ABSTRACT

This article addresses why the campaign of Kerbogha’s combined forces against the First Crusade failed by using accounts in Arabic, Armenian, Greek, Latin, and Old French. The discussion starts with an overview of how the different claims that explain the campaign’s failure have evolved since the eighteenth century. Then, for the first time, Kerbogha’s route from Mosul to Antioch has been precisely recreated, revealing a longer campaign than formerly estimated. The focus of the article then discusses the reasons why Kerbogha besieged Edessa. This section is followed by an explanation of why the failure of the siege led to the collapse of the entire campaign. Finally, the tactics used during the battle of 28 June 1098 are re-evaluated by considering the poor condition of the combined Muslim force. The article claims the campaign primarily failed because of the deficient structure of the army and the rivalries between its commanders.

Introduction

The siege of Antioch (1097–1098) was a milestone in the First Crusade that culminated in a final battle on 28 June 1098 between crusaders and a Muslim coalition. A long-standing historiographical tradition assumes that “The Christians defeated Kerbogha against overwhelming odds”.Footnote1 By providing a detailed narrative of the campaign before Antioch, and exploring its objectives, decisions, and consequences, this article reassesses the causes of the Muslim failure. In so doing, it unpicks accusations by both chroniclers and historians concerning the military incompetence of Kerbogha, atābak of Mosul (d. 1102), to offer a new analysis. First, it demonstrates that the campaign lasted longer than historians have thought; it was not a two-month campaign but an operation lasting over three months, with implications for its logistical requirements. Second, it explains the structural weakness of the Muslim coalition and how it affected the campaign. Third, instead of assuming Kerbogha’s siege of Edessa en route to Antioch was a complete mistake, it highlights the strategic reasons that justified an attack on Edessa. Thus, it argues that the crucial mistake of the campaign was raising the siege of Edessa before its capture, ultimately leading to the rapid self-destruction of the Muslim coalition in front of Antioch. This critical stage was aggravated by Kerbogha’s behaviour towards other amīrs, and ethnic rivalries between Arabs and Turks. Finally, the discussion of the final battle shows that the battle plan adopted by Kerbogha, while being extremely risky, was dictated by the circumstances rather than by incompetence.

Context and Historiography

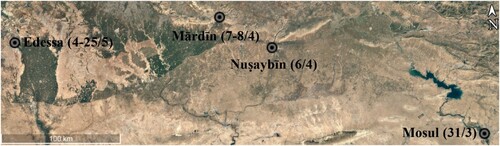

Yāghī Siyān (d. 1098), governor of Antioch, called for help during the spring of 1098 to defeat the crusaders who had started the siege of his city in October 1097. Kerbogha, atābak of Mosul, answered the call and gathered his troops. He departed from Mosul on 31 March 1098 and then besieged Edessa from 4 to 25 May.Footnote2 Failing to take the city, Kerbogha moved away towards Marj Dābiq.Footnote3 There, he gathered with Syrian amīrs, including those of Duqāq (d. 1104), Janāḥ al-Dawla (d. 1102–3) and Suqmān ibn Artuq, Lord of Jerusalem (d. 1104–5). Together, they formed an army, which will be referred to as “the coalition” in the rest of this article. Aware of the arrival of the coalition, the crusaders managed to take the city of Antioch by assault on the night of 3–4 June but failed to capture its citadel. The Muslim vanguard reached Antioch on 5 June, while the rest of the coalition arrived on 6 June.Footnote4 Kerbogha subsequently besieged the crusaders in Antioch, until the complete defeat of the coalition on 28 June. The second siege of Antioch and its final battle have been widely studied, but Kerbogha’s early campaign received little attention from medieval writers – and, consequently, has largely escaped the notice of historians. However, the early campaign offers major insights that help to explain Kerbogha’s defeat at Antioch. In three months, Kerbogha had travelled 675 kilometres, led two sieges, and fought a major battle.

James Wilson has recently explored the Arabic accounts of Kerbogha’s siege of Antioch in great detail.Footnote5 He lists 18 different Arabic accounts for the study of the siege of Antioch by the Muslims, none of their authors being eyewitnesses to the events of the First Crusade; his article should be consulted for an overview of these narratives’ respective times of writing.Footnote6 Twelve of these Arabic narratives offer little to work with, such as that of Ibn al-Qalānisī (d. 1160), who dismisses Kerbogha’s participation in the campaign in favour of mentioning Syrian troops and the coalition’s defeat, while being silent on other events of the campaign.Footnote7 However, six accounts provided some useful evidence: Abū l-Fidāʾ (d. 1331), Ibn al-ʿAdīm (d. 1262), Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233), Ibn al-Dhahabī (d. 1348), al-Nuwayrī (d. 1331) and Sibṭ Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 1256).Footnote8 Ibn al-ʿAdīm aside, these accounts provide close evidence of whose amīrs were present, the merging of Muslim contingents into one force at Marj Dābiq, the second siege of Antioch, and the battle of 28 June. All the Arabic narratives but Sibṭ Ibn al-Jawzī’s gave an account of Kerbogha’s bad behaviour towards other amīrs. Ibn al-ʿAdīm offers the most detailed Arabic account of the itinerary and the massive desertions from the coalition.Footnote9 However, all remained silent on the early campaign and the siege of Edessa, ignoring the latter event, which decided the outcome of the entire expedition. Both Ibn al-ʿAdīm and Ibn al-Athīr are very valuable because of the quality of their sources, despite not being contemporaries of the events.Footnote10 Alex Mallett rightly argues that Arabic sources on the crusades are too often “ignored if they disagree” with Latin sources.Footnote11 Therefore, this article treats all narratives equally and does not ignore Arabic, Armenian, or Syriac sources when their description of events differs from Latin accounts. However, one should note that there is an overall lack of a detailed account of the First Crusade in Arabic accounts. Consequently, Armenian, Latin, Old French, and Syriac narratives are the main sources for the study of Kerbogha’s campaign.

Latin and Old French narratives have therefore to be split into two categories: historias and chronicles on one hand, and chansons de geste on the other hand. Latin narratives provide us with the core details of the second siege of Antioch.Footnote12 Historias of the First Crusade can be distinguished between eyewitness accounts and later works based on these eyewitness sources.Footnote13 Historians also looked at the textual traditions of these historias and revealed important connections between certain texts. The point of this article is not to discuss these traditions, but some characteristics need to be mentioned. Four main eyewitness accounts exist: the anonymous Gesta Francorum, and the narratives of Fulcher of Chartres, Peter Tudebode, and Raymond of Aguilers.Footnote14 In addition, Robert the Monk was an eyewitness to the Council of Clermont, but not to the expedition.Footnote15 The Gesta Francorum, written by an anonymous knight, was used as the main source for a second generation of sources written by Baldric of Bourgueil, Guibert of Nogent, Peter Tudebode, and Robert the Monk, which, in Elizabeth Lapina’s words, can be categorised as the “Gesta family”.Footnote16 Textual traditions shaped groups of narratives, but each account had a degree of originality in the choice of words, as well as the addition of unique anecdotes obtained from oral tradition. Therefore, the originality of each of these texts must not be dismissed.Footnote17 Indeed, most authors of the “Gesta family” provide a different reading of some key events in Kerbogha’s campaign. Consequently, the historias of Baldric of Bourgueil, Guibert of Nogent, Peter Tudebode, and Robert the Monk have sometimes been used alone when they provide original details. In contrast to the “Gesta family”, both Raymond of Aguilers’s and Ralph of Caen’s accounts offer limited information about Kerbogha’s campaign,Footnote18 while, the narratives of Albert of Aachen (fl. twelfth century), Fulcher of Chartres (fl. twelfth century), and William of Tyre (d. 1184) provide crucial information on Kerbogha’s campaign before Antioch.Footnote19 While Fulcher was an eyewitness to the siege of Edessa, Albert of Aachen did not participate in the events of the First Crusade, and William of Tyre had not been born at the time of the expedition and wrote decades later. However, Albert of Aachen’s historia is the longest and most detailed account of the First Crusade.Footnote20 Albert represents the imperial tradition that was long neglected after the works of the nineteenth century to the advantage of the French tradition represented by the sources of the “Gesta family”.Footnote21 Albert’s historia was based on returning crusaders’ accounts,Footnote22 and evidence is often confirmed by other Latin and Oriental sources.Footnote23 Albert is therefore a major source on the campaign, despite not being an eyewitness.

The second category of narratives of the First Crusade are the Old French chansons de geste, usually considered by historians as fictional accounts. However, the Old French Chanson d’Antioche had a historical base that was adapted to provide an epic narration of the events of the First Crusade.Footnote24 As Abbès Zouache has written, this means that the Chanson d’Antioche is a mixture of myth and history,Footnote25 so caution is required. However, the Chanson d’Antioche also provides strong evidence about the siege of Edessa and the siege of Antioch that echoes other sources, such as Albert of Aachen, Robert the Monk, and both Armenian and Syriac narratives,Footnote26 so evidence offered by the Chanson d’Antioche should not be discarded,Footnote27 and it has been used in this article when another narrative offered similar evidence.

The last category of accounts was produced in Armenian, Greek, and Syriac. Well-informed, Matthew of Edessa (fl. twelfth century) and the anonymous author of Edessa (fl. thirteenth century) present the best evidence for Kerbogha’s siege of Edessa.Footnote28 In comparison, Anna Comnena (d. 1153), Bar Hebraeus (d. 1286), and Michael the Syrian (d. 1199) provide little.Footnote29 Altogether, Kerbogha’s campaign is described in most detail by authors who were not amongst the coalition, raising questions on their accuracy in describing it. This is a major weakness of the corpus from which conclusions can be drawn and this disadvantage means that most of what is known about Kerbogha’s campaign remains hypothetical, as no definite answer can be corroborated by authors who were within his ranks. However, this weakness is shared by most of the literature on the First Crusade, because Arab authors had limited interest in narrating the expedition in depth. Therefore, while this article addresses documentary lacunae, we must draw the most plausible conclusions from available evidence. These narratives reveal the structural weakness of the Muslim combined forces and the rivalries between the commanders.

The historiography of the crusades developed the claim that the coalition’s campaign was an utter disaster and that Kerbogha was incompetent. Jean-Baptiste Mailly (1780) first mentioned the delay in reaching Antioch that was caused by the siege of Edessa.Footnote30 Since then, most of the historiography has considered Antioch as the sole objective of the campaign and supposed that other motives were distractions, an assumption that needs to be nuanced. Charles Mills in 1820 formulated the first criticisms of Kerbogha based on the siege of Edessa. For Mills, the delay created by the siege of Edessa allowed the crusaders to capture Antioch.Footnote31 Another claim suggesting Kerbogha’s incompetence was put forward by Jean-Baptiste Mailly and then Charles Oman (1898), who argued for his supposedly poor tactics during the Battle of Bridge Gate (28 June 1098).Footnote32 René Grousset (1934–1936), Steven Runciman (1951–1952), and Joshua Prawer (1969–1970) agreed that the siege of Edessa was a mistake but did not cirticise Kerbogha’s tactics during the Battle of Bridge Gate.Footnote33 While most historians do not mention the events prior to Kerbogha’s arrival at Antioch,Footnote34 some, following Claude Cahen, have argued for the significance of the Edessan mistake.Footnote35 For Cahen and those who follow his reasoning, had the coalition ignored Edessa and marched straight towards Antioch, it would have had a greater chance of success. However, such an interpretation relies on the benefit of hindsight. The situation appeared differently on the ground. According to medieval narratives, Antioch was not in such a state of emergency that Kerbogha would have been forced to rush to its aid as fast as he could. Rather, he only learned of the severity of the situation when he was close to Antioch. Furthermore, Syrian amīrs and their forces would not have been able to arrive in northern Syria to join Kerbogha’s contingent if the latter had not spent 40 days in the region of Edessa.Footnote36 In the hypothetical scenario of Kerbogha ignoring Edessa and marching straight to Antioch, the Muslim coalition would have been noticeably smaller when facing the crusaders. Thus, a smaller army would likely have had a lesser chance of defeating the crusaders on the battlefield.

Finally, there were strong strategic reasons for besieging Edessa.Footnote37 In fact, the major mistake that cost Kerbogha the campaign was raising the siege of Edessa, not laying siege to the city. This was a collective failure rather than one caused by Kerbogha’s own incompetence, for he raised the siege of Edessa because of his amīrs’ pressure to do so.Footnote38 This dramatically raised the campaign costs, impacting soldiers’ will to fight and explaining the coalition’s failure before its final battle took place. The coalition was on the verge of disbanding on the eve of 28 June.

Historians have misunderstood both the condition and size of the coalition before the battle and consequently argued that the defeat at the battle of 28 June was due to Kerbogha’s incompetence.Footnote39 John France’s Victory in the East became the reference point for the Battle of Bridge Gate following its publication in 1994. He argues that Kerbogha’s failure to attack the crusaders when they were crossing the Orontes was a major mistake, which caused Kerbogha’s defeat.Footnote40 Most historians also claim that the numerical advantage of the coalition and the poor situation of the crusaders made the Christians’ victory unexpected,Footnote41 here ignoring the importance of the disunity amongst the coalition.Footnote42 France argues that the tensions between the various amīrs were a factor in the defeat, but not the main reason for it.Footnote43 However, the coalition was on the verge of self-implosion and experienced massive desertions in the days before the battle, a factor that has been mostly underestimated by historians. Thus, these circumstances forced Kerbogha to adopt a risky but necessary tactic on the battlefield.Footnote44 He decided to surround the entire crusading army and end the campaign with a decisive victory. This required delaying the attack until the entire crusading army had crossed the Orontes, in order to remove any potential for his enemy’s retreat.Footnote45 The reasons for Kerbogha’s failure at the Battle of Bridge Gate were, therefore, many and cannot be limited only to Kerbogha’s battle plan.

The argument for Kerbogha’s incompetence relies on a deep underestimation of the coalition’s structural fragility and how this affected their campaign. Some historians adopt a reading that presents the crusaders’ victory on the battlefield on 28 June 1098 as miraculous,Footnote46 while contemporary narratives depict a critically disunited coalition. Grousset was the first to recognise that the morale of the coalition troops at Bridge Gate was poor, while the crusaders were desperate.Footnote47 For Carole Hillenbrand, it is the disunity of the coalition that explained their defeat.Footnote48 Michael Köhler suggests that the failure mainly originated from both the “heterogeneous” character of the coalition and Kerbogha’s behaviour.Footnote49 Runciman argued that besieging Edessa was a mistake,Footnote50 but claimed that Kerbogha’s situation was so critical on 28 June that the army was near disbanding and that he could no longer besiege Antioch.Footnote51 Consequently, he had to adopt a risky tactic on the battlefield to destroy the entire crusading army.Footnote52 The existence of two historiographical traditions – one arguing for Kerbogha’s mistakes and the other claiming the Muslims’ lack of homogeneity was decisive – make it necessary to provide an in-depth approach to Kerbogha’s campaign.

Dating the Campaign

Determining the length of Kerbogha’s campaign is crucial for understanding its failure, but historians have persistently underestimated its duration, following Runciman’s estimate that the campaign began in early May 1098.Footnote53 It is difficult to understand what evidence historians used to date the start of the campaign as precise footnotes on this specific matter are lacking. It seems that most scholars based the start of the campaign on Heinrich Hagenmeyer’s dating of the siege of Edessa from 4 to 25 May 1098.Footnote54 However, by using Hagenmeyer, former studies forgot to add the time needed by Kerbogha to march from Mosul to Edessa as part of the campaign’s duration. Surprisingly, apart from Susan Edgington,Footnote55 historians have discarded the only estimate that provided some time between the start of the campaign and the siege of Edessa, that proposed by Amin Maalouf, who suggested that the campaign began in the last days of April.Footnote56 While Maalouf’s estimate still underestimates the duration of the campaign, it remains the closest to a starting date of 31 March 1098, as argued in this article. To understand the campaign’s ultimate failure, it is necessary to appreciate that it lasted substantially longer than historians have thought, which had a massive effect on troops’ expenses, which in turn led to large-scale desertions – as argued later in this article. For instance, Jay Rubenstein claims “Kerbogah’s great army at Antioch almost immediately began to fracture” after their arrival at Antioch in early June. He therefore misses the fact that Kerbogha had already been campaigning for a minimum of 60 days when the coalition arrived at Antioch.Footnote57

Dating the progress of the coalition is complicated, but the following section aims to recreate an estimated route and chronology for Kerbogha’s itinerary, which can be split into three phases: from Mosul to Edessa, the campaign in the Edessan region, and from Edessa to Antioch. In what follows, I challenge the claim that the campaign departed from Mosul at the beginning of May, showing that it departed on 31 March at the latest.Footnote58 Then, the work on the second phase confirms Hagenmeyer’s dating of the siege of Edessa as lasting from 4 to 25 May,Footnote59 but argues, like Edgington, that Muslim operations in the region of Edessa began earlier, on 15 April.Footnote60 Finally, the work on the third phase consists of recreating the march from Edessa to Antioch, where the army arrived on 6 June.Footnote61

The prerequisite for recreating Kerbogha’s itinerary is to discuss the distance medieval armies could potentially cover in a day, which has been the subject of some investigation.Footnote62 However, no historian has attempted to use average distance to recreate Kerbogha’s campaign. The consensus is that large armies were able to cover between 19 and 23 kilometres per day on good roads.Footnote63 Thus, the First Crusade crossed Anatolia by travelling an average of only 10 kilometres a day.Footnote64 However, cavalry-based forces could cover great distances more quickly – “up to 65–80 kilometres in a day”, as John Haldon argues, though this raises the question of how long a horse could maintain this pace.Footnote65 Such estimates must be lowered for the coalition, for four reasons. First, the coalition was not solely composed of cavalry. Second, the coalition was an unusually large force, using a single road. Third, the coalition is reported to have gone slowly, being overcrowded by pack animals and wagons: “uiam iuxta onera curruum suorum et sarcinas iumentorum et camelorum diebus multis moderabatur”.Footnote66 Fourth, despite no day-to-day report being available for the coalition, an interesting comparison can be made with Ibn Jubayr’s detailed account of his travels in the region – from Mosul to Nuṣaybīn in June 1184. He likely used the same road as the coalition by travelling with a caravan that covered an average of 47 kilometres per day.Footnote67 It took Ibn Jubayr four days to reach Nuṣaybīn from Mosul. As armies were going slower than caravans, the coalition could only have covered less distance per day than Ibn Jubayr. It seems reasonable to accept that the coalition covered a daily distance of no more than 30 kilometres.Footnote68 Unless mentioned otherwise, distances are given as the crow flies in this article, so this estimate reflects the fastest scenario of the march, which may in reality have been slower. That is to say, the estimated chronology provided in this article represents the fastest scenario, while it is possible for the coalition’s campaign to have lasted for a longer period.

The expedition started in Mosul, located 410 kilometres from Edessa. Contemporary narratives give no hint to date the beginning of the coalition’s journey, so the dating of the stage from Mosul to Edessa relies on an estimated daily distance covered by the army but not on written evidence. Applying an average 30-kilometres daily march, we can suggest that it took the coalition a minimum of 14 days to cover the distance from Mosul to Edessa. In addition, the coalition stopped near Mārdīn to gather Jazīran contingents, also accumulating a large quantity of pack animals, wagons, supplies, and equipment. According to Albert of Aachen, this stop was made at Tall al-Shaykh: “ad castrum Sooch conuenerunt”.Footnote69 It was also necessary to organise a marching order and choose an itinerary, which likely took an entire day, maybe more. Consequently, the itinerary from Mosul to Edessa lasted a minimum of 15 full days, arriving on the sixteenth day in the region of Edessa. Therefore, the claim that the coalition’s campaign started in early May can be entirely rejected.Footnote70 Maalouf came the closest to the potential date by proposing that the campaign began in late April.Footnote71 Kerbogha likely left Mosul on 31 March at the latest; in this tentative scenario, he reached Nuṣaybīn on 6 April and arrived near Mārdīn on 7 April. He then left on 9 April to reach the Edessa region on 15 April, concluding the first phase of the campaign ().

Since Hagenmeyer’s chronology of the First Crusade, historians have assumed the siege of Edessa to have lasted from 4 to 25 May 1098, using Fulcher of Chartres’s claim that the siege lasted three weeks: “tres hebdomadas”.Footnote72 In doing so, historians rejected two other potential durations, proposed by Albert of Aachen and Matthew of Edessa. Albert gives a duration of three days – “triduo”,Footnote73 but this has been rejected by John France, who prefers the eyewitness testimony of Fulcher.Footnote74 However, France also rejects Matthew of Edessa’s 40-day siege.Footnote75 Matthew and Fulcher were both eyewitnesses to the siege and so neither version can be favoured over the other.Footnote76 It is Edgington who likely solved the dating issue by claiming the coalition assaulted Edessa for three days, during a 21-day siege, within a longer campaign against the Edessan region lasting a total of 40 days.Footnote77 Kerbogha, then, arrived in the region on 15 April and spent 20 days seizing harvests in the countryside.Footnote78 During this period, Baldwin of Boulogne (d. 1118) attacked the coalition and seized many pack animals and supplies.Footnote79 This led to the presence of huge numbers of pack animals in Edessa during the subsequent siege. The siege itself lasted from 4 to 25 May,Footnote80 but the campaign in the Edessan region likely started earlier, on 15 April.

Kerbogha’s route from Edessa to Antioch can be estimated with a better degree of precision using the average distance per day mentioned above and evidence on both road networks existing in the period and written evidence of some locations where the coalition went. Kerbogha’s force left Edessa on 25 May and should have reached the Euphrates on 27 May. This required two days to cover 60 kilometres, and a third for the remaining 10 kilometres, plus the time needed for crossing the river by boat at multiple points, likely between al-Bīra and Jarābulus.Footnote81 Kerbogha could have reached Marj Dābiq on 30 May after three days of marching, covering between 70 and 90 kilometres. Kerbogha spent 31 May incorporating Syrian contingents into the coalition.Footnote82 Cahen has argued that the army might have spent more days in Marj Dābiq, which is possible.Footnote83 One day seems the absolute minimum for the merging to be accomplished, and so is favoured in this recreation of the itinerary based on the fastest possible movement of forces. The coalition then departed on 1 June towards Artāh. They reached Aʿzāz the same day to join the Roman road heading to Antioch by Afrīn.Footnote84 They passed Afrīn likely early on 2 June. According to Bar Hebraeus and Michael the Syrian, a section of the coalition went to Baghrās; this makes sense if the objective was to complete the encirclement of Antioch, but it was not the main force’s itinerary.Footnote85 If true, the force likely split on 3 June, reaching Baghrās at best on 4 June. Most of the coalition arrived at Artāh on 3 June.Footnote86 Altogether, the coalition covered 73 kilometres following Roman roads between Aʿzāz and Artāh. The news that Antioch had fallen likely reached the force during the night of 3–4 June, since a vanguard comprising 300 cavalry reached Antioch on 4 June and engaged the crusaders in a minor ambush, with success.Footnote87 Likely departing on the night of 4 June, a large Muslim cavalry force took the Iron Bridge from its Frankish garrison on 5 June.Footnote88 Meanwhile, Kerbogha probably used 4 June to negotiate the appointment of a new governor for Antioch’s citadel.Footnote89 The coalition resumed its progression from Artāh on 5 June and reached Antioch on 6 June.Footnote90 Contrary to Yuval Harari’s claim, Kerbogha was not going “at a leisurely pace”.Footnote91 In fact, he was going fast, covering around 30 kilometres a day. This narrative of the campaign shows for the first time that it was possible for the coalition to reach Antioch while leaving Edessa on 25 May ().

Previous studies have given the impression that Kerbogha’s campaign was short, lasting either the 23 days of the siege of Antioch, or two months, from the start of the siege of Edessa. Providing a precise narrative of the events is crucial: we can now see that the campaign likely lasted a minimum of 89 days before the final defeat at Bridge Gate, during which Kerbogha’s troops covered 675 kilometres. Then it is impossible to know how long it took for the defeated troops to return to their homes, but this needs to be added to the total duration of the campaign, likely adding multiple weeks. This had significant implications, given the major logistical requirements to support an operation for that long and that far from Kerbogha’s own supply base. The campaign was carefully planned during harvesting season to ease the coalition’s supplies, which helped when besieging Edessa. This was aimed at troops who used pack animals to carry their supplies such as muṭṭawwiʿa (volunteers), infantry, and amīrs’ ʿasākir (personal armies). This had less impact on nomadic and semi-nomadic contingents such as Turkmen. However, using local harvests became impossible once Antioch was reached, as the region had been depleted of resources by the months-long siege of the city by the crusaders. In addition, this raised the question of whether pasture around Antioch was possible after the months-long siege by the crusaders. Therefore, it is likely that Turkmen had to complete the local grazing capacities by buying fodder for their herds.

The Coalition

The coalition was a conglomerate of multiple ʿasākir (armies) belonging to Jazīran lords commanded by Kerbogha, Lord of Mosul.Footnote92 They were later joined by other Syrian contingents and a large Arab force led by Wathāb Ibn Maḥmūd (fl. eleventh century).Footnote93 These leaders had opposing agendas, which harmed the campaign at Antioch.Footnote94 Köhler was right in arguing that the amīrs realised that the greater threat to their independence lay with Kerbogha ratherthan with the crusaders and that they had little interest in seeing the campaign succeed.Footnote95 Consequently, Kerbogha had little reason to trust in other amīrs’ loyalty and investment in the campaign. In addition to these regular troops, the coalition was joined by muṭṭawwiʿa – volunteers,Footnote96 who responded to the jihād propaganda surrounding the campaign but were ill-trained and lacked discipline. Their value on the battlefield was extremely poor. More importantly, large numbers of Turkmen completed the coalition, likely comprising most of the army. These were freemen cavalry troops.Footnote97 They were competent nomadic horse archers but lacked discipline, making it difficult to command them as a homogenous force and to control their hostile behaviour towards local inhabitants, even in allied lands.Footnote98 Their Islamisation was certainly incomplete by the late eleventh century, which means their primary motive was to enrich themselves, not religious devotion.Footnote99 Maintaining Turkmen for more than a few weeks was nearly impossible if booty was lacking since they would become reluctant to fight or would disburse.Footnote100 Finally, the various forces composing the Muslim coalition had never fought together and it was uncertain whether they would be able to fight uniformly together in battle. In contrast, the crusaders’ army was composed of battle-hardened troops that developed a high level of battle cohesion throughout the entire campaign.Footnote101 Consequently, the coalition had structural flaws that were decisive in the coalition’s failure.

One of the main challenges for the historian is to estimate army sizes in this period.Footnote102 Despite this difficulty and the unreliability of figures provided in the narratives, it is necessary to estimate the size of the coalition in order to understand the context of the campaign. No precise estimate of Kerbogha’s personal ʿaskar exists in medieval accounts. However, Zouache offers an estimate of 15,000 men for the average Islamic army of the time – excluding larger armies led by sultans themselves.Footnote103 Nicholas Morton claims that Mosul’s regular forces numbered around 15,000 men, including 4,000–8,000 cavalry, between 1100 and 1127.Footnote104 Consequently, it is likely that Kerbogha’s personal ʿaskar was of similar size. The coalition altogether was larger. France estimates that it numbered 60,000–90,000 men.Footnote105 Other estimates of 35,000–45,000 men have been made by historians.Footnote106 Zouache emphasises that the coalition no longer massively outnumbered the crusaders before the Battle of Bridge Gate, as there had been significant desertions.Footnote107 Therefore, France’s estimate likely corresponds to the coalition at its peak, while other estimates portray the coalition after the massive desertions that happened in front of Antioch. The coalition faced a crusader army of 20,000–30,000 men.Footnote108 These numbers need to be taken for what they are, however – estimates based on especially unreliable data. What matters is therefore more the comparison between the two forces’ respective sizes rather than the precise numbers themselves, which remain hypothetical.

While the nature of the narratives does not allow any definitive estimate of army sizes, it is clear that the coalition was of exceptional size. This represented a major challenge for Kerbogha, who had never controlled such a large army in the past. Leaders of the First Crusade experienced a similar challenge. However, they had over eight months – from around mid-August 1096 to 6 May 1097 – to get both their logistical and command systems working before reaching Nicaea and facing enemies.Footnote109 They designed successful systems used throughout most of the First Crusade, obtaining resources directly from the region, instead of waiting to be resupplied from distant bases.Footnote110 With a similar number of men, Kerbogha had to address those challenges in less than a month, which was too short to find a working system.Footnote111 Consequently, the coalition’s “great size was at once its biggest strength and its greatest weakness”.Footnote112 The unusual nature of both the size and the structure of the coalition directly contributed to the outcome of the campaign, as we shall see.

The Reasons for Besieging Edessa

Kerbogha’s main objectives were to defeat the crusaders at Antioch and to extend his personal influence over Syrian lords.Footnote113 This is why he made aiding Antioch conditional on the ceding of the citadel to his trusted man – Aḥmad Ibn Marwān.Footnote114 The same personal ambitions motivated other Jazīran commanders’ in leading Islamic coalitions in Syria until 1119.Footnote115 However, Islamic coalitions always faced local amīrs’ determination to maintain their own independence.Footnote116 That lack of unity was one of the main factors for why these Islamic coalitions failed. From Kerbogha’s point of view, besieging Edessa could have been a way to strengthen the unity of the coalition by granting Edessa as an iqṭāʿ to one amīr.

With the benefit of hindsight, historians including Hans Mayer have claimed that laying siege to Edessa “vainly” wasted time that was badly needed to relive Antioch, delaying a confrontation that, if undertaken earlier when the coalition had been at its largest, would have allowed the greatest chance of success.Footnote117 However, this argument should be discarded – for, if Kerbogha had ignored Edessa and rushed towards Antioch, he would not have been able to merge his forces with those of Syrian amīrs, considerably reducing the size of the coalition. This is why Harari claims that besieging Edessa was a way to make time for the Syrian amīrs to arrive.Footnote118 In addition, the crusaders, despite a months-long siege, had not breached Antioch’s defences, and the inhabitants were not starving. Yāghī Siyān still firmly held Antioch when Kerbogha arrived in the Edessan territory on 15 April 1098. No reasons were pushing Kerbogha to rush towards Antioch. Furthermore, modern historians know that Kerbogha’s objective was to attack the crusaders in front of Antioch, but this is the benefit of hindsight. Narratives do not provide evidence that the crusaders at Antioch knew of Kerbogha’s objectives before he left Edessa. In fact, the crusaders’ actions at the siege of Antioch hint towards their being unaware of Kerbogha’s march towards Antioch before a messenger sent from Edessa warned them, likely on 28 May.Footnote119 The intensifying of their activity following the arrival of the messenger to urge the capture of the city certainly suggests the crusaders’ ignorance of Kerbogha’s objective before his departure from Edessa on 25 May. As one knows, Antioch was taken by betrayal. However, the treason was properly organised only after the crusaders learned that the Muslim coalition had left Edessa and was marching towards them. As the messenger who was sent to the crusaders from Edessa departed when Kerbogha left Edessa, it is possible that a similar messenger would have been sent if Kerbogha had simply crossed Edessan territory instead of stopping there for 40 days. Consequently, it is possible that the crusaders would have taken the city by betrayal 40 days earlier, since Bohemond (d. 1111) and Firuz were already in contact. In both scenarios, Kerbogha would have had to besiege Antioch rather than facing the crusaders on the battlefield. Finally, Kerbogha’s objective was to defeat the crusaders, so Edessa had to be taken from Baldwin of Boulogne (d. 1118). The campaign was never just about Antioch.

Three strategic reasons justified the attack on Edessa. First, taking Edessa would have major logistical consequences for both the crusaders and the coalition. Gregory Bell demonstrates that the inability of the crusaders to maintain open and safe access to their supply base had a major impact during the first siege of Antioch.Footnote120 Edessa was one of their major supply bases, so losing it would bring major disruption to crusader logistics. In addition, by not taking Edessa, Baldwin would have been able to attack the coalition’s supply.Footnote121 Joshua Prawer has rejected the idea that Baldwin was a potential threat to Kerbogha,Footnote122 and it is true that Baldwin could not inflict major human losses on the coalition by attacking them in the field. However, Baldwin could hold up the coalition’s supplies by seizing their herds, which were vital to Turkmen and other nomadic or semi-nomadic continents of the coalition. Baldwin did indeed seize important quantities of supplies and animals from the coalition before the siege of Edessa, proving the threat was real: “spolia, camelos et iumenta cum rebus necessariis premissa in ciutatem Rohas abducens”.Footnote123 Moreover, Baldwin could have repeated his attacks on the coalition while their forces were marching towards Antioch, so Kerbogha understood that capturing Edessa was necessary to secure the rest of the campaign.

Second, Edessa controlled a fertile area, which could provide supplies for the coalition. The region around Antioch had been depleted of resources by the months-long siege of the city by the crusaders,Footnote124 so supplies for the coalition would have had to be sent from another region. Mosul was too far from Antioch to be used as a regular supply base. Aleppo, Edessa, Hama, Homs, and Shayzar were potential alternatives, but it was uncertain whether one single region could have provided enough supplies for such a huge army. Multiple centres had to be considered in the planning of the campaign. Edessa was certainly an attractive base. However, as Edessa was under Baldwin’s control, the region needed to submit to Kerbogha first. Once Edessa was controlled by the coalition, supplies could have been obtained at a lower price than from a neutral market, limiting army expenditure. As discussed below, unexpectedly high costs for troops, especially Turkmen, caused massive desertions and precipitated the failure of the entire expedition.

Third, taking Edessa meant Muslim troops could acquire booty. Turkmen in the coalition could not hope to pillage Antioch, which they were coming to rescue as an ally.Footnote125 Similarly, Kerbogha could not allow his troops to attack local Muslim lordships since he needed their military support to defeat the Franks. Consequently, loot had to be taken in Edessa or from the crusading army at Antioch, and taking Edessa was therefore necessary to secure the Turkmen’s full commitment to the coming battle against the crusaders and avoid desertions. Defeating a major force like that of the crusaders at Antioch required the full commitment of the coalition’s troops, so besieging Edessa was not only a sound option, but – given the challenges Kerbogha was facing – it was the only viable option.

The Consequences of Raising the Siege of Edessa

The coalition failed to take Edessa, after spending 40 days in the region, when amīrs put pressure on Kerbogha to raise the siege of the city: “consilium Corbahan dederunt ut nunc castra ab obsidione moueret”.Footnote126 None of the three objectives of the operation against Edessa were fulfilled. Edessa could not be used as a supply base, the Turkmen did not receive sufficient booty to secure their full commitment to the rest of the campaign, and Baldwin was able to both damage the coalition’s supply system and provide for the crusaders. The consequences of the failed attack on Edessa cannot be overstated.

What was worse, campaigning an extra 40 days in the region of Edessa had raised the supply costs for Muslim troops, who refused to bear these costs and deserted.Footnote127 To understand why, it is necessary to identify the coalition’s logistical requirements, although the lack of detail in the narratives of the event makes it impossible to quantify precisely the extent of this rise in cost. A medieval army composed of sedentary troops could carry up to 24 days’ supplies, but this capacity was conditioned by the ability to gather enough pack animals.Footnote128 A troop of 1,000 cavalry would need 2,250 mules to carry their supplies for 24 days.Footnote129 If the coalition was based on that model, its 60,000–90,000 men would have required over 100,000 mules. However, the coalition was not only composed of sedentary troops. Indeed, probably half of the total number of men came from nomadic or semi-nomadic backgrounds, such as the Turkmen and likely the Arab contingent led by Wathāb Ibn Maḥmūd. In order to feed themselves, these troops relied heavily on their herds rather than on pack animals, and so they depended on the availability of grazing. This caused few problems until the army arrived near Antioch, but local pasture there had been depleted for months by the crusaders. This means that to be well supplied the sedentary half of the army relied on pack animals, while the nomadic half of the coalition relied heavily on what their herds had to offer. The following section considers that the sedentary troops of the coalition had enough pack animals to carry 24 days’ supplies.

In a hypothetical scenario in which the coalition did not stop for 40 days in the region of Edessa, it would have taken them 28 days to reach Antioch. In that scenario, one full resupply was required to reach Antioch. Bell shows that troops had to pay for their own supplies.Footnote130 Instead of that scenario, however, the coalition took 68 days to reach Antioch. This means troops had to pay for three full resupplies, tripling the cost of the campaign – while they had not received substantial booty to cover their costs. Consequently, troops were substantially impoverished, which considerably damaged their morale. The extent to which Baldwin’s raid on the herds damaged the Turkmen’s supply system is unknown, but it would have added to these costs and they would have had to replace the lost animals or rely on buying supplies to replace them. The impoverished Turkmen, whose primary motive for fighting was to enrich themselves,Footnote131 would have understood both that the siege of Antioch would last more than a few days and that intense fighting would be required. One episode indirectly reveals the discontent among the troops. The coalition’s camp was established in the mountains where horses could not graze: “Sed pabulo herbarum in collibus minime reperto quod eorum equis sufficeret”.Footnote132 Troops likely pressured Kerbogha to move back to the plains where horses could graze without any new expense.Footnote133

While Kerbogha’s behaviour alienated the amīrs, who already had little reason to commit to the campaign,Footnote134 the rise in the campaign’s costs led to massive Turkmen desertions. Finally, the Arab contingent left the coalition following ethnic rivalries between Arabs and Turks.Footnote135 From a peak of 60,000–90,000 men, the coalition army may have fallen to as few as 35,000–45,000 men.Footnote136 Desertions were decisive in the campaign’s outcome, as it is likely about half the force deserted before the battle. Contrary to former claims that ignored those desertions,Footnote137 the coalition no longer vastly outnumbered the crusaders on the eve of the battle.Footnote138 The relative numerical advantage of the coalition over 20,000–30,000 crusaders was largely counterbalanced by the uncertain commitment of both Turkmen and amīrs’ ʿasākir to fight in a battle and the low quality of the many muṭṭawwiʿa. In addition, desertions were continually ongoing. In that tumult, there is little doubt the Islamic coalition was on the verge of self-destruction.

Why Did Kerbogha Reject the Crusaders’ Offer to Surrender?

Following their discovery of the Holy Lance on 14 June,Footnote139 the crusaders sent Peter the Hermit (d. 1115) to negotiate with Kerbogha. Two versions of the first offer exist in medieval narratives. One suggests that Peter offered to surrender in exchange for Kerbogha’s conversion,Footnote140 but such a condition was completely unacceptable for Kerbogha.Footnote141 The other version is that Peter demanded that Kerbogha lift the siege and return to Mosul, which was equally unacceptable.Footnote142 Some narratives claimed that Kerbogha made a counter-offer, demanding the crusaders’ conversion to Islam in exchange for receiving full ownership of Antioch.Footnote143 However, this seems unlikely, as other narratives indicate no other offer was made and that Kerbogha wanted to either capture or kill every crusader.Footnote144 Then, Peter likely made a second offer, suggesting combat between a few soldiers from each side. The winner would retain control of Antioch.Footnote145 If defeated, this would have been a huge blow to Kerbogha’s prestige, while, if victorious, he would gain little benefits and no booty and still have Edessa to defeat, so he had little reason to accept. In addition, narratives are unclear on whether the defeated crusaders would have gone back to Europe or to Edessa: “ipsi in terram suam pacifice”.Footnote146 Rubenstein argues that the safe conduct issued by Kerbogha was for Europe,Footnote147 but it seems unlikely that Kerbogha could provide safe conduct to the crusaders across Anatolia, which was not under his control. It is therefore possible that the safe conduct pertained to travel to Edessa. In that case, Kerbogha’s situation would have mostly worsened. While the crusaders were starving at Antioch, they would have been able to resupply in the Edessan region – strengthening them while weakening the coalition further. From Kerbogha’s perspective, the problem of dealing with the crusaders would not have been solved by only moving them from Antioch to Edessa. However, it would have provided Kerbogha with a symbolic achievement by relieving Antioch. While there is no definitive answer to the question of where the safe conduct was for, it is possible to judge the quality of the terms offered by Peter the Hermit to Kerbogha as being extremely poor. Adding to the deficient terms offered, Peter the Hermit’s embassy did not follow diplomatic protocol, which William of Tyre later described as a clear lack of respect from Peter the Hermit: “nullamque ei omnino exhibens reverentiam”.Footnote148 While some historians have rightly discussed Kerbogha’s arrogance in the talks, they have surprisingly ignored Peter’s equivalent misbehaviour, despite its importance in harming the good conduct of the diplomatic talks.Footnote149

The Battle of Bridge Gate (28 June 1098)

As a diplomatic outcome was not possible, the campaign would end violently. This section aims to discuss the course of the battle to show that the crusaders’ victory was not a victory against all odds,Footnote150 and that Kerbogha did not take foolish tactical decisions.Footnote151 As Kerbogha sought a battle, he had to obtain intelligence on the crusaders. However, it is evident that he lacked accurate knowledge since he underestimated the crusaders’ capacity to fight by the time of battle on 28 June.Footnote152 Kerbogha realised he underestimated the crusaders when they deployed for battle, but he could neither refuse to engage them nor wait for another battle opportunity, as desertions were destroying his army.Footnote153 In addition to the poor knowledge of the exact state of the crusaders’ army, it appears that their sally took Kerbogha by surprise; narratives inform us that the Muslims were preparing their meal when they learned about the sally as the crusaders found cooked meat in the Muslim camp after the battle: “in letibus et in ollis parvaverant carnes ab obsonium”.Footnote154 This surprise was due to the successful misinformation game played by the crusaders. It must therefore be noted that, while the surprise was a factor, the deployment of the crusaders through a single narrow gate took time. This gave the Muslim besiegers time to react and deploy before being attacked by the crusaders. However, the surprise allowed the crusaders to deploy in the face of a smaller force than the entire coalition and limited the risk of being attacked during the deployment.

Previous studies have claimed that Kerbogha’s failure to attack the crusaders while they were deploying led to the Muslims’ defeat.Footnote155 France specifies that it was the dispersal of Muslim troops around the city of Antioch that made it impossible for them to attack the crusaders in time, arguing that this was a decisive mistake.Footnote156 It was not a mistake, however, as, in order to efficiently besiege Antioch, the coalition had to be split into multiple contingents blockading the city’s gates.Footnote157 The 2,000 men of the coalition guarding Bridge Gate were the only forces available, and were shown unable to oppose the 20,000–30,000 sallying crusaders.Footnote158 The surprise of the sally and the dispersal of the coalition were decisive in the crusaders’ success, but not Kerbogha’s mistake. By that point, the surprise of the sally denied Kerbogha the possibility to attack the crusaders during their deployment, adding to the uncertainty that troops would commit sufficiently to the battle, and placing Kerbogha in an uncomfortable position.

The crusaders succeeded in deploying their army before the Muslims could attack them, so Kerbogha decided to adopt a risky but necessary battle plan to defeat the fully deployed crusading army. He decided to manoeuvre his forces to encircle the crusaders and cut off their potential retreat.Footnote159 He would command a main corps, while a likely smaller second corps would attack the rear of the crusading army.Footnote160 The battle can be divided into three phases: the attack on the crusaders’ rear by the second corps, the first shock encounter between the two forces leading to the flight of the remaining Turkmen, and, finally, the defeat of the last standing amīrs. First, the second corps was sent against the rear of the crusaders, but the former rapidly broke and fled showing the troops’ lack of commitment to the battle.Footnote161 This lack of commitment is especially well described by Ibn al-Athīr who wrote that “The Franks […] thought that it was a trick, since there had been no battle such as to cause a flight”.Footnote162 Second, the main corps engaged with the crusaders, but Turkmen fled, arguably disorganising other lines behind them.Footnote163 This was further proof of the troops overall lack of commitment, apart from the contingents that stayed for the third and final phase of the battle. Third, the crusaders charged the remaining coalition forces and defeated them. Most Muslim cavalrymen were able to withdraw, but the infantrymen were slaughtered.Footnote164 Zouache argues that the battle plan has been unfairly criticised.Footnote165 In fact, the battle plan was wise,Footnote166 and there was no alternative plan capable of achieving the complete destruction of the crusading army.Footnote167 However, while the tactic was appropriate in theory, the insufficient commitment of the amīrs and the soldiers meant that the coalition had little chance to win the battle.Footnote168

The numerical advantage of the coalition over the crusaders needs to be discussed as it evolved during each of the battle phases. The coalition’s relative numerical advantage disappeared by the end of the battle’s first phase. The situation deteriorated further during the second phase, when most of the Turkmen and amīrs fled. How many soldiers did the coalition have left by the beginning of the third phase? Narratives of the First Crusade do not offer information on the evolution of the sizes of both armies, either at the start or during the third phase of the battle. Instead they provide information on which contingents were still on the battlefield. Therefore, it is possible to deduce the remaining size of both armies by looking at how many troops each contingent could have numbered using the studies of both Morton and Zouache, which provide average army size per principality from the late eleventh and twelfth centuries. Only Janāḥ al-Dawla (Homs), Kerbogha (Mosul) and Suqmān ibn Artuq’s (Jerusalem) ʿasākir were left in addition to the muṭṭawwiʿa.Footnote169 Adding to Kerbogha’s 4,000–8,000 cavalry, Janāḥ al-Dawla’s ʿaskar numbered a few hundred cavalry.Footnote170 The size of Suqmān’s contingent is harder to estimate since no estimates of his forces while he was governing Jerusalem are known. Only later Artuqid forces were known when they ruled in the Jazīra. It is likely his force was stronger than Janāḥ al-Dawla’s, maybe by up to 1,000 cavalrymen.Footnote171 These contingents stood alongside ill-trained and ill-disciplined muṭṭawwiʿa.Footnote172 This means that, by the third phase of the battle, the coalition retained a force of 6,000–8,000 cavalry and around 10,000–15,000 infantry and faced 20,000–30,000 crusaders – minus the crusaders’ arguably minor battle casualties. In addition to their advantages in both numbers and quality, the crusaders’ morale was increased by having routed major portions of the coalition’s forces and the coalition had suffered a major blow to morale. By the beginning of the third phase, the coalition was already lost.

Conclusion

Kerbogha has traditionally been blamed in the literature for his supposedly poor decisions, with an emphasis on the crusaders’ victory against all odds, but a second reading of the evidence is possible. The argument made here is that the Muslim defeat ultimately resulted from the failure of the siege of Edessa, which led to the inability of the coalition to overcome its structural weaknesses. The lack of booty added to deep rivalries between a heterogeneous force and led the coalition to its self-destruction by desertions and, therefore, to the Muslim inability to perform properly during the Battle of Bridge Gate on 28 June 1098. The course of action followed by Kerbogha during the campaign would arguably have been adequate to achieve victory had the siege of Edessa succeeded. It appears unlikely that another commander would have performed better.

Five major factors influence the outcome of a battle: commitment, cohesion between units, battle experience, numbers, and logistics. The crusaders lacked both supplies and horses, so the coalition had a certain logistical advantage for the battle. The numerical factor is by far the least decisive as the overall quality of troops is more relevant. While the Muslim coalition had a huge numerical advantage at the start of the campaign, this had massively reduced by the start of the battle and likely reversed during the third phase of the battle, as argued above. It is therefore uncertain whether the Muslim coalition still had a real numerical advantage by the start of the battle. The remaining three factors, which are also likely the most important, were all in favour of the crusaders. In fact, the crusaders had learned to fight together as a cohesive unit during the expedition and the first siege of Antioch. Adding to prior experiences of war, they had become battle-hardened troops during the long campaign that started in 1096. Finally, they fully committed to the battle, while the Muslim troops’ speedy escape during the first two phases of the battle demonstrated their lack of commitment. Consequently, Kerbogha has been unfairly criticized, as the crusaders’ victory at the Battle of Bridge Gate was far from miraculous.

The failure of the 1098 campaign is, in fact, part of a larger phenomenon as successive Muslim coalitions similarly failed, such as those of Sharaf al-Dawla Mawdūd (r. 1109–1113) in 1110, 1111, and 1113. Another defeated coalition – led by Bursuq ibn Bursuq (d. 1116–1117) – was defeated at Tell Danith in 1115. The constant failure of the Muslim coalesced forces in the early decades of the Frankish presence in the Levant suggests another reading than the repeated individual incompetence of their commanders. Rather, Muslim combined forces suffered from both a structural failure of their military organisation, arising from overreliance on Turkmen auxiliaries, and unbridgeable rivalries between the commanders of their regular forces.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Carol Sweetenham, “When the Saints Go Marching In: The Memory of the Miraculous in the Sources for the First Crusade”, in The Crusades: History and Memory. Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East, Odense, 27 June – 1 July 2016, volumes I–II, eds. Kurt Villads Jensen and Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen (Turnhout: Brepols, 2021), II: 55–75, p. 57.

2 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana: History of the Journey to Jerusalem, ed. and trans. Susan B. Edgington (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 264–7; Fulcher of Chartres, “Historia Iherosolymitana gesta Francorum Iherusalem peregrinantium”, in Recueil des historiens des croisades, historiens occidentaux, volumes I–V (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1866), III: 311–485, pp. 345–6; Matthew of Edessa, Matthew of Edessa’s Chronicle, ed. and trans. Robert Bedrosian, volumes I–III (Los Angeles: Sophene Books, 2017), II: 248–9; William of Tyre, Chronicon, ed. Robert B. C. Huygens (Turnhout: Brepols: 2013), pp. 289–90; Monique Amouroux-Mourad, Le comté d’Édesse, 1098–1150 (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1988), p. 61; Gregory D. Bell, Logistics of the First Crusade: Acquiring Supplies amid Chaos (London: Lexington Books, 2020), p. 143; John France, “The Fall of Antioch during the First Crusade”, in Dei Gesta per Francos: Etudes Sur les croisades dédiées à Jean Richard / Crusade Studies in Honour of Jean Richard (Farnham: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 13–20, esp. 19; idem, Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 259–60; Yuval N. Harari, Special Operations in the Age of Chivalry, 1100–1500 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), p. 62; Hans E. Mayer, The Crusades (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 52.

3 Abū l-Fidāʾ, “Résumé de l’histoire des croisades tiré des annales d’Abou ’l-Fedâ”, Recueil des historiens des croisades, historiens orientaux, ed. and trans. William de Slane, volumes I–V (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1872), I: 3; Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī l-taʾrīkh, ed. Carl Johan Tornberg, volumes I–XII (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1965–1967), X: p. 276; Kamāl al-Dīn Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab min tārīkh Ḥalab, ed. Khalīl al-Manṣūr (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 1996), pp. 238–9.

4 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 286–7; Anna Comnena, Alexiade, trans. Bernard Leib (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2006), p. 466; Bar Hebraeus, La chronographie de Bar Hebraeus, trans. Philippe Talon, volumes I–III (Fernelmont, 2013), II: 2; Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, in Recueil des historiens des croisades, historiens occidentaux, volumes I–V (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1879), IV: p. 190; Gesta Francorum : Histoire anonyme de la première croisade, ed. and trans. Louis Brehier (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2021), p. 114; Jacopo Doria, “Regni Iherosolymitani brevis historia”, in Fonti per la storia d’Italia, ed. L.T. Belgrano and C. Imperiale di Sant’Angelo, volumes I-CXVIII (Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1890–1901), XI: 106; La chanson d’Antioche: Chanson de geste du dernier quart du XIIe siècle, ed. and trans. Bernard Guidot (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2011), pp. 728–32; Michael the Syrian, Chronique de Michel Le Syrien, patriarche jacobite d’Antioche (1166–1199), trans. Jean-Baptiste Chabot (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1905), p. 184; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano Itinere, ed. John Hugh Hill and Laurita L. Hill (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1977), p. 90; Ralph of Caen, “Gesta Tancredi in expeditione Hierosolymitana”, in Recueil des historiens des croisades, historiens occidentaux, volumes I–V (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1866), III: 599–716, p. 658; Raymond of Aguilers, Le “liber” de Raymond d’Aguilers, ed. John H. Hill and Laurita L. Hill (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1969), p. 66; Robert the Monk, The Historia Iehrosolimitana of Robert the Monk, ed. Damien Kempf and Marcus G. Bull (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 58–9; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 307; Thomas Asbridge, The First Crusade: A New History. The Roots of Conflict between Christianity and Islam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 211–13; France, Victory, 270–71; Jonathan Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (London: Continuum, 2009), p. 59; Randall Rogers, Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1997), p. 65; Jay Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse (New York: Basic Books, 2011), p. 210; James Titterton, Deception in Medieval Warfare: Trickery and Cunning in the Central Middle Ages (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2022), p. 86.

5 James Wilson, “The ‘ʿasākir al-Shām’: Medieval Arabic Historiography of the Siege, Capture and Battle of Antioch during the First Crusade 490–491/1097–1098”, Al-Masāq 33/3 (2021): 300–36, pp. 304–6.

6 Ibid., 302–3.

7 Ibn al-Qalānisī, History of Damascus, 363–555 a.h., by Ibn al Qalânisi from the Bodleian Ms. Hunt. 125, Being a Continuation of the History of Hilâl al-Sâbi, ed. Henry F. Amedroz (Leiden: Brill, 1908), p. 136; Wilson, “ʿasākir al-Shām”, 304.

8 Abū l-Fidā, “Résumé”, 3–4; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 238–41; Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī l-taʾrīkh, X: 276–8; Ibn al-Dhahabī, Taʾrīkh al-islām wa-wafayāt al-mashāhīr wa-l-aʿlām, ed. ʿUmar Tadmūrī, volumes I–LIII (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, 2003), X: pp. 666–7; al-Nuwayrī, Nihāyat al-ʿarab fī funūn al-adab, ed. Mufīd Qumayḥa, volumes I–XXXIV (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2004), XXVIII: 160–4; Sibṭ Ibn al-Jawzī, Mirʾāt al-zamān fī taʾrīkh al-aʿyān, ed. Kāmil S. al-Jabūrī, volumes I–XXIII (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2013), XIII: pp. 258–60.

9 Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 238–41.

10 Anne-Marie Eddé, “Kamāl al-Dīn ʿUmar Ibn al-ʿAdīm”, in Medieval Muslim Historians and the Franks in the Levant, ed. Alex Mallett (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 109–35, esp. 129–31, 134; Françoise Micheau, “Ibn al-Athīr”, in Medieval Muslim Historians and the Franks in the Levant, ed. Alex Mallett (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 52–83, esp. 67.

11 Alex Mallett, Medieval Muslim Historians and the Franks in the Levant (Leiden: Brill, 2015), p. 1.

12 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 286–337; Baldric of Bourgueil, The Historia Ierosolimitana of Baldric of Bourgueil, ed. Steven Biddlecombe (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2014), pp. 60–86; Fulcher of Chartres, “Historia Iherosolymitana”, 344–51; Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, 189–208; Gesta Francorum, 102, 110–60; Jacopo Doria, “Regni Iherosolymitani”, 106–9; Chanson d’Antioche, 718–962; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano, 88–113; Ralph of Caen, “Gesta Tancredi”, 658–72; Raymond of Aguilers, Le “liber”, 66–83; Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, 58–79; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 307–40.

13 Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, ix.

14 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, xxi; James Naus, “The Historia Iherosolimitana of Robert the Monk and the Coronation of Louis VI”, in Writing the Early Crusades: Text, Transmission and Memory, ed. Marcus Bull and Damien Kempf (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2018), pp. 105–15, esp. 105.

15 Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, xvii.

16 Elizabeth Lapina, “Crusader Chronicles”, in The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades, ed. Anthony Bale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 11–24, esp. 16. On the Gesta Francorum as a source and influence on later texts, see Baldric of Bourgueil, Historia Ierosolimitana, ix–xxiv; Baldric of Bourgueil, Baldric of Bourgueil “History of the Jerusalemites”: A Translation of the Historia Ierosolimitana, trans. Susan B. Edgington (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2020), pp. 11–28; The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades, ed. Anthony Bale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019); Gesta Francorum, i–xxxvi; Writing the Early Crusades: Text, Transmission and Memory, ed. Marcus Bull and Damien Kempf (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2018); Rosalind Hill, Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. ix–xlii; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano, 7–18; Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, ix–xvi; Robert the Monk, Robert the Monk’s History of the First Crusade: Historia Iherosolimitana, trans. Carol Sweetenham (Farnham: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 12–27.

17 Bull and Kempf, Writing the Early Crusades, p. 8.

18 Raymond of Aguilers, Le “liber”, 88–114; Ralph of Caen, “Gesta Tancredi”, 658–72.

19 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 248–73; Fulcher of Chartres, “Historia Iherosolymitana”, 345–6; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 289–91.

20 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, xxi.

21 Ibid., xxviii.

22 Ibid., xxi.

23 Ibid., xxii–xxiv, xxvi–xxvii.

24 Marianne Ailes, “The Chanson de Geste”, in The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades, ed. Anthony Bale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 25–38, esp. 32; Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, xxvii; Chanson d’Antioche, 108–10, 129–30.

25 Abbès Zouache, Armées et combats en Syrie (491/1098–569/1174): Analyse comparée des chroniques médiévales latines et arabes (Damascus: Institut Français du Proche-Orient, 2008), p. 162.

26 Robert the Monk, Robert the Monk’s History, 39; Carol Sweetenham, “What Really Happened to Eurvin de Créel’s Donkey? Anecdotes in Sources for the First Crusade”, in Writing the Early Crusades: Text, Transmission and Memory, ed. Marcus Bull and Damien Kempf (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2018), pp. 75–88, esp. 84, 88; Zouache, Armées, 163.

27 Chanson d’Antioche, 614–24; Zouache, Armées, 84–5, 161.

28 Anonymi auctoris chronicon AD A.C. 1234 peritens II, trans. Albert Abouna (Leuven: Peeters, 1974), pp. 42–3; Matthew of Edessa, Chronicle, II: 248–9.

29 Anna Comnena, Alexiade, 462–7, 473–5; Bar Hebraeus, Chronographie, II: 2; Michael the Syrian, Chronique, 184.

30 Jean-Baptiste Mailly, L’esprit des croisades ou histoire politique et militaire des guerres entreprises, par les chrétiens contre les mahométans, pour le recouvrement de la Terre-Sainte, pendant les XIe, XIIe, & XIIIe siècles, volumes I–IV (Paris: Moutard, 1780), IV: 218; Jean Richard, ‘De Jean-Baptiste Mailly à Joseph-François Michaud: Un moment de l’historiographie des croisades (1774–1841)’, Crusades 1 (2002), 1–12, p. 2.

31 Charles Mills, The History of the Crusades, for the Recovery and Possession of the Holy Land, volumes I–II (London: Longman, 1821), I: 198–9.

32 Mailly, L’esprit des croisades, IV: 287; Charles Oman, A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages: 378–1278 AD (London: Greenhill Books, 1998), pp. 287–8.

33 René Grousset, Histoire des croisades et du royaume Franc de Jérusalem, volumes I–VIII (Paris: Tallandier, 1981), I: 243; Joshua Prawer, Histoire du royaume latin de Jérusalem, volumes I–II (Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 2001), I: 212; Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, volumes I–III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951), I: 210, 236–7.

34 Taef El-Azhari, Zengi and the Muslim Response to the Crusades: The Politics of Jihad (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), p. 93.; Claude Cahen, “The Turkish Invasion: The Selchükids”, in A History of the Crusades, volumes I–VI, ed. Marshall W. Baldwin (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), I: 169; Paul M. Cobb, The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 90–3; Peter Frankopan, The First Crusade: The Call from the East (London: Bodley Head, 2012), p. 160; Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp. 56–9; Conor Kostick, The Siege of Jerusalem: Crusade and Conquest in 1099 (London: Continuum, 2011), p. 40; Nicholas Morton, Encountering Islam on the First Crusade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 137; Jonathan Philips, The Crusades, 1095–1204, 2nd edition (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014), pp. 29–30; Riley-Smith, First Crusade, 38; Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 205; Raymond C. Smail, Crusading Warfare, 1097–1193, 2nd edition with a new bibliographical introduction by Christopher Marshall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 27; Georgios Theotokis, Bohemond of Taranto: Crusader and Conqueror (Huddersfield: Pen and Sword Military, 2020), pp. 111–15.

35 Asbridge, First Crusade, 236–8; Bell, Logistics, 140; Claude Cahen, La Syrie du Nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche (Beyrouth: Institut Français de Damas, 1940), pp. 217–18; France “Fall of Antioch”, 19; France, Victory, 260, 294; Harari, Special Operations, 62; Mayer, Crusades, 52.

36 Harari, Special Operations, 62.

37 Susan B. Edgington, Baldwin I of Jerusalem 1100–1118 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), pp. 51–2; Amin Maalouf, Les croisades vues par les Arabes (Paris: Magellan, 2001), p. 46; Mailly, L’esprit des croisades, IV: 218; Wilson, “ʿasākir al-Shām”, 314.

38 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 266–7; Fulcher of Chartres, “Historia Iherosolymitana”, 345–6; Chanson d’Antioche, 620–2; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 289–90; Wilson, “ʿasākir al-Shām”, 317.

39 Cahen, La Syrie du Nord, 217–8; Maalouf, Croisades, 51–2; Mailly, L’esprit des croisades, IV: 218; Zoé Oldenbourg, The Crusades, trans. Anne Carter (New York: Pantheon Books, 1966), p. 110; Oman, History of the Art of War, 287–8.

40 France, Victory, 294.

41 Kostick, Siege of Jerusalem, 43; Morton, Encountering Islam, 160; Smail, Crusading Warfare, 26.

42 Grousset, Histoire des croisades, I: 250; Hillenbrand, Crusades, 58–9; Michael A. Köhler, Alliances and Treaties Between Frankish and Muslim Rulers in the Middle East: Cross-Cultural Diplomacy in the Period of the Crusades, ed. by Konrad Hirschler, trans. by Peter M. Holt (Leiden: Brill, 2013), pp. 93–4; Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 208; Runciman, History of the Crusades, I: 246, 248; Steven Runciman, “The First Crusade: Antioch to Ascalon”, in A History of the Crusades, ed. Marshall W. Baldwin, volumes I–VI (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), I: 322; Sweetenham, “When the Saints Go Marching In”, 57.

43 France, Victory, 293.

44 Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 225; Runciman, History of the Crusades, I: 248; Zouache, Armées, 277

45 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 324–7; Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, 198; Gesta Francorum, 138; Jacopo Doria, “Regni Iherosolymitani”, 106; Chanson d’Antioche, 866.

46 John France, “Moving to the Goal, June 1098 – July 1099”, in Jerusalem the Golden: The Origins and Impact of the First Crusade, ed. Susan B. Edgington and Luis Garcia-Guijarro (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), pp. 133–49, esp. 133; Morton, Encountering Islam, 160; Oldenbourg, Crusades, 110; Oman, History of the Art of War, 288, Henri Pigaillem, Dictionnaire encyclopédique des batailles de l’antiquité à l’an 2000 (Paris: Economica, 2019), p. 59; Sweetenham, “When the Saints Go Marching In”, 57.

47 Cahen, La Syrie du Nord, 217–18; Grousset, Histoire des croisades, I: 250; Maalouf, Croisades, 50; Oman, History of the Art of War, 287; Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 208; Runciman, “First Crusade”, 322.

48 Hillenbrand, Crusades, 58–9.

49 Köhler, Alliances, 93–4.

50 Runciman, History of the Crusades, I: 210, 236–7.

51 Ibid., 246.

52 Ibid., 248.

53 Runciman, “First Crusade”, 316.

54 Heinrich Hagenmeyer, “Chronologie de la première croisade”, Revue de l’Orient Latin 7 (1899): 275–339, 430–503, pp. 280–1.

55 Edgington, Baldwin I, 52.

56 Maalouf, Croisades, 45.

57 Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 208.

58 Runciman, “First Crusade”, 316.

59 Amouroux-Mourad, Édesse, 61; Bell, Logistics, 143; France, “Fall of Antioch”, 19; France, Victory, 259; Grousset, Histoire des croisades, I: 243; Hagenmeyer, “Chronologie”,. 280–1; Harari, Special Operations, 62.

60 Edgington, Baldwin I, 52.

61 Thomas Asbridge, The Creation of the Principality of Antioch, 1098–1130 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2000), p. 26; Amouroux-Mourad, Édesse, 61; Bell, Logistics, 143; France, “Fall of Antioch”, 19; France, Victory, 259, 270–1; Grousset, Histoire des croisades, I: 243; Hagenmeyer, “Chronologie”, 280–1; Harari, Special Operations, 62.

62 John Haldon, “Roads and Communications in the Byzantine Empire: Wagons, Horses and Supplies”, in Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 30 September to 4 October 2002, ed. John H. Pryor (Farnham: Routledge, 2006), pp. 131–58, esp. 141; John H. Pryor, “Introduction: Modelling Bohemond’s March to Thessalonikē”, in Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 30 September to 4 October 2002, ed. John H. Pryor (Farnham: Routledge, 2006), pp. 2–24, esp. 9.

63 Haldon, “Roads and Communications”, 141, 145; John H. Pryor, “Digest”, in Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 30 September to 4 October 2002, ed. John H. Pryor (Farnham: Routledge, 2006), pp. 279–92, esp. 280–1.

64 Bernard S. Bachrach, “Crusader Logistics: From Victory at Nicaea to Resupply at Dorylaion”, in Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 30 September to 4 October 2002, ed. John H. Pryor (Farnham: Routlegde, 2006), pp. 43–62, esp. 43.

65 Haldon, “Roads and Communications”, 142.

66 “He slowed down the journey for many days because of the loads on his vehicles and the burdens on the pack animals and camels” in Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 264–5.

67 Ibn Jubayr, The Travels of Ibn Jubayr, ed. William Wright and M. J. de Goeje (Leiden: Brill, 1907), pp. 238–41.

68 Zouache, Armées, 647.

69 “Assembling at the Castle of Sooch”, in Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 264–5; France, Victory, 260.

70 Harari, Special Operations, 62; Runciman, “First Crusade”, 316.

71 Maalouf, Croisades, 45.

72 Quoted from Fulcher of Chartres, “Historia Iherosolymitana”, 345–6; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 290; Amouroux-Mourad, Édesse, 61; Bell, Logistics, 143; France, “Fall of Antioch”, 19; France, Victory, 259; Harari, Special Operations, 62; Mayer, Crusades, 52.

73 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 266–7.

74 France, Victory, 259.

75 Matthew of Edessa, Chronicle, II: 248–9.

76 Christopher MacEvitt, “The Chronicle of Matthew of Edessa: Apocalypse, the First Crusade, and the Armenian diaspora”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61 (2007): 157–81, p. 164.

77 Edgington, Baldwin I, 52.

78 Matthew of Edessa, Chronicle, II: 248–9.

79 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 264–5; Chanson d’Antioche, 622.

80 Anonymi auctoris chronicon, 42–3.

81 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 266–7; Chanson d’Antioche, 622; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 238–9.

82 Abū l-Fidāʾ, “Résumé”, 3; Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī l-taʾrīkh, X: 276; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 238–9; Cobb, Race for Paradise, 90.

83 Cahen, La Syrie du Nord, 217.

84 Georges Tchalenko, Villages antiques de la Syrie du nord: Le massif du Bélus à l’époque romaine, volumes I–III (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1953), I: 88–9, fig. XXXVII; Jean-Charles Batly, “Voies romaines et aqueduc de l’Oronte”, Syria 4 (2016): 229–39, fig. 7, https://journals.openedition.org/syria/4925.

85 Bar Hebraeus, Chronographie, II: 2; Michael the Syrian, Chronique, 184; France, Victory, 261.

86 Anonymi auctoris chronicon, 43; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 240; Not mentioning Artah, but saying the army went close to Aleppo, consequently following the Artah route; Gesta Francorum, 125; Cobb, Race for Paradise, 92.

87 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 286–9; Chanson d’Antioche, 728–32; Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, 58–9; Asbridge, First Crusade, 211–13; France, Victory, 270–1; Riley-Smith, First Crusade, 65; Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven, 210; Titterton, Deception, 86.

88 Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, 190; Gesta Francorum, 114; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 240; Chanson d’Antioche, 632; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano, 90; Asbridge, Antioch, 26; Asbridge, First Crusade, 214; Cobb, Race for Paradise, 92; France, Victory, 271.

89 Baldric of Bourgueil, Historia Ierosolimitana, 61–2; Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, 190; Gesta Francorum, pp. 112–4; Ibn al-ʿAdīm, Zubdat al-ḥalab, 240; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano, 89–91; Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, 59–60; Asbridge, First Crusade, 215; France, Victory, 269; Cobb, Race for Paradise, 92.

90 Albert of Aachen, Historia Hierosolymitana, 286–7, 290–1; Anna Comnena, Alexiade, 466; Bar Hebraeus, Chronographie, II: 2; Guibert of Nogent, “Gesta dei per Francos”, 190; Gesta Francorum, 114; Jacopo Doria, “Regni Iherosolymitani”, 106; Matthew of Edessa, Chronicle, II: 250–1; Michael the Syrian, Chronique, 184; Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano, 90; Ralph of Caen, “Gesta Tancredi”, 658; Raymond of Aguilers, Le “liber”, 66; Robert the Monk, Historia Iehrosolimitana, 58; William of Tyre, Chronicon, 307; France, Victory, 271.

91 Harari, Special Operations, 62.

92 Zouache, Armées, 375–6; Runciman, “First Crusade”, 316.

93 A list of lords can be found in prior studies: France Victory, 260–1; Wilson, “ʿasākir al-Shām”, 312–13.

94 Asbridge, First Crusade, 204; Bell, Logistics, 140, 143; Cobb, Race for Paradise, 92–3; Mayer, Crusades, 52; Köhler, Alliances, 7, 20.