ABSTRACT

This paper examines the effects of policy responses to the COVID-19 global pandemic on Brisbane’s music industries. The methods used for data collection combined a review of policy documents at different levels of government, an on-line questionnaire with music workers, and semi-structured interviews with musicians and music industry workers to understand the impacts of COVID-19 mitigation strategies on various music industries, as well as to examine any opportunities that may have arisen from this disruptive event. The primary questions informing this research are thus what were the impacts of Queensland’s zero COVID policy on the music industries of Brisbane, and what can be learned for future music industry-related policy interventions? Based on data collected from an on-line survey and on semi-structured interviews with musicians and professionals from the Brisbane music scene, we conclude that while the QLD state government response to the crisis recognised to an extent the importance of Brisbane’s music industries, policy responses were not always seen as equitable in relation to other industries and that policy responses to future disruptive events would be better served with greater consultation and consistency.

Practitioner pointers

COVID-19 planning and policy responses lacked consistency, in particular there was a perception of inequality in the audience numbers available to the local music industries versus the sports industry.

Policy responses should have been more consistent, or the perceived lack of consistency should have been better explained. In order to better understand the effects of policy and planning on grassroots local music industries, a greater degree of government consultation is required.

Music industries need to find ways in which greater industry vcollectiveness can be achieved to improve advocacy efforts.

1. Introduction

The aim of this article is to evaluate how supportive the policy responses to the global COVID-19 pandemic were on the workers of Brisbane’s music industries and to examine what can be learned from the pandemic in terms of better supporting the music workers of Australia, with a particular focus on Brisbane and South-East Queensland (SEQ). As per Cai et al. (Citation2021), we analysed the response of musicians to the pandemic and investigated how they developed strategies to cope with the situation. From an urban studies perspective, a disruptive event such as the recent pandemic raises the question of how policy responses can be seen in terms of the concept of ‘just city’ developed by Fainstein (Citation2010). Fainstein (Citation2010, 8) explains that: ‘the choice of justice as the governing norm for evaluating urban policy is value laden. It reacts to the current emphasis on competitiveness and the dominance in policy making of neoliberal formulations’. Fainstein (Citation2010) names equity, democracy, and diversity as key pillars in a just city and we use this lens from which to view the policies of various levels of government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We also investigate how planning and health policies during the coronavirus affected the livelihoods and health of musicians and other music industry workers. As urban planning initiatives aimed at revitalising ailing post-industrial cities having now been in place for several decades in various cities around the world, including Brisbane (see Brown, O’Connor, and Cohen Citation2000; Pacella, Luckman and O’Connor Citation2021a; Montgomery Citation2004; Moss Citation2002), the coronavirus pandemic has been a test of the efficacy of planning and policy on developing appropriate conditions for the workforce that creates and sustains inner-city cultural vibrancy. This article investigates 1. How the pandemic affected the music industries in Brisbane and SEQ; 2. If it was easy to access financial support; 3. If the COVID-19 recovery included policy innovations and if policies were perceived as motivated by the kinds of equitable economic and social outcomes that define the concept of the ‘just city’. Susan Fainstein is a planning academic, therefore the concept of the ‘just city’ is strongly connected to planning policies. In the literature review, we examine how planning and music scenes are growing ever more connected in the wake of the ‘creative cities’ movement spearheaded by Florida (Citation2005). Lately, the adoption of ‘music policies’ in Australia is an extension of that trend (See Darchen, Willsteed, and Browning Citation2022).

For the purposes of our research, and building on Williamson and Cloonan (Citation2007), rather than a single all-encompassing ‘music industry’, we consider a plurality of music industries. Williamson and Cloonan state two primary issues with the use of a singular ‘music industry’: that the reality is ‘disparate industries with some common interest’ (2006, 305) and a conflation of ‘music industry’ with the recording industry. We would now argue 17 years later that less conflation exists between ‘the music industry’ and the recording industry, as the rise of the economic importance of live performances and growing interest in night-time economies has shifted policy focus from recorded music to live performances. This was put in stark relief by the COVID crisis which caused overnight cancellations and extended shutdowns of all live music performances in much of the developed world. While a taxonomy of music industries is beyond the scope of this paper, for this research, we have primarily considered the industries impacted most by COVID policy measures – namely the live music industry (those making and doing music for live performance), the live music business (those involved with the buying and selling of live performances such as venue owners, promoters, etc.), ancillary workers (hospitality staff, live sound engineers, lighting technicians, etc.), and the recording industry/recording business (musicians writing and recording for public release and the studio owners/staff supporting these recordings). Further, each of these industries exist at multiple levels and scales – from a grassroots level consisting of local bands and artists self-promoting shows at 100 cap rooms to larger interstate and international touring networks with far higher economic value. We use the ‘just city’ perspective to ask if the policy measures designed to financially support the COVID-19 lockdowns demonstrate public investments and regulations being used to produce equitable outcomes for those working in these music industries. From a ‘just city’ framework, we put forward a position that argues for a COVID-19 recovery that incorporates policy innovations motivated by equitable economic and social outcomes. The model of the ‘Just City’ emerged after the 1960s, when scholars of urban politics denunciated ‘policies that exacerbated the disadvantages suffered by low-income, female, gay, and minority residents’ (Fainstein Citation2010, 3). The model of the ‘just city’ aims at achieving a city ‘in which public investment and regulation would produce equitable outcomes rather than support those already well off’ (Fainstein Citation2010, 3). The recent COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to examine if the music industries of Brisbane and greater South-East Queensland (SEQ) are considered fairly from this perspective.

The first section of the article is a review of the literature on the impact of COVID-19 on the broader arts industry, with specific attention paid to how COVID-19 affected the music industries. The second part outlines methods, methodology, and context of this work, and the third part discusses the results of this research.

2. Literature review

With the global pandemic only starting in early 2020, at the time of writing COVID-19 research, only has several years of literature from which to draw upon. Nevertheless, as COVID-19 has been in many ways the most disruptive global health crisis since the influenza A pandemic of 1918–1920, scholars from a range of disciplines have had to contend with the effects of the pandemic. Music, the arts and culture more broadly, are no exception. Indeed, with the arts sector, one of the worst affected in terms of lockdowns and COVID-19 prevention measures affecting normal operation, arts and culture scholarship has been essential in understanding and mapping the sheer scale of the disorder that those investigating or working in these industries have experienced.

For the purposes of this research, the literature reviewed here is a mix of studies specifically on music industries and economies, and studies on the arts and cultural sector more generally. In the literature surveyed, some key themes emerged. In a time of crisis, the role of government and the efficacy and equity of policy interventions as pertaining to arts and culture have been examined across the world, including Germany (Duemcke Citation2021), a series of medium-sized European countries such as the Czech Republic (Betzler et al. Citation2021), Australia (Pacella, Luckman, and O’Connor Citation2021b), Nigeria (Butete Citation2022), Argentina and South America (Szrafini and Novosel Citation2021), and the UK (Banks and O’Connor Citation2021). Planning and policy decisions made by governments to support arts and cultural workers furloughed due to COVID lockdown measures tended to reflect existing and prior relationships with the arts sector, ranging from the arts being broadly appreciated and valued (both socially and financially) in places like Germany (Duemcke Citation2021) and New Zealand (Pacella, Luckman, and O’Connor Citation2021b), to having strained relationships with federal governments that were slower to provide support and/or provided only limited support, such as countries like Australia (Pacella, Luckman, and O’Connor Citation2021b) and the UK (Banks Citation2020).

Urban planners have an influence on music scenes because as stated by Burke and Schmidt (Citation2013, 69): ‘there are relationships between noise levels, sleep disturbance and human health’. Planning as a discipline emerged in the nineteenth century to resolve health issues in the industrial city and as Burke and Schmidt (Citation2013, 69) pointed out: ‘there is a long tradition in planning related to public health interventions’. If Jane Jacobs and Lewis Mumford are known for criticising planners who allegedly destroyed vibrant urban neighbourhoods, urban planning has ostensibly been more in favour of the arts following the success of Richard Florida’s work which highlighted the economic value of ‘creativity’ in the urban context (Citation2005). Florida’s ‘creative class’ highlighted urban planning’s role in shaping local urban policies in a context of economic competitiveness between post-industrial cities moving towards service-based economies. As a result, as stated by Van Derhoeven and Hitters (2019, 264), there has been an instrumentalisation of culture in urban policies. Culture for instance is often used in urban regeneration strategies as a way to create a cosmopolitan image in a context where cities are competing with each other (Van der Hoeven and Hitters Citation2019, 264). The fact that Florida’s definition of the creative class serves a neo-liberal agenda has been made in numerous urban studies works (see Wilson and Keil Citation2008 on the fact that the creative class is class-biased and a capital privileging notion).

In the Brisbane context, an example of urban planning’s influence on the music scene can be found in the Fortitude Valley entertainment special area, a design and planning intervention to ‘manage the impacts of music noise upon residents and businesses in an integrated way, without compromising the viability of the music-based entertainment industry in the Valley or the vibrancy of the Valley’ (BCC Citation2002, 4). Economically, the plan also ‘promotes and enhances the Valley as a valuable incubator for the development of original live music of all types and styles’.

With the live music industry the focal point of the policy, the Valley Music Harmony Plan has been a success over the past two decades, with Fortitude Valley the home of a growing number of live music venues that offer both economic and sociocultural benefits to the city.

This has faced existential threats as a result of policy measures introduced to combat the COVID-19 health crisis. In Australia, the antipathy and sometimes outright hostility towards the arts showed by the federal government presiding over the pandemic was keenly felt by those in the cultural sector; particularly working musicians whose economic lifeline of live performance was one of the first to be cut-off by pandemic measures and one of the last areas to reopen. This antipathy has been noted by researchers, with Pacella, Luckman, and O’Connor (Citation2021b) arguing that the federal government was pursuing a ‘counter-culture policy strategy rather than a culture strategy’ (47–48). Having delayed announcing financial support packages for several months into the pandemic, the delivery of Australian federal government’s $250 million package in June 2020 (months after lockdowns were mandated) was then delayed by several more months, leaving many in the industry in very precarious financial territory (Eltham Citation2013). The theme of precarity is evident across much of the research examining COVID-19 policy and planning across the broader arts sector (Banks Citation2020; Comunian and England Citation2020; Eikhof Citation2020; Szrafini and Novosel Citation2021), and specifically the music industry (Agamennone, Palma, and Sarno Citation2023; Morrow, Nordgård, and Tschmuck Citation2022). In particular, live music economies have faced existential risks around the world (Brandel Citation2021; Gu, Domer, and O’Connor Citation2021) with the sudden closures of music venues leading to a loss of both income streams and purpose in the lives of many musicians.

Brisbane and SEQ may have escaped the same level of disruptive lockdowns Melbourne suffered, though while the QLD state government exhibited a greater sense of empathy for the arts when compared with their federal counterparts, the local music industries nevertheless faced existential threats. Many of those in Brisbane’s music scene were disappointed by the initial government support measures (Brown Citation2021; Gramenz Citation2021; Hammond Citation2021). Research by Carfoot (Citation2021) shed light on the disruptions caused by interstate lockdowns on touring musicians based in Melbourne and Brisbane, particularly the effects of extended quarantine times on those who were also balancing the care of a young family. The existential crisis faced by those in the live music industry led to a series of venue owners and industry figures banding together to form ‘Play Fair’ to advocate for additional support for live music venues (Eliezer Citation2021; Moore Citation2021). Led by John Collins, the advocacy group was able to secure emergency funding from the QLD state government to support local ticketed live music venues (Bryan Citation2021).

To maintain engagement with existing audiences, build new audiences, and attempt to monetise creative outputs, many musicians turned to online platforms for live streaming. There was little alternative – as Banks puts it at the time: ‘The home … has become, by state decree, the prescribed option for all cultural activity’ (2020, 649). Music scenes with existing online communities, typically based around pre-existing social media platforms, were better prepared for the shift to online (Quader Citation2022) and, as per Agamennone et al (2023, 5), a key aspect of the pandemic’s effects on music was the ‘unprecedented extent to which social media (and mediatised environments and products more generally) constituted the key, and almost sole, site and paradigm of musicking’. While the techno-utopians may have argued for a Web 3.0 future of greater equity and self-determination, a shift to online spaces instead may have further consolidated the tech company monopolies (Banks Citation2020; Gu, Domer, and O’Connor Citation2021) in a way that Giblin and Doctorow have termed ‘Chokepoint Capitalism’ (Citation2022).

Seeing the pandemic as an opportunity to build new digital futures may be commendable, but research has highlighted the importance of maintaining recognition of the vital role music venues play in the live music ecology of a country or city, and the existential risk COVID-19 has posed to those involved in the live music industry (Brandel Citation2021; Gu, Domer, and O’Connor Citation2021). It is in this sector that urban planning and policy has had the greatest impact as the new field of music cities research has led to music being supported and regulated by governing bodies to help develop strong night-time economies as well as used as a rhetorical device to help foster a ‘creative cities’ image (see Ballico and Watson Citation2020).

2020). Whilst some early examples of urban policy geared towards growing and sustaining a post-industrial creative industries-based economy may have identified the recorded music industry as a sector that would benefit from state funding (e.g., Sheffield, UK, in Brown, O’Connor, and Cohen Citation2000; Moss Citation2002), urban policy and planning post-2000 has shifted attention to the live music industry as the locus of music in the urban domain (Behr, Brennan, and Cloonan Citation2014; Burke and Schmidt Citation2013; Homan Citation2014; Van der Hoeven and Hitters Citation2019).

For emerging artists and music markets, live music venues are essential not only for the financial returns afforded to artists and industry players, but also as spaces for exchange and community (Gu, Domer, and O’Connor Citation2021). An international comparative research project by Howard, Bennett, Green, Guerra, Sousa, and Sofija argued that while COVID lockdowns may have resulted in some ingenious DIY solutions, ‘the longer-term impacts on the music industry mean that young people’s livelihoods and education will be impacted for many years to come’ (Citation2021, 418). Further, an argument has been made in cultural scholarship that many of the industries associated with the arts were not in particularly good health to being with. In arguing for a more multi-faceted understanding of the value(s) of live music and live music venues, Van der Hoeven and Hitters (Citation2019) provide examples of exactly how precarious live music ecologies were before the COVID-19 pandemic. This theme is by no means isolated to music, with Comunian and England (Citation2020) investigating whether the COVID-19 pandemic is a moment of crisis or just an event that has exposed existing unsustainable practices across the wider arts and cultural sectors.

In Brisbane and greater SEQ, inconsistencies in policy and planning responses to the music industries and business impacted by COVID-19 have called into question how policymakers value the arts (Brandel Citation2021). This is another common theme across much of the literature investigating COVID-19’s effects on the arts and cultural industries (Banks and O’Connor Citation2021; Harper Citation2020; Meyrick and Barnett Citation2021). As Banks and O’Connor argue:

For what this crisis is illuminating, in all-too-lurid detail, is how we think about and value art and culture; how we argue for their importance; how governments and public policy actors understand and value them, what they are prepared to do, on what grounds and with what capacity. (Citation2020, 3)

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in a clarion call for new approaches to policy and workforce support that values those working in arts and culture industries, this is evident in Brisbane’s local music industry (Brandel Citation2021), as well as research that has argued that COVID-19 has provided an opportunity for the arts to more broadly argue for a ‘new deal’ with government (Banks and O’Connor Citation2021; Comunian and England Citation2020; Meyrick and Barnett Citation2021; Pratt Citation2020). Policy and fairness feature as defining components of Fainstein’s ‘just city’, and in the following sections, we examine how the policy and planning responses of the Australian Federal government and Queensland State government as they pertain to local music industries can be considered from Fainstein’s (Citation2010) three pillars of diversity, democracy, and equity.

3. Context and methods

Brisbane’s music scenes for a long-time functioned as underground ecosystems fighting to survive attacks from a repressive and ultra-conservative government led by Bjelke-Petersen (Stafford Citation2014), who ruled the State for almost 20 years between 1968 and 1987. This period saw the tearing down of precious inner-city music venues and direct physical attacks on the participants of the local music scenes by the police force (Willsteed Citation2019). Members of the local music subcultures were sometimes arrested without any valid reason just because they did not have the ‘right’ haircut and looks. A change to a centre-left state government in 1989, along with the burgeoning grunge movement of the 1990s saw the relationship between state power and local music industry begin to thaw, as the commercial success of bands such as powderfinger, Regurgitator, and Custard, as well as more pop-orientated counterparts such as Savage Garden and the Veronicas led local and state governments to increasingly recognise the economic importance of planning and policy that would ensure the viability of the live music industry. Most of Brisbane’s music venues are now concentrated in the Fortitude Valley precinct, and compared to Melbourne, where the venues are more diffused throughout the city (Burke and Schmidt Citation2013), the density of music venues in the Valley special entertainment area is one of the highest in the world. Whilst many of these venues began life either well before the gentrification of the valley began in the late 1990s, or at approximately the same time (with venues such as the Zoo, the Beat, Ric’s café, the Tivoli, and the Troubadour/Black Bear Lodge all dating back to 2003 or earlier), the residential development surrounding the inner-city suburb of Fortitude Valley necessitated local and state government intervention and planning to ensure the feasibility and sustainability of music venues (Burke and Schmidt Citation2013, 69). In Brisbane’s case, the government’s response was to recognise the vital importance of the valley’s ‘unique and vibrant atmosphere, and its thriving live music, nightclub and arts scenes’ to develop the ‘Valley Music Harmony Plan’ in 2004 (Brisbane City Council Information Citation2002). This plan recognises a designated area as a ‘special entertainment area’ which then requires all new developments to attenuate noise, in addition to subjecting the venues to certain noise limits. Implemented ten years earlier than Melbourne’s ‘agent of change’ policy, Homan (Citation2014) notes that the aim of the Valley Entertainment Precinct was to protect and support venues in a concentrated area, which has resulted in the distribution of venues across the different Brisbane suburbs becoming distorted. Melbourne’s ‘agent of change’ policy, implemented in 2014 in response to the SLAM (Save Live Australian Music) rallies is instead designed to shift the burden of soundproofing to the party creating change, which, while doing a good job of protecting existing dispersed music venues from encroaching residential development, creates a great degree of difficulty for any agents interested in developing new live music venues. Regardless of the exact policy details, the point here is that in both Brisbane and Melbourne local and state governments recognised the vital social, cultural, and economic benefits of live music and responded with policies that served to protect those involved in the local live music industries and businesses from the threat of inner-city gentrification. The purpose of the interviews and surveys we have conducted as a part of this research serve to examine whether the policy responses to the recent COVID-19 crisis have been sufficient to protect local industry from the existential threat posed by the pandemic, and how aligned these pandemic policies have been with Fainstein’s ‘just city’ framework.

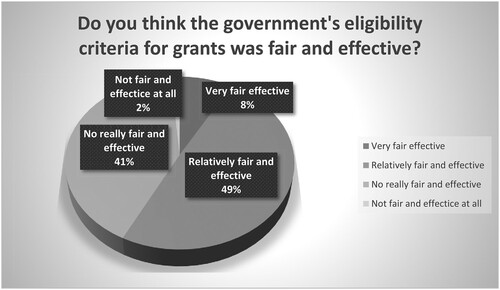

For music industry workers in SEQ adversely affected by federal and state government COVID lockdown measures, various grants and funding initiatives were made available over the course of 2020/2021. The federal government’s initial policy was to add a $150 per fortnight ‘coronavirus supplement’ to the jobseeker unemployment benefit and to create a ‘jobkeeper’ scheme paid to businesses affected by COVID-19 in order to help them keep staff on the payroll. While the jobkeeper payment was effective in supporting music industry workers already on the payrolls of larger venues or recording studios, much of the grassroots level of Australia’s local music industries was not made up of businesses large enough to qualify for such support. While the federal government’s ‘Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand’ (RISE) fund went some in providing security for various festivals and arts organisations across the country, questions were raised when it was revealed that the then arts minister would personally award funding rather than approving grants via a more impartial body such as the Australia Council (Miller Citation2021). When $750,000 was allocated to support the national tour of veteran US-based rock n’roll band Guns n’Roses and close to $1.5 million was spent on a national tour of giant lego dinosaurs there was a perception by many in the various arts industries that government planning was again privileging commercial interests over policies that would benefit arts workers on casual contracts and with inconsistent hours of work (Miller Citation2021). Meanwhile, the federal government’s ‘Arts Sustainability Fund’ was almost exclusively used to support classical music and opera – sectors featuring less insecure casual employment and inconsistent employment patterns in comparison with the vernacular music industries. The QLD state government offered more targeted support to the music industries, with the ‘Live Music Support Program’ offering $11 million to support 37 live music venues over the course of 2021 (Editor Citation2021). Similar to the federal government initiative, this funding was primarily aimed at supporting the business owners and staff of the live music venues, not the musicians who perform in them. For those individuals making up the productive cohort of live performers, QLD’s music industry development organisation, QMusic, partnered with the QLD government to award grants of $3000 to individual applicants. With only $500,000 allocated to this initiative, from a ‘just city’ perspective it seems apparent that, per Fainstein’s (Citation2010) claims that urban planning currently privileges the protection of neoliberal orthodoxy, most COVID policy responses to those in the arts were guided by economic over social principles.

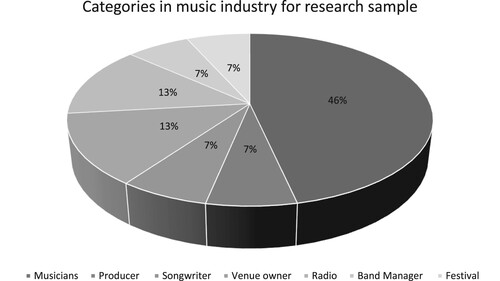

To determine how these policy responses were perceived by a range of music industry workers and venue owners, we performed an on-line survey and reached 18 respondents. While this may represent a small sample, it gives us an indication of the impact of the pandemic on working practices and access to policy support. We tried to promote the survey through different social media to get more respondents, but it is likely that musicians experienced a degree of ‘fatigue’ about being surveyed on the impacts of COVID-19. Our sample for the on-line survey was made mostly of musicians but also other categories in the music industry were considered such as band managers, producers, venue owners and festival and live events organisers (See ).

The on-line survey included multiple-choice questions on different topics (impact of the pandemic on work/working from home/organising on-line events/music production and audience engagement/access to support/fairness of the process/post-COVID changes to the industry). The survey also allowed respondents to provide qualitative comments following the multiple-choice questions.

In part due to the small sample size of the online-survey, and in part to gather more detailed information on the effects of QLD’s policy responses on Brisbane and greater SEQ’s music industries, we then contacted several industry workers directly to conduct interviews. The questions for these semi-structured interviews were similar to the on-line survey but we adapted them depending on the interviewee being a musician, a venue owner, or other industry worker. We have used this mixed methods approach (an on-line questionnaire and semi-structured interviews) to better validate our results. Mixed-methods are efficient and are based on the triangulation principle. Triangulation enhances confidence in the validity of findings (Somekh and Lewin Citation2005, 274).

4. Results

In this section, we reflect on the results from the on-line survey and semi-structured in-person interviews. The main aims of the survey were to gather details on the impact of the pandemic on the work of music industry professionals, to investigate the ease of access to government support, and to gauge perceptions around the equity of the policy responses to the pandemic.

4.1 Impact on music practices

Despite the overnight closure of all live music venues and the cancellation of countless shows and tours, musicians carried on making music of some kind during the pandemic with 92% and 75% investing time in performing music on-line or organising an on-line event. The majority of these events were not financially successful, with only 12% of respondents considering their on-line event to be financially successful.

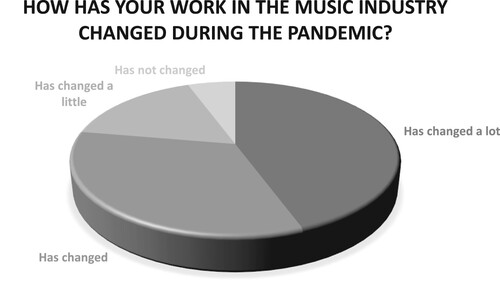

As . below shows, the impact of the pandemic on music industry work has been significant, with work during the pandemic either changing or changing a lot for 77% of the sample. This serves to highlight the importance of live music venues and in-person interactions for many musicians – while certain industry practices such as music production and composition for film, TV, and gaming may have continued relatively unchanged over the course of the pandemic, other parts of the industry such as working bands, performing musicians, live music venues, and recording studios that had to contend with lockdowns and capacity restrictions were forced to radically shift their perceptions of what music industry work was still possible.

Figure 2. Impact of COVID-19 on work practices in Music industry for our sample. Source: Our research.

Our research shows that only 30% of the sample looked for additional work within the music industry and 48% of the sample had to look for work outside the music industry. The impact was mostly due to the cancellation of live events, with 95% of the sample having to cancel/reschedule a live show, often several times. Data from the Australian Rights Performance Association (APRA) support this figure, with the collection agency recording a 90% drop in setlists performed between the 2019 financial year and 2020 financial year. Further, fewer than 1/5th of APRA members who received royalties in FY2019 also received payments in FY2020. In addition to the collapse of the local industry, uncertainty around the sudden implementation of lockdowns, venue closures, and border closures led to touring artists unable to plan in any meaningful way.

4.2 Government assistance and support

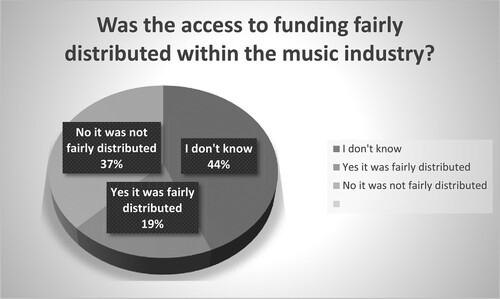

Our on-line survey revealed that 71% of workers from the music industry considered that the access to funding for the music industry compared to other industries was either not fair or not fair at all. Some of our respondents thought there was a bias towards sports and gambling:

[Sport/Gambling industry] seemed to be offered greater leniency compared to other industries … I still struggle to see how we could have full stadiums for sport and huge restrictions for music venues and festivals. (Written comments from on-line survey)

The music industry is/was the first to step in and assist in crisis, but the absolute last to benefit. The mandatory vaccine rules that were in place way longer than required caused great stress for artists, crew and patrons … It was good that there was ‘some’ financial support but considering the music industry was the first to go and last to come back into any action, there’s definitely more support that could’ve been provided. (Written comments from on-line survey)

You know, there were huge sporting events and just no, no gigs. You were allowed to cheer but you weren’t allowed to sing. It was very weird. Obviously, only a cynic would draw to conclusions, but the government has got so much more money, wrapped up gambling in sporting events. (Pers. Comm., July 2023)

So, my thinking was we operate at percentages that you’ve indicated to us. It doesn’t work. And I saw that you could sit next to each other and play or rub shoulders at a football game, but you can’t do it at music venues. So, I always struggled with that. I met with Dr. Young and she was very adamant that’s the way she wanted to keep things. So my point to her and the Premier’s office with Arts Queensland was ‘if you want us to do this, if you want us to keep people safe at out venues and lose money, you have to give us some money to keeps this alive’. That was the thing. You either, open up the capacity to 50% where we would probably survive, we were never talking about going to full stadium, full shows. We were talking about if you gave us 50% capacity, we could probably get through this. It makes it work for bands, we’re not making money, but we can survive and that was one thing. If you don’t give us that, you have to fund us because … You were telling us how to run our business and its dramatically affecting out viability and you’re not subsidising this. That was my argument. You had one choice government: give us better capacity or pay for it. (Pers. Comm., July 2023)

Well, the state government came to the party. I received funding for both venues, and I actually worked with Arts Queensland on that and how it was fairly allocated. Some of the approach was about ticketed venues. If you were just a pub in a back room, you suddenly couldn’t say you were at ticketed venue. It had to be people who traded as ticketed venues and the funding was linked to capacity. It was the only way that I could see it work – like my rent at Fortitude is going to be a lot higher than the Zoo and my rent will be affected by my capacity. (Pers. Comm., July 2023)

Big labels, promoters and festivals obviously took big hits but also got even bigger payouts. For example: the Guns n Roses tour didn’t need any government funding … huge chunks of cash went to international tours & promoters. (Written comments from the on-line survey)

We heard about funding to venues well after it was allocated. We understood that meetings had occurred via QMusic, but we were not in the conversation … I don’t think the small venues who needed assistance were given as much as they needed. (Written comments from the on-line survey)

Issues about communication have been noted by our respondents in the on-line survey and about the fact that small local bands might not have benefited from the same support as other parts of the live music industry:

Having more support for local bands, I heard there was support for venues, booking agents and managers although more support could’ve been provided to local bands. (Written comments from the on-line survey)

I think the support that was offered to people who were within the industry varied, because some people [sound persons] were let’s say going to venues maybe four times a week, doing sound and I think that those people were probably affected the most because … I don’t think that the government support packages would have supplied fair payment for their work. But I think along the field of musicians within the industry it would have varied, and I think that some would have commensurate the loss caused by mandated lockdowns but others, not so much. (Thompson, Pers. Comm. April 6th 2023)

4.3 What could be improved – policy innovations

The pandemic revealed that more policy efforts could be put into the distinction between jobs in the music industry as explained below by Wilson:

There’s a whole section of people who just instantly lose work. And it’s not just people who are performers but people who generally are less valued, but there’s also like engineers and people you consider in more traditional jobs actually work in the industry. Maybe there is a need for more recognition as to what and what is a job or what isn’t a job when they go through that kind of event. [so support is more targeted]. (Pers. Comm, June 2023)

I think it is definitely a trigger for something new … . But, I can’t really name a policy, like I know in France they have that artists payout every month or so if you have a minimum amount of gigs but I don’t know how that’s going to work if we do have another pandemic, because if it’s based number of gigs then nobody is going to have gig. So, I can’t really describe something like it but I think COVID did teach each government something about the arts that needs to happen just in case something like this happens again. (Tam, Pers. Comm. April 25th, 2023)

Oh, God. If things like this happen in the future I’m packing up, I’m gone. Look, I don’t know … I hope to think the government would treat it differently, you know, and maybe be a bit more consistent with what happened with sport and racing for the industry (music industry). I think consultation is a key. Anything you do, consultation. Honestly, it was up to me to go to the state government who are running the rules for the COVID. It was up to me to go to them and sort of get them to sort of get them to the table. I think, honestly, there should have been, we’ll just go ‘Where do you fit? Where do you see yourselves? What can we do?’ That’s a policy I would like to see included, where they come to us before they make these rules, and we have to explain how, how hard they are. (Pers. Comm. July, 2023)

I think COVID sort of proved that we’re not an organised bunch of people. You know, I think that really shined through. You know look at sports, the racing industry and how they handled it. Yeah, I think they highlighted how much better we could be organised as an industry and have these bodies that can talk to government. (Pers. Comm. July, 2023)

I think the Brisbane scene is fantastic. I think it’s one of the best in like compared to Melbourne or Sydney. Perth has a great scene. Adelaide is alright. Sydney is pretty disparate. Melbourne is good. But Brisbane is the best by a country mile. All the venues in the Fortitude Valley precinct are certified. I know Qmusic gets a lot of funding. And they do a lot of good stuff for Brisbane. (Wilson, Pers Comm. June 2023)

5. Conclusion

Three key themes emerge from our research. First, there was a clear perceived lack of consistency in the support received by the music industry from all levels of government. While the QLD state government eventually brought in measures to protect the viability of the local live music venues and their workers, the lack of consistent social distancing and lockdown measures between sports venues and arts venues was seen by many of our survey and interview respondents as problematic. Further, when funding did arrive, it tended to favour the big end of town such as larger venues and booking agents/promoters working on international acts doing stadium tours rather than the local grassroots live music industry. Second, in order to better understand the effects of policy and planning on industry, a greater degree of government consultation is required. Governments need to understand the existential risks faced by industry workers following mandated quarantine and lock-down measures and support them accordingly. As pointed out by Australian band Tired Lion in a tweet ‘Musicians, artists/people in the industry are always the first called upon whenever there is a fundraiser for crisis relief (bushfires etc.) but get treated like this’ (in Brown Citation2021). There seems little doubt that governments are happy to be associated with the vibrant night-time economies and tourism associated with healthy live music scenes, but a lack of consultation in policy responses such as those seen in the COVID-19 jeopardise the viability of these vital industries. Third, the various music industries need to find ways in which greater industry collectiveness can be achieved to improve advocacy efforts and to ensure there’s a seat at the table if similar disruptive events occur again in the future. The local live music industries and recording studio industries are fractured and form a disparate collection of small-business owner/operators, self-employed artists, and larger venue owners/directors overseeing a number of full-time and part-time staff. There are also grey areas between professional, semi-professional, and quasi-professional members of these music industries. This makes it difficult to get representation from all of those with livelihoods impacted by quarantine and lock-down measures. While not-for-profits like Arts Queensland and QMusic were able to collaborate with industry figures and policy-makers to secure emergency funding and worked extremely hard to secure and distribute funding in as equitable fashion as possible, they lack the resources of the larger, seemingly more consolidated gaming and sports industries. Further collective organisation by a selection of musicians, industry figures, and venue directors that make up a representative cross-section of local industry would be helpful in developing clear communication channels with government in future disruptive events.

In terms of Fainstein’s concept of the ‘just city’ and policy responses, the COVID-19 pandemic clearly presented a series of challenges to all levels of government that were unprecedented in modern times. Whilst several of our survey and interview subjects expressed frustration with some policy responses, in particular questioning the consistency of lockdown policy responses in relation to industries that received support measures that they perceived as more favourable, most music industry workers also acknowledged the difficulties governments faced developing policies on the fly to keep citizens safe from a global pandemic. In terms of this pandemic as a disruptive event, writing from a position of relative normality that seemed impossible during the lockdowns and quarantines of just three years ago, there are clear opportunities to use urban planning to improve the equity of support offered to music industry workers (and arts/cultural works more broadly) in the event of future disruptions. Our results indicate that place-based cultural policies continue to follow a neo-liberal agenda and music scenes and the live music industry seem to be more appreciated for their financial value than for their social and cultural contribution to society. The reaction of governments in Australia and in Brisbane to COVID-19 reflects this stance. If planning is more on the side of arts and music when it comes to the regulation of nightlife (see Rose Citation2023, regarding new protections for live venues in NSW), the driver is still the economy. Thus, neither Mumford’s nor Jacob’s vision of the cultural city is yet achieved.

In both the recorded and live industries and markets, the cost-of-living crisis that has followed the coronavirus pandemic, alongside growing trends towards the use of AI in music production and composition (see Eltham Citation2013), points towards further turbulent times for those involved in these music industries. Whilst targeted music-specific urban planning has been key in protecting some live music industries and markets, it is also true that policies seemingly unrelated to music, such as regulations on licensing laws, noise pollution, and urban planning and zoning laws, have had vast repercussions on the horizon of possibilities available to the music makers (Sutherland Citation2013). From our research, we see that having access to time and resources created opportunities for recording, streaming (both live and recorded outputs), and other business activity such as selling merchandise for many of those Brisbane’s music community. In a sense, the deleterious effects of the sudden unavailability of live performance were somewhat offset by the availability of time and (even if in many cases relatively meagre) resources to create freely. For the security and sustainability of those in the arts, planning and policy that provide those in music and the arts a platform from which to create – i.e. the provision of time, availability of resources, and access to space – are key. The sense of precarity felt by those involved in allocating the time and energy to develop enough talent to pursue a career in music was evident in several of our survey and interview responses and reinforces the literature we surveyed for this study. Initiatives such as Ireland’s provision of a universal basic income to musicians (see Marshall Citation2023) could prove useful in maintaining the kind of workforce key to sustaining a cultural economy. Urban planning based on providing affordable housing, particularly initiatives targeted at musicians and other arts workers such as Nashville’s ‘Ryman Lofts’ (Nicholson Citation2013), would align well with the ‘just city concept to create more equitable outcomes for citizens. Our interview data supports our literature research findings stating that those in the arts frequently feel undervalued and under-represented by government bodies and policy-makers – a theme that recurred several times in our responses was that those in music industries are frequently the first to help respond to nation crises such as floods, bushfires, tidal waves, etc., but were left to fend for themselves when faced with an existential threat. Greater collectiveness would aid in advocacy for more consistent government policy responses, with policymakers and urban planners also able to better consult with music industries to ensure the viability and sustainability of industries essential to Brisbane and SEQ’s vital night-time economies.

Semi-structured interviews

Interview 1: Stephen Stockwell, 4ZZZ Station manager, May 19th 2022.

Interview 2: Ursula Collie (musician), Ironing Music, July 5th 2022

Interview 3: Richard Warman, Alternative night club organiser, November 10th 2022

Interview 4: Zaac Thompson, Nonberk. April 6th 2023.

Interview 5: Nicholas Tam (musician), April 25th 2023

Interview 6: Lachlan Byron, Independent Musician, May 25th 2023.

Interview 7: Alex Wilson, Director and Head of Distribution at GYROstream and band member of Shag Rock, June 2023.

Interview 8: Ian Haug, Owner Airlock Studios, current band member of The Church, and former band member of powderfinger. July 2023.

Interview 9: John Collins, Venue Director at the Fortitude Music Hall and the Triffid, and former band member of powderfinger. July 2023.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Jade Schroeter, Jonathan Virgona as well as Dr. John Willsteed for their contribution to the data collection. The authors also would like to thank all the workers from the Brisbane music industries who fulfilled the questionnaire and accepted to do one to one interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Artists and technicians in the creative industries (theatre, music, cinema) in France can benefit of a monthly government subsidy when they become out of work given that they have accumulated a given amount of work hours in the Arts the previous year.

References

- Agamennone, M., D. Palma, and G. Sarno. 2023. Sounds of the Pandemic: Accounts, Experiences, Perspectives in Times of COVID-19, edited by M. Agamennone, D. Palma, and G. Sarno. London, NY: Routledge.

- Baker, A. 2017. “Algorithms to Assess Music Cities.” SAGE Open 7 (1), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017691801.

- Ballico, C., and A. Watson. 2020. Music Cities: Evaluating a Global Cultural Policy Concept. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Banks, M. 2020. “The Work of Culture and C-19.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549420924687.

- Banks, M., and J. O’Connor. 2021. ““A Plague upon Your Howling”: Art and Culture in the Viral Emergency.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1827931.

- Behr, A., M. Brennan, and M. Cloonan. 2016. “Cultural Value and Cultural Policy: Some Evidence from the World of Live Music.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 22 (3): 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2014.987668.

- Betzler, D., E. Loots, M. Prokůpek, L. Marques, and P. Grafenauer. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Arts and Cultural Sectors: Investigating Countries’ Contextual Factors and Early Policy Measures.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (6): 796–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1842383.

- Brandel, P. 2021. “Live Music COVID Restrictions Causing Confusion: Why Can Queenslanders Go to the Footy in Their Thousands but Can’t Go to See Their Favourite Band at Their Local Venue?” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, May 14, 2021. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-14/covid-venue-restrictions-confusion-music-venues-and-football/100136900.

- Brisbane City Council. 2002. Valley Harmony Plan. Brisbane.

- Brown, P. 2021. “Brisbane, This Is a Callout to Ditch the Double Standards Against the Music Industry!” Wall of Sound, July 23, 2021. Available online at: https://wallofsoundau.com/2021/07/23/brisbane-this-is-a-callout-to-ditch-the-double-standards-against-the-music-industry/.

- Brown, Adam, Justin O’Connor, and Sara Cohen. 2000. “Local Music Policies Within a Global Music Industry: Cultural Quarters in Manchester and Sheffield.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 31 (4): 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(00)00007-5.

- Bryan, A. 2021 September. “Smaller Live Music Venues in Qld Receive COVID Funding Relief.” Australian Hotelier, September 3, 2021. Available online at: https://theshout.com.au/australian-hotelier/smaller-qld-live-music-venues-receive-covid-funding-relief/.

- Burke, M., and A. Schmidt. 2013. “How Should We Plan and Regulate Live Music in Australian Cities? Learnings from Brisbane.” Australian Planner 50 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2012.722556.

- Butete, V. 2022. “Social ‘Capitalising’ the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Portrait of Three Zimbabwean Female Musicians.” In Rethinking the Music Business Music Contexts, Rights, Data, and COVID-19, edited by G. Morrow, D. Nordgård, and P. Tschmuck, 73–89. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Cai, Carrie J., Michelle Carney, Nida Zada, and Michael Terry. 2021. “Breakdowns and Breakthroughs: Observing Musicians Responses to the COVID19 Pandemic.” In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’21), May 8–13, 2021, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York, NY, USA.

- Carfoot, G. 2021. “‘It Was COVID-19’.” Perfect Beat 21 (1-2): 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1558/prbt.19348.

- Comunian, R., and L. England. 2020. “Creative and Cultural Work Without Filters: COVID-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy.” Cultural Trends 29 (2): 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577.

- Darchen, S., J. Willsteed, and Y. Browning. 2023. “The “Music City” Paradigm and its Policy Side: A Focus on Brisbane and Melbourne.” Cultural Trends 32 (3): 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2062565.

- Duemcke, C. 2021. “Five Months Under COVID-19 in the Cultural Sector: A German Perspective.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1854036.

- Editor. 2021. “Minister Leeanne Enoch Announces Investment to Secure Jobs and Sustain the Arts.” Aussie Theatre, 18 November 2021. https://www.aussietheatre.com.au/news/minister-leeanne-enoch-announces-investment-to-secure-jobs-and-sustain-the-arts.

- Eikhof, D. R. 2020. “COVID-19, Inclusion and Workforce Diversity in the Cultural Economy: What Now, What Next?” Cultural Trends 29 (3): 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1802202.

- Eliezer, C. 2021. “Brisbane Live Sector Meeting with Government as City Slams Shut.” The Music Network, March 30, 2021. Available online at: https://themusicnetwork.com/brisbane-snap-lockdown-music/.

- Eltham, B. 2013. “Welcome to ‘the Robot Soundscape’: Australia’s Music Industry Braces for the Rise of Music AI”. The Guardian, September 8, 2021. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/sep/08/ai-music-bigsound-brisbane-ai-dj-spotify-beatles.

- Fainstein, S. S. 2010. The Just City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Florida, R. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. London, New York: Routledge.

- Giblin, R., and C.Corey Doctorow. 2022. Chokepoint Capitalism. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

- Gramenz, E. 2021. “With Live Music Struggling due to COVID-19, Is Australia Losing Its Soundtrack?” ABC News, August 28, 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-28/qld-covid-music-industry-struggles-amid-pandemic-shutdowns/100403690.

- Gu, X., N. Domer, and J. O’Connor. 2021. “The Next Normal: Chinese Indie Music in a Post-COVID China.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1846122.

- Hammond, N. 2021. “Live Music In Brisbane Feels the Brunt of Covid Restrictions.” Westender Community News, July 13, 2021. Available online at: https://westender.com.au/live-music-in-brisbane-feels-brunt-of-covid-restrictions/.

- Harper, G. 2020. “Creative Industries Beyond COVID-19.” Creative Industries Journal 13 (2): 93–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2020.1795592.

- Homan, S. 2014. “Liveability and Creativity: The Case for Melbourne Music Precincts.” City, Culture and Society 5 (3): 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2014.06.002.

- Howard, F., F. Bennett, B. Green, P. Guerra, S. Sousa, and E. Sofija. 2021. “‘It’s Turned Me from a Professional to a ‘Bedroom DJ’ Once Again’: COVID-19 and New Forms of Inequality for Young Music-Makers.” Young (Stockholm, Sweden) 29 (4): 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308821998542.

- Marshall, A. 2023. “Ireland Asks: What if Artists Could Ditch Their Day Jobs?”. The New York Times. March 23, 2023. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/23/arts/ireland-basic-income-artists.html.

- Meyrick, J., and T. Barnett. 2021. “From Public Good to Public Value: Arts and Culture in a Time of Crisis.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1844542.

- Miller, N. 2021. “A Giant, Unplanned Experiment’: The Winners and Losers in Arts Funding.” The Sydney Morning Herald, December 19, 2021.

- Montgomery, J. 2004. “Cultural Quarters as Mechanisms for Urban Regeneration. Part 2: A Review of Four Cultural Quarters in the UK, Ireland and Australia.” Planning Practice and Research 19 (1): 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269745042000246559.

- Moore, T. 2021. Music Identities to Meet with Qld Government to Push New Crowds Campaign. The Sydney Morning Herald, March 27, 2021. Available online at: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/music/music-identities-to-meet-with-qld-government-to-push-new-crowds-campaign-20210325-p57dzb.html.

- Morrow, G., D. Nordgård, and P. Tschmuck. 2022. Rethinking the Music Business: Music Contexts, Rights, Data, and COVID-19, edited by G. Morrow, D. Nordgård, and P. Tschmuck. Springer.

- Moss, L. 2002. “Sheffield’s Cultural Industries Quarter 20 Years on: What Can Be Learned from a Pioneering Example?” International Journal of Cultural Policy 8 (2): 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028663022000009551.

- Nicholson, J. 2013. “Ryman Lofts Hold Grand Opening Celebration”. Music Row. Available online at: https://musicrow.com/2013/04/ryman-lofts-hold-grand-opening-celebration/.

- Pacella, J., S. Luckman, and J O'connor. 2021a. “Keeping Creative: Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Emergency on the Art and Cultural Sector & Responses to it by Governments, Cultural Agencies and the Sector.” Working Paper 1. University of South Australia.

- Pacella, J., S. Luckman, and J. O’Connor. 2021b. “Fire, Pestilence and the Extractive Economy: Cultural Policy After Cultural Policy.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1833308.

- Pratt, A. C. 2020. “COVID – 19 Impacts Cities, Cultures and Societies.” City, Culture and Society 21: 100341–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2020.100341.

- Quader, S. B. 2022. “How the Central Sydney Independent Musicians Use Pre-established ‘Online DIY’ to Sustain Their Networking During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Journal of International Communication 28 (1): 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2021.1989703.

- Rose, T. 2023. “New Protections for Sydney Live Music Venues as NSW Moves to Abolish ‘Nanny State Restrictions”. The Guardian, 19th of October.

- Somekh, B., and C. Lewin. 2005. Research Methods in Social Sciences. Sage Publications.

- Stafford, A. 2014. Pig City. From The Saints to Savage Garden. University of Queensland Press.

- Sutherland, R. 2013. “Why get Involved? Finding Reasons for Municipal Interventions in the Canadian Music Industry.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 19 (3): 366–381.

- Szrafini, P. and Novosel, N. 2021. “Culture as Care: Argentina’s Cultural Policy Response to Covid-19”. Cultural Trends, 30 (1): 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1823821

- Tubadji, A. 2021. “Culture and Mental Health Resilience in Times of COVID-19.” Journal of Population Economics 34: 1219–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00840-7.

- Van der Hoeven, A., and E. Hitters. 2019. “The Social and Cultural Values of Live Music: Sustaining Urban Live Music Ecologies.” Cities 90: 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.02.015.

- Williamson, J., and M. Cloonan. 2007. “Rethinking the Music Industry.” Popular Music 26 (2): 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143007001262.

- Willsteed, J. 2019. “Nazis are no fun. In Bjelke Blues. Stories of Repression and Resistance in Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s Queensland 1968–1987.” (Ed: Edwina Shaw). And Also Books: Qld.

- Wilson, D., and R. Keil. 2008. “The Real Creative Class.” Social & Cultural Geography 9 (8): 841–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802441473.