Abstract

In this paper we offer an empirically rich, longitudinal account of the role and influence of externally sourced experts by the Swedish development aid agency, Sida, from the 1960s until present times. We describe what type of expertise has been required from external experts and how the content and rituals of these contracted experts have contributed – or not – to perceptions of trust and certainty. In the paper we present three eras, all with their distinctive features on the normative rationale and forms for external expertise; 1. 1960s–ca 1995: the Quick-fix implementer era; 2. Ca 1995–ca 2005: the Collaborative turn era; and 3. Ca 2005–2020s: the Proper organization proxy era. We suggest that a mission drift has occurred in Swedish aid as concerns both the in-house expert role of aid bureaucrats and the role of procured experts. The paper concludes that all throughout, external experts have served an important function – that of making organizations in the donor role less uncertain of their decisions on which organizations should receive funding. Interestingly, however, the use of external experts has in all times given rise to additional uncertainty, which, in turn, has called for even more experts. We also find that external experts have repeatedly been criticized for ineffectiveness and consultocracy, meaning that consultants have been influential in the formulation and implementation of policies aimed at restructuring public services.

Introduction: external experts as co-creators

Many times, I have come in after other consultants who have worked on the same assignment, but who have promoted a completely different message.

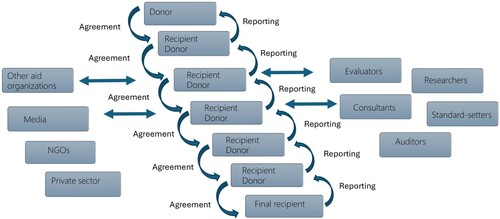

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the dynamic aid web, with examples of its vertical and horizontal relations

Aid bureaucrats face three interlinked expectations: (1) to do for the poor what is morally right, (2) to provide aid that is effective, and (3) to provide aid within the budget enabled by the public taxpayer. This is indeed a complex mission in its own right and one that takes place in a highly complex system characterized by multiple interacting actors, fluid boundaries; and unpredictable dynamics (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024; Rutter et al., Citation2020). As seen in the schematic , there are numerous horizontal relations in the field of development aid, among whom we here focus mainly on external experts such as consultants and evaluators, although we also include some data on other types of external experts such as auditors, researchers and standard-setters such as OECD-DAC.

The complex mission and organizational conditions of the development aid organizations, in turn, bring about a number of uncertainties. Uncertainty can, generally speaking, be defined as a situation where there is no ‘single and complete understanding of the system to be managed’ (Raadgever et al., Citation2011). It may, for example, be difficult to predict and understand how components of the complex environment are changing, what the future effects will be, which responses are available and which should be chosen (Milliken, Citation1987; Sicotte and Bourgault, Citation2008). Summing up this far, the field of international development aid can be categorized as an extreme case in the sense that its typically very dedicated aid bureaucrats find themselves faced with highly complex conditions from which uncertainties arise that they must somehow respond to.

Current research confirms that two ‘management dreams’ have been particularly influential among aid bureaucrats: (1) the dream of simplifying the complex, and (2) the dream of controlling the future (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024, see also Eyben, Citation2010; Eyben et al., Citation2016; Shutt, Citation2016; Vähämäki, Citation2017). For our purposes here, it is vital to note that the gap between these simplified, rational management dreams and the often messy, uncertain practices of development aid projects, stirs demand for external professional services.

As described and analysed in more detail in the upcoming historical account, over the years, external experts have been contracted by Sida and its partners for a number of reasons (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024).Footnote1 Experts have been hired to support aid bureaucrats in the donor role in assessing who should receive aid funds, but also to support aid bureaucrats in the recipient role in accessing funds or helping to implement projects (Curtis, Citation2004). Different types of knowledge have been in demand and external experts have not only been consulted for their knowledge, but also for their moral support to individual decision-makers and as agents of legitimation. In this sense, external experts may clearly be defined as co-creators of aid operations.

A general take-away from the social phenomena of complexity, uncertainty, and uncertainty responses is that complexity tends to give rise to uncertainty (Howell et al., Citation2010) and uncertainty in turn then tends to call for some kind of uncertainty response. Often, uncertainty responses are thought of as part of a rational decision-making process where the uncertainty response is assumed to lead to uncertainty reduction. However, our core argument in this article is that an uncertainty response can also lead to additional uncertainties, rather than to the expected uncertainty reduction. In essence, external experts have often been called on to reduce uncertainties of different kinds. But an important unsettled question is whether the use of consultants has indeed managed to do so, or whether this is rather a ‘black-box’ assumption too seldom unpacked empirically?

Following this brief introduction, we now first present some previous research on uncertainty and the use of external experts with an emphasis on management consultants in the public sector. After having presented our methods and empirical material we then embark on the historic exposé on how external experts have been viewed and used by the Swedish aid agency Sida since the 1960s.

Calling on external experts to tackle uncertainty

Some fields and operations are more complex and uncertain than others. These fields can often also be described as contested fields. As suggested by Bacchi (Citation2009), in such fields, key problems, including the wicked ones, are continuously being represented in this way or the other. Looking back historically at the value-laden discourse of contested fields, we note that although many have sustained their status as contested for decades, if not centuries, the contestation itself has been represented in different ways at different periods of time (Alexius et al., Citation2014). As demonstrated by research on values and value conflicts (Alexius et al., Citation2014; Fourcade and Healy, Citation2007), contestation is seldom ‘essential’ or objectively given. Rather, it is an outcome of negotiations and power struggles amongst a wide range of interests and organizations over extensive periods of time (Alexius, Citation2014; Alexius and Grossi, Citation2017). And although there may be no simple solutions fit for the wicked problems at hand, the influential ‘mechanisms of hope’ in our modern society (Brunsson, Citation2006) imply that reform becomes a never-ending routine, especially in contested fields (Brunsson, Citation2009).

Considering the contested status of their field and the wicked nature of the key problems tackled by aid organizations, it is understandable that aid bureaucrats need to collaborate, not only with one another, but also with several different external partners (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024; Kipping, Citation2002). Pekka Seppälä from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Finland brings up the dependency on external consultants in his observation of the development aid bureaucrats’ role:

The bureaucrat has only a limited role in actually addressing the problem. The role of the development bureaucrat is limited to defining the terms of reference [ToR, i.e. a job description] for a team of consultants who are actually tasked to look at the problem in more detail. […] A single bureaucrat is powerless if she is unable to command consultants and colleagues to follow the level of detail.

Recent literature on ‘consultocracy’ (Kirkpatrick et al., Citation2019; Ylönen and Kuusela, Citation2019) argues that external experts have become increasingly influential in the formulation and implementation of policies aimed at restructuring public services (Lapsley and Oldfield, Citation2001; Saint-Martin, Citation1998), typically according to the ethos of commercial professionalism (Furusten, Citation2013). A common argument in this more critical literature is that external experts have moved closer and in fact, too close to public-sector decision-making fora, and that as a result, these experts have come to challenge conventional forms of decision-making within the public sector. This development has had several implications, for example a decreased level of in-house knowledge and competence in public-sector organizations (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2020). It has also been reported that consultants have increasingly replaced civil servants, and even politicians, in terms of both knowledge and organizational memory and control, which has given consultants increased power in politics, public governance, and public-sector practices (Grafström et al., Citation2021; Rothstein et al., Citation2015; Ylönen and Kuusela, Citation2019).

Critical research on consultocracy has warned that external experts are being used not merely for planning and implementing of political reforms, but increasingly also for support at the heart of decision-making processes – albeit often in more informal ways which make the experts’ involvement less transparent and harder to evaluate from the outside (Alvesson and Robertson, Citation2006; Garsten et al., Citation2015; Kirkpatrick et al., Citation2019). Thus, external experts are not only trusted and praised, they are also increasingly criticized. In this paper, our historic exposé reveals that, over the years, external experts in the field of development aid have been repeatedly criticized for bringing about confusion, mistrust, and additional uncertainty, rather than clarity, trust and certainty, as typically expected and most often intended.

Research design, methods and material

A study on the responses to political demands and uncertainty in a contested field is well suited to an historical account where comparisons can be made over time. The focus of our study has been to follow the shifting views on and uses of external expertise in development aid operations from the 1960s onwards. Previous historical studies have concluded that Swedish aid can better be described by continuity than change (Berg et al., Citation2021; Odén, Citation2013; Pettersson, Citation2022; Stokke, Citation2019). Yet, although no major policy paradigm shifts have been seen on the macro level (until very recently at least), political pressure and reform attempts have certainly been seen on the meso level of aid operations. As an example, studying how the Swedish aid agency Sida has responded to political ambition to demonstrate results and effectiveness of aid over the years, Vähämäki (Citation2017) identified four time periods when an extra effort was made by Sida to systemize results. Thus, we conclude that while Swedish aid has often been characterized as a generally stable policy field, there have been certain ‘transformative moments’ of reform on the organizational level of operations.

In Rothstein’s words (Citation1992, pp. 17–18), transformative moments are periods marked by attempts ‘not only to play the political game, but also to change the rules of the game’. Such transformative moments can be seen on different levels of societal and organizational analysis and are best determined post hoc, since not all events that are defined as critical ad hoc prove equally influential after the fact. Determining what is a transformative moment and not, even post hoc, is a matter of judgment. And between each identified transformative moment are longer periods of relative stability, which we here call eras (see also Alexius et al., Citation2014). Aware of the complex sources and paths of institutional and organizational change (Djelic and Quack, Citation2007), we have sought to identify a post hoc historical pattern of shifting views on and use of external expertise. Our primary focus has been the meso level of interorganizational relations, narrowing the scope to Sida’s role as a buyer of external expertise, including the micro level of its aid funding decisions.

For the purposes of this paper we have conducted a longitudinal study, choosing a key actor as a focal point of analysis (such as Sida in our case) is often both research-economically wise and pedagogical, since not all can be described to similar detail in a complex historical development. Although we offer no country comparison in this paper, we have reason to believe that the here described Swedish development shares common features with that of other OECD countries. This since the policy discourse for development aid is international and aid donors often share similar reform agendas.

We have derived our empirical material from a mix of sources, secondary historical accounts from both the international aid context and Swedish historical accounts as well as own data. We draw extensively on documents (archived project applications, decision statements, correspondence, memos, etc.) but have also consulted our broad base of around 80 own interviews, including retrospective interviews with aid bureaucrats and experts, gathered in current and previous research on the more recent history of Swedish aid (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024; Vähämäki, Citation2017). We have interviewed the consultancy companies holding so-called framework agreements on Results-Based Management with Sida, these are Niras (formerly InDevelop) and AIMS. We have also interviewed five of the help-desk functions, both in individual interviews and focus-groups interviews. Interviews have also been held with individual consultants who have worked for SIDA/Sida since the 1960s. Around 20 such external experts have been interviewed.

In gathering the data, we used a combination of methodological techniques (Schatzman and Strauss, Citation1973), aiming for a thick description (Geertz, Citation1973) of the typical pattern of each era, rather than a deeper analysis of the triggers to the transformative moments per se. The main methods used to analyse the empirical material has been content analysis and process tracing (Alvesson and Sköldberg, Citation1994; Collier, Citation2011), in attempts to map the chronological development of the characteristic views and behaviour of each era (focusing on how Sida has interacted with external experts over the years).

Taking advantage of access to retrospective data that spans longer time periods (and offers the possibility of within-case analyses and comparisons instead of between-case comparisons and analysis), we aimed for a relevant periodization. Due to the gradual nature of organizational change and the slow sedimentation of previous reform ideas as new are introduced, it is important to point out that the borders of the identified eras are actually more ‘fuzzy around the edges’ in practice than the concept of ‘transformative moment’ and the standard representation of a neat article table allows for. But to the best of our knowledge and available data, we have come to the conclusion that at about these moments in time (ca 1990, ca 2005), a new dominant scheme on the view and use of external expertise did indeed take hold, and as a result the interactions did transform as new ‘rules of the game’ became the norm. However, rather than sudden shifts, our exploratory retrospect case analysis approach has enabled us to identify gradual change in the perception of contestation and uncertainties at field level which in turn have called for and influenced new ways of contracting and co-creating with external experts at the interorganizational level (Runco and Albert, Citation2010).

The longitudinal case account of Sida’s use of external expertise

Below, we present our empirical account divided into the three identified eras: 1. 1960s–ca 1995: the Quick-fix implementer era; 2. Ca 1995–ca 2005: the Collaborative turn era; and 3. Ca 2005–2020s: the Proper organization proxy era.

1960s to ca 1995: the quick-fix implementer era

When SIDA – the Swedish International Development AuthorityFootnote2 – was founded in 1965, it soon came to be seen as Sweden’s main expert organization in international development aid. At that time, the agency’s staff was largely comprised of specialized thematic experts in charge of delivering aid funds to development projects. It is clear from historical documentation from the time that urgency to combat poverty in the world was a key concern to be tackled by aid organizations and the hopeful but rather naive ideal of the day was what we call ‘quick-fix’ implementation. For example, Ernst Michanek, SIDA’s first director-general, stated that the agency had ‘ten years to steer development in a new direction’ (Michanek, Citation1964). At least initially, there was a consensus and optimism among actors involved in aid about the task of achieving the goals of development aid – ‘to raise the living standards of poor people’ (Gov, Citation1962, p. 100), which was perceived as possible, by means of development aid (Berg et al., Citation2021).

At this time, two main types of external experts were contracted by SIDA to quickly ‘solve’ the urgent problem of poverty. The first was external capacity experts that were contracted to support SIDA in its own expert role. The argument for contracting these experts was capacity constraints, i.e. that SIDA itself did not have enough staff with the right competencies to undertake certain tasks (such as administration, recruitment, documentation, thematic overviews, and project control), or that external expertise was needed to serve as individual advisors to SIDA staff (RRV, Citation1983). A division of the world had been made into ‘developed’ nations (i.e. prosperous, scientifically and technologically leading) and ‘underdeveloped’ nations (i.e. deficient, unprogressive) that faced conditions of misery, where the latter were depicted as unable to end the suffering of their people without the knowledge and skills of the former.

The second type of external experts hired at this time were called on to help out with the implementation of aid projects in recipient countries. This type, which soon grew to a large cadre of experts, was most often described as ‘technical assistance’ employed in ‘people-oriented programs designed to transfer knowledge through education, training, and research’ (Loomis, Citation1968, p. 1330). Their focus was on changing the behaviour of individuals and institutions in ‘developing’ countries (Loomis, Citation1968, p. 1330). Due to the urgency at hand to solve the problem of poverty in the world, technical assistance was often contracted in a speedy manner, by handpicking experts and without procurement processes (RRV, Citation1983).

Competencies identified as critical at the time were those of teachers, vocational instructors, adult learning educators,Footnote3 and family planners, but also engineers. In addition, it was typically assumed by Swedish politicians and aid bureaucrats that these experts ought to be Swedes, and that it would be most efficient for aid if the experts were hired by SIDA (RRV, Citation1983). As a result of this powerful framing of the problem and the needs, in the decades that followed, large education and training programmes were established in Sweden aiming to create a Swedish resource base, to undertake various tasks in development aid (Ewald and Wohlgemuth, Citation2022).

It was not long however, before public aid and the use of external experts for technical assistance began to draw criticism. Criticism was raised towards the short-sightedness when contracting external experts. The Swedish National Audit Office/Riksrevisionsverket (RRV) argued in its 1983 audit that there was short-sightedness both in the selection process of consultants, with no databases of information on the actual competencies of the external experts. Moreover, the contracts were often short and did not take into account that problems at hand may have to be tackled during a longer term. Criticism was also raised towards the power gained by the external experts over development politics and project implementation. RRV argued that project documentation and assessments were sometimes produced entirely by external experts, with no involvement of internal SIDA staff. According to the audit, external experts could often ‘form the projects to suit their own companies’ (RRV, Citation1983, p. 26). Tendencies towards ‘consultocracy’ (Ylönen and Kuusela, Citation2019) were thus identified as a risk very early on in this contested field.

Aid projects were also increasingly described as ‘failures’, and there was a realization that the task at hand was not as simple as initially envisioned. In fact, great uncertainties arose concerning the effects of aid. In both international articles (Jolly, Citation1989; Loomis, Citation1968) and formal national evaluations (Forss et al., Citation1988; RRV, Citation1983), criticism was raised regarding the fundamental set-up of technical assistance where experts from the global north (in this case Sweden) were contracted by aid organizations in the donor role with the intention to support the process of modernization in poor, recipient countries. Loomis (Citation1968), for example, argued that the very presence of technical assistance implied a continuation of inadequacy and inferiority on the part of the recipient, which in turn led to resentment, and in the end implied a reduced or nullified effect of the aid received. On the same topic, a Nordic evaluation of the technical assistance went as far as to argue that ‘many aid projects have a negative impact on institutional development’ suggesting that the fact that projects often ended up being run by the technical assistance people, created oversized unsustainable organizations that were dependent on aid funding (Forss et al., Citation1988, p. ii).

Criticism was also raised towards the competencies of the technical assistance. RRV for example argued that external experts had too ‘narrow’ an understanding of the development problems, which posed the risk of making problems in developing countries worse (RRV, Citation1983). Similarly, the Nordic evaluation argued that the expected knowledge transfer from North to South had been ‘non-existent or crippled,’ and questioned whether there had actually been a need for foreign personnel (Forss et al., Citation1988, p. 1). The hopes of finding a simple ‘quick-fix’ solution (knowledge transfer through technical assistance) to the complicated problem of world poverty had thus proven to be riddled with uncertainties. And although the quick-fix framing was an ideological misconception, blame was increasingly placed on external experts for their ‘failure’ to deliver a simple, quickly implemented solution.

Somewhat paradoxically, however, the uncertainties and failures that had come to light concerning the use of external experts soon increased the demand for a third kind of external expertise: evaluators. Guidelines for evaluation of international development assistance had been developed as early as 1959 by UNESCO and a few years later by USAID (Citation1965), both emphasizing the importance of systematic, evidence-based evaluations which would determine ‘results’ and effects of aid. However, it was not until the 1980s, two decades after the initiation of public development aid, that the field experienced an ‘explosion of interest’ in aid evaluation (Lancaster, Citation2008). The American Evaluation Association (AEA) founded in 1986 played a significant role in advancing evaluation as a profession by providing resources, training, and a community for evaluation professionals. As a response to this development, large organizations in the donor role set up evaluation units and the OECD established the DAC Expert Group on Aid Evaluation who developed specific evaluation standards for aid evaluations (Cracknell, Citation1988). Both AEA and the DAC Expert Group on Aid Evaluation are examples of standard-setters and who over the years have had major influence on aid operations.

The interest in evaluations also spurred a development of methods for attempting to determine when aid contributed to an effect. For this purpose, the USAID evaluation manual from 1965 had suggested the Logical Framework Approach (LFA), a matrix, which allowed users to map out how resources and activities will contribute to achieving objectives and results using quantifiable indicators to measure progress (Binnedjikt, Citation2001; Coleman, Citation1987; Vähämäki et al., Citation2011). The LFA was highly supported as a tool to be used by evaluators of aid projects. However, a common criticism from the evaluations was the lack of proper planning. If intended results had not been defined, it became difficult for evaluators to tell whether projects had been successful (Vähämäki, Citation2017). Both in 1971 and in 1981, SIDA launched larger initiatives to improve results-based thinking in the organization. The initiatives were launched due to a criticism from auditors and the media about the need for SIDA to be more results-oriented in its aid programming. The development of both initiatives was supported by external management consultants who adopted the thinking behind the LFA, which in turn kept up the demand for external expertise in project management (Vähämäki, Citation2017).

In sum, the main contestation during this period concerned whether or not a technical quick fix orchestrated from the Global North could solve the problem of eradicating poverty in the world. Two types of external expertise – capacity support and technical assistance – were used in hopeful attempts to respond to the growing uncertainties. However, the contracting of these external experts brought about criticism of not following proper procurement rules. At this time, one-person companies were typically procured directly, with neither a bidding process nor evaluation criteria. SIDA was recommended by the RRV to reorganize its procurement processes and to ensure that the consultants hired actually possessed knowledge and skills ‘with broader perspectives’ – as opposed to the existing, criticized ‘narrow’ perspective on development assistance (RRV, Citation1983). RRV’s recommended that SIDA increase its own internal competency by procuring what was referred to as long-term ‘close consultants’ (‘närkonsulter’) to assist in ‘complicated cases of expertise procurement’ and other specialist tasks (RRV, Citation1983, p. 6). In fact, this recommendation was a bit ambivalent considering the consultocracy critique in the same RRV-report. The general view was however that, as long as external experts were procured correctly, the close working relationship between external experts and SIDA decision-makers was a good thing for the aid processes.

Ca 1995–ca 2005: the collaborative turn era

From the mid-1980s, the hopeful ideas of a quick-fix solution to poverty were gradually abandoned for the more realistic understanding that combatting poverty in the world was a much more complicated and long-term undertaking than originally thought. As summarized by Andersson et al in an edited volume:

All failed aid efforts and the disastrous economic development in many of the Swedish recipient countries have led to a realization that providing good aid implies something much more difficult than a mere transfer of resources from rich to poor countries. The donor is clearly responsible for making sure that resource transfers lead to results. (Andersson et al., Citation1984)

During the forthcoming two decades into the second era which we here call the ‘Collaborative turn era’, the new increased mandate, and all learnings from failures in the previous era, clearly affected the views on and various ways in which external experts were involved in aid. Aid organizations now increasingly sought to influence developing countries’ macro-economic policies and to support the building of strong local institutions. At the same time, locally led bottom-up and participatory approaches were favoured. Aid projects got more abstract goals such as those of ‘increased equity and social transformation’ or ‘increased capacity-building’ which were even more difficult to verify objectively (Hintjens, Citation1999). In addition, the constitution of expert identities had become more complex, since experts of participatory programmes now had to downplay or even conceal their own expertise, agency and practical role in programme delivery, to match the new authorized view of experts as ‘facilitators’ or ‘catalysts’ of community action and local knowledge (Mosse, Citation2007). Summing up, at least post hoc, this comes across as an extremely ambitious time when a lot of different, sometimes contradictory initiatives were tried out in Sida’s horizontal relations.

Just as in the first era, external experts were still used in project implementation in developing countries. But while they were still called ‘technical assistance’, competence requirements had shifted from classic professionals such as teachers, family planners and engineers, to economist advisors who were to support aid organizations in their attempts to influence developing countries’ macro-economic policies and in the building of strong local institutions.

In contrast to the idea that development problems could be fixed quickly, there was now optimism that proper planning and organizing knowledge needs would help solve overall development problems. The same year as the launch of the new Sida (Citation1996), the agency officially adopted the Logical Framework Analysis (LFA) as a method to be applied in contribution management (Sida, Citation1996). At Sida, the LFA approach was coordinated by a new official Sida-post, the internal ‘LFA advisor’. And as its support, Sida contributed with financing for about 20 external consultants who become ‘certified LFA consultants’ contracted to conduct LFA-trainings for all Sida staff members (Vähämäki, Citation2017). Subsequently, it became a normal routine in project management to consult LFA consultants in project management at micro level. The contracting of LFA-consultants could be seen as a response to the previous critique of a lacking competence on planning and follow-up routines of aid projects which the critics claimed should to be more formalized (see RRV, Citation1983).

In addition to the certified LFA-consultants, and following the advice of the RRV, Sida had created a system of ‘close consultants’. A typical set up for each thematic unit and division at Sida was to have a group of external consultants supporting its operations. The rationale for having the consultants so closely tied to Sida operations was that competence was best developed if the consultants worked in teams together with Sida staff. In line with this argument, Sida also made attempts at creating a Swedish ‘resource base’, defined as consisting of Swedish academia, external experts, the private sector, and civil society. It was now seen as important to build up competence in development among a wider set of actors, although still Swedish actors (Ewald and Wohlgemuth, Citation2022). Closeness, informal relations, and continuous interaction with actors in society were seen as important for competence development and, in the longer perspective, Sweden’s ability to face uncertainties within the field of development aid.

However, the use of external experts in aid was once again criticized for increasing the inequality between organizations in the donor role and organizations in the recipient role. William Easterly, a former World Bank economist and later professor at New York University, for example, published a book provocatively titled The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor, in which he criticized aid agencies for perpetuating the ‘technocratic illusion’ that external expertise would solve the problems of the developing world. According to him, the advice of external experts had helped to oppress people rather than to free them from poverty (Easterly, Citation2014). Hence, uncertainty about whether aid led to effects was once again raised.

In a critical report from the international NGO Action Aid, it was argued that external experts absorbed USD 19 billions of aid in 2004, a quarter of global aid flows. Action Aid argued that this assistance was ‘phantom aid’ imposed by donors as a ‘soft lever to police and direct the policy agendas of developing country governments.’ The report further argued that it was an open secret that ‘much of the current spending is ineffective, over-priced, donor-driven and based on a failed development model’ (Greenhill, Citation2006, p. 4). In a similar vein Koch and Weingart (Citation2016) penned an exposé of various studies on external experts in aid, arguing that most studies had found that, in the context of aid, external experts largely fail to achieve the objective of increasing the capacity of organizations in the recipient role to an extent that would render them independent from outside assistance. As a result, Koch and Weingart (Citation2016) argued, recipient governments run the risk of ending up in a perpetual cycle of being advised by external experts who potentially (and illegitimately) gain significant influence in the policy space (ibid.). Thus, once again, the critique of consultocracy and of external experts contributing to increased (rather than reduced) uncertainty was aired. A global discussion also arose regarding the need to move away from experts being procured and hired by organizations in the donor role to being procured by the aid recipients and thus to a larger extent be supporting programmes owned and operated by developing countries (Williams et al., Citation2003).

As a response to the criticism of both consultocracy and the ineffectiveness of aid, two attempts to ‘organize independency’ were made during this second era. It was claimed that evaluations should be conducted not by the actors participating in implementation, but by a separate body outside Sida (Ds, Citation1990, p. 63; RRV, Citation1993; SOU, Citation1990, p. 17; SOU, Citation1993, p. 1). As a consequence, two attempts were made to set up such independent bodies: SASDA – the Secretariat for Analysis of Swedish Development Assistance, launched in 1992 (Gov, Citation1992, p. 59) and shuttered in 1993; and the slightly longer-running EGDI – the Expert Group on Development Issues, launched in 1998 and discontinued in 2007.

During this second era, in 1998, Sida also made another attempt to tackle the problem of demonstrating results by initiating yet another results-initiative, the ‘Sida Rating Initiative’ which implied systematizing rating information from projects (i.e. a subjective evaluation of how well the projects performed). However, when implementing the initiative, it was realized that since the Logical Framework had not been used by staff members during the assessment phase, it was very difficult to rate the projects. Thus, despite efforts to support planning by specific LFA consultants, many projects were still not using the technology. And just as the EGDI and SASDA, the Sida internal Rating initiative ended in 2007. All three attempts had been quests to overcome uncertainties of whether aid led to effects by improving the analysis of ‘results’, and all ended due to the difficulty of doing so. Thus, uncertainty of the effects of aid remained a wicked problem.

In sum, the main contestation during this second collaborative era concerned the validity of the various suggested responses to the increasingly complex poverty problem that had to be ‘tackled on all fronts’. Attempts were seen at the macro-level where external advisors were contracted to support in developing countries macro-economic policy development. Simultaneously, other external experts were hired to support in local bottom-up processes. There were attempts to keep experts closer to the heart of decision-making (the close consultants and LFA-advisors), but also attempts to rather keep experts at a distance (the attempts to create independent evaluation bodies). But at the end of the day, despite all these diverse attempts to tackle the complex problem on all fronts, the uncertainty of the effects of aid remained.

Ca 2005–2020s: the proper organization proxy era

At about 2005, it had become generally accepted that development is indeed complex and that it is not the role of aid organizations on their own to solve the still large and increasing development problems of the world. Rather, the suggested role of aid was often described as that of a ‘catalyst’ (Gov, Citation2003). During this third era, the uncertainty response to the main problem: development is complex, became increasingly to legitimise what we call ‘proper organizations’ through a focus on effectiveness measures. By ‘proper organization,’ we here refer to the empirical observation made that aid project results were increasingly described as dependent on organizational elements and organizational capabilities rather than on project features, contextual factors, or key individuals, for example. As one programme officer for research in the research unit at Sida explained in an interview:

So we never get down to the project level. Rather, we look at the organization that is there to support social science research.

In 2003, Sweden published its second development bill (following the first from 1962). The new bill presented eight central thematic areasFootnote4 which were described as key problems in the world. The bill further stated that these problems could not be tackled unless all policy areas (trade, agriculture, environment, security, migration, economic policy etc) and actors in all sectors of society (public authorities, local authorities, civil society organizations, private sector and trade union movement) were to work in close collaboration with each other (Gov, Citation2003). However, in contrast to the views and practices of the Collaborative turn era, it was now implied as official government policy that the complex problem of combatting poverty was not merely a problem for the public agency Sida and the other aid organizations. Responsibility was to be shared and aid organizations only played a part.

At the beginning of the 2000s, aid was increasingly criticized for not being effective. This argument that was put forth in both internationally best-selling and more popular books (Easterly, Citation2007; Moyo, Citation2009) was also heavily claimed by the Swedish centre-right Alliance government in seat since 2006. A wave of criticism from external audits, government and the media regarding ineffective and inefficient aid delivery was seen at this time which in turn led to drastic changes and several re-organizations in Swedish aid from when the alliance took office in 2006 and onwards.

During this third era, major changes were made at Sida to ensure that, first and foremost, the agency itself was seen as a proper organization (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2020), something that implied a lot of changes also when it came to the management of knowledge from external experts. The effectiveness critique had put pressure on Sida who responded by focusing even more on proper structures and procedures, on doing things ‘the right way and by the book’. As a head of unit at Sida pragmatically concluded in an interview:

It would have been much more difficult if we’d focused more on the assessments of what they [the partners] actually do.

In line with the new Law on Public Procurement from 2007 (Gov, Citation2007), procurement rules were tightened up, and external experts were now contracted mainly through larger bidding processes. Within Sida, the legal department had gained more power and streamlined both the direct procurement rules and the framework agreements by establishing budget ceilings, more specifications, etc. All in the aim of becoming a ‘proper organization’, more like other government agencies. All of this brought the closeness to external experts into question once again, which in turn implied several new anti-corruption measures, such as an external whistle-blower function and anti-bribery rules. For Sida employees, this meant that it was no longer considered appropriate to be invited to lunches and dinners by external experts and, consequently, informal communication channels were reduced. Clearly, the fear of nepotism and corruption had increased.

Internationally, measures were taken to decrease the power of organizations in the donor role and to strengthen organizations in the recipient role. The international aid effectiveness debate was coordinated by OECD DAC and the advent of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005 implied that donors were no longer to run projects and contract their own external experts and project implementation units, but rather they were to align operations with larger development country procurement- and financial management systems. Ideally, donor funds should be pooled or directly channelled through developing country systems to large sector- or national programmes. For external experts, this meant that the external expert market became more international and situated in the developing countries, which in turn required larger set-ups by the consultancy companies. All of these changes led to external experts being contracted to a lesser extent. ‘Close consultants’ were no longer procured due to the fear of nepotism. Many smaller Swedish consulting companies struggled to survive, and mid-sized firms had to merge their businesses.

However, as a consequence of this mission drift from a development actor to a proper organization, a primary task for Sida had now become to making sure that recipient partners were also considered fit as ‘proper organizations Sida’s role had thus drastically changed to legitimize proper organizations as recipients of tax-payers’ money. As an example of this shift, one programme officer stated that:

Before, we had much more focus on development … We worked collaboratively with institutions. We were part of a development process in these countries. (Today) … we’re not in touch with the state in the same way. We used to have a dialogue with the state. And who do we have a dialogue with now? It’s our partner organizations [meaning aid organizations in the recipient role in relation to Sida as a donor].

For the recipient organizations the change in focus meant that they needed to spend much more time and efforts to secure that they were seen as legitimate proper organizations, who can channel aid funding to recipients of aid. It is, for example, apparent that in the field of development aid, so-called strategic partner organizations (SPOs) occupy a highly regarded position of status among civil society organizations. One of the studied organizations, the Swedish Association for Sexual Education (Riksförbundet for sexuell upplysning, RFSU) for example invested a lot of time and efforts to conform to the many detailed requirements to become and SPO. RFSU employed two new controllers, consultants and auditors had to be consulted, and countless hours of administrative work was put into the application process. As RFSU’s secretary-general commented:

We scurried around like scalded rats the first year. It felt like there were audits upon audits, so many new systems and processes … a big leap for us indeed.

Similarly, consultants we have interviewed have reflected on the changes from 1970’ and until today. One of them reflected that ‘during those times there were organizations to whom we could say “here we don’t need anything from you, but we can only provide financing”’. Another of the consultants in the same interview stated that:

I can remember what it was like at the time and sometimes also being fascinated by how well it went and how we actually hit the spot right on and were able to get results. Yes, we saw change in ways you can only dream of. And yet … well, maybe not everything went as planned, but it doesn't now either.

Today, the recruitment base is completely different, there are almost no Swedes who have been out and worked in any kind of reality to gain an understanding. It's a completely different setting today, I think we have lost touch with reality.

Similarly, to the help-desk contract, starting in 2013, Sida has had a framework agreement for results-based management (RBM) support to recipient organizations. The way the contract works is that Sida can suggest a consultant to be contracted to support organizations in the recipient role in the writing of better aid proposals and logical frameworks for their proposals, and providing RBM training and support to recipients to become more results-oriented in general.Footnote7 Similarly as the help-desk contract, this support is aimed at organizations in the recipient role and Sida’s implementing units. And the understanding among many of those involved is that this support is offered ‘for free’ since the bills are paid by a central unit at Sida headquarters. The procedure is such that any Sida officer can request support for projects they are handling. In practice, this means that the Sida officer ‘offers’ the organization in the recipient role RBM support or support from one of the help desks. The offer is often given in conjunction with an assessment of ongoing support or new support, when the organization in the recipient role needs to submit their results framework.

Our general perception is that the main underlying aim of consultancy support today is that it is a way for organizations in the donor role (in this case Sida) to reduce their relational uncertainty at hand. Services are ‘offered’ to the potential recipient organization at times when the aid bureaucrat in charge at Sida feels uncertain about whether the potential recipient organization will deliver good results in the future. As we described in more detail in our recent open access volume (Alexius and Vähämäki, Citation2024), adopting generally legitimate structures and procedures can be viewed as ‘proper organization proxies’ (POPs) for good results. Once a potential aid recipient has received the trusted third-party services (i.e. the POP) – the donor representative generally feels more certain and can proceed with funding decisions. For example, as one of our informants, an aid bureaucrat at Sida, told us, one way to ensure that he would feel certain ‘about the investments on this horse’ (meaning a potential new recipient organization) was to make sure that the organization had received the RBM support contracted from the external experts. Similarly, the consultants from one of the RBM-consultancy companies talked about themselves as being ‘mediators’ supporting in solving problems and handling uncertainties at hand between the donor and the recipient. And as explained by a senior management consultant from the consultancy company Niras, in this era results only count if they can be presented in the proper format:

If it’s not documented, it doesn’t exist. If the results aren’t in a report, there are no results.

Conclusions and discussion: what ever happened to poverty?

The longitudinal account and analysis presented in this paper departs from an interest in the role of externally sourced experts as co-creators of aid, and more specifically, as means to reduce uncertainties of development aid operations. As summarized in Appendix 1, throughout the three identified eras, external experts have been contracted in attempts to reduce uncertainties of different kinds. Unsurprisingly, the external experts have adjusted to selling what is possible to sell at a given time, in line with shifting problem framing, conditions and demands. But all along, they have served the same important function – that of making aid organizations (particularly in the donor role) feel more confident and less uncertain of their decisions.

However, despite good intentions of co-created solutions, our analysis indicates that external experts above all have contributed to sustain the underlying contestation of aid. As seen in the historic exposé, the use of external experts has been repeatedly criticized for ineffectiveness and consultocracy. And what more, when external experts such as auditors have been contracted to bring outstanding uncertainties ‘to the table’, this has likely contributed to keep the demand high for yet another cadre of external experts – management consultants – to come in to tackle these uncertainties. Reform has indeed been a routine throughout these decades (Brunsson, Citation2009) and mechanisms of hope (Brunsson, Citation2006) and the need for confidence in complex, uncertain times (Furusten and Werr, Citation2005) have kept external consultants closer to decision-makers than the consultocracy critics would have wanted to see.

Based on the empirical account presented in this paper, we conclude that a mission drift has occurred in Swedish aid as concerns both the in-house expert role of aid bureaucrats and the role of procured experts. We have described a gradual shift from an era circa 1960s–1990’s where the problem of combatting poverty in the world was seen as rather simple and possible be solved by a ‘quick-fix’ of contracted experts from the Global North, to an era circa 1995–2005 where the problem was perceived as more complicated and requiring close relationships and joint participatory approaches with external experts. In the third era circa 2005–2020s, both the world problems and the set-up of actors have become highly complex. In this latter era, the role of both in-house experts and external experts has been reduced to that of a catalyst whose main responsibility is to justify that aid money goes to the right partners that have ‘proper’ systems to deal with aid funds.

We learn from the historical comparison that the main goal of the aid organizations (combat and reduce poverty) has remained intact over the years, but that the ways of meeting this goal have changed. The role of external experts has also undergone a change – from a view on their external expertise as the simple, technical solution, to being seen as advisors and facilitators and, today, to being perceived as legitimizers of proper donor- and recipient structures and behaviour. Over the years, the idealized expert role has thus changed. Today, external experts mainly act in the role of standard-setters – often hired to legitimize a particular process or entire organization as ‘proper’ enough. In its donor role, Sida has, for example, made substantial efforts to hire third parties to support organizations in the recipient role in becoming more results-oriented. The consequences of this mission drift (summarized in Appendix 2) are that focus of the donor agency stays at the level of securing Proper Organization Proxies rather than ‘actual’ results, as stated by the programme officer working with research aid (cited in page X above).

Discussing this mission drift to focusing on organizational proxies, one of our focus group interviewees questioned the current role of aid with its focus on proper organizational proxies, and exclaimed a spontaneous question from the heart: ‘Hey, what ever happened to poverty?’ We certainly agree that this question is worth posing at a time when many aid bureaucrats, aided by external experts, risk becoming too preoccupied with proper structures and processes and hence may spend too little time and thought on the overarching mission of poverty reduction.

As a final remark (noting once more that transformative moments are best identified post-hoc), we dare to suggest that at this time of writing in early 2024, we may well be in the eye of the perfect storm of a new transformative moment. Perhaps, the field is on the brink of the ‘Aid for Trade era’ where the rationales for altruism and solidarity and the more daunting responsibility of tackling global problems will be re-allocated from governments in the Global North who are eager to ‘cherry-pick’ trade opportunities for their industries? This time around, hope is placed on Swedish companies and trade to find solutions to the complex problems of the world. Only time will tell what happens to poverty, but a safe bet is that external experts will remain powerful co-creators, also of this unforeseen future of development aid.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Janet Vähämäki

Janet Vähämäki, PhD in Business Administration, is a Senior Research and Team Leader at Stockholm Environment Institute. Janet is affiliated researcher at Stockholm Centre for Organizational Research.

Susanna Alexius

Susanna Alexius, is an Associate Professor and research director at Stockholm Centre for Organizational at Stockholm School of Economics and Stockholm University.

Notes

1 That is, external experts have been contracted: (a) to prepare or assess a project or a financial proposal before the funding decision or to conduct specific analyses or studies concerning, for example, how a problem and its conditions will change in a certain country, portfolio, or with respect to a thematic issue – all in order to reduce uncertainties of state; (b) to support implementation during a project, to reduce uncertainties of response concerning the proper course of action to take next; and (c) to evaluate a project after it has been completed, to reduce uncertainties of effect.

2 In 1995 the original Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA) was merged with four other agencies to form the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida).

3 From the Swedish folkbildare, a concept connected with Sweden’s community-based Folk High Schools, a study association system with a long history of liberal and popular adult education.

4 The eight central thematic areas: 1. Respect for human rights 2. Democracy and good governance 3. Gender equality 4. Sustainable use of natural resources and protection of the environment 5. Economic growth 6. Social development and social security 7. Conflict management and human security 8. Global public goods.

5 Decision concerning contribution management process, including new rule for managing contributions, implementation guide and templates, new quality assurance of contribution management, and establishment of a management organization for aid processes. 2012-03-07/03079.

6 The areas covered are: Gender Equality, Democracy and Human Rights; Peace and Human Security; Environment and Climate Change; Education; Agriculture; Employment and Market Development; Anti-Corruption; Anti-corruption/Democracy and Human Rights; and Health and Sexual and Reproductive Rights.

7 The consulting company Niras (formerly InDevelop) has held the overall RBM framework agreement with Sida since 2011. In addition, a similar framework agreement with Sida’s research unit for the years 2008–2016, the aim of which is to support the research unit and Sida’s research partners with RBM implementation, was awarded to AIMS Consulting. Similar agreements exist for the nine help desks.

References

- Alexius, S., 2014, Ansvar och marknader [Responsibility and Markets], Stockholm: Liber.

- Alexius, S., D. Castillo and M. Rosenström, 2014, Contestation in transition – value configurations and market reform in the markets for gambling, coal and alcohol, in S. Alexius and K. Tamm Hallström eds, Configuring Value Conflicts in Markets, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp.178–203.

- Alexius, S. and G. Grossi, 2017, ‘Decoupling in the age of market-embedded morality: Responsible gambling in a hybrid organization’, Journal of Management and Governance, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 285–313.

- Alexius, S. and K. Tamm Hallström, Eds. 2014, Configuring Value Conflicts in Markets, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Alexius, S. and J. Vähämäki, 2020, In Proper Organization We Trust. EBA Report Series, 2020:05.

- Alexius, S. and J. Vähämäki, 2024, Obsessive Measurement Disorder or Pragmatic Bureaucracy? Coping with Uncertainty in Development aid Relations, Leeds: Emerald.

- Alvesson, M. and M. Robertson, 2006, ‘The best and the brightest: The construction, significance and effects of elite identities in consulting firms’, Organization, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 195–224.

- Alvesson, M. and K. Sköldberg, 1994, Tolkning och reflektion: Vetenskapsfilosofi och kvalitativ metod, Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Andersson, C., L. Heikensten and S. de Vylder, 1984, Bistånd i kris – en bok om svensk u-landspolitik, Stockholm: Liber Förlag.

- Bacchi, C., 2009, Analyzing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be?, Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education.

- Berg, A., U. Lundberg and M. Tydén, 2021, En svindlande uppgift. Sverige och biståndet 1945–1975, Stockholm: Ordfront Förlag.

- Binnedjikt, A., 2001, Results Based Management in the Developing Co-Operation Agencies: A Review of Experience. DAC Working Party on Evaluation, OECD/DAC.

- Brunsson, N., 2006, Mechanisms of Hope: Maintaining the Dream of the Rational Organization, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business Press.

- Brunsson, N., 2009, Reform as Routine: Organizational Change and Stability in the Modern World, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brunsson, N. and K. Sahlin-Andersson, 2000, ‘Constructing public organizations: The example of public sector reform’, Organization Studies, Vol. 21, pp. 721–746.

- Coleman, G., 1987, ‘Logical framework approach to the monitoring and evaluation of agricultural and rural development projects’, Project Appraisal, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 251–259.

- Collier, D., 2011, ‘Understanding process tracing’, Political Science & Politics, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 823–830.

- Cracknell, B. E., 1988, ‘Evaluating development assistance: A review of the literature’, Public Administration and Development, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 75–83.

- Curtis, D., 2004, ‘“How we think they think”: Thought styles in the management of international aid’, Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 415–423.

- Dietrich, S., 2021, States, Markets and Foreign Aid, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Djelic, M.-L. and S. Quack, 2007, ‘Overcoming path dependency: Path generation in open systems’, Theory and Society, Vol. 36, pp. 161–188.

- Ds (Departementserien), 1984:1, Effektivare biståndsadministration. Utrikesdepartementet.

- Ds (Departementserien), 1990:63, Bra beslut – om effektivitet och utvärdering i biståndet. Utrikesdepartementet.

- Easterly, W., 2007, The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Easterly, W., 2014, The Tyranny of Experts: Foreign Aid Versus Freedom of the World’s Poor, New York: Basic Books.

- Ewald, J. and L. Wohlgemuth, 2022, Att bygga kapacitet för ett effektivt bistånd. Historiska erfarenheter och samtida utmaningar. Linnéuniversitetet. Working Paper.

- Eyben, R., 2010, ‘Hiding relations: The irony of “effective aid”’, European Journal of Devevelopment Ressearch, Vol. 22, pp. 382–397.

- Eyben, R., I. Guijt, D. Roche and C. Shutt, 2016, The Politics of Evidence and Results in International Development: Playing the Game to Change the Rules? Warwickshire: Practical Action Publishing.

- Forss, K., J. Carlsen, E. Froyland, T. Sitari and K. Vilby, 1988, Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Technical Assistance Personel Financed by the Nordic Countries. A Study Commissioned by Danida, Finnida, NORAD, Sida. Evaluation Reports (5).

- Fourcade, M. and K. Healy, 2007, ‘Moral views of market society’, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 33, pp. 285–311.

- Fredriksson, C., 2023, Balancing Dual Actorhood in meta-organisations. Doctoral Dissertation. Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm.

- Furusten, S., 2013, Institutional Theory and Organizational Change, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Furusten, S. and A. Werr, Eds. 2005, Dealing with Confidence: The Construction of Need and Trust in Management Advisory Services, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Furusten, S. and A. Werr, Eds. 2017, The Organization of the Expert Society, London: Routledge.

- Garsten, C., B. Rothstein and S. Svallfors, 2015, Makt utan mandat: de policyprofessionella i svensk politik, Stockholm: Dialogos.

- Geertz, C., 1973, The Interpretation of Cultures – Selected Essays, New York: Basic Books.

- Gov (Government), 1962:100, Proposition nr 100 år 1962. Kungl Mäj:ts proposition till riksdagen angående svenskt utvecklingsbistånd, given Stockholms slott den 23:e februari 1962. Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Gov (Government), 1992:59, Kommittédirektiv. Utvärdering och analys av effektiviteten inom biståndsområdet, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Gov (Government), 2003, Shared Responsibility: Sweden’s Policy for Global Development. 2002/03: 122, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Gov (Government), 2007, Lag 2007:1091 om offentlig upphandling, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Gov (Government), 2010, Ny myndighetsinstruktion för Sida, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Grafström, M., M. Qvist and G. Sundström, Eds. 2021, Megaprojektet Nya Karolinska Solna. Beslutsprocesserna bakom en sjukvårdsreform, Stockholm: Makadam.

- Greenhill, R., 2006, Real Aid 2: Making Technical Assistance Work, Johannesburg: ActionAid International.

- Gulrajani, N., 2015, ‘Dilemmas in donor design: Organisational reform and the future of foreign aid agencies’, Public Administration and Development, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 152–164.

- Hintjens, H., 1999, ‘The emperor's new clothes: A moral tale for development experts?’, Development in Practice, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 382–395.

- Howell, D., C. Windahl and R. Seidel, 2010, ‘A project contingency framework based on uncertainty and its consequences’, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 28, pp. 256–264.

- Jolly, R., 1989, ‘A future for UN aid and technical assistance?’, Development, Vol. 4, pp. 21–26.

- Kipping, M., 2002, Trapped in their wave: The evolution of management consultancies, in R. Fincham and T. Clark eds, Critical Consulting: New Perspectives on the Management Advice Industry, Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell.

- Kirkpatrick, I., A. J. Sturdy, N. R. Alvarado, A. Blanco-Oliver and G. Veronesi, 2019, ‘The impact of management consultants on public service efficiency’, Policy & Politics, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 77–95.

- Koch, S. and P. Weingart, 2016, The Delusion of Knowledge Transfer: The Impact of Foreign aid Experts on Policy-Making in South Africa and Tanzania, Cape Town: African Minds.

- Lancaster, C., 2008, Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lapsley, I. and R. Oldfield, 2001, ‘Transforming the public sector: Management consultants as agents of change’, European Accounting Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 523–543.

- Loomis, R. A., 1968, ‘Why overseas technical assistance is ineffective’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 50, No. 5, pp. 1329–1341.

- Mathiason, J., P. Arora and F. Williams, 2013, Review of Research Cooperation 2006–2013. Associates for International Management Services. AIMS. October 15, 2013, Stockholm: Sida.

- Michanek, E., 1964, Vår insats för u-länderna. Tal, diskussionsinlägg, reflexioner 1964–70. U-landsbiblioteket, Stockholm: Prisma.

- Milliken, F. J., 1987, ‘Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty’, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 133–143.

- Mosse, D., 2007, ‘Notes on the ethnography of expertise and professionals in international development’, Ethnografeast III: Ethnography and the Public Sphere, pp. 1–17.

- Moyo, D., 2009, Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is Another Way for Africa, London: Penguin.

- Natsios, A., 2010, The Clash of the Counter-Bureaucracy and Development, Washington, DC: The Centre for Global Development.

- Odén, Bertil, 2013, Chapter 2: Biståndspolitiken, in D. Tarschys and M. Lemne, ed, Vad staten vill. Mål och ambitioner i svensk politik, Stockholm: Gidlunds Förlag, pp. 21–66.

- Pettersson, J., 2022, ‘Sweden’s development policy since 1990: A policy paradigm shift waiting to happen?’, Forum for Development Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 399–433.

- Raadgever, G. T., C. Dieperink, P. P. J. Driessen, A. A. H. Smit and H. F. M. W. Van Rijswick, 2011, ‘Uncertainty management strategies: Lessons from the regional implementation of the water framework directive in the Netherlands’, Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 14, pp. 64–75.

- Rothstein, B., 1992, Den korporativa staten: intresseorganisationer och statsförvaltning i svensk politik, Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Rothstein, B., C. Garsten and S. Svallfors, 2015, Makt utan mandat – De policyprofessionella i svensk politik, Stockholm: Dialogos.

- RRV (Riksrevisionsverket), 1983, Extern expertis i biståndet -granskning av SIDAs verksamhet. Revisionsrapport. Riksrevisionsverket.

- RRV (Riksrevisionsverket), 1993, Effektiviteten i förvaltningen av svenskt utvecklingssamarbete. Audit Report, Stockholm: Swedish National Audit Office.

- Runco, M. and R. Albert, 2010, Creative research: A historical view, in J. Kaufman and R. Sternberg eds, The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–19.

- Rutter, H., M. Wolpert and T. Greenhalgh, 2020, ‘Managing uncertainties in the Covid-19 era’, BMJ, Vol. 370, pp. m3349.

- Saint-Martin, D., 1998, ‘The new managerialism and the policy influence of consultants in government: An historical – institutionalist analysis of Britain, Canada and France’, Governance, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 319–356.

- Schatzman, L. and A. L. Strauss, 1973, Field Research – Strategies for a Natural Sociology, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Shutt, C., 2016, Towards an Alternative Development Management Paradigm. EBA Report 2016/07.

- Sicotte, H. and M. Bourgault, 2008, ‘Dimensions of uncertainty and their moderating effect on new product development project performance’, R&D Management, Vol. 38, pp. 468–479.

- Sida, 1996, Guidelines for the Application of LFA in Project Cycle Management, Stockholm: Sida.

- SLU, 2022, Sida’s Helpdesk for Environment and Climate Change. Final Annual Activity Report 2021, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, University of Gothenburg.

- SOU, 1990:17. Organisation och arbetsformer i bilateralt utvecklingsbistånd. Betänkande av biståndsorganisationsutredningen, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- SOU, 1993:1. Styrning och samarbetsformer i biståndet. Betänkande av kommitén rörande Styrnings- och samarbetsformer i biståndet, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- SOU, 1994:102. Analys och utvärdering av bistånd. Betänkande av kommittéen för analys av utvecklingssamarbetet, Stockholm: Government Offices.

- Stokke, O., 2019, International Development Assistance: Policy Drivers and Performance, London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- USAID, 1965, Report to the Administrator. Improving A.I.D Evaluation, Washington: Department of State. Agency for International Development.

- Vähämäki, J., 2017, Matrixing Aid: The Rise and Fall of ‘Results Initiatives’ in Swedish Development Aid, Stockholm: Stockholm Business School, Stockholm University.

- Vähämäki, J., M. Schmidt and J. Molander, 2011, Review – Results Based Management in Development Cooperation, Stockholm: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

- Wallace, T., L. Bornstein and J. Chapman, 2007, The Aid Chain: Coercion and Commitment in Development NGOs, Warwickshire: Practical Action Publishing.

- Williams, G., S. Jones, V. Imber and A. Cox, 2003, A Vision for the Future of Technical Assistance in the International Development System. Final Report, Oxford Policy Management.

- Ylönen, M. and H. Kuusela, 2019, ‘Consultocracy and its discontents: A critical typology and a call for a research agenda’, Governance, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 241–258.