Abstract

The article deals with a small bulla of unknown provenance that was purchased some forty years ago in the Bedouin market of Beʾer Sheva. The bulla was stamped with a seal depicting a roaring lion, above which the letters (LSM[Ꜥ]) were straightforwardly identified; it closely resembles the famous ‘ShemaꜤ servant of Jeroboam’ seal from Megiddo. Significantly, this unique bulla represents, to date, the first example of an ancient bulla stamped with a scaled-down authentic seal of a known master-seal of the Iron Age in Israel. The authenticity of the bulla was confirmed by meticulous laboratory tests, verifying both that it is genuine and that its date coincides with that of the ShemaꜤ seal from Megiddo.

Introduction

The 1904 discovery of the seal of ‘ShemaꜤ servant of Jeroboam’ in Gottlieb Schumacher’s excavation at Tell el-Mutesselim/Tel Megiddo generated much interest. This is the largest (26.5 × 36.5 × 17 mm) and most magnificent seal among the Hebrew seals known to date. Its owner, ShemaꜤ (‘servant’, lit. ‘slave’) was a high-ranking official in the court of King Jeroboam II of Israel (784–748 BCE). The jasper stone seal was unperforated and was apparently set in a metal frame attached to a ring. Following its discovery, Schumacher sent the seal as a present to Sultan Abdul Hamid; it subsequently disappeared from his collection in Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and its whereabouts remain unknown. Fortunately, before sending it to the Sultan, Schumacher had prepared plaster casts of the seal and from them, a bronze replica (). These and the photographs remained the sole evidence for this outstanding seal (for the circumstances of the seal’s disappearance, its photographs, and plaster casts, as well as the presumed palm tree (?) fronting the lion and an Ꜥnḫ behind it, see Watzinger Citation1929: 64; Van der Veen Citation2020: 28–33).

Fig. 1: Copy of the bronze cast of the seal stamp ‘(belonging) to ShemaꜤ servant of Jeroboam’ from Schumacher’s excavation in Megiddo (photo by Michael Magen, the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

The seal of ‘ShemaꜤ servant of Jeroboam’ was discovered in the general area of the southern gatehouse (Building 1567) of Strata VA–IVB at Megiddo. Although the precise stratigraphic context of the seal is still under debate, it seems likely that it was found in the mudbrick debris that accumulated above the ruined gatehouse and that it was originally in administrative use in the fortified compound of Stratum IVA. The latter came to a violent end probably during the conquest of Tiglath-pileser III King of Assyria in 732 BCE (Finkelstein and Sass Citation2013: 152; Ussishkin Citation2018: 416–417; cf. Franklin Citation2006: 98–107). Nowadays it is commonly accepted that the seal dates to the reign of Jeroboam II (784–748 BCE), a dating supported by palaeographic and iconographic considerations (Ussishkin Citation2018: 40). Judging from the high quality of the jasper seal’s material and its superb glyptic workmanship, its owner, ShemaꜤ, was a senior official in the administration of King Jeroboam II (Avigad and Sass Citation1997: 49–50, No. 2; Ussishkin Citation2018: 417–418). Indeed, as suggested in the past, the lion on the ShemaꜤ seal is very similar in outline, posture and anatomical details to the motif of the roaring lion in contemporaneous Assyrian monumental art (Madhloom Citation1970: 100–105; Albenda Citation1974: 8–10, Figs. 17–19; and recently Van der Veen Citation2020: 37–50 with earlier references). Although most available seals of this type are unprovenanced, a few examples were encountered in dateable contexts, e.g., the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad (Dur-Sharrukin), Hazor VA and the Western Wall Plaza in Jerusalem (in a fill of the Roman period). All of them date to the second half of the 8th century BCE.Footnote1 In most of the seals with the roaring lion motif, the lion is accompanied by Egyptian or North Levantine motifs like the Ꜥnḫ or the winged scarab, but in some, the roaring lion is the central or sole motif. The symbolism of a lone lion in the iconography of the Ancient Near East has been widely discussed. In Assyrian art, for example, the lion represented the goddess Ishtar (Ornan et al. Citation2012: 6*–8*). Accordingly, some scholars assumed that in Iron II seals from the the Southrn Levant, the lion is likewise a divine attribute symbolising YHWH, the god of Israel. This assumption, if accepted, implies that the roaring lion in the ShemaꜤ seal from Megiddo—as in the case of the seals and seal impressions from Hazor, Jerusalem and Mizpeh/Tell en-Naṣbeh—symbolises YHWH or is one of the Yahwistic symbols in Israel and Judah (Sass Citation1993: 221; Ornan et al. Citation2012: 6*–8* with discussion and references; Ornan and Lipschits Citation2020).

The bulla

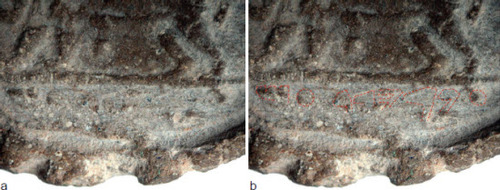

In the early 1980s, Prof. Yigal Ronen of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev purchased in the Bedouin market of Beʾer Sheva a small oval lump of clay stamped with an epigraphic stamp, depicting a roaring lion standing on its four legs (). The provenance of the bulla is unknown, and the seller did not provide any other relevant information. Nevertheless, the Hebrew letters ]ע[משל above the lion were readily legible even to the naked eye, and its resemblance to the famous ShemaꜤ seal from Megiddo became obvious. Ronen paid the paltry sum of ten shekels for the clay lump, assuming that it might be a modern imitation of the lion on the then current half-shekel coin (issued in 1980).

Fig. 2: The bulla, ‘(belonging) to ShemaꜤ servant of Jeroboam’; a) face; b) back (photos by Y. Goren)

As the bulla is unprovenanced and was acquired in the open market, its authenticity was, of course, suspect. Since the 1967 Six-Day War, many Hebrew bullae—including modern forgeries—have found their way into the antiquities market and ended up in various collections, even museums (Goren and Arie Citation2014). Even though the bulla was purchased in a popular market for an insignificant price, the authors were determined to subject the bulla to a series of meticulous laboratory examinations, detailed below. It should be emphasised that the scientific analyses for authentication of the bulla carried out in the laboratories were totally unknown when this bulla had been acquired and even when it was first brought to our attention in 2010.

The oval bulla is 23.4 × 19.3 mm at its maximal points and the stamped area is ca. 15 × 20 mm. The stamped area is ca. 4 mm thick and ca. 6 mm thick on the raised fringes. The bulla is coated with greyish-white patina on the stamped surface, as well as on its fringes and the back, especially in the dents. The patina evidently accumulated over the years since its production in antiquity. As indicated by the patina-free spaces, the bulla is made of dark-brown clay, including ‘salt and pepper-like’ dark and light grits. The impression of the seal did not cover the entire surface of the bulla, and consequently, while the clay was still soft (i.e., leather-hard), its fringes were pushed up and cracked in the process of hardening. This phenomenon has been observed in other Iron Age bullae, as well as in the course of modern simulations (Arie, Goren and Samet Citation2011; Goren, Gurwin and Arie Citation2014). The bulla’s surface is flat, and its convex back is marked by the delicate impression of the textile to which the bulla had been attached (see more below). Typologically, our bulla belongs to the class known as ‘fiscal bullae’—namely, threadless bullae that were apparently used by the Judahite administration during the late 8th and the 7th centuries BCE to seal shipments of tax in kind (Avigad Citation1990). This is in contrast to the majority of bullae current from the 8th century BCE to the end of the Iron Age that were used for sealing judicial documents, their backs bearing impressions of papyri and threads, as well as impressions of threads embedded in the thickness of the bullae (Arie, Goren and Samet Citation2011; Goren, Gurwin and Arie Citation2014).

The seal impression

The impression on the bulla was examined and photographed under a stereoscopic microscope (Zeiss Stemi 2000-C), in frontal, backlit and ultraviolet light, at magnifications ranging from ×6 to ×100. These examinations aided in the epigraphic analysis and made it possible to view details that a two-dimensional examination in the magnifier and in less direct lighting does not reveal.

The seal impression on the bulla is very damaged, mostly in its lower part, below the base line of the roaring lion. While stamping the seal on the bulla, inconstant pressure was applied, probably due to the object and material to which the bulla was affixed (see below). The excess pressure on the lower part of the bulla, especially on the right side, distorted the inscription. While the inscription ]ע[משל,‘to ShemaꜤ’, above the lion is clearly read—except for the ע that left only a ‘shadow’ on the surface—the inscription םעברי דבע, ‘Servant of Jeroboam’, under the lion is blurred. It can be detected, however, when the inscription is examined under a microscope ().

Fig. 3: a) View of the lower panel under stereomicroscope; b) the reconstructed reading (photo by Y. Goren)

The distortion of the inscription discouraged us from attempting to accurately reproduce the letters or draw them. Any such forced attempt could ‘fake’ the letters. Therefore, notwithstanding the tracing of the letters (), there is no point in a palaeographic analysis of the inscription. Below we describe the remnants of the letters and leave it to the reader to complete their picture. The distinct resemblance of the bulla sealing to the seal from Megiddo guided us in restoring the bottom line of the inscription. One should bear in mind, however, that only a copy made from another copy of the seal from Megiddo was available to us, but not the seal itself. The copper cast was made from a plaster impression of the seal, and when comparing the bronze cast to the photograph of the seal it seems that the bronze cast is ‘improved’ and is not entirely reliable (Van der Veen Citation2020: 29).

עמשל—‘(belonging) to ŠemaꜤ’. The word עמשל is written in large letters, as on the seal from Megiddo. The ל is angular, similar to the ל on the Megiddo seal, but is positioned slightly higher than the lion’s tail button. The clogged ש is smaller than the ש of the Megiddo seal and is placed higher than the ל in the Megiddo seal. The zigzag head of the מ lost its angularity at the bottom, due to the thickening of the lines. Its thick leg leans slightly backward, to the right, instead of turning to the left in the direction of writing, as in the Megiddo seal. The ע was clogged, probably because of the thick stylus used by the engraver, and instead of a circle, a hole was formed and was filled with clay that left a ‘shadow’. The letters of the bottom line ‘hang’ from the base line under the lion. This line facilitates the distinction between the writing line and the defects in the seal impression close to the imprint of the seal frame ().

דבע—‘servant’, lit. ‘slave’. The partially clogged ע stands at the same level of the head of the following ב. The head of the ב is damaged. Due to a defect in the clay, it is difficult to determine if the foot of the ב is bent as in the seal from Megiddo, but we assume that it is. The right leg of the triangle forming the head of the letter ב leans back slightly to the right, unlike the ב in the Megiddo seal. The ד is a legless triangle, like the ד in the seal from Megiddo.

םעברי—Of the י only the head is preserved, but its two arms appear to merge together. The thigh and calf of the leg are lost. The triangular heads of the ר and the ב are preserved, but not the legs. The ע is noticeable. From the head of the מ the upper part of the foot is visible, as well as the ‘teeth’ of its head. Its left ‘tooth’ touches the frame’s imprint of the seal.

The imprint of the textile on the back of the bulla

Recent simulation tests have shown that stamping a bulla must be performed while the clay is still ‘leather-hard’ (Arie, Goren and Samet Citation2011; Goren, Gurwin and Arie Citation2014). Otherwise, the seal would stick to the clay and when removed, would leave a blurred stamp impression. Thus, in all authentic bullae (including this one), cracks are visible at the raised margins of the seal impression. When a piece of clay is affixed to elastic materials (such as textile or papyrus) and is fully dried out, the clay will be separated from the substrate, because the water in it has evaporated entirely. We assume that the stamp impression on the bulla was made as follows: the small lump of clay was laid on a piece of fine linen placed in the owner’s palm, in order to enable a clear impression and subsequent easy removal of the bulla from the linen. In the case of stamping bullae on a papyrus, two lumps of clay were used, one on top of the other, with the thread binding the papyrus becoming embedded between the two lumps of clay (Arie, Goren and Samet Citation2011: illustration 2; pace Avigad Citation1986).

A textile imprint is visible on the concave back of the bulla (b). The impression provides valuable information on the identification of the textile, as well as on certain technological and functional aspects. This is a linen textile, spun to the left (S-spun), medium spinning strength. The thickness of the yarn is similar in both directions (the warp and the weft), with 15 threads per cm in each direction, the warp and the weft woven in a simple plain weave balanced tabby technique, with medium density. In this technique, each weft thread goes above and below the warp thread, and vice versa. The identification of the textile is determined by the texture of its fibres. Thus, the fibres under discussion are smooth, implying that the textile is linen (unlike curly wool fibres) (Sukenik and Shamir Citation2018). The textile imprint on our bulla indicates that it was not made of the dense and high-quality weaving typical of Egyptian textiles (Hall Citation1986: 238) and that the threads are not spliced as in Egypt (Gleba and Harris Citation2017). Hence, the linen textile was a local product, probably woven near the growing areas of flax, such as the Jordan Valley or the Beth-Shean Valley (Mazar Citation2019; Citation2020; Shamir Citation1996: 142; 2006). Linen was very common in the textile industry of the ancient world, including in the Southern Levant, and was used for clothes and sacks, among other things (Hall Citation1986: 238). Remains of linen textiles resembling the imprints on our bulla were recorded in various Iron II sites, e.g., Kuntillet ꜤAjrud, Kadesh Barnea, Tel Miqne/Ekron, Megiddo and Beth-Shean (Sheffer and Tidhar Citation2012; Shamir Citation2007; Citation2008; Citation2009).

The petrographic study and isotopic tests (see below) suggest a possible origin of the bulla in northern Israel, where the linen was probably manufactured as well. The analysis of clusters of loom weights and spindles shows that during the Iron Age, the Beth-Shean area was a centre of linen production. Thus, for example, excavations at Tell al-Hama (10th-century BCE strata) uncovered a spindle with linen threads still wrapped on it, along with no less than 161 loom weights, 39 spindle whorls and 16 spindles (Cahill, Lipton and Terler 1988; Cahill, Lipton and Lipowitz 1989: 36; Shamir Citation1996: 142). Evidence for intensive linen-weaving activity and specialisation in textile production, including 172 loom weights, was recorded at Tel ꜤAmal in the 10th–8th centuries BCE (Shamir Citation2013). At Beth-Shean, 109 loom weights were discovered in an 8th-century BCE context (Shamir Citation2006), and Tel Reḥov yielded 1,234 loom weights from a late Iron I to Iron IIB context (Mazar Citation2019; Citation2020). The ratio of loom weights versus the size of the above sites indicates that they served as textile-manufacturing centres (Shamir Citation2009; see also Mazar Citation2020: 126).

Laborator y research

The purchase of our bulla in the open market raises the question of its authenticity and possible place of origin. Over the years, numerous bullae attributed to the First Temple period have surfaced in the antiquities market, some of which, upon laboratory examination, proved to have been manufactured fairly recently (Goren and Arie Citation2014). The bulla under discussion was subjected to meticulous laboratory tests using modern scientific methods, still unknown at the time the bulla was purchased and some even unknown at the time when it was first handed over to the authors for study in 2010.

Petrographic research

Petrographic analyses of ancient ceramic products are regularly performed to examine the mineralogical composition of the material, to define the lithology from which the raw materials were derived and to determine the baking temperatures of clay, as well as other technological and environmental characteristics (Goren Citation1996; Quinn Citation2013). The tiny specimens for the microscopic slide were removed from areas on the margins of the bulla that did not touch the imprint of the seal, or the textile imprints on the back, using methods developed for sampling cuneiform tablets and bullae (Goren, Finkelstein and Naʾaman 2004: 11–12; Goren, Gurwin and Arie Citation2014).

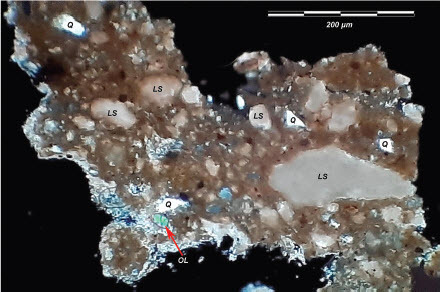

The petrographic examination under a polarising microscope (Motic BA 300Pol) shows that the bulla was made of rendzina soil. The clay is rich in limestone particles, light-opaque minerals (probably iron oxides) and a certain amount of silt containing quartz and other minerals, such as feldspar, zircon and olivine (). The limestone particles gradually change to a sand-grain size of about 0.5 mm. Although the samples retrieved from the bulla for petrographic analysis were tiny and therefore do not fully represent the variety of grits in the clay, we did not find any modern added component in the limestone. It is clearly the natural part of the material used to manufacture the bulla; nothing modern was added later to the clay (Goren et al. Citation2005). Our observations indicate that the material used to make the bulla originated from an environment characterised by limestone and basalt rocks. Such environments are best represented in the Galilee and Golan Heights and are hardly known in the Central Highlands. The Eastern Galilee and the Jezreel Valley, are the most likely source for the clay of our bulla. We emphasise, however, that it is impossible to determine categorically that the bulla originated from Megiddo, although this is a reasonable probability.

Fig. 5: Specimen from the bulla viewed under a petrographic polarising microscope (the black area marks the background); scale: 0.2 mm long; the brown silt includes limestone particles with calcite characteristic of rendzina soil; larger particles are of sand and silt containing limestone (LS), quartz (Q) and olivine (OL)

The petrographic analysis shows that the bulla was baked at a high temperature (). As a result of the partial destruction of the crystalline structure, the matrix lost its optical properties. The phenomenon of baking bullae has been observed in many cases in the past (Arie, Goren and Samet Citation2011; Gadot, Goren and Lipschits Citation2013; Goren and Gurwin Citation2013; Citation2015; Gurwin and Arie 2014; Ornan, Wexler-Bdolah and Sass 2019). The baking of bullae was probably intended to preserve them as a reference, as they functioned as a signature and seal of official authority in the event of need at a later date. Presumably, the baking of ‘fiscal’ bullae was a common administrative procedure.

Scanning Electron Microscope

Tests under the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) equipped with X-ray dispersion spectroscopy (EDS) and secondary electron (SE) detectors and backscattered electrons (BSE) were performed on the bulla (Quanta 200 FEI microscope). These tests had several functions: they supplemented information on the composition of the clays and grits of the bulla; they allow imaging of specific areas in the seal impression; they detect foreign substances (such as adhesives) that may betray modern treatment of the bulla or its patina coating; and they determine to what extent the latter was formed under natural processes. In short, the SEM tests are intended to provide complementary data on the origin of the bulla’s materials and to serve as a primary test for the question of its antiquity.

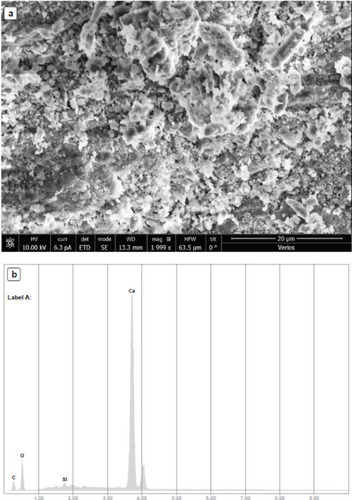

The SEM test indicated the growth of a calcitic (CaCO ) patina over the surface of the bulla (). It is generally assumed that the patination process is slow and that original patina may therefore be used as evidence of the object’s antiquity. However, the voluminous literature of the past five decades concerning the accumulation, weathering and dating of patina on archaeological items (such as rock art) argues that its presence on archaeological materials cannot be used a priori as an indicator of the antiquity or authenticity of an object because a patina-like—or even a real patina—coating may be artificially fabricated. While it can always be assumed that a real patina formed on an object is younger than it is, there are certain difficulties in assessing its age. For example, climatic factors and pH have a significant effect and may accelerate, delay, or prevent entirely the formation of patina (Bednarik Citation1979; Ayalon, Bar-Matthews and Goren Citation2014).

Fig. 6: Calcitic patina on the surface of the bulla’s impression examined under the SEM; a) patina formed by the accumulation of calcite crystals (scale: 0.2 mm long; b) chemical analysis of the material (a), using X-ray dispersion spectroscopy (EDS), indicating clean composition of calcite (CaCO3)

Our tests indicated the accumulation of calcite crystals over the surface of the bulla. These crystals are rhombic and are attached to the bulla’s surface separately or as aggregates. EDS analyses showed the composition of calcite and clay with no foreign compositions (), and BSE testing did not reveal any evidence of absorbed materials, such as adhesives. It follows that the calcite has accumulated in a process of undisturbed crystallisation over the bulla’s surface. We emphasise, however, that this fact in and of itself does not indicate the antiquity of the bulla, as such a process can be achieved artificially in a laboratory.

Surface scanning by Raman spectroscopy

The analytical method of Raman spectroscopy, which examines the molecular composition of materials, is widely used for non-invasive analyses of cultural heritage values, as it enables the identification of a wide range of organic and inorganic materials (Casadio, Daher and Bellot-Gurlet Citation2017). Selected areas of the bulla on the face of the seal imprint were scanned in search of foreign matter, using a Raman spectrometer (LabRam HR Evolution Horiba) in the wavelength range of 325–785 nm. Two areas were scanned: the ל in the word ]ע[משל and the lion’s back near the mane. In these areas there was no visible evidence of organic matter containing adhesives.

Isotopic analyses of the patina

The study of isotopic composition values of oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13C) in order to verify the authenticity of archaeological artefacts was first performed by authors of this article, who examined patina samples of known (and controversial) items (Ayalon, Bar- Matthews and Goren 2014; see also Bar-Matthews et al. Citation1996; Bar-Matthews, Ayalon and Kaufman Citation1997; 1998).Footnote2

Patina samples extracted from the bulla’s surface were tested for the isotopic composition of the oxygen and carbon of the carbonate. They were measured using a Gas Bench automatic sampler attached to a Delta Plus Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) at the Geological Survey of Israel. δ18O values have been calibrated against the international standard NBS-19 and are reported in the permille according to the VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) standard.

The isotopic composition of the patina from the bulla is: δ18O = -6.30‰, δ13C = -9.96‰. The δ18O value is in the expected range for the Galilee (Bar-Matthews et al. Citation2003; Ayalon et al. Citation2017). The δ13C value is a typical carbon value of the soils in an area covered with Mediterranean-type vegetation (type C3). Since the stylistic and petrographic data also point to an origin in the Galilee region, the isotopic tests indicate a calcitic patina that exhibits the normal values in terms of temperature and natural water composition that have existed in this region over the past 3,000 years.

Patina formed by artificial laboratory processes will show a significantly different isotopic composition from the above values, because of a different isotopic composition of water, an ambient temperature that does not match the regional average since the Iron Age, or the different composition of the dissolved carbonate used to create it.

Summary of laboratory tests

The laboratory tests indicate that the bulla under consideration was made from soil originating in an environment around which limestone rocks are exposed in the vicinity of basalt containing olivine grits. This corresponds generally to areas of the Lower Galilee and the Jezreel and Beth-Shean Valleys, including the region of Tel Megiddo. However, the results of the tests do not unequivocally entail that the bulla originated from this royal administrative centre. The bulla was sealed on a linen cloth when its material was in a ‘leather-hard’ state and was then baked at a temperature of ca. 750°C or slightly higher. The patina covering the bulla is calcific and crystallised directly over the material, with no adhesives or any other foreign substance. The isotopic composition of the patina indicates its formation under natural conditions in the Galilee region. Since the protocol of the laboratory tests described above, as well as the expected results, were unknown at the time of purchase of the bulla, and were not fully known even at the time when it was brought to the authors’ attention, we may conclude with a high degree of certainty that the bulla is authentic and ancient.

The significance of the bulla

The bulla under review is an important addition to the repertoire of Hebrew seals and seal impressions known to us from the First Temple period. Moreover, it is one of the few existing seal impressions from the Kingdom of Israel. Although different in size, there is a great resemblance between our bulla and the Megiddo seal, both in form and detail. It is possible that the much larger seal from Megiddo served as a model for a series of seals of this type. Of course, it is not known whether these seals were manufactured in the same workshop or in several administrative centres in the Kingdom of Israel. It is not impossible, however, that the artist who carved the seal that stamped the bulla copied the seal from Megiddo. A careful examination of the bulla’s details reveals that it is certainly not of the same artistic quality as the seal from Megiddo. While the lion figure in the seal is refined and flexible, with anatomical details, in the bulla it is frozen and coarse and lacks various details. For example, in the latter the lion’s body is narrower and shorter, the tail is not raised as high as in the seal, the legs are very thick and without muscles, the mane is schematic, and other details, such as ears, the eye socket, the fangs and the toes, are missing.

It should be noted that just as the seal of ‘ShemaꜤ the servant of Jeroboam’ is the oldest of the Hebrew royal seals known to date, the bulla is the earliest in the ‘historical’ seal impressions discovered thus far in the Southern Levant. In addition, for the first time in the history of the study of seals and bullae, we encounter a royal seal that was manufactured in different sizes. The Megiddo seal is almost twice the size of the seal that stamped the bulla. Presumably, the seal stamped on the bulla was in fact a scaled-down version of a seal of the same series that was used by a senior official in the Kingdom of Israel. Furthermore, this is the first time that we encounter an ancient imprint of a known seal—if, indeed, the seal impression is a scaled-down version of the seal from Megiddo—from Iron Age Israel. The phenomenon of an ancient seal and its imprint is extremely rare in the Ancient Near East.Footnote3 To the best of our knowledge, the only genuine seal and its impression (in fact, four impressions) are those of Tashmetum-Sharrat, wife of King Sennacherib of Assyria (Niederreiter Citation2008; Radner Citation2012).

The bulla impressed with the stamp seal of ShemaꜤ Servant of Jeroboam—which differs from the Megiddo seal—testifies that this individual had more than one seal at his disposal. Evidently, his stamp seals were not personal seals, but official seals of a high-ranking official in the state administration of Jeroboam II, King of Israel. ShemaꜤ and his subordinate officers used his seals to sign documents and shipments of goods on his behalf. The three different seals of Hezekiah King of Judah support this interpretation of several seals for the same person. Although most of Hezekiah’s bullae came from the antiquities market, the one that was subsequently found in a controlled excavation (Mazar Citation2015: 635–636) confirms the authenticity of Hezekiah’s other bullae. These bullae were not sealed with the king’s personal seal but with an official seal given to the officials acting on his behalf; compare the appointment of Joseph over the land of Egypt: ‘And Pharaoh took his ring from his hand and gave it to Joseph’ (Gen 41:11; see also Esther 3:10–11, 8:2, and more). For the multiplicity of bullae of the same official, see the three seals of Elyashiv son of ʾIshiyahu found at Arad (Aharoni Citation1981: 119–120).

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful to Prof. Yigal and Dalia Ronen for putting the bulla at their disposal for research and publication. The Ronen family kindly agreed to have the bulla officially registered with the Israel Antiquities Authority and to donate it as a gift to the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

The various scientific tests were carried out at the Microarcheology Laboratory and the characterisation laboratories of the Ilsa Katz Institute of Nanosciences, both at Ben- Gurion University of the Negev, as well as the laboratories of the Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem. Thanks are extended to Roxana Golan for assisting with the SEM tests and to Dr. Mariela Faben and Dr. Sharon Hazan for their assistance with the Raman spectroscopy tests.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shmuel Aḥituv

Shmuel Aḥituv: Department of Bible Studies, Archaeology and the Ancient Near East, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beʾer Sheva

Avner Ayalon

Avner Ayalon: The Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem; email: [email protected]

Mira Bar-Matthews

Mira Bar-Matthews: The Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem;email: [email protected]

Yuval Goren

Yuval Goren: Department of Bible Studies, Archaeology and the Ancient Near East, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beʾer Sheva; email: [email protected]

Michael Magen

Michael Magen: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; email: [email protected]

Eliezer D. Oren

Eliezer D. Oren: Department of Bible Studies, Archaeology and the Ancient Near East, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beʾer Sheva; email: [email protected]

Orit Shamir

Orit Shamir: Israel Antiquities Authority; email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Avigad Citation1992; Avigad and Sass Citation1997: 163, No. 391; Lemaire Citation1979; Citation1990; Sass Citation1993: 214, 221–222; Ornan et al. Citation2012: 6*–8*. Note that most of the seals referred to here are unprovenanced or unstratified. For an updated list of provenanced items, see Koch Citation2018.

2 The isotopic composition of oxygen in a carbonate patina is a function of the precipitation temperature and its isotopic composition in the water from which the patina has settled under terrestrial conditions. The isotopic composition of carbon (δ13C) is a function of the soil, its carbon dioxide and δ13C value of bedrock.

3 In this context we may note the scaraboid seal, made of bone, and its imprint on a bulla, both unprovenanced (Avigad and Sass Citation1997: Nos. 330, 616). Avigad and Sass (Citation1997: 229) remarked, with regard to No. 616, that this is the only example of a seal and its impression on a bulla in the entire corpus of West Semitic seals. However, Sass suspects the bulla, or the seal and the bulla, to be modern forgeries (B. Sass, email to E.D. Oren on March 28, 2015).

References

- Aharoni, Y. 1981. Arad Inscriptions. Jerusalem.

- Albenda, P. 1974. Lions on Assyrian Wall Reliefs. Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society of Columbia University 6: 1–27.

- Arie, E., Goren, Y. and Samet, I. 2011. Indelible Impression: Petrographic Analysis of Judahite Bullae. In: Finkelstein, I. and Na’aman, N., eds. The Fire Signals of Lachish: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin. Winona Lake: 1–16.

- Avigad, N. 1986. Hebrew Seals and Sealings and Their Significance for Biblical Research. In: Emerton, J.A., ed. Congress Volume Jerusalem 1986 (VT Supplement 40). Leiden: 7–16.

- Avigad, N. 1990. Two Hebrew ‘Fiscal’ Bullae. IEJ 40: 252–266.

- Avigad, N. 1992. A New Seal Depicting a Lion. Michmanim 6: 33*–36*.

- Avigad, N. and Sass, B. 1997. Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals. Jerusalem.

- Ayalon, A., Amit, R., Enzel, Y., Crouvi, O. and Harel, M. 2017. Stable Carbon and Oxygen Signatures of Pedogenic Carbonates in Arid and Extremely Arid Environments in the Levant. In: Bar-Yosef, O. and Enzel, Y., eds. Quaternary of the Levant, Environments, Climate Change, and Humans. Cambridge: 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316106754.049

- Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M. and Goren, Y. 2014. Biblical Events and Environments— Authentification of Controversial Archaeological Artifacts. In: Holland, H.D. and Turekian, K.K., eds. Treatise on Geochemistry Vol. 14: Archaeology and Anthropology (2nd ed.). Oxford: 255–270.

- Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A., Gilmore, M., Matthews, A. and Hawkesworth, C. 2003. Sea–Land Isotopic Relationships from Planktonic Foraminifera and Speleothems in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and Their Implications for Paleorainfall during Interglacial Intervals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 67: 3181–3199. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)01031-1

- Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A. and Kaufman, A. 1997. Late Quaternary Paleoclimate in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from Stable Isotope Analysis of Speleothems at Soreq Cave, Israel. Quaternary Research 47: 155–168. doi: 10.1006/qres.1997.1883

- Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A. and Kaufman, A. 1998. Middle to Late Holocene (6500 yr. Period) Paleoclimate in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from Stable Isotopic Composition of Speleothems from Soreq Cave, Israel. In: Issar, A.S. and Brown, N., eds. Water, Environment and Society in the Time of Climate Change (Water Science and Technology Library 31). Dordrecht: 203–214.

- Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A., Matthews, A., Sass, E. and Halicz, L. 1996. Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Study of the Active Water-carbonate System in a Karstic Mediterranean Cave: Implications for Paleoclimate Research in Semiarid Regions, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 60: 337–347. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00395-9

- Bednarik, R.G. 1979. The Potential of Rock Patination Analysis in Australian Archaeology (Part 1). The Artefact 4: 14–38.

- Cahill, J.M., Lipton (Lipovich), G. and Terler, D. 1988. Tell el-Hammah. IEJ 38: 191–194.

- Cahill, J.M., Terler, D. and Lipowitz, G. 1989. Tell el-Hammeh in the Tenth Century BCE. Qadmoniot 85: 33–38 (Hebrew).

- Casadio, F., Daher, C. and Bellot-Gurlet, L. 2017. Raman Spectroscopy of Cultural Heritage Materials: Overview of Applications and New Frontiers in Instrumentation, Sampling Modalities, and Data Processing. In: Mazzeo, R., ed. Analytical Chemistry for Cultural Heritage (Topics in Current Chemistry Collections). Cham: 161–211.

- Finkelstein, I. and Sass, B. 2013. The West Semitic Alphabet Inscriptions, Late Bronze to Iron IIA: Archaeological Context, Distribution and Chronology. HeBAI 2: 149–220. doi: 10.1628/219222713X13757034787838

- Franklin, N. 2006. Revealing Stratum V at Megiddo. BASOR 342: 95–111.

- Gadot, Y., Goren, Y. and Lipschits, O. 2013. A 7th Century BCE Bulla Fragment from Area D3 in the ‘City of David’/Silwan. JHS 13: 1–10.

- Gleba, M. and Harris, S. 2017. The First Plant Bast Fibre Technology: Identifying Splicing in Archaeological Textiles. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11: 2329–2346. doi: 10.1007/s12520-018-0677-8

- Goren, Y. 1996. Petrographic Study of Archaeological Artifacts and Its Application in the Archaeology of Israel. Qadmoniot 112: 107–114 (Hebrew).

- Goren, Y., Aḥituv, S., Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Dahari, U., Dayagi-Mendels, M., Demsky, A. and Levin, N. 2005. A Re-examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate from the Israel Museum. IEJ 55: 3–20.

- Goren, Y. and Arie, E. 2014. The Authenticity of the Bullae of Berekhyahu Son of Neriyahu the Scribe. BASOR 372: 147–158.

- Goren, Y., Finkelstein, I. and Na’aman, N. 2004. Inscribed in Clay: Provenance Study of the Amarna Letters and Other Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 23). Tel Aviv.

- Goren, Y. and Gurwin, S. 2013. Royal Delicacy: Material Study of Iron Age Bullae from Jerusalem. The Old Potter’s Almanac 18: 2–9.

- Goren, Y. and Gurwin, S. 2015. Microscopic and Petrographic Examinations of Bullae. In: Mazar, E., ed. The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008, Final Reports Volume I. Jerusalem: 441–452.

- Goren, Y., Gurwin, S. and Arie, E. 2014. Messages Impressed in Clay: Scientific Study of Iron Age Judahite Bullae from Jerusalem. In: Martinón-Torres, M., ed. Craft and Science: International Perspectives on Archaeological Ceramics. Doha: 143–149.

- Hall, R.M. 1986. Egyptian Textiles. London.

- Koch, I. 2018. New Light on the Glyptic Finds from Late Iron Age Jerusalem and Judah. In: Uziel, J., Gadot, Y., Zelinger, Y. and Peleg-Barkat, O., eds. New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and Its Region, Collected Papers 12. Jerusalem: 29–46 (Hebrew).

- Lemaire, A. 1979. Nouveau sceau nord-ouest semitique avec un lion rugissant. Semitica 29: 67–69.

- Lemaire, A. 1990. Trois sceaux inscits inedits avec lion rugissant. Semitica 39: 13–21.

- Madhloom, T.H. 1970. The Chronology of Neo-Assyrian Art. London.

- Mazar, A. 2019. Weaving in Iron Age Tel Reḥov and the Jordan Valley. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 7: 119–138. doi: 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.7.1.0119

- Mazar, A. 2020, Objects Related to Textile Production. In: Mazar, A. and Panitz-Cohen, N., eds. Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Vol. V: Various Objects and Natural-Science Studies (Qedem 63). Jerusalem: 81–129.

- Mazar, E. 2015. The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount 2009–2013, Final Reports Vol. 1. Jerusalem.

- Niederreiter, Z. 2008. Le rôle des symboles figurés attribués aux membres de la Cour de Sargon II: des emblèmes créés par les lettrés du palais au service de l’idéologie royale. Iraq 70: 51–86. doi: 10.1017/S0021088900000875

- Oren, E.D., Aḥituv, S., Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Goren, Y. and Shamir, O. 2021. A Bulla Impressed with a Seal of ShemaꜤ Servant of Jeroboam. Eretz-Israel 34 (Ada Yardeni Volume): 13–22 (Hebrew), 195* (English summary).

- Ornan, T. and Lipschits, O. 2020. The Lion Stamp Impressions from Judah: Typology, Distribution, Iconography, and Historical Implications. A Preliminary Report. Semitica 62: 69–91.

- Ornan, T., Weksler-Bdolah, S., Kisilevitz, S. and Sass, B. 2012. ‘The Lord Will Roar from Zion’ (Amos 1:2): The Lion as a Divine Attribute on a Jerusalem Seal and Other Hebrew Glyptic Finds from the Western Wall Plaza Excavations. ꜤAtiqot 72: 1*–13*.

- Ornan, T., Weksler-Bdolah, S. and Sass, B. 2019. A ‘Governor of the City’ Seal Impression from the Western Wall Plaza Excavations in Jerusalem. In: Geva, H., ed. Ancient Jerusalem Revealed: Archaeological Discoveries, 1998–2018. Jerusalem: 67–72.

- Quinn, P.S. 2013. Ceramic Petrography: The Interpretation of Archaeological Pottery & Related Artefacts in Thin Section. Oxford.

- Radner, K. 2012. The Seal of Tašmetum-šarrat, Sennacherib’s Queen, and Its Impressions. In: Lanfranchi, G.B., Morandi Bonacossi, D., Pappi, C. and Ponchia, S., eds. Leggo! Studies Presented to Frederick Mario Fales on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Wiesbaden: 687–698.

- Sass, B. 1993. The Pre-Exilic Hebrew Seals: Iconism and Aniconism. In: Sass, B. and Uehlinger, C., eds. Studies in the Iconography of Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals. Proceedings of a Symposium Held in Fribourg on April 17–20 1991 (OBO 125). Fribourg: 194–256.

- Shamir, O. 1996. Loom Weights and Whorls. In: Ariel, D.T. Excavations at the City of David 1978–85, Directed by Y. Shiloh, Volume IV: Various Reports (Qedem 35). Jerusalem: 135–170.

- Shamir, O. 2006. Objects Associated with the Weaving Industry (Beth Shean, Area P). In: Mazar, A., ed. Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996 Vol. I: From the Late Bronze Age IIB to the Medieval Period. Jerusalem: 474–483.

- Shamir, O. 2007. Textiles, Loom Weights and Spindle Whorls. In: Cohen, R. and Bernick- Greenberg, H., eds. Excavations at Kadesh-Barnea 1976–1982 (Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 34/1). Jerusalem: 255–268.

- Shamir, O. 2008. Loomweights and Textile Production at Tel Miqne-Ekron: A Preliminary Report. In: White Crawford, S., ed. Up to the Gates of Ekron. Jerusalem: 43–49.

- Shamir, O. 2009. A Linen Textile. In: Panitz-Cohen, N. and Mazar, A., eds. Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996 Vol. 3: The 13th–11th Century BCE Strata in Areas N and S. Jerusalem: 474–483.

- Shamir, O. 2013. Loomweights from Tell ꜤAmal. Ḥadashot Arkheologiyot—Excavations and Surveys in Israel 125: 1–8.

- Sheffer, A. and Tidhar, A. 2012. Textiles and Basketry. In: Meshel, Z. Kuntillet ꜤAjrud: An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Jerusalem: 289–312.

- Sukenik, N. and Shamir, O. 2018. Fabric Imprints on the Reverse of Bullae from the Ophel, Area A2009. In: Mazar, E. The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount 2009–2013 Final Reports Vol. II. Jerusalem: 281–288.

- Ussishkin, D. 2018. Megiddo—Armageddon: The Story of the Canaanite and Israelite City. Jerusalem.

- Van der Veen, P.G. 2020. Dating the Iron Age IIB Archaeological Horizon in Israel and Judah. A Reinvestigation of ‘Neo-Assyrian (Period)’ Sigillographic and Ceramic Chronological Markers from the 8th and 7th Centuries B.C (ÄAT 98). Münster.

- Watzinger, C. 1929. Tell el-Mutesellim, II. Die Funde. Leipzig.