Abstract

The 2005–2008 excavations conducted by Eilat Mazar in Area G at the Southeastern Hill (‘the Summit of the City of David’) included stratified dump layers on the eastern slope. Reevaluation of the pottery uncovered in the three layers of the dump designated by Mazar as Babylonian Stratum 9/10 show that it consisted mainly of Iron IIC types with a few later types and that while some of the new types became popular during the Early Persian period, others either did not become common or did not continue. This, then, is a transitional assemblage, representing the 6th century BCE, with Iron Age types appearing alongside new variants. About a quarter of the bowls recovered from Stratum 9/10 are ‘non-typical’ for Iron IIC types but are not typically Persian either. We therefore suggest that they be identified as ‘Babylonian types’.

Introduction

For the past few decades, there has been an ongoing scholarly debate regarding the nature of the settlement of Jerusalem in the Babylonian period. It has long been assumed that the city was completely abandoned following the 586 BCE Babylonian destruction and was only rebuilt in the late 6th century BCE, during the early Achaemenid period. This scholarly view considers the land to have been left ‘empty’, with most of the population exiled to Babylon. The ensuing paradigm considers there to have been a cultural gap between the Iron Age and the Persian period, a gap that one would expect to be evident in the material culture. Indeed, the few decades of the Babylonian period were not discussed in the literature as a period in its own right, and scholars tended to gloss over this period, considering it either the concluding chapter of the Iron Age or the opening chapter of the Persian period.Footnote1

In recent decades, various scholars have argued for an alternative view, pointing to evidence that occupation either continued uninterrupted or else was renewed in Jerusalem after a hiatus, still within the Babylonian period. Many archaeologists still perceive the years between 586–539 BCE as a period of a genuine cultural gap in the Southern Levant,Footnote2 but the premise that a demographic and material-culture gap existed throughout the 6th century BCE is too sweeping a generalisation. It was criticised by Barkay (Citation1993; Citation1998) three decades ago,Footnote3 and Lipschits (Citation2005: 188–191) demonstrated the extent to which the dating of the destruction layers in Judahite sites to ca. 587/6 BCE was influenced by biblical and historical, rather than archaeological, considerations. This bias in the research has led to a lack of attention to the possibility of demographic continuity in the hinterland of Jerusalem, even after the city’s destruction.Footnote4

This article aims to present the evidence for continued occupation in Jerusalem throughout the Babylonian period, through a case study of the ceramic assemblage found in Eilat Mazar’s excavation on the Southeastern Hill. I present the typology of vessels uncovered by Mazar, comparing them to additional excavated assemblages unearthed in Jerusalem and its environs. This comparative study on the one hand characterises the ceramic assemblage of the Babylonian period as distinct from the preceding and subsequent periods, while on the other hand highlighting the continuity in pottery production from the late Iron Age through the Early Persian period in Jerusalem.

History of Research

It is very difficult to find comparable Babylonian strata in order to draw parallels. Most stratified sites in this region contain either late Iron IIC or Early Persian strata, the latter largely characterised by fills—mainly because from 586 BCE until the Hasmonaean period there is one long sequence of some 400 years with no ‘anchor points’ of well dated and documented destructions. As already demonstrated by Lipschits (Citation2005: 192–206), researchers, unable to isolate the Babylonian stratum from the preceding or subsequent stratum, designated assemblages that contained Iron Age and Persian material as ‘mixed’ or as ‘Persian-period’ (Franken Citation2005: 65, 93).Footnote5 Although the similarity between the Iron Age and Persian pottery was noted by researchers,Footnote6 the transitional types that constituted the ‘link’ between the two periods could not be isolated.

Stern (Citation2000; Citation2001: 322–324) and other scholars (e.g., Faust Citation2007; Citation2011; Citation2012; De Groot Citation2001: 79, De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg Citation2012: 174–175; Eisenberg and De Groot: 2006: 130) did not acknowledge the Babylonian period as a distinct period, and they have claimed that in the current state of research, it is not possible to identify a Babylonian layer due to its short lifespan, and that any attempt to present an assemblage of Babylonian pottery is invalid as it is based on assemblages of pits, burial caves and fills, rather than from sealed floors. Barkay (Citation1993), conversely, claimed that the determination of the end of the Iron Age was influenced by the historical event of the destruction of the Temple and not by the archaeological evidence. He points to a cultural stage during the 6th century BCE in which burial caves, arrowheads, glyptic finds and even unique pottery types can be identified. Zorn (Citation1993; Citation2003: 416) examined the few Babylonian finds from Tell en-Naṣbeh and concluded that our knowledge on the material culture of the Babylonian period in the Southern Levant, and especially in Judah, is limited. In contrast to proponents of the ‘Empty Land’ and ‘Babylonian Gap’ theory, Lipschits (Citation2011: 81–85) suggested that the presence of certain finds points to the existence of a distinct Babylonian period. These finds include the results of the renewed excavations at Ramat Raḥel, the perception that the 6th-century BCE lion-stamped jar handles were part of a general system of stamped jars that continued from the Iron Age uninterrupted until the Early Hellenistic period, and continuity in the rural settlements to the north and south of Jerusalem.The renewed excavations at Ramat Raḥel, conducted by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition between 2005 and 2010, have demonstrated that a palatial complex built during the Iron IIC was not destroyed in 586 BCE, but continued to exist at least until the end of the Persian period (Lipschits, Gadot and Freud Citation2016; Lipschits, Gadot and Oeming Citation2020: 476–483). The pottery assemblages from Building Phases I–III (Freud Citation2018; Citation2021; forthcoming), especially the Babylonian-Persian Pit and the stamped storage-jar handles found along with them (Lipschits et al. Citation2021; Lipschits and Vanderhooft Citation2011; Lipschits Citation2021), provide a stratigraphic division between the early part of the Iron IIC and the later part of this period, as well as between the late Iron IIC and the Early Persian period. This makes Ramat Raḥel the most important site for the differentiation of pottery types both within the Iron IIC and between the end of the Iron IIC to the 6th/beginning of the 5th centuries BCE. The detailed typological study of pottery from Ramat Raḥel and other rural sites in Jerusalem’s environs, combined with the study of processes of change and continuity in pottery production,Footnote7 make it possible to understand the changes in pottery production that took place during this short period. This enabled the isolation and study of pottery types that may serve as chronological markers of this period (Freud Citation2018)—and, indeed, such types were uncovered in Stratum 9/10 at the summit of the City of David.

Evidence for activity in the Babylonian and Persian periods in the City of David, found in Mazar’s stratified fills and in Area E of Shiloh’s excavations (Zuckerman Citation2012), was also uncovered on the western side of the slope in the GivꜤati Parking Lot excavations:

Ben-Ami (Citation2013: 4, 11–17, Pls. 2.4–2.6) assigns Strata XI–IX to the 7th century BCE. Although the architectural remains uncovered are very scanty and were retrieved from a small area, a close examination of the pottery suggests that Phases XIA, X and IX should be dated to the 586 BCE destruction, to the 6th century BCE and to the beginning of the Persian period respectively, rather than to the 7th century BCE alone (see also Freud Citation2018: 252–254; 2019: 133–134).Footnote8

Stratified layers similar to those excavated by Mazar and meagre settlement above the monumental Iron IIC Building 100 were exposed recently in the GivꜤati Parking Lot excavations, directed by Gadot and Shalev (Shalev et al. Citation2019: 60–62, Figs. 8–9; Shalev et al. Citation2020; and personal communication). A study of the nature of the destruction of Building 100 at the end of the Iron Age, in comparison to destructions of other contemporary buildings, excavated in the city (Shalom et al. Citation2019), shows that the Babylonian destruction was not total and differed in the various parts of the city. Hence, it is possible that parts of the city were left standing. This might account for the presence of the stratified fills uncovered in Kenyon’s and Mazar’s excavations—fills that offer evidence that life continued in the city even after the Babylonian destruction.

Mazar’s excavations at the Summit of the City of David

The 2005–2008 excavations conducted by Eilat Mazar in Area G at the Summit of the City of David included the stratified dumps under the northern tower, which abutted the Stepped Stone Structure and the overlying stone building (Mazar Citation2015: 13–17, 25). Mazar assigned the lower part of the fill to Stratum 10 (consisting of five layers, 10-5 to 10-1, ), which contained only Iron IIC pottery (Mazar Citation2015: 243; Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015). The upper part of the fill was assigned to Stratum 9 (consisting of seven layers, 9-8 to 9-2), which contained mainly pottery from the Early Persian period (Shalev Citation2015). Mazar (Citation2015: 25, 41–45) called the 1 m thick fill sealed between Strata 10 and 9 ‘Babylonian Stratum 9/10’, in order to maintain consistency with Shiloh’s nomenclature. The pottery that emerged from this stratum (which consisted of three layers: 9/10-3, 9/10-2 and 9/10-1) is the subject of the present contribution.Footnote9

Table 1: Eilat Mazar’s strata and layers at the Summit of the City of David (after Mazar 2015: 17; Shalev 2015; Yezerski and Mazar 2015)

Most of the assemblage consists of small sherds. The typology was largely formed on the basis of rims. Parallels were initially drawn from the pottery of the stratified layers of the Iron Age and the Early Persian period below and above this stratum, in an effort to identify the character of the assemblage and to determine its relationship to the fills below and above it. Further parallels were then drawn from well-dated nearby sites—Strata 10–9 in the City of David Area E (De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg Citation2012; Zuckerman Citation2012), Ramat Raḥel (Aharoni Citation1962; Citation1964; Freud Citation2016a; Citation2021; forthcoming) and En-Gedi Strata V–IV (Yezerski Citation2007; Stern Citation2007)—and from other sites where necessary.Footnote10

Potter y types of Stratum 9/10

The same pottery types appear in all three layers of this stratum—9/10-1, 9/10-2 and 9/10-3; thus, the typological discussion below does not distinguish between them, except when otherwise stated. The vessels are arranged in the figures from small to large and from open to closed vessels. Bowls ca. 15 cm in diameter are referred to as ‘small bowls’; bowls 20–25 cm in diameter are called ‘medium-sized bowls’; and bowls with a diameter of 25–30 cm or larger are referred to as ‘large bowls’.

Bowls

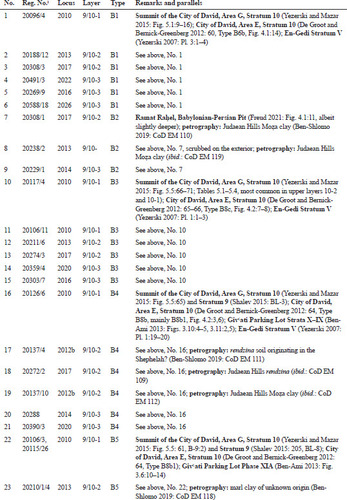

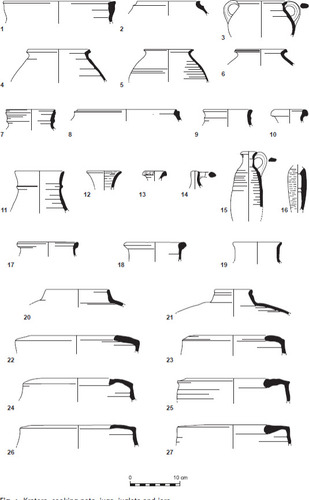

B1: Flat slipped and burnished bowl (:1–6)

This is a flat, open small bowl, made of reddish-brown clay, generally with red slip and burnish on the interior or on both the interior and exterior. The rim generally tapers downward or else is unshaped. This is a very common Iron IIC type.

Fig. 1: Bowls

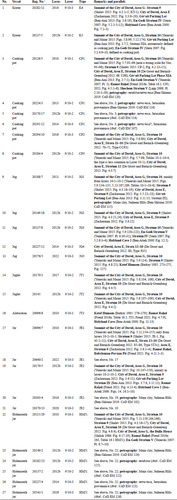

i The vessels presented here appear in the Levantine Ceramics Project database (levantineceramics.org). To go to the entry, click on the registration number in this table or search the database according to the vessel registration number.

B2: Flat bowl (:7–9)

This flat bowl is small or medium-sized, made of light brown–beige clay, and has an unshaped rim. Its surface is scrubbed or smoothed. In contrast to Type B1, it has no external treatment, such as slip, wash, or burnish.

B3: Small delicate bowl (:10–15)

This bowl type is made of thin well-levigated clay, and is highly fired (metallic ware). Most of these bowls have an outfolded rim and a small disk base; they are red-slipped or washed and are burnished on the interior and exterior. Although :13 has a small ledge rim, it is assigned to this type on the basis of the thinness of its wall and its metallic ware. This type is dated to the second half of the Iron IIC. The relatively large number of vessels uncovered in the assemblage is exceptional.

B4: Small open bowl with outfolded rim (:16–21)

The rounded wall of this bowl type is turned outward in the upper part, and the rim turns upward. The outfolded rim is tightly pressed to the wall. Made of reddish-brown clay, most of these bowls are slipped or have wash and burnish on the interior and on the rim. A few complete vessels (such as :20) have disk bases. This is the most common bowl type at the end of the Iron IIC. While such bowls are common in layers 10-1–10-4 too, their popularity is exceptional in layer 10-2, like their presence in Stratum 9/10 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 5.1–5.4, B-9III). It is also the most common bowl type in Stratum 9, where it is described as an Iron Age type that ‘remained in use throughout the Persian period as well’ (Shalev Citation2015: 204–205).

B5: Medium-sized/large bowl with outfolded rim (:22–23, 2:1–3)

Made of reddish-brown clay, generally slipped and burnished on the interior and the rim, this is a common Iron IIB–C type. :1 is exceptional in its lack of external treatment. Relating to such vessels in Stratum 9, above Stratum 9/10, Shalev (Citation2015: 205, BL-8) notes that some of the bowls of this type have ‘the typical Persian period burnishing’. Similar bowls with transparent burnish or without external treatment began to appear already in Stratum 9/10 (e.g., :1).

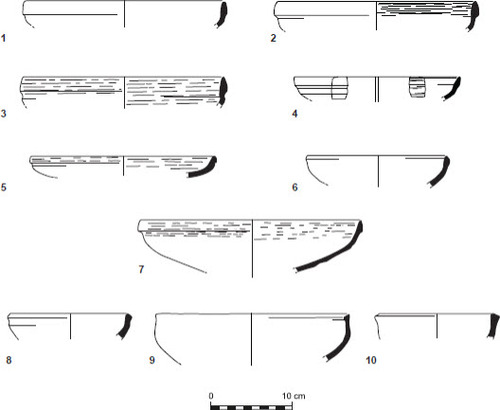

Fig. 2: Bowls

i See , n. i on p. 249.

B6: Outfolded-rim bowl without wash or slip (:4–7)

The outfolded rim is tightly compressed against the wall. This is a version of Type B4, but made of light brown or beige clay. These vessels are often shallower than other B4 or B5 bowls and either have no external treatment or have a transparent or light yellowish burnish hue. The type is not found in Iron IIC strata and is relatively uncommon later during the Persian period as well.

B7: Small/medium-sized rounded bowl (:8–10, 3:1)

This bowl type has a rounded slightly carinated wall and an unshaped rim, slightly sharpened upward, or a diagonally cut rim. These vessels are made of whitish-buff clay with no external treatment. :1 could be a lid, based on its shape and its unprocessed surface and rim. Lids are not at all common at the end of the Iron Age, but a few, dated to the Persian period, have been found (Zuckerman Citation2012: .4:17–18), made of cooking-pot material. The type became more common toward the Hellenistic period.

Fig. 3: Bowls and kraters

i See , n. i on p. 249.

ii See , n. i on p. 249.

B8: Small bowl with thin unshaped wall and rim (:2–3)

The straight-sided bowl version (:2) is a common Judahite type in the Iron IIB. The hemispherical bowl version (:3) is common mainly from the second part of the Iron IIC. It is very difficult to distinguish, on the basis of the rim only, between straightsided and hemispherical bowls.

B9: Medium-sized/large rounded bowl (:4–5)

This type of bowl, with unshaped rim turned inward, made of either reddish-brown or beige clay, become more common during the Persian period (see Stern Citation2015b: Pl. 5.1.2:3,5). :5 has a band attached on the outside under the rim. Such rims are common at the very beginning of the Persian period.

B10: Carinated bowl (:6)

This is a small bowl with a carination in the middle of the wall and an unshaped rim. An identical sherd was found in the Early Persian fill above Stratum 9/10 (Shalev Citation2015: .1:8, not common in the assemblage, possibly part of the same bowl). Similar bowls are common in Early Persian assemblages.

Fig. 4: Kraters, cooking pots, jugs, juglets and jars

i See , n. i on p. 249.

ii See , n. i on p. 249.

B11: Rounded carinated bowl (:7–8)

This bowl has an unshaped, upward-turned rim. Made of brown clay, it bears both wash and burnish. Although the burnish and wash are typical of the Iron IIC, this is not a common Iron IIC type.

B12: Carinated small/medium-sized bowl with ledge rim (:9–12)

This type is made of brown clay with red slip and burnish on the interior and either on the entire exterior or just below the rim. Bowls of this type are common at the end of the Iron IIC. The vessels represented in :10–11 have an outer ridge under the rim. Similar bowls with a ridge on the external wall are considered to have Assyrian influence (and see Stern Citation2015a: Pl. 4.4.2:3–6).

B13: Carinated bowl with long everted ledge rim (:13–14)

This type—a small or medium-sized bowl made of light clay, generally with a light yellowish hue burnish—is common during the Early Persian period.

B14: Black bowl (:15)

This is a carinated bowl with a ledge rim, slipped and burnished like Types B12 and B13, but made of black clay. A few bowls made of black clay and with a similar shape have been found at various sites in Israel, but such bowls are more common in the Amman region—e.g., at Tall al-Ꜥin Tal, Tell Jawa and Hesban, and in Edom, at Busayra (Daviau and Graham Citation2009; Herr Citation2006: :13, 3:14), and are dated to the Iron IIC and the Persian period. Although they are local in Jordan, their shapes represent Assyrian influence (Anastasio Citation2010: Pl. 12:4–11).

Miscellaneous bowl or chalice (:16)

A single sherd of this type was uncovered, with an upright rim and a ledge beneath it. It is made of reddish-brown clay and bears irregular horizontal burnish on the exterior. It is a local imitation of a Phoenician chalice-shaped vessel. A similar vessel originating from layer 10-1 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: 258, .16:230, described as a unique vessel), made of different well-sorted clay, might belong to the group of Phoenician chalice-shaped vessels dated to the 7th–6th centuries BCE (and see Freud Citation2016b).

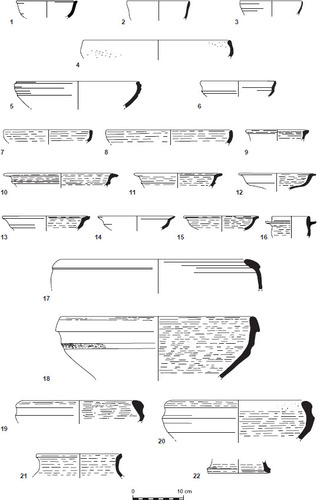

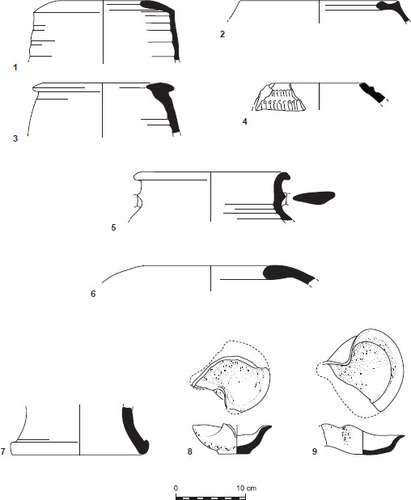

Fig. 5: Jars, pithoi, stands and lamps

i See , n. i on p. 249

ii See , n. i on p. 249.

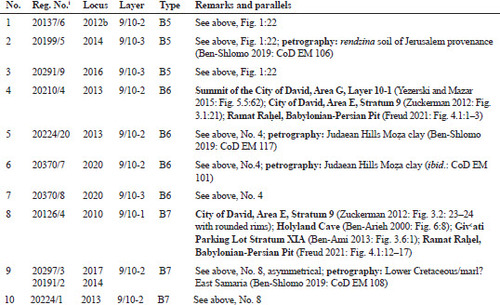

Kraters

K1: Open krater with outfolded rim (:17–18)

This type, made of reddish-brown clay, is generally slipped and burnished on the interior and on the rim. It is a very common Judahite type during the Iron IIB–C. It is noteworthy that the type does not continue into the Persian period and was probably replaced by other, smaller, krater types, such as mortaria.

K2: Large bowl or krater with outfolded rim (:19–20)

This is a variant of Type K1, made of light beige clay, generally with a yellowish burnish.

K3: Deep krater (:21–22)

This type is a deep krater with a neck and a shaped rim made of reddish-brown clay with slip and burnish. It is a common Judahite type during the Iron IIC, generally with a small ring base. The trumpet base of one such krater is shown in :22.

K4: Deep krater with splayed rim (:1)

This deep krater, with short neck and slightly outsplayed rim, is similar to the deep kraters of Type K3, but made of light brown-beige clay. Such kraters become very popular during the Early Persian period, with a large variety of rim shapes.

K5: Deep krater with gutter rim (:2)

The gutter rim generally functions as a receptacle for a lid and is more common on cooking pots. The clay of the vessel represented in :2 is light brown-beige, like that of other vessels in the assemblage.

Cooking pots

CP1: Neckless cooking pot (:3–6)

This is an open neckless cooking pot (rim diameter: ca. 10–15 cm), with an outturned rim, with or without a groove on the edge. Two handles are drawn from the rim to the body. In the Iron Age fills of Stratum 10 at the Summit of the City of David, it is the most common type of cooking pot, especially in layer 10-1 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Fig. 5.7:91–96 [note that the scale there for Nos. 93–96 is erroneous]; see also Tables 10-1–10-4, CP-3). In the Early Persian fill above it, from Stratum 9, it is the only type in layer 9-8 and is less prevalent in later layers 9-5 to 9-2, according to Shalev (Citation2015: 209, 213, CP-2). This is the most common type of cooking pot uncovered in the Babylonian-Persian Pit at Ramat Raḥel (Freud Citation2021: 39). It is one of the two most common types during the Iron IIC and the only type that continued into the 6th century BCE, until the beginning of the Persian period. In the Babylonian stratum, vessels of this type are relatively small and thin-walled.

CP2: Closed cooking pot (:7)

This type is a closed cooking pot with ridged neck, slightly turned outward, the lower ridge more pronounced than the upper ones. It is a common Judahite type of the Iron IIC— mainly found in the first half of this period. Only a few sherds of this type were found in the Babylonian stratum ().

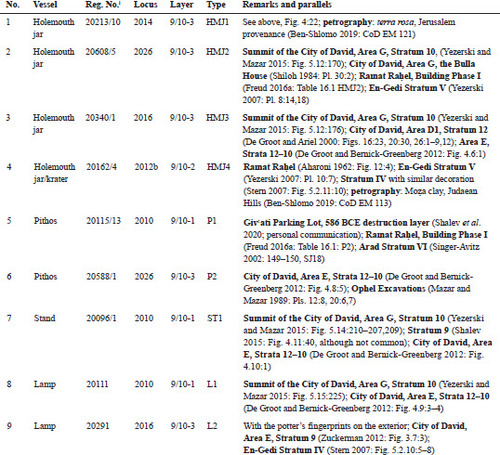

Table 2: Pottery types from Stratum 9/10 compared to Iron Age fills (layers 10-2 and 10-1) and Early Persian fills (layers 9-8 to 9-5)

CP3: Open cooking pot (:8)

This cooking pot, with inturned ridged rim, is common mainly in the Iron IIB. Only a few sherds were found in the Babylonian stratum. In Stratum 10, it is less common in layer 10-1 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 10-1–10-4).

Jugs

It is difficult to draw distinctions between various types of jugs and between jugs and jars on the basis of rims alone. This is especially true with regard to vessels from the beginning of the Persian period, when there was great variety in pottery production. Most of the jugs and jars probably belong to this transitional period of the 6th century BCE. A few Judahite Iron IIC types are also present within the assemblage.

JG1: Jug with outturned rim (:9)

The jug has a wide neck and an unshaped, thickened outturned rim. Most jugs of this type are made of light brown–beige clay.

JG2: Jugs with thickened rounded rim (:10)

Most jugs of this type are made of light brown–beige clay.

JG3: Jug with trefoil rim (:11)

This type is common during the Iron IIC and the Early Persian period.

JG4: Jug with trumpet neck (:12)

This type, which has red slip on its exterior, is a popular Judahite type, common mainly during the Iron IIC.

JG5: Jug with narrow neck (:13)

This vessel, with a decanter rim, is a common Iron IIC Judahite type, which continues with some changes into the beginning of the Persian period (Stern Citation2015b: Pl. 5.1.16:1–3).

Juglets

JT1: Globular juglet (:14)

This juglet, with thin neck and unshaped rim and a handle drawn from the rim to the shoulder, is a common Judahite type of the Iron IIB–C.

JT2: Elongated juglet (:15)

This is a common Judahite type of the Iron IIB–C.

JT3: Alabastron (:16)

This vessel has a thick wall and red slip and burnish on the exterior. Such vessels, although not particularly common, are more characteristic of the Iron IIC than the Persian period (and see Stern Citation2015b: 576).

Jars

JR1: Jar with thickened rounded rim and short neck (:17–18)

Such rims belong to the bag-shaped jar, a common Judahite type in the Iron IIC, which continued (with few changes) into the Persian and Hellenistic periods. As only rims were found, it is almost impossible to pinpoint the date for this type. Vessels of this type were produced in either reddish-brown or beige clay.

JR2: Four-handled jars or lmlk jars (:19–21)

To the naked eye, some of the rims appear to be made of the same clay as the lmlk- or rosette-stamped jars (:19), whereas others seem to be of Moẓa (light brown–beige) clay (e.g., :20–21). The latter is more characteristic of the four-handled jars with lion or yhwd stamp impressions on their handles, dated to the Babylonian and Early Persian periods (see Freud Citation2021: 50–53).

Holemouth jars

HMJ1: Small cylindrical jar with holemouth rim (:22–27, 5:1)

The rim of this jar is either of uniform thickness (:22–24,26, 5:1) or widening at the edge (:25,27) and is either rounded (:23,25,27, 5:1) or cut (:22,24,26). Most vessels of this type that were uncovered at the Summit of the City of David were made of Moẓa clay. Most of the holemouth jars of Stratum 10-1 were of this type (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 5.1–5.4, HJ-1). The large quantity of such vessels at the very end of the Iron IIC is a well-known phenomenon from many other sites in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Freud Citation2019).

HMJ2: Holemouth jar with gutter rim (:2)

This type sometimes appears with handles. It is typical of the end of the Iron IIC and was most common in layer 10-2 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 5.1–5.4, HJ-2).

HMJ3: Holemouth jar with short rim, triangular in section (:3)

The rim of this type projects beyond the wall. Such holemouth jars are typical of the end of the Iron IIB and the beginning of the Iron IIC (Barkay, Fantalkin and Tal Citation2002; Freud Citation2019: HMJ4).

HMJ4: Holemouth jar or deep krater with ridged rim (:4)

The rim continues the inverted wall. :4 is of special interest as it is decorated on the exterior with two rows of small dots and lines. Such decoration differs from the wedge decoration typical of the Early Persian period, but could be its early prototype.

Pithoi

P1: Pithos with wide neck (:5)

This type has a rim that turns outward, a ridge in the middle of its neck and two handles drawn from mid-neck down to the shoulder. It is made of Moẓa clay. Although not common, the type is known from other Iron IIC sites.

P2: Pithos with inverted rim (:6)

These vessels, made of Moẓa clay, are a well-known Judahite type. Since all we have are rims, it is difficult to determine whether the vessel is similar to the Iron IIB type (with wide shoulder and a body narrowing toward a rounded base) or the Iron IIC version (with cylindrical body and many air bubbles).

Stands

ST1: Short cylindrical stand (:7)

Made of reddish-brown or beige (Moẓa) clay, this is a common Judahite Iron IIB–C type.

Lamps

L1: Lamp with disk base (:8)

The small disk base of this lamp is more common during the Iron IIB, but still appears during the Iron IIC.

L2: Lamp with flat base (:9)

This type is more common during the Early Persian period.

Discussion

The above presentation of the ceramic assemblage points to several main chronological groups. The assemblage of Stratum 9/10 contains mainly Iron IIC types (B1, B3–B5, B8, B11, B12, B14, K1, K3, CP1–CP2, JG3–JG5, JT1–JT3, JR1–JR2, HMJ1–HMJ2, P1– P2, ST1 and L1), with a few new types. Some of the latter are not common in the Early Persian period (B2, B6, B10, K2 and JG1–JG2), while others become more common (B7, B9, B13, K4–K5, JR1, JR2, HMJ4 and L2). For this reason, the assemblage of Stratum 9/10 is characterised as a transitional assemblage that represents the changes that pottery manufacture underwent during the 6th century BCE, with Iron Age types still present, but with new variants beginning to make an appearance. Approximately one quarter of the bowls in Stratum 9/10 are within the ‘non-typical’ standard for Iron IIC types (); most of these bowls, however, are not typically Persian either and therefore, it is argued, should be identified as ‘Babylonian types’.

In total, 26 samples, representing some common Iron IIC types—especially those made of clay that appeared to the naked eye to be uncommon in the Iron IIC assemblage—were taken for petrographic analysis (Ben-Shlomo Citation2019: 156–157, 265, 297–299, Samples CoD EM 101–126). Results show that most of the vessels were produced locally of terra rosa, of a mixture of terra rosa and rendzina, or of Moẓa clay. The shift in the raw material from the terra rosa/rendzina mixture in the Iron IIC to Moẓa clay in the Babylonian to Persian periods is very well demonstrated even in this small sample. Pottery types made of terra rosa or of terra rosa/rendzina are typical of the Iron IIC (B4, B5, B12, chalice, CP1, HMJ1),Footnote11 while pottery types made of Moẓa clay are Iron IIC, Babylonian and Early Persian types (B2, B4, B6, JG1, JR2, HMJ1, HMJ4).Footnote12 Exceptional are B5 which is made of marl; B7 probably originating in eastern Samaria; and B9,Footnote13 made of rendzina and probably originating from the Shephelah.Footnote14

When one compares the Iron IIC vessel forms from Stratum 10 to those of Stratum 9/10, a change is notable. Bowl types B2, B6, B7, B9, B10 and B13, jug types JG1, JG2 and JG5 and jar types JR1 and JR2 represent new types that developed from their Iron IIC predecessors. These vessels are no longer uniform and mass-produced, like the ones that were characteristic of the Iron IIB–C. Instead, these new forms represent degenerated shapes, made in new raw material. By way of example, the flat bowls (type B1), common in the Iron IIB–C, when they were manufactured out of terra rosa or terra rosa/rendzina clay, were formed out of Moẓa clay in the Babylonian period (Ben-Shlomo Citation2019: CoD EM 110, 119), and became less common and infrequent (type B2). These B2 bowls were rarely found in the Persian period. The bowls with outfolded rims (B4 and B5) are relatively small and not as well burnished as those of Stratum 10. There is also a transition in type of clay. While all the bowls with outfolded rims uncovered in Stratum 10 appear to be made of terra rosa or terra rosa/rendzina soils, most of the Stratum 9/10 bowls of this type continue to be manufactured from this clay group (ibid.: CoD EM 103, 104, 105, 106, 109, 111), but a few are now produced from Moẓa clay (ibid.: CoD EM 110,112,118,119). Bowls of the new type B6, are all made of Moẓa clay (ibid.: CoD EM 101,117), without slip or wash, and they are shallower. The carinated bowls (B12) with short ledge rim were manufactured out of terra rosa or terra rosa/rendzina clay during the Iron IIB–C (ibid.: CoD EM 105). There is a shift towards Moẓa clay and the ledge rim becomes wider during the Persian period (B13).

The neckless cooking pot (CP1) is the main type of this vessel in the Iron IIC, along with the type with the high neck and ridge in the middle (CP2). In the Babylonian stratum almost all the cooking pots are of this type (). It is noteworthy that although the 6th-century variant is often smaller, with thinner walls and sometimes without the ridge in the rim, it is not always possible to differentiate between the Iron IIC and Babylonian variants.

Similarities between the Iron IIC layers 10-1 and 10-2 of Stratum 10 and Stratum 9/10

Iron IIC layers 10-2 and 10-1 bear great similarity to Stratum 9/10. This is evident in the division and number of items of pottery types, as demonstrated in and in Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 5.1 and 5.2. There is a slow and gradual transition from the Iron IIC pottery shapes toward new Babylonian-period types that are not traditionally ‘Iron Age types’, but are similar to them. A few non-Iron Age types already appear in layer 10-2, and the number of such items grows in layer 10-1. Examples are: bowl types B6 (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Type B-9:II, Fig. 5.5:62, layer 10-1) and B9 (ibid.: Type B-6, Fig. 5.3:39, layer 10-1); jug types JG5 (ibid.: Type J-1, Fig. 5.9:116, layer 10-1) and JG1 (ibid.: Types J-5 and J-6, Fig. 5.10:132,134,135, layers 10-1 and 10-2); and jar type JR1 (ibid.: Type SJ-6, Fig. 5.11:155–156, layer 10-2).Footnote15

The similarity between Stratum 9/10 and layers 10-1 and 10-2 is also noticeable in the cooking pots and the large number of the holemouth jars.Footnote16 CP1 is almost the only type of cooking pot in Stratum 9/10 () and the most common type in layer 10-1; in layers 10-2–10-4, other types also appear in large quantities (Yezerski and Mazar Citation2015: Tables 5.1–5.4, CP-3). Holemouth jar type HMJ1 is the most common in Stratum 9/10 (ca. 80% of the holemouth jars; ), mainly in layer 10-1 (ibid.: Type HJ-1, Fig. 11:159–166; Tables 5.1–5.4; 65 items, ca. 90% of the holemouth jars) and layer 10-2 (30 items, ca. 40% of the holemouth jars), while in layers 10-3 and 10-4 there are isolated items. This gradual increase, starting in layer 10-2, reaches its peak in layer 10-1 and declines after Stratum 9/10. Whatever the reasons for this change, they might reflect economic or political changes in Jerusalem and its vicinity in the course of the Babylonian domination, before and after the 586 BCE destruction.

This similarity between layers 10-2 and 10-1 and Stratum 9/10 is in keeping with the excavator’s definition of both layers 10-2 and 10-1 as post-586 BCE destruction layers. Layer 10-1 is defined as ‘removal of destruction debris from conquest of 586 BCE’ (Mazar Citation2015: 17, 51–53). Given that layers 10-2 and 10-1 already contain some of the non-typical Iron IIC sherds, I would suggest that at the very least, layer 10-1 should be merged with Stratum 9/10 and hence belongs to the Babylonian period. It should be noted that Mazar’s rationale at the time for differentiating the Babylonian fills from the Iron IIC and the Early Persian fills was probably also based upon the two lion-stamped impressions retrieved in the lowest layer of this stratum—9/10-3,Footnote17 which were recently dated to the Babylonian period (Ornan and Lipschits Citation2020; Lipschits and Koch Citation2021).

Continuity in pottery production from the late Iron Age to the Early Persian period in Jerusalem

The Iron Age tradition in pottery production is well represented in the Babylonian and Early Persian period pottery in Jerusalem. This points to continuity of life in the city, as in the rural sites in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Gadot Citation2015) and at Ramat Raḥel (Lipschits et al. Citation2011; Lipschits et al. Citation2021; Freud and Shalev Citation2023).

This continuity notwithstanding, it is clear that the industry that produced the red-burnished pottery so typical of the Iron IIB–C in Judah underwent some major upheaval. Franken (Citation2005: 93, 198) suggests that the potters, like others, were exiled:

The result of the study of the temper classification showed that the potters working for the Jerusalem market were not the same as the pre-exilic potters. … Obviously the pre-exilic Jerusalem potters suffered the same fate as the other inhabitants of the city and went into exile. And when the town was inhabited again it attracted potting families from elsewhere. (Franken Citation2005: 93)

Contrary to Franken, I would suggest that while some of the traditional workshops ceased to operate, others continued to function. For example, the holemouth jars that flourished towards the end of the Iron IIC and are found in large numbers in the rural sites in Jerusalem’s environs continue to be found in large quantities in Stratum 9/10 and the GivꜤati Parking Lot excavations after the destruction.Footnote18 These holemouth jars (just like the large pithoi) were manufactured from either terra rosa clay or Moẓa clay during the Iron IIB–C. Toward the end of this period they were manufactured mainly from Moẓa clay, as exemplified in Stratum 9/10 (where most of the holemouth jars are made of light brown Moẓa clay).Footnote19

Toward the end of the Iron IIC, pottery types such as bowls, kraters, and jugs were manufactured from terra rosa and terra rosa/rendzina (Boness and Goren, forthcoming; Ben-Shlomo Citation2019), probably in workshops that specialised in manufacturing these types. It is possible that the crisis in pottery production at the beginning of the 6th century BCE occurred in those workshops that worked with terra rosa/rendzina clay and did not affect other workshops—since gradually, all pottery types transitioned to Moẓa clay (for example, the four-handled yhwd jars, bowls, jugs and other vessel types) away from the terra rosa/ rendzina clay (Gorzalczany Citation2012; Ben-Shlomo Citation2019). Potters may have tried for the first time to produce small vessels, perhaps in order to meet the demands of customers who preferred the same pottery types to which they were used in the past. The results may have turned out somewhat different, either because these potters were less trained in the special manufacture of small vessels or because the new raw material (the Moẓa clay) dictated different production methods. As a result, the vessels had a different appearance both in shape and in their finishing technique (see Franken and Steiner Citation1990: 64). In any case, the inconsistency in pottery production, evident in the non-typical Iron IIC pottery types in the Babylonian Stratum 9/10 and even in layer 10-1 at the Summit of the City of David, later became a hallmark of the Early Persian period.

Pottery production is very conservative, and political changes do not necessarily impact the potter’s work, but we are aware that such an impact may have occurred. Research conducted into the forms of vessels before and after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem show that a different type of clay was used before and after the event (Adan-Bayewitz et al. Citation2016). It was demonstrated that changes in the source of clay may serve as a tool for archaeologists to differentiate changes over the course of time. Adan-Bayewitz et al. (ibid.: 26–28) concluded that outside Jerusalem there was continuity in settlement after 70 CE and that the change in type of clay occurred because potters could not obtain the previously used raw material. A similar phenomenon from recent times was reported by Salem (Citation2006) on traditional Palestinian pottery making in the Jerusalem–Hebron environs: ‘the main source of clay (for potters from these areas) was in the area of Pisgat Zeʾev and the place was confiscated and the access to clay source was forbidden. The potters were to obtain their clay from el-Jib. Experiments from other nearby clay sources failed.’Another potter, according to Salem, reported that: ‘after the 1948 war, the clay resources were situated outside the West Bank’ (Salem Citation2006: 51–63). These examples show that when access to raw materials is restricted due to political changes, manufacture continues, but with different types of clay from other sources. These examples might explain why the ‘red pottery’ of Jerusalem was no longer produced—perhaps since the raw material for such vessels was no longer accessible after the destruction—and instead, potters began to produce the same shapes (e.g., bowl B6) or similar shapes (e.g., bowls B4–B5, B9, B13), but in a different type of clay.

Summary

The pottery retrieved from the stratified fills of Stratum 9/10 and Phase 10-1 from the Summit of the City of David, Area G, is of great importance since it represents an assemblage of the 6th century BCE, not commonly found in excavations. A detailed study of the pottery types uncovered may contribute to a better understanding of transitional processes during the short lifespan of the Babylonian period. Excavator Eilat Mazar defined Stratum 9/10 as a Babylonian stratum (Mazar Citation2015: 17, 41–45). The aim of the present study was to consider how this stratum assemblage differs from other Iron IIC layers attributed to the 586 BCE destruction or from Early Persian pottery. The assemblage of this stratum was assessed as a combination of pottery types largely dating to the very end of the Iron IIC and a sample of new types, manufactured out of different material in a different production process. While the Early Persian stratum was designated primarily according to Persian pottery types (with some Iron Age sherds), the Babylonian stratum (9/10) beneath it (and even layer 10-1 of the Iron Age Stratum 10) represents the transition between the Iron IIC and the Persian period.

This transitional period included vessels that were manufactured before the 586 BCE destruction, but continued in use and probably even continued to be manufactured. Examples are cooking pot CP1, some examples of bowl B4 and the holemouth jars. It also contains new vessels that reflected a variety of manufacturing methods, as well as a change in quality and shape. Approximately a quarter of the bowls in the Stratum 9/10 assemblage are non-Iron IIC types dated to the 6th century BCE. These changes are well connected to the Iron IIC types and shapes and can be characterised as a direct continuation of them.

It appears that following the changes and destruction in Judah around 586 BCE, the production of pottery became less specialised and more decentralised. The Iron IIC mass production of red-slipped and burnished small vessels is discontinued, and a gradual change in the raw material and a decrease in quality production is evident. We can only surmise how long in the 6th century BCE it took for these changes to take place. Changes in material culture are slower and might occur later than the political or economic changes that caused them. It is obvious, however, that the former Iron Age types were familiar to the potters who imitated them and continued to produce vessels. It is only toward the end of the 6th century—still within the beginning of the Persian period—that completely new pottery types appear (e.g., the deep kraters with wedge decoration and the carrot-shaped juglets). It is at this same time that the gradual change in the raw material is completed, with Moẓa clay now serving almost exclusively as the raw material for locally produced pottery.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express her gratitude to Oded Lipschits, Ido Koch and the anonymous readers for their valuable input that improved this article, as well as to Yulia Gottlieb for preparing the figures and to Tsipi Kuper-Blau for her meticulous editing of the article.

Disclosure statement

The author reports that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Liora Freud

Liora Freud: The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University

Notes

1 See summary of research and further literature in Lipschits Citation2005: 185–191; Faust Citation2012: 181–207.

2 On this subject, see, e.g., the title of Stern’s article (1998: 19–20) ‘Is there a Babylonian Period in the Archaeology of the Land of Israel?’, as well as his article (2000) ‘The Babylonian Gap’. Faust Citation2007; Citation2011; Citation2012: 181–207; see also Finkelstein and Singer-Avitz Citation2009: 40–42.

3 According to Barkay (Citation1993; Citation1998), the date of the destruction 587/586 BCE is not at all relevant to the history of most parts of the Southern Levant. He noted that it seems that the destruction of the Temple and the fall of Jerusalem influenced modern scholarship, which fixed the date of the end of the Iron Age according to a historical fact and not on the basis of the archaeological picture.

4 Contra Faust (Citation2007; Citation2011; Citation2012), who continues to claim that the land was almost completely devoid of population, based on burial customs, economic considerations and settlement distribution.

5 See publications by Franken and Steiner (Citation1990) and Franken (Citation2005: 65, 93) of Kenyon’s (1974: 183) excavations of the same fills adjacent to Mazar’s excavations. While their research on the pottery sherds was of great importance from the technological and petrographic perspective, the limited typological knowledge available at that time, coupled with the erroneous assumption that the land was left empty in the post-exilic period, led to the division into ‘pre-exilic’ (Iron Age) and ‘post-exilic’ (Persian period) times.

6 See, e.g., Wampler Citation1947: 9; Tushingham Citation1985; Stern Citation2000; Citation2001: 343, 514–515; Mazar and Panitz-Cohen Citation2001: 187; Ben-Arieh Citation2000: 13; Berlin Citation2012: 7; Lipschits Citation2005: 192–206.

7 Conducted within the framework of my Ph.D. dissertation (Freud Citation2018).

8 Phase XIA contains pottery types typical of the Iron IIC, such as rosette storage jars (Ben-Ami Citation2013: Fig. 3.7:10–14), alongside a few non-typical Iron IIC or ‘Babylonian types’ (ibid.: Figs. 3.6:1,8,19, 3.7:2,4–5,7–8, 3.8:2). Strata X and IX feature many parallels (ibid.: Figs. 3.10:1,15–18, 3.11:1,8–9,11–14) of the ‘Babylonian types’, as described above in Stratum 9/10 from the Summit of the City of David. In addition, Stratum IX yielded a sherd of a Persian cooking pot (ibid.: Fig. 3.11:9). I have therefore suggested (Freud Citation2019: 133–134) that Stratum XIA should be dated to the 586 BCE destruction and that Stratum X should be dated within the 6th century BCE to the Babylonian period. Stratum IX should be dated to the beginning of the Persian period—the second half of the 6th century to the beginning of the 5th century BCE.

9 Since some loci were disturbed over the years, only clean loci are discussed (Mazar Citation2015: 43–45). I am grateful to the late Dr. Eilat Mazar for allowing me to use and include this material in my Ph.D. dissertation (Freud Citation2018) and to her sister, Avital Mazar-Tsairi, for her permission to include the material in this article.

10 Most of the pottery types under discussion are well known and have been widely studied.

11 See :16–21, 2:2, 3:12,16, 4:3–6,24 and 4:26, respectively.

12 See :7–9,19, 2:4–6, 4:9,20,23,25,27 and 5:4, respectively.

13 For B5, B7 and B9, see :23, 2:9 and 3:5, respectively.

14 This gradual transition, evident in the excavations at the Summit of the Southeastern Hill of Jerusalem, from the use of the terra rosa and terra rosa/rendzina clay to the use of Moẓa clay was noticed by Franken (Citation2005: 198) with regard to sherds from Kenyon’s excavations.

15 Isolated sherds from layer 10-1, which were not included in the excavation report, have been tested at the IAA storehouse at Beth Shemesh and can be added to the above list of Babylonian types from this layer: flat bowl B2: Reg. Nos. 21178/2 L2033; outfolded rim bowls B6: Reg. Nos. 21049/1 L2033, 20874/5 L2033, 20738/2 L2028 and 20874/1 L2033; bowl with cut rim B7: Reg. Nos. 21031/8 L2036 (layer 10-2); jars JR1: Reg. Nos. 21075/8, 20779/7, L2028, 20281/5, 20613/1, 20613/2 L2024, 21471/4 L2042; flat lamp L2: Reg. No. 20650/6 L2028.

16 As already noted by Franken and Steiner (see above, holemouth jars).

17 A third lion stamp impression is a surface find (see Winderbaum Citation2015: 541–543 for further discussion and references).

18 Thanks are extended to Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev for giving me permission to examine the pottery from the GivꜤati Parking Lot excavations. On the wide distribution of holemouth jars in rural sites around Jerusalem, with chronological discussion and references, see Freud Citation2019; see also Barkay, Fantalkin and Tal Citation2002 for the history of the research.

19 Franken and Steiner already pointed out that the number of holemouth jars increased dramatically at the end of the Iron Age and that like other types, they are made of Moẓa clay that contains dolomite sand. This type of clay was very popular at the beginning of the Iron Age, but then declined; toward the 6th century and the Persian period, the use of this type of clay increased, and it became the most common material for the pottery industry (Franken and Steiner Citation1990: 83, 112–113; Franken Citation2005: 65–66, 98; Steiner Citation2001: 57).

References

- Adan-Bayewitz, D., Asaro, F., Osband, M., Wieder, M. and Giauque, R.D. 2016. Pottery Production and Historical Transition: New Evidence from the Jerusalem Area in the Early Roman Period. Cathedra 160: 7–28 (Hebrew).

- Aharoni, Y. 1962. Excavations at Ramat Raḥel I: Seasons 1959 and 1960 (Universita di Roma Centro di Studi Semitici, Serie Archaeologica 2). Rome.

- Aharoni, Y. 1964. Excavations at Ramat Raḥel II: Seasons 1961 and 1962 (Universita di Roma Centro di Studi Semitici, Serie Archaeologica 6). Rome.

- Anastasio, S. 2010. Atlas of the Assyrian Pottery of the Iron Age (Subartu 24). Brepols.

- Barkay, G. 1985. Northern and Western Jerusalem in the End of the Iron Age (Ph.D. dissertation, Tel Aviv University). Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

- Barkay, G. 1993. The Redefining of Archaeological Periods: Does the Date 588/586 B.C.E. Indeed, Mark the End of Iron Age Culture? In: Biran, A. and Aviram, J., eds. Biblical Archaeology Today 1990: Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem June–July 1990. Jerusalem: 106–109.

- Barkay, G. 1998. The Iron Age III: The Babylonian Period. In: Lipschits, O., ed. Is It Possible to Define the Pottery of the Sixth Century B.C.E. in Judea? (Booklet of Summaries of Lectures from the Conference Held in Tel Aviv University). Tel Aviv: 25 (Hebrew).

- Barkay, G., Fantalkin, A. and Tal, O. 2002. A Late Iron Age Fortress North of Jerusalem. BASOR 328: 49–71.

- Ben-Ami, D. 2013. Jerusalem Excavations in the Tyropoeon Valley (GivꜤati Parking Lot) (Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 52). Jerusalem.

- Ben-Arieh, S. 2000. Salvage Excavations near the Holyland Hotel, Jerusalem. ꜤAtiqot 40: 1–24.

- Ben-Shlomo, D. 2019. The Iron Age Pottery of Jerusalem: A Typological and Technological Study (Ariel University Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 2). Ariel.

- Berlin, A.M. 2012. The Pottery of Strata 8–7 (The Hellenistic Period). In: De Groot, A. and Bernick-Greenberg, H. Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. VIIb: Area E: The Finds (Qedem 54). Jerusalem: 5–29.

- Boness, D. and Goren, Y. Forthcoming. Petrographic Study of the Iron Age and Persian Period Pottery at Ramat Raḥel. In: Lipschits, O., Freud, L., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. Ramat Raḥel V: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): The Finds (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA.

- Daviau, P. M. and Graham, J.A. 2009. Black-Slipped and Burnished Pottery: A Special 7th Century Technology in Jordan and Syria. Levant 41: 41–58. doi: 10.1179/175638009X427585

- De Groot, A. 2001. Jerusalem during the Persian Period. In: Faust, A. and Baruch, E., eds. New Studies on Jerusalem Volume 7. Ramat Gan: 77–81 (Hebrew).

- De Groot, A. and Ariel, D.T. 2000. Ceramic Report. In: Ariel, D.T., ed. Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. V: Extramural Areas (Qedem 40). Jerusalem: 91–154.

- De Groot, A. and Bernick-Greenberg, H. 2012. The Pottery of Strata 12–10 (Iron Age IIB). In: De Groot, A. and Bernick-Greenberg, H. Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. VIIb: Area E: The Finds (Qedem 54). Jerusalem: 57–198.

- Eisenberg, E. and De Groot, A. 2006. A Tower from the Iron Age near Ramat Raḥel. In: Baruch, E., Greenhut, Z. and Faust, A., eds. New Studies on Jerusalem Volume 11. Ramat Gan: 129–134 (Hebrew).

- Faust, A. 2007. Settlement Dynamics and Demographic Fluctuations in Judah from the Late Iron Age to the Hellenistic Period and the Archaeology of Persian-Period Yehud. In: Levin, Y., ed. A Time of Change: Judah and Its Neighbors in the Persian and Early Hellenistic Periods. London: 23–51.

- Faust, A. 2011. Deportation and Demography in Sixth-Century B.C.E. Judah. In: Kelle, B.E., Ames, R.R. and. Wright, J.L., eds. Interpreting Exile: Displacement and Deportation in Biblical and Modern Contexts (Society of Biblical Literature Press 10). Atlanta: 91–103.

- Faust, A. 2012. Judah in the Neo-Babylonian Period: The Archaeology of Desolation (Society of Biblical Literature Press 18). Atlanta.

- Finkelstein, I. and Singer-Avitz, L. 2009. Reevaluating Bethel. ZDPV 125: 33–48.

- Franken, H.J. 2005. A History of Pottery and Potters in Ancient Jerusalem: Excavations by K.M. Kenyon in Jerusalem 1961–1967. London.

- Franken, H.J. and Steiner, M.L. 1990. Excavations in Jerusalem 1961–1967 Volume II: The Iron Age Extramural Quarter on the South-East Hill (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology No. 2). Oxford.

- Freud, L. 2016a. Pottery of the Iron Age: Typology and Summary. In: Lipschits, O., Gadot, Y. and Freud, L. 2016: Ramat Raḥel III: Final Publication of Yohanan Aharoni’s Excavations (1954, 1959–1962) (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 35). Tel Aviv and Winona Lake: 254–265.

- Freud, L. 2016b. A Note on Sixth-Century BCE Phoenician Chalice-Shaped Vessels from Judah. IEJ 66: 177–187.

- Freud, L. 2018. Judahite Pottery in the Transitional Phase between the Iron Age and the Persian Period: Jerusalem and Its Environs (Ph.D. dissertation, Tel Aviv University). Tel Aviv (Hebrew with English abstract).

- Freud, L. 2019. The Widespread Production and Use of Holemouth Vessels in Jerusalem and its Environs in the Iron Age II: Typology, Chronology and Distribution. In: Čapek, F. and Lipschits, O., eds. The Last Century in the History of Judah. The Seventh Century BCE in Archaeological, Historical, and Biblical Perspectives (Ancient Israel and Its Literature 37). Atlanta: 117–150.

- Freud, L. 2021. The Pottery Assemblage: Typology and Chronology. In: Lipschits, O., Freud, L., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. Ramat Raḥel VI: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): The Babylonian-Persian Pit (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 40). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA: 28–72.

- Freud, L. Forthcoming. The Pottery of the Iron Age and the Persian Period. In: Lipschits, O., Freud, L., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. Ramat Raḥel V: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): The Finds (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 40). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA.

- Freud, L. and Shalev, Y. 2023. Continuity and Change in 6th to 4th Centuries BCE Jerusalem). In: Gadot, Y. and Shalom, N., eds. Jerusalem in Transition: Decisive Moments in the Creation of Jerusalem in Reality and as a Myth (Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 11/4). Tübingen: 108–132.

- Gadot, Y. 2015. In the Valley of the King: Jerusalem’s Rural Hinterland in the 8th–4th Centuries BCE. Tel Aviv 42: 3–26. doi: 10.1179/0334435515Z.00000000043

- Gorzalczany, A. 2012. Petrographic Analysis of Persian Period Vessels. In: De Groot A., and Bernick-Greenberg, H., eds. Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. VIIb: Area E: The Finds (Qedem 54). Jerusalem: 51–56.

- Herr, L. 2006. Black-burnished Ammonite Bowls from Tall al-ꜤUmayri and Tall Hisban in Jordan. In: Maeir, A.M. and Miroschedji, P., eds. ‘I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times’. Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday Vol. 2. Winona Lake: 525–540.

- Kenyon, K.M. 1974. Digging Up Jerusalem. London.

- Lapp, N. 2008. Shechem IV: The Persian-Hellenistic Pottery of Shechem/Tell Balâṭah (American Schools of Oriental Research Archaeological Reports 11). Boston.

- Lipschits, O. 2005. The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Judah under Babylonian Rule. Winona Lake.

- Lipschits, O. 2011. Shedding New Light on the Dark Years of the ‘Exilic Period’: New Studies, Further Elucidation, and Some Questions regarding the Archeology of Judah as an ‘Empty Land’. In: Kalle, B., Ames, F.R. and Wright, J., eds. Interpreting Exile. Interdisciplinary Studies of Displacement and Deportation in Biblical and Modern Contexts. Atlanta: 57–90.

- Lipschits, O. 2021. Age of Empires: The History and Administration of Judah in the 8th–2nd Centuries BCE in Light of the Storage-Jar Stamp Impressions (Mosaics: Studies on Ancient Israel 2). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA.

- Lipschits, O., Freud, L., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. 2021. Ramat Raḥel VI: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): The Babylonian-Persian Pit (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 40). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA.

- Lipschits, O., Gadot, Y., Arubas, B. and Oeming, M. 2011. Palace and Village, Paradise and Oblivion: Unraveling the Riddles of Ramat Raḥel. Near Eastern Archaeology 74:2–49. doi: 10.5615/neareastarch.74.1.0002

- Lipschits, O., Gadot, Y. and Freud, L. 2016. Ramat Raḥel III: Final Publication of Yohanan Aharoni’s Excavations (1954, 1959–1962) (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 35). Tel Aviv and Winona Lake: 254–265.

- Lipschits, O., Gadot, Y. and Oeming, M. 2020. Deconstruction and Reconstruction: Reevaluating the Five Expeditions to Ramat Raḥel. In: Lipschits, O., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. Ramat Raḥel IV: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): Stratigraphy and Architecture (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 39). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA: 476–491.

- Lipschits, O. and Koch, I. 2021. Lion Stamped Impressions from the Babylonian Period. In: Lipschits, O., Freud, L., Oeming, M. and Gadot, Y. Ramat Raḥel VI: The Renewed Excavations by the Tel Aviv–Heidelberg Expedition (2005–2010): The Babylonian–Persian Pit (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 40). Tel Aviv and University Park, PA: 76–80.

- Lipschits, O. and Vanderhooft, D.S. 2011. Yehud Stamp Impressions: A Corpus of Inscribed Stamp Impressions from the Persian and Hellenistic Period in Judah. Winona Lake.

- Mazar, E. 2015. Stratigraphy. In: Mazar, E. The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008: Final Reports Vol. I: Area G. Jerusalem: 13–168.

- Mazar, E. and Mazar, B. 1989. Excavations in the South of the Temple Mount: The Ophel of Biblical Jerusalem (Qedem 29). Jerusalem.

- Mazar, A. and Panitz-Cohen, N. 2001. Timnah (Tel Batash) II: The Finds from the First Millennium BCE (Qedem 42). Jerusalem.

- Ornan, T. and Lipschits, O. 2020. The Lion Stamp Impressions from Judah: Typology, Distribution, Iconography, and Historical Implications. A Preliminary Report. Semitica 62: 69–91.

- Salem, H.J. 2006. Cultural Transmission and Change in Traditional Palestinian Pottery Production. Leiden Journal of Pottery Studies 22: 51–63.

- Shalev, Y. 2015: The Early Persian Period Pottery. In: Mazar, E. The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008: Final Reports Vol. I: Area G. Jerusalem: 203–241.

- Shalev, Y., Gellman, D., Bocher, E., Freud, L., Porat, N. and Gadot, Y. 2019. The Fortifications along the Western Slope of the City of David: A New Perspective. In: Peleg-Barkat, O., Zelinger, Y., Uziel, J. and Gadot, Y., eds. New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and Its Region: Collected Papers Vol. 13: War and Peace: Fortifications, Conflicts and Their Aftermath. Jerusalem: 51–70 (Hebrew).

- Shalev, Y., Shalom, N., Bocher, E. and Gadot, Y. 2020. New Evidence on the Location and Nature of Iron Age, Persian and Early Hellenistic Period Jerusalem. Tel Aviv 47: 149–172. doi: 10.1080/03344355.2020.1707451

- Shalom, N., Shalev, Y., Uziel, J.J., Chalaf, O., Lipschits, O., Boaretto, E. and Gadot, Y. 2019. How Is a City Destroyed? New Archaeological Data of the Babylonian Campaign to Jerusalem. In: Peleg-Barkat, O., Zelinger, Y., Uziel, J. and Gadot, Y., eds. New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and Its Region: Collected Papers Vol. 13: War and Peace: Fortifications, Conflicts and Their Aftermath. Jerusalem: 229–248.

- Shiloh, Y. 1984. Excavations at the City of David I 1978–1982: Interim Report of the First Five Seasons (Qedem 19). Jerusalem.

- Shiloh, Y. 1986. A Group of Hebrew Bullae. IEJ 36: 16–38.

- Singer-Avitz, L. 2002. Arad: The Iron Age Pottery Assemblages. Tel Aviv 29: 110–215. doi: 10.1179/tav.2002.2002.1.110

- Steiner, M.L. 2001. Excavations by Kathleen M. Kenyon in Jerusalem 1961–1967 Volume III: The Settlement in the Bronze and Iron Age (Copenhagen International Series 9). London.

- Stern, E. 1998. Is There a Babylonian Period in the Archaeology of the Land of Israel? In: Lipschits, O., ed. Is It Possible to Define the Ceramics of the Sixth Century B.C.E. in Judah? (Booklet of Summaries of Lectures from the Conference Held at Tel Aviv University). Tel Aviv: 19–20 (Hebrew).

- Stern, E. 2000. The Babylonian Gap. Biblical Archaeology Review 26/6: 45–51.

- Stern, E. 2001. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible II: The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Periods 733–332 B.C. New York.

- Stern, E. 2007. Persian Period Pottery. In: Stern, E. En-Gedi Excavations I: Final Report (1961–1965). Jerusalem: 19–227.

- Stern, E. 2015a. Iron Age IIC Assyrian-Type Pottery. In: Gitin, S. ed. The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Iron Age through the Hellenistic Period Vol. II. Jerusalem: 533–553.

- Stern, E. 2015b. Persian Period. In: Gitin, S., ed. The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Iron Age through the Hellenistic Period Vol II. Jerusalem: 565–617.

- Thareani, Y. 2011. Tel ꜤAroer: The Iron Age II Caravan Town and the Hellenistic–Early Roman Settlement. The Avraham Biran (1975–1982) and Rudolph Cohen (1975–1976) Excavations (Annual of the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion VIII). Jerusalem.

- Tushingham, A.D. 1985. Excavations in Jerusalem 1961–1967 Vol. I. Toronto.

- Wampler, J.C. 1947. Tell En-Naṣbeh Excavated under the Direction of the Late William Frederic Bade Vol. II: The Pottery. Berkeley and New Haven.

- Winderbaum, A. 2015. Lion Seal Impressions. In: Mazar, E. The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008: Final Reports Vol. I: Area G. Jerusalem: 541–543.

- Yezerski, I. 2007. Pottery of Stratum V. In: Stern, E. En-Gedi Excavations I. Jerusalem: 86–129.

- Yezerski, I. and Mazar, E. 2015. Iron Age III Pottery. In: Mazar, E. The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008: Final Reports Vol. I: Area G. Jerusalem: 243–298.

- Zorn, J.R. 1993. Tell en-Naṣbeh: A Re-evaluation of the Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Early Bronze Age, Iron Age and Later Periods (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley).

- Zorn, J.R. 2003. Tell en-Naṣbeh and the Problem of the Material Culture of the Sixth Century. In: Lipschits, O. and Blenkinsopp, J., eds. Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Winona Lake: 413–450.

- Zuckerman, S. 2012. The Pottery of Stratum 9 (the Persian Period). In: De Groot, A. and Bernick-Greenberg, H. Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. VIIb: Area E: The Finds (Qedem 54). Jerusalem: 31–56.