Abstract

This discussion posits that the work of the Cree artist Kent Monkman offers a unique and potent contribution to the project of decolonisation rooted in an Indigenised context. Focusing on the parodic, art historical interventions of his artistic alter ego Miss Chief, it explores his art in view of ‘transmotion’, a crucial but often overlooked aspect of postindian tricksterism outlined by the Anishinaabe author Gerald Vizenor, as well as the postindian approach to translation. His approach will be considered against the foil of the project of decolonising proposed by the sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos, framed in terms of a post-abyssal ecology of knowledges, with a focus on the notion of intercultural translation and the motion of the swerve he proposes. The discussion concludes by positing the Vizenorian figure of the mixedblood, urban earthdiver as figurehead for a decolonial era of the future, supplanting the urban flâneur of modernity.

This discussion explores the work of the Cree artist Kent Monkman, which challenges conventional representations of Native American Indian culture conceived as ‘traditional’, taking parodic aim at the canons of art history, while reimagining its tropes and conventions often through the time-travelling, gender-bending and stereotype-busting escapades of his artistic alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, or ‘Miss Chief’ for short. The proposition is that it offers a unique and potent contribution to the project of decolonising, and this will be examined through the lens of ‘transmotion’. This conception was introduced by the Anishinaabe scholar and author Gerald Vizenor, who characterises it as a ‘native connotation’.Footnote1 The author intentionally refrains from providing a definitive, clear-cut definition of the idea, as doing so would pin its meaning down and thus misrepresent the fluid nature of tribal storytelling, which he is seeking to reference. It stands for a way of doing, a stance, which he associates with Native American Indian cultures prior to what he calls their ‘museumisation’ by settler colonialism, when the ‘causal narratives of museum consciousness’ captured Indigenised peoples as ‘Indian’,Footnote2 imprisoning them ‘by words and stereotypes’.Footnote3 They were thus turned into ‘an “objective” collection of consumable cultural artifacts’,Footnote4 and, cast in the image of the past, figured as ‘animated museums’.Footnote5

The notion of ‘transmotion’, moreover, is closely associated with the figure of the postindian storier and trickster. Vizenor created this figure as a counter to the ‘occidental invention’Footnote6 of the traditional ‘Indian’, which he views as a burden that postindians must shed to assert their presence in the here and now and in order to stake their claim to the future. As Vizenor states: ‘The point is that we are long past the colonial invention of the indian [sic]. We come after the invention, and we are postindians.’Footnote7 The suggestion, furthermore, is that the ‘sense of native motion and… active presence’Footnote8 connoted by transmotion constitutes a significant yet overlooked aspect of the art of Kent Monkman, even though it has frequently been associated with the Vizenorian figure of the postindian,Footnote9 which is argued to be fundamental to the contribution his art makes to debates around decolonising.

To develop this argument, salient features of Monkman’s art will be explored and situated in relation to the figure of the postindian trickster, the Vizenorian notion of transmotion and the postindian approach to cultural translation as laid out by Vizenor, examining the ways in which these ideas apply to Monkman’s work. To establish the significance of these ideas for debates around the decolonial, they will, moreover, be contextualised utilising the approach to decolonising of sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos, who proposes an ecology of knowledges envisioned as a post-abyssal paradigm premised on a both/and in contrast to the alterising either/or of the colonial. Santos has been chosen as a point of comparison because he, likewise, emphasises the significance of translation for the project of decolonising. He also thematises motion in this context, introducing the swerve as an indicative movement of the post-abyssal.

Broadly, the discussion is interested in the horizons of possibility opened up by Monkman’s work. It also introduces the Vizenorian figure of the earthdiver, which will be proposed as emblematic for a postindian, post-abyssal, decolonial era of the future, relegating the ‘botanising’ Baudelairean flâneur representative of modernity/coloniality to the annals of history.

Colonial Legacies and the Geopolitics of Knowledge

Before embarking on the discussion itself, it is essential to provide contextual remarks to position it within the context of art history’s colonial legacies and geopolitics of knowledge. A point of note is that the pitfalls of reducing what has been dubbed the global turn in art history to an additive exercise have been well rehearsed and do not need repeating here. However, it is important to recognise that while the increased inclusion of artists from diverse backgrounds in the artworld and the canons of art are positive steps, this frequently falls short of addressing the fundamental structures of exclusion. For the most part, therefore, the underlying issues and colonial legacies of art and its histories remain unaddressed; that is, the push for greater diversity in the visual arts frequently operates on Eurocentric terms since approaches to indigeneity remain rooted in colonial notions of authenticity and tradition. Moreover, as the issue of decolonising gains momentum, concerns about tokenism and the reinscription of the very traits and systemic violences critiqued by decolonial approaches are being raised.

One of the central concerns at play here is the dilemma of addressing decolonisation while employing the very languages and concepts that have been shaped by the paradigm to be dismantled – a paradox that also applies to the present discussion. This challenge is one that both Monkman and Vizenor grapple with in their work and to which Vizenor responds with his postindian approach to translation and the notion of transmotion.

In other words, the concerns of this discussion are more than an academic exercise. They are directly related to the question of how to write a discussion such as the present one without rehearsing the very tropes one seeks to unhinge, that is, without inadvertently reinscribing them through the use of professional methods, concepts and approaches that are deeply influenced by colonial legacies; simply providing new content and subject matter in the guise of novel fillings and flavours for well-established colonial brands of chocolate, to use a consumptive, culinary metaphor rooted in a colonial, extractive paradigm.

Moreover, given art history’s close association with the histories of coloniality and the legacies of appropriation of art of the Global North, it is crucial to acknowledge that engaging with the work of an Indigenised artist in the contexts of academia is inherently complex – and even more so for a white-bodied European art historian hailing from the ‘north of the North’, as in my case; one situated at the intersection of academia, art history and white privilege in the Global North. As developed by indigenous rights advocate and educational theorist Vanessa Andreotti, this position is metaphorically described as the ‘penthouse’ of the house of modernity, signifying a position of privilege marked by choices, resources, protections and the security to critique its structures from within.Footnote10

My white body privilege and the multiple legacies of colonialism that have shaped my profession and my world therefore need to be named here, with a particular emphasis on the academy which, as Santos has pointed out, is fundamentally involved in converting ‘the scientific knowledge developed in the Global North into the hegemonic way of representing the world’.Footnote11 In other words, scholarly knowledge has been used as justification for domination and rampant exploitation in ways that include cultural appropriation, epistemic violence and the harmful effects of misrepresentations, which are not recognised as such and are widely seen as ‘truth’. In the words of the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano, ‘The tragedy here is that we all have been led, knowingly or not, willingly or not, to see and to accept that image as our own reality’.Footnote12 He likens this epistemic condition to a ‘distorting mirror’ with a Eurocentric bias, which offers a partial view of ‘reality’ that is mistaken for the full picture, and considers the recognition of this distortion to be the first step towards opening up decolonial horizons of possibility.

A further, crucial acknowledgment to note is that there can be no place of purity and innocence from which to speak. As the Columbian-American anthropologist Arturo Escobar points out, placing oneself ‘outside of’ equates to being ‘complicit with a modernist logic of alterization’.Footnote13 Such a stance, he notes, therefore needs to be recognised as a deeply engrained stance of modernity and its dark underbelly of coloniality, which are two sides of the same coin as recognised in the term modernity/coloniality.Footnote14 It is therefore important to acknowledge that the context for this discussion fundamentally is one of immersion, complicity and the shared condition of dwelling in the house of modernity. This holds true regardless of one’s situatedness regarding colonialism’s histories, power structures and exploitative, extractive machinations, while fully recognising that the terrible burdens of colonialism continue to be extremely and unjustifiably unequally borne around the globe.

Who is Miss Chief?

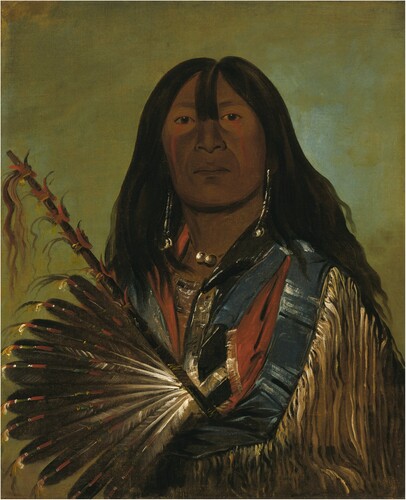

As Monkman informs us, he created the figure of Miss Chief in response to his exploration of art history, in particular the work of the nineteenth-century American artist George Catlin, who made a name for himself by documenting the ‘vanishing Indian’ in paintings such as Shón-ka, The Dog, Chief of the Bad Arrow Points Band (1832). Catlin displayed his work in travelling shows throughout the United States and also took it across the Atlantic in 1839, along with a troupe of Indigenised performers.

George Catlin, Shón-ka, The Dog, Chief of the Bad Arrow Points Band Western Sioux/Lakota, 1832, oil on canvas, 73.7 × 60.9 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs Joseph Harrison, Jr, Creative Commons Zero license

Catlin’s work and his negative reaction to the gender fluidity he witnessed among the Indigenised peoples of North America galvanised Monkman to create his artistic alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testicle, or ‘Miss Chief’, to reverse the colonial gaze.Footnote15 Her name, a play on ‘mischief’, the ego, egotism and being egotistical, is an indication of her brief, which re-envisions Two Spirit traditions for the contemporary and upends tropes of Native American Indian culture conceived as ‘traditional’ and ‘a thing of the past’. Miss Chief also takes issue with cultural constructs such as the artistic genius, and with the highly gendered and exclusionary attitude towards creativity which informs it. Whether armed with a Louis Vuitton handbag and pink stilettos, dressed in a VIP nurse’s outfit, presented in the nude barely graced by a flowing scarf, or in a blazing, coquelicot red outfit that plays on the trope of red skin, Miss Chief readily undercuts any expectations of traditional Indianness served up, for example, in American westerns. She, moreover, takes poignant swipes at celebrated Western artists. Picasso, a particular focus of her attention, serves as an emblematic figure for the appropriative spirit of modern art in Monkman’s work.

Kent Monkman, Dance to Miss Chief, 2010, video, 04:49 minutes, colour, English and German with English Subtitles, An Urban Nation Production, image courtesy of the artist

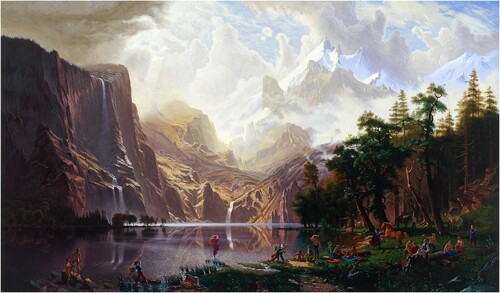

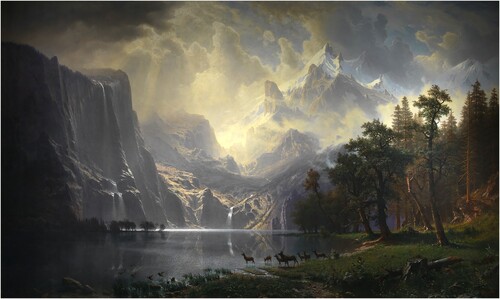

The chimeric figure of Miss Chief first made an appearance on canvas. An example here is the reworking of the genre of nineteenth-century American landscape painting as, for example, in Trappers of Men (2006), where Monkman re-envisages the painting Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains (1868) by the nineteenth-century American-German painter Albert Bierstadt. At first glance, Monkman’s image looks like a typical nineteenth-century American landscape painting. Such images are replete with sweeping vistas bathed in an otherworldly light, suggesting a quasi-biblical paradise devoid of people placed at the disposal of European settlers by divine providence. By the 1880s they had forged a national aesthetic, with cheap copies of such pictures decorating the walls of American homes, legitimating settler occupation of the land of the Indigenised through seemingly innocent depictions of North American scenery.Footnote16

Kent Monkman, Trappers of Men 2006, acrylic on canvas image, 262 × 415 × 9 cm, Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, Purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest, anonymous gift and gift of Dr Ian Hutchinson, image courtesy of the artist

On closer inspection, however, Trappers of Men reveals unruly narratives that upend a host of visual codes, art-historical tropes, expectations of gender normativity as well as stereotypes of Indians and cowboys: Monkman has restoried Bierstadt’s painting by inserting Indigenised peoples into the scene in ways that subvert the tropes of representing Indigenised people rehearsed, for example, in the work of Catlin, who did not portray Indigenised peoples on their native land – rather, he painted them like museal objects in a documentary mode devoid of context, presenting them decked out in feathers, beadwork and buckskin outfits, that is, in the visual trappings of the ‘traditional Indian’, who, as Vizenor highlights, was an invented figure.

Albert Bierstadt, Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, 1868, oil on canvas, 183 × 305 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Helen Huntington Hull, granddaughter of William Brown Dinsmore, who acquired the painting in 1873 for ‘The Locusts’, the family estate in Duchess County, New York, Creative Commons Zero licence

Monkman exposes the conceit of such representations in the left foreground of Trappers of Men, which shows the well-known nineteenth-century photographer Edward Curtis at work. Curtis, who like Catlin sought to capture ‘authentic Indians’, is known for his highly staged, ‘traditional’ images of Indigenised people presented as a ‘noble’ yet ‘doomed’ race. Research has shown that he did not shy away from providing the requisite props to do so, and Monkman spells this out in the painting, which shows two Native American Indian men about to pose for the photographer.Footnote17 One of them has a short, modern haircut that evidently needs to be disguised as he is holding a long-haired wig in his hands. It quite likely came from the open chest of traditional Indigenous accoutrements that is displayed behind Curtis. Monkman thus illustrates that the photographer provided his models with the means to conceal the signs of modernity, actively fashioning the Romantic myth of the noble and ‘vanishing’ Native American Indian that he, ostensibly, sought to document in his work.

Kent Monkman, Trappers of Men, detail, 2006, acrylic on canvas image, 262 × 415 × 9 cm, Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, Purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest, anonymous gift and gift of Dr Ian Hutchinson, image courtesy of the artist

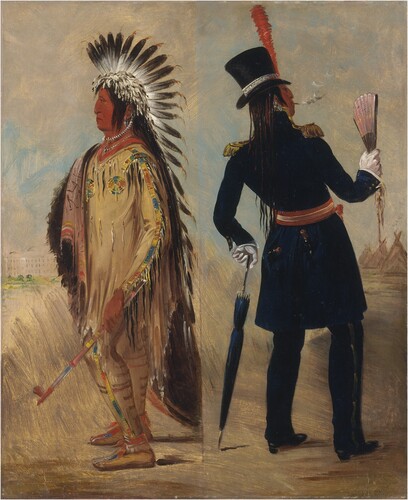

Catlin endorsed a similarly traditionalist view, rejecting any signs of Indian adaptation to modern life, which for him entailed a moral lesson, as he spells out in Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning from Washington (1837–1839). This painting contrasts the supposedly true and natural ‘Indian’ with the adulterated and hence, according to prevailing ideology, invariably crooked one, who wears a European outfit characterised by epaulettes, a top hat and an umbrella. Yet Catlin saw no issue with his own cultural cross-dressing, as demonstrated in George Catlin, a portrait by the American painter William Fisk, which shows him wearing a buckskin outfit without the slightest hint of self-consciousness or any sense of incongruity. Rather than diminishing his authenticity as painter of the vanishing ‘Indian’, his indigenised appearance, ironically, added to his credibility, evidencing the double standard prevalent in European art and culture that allowed Europeans to cross cultural boundaries and appropriate at will while similar moves by Indigenised and colonised peoples and artists were mocked as inauthentic and derivative.

George Catlin, James Ackerman, Wi-jun-jon. An Assinneboin Chief., n.d., hand-coloured lithograph on paper, 44.4 × 30.3 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr

William Fisk, George Catlin, 1849, oil on canvas, 158.8 × 133.4 × 7 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London, Smithsonian Institution; transfer from the Smithsonian American Art Museum; gift of Miss May C Kinney, Ernest C Kinney and Bradford Wickes, 1945, Creative Commons Zero license

It is not surprising, therefore, that Monkman takes aim at this double standard and has Miss Chief subvert it with panache in Trappers of Men. In this artwork she appears as a dazzling apparition walking on water with flowing blond hair. She is enveloped in a large, bright pink drape, dons poppy-red plateau heels and is showing off a muscular six-pack and a large extended male member. Monkman is thus sending up notions of authentic Indian identity and colonial gender normativity, subverting traditions of American landscape art and poking fun at the female nude in art history in a tour de force of stereotype busting.

Kent Monkman, Trappers of Men, detail, 2006, acrylic on canvas, image, 262 × 415 × 9 cm, Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, Purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest, anonymous gift and gift of Dr Ian Hutchinson, image courtesy of the artist

But Monkman does not limit Miss Chief’s interventions to landscape art. He soon has her step out of the image frame into the wider spheres of art and life, and acquire a quasi-authentic historical persona as a dancer in Catlin’s touring troupe; a career the artist explains with reference to the performance culture of Native American Indians and their presence in Wild West spectacles. Miss Chief’s relations with Catlin, moreover, are not as one might imagine. Deliberately undercutting expectations of colonial mastery, Miss Chiefs reveals herself as Catlin’s lover in a manner which makes clear that she is neither a coerced sex slave nor a disenfranchised concubine but an admiring disciple of his who delights in his paternal guidance. She, nonetheless, soon strikes out on her own, delighting in time-travelling adventures, which find her mixing with the centuries’ great and the good of European history and the history of art, such as Robin Hood and the painters David, Girodet, Ingres and Manet.

Undercutting expectations of a counter-hegemonic, critical take on the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Parisian artworld, Miss Chief perplexingly refers to these painters as her ‘dear friends’ in the video Casualties of Modernity (2015), which accompanies the multimedia installation with the same name.Footnote18 She also makes a subtle dig at established art-historical hierarchies of value and canonical narratives by not making a distinction between academic painters and the modern avant-garde art in this line-up.

Kent Monkman, Casualties of Modernity, 2015, mixed media installation, Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, photo of the installation at the BMO Project Room by Tony Hafkenscheid, image courtesy of the artist

In the video Miss Chief adopts the role of a VIP philanthropist inspired by Lady Di. She is visiting a hospital specialising in the care of ‘casualties of modern art’, among them works by Picasso, Giacometti, Malevich and Duchamp. One of the patients is a Cubist nude from Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907), who is lying in bed gasping for air and serves as the focus of the installation of which the video is a part. The video shows Miss Chief at her bedside holding her hand, aghast at the dismal state of the flattened, distorted and fractured female figure who is a prominent product of modern art’s Primitivist appropriation. As the scene spells out, the tables have now turned, and Miss Chief is no longer subject to modernity’s cultural projections. Rather, she plays with Primitivist tropes and the appropriation of Indigenised visualities by modern artists who believed that such cultures represented earlier stages of cultural development and that using such visual elements would revitalise European art. As the parodic setting of the ‘Hospital of Modern Art’ and the sorry state of Picasso’s Primitivist nude and other patients in this wing suggest, this strategy has clearly failed.

Kent Monkman, Casualties of Modernity, 2015, video still, Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, image courtesy of the artist

Monkman, however, not only critiques the conceit of this understanding but thoroughly unhinges it as Miss Chief continues to bust stereotypes while disallowing professions of victimhood. An example here is when the Doctor of Modern Art, who acts as her guide during the hospital visit, introduces the deceased body of Romanticism as the ‘first casualty of modernity’ and explains Romanticism’s demise in terms of having lost the balance between the two competing traditions of ‘art of ancient Greece’ and ‘ancient cultures discovered in the new world’,Footnote19 making reference to savages. Miss Chief, rather than deploring the misrepresentation of Indigenised peoples, as one might expect, responds to the doctor’s statement by professing her delight in the exotic status she enjoyed at this time and exclaims

Oh yes, I know a lot about the Romantic savage. Europeans projected their fantasies onto us. But I have to admit, I absolutely thrived on the attention. Oh, how I was the toast of Europe following my mentor and lover George Catlin in Paris and London.Footnote20

Miss Chief and the Postindian MixedBlood Trickster Warrior

Miss Chief’s gender- and canon-bending art-historical interventions have been widely associated with the figure of the postindian warrior created by Gerald Vizenor, who likewise takes aim at the trope of the ‘authentic Indian’ in unorthodox ways and highlights the immense burden that has been placed on Native American Indians by its relentless repetition in cultural productions across literature, art and film.Footnote21 Vizenor grounds his understanding of the postindian in the recognition that the term ‘Indian’ is devoid of a ‘referent in tribal languages’.Footnote22 As he points out, the figure constitutes an ‘occidental invention’ that has tragically flattened the cultural terrain, as ‘More than a million people, with hundreds of distinct tribal cultures, were simulated as Indians.’Footnote23 He counters the colonial invention of the ‘Indian’ with the postindian warrior, envisioned as a storier who refashions the supposed ‘real’ of colonial simulations of the ‘Indian’ through the creation of new stories that are narratives of ‘survivance’, a neologism he fashioned as a composite of ‘survival’ and ‘resistance’.Footnote24 Such stories, as he relates, counter the colonial regime in poignant and particular ways that ‘undermine the simulations of the unreal in the literature of dominance’ with ‘wild incursions’ that ‘create a new tribal presence in stories’.Footnote25 They reference Native American Indian contemporaneity, agency and presence and, crucially, constitute ‘an active repudiation of dominance, tragedy and victimry’.Footnote26 The notion of the postindian, as he delineates, also entails an emphasis on the ‘Indian’ crossblood, whom he re-envisages and sets against the trope of ‘a pure tribal Indian identity based on blood and lineage’Footnote27 and that of the ‘tragic halfbreed or mulatto stranded between cultures and forced into an alienated existence’.Footnote28

For Vizenor, the figure of the mixedblood postindian warrior and storier, however, is no mere intellectual exercise; rather, it frames his authorial stance and modus operandi. He describes his own mixed heritage in his autobiographical narrative Interior Landscapes as ‘crossblood heir to Anishinaabe forbears, French fur traders and a third-generation Swedish-American mother’,Footnote29 alternately referring to himself as ‘mixedblood survivor’, ‘mixedblood featherweight’ and ‘mixedblood fosterling’. He presents his mixed blood background as being counter to essentialising tropes of the ‘authentic’ Indian, challenging notions of miscegenation and the validation of ‘Indian’ identity based on blood percentage.

He, moreover, casts the heroes of his narratives as tribal mixedbloods, and, as noted by Vizenor specialist Kimberley M Blaeser, associates the tribal mixedblood with the trickster, making them ‘nearly synonymous’.Footnote30 The trickster thus serves as ‘a metaphor for the tribal mixedblood’ and in turn is closely related to the figure of the ‘postindian trickster’ whose ‘identity reflects all duality and contradiction’.Footnote31 Creating the interconnected figure of the trickster-cum-postindian-cum-mixedblood, Vizenor thus weaves a shifting web of interrelations that defies easy categorisation and challenges colonial binary thinking and its antagonistic either/or.

As this discussion suggests, Miss Chief, much like Vizenor, enacts the figure of the postindian. This is evident when, dressed in high heels, replete with a feather boa and generous lashings of bling, she takes on the persona of the VIP philanthropist and comforts Picasso’s hospitalised desmoiselle. In doing so she undercuts Primitivist tropes of the ‘noble savage’ and wittily satirises Primitivist tropes of European cultural rejuvenation premised on the assumed developmental lag of cultures labelled as ‘primitive’ that disavow the contemporaneity of Indigenised peoples and insist on their posited, inalienable difference. When Miss Chief extends care to the ailing offspring of modern art in the guise of the female philanthropist, she thus wittily plays with the notion of the so-called Primitive and the tropes of rejuvenation it entails. Her approach cleverly forestalls any forms of appropriation and stays clear of associations with victimisation or claims to dominance, characteristics of the colonial regime. She thus enacts a parodic inversion that exceeds the colonial playbook of ‘power over’, refusing the role of the abuser as well as that of victim, epitomising the figure of the postindian storier.

In other words, Miss Chief’s stance does not take as its limit the colonial order of othering, which offers agency and empowerment through the switching of roles. Rather, she makes a point of sidestepping the binary dynamics of modernity/coloniality by declaratively embracing European art, proudly declaring Catlin her lover, calling famous European artists her friends and reminiscing about the delights of her nineteenth-century exotic appeal. By doing so she poignantly subverts constructions of Indian authenticity, claiming her space as an active and coeval cultural navigator in ways that defy representational capture by the colonial order while pointing towards a different future. But how does this stance compare to Santos’s approach to the decolonial, which he frames in terms of the post-abyssal and an ecology of knowledges?

The Post-abyssal and an Ecology of Knowledges

Santos underscores the connection between epistemologies of the Global North, broadly defined, the colonial order and modern science. He points out that modern science, in particular, is considered as ultimate and objective truth beyond culture, and explains that understanding it as ‘the monopoly of the universal distinction between true and false’ leads to the ‘invisibility of forms of knowledge that cannot be fitted into any of these ways of knowing’.Footnote32 As examples he cites ‘popular, lay, plebeian, peasant, or indigenous knowledges’, and points out that these approaches result in epistemicide.Footnote33

He identifies what he calls deeply entrenched abyssal structures of othering as the underlying logic of modernity, calling it the ‘dogmatism of absolute opposition’.Footnote34 Arguing that such oppositional or abyssal thinking must be actively countered as otherwise it ‘will go on reproducing itself’, he asserts that in order to be effective ‘political resistance… needs to be premised upon epistemological resistance’.Footnote35 In other words, a new post-abyssal thinking and what he proposes as an ecology of knowledges are needed so as to avoid the perpetuation of such polarisations and grammars of difference – that is, a paradigm which does not prioritise one form of knowledge over another and which replaces the abyssal either/or with a post-abyssal both/and.Footnote36

As he envisions it, a post-abyssal co-presence of knowledge systemsFootnote37 situates the knowledges and experiences that so far have been jettisoned by the abyssal order alongside the epistemologies of the Global North which remain in place in order to avoid a mere structural reversal and thus to supersede the exclusionary, divisive model of coloniality.Footnote38 To facilitate this shift, he suggests making knowledges that have been marginalised and inferiorised, and are hence unfamiliar within the dominant epistemic order of the Global North, intelligible and relatable through intercultural translation.Footnote39

Santos, however, is not blind to the potential pitfalls of translation and its colonial legacies. He acknowledges that an important question to ask is, ‘How to make sure that intercultural translation does not become the newest version of abyssal thinking, a soft version of imperialism and colonialism.’Footnote40 The stated aim of the project is to ‘eliminate the abyssal line that continues to separate’Footnote41 and thereby enable a shift in perspective that departs from an understanding ‘which reduce[s] realism to what exists’ and involves a ‘refusal to deduce the potential from the actual’.Footnote42 As he explains, what is needed is a stance that exceeds the ‘positivistic and functionalist mechanisms of modern science’ by not only operating ‘on the level of the logos, but also on the level of mythos’.Footnote43 As Santos suggests, what is at stake is dissolving ‘the absolute distinction between rationality and irrationality’ instituted by the abyssal regime, which upholds that ‘Only the mind knows; only reason is transparent regarding what is known; hence only reason is trustworthy.’Footnote44

The project of decolonising that he outlines consequently emphasises connecting arguments and concepts with ‘the fire of emotions and affects, a fire that turns reasons to act into imperatives to act’.Footnote45 This understanding is influenced by the culture of Indigenised peoples of the Andean region of Latin America, and is widely embraced and referred to as corozonar or sentipensar in the literature on decolonisation.Footnote46 Santos characterises this convergence as the ‘warming up [of] reason’,Footnote47 and considers it crucial for actualising the post-abyssal. Recognising that ‘meaning does not necessarily involve conceptual language’, he, moreover, acknowledges the Indigenised epistemological mode of narrative and storytelling as ‘powerful tools to make social experiences separated by time, space and culture mutually accessible, intelligible, and relevant’.Footnote48

His ecology of knowledges thus posits the radical co-presence of diverse knowledges or ways of meaning-making beyond the normative, objectifying and logic-oriented ways enshrined in the colonial register and underscores a ‘pluralistic, propositional thinking’ composed of autonomous strands.Footnote49 It is premised on ‘the recognition of knowledges and the reconstruction of humanity’ of the colonised and the restoration of their ‘inalienable right to have their own history and make decisions on the basis of their own reality and experience’, which he references as an ‘ontological restoration’.Footnote50

Importantly, he also acknowledges that this project, for the most part, is yet to be actualised and that the proposed ‘epistemological diversity does not yet have a form’.Footnote51 As he stresses, this recognition should be understood in the plural, or, more precisely, in a pluriversal sense, as no universal, or generally applicable, approach is to be envisioned. He suggests that the post-abyssal will naturally manifest itself in various forms over time, and calls for a new epistemological imagination consisting of ‘new ideas, surprising perspectives, and scales, and relations between concepts or realities conventionally not relatable’, which will open up ‘new horizons of possibility’ in non-extractivist ways and entail ‘multiple forms of being contemporaneous’.Footnote52

Santos, moreover, proposes the movement of the swerve as the designated and indicative motion of an ecology of knowledges. As he points out, this differs from commonly conceived revolutionary approaches since post-abyssal acts of rebellion involve processes of unlearning and therefore do not conform to the disruptive nature of revolutions. Instead, they represent a gradual accumulation of shifts that exceed the conventional logic of cause and effect. An ecology of knowledges, therefore, is ‘not based on a dramatic break but on a slight swerve or deviation’, which he references as ‘action−with−clinamen’.Footnote53 The concept, as he explains, draws inspiration from the ancient philosophers Epicurus and Lucretius and revolves around the creative force of spontaneous movement, which, crucially, defies explanation, eschews teleology and causality, redeeming the past ‘by the way it swerves from it’ by means of unpredictable deviations.Footnote54 As he elaborates, the movement of the swerve can neither be instigated nor controlled but emerges spontaneously under the right circumstances. He proposes that an ecology of knowledges can help identify ‘the conditions that maximize the probability of such an occurrence’ and that it defines ‘the horizon of possibilities within which the swerve will “operate”’.Footnote55 The question thus arises, how can an ecology of knowledges and its indicative motion of the swerve be situated in relation to the postindian and the movement of transmotion it entails?

Postindian Storying, Transmotion and Word Cinemas

As Vizenor elaborates, transmotion is closely tied to the activity of storying. It involves a ‘spiritual motion’ or ‘active spiritual presence that is not determined by a direct object’Footnote56 and encompasses the transformational communal connections such narrations engender.Footnote57 Postindian storying thus acts in the world. It aims to generate, as Vizenor lays out, ‘Native stories of survivance’Footnote58 that carry the spirit of storying into the contemporary. Moreover, it constitutes a form of resistance that outwits dominance and victimry and counters the ‘manifest manners’ of settler representations by carving out a space of liberation and futurity through imaginative interventions that create a ‘new tribal presence in stories’Footnote59 through ‘the tease of tradition’.Footnote60

For Vizenor, postindian storying, moreover, constitutes a creative response to anthropological extractivism and its conversion of oral traditions into written texts. He contends that this process played a central role in the misrepresentation of Indigenised cultures and the construction of the ‘Indian’ as an object of study. Unsurprisingly, Vizenor has no time for anthropology and its textualised cultural loot.

Vizenor’s issue with colonial plunder is therefore not focused on objects that linger in museums across the Global North. Rather, he takes issue with the cultural raiding of stories, or, to be more precise, their capture by text; an incarceration that kills their spirit, or transmotion, which he, in a tongue-in-cheek wordplay that subverts the claimed objectivity and rationality of the cultural project of colonialism, also references as ‘natural reason of sovereignty’.Footnote61 In fact, he weaves a web of interlaced allusions to make his point, referring to the ‘sovereignty of native transmotion’, declaring sovereignty the ‘motion and transmotion… heard and seen in oral presentations’, also stating that ‘Native transmotion is an instance of natural reason’ while noting that ‘traces of transmotion endure in contemporary native literature’ and that ‘Sovereignty is in the visions of transformation: the humor of motion as survivance over dominance.’Footnote62

However, he does not take issue with textuality per se. His ire, rather, is reserved for the way in which oral stories are pinned down on the page. And he has made it his mission to cultivate an approach in his own authorial practice that aligns with the spirit of oral storytelling, embodying transmotion.Footnote63 His writerly experiments hence seek to emulate the immediacy and situational variance of oral performativity, which he creatively re-envisions in texts that range from journalism, poetry and fiction to scholarly texts. They confront the reader, as Blaeser points out, with ‘riddles in the form of neologisms’ and ‘his special brand of formulaic diction, repetitive phrases, and epithets’ commonly ‘used in oral cultures to aid in memory and for amplification’.Footnote64 A further element of note is the ‘withholding of narrative and descriptive details’.Footnote65 This non-directive approach, as highlighted by Blaeser, serves to prevent the imposition of singular interpretations on a story and compels the listener-reader to engage their imagination. Techniques such as ‘implication, absence, contradiction, and ambiguity’, the use of ‘allegory, metaphor, satire, shock and humor’ along with ‘abrupt transitions, unusual juxtapositions, pronoun shifts, repetitions’,Footnote66 frequent helpings of understatements and an insistence on a lack of closure thus keep the reading ‘audience’ on their toes. Vizenor, in addition, makes use of metaphor, understood as ‘a kind of ambiguity’ where ‘words have either a new or an original meaning, pointing out that the force of the metaphor depends on our uncertainty as we waver between two meanings’.Footnote67

Vizenor’s concern with circumventing knowledge-as-representation hence translates into an array of narrative twists and stylistic devices that engender a textual mode of performative storying which, as Blaeser has pointed out, seeks to simultaneously explain and enact, thus placing ‘context and text’ on the same plane, connecting what is known with the knower in a way that is key to oral narration.Footnote68 As Vizenor observes, this link is severed ‘Once in print,’ where knowledge is abstracted on the page, putting the ‘emphasis on content’.Footnote69

This change in mode associated with the shift from oral narration to text, moreover, as this discussion seeks to draw out, is pivotal for a decolonising move towards the post-abyssal. However, for the most part it is not foregrounded in such discussion. In other words, prevalent approaches to translation neglect the relationship between content and form and do not account for the mode of existence of a ‘knowledge’. Similarly, there is a lack of acknowledgment of the quality of the imaginative response of an audience or listener, a vital aspect of oral storytelling that is integral to its ‘content’. This dimension cannot be adequately conveyed in a discourse solely grounded in logic, which, from this viewpoint, only achieves a partial transfer of the knowledge embedded within such stories.Footnote70 Traditional knowledges, as the literary scholar Elaine Jahner has pointed out, transmit meaning ‘through performative and metaphoric modes of discourse’ and achieve cognitive growth ‘without translation to purely analytical and logical levels of discourse’ by engaging with ‘the cognitive, the affective and the commemorative’.Footnote71 They operate in terms of unexpected, humorous twists and turns, and function as communal points of transformative convergence where, as Vizenor has posited, ‘The listeners and readers become the trickster.’Footnote72

Vizenor’s propositions, moreover, are also deeply engaged with the visual, a further point of alignment with Monkman’s work. He is, for one, highly critical of what he calls the museumification of Indigenised peoples and their capture in images, and states that ‘Tribal cultures have been transformed in photographic images from mythic time into museum commodities,’Footnote73 thus thematising the very issues Monkman addresses in his work. He, for example, explicitly references Curtis, and asserts that the photographer’s images transformed the depicted subjects into ‘metasavages’, rendering them ‘consumable objects of the past’.Footnote74 In his book Crossbloods (1976) he explores this history through the literary character Tune Browne, who observes that he and his community did not expect the images Curtis took of them to have a lasting impact on their lives. In fact, Browne relates that when ‘Curtis stood alone behind his camera, we pitied him there, he seemed lost, separated from his shadow, a desperate man who paid tribal people to become images in his captured families.’ But, as Browne acknowledges, having their pictures taken turned out to be deeply impactful. As he explains, ‘We never saw the photographs then and never thought that it would make a difference in the world of dreams, that we would become his images.’ Yet, ‘we were caught dead in camera time, extinct in photographs, and now in search for our past and common memories we walk right back into these photographs, we become the invented images’.Footnote75

In this context it is crucial to note how Vizenor stages his character, who narrates these events and histories. As Vizenor conveys, when Browne reflects on these happenings in front of an audience, he ‘listened to the birds over the trees’ and removed his wristwatch. As he did so, ‘the dichotomies of the past and present dissolved’, and he ‘turned towards the trees in mythic time’ pausing ‘in silence to celebrate the trees in his visions’.Footnote76

Vizenor, moreover, brings traces and the metaphor of tracking into this fold, and for him this is double-coded. On the one hand, it alludes to a specific form of attentiveness required when following an animal’s path; on the other hand, it refers to the world of dreams and inner visions, that is, happenings which need to be caught ‘near the limits of understanding in written words’ in remembered ‘footprints near the treeline’.Footnote77 The play of words of ‘in print’, or the printed word, and ‘footprint’ marks a different kind of presence. Vizenor’s reference to the visual, therefore, must not be interpreted in a literal sense; this would be reading it in the colonial mode. Rather, his understanding of vision encompasses both the act of observation in the external world and the mode of perception associated with memory and inner realms of knowing.

Postindian Translation, or: Motion is the Message

Vizenor also comments on translation, one of the stratagems Santos proposes for achieving a post-abyssal ecology of knowledges. In contrast to Santos, he largely considers it colonial and associates it with representation. He thus states that ‘Representation, and the obscure maneuvres of translation, “produces strategies of containment”.’Footnote78 Moreover, he blames missionaries and anthropologists for the (mis)translation of tribal stories ‘as mere cultural representations’, pointing out that it is only in what he calls the ‘silence of translation’ that ‘Shadows, memories, and imagination endure.’Footnote79

Vizenor, however, in true postindian fashion, avoids a clear-cut stance of either/or. While deeply critical of translation, he does not dismiss it altogether. What matters is transforming the act of translation in ways that create openings, that allow for the shaping of words ‘in the oral tradition’,Footnote80 that is, using the power of words, even on the written page, in ways that ‘it is set in motion towards vision and knowledge’.Footnote81 The challenge he highlights is to find strategies that allow for writing in the language and literary and aesthetic forms of the dominant culture in ways that counter its inherent propensity for fixity and its penchant for closure by means of representation. This challenge is closely linked to the colonial baggage language carries, raised at the beginning of this discussion concerning the writing of this text, and, by implication, academic writing per se.Footnote82

As Vizenor has put it, when asked about the issue of translating oral traditions: ‘Well I don’t think it is possible, but I think people ought to interest themselves in trying to translate it’ – he adds: ‘I think it can be reimagined and reexpressed and that’s my interest.’Footnote83 This statement is also relevant to the art of Monkman, who, likewise, navigates the visual and aesthetic forms of the dominant culture to critique and unhinge the visual capture of Indigenised people ‘by representation’, which, essentially, is a decolonial move. The suggestion is that the notion of transmotion is key to identifying how Monkman employs this language and the mode of translation it constitutes, thus acknowledging that there is more than a notion of ‘message’ to Miss Chief’s art of parodic rampage. In other words, her critique and reimagining of colonialism’s representational regimes cannot be separated from the manner in which it is conveyed.

Fundamentally, therefore, as this discussion proposes, Miss Chief’s performative art of art-historical rampage and Vizenor’s wily wordsmithing draw attention to an important yet marginalised aspect in debates around the decolonial, highlighting languaging and modes of communication as an integral element of the cultural re-envisioning entailed in a shift towards the post-abyssal. Monkman’s postindian artistic articulations in the Vizenorian mode, in consequence, can be seen to expand Marshal McLuhan’s well-known adage ‘the medium is the message’, offering a postindian-decolonial reimagination encapsulated in the phrase the ‘motion is the message’.

Transmotion thus draws attention to the presential and the situational, which references a different mode of being Vizenor calls an ‘active presence’ and ‘native sovereignty’.Footnote84 Such an emphasis aligns closely with the project of decolonising delineated by Santos, who likewise references different modes of being. He acknowledges what he calls ‘meaning cultures’ and ‘presence cultures’, associating the latter with corozonar.Footnote85 He also recognises that ‘meaning does not necessarily involve conceptual language’Footnote86 and suggests that ‘the work of translation depends as well on nonlinguistic and paralinguistic forms of communication, body language, gestures, laughter, facial expressions, silences, the organization and architecture of space, the management of time and rhythm’.Footnote87 He calls for the decolonisation of the social sciences, advocating for the ‘search for nonextractive methodologies grounded on subject–subject relations rather than on subject–object relations’Footnote88 without, however, elaborating on what this may entail; nor does he contend that this might have implications for the modus operandi of his work. Santos thus skirts the role of language and the implications of the modes of expression he employs in his proposals. This is surprising since on the other hand he acknowledges the fact that many of the ‘ways of knowing’ that an ecology of knowledges gathers under its umbrella ‘may not even be pronounceable in colonial languages’.Footnote89 He also highlights the incongruence and difficulty of ‘Writing a theoretical book about the impossibility of separating theory and practice and writing it in a colonial language.’Footnote90 He therefore is aware of the dilemma of employing a mode of expression that carries a handicapping burden for the task at hand but considers this condition an enabling contradiction to be worked through.Footnote91 This perspective implies the resolution of such incongruities as an aspirational goal. By extension, it suggests that the ‘mutual intelligibility’ he states as the aim of his approach to intercultural translation can be realised within the realm of ‘meaning cultures’,Footnote92 or certainly by an approach leaning towards it, which reinscribes a stance fundamental to the abyssal order he seeks to address.

The notion of transmotion, in contrast, shifts the focus away from the content of a message, bringing the manner of its delivery into view. It highlights a fundamental issue for the project of decolonising that for the most part is not addressed: the challenge of using the dominant language and its associated web of cultural concepts, metaphors and tropes to surpass its limitations. In other words, if the acknowledgment of ‘other modes of knowing and being’ relies on approaches that prioritise cultural or conceptual content as the foundation for understanding then this is bound to generate misinterpretation, which at the very least needs to be acknowledged as an issue.

The postindian approach to translation delineated by Vizenor and performed in Monkman’s work, in contrast, considers attention to languaging as key to an approach of ‘both/and’. It therefore not only offers an enriching corrective to Santos’s understanding of translation, which he understands to be a complex but self-evidently ‘argumentative work’,Footnote93 but also to a much wider field, including the academy that hosts many of the key debates on the subject. In consequence, the notion of transmotion can be understood as a potent and generative decolonising stance that is more comprehensive and impactful than the movement of the swerve referenced by Santos. The postindian parodic and purposive connecting of content and form, medium and message, knower and known, therefore, metaphorically speaking, can be said to put flesh on the bones of the post-abyssal as delineated by Santos in the cognitive mode.

The Evil Gambler and the Contradictions of Life

There is a further aspect linked to transmotion, and the fluid, non-categorising approach to cultural storytelling it references, which is often overlooked but is relevant to this discussion: the figure of the evil gambler, the disavowed ‘other’ of the ‘sexy’ figure of the trickster that is integral to the notion of the postindian. Vizenor says that this figure points to the contradictions of life and the human capacity for good and evil. As he states, the evil gambler ‘lurks in all of us’, adding that ‘part of the contradictions I am speaking of is that we are capable of good and evil’.Footnote94 He points to a fundamental divergence between the world views and epistemologies of Native American Indians and those of the Global North evident in their response to contradiction, elaborating that

The Western world would purge evil… as if evil entered the creation of gods and my body, and I must purge it… to reach a state of grace. In a tribal worldview, it seems to me, we always have the potential for good and evil. We are good and evil; it’s not outside, it’s in us… Footnote95

Vizenor’s understanding of contradiction, therefore, is different from the one proposed by Santos, who states that ‘The fertility of contradictions does not lie in imagining ways of escaping it but rather in ways of working with and through it,’ calling it an ‘enabling contradiction’.Footnote98 Santos thereby foregrounds its resolution and hence, by implication, its ‘end’. Vizenor, in contrast, points out that contradiction ‘is not something you have to overcome’.Footnote99 Rather, he suggests embracing transformational, imaginative play and adopting a stance that does not aim to resolve contradictions but which acknowledges them as integral to life and as requiring recognition and balance rather than ‘fixing’.Footnote100 As he explains, ‘The “evil gambler”… does not stand for something. That would be representational, but it is something, it is a mystery, it is the contradiction of life;’Footnote101 a statement which further highlights the fundamental difference between a postindian approach to decolonising embodied in Monkman’s work and the perspectives proposed by Santos.

Masters of Word Castles and the Figure of the Earthdiver: Concluding Thoughts

I

As has been developed, affinities are apparent between Monkman’s work as explored through the lens of the Vizenorian figure of the postindian and Santos’s ecology of knowledges, while notable differences arise when contrasting approaches to translation and juxtaposing transmotion and the swerve. These disparities revolve around negotiating the dilemmas entailed in seeking to unhinge from colonialism while communicating by means of concepts, words and grammatical structures marked by it, highlighting a fundamental difference in modus operandi and world view.

Santos’s ecology of knowledges, which envisages a non-hierarchical paralleling of different cultures of knowing – many of which, as he acknowledges, do not foreground the conceptual – is based, as presented, on the premise that differences in knowledge cultures can be reconciled through intercultural translation in an effort that leans towards resolution. Even though he is aware of the inherent issues of using colonial language, he approaches this challenge as a contradiction to be worked through, implying that a form of ‘overcoming’ may be achieved which foregrounds the conceptual.

As discussed, a postindian approach to translation, in contrast, understands contradiction to reflect a fundamental condition of life that needs to be negotiated through the transformative, creative and playful interventions of postindian storying, which restore equilibrium rather than seek resolution. Such storying, moreover, entails a shift in approach encapsulated by the notion of transmotion, which dehierarchises prevalent ways of knowing, reconnecting content and form, medium and message, knower and known. In consequence, the notion of transmotion can be seen to offer a potent and generative approach to decolonising and to be of more encompassing scope than the movement of the swerve suggested by Santos.

The postindian approach to decolonising performed in the work of Monkman, the linked notion of transmotion and the stance of both/and on which it is premised and which it seeks to language, furthermore, implies a shift with regard to identity construction and the notion of the self epitomised in the figure of the evil gambler; a move that fundamentally transforms the colonial paradigm and the alterity upon which it is based. It thus offers a significant and multifaceted contribution to discussions about decolonisation which extends well beyond the immediate focus of this discussion, broaching broader questions about the nature of the decolonial project and the manner of engaging with it. It proposes a shift in the way of being in the world and underscores that embracing the stance of the decolonial ‘both/and’ is more than an intellectual exercise: it necessarily disrupts ‘business as usual’ on the academic front and requires a fundamental shift in stance as knowledge is no longer understood to be solely ‘out there’ as it is no longer considered to be detached from the ‘knower’.

This realisation refers the discussion back to a point made at the outset concerning academic language, its embedded coloniality and the potential, and indeed likely, perpetuation of colonial fault lines through its utilisation. It brings the understanding full circle, folding it back on the enquirer or ‘knower’, calling for a further element to this conclusion beyond its stated objective of exploring the work of Monkman in view of the contributions it offers to debates around the decolonial as revealed by the lens of the postindian and made evident in view of Santos’s ecology of knowledges. In this light, a reflection on the implications of these insights for the practice of art-historical enquiry is recognised as being an integral element of the discussion. The ramifications of the discussion of Monkman’s work explored in relation to transmotion, translation, the postindian and the swerve for the researcher/querier and the broader academic landscape will therefore be considered in the following.

II

Vizenor has evocatively described the colonial mode of writing in terms of ‘translators and talebearers’ who ‘march march march their words down mission rows in perfect grammatical time, building word castles’ and ‘fabricating their words in prestressed phrases, interior mechanical landscapes’.Footnote102 The stories they construct, as he elaborates, enlist the reader to become ‘master of sand castles’,Footnote103 thus perpetuating the cycle. He contrasts this scenario with the tracking of remembered footprints, which, while not observed directly, arise ‘near the tree line, near the limits of understanding in written words’, and refers to such a process as ‘a visual event’ emerging between a narrative’s ‘creators, tellers and listeners’; an understanding that emphasises the communal aspect of storying, where the storyteller acts as mediator between a narrative that wants to emerge and an audience summoning it forth.Footnote104

When applied to an art-historical context, such a change in perspective reframes how the discipline and academia at large interpret and approach the construction of knowledge. It, for example, prompts a switch in outlook that shifts the focus away from the singular knowledge generator, foregrounding the communal aspects of ‘thinking with’ readily evident in the footnotes and bibliographies that inhabit the margins of academic work, both literally and figuratively, facilitating a reframing of how knowledge production in the academy is understood. It offers a further facet, for example, to the collaboration of philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst and philosopher Félix Guattari and their co-authoring of A Thousand Plateaus, often referenced in terms of ‘Deleuze-Guattari’. Deleuze describes their association as being akin to ‘something passing through you, a current’Footnote105 and considers writing in general in terms of a ‘writing with’, since ‘Even when you think you’re writing on your own, you’re always doing it with someone else you can’t always name.’Footnote106 Deleuze-Guattarian philosophy, moreover, similar to Vizenor, seeks to evade the mode of either/or, stating that ‘The only way to get outside the dualisms is to be-between, to pass between, the intermezzo.’Footnote107

What is at stake, therefore, is a reorientation, a re-envisaging of a manner of doing, an attitudinal step change which requires individual and collective efforts of way-finding rather than a prescriptive approach or a definitive method. Entailed in such a project is the impetus to connect with aligned traditions of writing within the academy and beyond, thus linking up with Santos’s call to reconnect with marginalised and forgotten traditions within the Global North that counter the colonial spirit.Footnote108 I, moreover, would like to suggest the addition of a further element to facilitate this endeavour: the figure of the mixedblood urban earthdiver, a concept Vizenor has developed by drawing inspiration from the creation myths of Indigenised peoples, which I propose as a touchstone for this process.

The earthdiver shares similarities with the postindian warrior while placing a specific emphasis on the act of ‘creating or recreating’ the world.Footnote109 It hence can, by implication, serve as a metaphor for creative fashionings of all kinds, including academic writing, while referencing a decolonial approach characterised by the principle of both/and. In fact, Vizenor calls urban earthdivers the ‘new metaphors between communal tribal cultures and the cultures that oppose traditional connections’.Footnote110 When he states that ‘white settlers are summoned to dive with mixedblood survivors’ and are told to ‘dive deep’ in order to ‘dream back the earth’,Footnote111 this can thus be understood to refer both to the political context of settler colonialism and, on a metaphorical level, to a joining of worlds separated by abyssal divides more broadly.

Moreover, Vizenor offers further insights on the earthdiver that are pertinent to this proposition. He writes: ‘Now the river flows through the cities but not through the people… the white man is separated, cured from his smallpox disease, but cursed with machines… surrounded with bouquets of plastic flowers.’Footnote112 But, as the ‘river shivers, the plastic cracks in the cold’, emitting an audible ‘crack, crack, crack’, offering an ‘urban connection’ to dive back into the earth.Footnote113 This evocative passage for me conjures up the image of the urban flâneur, the quintessential figure of the modern invoked by Baudelaire in his essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ (1863), who is ‘botanising the asphalt’ for impressions of city life which he observes from a detached, disengaged, external viewpoint.

The flâneur, in other words, embodies the objectifying stance that characterises modernity/coloniality that both Monkman and Vizenor critique and refashion in their work. In contrast, the mixedblood, urban earthdiver epitomises the principles of a postindian, post-abyssal and decolonial era, and I propose extending the understanding of this figure to encompass the role of an emblematic figure for this era: s/he is a mixed, urban wanderer between the worlds who carries the potentialities of many ‘sides’ and dives into the cracks in the asphalt, that is, ‘into the racial darkness in the cities, to create a new consciousness of coexistence’;Footnote114 s/he extends an invitation for all to take a deep dive below the abyssal structures of representation to connect with the underworld of the colonial repressed; s/he calls on us to orientate towards a mode of storying and cultural narration ‘written in double vision, peeled from visual experiences on the trail near the spacious treeline’;Footnote115 s/he navigates contradictions, acknowledges the evil gambler in all, embraces the either/or.

In other words, the figure of the mixedblood, urban earthdiver envisions the spirit of the decolonial age and is well suited to serve as its figurehead, a suggestion that prompts the question, what kind of art history will emerge when writing in this image?

Notes

1 Gerald Robert Vizenor, Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska and London, 1998, pp 14−16

2 Gerald Robert Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska and London, 1999, pp 129−130

3 Kimberley M Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor: Writing in the Oral Tradition, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1996, p 52

4 Gerald Robert Vizenor, ‘Introduction’, in Gerald Robert Vizenor and James E Seaver, eds, Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures, American Indian Literature and Critical Studies 8, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1993, pp 3–16, pp 5–6

5 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 54

6 Vizenor, Manifest Manners, op cit, p 11

7 Gerald Vizenor and A Robert Lee, Postindian Conversations, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska and London, 2003, p 84

8 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 15

9 See eg David McIntosh, ‘Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Postinidian Diva Warrior, in the Shadowy Hall of Mirrors’, in David Liss and Shirley J Madill, eds, The Triumph of Mischief: Kent Monkman, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2008, pp 31–46, p 37; and Renate Dohmen, ‘The Artist as Postindian Warrior: Saviourism, Appropriation and Care in the Art of Kent Monkman’, Journal of Global Studies and Contemporary Art, vol 7, no 1, ‘Indigenous Epistemologies and Artistic Imagination’, 2020, pp 409–442

10 Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, California, 2021, pp 106–110 (Vanessa Machado de Oliveira is predominantly known as Vanessa Andreotti).

11 Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2018, p 6

12 Aníbal Quijano, ‘Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America’, International Sociology, vol 15, no 2, 2000, pp 215–232, at p 222

13 Arturo Escobar, ‘Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise: The Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program’, Cultural Studies, vol 21, no 2–3, 2007, pp 179–210, at p 200

14 Ibid, p 185. See also Catherine E Walsh and Walter Mignolo, ‘Introduction’, in Walter Mignolo and Catherine E Walsh, eds, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2018, pp 1–12, at p 4

15 Monkman refers to the prevalence among Native American Indians of Two Spirit people, who were revered for embodying both male and female spirits and often assumed roles associated with the gender opposite to the one assigned at birth.

16 Melissa M Elston, ‘Subverting Visual Discourses of Gender and Geography: Kent Monkman’s Revised Iconography of the American West’, Journal of American Culture, vol 35, no 2, 2012, pp 181–190, at p 183

17 McIntosh, ‘Miss Chief Eagle Testickle’, op cit, p 37

18 The show was created for the BMO Project Room, Toronto, and on display January to November 2015.

19 Kent Monkman, Casualties of Modernity, 2015, 2:14–2:32

20 Ibid, 2:38–3:08

21 Vizenor’s notion of the postindian has gained wide currency, especially in discussions of the literary work of Indigenised authors but also in the visual arts, with notable variance in its interpretation. See Jessica L Horton and Cherise Smith, ‘The Particulars of Postidentity’, American Art, vol 28, no 1, 2014, pp 2–8

22 Vizenor, Manifest Manners, op cit, p 11

23 Vizenor cited in A Robert Lee, ‘Introduction’, in Gerald Robert Vizenor, Shadow Distance: A Gerald Vizenor Reader, Wesleyan University Press, Hanover, New Hampshire, 1994, pp ix–xxix, pp xii–xiii

24 See Deborah L Masden, ‘On Subjectivity and Survivance: Rereading Trauma through The Heirs of Columbus and The Crown of Columbus’, in Gerald Robert Vizenor, ed, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2008, pp 61–87, at p 67

25 Vizenor, Manifest Manners, op cit, p 12

26 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 15

27 David Murray, ‘Crossblood Strategies in the Writing of Gerald Vizenor’, in A Robert Lee, ed, Loosening the Seams: Interpretations of Gerald Vizenor, Bowling Green State University Popular Press, Bowling Green, Ohio, 2000, pp 20–37, at p 21

28 Ibid, p 33

29 Vizenor and Lee, Postindian Conversations, op cit, p 7

30 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 155

31 Ibid

32 Boaventura de Sousa Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges’, Eurozine, 29 June 2007, pp 1–33, at p 2 and p 16 respectively

33 Ibid

34 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 118

35 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 9 and pp 9–10 respectively

36 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 78

37 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 8

38 Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South: Justice against Epistemicide, Routledge, Abingdon and New York, 2014, p 42

39 Ibid, pp 212–235

40 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 18

41 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 109

42 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 17

43 Ibid

44 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 98 and p 15 respectively

45 Ibid, p 98

46 Ibid, p 100. See also Arturo Escobar, Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible, Duke University Press, Durham, 2020, especially p 161 n 1 but also p xxxv and pp 67–83

47 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 99

48 Ibid, p 102

49 Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, p 12 and p 11 respectively

50 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 109

51 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 10

52 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 110, p 127, p 137 and p 125 respectively

53 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 17, italics in the original

54 Ibid. See also Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, p 97

55 Santos, ‘Beyond Abyssal Thinking’, op cit, p 17

56 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 16

57 Helmbrecht Breinig and Karl Lösch, ‘Gerald Vizenor’, in Helmbrecht Breinig and Wolfgang Binder, eds, American Contradictions: Interviews with Nine American Writers, Wesleyan University Press, Hanover, New Hampshire, 1995, pp 143–165, at p 150

58 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 15

59 Vizenor, Manifest Manners, op cit, p 12

60 Vizenor and Lee, Postindian Conversations, op cit, p 93

61 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 185

62 Ibid, p 182, p 184 and p 185 respectively

63 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 29

64 Ibid, p 31

65 Ibid, p 32

66 Ibid, p 33

67 Vizenor citing Donald Davidson in Gerald Robert Vizenor, Earthdivers: Tribal Narratives on Mixed Descent, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1981, p xvii

68 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 143 and p 80 respectively

69 Gerald Vizenor, ‘Trickster Discourse: Comic Holotropes and Language Games’, in Vizenor and Seaver, eds, Narrative Chance, op cit, pp 187–211, at p 208

70 See Elaine Jahner, ‘Metalanguages’, in Vizenor and Seaver, eds, Narrative Chance, op cit, pp 155–185, at pp 165–167

71 Ibid, p 167

72 Vizenor, ‘Trickster Discourse’, op cit, p 189

73 Murray, ‘Crossblood Strategies’, op cit, p 85

74 Ibid

75 Gerald Vizenor, Crossbloods: Bone Courts, Bingo, and other Reports [1976], University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1990, p 90

76 Ibid, p 93

77 Vizenor, Earthdivers, op cit, p 166

78 Vizenor, Manifest Manners, op cit, p 70

79 Ibid, p 75 and p 74 respectively

80 Gerald Robert Vizenor, Wordarrows: Indians and Whites in the New Fur Trade, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1978, p vii

81 Ortiz quoted in Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 82

82 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 75

83 Vizenor quoted in Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 16

84 Vizenor, Fugitive Poses, op cit, p 15 and p 179 respectively

85 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p 103

86 Ibid

87 Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, p 216

88 Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire, op cit, p x

89 Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, p 238

90 Ibid

91 Ibid

92 Ibid, p 217

93 Ibid, p 232

94 Breinig and Lösch, ‘Gerald Vizenor’, op cit, p 149

95 Ibid, p 148

96 Ibid p 149

97 Ibid, p 163

98 Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, p 238

99 Breinig and Lösch, ‘Gerald Vizenor’, op cit, p 149

100 Ibid, pp 150−151

101 Ibid, p 148, emphasis in original

102 Vizenor, Earthdivers, op cit, p 166

103 Ibid

104 Ibid

105 Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations (Pourparlers), Martin Joughin, trans, Columbia University Press, New York, 1995, p 141

106 Ibid

107 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Brian Massumi, trans, Athlone Press, London, 1999, p 277

108 Santos, Epistemologies of the Global South, op cit, pp 99−115

109 Blaeser, Gerald Vizenor, op cit, p 105

110 Vizenor, Earthdivers, op cit, p xix

111 Ibid, pp x–xi and p xvi respectively

112 Ibid, p 91

113 Ibid

114 Ibid, p ix

115 Ibid, p 166