ABSTRACT

Professional expertise is a legitimate cornerstone of modern global culture. The unfolding of the polycrisis, however, arguably destabilizes expertise as a privileged and uniform position of knowledge production. Even sustainability expertise, while considered part of the solution, is arguably part of the problem, due to its structural links to environmentally detrimental technological practices. Hence technology relations in expertise are explored by autoethnography. Expert attitudes towards technology are traditionally demarcated between optimistic technocrats and critical humanists, but a third category is suggested, which embodies determined technology criticism, anti-colonialism and post-professional ethos. This peripheral expert position, labelled spurner, may seem dubious and dark from the point of view of paradigmatic expertise. But since the polycrisis calls for plural and inclusive modes of expertise, peripheral knowledge and skills should be seen as one end in the spectrum of possible sustainable expertise. True plurality means that hardly any final unification or mutual consensus in sustainability expertise seems plausible or even desirable. However, due to the polycrisis, many experts may have to reconsider what role their professions and technological progress in general play in the unfolding events. Recognizing peripheral “grey zone” expertise may foster such self-reflection in individual experts and in expert cultures.

Introduction

Expertise is a legitimate cornerstone of modern global technoscience and society at large (see, e.g. Watson Citation2021). The term expert emerged during industrialization referring to someone not only with experience but also with a specialization, i.e. qualification for a particular task (Eräsaari Citation2009). This modern definition of expertise is one that combines science (knowledge), institutions (trustworthiness) and professions (duties) (Eräsaari Citation2009, 62). By sustainability expertise, we mean not only those working with sustainability sciences, but more inclusively the cumulative know-how in any expert field aiming to contribute to solving sustainability challenges. This not only means strictly sustainability sciences or natural and technical sciences, but also social sciences, humanities and the arts. As practically every job and profession are claimed to need changes for the sustainable transition (Houtbeckers and Taipale Citation2017), experts in every field are invited to reflect their own practices as well.

Our era is defined by the global polycrisis, which refers to “the causal entanglement of crises in multiple global systems [such as environment, economy, health and security] that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects” (Lawrence, Janzwood, and Homer-Dixon Citation2022, 9). And as the polycrisis is found to destabilize the societies, climates and ecosystems (Henig and Knight Citation2023) where experts live and work, Latour’s (Citation2018) observation that “the offices, universities, laboratories, instruments, academies, in short, the entire circuit of production and validation of knowledge has never left the old terrestrial soil” (67–68, emphasis in original) is of relevance in the quest of understanding sustainability expertise.

In this article, we ask what sustainability expertise is and how sustainability experts, like ourselves, are partly responsible for the sustenance of the polycrisis. Such a point of departure may seem overly self-critical, but precisely because sustainability expertise aims to be part of the solution, individual experts may be very sensitive to privilege, compliance, hypocrisy, or other such feelings which remind us that we might regardless be part of the problem (Thierry et al. Citation2023). These questions have been raised by everyday observations of how expert professions comply (or do not comply) with sustainable practices and how social movements, like Extinction Rebellion, have brought together experts, such as teachers, engineers and ecologists, who feel that their professional agency in academia or other institutions is insufficient. Compared to many fields of labour, sustainability experts may be expected to have reflective autonomy regarding the means and ends of their profession.

Even if modern expertise has certain indisputable stability and legitimacy, it has been frequently criticized by scholars and civil society. It has been argued that scientific-technical expertise has its roots in patriarchal and mechanistic world views, and is thus linked to the age-old dominion over women and nature (Arendt Citation1998; Merchant Citation2015). The post-war period gave rise to debates over technocracy and democracy (Noble Citation1979), and the emerging environmental concern questioned industrial society’s ability to assess and control the risks of its own making (so-called wicked problems) (Beck Citation2009). Also, there seems to be no unbiased or neutral position for expertise, as institutional science and technology are structurally linked to economic and political forces (Illich Citation1977; Saikkonen and Väliverronen Citation2022). Professional expertise is thus not innocent, nor is it omnipotent. Hence, the unfolding of the polycrisis arguably destabilizes sustainability expertise as a privileged and uniform position of knowledge production.

These oscillations – evoked by the polycrisis – where individual experts feel the need to seek epistemically and ethically coherent positions, and where the ranks of expert professions may even divide, have been called “ecological cracks” (Beck Citation1994, 49). Alongside Eräsaari (Citation2009, 56), we find that many sustainability experts personally feel this “lost coherence of the modern epoch” and this undoubtedly affects “the conditions and performances of expert knowledge”. Yet at the same time, institutionalized professional expertise may not provide the faculties to navigate such existential problems (Eräsaari Citation2009). However, we suggest that for sustainability expertise, such profound challenges concerning the life worlds of experts may mean taking distance to progressivist and techno-optimistic views traditionally integral to expertise. In other words, “sustainability expertise” challenges the way in which expertise is understood within the modern framing of it.

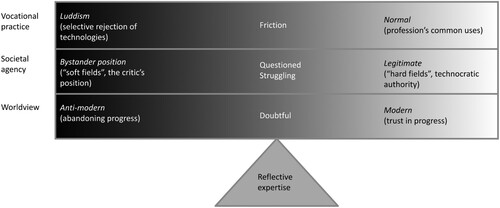

In our recent autoethnographic study (Takkinen and Heikkurinen Citation2022), we examined critical self-reflection experienced in sustainability expertise and three archetypes of expertise. This study revealed a “grey zone”, in contrast to the light and bright of the modern and its dark negation (see , with further elaboration in the “Findings” section). The archetypes of sustainability expertise were named the Technocrat, Humanist and Spurner. In this article, we rewrite our findings in English and conceptualize the grey zone sustainability expertise as (1) practice, a discomfort in using of some technologies in expert professions, (2) agency, a challenged legitimacy of “soft” expertise in contrast to progressivist and techno-scientific agents and (3) world-view, a deep cultural doubt towards (eco)modernization and its expert-led progressivist telos. We propose that even if such positioning is conceivable and probably even common amongst sustainability experts (in a darker or lighter shade of grey), expert discourse has no means to express or share these doubts towards technological practices or modernist cultural hegemony. Furthermore, in a Dreyfus (Citation2014) spirit, we return to the root meaning of the word expert, namely experience, which for us essentially means (a) accumulated experience, but it also has an (b) experiential aspect of trial and learning. Finally, expertise means self-reflective (c) attentiveness to personal experiences when making meta-level observations of one’s own expertise.

Methodological approach and materials

Autoethnography is a self-reflective method that studies cultural phenomena starting with the autoethnographer’s personal experiences (Adams, Jones, and Ellis Citation2015). Autoethnography has been used to study silent or overlooked topics that may be marginalized by cultural normality (such as race and gender) or perceived as taboo (such as illness). We use autoethnography to study sustainability expertise as a cultural phenomenon, especially in the context of technology. Despite today’s abundant technology hype in marketing and popular futurology, thorough questioning of technology is often nullified by conformism, ridicule and self-censorship, which is indicated by the frequent use of the clause “I’m not against technology but … ” (Wallgren and Toivakainen Citation2021). Owing to the taboo-like status of technology in modern societies – noted, among others, by scholars of technology (Ellul Citation1964; Skrbina Citation2014; Winner Citation1978) – an emphasis on technology is considered of high relevance for sustainability. Against this backdrop, it is no surprise that sustainability experts do not seem to have other framings to express their technology attitudes besides being optimistic about it, while other more-or-less pessimistic attitudes are discriminated against or even silenced (see Kerschner and Ehlers Citation2016; Saikkonen and Väliverronen Citation2022). Nonetheless, actual attitudes towards technology often vary considerably, also encompassing ambivalent and critical tones (Kerschner and Ehlers Citation2016; Mitcham Citation1994).

As sustainability experts’ relation to technology is a largely shared but also difficult issue, we found autoethnography a suitable method for illuminating the phenomenon. In autoethnography, personal experiences are analyzed using literature and reflective discussions, moving the analysis from personal to shared and cultural (Adams, Jones, and Ellis Citation2015, 1–19). As it often is the case with autoethnographies (Adams, Jones, and Ellis Citation2015, 33–34), our motivation is also to a great extent emancipatory, at least in the sense that those who relate to our analysis may find it helpful for their own self-reflection and practice. In studies of academic work in Finland, ecological themes, such as air travel, have been reflected on a personal basis (Heikkurinen Citation2012). Also, human-technology relations have been approached autoethnographically, thematizing questions, such as the possibility of intentional non-use of certain technologies (Lucero Citation2018), and the methodological challenges in studying ubiquitous technologies (Piattoeva and Saari Citation2022). Because technical engagements have a deep social and cultural dimension (Mitcham Citation1994), each individual has only limited autonomy to control their own everyday relation to technology, and in professional context this freedom is even more limited. That is arguably why the question of uneasy or unsustainable technology use should be brought from the personal sphere into contextualized discussions of culture.

Our analysis builds on autoethnographic vignettes, short depictions of personal experiences. These experiences are emotionally laden and something which “stay with” the author, evoking thoughts and further experiences (Adams, Jones, and Ellis Citation2015, 26–29). In this article, the vignettes and the first-person narration are solely from the first author (PT), but the analysis is produced in discussions and cooperation between both authors sharing similar professional and ethical concerns on expertise. In this kind of shared autoethnography, mutual trust and understanding is essential, but so is critical honesty, allowing the ethnographers remain open to the related uncertainties and do not end up creating polished master narratives (cf. Breault Citation2016).

Reflecting back on the writing process of our autoethnography, we started by pondering one mundane event – a meeting of sustainability-concerned philosophers – where one philosopher stated that “each and every laptop-wielding expert is taking this world closer to destruction” (Takkinen and Heikkurinen Citation2022, 16). This claim seemed to suggest that all professional expertise is inseparably tied to unsustainable cultural practices, and we both found it plausible in the sense that from a historical point of view it might be true and politically relevant. Yet we also understood how accepting this claim would amass huge amounts of practical and ethical problems in the personal horizon of any sustainability expert. For most sustainability experts, a personal laptop is probably more of a consumer choice than a philosophical question (Skrbina Citation2014, 3). Even in such contexts where professional philosophers attempt to integrate environmental issues into their work, merely themes such as conference flights and sustainable catering at academic events have been thematized, while the attitude towards digital devices is neutral or positive (see, e.g. Philosophers for Sustainability, Citationn.d.). Yet there are weighty reasons to question the leading role of technological progress in sustainability efforts and instead foster a consciously atechnological ethos and mode of being (Heikkurinen Citation2018; Citation2021). In the 1990s neo-Luddite discourse, for example, environmentally concerned and technologically critical scholars such as Sigmund Kvaløy and David Suzuki expressed uneasiness towards the computerization of academic work or appearing on television broadcasts. Such thinkers wanted, in their personal practice, to reject the latest technologies due to their wider environmental and cultural consequences, but found it difficult (Mills Citation1997).

The expert’s relation to technology both personally (use of professional tools) and publicly (technocratic legitimacy) intertwine in ways that are not trivial. Notable critics of technology have emphasized the enabling role of professional expertise in highly technological and environmentally detrimental cultural change (Ellul Citation1964; Illich Citation1977). At the same time expert work itself has become increasingly dependent on high technology. Illich uses the term “radical monopoly” for such situations where older and lower technology practices are replaced by industrial products, such as cycling in a car-dominated city or digital non-use in academia, even if the older practices as such are perfectly suitable and ecologically and socially desirable (Illich Citation1973). Expertise is in a technologically intensive loop, as it both defines this monopoly and is defined by it: “Monopoly is hard to get rid of when it has frozen not only the shape of the physical world but also the range of behavior and of imagination” (Illich Citation1973, 70). What we next illuminate autoethnographically is our personal struggle in this loop. Having started from a seemingly trivial – yet personally significant – question of an individual expert’s laptop use, our autoethnographic analysis snowballed into exploring technologically hegemonic discourse and structures in (expert) culture.

Findings

Our analysis is summarized here in . From top to bottom, by starting from the use of technology in expert work (practice), we ended up outlining issues concerning legitimacy of such expert positioning (agency) and deep emotional and onto-existential positions (world-view) that might guide these choices. From right to left, we portrayed paradigmatic, technologically optimistic and technocratically legitimate expertise as symbolically wielding the light of Enlightenment (white). In the middle is the expertise that may face friction in vocational practices, struggle for legitimacy in terms of agency and doubt about modern world-views (grey zone). Expertise positioned in the left side (black) means intentional refusal or unwilling exclusion from the paradigmatic and legitimate expertise.

describes the dynamic nature of experiences emerging in the interface and interaction between expertise and culture’s technological normality. First, the colours form a sliding scale and not separated pigeonholes, which means that actual expertise is not static in its relation to technology but rather dynamic, and possibly taking many different shades. Second, even if the shades on different levels tend to cohere by grouping into the spectrum’s white, grey or black areas, there may also be substantial discrepancies. For example, one expert might practise non-use of certain technologies for cognitive reasons (digital detox), and still believe in modern progress, thus experiencing both the black and white shades of the scale. Similarly, an expert who has no faith in eco-modern visions might be unable to reject the latest technological practices inherent in their profession. Such discrepancies reveal the multi-layered and often ambivalent relation to technology. Third, in the bottom is the triangular fulcrum (reflective expertise), which itself is outside of the above scale and is thus positioned to reflect and balance the above variables. The dynamic potential of means that reflective expertise is aware of its own positioning and has some informed flexibility regarding practices, agency and world-view.

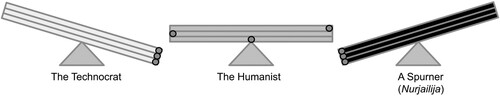

Finally, in , we illustrate some different expert positions that can be presented in this scale. We present three archetypes of sustainability expertise: Technocrat, Humanist and Spurner. The bars in these figures are compressed versions of the above , and the dots indicate the positioning in the scale.

The Technocrat is the paradigmatic expert role, often representing technical or natural sciences. Its practice is often tied to the latest laboratories and instruments, making the rejection of professional technologies difficult or oxymoronic. The Technocrat might be ideologically dedicated to – or unreflectively counting on – scientific-technical progress, and trust that modernity will solve ecological crises. In the figure the bar is white and tilted right, illustrating its legitimate but possibly unreflective position.

The Humanist in this example is indifferent about everyday technological practices, using the tools common to the profession. However, because they represent “soft fields”, the Humanist carries less societal legitimacy and feels like an excluded bystander, while the “hard fields” of natural science, technology and economy define the nature of sustainable transitions. The Humanist is more of a critic of culture than its guiding expert. At the level of world-view, the Humanist may find modern optimism too naive and antimodern pessimism too bleak, and thus navigate between them.

A Spurner (Finnish: nurjailija) is in many ways far from paradigmatic expertise. To illustrate its non-definite character represented by conceptual language, it comes with an indefinite article. Nurjailija is a Finnish neologism and personal character coined by Pylkkö (Citation2009, 46–75). The word consists of two parts, nurja and ilija, where nurja is an adjective, meaning things like “wrong side of something”, “twisted” or “incongruous”, and -ilija is a noun suffix which transforms the connected adjective into an agent noun (i.e. a doer of something). For us, nurjailija spontaneously brings to mind someone who has the habit of doing the wrong thing or behaving in unaccepted fashion. All this intentional social friction has an ironic and slightly malevolent tone. In addition to the spontaneous tone of the term, nurjailija is linked to Pylkkö’s philosophical project where this character has a role to play in local Finnish thinking (in contrast to universalistic European intellectual tradition). Aware of the limited translatability of local languages and meanings, we sketch nurjailija generally as an intellectual or expert, who is a native of a peripheral culture (in contrast to Eurocentric and anglophone cultural areas) and who feels an insoluble conflict between one’s local culture and adopted Eurocentric culture.

For non-Finnish audiences, or for many Finns themselves, it probably sounds counterintuitive to claim that this modern welfare state and EU member is in some relevant sense non-European. But historically, Finns followed Europe relatively late in their Christianization, industrialization and modernization:

Uralic groups share a history of being colonized, of being forcibly Europeanized, Russianized, Westernized, and the consequent post-colonialist situation. People speaking Finnish can recognize a pressure toward Indo-Europeanization, as the speakers of other Uralic languages feel a pressure toward Russianization. (Salminen and Vadén Citation2015, 114)

Nurjailija adopts an anticolonial sentiment and uses their knowledge of the Eurocentric culture to strengthen and positively contribute to their local culture. Nurjailija is an educated expert or otherwise culturally creative and contributing character who may have gone through some sort of disillusionment possibly due to cosmopolitan rootlessness or modernity’s looming ecological crises. In this sense the term spurner comes close to nurjailija, as both mean refusing, abandoning or turning one’s back, possibly with a despising tone. The fact that such refusal often expresses negative emotional tension relates to the hegemonic status of international intellectual, scientific and technological trends which, in peripheral contexts, often seem so obviously agreeable that rejecting them is necessarily antagonistic.Footnote1

In Pylkkö’s words:

Nurjailija must explore and map European culture all over again in order to find out which of its elements represent the solid core of European metaphysics, and which ones represent the current that is alien or even hostile to it. Nurjailija must find allies, who can participate in crumbling European mental colonization. (Pylkkö Citation2009, 65, translation from Finnish by PT)

Returning to , the Spurner may intentionally practise non-use of some common tools, instruments and technologies, such as digital devices or air travel. They may be a critical bystander of progressivist/technocrat sustainability efforts. In their world-view, a Spurner might doubt modernization in the sense that (a) it is technologically unfeasible and ecologically destructive project and/or (b) even if modernity could be reshaped into a sustainable form, it is existentially undesirable for the human condition. In sum, as this “dark” position tilts heavily left, the Spurner is very reflective and critical about the limitations of technological and scientific knowledge and practice. However, this position may not be recognized as expertise and thus might be ruled out from experts’ legitimacy in sustainability discourse.

The figures (the grey zone and expert archetypes) above are by no means definitive, but merely heuristic tools. Also, we are not suggesting any preferred expert position, such as the balanced middle way of the Humanist (see Heikkurinen Citation2017). By practising autoethnography, we are doing empirical work, and we merely suggest that the above scales and variations are possible for many sustainability experts. Since our analysis has argumentative elements alongside autoethnographic description, it might justifiably raise important theoretical questions, such as “Should not the spearhead of the critique be aimed at capitalist structures instead of technology and modernity as such?” or “Is it strategically wise to frame the non-technocratic sustainability efforts as darkness-oriented?” Such questions are beyond the reach of this autoethnography, for our analysis is not meant to be an exhaustive argument, but merely a self-reflective account of how we personally experienced certain moments and positions of expertise. Thus, even if one of our aims is to render the Spurner expertise visible as a possible position, our deeper aim is to encourage even wider self-reflection, discussion and debate of possible and desirable kinds of sustainability expertise. Still, we do claim that instead of static balancing or permanently tilting right (expertise without reflection) or left (reflection without expertise) most experts probably feel the setting swinging from side to side in different phases of their careers and personal life. Here we are after this meta-expertise, the ability to reflect and learn from these swings and changes in one’s expert position. This goes beyond strictly professional skills and requires autoethnographic self-reflection and philosophical sensitivity.

Discussion

Tenerife 2017. During dinner on the first day of the conference, I get to know researchers from Southern Europe who work with high-performance computing. When they learn that my field is philosophy, they spontaneously burst into laughter. One of them tries to rectify the situation by saying: “Well that’s nothing, but hear this: I’ve heard that we even have one architect, ha-ha!”

During my (first author) graduate studies, I attended an international conference, attracting mostly Master and PhD students from the fields of natural and technical sciences to discuss sustainability issues. A philosophy professor invited us to join, as a few of us in our faculty were interested in the questions of technology and sustainability.

It is hard to put one’s finger on the defining moments when a university student learns the many differences between science and humanities. However, by the time of the above event, I was well aware of some implications of that divide. During my student years, I had been told more than once that philosophy does not produce any practical utility for society, or that it should not be publicly funded. Even if I had have misinterpreted the situation, and the laughter I encountered at the cocktail dinner was actually caused by a genuine surprise of encountering a philosopher in such a context, I could not help but feel that my legitimacy as a fellow enquirer of sustainability issues was blatantly nullified.

These personal occurrences have deep historical roots. For centuries in Western culture there has been tension between early forms of humanistic thinking and technical and empirical sciences (Mitcham Citation1994; see also von Wright [Citation1976] Citation1977; [Citation1978] Citation1981). These tensions surfaced as industrialization revolutionarily altered the landscape and society, inducing reactions like Thomas Carlyle’s essay “Signs of the Times” (1829) condemning the technological age, and Timothy Walker’s response “Defence of Mechanical Philosophy” (1831) praising the triumph of science and technology (see, e.g. Nichols Citation1976). Later C.P. Snow (Citation1959) presented his highly influential analysis of “two cultures” in science, namely those of literary intellectuals and natural scientists, whose moral and psychological climate differ so much as if separated by an ocean. Even if not precisely autoethnographic, Snow’s observations had emerged from his personal involvement in both of these scholarly cultures. This polar difference, particularly amongst young scholars, is manifested in “hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding” (4).

Snow (Citation1959) observed that in the post-war West science and humanities were in opposite cultural trajectories, where young scientists felt they belonged in a rising culture, with prospects of economic prosperity and social respect, while young humanist scholars could expect much less income and respect, should they even achieve a funded position (17–18). Certainly, my experience at the Tenerife conference was characterized by the awe of the fact that the conference attendance, five-star hotel accommodation and flights were fully provided for us attendees. Such luxury was unheard of during my years of study in the field of humanities, and I could not help but feel that I was some sort of impostor.

Another interesting notion from Snow (Citation1959) is that humanistic intellectuals are “natural Luddites”, as they are traditionally uninterested and critical of the industrial revolution (22–28). Regarding his views on technology, Snow clearly aligns himself with the Enlightenment tradition and competitive spirit of scientific and technological progress of the post-war era great industrial powers. That era started the Great Acceleration – the current technologically intensive phase of human history – when the total mass of the technosphere exceeded that of the biosphere (Elhacham et al. Citation2020), and the ecological harms of industrialization have snowballed into a polycrisis (Lawrence, Janzwood, and Homer-Dixon Citation2022, 9). It seems Snow did not have the last word in scolding Luddite intellectuals, since the triumph of techno-science may again be questioned, this time in the context of ecological crises. This old discourse is ongoing and lively: as we worked on this manuscript, science and technology scholar Andy Stirling gave a keynote lecture at Sustainability Science Days 2023 at the University of Helsinki, describing the momentum driving ecological crises as “colonial modernity”. According to Stirling, such a mindset assumes techno-scientific controllability of global challenges, thus cementing the legitimacy of technocratic expertise. Stirling argued that due to the complexity of the ecological crises: “The world is not a machine. There is no cockpit” (Stirling Citation2023), and called for more plural and humble sustainability expertise (see also Stirling Citation2010).

Pylkkö (Citation2012), in critiquing the arrogantly scientistic world-view of popularized science literature – and concurrent disparagement of humanistic scholarly fields – also reminds us that “natural sciences and their research institutions are (for example through their funding and technological practices) committed themselves to the Western consumerist society, economic growth, technological progress and thus hopelessly engaged in inflicting the ecological catastrophe” (70).

In sum, today’s sustainability expertise inherits many historical tensions, felt by actual students and experts. The above experience made me feel that my emerging expertise was questioned and delegitimized. Instead of trying to convince myself and others that I belonged there, I felt – like a Spurner – the creeping urge to turn my back to the technological visions of these respected and recognized fields. The question is, how could skilful sustainability expertise navigate and develop in such ambivalent situations?

Tenerife 2017. We make a day trip to see the Teide volcano and a supercomputer of the same name, which is a technical marvel of the island. During the bus ride I talk with a fellow conference attendee who studies a technical field. He demands to know exactly what philosophy of technology studies. I may overinterpret, but maybe he is annoyed by the fact that some non-technical field studies and comments about technology. He shares with me the fact that the supercomputer that we are about to visit is actually already four years old and has long since dropped out of the chart of the five hundred most powerful supercomputers.

In 1972 the first-ever supercomputer used system dynamics to calculate “world models” according to which the expansive trends of industrialization will lead to a collapse even in those scenarios where technological progress exceeds even the wildest expectations. The models have corresponded quite accurately to the actual developments (Turner Citation2008). The results were presented in the famous report Limits to Growth, whose authors committed a whole chapter to anticipate and debunk fierce technological optimism that they correctly estimated would surface: “We have felt it necessary to dwell so long on an analysis of technology here because we have found that technological optimism is the most common and the most dangerous reaction to our findings from the world model” (Meadows et al. Citation1972, 154). The authors saw the problems rooted deep in our world-view: “Since the recent history of a large part of human society has been so continuously successful, it is quite natural that many people expect technological breakthroughs to go on raising physical ceilings indefinitely. These people speak about the future with resounding technological optimism” (Meadows et al. Citation1972, 129). The estimate was correct, and in 1987 the growth and technology optimism introduced by the Brundtland Report as sustainable development marginalized the critique to growth (Bonnedahl, Heikkurinen, and Paavola Citation2022; Mol and Spaargaren Citation2000).

It takes only a pinch of imagination to consider the message from the first supercomputer as a historical oracle moment for humanity. The scientific-technical system predicted – based on calculations and not on cultural pessimism of intellectuals – that unless limited, its expansion will lead to ruin. But there I was, decades later on my way to see a supercomputer one hundred million times faster than its pessimistic ancestor, at a conference that prepares future experts to overcome the limits to growth. Philosophical questions started to develop in my mind. Are we today, with all of humanity’s combined computing power, any closer to sustainability than in the 1970s? Are we equally deaf to calls for limits, be it humanist scholars or supercomputers who issue them? Finally, these thoughts condense into asking if technological optimism is at all falsifiable, that is, disprovable by any empirical evidence or observation.

The fact that the total mass of the technosphere already exceeds that of the biosphere (Elhacham et al. Citation2020) combined with the fact that economic and technological growth are not – despite high hopes – being decoupled from environmental degradation (Haberl et al. Citation2020; Hickel and Kallis Citation2020; Vadén et al. Citation2020) should be weighty enough reasons to reconsider the role of technology in sustainability efforts (Heikkurinen and Ruuska Citation2021). The Limits to Growth report resonates with Stirling’s notion above (the world is not a machine), when referring Hardin’s definition from the famous article “Tragedy of the Commons” (1968): “A technical solution may be defined as ‘one that requires a change only in the techniques of the natural sciences, demanding little or nothing in the way of change in human values or ideas of morality.’ Numerous problems today have no technical solutions” (Meadows et al. Citation1972, 150). Here we can strike a wedge between the seemingly seamless union of science and technology: sustainability sciences and empirical observation do not support the claim that purely technological change can result in sustainability. In other words, scientistic technological optimism may be unscientific. After my experiences at the Tenerife conference, these lines of thought consolidate my self-esteem: besides the shaping of the physical world (natural and technical sciences), the shaping of the cultural world (arts, humanities and social sciences) is also needed. However, what was achieved by these reflections but more segregation between scientific cultures?

Hyrynslami 2020. I freeze on the spot in a dark forest. The black silhouette outlined in front of me must be a bear. I feel the fear rushing through my body. One part of me knows that it’s not a bear, but instead the exposed roots of a fallen spruce that I saw here during the day. And still the fear came, as I knew it would come.

I had a one-month stay at Mustarinda, an international residency that reaches towards a post-fossil culture by hosting researchers and artists. Mustarinda is located in Hyrynsalmi in North-Eastern Finland where during November (when I stayed there) the daytime between the sunrise and sunset is around six hours. The first half of the month was still snowless, so it was the darkest time of the year. As I worked in my writer’s room and looked out of the window, I often saw only the black wall of old spruces against the almost black sky.

Before going to the reasons why I wandered into the dark forest, a few remarks on the impressions that defined my experience in Mustarinda. First, Hyrynsalmi is a rural and sparsely populated municipality, and the residency is located almost 30 kilometres from the town centre. Residents were encouraged to arrive by slow travel (not flying) and offered a shared electric car ride to the grocery store once a week. The residency is itself a big old wooden house, surrounded by a nature reserve consisting of ancient spruce forest. The residency has made experiments towards self-sufficiency, such as installing various local energy technologies (Korpela and Majava Citation2020), practising food gardening and composting the residents’ leftovers and faeces. During my residency, there was a day when I estimated if I had enough oatmeal and coffee until our next grocery visit. There was an evening when we prepared the house for a forecasted autumn gale and possible electric blackouts. There was a morning after a heavy snowfall when everyone had to clear snow for the whole morning to open the way to the closest publicly maintained road. One evening we gathered outside the house to see the aurora borealis. Once every week we gathered together to bathe in the wood-heated sauna after which we had a dinner where everyone had prepared some dish to be shared with others. Such focal practices and experiences gain their meaningfulness from the absence of abundant energy, food or artificial light (Salminen and Vadén Citation2015), and they wither in the technologically intensive “device paradigm” (Borgmann Citation1984).

I did not have any kind of computer with me in Mustarinda, as I intended to work by reading books, discussing with others and writing in my notebook. Even if such neo-luddism might be a professional handicap at times, I still wanted to experiment with this intentional non-use. The choice was ethical, but also epistemological, as a reflective non-use is one way of studying technologies and their cultural role (Lachney and Dotson Citation2018; Winner Citation1978, 331). It was probably this anti-tech attitude combined with the hours of staring at the dark forest that gave me the urge to walk into the woods one night. Although I knew it would be scary, I left my flashlight, cell phone and such things in my room. I wanted not to be able to reach them, should my courage fail in the darkness. Only a few days earlier I had learned that the ancient Balto-Finnic word mustarinda actually denotes a bear deity and a hill covered by dark spruce forests and inhabited by ancestral and natural spirits (Majava Citation2014, 394). I assumed it had been decades or centuries since a human had last been killed by a bear in Finland. But despite my analytical mind trying to calm me in the dark forest I could not unthink the bear.

The atmosphere during my Mustarinda residency could be called peripheral in its geographical distance from cities, in its concrete and psychological darkness, in its low level of material and energy consumption and in my personal rejection of technologies such as the internet environment. It was pretty much the opposite atmosphere from the Tenerife conference (sunshine, five-star luxury, scientific self-confidence) some years earlier. And still, the residents working at Mustarinda are also sustainability experts. Latour (Citation2018, 34–35) fittingly describes how the Enlightenment-rooted modernity is an ascending movement (light), which in its wildest out-of-this-world visions imagine humanity unbound by terrestrial limits and realities. Latour then defines terrestriality as a desired descending movement (darkness), which redirects the spirit of discovery, innovation and emancipation into “digging deep down into the Earth” (81). Modern and terrestrial sustainability efforts differ greatly in their psychological mindsets, epistemic aspiration (libido sciendi) and scientific virtues: “these do not involve the same scientific adventures, the same laboratories, the same instruments, the same investigations, nor are the same researchers heading towards each of these two attractors [i.e. modernity or terrestrial]” (Latour Citation2018, 81).

Snow (Citation1959), despite his admittedly illustrative analysis of the problems in the two scientific cultures, eventually concluded that literary intellectuals should be more literate of natural sciences and stop lamenting the industrial revolution. Whereas Latour (Citation2018), although his archetypes (modern and terrestrial) differ somewhat from Snow’s scientists and intellectuals, does not see such need for consensus or unification. Instead, Latour argues that humanity cannot follow both directions, and after the modern rush, it is now time to “land on Earth” (89). As the visions of modernity and terrestriality are not unifiable in a neat consensus, each sustainability expert needs to navigate, choose between or be chosen by these mindsets and scientific adventures.

We suspect that the question of how a sustainability expert commits their libido sciendi, is closely connected to their personal world-view. But the world-view is not strictly personal in the sense of being individualistic or solipsistic. Instead it is mediated by practices, locations, natural surroundings, technological artefacts and the silent knowledge and attitudes of the expert communities, as Dreyfus (Citation2014) summarizes: “minds grow out of being-in-the-world” (124).

My experience at Mustarinda could also be described as presence, as I became more sensitive to the flows of everyday matter and energy that enabled my life and work there (Salminen and Vadén Citation2015). The creativity and knowledge production of the community was terrestrially oriented (Latour Citation2018) due to the sublime yet non-humanly alien presence of the old forest. Still, at the same time we were entangled in the polycrisis, as we followed the news of the possible re-election of President Donald Trump, while hoping that our isolated community would avoid the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic. Such presence shatters the impression of sustainability expertise operating unperturbed, as if from a stable, extra-terrestrial Archimedean point (Arendt Citation1998, 262; Takkinen, Pulkki, and Vadén Citation2023).

As Latour stated in his “personal defense of the Old Continent” (2018, 99–106), “to land is necessarily to land someplace” (99), and for Latour it meant Europe, that “can no longer claim to dictate the world order, but it can offer an example of what it means to rediscover inhabitable ground” (101). Be it in the continental Europe or the northern periphery, maybe it is precisely such cultural limbo and seeking that is necessary: the recognition of an unsustainable present and desire for something more rooted, be it tradition or yet imaginary ideal (Graeber Citation2007). As we are deprived of sustainable ties to the land, we can all be considered migrants (Latour Citation2018, 6), seeking a habitable place.

Hyrynsalmi 2020. The fly is trapped in the fly bottle by its positive phototaxis. It can only move toward light. Modernity bounces against a glass wall in its efforts to overcome its own unsustainability while removing suffering and evil by means of technological progress. They say there are fly bottles whose exit hole is painted black, so the fly would not dare to escape. The way out of modernity is painted black, so only the mad or the evil would go through. Nature was painted black by thinkers like Hobbes and since him every generation of intellectuals in turn. Had one a negative phototaxis, like a cockroach, one would instantly crawl into that darkness. To show the fly the way out of the fly bottle, the philosopher should teach the fly to become a cockroach.

The above Wittgenstein-inspired diary entry from the Mustarinda residency comments on the seeming dead end of the sustainability crisis: the most intuitive direction of movement – i.e. more intensive technological enterprise – is the one that entraps the fly. But even if one were to “show the fly the way out of the fly bottle”, as Wittgenstein (Citation1953, §309 emphasis added) intended, would the fly actually follow? In other words, would evidence and argumentation suffice in redirecting sustainability efforts from modern to terrestrial (or vice versa)? Is sustainability expertise predetermined by non-rational instinct or phototaxis into a certain trajectory? After all, are not natural scientists and modernists essentially different animals from literary intellectuals and terrestrials – like flies and cockroaches, who will always head in opposite directions? At least one could suggest that such Wittgensteinian reorientation in expertise would be very profound for the individual expert or expert culture, and would probably cause repercussions on many levels (see ).

Only afterwards, during our autoethnographic discussions, did I understand that my darkness-oriented residency visit was probably guided by my earlier readings on the subject. Antti Majava, an artist and sustainability scholar – and the founder of the Mustarinda residency – in his essay “Kohti pimeyttä” (Eng. Towards Darkness) 2014 suggests that the mindset of the ancient Mustarinda forest, black metal music and dark ecological thought could guide our aspirations when sustainably reconnecting with nature. After “increasing extreme weather conditions and the transition to a post-fossil energy economy” (Majava Citation2014, 403) have shattered the culturally hegemonic belief in endless growth and progress, the elements supporting the emerging world-view have necessarily a dark and peripheral tone.

Clear parallels from the anglophone discourse can be found in the Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto (Kingsnorth and Hine Citation2014), an invitation to sustainable cultural work, where not only “dark mountain” coincidentally means roughly “mustarinda”, but which also aims to put into words the feeling that “there is no way through the mess in which we find ourselves that doesn’t involve facing the darkness”. Such views that abandon the light of the Enlightenment and seek sustainability by moving downwards into darkness of the earth are not unheard of, and have been variously called “chthonic” (Goldsmith Citation1992), “humism”Footnote2 (Salminen and Vadén Citation2018) and “terrestrial” (Latour Citation2018).

The orientation towards darkness is sometimes considered either cliché aesthetics or misanthropic malevolence. However such dismissal overlooks the fact that often this orientation has lost its ability to believe in the final triumph and goodness of modernization. Turning into darkness means turning away from the artificial light of modernity, and admitting that “there is an underlying darkness at the root of everything we have built” (Kingsnorth and Hine Citation2014). Black metal could be called a sort of dark ecological writing, when it expresses the cosmic melancholy of nature (Wilson Citation2014), but it can also be perceptive of the modern horizon. Take for example the album Unortheta from the Icelandic band Zhrine, where civilization is portrayed as a sterile structure dominating a dying world, an endless struggle in a maze that never leads to the promised paradise – indeed, “utopian torture” (Zhrine Citation2016). Such melancholy is hardly inconceivable for a sustainability scholar whose work is to keep up with the latest reports on global ecological degradation.

Long before today’s ecological crises, profound critiques of modern technological society emerged. Such critique can be called “psychological”, as it primarily argues against the desirability (instead of technical-ecological unfeasibility) of modernity (Carroll Citation2010). One particularly symbolic event is Dostoevsky’s 1862 visit to the Crystal Palace in London, the architecturally marvellous setting built for the first ever Great ExhibitionFootnote3 in 1851. In the novelist’s own words: “[You] feel that something has been achieved here, that here is victory and triumph. And you feel nervous. […] It is all so solemn, triumphant and proud that you are left breathless. […] You feel that a rich and ancient tradition of denial and protest is needed in order not to yield” (Dostoyevsky Citation1985, 45).

Dostoevsky’s example resembles the Spurner archetype outlined above: despite his education and cosmopolitanism, his cultural origins and loyalties lie in the periphery and not in Europe or the West. He is disillusioned and pessimistic about modernity and industrialization, and since the cultural currents he opposes are universally celebrated, his resistance has a necessarily antagonistic tone. Just like Pylkkö (Citation2009, 65) urges today’s Spurner to “find allies” against “European mental colonization”, is it not a similar position to Dostoevsky’s, in his seeking of “traditions of denial”? According to Carroll (Citation2010, 120): “The Crystal Palace is Dostoevsky’s crowning symbol for the barrenness of industrial civilization. Virtually the whole Western world saw light, reason and progress streaming in through its glass walls; he saw but the profile of a dark, satanic prison”. When Dostoevsky, who wished to break out from the Crystal Palace, comments on the “millions of people obediently trooping into this place from all parts of the earth” (Citation1985, 45), the analogy with the fly bottle is evident: do not follow the light, but crawl into the darkness.

Here, the physical and practical surroundings come forth. Different settings foster different expertise: university campuses, laboratories, international conferences and market-oriented research and development produce different knowledge, skill and self-understanding than isolated residency or humus-oriented experimentation. Such a conscious ethos is articulated by Majava (Citation2014): “The Mustarinda Association has been inspired by the cultural tradition of moving away from cities and seeking reflective tranquillity, focus and intensity from silence and strong connection with nature” (395).

Periphery can of course also host ultra-modern expert cultures. But there is also cultural and physical space to foster alternative understandings. In Nordic countries such as Finland, the modern rupture is strong but relatively recent, and so the gap between pre-modern and post-fossil is narrow – it is well possible that a Finnish sustainability expert is only one or two generations away from agrarian livelihood and world-view. So when the artificial light gives way to darkness, the bear can make its uninvited appearance – if merely as a fading cultural imagination (Vadén Citation2006) – while the rational subjectivity, upon which one’s expert identity rests, is muted and fades away (Pylkkö Citation1998, 274). Although such epiphanies (Adams, Jones, and Ellis Citation2015, 47) evade exhaustive explanation, they give a humbling reminder of an expert’s place in nature, making ideas of planetary control seem immensely distant.

Conclusion

We have autoethnographically explored sustainability expertise, particularly when it is uncomfortable with or critical towards technology, either in practice, agency or world-view (see ). By elaborating in particular the archetype of a Spurner – translated from Pylkkö’s nurjailija – we aim to widen the scale of sustainability expertise which is often understood to be limited between the polar ends of science and humanities. Our aim is not to solve possible problems and challenges encountered in the study, such as bridging the age-old gap between two scientific cultures (Snow Citation1959), that persistently affect today’s sustainability discourse. Instead, our purpose is to illuminate and empower grey zone expertise by regarding it as a genuine yet peripheral form of sustainability expertise. Thus we hope to contribute to deeper understanding of the field and self-reflection of sustainability experts.

The themes approached here may often stay silent knowledge in expert cultures, appearing in casual discussions or as unspoken attitudes. It is understandable, since some of the occurring themes may painfully question the expert’s actual status and legitimacy. However, one particularly valuable reflection can be found from the ecological activist and author Stephanie Mills, who edited the book Turning Away from Technology (1997), summarizing two conferences held by scholars and activists concerned by detrimental effects of globalizing modern technology. In her afterword, Mills describes the shared peripheral feeling of the attendees: “this intelligentsia of technology critics does its work around the edges of the official version of reality” (231). Mills notes how some of the attendees took part – alongside traditional village and peasant communities – in local struggles against global development programmes (230). Also, a clearly defensive tone is expressed in many passages: “Cynicism and vested interest and sheer faddishness mostly prompt the mainstream media’s dismissal of persons pointing out the shadow side of technological development” (230) and “A person can indeed become cranky and isolated under such [circumstances]” (232). These notions suggest a certain proximity between ecologically informed neo-luddism (Mills Citation1997) and a peripheral Spurner who might see Luddites (and Luddist practices) as welcome allies, cultural elements that are born from, but are alien to, the core of colonial Europe (Pylkkö Citation2009, 65).

Mills articulates one further central point, namely how such expertise is not compartmentalized in professional pigeonholes: “Unlike the proponents of mass technology and economic globalization, the activists and thinkers mounting this critique don’t stand to profit from their brand of advocacy. These are lifetime civil society folks” (230). These people are “philosophers, journalists, organizers, physicists, anthropologists, psychologists, economists (several of whom refer to themselves as “de-professionalized”), poets, and a couple of farmers. Most operate at the margins: of academe, of nongovernmental organizations, of media, and of the economy” (232). Such grey zone sustainability expertise may amount to a way of life rather than a (mere) career.

What then is the wider significance of these observations? From a very abstract viewpoint, sustainability expertise can be said to produce knowledge and practices for us humans to keep inhabiting the Earth (Latour Citation2018). The appropriate role of technological infrastructures and practices in sustainable transitions is far from a settled question (Heikkurinen and Ruuska Citation2021), and it seems only reasonable to hope for open and constructive discussions around it. Nevertheless, it seems that in paradigmatic academic contexts scholars experience difficulties expressing other than enthusiastic techno-attitudes (Kerschner and Ehlers Citation2016). While such an optimistic default attitude may often be unreflective and thus unintended, it still affects research orientation and results, as well as education, thus institutionally reproducing these attitudes in new generations of experts (Kerschner and Ehlers Citation2016, 148). Kerschner and Ehlers (Citation2016) argue that experts’ reflective awareness of their techno-attitudes is not only a professional virtue, but also a public responsibility: “There should not be positions or options that are systematically discriminated or closed down, as it may be the case with non-adoption of new technologies or a reversal to low-technology options. Hegemonic discourses on technology may still be at work and influence decision-making” (149). These observations hint at the fact that there may be an acute epistemic blind spot in cultures of sustainability expertise, namely the sustainability expertise’s relation to technology. As the multidimensional polycrisis emerges, sustainability expertise cannot afford to be blinded by excessive technological optimism. When the light is too bright, some darkness is needed in order to see: the darkness that is common to the post-professional ethos (Illich Citation1977), the technology criticism of Luddites and the anti-colonial sentiment of spurners.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and the special issue editor Johanna Hohenthal for their encouraging and insightful comments during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Also more generally we question the possibility of non-use of culturally prevailing technologies to express genuinely “non-confrontational” (Puech Citation2017) or “free” relation to technology, as suggested, e.g. in some interpretations of the Heideggerian idea of Gelassenheit (Dreyfus Citation1997). Based on our personal experience, regardless of non-confrontative intentions, such non-use is repeatedly challenged and questioned in everyday life and professional practice – the dominant culture “demanding explanation” – thus almost inevitably resulting in antagonism.

2 Not meaning following of Humean philosophy, as sometimes uttered, but humus-oriented (post-)humanism.

3 The full name of the event “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations”, underlines the emphasis on latest achievements in technology and science.

References

- Adams, Tony E., Stacy Holman Jones, and Carolyn Ellis. 2015. Autoethnography. Understanding Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Beck, Ulrich. 1994. “The Reinvention of Politics: Towards a Theory of Reflexive Modernization.” In Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, edited by Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, and Scott Lash, 1–55. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Beck, Ulrich. 2009. World at Risk. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bonnedahl, Karl Johan, Pasi Heikkurinen, and Jouni Paavola. 2022. “Strongly Sustainable Development Goals: Overcoming Distances Constraining Responsible Action.” Environmental Science & Policy 129: 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.01.004.

- Borgmann, Albert. 1984. Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Breault, Rick A. 2016. “Emerging Issues in Duoethnography.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 29 (6): 777–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1162866.

- Carroll, John. 2010. Break-out from the Crystal Palace: The Anarcho-Psychological Critique: Stirner, Nietzsche, Dostoevsky. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. 1985. Winter Notes on Summer Impressions. London: Quartet Books.

- Dreyfus, Hubert L. 1997. “Heidegger on Gaining a Free Relation to Technology.” In Technology and Values, edited by Kristin Shrader-Frechette, and Laura Westra, 41–55. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dreyfus, Hubert L. 2014. Skillful Coping: Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elhacham, Emily, Liad Ben-Uri, Jonathan Grozovski, Yinon M. Bar-On, and Ron Milo. 2020. “Global Human-Made Mass Exceeds all Living Biomass.” Nature 588 (7838): 442–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5.

- Ellul, Jacques. 1964. The Technological Society. New York: Vintage Books.

- Eräsaari, Risto. 2009. “Open-context Expertise.” In Governmentality Studies in Education, edited by Michael Peters, A. C. Besley, Mark Olssen, Susane Maurer, and Susanne Weber, 55–76. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Goldsmith, Edward. 1992. The Way: An Ecological World-View. London: Rider.

- Graeber, David. 2007. “Revolution in Reverse: Or, On the Struggle Between Political Ontologies of Violence and Political Ontologies of the Imagination.” Radical Anthropology 1: 4–14.

- Haberl, Helmut, Dominik Wiedenhofer, Doris Virág, Gerald Kalt, Barbara Plank, Paul Brockway, Tomer Fishman, et al. 2020. “A Systematic Review of the Evidence on Decoupling of GDP, Resource Use and GHG Emissions, Part II: Synthesizing the Insights.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (6): 065003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi. 2012. “Matka konferenssiin ja takaisin: Lentämisen moraalinen ongelma akateemisessa työssä.” [Travelling to Conference and Back: the Moral Problem of Flight Travel in Academic Work.] In Tutkijat keskustelevat-esseitä ja kirjeitä akateemisesta työstä, edited by Keijo Räsänen, 80–92. Helsinki: Unigraphia.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi. 2017. “The Relevance of von Wright’s Humanism to Contemporary Ecological Thought.” Acta Philosophica Fennica 93: 449–463.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi. 2018. “Degrowth by Means of Technology? A Treatise for an Ethos of Releasement.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1654–1665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.070.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi. 2021. “Atechnological Experience Unfolding.” In Sustainability Beyond Technology: Philosophy, Critique, and Implications for Human Organization, edited by Pasi Heikkurinen, and Toni Ruuska, 96–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi, and Toni Ruuska, eds. 2021. Sustainability Beyond Technology: Philosophy, Critique, and Implications for Human Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Henig, David, and Daniel M. Knight. 2023. “Polycrisis: Prompts for an Emerging Worldview.” Anthropology Today 39 (2): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12793.

- Hickel, Jason, and Giorgos Kallis. 2020. “Is Green Growth Possible?” New Political Economy 25 (4): 469–486. https://doi-org.libproxy.tuni.fi/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

- Houtbeckers, Eeva, and Tiina Taipale. 2017. “Conceptualizing Worker Agency for the Challenges of the Anthropocene: Examples from Recycling Work in the Global North.” In Sustainability and Peaceful Coexistence for the Anthropocene, edited by Pasi Heikkurinen, 140–161. New York: Routledge.

- Illich, Ivan. 1973. Tools for Conviviality. New York: Harper & Row.

- Illich, Ivan. 1977. “Disabling Professions.” In Disabling Professions, edited by Ivan Illich, Irving Zola, John McKnight, Jonathan Caplan, and Harley Shaiken, 11–39. London: Marion Boyars.

- Kerschner, Christian, and Melf-Hinrich Ehlers. 2016. “A Framework of Attitudes Towards Technology in Theory and Practice.” Ecological Economics 126: 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.010.

- Kingsnorth, Paul, and Dougald Hine. 2014. Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto. Dark Mountain Project. https://dark-mountain.net/about/manifesto/.

- Korpela, Saara, and Antti Majava. 2020. “Earth, Wind, But Not Much Fire – the Low-emission Energy System of Mustarinda House” Mustarinda. https://mustarinda.fi/blog/mustarinda-energy-system.

- Lachney, Michael, and Taylor Dotson. 2018. “Epistemological Luddism: Reinvigorating a Concept for Action in 21st Century Sociotechnical Struggles.” Social Epistemology 32 (4): 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2018.1476603.

- Latour, Bruno. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity.

- Lawrence, Michael, Scott Janzwood, and Thomas Homer-Dixon. 2022. What is a Global Polycrisis? And How is it Different from a Systemic Risk?. Version 2.0. Cascade Institute, Discussion Paper. https://cascadeinstitute.org/technical-paper/what-is-a-global-polycrisis/.

- Lucero, Anrés. 2018. “Living Without a Mobile Phone: An Autoethnography.” Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1145/3196709.3196731.

- Majava, Antti. 2014. “Kohti pimeyttä.” In Ympäristömytologia, edited by Seppo Knuuttila, and Ulla Piela, 393–405. Helsinki: SKS.

- Meadows, Donella H., Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. 1972. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

- Merchant, Carolyn. 2015. Autonomous Nature: Problems of Prediction and Control from Ancient Times to the Scientific Revolution. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mills, Stephanie, ed. 1997. Turning Away from Technology: A New Vision for the 21st Century. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

- Mitcham, Carl. 1994. Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mol, Arthur P, and Gert Spaargaren. 2000. “Ecological Modernisation Theory in Debate: A Review.” Environmental Politics 9 (1): 17–49. https://doi-org.libproxy.tuni.fi/10.1080/09644010008414511

- Nichols, William. 1976. “Skeptics and Believers: The Science-Humanities Debate.” The American Scholar 45: 377–386.

- Noble, David F. 1979. America by Design: Science, Technology, and the Rise of Corporate Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Philosophers for Sustainability. n.d. “About Us.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.philosophersforsustainability.com/about-us/.

- Piattoeva, Nelli, and Antti Saari. 2022. “Rubbing Against Data Infrastructure (s): Methodological Explorations on Working with (in) the Impossibility of Exteriority.” Journal of Education Policy 37 (2): 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1753814.

- Puech, Michel. 2017. “A Non-Confrontational Art of Living in the Technosphere and Infosphere.” Foundations of Science 22: 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-015-9452-9.

- Pylkkö, Pauli. 1998. The Aconceptual Mind: Heideggerian Themes in Holistic Naturalism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Pylkkö, Pauli. 2009. Luopumisen dialektiikka. Taivassalo: Uuni.

- Pylkkö, Pauli. 2012. Fysiikkaviikari filosofian ihmemaassa – eli olisiko tiedeuskovaisuutta hoidettava lääkkeillä ja kirurgialla? Uuni. http://www.uunikustannus.fi/fysiikkaviikari.pdf.

- Saikkonen, Sampsa, and Esa Väliverronen. 2022. “The Trickle-Down of Political and Economic Control: On the Organizational Suppression of Environmental Scientists in Government Science.” Social Studies of Science 52 (4): 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221093397.

- Salminen, Antti, and Tere Vadén. 2015. Energy Experience: An Essay in Nafthology. Chicago: MCM Publishing.

- Salminen, Antti, and Tere Vadén. 2018. Elo ja anergia. Tampere: niin&näin.

- Skrbina, David. 2014. The Metaphysics of Technology. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Snow, Charles Percy. 1959. Two Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stirling, Andy. 2010. “Keep it Complex.” Nature 468 (7327): 1029–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a.

- Stirling, Andy. 2023. “Taking Sustainability Transformations Seriously.” Keynote given at the Sustainability Science Days 2023, Helsinki, Finland, May 2023.

- Takkinen, Pasi, and Pasi Heikkurinen. 2022. “Harmaalla alueella: Autoetnografia kestävyysasiantuntijuuden teknologiasuhteesta.” [In the Grey Zone: An Autoethnography of the Human-technology Relations in Sustainability Expertise.] niin&näin 4/2022: 15–26.

- Takkinen, Pasi, Jani Pulkki, and Tere Vadén. 2023. “From the Archimedean Point to Circles in the Sand – Post-Sustainable Curriculum and the Critical Subject.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, Online first, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2023.2274275.

- Thierry, Aaron, Laura Horn, Pauline von Hellermann, and Charlie J. Gardner. 2023. “‘No Research on a Dead Planet’: Preserving the Socio-Ecological Conditions for Academia.” Frontiers in Education 8: 1237076. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1237076.

- Turner, Graham M. 2008. “A Comparison of The Limits to Growth with 30 Years of Reality.” Global Environmental Change 18 (3): 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.05.001.

- Vadén, Tere. 2006. Karhun nimi [The Name of the Bear]. Tampere: niin&näin.

- Vadén, Tere, Ville Lähde, Antti Majava, Paavo Järvensivu, Tero Toivanen, Emma Hakala, and Jussi T. Eronen. 2020. “Decoupling for Ecological Sustainability: A Categorisation and Review of Research Literature.” Environmental Science & Policy 112: 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.016.

- von Wright, G. H. (1976) 1977. What is Humanism? The Lindley Lecture, delivered at the University of Kansas, 19 October 1976. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/12393.

- von Wright, G. H. (1978) 1981. Humanismi elämänasenteena (translated by K. Kaila). Keuruu: Otava.

- Wallgren, Thomas, and Niklas Toivakainen. 2021. “The Question of Technology: From Noise to Reflection.” In Sustainability Beyond Technology: Philosophy, Critique, and Implications for Human Organization, edited by Pasi Heikkurinen, and Toni Ruuska, 29–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Watson, Jamie Carlin. 2021. History and Philosophy of Expertise – The Nature and Limits of Authority. London: Bloomsbury.

- Wilson, Scott, ed. 2014. Melancology: Black Metal Theory and Ecology. Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

- Winner, Langdon. 1978. Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-Control as a Theme in Political Thought. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. London: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Zhrine. 2016. “Empire.” Track 5 on Unortheta. Season of Mist.