ABSTRACT

Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond has been widely acknowledged as one of the most striking and significant debut novels of recent years. While much praised, however, the nature of the novel’s contemporaneity has proved somewhat resistant to elaboration. The present essay offers one such elaboration, following the motif of perspective as it plays its way through Bennett’s narrative. Perspective in its modern conceptualisation is understood not only in relation to the theory and practice of picturing, and as a highly mobile metaphor for cognition and narration, but also as a medium in the sense proposed by the art critic Rosalind E. Krauss. By following the motif, staying close to the novel rather than succumbing to a critical ‘aboveness’ that Bennett herself mistrusts, the working of perspective is shown to be one significant aspect of Pond’s contemporaneity. On this basis, an interpretative link is made between Bennett’s novel and what has come to be known as a post-critical orientation.

The necessary outlook

In ‘Words Escape Me’, the antepenultimate section of Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond, something falls down the chimney of a cottage on the west coast of Ireland. Pond’s unnamed narrator, the temporary tenant of the cottage, senses the arrival of a ‘small thing, and sharp maybe’, present briefly in the room before apparently being ‘withdrawn . . . from all visible possibility’.Footnote1 A ‘thumping’ sound follows soon after, by which time the narrator finds herself ‘quite unable to focus’, as if her eyes ‘had no prior experience of form and perspective. They just slid around, nothing was organized – it was difficult then to locate where I was, for the reason that I just wasn’t able to establish any stable coordinates’ (p. 151).

The fleeting event is one of several scenes in Pond in which the possibility of knowing something is figured in visual terms as being a matter of perspective: an organising coordination of proximity, scale and relation. Outlook, says the narrator, employing the conventional portmanteau term for the mutual conjunction of visual and cognitive perception; ‘outlook’ is ‘everything’, ‘because without an outlook there is, obviously, no point of view’ (p. 172); and point of view, so it seems, is required in order ‘for anything to mean anything’. The everything that is outlook would thus appear to be a, if not the, way of acquiring ‘stable coordinates’ of relation: coordinates of distance, height and depth. Having located herself on ‘the most westerly point’ of Ireland, however, and being mostly alone, the narrator finds it ‘practically impossible . . . to gauge distance’ (p. 92, p. 38), hence the chimney incident as one during which a ‘something’ appearing in the visual field, as that event is accounted for by its witness, does not in any straightforwardly articulable sense come to ‘mean anything’. And yet while the conventional desirability of stable coordinates is acknowledged, the narrator herself, in so far as the reader can tell from her tone, appears sanguine regarding the condition of her own perspectival comings and goings, and with her self-declared neglect, however unwilled, of the ‘necessary outlook’.

A feeling of not-knowing such as that prompted by the chimney-thing is one of Pond’s signature affective registers, for narrator and reader alike. ‘I’m not sure what now is about’, admits the narratorial voice, thereby allaying the anxiety of those readers who have found themselves similarly uncertain of bringing such a singular narration into interpretive focus (p. 25). As Brian Dillon says of initial responses to the novel:

Pond’s reviewers didn’t quite know what to do with [Bennett’s] voice and style, or with the structural or semantic risks that mark some of the more extreme stories. She has somewhat misleadingly been set alongside Eimear McBride as representative of a modernist turn among young writers in Ireland, especially women writers. Misleadingly, not because they don’t share something — a commitment to voice, a syntax that is speedy, bristling and strange at first encounter — but because they sound so different.Footnote2

The publication of a second novel, Checkout 19, has further substantiated the case for Bennett as being one of the most distinctive of contemporary fictional prose voices. In quite what that distinctive something consists, however, seems still to be decided, except in so far as admitting to not knowing quite what to do with a newly appearing voice and style – to borrow Dillon’s summary characterisation of responses to Pond – is already to identify an aspect of character. To an extent, this is simply the signal identifying feature of the authentically contemporary art work per se; that is, ‘a certain failure of our capacity to frame or picture it’: the prompting of an antecedent condition of not-knowing ‘before we can find a way of seeing … a means of fashioning a perspective in which [the work] can come to some kind of fixed relation’.Footnote3 Peter Boxall, quoted here, identifies the familiar conventions of a ‘perspectival dynamics’ at work in figurings and theorizations of ‘what now is about’ (to quote again Bennett’s narrator) – the particular now in question for Boxall being contemporary fiction – hence the figural framing, picturing and seeing of his account.Footnote4 Precisely this imaginary is evident in the description of Pond’s chimney object: the event of contemporaneity itself as a frustration or lack of perspective; of those ‘fixed relation(s)’ produced by means of ‘a way of seeing’, what Bennett’s narrator calls, respectively, ‘stable coordinates’ and ‘outlook’. These and other similar remarks, together with the incidents that provoke them, are not supplemental to the novel’s substance, akin to its reality effect; rather, they are that substance. Indeed, Pond’s distinction, so I hope to suggest, lies in part in its preoccupation with perspective understood as a way of accounting for an everyday experience that is the contemporary. To borrow an art-historical term, Pond is characterised by a rhetoric of perspective: in the more immediate sense of a repertoire of figures, hence in the workings of perspectival rhetoric beyond the visual – perspective as ‘symbolic form’; and in the figurings according to whose naturalised arrangements the visual is brought into view.Footnote5

I begin the present essay with an elaboration of this signal element of Bennett’s novel, moving thence to mark a difference in inflection between Pond’s perspectival rhetoric and that rhetoric as it appears in two of the exemplary works of postmodernism. Pond’s sustained attention to and affective inhabitation of perspective and its correlates – inter alia, scale, relation, distance, proximity, depth, proportion, outlook, prospect and point of view – is in telling contradistinction to the broadly paranoid and critiquing attitude characteristic of a significant strand of postmodernist fiction. Bennett’s narrator appears carefully and inventively indifferent to inherited conventions of scale and fixity, and so to any resulting imbalances of seeing and seen. She prefers instead a felicitous acknowledgement of the processes of the framing and focussing of a visual field as a kind of repertoire of means for thinking and making – a medium, as I suggest here, following the rehabilitation of that term in the work of the art critic Rosalind E. Krauss. As such, Bennett’s auto-narration in Pond, as it accounts for its self-made environment, is oriented in the manner of the post-critic, or of post-critique (to use the shorthand term), the latter being the signal critical mode roughly contemporary with the novel. My concluding suggestion is thus of Pond’s performative occupancy of perspective-as-medium as a distinguishing mark of its contemporaneity.Footnote6

The window figure

Pond’s inaugural image is of the windows of a house – specifically, and pointedly, ‘the principal windows of your house’ – as viewed from outside, from which vantage point they appear ‘perfectly positioned to display a blazing reflection of sunset’ (p. 13). While the suggestion is of a second-person addressee and owner, the viewers are a trio of ‘little girls … on the cusp of female individuation’ who appear to have trespassed on the grounds of the property. The narrator scales the wall of an ‘ornamental garden’ and falls asleep on the grass ‘wrapped about a lilac seashell’.

It is a striking preface suggestive of a playfully sly occupancy of secured grounds. Its motifs look forward to aspects of the account to come and back to the novel’s epigraphic material: Nietzsche on a ‘wistful lament’ for our ‘decomposition into separate individuals’; Ginzburg on rooms as benign burrows; Bachelard on wolves in shells; and ‘The Orchard of our Mothers’, a woodcut by the contemporary Irish artist Alice Maher depicting a group of peacefully sleeping female figures attached by their long hair to a series of holes in the ground (the inclusion of the woodcut as epigraph is a preparatory sign of Pond’s visual orientation). The gendering, both of the preface and of the Maher image, hints at something quietly oppositional. This is corroborated by the inaugural play on classical perspective. The introductory window through which the reader enters Pond appears not as a means of access to a natural scene such as linear perspective might present, but as a mirror showing a ‘blazing reflection’. Bennett here unites in one image the two primary signifiers of classical single-point perspective in the European tradition, as technology and figure respectively: the open window of Alberti’s De Pictura (1435), generally considered to be the first codification of the theory and practice of what has come to be known as linear perspective; and, a little earlier than Alberti, the mirror used experimentally by Brunelleschi in his perspectival demonstration drawings of the Baptistery of Saint John in Florence. The window in Alberti’s now famous instruction –

First I trace as large a quadrangle as I wish, with right angles, on the surface to be painted; in this place, it [the rectangular quadrangle] certainly functions for me as an open window through which the historia is observed[;]Footnote7

Bennett plays a series of subtle variations on the constituent aspects of the conventional window figure over the course of Pond, with explicit or implicit reference each time to the possibility, or else the apparent disdaining, of outlook and its systematised arrangements. The mirrored window of the opening scene – the ‘blazing reflection’ of those ‘principal windows’ – is matched symmetrically on the final page by a ‘windowpane’ described as having ‘flinched beneath its white sash’, as if the material means by which viewpoint is constituted, centred and naturalised has become animate. Elsewhere, outlook as signified by the window figure is quietly interrupted through the breaching of the framed border between outside and in, and by a frustration of relations. In the short section titled ‘To a God Unknown’, the narrator sits in a bath beneath a ‘thoroughly square window’ the pane of which is ‘pushed right back against the wall’. Where the opening window figure reverses a framed prospect of landscape, here the naturalising frame of an observed outside is breached. A leaf falls through the window and lands in the narrator’s bath. Without moving, she feels ‘as if . . . in the coniferous tree that continued upwards’ outside (65; emphasis added). While the continuousness and continuity of extension in space is one of the primary effects of linear perspective, the given relation of viewer and viewed on which such effects are based is here contravened. The narrator is ‘immersed in the body of the storm’ – ‘its structure . . . its eyes’ – as the rain enters ‘in slants through the wide-open window’ (p. 66). Immersion or entanglement are indeed part of this narrator’s repertoire of experiences. She periodically longs to be, or imagines herself as being, down in the soil or up in the air: ‘Standing at the back window, looking at the lawn, and knowing exactly everything beneath it and wanting to get back there’ (p. 140). While such fantasies of immersion are not always accompanied by the window figure, its motivic presence suggests a way of conceiving them at the level of structure and orientation. The framing motif acts as the means by which a series of conventions are invoked, brought into play in the manner of an informal and ambiently occurring experiment in perception.

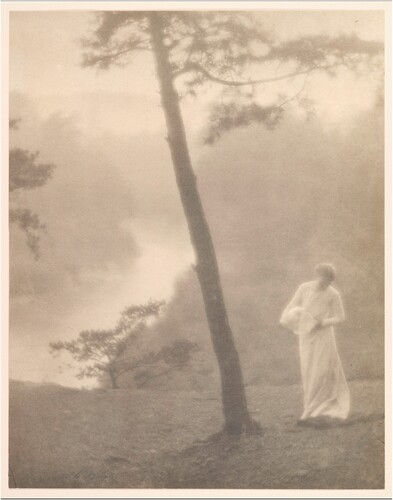

The closest Bennett comes in Pond to acknowledging the lineage of the window figure and single-point perspective is in ‘Morning, 1908’, a section towards the end of the novel. The title is taken from a print (‘Morning, 1905’) by the American photographer Clarence H. White, a book of whose images the narrator is ‘skimming through’ at the section’s end (p. 128). Such specificities of person and artefact are relatively rare in the novel, Bennett’s narrator being far more interested in the affective atmospheres of her immediate domestic situation than in the unloading and display of cultural baggage. White was a chief advocate and proponent of Pictorialism, a short-lived pre-modernist genre of photography characterised by a rather self-conscious aspiration to the condition of painting; a condition achieved via various technical and hand-crafted means. ‘Morning, 1905’ shows a countryside scene recognisable as such in part in its conforming with certain of the representational conventions that comprise the pictorial genre of landscape painting ().

Figure 1. Clarence H. White, ‘Morning, 1905’, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence.

The visual field is offered as if to the fixed eye of a viewer able thus to survey a scene which has the requisite depth and internal relations. Fore- middle- and background are clearly delineated, the viewing eye being led from one to the other and back again by the passage of a river as if ‘into’ the space. This river, as the horizontal line that makes and marks the space, is framed as per the convention by the corresponding vertical lines of a number of trees. Where the former takes on the reflective light of a sky thus implied, the latter frame as much by their comparative darkness as by their height. The apparent naturalness of the scene is an effect of a long-naturalised technique and its invisible means. A visual doubleness is at play in the painterly effects of White’s construction, in the brushy soft focus in particular, simultaneously pointing to the image’s constructedness and disavowing artifice as those effects work to achieve the naturalised realism of landscape painting.

A crystal globe held by the figure in the foreground is the most obviously defamiliarizing element in the image, but the landscape itself, as landscape, is more fundamentally estranged by the tree next to which stands the figure.Footnote9 The long trunk of the tree (it is one or other type of pine, perhaps), denuded of branches except towards its upper part, is rooted just to the right of the middle in the levelled foreground. It leans upwards to the left in counterpoint to the figure as she turns gently away to the right. The base of the tree is close to the picture plane but the trunk reaches past the upper frame of the image – ‘the tension between the aerial and the subterranean is . . . palpable’, as Bennett’s narrator says of one of Pond’s window-framed trees (p. 152). Positioned as it is, the tree simply but strikingly bisects the organised space of the landscape. In so doing, it interrupts perspective and its objects as they work to establish an inside space behind and inside the window of the framed image. The fact of the interruption’s being a tree is ironic given the structurally framing function accorded to trees by the conventions of the genre. As if in acknowledgement of White’s interruptive figure, the narrator makes passing reference in ‘Morning, 1908’ to her present atmosphere as being ‘intersected by a vertical and rather searing sense of abnegation’ (p. 128; emphasis added). Indeed, the extraordinary drama of this section, in which the narrator, ‘dissolute and available’ (p. 127) as she walks alone in the landscape, acknowledges the risk of her own ‘twisted longing’ as part of ‘some sort of nebulous external design’ (p. 121). This quietly intense scenario seems as though written after the image (as ekphrasis), or as framed by it.

This figure of an interrupted depth, as image and conceit, appears most resonantly in Bennett’s titular object. The canonically presiding literary ponds, those at Walden, are resonantly profound: Walden Pond is ‘a clear and deep green well’, prompting and amply accommodating descriptive reflections on surfaces, beds and inhabitants.Footnote10 In deadpan contrast, Bennett’s pond has ‘absolutely no depth whatsoever’ (p. 40). Pond itself courts a kind of metaphorical shallowness in its refusal of those gendered consistencies of form and style that tend conventionally to signify profundity and thereby the accrual of artistic value; in fact, the narrator dismisses the very analogising move by which depth comes to signify significance: ‘I don’t want to be in the business of turning things into other things’, she says, batting away the serial possibilities of metaphor (pp. 164–65). Pond’s pond, in being shallow, frustrates the incorporation of its stuff in orderly relation, for stuff and reader alike. Its constituent objects, as a discontinuous rather than conventionally well-proportioned series, bulge out of the prose that makes them, just like the ‘broken, precious thing’ ‘wedged . . . horribly visible’ in the pond after having been thrown there by the narrator. Again, something – variously broken, precious, small, sharp – appears in the visual field without becoming thereby a thing ordered and settled in relation to other such ordered things: placed, measured and counted (and so potentially something other than what it has appeared as) according to a centring gaze.

As demonstrated in these vignettes, Pond’s working of perspective and its scales suggests a transvaluation of shallowness and depth, in themselves and as metaphors in the tradition (not that metaphor is the desired mode in the first place). Hence, for example, the narrator’s avowed lack of interest in ‘inventorial reflection’, whether her own or that of another: ‘people who are hell-bent on getting to the bottom of you are not the sort you want around’ (p. 74). Getting to the bottom of people, because people are deep – personhood being conceived as synonymous with the characterological depth required of Forsterian roundness – is one at least of the ambitions of the novel as form, but it is not one embraced by Bennett. And yet a straightforwardly transvalued or critical shallowness of vision such as we might find in Nathalie Sarraute or Italo Calvino, while evident, does not quite catch as a description of Pond. Simply to transvalue shallowness and its correlates is to remain caught within the inherited strictures of a rhetoric of perspective whose workings, while interestedly acknowledged, have been loosened. Bennett’s shallows, like the broken thing wedged in the pond, are more resolutely frustrating of the fixings of scale, including those scales of significance whereby a reader is encouraged to adjudicate a text’s interests.

Perspective and critique

The sustained working of an imaginary derived from the rhetoric of classical perspective is thus one of the signature motivic elements of Pond. This is significant not only for any account of the novel’s much remarked, but not necessarily substantiated, character, but also because the particular manner of Bennett’s working stands in telling contrast to that imaginary as it appears in a number of the major novels of the generation preceding hers – in postmodernist fiction, that is, in so far as that fiction has as one of its preoccupations a critique of the epistemology of historical record. Linda Hutcheon’s ‘historiographic metafiction’ remains the most useful catch-all term for those texts as they are characterised by a strategic foregrounding of the textuality of history and concern for the constitutive role of fiction in history’s archive.Footnote11 As well as intervening in specific historical moments, with that now familiar blend of period texture and self-reflexivity, novels of this kind are concerned more broadly with the mechanisms by which historical knowledge comes to be made present, hence the much-remarked cross-over between such fictions and contemporaneous critiques of conventional historiography, especially regarding the long-naturalized ideologies of narrative.

The two instances I have chosen by way of illustration are taken from the quieter, more ruminative end of the spectrum of postmodernist fiction. While undoubtedly less baroque than the likes of Angela Carter, A.S. Byatt, Salman Rushdie or Robert Coover, and certainly less ludic, each exemplifies a sustained first-person concern for the representational dynamics of historical knowledge such as characterises a significant strand of the writing of this mode. The first, W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, turns repeatedly to the matter of viewpoint and angle of vision, and particularly to height and vantage point. When considered as metaphor, elevation is seen either to be benign: in the writing of Thomas Browne, for example, for whom, ‘rising higher and higher through the circles of his spiralling prose’, ‘The greater the distance, the clearer the view: one sees the tiniest details with the utmost clarity’;Footnote12 or, as with the view from an aeroplane, to be instructive: ‘If we view ourselves from a great height, it is frightening to realize how little we know about our species’.Footnote13 More usually, however, and specifically in relation to visual representation, distance of view is associated with forms of artful deceit. The ‘bird’s eye view’ necessary for the classically perspectival landscape painting of Jacob van Ruisdael is described as ‘imaginary’: ‘The truth is of course that Ruisdael did not take up a position on the dunes in order to paint’.Footnote14 In one scene, the narrator recalls visiting the Waterloo Panorama. Signs of Sebaldian detachment and haziness – a ‘bleak field’, a ‘leaden-grey day’, the now forgotten motivation for visiting – serve as the frame to draw out the scene presented; or rather, the scene-within-a-scene: ‘the Waterloo Panorama, housed in an immense domed rotunda, where from a raised platform in the middle one can view the battle . . . in every direction. It is like being at the centre of events’.Footnote15 The scene is represented so as to make of the spectator its origin and overseer:

This then, I thought, as I looked round about me, is the representation of history. It requires a falsification of perspective. We, the survivors, see everything from above, see everything at once, and still we do not know how it is.Footnote16

Kazuo Ishiguro’s A Pale View of Hills, another novel written in the shadow of the traumas of the Second World War, is equally anxious about the effects of a conventional perspectival imaginary on the framing and fixing of historical record. While less overt in its critique than Sebald, Ishiguro works a similar set of motifs using a subtly variational technique. The basic motifs are introduced in the first of three carefully modulated scenes. Etsuko, the narrator, looking back on her life in Nagasaki following the end of the War, recalls a visit to ride on a cable car at Mount Inasa with her friend, Sachiko, and Mariko, Sachiko’s daughter. Etsuko marks approvingly the various signs of post-War reconstruction – the fraught legacy of the War, personally and nationally, is the novel’s chief subject – but her account is drawn as if symptomatically to aspects of distance and focus. To begin, the trio sit ‘mesmerized by the sight of the cable-cars climbing and falling; one car would go rising away into the trees, gradually turning into a small dot against the sky, while its companion came lower, growing larger’.Footnote18 Prompted by the view, Etsuko buys a pair of ‘plastic binoculars’ for Mariko. There follows a strangely tense ride up to the viewing area in a cable car shared with two women and a young boy. The gift causes a minor squabble between the children, with Mariko being disinclined to share. The metaphor is clear – ownership and reconstruction are a troubling and contested affair – but as always in the novel, the minor details are the most telling. Three times Etsuko refers to the binoculars as ‘just a toy’, downplaying her generosity, but also as if feeling a need to signal the artificiality of the device in its manipulation of proximity and relation: in effect, its erasure of distance.

The perspectival motifs appear again in a second recalled visit, this time to the ‘peace memorial’ in the city. Etsuko is travelling now with her father-in-law. Where the cable-car scene is framed with reference to post-War reconstruction, here the War is the subject of memorialisation, as figured by ‘a massive white statue in memory of those killed by the atomic bomb’.Footnote19 And as with the former scene, Etsuko’s account is subtly sceptical about, or rather undermining of, the workings of scale: here, the symbolic manipulation of size. Rather than feel awed or respectful, Etsuko finds the appearance of the memorial ‘cumbersome’: ‘Seen from a distance, the figure looked almost comical, resembling a policeman conducting traffic’.Footnote20 Her father-in-law, standing with her ‘fifty yards or so from the monument’, holds up a postcard of the statue and remarks: ‘“It doesn’t look so impressive in a picture”’.

A postcard figures also in the final of the three scenes of viewing, set this time in the present-day of the novel, in England, where Natsumi now lives. Natsumi’s daughter, Niki, asks her mother for a photo or ‘‘‘old postcard’’’ showing Nagasaki, for a friend writing a poem about Natsumi. Once again, a link is made between the motif of remembrance and matters of vision, representation and scale; and again, it is made by Natsumi’s quiet questioning, here, of Niki’s off-hand suggestion that the old postcard might show her poet friend ‘‘‘what everything was like’’’: ‘‘‘Well, Niki’’’, Natsumi replies, ‘‘‘I’m not so sure. It has to show what everything was like, does it?’’’.Footnote21

Natsumi’s everything is the same as Sebald’s in the panorama. It is the overviewing everything that perspective presents to us and makes as if ever-present. In being everything it effaces our own position as centred spectator by hiding from view the mechanisms by which its ordering and totalising vision is made possible: its scaling of relations and fixing of space. The resistingly sceptical or paranoid viewer is thus occupied precisely with the unveiling of perspective as a mechanism; with making visible the naturalising means by which a scene appears and is recognised as such by a viewer thus constituted. Rather than conceive of perspectival framing as a neutral act of showing or making-seen, it is here figured as one of erasure.

Stones and tapestries

Pond’s first-person orientation to history and historical experience is in one sense consonant with that of its precursor novels. Contemplating the prospect of a local memorial event, Bennett’s narrator declares herself to be at odds with all such archival impulses: ‘it makes me wild with anger, to hear the ways the past is thought about and made present. Enforced remembrance is, I think, a most stultifying thing’ (p. 46). The stress placed on the making present of the past as being a matter of method – ’the ways the past is thought about’ (my emphasis) – echoes the postmodernist critique of historicist perspectivism. As justification for her disapproval, however, Bennett’s narrator invokes again the fact of her being alone, to which circumstance she attributes an inability ‘to gauge distance’: ‘perhaps for that reason, I haven’t acquired a particularly distinct sense of the past’ (p. 46). Historical memorialisation, as requiring this ‘distinct sense’, appears dependant conceptually on the establishment of those clear separations constitutive of temporal distance, hence of the rationalising effect of spatialisation. The narrator’s resistance to such effects is certainly related in kind to the critique of the ‘falsification of perspective’ described by Sebald; and yet Bennett proceeds to describe a relation to the historical altogether more distinctively individual than this position would suggest, as demonstrated with reference to the historical record of the rented cottage (which is to be included in the aforementioned memorial event). For the narrator, the ‘large-scale changes’ to the building hold no interest (p. 47); it is instead ‘the small things . . . which sort of attracted [her]’: ‘incongruously compact’ things such as the stones of the building; specifically, those ‘around the back of the cottage, up high on the left-hand side of the wall’. They present a ‘structural anomaly’ in the fabric of the cottage; not a ‘flaw’ as such, rather an anomaly disturbing to the viewer for its ‘errant poignancy’ (anomaly is a particularly telling noun in its etymological indication of something precisely not even; not at one with). The ‘close-knit arrangements here and there of smaller stones’ have an appearance akin to ‘the smaller fainter constellations’ of the night sky (p. 49). Each is ‘in’ but not ‘of’ their respective material context. The analogy takes a somewhat fatalistic, even deconstructionist turn tonally reminiscent of Sebald – ’every monument clenches the very element that will, eventually, overthrow it’ (p. 50) – but the structural position remains as punctum: the patch of stone-work as being ‘in amongst the other stones . . . but . . . not quite of them’ (p. 49).

Classical perspectival rhetoric informs these observations. Rather than the ‘distinct’ gauging of distance according to which logic material or historical event is arranged and brought into focus for a viewer thus constituted, with a whole made of now integrated parts, the narrator is drawn to what disrupts the workings of proportion: to the ‘arresting convergence’, the ‘structural anomaly’. And rather than a continuity of space – spatial or temporal extension – such that viewer and viewed are fixed and settled in relation one to other, the objects here are animate: ‘sort of active’ (48), hence the passing reference to history as that which ‘still exists’ (p. 46). Nevertheless, critique is not the dominant note here. Bennett’s narrator is a visitor to the west of Ireland with no claim on national or local history: whether ancestral, as in Ishiguro, or associative, as in Sebald and many other of the European novelist-historians of the late twentieth century. She herself acknowledges the absence of ‘socio-historical affinity’ (p. 93) as a ‘blankness’: ‘You have no stories to narrate . . . no narrative to inherit . . . and all the names are strange ones’ (p. 97). Blankness, perhaps counter-intuitively, is equated not with distance, however, or detachment, but with a visceral vulnerability to the ‘full force’ of history. The Great Famine is the named historical event, marked as trauma specifically in terms of a dissolution of human matter: of ‘stricken bodies’ left with ‘no form really, no flesh at all’. Her blank vulnerability to history’s dissolvingly animating forces, described in terms of a merging with the earth, produces in the narrator a counterpart experience of upward velocity: a force that comes ‘right through the softly padding soles of your feet, battering up through your body […] Opening out at last: out, out, out’, thence on into the ‘flat defenceless sky’ (p. 98). A perspectival imaginary is again evoked, this time in terms of verticality rather than depth and distance; and again, the character of the account is that of an inhabited errancy and anomaly rather than of spatialised arrangements and proportionate relations. Similarly, there is a notable absence of the metaphorical distance required for critique and its attendant uncoverings.

The small stones of the narrator’s cottage – to return to the specific material figurings of perspective in the novel – have an anamorphic quality, as if the naturalised arrangements of perspective have been dislodged and decentred. These anomalous stones, both as textual object in Pond itself and as materials in the represented environment, are similar in their description to the pair of Japanese tapestries that make an appearance early in the novel. The narrator awaits their delivery to the cottage; thinking back to what she remembers of them, she wonders if indeed they qualify for the classificatory name she has used (the fixity of names being something else she tends to resist or decline): ‘they aren’t much more than two pieces of old black cloth in two separate frames with some rose-gold flecks here and there, amounting, in one, to a pair of hands, and to a rather forlorn profile in the other’. She speculates at first that ‘most of the stitches’ have been removed, leaving only ‘very small holes’, traces of where ‘silken thread . . . moved deftly in and out of the cloth’ (p. 26). The rather forlorn ekphrasis on an absent object once seen and now anticipated does not, however, yield a Sebaldian reverie on commerce, matter and decay (p. 29). The decorative screens duly appear (their status as ornamental is significant given the conventionally gendered belittlement of the ornamental and, by association with ornament, the descriptive. Pond may shun tropes, but it is rich in figures); they appear, but as viewed again, turn out not to be as remembered. Instead of finding ‘framed fragments’, the narrator decides that what she sees is what there is: ‘Nothing had been undone; there hasn’t ever been more than this’ (p. 30). The makers had not ‘remove[d] stitches’: they had ‘simply stopped what they were doing’. ‘Just this, just these few details showed enough’, in much the same way as the ‘structural anomaly of the cottage stones’ is noted by the narrator precisely as not having ‘the appearance of a flaw’. Melancholy is duly averted – not that melancholy was ever really on the cards, except perhaps by way of readerly expectation – and with it the reflective existential depths of distance. In its place is a comparatively welcoming acknowledgement of what has been given as all that there is, hence as sufficient – with one proviso: while ‘[t]hey are close to one another’, the two panels are ‘not exactly side by side: they are related but they aren’t a pair’. Their Louise Bourgeois-like relation one to the other, in being unsettled, remains thus unnamed and open.

The passage serves well as a description of Pond’s own ‘incongruously compact’ self: the apparent anomalies and mis-shapes of its form, the correspondence of the constituent parts, the shifts of tone. The representation of each object, of tapestry and stones respectively, turns on scale and relation specifically in so far as they allow for the identification of smallness, so for the marking of whatever has prompted notice but which does not settle and so order relations amongst its objects; hence the performatively ‘seditious force’ or ‘errant poignancy’ of each visual scene and of the unpaired relation in the text of one to the other. Early in the novel the narrator recounts having been invited to give an academic paper based on an ultimately abandoned PhD project. She describes her interest in the subject – ‘the essential brutality of love’ – as being ‘too personal’, and specifically dismisses her ‘perspective’ as ‘rather naïve’ (p. 20). As with so much else in Pond, the winningly self-deprecating tone of the confession might encourage a reader to pass too quickly on, thereby missing the singular motivic work of the writing. Regarding literary-critical perspective, the charge of naivete is explained in terms of the narrator’s ignoring of ‘the usual critical frameworks’ (p. 20); and yet as I am suggesting here, attending to the perspectival rhetoric of her own auto-narration shows rather that the inherited critical frameworks of the ‘necessary outlook’, including the window-esque figure of the framework itself, are actively and consistently informing of the fabric of the writing – not by way of critique, however, in the manner identified as the postmodernist orientation, nor straightforwardly as a set of figures there for the turning. Something different is happening; something integral to the signature character and effect of the novel.

Perspective as medium

The perspectival imaginary of Pond, at those moments in the auto-narration when it appears to constitute the visual and relational field (or to reflect on such), is in fact strikingly suggestive of what we might today recognise as a post-critical orientation. The voice in these passages tends not to be positioned as surveying a field of objects and relations behind or underneath which signification is sought – to use the conventional figural terms according to which the symptomatic reading is said to operate; nor does it exhibit its perspectival workings self-reflexively in the manner of a metafictional anatomising. Rather, the motivic stress on a perspectival rhetoric ‘causes the world [of the novel] to come into view in a certain way’, to quote Rita Felski on the workings of mood in reparative reading.Footnote22 Perspective as it is enacted in the novel is precisely this coming into view, the ‘certain way’ by which the narration conjures what there is to see and how it might be seen. It is a way characterised by an avowed attachment to what is as if given to vision – passing acts of vision the reader witnesses in the making – rather than to what a normative outlook makes it possible to reveal or decode. Hence an attraction to surfaces and to the adequacy of what is to hand. ‘The outside after all must be right there beside me’: this is the signature disposition of our narrator as she is absorbed in her scene and its objects. As such, Pond, as a contemporary novel, offers to its readers the same opportunities as those identified by Cara L. Lewis in her account of the post-criticality of Ali Smith’s How to be both; that is, a set of ‘other kinds of looking’ – other than Bennett’s ‘necessary outlook’; even, perhaps, what Lewis calls a ‘new optic’, albeit less a case here of novelty as such than of the inventive occupancy of a repertoire of figures and their attendant affordances, what Lewis, in a different context, calls a ‘constantly shifting epistemology of vision’.Footnote23

And so how, specifically, should we conceive this other kind of looking, beyond its self-confirming co-option as an instance of the much-fabled post-critical mode? What element of contemporary fiction might this be? One possible conception is prompted in part by Bennett’s interest in visual art, painting especially; her writing on the subject, most obviously, but also the ways in which Pond itself feels to be informed by, for example, European traditions of still life and landscape painting, and by ekphrasis as a mode of non-paragonic verbal response to a visual stimulus.Footnote24 The term I wish to borrow here is medium: the idea of medium specificity, especially as that idea has been re-conceived for visual art by Rosalind E. Krauss.Footnote25 Krauss begins with the modernist inheritance of the historical conception and separation of the arts according to their respective material properties such that the proper practice of painting, sculpture and so forth is at once constituted, determined and conceptualised according to essential materialities or supports. The flatness of the painted canvas has become synonymous with the proposition. Medium specificity, as employed interpretively by Clement Greenberg in the twentieth century, was a forceful means of accounting for and normatively judging developments in post-war artistic practice in so far as those developments were taken to realise and make manifest inherent and essential material properties of their respective media. (Greenberg in fact came to conceive a dematerialised perceptual experience – aspects of spatiality, for example – as ultimately defining of the medium specificity of individual art forms.) Influential as were such ideas, however, the history of practice soon moved on and elsewhere, in part via a critique, whether implied or stated, of the essentialism, positivism and literalism of the classical conception of medium specificity; an idea that appears now largely as a bounded and identifiable tradition of thought rather than any kind of ahistorical truth.

Krauss’s critique of medium specificity is formed in questioning response to Greenberg and company, but also and more tellingly in reaction to late twentieth-century visual practice as expressive of what she calls a ‘post-medium condition’: fully and contingently multi-medial in material terms and wholly at odds with any essentialism of technique or object.Footnote26 In short, Krauss is sceptical of claims made for the finalised obsolescence of medium; claims that are taken to follow as a logical consequence of a critique of medium specificity. Like Michael Fried and Stanley Cavell, albeit each rather differently, Krauss wishes to retain something of the concept of medium as a means of understanding individual contemporary practices, and, more broadly, of being able coherently and generatively to conceptualise the distinctive aesthetic qualities of contemporary art. Central to Krauss’s version of a revised notion of medium is the idea of the rule, adapted from Cavell, and of recursivity, hence of a cultural and personal dialectic of ‘memory versus forgetting’ that Krauss proposes as fundamental to medium as a means of aesthetic continuance and renewal.Footnote27 The defining difference, however, is that rather than have medium understood as a finite and unchanging set of essential, and essentially self-referring, material properties and attributes, it instead becomes open to invention: potentially, to manifestation in any aspect of the artwork as a condition of possibility for a particular practice and a way of understanding, including the understanding of relations between medium and tradition, and between art and world. Krauss offers a series of examples, perhaps the most immediately graspable of which is Ed Ruscha’s extensive use of images of the American automobile. The immanent but not essentialised properties of the automobile, as ‘discovered’ in practice, become the rules that support the newly invented medium: for the car, such recursive and historically resonant elements as objecthood, iconography, mobility, materiality, seriality, mythography, infrastructure, and so on.Footnote28

Inadequate as is this summary, it serves hopefully as sufficient frame for the present proposal: that the rhetoric and attendant structurings of classical perspective as invoked variously throughout Pond might be understood specifically after Krauss: as a medium, or as medium-like; and further, that Bennett’s recursive working of aspects of this medium is a distinguishing feature of the contemporaneity of the writing. Regarding the former – perspective invented as quasi-medium – it is in the novel more than mere motif. It is, rather, actively and repeatedly acknowledged by the narrator as a matter of seeing and making seen, including narratorially and historiographically, and from there, as a mode of sense-making. Regarding the latter – the contemporaneity of the novel – perspective as employed by Bennett can be distinguished from, on the one hand, the structural critique of postmodernism, according to which mode the organising perspectival rhetoric of the archive is complicit with the violence of history; and on the other, from a localising and relativising perspectivism that would be one reaction against the latter (to each their own perspective: the contingent certainty of such an ostensibly democratising first-person is far from Pond’s mobile and mutable narration). Bennett’s perspective, as invented medium, works recursively through a series of scenes and objects in which a poetics of outlook, distance, depth, relation and scale is variously invoked and understood, in part as a means by which understanding itself is witnessed. The mechanics and metaphorics of modern linear perspective, as inherited rules, are acknowledged in such a way as to become akin to a medium, something both through and with which the narration happens. Pond is certainly cognizant of perspective as ideology and of its attendant ‘falsification[s]’, to use Sebald’s term, but critique is far from a defining mode; and while a transvaluing of inherited rules is likewise present, particularly with regard to the conventional ideological privileging of a metaphorics of depth, it is one among many variations. Perspective never settles into place as a stable object in the textual field of the novel. Perspective-as-medium is instead an element the novel is variously in, about and constituted from, as, respectively, environment, conceptual object and technique. The rhetoric of perspective as imagined in Pond is thus both ‘coercive and generative’; and it is in the animate combination of the two that lies the distinctive contemporaneity of the novel.Footnote29 It is something mobile, of a piece with the narrator’s passing confession that ‘It’s the location, actually – appearing to be located, to be precise – that’s what I object to’ (p. 61). Against fixity she expresses a desire to be ‘moving’, ‘silently overlapping’, hence a shifting between the highs and lows of, respectively, a ‘bird-like exuberance’ and the ‘warm and tender mass of radiant darkness’ that is the ‘bare soil’ (p. 140).

The narration in Pond is eccentric – not in the misogynistically folkish sense of the whimsical or peculiar, but precisely in the terms of the original astronomical meaning: as being out of or away from the centre. Classical single-point perspective is structurally centring, not to say anthropomorphic, in so far as it produces and organises a view according to the predicated situating of a human viewer for whom the given scene, recognised as such by its conformity with other such scenes, appears as if naturally occurring. In its making of location, linear perspective is an act of locating. A perspectival imaginary – of distance and proximity, depth, relation, scale and so forth – follows from this as a set of interrelated metaphors for conceiving ways of knowing, comprehending and narrating. Perspective specifically as the rhetoric of a way of seeing and perspective, as ‘symbolic form’, as a rhetorical means of making known: each of these aspects is present in Bennett’s novel eccentrically: in the relational arrangement of its differently shaped parts; in its fluctuations of narrational register such that style remains mobile rather than monocular; in thematic statements about outlook, depth and distance; in figurings of the matter of understanding; and in anomalous but unflawed objects that appear as metaphors for the form and content of the text, notwithstanding the narrator’s avowed dislike of ‘turning things into other things’ (p. 165). The first two of these features are experienced by the reader also, as performative unsettlings of those conventions of form and style – a stable arrangement of parts, so of part to whole, and a stylistically consistent narratorial voice such that voice is experienced as a figure for personhood – according to which a novel is felt to be located and in focus. Unsettlings, but not refixings: the novel as readerly environment remains as mobile-seeming for the reader as appear the represented mind, person and environment of the narrator.

Krauss’s revised conception of medium thus provides a way of identifying, naming and coming to understand something elemental in Pond, something that also feels near in spirit to Bennett’s aesthetic orientation. I have stayed close to the text so as to avoid, in so far as that is possible, the performative contradiction of a summative overview. In an interview with fellow-novelist Sheila Heti, Bennett expresses frustration with this kind of interpretive move in perspectival terms: as effecting what Heti calls a critical ‘aboveness’ according to which readerly viewpoint the work is considered to have been framed as a whole and thereby understood.Footnote30 Bennett seeks rather to transcribe something of the felt process of understanding itself as mobile and changing, hence a frustration of attempts at a secured critical viewpoint from which the established scene of the novel might be conjured and thereby surveyed. It is in Pond’s own stylistic and conceptual idioms that such a transcription is enacted. A rhetoric of perspective, ‘explicitly plotted or discreetly implied’, is one such idiomatic repertoire.Footnote31

This is not, of course, to suggest that sympathetic parallels with contemporaneous discourses are not possible – that the occasion for a conventionally well-placed zooming-out, in critical terms, isn’t eminently available – only that Pond, in its perspectival medium, provides its own way of seeing and making seen. Most obvious among potential parallels is that of an environmental or post-human epistemology.Footnote32 It would require only a small critical step to move from Pond’s mobile and eccentric idiom to theorisations in this mode. In Bennett’s own description, the narrator is at times a ‘peregrine self’, ‘fluid, exotic, and nebulous’;Footnote33 something ‘like an element. A physiological manifestation perhaps, in the same way the rocks and trees are physiological manifestations. Material. Matter. Stuff’ (p. 86). An element – or perhaps a medium conceived as something ambiently in-between. Pond is alert to moments ‘when the inner, the outer and the beyond are caused by simple things to somehow merge’.Footnote34 For it is in such mergings, rather than from the inherited vantage points of the ‘necessary outlook’, ‘that one briefly feels at home’. Loosened from its inherited moorings, perspective becomes a mobile home open to that ‘errant poignancy’ that is one of this novel’s signature inventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Claire-Louise Bennett, Pond (London: Fitzcarraldo, 2015), p. 151. References henceforth in the text.

2 Brian Dillon, ‘Hmmmm, Stylish’, London Review of Books, 38.2 (October 2015), https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v38/n20/brian-dillon/hmmmm-stylish.

3 Peter Boxall, Twenty-First-Century Fiction: A Critical Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 2.

4 Boxall takes his lead here from Sartre’s now familiar account of the present as ‘indefinable and elusive’, comparable in experience to ‘a man [sic] sitting in a convertible looking backward’ for whom the present appears as ‘flickering and quavering points of light’ (quoted in Boxall, pp. 1, 2).

5 ‘Symbolic form’, a term coined by Ernst Cassirer, was adopted by Cassirer’s colleague Erwin Panofsky in his influential study of perspective published in 1927. The term is resistant of easy summary, especially as used by Erwin Panofsky. Perspective thus conceived is not only a technique of representation, but a worldview, including at the phenomenal level – with the crucial proviso, as Christopher Wood suggests, that ‘It is perspective . . . that makes possible the metaphor of Weltanschauung, worldview, in the first place’ (Wood, in Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, intro. and trans. Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books, 1991), p. 13).

6 The related ideas of a rhetoric and a poetics of perspective, as used variously here, are taken from James Elkins, The Poetics of Perspective (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1994) and Hanneke Grootenboer, The Rhetoric of Perspective: Realism and Illusionism in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Still-Life Painting (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2006), respectively. The history and theory of perspective are undoubtedly complex. Panofsky and Hubert Damisch are the key twentieth-century texts (Damisch, The Origin of Perspective, trans. John Goodman (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1994)). While Elkins and Grootenboer provide helpfully contrasting summaries of the topics involved, Margaret Iverson’s review essay provides a concise starting point for the non-specialist (‘The Discourse of Perspective in the Twentieth-Century: Panofsky, Damisch, Lacan’, Oxford Art Journal, 28. 2 (2005), pp. 191–202).

7 Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, ed. and trans. Rocco Sinisgalli (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 39.

8 Elkins, The Poetics of Perspective, p. 13.

9 The figure is Jane White, the artist’s wife. The photograph was taken in Newark, Ohio.

10 Henry David Thoreau, Walden (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 159.

11 Linda Hutcheon, The Politics of Postmodernism, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 14.

12 W.G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, trans. by Michael Hulse (London: The Harvill Press, 1998), p. 19.

13 Ibid., p. 92.

14 Ibid., p. 83.

15 Ibid., p. 124.

16 Ibid., p. 125.

17 On the subject of Sebald and perspective, see, for example, Rosa Mucignat, ‘Perspective and Historical Knowledge: Margis, Sebald, and Pamuk’, Modern Language Notes, 133.5 (2018), pp. 1254–76.

18 Kazuo Ishiguro, A Pale View of Hills (London: Penguin, 1983), p. 104.

19 Ibid., p. 137.

20 Ibid., p. 138.

21 Ibid., p. 178.

22 Rita Felski, The Limits of Critique (Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 2015), p. 20.

23 Cara L. Lewis, ‘Beholding: Visuality and Postcritical Reading in Ali Smith’s How to be both’, Journal of Modern Literature, 42.3 (2019), 129–50. My reading of Pond is similar to Lewis’s reading of Smith’s How to be both in so far as we each identify a post-critical orientation in the respective novel’s representation of what Lewis calls visuality. Where I draw on Rosalind Krauss’s revised conception of medium, Lewis uses beholding as theorised by Michael Fried. For a different but closely related reading of the Smith, see Elizabeth S. Anker, ‘Postcritical Reading, the Lyric, and Ali Smith’s How to be both’, Diacritics, 45.4 (2017), 16–42.

24 For examples of the author’s art writing, see Bennett, Fish Out of Water (Juxta Press, 2020); ‘Large Issues From Small’, Frieze 6 (October 2017), www.frieze.com/article/large-issues-small; and ‘How Paint and Perception Collide in the Work of Late Surrealist Dorothea Tanning’. Frieze 201 (March 2019), www.frieze.com/article/how-paint-and-perception-collide-work-late-surrealist-dorothea-tanning.

25 I have drawn primarily on Krauss’s, Under Blue Cup (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2011) for the following summary of a contemporary revision of the idea of medium. See also Krauss’s, ‘A Voyage on the North Sea’: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

26 Krauss, Under Blue Cup, p. 3.

27 Ibid., p. 17.

28 Ibid., pp. 19–20, pp. 70–76.

29 T. J. Clark, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing (London: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 141 (emphasis added).

30 Interview with Sheila Heti, 17 August 2021, www.londonreviewbookshop.co.uk/podcasts-video/podcasts/claire-louise-bennett-sheila-heti-checkout-19

31 Clark, The Sight of Death, p. 141.

32 Other possibilities for more overtly theorised readings of Bennett’s perspectival poetics include the gendering of viewing point, for which Pond might be paired with Adriana Cavarero’s account of subjectivity conceived in terms of inclination rather than a masculinist verticality and rectitude (Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude, trans. Amanda Minervini and Adam Sitze (Stanford University Press, 2016); and the ideology of visibility in the history of the novel as imaged and figured by the window (and doorway), a history traced by Jacques Rancière, The Edges of Fiction, trans. Steve Corcoran (London: Polity, 2020), pp. 13–51.

33 ‘Claire-Louise Bennett on Writing Pond’, Irish Times, 26 May 2015, www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/claire-louise-bennett-on-writing-pond-1.2226535.

34 Bennett, ‘Large Issues From Small’.