Abstract

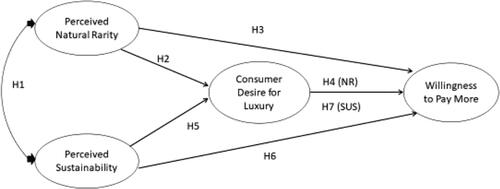

The purpose of this study is to investigate how perceived sustainability and perceived natural rarity influence willingness to pay more for luxury. The mediating role of consumer desire for luxury was also examined. Results suggest that perceived natural rarity and perceived sustainability are positively related but distinct constructs. Perceived natural rarity was found to have a significant and positive influence on consumers’ willingness to pay more, mediated by their desire for luxury. Similarly, consumer desire for luxury was also found to be a significant mediator for the relationship between perceived sustainability and willingness to pay more among consumers. This is the first paper to empirically test the relationship between perceived natural rarity and perceived sustainability. The findings provide innovative insights into the use of sustainable yet luxurious raw materials in the luxury industry, which can have significant implications for evoking consumer desires and purchasing intentions.

Introduction

Traditionally, luxury has been associated with status, wealth, rarity, and power, and has been linked to satisfying non-essential consumer desires (Phau and Prendergast Citation2000; Tynan, McKechnie, and Chhuon Citation2010). Luxury goods are perceived as rare, sophisticated pieces of workmanship that use premium raw materials, superior designs, and detailed craftsmanship (Brun and Castelli Citation2013; Phau Citation2003).

In recent years, the global luxury market has witnessed an ever-growing demand for luxury goods, represented by the emergence of younger generations and middle-class consumers (Agapie and SÎrbu Citation2020). The ease of Covid restrictions in Asian market and the financial recovering of Europe also contribute positively to the growth of luxury market (D’Arpizio and Levato Citation2023). In 2022, the personal luxury sector has achieved a market value of €345 billion, with an estimation of further 9–11% growth in 2023 (D’Arpizio and Levato Citation2023). Top performing categories, including watches and jewelry, demonstrate promising market growth, contributing to approximately €12 billion market value in 2022 (D’Arpizio and Levato Citation2023).

Contemporary consumers’ consumption for luxury is found to be influenced by multiple factors such as the social media communications (e.g., Kong, Witmaier, and Ko Citation2021), perceived value for luxury (e.g., Kautish and Sharma Citation2018; Jain Citation2020) and brands’ awareness of sustainability practices (e.g., Kunz, May, and Schmidt Citation2020). In particular, sustainable luxury is recognized as an emerging element of “new luxury”, emphasizing a business’s efforts in reducing environmental impact in manufacturing, retailing and disposal processes (Kunz, May, and Schmidt Citation2020). From consumers’ perspective, it was found that millennial consumers are increasingly conscious of sustainability issues in luxury, and they are willing to pay extra for environmentally sustainable products (Lim et al. Citation2023).

With increasing public concerns about current environmental issues, luxury brands have faced criticism for unethical practices including excessive consumption of natural resources and issues related to animal abuse (Conti, Citation2018; Rolling et al. Citation2021; Rovai and Phau Citation2003). Brands like Burberry, Hermès, and Tiffany Co. have come under scrutiny for unsustainable raw material sourcing (Chan et al. Citation2020), while Gucci, Dior, and Saint Laurent have been accused of frequently using leather and fur from rare animals (Chan et al. Citation2020). These unsustainable behaviors could diminish consumer desire and harm brand image, making it a more pressing concern in the luxury sector compared to other industries (Friedman Citation2010; Hashmi Citation2017). Consequently, luxury businesses should carefully consider the impact of increasing consumer awareness of environmental issues, particularly in the selection of raw materials and natural resources for their products (Hanson-Rasmussen and Lauver Citation2018; Teah, Sung, and Phau Citation2023).

The adoption of naturally rare and nonrenewable materials such as exotic animal skins has received much attention and criticism from social media and international press. The growing public interest in sustainability also creates a dilemma for luxury businesses: finding a balance between implementing sustainable practices while maintaining the rarity of natural materials to preserve the luxury allure for consumers (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau Citation2014; Phau Citation2003).

In recent years, luxury brands such as Yves Saint Laurent and Louis Vuitton have begun transforming their practices by using eco-friendly raw materials like organic cotton, ethically produced silk, and natural fibers, while Prada and Burberry announced their commitment to replacing the use of endangered natural resources like animal leather and fur, starting in 2020 (Prisco Citation2019). Some luxury businesses have introduced eco-friendly limited editions using superior raw materials to embody both sustainability and natural rarity (e.g., Maman Larraufie and Lui Citation2018; Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019).

There have also been investigations into the compatibility between the concepts of sustainability and luxury rarity, but with inconsistencies in findings. Campos Franco, Hussain, and McColl (Citation2019) and Nash, Ginger, and Cartier (Citation2016) found that the two concepts complement each other as they both symbolize product durability and provide higher value. In contrast, others believe luxury rarity and sustainability represent different universes (e.g., Dekhili and Achabou Citation2016; Kapferer and Michaut Citation2015). Particularly, natural rarity has been found to be positively associated with luxury brand desirability by enhancing perceptions of quality and uniqueness (Parguel, Delécolle, and Valette-Florence Citation2016; Wang, Sung, and Phau Citation2021), while sustainability information appears to negatively influence the perceived quality of luxury products (Dekhili and Achabou Citation2016; Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019).

Moreover, contradictory results have emerged regarding the influence of natural rarity and sustainability on eliciting luxury desires and actual purchasing intentions, such as willingness to pay more for luxury. Some authors suggest that naturally rare and luxurious materials initiate consumer desires and justify the premium price of luxury products (Dubois, Jung, and Ordabayeva Citation2021; Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021).

Other authors assert that rarity and expensiveness can no longer define luxury (Mundel, Huddleston, and Vodermeier Citation2017; Thomsen et al. Citation2020). For many consumers, "unconventional luxury" involves ecological factors and sustainable practices, evoking desires (e.g., enjoying clean air and water, experiencing a moment of silence in nature; Mundel, Huddleston, and Vodermeier Citation2017). Consumer desire for luxury is an important contributor to the willingness to pay a premium (Kapferer and Michaut Citation2014, Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021). Hence, the potential influences of natural rarity and sustainability on consumer desires also open a pathway for the current study to understand consumers’ willingness to pay more for luxury. The above comparison between natural rarity and sustainability raises theoretical questions: what continues to motivate consumers to pay more for luxury products? Can natural rarity and sustainability coexist in the luxury realm?

As such, the aims of this study are to understand whether (1) perceived natural rarity and perceived sustainability are related concepts in luxury and (2) consumer desire for luxury could have a positive mediating effect on the relationships between perceived natural rarity, perceived sustainability, and willingness to pay more.

Relevant literature and hypotheses development

Relationship between natural rarity and sustainability in luxury

The term ‘natural rarity’ is used to indicate the limited availability of goods due to shortages of natural and raw materials in production (Catry Citation2003; Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2016). Traditionally, luxuries were often handmade and are perceived as rare pieces of craftsmanship using only high-quality raw materials, with sophisticated design (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2018). Rarity messages are more appealing to luxury customers because they address individuals’ need for uniqueness, which can stimulate a desire to be one of the happy few to own it (Aggarwal, Jun, and Huh Citation2011; Goldsmith, Griskevicius, and Hamilton Citation2020). Maintaining rarity is also viewed as a critical success factor for luxury businesses. Luxury products containing precious materials are highly sought by luxury consumers as they symbolize authenticity, craftsmanship, and status (Brun and Castelli Citation2013; Goldsmith, Griskevicius, and Hamilton Citation2020).

The concept of sustainability was initially proposed in the 1970s to combat various social and environmental issues such as climate change, energy shortage, deterioration of the ecological environment, and exploitation of natural resources (Guercini and Ranfagni Citation2013). Sustainable manufacturing practices aim at minimizing environmental damage by using the least natural resources while optimizing the product efficacy of the company (Nordin, Ashari, and Rajemi Citation2014).

Luxury and sustainability seem to differ in many aspects. Luxury symbolizes excessiveness, superficiality, and the pursuit of personal pleasure (Dean Citation2018; Tynan, McKechnie, and Hartley Citation2014), while sustainability is often associated with moderation, altruism, and collectivism (Naderi and Strutton Citation2015; Waris, Dad, and Hameed Citation2021). Furthermore, sustainability practices concern social justice and the adequate use of natural resources, while luxury businesses are often criticized for raising social inequalities and depleting rare and natural resources. Finally, the luxury sector is also accused of animal cruelty issues such as mistreatment of animals to obtain skins and furs. Hence, the production of luxurious and prestigious products is also contrary to the idea of animal welfare within the realm of sustainability (Dekhili and Achabou Citation2016).

A more recent debate on luxury sustainability considers the compatibility between sustainability and natural rarity (e.g., Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019; Campos Franco, Hussain, and McColl, Citation2019). Some authors believe that sustainability and luxury rarity share important characteristics such as durability, reflecting the selection of natural resources that would last throughout time and thus decrease product disposal rate (Campos Franco, Hussain, and McColl Citation2019; Kunz, May, and Schmidt Citation2020). It is believed that luxury brands are able to benefit the environment through encouraging moderate consumption and promoting the reasonable use of natural resources in production (Hashmi et al. Citation2017). The promotion of using sustainable but naturally rare materials enhances the durability of luxury goods, which is fundamental to preserve brand prestige and esthetic craftsmanship (De Angelis, Amatulli, and Zaretti Citation2020).

The second characteristic is exclusivity, which reflects the carefully chosen materials used in production. For example, compared with cotton, alternative natural fabrics such as lyocell, flax, and hemp are not only perceived to be rarer and more luxurious, but they can also be bio-based and biodegradable, significantly reducing adverse environmental impacts (Donato, Buonomo, and Angelis Citation2020). Hence, there is potential for both natural rarity and sustainability to coexist in luxury production through the ethical use of naturally rare resources that are high in durability and exclusivity (Cervellon Citation2013; Hennigs et al. Citation2013). Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H1: Perceived sustainability and perceived natural rarity are distinct but positively correlated constructs

Consumer desire for luxury

Consumer desire for luxury refers to personal incentives surrounding luxury consumption as to whether a product is worth getting or having (Hennigs et al. Citation2016). Consumers’ enduring desire for luxury largely derives from the pursuit of value and status, that is, ‘respect, admiration, and voluntary deference afforded by others’ (Anderson et al. Citation2015).

The concept of desire in luxury goes far beyond limited supply and perceived rarity; it recognizes the importance of human involvement and establishing a close relationship with customers (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2018). In comparison to everyday consumption, consumers’ desire for luxury is associated with pursuing “pleasure and indulgence of the senses through objects or experiences that are more ostentatious than necessary” (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2016; Okonkwo Citation2016).

Consumer desire for luxury is a meaningful construct because it taps into the subjectivity of luxury, that is, luxury should be successfully perceived and recognized by consumers based on the functionality, price and benefits (Hudders, Pandelaere, and Vyncke Citation2013; Banister, Roper, and Potavanich Citation2020). Research has found price is a barrier to entry that can build desire for luxury products (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021). Further, consumer desire for superior quality has a positive influence on luxury perceptions (Parguel, Delécolle, and Valette-Florence Citation2016; Wang, Sung, and Phau Citation2021) and their willingness to pay premium for luxury products (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021). Brand desirability also moderates the association between consumers’ brand commitment and brand equity, which further confirms the important role of desires in luxury purchasing (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2018; Kim et al. Citation2012). Following an integrative understanding of luxury desires, the question arises of how natural rarity and sustainability affect consumer desire for luxury, which may further influence on consumers’ purchasing intentions.

Willingness to pay more for luxury

Consumers’ willingness to pay more (WTPM) reflects consumers’ actual purchasing intentions to make the necessary (monetary) sacrifice to acquire certain products or services (Koschate-Fischer, Diamantopoulos, and Oldenkotte Citation2012). A consumer’s willingness to pay a higher price is found to be a strong indicator of overall perceived value (Kiatkawsin and Han Citation2019) and brand loyalty (Naeini, Azali, and Tamaddoni Citation2015). Consumers’ WTPM is also a significant predictor for brand purchasing behavior (Siew, Minor, and Felix Citation2018).

Hudders, Pandelaere, and Vyncke (Citation2013) and Lee et al. (Citation2015) suggest that product uniqueness, brand value and perceived quality are important and direct antecedents of a consumer’s WTPM for a brand. In particular, researchers support the view that unique brand characteristics influence both consumers’ brand preferences and their willingness to pay a higher price (Siew, Minor, and Felix Citation2018; Sandra and Alessandro Citation2021). WTPM is also an important indicator for brand love, brand credibility and brand luxuriousness in luxury consumers (Dwivedi, Nayeem, and Murshed Citation2018).

According to equity theory, consumers seek to establish an equitable deal, and thus they attempt to adjust level of input in relation to the favorable outcomes and overall value they expect to receive (e.g., perceived rarity, perceived luxuriousness; Naeini, Azali, and Tamaddoni Citation2015). Specifically, luxury purchasers show more positive emotions and desires to pay for a premium price than those who have never purchased luxury brands for the benefits of status (Kim, Park, and Dubois Citation2018), rarity and exclusivity (Kim Citation2018).

Although research findings are still very limited, recent studies have shown that consumers’ attitudes, values and norms for sustainability can function as significant contributors to sustainable luxury purchase behaviors (e.g., Athwal et al. Citation2019; Eastman and Iyer Citation2021). Other factors such as consumers’ self-expression of sustainable perceptions may also influence luxury consumptions (Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019). Sustainable practices may enhance consumers’ perceived value through the increased positive perception on durability and exclusivity, and may subsequently exert an influence on willingness to pay more for luxury brands (Maman Larraufie and Lui Citation2018; Sandra and Alessandro Citation2021).

Underlying theory

Commodity theory

According to the Commodity Theory, the value of a commodity amplifies when availability of products is limited (Brock Citation1968). The Commodity Theory was first proposed by Brock (Citation1968) to explain the presence of scarcity principle. That is, consumers have an increased interest and preference for possessing somethings that is rare and hard to obtain. Consumers often use scarcity signals as heuristics cues to simplify their assessment of a product’s quality (Gierl and Huettl Citation2010; Stock and Balachander Citation2005), and price information (Suri, Kohli, and Monroe Citation2007).

In luxury literature, the commodity theory and scarcity principle are thought to be closely related to both the concepts of rarity and exclusivity, which suggested that unavailable and inaccessible products or services generally have more value than common goods (Cialdini Citation2009), and it is often used by marketers to increase the subjective desirability of products (Jung and Kellaris Citation2004). The strategies of limiting production quantity either due to natural rarity or virtual rarity are found in various product categories such as automobiles, collectables such as coins, watches, and jewelry to trigger perceived luxuriousness among consumers (Amaldoss and Jain Citation2005; Jang et al. Citation2015).

In particular, scarce messages addressing “limited quantities” are more appealing to customers because they evoke individuals’ sense of urgency to purchase the rare products while increasing the product’s value perceptions and perceived uniqueness (Aggarwal, Jun, and Huh Citation2011; Eisend Citation2008). In this situation, the decrease in product availability would increase consumers’ perceived value and desirability of the product (Aggarwal, Jun, and Huh Citation2011; Lynn Citation1991).

Social signalling theory

Luxury means different things to different people and consumers are motivated to buy luxury goods for different reasons. According to social signaling theory (Berger Citation2017; Nelissen and Meijer Citation2011), some consumers buying luxury because of its rare and exclusive properties to symbolize wealth, power and high social status (Corneo and Jeanne Citation1997; Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004). Social signaling theory suggested that brand prestige and expensiveness of luxury goods can be regarded as social cues to indicate status, identity and social stratification (Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004). For example, the upper classes “decorated” themselves with jewelry and clothes made from rare and exotic material to signal uniqueness and status (Amaldoss and Jain Citation2005). Conspicuous consumptions of rare or uncommon goods are used as means to enhance unique self-image among others, and signally effect provides an essential explanation for the main motivations of luxury purchases (Berger Citation2017; Nelissen and Meijer Citation2011). Since an individual’s social status is invisible in many cases, status signaling brands can be used as an indicator of one’s social standing over others (Ordabayeva and Chandon Citation2011). Consumers may infer the social status of other people from the prices of the products these people own (Leigh and Gabel Citation1992; Sengupta, Dahl, and Gorn Citation2002).

In luxury consumption, social signaling theory provides an explanation for consumers’ desire to signal high social status in luxury consumption (Berger Citation2017; Nelissen and Meijer Citation2011). Individuals with high needs for social approval and social status typically perceive higher-priced commodities as means to communicate social image and brand prestige to others (Jin, Park, and Yoo Citation2017).

Role of natural rarity on desire for luxury and willingness to pay more

Signaling theory captures the underlying mechanism on how rarity effect evokes desires and willingness to pay for luxury (Gierl and Huettl Citation2010). Specifically, product rarity signals brand commitment of producing limited product quantities, which enhances quality and value perceptions to potential consumers (Goldsmith, Griskevicius, and Hamilton Citation2020; Gupta and Gentry Citation2019). Rarity messages addressing naturally scarce aspect of luxury goods appeal to individuals’ desire for uniqueness, which can stimulate consumers’ desire to own it due to limited supply (Aggarwal, Jun, and Huh Citation2011; Hamilton et al. Citation2019). Based on the proceeding discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H2: Perceived natural rarity has a positive and significant influence on consumer desire for luxury

While the use of luxury and naturally scarce material create inevitable attractions to luxury consumers, the current trend of sustainable luxury consumption has placed a great challenge for the traditional implementation of natural rarity strategies in luxury. Further, in the recent years, many luxury manufacturers have outsourced their productions to low labour-cost countries, such as India and China (Canham and Hamilton Citation2013). In these manufacturing facilities, the brands are produced in large quantities and they are no longer relying on naturally rare resources to achieve promising financial outcomes. To enhance rarity perceptions and brand desires, international managers employ virtual rarity tactics such as limited-editions and exclusive brand events (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2018), focusing on building social influence and brand popularity among peer groups of consumers from collectivist culture such as China, Russia, Thailand and Turkey (Singh, Shukla, and Schlegelmilch Citation2022). Hence, it is important to understand the role of natural rarity on consumer desires and willingness to pay when mass production and affordable luxury are taken place. As such, there is a need for current research to explore how contemporary consumers perceive natural rarity in luxury. Based on the proceeding discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H3: Perceived natural rarity has a positive and significant influence on consumers’ willingness to pay more.

H4: The relationship between perceived natural rarity and willingness to pay more is positively mediated by consumer desire for luxury.

Role of perceived sustainability on desire for luxury and willingness to pay more

Product sustainability is not traditionally treated as a determinant for luxury desire, nevertheless it affects many sectors including luxury businesses (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021). In the contemporary marketplace, consumers typically look beyond traditional luxury offerings when assessing the benefits of luxury. In particular, luxury consumers are displaying great interest in business sustainable practices through social media report, which subsequently influence their thoughts on brand image, consumer desire and purchase intentions for luxury goods (Dubois, Jung, and Ordabayeva Citation2021). Contemporary consumers have demonstrated increasingly complex luxury consumption behavior considering the environmental costs and sustainable framing of luxury goods (Sun, Bellezza, and Paharia Citation2021).

Sustainable strategies contemplate the preservation of the environment (Pawłowski Citation2008) and are focus on innovation, productivity and efficient use of resources. Sustainable business behaviors include implementing innovative strategies to minimize reliance on natural resources, using alternative energy sources to reduce waste and pollutants, and encouraging eco-friendly behaviors such as recycling and erecting barriers to contamination (Pullman, Maloni, and Carter Citation2009; Sharma Citation2021).

Sustainable supply chains and environmental preservation drive luxury firms to redefine their sourcing, manufacturing and distribution processes. Sustainable and ethical practices also open new opportunities for luxury firms to foster productivity, innovation and increase brand value, which ultimately ensure a luxury brand’s long-term success (De Angelis, Adıgüzel, and Amatulli Citation2017; Kapferer and Bastien Citation2012). Specifically, the promotion of using sustainable materials enhance the durability of luxury goods, which is fundamental to preserve brand prestige and esthetic craftsmanship (Carcano Citation2013).

Contemporary consumers demonstrate more complex and sophisticated motivations for luxury purchases and luxury desires. According to the Signaling Theory (Griskevicius, Tybur, and Van den Bergh Citation2010), luxury consumers may choose to take sustainability actions for reasons other than concerns for environmental impact. Sustainability initiatives can also be triggered by factors such as pursuit for status, feelings of exclusivity and achievement, as well as the pride of engaging in prosocial behaviors (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau Citation2014; Osburg et al. Citation2021). For instance, luxury consumers purchasing expensive items expect more than rarity; they also have a desire for exclusivity (Kim Citation2018; Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie Citation2006). Enjoyment of exclusivity for sustainable product is an important emotional factor for luxury desire as it reflect consumers’ feelings that they themselves are unique (Kim Citation2018). Based on the proceeding discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H5: Perceived sustainability has a positive and significant influence on consumer desire for luxury

In marketing practice, luxury brands (such as Gucci and Hermès) have focused on developing productive processes with low environmental impact together with the use of recycling and of sustainable materials (e.g., Gucci’s eco-friendly packaging). Further, the adoption of sustainable and rare materials (e.g., vegetable leathers; bio-textiles) also add on the uniqueness of its constitutive resources, and thus produce positive influence on luxury value (Sestino, Amatulli, and De Angelis Citation2021). Alternative natural fabrics such as lyocell, flax and hemp are not only perceived to be rarer and more luxurious, but they produce less environmental damage as the raw materials (e.g., wood) can grow without harmful chemicals such as pesticides and fertilizers (Dekhili and Achabou Citation2016).

Luxury firms incorporating sustainable elements reinforce the perception of durability of natural perceived product quality, which affect consumers’ purchase motivation and thus affects consumer’s purchasing decisions (Sandra and Alessandro Citation2021; Tan et al. Citation2022). Sustainable practice also enhances brand value and brand awareness, contributing to brand desires, which further contribute to consumer’s willingness to pay premium prices (Goebel et al. Citation2018). Hence, it is essential to recognize sustainability as a distinctive element of corporate brand identity (Guercini and Ranfagni Citation2013), as well as understanding how it affects consumer desires and willingness to pay for luxury. Based on the proceeding discussion, the following hypotheses are presented:

H6: Perceived sustainability has a positive and significant influence on consumers’ willingness to pay more.

H7: The relationship between perceived sustainability and willingness to pay more is positively mediated by consumer desire for luxury.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

This study focuses on consumers who were born in Australia or live in Australia for at least five years. A total of 487 participants were recruited to complete a self-administered survey through online consumer panel Qualtrics. Before proceeding with the questionnaire, participants were asked to respond to the screening question “What is your country of birth?” Only Australian born participants or individuals selected “living in Australia for five or more years” were included in further analysis. Additionally, attention check question “If you pay attention, please select strongly agree” was also included to identity unmotivated respondents. 46 participants were excluded due to unsuccessful attention check or missing data, leaving 441 participants for further analysis. The sample was comprised of fifty-four percent female and forty-six percent male, with a mean age of 46 years (SD = 16.75).

Stimuli

The signature wallet from British luxury brand Ettinger was selected as the product stimulus to test the model. Luxury wallet from less well-known luxury brand was chosen for its relevance and capacity to evoke both sustainability and natural rarity while minimizing the influence of brand familiarity.

To assess content and face validity, two focus group interviews (n = 12) were conducted to assess the appropriateness of product categories. Participants were recruited through a snowball method involving individuals with relevant industry experiences and knowledge for luxury marketing.

The focus group interviews consisted of a general discussion of the current status of rarity and sustainability in luxury purchases, followed by the consideration of definitions and examples of natural rarity and perceived sustainability in luxury industry. Next, research design and research purposes were revealed to guide the selection of appropriate stimuli for this study.

For each group interview, participants were provided with a list of 8 luxury brands and product categories for them to identify the best representations of stimuli based on the scope of this study. Luxury wallet was selected based on the discussion of relevance to the current study. Focus group interview questions and brand descriptions are listed in Appendix A.

Product stimuli and their descriptions were based on real releases and marketing campaigns administered by the luxury brand. Stimuli descriptions for rarity emphasized on limited natural resources (e.g., the use of naturally rare cork oak). Perceived sustainability is elicited by using statement stressing the use of sustainable materials in production process. The whole questionnaire took approximately 25 to 30 min to complete. Stimuli descriptions are presented in Appendix B.

Pilot study

A pretest (73 student sample) was conducted to assess the appropriateness of the selected brands and scale items.

The student sample completed the online pretest questionnaires through the Qualtrics platform and received course credit for their completion. Stimuli descriptions and scale items are provided in Appendices B and C. The purpose of the pretest was to examine the reliability of adapted scale items. All scales have shown appropriate levels of reliability before proceeding with further testing.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument incorporated three existing scales to measure Perceived Sustainability (PSUS), Consumer desire for Luxury (DES) and Willingness to Pay More (WTP). Scale items were adapted individually to ensure they suit the context of selected product category. Perceived sustainability was measured by adapting a five-item scale from Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen (Citation2016). Consumer desire for luxury was measured by adapting the eight-item brand desirability scale from Kapferer and Valette-Florence (Citation2016). Willingness to pay more scale adopted three items from Franke and Schreier (Citation2008) examining consumers’ purchase intentions for the luxury good. In additional, perceived natural rarity (PNR) was assessed by developing a three-item scale in accordance to the definition of natural rarity proposed by Catry (Citation2003) and Kapferer and Valette-Florence (Citation2016).

All scales were reviewed to ensure acceptable levels of reliability as indicated in the original studies. Scale items were measured on 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). At the end of the survey, demographic information was recorded for each respondent. Scale items used in this study are summarized in Appendix B.

Results and analysis

Preliminary results

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations and inter-correlations were presented in . All main measures including PSUS, PNR, DES and WTP have shown positive and significant correlations.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study measures.

Reliability check

Prior to conducting factor analysis, each scale was checked for reliability level. All four scales demonstrated excellent levels of Cronbach’s Alpha: Perceived Sustainability (PSUS; α = 0.968), Perceived Natural Rarity (PNR; α = 0.921), Consumer Desire for Luxury (DES; α = 0.985), and Willingness to Pay More (WTP; α = 0.955), indicating acceptable levels of consistencies and internal reliability.

Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using maximum likelihood estimations have been conducted to assess model fit, as well as further verifying the dimensionalities and relationships among PSUS, PNR, DES and WTP. Results of CFA indicated that items loaded substantively on their corresponding factor with no clear evidence of significant cross-loadings in our sample, supporting H1. The test of measurement model produced adequate model fit (Vandenberg and Lance Citation2000; Kline Citation2011): χ2(140)=369.133, p=.000, RMSEA = 0.061, GFI = 0.920, AGFI = 0.892, TLI = 0.978 and CFI = 0.982.

Convergent validity is indicated by AVE all above 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). The discriminant validity was examined by relating the square root of each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) with the off-diagonal correlations. The AVE values were above 0.8, much higher than Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommendations. The composite reliability and internal consistency have exceeded the threshold value of 0.7, which are deemed satisfactory. presents the results of validity of the measures.

Table 2. Assess the validities and collinearity issues of variables.

In addition, collinearity issues were also considered by using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each construct. According to Shrestha (Citation2020), VIF values between 1 and 5 indicate the absence of problematic multicollinearity. As shown in , VIF values of constructs were all within the suggested range.

Common method bias

In order to check the presence of common method variance (CMV), Harman’ single-factor test was adopted in this research. Results showed that the first factor (PSUS) accounted for 44% of the variance, which is below the threshold of 50%, suggesting the absence of significant issue for CMV.

Further, common method bias was also checked in accordance with Kock and Villadsen (Citation2015)’s guideline on VIF. Any VIF values above 3.3 may suggest the presence of common method bias. The VIF values in this research ranges from 2.17 to 2.56, indicating the appropriateness of data are adequate for further analysis.

Hypothesis testing

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS version 23 were used to test the mediation effects. Hypotheses were tested for both direct and indirect effects of perceived sustainability and perceived natural rarity on willingness to pay more in the presence of consumer desire for luxury. According to Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008) findings, a significant mediation effect is present when there is a statistically significant indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator (p < 0.05).

Accordingly, the results in indicated that PNR had a significant and direct effect on DES (β = 0.688, SE = 0.055, p < 0.01), supporting H2. PNR had a significant but negative direct effect on WTP (β= −0.066, SE = 0.037, p < 0.01), rejecting H3. Further, PNR also had a significant indirect effect on WTP through DES (β =0.085, SE = 0.022, p < 0.01). This indicated the significant mediating role of DES in the association between PNR and WTP; hence H4 was supported.

Table 3. Results of the mediation analysis.

Lastly, it was found that PSUS had a significant and direct effect on DES (β= 0.562, SE = 0.040, p < 0.01), supporting H5. PSUS also had a significant and direct effect on WTP (β = 0.155, SE = 0.055, p < 0.01), supporting H6. Further, PSUS also has a significant indirect effect on WTP through DES (β= 0.443, SE = 0.023, p < 0.01). This indicates the significant mediating role of DES in the association between PSUS and WTP; hence H7 was supported.

Discussion and implications

Relationship between perceived natural rarity and perceived sustainability

Firstly, our results clearly demonstrates that perceived natural rarity and perceived sustainability are distinct but positively correlated constructs. It provides an insight to further understand the converging meanings of rarity and sustainability and how to utilize them in luxury practice. This finding also untightens the current paradox of how to keep a balance between sustainability practice and natural rarity in luxury practice (Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019; Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021). It should be noted that perceived natural rarity and sustainability are not traditionally considered as compatible concepts in luxury literature. Sustainable strategies are considered about the efficient use of resources and the preservation of the environment (Guercini and Ranfagni Citation2013). The main goal is to encourage sustainable business behaviors such as reducing waste and pollutants in production processes and minimizing reliance on natural resources (Pullman, Maloni, and Carter Citation2009).

On the other hand, the use of naturally rare materials (e.g., luxury animal hairs) seem to pose great threat to sustainability as it can lead to animal killing and mistreatment which aggravate the extinction of hair-producing animals (Gardetti and Muthu Citation2016). The use of naturally rare animal furs and leather may also lead to poaching and illegal fiber trading (Joy et al. Citation2012; Gardetti and Muthu Citation2016). Our finding demonstrated positive relationship between the two, which opens the potential benefits of combining natural rarity and sustainability in luxury marketing. Specifically, the promotion of using sustainable but naturally rare materials is found to enhance the durability of luxury goods, which is fundamental to preserve brand prestige and esthetic craftsmanship (Kapferer and Valette-Florence Citation2021).

Hence, it is important for luxury firms to incorporate sustainable elements and natural rarity, as well as recognizing sustainability as a distinctive element of corporate brand identity and brand desirability (Guercini and Ranfagni Citation2013). Taking advantage of a new business opportunity, it is therefore critical to investigate the converging meanings of luxury rarity and sustainability in luxury brands.

Role of perceived natural rarity in luxury

The current findings suggested that perceived natural rarity still plays an important role in triggering consumers’ willingness to pay more, through the mediating effect of consumer desire for luxury. In luxury consumptions, it was found that people would place more value on rare products with superior materials and esthetic craftsmanship, as it demonstrates self-distinctiveness in a social context that reinforce social status and a positive self-image (Tak et al. 2020). Kapferer and Valette-Florence (Citation2016) also demonstrated the effectiveness of using rarity strategies to enhance luxury perceptions and evoke brand desirability among consumers.

Results are also consistent with recent studies conducted by Wang, Sung, and Phau (Citation2021) demonstrate the positive influence of natural rarity on both social value and emotional value, indicating the potential usefulness of implementing natural rarity strategies to evoke consumer desire and luxury purchase intentions. It is also worth noticing that natural rarity adds unique aspect to craftsmanship and esthetics, conveying both symbolic and social value (Caniato et al. Citation2009; Hudders, Pandelaere, and Vyncke Citation2013), which may contribute to consumers’ willingness to pay more for luxury products.

Role of perceived sustainability in luxury

A positive mediating effect of consumer desire for luxury was found on the relationship between sustainability and consumers’ willingness to pay more. The recent incorporation of sustainability to luxury is a source of debate. Luxury and sustainability seem to differ in many aspects. Luxury symbolizes excessiveness, superficiality and the pursuit of personal pleasure (Dean Citation2018), while sustainability is often associated with moderation, altruism and collectivism (Naderi and Strutton Citation2015; Waris, Dad, and Hameed Citation2021). Further, sustainability practices concern about social justice and the adequate use of natural resources, while the luxury businesses are often criticized for raising social inequalities and draining rare and natural resources. Other authors propose that sustainable luxury products are compatible with luxury brand prestige and increased social power (e.g. Achabou and Dekhili Citation2013; Beckham and Voyer Citation2014). The complex and contradictory nature of sustainability and luxury can also produce conflict in thoughts and behaviors among luxury consumers.

Our findings support the notion that successful environmental initiatives would boost consumers’ willingness to pay more for luxury products. This is consistent with Hennigs et al. (Citation2013) and Carcano (Citation2013) findings suggesting that the sustainability practices have a positive influence on consumers’ brand desires through enhancing dream-imbued image of luxury products. However, it should be noted that there are existing research supporting the opposite point of view. For example, some authors (e.g., Dekhili and Achabou Citation2016; Maman Larraufie and Lui Citation2018) argue that luxury buyers of expensive products are not particularly concerned about the sustainable aspects of luxury production; some consumers even express a negative attitude toward sustainable luxury products (e.g., Janssen et al. Citation2014).

Others (e.g., Achabou and Dekhili Citation2013) found a negative association between the luxury perceptions and the presence of recycled fibers. According to the consistency theory (Festinger Citation1957), when there is inconsistency and perceived divergence between two pieces of information (e.g., luxury versus sustainability), people can either rationalize their behavior to reduce psychological discomfort (e.g., ignore sustainability issues), or they can change and act consistently with their beliefs, values and perceptions (e.g., abandon unsustainable luxury purchases). Therefore, the contradictions in results may due to the differences in respondent characterizes, age groups and education backgrounds. The inconsistent results of sustainability in luxury can also be related to the selections of sustainability materials and ethical approaches in the study designs. Hence, it is important for future research to adopt multiple product categories with diverse demographic populations to validate the current results.

Theoretical contributions

First, our study provides clearly demonstrated the overlapping and differentiating characteristics of natural rarity and sustainability through preliminary results and theoretical designs. Specifically, our results also fill a knowledge gap in previous literature by comparing the effects of natural rarity and sustainability within one experimental design. Our results provide an understanding on the differentiated functions of rarity and sustainability, as well as opening the possibility of combining the two in luxury practice to maximize consumer desires and purchase intentions. It provides valuable directions for future research to reconsider the relationship between rarity and sustainability in luxury. That is, natural rarity and sustainability should not be treated as mutually exclusive concepts, they can be regarded as complementary attributes to maximize the efficiency of luxury branding.

Second, our research is the first paper specifying the mediating role of consumer desire and how it affects the relationship between natural rarity, sustainability and consumers’ willingness to pay more. The incorporation of consumer desire enhances our understanding on how natural rarity and sustainability exert their influences on consumers’ actual purchase intentions, which has meaningful implications in luxury marketing practice. Given the complexity found in the literature regarding how environmental and social sustainable behavior and rarity affect consumer desires, and the ambiguity underlying the phenomenon of luxury purchases involving prosocial behaviors (Luomala et al. Citation2020), results of the current paper unveil the needs for a more complex model to further test how luxury desires are affected by sustainability (Kunz, May, and Schmidt Citation2020).

Further, our study unveils the current controversies regarding the compatibility between luxury and sustainability for stimulating desires and evoking purchase actions. Our results demonstrated the important status of sustainability in luxury through consumer lens, suggesting that luxury brands should make an effort to select sustainable materials of excellent quality in order maintain brand desirability and brand status.

Managerial contributions

Limited research has investigated the interactions between natural rarity and sustainability in terms of eliciting desires and actual purchasing intentions such as willingness to pay more for luxury. The current study thus provides meaningful managerial contributions on understanding the influence of natural rarity and sustainability from consumer perspectives to warrant luxury practice.

According to previous research, the association between sustainability and luxury demonstrate increasing complexity, and that sustainable luxury products seem to either strengthen or lessen consumers’ willingness to pay more depending on consumers’ feelings and desire for luxury goods (e.g., Cervellon and Shammas Citation2013). Our findings support the conjunctive use of natural but sustainable materials to evoke desires and purchase intentions. This opens the possibility of introducing sustainability as a path to integrate advanced innovations into luxury production processes, foreseeing the additional values presented by luxury sustainability practices, and revealing the purchasing motivations of green products among luxury consumers.

Further, the adoption of sustainable and rare materials (e.g., vegetable leathers) also add on the uniqueness of its constitutive resources, and thus produce positive influence on luxury value (Cervellon and Shammas Citation2013). For example, compared with cotton, alternative natural fabrics such as flax and hemp are not only perceived to be rarer and more luxurious, but they exert much less pressure on environment because it only requires modest amount of fertilizer (Dekhili, Achabou, and Alharbi Citation2019).

Overall, our studies support the view that sustainability and luxury can be compatible through the enhancement of consumer desires for luxury. In particular, our findings demonstrate that “sustainable luxury” has become an integral part of luxury brand images, as it is associated with how consumers express their desires and values in a justifiable way with social and ecological concerns (Hashmi Citation2017).

Notably, these findings highlight the current complexity and tension in regards to individuals’ distinct pursuits of meanings and benefits of luxury. Therefore, luxury brands need to respond to increasing consumer awareness, in the selection of raw materials used for their products (Kim and Ko Citation2012).

Limitations and future research

Future research should consider to use multiple product categories (e.g., luxury shoes, bags, watches) to further validate the current results. Further, this study involves primarily Australian consumers, with an average age of 46. Previous research suggests individuals’ green consumption behaviors are affected by demographic factors such as such as sex, age, education, family size and family income (Xiao and Li Citation2011). It is thus important to explore the differences between green consumers to identify their characteristics through market segmentation tools. It can be particularly interesting and useful to compare the potential differences on rarity and sustainability perceptions across multiple countries. Hence, it can be particularly important to replicate the current studies among different populations with diverse demographics to reach a meaningful valuable conclusion.

This study clearly demonstrates the prevalence of natural rarity and sustainability on enhancing consumer desires and willingness to pay more. Subsequent research should consider to extend the current findings by including potential mediators and moderators such as brand attitude, brand attachment and perceived luxuriousness, which have been shown to play critical roles in predicting luxury brand perceptions and purchase intentions (e.g., Hennigs et al. Citation2013; Kautish and Sharma Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achabou, M. A., and S. Dekhili. 2013. Luxury and sustainable development: Is there a match? Journal of Business Research 66 (10):1896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.011.

- Agapie, A. R., and G. SÎrbu. 2020. Young consumers demand sustainable and social responsible luxury. Journal of Emerging Trends in Marketing and Management 1 (1):71–81.

- Aggarwal, P., S. Y. Jun, and J. H. Huh. 2011. Scarcity messages: A consumer competition perspective. Journal of Advertising 40 (3):19–30. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367400302.

- Amaldoss, W., and S. Jain. 2005. Pricing of conspicuous goods: A competitive analysis of social effects. Journal of Marketing Research 42 (1):30–42. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.42.1.30.56883.

- Amatulli, C., M. De Angelis, D. Korschun, and S. Romani. 2018. Consumers’ perceptions of luxury brands’ CSR initiatives: An investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production 194:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.111.

- Anderson, C., J. A. D. Hildreth, L. Howland, and D. Albarracin. 2015. Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? Psychological Bulletin 141 (3):574–601. doi: 10.1037/a0038781.

- Athwal, N., V. K. Wells, M. Carrigan, and C. E. Henninger. 2019. Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 21 (4):405–26. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12195.

- Banister, E., S. Roper, and T. Potavanich. 2020. Consumers’ practices of everyday luxury. Journal of Business Research 116:458–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.003.

- Beckham, D., and B. G. Voyer. 2014. Can sustainability be luxurious? A mixed-method investigation of implicit and explicit attitudes towards sustainable luxury consumption. Advances in Consumer Research 42:245–50.

- Berger, J. 2017. Are luxury brand labels and ‘‘green’’ labels costly signals of social status? An extended replication. PLOS One 12 (2):e0170216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170216.

- Brock, T. C. 1968. Implications of commodity theory for value change. In Psychological foundations of attitudes, ed. by A. G. Greenwald, T. C. Brock, and T. M. Ostrom, 243–75. New York, NY: Academic.

- Brun, A., and C. Castelli. 2013. The nature of luxury: A consumer perspective. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41 (11/12):823–47. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-01-2013-0006.

- Campos Franco, J., D. Hussain, and R. McColl. 2019. Luxury fashion and sustainability: Looking good together. Journal of Business Strategy 41 (4):55–61. doi: 10.1108/JBS-05-2019-0089.

- Canham, S., and R. T. Hamilton. 2013. SME internationalisation: Offshoring, “backshoring”, or staying at home in New Zealand. Strategic Outsourcing 6 (3):277–91. doi: 10.1108/SO-06-2013-0011.

- Caniato, F., M. Caridi, C. M. Castelli, and R. Golini. 2009. A contingency approach for SC strategy in the Italian luxury industry: Do consolidated models fit? International Journal of Production Economics 120 (1):176–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2008.07.027.

- Carcano, L. 2013. Strategic management and sustainability in luxury companies. The IWC case. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2013 (52):36–54. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00006.

- Catry, B. 2003. The great pretenders: The magic of luxury goods. Business Strategy Review 14 (3):10–7. doi: 10.1111/1467-8616.00267.

- Cervellon, M. C. 2013. Conspicuous conservation: Using semiotics to understand sustainable luxury. International Journal of Market Research 55 (5):695–717. doi: 10.2501/IJMR-2013-030.

- Cervellon, M. C., and L. Shammas. 2013. The value of sustainable luxury in mature markets: A customer-based approach. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2013 (52):90–101. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00009.

- Chan, H. L., X. Wei, S. Guo, and W. H. Leung. 2020. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in fashion supply chains: A multi-methodological study. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 142:102063. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.102063.

- Chan, W. Y., C. K. To, and W. C. Chu. 2015. Materialistic consumers who seek unique products: How does their need for status and their affective response facilitate the repurchase intention of luxury goods? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.07.001.

- Cialdini, R. B. 2009. Influence: Science and practice. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Conti, S. 2018. Plastic waste fuels the fire in faux vs. real fur debate: Women’s wear daily. WWD, 20–21. https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/plastic-waste-fuels-fire-faux-vs-real-fur-debate/docview/2251000410/se-2.

- Corneo, G., and O. Jeanne. 1997. Conspicuous consumption, snobbism and conformism. Journal of Public Economics 66 (1):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(97)00016-9.

- D’Arpizio, C., and F. Levato. 2023. Bain & Co Luxury goods worldwide market study. Bain & Company. https://www.bain.com/about/media-center/press-releases/2023/ global-personal-luxury-goods-market-reaches-288-billion-in-value-in2023-and-experienced-a-remarkable-performance-in-the-firstquarter-2023/.

- Dean, A. 2018. Everything is wrong: A search for order in the ethnometaphysical chaos of sustainable luxury fashion. The Fashion Studies Journal. http://www.fashionstudiesjournal.org/5-essays/2018/2/25/ everything-is-wrong-a-search-for-order-in-the-ethnometaphysical-chaos-of-sustainable-luxury-fashion.

- De Angelis, M., F. Adıgüzel, and C. Amatulli. 2017. The role of design similarity in consumers’ evaluation of new green products: An investigation of luxury fashion brands. Journal of Cleaner Production 141:1515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.230.

- De Angelis, M., C. Amatulli, and M. Zaretti. 2020. The artification of luxury: How art can affect perceived durability and purchase intention of luxury products. Sustainable Luxury and Craftsmanship :61–84.

- Dekhili, S., and M. A. Achabou. 2016. Luxe et développement durable: Quelles sources de dissonance. Décisions Marketing 83 (3):97–121. doi: 10.7193/DM.083.97.121.

- Dekhili, S., and M. A. Achabou. 2016. Is it beneficial for luxury brands to embrace CSR practices? Celebrating America’s pastimes: Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and marketing? Proceedings of the 2015 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference, 3–18. Springer International Publishing.

- Dekhili, S., M. A. Achabou, and F. Alharbi. 2019. Could sustainability improve the promotion of luxury products? European Business Review 31 (4):488–511. doi: 10.1108/EBR-04-2018-0083.

- Demirgüneş, B. K. 2015. Relative importance of perceived value, satisfaction and perceived risk on willingness to pay more. International Review of Management and Marketing 5 (4):211–20.

- Donato, C., A. Buonomo, and M. De Angelis. 2020. Environmental and social sustainability in fashion: A case study analysis of luxury and mass-market brands. In Sustainability in the textile and apparel industries. Sustainable textiles: Production, processing, manufacturing & chemistry, ed. S. Muthu and M. Gardetti. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-38532-3_5.

- Dubois, D., S. Jung, and N. Ordabayeva. 2021. The psychology of luxury consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology 39:82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.011.

- Dwivedi, A., T. Nayeem, and F. Murshed. 2018. Brand experience and consumers’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) a price premium: Mediating role of brand credibility and perceived uniqueness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 44:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.06.009.

- Eastman, J. K., and R. Iyer. 2021. Understanding the ecologically conscious behaviors of status motivated millennials. Journal of Consumer Marketing 38 (5):565–75. doi: 10.1108/JCM-02-2020-3652.

- Eisend, M. 2008. Explaining the impact of scarcity appeals in advertising. Journal of Advertising 37 (3):33–40. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367370303.

- Festinger, L. 1957. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row Peterson.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Franke, N., and M. Schreier. 2008. Product uniqueness as a driver of customer utility in mass customization. Marketing Letters 19 (2):93–107. doi: 10.1007/s11002-007-9029-7.

- Friedman, V. 2010. Sustainable fashion: what does green mean? Financial Times, London. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/2b27447e-11e4–11df-b6e3-00144feab49a.html.

- Gardetti, M. A., and S. S. Muthu. 2016. Sustainable apparel? Is the innovation in the business model?-The case of IOU Project. Textiles and Clothing Sustainability 1 (1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40689-015-0003-0.

- Gierl, H., and V. Huettl. 2010. Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Research in Marketing 27 (3):225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.02.002.

- Goebel, P., C. Reuter, R. Pibernik, C. Sichtmann, and L. Bals. 2018. Purchasing managers’ willingness to pay for attributes that constitute sustainability. Journal of Operations Management 62 (1):44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2018.08.002.

- Goldsmith, K., V. Griskevicius, and R. Hamilton. 2020. Scarcity and consumer decision making: Is scarcity a mindset, a threat, a reference point, or a journey? Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 5 (4):358–64. doi: 10.1086/710531.

- Griskevicius, V., J. M. Tybur, and B. Van den Bergh. 2010. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (3):392–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017346.

- Guercini, S., and S. Ranfagni. 2013. Sustainability and luxury: The Italian case of a supply chain based on native wools. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2013 (52):76–89. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00008.

- Gupta, S., and J. W. Gentry. 2019. Should I buy, hoard, or hide?’ Consumers’ responses to perceived scarcity. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 29 (2):178–97. doi: 10.1080/09593969.2018.1562955.

- Hamari, J., M. Sjöklint, and A. Ukkonen. 2016. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 67 (9):2047–59. doi: 10.1002/asi.23552.

- Hamilton, R., D. Thompson, S. Bone, L. N. Chaplin, V. Griskevicius, K. Goldsmith, R. Hill, D. R. John, C. Mittal, T. O’Guinn, et al. 2019. The effects of scarcity on consumer decision journeys. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47 (3):532–50. doi: 10.1007/s11747-018-0604-7.

- Hanson-Rasmussen, N. J., and K. J. Lauver. 2018. Environmental responsibility: Millennial values and cultural dimensions. Journal of Global Responsibility 9 (1):6–20. doi: 10.1108/JGR-06-2017-0039.

- Hashmi, G. 2017. Redefining the essence of sustainable luxury management: The slow value creation model. In Sustainable management of luxury. Environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes, ed. M. Gardetti. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-2917-2_1.

- Hashmi, G. J., G. Dastageer, M. S. Sajid, Z. Ali, M. F. Malik, and I. Liaqat. 2017. Leather industry and environment: Pakistan scenario. International Journal of Applied Biology and Forensics 1 (2):20–5.

- Hennigs, N., K. P. Wiedmann, C. Klarmann, and S. Behrens. 2013. Sustainability as part of the luxury essence: Delivering value through social and environmental excellence. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2013 (52):25–35. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00005.

- Hennigs, N., C. Klarmann, S. Behrens, and K. P. Wiedmann. 2016. Consumer desire for luxury brands: Individual luxury value perception and luxury consumption. In Looking forward, looking back: Drawing on the past to shape the future of marketing. Developments in marketing science: Proceedings of the academy of marketing science, ed. C. Campbell and J. Ma. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24184-5_78.

- Hudders, L., M. Pandelaere, and P. Vyncke. 2013. Consumer meaning making: The meaning of luxury brands in a democratised luxury world. International Journal of Market Research 55 (3):391–412. doi: 10.2501/IJMR-2013-036.

- Jain, S. 2020. Role of conspicuous value in luxury purchase intention. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 39 (2):169–85. doi: 10.1108/MIP-03-2020-0102.

- Janssen, C., J. Vanhamme, A. Lindgreen, and C. Lefebvre. 2014. The Catch-22 of responsible luxury: Effects of luxury product characteristics on consumers’ perception of fit with corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 119 (1):45–57. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1621-6.

- Jang, W. E., Y. J. Ko, J. Morris, and Y. H. Chang. 2015. Scarcity message effects on consumption behaviour: Limited edition product considerations. Psychology & Marketing 32 (10):989–1001. doi: 10.1002/mar.20836.

- Jin, Y. J., S. C. Park, and J. W. Yoo. 2017. Effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer credibility perception and attitude toward luxury brands. Social Behavior and Personality 45 (5):795–808. doi: 10.2224/sbp.5897.

- Joy, A., J. F. Sherry, Jr, A. Venkatesh, J. Wang, and R. Chan. 2012. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fashion Theory 16 (3):273–95. doi: 10.2752/175174112X13340749707123.

- Jung, J. M., and J. J. Kellaris. 2004. Cross-national differences in proneness to scarcity effects: The moderating roles of familiarity, uncertainty avoidance, and need for cognitive closure. Psychology & Marketing 21 (9):739–53. doi: 10.1002/mar.20027.

- Kapferer, J. N., and V. Bastien. 2012. The luxury strategy: Break the rules of marketing to build luxury brands. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Kapferer, J. N., and A. Michaut-Denizeau. 2014. Is luxury compatible with sustainability? Luxury consumers’ viewpoint. Journal of Brand Management 21 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.19.

- Kapferer, J.-N., and A. A. Michaut. 2015. Luxury and sustainability: A common future? The match depends on how consumers define luxury. Luxury Research Journal 1 (1):3. doi: 10.1504/LRJ.2015.069828.

- Kapferer, J.-N., and P. Valette-Florence. 2016. Beyond rarity: The paths of luxury desire. How luxury brands grow yet remain desirable. Journal of Product & Brand Management 25 (2):120–33. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-09-2015-0988.

- Kapferer, J. N., and P. Valette-Florence. 2018. The impact of brand penetration and awareness on luxury brand desirability: A cross country analysis of the relevance of the rarity principle. Journal of Business Research 83:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.09.025.

- Kapferer, J. N., and P. Valette-Florence. 2021. Which consumers believe luxury must be expensive and why? A cross-cultural comparison of motivations. Journal of Business Research 132:301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.003.

- Kautish, P., and R. Sharma. 2018. Consumer values, fashion consciousness and behavioural intentions in the online fashion retail sector. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 46 (10):894–914. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-03-2018-0060.

- Kiatkawsin, K., and H. Han. 2019. What drives customers’ willingness to pay price premiums for luxury gastronomic experiences at michelin-starred restaurants? International Journal of Hospitality Management 82:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.024.

- Kim, Y. 2018. Power moderates the impact of desire for exclusivity on luxury experiential consumption. Psychology & Marketing 35 (4):283–93. doi: 10.1002/mar.21086.

- Kim, A. J., and E. Ko. 2012. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research 65 (10):1480–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.014.

- Kim, K. H., E. Ko, B. Xu, and Y. Han. 2012. Increasing customer equity of luxury fashion brands through nurturing consumer attitude. Journal of Business Research 65 (10):1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.016.

- Kim, J. C., B. Park, and D. Dubois. 2018. How consumers’ political ideology and status-maintenance goals interact to shape their desire for luxury goods. Journal of Marketing 82 (6):132–49. doi: 10.1177/0022242918799699.

- Kline, R. B. 2011. Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In The SAGE handbook of innovation in social research methods, 562–89. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kock, C., and L. Villadsen. 2015. Contemporary rhetorical citizenship. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Kong, H. M., A. Witmaier, and E. Ko. 2021. Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. Journal of Business Research 131:640–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.021.

- Koschate-Fischer, N., A. Diamantopoulos, and K. Oldenkotte. 2012. Are consumers really willing to pay more for a favorable country image? A study of country-of-origin effects on willingness to pay. Journal of International Marketing 20 (1):19–41. doi: 10.1509/jim.10.0140.

- Kunz, J., S. May, and H. J. Schmidt. 2020. Sustainable luxury: Current status and perspectives for future research. Business Research 13 (2):541–601. doi: 10.1007/s40685-020-00111-3.

- Lee, M., E. Ko, S. Lee, and K. Kim. 2015. Understanding luxury disposition. Psychology & Marketing 32 (4):467–80. doi: 10.1002/mar.20792.

- Leigh, J. H., and T. G. Gabel. 1992. Symbolic interactionism: Its effects on consumer behaviour and implications for marketing strategy. Journal of Consumer Marketing 9 (1):27–38. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000002594.

- Lim, X. J., J. H. Cheah, L. V. Ngo, K. Chan, and H. Ting. 2023. How do crazy rich Asians perceive sustainable luxury? Investigating the determinants of consumers’ willingness to pay a premium price. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 75:103502. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103502.

- Luomala, H., P. Puska, M. Lähdesmäki, M. Siltaoja, and S. Kurki. 2020. Get some respect–buy organic foods! When everyday consumer choices serve as prosocial status signaling. Appetite 145:104492. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104492.

- Lynn, M. 1991. Scarcity effects on value: A quantitative review of the commodity theory literature. Psychology & Marketing 8 (1):43–57. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220080105.

- Maman Larraufie, A. F., and L. S. H. Lui. 2018. How do western luxury consumers relate with virtual rarity and sustainable consumption? In Emerging issues in global marketing: A shifting paradigm, ed. J. Agarwal and T. Wu, 311–32. Cham: Springer.

- Muthu, S. S., and M. A. Gardetti, eds. 2016. Sustainable fibres for fashion industry. Vol. 1. Singapore: Springer.

- Mundel, J., P. Huddleston, and M. Vodermeier. 2017. An exploratory study of consumers’ perceptions: What are affordable luxuries? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 35:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.12.004.

- Naderi, I., and D. Strutton. 2015. I support sustainability but only when doing so reflects fabulously on me. Can green narcissists be cultivated? Journal of Macromarketing 35 (1):70–83. doi: 10.1177/0276146713516796.

- Naeini, A., P. R. Azali, and K. S. Tamaddoni. 2015. Impact of brand equity on purchase intention and development, brand preference and customer willingness to pay higher prices. Management and Administrative Sciences Review 4 (3):616–26.

- Nash, J., C. Ginger, and L. Cartier. 2016. The sustainable luxury contradiction: Evidence from a consumer study of marine-cultured pearl jewellery. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2016 (63):73–95. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2016.se.00006.

- Nelissen, R. M. A., and M. H. C. Meijer. 2011. Social benefits of luxury brands as costly signals of wealth and status. Evolution and Human Behavior 32 (5):343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.12.002.

- Nordin, N., H. Ashari, and M. F. Rajemi. 2014. A case study of sustainable manufacturing practices. Journal of Advanced Management Science 2 (1):12–6. doi: 10.12720/joams.2.1.12-16.

- Okonkwo, U. 2016. Luxury fashion branding: Trends, tactics, techniques. Cham: Springer.

- Ordabayeva, N., and P. Chandon. 2011. Getting ahead of the joneses: When equality increases conspicuous consumption among bottom-tier consumers. Journal of Consumer Research 38 (1):27–41. doi: 10.1086/658165.

- Osburg, V. S., I. Davies, V. Yoganathan, and F. McLeay. 2021. Perspectives, opportunities and tensions in ethical and sustainable luxury: Introduction to the thematic symposium. Journal of Business Ethics 169 (2):201–10. doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04487-4.

- Parguel, B., T. Delécolle, and P. Valette-Florence. 2016. How price display influences consumer luxury perceptions. Journal of Business Research 69 (1):341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.006.

- Park, J., H. J. Eom, and C. Spence. 2022. The effect of perceived scarcity on strengthening the attitude-behavior relation for sustainable luxury products. Journal of Product & Brand Management 31 (3):469–83. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-09-2020-3091.

- Pawłowski, A. 2008. How many dimensions does sustainable development have? Sustainable Development 16 (2):81–90. doi: 10.1002/sd.339.

- Phau, I. 2003. Luxury “Made in Italy” and Sustainability. In Made in Italy and the luxury market: Heritage, sustainability and innovation, ed. by Serena Rovai and Manuela De Carlo, 275–81. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Phau, I., and G. Prendergast. 2000. Conceptualizing the country of origin of brand. Journal of Marketing Communications 6 (3):159–70. doi: 10.1080/13527260050118658.

- Preacher, K. J., and A. F. Hayes. 2008. Assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research, 13–54. London: Sage.

- Prisco, J. 2019. Prada to go fur-free in 2020. https://www.cnn.com/style/ article/prada-goes-fur-free-2020/index.html.

- Pullman, M. E., M. J. Maloni, and C. R. Carter. 2009. Food for thought: Social versus environmental sustainability practices and performance outcomes. Journal of Supply Chain Management 45 (4):38–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-493X.2009.03175.x.

- Rovai, I., and I. Phau. 2003. Consumers’ commitment to brand recognition: Diesel sustainability strategy for “responsible living” & the second-hand. In Made in Italy and the luxury market: Heritage, sustainability and innovation, ed. By Serena Rovai and Manuela De Carlo, 28–37. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Riot, E., C. Chamaret, and E. Rigaud. 2013. Murakami on the bag: Louis Vuitton’s decommoditization strategy. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41 (11/12):919–39. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-01-2013-0010.

- Rolling, V., C. Seifert, V. Chattaraman, and A. Sadachar. 2021. Pro‐environmental millennial consumers’ responses to the fur conundrum of luxury brands. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (3):350–63. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12626.

- Sandra, N., and P. Alessandro. 2021. Consumers’ preferences, attitudes and willingness to pay for bio-textile in wood fibers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58:102304. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102304.

- Sharma, A. P. 2021. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (6):1217–38. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12722.

- Sengupta, J., D. W. Dahl, and G. J. Gorn. 2002. Misrepresentation in the consumer context. Journal of Consumer Psychology 12 (2):69–79. doi: 10.1207/S15327663JCP1202_01.

- Sestino, A., C. Amatulli, and M. De Angelis. 2021. Consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable luxury products: The role of perceived uniqueness and conspicuous consumption orientation. Handloom Sustainability and Culture: Entrepreneurship, Culture and Luxury :267–79.

- Shrestha, N. 2020. Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics 8 (2):39–42. doi: 10.12691/ajams-8-2-1.

- Siew, S. W., M. S. Minor, and R. Felix. 2018. The influence of perceived strength of brand origin on willingness to pay more for luxury goods. Journal of Brand Management 25 (6):591–605. doi: 10.1057/s41262-018-0114-4.

- Singh, J., P. Shukla, and B. B. Schlegelmilch. 2022. Desire, need, and obligation: Examining commitment to luxury brands in emerging markets. International Business Review 31 (3):101947. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101947.

- Stock, A., and S. Balachander. 2005. The making of a “hot product”: A signaling explanation of marketers’ scarcity strategy. Management Science 51 (8):1181–92. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1050.0381.

- Sun, J. J., S. Bellezza, and N. Paharia. 2021. Buy less, buy luxury: Understanding and overcoming product durability neglect for sustainable consumption. Journal of Marketing 85 (3):28–43. doi: 10.1177/0022242921993172.

- Suri, R., C. Kohli, and K. B. Monroe. 2007. The effects of perceived scarcity on consumers’ processing of price information. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 35 (1):89–100. doi: 10.1007/s11747-006-0008-y.

- Tak, P, Department of Marketing, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, India. 2020. Antecedents of luxury brand consumption: An emerging market context. Asian Journal of Business Research 10 (2):23–44. doi: 10.14707/ajbr.200082.

- Tan, Z., B. Sadiq, T. Bashir, H. Mahmood, and Y. Rasool. 2022. Investigating the impact of green marketing components on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand image and brand trust. Sustainability 14 (10):5939. doi: 10.3390/su14105939.

- Teah, K., B. Sung, and I. Phau. 2023. Examining the moderating role of principle-based entity of luxury brands and its effects on perceived CSR motives, consumer situational scepticism and brand resonance. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 27 (5):784–809. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-03-2022-0066.

- Thomsen, T. U., J. Holmqvist, S. von Wallpach, A. Hemetsberger, and R. W. Belk. 2020. Conceptualizing unconventional luxury. Journal of Business Research 116:441–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.058.

- Tynan, C., S. McKechnie, and C. Chhuon. 2010. Co-creating value for luxury brands. Journal of Business Research 63 (11):1156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.10.012.

- Tynan, C., S. McKechnie, and S. Hartley. 2014. Interpreting value in the customer service experience using customer-dominant logic. Journal of Marketing Management 30 (9–10):1058–81. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2014.934269.

- Vandenberg, R. J., and C. E. Lance. 2000. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods 3 (1):4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002.

- Vigneron, F., and L. W. Johnson. 2004. Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management 11 (6):484–506. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540194.

- Wang, X., B. Sung, and I. Phau. 2021. Examining the influences of perceived exclusivity and perceived rarity on consumers’ perception of luxury. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 26 (2):365–82. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-12-2020-0254.

- Waris, I., M. Dad, and I. Hameed. 2021. Promoting environmental sustainability: The influence of knowledge of eco-labels and altruism in the purchase of energy-efficient appliances. Management of Environmental Quality 32 (5):989–1006. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-11-2020-0272.

- Xiao, J. J., and H. Li. 2011. Sustainable consumption and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research 104 (2):323–9. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9746-9.

- Yeoman, I., and U. McMahon-Beattie. 2006. Luxury markets and premium pricing. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 4 (4):319–28. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.rpm.5170155.

Appendices

Appendix A. Focus group interview questions

Generic questions:

What was your recent luxury purchase?

From which brand

What was the product /service category?

Do you have desires to purchase luxury products?

Think back and tell us why you decided to buy it.

What were some of the motivations for your purchase?

Was it worth purchasing the item? Are you willing to pay more for your purchase?

What are some of the benefits you derived from that purchase? Were you happy with your purchase/ were you regret? Why/ Why not?

Questions for rarity and sustainability:

Introduce the conceptualisations of sustainability and rarity respectively.

Do you think a brand’s sustainable practice is important for your luxury purchases?

Do you think it is important for luxury brands to keep maintaining rarity?

Do you think product rarity is important for your luxury purchases?

Do you have desire for luxury products, is the desire associated with rarity or sustainability, or any other factors?