, how to teach about them, and carry them forward. (Anna, 23 years, classroom student teacher)

Ten interviewees mentioned at least one item of purpose content associated with the value of stimulation (N = 10; f1 = 89, %f1 = 6) referring to things like singing or playing a musical instrument. Student teachers’ self-directional purpose contents (N = 8; f1 = 65, %f1 = 4) typically included continued development and personal freedom that gave them a sense of purpose in life ().

- Freedom is an important value for me - - becoming independent and not being dependent on anyone. (Sarah, 22 years, classroom student teacher)

Student teachers’ universalistic content of purpose (N = 12; f1 = 75, %f1 = 5) were aspirations to make a difference in the world, for instance by tackling societal issues (). Such content acted as a motivational and driving force that inspired students to become and act as teachers and to make contributions beyond themselves at work.

- I would like everyone to have equal opportunities from the start - - I always promote equality when working. (Anna, 23 years, classroom student teacher)

- I have kept thinking about my- - purpose in life [caring and protecting others] - - it strongly relates to the fact that the teacher does well in his work. Strives to ensure that children - - feel well, do good for others, have skills for working life, and find their community. (Perri, 29 years, classroom student teacher)

No purpose content associated with power and conformity was identified, and content associated with tradition rarely occurred in the data (N = 2; f1 = 16, %f1 = 1) (). This result is in line with the findings of earlier Finnish purpose studies (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c).

Most purpose content included an orientation towards both the self and others () indicating that a beyond-the-self dimension could be associated by the participants with different sources of purpose. This supports Kuusisto and Tirri’s (Citation2021) previous notion that, in principle, any purpose content may include both orientations.

The beyond-the-self dimension of purpose

Actual manifestations of a beyond-the-self dimension as contributions made by student teachers are shown in using Westheimer and Kahne’s three forms of citizenship. Personally responsible contributions were mentioned most (f1 = 62, %f1 = 4) (). Interviewees described putting the needs of others before their own, efforts to bring up their children to become responsible and open-minded citizens, and attempts to promote pro-societal and pro-life values in their personal lives.

- I often think about their [family/relatives’] perspectives. For example, I have old grandparents, and - - they live in Vantaa. So, you must always think from many angles when and if to go there - - you must be as considerate as you can. Not to be selfish. (Anna, 23 years, classroom student teacher)

- I try to raise my children so that they - - realize that there are different people in the world and that all are equal. - - to understand from an early age that no one may be bullied. (Jane, 27 years, adult educator student)

- I’m a vegetarian and that influences things - - also finding out about these things and then talking about them with my friends - - I’m an active citizen and member of society, - - doing something for - - the world. (Sarah, 22 years, classroom student teacher)

The student teachers usually made these contributions within the context of their ingroups but carried out participatory contributions only at work. They saw teachers’ work as valuable and emphasized that as teachers they could develop students’ emotional and conflict-resolving skills and influence their attitudes and values. Interviewees also felt they could promote students’ wellbeing, as the following statements by Sully and Perri show:

- I work in early childhood education, so I teach children emotional skills - - we go through how to negotiate things, how to wait for one’s turn, and how to express one’s own anger and frustration. (Sully, 35 years, early childhood education student teacher)

- As a teacher - - my work is very closely connected to society, I do grassroots work, to influence the values and attitudes of future adults, - - diversity of viewpoints, cultures, ethnicities - - in those matters, I can make a difference. (Perri, 29 years, classroom student teacher)

In addition to making participatory contributions in daily working life, some student teachers reported that they had started studying to become teachers to educate future generations to promote a societal change towards pro-life values, equality, and increased security. This continued to encourage interviewees like Perri to work towards their goals and to keep making justice-oriented contributions.

- My field of influence is in the school, where I strive, incompletely, imperfectly, and slowly, but to the best of my ability, - - to plant some cultural and societal seeds so that something good will emerge for the generations to come. (Perri, 29 years, classroom student teacher)

Outside teachers’ work, however, few justice-oriented contributions were actively pursued. Julia wanted to promote the rights of autistic children and give them a voice by writing her master’s thesis on the subject. Rachel was working towards becoming an academic so that she could improve the quality of early childhood education. Jane worked in a large social organization to foster a just transition towards sustainable development.

- I noticed when reading studies - -, how easily autistic children get walked over on many occasions. Then it occurred to me that it would be great if I could do something with my thesis to improve the situation. - - Help bridge that gap. (Julia, 22 years, early childhood education student teacher)

- I want to improve quality early childhood education for any children and any family. The way to improve this quality to me is communities. More people should start to work for each other and think about others - - that’s my main goal for this journey. (Rachel, 28 years, early childhood education student teacher)

- I try to promote a just transition to sustainable development - - After ending up on the climate and sustainable development side - - and connecting with those values I try and can push them forward effectively at work. (Jane, 27 years, adult educator student)

Participants also described multiple meanings related to beyond-the-self motivations that did not fall under the three subcategories embodying Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) idea of citizenship. These were dreams to contribute to the world in a positive way, which the interviewees described, but did not actively pursue. These ‘dreams’ are more common than actual beyond-the-self contributions, even among non-purposeful individuals (Bronk, Citation2014; Damon, Citation2008).

The prevalence of beyond-the-self dreams [BTS dreams] is shown in . Most BTS dreams were general expressions about promoting the common good, improving societal justice etc. Dreams about world peace and non-violence were also mentioned, which, given the current world situation, is not surprising.

- [I want] the world to - - be good for people - - People would get help more easily - - all people would have the same desire to help and build good together. (Anastasia 23 years, early childhood education student teacher)

- [I hope for] world peace - - [this is] even more relevant in the current world situation. Now war is truly more present in Europe as well. (Richard, 24 years, classroom student teacher)

Some BTS dreams were more detailed in nature. For instance, Perri wanted to write books that would enable teachers to promote students’ development in life. She had clearly thought about this and seemed open to the possibility of pursuing this dream in the future. Yet she also felt her resources for this were limited.

- I would like to write educational literature and fairytales - - I want it to be material which is good for people, that even teachers could use to support the children’s - - development in life. - - but I don’t think I have enough capacity for anything like this. (Perri, 29 years, classroom student teacher)

Engagement with purpose

In addition to personally significant intentions and a beyond-the-self dimension, purposefulness is about action. The forms of action the interviewees carried out in pursuit of their life purpose(s) and their prevalence are shown in . Most actions described by the participants were actions of thought (f1 = 201, %f1 = 13) and social actions (f1 = 147, %f1 = 9) () aimed at making contributions to student teachers’ families and friends, which were their most important purpose content ().

- I think about many of the things that I do firstly from her [spouse’s] point of view. For instance, if a friend asks me to go somewhere with him, I - - ask her first if we had something to do on that day, - - and often in a shop I consider if I should buy something for her, too. (Richard, 24 years, classroom student teacher)

The previous quotation by Richard illustrates how interviewees planned actions with others in mind and tried to make decisions that served their own and the needs of those whom they loved. In addition, spending time, having conversations, and doing things for and with friends, spouse etc., were among the most frequently mentioned actions. Parent interviewees, Monica, Jane and Sully also described multiple thought, social, value, and educational actions aimed at supporting their children’s growth into responsible citizens.

- we had a discussion with my son just yesterday. He had a very black-and-white view on a certain issue, and I tried to shed some light on the fact that there are other types of views and that we should try and understand the motives and arguments of others. (Monica, 43 years, early childhood education student teacher)

The fact that most social and thought actions were directed towards benevolent sources of purpose shows just how important they were to the student teachers. However, these forms of action could also serve aspirations extending further into the world beyond. Actions of thought were seen as essential by the participants for making participatory and justice-oriented (forms of) contributions as teachers. They were felt to increase one’s ability to participate in the prevention of socially significant challenges, enable new skills acquisition, and to support goal setting.

- I have planned to apply to become a teacher next year. First, a classroom teacher, but then maybe like a special education teacher. - - to be a support person to students and - - help them learn things to move forward in life. - - I am striving in that direction bit by bit. (Robert, 23 years, adult educator student)

Interviewees described conducting different educational actions when working as teachers to support student development and wellbeing, and to pursue self-transcendent goals. Artistic actions (e.g., crafting, painting) and value actions, like exemplary behaviour, were also sometimes carried out in the educational context to promote student development and wellbeing. The following quotation from Julia is a fine example of her efforts to reduce violence through exemplary behaviour.

- quite often kindergarteners get that emotional avalanche and then the fists come into play easily. - - I teach and try to set an example that violence is never the solution and that things can always be resolved somehow better. (Julia, 22 years, early childhood education student teacher)

Discussion and conclusions

This study investigated how purpose manifests itself among purposeful Finnish student teachers to further our understanding of the content of their purposes, how these contribute to the world beyond the self, and what actions are used in their pursuit to shed light on how citizenship will be realized by future teachers. Its aim has also been to initiate discussion about adopting purposefulness as a goal of moral education in higher education to encourage teachers to adopt and promote active citizenship.

Purpose content associated with the value of benevolence (e.g., family, friends) constituted student teachers’ main purpose content. This is in line with findings showing self-transcendence related values to be globally most valued among students of humanities and social sciences (Arieli et al., Citation2020; Fischer & Schwartz, Citation2011; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c). The importance of friends, family etc. was also consistent with the results of earlier inquiries conducted among Finnish student teachers (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021).

Student teachers’ beyond-the-self motivations manifested mostly in their familial relations through thought and social actions aimed at making contributions within a familial circle, indicating the importance of being personally responsible (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). Student teachers made substantially fewer participatory and justice-oriented beyond-the-self contributions. These were only related to work. Students wanted to be good teachers, researchers, and specialists to promote the well-being of others, improve education systems, and to tackle societal issues. They described engaging in supporting students’ development and well-being through exemplary behaviour, teaching children emotional skills, and engaging in artistic endeavours with their pupils. Studying was felt to enable student teachers to pursue these beyond-the-self motivations by providing them with competencies to plan and make beyond-the-self contributions through thought, educational, artistic, and value actions.

In addition to actualized beyond-the-self motivations, beyond-the-self dreams were decidedly prevalent among the student teachers. To highlight these dreams, we expanded Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) model of citizenship to encapsulate meanings expressed by the student teachers of contributing to the world that lacked commitment and active engagement. These were general expressions about enhancing the state of the world but lacked decisiveness. The prevalence of these dreams is in line with the findings of earlier purpose studies (Damon, Citation2008; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023a; Moran, Citation2009).

Despite a growing shortage of qualified teachers (European Commission, Citation2019) teaching continues to be a well-respected, highly educated, and attractive profession in Finland (European Commission, Citation2019; Finnish Government, Citation2020; Lavonen, Citation2018). The purposeful student teachers who participated in this study did indeed see teachers’ work as meaningful and felt they could influence their communities and society through work. However, even though work and studying were perceived as important they were not the student teachers’ most important purpose content. Family values superseded everything else, and participatory and justice-oriented contributions were made to a much lesser extent than personally responsible ones.

This could partly be explained by the fact that students of educational sciences tend to be people-oriented and hold benevolent self-transcendent values but not universalistic ones in high regard (Arieli et al., Citation2020; Kuusisto & Schutte, Citation2022; Kuusisto et al., Citation2023c). Also, we do not know the extent to which international shifts in young people’s value-orientations (Marcus et al., Citation2022; Urukovičová, Citation2022) and interest in civic engagement (Loader et al., Citation2014; Melo & Stockemer, Citation2014; Sloam, Citation2014) may have affected the student teachers’ purposes in the present study. Recent negative teacher publicity featured in the Finnish media (Punakallio & Dervin, Citation2015) and reports about growing job dissatisfaction among teachers (Finnish Government, Citation2020) may also have affected the student teachers’ willingness to make community-oriented and societal contributions.

It is also unclear how the psychological and pedagogical orientations dominant in Finnish teacher education have affected student teachers. This is an under-researched area. Hence, little is known about the association between practices in Finnish teacher education and purpose development. Yet we do know that Finnish teacher education offers student teachers few opportunities to gain practical experiences of democracy and that the examination of philosophical, sociological, and cultural questions is secondary in the day-to-day operations of teacher education (Rautiainen et al., Citation2020).

Not all teachers need to be moral examples like Greta Thunberg or Nelson Mandela. Yet we need teachers who can work together and commit to long-term action in high-pressure and complex situations at different levels of the education system to best enable future generations to serve their country and humanity (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2021; Rautiainen et al., Citation2020; Tirri, Citation2018). To educate teachers who can embody the ideals set for Finnish higher education and teacher education (UNIFI, Citation2020) effort needs to be made to strengthen student teachers’ desire to act on participatory and justice-oriented levels.

Discovering universalistic purpose during teacher education could support student teachers’ readiness to broaden their purposes and adopt new ones enabling them to encourage future generations to adopt self-transcendent values and discover their purpose in life while simultaneously enhancing their citizenship. Offering student teachers more hands-on opportunities to explore their values, develop their competencies, and engage with community and state-level actors could enable them to understand the reasons behind their thinking and actions and support them in critical examination of existing social, cultural, and value-based structures to comprehend the underlying mechanisms of prevailing systems of governance (Bronk, Citation2014; Rautiainen et al., Citation2020; Westheimer, Citation2022). This could enhance student teachers’ purpose development and citizenship.

Attention also needs to be paid to student teachers’ beyond-the-self dreams. In the present study they encapsulated aspects of beyond-the-self orientation that were decidedly prevalent in the student teachers’ lives. Could these dreams be fostered to develop into more mature purposes through a purpose-oriented teacher education encouraging student teachers to make participatory and justice-oriented contributions? This needs further consideration.

Limitations and future studies

A strong connection with the existing purpose literature guiding this study is one of its strengths, but it may have influenced how the voices of the participating student teachers were heard and interpreted by the researchers. Conducting the interviews using an existing protocol in a semi-structured manner may have narrowed student teachers’ descriptions of their purposes to focus mostly on predefined perspectives, thereby limiting the number of original expressions or viewpoints about purposefulness that emerged during the interviews.

Also, during the analysis there was a marked focus on examining how purpose manifested in the accounts of the interviewees, specifically from the point of view of the three dimensions defined by Damon et al. (Citation2003). As a result, some counter-narratives, or novel pieces of information about how purpose was conceived by student teachers and featured in their lives might not have been captured during the abductive content analysis. Utilizing an inductive approach might have yielded different results. In the future it will be important to study student teachers’ purposes from this point of view as well.

The failure of Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) citizenship models to capture the meanings expressed by the student teachers related to their beyond-the-self dreams prompted us to develop the model by forming the beyond-the-self dreams subcategory. This can be seen as a significant contribution by the current study that elicited essential information about the student teachers’ purpose manifestations. Going forward, the ability of this new subcategory to effectively capture beyond-the-self dreams needs to be further scrutinized to validate its functionality.

Although it appears from the student teachers’ accounts that education was perceived to provide tools to promote beyond-the-self motivations in the confines of work, it was beyond the scope of this study to look at exactly how the current trends and practices in Finnish teacher education are associated with purpose development. In the future it will be important to study how purposeful student teachers perceive the role of higher education in their purpose development and what pedagogical practices they associate with increased purposefulness.

How purposefulness may promote student teachers’ democratic citizenship also needs further investigation. Investigating associations between the student teachers’ life purposes and the teaching profession (e.g., how student teachers realize their purposes by working as teachers) would increase the understanding of how purpose, teaching, and participatory and justice-oriented contributions are interlinked. This would support the development of more purpose and civic engagement-oriented teacher education.

Also, if teacher education is to guide student teachers towards adopting and promoting societally and culturally desirable ends, connections between citizenship, purpose in life and moral development need to be investigated further. For being purposeful, political, or socio-culturally active is not a guarantee of morality. Throughout history, religious zealots and dictatorial leaders have engaged in immoral actions to disseminate extremist ideas causing harm and pain to others while at the same time fulfilling the conditions set for being purposeful and showcasing intense political, societal, and cultural activism (Bronk, Citation2014; Damon, Citation2008; Damon & Colby, Citation2015).

By advancing the understanding of what purposeful student teachers’ sources of purpose are, how they contribute to the world beyond the self, and which actions they use to realise these contributions, we aimed to provide teacher educators with insights into purposefulness to support them in tailoring their educational practices to better promote purpose development. This could enable more students to find and embrace a universalistic purpose, encouraging them to contribute more at participatory and justice-oriented levels and embody the ideals of active citizenship. This is something the world needs now—perhaps more than ever before.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joona Moberg

Joona Moberg is a Master of Arts specialising in Lifelong Learning and Education who graduated from the Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Finland. His master’s thesis investigated how purpose manifests among purposeful Finnish student teachers. In 2021 he worked as a research assistant on the RESET research group focused on developing pedagogical tools that foster expansive learning and in 2023 on the CRITICAL project designing and conducting a multimodal research pilot that investigated student teachers’ graphic literacy skills. He is interested in enhancing teachers’ and education professionals’ agency by developing higher education in a more purpose and civic engagement-oriented direction.

Elina Kuusisto

Elina Kuusisto is a University Lecturer (diversity and inclusive education) at the Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Finland. She holds the title of Docent (Associate Professor) at the University of Helsinki, Finland. In 2018-2019, she worked as an Associate Professor at the University of Humanistic Studies, The Netherlands. Her academic writing deals with teachers’ professional ethics and school pedagogy, with a special interest in purpose in life, moral sensitivities, and a growth mindset.

References

- Arieli, S., Sagiv, L., & Roccas, S. (2020). Values at work: The impact of personal values in organisations. Applied Psychology, 69(2), 230–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12181

- Bronk, K. C. (2014). Purpose in life: A critical component of optimal youth development. Springer.

- Bronk, K. C., Hill, P. L., Lapsley, D. K., Talib, T. L., & Finch, H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271439

- Chen, H.-Y., & Cheng, C.-L. (2020). Developmental trajectory of purpose identification during adolescence: Links to life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 80(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.013

- Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200:AID-JCLP2270200203>3.0.CO;2-U

- Damon, W. (2008). The path to purpose: How young people find their calling in life. Free Press.

- Damon, W., & Colby, A. (2015). The power of ideals: The real story of moral choice. Oxford University Press.

- Damon, W., Menon, J., & Cotton Bronk, K. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2

- European Commission. (2019). Education and training monitor 2019 Finland. https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/et-monitor-report-2019-finland_en.pdf

- Finnish Government. (2020). International TALIS 2018 survey: Schools instil a sense of community more than before. https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-/1410845/international-talis-2018-survey-schools-instil-a-sense-of-community-more-than-before

- Fischer, R., & Schwartz, S. (2011). Whence differences in value priorities?: Individual, cultural, or artifactual sources. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1127–1144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110381429

- Frankl, V. (2020). Man’s search for meaning: The classic tribute to hope from the holocaust (Kindle ed.). Originally published in Germany in 1946. Penguin Random House.

- Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

- Heng, M. A., Blau, I., Fulmer, G. W., Bi, X., & Pereira, A. (2017). Adolescents finding purpose: Comparing purpose and life satisfaction in the context of Singaporean and Israeli moral education. Journal of Moral Education, 46(3), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2017.1345724

- Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., & Bronk, K. C. (2014). Persevering with positivity and purpose: An examination of purpose commitment and positive affect as predictors of grit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9593-5

- Joris, M., Simons, M., & Agirdag, O. (2022). Citizenship-as-competence, what else? Why European citizenship education policy threatens to fall short of its aims. European Educational Research Journal EERJ, 21(3), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904121989470

- Kallo, J. (2009). OECD education policy: A comparative and historical study focusing on the thematic reviews of tertiary education. Finnish Education Research Association.

- Kallo, J. (2021). The epistemic culture of the OECD and its agenda for higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 36(6), 779–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1745897

- Kuusisto, E., de Groot, I., de Ruyter, D., Schutte, I., & Rissanen, I. (2023c). Values manifested in life purposes of higher education students in the Netherlands and Finland. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2023.2279866

- Kuusisto, E., de Groot, I., de Ruyter, D., Schutte, I., Rissanen, I., & Suransky, C. (2023a). Higher education students’ life purposes in the Netherlands and Finland. Journal of Moral Education, 52(4), 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2022.2159347

- Kuusisto, E., de Groot, I., Schutte, I., & Rissanen, I. (2023b). Civic purpose among higher education students – a study of four Dutch and Finnish institutions. Journal of Empirical Theology, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1163/15709256-20231158

- Kuusisto, E., & Schutte, I. (2022). Sustainability as a purpose in life among Dutch higher education students. Environmental Education Research, 29(5), 733–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2107617

- Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2021). The challenge of educating purposeful teachers in Finland. Education Sciences, 11(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010029

- Lavonen, J. (2018). Educating professional teachers in Finland through the continuous improvement of teacher education programmes. In Y. Weinberger & Z. Libman (Eds.), Contemporary pedagogies in teacher education and development. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.77979

- Loader, B. D., Vromen, A., & Xenos, M. A. (2014). The networked young citizen: Social media, political participation and civic engagement. Information, Communication & Society, 17(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871571

- Lund, T. J., Liang, B., Mousseau, A. D., Matyjaszczyk, V., & Fleurizard, T. (2019). The will and the way? Associations between purpose and grit among students in three US universities. Journal of College Student Development, 60(3), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2019.0031

- MacPhail, C., Khoza, N., Abler, L., & Ranganathan, M. (2016). Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qualitative Research QR, 16(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115577012

- Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B., & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12051

- Marcus, J., Carlson, D., Ergin, C., & Ceylan, S. (2022). “Generation me”: An intra-nationally bounded generational explanation for convergence and divergence in personal vs. social focus cultural value orientations. Journal of World Business, 57(2), 101269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101269

- Melo, D. F., & Stockemer, D. (2014). Age and political participation in Germany, France and the UK: A comparative analysis. Comparative European Politics, 12(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.31

- Moran, S. (2009). Purpose: giftedness in intrapersonal intelligence. High Ability Studies, 20(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598130903358501

- Poutanen, M., Tomperi, T., Kuusela, H., Kaleva, V., & Tervasmäki, T. (2022). From democracy to managerialism: Foundation universities as the embodiment of Finnish university policies. Journal of Education Policy, 37(3), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1846080

- Punakallio, E., & Dervin, F. (2015). The best and most respected teachers in the world? Counternarratives about the “Finnish miracle of education” in the press. Power & Education, 7(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757743815600294

- Rautiainen, M., Männistö, P., & Fornaciari, A. (2020). Democratic citizenship and teacher education in Finland. In A. Raiker, M. Rautiainen, & B. Saqipi (Eds.), Teacher education and the development of democratic citizenship in Europe (pp. 62–73). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429030550-5

- Ryff, C., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

- Sagiv, L., & Schwartz, S. H. (2022). Personal values across cultures. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 517–546. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-125100

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology & Culture, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

- Sharma, G., & Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M. (2018). The relationship between college students’ sense of purpose and degree commitment. Journal of College Student Development, 59(4), 486–491. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0045

- Sloam, J. (2014). New voice, less equal: The civic and political engagement of young people in the United States and europe. Comparative Political Studies, 47(5), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012453441

- TENK. (2022). Responsible conduct of research (RCR). https://tenk.fi/en/research-misconduct/responsible-conduct-research-rcr

- Tirri, K. (2018). The purposeful teacher. In R. Monyai (Ed.), Teacher education in the 21st Century. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.83437

- Tirri, K., & Kuusisto, E. (2016). Finnish student teachers’ perceptions on the role of purpose in teaching. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(5), 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1226552

- UNIFI. (2020). Theses on sustainable development and responsibility. https://www.unifi.fi/viestit/theses-on-sustainable-development-and-responsibility/

- Universities Act (558/2009). https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2009/20090558

- Urukovičová, N. (2022). Generational differences in narcissism and value orientation. Ceskoslovenska psychologie, 66(3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.51561/cspsych.66.3.315

- Van der Walt, C. (2019). The relationships between first‑year students’ sense of purpose and meaning in life, mental health and academic performance. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 7(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v7i2.3828

- Veugelers, W. (2021). How globalisation influences perspectives on citizenship education: From the social and political to the cultural and moral. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 51(8), 1174–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1716307

- Westheimer, J. (2022). Can teacher education save democracy? Teachers’ College Record, 124(3), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221086773

- Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237

- Yeager, D. S., Henderson, M. D., Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., D’Mello, S., Spitzer, B. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037637