ABSTRACT

This essay investigates the assemblage, curation and reception of ‘oriental’ material culture at the Exhibition of Art Treasures of the United Kingdom held in Manchester in 1857. It does so to examine the relationship between exhibitions and empire in the mid-nineteenth century. Going ‘behind the scenes’ of the exhibition, interrogating the provenance of the objects and the actors involved in the assemblage, the essay reveals how some of the objects were infamous spoils of war, a detail omitted from the exhibition narrative as they were recast as ‘art treasures’, generously donated by their British owners for the benefit of the public. In analysing this dynamic, the essay builds on the current scholarship on imperial exhibitions by demonstrating an alternative, more subtle, way in which empire was ‘domesticated’ to British audiences. In addition, the essay challenges our current understanding of imperial exhibitions as masculine endeavours by revealing that Annette Royle played a key role in the curation of ‘oriental’ objects in Manchester, as well as at the other major exhibitions of Indian material culture in this period.

On 5 May 1857, the Exhibition of Art Treasures of the United Kingdom opened to the public. It was situated in Old Trafford, just out of the smoke that cloaked Manchester’s city centre. Over the next five months around 1.3 million visitors passed through the exhibition’s doors to see over 16,000 objects, including ‘Ancient’ and ‘Modern’ Masters, portraiture, ornamental arts, watercolour paintings, photographs and sculpture. The exhibition was the brainchild of Manchester’s manufacturing and merchant elite, who hoped an exhibition of art would combat the stereotype of their, and the city’s, impoverished cultural taste – a mission that also involved sponsoring a variety of other cultural initiatives in the city.Footnote1 Inspiration for the Art Treasures Exhibition came from the Great Exhibition of 1851, which, while championing Britain’s progress in manufacture and machinery, revealed the limits of the nation’s artistic heritage. This was further exposed at the Paris Exposition of 1855, where, for the first time, paintings were exhibited with manufactures and raw materials at an international exhibition. Sensing its importance, Prince Albert threw himself behind the Art Treasures endeavour, making it a national affair and cementing its pedagogic aims. As art treasures were lent from public and private collections across the United Kingdom, the exhibition showcased not only the nation’s cultural wealth, but also the liberal character of the nation’s rich in allowing the public to enjoy them. All the while, it also showed the power of Manchester’s elites to put it all together.Footnote2

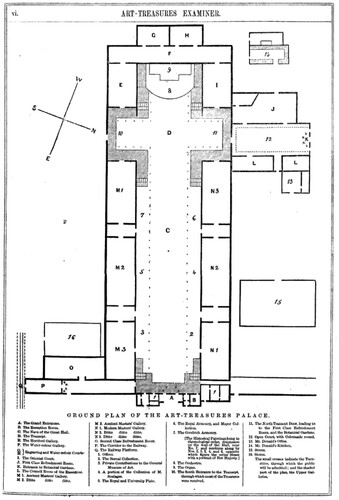

Scholars have recognised the cultural significance of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition. In scale and ambition the exhibition was unprecedented, becoming the largest art exhibition ever held in Britain. Moreover, in terms of art historical significance it played a key role in propagating the German curatorial practice of arranging paintings chronologically to show the development of art.Footnote3 Scholarly focus has predominantly been on the Western art, though the exhibition also contained many ‘oriental’ art treasures.Footnote4 The objects which fell into this category came from India, China, Persia (Iran), Turkey, Burma (Myanmar), Pegu (Myanmar), Tibet, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Nepal, Java (Indonesia), Siam (Thailand), Algeria and Japan. Most of these objects were housed in The Oriental Court, which was located at the back of the Grand Hall, at the upper end of the North Transept, though some, such as the Turkish metalwork and Chinese porcelain, were included in the Museum of Ornamental Art which occupied the centre of the building (). The ‘oriental’ objects were lent chiefly by the Queen and the East India Company (EIC), but also by the aristocracy, antiquarians, learned societies, merchants and manufacturers.Footnote5

Figure 1. Plan of Art Treasures Exhibition, Art-Treasures Examiner, vi. The Oriental Court was in Room I.

Louise Tythacott and Elizabeth Pergam have provided useful starting points for studying the ‘oriental’ objects on display in Manchester, examining The Oriental Court to ascertain attitudes towards Chinese and Indian material culture. This essay builds on these studies by more thoroughly investigating the Art Treasures Exhibition in the context of the imperial exhibitions of the nineteenth century.Footnote6 In addition to the catalogue, this essay uses previously overlooked sources, namely donation ledgers and correspondence between exhibition officials, which allow us to go ‘behind the scenes’ of the exhibition to examine its coordination. In doing so, the essay exposes absences in the official public discourse that warrant further examination.Footnote7 Specifically, the sources reveal how the display contained infamous imperial loot and that Annette Royle played a significant role in curating The Oriental Court. As will be shown, these finds not only further our understanding of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, but necessitate a reconsideration of mid-nineteenth century displays of empire more broadly. Moreover, I will expand on the current scholarship by paying closer attention to the visitors’ reception of the ‘oriental’ objects. In particular, the essay uses letters from mill workers about the exhibition to ascertain how working-class women – a group almost entirely excluded from exhibition histories due to the lack of sources – interpreted ‘oriental’ material culture.

Over the last 30 years there has been a wealth of scholarship on imperial exhibitions in Britain with The Great Exhibition of 1851 and Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 attracting the most interest. The Great Exhibition is seen as a starting point, with claims that the displays of raw materials and manufactures from the colonies, particularly India, aimed to ‘glorify and domesticate’ the empire.Footnote8 Bernard Porter, and more recently Jeffrey Auerbach have pushed back against this reading of the Great Exhibition, however. They say the majority of the exhibits were not colonial but European, and the organisers made no reference to how the exhibition could foster closer ties with the colonies. Most accounts note how the projection of empire changed at exhibitions as Britain entered the ‘new imperialism’ period, but Auerbach and Porter are most ardent in distancing the Great Exhibition from the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, which overtly championed the colonial project. Their reading of the Great Exhibition supports the assertion that empire was largely absent from mid nineteenth-century British culture more broadly.Footnote9

The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition presents a new lens for assessing the imperial character of mid nineteenth-century exhibitions. We may expect the main difference to stem from the fact in Manchester the exhibits were ‘art treasures’ rather than raw materials or manufactures which dominated the likes of the Great Exhibition and Colonial and India Exhibition. However, as this essay will show, despite the Manchester Executive Committee publicly distancing their display from the trade exhibitions, the ‘oriental’ objects in Manchester were framed as art manufactures, just like they were at the Great Exhibition. Where the Manchester exhibition provides new insights is in its national, rather than international or colonial scope. As the essay will show, exploring how ‘oriental’ objects – many of which were from British colonies – were translated into ‘art treasures of the United Kingdom’ presents a new context for studying how the empire was ‘domesticated’. In addition, the exhibition took place during a period of heightened imperial anxiety, it followed hot on the heels of the Anglo-Persian War (1856-1857) and ran during the Indian Rebellion (1857–1858) and Second Opium War (1856-1860) with China. If imperial propaganda was most needed during periods of anxiety, we would expect to see imperial discourses influence the display and reception of Indian, Persian and Chinese material culture at Manchester.

The first section of this essay looks at the purpose of the ‘oriental’ objects in the context of the Art Treasures Exhibition. It shows they were intended to provide fresh design ideas and knowledge of materials for manufacturers, models of exemplary workmanship for operatives, as well as to make the exhibition more entertaining. Next, I examine the provenance of the ‘oriental’ objects to demonstrate how formal and informal empires played a fundamental role in shaping the display. Here the looted objects are revealed. The final section assesses the arrangement, framing and reception of the ‘oriental’ objects. After restoring Annette Royle’s agency in curating the exhibition, this section analyses how and why the objects were divorced from their provenance as imperial plunder, and the extent to which the public interpreted the exhibition through an imperial lens. I conclude by posing some suggestions for further research on nineteenth-century exhibitions.

Art Treasures and Art Manufactures

Planning for the Art Treasures Exhibition began in the spring of 1856. From the beginning the Executive Committee were clear in asserting that the purpose of the exhibition was to educate the public on art and elevate their tastes. European fine art – painting and sculpture – was the priority. The Committee only speculated that ‘other branches of art’ may be included too, but by the end of November 1856, had agreed to include an ‘Oriental Museum’, which would contain ‘Asiatic and North African’ metal work, enamels, ceramic art, jewellery, glass, stained glass, furniture, mosaic work, textile fabrics, leather, ivory, glyptics and lacquer.Footnote10 That they prioritised European fine art, and restricted the ‘oriental’ objects to ornamental arts reflected the Western-centric hierarchy on which Europeans judged art. Europeans saw themselves only as having the genius and capabilities to produce fine art, whereas lesser cultures could at best produce ornamental art.Footnote11 Though delayed, and clearly not as important as European fine art, the decision does demonstrate that ‘oriental’ art was still cherished enough to be considered ‘art treasures’. The same cannot be said for the arts of the Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa, which were not yet appreciated in the West. These cultures were ranked below ‘the Orient’ on the civilisational hierarchy.Footnote12

Since the early nineteenth century there had been a growing appreciation for the artistic prowess of ‘the Orient’, and how it could help remedy the limits of British design. British imperial expansion facilitated aesthetic interest in ‘the Orient’, opening up more opportunities for Britons to visit ‘Eastern’ countries and study their cultures. In 1851 they only had to travel as far as the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London to inspect ‘oriental’ styles. The Great Exhibition was organised with the purpose of educating manufacturers about new materials and processes, as well as educating British society about importance of industry, mechanisation, design and taste. It played a key role in stimulating interest and appreciation of ‘oriental’ material culture. In particular, the Indian Court helped cement Indian manufactures in the canon of ornamental arts. Those pushing for the reform of British design, such as architect Owen Jones, waxed lyrical at the Indian textiles for the simple but effective patterns, colouring and workmanship. The attraction was not limited to the design reformers either, as the press remarked on the vast numbers who visited the court.Footnote13

On the back of the success of the Great Exhibition, the Treasury provided a grant to establish a Museum of Ornamental Art at Marlborough House in 1852, which eventually evolved into South Kensington Museum. The Museum of Ornamental Art was intended to improve British design and tastes, and ‘oriental’ objects were crucial to these plans. With the profits from the exhibition civil servant Henry Cole and the other reformers purchased many of the Indian manufactures which had been on display in Hyde Park, as well as Chinese and Japanese porcelain, lacquer and arms, and deposited them in the new museum.Footnote14 That the Executive Committee in Manchester opted to include their own Museum of Ornamental Art, and that it should include ‘oriental’ objects too, shows the legacy of the Great Exhibition in raising awareness, and encouraging appreciation of ‘oriental’ ornamental arts. Indeed, some of the objects on display at Manchester actually came from Marlborough House, including ‘Oriental porcelain’, showing a direct link from the Great Exhibition to the Art Treasures Exhibition.Footnote15 However, this is not to say that everyone agreed ‘oriental’ arts deserved the prominence they had gained in the design reform debates. Artist and art historian Ralph Wornum criticised the Indian objects at the Great Exhibition as ‘crude’ and inferior to British productions. Regarding the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester The Leader claimed the ‘Indian curiosities’ ‘were curious, rich and well arranged; but had about as good a title to admission of Art Treasures as the injected preparations from Surgeons’ Hall or the mummies from the British Museum’. Nevertheless, the clamour for ‘oriental’ art was much louder than the criticism and the majority of the reviews praised the objects on show in Manchester for their beauty.Footnote16

The task of soliciting all the ornamental arts for the Art Treasures Exhibition, including the ‘oriental’ objects, fell to John B. Waring. Waring was an architect, he had studied at the Royal Academy, co-wrote the guides to the architectural courts at Crystal Palace at Sydenham in 1854 and contributed to Owen Jones’s Grammar of the Ornament (1856). He was assisted in Manchester by George Redford, arts and sales correspondent for the Times, and illustrator Robert Charles Dudley, who had also been involved in the Mediaeval Court at the Crystal Palace. Antiquarian and dealer William Chaffers helped out too.Footnote17 Publicly the Executive Committee framed the exhibition as free from the vulgarities of commerce and manufacture, insisting their objective was to impart on the public the intrinsic value of art, but they clearly instructed Waring that the ornamental arts were intended to benefit British industry and manufacture. Waring informed potential donors that the ornamental arts at Manchester were intended to ‘elevate the public taste as regards the application of art to industry and illustrate by a chronological arrangement the history of works in metal, ivory, ceramic, glass, enamel, etc.’. In other letters Waring was more subtle, referring to ‘examples of art workmanship’, but could also be even more direct, describing the objects as ‘industrial art’.Footnote18 In the catalogue Waring stated his hope that the ornamental objects would provide ‘endless suggestions for fresh ideas’ for ‘those who are at present day engaged in similar pursuits’. This included the ‘oriental’ arts – when describing the Chinese porcelain in the Grand Hall he noted that the delicacy of colouring ‘has never been equalled by Europeans’.Footnote19 Here was an object lesson in design and manufacture from ‘the Orient'.

In December 1856 the Committee asked Dr John Forbes Royle if the EIC could contribute objects from the Company Museum and whether he could curate a dedicated Oriental Court.Footnote20 Royle had worked as a surgeon and botanist for the EIC and written widely on India’s natural resources. In the 1850s he was more widely known for his role in arranging the Indian displays at the Great Exhibition, Paris Exposition 1855 and Company’s Museum. The impact of Royle’s work at the Great Exhibition no doubt influenced the Manchester Executive Committee’s decision to appoint him. The Company’s collection, and Royle’s knowledge of Indian textiles had particular significance to Manchester’s cotton manufacturers, three of which sat on the Executive Committee. At this time cotton prices were rising steeply in the United States and Lancastrian cotton magnates were investigating alternative sources, with one eye on India. Royle’s commentary in the catalogue on the Indian textiles was a handy guide for manufacturers. He noted the fibres used (cotton, silk etc), and where best in India they were cultivated, as well as emphasising the ‘skill in design’, ‘patterns in which they were woven’ and ‘harmony and softness of colouring’.Footnote21 Of course, the exhibition’s Executive Committee would have expected manufacturers and merchants to enjoy the beauty of the paintings, but it does appear they also hoped they would also find new design ideas and resources from ‘the Orient’.

Royle’s commentary was aimed to assist visitors to appreciate the ‘oriental’ objects but at one shilling the official catalogue was out of the reach of the many of the visitors. This was reflected in the sales – around only one eighths of the visitors bought it.Footnote22 Priced at one pence, E. T. B’s unofficial What to See and Where to See It! Or the Operative's Guide to the Art Treasures Exhibition stepped in to fill this gap in the market. Other unofficial guides like A Peep at the Pictures intended to help the working-class audience understand the paintings, but What to See and Where to See it! claimed the ‘working-classes will enjoy the exhibition more thoroughly’ by prioritising objects which ‘afford greater enjoyment to the practical minds of the operative, than the ideal productions of the painters’.Footnote23 What to See and Where to See It! did not discuss The Oriental Court as a self-contained department but discussed it within the Museum of Ornamental Art. Breaking the objects down by material it encouraged comparisons between the European and ‘oriental’ productions. As with the official catalogue, this was not to create a narrative of European superiority. The ‘oriental’ objects were praised for their aesthetic and material qualities, for instance, it stated the ‘idols and bells exhibited in The Oriental Court should be examined, as they evidence great progress in the manufacture of metal’.Footnote24

It was not only guidebooks pushing the working classes to examine the ‘oriental’ objects. When a group of mill workers from Quarry Bank Mill in Styal, Cheshire visited the Exhibition in September, their ‘teacher’ took them to The Oriental Court where they looked at the Indian textiles. As with many other workers who attended the exhibition, these women’s tickets and guides were organised by their employer. The mill workers wrote their letters of thanks to ‘Madam Greg’, which was presumably Mary Greg (nee Philips), as she was married to Robert Hyde Greg, the owner of the mill.Footnote25 Robert Hyde Greg had inherited the mill from his father Samuel, and he also inherited his father’s active role in looking after the educational, spiritual wellbeing and health of the workers. At Quarry Bank the Gregs built a ‘model village’, with cottages for workers, a chapel and a school. Robert Hyde Greg’s paternalism extended beyond the ‘model village’ too, he was one of the founders of the Manchester Mechanics’ Institute and had put up five hundred pounds for the Art Treasures Exhibition project to help it get off the ground. Reflecting the gender ideals of the time, it was the women of the Greg family who were designated with overseeing the care of the workers, especially the women workers, a role they embraced, delivering classes themselves and in this case, organising the trip to the Art Treasures Exhibition. It is important to acknowledge that while the Gregs’ did provide many opportunities to their workers which were usually out of the reach of the working classes, they did so according to what they thought was best for the workers. Consequently, some historians have considered how their ‘paternalism’ was a form of social control, and it is within this context that we need to analyse the mill workers trip to Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition.Footnote26 Their visit resonates with the tradition of ‘rational recreation’ – it introduced the workers to civilised leisure activities and helped underline the Gregs’ liberalism. For this study it is interesting that the workers went to The Oriental Court specifically. We have no record of the teacher’s instructions from Greg, and it could just be the case that the letters referred to the Court as it stood out more than the rest of the exhibits, but the fact the women mention the Indian textiles could be evidence that the teacher – working under Greg’s instructions – took the women to see the textiles to broaden their understanding of their industry. This makes sense considering Robert Hyde Greg’s relationship with the Mechanic’s Institute, which had the same purpose.Footnote27

Working with textiles, the ‘oriental’ textiles would have been the easiest objects for the women to understand, but the Court’s exoticism would have brought enjoyment too. This was the intention – when enlisting Royle’s services, Executive Committee Chairman Thomas Fairbairn claimed the Court would be one of ‘the most attractive’.Footnote28 The Executive Committee knew the exhibition was to be educational, but also enjoyable and Fairbairn was probably thinking about the popularity of the Indian Court at the Great Exhibition. In Manchester the esteemed decorator Frederick Crace was contracted to paint the whole building. For The Oriental Court he chose dark green for the walls and ornamented the frieze above in ‘Indian style’, which meant arabesques of blues and reds, yellows and greens. This contrasted with the rest of the building, which Crace painted in maroon.Footnote29 The décor, and the brightly coloured objects which populated the Court promised to excite the visitor, and even transport them to foreign land. Journalist Blanchard Jerrold understood the significance of this, stating the ‘glowing colours’ and ‘emblems of Royalty […] make up a room full of Oriental treasures that must keenly interest the untravelled visitor’.Footnote30 In summary, whether as models for designers, inspiration for workers or exotic curiosities to thrill untravelled visitors, the ‘oriental’ objects had an important role to play in the exhibition.

Collecting ‘the Orient’

Determining what ‘oriental’ objects went on display in Manchester is made tricky by the fact there is no inventory of the EIC objects and the descriptions in Waring’s ledgers were written by Waring and his assistants, all of whom lacked expertise. These men relied on the lenders to inform them, but the lenders were also not necessarily clued up on their collections. Knowledge of ‘oriental’ cultures was rudimentary at this time, as shown by the many entries in the ledgers vaguely stating ‘oriental’, rather than a country. Royle was tasked with determining the geographical origin of these objects for the catalogue and while we may expect him to have a solid understanding of the Indian objects, Pergam has pointed out the gaps in his knowledge. An amulet described by Royle as Persian was actually from Bengal.Footnote31 Royle would have known even less about the rest of the objects. Nevertheless, these sources, read alongside the catalogue and knowledge of who was lending the objects, provides the best insight into what was on display.

Waring and his assistants collected at least seven hundred ‘oriental’ objects from twenty-six donors. Added to this was the EIC’s contribution which was substantial. Commentators said the EIC and the Queen were the main donors and seeing as the Queen gave around two hundred, we can assume the EIC gave something similar.Footnote32 Royle’s contribution helped share the load, but collecting and assembling the rest of the objects was still a huge task for Waring, especially as he had the European objects in the Museum of Ornamental Art to collect too. Whereas George Scharf who organised the ‘Ancient Masters’ department could consult Gustav Waagen’s Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854), which provided an overview of Britain’s paintings, Waring and his men relied on their own knowledge, personal connections and word of mouth. A large portion of The Oriental Court was thus shaped by what they considered ‘oriental art treasures’, as well as who they asked and what people were willing to lend. The other portion was determined by Royle.

Waring’s network comprised three main donor groups: the monarchy, private collectors (aristocracy, EIC officials, merchants/manufacturers and antiquarians), and public collections (learned societies and museums). Waring encountered some of the ‘oriental’ objects when searching for European decorative arts. This was especially true of the aristocrats, who had long sought out exotic and European luxuries for their country homes. But Waring was also evidently aware of the more specialist collectors, such as antiquarian Joseph Mayer who was part of the growing number of collectors with a focus on ‘oriental’ treasures.Footnote33 The owners Waring canvassed had differing motives and ascribed different meanings to their objects. Some of the objects were used for studying foreign cultures, such as Mayer’s religious idols and the Royal Asiatic Societies’ collection, while others were decorative, like the Queen’s porcelain and the Earl of Cadogan’s Japanese lacquer. It was Waring and his assistants’ job to visit these varied collections, bypass the collector’s priorities and select objects which met their standard of art treasures.

Royle’s job was similar. From the EIC’s heterogenous collection he looked specifically for objects showing ‘artistic skill in the art of decoration’.Footnote34 He made his selections from the EIC Museum which grew out of the Orientalist tradition that ruling the subcontinent was dependent on understanding its customs, languages, and culture. Once opened to the public the museum was also a means of educating Britons on Indian produce as well as propagandising the EIC. The Museum’s collection roughly fit into three categories: natural history (raw materials), trade and technology (manufactures), and miscellaneous (curiosities and war trophies). EIC officials zealously collected and donated their objects to the museum, and as the Company’s control over India increased, so did the museum’s collection, so much so that by 1858 the Company had to open a new museum.Footnote35

Royle selected similar objects to those populating the India displays at the Great Exhibition and at Marlborough House, and these matched what Waring had collected from elsewhere. Together they assembled a treasure trove of ornamental arts: arms and armour, textiles, examples of workmanship with silver and gold (e.g. jewellery and vases), bronzes, ceramics, ivories and carved wooden furniture. In addition, a few Indian, Persian and Chinese paintings found their way into the exhibition. Royle made clear with reference to the Indian paintings that these were ‘not shown so much as specimens of skill in the art’, but ‘as examples of what they could be capable of with the benefit of instruction’. Otherwise, the paintings were used as windows into ‘oriental’ life, with Royle explaining in the catalogue what the scenes depicted in terms of dress and cultural events.Footnote36 Thus, the ‘oriental’ paintings were chosen to give visitors a broad understanding of ‘oriental’ art and culture, which Royle span as evidence of the West’s superior civilisation; the orient may have had mastered ornamental arts, but they had much to learn when it came to painting.

At Manchester empire did not structure the display as it did at the Great Exhibition, where the colonies were grouped together in their own section and were even pointed out on a map of the world in the official catalogue. Still, we can see from the countries represented in The Oriental Court in Manchester that empire played an important role in the material assemblage. Objects came current and past colonies – India, Burma, Pegu, Ceylon, Malay, and Java (which was under British rule from 1811 to 1816). They also came from Britain’s informal empire, such as China, which had just ceded Hong Kong to Britain, as well as five treaty ports following defeat in the First Opium War (1839-1842). Likewise the EIC had political and military influence in Persia, Nepal and Turkey.Footnote37 Algeria, Siam, Tibet and Japan were not under British influence, and the small number of objects on display from these places reflected Britain's limited access to their treasures. As stated earlier the Committee set out to include North African objects but this only amounted to five from Algeria, which were not mentioned in the catalogue. Mayer, who lent Chinese, Indian and Persian treasures to Manchester had his own museum of Egyptian antiquities in Liverpool but none of these wound up in Manchester. This was most likely due to the fact in the 1850s Egyptian objects were widely appreciated as curiosities and as historical documents, but not art. Mayer’s objects could provide a window into the ordinary life of ancient Egyptians, but aesthetically they were not considered on a par with the more modern ‘oriental’ crafts.Footnote38

The majority of the objects came from India which is unsurprising given that by the 1850s the EIC had colonised most of the subcontinent, providing unprecedented degree of access to India’s natural resources, antiquities and manufactures.Footnote39 The EIC museum was the material archive of the Company’s imperial exploits and objects entered the collection through a variety of means, namely as purchases, plunder and gifts from princely rulers.Footnote40 This was evidenced in the exhibits in Manchester. The textiles – silks, velvets, muslins, laces, cashmere shawls – were purchased at ‘native bazaars’.Footnote41 Other Indian treasures were the spoils of war. The Morning Post noted the tent in the middle of Court previously belonged to Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore from 1782-1799. Tipu’s constant thwarting of British forces in the Anglo-Mysore wars, as well as his close relationship with the French meant he became increasingly villainised by the EIC and wider British society. After his defeat at Seringapatam in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1798-1799), there was a scramble to obtain his belongings – including arms, jewellery clothing and furniture.Footnote42 We cannot be certain that the tent was Tipu’s – the demand for his objects meant many had false attributions. However, the level of detail given in the Morning Post about The Oriental Court preparations suggests that they had been informed by Royle. While collectors in Britain could not be certain that their objects were actually Tipu’s, we would expect the EIC to be fairly sure of theirs.

The Queen lent Tipu loot too. Waring’s ledgers attribute two straight swords with fixed gauntlet, steel gilt and jewels to Tipu. The Royal Family had a long history of collecting arms that stretched back to the seventeenth century, and while some were gifts from foreign rulers – such as the Algerian pistols lent to Manchester – others were the fruits of plunder. The military’s prize system meant all loot was property of the sovereign, though in practice most the spoils were auctioned off and the proceeds distributed among the soldiers according to rank. The Royal Family had the chance to buy objects from these auctions, but the EIC often kept choice treasures aside to gift to the monarchy in a bid to legitimise their activities in India. Twenty-two lots from the Tipu plunder were given to the monarchy and at least two of these were put on display in Manchester.Footnote43

The rest of the Indian objects in Manchester – mostly weapons, bronzes and silver vases and bowls – came from private collectors and learned societies and once again, EIC influence was evident. Sir Robert Hamilton, Governor General of India for the EIC between 1852–1860 donated two matchlock pistols and Annette Royle (Royle’s wife) lent a sandalwood box.Footnote44 We do not know much about Annette Royle as a collector but research on wives of EIC officials, such as Lady Clive and Fanny Parkes, informs us that it was common for women to collect while in India.Footnote45 The RAS, Ashmolean Museum and Natural History Society (Newcastle), common destinations of EIC collectors’ gifts, also lent arms, deities and ivories.Footnote46 There is evidence of loot among the private loans too. General Lygon lent a suit of armour which he claimed previously belonged to Ranjit Singh, the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire. His possessions were obtained by soldiers and officers after British victory in the Anglo-Sikh War (1848-1849). Reverend Lambert donated what was referred to as Tipu Sultan’s hookah pipe.Footnote47

Chinese treasures made up the second largest portion of Waring’s acquisitions. He obtained about one hundred and fifty Chinese objects from China, half of which were porcelain and placed in the Museum of Ornamental Art. The rest went into The Oriental Court.Footnote48 Britons had been fascinated with Chinese luxuries, specifically porcelain, jades and ivories since the sixteenth century and by the time of the exhibition even more Chinese treasures, and new types of treasures, were entering British hands as loot from the First Opium War trickled into Britain and collectors in China, who had been restricted to Canton before the war, started advancing further afield thanks to the stipulations of the Treaty of Nanjing.Footnote49 The Chinese objects on display in Manchester bore the imprint of Britain’s imperial ambitions in China. The RAS sent a jade sceptre and an embroidered purse which Emperor Qianlong had given to Thomas and George Staunton during the Macartney embassy of 1793.Footnote50 Moreover, Mayer lent bronze deities which were seized during the First Opium War by Major Captain Edie and considering how British soldiers, as well as officers collected widely while on campaign in the First Opium War, and that their objects found a ready market back in Britain, it is possible that Ferenc Pulzsky and John P. Fischer’s bronze deities and incense burners were likewise looted from Chinese temples.Footnote51 Paintings were lent by MP Samuel Gregson who participated in and staunchly defended the opium trade, and Daniel Hanbury lent enamels from Shanghai, where his son ran a pharmaceutical company. Hanbury’s business venture was made possible by the Treaty of Nanjing, as was Messrs Hewitt and Company, an importer of Chinese and Japanese goods based on Fenchurch Street in London. They contributed to the China Court at the Great Exhibition and to Manchester sent Chinese bronzes, furniture and china. Hewitt and Co. also benefitted from Britain’s 1854 trade agreement with Japan, though the small number of Japanese objects they lent – vases and bottles in mother of pearl – showed how this trade was at an early stage. The other Japanese objects, of which there were around fifteen, were lacquer wares from the Earl of Cadagon and Duke of Portland as well as a suit of armour from the Queen.Footnote52

Waring acquired a sizable number of objects from Persia and Turkey too. Among the Persian treasures were, again, spoils of war. A carpet seized by the EIC from Persian troops who had plundered Herat was lent by John McNeill, who started off as a surgeon for the EIC but later became British Resident in Bushere in the 1830s. He also donated Persian paintings, textiles and jewellery. Persian swords and daggers came predominantly from the Queen and EIC, while the architect and Orientalist Edward Falkener lent metalwork.Footnote53 Indeed, Falkener was a major lender to the Court, donating around a hundred objects in total to the exhibition, most of which were Turkish which he had picked up during his travels in Asia Minor. The other Turkish objects were arms and armour lent by the Queen.Footnote54

The Queen, EIC and RAS, were the main contributors to the rest of the display, of which there was little: Burma (fourteen), Nepal (seven), Algeria (five), Ceylon (four), Java (three), Tibet (three), and Malay (two). Following the same pattern, the Queen lent weapons and the Company silks, jewellery and works in gold and silver. Antiquarians Fischer and Pulzsky lent a few Burmese and Javanese deities and Nepalese jades.Footnote55 Considering most of these regions were British colonies or part of the informal empire we may expect more treasures to have been available, but there were fewer collectors in these places than in India and China. Small numbers of treasures from Burma were donated to the British Museum by military personnel in the early nineteenth century, but the British Museum’s loan to the Art Treasures Exhibition only included glass and ceramics from the Bernal collection.Footnote56 Still, that it was the EIC, as well as the monarchy and RAS – two major recipients of EIC collecting – that made up the bulk of the material from these places demonstrates how Britain’s imperial reach underpinned the display, even if the displays were only small.

From Trophies of War to Art Treasures

When writing to Waring to outline his plans for The Oriental Court, Royle indicated that he was bringing his wife with him as she was ‘invaluable in arranging an Indian Collection’, and pointed to her work at the Great Exhibition as proof.Footnote57 None of the histories of the Great Exhibition and Art Treasures Exhibition have acknowledged Annette Royle’s curatorial role. At Manchester her contribution is easy to miss, her name is absent from the catalogues, press and the Manchester Executive Committee’s report. It is her husband who takes all the plaudits. At the Great Exhibition it was only in Royle’s report that her role as a curator was acknowledged as he pointed out he was ‘much indebted to Mrs. Royle for her assistance’. The catalogue did however list her as a lender.Footnote58 Newspaper accounts of Royle's death indicate his wife's substantial contribution, not only to those two exhibitions but also to the EIC museum in London and the Paris Exposition, where she earned a First-class medal for her efforts.Footnote59 Although no details of her work are given its clear she made an impact and yet it is her husband who historians have credited with popularising Indian material culture and domesticating empire to a mass audience. Her participation in these exhibitions adds evidence to the recent scholarship on EIC’s wives involvement in EIC activities and imperialism more broadly. Annette Royle was not unique in collecting or exhibiting colonial material culture – the aforementioned Fanny Parkes also organised her own exhibition of Indian curios, at her own expense, on her return to England from India.Footnote60 However, Annette Royle shows that women were important players in the large scale displays of imperial material culture too, displays which have previously been analysed as the preserve of men.

Together, the Royles divided the objects in The Oriental Court first according to geographic location and then material to showcase particular styles and encourage comparisons across countries and cultures. The Indian and Persian objects were on one side of the court with China on the other. Between the two, on the north side, was a case of Turkish objects, and on the other the objects from Burma, Pegu and Siam. The Tibetan and Ceylonese objects were in with the Indian and Persian objects and the Japanese objects were next to the Chinese.Footnote61 The objects from Malay and Algeria were not noted at in the catalogue and so its unsure where they were put. On the walls the Royles hung textiles as well as architectural drawings and further divided these according to Hindu and Islamic architecture. Objects of the same origin and material were put together in the cases, which included upright cases against the walls and long low cases in the centre. The catalogue further helped guide visitors to compare the different countries’ productions. Royle pointed out that the mixture of colours in a piece of Burmese silk were different to the Indian patterns, and asked the visitors to compare the Persian paintings with the Indian.Footnote62 For those without a catalogue it would have been tricky to know which objects were from where, but at least by grouping according to medium allowed visitors to make comparisons between similar objects.

The catalogue made no explicit reference to the countries as imperial possessions but did imply imperial relationships. For the calico prints Royle noted how.

Though the application of European skill and science now enables the calico printer of Europe to surpass in many particulars his brother workman of the East, yet the latter continues to produce patterns which have a crowd of admirers, from the skill with which they harmonise colour and proportion the ground to the pattern.Footnote63

Given the celebration in British culture of the war trophies obtained in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and Anglo-Sikh War it is surprising that the catalogue made no reference Tipu Sultan or Ranjit Singh’s possessions. Victory over Tipu was a turning point in the celebratory display of imperial warfare, spurring government sponsored festivities as well as popular ballads, paintings and plays. The popularity of Phillip Taylor Meadow’s novel Tippoo Sultaun (1840) and Tipu’s mechanised tiger in the EIC museum suggests the appetite for Tipu content had not dissipated by the mid nineteenth century. Interest was sustained by the EIC’s successive wars in India, which also gave rise to new villains. Battles from the Anglo-Sikh War, such as those at Multan and Gujrat were translated into shows at Astley’s amphitheatre, panoramas as well as plays.Footnote65 Advertising that the Court contained Tipu and Ranjit Singh spoils would surely have been an effective way of drawing more visitors to the exhibition and emphasising their treasured status, and yet this connection was not exploited.

The decision to divorce the objects from their identities as trophies of imperial wars provides further evidence that the mass exhibitions of the mid nineteenth century were not underpinned by the jingoism and militarism of those of the ‘new imperialism’ period. Even at the Great Exhibition, where empire was made more visible than in Manchester, narratives of imperial conquest were more sober than in the later exhibitions which included re-enactments of military victories.Footnote66 It is worth pausing here to consider the display of the most famous spoil of war at the Great Exhibition – the Koh-i-Noor diamond – as it provides a useful point of comparison to the Tipu loot at the Art Treasures Exhibition and furthers our understanding of the display of loot in the mid century more broadly. The Koh-i-Noor was taken from Maharaja Duleep Singh in the annexation of Punjab in 1849 and gifted to the Queen, who then put it on display at the Great Exhibition.Footnote67 While some commentators on the Great Exhibition saw the diamond as an imperial trophy (both with pride and trepidation), official exhibition sources tried to fix its identity within the remit of the exhibition, classifying it as an article of industry that demonstrated India’s diamond resources. Moreover, the catalogue detailed its entrance into British hands but in a matter of fact, legalistic way: it had belonged to the Lahore treasury, and all state property was ‘confiscated to the East India Company in part payment of the debt due by the Lahore government and of the expenses of the war’ after the ‘annexation of the Punjab’.Footnote68 The commentary cannot shy away from the military context by which the object came to Britain, but the language did not glorify its acquisition in warfare.

A similar process happened in Manchester whereby the spoils of war were transformed into art treasures. For the arms and armour, which made up a large portion of The Oriental Court, Royle classified some as ‘enamels’, and for those under the heading ‘Oriental Arms and Armour’ he said they were the ‘finest specimens of workmanship which have ever been brought together’. Even his Orientalist (in the Saidian sense) comment that some arms ‘would appear to belong to different ages of the world, but are all actually at use in present day’ was followed by a comment that these were ‘most elaborate in workmanship’.Footnote69 Kate Hill has shown this was also the case with Chinese objects at the International Exhibition in London in 1862. There the China Court contained textiles, enamels and a throne screen which the catalogue claimed were ‘from the Summer Palace’. This label hinted at the objects’ position as spoils of war – during the Second Opium War the British and French soldiers had infamously looted and burnt the Yuanming Yuan, the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. But, as Hill notes, these objects were generally subsumed into a commentary on design reform, rather than a statement of British military might.Footnote70 At the same exhibition the Koh-i-Noor’s catalogue entry did not recount its history as it did in 1851, instead it read ‘exhibited as a specimen of diamond cutting’ showing that it was the diamond’s cutting following its underwhelming reception at Hyde Park that framed its display.Footnote71

In Manchester, only with a ‘small carpet’ from Persia did Royle use language which intimated military acquisition. This object, lent by McNeill, was ‘obtained from the Persian soldiers who plundered the place [fortress of Sarakhs]’.Footnote72 Again, there was no celebratory tone to describe its seizure in war. In fact, the vague phrasing – ‘obtained’ – obfuscated how the British acquired the carpets. Considering that ‘plunder’ was associated with undisciplined wanton destruction, Royle’s use of plunder for the Persians and ‘obtained’ for the British implies that if the object was looted, it was done in a more ordered and proper way.Footnote73 As such, his commentary matches that of the description of the acquisition of the Koh-i-Noor in the Great Exhibition catalogue. Indeed, Paul Young has argued, as the Koh-i-Noor was in Britain as a consequence of robbery, it undermined the narratives of ‘peace and progress’ that underpinned the display.Footnote74 Young’s focus is on the media responses to the diamond but his analysis is helpful in explaining why the official catalogue presented the diamond’s entrance into British hands in a legal, sober tone – it maintained the image of Britain as a friendly, civilising force in India. Like the Great Exhibition the Art Treasures Exhibition was underpinned by the principle of ‘pacificist internationalism’, which is unsurprising considering Manchester was the home of free trade.Footnote75 At the opening ceremony Chairman Thomas Fairbairn pointed to the ‘positive and immediate good’ that was ‘likely to result from the bringing together of the eager and inquiring minds of our time, with the realisations of the genius of past ages and other countries’.Footnote76 The influence of this ideology in shaping the displays is evident in Royle’s ‘brother workman of the East’ remark, and how the Indian carpets showed ‘Indian applications of the great staple of Manchester’.Footnote77 These were imperial narratives, but ones which fitted more cleanly with the rhetoric of free trade than the spoils of imperial warfare.

Manchester’s national scale – the treasures were from Britons within Britain – provides another explanation for why the objects’ history as loot was obfuscated, and one which differentiates it from the international exhibitions. In a speech made prior to the exhibition Executive Chairman Thomas Fairbairn distanced the Art Treasures Exhibition from the Great Exhibition as it focused on art, likening it instead to the Vatican and the Louvre. He then explained that what made the exhibition unique was that while the Vatican was ‘the appropriate depository of the accumulated treasures of the ages’, and the Louvre displayed ‘the honourable trophies of warfare and the purchases of an imperial exchequer’, the Art Treasures Exhibition ‘will give proof to the world in 1857, of the unselfishness of Englishmen’.Footnote78 We have to be careful of reading too much into Fairbairn’s juxtaposition of the Louvre’s links to warfare and the Manchester exhibition. The plunder-filled Louvre drew both praise and criticism in Britain, but Fairburn’s comment gives nothing away as to what he felt.Footnote79 What Fairbairn does show is that the Manchester exhibition was framed as a story of the English elite’s generosity.

Spearheaded by the Manchester industrialists, the exhibition was part of the middle classes’ wider challenge to the landed aristocracy’s monopoly over Britain’s political, social and cultural life. Just as the campaign to repeal the corn laws was framed as contesting the landed elite’s self-interestedness at the expense of the poor, the exhibition was a challenge to the gentries’ protectionism over paintings. The Committee were aggressive in their canvassing of loans, appealing to the collectors’ liberalism and the exhibition’s philanthropic purpose. Those who lent were praised in the press and listed in the catalogue for all to see.Footnote80 In the catalogue this meant it was who lent the objects that was emphasised, not where or how they had got them. The ‘oriental’ objects’ provenances went no further than their British owners: Tipu and Singh’s objects were reclassified as the Queen’s, the EIC’s, Reverend Lamb’s and General Lygon’s which they had liberally shared with the nation. There were two exceptions. As noted, the catalogue said the Herat carpet was from the Persians, and a purse and jade were gifts from Emperor Qianlong to Thomas Staunton from when he, as ‘a little boy’, accompanied his father on the ‘British Embassy in 1792’.Footnote81 The former, as explained above, was framed in such a way as to not undermine the message of Britons civilising mission, and the latter was an intriguing story which projected a more cordial, and curious aspect of British diplomacy. The Staunton story is the closest the Art Treasures catalogue gets to mirroring its international exhibition counterparts where cordial global and colonial relations are suggested by the lists of lenders.Footnote82 Whereas the participation of colonial agents demonstrated Britain’s peaceful relationship with its colonies at the Great Exhibition, the focus on the participation of the nation’s rich was emphasised in Manchester. It was this focus on the rich’s generosity, along with the objects’ purpose as inspiring art manufacturers and the exhibition’s grounding in the principles of free trade which ultimately buried the ‘oriental’ objects history as colonial plunder.

That said, though not explicitly acknowledged, there were hints to the objects being spoils of war. The catalogue pointed out that the objects predominantly came from the EIC, which readers would have known for its plundering of India. Moreover, the catalogues referenced places of manufacture which were now famous due to the wars. Textiles were from Madras, ‘Mooltan’ (Multan) and the ‘lately much talked about city of Herat’, and arms were from ‘Scinde’ (Sind). All these locations of conflicts were popularised by press reports, and there was reconstructions of the battles of Multan and Scinde at Astley’s amphitheatre.Footnote83 The Royles’ arrangement of the court implied some Indian objects were war trophies too. Repeating the curatorial technique that they used at the Great Exhibition, they placed a tent in the centre of The Oriental Court and surrounded it with arms and furniture (). The tent’s interior was constructed in the style of an Indian ruler’s, containing finely styled clothing such as slippers and turbans, ‘emblems of royalty’, ‘fly flappers’, a chess table, carved furniture from Bombay and embroidered pillows and bolsters.Footnote84 This arrangement recreated a battlefield scene that allowed visitors to experience the thrill of gazing at an enemy Indian ruler’s treasures after passing beyond the guarded entrance. Given the prevalence of tents in the British literary and artistic representations of British conflicts in India, some visitors would have surely experienced the tent in this way. Barbara Hofland in The Captives of India: A Tale (1835) refers to ‘the gay and splendid tents of the native princes’, and Tilly Kettle’s painting Shah Alam Reviewing the Troops of the East India Company at Allahabad (c. 1781) is from the perspective of inside the Shah’s tent. Meadow’s Tippoo Sultaun provided a rich description of the interior of Tipu’s tent, which closely matched the arrangement of the one in Manchester.Footnote85

While there were hints in the official catalogue and arrangement of the Court these did rely on visitors making the imaginative leap. This ultimately depended on their exposure to colonial news and cultural representations. Readers of the Manchester Guardian and Morning Post were given a head start in this respect, as these papers actually noted that the tent and some of the arms formerly belonged to Tipu. They also called India ‘our eastern territory’, made explicit reference to the Persian war when discussing the carpets from Herat and noted how Mayer’s Chinese bronzes were ‘obtained from native priests’ on Putuo Island in China.Footnote86 The account by Manchester clergyman Robert Lamb published in Fraser’s Magazine shows that visitors were cognisant of the objects’ imperial provenance and that this knowledge conjured feelings of imperial superiority. Lamb described the EIC and India as ‘that powerful company which rules over our Eastern territories’, described the swords on display as those ‘which the Rajahs heralded without mercy’ and referred to the ‘pipe from which Tippoo Saib puffed his smoke, indifferent to the cries of his victims’.Footnote87 Lamb’s impression of Indian rulers was clearly shaped by the dominant images circulating in print and on stage, particularly as he was writing during the Indian Rebellion where once again the stereotype of merciless Indians was peddled. Neither the catalogue nor the press mentioned the pipe formerly belonged to Tipu, raising the question of how Lamb knew. Perhaps, as it now belonged to Reverend Lambert, he learnt through a religious network. Whatever the reason, he shows how visitors had access to unofficial, imperial narratives of the exhibition, and thanks to his work readers of Fraser’s Magazine knew the pipe’s provenance too.

The private letters of the eight workers from Quarry Bank Mill provide an alternative interpretation of the exhibition. From the formulaic sentences that appear in the letters we can assume that the women with stronger literacy produced templates, which the other women copied. As a result, we mostly see a collective response, though there was chance for originality to shine through.Footnote88 The Oriental Court clearly made an impression on the women. They all mention the Indian Tent and three women – Hannah and Mary Henshall and Margaret Walker – used the same language to describe the experience: ‘we went to see the Indian Tent we were muched [sic] amused with all in that room espacially [sic] the slippers that were turned up at the toes’. The exoticism of the Indian objects was what stood out for these women, rather than their craft or, as with Lamb, their evidence of a barbaric culture. That the women found them amusing was not an expression of cultural superiority, they also noted the ‘laughable pictures’ among the European exhibits, such as the one of a ‘boy eating porridge’, which referred to Hans Memling’s painting. Like many visitors to the Great Exhibition, it seems these women lacked the language to describe the objects they were confronted with and instead used emotive language.Footnote89

The Hensalls and Walker’s response goes someway in supporting Charles Dickens’ prediction that the working classes, with their ‘uninstructed eye’, would miss the Art Treasures Exhibition’s lessons. Dickens was concerned about the vast number of exhibits, expense of the catalogue and lack of labels for objects. The mill worker’s letters show that even those with a teacher could struggle to comprehend the exhibition.Footnote90 However, Dickens overlooked the fact that the exhibition contained ornamental arts which gave operatives an entry point to the exhibition. The Henshalls and Margaret Wallace remembered ‘some muslin dress pices [sic] in the same room [Oriental Court]’ and another woman wrote she was ‘very delighted to see a beautiful bed’.Footnote91 Their recognition of the materials and appreciation shown towards the craftsmanship of the bed contests the notion of the ‘uninstructed eye’. Another mill worker Mary Moore professed to be ‘confused and bewildered’ by the number of objects in the exhibition, but had the eye to appreciate an ‘Indian box most cut and carved beautifully’.Footnote92 It was not just the working classes who felt more comfortable in the Oriental Court either. The American writer Nathanial Hawthorne admitted being ‘better able to appreciate’ the objects in the Museum of Ornamental Art and ‘Oriental Room’ than the paintings.Footnote93 Finally, Dickens missed how the exhibition was meant to be fun as well as educational. The Oriental Court was intended to intrigue visitors and the mill workers’ amusement at the Indian slippers suggest it did just that.

Of course, eight letters are not representative of all working class engagement with ‘oriental’ material culture but when compared with Lamb we can see how class and gender impacted the extent to which one could link the objects to the wider imperial project. Regional identity was significant too, as evidenced by the visit of proclaimed heir to the Awadh, Prince Mirza Muhammad Hamid Ali Mirza Bahadur, and his uncle General Mirza Sikandar Hushmat Bahadur. The princes had travelled to the United Kingdom in 1856 as part of a delegation of deposed Awadh royalty, along with lawyers, interpreters and servants, who sought to appeal to the Queen, parliament and the EIC board of directors about the EIC’s annexation of Awadh in 1856.Footnote94 The Awadh royalty’s presence in Britain attracted much media interest and the princes visit to Manchester was no exception. The visit, undertaken before the exhibition was formally opened, was memorialised with a photograph taken by Leonida Caldesi ().

Figure 3. Leonida Caldesi, ‘The Princes of Oude, India, at Manchester Art Treasures, 1857’. Image reprinted with kind permission of Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

The image shows the princes in the centre of the image, linking arms with British men – the younger prince with Alderman Benjamin Nicholls (acting on behalf of the Mayor) and the elder prince with Major Bird, the Awadh agent in London and staunch critic of the EIC’s colonisation of Awadh. The press used the princes’ visit to legitimise the authenticity of The Oriental Court but we do not know what they actually thought of the objects. All the papers indicate they were especially interested in the Court, and the Guardian even said they had ‘some remembrance of’ the objects.Footnote95 Waring’s log does not contain any detail of objects having Awadh provenance, but we can assume the objects they remembered were either gifts the rulers had sent to the British Royal Family and EIC officials, or those taken by the EIC during their expansion into Awadh. Either way, the location of the objects in an exhibition showcasing the United Kingdom’s cultural wealth would have jarred with the princes who were attempting to expose the brutal realities of British rule.

The brutal realities of empire impacted the exhibition directly on October 7 when, at the request of Queen Victoria, Britain held a Day of National Humiliation on account of the ‘grievous mutiny and disturbances which have broken out in India’. News of the rebellion had preoccupied the press since the spring but over the summer increased reporting of the violence committed against civilians caused indignation and fear. The rebellion was interpreted in Christian circles as a failure to propagate the gospel, and this failure needed to be recognised with a Day of Humiliation. Businesses, transport and other public affairs, including the Art Treasures Exhibition ceased for the day as the public were encouraged to pray and fast to God so as to ensure the peaceful end to the ‘mutiny’. The sermons preached across the country justified Britain’s violent suppression of the uprising as a moral crusade – the acts of the rebels characterised as barbaric and fanatic.Footnote96 Lamb wrote his account of the exhibition after the Day of National Humiliation and his description shows how visitors with strong Christian convictions saw the Indian objects at Manchester, especially the weapons, as emblems of barbarism once the exhibition re-opened. The exhibition closed its doors for the last time on October 17 and a report from the Manchester Examiner and Times shows how the Rebellion continued to provide a backdrop to the displays. Reporting on the packing up of cases, the paper remarked that The Oriental Court ‘presents a scene of as much disorder as would probably be found at this moment in our oriental dominions’.Footnote97 More than an opportune (and distasteful) reference, this comment shows how empire framed visitors’ interpretation of The Oriental Court in particular.

Conclusion

This essay has shown how empire shaped the material assemblage of ‘oriental’ objects at the Art Treasures Exhibition. Digging into the provenance of the exhibits, it has demonstrated that some objects were connected to infamous instances of looting, and yet when we shift attention to how the objects were exhibited we find that the objects were divorced from their military background. This was because the purpose of the exhibition was not to champion the military strength and aggression of the EIC, but to educate and entertain the general public, and to showcase Manchester’s and the nation’s cultural wealth, as well as the rich’s generosity. As such the spoils of war were re-cast as ‘art treasures’, which were to be admired for their workmanship and to intrigue visitors through their exoticism. Moreover, it was their status as British objects which was emphasised meaning their pre-British ownership biographies were omitted.

The decision to have an Oriental Court in Manchester rather than a colonial court, and the move made to refashion the trophies of war as art treasures, the Art Treasures Exhibition at first appears to support Bernard Porter’s claim that empire had limited reach into British culture prior to the 1880s.Footnote98 However, on closer inspection the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition further exposes the limitations of Porter’s definition of imperialism.Footnote99 Just because imperial conquests were not explicitly celebrated in Manchester does not mean that empire was absent from the displays or that the public did not pick up on them. The Manchester organisers had much to gain by stoking interest and educating the public in Indian textiles and there were ample clues throughout the display about the objects’ imperial provenance. Whether or not the clues were picked up on is a separate issue, and while the likes of the mill workers show that empire may not have been a consideration, Lamb shows it could also be the primary frame of interpretation.

This essay has shown through an analysis of the classification and curation of the ‘oriental’ objects that there is much to be gained from looking at the subtle ways in which imperialism was exhibited in the mid nineteenth century. Historians have been too quick to read the presence of loot at exhibitions as evidence that they were intended to serve as trophies of empire.Footnote100 We need to pay closer attention to the ways in which these objects were framed within the official discourse, as well as how they were interpreted to better appreciate how imperial material culture was domesticated and or glorified. This means going ‘behind the scenes’ of the exhibition to ascertain how the objects’ meanings altered when they were put on display. As demonstrated here, such an approach also challenges our understanding of who produced knowledge at these exhibitions. A reliance on the official, public facing exhibition materials has meant that scholars have overlooked the role Annette Royle played in the mass exhibitions of Indian and ‘oriental’ material culture the nineteenth century. There is as much to be gained by examining what was missing from the displays, as well as what was there.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have happened without the help and encouragement of Julie-Marie Strange, Max Jones and Peter Yeandle. I would like to thank them, and the anonymous reviewers who have helped to improve the article immensely.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Pergam, The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857. On the Manchester elite’s cultural ambitions see Gunn, The Public Culture of the Victorian Middle Class.

2 Pergam, The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857.

3 Pergam, The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857; Rees Leahy, “Art, City, Spectacle,” 7–19.

4 By ‘oriental’ I am using the exhibition’s classification of the objects. I unpack this category in section one.

5 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 166–174. Manchester City Library M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2

6 Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese, 112–118; Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 181–208. See also MacGregor, Company Curiosities, 206–208.

7 For a similar method see Joshi, “Miles Apart.”

8 Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas, 52–58; Hoffenberg, An Empire on Display; Kriegel, Grand Designs, 87–120; Young, Globalization and the Great Exhibition.

9 Auerbach, “Empire Under Glass,” 112–117; Porter, The Absent-Minded Imperialists, 91–93, 134–163.

10 Report of the Executive Committee, 4; Manchester Art Gallery, Wilding and Lockyear Scrapbook of Art Treasures Exhibition, < https://manchesterartgallery.org/explore/title/?mag-object-36040> [Accessed 25 September 2023]; “Art Treasures Exhibition,” Manchester Guardian, 27 November 1856, 3.

11 Clunas, "Oriental Antiquities/Far Eastern Art," 323–326.

12 Clunas, "Oriental Antiquities/Far Eastern Art," 323–326; Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects, 116–118.

13 Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters, 221–237; Crinson, Empire Building, 23–35; Sloboda, “The Grammar of Ornament,” 223–36.

14 Auerbach, The Great Exhibition 1851, 9–24, 99–101; Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters, 228–229; Kriegel, Grand Designs, 87–120; Barringer, “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project,” 15.

15 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 161–162.

16 Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters, 225; “Three Visits to the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition,” The Leader and Saturday Analyst, Issue 375, May 30, 1857: 509–510; Scharf, “On the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, 1857,” 303.

17 Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 186–188; Waring, A Record of My Artistic Life, 241.

18 Report of the Executive Committee; MCL, M6/2/7/1, “Mr. Waring's Letter Books,” 10, 18,75, 105.

19 Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 188–201; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 137, 141–142.

20 M6/2/4/2, “General Out letter Book,” 445.

21 Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 188–201; Beckert, Empire of Cotton, 123–125; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 166–174.

22 Report of the Executive Committee, xxvi.

23 E. T. B, What to See and Where to See It!, 4.

24 E. T. B, What to See and Where to See It!, 7.

25 It’s possible the letters were for Margaret Greg (nee Broadbent) who married Robert and Mary’s son Edward. As Robert was running the mill at this time though, Mary was more likely to be involved. Quarry Bank Archive (QBA) 765.1/5/1/6-13. With thanks to Alkestis Tsilika for the information on the recipient of the letters. See also “Voices of the Mill Workers.”

26 On Greg’s paternalism see Rose, The Gregs of Quarry Bank Mill, 102–122. For donation to exhibition see Report of the Executive Committee, xl.

27 Auerbach, The Great Exhibition of 1851, 11, 75–77.

28 Quoted in Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 187–188

29 Report of the Executive Committee, lvi.

30 Jerrold, Jerrold’s Guide to the Exhibition, 33.

31 Pergam, “An Ephemeral Display within an Ephemeral Museum,” 195–196.

32 Queen and EIC highlighted specifically in Report of the Executive Committee, 20; Scharf, “On the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, 1857,” 303. Waring’s ledgers shows seven hundred objects acquired, including Queen’s contribution see MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2.

33 Barczewski, Country Houses and the British Empire; Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects, 123–131.

34 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 167.

35 Desmond, The India Museum 1801–1879, 1–78; MacGregor, Company Curiosities, 168–190.

36 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 166–176.

37 On India, Ceylon, Burma, Pegu, Malay and Nepal see Jasanoff, Edge of Empire; Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 292, 324; Mercer, “Collecting Oriental and Asiatic Arms and Armour”. On China and Turkey see Kasaba, “Treaties and Friendships: British Imperialism”. On Persia see Onley, The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj Merchants, 12–36; Potter, “The Consolidation of Iran’s Frontier,” 129–131.

38 Gatty, Catalogue the Mayer Museum Part 1; Moser, “Wondrous Curiosities,” 72–73, 93–105, 125–130, 165–180, 200–215; Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 262–264.

39 Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 274–341.

40 Desmond, The India Museum 1801–1879; Finn, “Material Turns in British History: I”; Finn, “Material Turns in British History: II”; MacGregor, Company Curiosities, 167–191.

41 In a letter to Waring, Royle says he will transfer textiles from Manchester Mechanic’s Institute. Press report indicates these were bought at bazaars. MCL M6/2/10 “Letters from Officials to Officials,” 76; “Mechanics' Institution Exhibition the East Indian Collection”. Manchester Guardian, 16 September 1856, 3.

42 “The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition”. Morning Post, April 23, 1857, 2; Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 170–184.

43 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1; Taylor, Empress, 17–18, 39–47, 55; Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 180–183; Hannam, “Georges, Nawabs and Nabobs” <https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/publications/eastern-encounters/chapter-2> [Accessed 25 September 2023]; The Algerian items were gifts from the Dey of Algiers to George III in 1811 and 1819 see “Grand Vestibule: The British Monarchy and the World – Algiers,” <https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/Trails/grand-vestibule-the-british-monarchy-and-the-world/algiers >[Accessed 25 September 2023].

44 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 170–172.

45 Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 187–196; Goldsworthy, “Fanny Parkes (1794–1875)”.

46 Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 296–298; Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1:1 (1824): xi–xv; Harle, Topsfield, Indian Art in the Ashmolean Museum; Loughney, “Colonialism and the Development of the English Provincial Museum, 1823–1914”.

47 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2; Voigt, “Mementoes of Power and Conquest”.

48 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 173–174

49 Bickers, Scramble for China, 77–112.

50 Hevia, Cherishing Men from Afar.

51 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 173–174; Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects, 71–73; Hill, “Collecting on Campaign,” 227–252.

52 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2. On Hewitt and Co. see Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects, 87–92.

53 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1–2; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 164–174.

54 MCL M6/2/24 “Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend,” 1. On Falkener see Aitchison, Ward, “Falkener, Edward”.

55 MCL M6/2/24 ‘Lists of Works of Art Owners are Willing to Lend’, 1–2; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 173–174.

56 Green, “From India to Independence,” 449–463; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 161–162.

57 MCL M6/2/10 “Letters from Officials to Officials,” 76.

58 Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition [Volume 4], 927–929; Reports by the Juries, 1449.

59 “Productive Resources of India”. Morning Post, August 13, 1858, 6.

60 Goldsworthy, “Fanny Parkes (1794–1875)”. See also Hill, Women and Museums.

61 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 164–174.

62 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 164–174.

63 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 169.

64 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 167.

65 Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 175–182; Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 354–372; Qureshi, “Tipu’s Tiger and Images of India,” 212–214; Gould, Nineteenth-Century Theatre and the Imperial Encounter, 164–166.

66 Auerbach, “Empire Under Glass,” 111–141; MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire, 96–120.

67 Dalrymple, Anand, Koh-I-Noor.

68 Young, “Carbon, Mere Carbon,” 343–358; Kinsey, “Koh-i-Noor,” 391–419; Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition [Volume 2], 696.

69 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 171.

70 Hill, “The Yuanmingyuan and Design Reform in Britain,” 56.

71 International Exhibition 1862: Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department, xvi; Kinsey, “Koh-i-Noor,” 391–419

72 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 168.

73 Hill “Collecting on Campaign,” 229–230. Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 174

74 Young, “Carbon, Mere Carbon,” 343–358.

75 Auerbach, “Empire Under Glass”, 113–117; Young, Globalization and the Great Exhibition, 128–131.

76 Report of the Executive Committee, 28–29.

77 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 168.

78 “The Art Treasures Exhibition at Manchester – No. I”. Manchester Guardian, March 16, 1857, 5.

79 Gilks, “Attitudes to the Displacement of Cultural Property in the Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon”, 136.

80 Pergam, The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, 25–28.

81 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 174.

82 Barringer, “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project”, 11.

83 Auerbach, “Empire Under Glass,” 121–122; Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 168–172; Gould, Nineteenth-Century Theatre and the Imperial Encounter, 164–166.

84 Catalogue of the Art Treasures Exhibition of the United Kingdom, 173.

85 Hofland, The Captives of India, 192; Meadow, Tippoo Sultaun, 363–365. See also Hardinge, The Aftermath of the Battle of Ferozeshah; Martens, Battle of Ferozeshah; “The War in India”. Illustrated London News, February 24, 1849, 117; “The War in India,” Illustrated London News, March 10, 1849, 161; “General Woodburn’s Moveable Brigade Shelling the Encampment of the 1st Regiment of Cavalry of the Hyderabad Contingent at Aurungabad”. Illustrated London News, September 5, 1857, 241.

86 “Art Treasures Exhibition: Selections in Art, Vertu, &c. From Her Majesty the Queen”. Manchester Guardian, January 14, 1857, 4; “The Art Treasures Exhibition at Manchester. – No. VI”. Manchester Guardian, April 27, 1857, 6; “The Oriental Court”. Manchester Guardian, May 2, 1857, 5; “The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition”. Morning Post, April 23, 1857, 2; “The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition,” Morning Post, April 27, 1857, 2.

87 Lamb, “Manchester and its Art Exhibitions of 1857,” 385–386.

88 “Voices of the Mill Workers”.

89 QBA 765.1/5/1/6-13; Cantor, “Emotional Reactions to the Great Exhibition of 1851,” 238–240.

90 Dickens, “The Manchester School of Art,” 350.

91 QBA 765.1/5/1/6-13.

92 QBA 765.1/5/1/6.

93 Hawthorne, Passages from the English Note-Books, 307.

94 “The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition”. Morning Post, April 23, 1857, 2; Fisher, Counterflows to Colonialism, 411–422

95 “The Art Treasures Exhibition at Manchester. – No. VI”. Manchester Guardian, April 27, 1857, 6.

96 Randall, “Autumn 1857: The Making of the Indian ‘Mutiny’,” 3–17; Sugirtharajah, The Bible and Empire, 63–97.

97 “Art Treasures Exhibition – The Closing Day”. Manchester Examiner and Times, October 24, 1857, 6.

98 Porter, The Absent-Minded Imperialists, 134–164

99 See Burton, “Review of The Absent-Minded Imperialists,” 626–628.

100 Hoock, Empires of the Imagination, 393.

References

- Aitchison, George., and Rachel. Ward. “Falkener, Edward [pseud. E. F. O. Thurcastle] (1814–1896), architect and Archaeologist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (23 Sep. 2004). Accessed September 20, 2023.

- Auerbach, Jeffrey. “Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851-1911.” In Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire, edited by John MacKenzie, and John McAleer, 111–141. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

- Auerbach, Jeffrey. The Great Exhibition 1851: A Nation on Display. London: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Auslin, Michael R. Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. London: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Barczewski, Stephanie. Country Houses and the British Empire, 1700-1930. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

- Barringer, Tim. “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project.” In and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, edited by Tim Barringer, and Tom Flynn, 1–27. Abingdon: Routledge, 1998.

- Bates, Rachel. “Exposing Wounds: Joseph Cundall and Robert Howlett’s Royal Assignment.” Critical Military Studies 6, no. 2 (2020): 118–139.

- B., E. T. What to See and Where to See It! Or the Operative's Guide to the Art Treasures Exhibition. Manchester: Abel Heywood, 1857.

- Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

- Bickers, Robert. Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire 1832-1914. London: Penguin, 2012.