Abstract

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is a core component of speech pathology practice. However, international literature has highlighted that speech language pathologists (SLPs) may not feel confident or competent in this area. Confidence and competence are critical factors in therapy as they can impact the quality-of-service provision. The purpose of this scoping review was to investigate the confidence/competence of SLPs in AAC. A systematic scoping search was conducted using four databases to identify relevant literature. The first two authors reviewed 30% of abstracts and the remaining 70% were reviewed by the first author. Full-text screening applied the same review approach. Data was then extracted and organized according to the research questions. Thirteen studies were included in the review. All thirteen used self-assessment to measure confidence or competence with one study also using an objective evaluation. Overall, confidence and competence levels varied based on the specific clinical task and etiology of the client in addition to being influenced by prior training, clinician age, workplace and AAC caseload. While current research provides a snapshot of the SLP workforce, it is limited in that the research predominantly uses self-assessment measures, is cross-sectional and is quantitative in nature. Further research into the confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC is required, specifically how confidence and competence can be defined and developed.

In most countries, speech language pathologists (SLPs) have a minimum level of clinical competence or knowledge they must demonstrate prior to entering the workforce and maintain throughout their career (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2020). Superficially, competence is defined as the ability to do something well (Cambridge Dictionary, Citation2023); however when considering speech pathology specifically, competence is an SLP’s ability to use their knowledge, clinical skills and professional values to provide effective, professional and ethical services (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017). Therefore, competence is vital to clinical practice as it not only addresses quality of care for all clients but also ensures client safety.

Competence is difficult to consider in silo as it is underpinned by professional confidence (Holland et al., Citation2012) leading to inconsistent and interchangeable use of these terms. Concept analyses have described this inconsistency and have shown that the term self-efficacy is also used interchangeably with confidence, self-confidence and professional confidence (Holland et al., Citation2012; White, Citation2009). This is not surprising given that confidence is a person’s belief in their own abilities and self-efficacy is a person’s belief of whether they are capable to perform a specific task in relation to the effectiveness of their own behavior (Bandura, Citation1977, Citation1986). Given the lack of consistent definitions and differentiation between these terms, for the purpose of this paper, we have decided to use the term confidence to refer to one’s self-belief in their capabilities. This decision is supported by Doble et al. (Citation2019) who used the terms confidence and self-efficacy interchangeably and applied a confidence scale as a measure of self-efficacy for speech pathology students.

Using the definitions previously noted, competence is an ability that can be assessed externally, while confidence and self-efficacy center on one’s self-belief of their own abilities. Therefore, throughout the literature, SLP confidence has been measured through self-assessment in a variety of areas including written language disorders (Blood et al., Citation2010), dysphagia management (O’Donoghue & Dean-Claytor, Citation2008) and traumatic brain injury (Riedema & Turkstra, Citation2018). On the other hand, the concept of competence can be assessed in two ways, through self-assessment and through objective evaluation (Sears et al., Citation2014). While competence is assessed utilizing both methods throughout most SLP programs at university, it is then generally up to the SLP to ascertain, develop, and maintain their clinical competence post-graduation through self-assessment. As both competence and confidence are used to measure clinician performance and are critical to quality service provision, both concepts have been investigated as part of this scoping review.

All clients deserve high quality of care, but this is particularly important for individuals who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood. Individuals with acquired or developmental disabilities such as autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, aphasia, dysarthria or apraxia often rely on augmentative or alternative communication (AAC) systems (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020; Sutherland et al., Citation2005). AAC refers to systems or strategies used to augment and/or replace verbal speech, including the use of gesture, sign, picture symbols, and speech generating devices (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020).

Despite AAC being listed as an area of clinical competency for SLPs in many countries including Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020; Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists, Citation2021; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017), SLPs are reporting mixed levels of confidence and competence in this area (Sanders et al., Citation2021; Sutherland et al., Citation2005). It has been suggested that a lack of competence in AAC could be due to a lack of training at the university level (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018). This is not surprising as professional confidence and competence are initially fostered through university training which offers a supportive and scaffolded learning environment (Holland et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, training not only increases confidence in a specific task, but also more broadly in a health professional’s role (Jackson et al., Citation2019). Given that professional confidence is often linked to self-perceived success and mastery (Holland et al., Citation2012), the complexity of working with clients who are AAC users may also be a factor. Furthermore, confidence and competence can fluctuate with changes in workplace contexts, policies and legislation, technology, and personal factors (Jackson et al., Citation2019). This is particularly pertinent to AAC since it is a rapidly developing and changing area due to its heavy reliance on the use of technology.

As SLPs are recognized internationally as the profession that supports AAC users through assessment of needs, prescription of AAC systems, provision of intervention, advocacy, and communication partner training (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2012), it is vital to understand not only their level of confidence and competence in working with this population but also what factors will impact these levels.

To investigate these concepts within speech pathology and AAC, a scoping review was performed. The purposes of this review were to

Map the literature pertaining to the confidence and competence of SLPs and SLP students in AAC. Mapping of the literature was intended to answer three research questions:

How is SLP confidence and competence in AAC being investigated?

What are the confidence and competence levels of SLPs in AAC?

What factors (e.g., years of experience, AAC users on caseload, etiology, etc.) impact the confidence or competence of SLPs in AAC?

Identify gaps in the literature pertaining to the confidence and competence of SLPs and SLP students in AAC to inform future research directions.

Method

Research design

Scoping reviews aim to explore the literature around a specific topic with the intent to identify gaps in that literature and inform future research (Sutton et al., Citation2019). While this type of review is still developing in terms of consistent methodology, it is becoming increasingly popular within the literature (Tricco et al., Citation2016). A scoping review was determined as the most appropriate method for this study as it allowed for a broad research question, mapping of existing literature, and identification of gaps, as well as inclusion of research from different methodologies (Peters et al., Citation2021).

This scoping review was conducted as per the five-step framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). In addition, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist was used to ensure accurate and comprehensive reporting of information (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Inclusion criteria

To meet the inclusion criteria, all studies needed to be published in a peer-reviewed journal or accessible dissertation or thesis in English. This decision was made to ensure reliability of study results and is consistent with published scoping reviews (Biggs et al., Citation2019; Dada et al., Citation2021; Hanson et al., Citation2013; Muttiah et al., Citation2022; Schlosser & Koul, Citation2015; Therrien et al., Citation2022). Studies also needed to report on original research, but no parameters were placed on the research method as the purpose of this review was to map all existing literature. Furthermore, studies needed to investigate and report on the confidence or competence of SLPs or SLP students in AAC with any population. As described in the introduction and for the purpose of examining eligibility, competence was defined as the ability to provide adequate services and confidence was defined as the participants’ self-belief that they could provide adequate services; self-efficacy was also included in the search terms. Studies which included other professionals were only included if the data pertaining to confidence and competence of the SLPs or SLP students were reported separately. Studies which used the term confidence, competence, or self-efficacy interchangeably with skills, experience or knowledge were excluded. This criterion was used to ensure that the results represented confidence and competence as defined in the introduction. While it is acknowledged that skills, experience, and knowledge could be related to confidence and competence, they are not interchangeable terms.

AAC is a broad term and therefore the following definition was used for a clear inclusion criterion: any means of communication that is not spoken language use including but not limited to signing, symbol systems, orthographic systems, photo systems, and/or voice-output devices. This definition was developed by the first two authors who are qualified SLPs and hold current registration in Australia. Studies that used signing as a key word approach or aided language approach were included. Studies relating to signing as the language or dialect of the Deaf community (e.g., Auslan) were not included.

Search methods

A search for peer-reviewed journal articles was conducted in August 2022 and 2023 across four databases: PubMed, ERIC via Ebscohost, CINAHL Ultimate and PsycInfo. An additional four databases were searched for dissertations or theses: ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, EBSCO Open Dissertations, British Library Ethos and Theses Canada. As per the PRISMA-ScR, the search strategy used for the CINAHL database has been outlined in . These key terms were entered into each database to identify relevant studies in addition to manual searching and citation chaining.

Table 1. Search terms CINAHL database.

Selection of studies, data extraction, and reliability

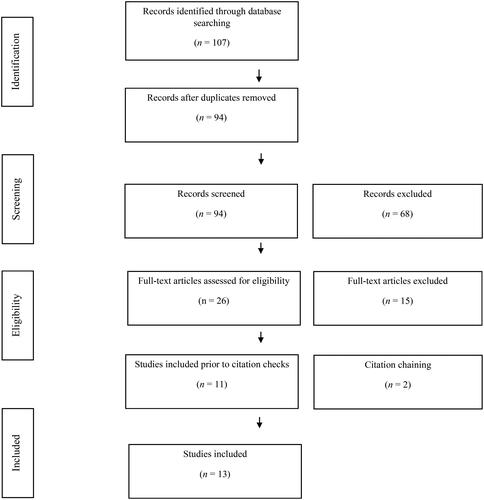

Systematic searches were conducted in August 2022 and again in August 2023. As shown in , these searches identified 107 studies for review. All studies were uploaded to Rayyan (Elmagarmid et al., Citation2016) and 13 duplicates were removed. The same 30% of abstracts were masked for review by the first two authors who are both SLPs (n = 29). Both reviewers then met to ensure the inclusion criteria had been applied consistently. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was met. Following review of the remaining 70% of abstracts by the first author, 26 met the criteria for full text review. The same review process was applied to full text review: author one and author two mask reviewed 30% of full texts (n = 8) with author one reviewing the remaining 70% of studies. After full text review, eleven studies met the criteria for inclusion. Two studies were added based on citation chaining, resulting in thirteen included studies.

Figure 1. Study Selection Flow Chart. Note. has been adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., Citation2021).

The following data were extracted from each article by author one and organized into tables: author, date, country, participant profile, terminology, method, and results. As part of the participant profile, the participant inclusion criteria applied in each study was also recorded to identify differences in the groups of SLPs (e.g., AAC specialists versus SLPs with a generalist caseload). Quality appraisals were not conducted due to the explorative nature of this scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Results

Overall, 26 studies met the criteria for the full text review (see ). Of these studies, 15 were excluded as they did not relate to AAC (n = 1), were not focussed on confidence or competence (n = 10) or SLPs were not the focus (n = 4). After citation chaining, two studies were added. The remaining 13 studies included in this study were published between 1998 and 2023. Most studies (n = 10, 76%) were conducted in the United States, with only one (8%) in New Zealand, one in Malaysia (8%) and one (8%) in the Philippines. All studies included quantitative data pertaining to confidence, competence, or self-efficacy. Of the 13 studies, 11 (84%) used a cross-sectional survey design (Barman et al., Citation2023; Biggs et al., Citation2022, Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Marvin et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023). Only one study (8%) used a survey pre- and post- training (Joginder Singh et al., Citation2022; and one study (8%) used pre- and post-testing of self-reported and clinical supervisor reported competence (Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) (See ).

Table 2. Confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC.

As outlined in , 10 of the 13 studies (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Marvin et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023) investigated the confidence or competence of SLPs and three investigated the confidence or competence of SLP students (Barman et al., Citation2023; Joginder Singh et al., Citation2022; Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018). One study (Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) did not provide participant numbers. The remaining 12 studies included a total of 1688 qualified SLPs (range: 27–283) and 737 students (range: 11–726). Five studies focussed specifically on SLPs who were currently servicing AAC users or clients with complex communication needs (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023). The participant inclusion/exclusion criteria used in each individual study contained in this review have been outlined in .

How is SLP confidence and competence in AAC being investigated?

As outlined in , the majority (n = 7) of studies referred to competence (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Marvin et al., Citation2003; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018; Sutherland et al., Citation2005), followed by confidence (n = 5; Barman et al., Citation2023; Biggs et al., Citation2022; Joginder Singh et al., Citation2022; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2023), and self-efficacy (n = 1; Burke et al., Citation2002). Only six studies (46%) operationally defined confidence, competence, or self-efficacy within the context of their research (see ). Most studies (n = 11) used self-assessment via online quantitative surveys which were cross-sectional to assess confidence, competence, or self-efficacy (Barman et al., Citation2023; Biggs et al., Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Marvin et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023). Only two studies measured the impact of training on confidence/competence using pre- and post- self-reporting (Joginder Singh et al., Citation2022; Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018), with Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) also using an external evaluation completed by a clinical educator.

What are the confidence and competence levels of SLPs in AAC?

As shown in , 10 studies focussed on qualified SLPs (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Marvin et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023) but each used different inclusion criteria which may have impacted results. For example, some studies focussed on SLPs with AAC caseloads only. Other studies focussed on SLPs with general caseloads. These factors may have directly influenced confidence and competence (King, Citation1998; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998). The results that follow were analyzed according to whether the study included SLPs with AAC caseloads only or SLPs with a general caseload. Studies involving SLP students have been reported separately.

Confidence and competence of SLPs with AAC caseloads

In total, five studies (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Burke et al., Citation2002; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Ward et al., Citation2023) surveyed SLPs who worked with AAC users or clients with complex communication needs; however, one study was specific to telehealth (Biggs et al., Citation2022) and another specific to service provision for bilingual clients (Ward et al., Citation2023). These studies have been reported separately. Of the remaining three studies that included only SLPs who worked with AAC users, inclusion criteria ranged from the requirement to be servicing a minimum of only one AAC user (Sanders et al., Citation2021) to a minimum of 20 AAC users (Burke et al., Citation2002); the third study did not specify a required minimum (Sutherland et al., Citation2005). Results showed higher levels of overall self-efficacy (M = 91.4 of 100; SD = 4.92) in the study where participants were required to have more extensive AAC experience (i.e., servicing at least 20 AAC clients; Burke et al., Citation2002) compared to the study where SLPs needed to be servicing a minimum of only one client with complex communication needs (M = 3.35 of 5; SD = 1.17) (Sanders et al., Citation2021). Mixed levels of confidence were reported by SLPs servicing pediatric and/or adult AAC users with only 14% (n = 31) rating themselves as competent in AAC service delivery (Sutherland et al., Citation2005).

Confidence and competence of SLPs with a general caseload

This review identified four studies that included SLPs regardless of whether or not they currently serviced AAC users or people with complex communication needs (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Kovacs, Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998). Of these, two studies conducted in 1998 reported low levels of competency for both SLPs working in healthcare settings (King, Citation1998) and education settings (Simpson et al., Citation1998) with only a small proportion of SLPs rating themselves as “very competent” (King, Citation1998). Comparatively, results from a 2021 study showed higher competency overall (Kovacs, Citation2021). Kovacs (Citation2021) surveyed SLPs in the United States who reported that they felt most competent in the delivery of assessment and intervention services for AAC users in the area of pragmatics and semantics (at least 80%) followed by syntax and morphology (60–73%).

Chua and Gorgon (Citation2018) surveyed SLPs with at least one year of clinical experience. While an overall competency rating was not provided, most SLPs rated their competency as low regardless of client etiology or clinical task (i.e., assessment or intervention).

Confidence and competence of SLPs providing telehealth AAC services

Only one study (Biggs et al., Citation2022) reported specifically on AAC service delivery via telehealth. Biggs et al. (Citation2022) surveyed SLPs about their confidence in providing AAC services via telehealth at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic on a scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident). SLPs reported mixed levels of confidence ranging from M = 2.6 (evaluating progress) to M = 4.0 (confidentiality and ethics).

Confidence and competence of SLP students

Only three studies focussed on SLP students (Barman et al., Citation2023; Joginder Singh et al., Citation2022; Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) however one study focussed specifically on service provision of culturally and linguistically diverse clients (Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) and has been reported separately. Barman et al. (Citation2023) surveyed 726 graduate SLP students and found that only 26% agreed with the statement “I feel confident in my skills to assess and treat AAC clients after graduation”. A significant positive correlation was found between student confidence and feelings of preparedness; both were also found to be significantly correlated with all five types of training experiences (convention/presentation, clinical simulation, AAC vendor, clinical instruction/supervision, and classroom education). Joginder Singh et al. (Citation2022) also identified the positive impact of training for SLP students by measuring changes in self-perceived confidence of 11 final-year SLP students who had completed a 2-week AAC training program for undergraduate SLPs. Following training, SLP students rated their level of confidence as either a seven or eight on a 10-point scale, where 10 equated to a high level of confidence and one equated to a low level of confidence. These post-training confidence ratings showed improvement from pre-training confidence ratings, which ranged from two to four on the same scale.

Confidence and competence supporting culturally and linguistically diverse clients

Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) reported on the competence of SLP students to provide services to culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) AAC clients and Ward et al. (Citation2023) reported on the confidence of SLPs providing services to emergent bilingual AAC users. Similar to Joginder Singh et al. (Citation2022), Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) measured the self-perceived competence of SLP students pre- and post-training; however, this training was specific to service provision of AAC users from CALD backgrounds. Student self-assessment and clinical educator assessment on a 5-point scale indicated improvement from pre- to post-training for all competency areas (language and literacy, programming and intervention, collaboration, literacy development and professional development), with students rating their competence highest for professional development (M = 4.59) and lowest for programming and intervention (M = 4.32).

Ward et al. (Citation2023) surveyed SLPs currently servicing emergent bilingual clients who use AAC. Confidence ratings varied. Overall, SLPs showed agreement for statements of confidence that ranged from 59.3% (device selection) to 68.5% (vocabulary selection). SLPs who reported speaking a language additional to English had significantly higher levels of confidence in assessment, but not in other areas of practice.

What factors impact the confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC?

As outlined in , only six studies tested the relationship between confidence or competence and other variables. Results for each of these variables is outlined below.

Table 3. Factors impacting confidence and competence.

AAC caseload

Out of these six studies, three tested the relationship between AAC caseload and self-perceived confidence/competence (King, Citation1998; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998). All three studies reported SLP confidence or competence in AAC services increased when they had a higher number of AAC users on their caseload.

Training

The influence of training on confidence or competence was only analyzed in three studies; all showed a positive impact (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2023). Although Ward et al. (Citation2023) found no relationship between graduate training and confidence, there was a relationship found between on-the-job training and confidence in assessment as well as continuing education and confidence in assessment and intervention.

Years of experience and clinician age

Only one study investigated the relationship between confidence and years of experience; no relationship was found (Sanders et al., Citation2021). However, Biggs et al. (Citation2022) found a negative relationship between clinician age and confidence in telepractice for AAC users (i.e., younger clinician = lower confidence).

Workplace

Only one study investigated the impact of the workplace on confidence. Biggs et al. (Citation2022) identified that school-based SLPs’ had lower confidence in AAC telepractice compared to SLPs who were not school-based.

Etiology

A total of four studies (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; King, Citation1998; Simpson et al., Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005) specifically asked SLPs about their self-perceived confidence or competence in the delivery of AAC services for clients of different etiologies. In 1998, two studies investigated the competence of SLPs working in healthcare (King, Citation1998) and educational settings (Simpson et al., Citation1998). King (Citation1998) explored this topic within the context of healthcare settings. Using a five-point scale (0 = do not feel competent; 5 = feel very competent), SLPs rated their competency highest for servicing clients with aphasia (M = 3.6) followed by acquired apraxia (M = 3.0). They rated their competency lowest for servicing clients with developmental apraxia (M = 2.3), laryngectomy (M = 2.4), and congenital motor conditions (M = 2.4). Simpson et al. (Citation1998) surveyed SLPs in an educational setting about their self-perceived competence when servicing clients with different types of impairment, across different severities and age groups. Respondents provided a rating between 0 (no competence) and 15 (competence in all aspects of etiology). Data for severity and age group were then collapsed to form an overall competence level for each impairment area where 0% indicated no competence and 100% indicated complete competence. Both SLPs who did provide AAC services and those who did not provide AAC services rated their competence as highest for those clients with cognitive disabilities (AAC services: M = 0.38, SD = 0.29; no AAC services: M = 0.25, SD = 0.27) and lowest for dual sensory disabilities (AAC services: M = 0.16, SD = 0.26; no AAC services: M = 0.6, SD = 0.12) and visual disabilities (AAC services: M = 0.16, SD = 0.26; no AAC services: M = 0.08, SD = 0.17).

In 2005, Sutherland et al. surveyed SLPs about their self-perceived competence for pediatric and adult clients of different etiologies. On a scale of one (competent) to four (poor/inadequate), pediatric SLPs rated their competence highest when servicing clients with developmental delay (M = 1.89) followed by intellectual disability mild/moderate (M = 1.99) and lowest for clients with sensory impairment (i.e., hearing and vision; M = 2.96). SLPs servicing adult clients rated their competence as highest when servicing clients who had experienced cerebrovascular accidents (M = 1.90) and Parkinson’s disease (M = 2.07). Similar to Chua and Gorgon (Citation2018), SLPs rated their competence for servicing clients with Huntington’s disease as lowest (M = 2.58).

In 2018, Chua and Gorgon surveyed SLPs regarding their competence in AAC assessment and intervention for different populations. While autism spectrum disorder received the highest competency ratings overall in comparison to other conditions, only 41% (n = 61) of SLPs reported being competent in AAC assessment and 44% (n = 65) in AAC intervention for this population. In that same study, Huntington’s Disease received the lowest competency ratings (assessment = 2%; intervention = 5%) with low ratings also provided for other degenerative conditions such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (assessment = 11%, intervention = 13%), Multiple Sclerosis (assessment = 11%, intervention = 17%) and Dementia (assessment = 12%, intervention = 13%) (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018).

Discussion

This scoping review identified 13 studies that investigated the confidence or competence of SLPs or SLP students in AAC. All studies identified were quantitative and all but one (Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) used a survey for data collection. In general, SLPs presented with mixed levels of confidence and competence both of which were found to be impacted by workplace setting, clinician age, amount of training (Barman et al., Citation2023; Biggs et al., Citation2022; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2023), the presence/absence of AAC users on caseload (King, Citation1998; Simpson et al., Citation1998), number of AAC users on caseload (Sanders et al., Citation2021) and identifying as an AAC specialist (Sanders et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, confidence and competence were found to vary based on the etiology of the client in both pediatric and adult populations as well as the type of service provided (e.g., assessment or intervention).

How is SLP confidence and competence in AAC being investigated?

As part of this review, measures of confidence, competence and self-efficacy were included and compared as they were all viewed to measure a clinician’s ability to- or self-belief that they could provide adequate services. As shown in , competence was the most frequently studied concept (n = 7) followed by confidence (n = 5) and self-efficacy (n = 1). Out of 13 studies, only six provided a definition or description of the term used (Burke et al., Citation2002; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; Kovacs, Citation2021; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2023). Three studies (Burke et al., Citation2002; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2023) referred to the work of Bandura (Citation1977) linking confidence with self-efficacy and subsequently how well a person can perform a task; Ward et al. (Citation2023) extended this definition to include the self-belief that a person has the skills and training required to do a task. Chua and Gorgon (Citation2018) defined competence as “the ability to adequately provide services” (no source listed); this definition was then referenced by Kovacs (Citation2021). Finally, Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) described their competency assessment as being based on knowledge and skills. The remaining seven studies provided no definition of confidence, competence, or self-efficacy despite treating these entities as variables that can be measured. This begs the question, what is clinical confidence and competence? Furthermore, is confidence interchangeable with both self-efficacy and competence?

Although there seems to be some general consensus that confidence, competence and self-efficacy in speech pathology relates to the belief a task can be done well, the range of definitions used for these terms across different studies within and external to AAC (e.g., Blood et al., Citation2010; Busch & Ma, Citation2023; Loveall et al., Citation2022) suggests that these terms may mean different things to different people. For instance, some studies were excluded from this review as they combined the terms competence, confidence or self-efficacy with terms such as experience (Armstrong et al., Citation2000), knowledge (Armstrong et al., Citation2000) or qualifications (Vento-Wilson, Citation2019). The lack of clearly defined terms raises questions about the credibility of the findings, particularly for studies that rely on self-ratings, because we cannot be sure that the participants are all interpreting the terms the same way, nor can we be sure that they are interpreting them in line with the researchers’ intentions. Synonymous use of these terms confounds results further. One of the studies included in this review highlights this issue. While Ward et al. (Citation2023) reported on confidence (and defined the term in relation to self-efficacy), the term used in the survey was competent (e.g., I feel competent in assessing emergent bilinguals who use AAC) so it is unclear if the participants were rating the researchers’ intended construct. A full discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper, but this scoping review has highlighted the need for greater clarity on the use and interpretation of these terms in future studies.

Issues in terminology and reliable instruments for measurement does not lie with researchers alone. The certifying bodies of SLPs internationally also seem to disagree on the definition of clinical competence and how it can be measured. For example, in the United States, SLPs must meet the requirements of the 2020 Standards and Implementation Procedures for the Certificate of Clinical Competence in Speech-Language Pathology (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020). However, these standards do not define competence. Furthermore, these requirements are met through hours-based practicum, coursework and sitting a final exam suggesting that competence is measured through demonstration of knowledge and skills. Comparatively, Australia (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017) and New Zealand (New Zealand Speech-Language Therapists’ Association, Citation2011) requires students meet the minimum requirements of the Competency-Based Occupational Standards for Speech Pathologists – Entry Level (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017). These requirements define competence as “an individual’s ability to effectively apply all their knowledge, understanding, skills and values within their designated scope of practice” (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2017, p. 3). In addition to university coursework, students are required to meet a minimum level of competence across 13 standards on clinical practicum as evaluated by their clinical educator; suggesting that competence is measured through knowledge in addition to practical performance. These inconsistencies could impact the way SLPs globally view clinical competence including how to develop and maintain clinical competence in complex areas such as AAC.

Although the certifying bodies for SLPs as mentioned previously, tend to rely on some form of practicum-based assessment as a core part of determining competence, self-assessment was used by 92% of the studies in this review (n = 12). Over-representation of self-assessment measures rather than an objective evaluation could be due to a lack of concrete standards in AAC for which SLPs could be compared. Self-assessment via survey also requires less time and resources in comparison to completing an objective evaluation which may make this method a more viable option for researchers. While the use of self-assessment is consistent with measures of SLP confidence in other practice areas (Blood et al., Citation2010; Loveall et al., Citation2022; Muncy et al., Citation2019; Riedema & Turkstra, Citation2018), it is limited in that it only reflects the participant’s views of themselves (Stankov et al., Citation2014) which is not necessarily consistent with objective measures (Sears et al., Citation2014). This was evident in the research by Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) where the mean self-assessment rating of AAC competency by students pre-training (M = 1.86) was much lower than ratings provided by their clinical educators (M = 3.88). This discrepancy highlights that SLPs and SLP students may often underestimate their abilities during self-evaluation. Alternatively, this result may reflect the interconnected nature between confidence and competence whereby SLPs who are not confident may rate their competency as low. Further research using objective measures would create a more complete picture of the confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC.

What are the confidence and competence levels of SLPs in AAC?

While results varied in the reported levels of confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC, levels appear to be increasing over time. In 2003, only 28% of participants in the United States reported good to very good competence in AAC (Marvin et al., Citation2003), however in 2021, 49 to 89% of SLPs rated themselves as competent in assessment and intervention across semantics, pragmatics, phonology, morphology and syntax (Kovacs, Citation2021). This change in competence could be due to the increase in AAC training included in graduate programs in the United States (Johnson & Prebor, Citation2019). The outlier in this finding is feature matching, whereby SLPs continue to rate their competence as low (Sanders et al., Citation2021). Feature matching is the process where the SLP matches AAC options to the needs, capabilities and preferences of the client which requires knowledge of the full range of AAC options (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). Low competence in this area is particularly concerning given that unsuitable device prescription and insufficient device implementation support can lead to AAC abandonment (Johnson et al., Citation2006; Moorcroft et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Low competence could be due to a lack of experience prescribing AAC devices. In a study comparing the assessment practices of general SLPs to AAC specialists, general SLPs followed a two-step linear assessment process whereas AAC specialists completed a holistic assessment including trialing a variety of AAC systems and access methods (Dietz et al., Citation2012). Low competence in feature matching could also be attributed to hands-on training experiences with AAC systems. Only 37% of graduate SLP programs in the United States reported providing 10 hours or more of laboratory time which includes hands-on practice. It is therefore not surprising that qualified SLPs have indicated a strong desire for further training and exposure to AAC options (Balandin & Iacono, Citation1998; Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2008; McCall & Moodie, Citation1998; Sutherland et al., Citation2005; Theodorou & Pampoulou, Citation2022; Tsai, Citation2019). Reduced training and experience may be underlying the tendency for SLPs to base their recommendations on their own knowledge (of systems) and skills, rather than prescribing AAC systems based on client preferences and needs (Theodorou & Pampoulou, Citation2022). A review of AAC training at the university and post-professional level is required to ensure that SLPs take a client-centred approach and feel competent prescribing and implementing a range of AAC systems which constantly change and develop due to technological advances.

What factors impact the confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC?

This scoping review enabled the authors to identify key factors which impact on confidence and competence as well as factors which require further attention. The confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC varied between studies due to factors such as caseload, client etiology, clinical task, years of experience and training. Each of these variables has been discussed below.

Caseload

Three studies found that increased AAC caseloads were associated with higher levels of confidence or competence (King, Citation1998; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998). In other words, SLPs with AAC users on their caseload perceived themselves as more confident or competent. While AAC experience may be positively impacting the confidence or competence of SLPs in this area, it is also possible that SLPs who feel confident or competent in AAC are more likely to seek out servicing this population.

Client etiology

Client etiology was identified as a key variable that impacts the confidence or competence of SLPs working with both pediatric and adult AAC users. This could be due to the varying complexities of different population groups or SLPs’ experience and exposure to each etiology. For example, autism spectrum disorder received higher competency ratings overall in comparison to Huntington’s disease (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; Sutherland et al., Citation2005). This isn’t surprising given that autism spectrum disorder has a much higher prevalence worldwide (100 per 10, 000) (Zeidan et al., Citation2022) than Huntington’s disease (2.71 per 100, 000) (Pringsheim et al., Citation2012) which would impact the amount of experience and therefore confidence and competence an SLP has with each population.

Clinical task

As outlined in , similar to caseload type, confidence, and competence also varied by task (e.g., assessment, intervention, providing professional development, etc.). SLPs were found to rate their self-perceived competence in intervention higher than in assessment (Chua & Gorgon, Citation2018; Kovacs, Citation2021). In comparison to other practice areas such as speech and language which utilize static assessment procedures (such as standardized assessments), AAC assessment is a very complex and dynamic process that is heavily reliant on informal assessment procedures individualized to the client. This means that SLPs need to use a variety of assessment types, methods, and considerations when assessing AAC users (Dietz et al., Citation2012; Lund et al., Citation2017; McKelvey et al., Citation2022; Theodorou & Pampoulou, Citation2022; Watson & Pennington, Citation2015). SLPs also rated their competency highest for tasks such as “protecting confidentiality,” “following the code of ethics” (Biggs et al., Citation2022) and “commitment to professional development” (Solomon-Rice et al., Citation2018) which are skills that can be developed and utilized across any caseload (i.e., not specific to AAC).

Years of experience

Surprisingly, while clinician age was correlated with increased confidence in AAC telepractice (Biggs et al., Citation2022), years of experience were found to have no significant correlation (Sanders et al., Citation2021; Simpson et al., Citation1998). This could be due to the different focus areas for each of these AAC studies which included telepractice (Biggs et al., Citation2022), feature matching (Sanders et al., Citation2021), and general AAC (Simpson et al., Citation1998). Furthermore, while the study by Sanders et al. (Citation2021) required the participant to be servicing at least one client with complex communication needs, neither Sanders et al. (Citation2021) nor Simpson et al. (Citation1998) focused specifically on SLPs with an AAC caseload. Therefore, years of experience may not be directly beneficial if those SLPs were not gaining experience in the area of AAC. Similarly, the lack of a relationship between years of experience and confidence/competence may be due to speech-language pathology being a broad field where clinicians often work in varying sectors with different caseloads (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2022; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2015), in addition to high job turn over (McLaughlin et al., Citation2010). Therefore, years of experience would not necessarily equate to more experience servicing AAC clients.

Training

Solomon-Rice et al. (Citation2018) and Joginder Singh et al. (Citation2022) reported on the impact of AAC training on the competence and confidence of SLP students and showed that training had a positive effect. This is commensurate with studies on qualified SLPs showing that the amount of training positively correlates with increased levels of confidence in AAC (Biggs et al., Citation2022; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2023). Despite this relationship, no literature was identified that directly investigated the impact of AAC training on the confidence or competence of qualified SLPs.

Clinical implications

In the included studies, SLPs reported varying levels of confidence and competence in AAC. SLPs and those employing SLPs should consider the impact of clinician confidence and competence on the delivery of services to individuals who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood and subsequently, ways in which they can improve clinician confidence and competence. This review highlighted that confidence and competence were positively associated with experience in AAC and/or increased AAC caseloads. SLPs who service AAC users or clients who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood for only a small proportion of their caseload should consider alternate ways to gain increased exposure and experience such as mentoring from an AAC specialist or work shadowing. Unsurprisingly, training was also positively associated with confidence and competence which further reinforces the need for SLPs to access continuing professional development across their career. This is particularly pertinent for AAC, as this clinical area is constantly changing due to rapid developments in technology.

Gaps in the literature

One of the purposes of a scoping review is to map existing literature to identify gaps that can be used to inform future research directions (Sutton et al., Citation2019). The confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC is an area of growing interest evidenced by the fact that 62% (n = 8) of included articles were published in the last five years. Despite this increase in research interest, many gaps remain. Three of these gaps are discussed here.

Geographical location

Out of the 13 included studies, 10 studies (76%) were conducted in the United States, one (8%) in New Zealand, one (8%) in Malaysia and one (8%) in the Philippines. This creates a limited international perspective on the confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC given that SLPs support AAC users in many countries, including Australia (Balandin & Iacono, Citation1998; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2012), United Kingdom (McCall & Moodie, Citation1998; Watson & Pennington, Citation2015), Canada (Speech-Language & Audiology Canada, Citation2015), Cyprus (Pampoulou et al., Citation2018), South Africa (Dada et al., Citation2017) and India (Kidwai et al., Citation2022). As the practice, scope, and training of SLPs differ between countries it is assumed that confidence and competence may differ. Unfortunately, this discussion could not be included as part of this review as only four countries are represented in the included studies.

Inter-professional practice

Best practice in AAC assessment and intervention involves practicing within a multi-disciplinary team (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020) however the presence or absence of a team was not explored as a factor impacting the confidence and competence of SLPs within the included studies. This is surprising as the presence of an occupational therapist or physiotherapist is integral for AAC prescription for individuals with physical disabilities and education support cannot be provided without a teacher (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). Given that an effective team can improve client outcomes (Hunt et al., Citation2002), support the operation and maintenance of an AAC system, and improve educational inclusion (Soto et al., Citation2001a, Citation2001b), more research into the impact of a team on confidence and competence is warranted.

Defining and measuring competence and confidence

As discussed previously, there is not a clear and consistent definition of clinical competence or confidence in speech pathology and this review highlighted that this lack of clarity extends to AAC. At this point, there is not a clear descriptor of how a competent AAC speech pathologist practices. Furthermore, definitions of competence and confidence in AAC may differ in ways that reflect contextual factors such as workplace, geographical location and cultural practices. Current studies have used self-assessment measures rather than objective measures. While the use of objective measures would be ideal, they are not commonly used due to issues with rater reliability and the subsequent cost and time associated with this type of research. Establishing a clear and consistent definition of competence in AAC would support the development of behavioral objectives which could then be included as part of self-rating scales. For example, asking participants to self-rate behavioral objectives such as “I trial a range of AAC devices with my clients prior to completing a prescription” instead of vague descriptions of AAC practices (e.g., I am competent in feature matching) could be seen as a more reliable and efficient measurement tool.

Limitations and future directions

While relevant guidelines were followed for conducting a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Tricco et al., Citation2018) studies may have not been identified if they were not indexed in one of the databases used, did not contain the search terms or full text was not available for review. Furthermore, studies needed to be published in English which may have been a contributing factor to only four countries being represented in this review. The inclusion criteria also meant that any studies that combined the results of SLPs with other professionals (such as teachers or occupational therapists) were excluded. The lack of a consistent definition for competence and confidence means that studies could have been missed or excluded due to authors using differing terminology which was not included in the search terms. For example, studies that used terms such as “knowledge” or “skills” interchangeably with “confidence,” “competence” or “self-efficacy” were excluded which limited the number of studies included in this review. Data extraction was completed by the first author only and therefore reliability measures were not completed.

While there are operational terms for competence, confidence, and self-efficacy within the literature, these definitions are not specific to speech pathology practice. Similar to research in occupational therapy (Holland et al., Citation2012), it would be useful for researchers, clinicians, and university staff to have access to a concept analysis of these terms within the clinical field of speech pathology. The use of consistent terminology and measurement tools may lead to increased research translation (Nilsen, Citation2015; Thomas & Bussières, Citation2021). While it is clear that confidence and competence in AAC is a current and persistent issue for SLPs, change in this space requires investment from key stakeholders such as universities and national speech pathology bodies. Exploring the confidence and competence of SLPs across low- and middle-income countries could also be facilitated by investment from key stakeholders.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified 13 studies that reported on the confidence or competence of SLPs in AAC. While self-perceived confidence and competence varied based on AAC caseload, workplace, training, etiology, and task, there was no explorative research investigating why these relationships are occurring. There was a paucity of research that used objective evaluation to measure competence. Despite these gaps, current research shows variable levels of confidence and competence of SLPs in AAC and suggests that experience in AAC and AAC training may benefit the workforce. Further research is required to understand what steps can be taken to ensure speech pathologists feel confident and competent in the provision of AAC services across different populations and age groups.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2020). 2020 standards and implementation procedures for the certificate of clinical competence in speech-language pathology. 3rd of November, 2022. https://www.asha.org/certification/2020-slp-certification-standards/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2022). Supply and demand resources list for speech-language pathologists. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/supply-demand-slp.pdf Retrieved on 31st March, 2023.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Armstrong, L., Jans, D., & MacDonald, A. (2000). Parkinson’s disease and aided AAC: Some evidence from practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 35(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/136828200410636

- Balandin, S., & Iacono, T. (1998). AAC and Australian speech pathologists: Report on a national survey. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 14(4), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619812331278416

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

- *Barman, B. E., Dubasik, V. L., Brackenbury, T., & Colcord, D. J. (2023). Graduate students’ perceived preparedness and confidence to work with individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 32(3), 1165–1181. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_AJSLP-22-00282

- Beukelman, D., & Light, J. (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (5th ed.). Brookes Publishing Company.

- Biggs, E., Carter, E., & Gilson, C. (2019). A scoping review of the involvement of children’s communication partners in aided augmentative and alternative communication modeling interventions. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(2), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_ajslp-18-0024

- *Biggs, E., Rossi, E. B., Douglas, S. N., Therrien, M. C. S., & Snodgrass, M. R. (2022). Preparedness, training, and support for augmentative and alternative communication telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(2), 335–359. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00159

- Blood, G. W., Mamett, C., Gordon, R., & Blood, I. M. (2010). Written language disorders: Speech-language pathologists’ training, knowledge, and confidence. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(4), 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/09-0032)

- *Burke, R., Beukelman, D., Ball, L., & Horn, C. (2002). Augmentative and alternative communication technology learning part 1: Augmentative and alternative communication intervention specialists. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610212331281321

- Busch, C. M., & Ma, T. (2023). Speech-language pathology graduate students’ perception of satisfaction, confidence, and interpersonal skill development during simulated experiences amid COVID-19. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 8(1), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00073

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2023). Competence. Cambridge University Press.

- *Chua, E., & Gorgon, E. (2018). Augmentative and alternative communication in the Philippines: A survey of speech-language pathologist competence, training and practice. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 35(2), 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2019.1576223

- Dada, S., Flores, C., Bastable, K., & Schlosser, R. W. (2021). The effects of augmentative and alternative communication interventions on the receptive language skills of children with developmental disabilities: A scoping review. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1797165

- Dada, S., Murphy, Y., & Tönsing, K. (2017). Augmentative and alternative communication practices: A descriptive study of the perceptions of South African speech-language therapists. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 33(4), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2017.1375979

- Dietz, A., Quach, W., Lund, S., & McKelvey, M. (2012). AAC assessment and clinical-decision making: The impact of experience. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 28(3), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2012.704521

- Doble, M., Short, K., Murray, E., Bogaardt, H., & McCabe, P. (2019). Evidence-based practice self-efficacy of undergraduate speech pathology students following training. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(12), 1484–1490. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1430174

- Elmagarmid, A., Fedorowicz, Z., Hammady, H., Ilyas, I., Khabsa, M., & Ouzzani, M. (2016). Rayyan: A systematic reviews web app for exploring and filtering searches for eligible studies for. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Hanson, E., Beukelman, D., & Yorkston, K. (2013). Communication support through multimodal supplementation: A scoping review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 29(4), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2013.848934

- Holland, K., Middleton, L., & Uys, L. (2012). Professional confidence: A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(2), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.583939

- Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Müller, E., & Goetz, L. (2002). Collaborative teaming to support students with augmentative and alternative communication needs in general education classrooms. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/714868359

- Jackson, B., Purdy, S., & Cooper-Thomas, H. (2019). Role of professional confidence in the development of expert allied health professionals: A narrative review. Journal of Allied Health, 48(3), 226–232.

- *Joginder Singh, S., Suhumaran, L. V., Skulski, K., & Ahmad Rusli, Y. (2022). Malaysian speech-language pathology students’ reflections about their participation in an AAC training program. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 38(4), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2022.2141135

- Johnson, J., Inglebret, E., Jones, C., & Ray, J. (2006). Perspectives of speech language pathologists regarding success versus abandonement of AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 22(2), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610500483588

- Johnson, R., & Prebor, J. (2019). Update on preservice training in augmentative and alternative communication for speech-language pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(2), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0004

- Kent-Walsh, J., Stark, C., & Binger, C. (2008). Tales from the school trenches: AAC service delivery and clinical expertise. Seminars in Speech and Language, 29(2), 146–154. ISSN 0734-0478 https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1079128

- Kidwai, J., Brumberg, J., & Gatts, J. (2022). Aphasia and high-tech communication support: A survey of SLPs in USA and India. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2022.2109072

- *King, J. (1998). Preliminary survey of speech-language pathologists providing AAC services in health care settings Nebraska. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 14(4), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619812331278396

- *Kovacs, T. (2021). A survey of American speech-language pathologists’ perspectives on augmentative and alternative communication assessment and intervention across language domains. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(3), 1038–1048. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00224

- Loveall, S. J., Pitt, A. R., Rolfe, K. G., & Mann, J. (2022). Speech-language pathologist reading survey: Scope of practice, training, caseloads, and confidence. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(3), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_LSHSS-21-00135

- Lund, S., Quach, W., Weissling, K., McKelvey, M., & Dietz, A. (2017). Assessment with children who need augmentative and alternative communication (AAC): Clinical decisions of AAC specialists. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0086

- *Marvin, L., Montano, J., Fusco, L., & Gould, E. (2003). Speech-language pathologists’ perceptions of their training and experience in using alternative and augmentative communication. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 30(Spring), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_30_S_76

- McCall, F., & Moodie, E. (1998). Training staff to support AAC users in Scotland: Current status and needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 14(4), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619812331278406

- McKelvey, M., Weissling, K. S. E., Lund, S. K., Quach, W., & Dietz, A. (2022). Augmentative and alternative communication assessment in adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Results of semi-structured interviews. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 43(3), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/15257401211017143

- McLaughlin, E., Adamson, B., Lincoln, M., Pallant, J., & Cooper, C. (2010). Turnover and intent to leave among speech pathologists. Australian Health Review: A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association, 34(2), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH08659

- Moorcroft, A., Scarinci, N., & Meyer, C. (2019). Speech pathologist perspectives on the acceptance versus rejection or abandonment of AAC systems for children with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 35(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2019.1609577

- Moorcroft, A., Scarinci, N., & Meyer, C. (2020). We were just of kind of handed it and then it was smoke bombed by everyone”: How do external stakeholders contribute to parent rejection and the abandonment of AAC systems? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12502

- Muncy, M. P., Yoho, S. E., & McClain, M. B. (2019). Confidence of school-based speech-language pathologists and school psychologists in assessing students with hearing loss and other co-occurring disabilities. Language, Speech & Hearing. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 50(2), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_LSHSS-18-0091

- Muttiah, N., Gormley, J., & Drager, K. D. R. (2022). A scoping review of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) interventions in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 38(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2022.2046854

- New Zealand Speech-Language Therapists’ Association. (2011). NZSTA programme accreditation framework 2011 (Amended 2020/21). 3rd of November, 2022. https://speechtherapy.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/NZSTA-Programme-Accreditation-Framework-2011_amendedDec2020.pdf

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

- O’Donoghue, C. R., & Dean-Claytor, A. (2008). Training and self-reported confidence for dysphagia management among speech-language pathologists in the schools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39(2), 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2008/019)

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Pampoulou, E., Theodorou, E., & Petinou, K. (2018). The use of augmentative and alternative communication in Cyprus: Findings from a preliminary survey. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 34(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659018755523

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garritty, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O'Brien, K. K., Tunçalp, Ö., Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. (2021). Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 263–263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

- Pringsheim, T., Wiltshire, K., Day, L., Dykeman, J., Steeves, T., & Jette, N. (2012). The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 27(9), 1083–1091. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25075

- Riedema, S., & Turkstra, L. (2018). Knowledge, confidence, and practice patterns of speech-language pathologists working with adults with traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(1), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-17-0011

- Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. (2021). Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) overview. 8th of February, 2021. https://www.rcslt.org/speech-and-language-therapy/clinical-information/augmentative-and-alternative-communication/#section-2

- *Sanders, E. J., Page, T. A., & Lesher, D. (2021). School-based speech-language pathologists: Confidence in augmentative and alternative communication assessment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(2), 512–528. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_LSHSS-20-00067

- Schlosser, R., & Koul, R. (2015). Speech output technologies in interventions for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A scoping review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 31(4), 285–309. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2015.1063689

- Sears, K., Godfrey, C. M., Luctkar-Flude, M., Ginsburg, L., Tregunno, D., & Ross-White, A. (2014). Measuring competence in healthcare learners and healthcare professionals by comparing self-assessment with objective structured clinical examinations: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 12(11), 221–272. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2014-1605

- *Simpson, K., Beukelman, D., & Bird, A. (1998). Survey of school speech and language service provision to students with severe communication impairments in Nebraska. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 14(4), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619812331278386

- *Solomon-Rice, P., Soto, G., & Robinson, N. (2018). Project building bridges: Training speech-language pathologists to provide culturally and linguistically responsive augmentative and alternative communication services to school-age children with diverse backgrounds. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(12), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG12.186

- Soto, G., Mu Ller, E., Hunt, P., & Goetz, L. (2001a). Clinical exchange. Professional skills for serving students who use AAC in general education classrooms: A team perspective. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2001/005)

- Soto, G., Müller, E., Hunt, P., & Goetz, L. (2001b). Critical issues in the inclusion of students who use augmentative and alternative communication: An educational team perspective. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 17(2), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/714043369

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2012). Clinical guideline: Augmentative and alternative communication. 3rd of February, 2021 https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/spaweb/Members/Clinical_Guidelines/Clinical_Guidelines.aspx?hkey=f66634e4-825a-4f1a-910d-644553f59140

- Speech Pathology Autralia. (2015). A snapshot of Australia’s speechies. javascript://[Uploaded files/Resources for the public/What is a Speech Pathologist/Asnapshot_Australias_speechies_2015.pdf] Retrieved on the 30th of August, 2021.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2017). Competency-based occupational standards for speech pathologists. The Speech Pathology Association of Australia Limited. 24th April, 2021. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Resources_For_Speech_Pathologists/CBOS/SPAweb/Resources_for_Speech_Pathologists/CBOS/CBOS.aspx?hkey=c1509605-c754-4aa8-bc10-b099c1211d4d

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020). Professional standards for speech pathologists in Australia. The Speech Pathology Association of Australia Limited. 24th April, 2021. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Resources_for_Speech_Pathologists/CBOS/Professional_Standards.aspx

- Speech-Language & Audiology Canada. (2015). SAC position paper on the role of speech-language pathologists with respect to augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). 17th March, 2022. https://sac-oac.ca/sites/default/files/resources/aac_position-paper_en.pdf

- Stankov, L., Kleitman, S., & Jackson, S. (2014). Measures of the trait of confidence. In: G.J. Boyle, D.H. Saklofske and G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological constructs (pp. 158–189). Academic Press.

- *Sutherland, D., Gillon, G., & Yoder, D. (2005). AAC use and service provision: A survey of New Zealand speech-language therapists. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21(4), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610500103483

- Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36(3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

- Theodorou, E., & Pampoulou, E. (2022). Investigating the assessment procedures for children with complex communication needs. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 43(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740120960643

- Therrien, M. C. S., Barton-Hulsey, A., & Wong, S. (2022). A scoping review of the playground experiences of children with AAC needs*. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985)), 38(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2022.2155874

- Thomas, A., & Bussières, A. (2021). Leveraging knowledge translation and implementation science in the pursuit of evidence informed health professions education. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 26(3), 1157–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10021-y

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., Wilson, K., Kenny, M., Warren, R., Wilson, C., Stelfox, H. T., & Straus, S. E. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 15–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

- Tsai, M.-J. (2019). Augmentative and alternative communication service by speech-language pathologists in Taiwan. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 40(3), 176–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740118759912

- Vento-Wilson, M. (2019). The intersection of speech-language pathologists’ beliefs, perceptions, and practices and the language acquisition and development of emerging aided communicators [Ph.D., Chapman University]. In ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (2218461774). ProQuest One Academic. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/intersection-speech-language-pathologists-beliefs/docview/2218461774/se-2?accountid=10016

- *Ward, H., King, M., & Soto, G. (2023). Augmentative and alternative communication services for emergent bilinguals: Perspectives, practices, and confidence of speech-language pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 32(3), 1212–1235. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_AJSLP-22-00295

- Watson, R., & Pennington, L. (2015). Assessment and management of the communication difficulties of children with cerebral palsy: A UK survey of SLT practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12138

- White, K. A. (2009). Self-confidence: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 44(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00133.x

- Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696