Abstract

This article reflects on notions of the embodied archive in diaspora art, with a particular focus on my situated knowledge and positionality as a diasporic artist of mixed Turkish and Austrian heritage who lives in the United Kingdom. Taking my multilingual video performance Surya Namaz (2018) as a case study, I address the question of roots, ancestry or lineage that arose in the making of the video through writing with the practice, and critically explore the pitfalls of self-othering, the trope of the return and the problematic position of the Spivak’s native informant in the context of diaspora art. Reflecting on the multiplicity of voices and encounters that shaped the making of Surya Namaz, I highlight the potential of Relation to resist an essentialist conception of identity while exploring the body as diasporic archive and site of multiple belongings.

To what extent can practice-based research, by blurring the boundaries between maker, researcher, editor and writer, encompass the multiplicity of voices pointing towards a polyphonic history of art? Might we be able to reimagine hegemonic notions of the archive by expanding our understanding of the body as a ‘living archive’ of diaspora? Departing from these questions, in this article I will attempt writing with or nearby my art practice,Footnote1 exploring the potential of practice-based research and polyphonic writing through an analysis of my video performance Surya Namaz (2018).

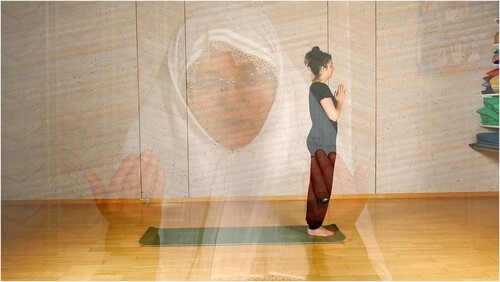

Surya Namaz, which formed part of my practice-based doctorate, explores the moving body (mine and others) in relation to the formation of cultural identities and belonging.Footnote2 The video shows Marisol, my yoga teacher, my aunt Ümit and myself engaging in the distinct physical-spiritual practices of namaz, the Muslim prayer ritual, and Mysore (style) ashtanga yoga. I interact with both practices, learning and enacting ritualistic movement sequences accompanied by the recital of Sanskrit chants and verses from the Qur’an in Arabic as performances in front of the camera. The soundtrack includes partially translated fragments of a semi-autobiographical narrative in multiple languages (German, Turkish and English). Alongside the multilingual soundtrack, filmic strategies such as superimposition are used to articulate the complexity of multiple belongings in the ‘diaspora space’, as a site ‘where multiple subject positions are juxtaposed, contested, proclaimed or disavowed’.Footnote3

Inspired by Trinh T Minh-ha’s interdisciplinary approach to filmmaking and writing, I aim here to emulate her conception of ‘speaking nearby’ my practice as a method of writing ‘that does not objectify… A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it.’Footnote4 This relational way of writing is more than a ‘technique or statement’; it is deeply connected to the question of positionality and the way one relates to the world.Footnote5 Taking Surya Namaz as case study, I aim to reflect on notions of embodied knowledge and ‘listening to the body as an archive’ in diaspora art,Footnote6 in particular focusing on my situated knowledge and positionality as a serial migrant and diasporic artist of mixed Turkish and Austrian heritage who currently resides in the United Kingdom.

Through an exploration and mobilisation of notions of embodied knowledge and my body as a living archive, I intend to challenge and destabilise conventional notions of the archive and its format and function as a practice of imperial recordkeeping. I borrow the term ‘living archive’ from Stuart Hall, who describes the ‘living archive of the diaspora’ as an archive that is ‘present, on-going, continuing, unfinished, open-ended’, as opposed to being linked to notions of tradition or the past.Footnote7

The imperialist practice of archiving is closely connected to questions of power and knowledge and therefore has been an important tool of dominance in the context of colonialism, going hand in hand with the extraction and appropriation of Indigenous knowledge. As Jacques Derrida stated, ‘there is no political power without control of the archive’.Footnote8 According to the anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler, the link between what counts as knowledge and who has power and control over it has long been a founding principle of colonial ethnography. As she writes, ‘what constitutes the archive, what form it takes and what systems of classification signal at specific times, is the very substance of colonial politics’.Footnote9

Over the last two decades there has been a growing tendency within archival practice and theory to critically explore the erasure and marginalisation of non-European cultures and their histories through Western modes of knowledge production and recordkeeping. The archival turn, a term coined by Stoler, points to this renewed attention to the archive as a subject of investigation.Footnote10 Artists’ interventions and efforts to reimagine and critically engage with archives – whether as subject, source or concept, and the intersections between them – have turned a critical spotlight on the colonial and imperialist legacy of archives, responding to gaps and ‘archival silences’. Crucially, decolonial archival practice has questioned the supremacy of the written language and text-based documentation in recordkeeping and archiving, reimagining the archive by opening it to other modes of cultural expression, including orality and movement languages.Footnote11 Conceiving of my moving body in Surya Namaz as an archive and tool for the storage and transmission of knowledge, I will build on these efforts, aiming to shift the prevailing Eurocentric imaginary, which has been shaped by dualistic thought, and counter colonial and imperialist legacies of the archive and archival practices.

Writing with the practice, I aim to contribute to the slow yet steady destabilisation of an imagined or imaginary binary between theory and practice, academic writing and art-making, as a destructive schism that lies at the heart of Western knowledge production. To quote Australian dance artist and academic Siobhan Murphy, ‘this splitting is detrimental to both activities’.Footnote12 On the one hand there is the pitfall of artworks ‘illustrating’ theories, and on the other hand there is the tedious format of academic writing attempting to offer explanations for artworks. Writing with the practice, I intend to explore to what extent academic writing and art practice can be conceived as ‘interrelated activities, resulting in a synthesis of multiple modes of intelligence’.Footnote13 Hoping to avoid the aforementioned pitfalls of theory becoming an ‘explanation’ of my video performance, I will explore the potential of ‘resonance’ as an intuitive tool for writing with the practice.Footnote14 Which discursive fields or philosophical concepts resonate with my practice? What are their implications?

Departing from the question of roots, ancestry or lineage that arose in the making of Surya Namaz, I will consider the pitfalls of self-othering, the trope of the return and the problematic position of Spivak’s native informant in the context of diaspora art and its histories.Footnote15 Searching for ways to challenge the binary of ‘root identity’ in resonance with Glissant’s poetics of Relation, the article will explore the potential of the body, voice(s) and ritual practice as a diasporic archive and site of multiple belongings.Footnote16

Writing with or nearby my video performance allows me to integrate embodied (corporeal) and verbal knowledge into my research through conceiving of my body as a ‘living archive of diaspora’. This distinctly practice-based approach expands on conventional notions of the archive and recordness, helping us, to borrow J J Ghaddar and Michelle Caswell’s words, ‘imagine both a different way of archiving and a different world to be archived’.Footnote17

Surya Namaz

The video opens with a black frame representing the unrepresentable darkness of the night. The voiceover (in the distance) is the call to prayer in Arabic:

Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!

Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!

Ashhadu alla ilaha illa Allah.

Ashhadu alla ilaha illa Allah.

Ashhadu anna Muhammadan Rasulu Allah.

Ashhadu anna Muhammadan Rasulu Allah.

Hayya ‘alas-salah. Hayya ‘alas-salah.

Hayya ‘alal-falah. Hayya ‘alal-falah.

Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!

La ilaha illa Allah.Footnote18

The soundtrack of the video transports me back to the disorientation and confusion I experience in the first days of being ‘back’ in Turkey, a place I left at the age of nine, relocating to Austria. Listening to the sound recording, I relive the sensation of being woken up by the muezzin’s call to prayer, or ezan, in the middle of the night.Footnote19 While listening to the audio recording of the ezan, amplified through noisy speakers mounted at a nearby mosque, I recall the shrill noise of my aunt’s metallic alarm clock filling the night air: a piercing sound that made me wonder if the alarm was perhaps competing with the muezzin’s call to prayer. My aunt would set this alarm as a precaution, in case she slept too deeply and would not wake to the muezzin’s call in time for worship.

The image slowly fades to show me standing at the front of my yoga mat. Next to me is my yoga teacher Marisol, instructing me to move from one position to the next. Our eyes are closed and our hands are placed together in front of our hearts, performing Namaste. Namaste literally translates to ‘I bow to you’.

The composite title Surya Namaz alludes to surya namaskar, a yoga sequence known as the sun salutation in English, in imaginary relation to namaz, the Muslim prayer ritual. Surya literally translates to ‘sun’ in Sanskrit and namaz (known as salah or salat in Arabic) designates the obligatory Muslim prayer ritual in Farsi, Urdu and Turkish. Etymologically, namaz can be traced to the Sanskrit word nama, ‘to salute, to bow’.

I can hear Marisol’s voice beginning to count the breaths in Sanskrit: 1. Ekam (yekum) – Inhale. I raise my arms up straight above my head and look up at my fingertips, hands together. 2. Dve (dway) – Exhale. Releasing the breath slowly, I bring my hands down, placing them on either side of my feet, and straighten my knees, aiming to touch them with my nose. While I inhale slowly, lifting my head, placing my ‘gaze’ or internal focus between my eyebrows, suddenly images of my Turkish grandmother performing namaz quietly begin to waver in my mind’s eye.

Marisol and I are chanting the invocation mantra of ashtanga yoga together. I repeat the phrases after her. We are chanting in Sanskrit, the sacred language of Hindu ritualistic practice. We are chanting in a small yoga studio in Solothurn, Switzerland. We could be anywhere. We are reciting the Sanskrit mantra in the presence of a camera, a sound-recording device, a directional microphone and two daylight lamps.

The video was inspired by flashes of memories of my paternal grandmother performing namaz. These memories surfaced in my mind’s eye during yoga practice with my Nigerian-Puerto-Rican yoga teacher Marisol. I had carried them with me since childhood in Turkey and moving between and across various countries, cultures and languages. They are an embodied archive and longing for intergenerational connection, activated through physical movement and specific poses in asana (physical yoga) practice. Writing with the practice, I consider my body (in movement) not as something I have but as an experience of what I am.Footnote20

The teacher or elder’s embodied knowledge is being passed down to the student in both namaz, the Muslim prayer ritual, and yoga through the transmission of knowledge between bodies, repetition and recital of chants and movement phrases. The codified movement sequences of both practices could be regarded as what Tonia Sunderland has described as ‘gestural documents’. As she argues, ‘like text-based and oral documents, a gestural document – one comprised of codified gestures and/or phrases of gesture – is capable not only of communicating meaning, but also of serving the archival functions of maintaining and preserving content, context, and structure as well as representing the past’.Footnote21 Her proposition of expanding the notion of the archive or archival records beyond text-based documents to include gesture and orality is of particular importance for diasporic communities, whose culturally distinct practices have often been marginalised or erased in hegemonic forms of archival record-keeping foregrounding text-based evidence and written documents.

My aunt, Ümit hala, and I are standing at the back of our prayer rugs, facing the qibla (Mecca) in her living room. We are getting ready to perform sabah namazı, the morning prayer. The ritualised Muslim prayer, which is performed five times a day, combines bodily postures and spoken prayers.Footnote22

I hear myself saying Allāhu akbar (‘God is most great’) while we bring our hands up to shoulder height, our palms facing the qibla (Mecca). We then place our right hand over our left, in front of our heart. I fix my gaze on the patterns of the prayer rug, to where I will soon lower myself to place my forehead in prostration (secde in Turkish).

Marisol performs her own movement, led by her own breath. I perform my own movement, led by my own breath. And yet we are embodying the movements of other bodies before us. We are reciting the Sanskrit mantra to acknowledge and express our gratitude to all the teachers (gurus) who have passed on this practice up to the present. We are chanting to bow to our practice. The practice is our teacher or guru, (which translates to) the dispeller of the darkness of ignorance. What can we learn from the practice?

The Body as the Archive of Diaspora

Being of mixed parentage, I fall into the category of people whom the Palestinian-American anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod referred to as ‘halfies’ in terms of national and cultural identity. According to Abu-Lughod, ‘halfies’ and feminists face specific dilemmas in relation to the distinction between self and other. For both, ‘the self is split, caught at the intersection of systems of difference’, which leads to a heightened awareness of issues such as positionality, audience and power relations. Whether we consider ourselves as artists, art historians or anthropologists, we have to take into account how our work is embedded in the historical present and reflect on ‘the situatedness’ of our knowledge. As Abu-Lughod writes, ‘standing on shifting ground makes it clear that every view is a view from somewhere and every act of speaking a speaking from somewhere’.Footnote23 My position as insider-outsider in relation to the distinct practices of namaz and surya namaskar was central to the creation of Surya Namaz. Performing culturally distinct rituals and spiritual movement practices, I am moving with and through my body between different states of longing, belonging and not belonging, exploring my body as an archive of transcultural encounters.

Soundtrack of voices whispering prayers in Arabic.

We are going to visit babaanne’s grave tomorrow. As a child I would watch her praying.

Sssht cocuklar, sakin olun!

We were not allowed to pass in front of her prayer rug.

I can still hear her soft voice mumbling verses from the Qur’an.

In many instances, moving from one place or culture to another comes with a loss. It can mean the loss of a particular language, ritual and/or certain (bodily) habits. The experience of dispersion or dislocation, characteristic for the diasporic experience, is often marked by a tearing apart of families or familial ties over time and space, moving across and thereby transgressing cultural, geographical and national boundaries. Crucially, moving from one place or culture to another also offers the potential for transformation and multiplication, for example through the encounter with new languages and (bodily) habits – such as yoga (in my case). As Laura Marks states, ‘the body is a source not just of individual but of cultural memory’.Footnote25 This resonates with the conception of the body as an intergenerational and collective (inter)cultural archive, which can be reactivated and accessed by drawing on the ‘memory of the senses’,Footnote26 similar to the memories of my Turkish grandmother’s namaz practice, stored deep in my body, that inspired my creative exploration of the Muslim prayer ritual in Surya Namaz. The social aspect of the intergenerational embodied experience is emphasised by the following quote of Akram Khan, where the artist’s body and mind are compared to a ‘memory bank’ containing not just one’s own but also one’s ancestors’ experiences, instigating the creative process:

I believe the mind and body are like a library that holds not only your own experiences but also those of your ancestors, and so when external forces (like watching a film, or studying a picture, or experiencing a theatre piece) are presented to you, it triggers something within the library of your memory bank and suddenly the file that is triggered opens, and the language of inspiration begins.Footnote27

Travelling to my aunt’s in Turkey or my ‘return’ to Karapınar could be perceived in relation to the phenomenon of ‘going native’, a tendency that has been criticised as ‘self othering’ or ‘ethnic marketing’ in the context of contemporary global art and the problematic framing of artists as representatives of their place of origin.Footnote30 Engaging with my Islamic heritage, and more specifically performing the Muslim prayer ritual in the context of a moving image artwork that I knew would primarily be seen by a majority white and non-Muslim audience, involved a certain risk of enforcing stereotypical representations of Muslim women while assuming the problematic position of the native informant.Footnote31

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak uses the figure of the native informant, a term borrowed from ethnography, to question the authenticity often ascribed to the voices of migrants or (postcolonial) others who by giving information on their cultures of origin come to be seen as providing evidence of an ‘objective truth’ in their position as such.Footnote32 Aware of the contradictions involved in my self-representation as a veiled woman performing namaz in the making of the video, I was conscious of the danger of becoming a native informant, and thereby of auto-Orientalising,Footnote33 essentialising and exoticising my Islamic heritage. Guided by awareness of the risks involved in my self-representation, I set out in the video to explore the potential of artistic and filmic strategies that could challenge fixed notions of belonging and identity. How could one subvert stereotypical representations and avoid the pitfall of essentialising or fetishising one’s cultural heritage?

The voiceover continues I created my own religion when I moved from Turkey to Austria. I was nine. In school there was an old man wearing a long white robe, holding a chalice, a priest. At a religious service, he claimed that Jesus was our bread and wine. I was left speechless. It is then I secretly founded my own religion and baptised my cat. She did not like it. In school the songs we had to sing about Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost always made me cringe. I had the same feeling in my first yoga class when I had to chant the word Aum (amplified by a recording of a group of people chanting Aum simultaneously). The room was full of strangers, mostly skinny, non-Asian, wearing elastic, colourful, tight-fitting clothing and chanting in Sanskrit. But practising with Marisol, my Mysore yoga teacher, or as some would say ‘guru’, was a totally different experience. Her chanting of the invocation mantra and the way she guided me through the postures made me feel liberated and alive. I suddenly felt connected to something much larger than myself.

The next scene shows a close-up of my yoga teacher, Marisol, chanting a-u-m (om). Her face merges with a close-up of my aunt Ümit hala reciting the Qur’an. The superimposed image is echoed in the soundtrack, layering Allah Akbar! and a-u-m. For a moment both faces are merged and become one.

Video-editing proved to be crucial in articulating processes of hybridisation, highlighting the imagined and constructed nature of cultural identity and belonging. Editing and montage facilitate the bringing together of disparate elements, such as the culturally distinct practices of yoga and namaz. The disjunction, and friction between sound and image, can express the contradictions and feelings of dispersion experienced by the diasporic subject. Editing techniques, such as superimposition or the creation of multiple layers of sound and the voiceover narration, can become powerful tools to destabilise or comment on the meaning of the image.

Voiceover Ümit hala suggests that I cover my hair for prayer. I choose a scarf of light blue colour. It suits you, she says. It feels strange to cover my hair. The Bible says every woman who prays should cover her hair. Every woman who has her head uncovered while praying disgraces her head. I am not sure what the Qur’an says about women’s dress code.

As an uncommented image, my self-representation as a veiled woman performing namaz could be read as an example of self-othering, potentially reinforcing stereotypical images of Islam and presumptions about Muslim women’s dress code. In this instance, the voiceover narrative proved to be an important tool to destabilise and counter documentary-style images that could otherwise be misread as objective representations, promoting a presumably authentic and oversimplified ‘Muslim look’. The multiple layers of the soundtrack (with partial translations of English into German and Turkish) allude to the fact that, unlike the Bible, the Qur’an does not contain a clear statement that would prescribe women to cover their hair.

Roots and Relation

Critically exploring the potential for hybridity to challenge essentialist notions of identity through filmic and sonic strategies, Surya Namaz proposes a rhizomatic conception of identity, relating yoga and namaz to Catholic Church rituals that I experienced at school in Austria, simultaneously hybridising and connecting these ritualistic practices in rhizomatic ways. This coming together of disparate elements resonates with Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant’s theory and poetics of Relation, which conceives of identity ‘no longer as a unitary root but as a root reaching out to meet other roots’, thereby countering assumptions of an essentialised and pure ‘root identity’.Footnote34

Glissant’s complex theory of Relation and profound critique of what he calls ‘root identity’ – the essentialist conception of identity based on genealogy and affiliation – emerged out of the context of the brutal history of slavery, forced dislocation and colonisation of the Caribbean, and the enclosed space of the plantation where European colonisers, African slaves and indentured labourers from India and China were forcefully brought into contact. He developed his philosophy in response to the violent rupture and uprooting inflicted by slavery, focusing on the processes of cross-cultural encounters and mixing that took place in the Caribbean, challenging the totalitarian root (identity) that destroys and oppresses all that it perceives to be different from itself. Transcending the enormous loss and trauma of slavery, his theory and poetics emphasise the creative potential unleashed by the involuntary meeting and mixing of cultures and languages in the enclosed place of the plantation, which he compares to a laboratory of multilingualism.Footnote35

This coming together and mixing of different cultures that took place in the plantation is foundational to Glissant’s concept of métissage, which he defines as ‘the meeting and synthesis of two differences’, with creolisation being an extreme, ‘limitless’ form of it. Creolisation as an infinite process of mixing transcends the binary logic of self/other and ideas of cultural purity on which the colonial discourse is based. According to Glissant, we can conceive of creolisation as almost analogous to the idea of Relation.Footnote36

Here it is important to stress that for Glissant creolisation does not mean dissolving difference, and, in contrast to notions of the ‘melting pot’, he is very clear that creolisation does not mean ‘fusion’. To quote him: ‘In Relation, elements don’t blend just like that, don’t lose themselves just like that. Each element can keep, not just its autonomy, but also its essential quality, even as it accustoms itself to the essential qualities and differences of others.’Footnote37 While Glissant’s conception of creolisation as an open-ended process of cross-cultural entanglement is specific to and rooted in the Caribbean, he argued that processes of cultural mixing operate on a worldwide scale and that his theory could thus be applied to various contexts.Footnote38 Recognition and respect of the right to difference and opacity is one of the key attributes of Relation, encompassing ‘all the differences in the world’.Footnote39

Embracing the right to opacity and untranslatability of the other and challenging the idea of a ‘totalitarian root’ that destroys all that it perceives as different from itself, legitimising genocide, racism and colonial domination, Glissant’s poetics of Relation proposes a rhizomatic conception of identity (identité-rhizome),Footnote40 based on multiplicity and Relation, ‘in which each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other’.Footnote41 His radically tolerant conception of identity as constructed in relation (l’identité-relation) draws on Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the rhizome as an interconnected root (system) that unfurls infinitely in multiple directions.Footnote42 As a counter model to fixed notions of identity based on genealogy and blood lines, Relation transcends the binary thinking, categorisation and dehumanisation of the colonial apparatus. It allows us to imagine belonging and identity differently, not based on roots but in Relation, based on a model of the root that is at the same time singular and multiple.

In Surya Namaz, the return to my father’s birthplace of Karapınar follows the (blood) line of affiliation, and to some extent my journey to Turkey and engagement with the namaz, could be described as searching for and connecting with my ‘root identity’. As mentioned, this vertical movement of ‘affiliation’ has problematic connotations of ‘going native’ and risks falling into the trap of fetishising my cultural heritage in line with the artworld’s tendency to pigeon-hole culturally diverse artists, who are often expected to act as representatives of a particular culture, ethnicity or region. This assumption of a singular root is challenged by following the horizontal or diagonal movement of relation, ‘reaching out to meet other roots’ in the practice of yoga with Marisol.Footnote43

Marisol was born and brought up in Spanish Harlem in New York and is of mixed Puerto-Rican and Nigerian heritage. She renounced her religious upbringing (Yorùbá and Catholicism) and trained to become a contemporary dancer. Dissatisfied by having to move her body according to specific choreographic instructions, she eventually turned to the spiritual practice of yoga and, after rigorous training in India and the United States, found a new calling as a Mysore (ashtanga) yoga teacher. She is now based in Switzerland and continues her practice in Solothurn.Footnote44

Moving across cultures and continents, her transnational trajectory and mixed-race heritage could be seen as the embodiment of diasporic dislocation, hybridity and transcultural contact. In contrast to my aunt’s more linear affiliation with a ‘root identity’ (ethnic Turkic and Sunni Muslim), representing the fantasy of authenticity and tradition, Marisol’s multiplicity and hybridity become a site of reflection and projection of my own diasporic positionality. Moving between roots and routes, local and global, vertical and horizontal, the audio-visual representations of my multiple selves vibrate at different wavelengths and frequencies, transcending binaries. Neither here, not there. Neither this, nor that. Vibrating between three letters: a-u-m.

The final scene shows me sitting on a prayer rug, turning my head East and West, ending the prayer cycle following my aunt’s instructions.

Voiceover Standing, bowing, rising, sitting, turning East and turning West. Falling to prostrate. All repeated in cycles. I feel dispersed like soundwaves, travelling through space.

Sound travels through air, breath and speech. Going through our bodies and touching us at our core. Chanting a-u-m with Marisol and Allah Akbar! with my aunt, waves of sound leave my lips, vibrating through air, going through my body to touch and transform other bodies, becoming language. Chanting a-u-m with Marisol and Allah Akbar! with my aunt, I am transported across generations and continents, connected to my ancestors and others’ ancestors, temporarily belonging and undoing belonging by embodying multiple belongings, in motion and Relation with other bodies and voices, local and global, rooted yet rootless, dispersed and multiplied, like sound waves travelling through space.

I am writing these reflections while sat at my desk in Birmingham, listening to the soundtrack of Surya Namaz via my laptop speakers, travelling back in time to the making of the video. Watching my body moving from one position to the next, I am surprised by its flexibility and strength at the time of the recording. I am conscious of how much the body I am inhabiting has changed over the course of the years. Hunched over my desk, I am aware of my bad posture and can feel my back aching. I am trying to loosen my stiff neck and tight shoulders, moving my head sideways and my shoulders up and down while watching my fingers move to type these words on the keyboard. The pandemic, becoming a parent and taking up a full-time lectureship have had an adverse impact on my ability to continue a regular (physical) yoga practice, and while at times I find myself silently reciting the Fatiha, I have not been engaging in a regular namaz practice either. However, these movement sequences have become part of my body memory and I find consolation in knowing that they are accessible to me as embodied knowledge and fluid forms of posture practice.

Research, writing and art-making are not disembodied activities. My research interests in the body as archive, ritualistic practices and multilingualism have been directly influenced by my multicultural upbringing and family history of migration, and it is evident in the work itself that Surya Namaz was inspired by my encounters with different religious and spiritual practices, such as yoga, namaz and rituals of the Catholic Church. As Nirmal Puwar writes, ‘we are embodied beings as knowledge makers. Encounters, connections and relationships influence and impact on the research we undertake.’Footnote45 While these connections – the bodily encounters and positionality of the researcher – tend to be neglected or erased in more conventional modes of art-historical scholarship, taking an auto-ethnographic approach, as I have done in my attempt at writing with Surya Namaz, enables the researcher to reflect on biographical influences or the (artist’s or writer’s) body in the work itself.

In reflecting on the multiplicity of voices and encounters that have shaped the making of Surya Namaz, I have highlighted the potential of Relation to resist an essentialist conception of identity while exploring the (moving) body, ritual and movement languages as a diasporic archive and site of multiple belongings. As I have demonstrated, writing with the practice has the potential to push beyond the limits of language, thereby destabilising the hegemony of the written word. A practice-based approach allows for the incorporation and generation of other forms of knowledge, such as the aural, the retinal, the haptic, the verbal, the sensual, the corporeal, which have been marginalised and erased in dominant Western conceptions of the archive and archival studies. In writing with the practice, I propose a conception of the (diasporic) artist and researcher’s body as both ‘living archive’ and archivist, thereby conceptualising new forms of decolonial archival practice by centring embodied forms of intergenerational, ancestral and transcultural knowledge that transcend the imperial and colonial legacy of the archive and allow us to reimagine it otherwise.

Notes

1 Trinh T Minh-Ha and Nancy N Chen, ‘Speaking Nearby: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-Ha and Nancy N. Chen’, Visual Anthropology Review, vol 8, no 1, spring 1992, p 87

2 Deniz Sözen, ‘The Art of Un-belonging', doctoral thesis, University of Westminster, 2019, https://doi.org/10.34737/qv976

3 Avtar Brah, Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities, Routledge, London and New York, 1996, p 205

4 Trinh, ‘Speaking Nearby’, op cit

5 Ibid

6 Nirmal Puwar, ‘Carrying as Method: Listening to Bodies as Archives’, Body & Society, vol 27, no 1, 2021, p 4

7 While Hall refers to artists’ archives such as the African and Asian Visual Artists Archive, I have taken the liberty of transposing his argument on to my conception of the body as a living archive, a site of constant and infinite transformation. Stuart Hall, ‘Constituting an Archive’, Third Text 54, vol 15, issue 54, spring 2001, p 89.

8 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Eric Prenowitz, trans, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1996, p 4

9 Ann Laura Stoler, ‘Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance’, Archival Science, vol 2, 2002, pp 87–109, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632

10 Ibid, p 83

11 J J Ghaddar and Michelle Caswell, ‘“To Go Beyond”: Towards a Decolonial Archival Praxis’, Archival Science, vol 19, 2019, pp 71–85

12 Siobhan Murphy, ‘Writing Performance Practice’, in Michael Schwab and Henk Borgdorff, eds, The Exposition of Artistic Research: Publishing Art in Academia, Leiden University Press, Leiden, 2014, pp 177–191

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

15 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Towards a History of the Vanishing Present, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999

16 Édouard Glissant, Introduction à une Poétique du Divers, Gallimard, Paris, 1995

17 Ghaddar and Caswell, ‘“To Go Beyond”’, op cit, p 72

18 For an English translation see ‘The Pluralism Project’, Harvard University, https://pluralism.org/the-call-of-islam, accessed 17 October 2023

19 Interestingly, the root of the Arabic word adhan or azan (ezan in Turkish), the muezzin’s call to prayer, is ʾadhina, meaning ‘to listen, to hear, be informed about’. Another derivative of this word is ʾudhun, meaning ‘ear’. Muslim Central audio library, https://muslimcentral.com/audio/azan-ezan-athan-adhan/, accessed 17 October 2023.

20 Christine Caldwell, ‘Mindfulness & Bodyfulness: A New Paradigm’, Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, vol 1, 2014, pp 77–96

21 Tonia Sutherland, ‘Reading Gesture: Katherine Dunham, the Dunham Technique, and the Vocabulary of Dance as Decolonizing Archival Praxis’, Archival Science, vol 19, 2019, pp 167–183, at p 177, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09308-w

22 Marion Holmes Katz, Prayer in Islamic Thought and Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013, p 12

23 Lila Abu-Lughod, ‘Writing against Culture’, in Richard G Fox, ed, Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1991, pp 137–162, at p 140 and p 141

24 Here I refer to Trinh’s conception of the ‘inappropriate Other’ as the subject whose intervention ‘is necessarily that of both a deceptive insider and a deceptive outsider’. Trinh, ‘Speaking Nearby’, op cit, p 74.

25 Laura U Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2000, p xiii

26 Ibid, p 1

27 Akram Khan, 2006, cited by Cheryl Stock in ‘Beyond the Intercultural to the Accented Body: An Australian Perspective’, in Jo Butterworth and Liesbeth Wildschut, eds, Contemporary Choreography: A Critical Reader, Routledge, Abingdon, 2009, p 289

28 Hall, ‘Constituting an Archive’, op cit, p 90

29 Brah, Cartographies of Diaspora, op cit, p 193

30 Nav Haq, ‘Out of the Picture: Identity Politics Finally Transcending Visibility (Or: The Invisible and the Visible, Part Two)’, in A Kreuger and Nav Haq, Don’t You Know Who I Am? Art After Identity Politics, exhibition catalogue, M HKA, Antwerp, 2014; Hal Foster, ‘The Artist as Ethnographer?’, in The Return of the Real, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996

31 Spivak, Critique of Postcolonial Reason, op cit, p 6; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Sneja Gunew, ‘Questions of Multi-culturalism’, in Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, The Post-colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues, Sarah Harasym, ed, Routledge, New York, 1990, p 66

32 Spivak, Critique of Postcolonial Reason, op cit; Spivak and Gunew, ‘Questions of Multi-culturalism’, op cit

33 The notion of auto-orientalising draws on Edward Said’s conception and critique of Orientalism as a discourse of othering, which builds on an imaginary binary between (the colonised) East and the West, ie the Orient versus the Occident. Edward W Said, Orientalism, Pantheon, New York, 1978.

34 Glissant, Introduction, op cit, p 23

35 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, Betsy Wing, trans, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1997, p 74

36 Ibid, p 34

37 Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation, 2010, director: Manthia Diawara, Third World Newsreel, transcribed in Manthia Diawara, ‘Conversation with Édouard Glissant Aboard the RMS Queen Mary 2 (August 2009)’, in Christopher Winks, trans, The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Worlds, Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel, eds, ZKM-Center for Art and Media and MIT Press, Karlsruhe, 2013, p 40

38 Glissant, Introduction, op cit, p 15

39 Édouard Glissant, Philosophie de la Relation: Poésie en etendue, Gallimard, Paris, 2009, p 42, translation mine

40 Glissant, Introduction, op cit, p 132

41 Glissant, Poetics of Relation, op cit, p 11. In Poetics of Relation Glissant refers to the Bosnian and Rwandan genocides as recent examples of the brutality and violence arising from an assumption of a root (identity).

42 Following Deleuze and Guattari, ‘any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order.’ Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Brian Massumi, trans, Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp 5–6

43 Glissant, Introduction, op cit, p 23, translation mine

44 Marisol Figueroa Reitze, Öufi Yoga website, http://www.oeufi-yoga.ch/oeufiyoga-2/marisol/?lang=en, accessed 28 July 2023

45 Puwar, ‘Carrying as Method’, op cit, p 5