ABSTRACT

Sustainability is about carrying life on. If it is to mean anything, it must be for everyone and everything, and not for some to the exclusion of others. What kind of world, then, has a place for everyone and everything, both now and into the future? What does it mean for such a world to carry on? And how can we make it happen? To answer these questions, I take a closer look at what we mean by ‘everything’. I argue that it is not the sum of minimally existing entities, joined into ever larger and more complex structures, but a a fluid and heterogeneous plenum from within which things emerge as folds. How, then, does such an understanding of everything affect our concept of sustainability? It can no longer be understood in terms of the numerical balance of recruitment and loss. It is rather about lifecycles, about things’ lasting. In the sustainability of everything there is no opposition between stability and change. The more that global science has committed itself to a numerical calculus of sustainability, the more it has fallen to art to present the alternative. This has crucial implications for the ways we think about democratic citizenship.

Beginning with the conversation

This essay both begins and ends with a conversation. I begin with a conversation with the director of an arts organization in the northeast of Scotland.Footnote1 She was planning an event to celebrate the planting of a new woodland in the area and wanted me to contribute to the event with a talk. I asked her what topics she had in mind. Her answer was that I should address the theme of sustainability, and its bearing on art, science and ecology, and citizenship and democracy. “You mean, you want me to talk about the sustainability of everything?”, I replied incredulously. It seemed at the time like an impossible thing to do. Yet the more I thought about it, the more it seemed to me that sustainability is either everything or it is nothing. It cannot be of some things and not others; it can countenance no boundaries of inclusion and exclusion. What kind of everything, then, can always surpass itself, always have room for more, without at any moment appearing partial or incomplete? The answer to which I eventually gravitated, and which I shall elaborate in what follows, is that everything is indeed a conversation. This conversation, with which I will eventually end this essay, is no more, and no less, than the world we inhabit.

To reach this conclusion, and to fulfil the brief that was originally presented to me, I had to pose three subsidiary questions. First, how can we imagine a world that has room for ourselves and for everyone and everything else, both now and for generations to come? Second, what does it mean for such a world to carry on, to keep on going, to be sustained? And third, what can we do to make this happen? To answer these questions, we need to take a closer look at our two keywords, “sustainability” and “everything”. I admit that for many readers, the notion of sustainability may seem to have outlived its worth, to have been devalued by overuse, and compromised through its co-option by powerful interests whose overriding concern has been for their survival in a world of ever more intense competition for dwindling planetary resources. Yet I believe it is a notion we cannot do without, and that to give up on it would be tantamount to the abandonment of our responsibility towards coming generations. The challenge, then, is to give meaning to a term that paradoxically combines the idea of an absolute limit with the limitlessness of carrying on forever. Real sustainability, I shall argue, begins at the moment when the doors of perception swing open, when objectivity gives way to the search for truth, or finality to renewal, whereupon what appears from the outside as a limit opens up from within into a space of growth, movement and transformation, to limitless possibility, or in a word, to everything. And it is with everything that I begin.

The plenum

For those of us educated in the ways of modern science, we are inclined to conclude with everything rather than to begin from it. And we can conclude, we think, only by summing things up. That is, we perform an addition. We add and we add: numbers of people, numbers of species, numbers of objects of this or that kind, numbers of characters on the page, numbers of stars in the sky, numbers of cells in the body, numbers of atoms in a pinhead. We are bamboozled by numbers, many of a magnitude that defy comprehension. But to add things up, they have first to be broken off from the processes that gave rise to them, from the ebbs and flows of life. You must be able to tell where one thing ends, and another begins. The world must be rendered discontinuous. We soon discover, however, that some things are difficult if not impossible to render thus, as discrete, enumerable quanta. Try adding up clouds in the sky, waves in the ocean, trees in the woods, and fungi. The difficulty is that these things are always forming and dissolving, growing and decomposing, appearing sometimes to merge, and at other times to break up.

Take clouds, for example. Clouds are not discrete objects, suspended in the sky. They are rather folds of the sky itself – moisture-laden formations of the turbulent and crumpled mass of atmospheric air (Ingold Citation2015, 90). Waves, too, are folds, ever forming at the surface where the ocean, in its intercourse with the sky, is whipped up by the wind. You could perhaps count waves as they wash up upon the shore, much as you could count footsteps, breaths or heartbeats. But what would they amount to? A life, perhaps, with breaths, steps and heartbeats; all eternity with the waves. Counting would not be adding up a world but the rhythm of time passing. With trees and fungi, addition is just as impracticable. Who can say how many trees there are in a wood? True, you could measure up, as foresters do, estimating the number and volume of trunks in the stack when a plot is felled. But in so doing you have already, in your mind’s eye, cut each and every tree from all that nourishes it and gives it life: the soil, the fungi that wrap around its roots, the air and sunlight that fuel its growth. And to count fungi is merely to enumerate the fruiting bodies, ignoring the underground mesh of the mycelium from which they spring.

But is it really any different with people? Are they any easier to add up than clouds, waves, trees and fungi? Can you arrive at everybody by counting heads? In a crude sense, of course, you can, as in the taking of a census or a vote, but only by abstracting every head from the living, breathing body of which it is intrinsically a part. Topologically, the body is not a closed container but an open vessel, its surfaces so intricately infolded that it is practically impossible to distinguish its interior and exterior regions. Normally, we see only one part of every person – namely, the fleshy part. The part we don’t see is the breath, the air we inhale and exhale, and without which we could not live. Like trees in the wood, people intermingle with one another – they “go in and out of each other’s bodies”, in the beguiling phrase of anthropologist Maurice Bloch (Citation2012, 120) – even as they breathe the air. And their voices, carried on the breath and permeating the atmosphere, mingle also, sometimes joining, as in the unison of song, sometimes splitting apart as they “lift-up-over” one another without ever separating into discrete sounds (Feld Citation1996, 100). You may, through an act of differential attention, be able to tell one voice from another, to split them along the grain of their becoming. But you cannot count them up.

In the polyphony of voices – in the conversation – the collective everyone, like everything, is an intermingling: not a totality, arrived at by the addition of its individual elements, but what I call a plenum. By this, I do not mean a space filled up to capacity with things. The plenum is rather fullness itself. The things we find there – including clouds, waves, trees, and people – emerge as folds, ever-forming by way of the turbulence of lively materials. With the plenum, we do not end with everything nor, strictly speaking, do we begin with it. We find ourselves, instead, wrapped in its midst.

Folding, cutting, splitting

We have many words to describe the plenum: world, cosmos, nature, earth. But does the world contain holes that remain to be filled? Are there gaps in the cosmos, voids in nature, empty spaces in the earth? We might regard a patch of ground as a site on which to build. It must first be cleared of obstructions like trees and boulders, foundations must be dug, and materials gathered and assembled. To clear the ground, however, is not to leave a void but to smooth it out, as when you remove a crease from a fabric. And to build is not to refill the space but once again to crease the ground, pressing it into the rising forms of walls and the vault of the roof. Thus, every infill is, in reality, a reworking, a doubling up that introduces a kink, twist or knot into the very fabric of the earth. Things that to our senses might appear solid, tangible and visibly stable – a building here, a tree or a boulder there, even a human being or an animal, each occupying its particular region of space or moment in time – are truly but the provisional forms or envelopes of incessant movement.

In the plenum, material folds on itself as it goes along. As it does so it endlessly overflows any formal envelopes within which it may appear temporarily to have been pulled aside or detained. The plenum, then, is limitless, not because its capacity can always be increased, but because it forever carries on. We do not ask the ocean whether it has room to accommodate a few more waves; nor does the ocean respond like an overbooked hotelier: “Unfortunately we are full up.”Footnote2 For the waves are ever forming, even as they break upon the shore. Thus everything, in the sense of the plenum, is not an ultimate conclusion, not the sum total when all is added up, but pure becoming. Things, in their becoming, continually differentiate themselves from within the plenum – as do clouds in the sky, or waves in the ocean, or indeed voices in the conversation – without ever parting company with it. You don’t tell things apart by superimposing a conceptual grid on the data of experience. You do it by entering into the processes of their formation and by separating them from the inside, along the grain. It is a matter of splitting, not cutting.

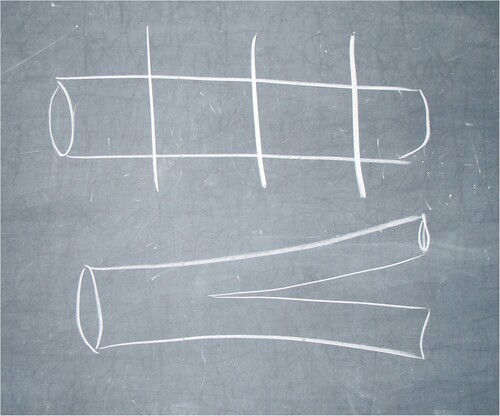

To get at the difference, compare cutting a log with a saw and splitting it with an axe (). In the first case, you impose a system of fixed intervals upon the raw material of timber. Having cut the log into lengths, you can count them up. But in the second case, with the axe, you enter into the grain and follow a line of growth – a line incorporated into the timber when it was a living tree, growing in the ground. With cutting, you divide from the outside; with splitting you differentiate from the inside. Splitting, in short, is a process of what I call “interstitial differentiation” (Ingold Citation2015, 23; Citation2022, 55).

Figure 1. Cutting and splitting. Above, a log sawn against the grain into sections; below, the same log split along the grain with an axe. Blackboard sketch from a lecture. Photo by the author.

For another example of the same distinction, compare walking with surveying. In Ancient Egypt, the job of the surveyor – known as a “rope-stretcher” – was to measure up and divide the land into plots following every annual flood of the Nile. He would drive stakes into the ground at fixed points and stretch the rope from one to the other in order to determine field boundaries. Every stake is a stoppage – the equivalent of what we would now call a data point – and the line of rope connecting them divides the ground. The walker, however, does not join points but passes between them. His feet both follow the trail and, in their impression, reinscribe it. Thus the trail, or the path, is not laid out over the ground but formed from within it. You might be able to tell the path from the ground, but there is no telling the ground from the path. Moreover, turning from walking to writing, we find the same contrast. The handwritten trace emerges from within the texture of the page, where pen meets parchment or paper along a line of movement. But printed words and letters are deposited from above. You can count the number of characters on a printed page; and on screen, your laptop can do it automatically, at the touch of a button. But there is no way of counting the number of lines on a page of handwriting.

Progressive development and the continuity of life

How, then, can we comprehend everything? Do we collect all the data, count up all the people, survey all the land and add up all the words? Is it a matter of assembling wholes from parts, in a nested series of levels in which wholes at one level become parts of wholes at the next level up? Is everything, in this sense, a vertically integrated totality? Or do we find everything by going along, following every root, runner, trail and trace? The latter implies an entirely different view of part-whole relations, harmonic rather than totalizing, in which coherence arises from the tension of contrary forces and inclinations. The rope, for example, maintains its torsion and does not unwind because the twist of its constituent strands is contrary to the twist of its strands with one another. In polyphonic music, melodic lines likewise answer to each other in counterpoint. Yet the rope keeps on winding, the music keeps sounding, and the waves keep breaking on the shore. The plenum, in short, belongs to time; perhaps, indeed, it is time. Everything, in the sense of the plenum, is not an ultimate conclusion, not the sum total when all is added up, but pure concrescence. For in a concrescent world, as philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (Citation1929, 410) taught, everything is perpetually undergoing creation together: trees growing together in the wood, people living together in society, their voices carrying on together in conversation. This does not mean, of course, that the plenary world is only half-formed, or incomplete. For incompletion can only be judged in relation to a state of finality. In the plenum, by contrast, nothing is final, and every ending is an unfinished that opens up to a fresh beginning.

With this, we return to the question from which I began: how can we imagine a world that is sustainable for everyone and everything, both now and forever? In the plenum, as we have found, everything is sustainable because it tends to no limit but rather opens to a perpetual process of world renewal. Indeed, in redefining everything as a plenum, we have also come close to achieving a workable definition of sustainability. It is a definition, however, that stands in stark contrast to that of mainstream sustainability science. In the currently dominant discourses of science, technology and commerce, the aim of sustainability is not to open up to the power of world renewal but to harness or capture this power and put it to use in the production of so-called renewables. This is to turn beginnings into endings, the transformative power of a living earth into goods and services for present and future human consumption. In the rationale of sustainable development, the world is understood not as a plenum to be inhabited but as a totality to be managed, much as a company manages its assets, by balancing the books, living off interest without eating into capital reserves.Footnote3 Sustainability is thus defined in terms of goals or targets to be achieved, along an axis of progressive development. The sustainability of everything, however, runs counter to this axis. Its commitment is not to progress so much as to the continuity of life.Footnote4

In a study of upland forestry in Japan, anthropologist John Knight (Citation1998) offers a cautionary tale of what can go wrong if the axis of development takes precedence over the axis of continuity. Traditionally, Japanese foresters would look after trees for a generation, and then cut them for use as house timbers. In the house, the timbers enjoy what the foresters call a second life. In this phase, the direction of care is reversed. For where foresters had nurtured trees in their first life, it is now the trees that nurture the foresters and their families in the second, by furnishing the warmth, shelter, and comfort of the dwelling. During this time, the foresters are looking after a new generation of growing trees, which will eventually, in their turn, become replacement house timbers. And so it would continue, generation after generation. Here, the lives of foresters and their trees go along together, responding to one another in a cycle of mutual care that, in principle, can continue indefinitely. But today, as Knight shows, the cycle has been broken. Conservationists demand that old trees be preserved and not cut. These arboreal veterans are hence denied their second life. And the people, left without timbers to replace old ones as they rot, have taken to building their houses out of concrete instead. Development, here, has trumped continuity.

This example reveals a deeply entrenched fault line in ways of thinking about the future. Should it be projected as a steady state, or anticipated as an ongoing concrescence? Even if it were possible, in theory, to balance the ship of the world on its keel, the balance could only be sustained by calming the ocean, putting life and history permanently on hold. The future, then, could be no more than a protraction of the present. Far from ensuring the continuation of everything, sustainability would shut it down. My argument, to the contrary, is that to bring sustainability and everything back into line, we need fundamentally to rethink our relation to the world, the future, time and memory. And with this, we come to the third of the questions with which I began. To recapitulate: in response to the first question, I have shown how a world that has room for everyone and everything, for all time, must be imagined as a plenum. In response to the second, I have shown that for such a world to carry on, we need to understand sustainability as concrescence – as a process in which persons and things, as they wind along together, bring each other into being in a renewal that knows no end. The third question, however, asks what we can do now, in our present times, to bring about a world fit for coming generations to inhabit. Is it possible, even in principle let alone in practice, to fashion sustainability by design?

Carrying on

On the face of it, this seems a fruitless endeavour. For if, say, our predecessors had succeeded in designing the future we now inhabit, what would be left for us? We would have nothing to do save to fall in line with their already imposed imperatives. Alternatively, were it to fall to us to shape a future for our successors, then they in turn would become mere users, or consumers, tied to the implementation of a design already made for them. Design, it seems, must fail if every generation is to look forward to a future that it can call its own: that is, for every generation to begin afresh, to be a new generation. Perhaps the very history of design could be understood as the cumulative record of concerted human efforts to put an end to it: an interminable series of final answers, none of which, in retrospect, turns out to be final after all.Footnote5 Or to adapt a maxim from the environmental pundit Stewart Brand (Citation1994, 75): all designs are predictions; all predictions are wrong.

This hardly sounds like a formula for sustainable living. The sustainability of everything, I have argued, is not about meeting targets. It is about keeping life going. Yet design based on the science of sustainability seems intent on bringing life to a stop, by specifying moments of completion when things fall into line with prior projections. “Form is the end, death”, insisted the artist Paul Klee (Citation1973, 269) in his notebooks; “Form-giving is movement, action. Form-giving is life.” By setting ends to things do we not, as Klee intimated, kill them off? If design brings predictability and foreclosure to a life process that is inherently open-ended and concrescent, then is it not the very antithesis of life? How, following Klee’s example, might we shift the emphasis in design from form to form-giving? How, in other words, can we think of design as part of a process of life whose outstanding characteristic is not that it tends to a limit but that it carries on?

Design for the plenum – for the sustainability of everything – if it is to meet this requirement, must be driven not by plans and predictions but by hope. With plans and predictions, we can be optimistic that their realization is just around the corner. There is light at the end of the tunnel. But hope and optimism are not the same. The difference is that optimism anticipates final outcomes; hope does not. The verb “to hope” is not transitive – like “to make” or “to build” – but intransitive, like “to grow” and indeed “to live” (Ingold Citation2011, 6). It denotes a process that does not begin here and end there but carries on through. I suggest that in designing for sustainability, in making it happen, we should treat “design” too, as an intransitive verb, as a way of carrying on that is intrinsically open-ended. Ask not, then, what you are designing, but how. Let me return to Klee, this time to his celebrated Creative Credo of 1920: “Art does not reproduce the visible but makes visible”.Footnote6 It is not for art, Klee contended, to hold a mirror to reality. It is rather to enter into the relations and processes that give rise to things so as to bring them into the field of our awareness. And only so long as these relations and processes carry on can the world offer a sustainable abode for its inhabitants.

I believe we can understand design for sustainability as an art in Klee’s sense. Far from setting out to transform the world, or to bring it into line with a preconceived plan, it is to enter imaginatively into the process of the world’s transforming itself, of its autopoiesis (McLean Citation2009, 231). This process, however, unfolds along not one but multiple paths. It is, in essence, a conversation. Like life, conversations carry on; they have no particular beginning point or end point; no one knows in advance what will come out of them, nor can their conduct be dictated by any one partner. They are truly collective achievements. Let us, then, think of designing for sustainability as a conversation, embracing not only human beings but all the other constituents of the lifeworld, from nonhuman animals of all sorts to things like trees, rivers, mountains, and the earth. All who join the conversation are contributing, each in their own way, to design for a sustainable world.Footnote7

Art and science

Let me now return to the challenges put to me, in the conversation that originally prompted this essay. In the sustainability of everything, what is there for art to do, what is the relation between art, science and ecology, and what does our rethinking of sustainability mean for citizenship and democracy? I have argued that sustainability can only be reconciled with everything if we redefine our relation to the world and our place in it. To do so means acknowledging, with physicist and feminist theorist Karen Barad (Citation2007, 185), that far from standing outside the world, and imposing our designs upon it, we are ourselves “part of the world in its differential becoming”. For science, this is a hard pill to swallow – increasingly hard, as science has sought to immunize itself, through the perfection of its instruments and the elaboration of its methodology, from what is perceived as distortions arising from any affective involvement of practitioners with the objects of their study. This immunity, however, has also hardened scientists’ resistance to the kind of ecological sensibility that would ground their ways of knowing in the habitation of a lifeworld. The goals of today’s science, more than ever before, are of modelling, prediction and control. It has consequently fallen largely to art to take on the mantle of radical ecological awareness that science has cast aside.Footnote8

Many contemporary environmental artists, along with their colleagues in architecture and design, are leading the way in breaking down the barriers between humanity and nature, foregrounding lived experience, and highlighting the richness and complexity, as well as the mystery and strangeness, of a world which human beings have irrevocably altered through their activities yet in which they remain puny by comparison to the forces they have unleashed. This is not to say that art, in its way of working, is necessarily opposed to science. It is rather to plead for a different way of doing science – different, at least, from its more arrogant and hubristic versions, by which I mean the kind of “big science” that, in this epoch of the Anthropocene, pretends to have the power to fix the planet once and for all. A true science of sustainability, rather than claiming exclusive powers both to explicate the world and to bring it under control, should be more modest, deferential and – above all – attentive in its ambitions, and should be prepared to admit the things it studies into the field of its own deliberations. In short, for it to join the conversation, science must shed its totalitarian impulses and recognize that its peculiar way of knowing is neither sovereign nor absolute but one of many.

After all, how can we possibly know everything? If the plenum is not closed in but open to infinite differentiation, then the same must be true of our ways of knowing it. They, too, must go along together, and differentiate themselves from one another, in the ever-continuing conversations of life. It is usual for scientists to call their ways of knowing “research”, and in the science of sustainability, as we have seen, research is closely tied to the calculus of renewables. The claim of scientific research, that it aims to fill gaps in understanding, rests on a logic of addition, on the idea that our knowledge of the world, though currently incomplete, will ultimately add up to a totality. However, for an itinerant practice of research that follows the ways of the world from within, there are no gaps to fill. Indeed, my earlier observation that in the plenum every apparent infill is really a reworking applies with equal force to research. What is research, after all, if not a way of searching again, a second search, which at once doubles up on what went before and is an original intervention in its turn? That’s what research literally means, a reworking, in which we differentiate emergent phenomena even as we join with them. Experienced thus, as a way of knowing, research continually surpasses itself. It is not an addition but a concrescence. And it is as apposite to the practice of art as it is to that of science.

In search of truth

For what, then, do we search? The answer, of course, is truth. In a sustainable world research never ends because it is, most fundamentally, a search for truth. Without this commitment to truth, research would be cast adrift, like a lost spacecraft with no recollection of its mother planet and no clue as to where it is heading. Yet in this cynical and untrusting age, truth is often considered a dangerous if not deluded idea, best kept inside scare quotes. For many, the very mention of truth conjures up memories of the tyranny wrought, throughout history, by those claiming to be its masters and to act as its worldly ambassadors, invariably with calamitous consequences for all concerned. We should not, however, blame truth for the atrocities committed in its name. The fault lies in its totalization, its conversion into a monolith that stands eternal like a monument, timeless and fully formed. Research, to the contrary, rests on the acknowledgement that we can never master truth, any more than we can conquer life. Such conquest is for immortals. But for us, mortal beings, truth is always greater than we are, always beckoning from beyond the horizons of our present knowledge and understanding. The role of research, then, is to offer an imaginative opening to truth.

Yet by the same token, truth should on no account be confused with fact. The fact stops us in our tracks and blocks our way. “This is how it is,” it says to us; “proceed no further!” But even if the facts of a case may be incontrovertibly established, its truth lives on. For what appears to us in the first instance as data points or stoppages turn out when we search again – that is, in our re-search – to be openings that let us in. It is as though the fact rotated by ninety degrees, like a door on opening, so that it no longer confronts us face-on but aligns itself longitudinally with our own movements. And where the fact leads, we follow. “Come with us”, it says. What had once put an end to our search then reappears, in re-search, as a new beginning, a way into a world that is not already formed, but itself undergoing formation. It is not that we have broken through the surface of the world to discover its hidden secrets. Rather, as the doors of perception open, and as we join with things in the relations and processes of their formation, the surface itself vanishes. The truth of this world, then, is not to be found “out there”, established by reference to the objective facts but is disclosed from within. It is indeed the very matrix of our existence as worldly beings. We can have no knowledge of this truth save by being in it. Knowing, in short, unfolds from the inside of being.

This conclusion will naturally be anathema to those who hold that true knowledge of the world can be had only by detaching ourselves from it and looking from a distance. For them, objectivity is the very hallmark of truth. It is indeed understandable that in a world where facts often appear divorced from any kind of observation, where they can be invented on a whim, propagated through mass media, and manipulated to suit the interests of the powerful regardless of their veracity, we should be anxious about the fate of truth. To many, it seems that in this era of post-truth, we have lost our grip on reality. But while we are right to insist that there can be no proper facts without observation, we are wrong, I believe, to suppose that observation stops at objectivity. For to observe, it is not enough merely to look at things. We have to join with them, and to follow. That’s what observation means: to follow attentively – whether by watching, listening or feeling – what someone or something else is doing.Footnote9 And it is precisely as observation goes beyond objectification that truth goes beyond the facts. This is the moment, in our observations, when the things with which we study begin to tell us how to observe. In allowing ourselves into their presence rather than holding them at arm’s length – in attending to them – we find that they are also guiding our attention. Attending to these ways, we also respond to them. “The power of the real”, as architectural theorist Lars Spuybroek (Citation2020, 193) writes, “is that we will never get an answer; it is we who have to respond.”Footnote10 Research, then, becomes a practice of correspondence, and of care. It is a labour of love, giving back what we owe to the world for our own existence as beings within it.

Ending with the conversation

Finally, what does all this mean for democracy and citizenship? It cannot, for one thing, mean democracy in the sense of a headcount, which sorts everyone into those with common or opposed interests. In a sustainable democracy – one with room for everyone and everything, now and forever – people cannot be counted, and nor can things. Yet in their conjoint action and affective correspondence, they constitute a public. As political theorist Jane Bennett (Citation2010, 101) writes, after John Dewey, “publics are groups of bodies with the capacity to affect and be affected”.Footnote11 Whether human or nonhuman, these are bodies in conversation – bodies whose presence is felt by way of their voices as they mix and mingle in the medium. In the democratic conversation, each has something to give, something to contribute, precisely because all are different. Together they comprise what the philosopher Alphonso Lingis (Citation1994), in an apt turn of phrase, calls “the community of those who have nothing in common”. The meaning of citizenship follows from this. It is about learning to live together in difference. For within a democratic community that is open-ended and unbounded rather than closed in the defence of common interests, citizenship arises not as a right or entitlement, given from the start, but as something you have to work at. This is the work of commoning; not the discovery of what you have in common to begin with, but the imaginative act of casting your experience forward, along ways that join with others in carrying on a life together.Footnote12 Only then can citizenship be truly sustainable. The road to sustainability, in short, lies in the conversations of life.

Imagining the world as a plenum, I believe, affords a way of thinking about democracy and citizenship that could give hope to future generations. At the present juncture, however, this way of thinking has been pushed to the margins, above all by the relentless expansion of big science, aided and abetted by state actors and multinational corporations. And with it has gone the question from which all inquiry must begin: how ought we to live? Big science is not interested in this question because it believes it can already deliver the answer – or if not already, then in a future within its sights. But it has no answer for what lies beyond its predictive horizons. When the dinosaurs went extinct, it was the small mammals that inherited the earth, among them the weasel. The most famous weasel in history could turn out to be the one that bit through an electric cable, putting the largest machine ever built – CERN’s large hadron collider – out of action for a week.Footnote13 The collider is perhaps the greatest expression of scientific hubris we have seen, dedicated as it is to discovering the final truth of the universe, one that will leave us mortals with no place to be. It is the delusional project of our time, truly a machine for the end of the world. But the eventual collapse of big science – no less inevitable than the collapse of the global economy that sustains it – will not bring the world to an end. It will, instead, inaugurate a new beginning. A time will come beyond the Anthropocene. For that, our weaselly hero gave his life. We must ensure the sacrifice was not in vain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 I am most grateful to Claudia Zeiske, of Deveron Arts, without whose initiative this essay would never have been written. An earlier version of the essay, entitled “The Sustainability of Everything”, was published as Chapter 21 of my book Imagining for Real: Essays on Creation, Attention and Correspondence (London: Routledge, 2022, 325–336).

2 The rationale of modelling the ocean as a totality, with a capacity to accommodate a finite number of waves, is nicely illustrated in an anecdote told by Stefan Helmreich. At the First International Australasian Conference on Wave Science, held in Newcastle, Australia, in 2014, Helmreich put the question “How many waves are there in the ocean?” to scientist Alexander Babanin. Without a moment’s hesitation, Babanin proceeded to work out that if oceanic waves are, on average, 100 metres long, and if their crests are spaced, again on average, 100 metres apart, then the average wave covers an area of 104 square metres. Given that the world’s oceans extend over 1016 square metres, Babanin arrived at an estimate of 1012: a trillion waves (Helmreich Citation2014, 266).

3 In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED, also known as the Brundtland Commission) defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED Citation1987).

4 On the distinction between progress and sustainability, see Ingold (Citation2024, 87–91).

5 This is to extend to design an argument that I have made elsewhere for thought: “Indeed it is largely in the attempt to think themselves out of history, and to evade the implications of the passage of time, that human beings have created a history of thought” (Ingold Citation2016, 142).

6 In the original German, Klee wrote: “Kunst gibt nicht das Sichtbare wieder, so ndern macht sichtbar”. This lends itself to translation in many ways; the one I use here comes from the English-language version of his notebooks (Klee Citation1961, 76).

7 This conclusion aligns closely with that of anthropologist Arturo Escobar, who sees design for sustainability as revolving “around a vision of the Earth as a living whole that is always emerging out of the manifold biophysical, human, and spiritual elements and relations that make it up”. Drawing on the philosophy of William James, he calls this living whole the “pluriverse”. I have much the same idea in mind with the plenum (Escobar Citation2011, 139).

8 Anthropologist Michael Pröpper (Citation2017) commences his comprehensive overview of the potential contributions of art to sustainability science with the remark that “academic sustainability science has so far been largely oblivious to the potential contribution of art”.

9 The primary meaning of “to observe”, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “To act in accordance with, fulfil; to keep, maintain, or follow” (www.oed.com/dictionary/observe_v?tab = meaning_and_use#34130923, accessed 28th December 2023). The term is nevertheless contested. Philosopher Anna Bloom-Christen, for example, notes its technical usage in late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century France, to refer to the methods of police surveillance of the absolutist state (Bloom-Christen Citation2024, 63).

10 In a recent article, anthropologist Didier Fassin argues that truth is profoundly and permanently in tension with the real. “Reality is horizontal, existing on the surface of fact. Truth is vertical, discovered in the depths of inquiry” (Fassin Citation2014, 41). For reasons that should now be clear, I do not accept this distinction. For one thing, to exclude from reality everything that cannot be ascertained by the facts is to consign the greater part of experience to the realm of fiction. And for another, in my understanding the facts are not a cover-up, concealing a truth that lies beneath. Truth, indeed, is neither vertically nor horizontally arrayed: to reach it means going not down or across but along. The search for truth is a process of longing (Ingold Citation2022, 277–278).

11 Dewey’s essay The Public and its Problems was first published in 1927 (Dewey Citation2012).

12 The Canadian writer and activist Heather Menzies speaks of commoning in just this sense, as “a way of doing and organizing things as implicated participants … immersed in the here and now of living habitat” (Menzies Citation2014, 122–123, original emphasis). See also Bollier and Helfrich (Citation2015), who entitle their collection Patterns of Commoning.

13 The animal in question was in fact a beech marten, a member of the weasel family. This attack, on 29 April 2016, was only the first. A few months later, on 21 November, another marten struck. Instantly electrocuted on contact with the 18,000-volt cable, the animal’s singed body was recovered and put on display at the Rotterdam Natural History Museum. See www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jan/27/cerns-electrocuted-weasel-display-rotterdam-natural-history-museum (accessed 28th December 2023).

References

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bloch, Maurice. 2012. Anthropology and the Cognitive Challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bloom-Christen, Anna. 2024. “In the Slipstream of Participation: Attention and Intention in Anthropological Fieldwork.” In One World Anthropology and Beyond: A Multidisciplinary Engagement with the Work of Tim Ingold, edited by Martin Porr, and Niels Weidtmann, 60–75. London: Routledge.

- Bollier, David, and Silke Helfrich2015. Patterns of Commoning. Amherst, MA: Levellers Press.

- Brand, Stewart. 1994. How Buildings Learn: What Happens to Them After They’re Built. New York: Penguin.

- Dewey, John. 2012. The Public and Its Problems: An Essay in Political Inquiry, edited by Melvin L. Rogers. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2011. “Sustainability: Design for the Pluriverse.” Development 54 (2): 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.28.

- Fassin, Didier. 2014. “True Life, Real Lives: Revisiting the Boundaries Between Ethnography and Fiction.” American Ethnologist 41 (1): 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12059.

- Feld, Steven. 1996. “Waterfalls of Song: An Acoustemology of Place Resounding in Bosavi, Papua New Guinea.” In Senses of Place, edited by Steven Feld, and Keith H. Basso, 91–135. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

- Helmreich, Stefan. 2014. “Waves: An Anthropology of Scientific Things.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (3): 265–284. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau4.3.016.

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2015. The Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2016. Evolution and Social Life. New Edition. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2022. Imagining for Real: Essays on Creation, Attention and Correspondence. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2024. The Rise and Fall of Generation Now. Cambridge: Polity.

- Klee, Paul. 1961. Notebooks, Volume 1: The Thinking Eye (Trans. Ralf Manheim). London: Lund Humphries.

- Klee, Paul. 1973. Notebooks, Volume 2: The Nature of Nature (Trans. Heinz Norden). London: Lund Humphries.

- Knight, John. 1998. “The Second Life of Trees: Family Forestry in Upland Japan.” In The Social Life of Trees, edited by Laura Rival, 197–218. Oxford: Berg.

- Lingis, Alphonso. 1994. The Community of Those Who Have Nothing in Common. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- McLean, Stuart. 2009. “Stories and Cosmogonies: Imagining Creativity Beyond ‘Nature’ and ‘Culture’.” Cultural Anthropology 24: 213–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2009.01130.x.

- Menzies, Heather. 2014. Reclaiming the Commons for the Common Ground. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

- Pröpper, Michael H. 2017. “Sustainability Science as If the World Mattered: Sketching an Art Contribution by Comparison.” Ecology and Society 22 (3): 31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09359-220331.

- Spuybroek, Lars. 2020. Grace and Gravity: Architectures of the Figure. London: Bloomsbury.

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Whitehead, Alfred N. 1929. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.