Abstract

This essay discusses popular life writing by younger Danish writers descending from immigrants. It focuses on selected works, within the last two decades, that all have had significant presence in public sphere debates or caused controversy. The books in different ways addresses struggles around intergenerational memory and it is argued that the works can be seen as ways of trying to re-approach life in an ambiguous as well as insightful engagement with one’s heritage as well as a majority culture.

In recent decades, popular life writing by younger Danish authors descending from immigrants has emerged, making a mark on the public sphere by addressing struggles around intergenerational memory and inheritance, and new ways forward. These authors have gained a wide readership, some of them beyond Denmark. In this essay, I focus on authors and narrators that are children of refugees or immigrating parents.Footnote1 I concentrate on descendants of parents from Middle Eastern countries and the artistic and political practice of exploring an ambiguous insight, or vision, toward themselves and society.

My focus is self-expression as a source of knowledge in writings, which can be seen as ways of trying to re-approach life, in an ambigious as well as insightful engagement with one’s heritage as well as a majority culture. The sources, or experiences, and sights fueling the writing lead some of the authors to either difficult or deadly forms of public exposure. I consider books written over two decades, 2003–2019, which all have had a significant impact in the public sphere, and which each employ different tools of literary life writing. The examples include genres of autobiography, “told-to” memoir, fiction, poetry, and cowritten memoir by women and men, primarily works produced while the authors were in their 20s or early 30s.Footnote2 To limit the pool of texts, I am engaging with early autobiographical forms in which the formulation of young adult identity and development happened in tandem with the autobiographical writing. I have also chosen works in which authors provide bold and critical looks at their own families or social circles and caused some controversy and tension within their own families and communities.Footnote3 Their focus on migratory backgrounds and communities can lead to a sense of siege in which the authors become framed and appropriated as immigrant authors who provide critiques of Islam, Middle Eastern communities, or parental culture, in a process of integration to Denmark.

The essay has three subsections. The first, Veils and Second Sights, presents the key texts and lays out the theoretical framework, and Negotiating Different Histories in One Person enters the analysis focusing on the women authors. One author, Geeti Amiri, is given primary attention. The second subsection, Leaving the Concrete Block: Roots and Routes, focuses mainly on examples from men, with emphasis on Nedim Yasar. The third and final section, Fiction and Life Writing as Forethought of Change, ends the article with a comparative and summative discussion of the pool of writings engaged with as well as reflects on the tension between the authors’ personal histories and the familial and societal histories that they work through, but also the appropriations or interpretations that have dominated the reception of the books.

Authors, Veils, and Second Sights

The authors included in this diverse selection of texts all portray intergenerational battles by articulating a particular coping mechanism and skill in which the scene of writing autofictionally, and what we might call their hybrid identity experiences, works toward healing, balance, and a new form of “second sight” reformulated from early American sociologist and author W.E.B. DuBois’s work The Souls of Black Folk. DuBois only used the term in passing, and it appears synonymous with another scarcely used concept, “double consciousness.” However, DuBois writings around the topic of negotiating a complex identity is nevertheless extensively debated by his interpreters (Gilroy (1993) and Pittman (2016) among many). I include in this diverse group books of Ahmad Mahmoud (2015), Yahya Hassan (2013, 2019), Nedim Yasar (2018), Geeti Amiri (2016), Rushy Rashid (2003), Özlem Cekic (2009), and Sara Omar (2017). All representatives of literary life writing with a strong auto/biographical aspect narrated (or told-to) in tandem with the formation of adult identities and careers when the authors were in the 20s or early 30s (except for, a then-teenage, Hassan debuting at the age of 18).

Although working from the context of Black lives in the USA in the aftermath of slavery, DuBois also introduces the notion of “the veil” adapted here as an attitude and practice for hiding as well as handling or diffusing identity.Footnote4 DuBois’ notion draws from the bible: Moses covering his face for God, or Isaiah saying God will destroy and a veil will be spread over the nations. It is my argument that all the books take on a more elaborate understanding of veiling, some with clues already in the title, for example, Amiri’s Gloss images and Rashid’s Behind the Veil. In this essay, veiling becomes an embodied ability to make use of an ambiguous “second sight”Footnote5 interpreted by Perkins as a discursive device and a metaphor that may stand for “a shamanistic ability to see beyond the ordinary.”Footnote6 I will leave behind the shamanism, but am intrigued by the potential of “second sight” as a discursive device, its reach beyond the ordinary, and its avoidance of splitting the world into two-ness. However, “Double consciousness,” is, according to Du Bois, doing this splitting: “two warring souls, two thoughts, two irreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body.”Footnote7 Du Bois also noted that when stimulated or directed, “double consciousness” can also lead to higher awareness and discovery.Footnote8 For this essay, I am interested in a potential writerly second sight in which the authors place themselves in or/and manage different spaces and expressions of identity and use their potential second sight to process and live their lives.

DuBois spent time in Germany as part of his PhD before returning to Harvard to finish his degree. It makes sense that he would reflect on his double lineage—a White father, a Black mother, and an educational journey that involved both the largely Black Fisk University, to Humboldt, Berlin in Germany, and then to Harvard, Boston, USA. The notion of “double consciousness” may be more useful approached as more than “this sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others.” It is also a “recognition of an entire social situation,” thus not only a problem of consciousness Pittman notices in a thorough tracing of the concept and its drawbacks (which may explain why DuBois himself only used it sporadically).Footnote9 “Second sight” may hold a door open for a knowledge acquired from the resourcefulness of “double consciousness,” a problematic aspect of which may be forms of veiling siege of identity performance. Second sight can be understood as a more positive term, which involves the capacity to see through others while these others are not able to see that their behaviors and thoughts are revealed.

To theoretically develop the different forms of veiling, I propose (drawing from DuBois, 1903) distinguishing between the following: a demarcation (1) between Black and White skin, but also (2) as a way a majority culture, for example whites, are unable to see others (e.g., Blacks) as equal Americans and categorize “other” minorities. This can be transferred to another context in which Muslims are similarly not recognized as Danes, or crudely othered in various ways. Lastly (3) is the work with a second sight, here understood as a potential discursive ability and creativity; an ambiguous onlooking and insight in which different forces are at play. Hypothetically, we may place emphasis on a general pattern of ruptures and intensification of time in the immigratory experience. The presence of a past time before a move and the intense impression of a new place, either lived or learned in person (“History in Person”) or felt through friends or family members stories or traumas or issues, is acted upon. Most of the subjects are close to parents whose stories and experiences they have difficulties comprehending. Further, there is also an intensification of space in the present due to how one’s difference is met. A defensive aspect of second sight is a limiting form of seeing yourself as you are seen by the majority and more than an ability of seeing to adapt or “get in line.” Instead, it also incorporates forms of vision that move beyond framing; it may transform the meaning of Black (and White) or/and take on inter/cross-sectional formats, as forms of mixedness, multitude, and ambiguity that rejects or move away from simplistic identity politics. This adaptation of second sight is a form of fuzziness or reclusiveness—adapted from Glissant’s opacity (1997) in which one steps into a position that is difficult to frame by the gazer, as if the gazed upon is equipped or masked with an extra knowledge or experience, an additional repertoire. One may appropriate cultural codes, through music, dress, accent, and so forth sometimes coming together in a repertoire unusually merged in one individual.

Negotiating Different Histories in One Person

Geeti Amiri engages with an empathetic portrayal of her own identity work and journey, but also of the battles of her parents. She writes, “One of the greatest lies in an Afghan girl’s life is that if you obey your parents, happiness will come to you and give you joy through life. My mother followed that path but have never met happiness.”Footnote10 Early in the book she announces that she “has a dream of the return of a box with my family’s lost personal possessions, the photos that remained, telling the stories of the ruins of Kabul, documents that would fulfil my identity.” She knows however, she continues, that when she wakes up there is “no box, no complete history.”Footnote11 In her writerly search for a stable and full account of her identity, she is coping with what is lost and what she tries gaining when she says, “Contrary to age, loneliness is static. I have seen my mother being lonely all her life, also when my father was alive. Her loneliness has been crushing, young as old.”Footnote12 This process is depicted in reflections on the mother and father, relationships, and education, where I will mainly concentrate on the ‘work’ on the father and mother relationships in this article.

Geeti Amiri published an autobiography, Glansbilleder, Gloss Images, in 2016, at the age of 27. She had for a few years in the mid-2010s made a mark in the public sphere as an outspoken blogger, columnist, and radio presenter. Her public image and participation could indicate an already successful or accomplished transition to a life in Denmark. A Danish left-leaning daily called her a “role model,” “pattern breaker,” “a strong immigrant voice,” and one who speaks “against patriarchy and traditions”Footnote13 perhaps for statements such as, “In Afghanistan it is said that paradise is at your mother’s feet. I have always felt as a miserable daughter to my mother. My paradise was at my father’s side, but he left me to be in God’s paradise.”Footnote14 Gloss Images provides her own unraveling of her life so far—the title already demonstrating her awareness of different forms of appearance.

The memoir is a process-account of finding one’s feet, coming to terms with failed relationships, in the family and outside, trying to mourn and heal a loss of her father—and of her childhood. She writes, “I am 27 and I still mourn the lost child in myself and as long I mourn the lost childhood, I will never be Afghan, because an Afghan woman has no childhood.”Footnote15 Her deceased father is held in strong regard, and the memory work unfolding his virtues and his impact are pronounced in the book—and so are the two years taking care of him (while she was a teenager) during a period of illness before his death. Amiri’s old radio is kept as a gift from him, its sounds are heard as a sign of his ears toward the world, she explains. He had a liberal and tolerant world view and a belief in a variety of lifestyles, she expresses. The father encouraged Amiri’s reading and steps toward education and independence. In this way, her portrayal defies more crude or stereotypical depictions of patriarchal fathers.

Amiri and her mother’s longings and pasts are demonstrated in events around the arrival of a doll for which Amiri wished at some point during her childhood. Her parents were on the government dole, and the freezer was filled with frozen vegetables bought with state-sponsored child support money. There was rarely money for the toys that other kids had, but her mother kept an eye on the nearby second-hand shop. One day, there was a slightly tired version of a doll in the shop, but it was a real Babyborn. So, she bought it. On the way back, her mum fell and hurt her knee badly. Despite being bruised, she readied the doll, ironing its old clothing. However, Amiri rejected it; it reminded her of her mother’s pain and bruise. But her mother kept it; the mother’s inner child surfaced in her cautious and tender ways of taking care of it. Amiri ends Chapter II, “It told a story of a child that never herself was treated tenderly.”

Amiri, like others in this article, lives and writes herself into a habitually gained ability to maneuver between different forms of vision or second sight. For a resourceful use of second sight, it takes a particular use of masking abilities, and for this discussion I apply the notion of the veil. On the one hand, the veil may be understood here as a visible demarcation of difference, which Amiri negotiates—also without wearing the actual physical veil. There is the sense of being seen as a different color and class. There is also a sense of inequality, not to be recognized as Dane. Finally, there is the third ambiguous second sight developing. In her world of books, she writes, she could be a full human being, not the “not quite Dane or Afghan.” While reading, she could also escape from the difficulties of seeing her brother thrown out from school, or the other girls wearing brands her family could not afford.Footnote16 She depicts a battle with the system and with herself. At the end, she concludes: “Our mirror image reminds us of the scars we try to paint away with success stories.”Footnote17

Rushy Rashid, mentioned as an inspiration by Amiri, became the very first nationwide TV newsreader of a Pakistani Dane ethnic background in 1997. A crucial TV event marked her entry as one of the key examples of an immigrant “speaking back,” which pre-dated her cowritten autobiography. She appeared on a national commercial TV3 debate program, “På tråden, Strings.” Rashid introduces the notion of mutual integration, integration being a term that thus far has targeted immigrants. Here she appears at a young age, calm and in control, despite being harassed by an infamous right-wing politician and an interviewer who interrupts her first words with the question evoking racism in Southern USA half a century ago: “Do we also need to wear scarfs and carry knives?” She responds calmly that not only immigrants bring knives, and people wear hats and all sorts of things, and that the interviewer can wear a scarf if she wants to. She is only given a little time to talk in between viewers’ calls and the politician’s ramble, but at least she is handed the last words. The main problem is unemployment, she says, and what it brings. Her coauthored autobiography came out a few years after this event, in 2003, when she was 34–35, a few years after her first memoir, from 2000. The titles may hold clues. The first is “lifting” or removing the veil, Et løft af sløret, Lifting the veil, engaging with Rashid becoming a public name, and incorporating “Danish” or Western values. The second is called Behind the Veil and tries to incorporate a doubleness in form. The two authors decided to write separately and let the book unfold as a turn-taking often relating to the same events. Some chapters have events only engaged with and written about by one, and views by the other have been incorporated. Where they have written mostly about the same events, it has been with their respective set of green versus brown eyes, as they put it.Footnote18 They only showed their writings to each other when completed. Some names and places have been changed to protect a few friends and family members. Together, they aim at making visible the differences, but in this process, more similarities remain, they argue.Footnote19 The change of perspective is possibly more common in novels and other forms of fiction, yet their approach demonstrates the continuum and development of similarity and difference. Rashid notably continues in journalism and radio work to this day.

Kurdish author, Özlem Cekic, became the first woman of immigrant background in the parliament in 2007. She was, and is also today, often in the spotlight, now mainly working as adviser and freelance debater, running her organization “Bridge builders.” In 2018, three years after she had stepped out of the parliament, she was invited to do a TED talk in New York about what was then a recent initiative of hers: dialogue meetings in which she invited people posting her hate mail to coffee to talk. She published her autobiography, From Føtex to Folketinget, From Tesco to the Parliament, when she was 33 and has most recently published a book on conversations in relation to her dialogue meetings. As with Rashid, Cekic articulates a journey away from her roots but in that very process outward also finding/recognizing her feet, routes, that move around/back. The road to Damascus, as the saying goes, is also an inner journey. In Cekic’s case, she literally moved back and forth between Turkey and Denmark during her childhood and youth.

Sara Omar’s 2017 Dødevaskeren, Death Washer, became a national bestseller and is now translated widely. It paints an unambiguous picture of a Kurdish girl’s violent upbringing. The girl’s grandmother, in the book, is a death washer, a person who cleans girls and women who have been killed in disgrace and whom no one else wants to bury. Omar is Kurdish but fled war in the late 1990s and came to Denmark in 2001 when she was 15. While Omar calls it fiction, there are clear biographical similarities to Omar’s own life, her flight to Denmark as a female Kurdish child. Omar’s secret or reclusive knowledge is based on personal experience, or the experiences of others, This form of unique and pained second sight of protected private matter is used as a resource in her tale as well as her struggle to mourn it. It is also veiled in public appearances and interviews in which she continually emphasizes that she is on a mission to create changes. During 2021, various news media (e.g., a film magazine, a new digital news source, as well as well-known daily newspaper) covered an escalating conflict between Omar and a documentary filmmaker and producer over questions of truth and security matters related to tales of her past, which serve to stigmatize Muslims in general. Omar initially collaborated on the documentary but pulled out, leading to a conflict around rights to the material.Footnote20

Leaving the Concrete Block: Roots and Routes

One of the most controversial male authors of this study, Yahya Hassan, gained immediate recognition with his eponymous debut poetry collection in 2013. He used a poetic depiction of beatings and abuse in his deprived Muslim, Palestinian/Lebanese immigrant family of living in one of Denmark’s so-called “ghettos.”

FIVE KIDS IN A ROW AND A DAD WITH A CLUB

PLURAL CRYING AND A POOL OF PEE

WE TAKE TURNS, STICKING OUT A HAND (2013, 5)Footnote21

Hassan’s collection begins with the poem “CHILDHOOD” and concentrates on grim poetic descriptions characterizing communities most readers had not lived in or heard of. The first section unfolds internal and external splits and conflicts, and often uses a broken Danish, although he was very well versed in Danish literature.

Hassan continues writing poetry after a continued turbulent time, including psychiatric hospitalization, attempts as a politician before drugged driving fines resulted in his dismissal from politics, imprisonment, and activism. His second poetry volume moved more clearly beyond the microsphere of his home community and took Hassan, now an often-guarded celebrity, into other spheres of Denmark and a turbulent journey out of the teens into adulthood. Two collections of straight-talking second sights captured the various spheres he inhabited: publishing, prison, psychiatry, hometown relations, old friends, new acquaintances. His work remained uniquely personal, even as Hassan went public and became a public persona. The public was held behind a veil of what was persona and what was Hassan. The first lines of his second collection may sum up his journey:

LEAVING THE CONCRETE BLOCK

BULLETPROOF VEST IN THE SUMMER HEAT

ON TRACKS TO THE CAPITAL

SUITCASES TWIST MY WRISTS OUT OF JOINT

POLICE LURKING

STRIPPING ME DOWN IN THE PUBLISHER’S WINDOW (2019, 7) Footnote22

“Sort Land,” Black Country, by Ahmad Mahmoud, a soft-spoken, future politician, also made some impact. The poetic and fictional accounts are stitched together in a series of events that mark either a departure from or an ambiguous relationship toward neighborhoods, families, and even gangs to which the author belonged. These accounts can be seen both as a kind of quicksand of the past and as a driving force in his life. As Mahmoud, begins “I grew up in a typical immigrant ghetto—with many kids, Koran schools, gangs, arranged marriages and people on the dole. I moved and got myself an education.”Footnote23 We learn from many incidents in the book what pushed Mahmoud out. In the preface, he appears to make a few statements to avoid generalization or being misread as attacking his relatives. He states, “Most immigrants do not represent this culture.” Also, “I know that many in my family will not like this [book]” and “I love my family and don’t want to harm them.”Footnote24

Nedim Yasar engages with a personal history of gang trouble and the difficulties of achieving what a Danish majority would call ‘integration’. His 2018 book Rødder, “Roots: A Gangster’s Way Out” importantly, and intendedly, uses the Danish word for “roots,” which also means “bullies.” In his use of roots and routes, after Ian Chambers, Paul Gilroy suggests using the notion of crossroads to overcome the dichotomy.Footnote25 In the exploration of transitional identity Yasar and all of the authors examined here reach back and forth between spaces that are restricted or closed and more open spaces, “space constituted by flows.”Footnote26 Yasar’s book received attention also in the UK and US,Footnote27 as Yahya Hassan’s debut five years earlier had made it to the foreign press mostly due to the sad circumstances of the release of his autobiography told to journalist Marie Louise Toksvig. The former gang leader had at first entered an exit program when released from prison and then worked for a few years as a mentor for youth and as a Radio presenter and host, primarily on the program Police Radio (where he also worked with Toksvig). When the book came out, he was shot dead immediately after attending the book launch on 19 November 2018 in Copenhagen. Yasar had been outspoken and critical about the “brotherhoods,” which he tried to prevent youth from entering when working as a mentor and radio presenter. He became a strong advocate for new routes—as Ahmad Mahmoud. Mahmoud was not a gangster, but he was quietly talking against codes and forms of toxic masculinity in his home environment. In Yasar’s case, it was more difficult to escape the “roots”/“bullies,” here understood as a criminal, gangster environment. The code is to leave the gang and stay silent.Footnote28 However, Yasar continued to talk.

In the case of Yasar, but also Mahmoud, Omar, Hassan, Amiri, and Rashid, it is debatable whether or not the material tends to follow a particular track of breaking away from an inherited familial and social structure. The norms of the parents’ culture are exposed and in parts rejected in their writing, “leaving the concrete block,” as Hassan put it (2019).Footnote29 In a literary fashion, they break with veiling, or transform their second sights into a cry for change. Many others do not challenge the veil or just silently adapt. There are few bestsellers that create a contrasting picture of the communities that Yasar, Hassan, and Mahmoud unpack. These texts remain “breaking out” accounts. However, the “how” is not easy or unambiguous. We may say that for the authors mentioned so far, the journey is more of a zigzag, a painful work of making different identifications work as one identity. Importantly, as it is presented in the writing of particularly the women—Amiri and Rashid—it is not a question of roots or routes. It is the negotiation and embrace of both, a rooted heritage, spaces, and objects of symbolic significance together with ambitious journeying into the unknown, or into Danish “normality,” as Yasar has expressed it. Yasar’s auto/biography is stitched together mostly as brief vignettes with specific events reconstructed in a “told-to” format in which author Marie Toxvig reports in third-person. Yasar has provided extensive detail, and there is plenty of shorter quoting. Toxvig and Yasar worked together on the radio program Police Radio, so she had already listened to his stories in another context. Toxvig was also able to use other sources, court proceedings, social workers who knew him well, and so forth. Still, we do not really get a voice from Yasar himself. We sometimes miss the first person, and in this way, it differs from Lagercrantz’s elegant capture of the first-person voice of Zlatan Ibrahimovic, the Swedish footballer with Bosnian and Croatian family roots. Zlatan grew up in one of the rougher areas of Malmö.Footnote30 Still, the Toxvig–Yasar account provides a remarkable, raw account of the workings of specific communities and how difficult it is to break free if you have ended up as a gangster. The first chapter says, “Nedim woke up confused to hammering on the door,” in what is the most recently dated vignette except for an epilogue. We are in 2017 some years after Yasar has been through an exit program. But someone he has forgotten to fight properly is still after him and Yasar does not have a weapon next to him as he used to. A fight at the door is described in all its near-deadly grit.

Some vignettes, such as this one, have added context or reflection based on Toxvig’s talks with Yasar in which he has moved beyond the reconstruction of the scene. In this first vignette, Yasar is living in a new “quiet” place at the other end of greater Copenhagen, and he is hosting radio programs and doing social work, now years ahead of his now-distant gangster past. The book moves back and forth from early youth up to the year before its publication (2018). Yasar grew up with his mother who tried to discipline him with a combination of strong adoration, slaps, and beatings with a baking roll. The mother was briefly also often beaten by the father after arrival in Denmark. The children sometimes tried to protect their Mum, and they got beaten too. In the morning, the bruised Mum would tell her boys, who had bruises too, to say that they had fallen if anyone at school were to mention the marks. The father had come from Kurdish Turkey to Denmark as a refugee. Yasar’s mother, Yasar, and his brother came a few years later through family reunification in 1991. Yasar was 4. When he was 11, he never dreamt of anything else than being a gangster. The father is portrayed as a petty criminal and violent drunk. The mother worked as a cleaner. She was the one trying to keep their lives in order as well. Toksvig quotes Yasar in the introduction. Yasar, dwelling on some of the details of his life and crime, depicted: “I don’t like myself at all when I read this.”Footnote31

Yasar was killed just after a book-launch reception. He chose to talk about his past instead of staying silent and reclusive as most exit or exit program gangsters and decided to do so in public and educational platforms, such as the radio program Police Radio and youth projects at the Red Cross.Footnote32 His educational voice of experience was very important. He wanted to inspire other gang members, he had told his radio colleague.Footnote33 It can be argued that Yasar’s practice and spirit call to mind the educational philosophies of classic thinkers such as John Dewey or Paulo Freire: he was experience-based, social, and dialogically grounded, advocating liberating ideas and practices. Earlier on, during the gangster years, Yasar was navigating a series of veils and fragile alliances: always needing to be alert, becoming paranoid; is this person a threat, etc.; then sneaking out, behind the veil of the exit program—and then in recent years “freed,” but still an identity defined in clear relation to his past; Yasar the former gangster. This new public work lasted only a few years. Most of the literary life writing engaged with in this article takes shape as generative work where the debris of one’s past, the confrontations, and the points of crisis are turned into a writing scene of learning lessons.Footnote34

Fiction and Life Writing as Forethought of Change

The authors (and works) engaged with in this article have been carving out new space, trying to write forward their own terrain, and redressing rituals, neither as breaks with tradition nor recycling. Their guiding stars, whether parents, politicians, historical figures, even a deity, appear to get space here and there in the books; a significant person, in the house, at school at the municipality, someone from memory, or still present.

In the early autobiography by Amiri, the memory of her father is a stable pillar, the Afghan minister and Harvard student in archaeology. However, most of her guides are constantly up for revision. She matures, falls apart, takes up another position to cast another light on a person before being portrayed or interpreted differently, whether a father, mother, or a brother. Interestingly, only some teachers get unambiguous praise, contrary to the account of schooling in the autobiography by Cekic, “interesting you are all trying so hard, but you will never make it,” a teacher had noted.Footnote35 In Amiri’s account, few are safe or in permanent order—Amiri herself least of all. Amiri’s second sight is far from static or settled. She appears to move around the veils, which one can interpret as alluded to in the title Gloss Images. The plural form, gloss images, may indicate repetition or process. One will do it again; gloss oneself up. Amiri is not into gloss. Neither is it a tale of gaining full control or success. She begins her tale by referring to a dream she had in which key family belongings from her early life in Kabul suddenly were found and shipped to the family in Denmark. When she left Kabul as a child, she was fleeing a house fire and realizing that things are replaceable, yet dreaming about the return of the belongings of her lost childhood. She asks how one can replace or return childhood memories indicating they were stolen or disturbed. Her method is difficult, since her work around personal memories and relationships takes place on public radio, stage, and the public scene of writing. This is a common feature in these texts; experiences from the personal back yards and alleys are taken to “main street.” The medium of writing becomes a way of negotiating and representing a relationship between one’s backstage and front stage borrowing from sociologist Erving Goffman and his dramaturgical approach to personal performance.Footnote36 Most of the authors depict various stages of action, the theater metaphors thought applicable for all human beings. Yet for these veil-negotiating individuals in a community-oriented culture, such notions may be particularly useful. In many of the accounts, caring role models or guides appear to provide rootedness or stability to the zigzag or lack of control, where key figures facilitate some degree of stability at a chaotic front stage; a social worker in Yasar’s Roots; A grandfather in Omar’s Death Washer; A father in Amiri’s Gloss Images.

It is neither particular authors nor thinkers that inform their generational battles. It is rather a community or/and a family heritage, sometimes relating to Islam or a particular use or abuse of Islam. Amiri, Cekic, Rashid, Hassan, Omar—and the footballers Nadia Nadim and Zlatan Ibrahimovic (from Malmö, Sweden)—are arguably and conveniently cherished by white mainstream Denmark/Sweden as welcomed rebels who individually broke the patterns of troubling social and cultural practices. For some fractions of Denmark, it appeared to be convenient insider “data.” They could be taken as critical witnesses of Islam and as insiders contributing to a continued trapping of Muslims already produced by the immigrant-hostile far right. There are characters (e.g., the fathers of Hassan and Yasar) easily generalized by the far right. However, all the books are mainly about subjects that move and change. Stereotypes do not move.

Foremost, the writings grapple with the tragedies and emotional luggage of familial networks and history, and, while being highly critical of many individuals in the groups to which the authors belong, they are portrayals of humans and groups made peripheral by the gaze and discourse of a Danish majority culture. Somehow, one might still fear that the attention they received from a white, middle-class majority (although the readership has been much wider) could create this siege or role casting as “immigrant authors,” or “pattern breaker,” and thus complicate an artist’s search for other stories and identities.Footnote37 This role, however, does not do justice to the search inside most of the books debated: There is a sense of work with, or across, divisions in the self/body and in society. Identity politics in the best sense of the term takes a few hundred pages, a prolonged afterthought, or forethought, and not a banner ().

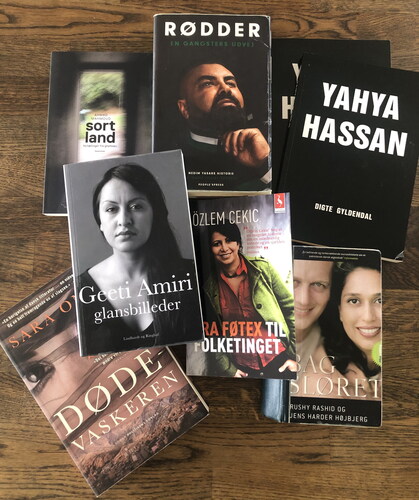

Figure 1. Books discussed: Roots, Black Country, Death Washer, Gloss Images, Behind the Veil, hassan 2 (author’s translation of titles).

In Yasar’s biography, a social worker who never gave up on him appeared to have just influence enough to help Yasar. Yasar’s book, and the works in general, addressed a power game between a few encouraging sources (teachers, social workers, a significant family member, a partner) within the sort of entrapment or siege crippling real navigation forward.

Fortunately, impactful studies in migration and new identities are not just found in the news, social media debates, or academic fields such as sociology. They are increasingly fictionalized and partly documentary, as demonstrated here: novels, poetry, moving images that foreground intergenerational memory, history and socio-historical complexities, and ambiguities that may be helpful in challenging myths and simplistic identity politics. The authors presented here explore a cultural critique addressing both majority and minority cultures (as well as an affection for them). It is difficult for most academic disciplines to adopt a second sight. Is that a form of appropriation, a multimethodology, a triangulation, a new sociological imagination? For Du Bois, literature, music, and experience, including some influences during his stay in Germany, developed into his concept of second sight in The Souls of Black Folk.

In her 2017 biography, Nadia Nadim includes a Dari saying used in Afghanistan, “Do not take the path that the parents are not taking either,” is a saying used in Afghanistan.Footnote38 The range of texts read, which have had my primary focus here, appears very broadly to have one ear wide open to the historical past and the generations before them (parents and grandparents)—but likewise another ear clearly open for the future, probing for change and necessary new paths. There is a tension between the generational History to follow, with a capital “H,” and the personal history, with a small “h,” that can pluralize, hybridize, and take many turns. The books report on that journey of making the subject, one person burdened by histories—as I have tried to capture in the title History in Person. The tension or the clash between histories does not necessarily create generational conflict. And the histories, or collective memories of which we are a part, are never uniform. In fact, they are heterogeneous. It is dangerous when the works or the authors are understood as conveying uniform images of immigrants while they are engaging in a portrayal of very specific communities rather than attempting a wider characterization of immigrants in Denmark.

On a concluding note, Geeti Amiri’s Gloss Images is one of the most impressive and nuanced of the texts. It is a reflective account of a powerful engagement with her parents’/grandparents’ history as well as a dialogue with the disagreements along the way, at an early age. Amiri’s account is particularly strong in its painful and moving inner dialogue and shift in positioning, or ways of seeing the father, the mother, and the brother, and her writerly attempts to heal or reconcile different directional pushes and identifications (being Afghan, diverse family expectations, personal aspirations, love, education, Danishness, religion). Her account may be termed “writerly” (freely appropriating Barthes) by its continuous disruption of meaning or order leaving it to us, the readers, to freely interpret the meaning, which she does arrive at herself before leaving it again for new meaning making. Its nuances of a well-developed style of self-scrutiny and changed positioning toward herself and family are what we are left with. Turning the Dari saying around: To try out roads not taken (by our ancestors) nurtures a hope and possibility for development.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anders Høg Hansen

Anders Høg Hansen has researched popular memory and citizen engagement through art and alternative education in a variety of projects in Israel/Palestine, Tanzania, and Sweden/Denmark. He has an MA and PhD in cultural studies and is a senior lecturer at Malmö University working on the hybrid program Communication for Development.

Notes

1 Two of the authors introduced are recently deceased: Yahya Hassan, a poet, died at home in 2020, while Nedim Yasar was shot in the street in late 2018 after the launch of his autobiographical debut. He had been a gang member until 2012 and had then been in prison followed by an exit program before becoming a radio host and mentor for youths. All other authors engaged with in this article are still alive.

2 Hassan was a teenager (18 years old, born 1995) when his first poetry collection came out in 2013.

3 While focusing on the authors or text’s ability to convey new insights, I am also to a minor extent discussing how the books’ focus on migratory backgrounds and communities can lead to a sense of siege where the author s become framed and appropriated as “immigrant authors” who provide critiques of Islam, Middle Eastern communities, or parental culture, in a process of integration with Denmark.

4 “The veil” is in this usage is not to be confused with the actual garment of the veil worn by many Muslims.

5 Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 10–11.

6 Perkinson, “The Gift/Curse of “Second Sight,” 19.

7 Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 5.

8 Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk; Pittman, “Double Consciousness.”

9 Pittman, “Double Consciousness.”

10 Amiri, Glansbilleder (Gloss Images), chapter VII.

11 Ibid., preface.

12 Ibid., chapter VI.

13 Aagaard, “En kvinde, der følger sit hjerte.”

14 Amiri, Glansbilleder (Gloss Images), chapter I, 5.

15 Ibid., chapter I, 6.

16 Ibid., 229.

17 Ibid., 232.

18 Rashid, Et løft af sløret, 10.

19 Ibid., 9.

20 A documentary has been produced, but its premiere has been postponed indefinitely, December 2023.

21 Translations are mine. Hassan wrote in capital letters only inspired by a few other Danish poets, such as Michael Strunge.

22 Translations are mine.

23 Mahmoud, Sort Land, 9.

24 Ibid., 9–11 (Preface).

25 Gilroy, “It’s a Family Affair,” 93.

26 Ibid.

27 Sørensen, “Reformed Gang Leader in Denmark.”

28 Here understood as a criminal, gangster environment. The code is to leave the gang and stay silent (Sørensen, “Reformed Gang Leader in Denmark”). Yasar, however, continued to talk.

29 Hassan, Yahya Hassan 2, 7.

30 Copenhagen is just 30 minutes away; a bridge connects the two cities across the strait.

31 Toksvig in Yasar, Rødder. En gangsters udvej, 11 (Preface).

32 Ibid., 7 and Richelsen, “Nekrolog.”

33 Richelsen, “Nekrolog.”

34 McAdams, 2005.

35 Cekic, Fra Føtex til Folketinget, 63.

36 Goffman, 1959.

37 Aagaard on Amiri, Glansbilleder (Gloss Images).

38 As told to Miriam Zesler, in Danish, 14. Translation is mine.

Bibliography

- Aagaard, Charlotte. “En kvinde, der følger sit hjerte.” Dagbladet Information, November 8, 2016. Accessed January, 2021. https://www.information.dk/kultur/anmeldelse/2016/11/kvinde-foelger-hjerte

- Amiri, Geeti. Glansbilleder (Gloss Images). Copenhagen: Lindhardt & Ringhof, 2016.

- Björgvinsson, Erling, and Anders Høg Hansen. “Amendments and Frames. The Women Making History Movement and Malmö Migration History.” Crossings: Journal of Migration and Culture 9, no. 2 (2018): 265–287.

- Cekic, Öslem. Fra Føtex til Folketinget. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 2009.

- Christensen, Ann-Dorte, and Sune Q. Jensen. “Roots and Routes. Migration, Belonging, and Everyday Life.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 1, no. 3 (2011): 146–155.

- Court, Louis. “Khalida Popal, Afghanistan Football Pioneer.” 2017. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2017/mar/15/khalida-popal-afghanistan-womens-football-donald-trump

- Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Norton Critical Edition, 1999.

- Ejersbo, Jakob. Revolution. Gyldendal: Copenhagen, 2009.

- Findalen, Emil, Maya Tekeli, Emil Findalen, and Andreas Lund Munk. “Hvad har Sara Omar ikke fortalt?” (What Sara Omar Did Not Tell?). Frihedsbrevet. August 14, 2021. https://frihedsbrevet.dk/hvad-har-sara-omar-ikke-fortalt-2/

- Gilroy, Paul. Small Acts. Thoughts on the Politics of Black Culture. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

- Glissant, Édourad. Poetics of Relation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

- Glover, David. “‘A Different Rhythm’: Stuart Hall’s Du Bois Lectures.” New Formations 96, no. 96 (2019): 237–247.

- Hassan, Yahya. Yahya Hassan. Gyldendal: Copenhagen, 2003.

- Hassan, Yahya. Yahya Hassan 2. Gyldendal: Copenhagen, 2019.

- Hemer, Oscar, Maja Povrzanović Frykman, and Per-Markku Ristilammi, eds. Conviviality at the Crossroads. London: Palgrave, 2020.

- Hirst, William, Jeremy K. Yamashiro, and Alin Coman. “Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 22, no. 5 (2018): 428–451.

- Høg Hansen, Anders. “Erindring og Fortælling (Review of Birgithe Kosovic, Det Dobbelte Land).” Praktiske Grunde, 1 (2011). http://praktiskegrunde.dk/2011/praktiskegrunde(2011-1g)nyhedsbrevet44.pdf.

- Høg Hansen, Anders, and Erling Björgvinsson. “Women Making History,” History Workshop Online, 2018. Accessed March, 2023. https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/womens-history/women-making-history/

- Høg Hansen, Anders. “Footballers and Conductors.” In Conviviality at the Crossroads, edited by Per-Markku Ristilammi, Oscar Hemer, and Maja Povrzanović Frykman, 227–245. London: Palgrave, 2020.

- Ibrahimović, Zlatan. Jag är Zlatan. Min historia. (told to David Lagercrantz), Bonniers, 2011. Accessed October, 2018. http://halsnaes.lokalavisen.dk/nyheder/2018-01-13/Frederik-Germann-%E2%80%9CJeg-flytter-aldrig-fra-Halsn%C3%A6s%E2%80%9D-977008.html

- Kosovic, Birgithe. Det Dobbelte Land. Copenhagen: Politikens forlag, 2010.

- Kristeligt Dagblad. November 9, 2007. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/danmark/nye-stemmer-i-tinget

- Lave, Jean, and D. Holland, eds. History in Person. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 2001.

- Lee Langvad, Maja. Find Holger Danske. Copenhagen: Borgen, 2006.

- Leonard, Peter. “Det etniske gennembrud.” multietnica 31 (2008): 31–33.

- Mahmoud, Ahmad. Sort Land. Copenhagen: People’s Press, 2015.

- McAdams, Dan P. The Redemptive Self. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Michael, Olga. “Graphic Autofiction.” In Autofiction in English, edited by Hywel Dix, 105–124. London: Palgrave, 2018.

- Møller, Kirsten, and Vibeke Blaksteen, eds. Jakob Ejersbos forfatterskab. Et portræt. Århus, Denmark: Filo Press, 2018.

- Nadim, Nadia, and Miriam Tezler. Min historie. Copenhagen: Politikens forlag, 2018.

- Omar, Sara. Dødevaskeren. Copenhagen: Politiken’s forlag, 2017.

- Pape, Morten. Planen Copenhagen: Politikens forlag, 2015.

- Perkinson, Jim. “The Gift/Curse of ‘Second Sight.’” History of Religions 42, no. 1 (2017): 19–58.

- Petersen, Jesper. “Frihed og rollemodeller.” Tidsskrift for Islamforskning 12, no. 1 (2018): 29–54.

- Pittman, John. “Double Consciousness.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2016. (edited 2023). Accessed July, 2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/double-consciousness/

- Praizovic, Lidia. “Klarer Sverige den danska romanen om hederskultur?” Aftonbladet, 12 July 2018. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.aftonbladet.se/kultur/bokrecensioner/a/XwAVlm/klarar-sverige-den-danska-romanen-om-hederskultur

- Rashid, Rushy. Et løft af sløret. Copenhagen: People’s Press, 2000.

- Richelsen, Sebastian. “Nekrolog.” Euroman, November 21, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.euroman.dk/samfund/nekrolog-nedim-yasar

- Sørensen, Martin Selsoe. “Reformed Gang Leader in Denmark Is Shot Dead Leaving Book Party.” New York Times, November 21, 2018. Accessed January 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/21/world/europe/denmark-gang-leader-book-nedim-yasar.html

- Yasar, Nedim. Rødder. En gangsters udvej. Copenhagen: People’s Press, 2018.