Abstract

Marara (carved trees, dendroglyphs or tapholgyphs) are a distinct part of Wiradjuri Country in southeastern Australia. Each marara displays a unique muyalaang (tree carving) that a Wiradjuri person carved into the outer surface of a tree after removing bark. Marara mark the dhabuganha (burials) of Wiradjuri men of high standing, representing part of traditional cultural practices that extend into the deep past. Yet, the meaning of these sacred locations is not widely understood due to the lack of Wiradjuri teaching, knowledge and participation in previous studies. Here we present the first Wiradjuri-led archaeological study of marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha, completed in the Central Tablelands. We combine a review of previous studies with new information from interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders, Ground Penetrating Radar survey, and 3D modelling (photogrammetry) – guided by the Wiradjuri philosophy Yindyamarra (cultural respect). The results build new, culturally and scientifically informed understandings of practical and symbolic aspects of Wiradjuri culture, with marara and dhabuganha viewed not as individual objects or ‘sites’ but as connected parts of Wiradjuri Lore, beliefs, traditional cultural practices and Country. Consistent with Wiradjuri Elder requests, this paper is freely available and written in simple language for the Wiradjuri community and beyond.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following contains information about deceased persons and ceremonial practices. This paper also discusses Men’s and Women’s Business with the permission of the Gaanha-bula Action Group.

Introduction

Traditional burial practices are an important part of the cycle of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. These practices change across Australia and over time (e.g. Bowler et al. Citation1970, Citation2003; Lowe et al. Citation2014; Moore et al. Citation2020; Pardoe Citation1988; Pretty Citation1977; Sutton et al. Citation2013; Stone and Cupper Citation2003; Thorne and Macumber Citation1972), showing that different language groups express cultural meaning (symbolism, or symbolic expression) in different ways. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples guide study of these sacred locations, preferring non-invasive ways to better understand their Ancestors and to develop culturally appropriate ways to manage and protect their resting places (e.g. Lowe and Law Citation2022; Roberts et al. Citation2021; Sutton et al. Citation2020, Citation2021; Wallis et al. Citation2008). Yet, in the past, many burial locations were excavated, and Ancestors removed, without consent from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The marara and dhabuganha of Wiradjuri Country, southeastern Australia, are an important example of traditional Aboriginal burial practices. Traditionally, a sheet of bark was removed from one or more trees and the bare surface was carved to face the burial of a Wiradjuri man of high standing, where a burial mound was built. Many marara are shown and described in published books and articles produced by non-Wiradjuri people (e.g. Black Citation1941; Etheridge Jnr Citation1918; Fitzpatrick Citation1913; Howitt Citation1904; McCarthy Citation1940, Citation1945). For the Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders involved in the current study, this previous work is culturally inappropriate and inaccurate and without Traditional Custodian and community consultation, mixing information from different language groups and needing careful reconsideration through Wiradjuri perspectives.

Marara can also be seen as part of a much larger – but fragile – tradition of Aboriginal culturally modified trees in Australia. This tradition includes trees as sources of food (Cole et al. Citation2020; Dardengo et al. Citation2019; Morrison and Shepard Citation2013; Tutchener et al. Citation2019) and bark and/or wood for making shields, coolamon (containers), canoes and other wooden items (Cole et al. Citation2020; Dardengo et al. Citation2019; Griffin and Cooper Citation2019; Tutchener et al. Citation2019; Webber and Burns Citation2004) or other purposes (Spry et al. Citation2020). It also includes carved trees with specific cultural meaning in northern New South Wales (NSW) (Etheridge Jnr Citation1918), far northeast tropical Queensland (Buhrich and Murison Citation2020; Buhrich et al. Citation2015), and northern Australia (O’Connor et al. Citation2022).

This Wiradjuri-led study seeks to build new understanding of marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha against this background. An important part of the approach developed for this study is talking face-to-face with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders about their views of these sacred locations, previous work, and the place of marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha in the bigger picture of Wiradjuri Lore, beliefs, traditional cultural practices and customs and Country. This study combines a review of previously written books and articles (literature review), interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey and 3D modelling (photogrammetry). This paper begins with a description of the two study areas that are the focus of this paper and their background, before presenting the methods and results of this study.

Study area and background

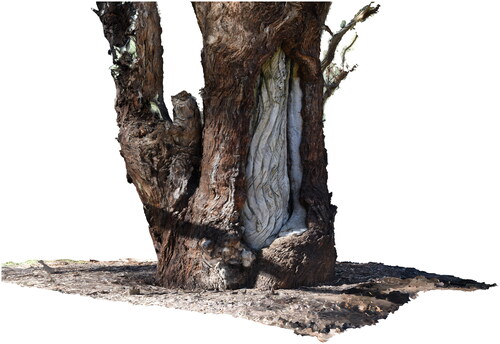

The two study areas are located on Wiradjuri Country near Molong, NSW (). Molong rises between 500–700 m above sea level in the Central Tablelands (formally known as the Lachlan Tablelands), an area of fairly level high ground that slopes gently to the west from the Great Dividing Range (Pogson and Watkins Citation1998; Webb Citation2017). The Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council is responsible for managing Aboriginal cultural heritage in the two study areas.

Figure 1. Map showing location of study area in relation to NSW, Wiradjuri Country, Central Tablelands and Molong (left), and Australia and New South Wales (right).

The first study area is a travelling stock reserve (TSR), surrounded mostly by cleared paddocks. The TSR contains a large number of mature native box eucalypt trees, but few shrubs and smaller plants. The buried rocks and soils in the TSR are gravel, sand, silt and clay (alluvium; Krynen et al. Citation1997). National Parks and Wildlife Services (NPWS) recorded two burials at this location in 1979, following a report made by a local farmer. According to the NPWS site card, two dhabuganha are located on opposite sides of a creek bend, in fenced-off areas. The first dhabuganha belongs to a Wiradjuri man of high standing, marked by a single marara (live standing yellow box; NPWS site card). The muyalaang displays parallel, curved lines and a large diamond in the lower right-hand side (). An unknown person removed scar regrowth from the muyalaang with a chainsaw in the late twentieth century (NPWS site card). At the time of first recording, only ‘a few small bumps about 5 cm high’ indicated where a high burial mound once stood (NPWS site card). These ‘bumps’ are no longer visible today.

Figure 2. Top to bottom, and left to right: photographs of TSR carved tree, TSR carved tree detail, TSR fallen scarred tree, Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4, Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 1 detail (with inset image showing carved tree from afar).

The man’s ‘wife’ is reportedly buried on the other side of the creek, approximately 200 m away (NPWS site card). A fallen scarred tree (unknown eucalyptus species) marks the woman’s dhabuganha (NPWS site card) (). The scarred tree is relatively intact, suggesting it was still standing when the woman was buried, and only fell more recently.

The second study area is Yuranigh’s Grave, a public tourist park with little remnant native vegetation. Yuranigh’s Grave is the final resting place of Yuranigh, a Wiradjuri man who guided surveyor Sir Thomas Mitchell during expeditions into different parts of Australia in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century (Glasson Citation1949; Pike Citation1967). When Yuranigh passed away in 1850, he was buried traditionally in volcanic soils and rocks with four (or possibly five) marara surrounding his dhabuganha. Mitchell later added a sandstone headstone to Yuranigh’s dhabuganha – an unusual practice for a European person at the time.

The muyalaang at Yuranigh’s Grave are mostly hidden behind scar regrowth, apart from one live standing yellow box (Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 1; ) and a dead standing unknown eucalypt species (Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4; ). The muyalaang on Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 1 shows many small diamonds, which are almost totally covered by scar regrowth. An unknown person cut back the original scar regrowth to expose the muyalaang in 1976 (NPWS site card). The muyalaang on Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4 shows a series of diamonds drawn one inside another with a single, continuous line.

Physical remains of Aboriginal activities and places are common in the wider region. CS undertook a search of the NPWS Aboriginal Heritage Information Management System (AHIMS) on 8 November 2022. A total of 52 sites are registered within approximately 20 km of both study areas. Most of these sites are stone artefact scatters or ‘Potential Archaeological Deposits’; seven scarred or carved trees and one stone quarry are also recorded.

Following the 2019–2020 bushfires and a study of a nearby Aboriginal culturally modified tree with a stone tool embedded in a scar (Spry et al. Citation2020), the Central Tablelands Local Land Services, Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council, and Gaahna-bula Action Group requested a collaborative research project to investigate the marara and dhabuganha at both study locations.

Methods

The principles of the Wiradjuri philosophy Yindyamarra guided the methods used for this study, which include a review of previous work, interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders, GPR survey, and 3D modelling (photogrammetry):

Uncle Neil Ingram: Yindyamarra is a Wiradjuri philosophy of cultural respect, where you acknowledge all people—especially our Elders—and show respect, go slow, be gentle in your approach, and have understanding … The thing is, we get too caught up in clever talk, eloquence. Too many clever words. And it takes it away from what we’re talking about … We, as Elders, we need to make sure that our talk is simple, and direct, and truthful. We’ve got to be careful that the scientists, and the archaeologists, and all these clever people don’t take away from what we believe our cultural heritage is all about.

Review of previous studies and interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders

This study approaches the literature review of marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha as a respectful, shared process between researchers and Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders. CS reviewed published articles and books, and unpublished reports, on marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha. She discussed the results in person with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders over a series of recorded group interviews in 2021–2022. The interview participants were Wiradjuri Elders Aunty Alice Williams, Uncle Neil Ingram and Knowledge Holder James Williams. Greg Ingram (Wiradjuri Traditional Custodian), Ian (‘Doug’) Sutherland (Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi Traditional Custodian) and the Yarruwala Ngullubul Men’s Corporation also participated in the interviews. The interviews were held in-person at the TSR () and offices of the Central Tablelands Local Land Services and the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council. Only women were allowed to attend the interview at the woman’s dhabuganha, which was guided by Aunty Alice Williams.

Figure 3. Interviews with Wiradjuri Elders, knowledge holders and community at the TSR. From left to right, Caroline Spry, Chris Jones, James Williams, Uncle Neil Ingram (in front), Greg Ingram (behind), Terry McLean, Ian 'Doug’ Sutherland, Dale Carr, Aiden Leonard, Aunty Alice Williams, Kayla Nugent and Michelle Hines.

A point-by-point discussion of the literature review provided the opportunity for Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders to culturally evaluate information published without the permission or participation of Wiradjuri people in the past. The presentation of this point-by-point discussion below, with responses by Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders included throughout, is deliberately designed to recognise the literature review as a respectful, shared process. In many cases, responses by different Elders and knowledge holders are included on purpose to provide richer understanding of the point discussed, or to respectfully show where there has been agreement or a difference of opinion. It also recognises that no single Wiradjuri Elder or knowledge holder can speak for all Wiradjuri people.

CS recorded the interviews on her iPhone 11, and transcribed the interviews using Otter.ai software. CS discussed transcripts with the interview participants, who provided approval for selected parts of the transcripts to be included in the current study to provide a more developed understanding of marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha.

The interviews were conducted in accordance with Human Research Ethics approval HEC21356, approved by La Trobe University in 2021.

Ground Penetrating Radar survey

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is a non-invasive method of analysing and mapping changes in soil, and detecting layers, features and objects in the ground (Conyers Citation2013). GPR systems work by sending electromagnetic energy in radar waves at different frequencies into the ground, recording their return to the ground surface, and measuring the travel time and converting it to depth. A ‘reflection’ occurs when a radar wave meets anything that is ‘different’, which might be stones, moisture differences or air pockets. Those radar waves then travel back to the ground surface to be recorded, while the other waves continue to move deeper, also to be reflected.

BA and CS completed two GPR surveys at the TSR on 22–23 February 2021 to investigate the dhabuganha reported in the NPWS site card (Armstrong et al. Citation2021). The first survey took place at the man’s dhabuganha, and the second at the woman’s dhabuganha. The details of each survey area and equipment settings are presented in .

Table 1. Details of GPR survey in Survey Area 1 and Survey Area 2.

Four main criteria were used to identify potential dhabuganha (reflection features of interest) in the GPR survey results:

the recorded reflections should be moderate- to high-strength (amplitude) (Conyers Citation2013);

the reflections should cut across the ground layers (Conyers Citation2013), including the change from sandy loam to clay at a depth of 0.6–0.8 m below the ground surface (Ian Packer, pers. comm., 2021);

the reflections should be located around 19.5 m southeast of the marara or in front of the scarred tree (NPWS site card); and

the reflections should be about the size of a human body, or similar to the dimensions and depths of dhabuganha documented previously (around 0.6 m wide, 1.2 m long, 1.2 m deep; see below).

The GPR survey produced an individual image of reflections (reflection profile) for each portion walked (transect) in the survey area. Each reflection profile displays the distance surveyed in metres (m) from left to right (lower axis), and travel times from top to bottom (vertical scale) in nanoseconds (ns). The profiles were first processed to remove background noise and then ‘gained’ to enhance reflections at the depth of interest. Arch-shaped reflections (formally known as hyperbolic-shaped reflections; Conyers Citation2013) were used to measure radar wave speeds so that travel times could be converted to physical depths. The total depth of investigation at this site was about 1.5 m, as all energy had disappeared (dissipated) below this depth.

All reflection profiles were joined up (interpolated) in specialised computer software to create horizontal slice maps (formally known as amplitude slice-maps; Conyers Citation2013) which display the strength of reflections across a whole survey area from a bird’s-eye view. Each horizontal slice was programmed to be 5 ns (0.4 m) thick. Only the first five slices (0–1.5 m depth) were investigated as dhabuganha are unlikely to extend deeper than 1.2 m below the ground surface (see below).

3D modelling (photogrammetry)

Photogrammetry is a method of creating 3D models from photographs in specialised computer software. BA completed a photogrammetry survey of the culturally modified trees and dhabuganha, between 22–26 February 2021. He took a series of overlapping photographs of each tree or dhabuganha using a Nikon D850 DSLR camera (45.7 Megapixels) with a Nikon 35 mm f/1.8G FX AF-S lens. One continuous run of overlapping photographs was taken at each tree or dhabuganha location. The camera settings and software used are presented in .

Table 2. Camera settings and software used for photogrammetry in Survey Area 1 and Survey Area 2.

Results

Review of previous studies and interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders

Previous studies of Wiradjuri burials and carved trees show and describe their appearance, location and arrangement. Some also present unverified information about the symbolic meaning of Wiradjuri carved trees. The interview participants involved in this current study reviewed this information together during the group interviews. At the same time, they shared traditional cultural knowledge about marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha, and also Wiradjuri Lore, beliefs, traditional cultural practices and customs and Country more generally to provide context for understanding these sacred locations.

Uncle Neil Ingram began discussions by explaining why trees have always been important to Wiradjuri people:

Uncle Neil Ingram: So, [think of] trees as a giver of life, you see. That’s why trees are so important to Aboriginal people. They’ve got seeds, and food, and shade, and shelter. They would say we have a responsibility to care for Country, to look after Country, and the waterways … and Country and waterways would look after us.

Aunty Alice Williams: There’s a lot of knowledge involved in just this burial [TSR men’s dhabuganha], and the one over there [TSR woman’s dhabuganha]. Yes, there’s a lot of questions. But a lot of the answers are written here. But you need to open your mind and think further than what’s on the tree, and what’s in the ground, and have a look around, and see what’s there.

Aunty Alice Williams: I like to look at the whole landscape [Country], and think about where people camped at, to come in and actually do this stuff [dhabuganha ceremony]. And if people came in from different aspects—is it north, south, west or whatever—where were they travelling from? And that’s where they camped. So, you’re not looking for one camp site, you’d be looking for a couple of camp sites, dependent on their relationships with their totem connection to these people. And what they belong to … Yes, see, are there any bush turkeys around [here] anymore [at the TSR]? People would not know that now because that animal has gone. But we’ve seen a lot of other animals come out today. Young and old. So, young kookaburras, a lot of magpies. We haven’t seen any land animals … Yes, [it’s a matter of] just looking at that bigger, bigger picture. And if people are coming in to do this, they’ve got to eat. The water [creek] is there. I always say to people, what time of year do you think they might do this [traditional practice]? What’s around to sustain them? What’s edible? So, there’s that bigger picture that you need to look at … everything’s laid out in your landscape. Where you go, what you do, where your totems are, where your Lore is. So, it’s all there. You've got to know how to read that, so someone’s got to teach you … It [woman’s dhabuganha] is located within a bigger cultural landscape. So, there’s other cultural features out here—scarred trees, possibly camp sites. There’s most probably a tool making area. There are mountains around us. It [woman’s dhabuganha] sits around in a, sort of, valley. And the water that divides the two sites—the creek—would be significant in our culture. Water being the giver of life, and signifying the continuing of our people.

Aunty Alice Williams: We [Wiradjuri people] know what we can do and where we can go. That's built into our psyche. And that’s knowledge that’s hundreds of thousands of years old, that stuff. Not 60,000, 80,000, 100,000 years old. It’s in our DNA, it runs through our blood. And that knowledge is in us.

Aunty Alice Williams: Kings and Queens—it’s not our culture.

Uncle Neil Ingram: It’s not how our Ancestors would describe our people.

Greg Ingram: It was implemented by the colonisers.

While most written accounts suggest that Wiradjuri women, boys and uninitiated men were reportedly buried without ceremony (Black Citation1941:18; Etheridge Jnr Citation1918:11), there is one published reference to a woman’s dhabuganha with a marked tree. This tree was reported to contain a diamond marking with a small circle and dot in the middle (Pearce Citation1897:100). Aunty Alice Williams draws attention to this reference, but also states that the absence of markings on a tree associated with a woman’s dhabuganha did not lessen her status in Wiradjuri culture:

Aunty Alice Williams: So, although this [fallen scarred tree at the woman’s dhabuganha] is not carved, and the man’s [tree] is [carved] … Maybe that’s because he was of higher order than her, if you want to call it [that]. It does not signify that she was any less. It’s just the way it was.

Greg Ingram: So, this is Goobothery Station [showing a printout of the Evans Citation1820 engraving]. This is where me and Dad [Uncle Neil Ingram] come from. As you can see, that’s a burial mound. Those three things that curve [around] the burial mound, they are actually what you call mourning seats. They were prepared and created by women and children. And when that happens, the women mourn there. They hit themselves and give themselves sorry scars—or something like that—on their heads. So, to me, that identifies that women are a major part of this process … I believe the funeral process is inclusive of all the clan. And even extended kinship … (Uncle Neil Ingram: Yes) (Ian Sutherland: I agree with you).

Uncle Neil Ingram: Women have always been part of our culture, with their knowledge, their responsibilities in teaching, and their connection to Country. (Greg Ingram: Yes) And I agree with what you’re saying. And even though Women’s Business is Women’s Business, Men’s Business is Men’s Business … (Greg Ingram: It’s separate) Yes, even through teaching, learning, initiation and all that. But at funeral times, it’s a time when men and women come together, (Greg Ingram: Exactly) because we do respect their [women’s] role in our society.

Greg Ingram: And that’s the thing—women prepared, [and] were part of the process. Women actually prepared this man’s body [TSR carved tree], do you know what I mean? So, to actually disregard that is not teaching proper culture, (Uncle Neil Ingram: Yes) I feel.

Aunty Alice Williams: Our role in the old society is a big one! Because we’re the ones that bred those boys up to become men and tell them about the plants, and how to do this and how to do that. So, we taught them how to hunt and get all the foods out of the ground, and taught them how to identify different fibres for different uses and collect bush tucker. (Greg Ingram: Yes) We had them for 12 years, maybe 13 [years]. So, our influence on those boys was enormous. And those skills that we taught them let them become the hunter and gatherers that they had to be after they were initiated. They went after the big game. We still collected all the little game and all the plants. That’s women’s business.

In one published account dating to 1817, Surveyor-General John Oxley described a Wiradjuri burial and associated carved trees at Goobothery Hill, NSW (Murray Citation1820:29-30 July). Oxley excavated this burial without permission from the Wiradjuri community. While the disturbance of this grave is distressing to Wiradjuri people, Oxley’s description contains information about the length, width, depth and construction methods of this dhabuganha that informed the GPR investigations at the TSR investigated for this study:

The form of the whole was semi-circular. Three rows of seats occupied one half, the grave and an outer row of seats the other; the seats formed segments of circles of fifty, forty-five, and forty feet each, and were formed by the soil being trenched up from between them. The centre part of the grave was about five feet high, and about nine long, forming an oblong pointed cone. On removing the soil from one end of the tumulus, and about two feet beneath the solid surface of the ground, we came to three or four layers of wood, lying across the grave, serving as an arch to bear the weight of the earthy cone or tomb above. On removing one end of those layers, sheet after sheet of dry bark was taken out, then dry grass and leaves in a perfect state of preservation, the wet or damp having apparently never penetrated even to the first covering of wood … the body deposited about four feet deep in an oval grave, four feet long and from eighteen inches to two feet wide. The feet were bent quite up to the head, the arms having been placed between the thighs. The face was downwards, the body being placed east and west, the head to the east. It had been very carefully wrapped in a great number of opossum [sic] skins, the head bound round with the net usually worn by the natives, and also the girdle: it appeared after being enclosed in those skins to have been placed in a larger net, and then deposited in the manner before mentioned … to the west and north of the grave were two cypress-trees distant between fifty and sixty feet; the sides towards the tomb were barked, and curious characters deeply cut upon them, in a manner which, considering the tools they possess, must have been a work of great labour and time.

The marked grave tree is that of a boy [probably a younger, initiated man] who died in 1852, and in 1865 this grave was ten feet deep; in it then was a tomahawk, pipe clay, an opossum [sic] rug, pipe, the body had been bound with hide, and the leg bones were broken below the knee. This was in a very large burying-ground, and the blacks came once a year to clear the graves and do up the mounds and fences.

Greg Ingram: I think landscape probably dictated the site [dhabuganha location]. Maybe Dad [Uncle Neil Ingram], James [Williams] and Aunty Alice [Williams] can talk about that a little bit more. I think Country probably determined where things were. But I'll leave that up to my Elders, who have more information.

James Williams: Look, Greg [Ingram] just touched on it, and it depends on the type of trees that are around. A lot of scarred trees and carved trees were done on yellow box. But then, there are other factors involved. And if you look at Yuranigh’s Grave, there’s a quarry close by which was used as part of the burial too. So, it’s [a matter of] looking [around] at the resources that were available. And if we’re looking at that big sheet of bark being taken off the tree, we need to be sure if it’s associated with this burial [TSR man’s burial]—that there was something around that could be used. Soil? Nothing’s worse than trying to dig a hole in rocky soil. So, that was the other factor.

Aunty Alice Williams: I was involved in an article on TSRs a long time ago—about the cultural values that are in these TSRs, and how they connect back to our people because they are built on our travel paths (Uncle Neil Ingram: Yes). So, they built the TSRs because all the resources are available [there]: food and water, and shelter … A lot of the TSRs hold our cultural values—plants, animals and everything else.

James Williams: You’ve only got to look at this place [TSR] as a place of tranquility, peace, calmness. And you can understand why they chose this very special spot. So … just to be on Country is so important to us. Because we feel it. And we listen to it. And we learn.

Aunty Alice Williams: There’s a calmness about the area [TSR woman’s burial]. It’s pretty tranquil … So, they’ve most probably laid her to rest across from him [TSR man’s burial] for obvious reasons: they’re back on Country. The site’s most probably associated with the totems that they were given.

Aunty Alice Williams: The aspect [of the carved face] is really important. You’ve got to take north, south, east, west out of the picture. Where things face is really important, because we come from all over different Country for ceremony and different activities. The aspect tells you what that person’s relationship is in terms of that cultural landscape and where they’re coming from. So, they’re facing home. Their mob, when they come in for that burial, will be facing that way too. So, wherever their camp is, they’ll have it facing the same direction. Even when other mobs come in, they face towards their own direction—where they travelled in from. So that identifies where their Country is.

James Williams: But listen, everyone’s got their different Dreamtime stories. Every which way they’re told, people can say, ‘Oh it’s different from this one [story], and that one [story]’. But if you look at four or five people jumping in a car, and travelling from here to Sydney, and when you get to Sydney, everybody told their story about what they saw on the road—not everybody sees the same thing. (Uncle Neil Ingram: That’s right) (Aunty Alice Williams: For sure) And so, it’s what story relates to you, is what you tell [pass on], and what you’ve seen, or what your family’s seen, or what you were told as a kid. And that’s how it is with the different variations in Dreamtime stories.

Aunty Alice Williams: Different people have different views on how that works … The women maintained those sites. They might have only come through when they were coming for ceremony with the men, or they might have come up for women’s business. I know that on our Country, they [women] used to come and take care of places and maintain an area because it was significant to all of us because we have a common Ancestor … There are 26 different language groups within the Wiradjuri nation, and each had different cultural practices—they weren’t all the same.

Uncle Neil Ingram: Everyone’s got their stories. They may be different. That doesn’t mean they’re wrong. And we need to be mindful and respectful of that. And that’s in line with our philosophy Yindyamarra.

The interview participants share that marara and muyalaang reflect pathways between the earth and sky world:

James Williams: Look, if you look at some of the trees, it shows paths—the design itself … And, this one [TSR carved tree] over here to me is a path from here—this life—to the next life. And, traditionally, the spirit stays on this site until the growth [scar regrowth] covers it [the muyalaang] over. And then that’s when they [the person who passed away] go to the skyworld. [Caroline Spry: So, the spirit stays until the tree overgrows, or covers the whole carving?] Once that’s done then the spirit’s gone, but they follow the path that’s on that carving. But it’s a marker, when other people come … you can see the relationship to an individual if they happen to come across it [a carved tree], and they’ll know what skin group here that fella [who passed away] is.

Greg Ingram: Baiame’s our Creator, our Sky Spirit. And he’s actually got a special place up there, where he lives. And then he’s reserved a place for all of us up in the river on the side of the Milky Way. And that’s what James [Williams] is talking about, the pathways to get to that stage.

James Williams: With your ceremonials [Kamilaroi ceremonial trees], you’ll look at mainly animal figures, even flora. You can see the trees or the plants in some of the carvings. With these trees [marara], this [muyalaang] is associated with the story of the person who’s been buried.

Aunty Alice Williams: They’re [the muyalaang] connected back to the totems that are in this area. So, a lot of the carving method was [reflective of] the totem [of the deceased person] … It must have been a pretty important person [buried at the TSR carved tree], because of the carving on the tree. Maybe that’s his totem, or it was where he comes from. I don’t talk about men’s business because that’s not my business.

Uncle Neil Ingram: It’s all to do with the different clan groups and their stories. But I think it [the TSR carved tree] all represents this man’s life and his journey.

Aunty Alice Williams: [The diamond is] a Wiradjuri marking … It’s a universal symbol for Wiradjuri people.

Greg Ingram: Yes, universal, symbolising both parties [men and women] …

Aunty Alice Williams: And the diamond represents the sky. (Ian Sutherland: Yes) Yes, the star.

Caroline Spry: So, it’s something that also potentially relates to astronomy, to stars in the sky?

Aunty Alice Williams: Yes, it does. It’s universal, and it’s universal to Wiradjuri.

Aunty Alice Williams: A lot of that stuff is not spoken about. It’s kept within those mobs of people. That’s the rules. So, it’s not appropriate [to discuss the meaning of marara and muyalaang in more detail], and I wouldn’t talk about a scar on a man’s tree.

From the interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders, it is clear that previous studies paint a picture of marara, muylaaang and dhabuganha that is disconnected from cultural understanding of these sacred locations. The interview participants view marara and dhabuganha as places of tranquillity, calmness, peace and association with totems. They see marara and dhabuganha not as isolated sites, but as connected parts of Wiradjuri Country. The interview participants believe that, symbolically, marara and muyalaang tell the story of pathways and the person who is buried, their life and journey, and their totems (or the totems of the lands where they are buried). They see the diamond as a Wiradjuri marking, universal to all Wiradjuri people, with connections to the skyworld and astronomy. However, information about the symbolic meaning of marara and muyalaang is sacred and culturally sensitive, and should not be documented and/or shared without the consent or input of Wiradjuri people.

Ground Penetrating Radar survey

Survey Area 1

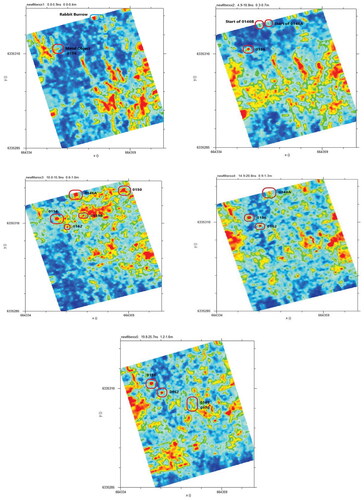

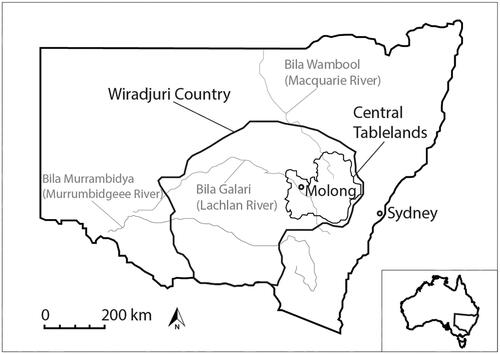

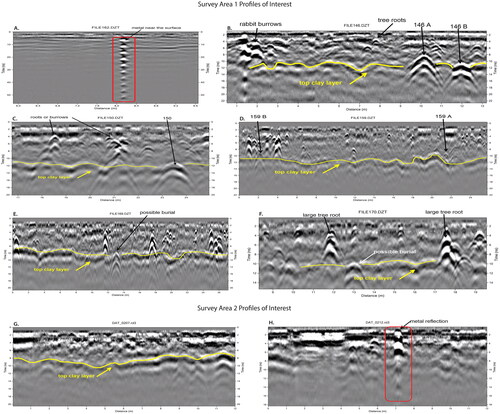

The results of the GPR survey in Survey Area 1 show nine areas of interest (potential dhabuganha, or reflection features) in the reflection profiles ( and ). They also show disturbances such as tree roots and rabbit burrows (e.g. ). Two are probably near-surface objects that ‘ring’ when the radar waves intersect them, producing reflections that appear deeper in the profiles (reflections features 0156, 0162, e.g. ). These are typical of metal objects, perhaps barbed wire or scrap metal. Reflection feature 0146B appears to represent large tree roots, which can be seen at shallower depths in the reflection profile (). Reflection features 0146 A and 0150 have more potential to represent dhabuganha, as visible cuttings that extend into the clay layer (). However, their locations do not correspond with that described in the NPWS site card (19.5 m southeast of the marara). Reflection features 0159 A and 0159B appear to cut into the clay layer (), and their locations are more consistent with that described in the NPWS site card. Yet, they are not as high-strength as reflection features 0146 A or 0150.

Figure 4. Locations of nine areas of interest detected in the reflection profiles in Survey Area 1 (note that 0156 and 0162 are metal).

Figure 5. Processed reflection profiles (A) 0162, (B) 0146, (C) 0150, (D) 0159, (E) 0169, and (F) 0170 in Survey Area 1, and (G) 0207, and (H) 0212 in Survey Area 2.

The final two areas of interest extend across two neighbouring reflection profiles (reflection features 0169 () and 0170 (). This suggests a minimum feature size of 1 m. Both reflection features are high-strength, similar to reflection feature 0146 A. This may indicate a larger disturbance, closer to the expected size of a dhabuganha. This feature is located 19 m south of the marara, a similar distance to that described in the NPWS site card. The interview participants agreed that reflection features 0169 and 0170 represent the most likely location of where the Wiradjuri man of high standing was buried, for cultural reasons (i.e. distance and direction from the marara).

The amplitude slice-maps show mostly tree roots and metal objects, with a few rabbit burrows (). Yet, when the reflection profiles and amplitude slice-maps are considered together, individual locations of potential dhabuganha are visible within the clutter of other reflections ().

Survey Area 2

The results of the GPR survey in Survey Area 2 reveal only natural layers in the ground. The change from loamy sand to clay is evident at 0.8 m depth (8–10 ns) (). The only reflections of interest are tree roots and metal near the surface (probably scrap metal or barbed wire; ). No other features were identified in this area ().

3D modelling (photogrammetry)

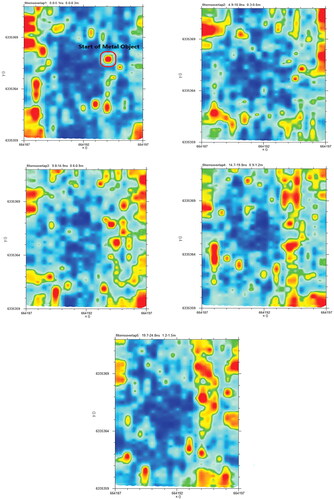

This study produced 17 3D models of culturally modified trees and dhabuganha in the two study areas. The 3D models show the marara and scarred trees at the TSR, as well as the four marara, headstone, and slab at Yuranigh’s Grave. The 3D models of the TSR carved tree, TSR fallen scarred tree, and Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4 are presented below ().

The 3D models made it possible to investigate cut marks in the muyalaang in greater detail to assess whether they were created with stone or metal tools. The cut marks on the muyalaang on Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 1 (live standing tree) are sharply defined. This suggests the cut marks were made using a steel axe or hatchet (cf. Cole et al. Citation2020:Table 2). The muyalaang on Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4 (dead standing tree) is more decayed and worn from exposure to the elements. This means it is unclear if a stone or steel tool was used to make the cut marks. The muyalaang on the TSR carved tree (live standing tree) is more worn than Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 1, but less worn than Yuranigh’s Grave Carved Tree 4. The upper cut marks in the TSR carved tree are more sharply defined, suggesting a Wiradjuri person used a steel axe or hatchet to create this muyalaang following ‘contact’ with non-Aboriginal people in the early nineteenth century.

For the Aboriginal community involved in the study, the 3D models are a digital record of Aboriginal cultural heritage with a limited lifespan, but a continuing educational resource for the Wiradjuri and broader community. The 3D models will continue to exist once the trees reach the end of their natural life cycle (usually only a few hundred years), and are no longer present in physical form. Discussions are currently underway within the Aboriginal community regarding long-term management of the digital 3D model files. A 3D model of the TSR carved tree was printed and presented to the Aboriginal community. It will be carefully stored and used by senior male Wiradjuri Elders only for teaching purposes.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that marara and dhabuganha are sacred locations of deep cultural meaning, as described above, that can only be understood when traditional cultural knowledge and Western scientific perspectives are brought together in a respectful way (Yindyamarra). Practically, marara and dhabuganha are locations where Wiradjuri men of high standing were buried. Symbolically, these locations are complex representations of Wiradjuri Lore, totems, creation stories, and ceremonial practices that form part of the cultural landscape. Importantly, we should not think of these places as individual sites, but as connected parts of Wiradjuri belief systems and cultural practices, and of the animals, plants, creeks, mountains, landscapes and associations that make up Wiradjuri Country – linking the earth and sky world.

While previous studies promote the idea of marara and dhabuganha as individual sites outside their cultural context, they are still important as a visual record of many marara and dhabuganha that are now gone (or nearing the end of their natural life cycle). These studies offer snapshots of these places at a point in time that is closer to ‘pre-contact’ times, when marara and dhabuganha would have been much more abundant and similar to their original appearance. In addition to the cultural information recorded and preserved through the interview process, the Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders involved in this study hope that the new 3D models can provide a more interactive and participatory way to understand marara for Elder-led teaching purposes as these places move closer to the end of their natural lifespan.

This study is unique in terms of its approach to investigating, recording and interpreting Aboriginal burials and culturally modified trees. While there have been many archaeological studies of Aboriginal burial locations in Australia, only a small number have used non-invasive techniques such as GPR survey (e.g. Lowe and Law Citation2022; Roberts et al. Citation2021; Sutton et al. Citation2020; Wallis et al. Citation2008). Fewer still have a 3D modelling component, or detailed interviews with Aboriginal Elders and knowledge holders to build a more developed understanding. The most comparable archaeological study is perhaps the GPR and magnetics survey of earth mounds at Mapoon, Tjungundji Country, far north Queensland (Sutton et al. Citation2013). The results of the Mapoon study reveal differences in the make-up of the mounds, which have complex layering and, in some cases, evidence for burning events, cultural objects and/or human burials (Conyers et al. Citation2019). In contrast, the dhabuganha investigated in this study are no longer present in their original form. Still, it is clear that Wiradjuri burial practices are different from those of the Tjungundji people – and of Aboriginal people in other parts of Australia (e.g. Bowler et al. Citation1970, Citation2003; Lowe et al. Citation2014; Moore et al. Citation2020; Pardoe Citation1988; Pretty Citation1977; Sutton et al. Citation2013; Stone and Cupper Citation2003; Thorne and Macumber Citation1972). This reinforces the diversity of Aboriginal symbolic expression across the Australian continent.

From the perspective of the interview participants, the results of this study are important for several reasons. First, they have provided a better understanding of locations of dhabuganha, which is important for ensuring long-term protection and management of these locations. This has also assisted with the repatriation and reburial of Ancestors who were removed from these locations and others without consent. Second, this study has incorporated traditional cultural knowledge about marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha for the first time to develop culturally informed understanding of these places. Third, this study has created a resource for the Aboriginal community, which can be used for teaching purposes, including community members who do not have family members who can teach them traditional cultural knowledge. Finally, this study has created a good opportunity for Wiradjuri Elders, knowledge holders and community to come together, and to work together.

Conclusions

Marara and dhabuganha are an important part of Country for Wiradjuri people, representing a physical link to their Ancestors and culture, which continues today. The results of this study allow marara, muyalaang and dhabuganha to be understood in new ways, and traditional cultural knowledge to be shared and preserved for future generations of Wiradjuri people. The study results also demonstrate the importance of working respectfully with Aboriginal communities – and including their voices and perspectives – to understand practical and symbolic aspects of their heritage and to share this information appropriately.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Wiradjuri people of the Central Tablelands and thank the many people who participated in this research project. This includes Cassie Jones, Jordan Smith and Phil Cranney from Central Tablelands Local Land Services; Annette Steele, Rick Ah-See and Wayne Wright from the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council; Wiradjuri Elder Aunty Shirley Kinchela, Chris Jones from Orange Aboriginal Medical Service; Tyren Dixon, Jason Edwards, Gully West, Graham Webb and Dale Carr from Orange Aboriginal Men’s Group; Ian Packer from Soilpack Services, Olivia Williams and others from Dyiramaalang Dance Group; Graham Kelly from Local Land Services; and Paul Penzo-Kajewski and Katherine Ellinghaus from La Trobe University. This research was conducted in accordance with Human Research Ethics approval HEC21356, approved by La Trobe University in 2021.

Disclosure statement

The authors do not report any potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Armstrong, B., C. Spry and L. Conyers 2021 Garra TSR Burial Site Research Project: GPR Survey Preliminary Results. Unpublished report prepared for Central Tablelands Local Land Services.

- Atalay, S. 2006 Indigenous archaeology as decolonizing practice. The American Indian Quarterly 30(3):280–310.

- Black, L. 1941 Burial Trees. Melbourne: Robertson & Mullens Ltd.

- Bowler, J.M., H. Johnston, J.M. Olley, J.R. Prescott, R.G. Roberts, W. Shawcross and N.A. Spooner 2003 New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia. Nature 421(6925):837–840.

- Bowler, J.M., R. Jones, H. Allen and A.G. Thorne 1970 Pleistocene human remains from Australia: A living site and human cremation from Lake Mungo, western New South Wales. World Archaeology 2(1):39–60.

- Buhrich, A., Å. Ferrier and G. Grimwade 2015 Attributes, preservation and management of dendroglyphs from the Wet Tropics rainforest of northeast Australia. Australian Archaeology 80(1):91–98.

- Buhrich, A. and J. Murison 2020 The Western Yalanji dendroglyph: The life and death of an Aboriginal carved tree. Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 7(4):255–271.

- Cole, N., L.A. Wallis, H. Burke, B. Barker and Rinyirru Aboriginal Corporation 2020 ‘On the brink of a fever stricken swamp’: Culturally modified trees and land-people relationships at the Lower Laura (Boralga) Native Mounted Police camp, Cape York Peninsula. Australian Archaeology 86(1):21–36.

- Conyers, L.B. 2013 Interpreting Ground-Penetrating Radar for Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Conyers, L.B., E.J. St Pierre, M-J. Sutton and C. Walker 2019 Integration of GPR and magnetics to study the interior features and history of earth mounds, Mapoon, Queensland, Australia. Archaeological Prospection 26(1):3–12.

- Dardengo, M., A. Roberts and M. Morrison 2019 An archaeological investigation of local Aboriginal responses to European colonisation in the South Australian Riverland via an assessment of culturally modified trees. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 43:33–70.

- Etheridge Jnr, R. 1918 The dendroglyphs or ‘carved trees’ of New South Wales. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of New South Wales. Ethnological Series 3. Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer.

- Evans, G.W. 1820 The Grave of a Native of Australia [Engraving]. London: John Murray.

- Fitzpatrick, J.C.L. 1913 The Good Old Days of Molong. Parramatta, NSW: The Cumberland Argus Ltd, Printers, Church & Macquarie Sts.

- Glasson, W.R. 1949 Yuranigh. Queensland Geographical Journal 54:53–65.

- Griffin, D. and A. Cooper 2019 ‘Scarred for Life’: A preliminary comparative functional analysis of culturally modified trees at Kromelak (Outlet Creek), Ross Lake and Northern Guru (Lake Hindmarsh) on Wotjobaluk Country, western Victoria, Australia. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 43:94–133.

- Howitt, A.W. 1904 The Native Tribes of South-East Australia. London: Macmillan.

- Jackson, G. and C. Smith 2006 Decolonizing Indigenous archaeology: Developments from Down Under. The American Indian Quarterly 30(3):311–349.

- Krynen, J.P., E.J. Morgan, O.L. Raymond, M.M. Scott and A.Y.E. Warren 1997 Molong 1:100 000 Geological Sheet 8631. 1st ed. Sydney: Geological Survey of New South Wales & Canberra: Geoscience Australia.

- Leaman, T.M. and D.W. Hamacher 2019 Baiami and the emu chase: An astronomical interpretation of a Wiradjuri dreaming associated with the Burbung. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 22(2):225–237.

- Lowe, K.M. and E. Law 2022 Location of historic mass graves from the 1919 Spanish Influenza in the Aboriginal community of Cherbourg using geophysics. Queensland Archaeological Research 25:67–81.

- Lowe, K.M., L.A. Wallis, C. Pardoe, B. Marwick, C. Clarkson, T. Manne, M.A. Smith and R. Fullagar 2014 Ground‐penetrating radar and burial practices in western Arnhem Land, Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 49(3):148–157.

- McCarthy, F. 1940 The carved trees of New South Wales. The Australian Museum Magazine 7(5):161–166.

- McCarthy, F. 1945 Catalogue of the Aboriginal relics of NSW. Part III. Carved trees or dendroglyphs. Mankind 3(7):199–206.

- McNaughton, D., M.J. Morrison and C. Schill 2016 ‘My Country is like my mother …’: Respect, care, interaction and closeness as principles for undertaking cultural heritage assessments. International Journal of Heritage Studies 22(6):415–433.

- Moore, M.W., K. Westaway, J. Ross, K. Newman, Y. Perston, J. Huntley, S. Keats, Kandiwal Aboriginal Corporation and M.J. Morwood 2020 Archaeology and art in context: Excavations at the Gunu site complex, northwest Kimberley, Western Australia. PloS One 15(2):e0226628.

- Morrison, M. and E. Shepard 2013 The archaeology of culturally modified trees: Indigenous economic diversification within colonial intercultural settings in Cape York Peninsula, northeastern Australia. Journal of Field Archaeology 38(2):143–160.

- Murray, J. 1820 [2002] Journals of Two Expeditions into the Interior of New South Wales Undertaken by Order of the British Government in the Years 1817–18 Oxley, John Joseph William Molesworth (1783–1828). Sydney: University of Sydney Library.

- O'Connor, S., J. Balme, U. Frederick, B. Garstone, R. Bedford, J. Bedford, A. Rivers, A. Bedford and D. Lewis 2022 Art in the bark: Indigenous carved boab trees (Adansonia gregorii) in north-west Australia. Antiquity 96(390):1574–1591.

- Pardoe, C. 1988 The cemetery as symbol. The distribution of prehistoric Aboriginal burial grounds in southeastern Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 23(1):1–16.

- Pearce, H. 1897 Information about Australian tribes. The Australian Anthropological Journal 5:99–100.

- Pike, D. (ed.) 1967 Yuranigh (?–1850). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Volume 2. Retrieved 8 November 2022 from <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/yuranigh-2829/text4059>.

- Pogson, D.J. and J.J. Watkins (Geological Survey of New South Wales) 1998 Bathurst 1:250 000 Geological Sheet: Explanatory Notes, SI/55-8. Sydney: Department of Mineral Resources.

- Pretty, G.L. 1977 The cultural chronology of the Roonka Flat. In R.V.S. Wright (ed.), Stone Tools as Cultural Markers, pp.288–331. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Roberts, A., J. Barnard-Brown, I. Moffat, H. Burke, C. Westell and the River Murray and Mallee Aboriginal Corporation 2021 Invasion, retaliation, concealment and silences at Dead Man’s Flat, South Australia: A consideration of the historical, archaeological and geophysical evidence of frontier conflict. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 145(2):194–217.

- Ross, A., J. Prangnell and B. Coghill 2010 Archaeology, cultural landscapes, and Indigenous Knowledge in Australian cultural heritage management legislation and practice. Heritage Management 3(1):73–96.

- Smith, C., H. Burke, J. Ralph, K. Pollard, A. Gorman, C. Wilson, S. Hemming, D. Rigney, D. Wesley, M. Morrison, D. McNaughton, I. Domingo, I. Moffat, A. Roberts, J. Koolmatrie, J. Willika, B. Pamkal and G. Jackson 2019 Pursuing social justice through collaborative archaeologies in Aboriginal Australia. Archaeologies 15(3):536–569.

- Spry, C., E. Hayes, K. Allen, A. Long, L. Paton, Q. Hua, B.J. Armstrong, R. Fullagar, J. Webb, P. Penzo-Kajewski, L. Bordes and Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council 2020 Wala-gaay Guwingal: A twentieth century Aboriginal culturally modified tree with an embedded stone tool. Australian Archaeology 86(1):3–20.

- Sutton, M-J., and L.B. Conyers with contributions from, A. Day, H. Flinders, F. Luff, S. Madua, Z. De Jersey, S. De Jersey, R. Savo and W. Busch 2013 Understanding cultural history using ground-penetrating radar mapping of unmarked graves in the Mapoon Mission Cemetery, western Cape York, Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17(4):782–805.

- Sutton, M-J., L.B. Conyers, S. Pearce, E. St. Pierre and D.N. Pitt 2020 Creating and renewing identity and value through the use of non‐invasive archaeological methods: Mapoon unmarked graves, potential burial mounds and cemeteries project, western Cape York peninsula, Queensland. Archaeology in Oceania 55(2):118–128.

- Sutton, M-J., E. St Pierre, P. Mitchell, L. Conyers and S. Pearce 2021 A Grave Responsibility to Honour Our Ancestors: A National Guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities to Identify and Protect Unmarked Graves and Cemeteries. Unpublished report prepared for Tweed Byron LALC.

- Stone, T. and M.L. Cupper 2003 Last Glacial Maximum ages for robust humans at Kow Swamp, southern Australia. Journal of Human Evolution 45(2):99–111.

- Thorne, A.G. and P.G. Macumber 1972 Discoveries of late Pleistocene man at Kow Swamp, Australia. Nature 238(5363):316–319.

- Tutchener, D., D. Claudie and M. Morrison 2019 Results of archaeological surveys of the Pianamu Cultural Landscape, central Cape York Peninsula, 2014–2016. Queensland Archaeological Research 22:39–58.

- Wallis, L., I. Moffat, G. Trevorrow and T. Massey 2008 Locating places for repatriated burial: A case study from Ngarrindjeri ruwe, South Australia. Antiquity 82(317):750–760.

- Webb, J.A. 2017 Denudation history of the southeastern highlands of Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 64(7):841–850.

- Webber, H. and A. Burns 2004 Seeing the forest through the trees – Aboriginal scarred trees in Barrabool Flora and Fauna Reserve. The Artefact 27:35–45.