Abstract

Georgina Karvellas was one of the few women photographers documenting apartheid South Africa for several decades. She produced work for the fashion and music sector next to striking documentary work with a clear stance against the government’s segregationist policy. Inscribing Karvellas into the histories of photography, film and art, this article highlights the intersections of her work between commercial and political photography as well as between issues of gender, race and class through a careful reading of the various frameworks into which it has been placed and the reasons for them. As she worked at a time when the freedom of movement of South Africa’s majority population was severely restricted, a particular focus is on Karvellas’s transnational approach and the question to what extent her choice of commercial photography might have closed doors for her, such as inclusion in the artistic canon, while giving her greater freedom in crossing borders.

Georgina Karvellas was one of only a few women photographers documenting South Africa during the 1960s and 1970s. Overshadowed by the profound oppression of the apartheid government, this period has been described as a dark era for the photographic medium in South Africa.Footnote1 A time marked by strict political constraints, it saw a shift from the vibrant days of magazine photography in the late 1950s to the emergence of politically charged imagery in the late 1970s.Footnote2 There is little information about photographers who were active during this historical period, and even less about women photographers.

However, there are a few exceptions worth noting. The Cape Town-based photographer Anne Fischer trained two of the most important South African women photographers working at the time: Jansje Wissema, whose photographic career extends from the late 1940s to the mid 1970s, and Georgina Karvellas, whose work spans the 1960s to the early 2010s. While I treat the former in depth in my dissertation on the representation of women in photography in apartheid South Africa, this article focuses on the latter.Footnote3 Thus far, the work of the commercial practitioner and filmmaker has received no scholarly attention – a fact I want to redress by inscribing Karvellas’s important work into the histories of photography and of women working with the medium.

Information on women photographers who worked in apartheid South Africa is scarce, both in institutional archives and in the academic literature, and so my research predominantly relies on sources that are not typically used in art history, such as social media, websites, newspaper or magazine articles, audiovisual materials and first-hand interactions in the form of personal interviews and email correspondence. As such, my direct communication with Karvellas’s family is a vivid example of the investigative approach I use to explore the life and work of an overlooked and marginalised photographer.

I first learned about the existence of photographer and filmmaker Georgina Karvellas in an article by Kylie Thomas, which mentions her in one sentence.Footnote4 Trying to find out more about Karvellas, I searched library catalogues, archive repositories and the internet for traces of her life and work, and while the first two sources were not particularly productive, I came across several references on the World Wide Web, including an Instagram post by a ‘Greg Karvellas’, who was mourning the death of his aunt.Footnote5 After informing him of my research interest by email, it turned out that he really was Georgina Karvellas’s nephew, and he willingly gave me more information about his aunt’s life and work. Less than a year later I visited his family in Stellenbosch, in the Western Cape, and looked at parts of the long-time photographer’s extensive archive. For my dissertation research I used similar methods to trace, for instance, the biography and oeuvre of photographer Mavis Mtandeki through numerous interviews with her and the people close to her. Since many works by women photographers are not recorded at all or only inadequately attributed in library holdings and institutional archives, social media, oral history and contacts with close relatives can, as these examples illustrate, become indispensable instruments of research in a decentralised global art historiography that focuses on the links between photography and sound. By including archival and living sources that expand the visual–written dimension, a more diverse range of voices can be incorporated into the existing canon, enabling a more polyphonic historiography. This is particularly important for South Africa’s histories of photography. Patricia Hayes describes how prevalent photographs of Black women are in the photographic archives from the first hundred years of the medium’s existence, which stands ‘in striking contrast to the frequently stated problem of a lack of women’s “voice” to be found in the archive of texts’.Footnote6 Thus, for the writing of gender into current historiographies, one must rely on a broader range of methodologies and sources that allow for a form of ‘polyphony in the archive’.

Also required is an expansion of the artistic or photographic subject and related archives. In their seminal work Women and Photography in Africa, Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo and Kylie Thomas recognise the knowledge gap when it comes to women’s involvement with the medium on the continent. They propose that one way to fill this gap is to take the business side of photography seriously, in order to include hitherto little-known women actors. In doing so, they highlight the importance of women’s choices, both as photographers and as clients, for the development of the medium.Footnote7 Following a similar approach, I explore the intersections of commercial and political photography as well as issues of gender, race and class in Karvellas’s work through a careful reading of the various frameworks into which it has been placed.

Women Training Women

Georgina Karvellas, also known as ‘Bobby’, was born Georgina Marion Carvelas into a South African family of Greek descent in 1943.Footnote8 After completing her education, in 1961 Karvellas started as Fischer’s apprentice.Footnote9 She recalled: ‘When I left school I tried to get a job with Anne Fischer, a Cape Town wedding and portrait photographer. No luck, so I took a job in the book store below her studio… Two weeks later she came in and offered me a job.’Footnote10 Karvellas worked with Fischer for two to three years, first learning the workings of the darkroom and washing and spotting black-and-white prints before being sent to do her first shoots of smaller weddings.Footnote11 She described Fischer’s training as harsh.Footnote12 Afterwards, Karvellas moved between Cape Town and Johannesburg for family reasons – her parents had divorced, and while her mother moved to Cape Town, her father remained in Johannesburg, where Karvellas had grown up. During this time she worked as an assistant to advertising photographers John Rheeder in Cape Town and Aubrey Kushner in Johannesburg before starting to work independently as a freelancer in 1965.Footnote13

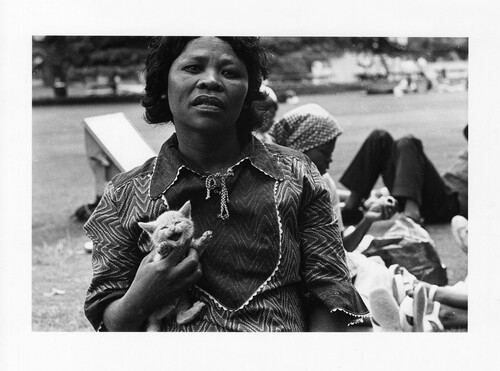

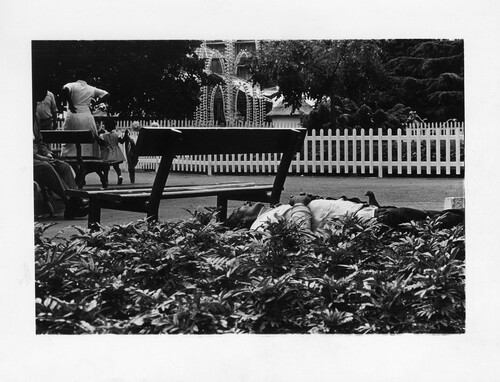

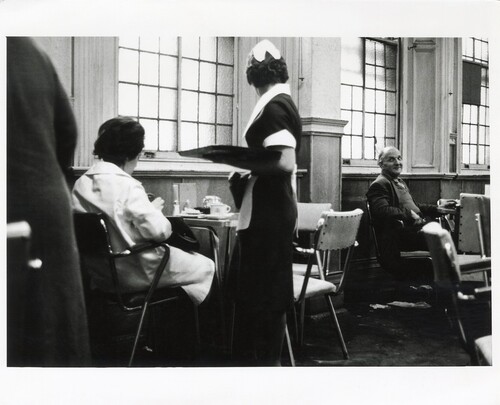

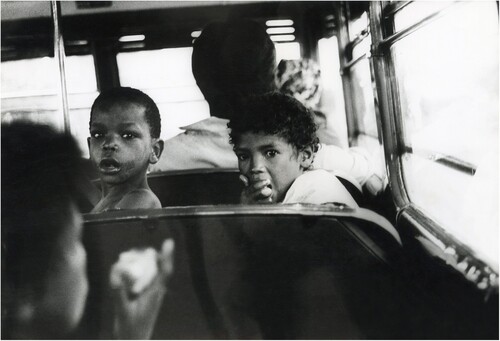

Two photographs taken during her early days as a photographer in Cape Town show Karvellas’s interest in the city’s people along the lines of colour, age or gender. Cape Town, Train Station, City Centre, Tearoom (1962) captures a sheltered interior where a seated, elderly white male café customer intensely gazes at a slim white woman in an apron, who faces him. Capturing the dynamic of the attentive gaze of the man and the woman’s body in motion, turned with its back to the viewer among the other café customers, Karvellas’s photograph records a special moment of pause and human interaction amid the hustle and bustle of everyday life. The photograph Cape Town City, Bus and Children, which is undated but was presumably taken around the same time Karvellas was living and working in Cape Town before moving to Johannesburg, is similarly instantaneous. It shows people of colour sitting on a bus from behind, focusing on two small children who are facing backwards, and thus turned to the camera, one of whom appears to be looking directly into the viewfinder, its mouth open, while the other stares absently ahead. Here also Karvellas captures with her camera a dynamic regime of clearly visible and withheld gazes in Cape Town’s crowded everyday life, which presents at the same time a moment of brief pause and clear social interaction. Both photographs display an attention to detail and interest in unfiltered facial expression while also revealing that, at a time of increasingly violent segregation of different groups of people according to racist classification and thus also economic and social class, Karvellas physically transgressed boundaries, using her freedom as a white woman to capture largely disparate sites, such as tearooms frequented by wealthier and older white people or buses used by the Black working class.

Georgina Karvellas, Cape Town, Train Station, City Centre, Tearoom, 1962, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Georgina Karvellas, Cape Town City, Bus and Children, undated (presumably early 1960s), courtesy of the Karvellas Family

This interest did not diminish after her move to Johannesburg in 1965, when she opened her first studio in Koch Street, directly opposite Joubert Park.Footnote14 Here she produced not only work for magazines as well as the fashion and theatre industry but also continued to pursue her own photographic interests, capturing the people who frequented Joubert Park during the 1970s. A newspaper article mentions these photographs and reports Karvellas’s thoughts on them: ‘There’s the shots taken in Joubert Park in the 1970s, of a happy racial mix of people – anathema then (“these pics weren’t posed – I used to love just walking around there taking photos”).’Footnote15 A newspaper article from 1976 highlights the similarities between her work and that of US-based fashion photographer Diane Arbus, ‘who turned to photographing “freaks” in Central Park with a toughness and compassion that left most people either moved or uncomfortable when society’s beautiful people and their glossy magazines finally sickened her’.Footnote16 Karvellas’s photographs of park visitors show similarly absurd moments outside the social norm. An example is a photograph of a Black woman holding a white kitten to her chest and looking directly, but not smiling, into the camera while the cat seems to be snarling at the viewer. Another photo shows a rather neatly dressed man lying on the grass next to or almost under a park bench, seemingly asleep, his hands folded on his chest. A person is sitting on a bench across from him, and a man, a woman and two children stand behind him. A pigeon peeking out from behind the sleeping man’s belly reinforces the absurdity of the moment depicted. So, while some park visitors use the grounds as intended, Karvellas, like Arbus, focuses on the most striking people and moments, capturing the bizarre aspects of the human condition.

Starting work just over a decade prior to Karvellas, Arbus began operating a commercial photography business together with her husband in 1946, in which they mostly produced work for the fashion industry. About ten years later she began to expand her repertoire to include street photography and longer photo spreads for magazines. In their article on ‘Women and Photography’, Tirza Latimer and Harriet Riches argue that the emergence of lifestyle and fashion magazines offered female practitioners new career opportunities in the profession, and thus, in some cases, further opportunities for their photographs to be included in the field of fine art, naming Arbus as an example.Footnote17 The transition from fashion to broader society portrait photography thus seems not to have been uncommon among women photographers and probably for primarily economic reasons above all, since further projects were only possible after one had established oneself as a practitioner in a profitable branch of photography.

South Africa’s Advertising World

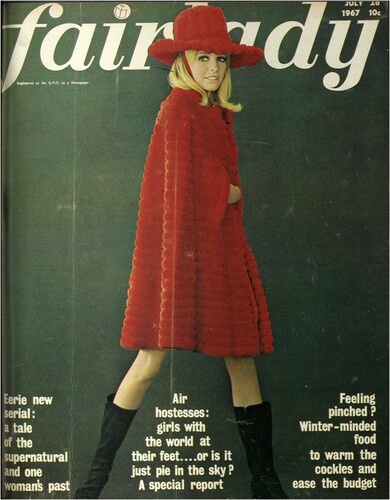

After all, what Karvellas mostly engaged in during the mid 1960s and 1970s, and what would give her a living, was commercial photography. In the late 1960s she was one of the best-known commercial photographers in Johannesburg.Footnote18 Her fashion and advertising pictures, which mainly showed women, appeared in numerous national publications, adorning, for instance, the covers and pages of numerous issues of the South African woman’s magazine Fair Lady. The July 1967 cover of the magazine, for example, featured a photograph by Karvellas of a young blonde woman in a bright red coat with matching hat and black boots just high enough to show a good part of her long, thin legs, which were in a wide stride, against an otherwise dark, featureless background.

Georgina Karvellas, Front Cover of Fair Lady Magazine, 26 July 1967, courtesy of the National Library of South Africa, Cape Town

This photograph well illustrates Roland Barthes’s remarks about clothing as difference, according to which the gap in clothing – that is, the parts of the body that are not covered but shown openly – is of great importance in fashion photography.Footnote19 The uncovered white legs take centre stage in this fashion photograph. Exposed between the high black boots and the red coat that only reaches to above the knees, the light legs together with the light face form a triangular composition. The light skin colour is of central importance here, as it contrasts strongly with the clothing shown and the dark background chosen. Despite rather wintry-looking clothing, Karvellas manages to depict a moment of eroticism in this fashion photograph through the staged gap in the clothing.

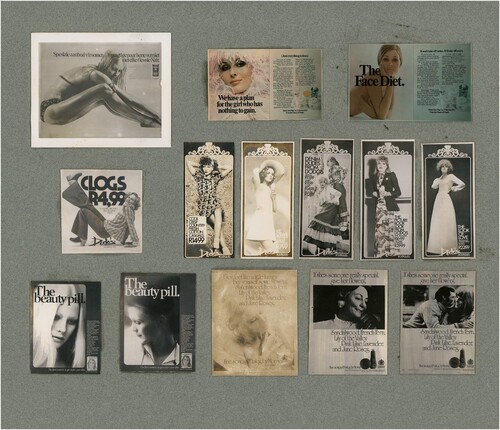

A look at other advertising photographs that Karvellas presumably compiled for a descriptive portfolio shows that her advertising images of women’s bodies contain not only more confident and detail-focused shots, in which the women look directly into the camera, but also figure-accentuating full-body motifs as well as rather reserved-appearing women who look down to the floor or to the side. In keeping with the respective consumer goods that these women’s bodies were meant to advertise, these photographs show how Karvellas made use of a full repertoire of both objectifying and empowering pictorial strategies.

Georgina Karvellas, Page of Karvellas’ Advertising Photography Portfolio, undated, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Most of the portrayed women are young, have flawless fair skin, are slim and wear blonde hair in fashionable hairstyles. Many more shots of this type can be found in Karvellas’s archive, reflecting the type of woman who was in demand on the South African advertising scene at the time. Yet, her photographs vary between close-up and full-body, people in action and alone, clothed or naked, and cannot be reduced to a specific way of depicting women’s bodies. Instead, they show Karvellas’s varied repertoire of expressions, which could be seen as a reflection of her own multifaceted experiences as a woman.

While Karvellas mainly photographed women, as this portfolio page shows, she did not fulfil the expectations that society had of her as a woman. A contemporary newspaper article describes ‘fashion photographer’ Karvellas as ‘someone who is more than careless about home comforts and meals’.Footnote20 Another rather harsh article states: ‘Talented the lady is: friendly and forthcoming she is NOT.’Footnote21 Karvellas thus openly failed to meet society’s expectations of her as a woman. And yet, in a conversation with her close friend Katinka van Biljon, whom Karvellas also photographed, she is described as ‘knowing how to draw out and celebrate women’s intrinsic beauty’.Footnote22 Furthermore, Juliette Leeb du Toit, who together with Kirsten Nieser started a comprehensive research and exhibition project on Karvellas’s work in 2018 – due to delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic and an end to their funding, the results were never published – told me that Karvellas was homosexual.Footnote23 Yet, what does it mean to take the photographer’s sexual orientation into account? How does it change art-historical research when identity politics mediated through personal conversations and anecdotal evidence influence our analyses of image productions? I would argue that, in Karvellas’s case, some but by no means all interpretations might change.

Working in commercial photography at a time when homosexuality was prosecuted in both the United States and South Africa, Karvellas could not live out her sexuality in public. Due to her profession, she had to mediate the implications of the omnipresent male gaze both in the sector and across borders, dealing with the possibilities and limitations of depicting women for a mass audience in a way that satisfied the capitalist motivations of clients and at the same time, if possible, conformed to her own conceptions of the representation of the female body – a balancing act that certainly led to tensions and ambiguous results, as illustrated by the portfolio page.

It is striking that only white women are depicted in this portfolio. Karvellas also produced fashion and beauty commissions with Black women, for example in a fashion shoot for the South African Wool Board in 1973, so why the women depicted on the portfolio page are exclusively white must remain open at this point. Still, one assumption can be made. Predominantly produced for the Johannesburg-based agency Grey-Phillips, Bunton, Mundel & Blake, one of the largest advertising companies in South Africa at the time, and partly published in national magazines such as Fair Lady in 1973, this collage of images paints a picture of a segregated South African society as the apartheid regime would have liked to see it.

Around the same time, Karvellas also photographed numerous famous Black South African singers, including Margaret Singana, Thembi Zikhali and Thandi Klaasen. The intimate head shots by Karvellas that adorn their records, such as her stylised portrait on the cover of Singana Gold from 1976 or her close-up portrait for Thembi from 1977, are a lasting testament to the close collaboration between a white photographer and a Black celebrity. In the following years and further away from the local music scene, Karvellas would continue to photograph both Black and white celebrities.

Capturing the US Music Scene

In 1978 Karvellas moved to Los Angeles to work in the music sector, expanding her repertoire with filmmaking.Footnote24 While she had primarily worked for South Africa’s fashion industry, in the US she ‘turned her talents to the world of music and recording stars’.Footnote25 Norman Seeff, who had worked in her studio prior to leaving his home country, was Karvellas’s entry point to the US and the reason why she went there.Footnote26 They both worked together and because Seeff was interested in film so Karvellas also started to work in this medium.Footnote27 A 1981 newspaper article states: ‘She [Karvellas] has been a protégé of Seeff’s for some years now, working in his studio and learning from him in a variety of ways.’Footnote28 Another time, Karvellas is reduced to ‘Norman Seef’s [sic] assistant’ when she is mentioned as the photographer of the Desire Wire album photo.Footnote29 Despite these belittling framings, Karvellas managed to make a name for herself in the United States, photographing and filming music stars while also shooting interviews with famous musicians for US television networks.Footnote30

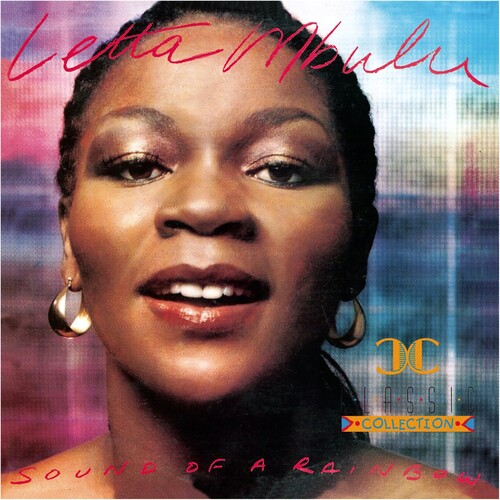

Karvellas also portrayed well-known South African female musicians who were living in exile due to the political situation, such as Letta Mbulu. For example, the cover photo of Mbulu’s 1980 album Sound of a Rainbow was taken by Karvellas in the US. She also photographed Black women from the US music business, such as Natalie Cole for her 1980s album Don’t Look Back. This extensive body of work across colour boundaries and geographical borders is astonishing, given the time in which the photographs were taken. The sheer number and diversity of her clients gives an indication of how well known Karvellas was among both Black and white female musicians in South Africa and the US, and the diverse people she dealt with in the 1970s and 1980s.

Georgina Karvellas, Letta Mbulu - Sound of a Rainbow, 1980, album cover, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Describing the effects of postmodernism on photography, David Bate argues that the medium’s fine art status based on opposition to commercialism was contested when, by the late 1970s, US-based artists started employing the norms of commercial photography, which occurred simultaneously with the breakdown of an opposition that had reserved the status of artist exclusively for men.Footnote31 Living in the US at the time, Karvellas thus probably experienced these new ways of accessing photography for women artists, and also how this changed the way the medium itself was handled and its areas of application.

This shift in overlapping conventions in fine art and commercial photography, with the simultaneous emergence of more women image producers, is also evident in Karvellas’s work at this time. With a keen interest in aesthetics and the incorporation of social commentary in her records of the music scene, she blurred the line between art and commercial or music photography. For instance, in March 1983 in Nashville an exhibition of ‘artwork from 41 album projects’, including ‘photographs, illustrations and stitchery used on various label LPs released during the past four years’, included works by Karvellas.Footnote32 This was also true of her moving images, for example the satirical music video Models Have Bodies.Footnote33 Subtitled A Fashion Show of the 23rd Century, the about four-minute video followed by two-minute end credits shows Peter Ivers’s band Vitamin Pink and a group of dancers perform in otherworldly and spacy costumes in an industrial hall decorated with white balloons. In the process of filming some of the scenes blur into abstract colour forms and the contours form bacteria-like structures that flicker across the screen, while other scenes are mirrored and reversed, reinforcing the absurd character of what is shown. This film received critical acclaim and was included in a two-week festival and subsequent touring exhibition of ‘25 different works of video art from the U.S., Canada, Europe, Asia and Australia’, of which the festival’s director stated: ‘Though the tapes mainly represent the avant-garde in serious conceptual video art… the increasing importance of rock video is reflected in this year’s festival.’Footnote34 Today, the video is part of the collection of the Long Beach Museum of Art Video Archive. Yet despite these credits, Karvellas’s authorship of the video goes largely unnoticed in current mentions, even though, or perhaps even because, her name has been misspelled as ‘Georgina Karelas’ in the end credits that appear under the creators and camera sections – a fact I will return to later.

Return to the Homeland

After almost six years, in 1983 Karvellas permanently returned to South Africa, joining the commercial television production company James Garrett & Partners as a director.Footnote35 In 1985 she opened another studio in Noordstreet right next to a taxi rank.Footnote36 In the years that followed she mainly shot still photographs but also continued to shoot music videos and advertising commercials.Footnote37 While David Goldblatt, whom Karvellas knew from her childhood and named as a major source of inspiration for her work, served as photo editor at Leadership and Siyaya, she had numerous photography jobs at these as well as other national magazines, including Marie Claire, Femina, Food and Home and House and Leisure.Footnote38 From 2002 to 2013 Karvellas worked as a studio lighting lecturer in the photography department of the private higher education institution City Varsity School of Media and Creative Arts, in Cape Town.Footnote39 She passed away in Cape Town in December 2021.Footnote40 After her time in the US, Karvellas thus continued to work as a freelance photographer for about another twenty years in her home country.

While her extensive commercial photography received much attention in the mass media, some was also shown in exhibitions during her lifetime. Shortly after her return to South Africa, Karvellas had two photography exhibitions at the Photo Gallery at the Market in Johannesburg.Footnote41 Her 1984 solo show ‘Commissioned Work & Other Vanities’ contained about thirty photographs.Footnote42 Her 1986 joint exhibition with Rodney Barnett displayed Joburg by Night – two distinct essays of photographs on the subject, which had been commissioned by the Photo Gallery at the Market.Footnote43 In 1997 her work was further included in the ‘Vita Art Now’ exhibition at the Johannesburg Art Gallery.Footnote44 While I did not find out much about the latter two exhibitions, it appears from news coverage at the time that Karvellas’s first exhibition at the Market included mostly commissioned work from the advertising, theatre and music industries.Footnote45

Camera as Activist Tool

Next to her commercial photography, Karvellas also produced some striking documentary work with a political edge. Produced at a time of escalating violence in South Africa, these records testify to her decidedly political stance against the apartheid regime.

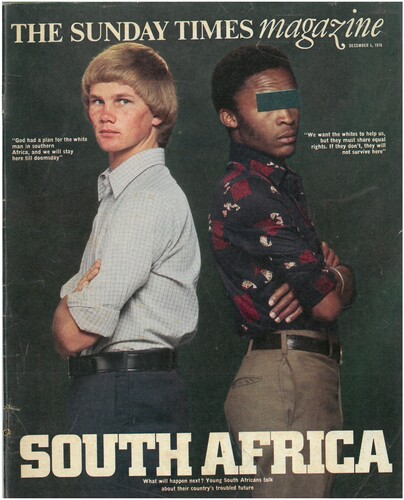

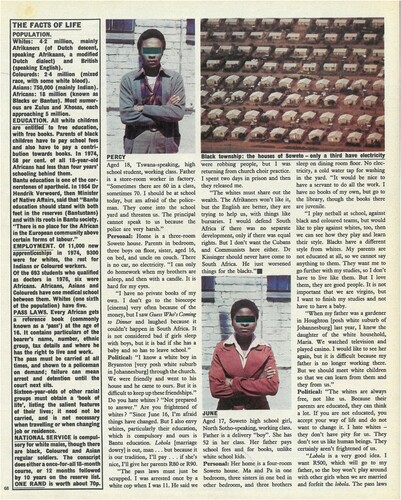

On 16 June 1976 approximately twenty thousand students rallied against the implementation of Afrikaans as the language of teaching in Black schools. The police responded with gunfire, resulting in the loss of 176 lives. This incident is now remembered as the Soweto Uprising. The writer and journalist Dennis Herbstein, who had left South Africa for London, commissioned Karvellas to document the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising through aerial and portrait photographs.Footnote46 Her resulting photographs not only made it onto the cover of the Sunday Times Magazine on 5 December 1976 but also into a fifteen-page article partly interspersed with page-sized advertisements.Footnote47 The article contrasts the views of the country’s youth across the colour divide via interviews and striking portraits.Footnote48 Each interview is accompanied by a photographic portrait of the young adult interviewee, comprising a frontal shot taken outdoors in front of a brick wall, building, park or garden. Most of these photographs are printed in colour and rather low quality. Interestingly, some of the Black sitters, but none of the white sitters, have a black bar in front of their eyes to prevent possible identification.

Georgina Karvellas, Front Cover of Sunday Times Magazine, 5 December 1976, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

This is also the case with the photograph on the magazine cover, which shows a young Black man and a young white man in smart casual clothes standing back to back and looking into the camera with their arms crossed. Here Karvellas implements what it was not possible to do in commercial photography in South Africa at the time, to show how political photography was, whether documentary or commercial. In a country that sought absolute segregation of Black and white people, the juxtaposition on the cover, presumably created by a photo collage, must have seemed like a political affront.Footnote49 The similarities in stature (about the same height and slim), posture (upright with arms folded in front of the chest and head turned to the side) and clothing (rolled-up shirt and belted suit trousers) of the two young men also emphasise their similarities rather than their differences. It is, above all, the bar on the Black man’s eyes that marks a difference between the two.

Of the article’s three aerial photographs, two are explicitly credited to Karvellas while the third is credited to Georg Gerster, a Swiss pioneer in aerial photography.Footnote50 One of Karvellas’s depicts a gathering of people next to a cemetery and fills the entire double-page spread that introduces the article. The other two are printed next to each other and are much smaller to increase the contrast of what is shown: Karvellas’s second photograph shows grey township houses in Soweto and next to it Gerster’s photograph is of large houses with pools and green gardens in the white suburbs of Johannesburg.

Georgina Karvellas, Sunday Times Magazine, 5 December 1976, page 68, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Georgina Karvellas, Sunday Times Magazine, 5 December 1976, page 69, courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Thus, Karvellas uses both close range to portray South Africa’s youth as well as the widest perspective the medium can offer her to picture the structures of Soweto’s settlement and graveyard. This enabled her to capture the socioeconomic fabric of South African society for an international audience. Soon afterwards she left the country, whether for personal and/or professional reasons due to the political tensions or due to the economic recession leading to fewer commissions must remain open at this point.

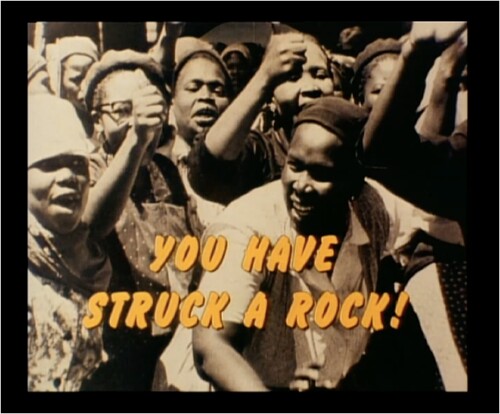

Before leaving for the US, however, she had already made plans to produce a documentary on women’s historic resistance against apartheid.Footnote51 She later returned to South Africa to shoot the film, on 16 mm in only three weeks, in Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg.Footnote52 The resulting 28-minute documentary You Have Struck a Rock, produced by Deborah May and the United Nations and released in 1981, describes the famous 1956 Women’s March on the Union Buildings in Pretoria and its aftermath through newly filmed interview and street scenes as well as archival film scenes, photographs and audio recordings. While some of the interview situations might be described as intimate, the focus of the film is a holistic analysis of the racist and sexist structures that prevail in the country, and this is achieved through the diversity of sources and overarching narration of Letta Mbulu, which provides further background information. As in the 1976 photo essay, this documentary work attempts a structural analysis of the inhumane excesses of the apartheid government’s segregationist policy. Not surprisingly, the documentary was banned in South Africa.Footnote53

Deborah May and Georgina Karvellas, You Have Struck A Rock, 1981, film, 28 minutes (still), courtesy of the Karvellas Family

Also, after her return to her home country, Karvellas pursued work of political significance. For instance, she acted as camera operator on a short film on illiteracy called Eyes to Read, Eyes to See and directed by Elaine Proctor.Footnote54 She also took photographs of the pregnancy waiting room at Hillbrow Hospital in Johannesburg to accompany a 1999 article on abortion in rural and urban South Africa.Footnote55 Still, back in South Africa she devoted most of her time to commercial music or advertising projects in photography and film. So what is the relationship between these political ventures and her commercial work? Which of these was important for her economic and mental survival? And what freedoms did she have as a photographer at that time and in South Africa and the US in general?

Moving across Borders

In a 1984 newspaper article Karvellas stated: ‘I’ve never been sure where the personal and the commercial work merge… and I don’t know how to make a division between them. I suppose you could say I take my commissioned work personally.’Footnote56 This statement makes it clear that in her practice she was concerned with meaningfulness and personal conviction. She was also aware of the effect her photographs had on viewers: as the article explained, ‘She believes that image-makers, especially in the commercial sector, have a certain responsibility. “One puts out images that are seen by thousands of people. One must take as much care as one can.”’Footnote57 Hence, she was aware of the impact not only of her political work but also of the mass-reproduced images she created for the advertising and music scene. In this respect, her reflections highlight the similarities rather than the differences between the various works and audiences and illustrate the power Karvellas was aware she had as an image producer. At the same time, as a photographer who worked for a time in the US but always had close ties to her home country, which was ruled by a repressive regime, she had to be aware of the possible consequences of her image production.

What could happen to photographers who brought the atrocities of the apartheid regime to the attention of the world becomes clear when looking at the biography of Karvellas’s contemporary, Ernest Cole. Born just three years before Karvellas, but a Black man in South Africa, Cole learned photography at Drum magazine. Shortly afterwards, he began documenting the atrocities of the regime and the catastrophic everyday conditions for the Black population over a period of almost seven years. In 1966 he smuggled the pictures with him when he emigrated to the US. In 1967 his photobook House of Bondage was published; it would become internationally famous (a new edition was published in 2022). The photographs’ publication had a massive impact on Cole’s life. In February 1968 he stated: ‘I knew that I could be killed merely for gathering the material for such a book and… I knew that once that book was published, I could never go home again so long as the whites, Boers or Englishmen, Nationalists or Progressives, remain in power.’Footnote58 Three months later the book was banned in South Africa. Cole never returned to his homeland and was unable to build on his early success in New York. Later he stopped taking photographs, became homeless and died of cancer in New York in 1990, shortly before the ban on his book was lifted.

Karvellas must have known about Cole’s fate and those of many other South Africans living in exile through her collaborations, for example with Mbulu, who for years produced music for a South African audience yet did not achieve comparable success in the US market as she did in her home country. Thus, while Karvellas stated in 1976 ‘I don’t enjoy shooting fashion’ and admitted in 1984 that ‘what I really wanted was to be a photo-journalist and imagined myself travelling the world for Life magazine’, she might deliberately have held back her urge to produce more openly political work after her 1981 documentary, in order to be able to return to her home country, as she did in 1983.Footnote59

Concluding Thoughts

Georgina Karvellas’s extensive oeuvre is characterised by an in-betweenness that makes any simple categorisation impossible. Instead, in this in-between of still and moving, colour and black-and-white, commercial and political images multiple nuances can be found that illuminate the circumstances of production, distribution and reception of her works, shedding light on global social, economic and cultural changes. Of course, such versatility is not peculiar to women, as most photographers, whether women or men, cover multiple applications of the medium during their career – a fact that has been partially erased by modernism. The aestheticised versions of her commercial advertising photographs and the politicised photographs for the music scene in South Africa and the US prove how seriously the photographer took both genres and how little attention she paid to the boundaries between them. At the same time, Karvellas explored the limits of her personal and political choices in her commercial and political work, to retain not only her economic freedom but also her freedom of movement at a time when the mobility of South Africa’s majority population was severely restricted. Focusing on predominantly commercial commissions throughout her career enabled Karvellas to not only make a living but also protect herself from serious persecution by the country’s Security Police. While the label ‘commercial photographer’ seemingly granted her freedoms during her lifetime, it now seems to deny her a place in the histories of photography or the artistic canon, given her current lack of attention in the historiography.

This neglect can also be connected to Karvellas’s recurring unmentioned authorship – an issue I have encountered not only in the case of the music video Models Have Bodies but also with the documentary You Have Struck A Rock!, where her authorship remains largely ignored or obscured, although she was one of the driving forces behind the film, as is evident, for example, from the scrapbook in her archive. In addition, while her work is included in numerous publications held by institutional archives, it is not specifically attributed to Karvellas, making a search for it particularly difficult. For instance, the National Library of South Arica does not list any work attributed to her despite holding most of the magazines which published her photographs for decades. Instead, Karvellas’s archive can be found mainly in the private property of her family as well as the archives of the University of Cape Town, which holds major parts of her archive in fifty-seven archival boxes, listing almost twelve hundred of her commissioned works.Footnote60 However, her non-commercial work does not appear in the institution’s finding aid, which leads to a much more one-dimensional classification of her diverse body of work as shown in this article. For the art historian, this non-attribution calls into question the self-evidence of archives. It further asks for an expansion of the research subject of photography, by dedicating itself to a larger image collection so as to enable a more comprehensive art historiography. I have tried to show what is gained by expanding the voices in our archives, not only by including commercial photography but also by considering one of the pioneering women filmmakers on the African continent, for the current global art historiography. Through research that draws on a broad range of sources and methods, I have tried to expand and truly consider the polyphony of the archive, which, in turn, allows for the writing of more inclusive and thus more complete histories of art and photography.

Further research into the complex life and extensive work of Karvellas is needed, to do justice not only to this important photographer and filmmaker by inscribing her work into the histories of photography and film, but also to other women working with these media. I hope here to have demonstrated Karvellas’s engagement with the current sociopolitical reality of life through the lens of her camera. As one of the few women working in the field of photography in apartheid South Africa during the 1960s and 1970s, she produced numerous commercials that were shown throughout the country, as well as crucial work that records and remembers the injustices of the apartheid regime in a unique way, both through intimate glimpses of the future visions of the country’s youth at a time when violence was escalating, and through one of the few comprehensive analyses to address the history of the women’s movement in South Africa in both image and sound. The example of Karvellas’s transnational career illustrates both the possibilities and limitations of women photographers who worked and lived in the repressive apartheid state, demonstrating the powerful and changing connections between still and moving images, consumer culture and resistance under the influence of capitalism and politics.

For their openness in talking to me about the life and work of Georgina Karvellas and showing me her archive, I want to thank Greg Karvellas, Laura-lee Michele Carvelas, Karalee Kleinschmidt, Bryan Longmuir, Katinka van Biljon and Wendy Manser, without whom this article could not have been written.

Notes

1 Darren Newbury, Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa, Unisa Press, Pretoria, 2009, p 164

2 The latter followed the pervasive violence of the 1976 Soweto Uprising and the extensive media coverage that accompanied it.

3 Marie Meyerding, ‘The Representation of Women in Photography in Apartheid South Africa’, doctoral dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin, 2023

4 Kylie Thomas, ‘History of Photography in Apartheid South Africa’, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2021

5 @gkarvellas, ‘I Write This with a Broken Heart – My Most Wonderous Thea Georgina Karvellas Has Left Us’, Instagram, 21 December 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CXwf_WXthqZ/, accessed 14 October 2023

6 Patricia Hayes, ‘Introduction: Visual Genders’, Gender & History, vol 17, no 3, November 2005, p 522

7 Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo and Kylie Thomas, ‘New Lines of Sight. Perspectives on Women and Photography in Africa’, in Darren Newbury, Lorena Rizzo and Kylie Thomas, eds, Women and Photography in Africa: Creative Practices and Feminist Challenges, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, 2021, p 8

8 Thomas, ‘Photography in Apartheid South Africa’, op cit. Her father had emigrated from Greece at age nineteen, changing his name to Carvelas in the process. The family has subsequently retained this name, except for Georgina, who took up the original Greek spelling. Laura-lee Michele Carvelas in conversation with the author, Stellenbosch, 19 April 2023.

9 Thomas, ‘Photography in Apartheid South Africa’, op cit. However, the sources for the year of her apprenticeship differ; see Jenny Altschuler, ed, The 4th Cape Town Month of Photography: Emergence & Emergency, South African Centre for Photography, Cape Town, 2008, p 160.

10 Wendy Ames, ‘Direct Current’, AD – Art Director, 1986, p 40

11 Georgina Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, April 2013

12 Carvelas in conversation, op cit

13 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

14 Bryan Longmuir in conversation with the author, Stellenbosch, 19 April 2023

15 Colette Braudo, ‘Clickety-Click: She Shoots from the Hip’, SA Photo, November 2000, p 92

16 Vita Palestrant, ‘Her Camera Captures the “Ordinary”’, Rand Daily Mail, 28 September 1976

17 Tirza Latimer and Harriet Riches, ‘Women and Photography’, in Grove Art Online, 20 September 2006, updated and revised 11 February 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2022250

18 Gavin Furlonger and Mia Ziervogel, ‘South Africa’s Top Photographers: Gavin Furlonger’, Dossier: The Photo Issue, winter 2012, p 103

19 Roland Barthes, The Fashion System [1967], Matthew Ward and Richard Howard, trans, University of California Press, Berkeley, California, 2006

20 Palestrant, ‘Her Camera Captures’, op cit

21 Josie Brouard, ‘In Focus’, The Star, 30 September 1981

22 Katinka van Biljon in conversation with the author, Stellenbosch, 19 April 2023

23 Juliette Leeb du Toit, email communication with the author, 14 June 2022

24 ‘Georgina Karvellas’, ArtistInfo, https://music.metason.net/artistinfo?name=Georgina%20Karvellas, accessed 14 October 2023

25 Brouard, ‘In Focus’, op cit

26 Longmuir in conversation, op cit; Braudo, ‘Clickety-Click’, op cit, p 93

27 Longmuir in conversation, op cit

28 Roy Christie, ‘Shy Shutterbug Has the Best of Both Worlds’, The Star, 23 November 1981, p 10

29 ‘Cidny Bullens Part One’, Yale Brothers Podcast, episode 59, 22 February 2022, https://yalebrothers.libsyn.com/episode-59-cidny-bullens-part-one, accessed 14 October 2023

30 Christie, ‘Shy Shutterbug’, op cit, p 11

31 David Bate, Photography: The Key Concepts, Berg, Oxford and New York, 2009, p 144

32 ‘CBS, CMF Team for Show: Album Cover Art on Exhibit’, Billboard, 12 March 1983, p 48

33 Braudo, ‘Clickety-Click’, op cit, p 93

34 Jack McDonough, ‘Truly Global Product: View 26 Programs at S.F. Festival’, Billboard, 19 December 1981

35 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

36 Carvelas in conversation, op cit; Longmuir in conversation, op cit

37 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

38 Ibid; Brouard, ‘In Focus’, op cit; Altschuler, 4th Cape Town, op cit, p 160

39 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit; Altschuler, 4th Cape Town, op cit, p 160. At this time her focus was a photography series titled ‘To Serve Only the Horse’, which investigated horse and cart scrap metal collectors who had been forcibly removed from District Six and continued to live around Cape Town, working in poor conditions in the city’s industrial areas. Altschuler, 4th Cape Town, op cit, p 83.

40 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit; @gkarvellas, ‘I Write This’, op cit

41 Altschuler, 4th Cape Town, op cit, p 160; Photo Gallery at the Market, ‘Invitation’, November, Bestand Fernand Haenggi, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, archive PA.156 6 011

42 Jennifer Pogrund, ‘Images of Georgina’, Rand Daily Mail, 24 November 1984

43 Photo Gallery at the Market, ‘“Joburg by Night” – Barnett & Karvellas – Two Essays in Photographs’, 1986

44 Altschuler, 4th Cape Town, op cit, p 160

45 Pogrund, ‘Images of Georgina’, op cit

46 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

47 Denis Herbstein, ‘Life and Death in South Africa’, Sunday Times Magazine, 5 December 1976

48 Ibid

49 One of the other rare occasions when Karvellas depicted Black and white people together are her Joubert Park photographs.

50 Herbstein, ‘Life and Death’, op cit, pp 66–69. There is also one more photograph of a demonstration in Soweto, which is credited to William Knosi from Gamma. Ibid, p 69.

51 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

52 Ibid

53 Braudo, ‘Clickety-Click’, op cit, p 93

54 Karvellas, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, op cit

55 Cathi Albertyn, ‘Abortion: Practice Limps behind the Law’, Siyaya!, 1999

56 Pogrund, ‘Images of Georgina’, op cit

57 Ibid

58 Ernest Cole, ‘My Country, My Hell!’, Ebony, February 1968, p 69

59 Palestrant, ‘Her Camera Captures’, op cit; Pogrund, ‘Images of Georgina’, op cit

60 Brian Michael Müller, ‘BV031 Georgina Karvellas Photographic Collection’, University of Cape Town Libraries, 2014