Abstract

Decolonial perspectives on art history have elaborated on the ways visual representations and documentary media are intertwined with the colonial project. The visual regime is associated with the coloniser's Eurocentric, objectifying and territorialising gaze. Can the visual still play a part in healing colonial wounds? The Karrabing Collective, a majority Indigenous group based in the Northern Territories of Australia, seems to engage with this question. Studying their video art as a form of invitation, I question how these works address inhospitable zones in the imaginations of the modern world and settler-colonial legacies. Extending Donna Haraway's metaphor of visiting as a mode of ethical attention, I posit that these works destabilise Western understandings of hospitality, memory, and image-making. I argue that their re-visiting of settler-colonial encounters rejects the primacy of archival integration and access, inviting the viewer to visit the lived space of peripheral vision that shifts between remembering and re-imagining.

Like the way we say, the country you go to, it has your sweat in it. It’s like that with the films. The stories become stuck inside you because the films have your sweat inside them.

Introduction: Settler-Colonial Wounds

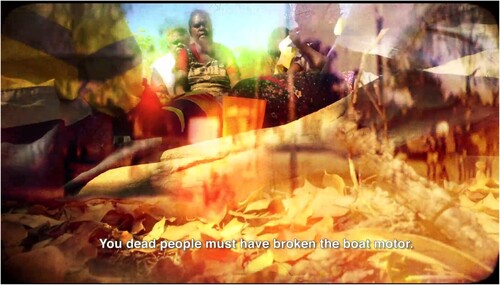

In my memory, it is hard to separate out different experiences of watching the Karrabing Collective’s films; they all feel interrelated in a process of getting to know the collective, attempting to navigate the unfamiliar spaces of their films and envisioning their lives and stories. I remember noticing a white woman in their midst and wondering how I should relate to her as a white, female, Dutch viewer. What is her role? And does her presence give me permission to imagine myself in the Collective’s company? For that matter, as they act out encounters with the settler state, such as phone calls with land rights officers and housing inspections, and also discuss ancestors and Dreamings together, which roles are the rest of the group playing?Footnote2 How do I relate to them? How can I interpret their stories, which are conveyed through improvised acting and editing and unscripted camera movements? Watching Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams (Karrabing Film Collective, 2016), I don’t know where the story is headed as a boat motor stalls and a group is shown floating out at sea. And I don’t know in which time period the situation is meant to take place when a group of walking, speaking ancestors is shown overlaid on impressions of a landscape in the same film. Every time I watch the Karrabing Collective’s films, I ask myself how much of my own interpretations and experiences I can bring to these images. By extension, I ask whether non-Indigenous perspectives have a place in these stories.Footnote3

I also remember seeing at least six or seven members of the Collective on stage after a screening at Tate Modern in 2017. There was something positively disruptive about this attempt to hold a Q&A with a group of Indigenous people and one white anthropologist, all related in opaque ways, talking through each other, and filling in each other’s sentences.Footnote4 It resonated with a sense that their kinship could make an inhospitable space hospitable. Their common language seemed to be present as much in their gestures and movements as in their speech: watching collective members negotiate who would sit next to whom, who would speak next, when to laugh at an inside joke or ignore a question altogether felt like watching the unfolding of an embedded landscape of relations. This landscape is an extension of the lived, ancestral and historical environment that appears in their films. Gathering these remembered images of the collective’s practice, I cannot conclude that they give me easy access to their way of living or their history. Their works cannot be contained within the ethnographic categories of visibility, which tend to present the audience with a systematic mapping of a strange and distant place or an encyclopaedic archive of threatened traditions. Rather than practising image-making for simple individual consumption, they seem to communicate a more complex vision of communal hospitality.

The Karrabing Collective is a media collective of thirty to seventy members, their constellations changing over time, most of whom are based in the Northern Territories of Australia. Initiated in 2008 as a form of grassroots activism, the collective approaches filmmaking as a mode of self-organisation and an investigation into conditions of inequality. It is majority Indigenous but also transcultural, as it includes white American anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli, who has been collaborating with the group for many years. The name Karrabing means ‘low tide turning’, and as member Rex Edmunds states: ‘Karrabing, it’s like we’re growing up in a big family group, with different families and tribes in our area, from around the coastal areas.’Footnote5 With their video works and installations, the collective aims to expose the ongoing influence of colonial power over their lives. Yet the history of their medium of choice is closely intertwined with the history of settler-colonial violence. Film and photography have enabled Indigenous images, objects and lands to be appropriated for Western institutional narratives and archives for centuries. Taking this into account, can visual media still play a part in addressing colonial violence or healing colonial wounds? What role does the viewer play in unlearning colonial ways of seeing? How are the Karrabing Collective engaging with moving-image work in a way that resists ongoing colonial paradigms of universal access and limiting representation?

In this article I will use the term ‘peripheral visiting’ to think through the ways in which the work of the Karrabing Collective can reshape our understanding of visibility in relation to kinship and memory. Moving away from the idea that the central political power of visibility lies in increased representation of social majorities on Western media platforms, I concentrate on collaborative image-making and practices of intergenerational and transcultural healing.Footnote6 The notion that the historical and contemporary colonial divide calls for imaginative forms of healing is drawn from Walter D Mignolo and Rolando Vázquez’s conception of the ‘colonial wound’, in which the colonial wound encompasses all that the rhetoric of modernity, with its promises of progress, edification and enlightenment, attempts to hide – the logic of coloniality and its processes of ‘expropriation, exploitation, pollution and corruption’.Footnote7 It touches on the disjunction between lives framed by modernity and those lived under coloniality, as well as the erasure of other ways of being by the processes of modernity/coloniality.Footnote8 The first step in pluralising modes of being in the world and healing the colonial wound is an awareness of the limitations of modern aesthetics. As Mignolo and Vázquez observe, ‘Modern aestheTics have played a key role in configuring a canon, a normativity that enabled the disdain and the rejection of other forms of aesthetic practices, or, more precisely, other forms of aestheSis, of sensing and perceiving.’Footnote9 As aesthetics colonises other conceptions of time, space and reality, it creates wounds in the shape of damaged or erased forms of living together.

Decoloniality involves refusing the universalising tendencies of modernity, and this includes ‘delinking’ from modernity’s totalising institutions and systems of meaning.Footnote10 This delinking can be practised by Indigenous, settler, Western and non-Western people in different ways, by recovering and elaborating a plurality of locally embedded alternatives.Footnote11 Referring to the use of Renaissance perspective as a form of imaginative enclosure in modern aesthetics, Mignolo and Vázquez call for an ‘overcoming of the aesthetics dominated by the gaze and a move toward the aesthesis of listening’.Footnote12 This implies that central vision, with its limited field of focus, objectifying gaze and assumption of an individual viewer, has become an inhospitable zone. The Karrabing Collective describe their practice as a commitment to ‘an ancestrally present way of belonging to each other, the land and the more-than-human beings who travel across it’.Footnote13 Yet their work is also shared with the audiences of international film festivals and European museums dedicated to modern art. Is this an example of Indigenous images being appropriated as a symbol of inclusivity and globalised identity within a modern, Eurocentric view of the world? In resisting colonial paradigms of access and representation, I argue, their work creates invitations to unlearn the worldviews of modernity/coloniality and heal colonial wounds, for viewers of both the social majorities and social minorities, and in what follows I expand on the ways in which it relates to practices of hospitality. Approaching vision from the peripheries of the epistemological frame of modernity/coloniality, the works of the Karrabing Collective connect to a wider proposal for thinking through an aesthesis of peripheral visiting that can pluralise our understanding of image-making.Footnote14

Aesthesis, Ethnography and the Visual

Mignolo and Vázquez posit that ‘Decolonial aestheSis starts from the consciousness that the modern/colonial project has implied not only control of the economy, the political, and knowledge, but also control over the senses and perception.’Footnote15 Cultural institutions such as the museum, film collections and archives are linked to the function of aesthetics as what Jacques Rancière has called a ‘policing’ rather than ‘politics’ of the sensible.Footnote16 Policing the sensible involves making divisions between who and what can be perceived, and how. Rather than enabling a multiplicity of experiences to dialogue, the universal canon of modernity establishes a fixed standard of expression. Once an object is placed within the universal narrative of modern art or human civilisation, its other stories, interpretations and lineages are erased. The history of modernity is commonly presented as one of increasing knowledge and technological innovation. This includes the establishment of museums as institutions for the classification and display of knowledge, and the invention of visual techniques such as photography and film as technologies for the accurate representation of reality. As scholars such as Ariella Azoulay and David MacDougall have discussed, the modern age also saw the establishment of new sciences such as ethnography and anthropology, which were integral to the colonial project of hierarchically classifying humanity into races and types.

Ethnography, museums and archives also connected the use of visual and documentary media to the establishment of a racial geography that catalogued ‘peoples of all lands’.Footnote17 This geography had a temporal dimension, which projected Western European societies as the most evolved and advanced in comparison to ‘primitive’ colonised countries. The images did not show peoples’ embedded connections to the lands they inhabited. Instead, they created a map of territories to be accessed from a particular point of view, namely that of visual discovery. The Doctrine of Discovery was used to separate so-called civilised and primitive peoples, and to give the former custodianship over land inhabited by the latter.Footnote18 We can argue that the logic of preservation is an extension of this doctrine, as it is used by museums and archives to justify the extraction of images and objects from other lands and transfer them for care in Western institutions. The underlying assumption, still present in restitution discussions today, is that looted objects and images are safer in modern, scientific settler-colonial institutions than in the lived environments of their cultural origins. Furthermore, as Azoulay has argued, these same practices work by ‘anticipating the extinction of people or of their art and “rescuing” it before its planned disappearance’, so that documentation and collection activities are structured by future violence.Footnote19

Representation, in the tradition of modernity/coloniality, stands for entry into a particular canon of values and access to a particular view of the world, at the cost of other values, views and life-worlds. The risk of representation includes the risk of limiting a community’s lived experience, past wounds and future possibilities to the Eurocentric archive. In this respect, it is interesting that Karrabing’s films are not set in a single time or space. Although their works could be described as counter-narratives or counter-images to settler-colonial stereotyping and misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples, a more apt characterisation might be that they generate a ‘lived’ counter-space of hospitality. Henri Lefebvre uses the term ‘counter-space’ to describe resistance to the abstract space of capitalism and neocolonialism and its erasure of historical uses, through sites where the contradictions of social relations on a local, human scale are operative.Footnote20 This counter-space is not limited to a single perspective or universalised view of the world. A video such as When the Dogs Talked (Karrabing Film Collective, 2014) weaves together discussions between Indigenous adults on the importance of preserving government housing versus sacred land and attempts by their children to interpret ancestral wisdom in their contemporary life. In Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams the protagonists negotiate the ongoing presence of Christian moral codes and settler-colonial laws in their everyday lives while interpreting past events through ancestral presence and conversation. As I will explore, the use of visual media in this way is connected to an experience of place that is embodied and can shift between the lived temporalities of remembering, attending and imagining.

Encounters, Archives and Lived Spaces

Returning to early examples of the colonial encounter, or so-called discovery, in the Western archive, these images often feature colonisers setting their first steps on Indigenous land and being greeted either by welcoming gestures and gifts or violent resistance. In both cases the framing of the scene is one that erases the historical and lived cultural context of local relationships with the land. Analysing images of ethnographic encounter in terms of modernity/coloniality’s aesthetic, I argue that they are focused on relations of access and exchange. It is through the coloniser’s arrival that the land is included on the world map. In fact, the land is often shown as a coastline, with boats that denote the means of travel and navigation. The visual act of mapping displays both its methods and the right to enter the land by those who have ‘found’ it. Furthermore, the act of mapping can be seen as a gift: these new lands and their inhabitants are being brought into the geography of civilisation. The colonisers are often portrayed with other symbols of the civilisation they bring. These include modern weapons, the crosses of Christian religion and flags of European nations. Indigenous peoples are mostly depicted as offering the fruits and riches of their land in exchange. At times, also, we see images of the rejection of colonial access, with violence its inevitable consequence. Either way, the logic of exchange takes over the representation of these geographies.

Theodor de Bry, Columbus landing on Hispaniola, Dec. 6, 1492; greeted by Arawak Natives, 1594, engraving, collection US Library of Congress, public domain

Even in more recent practices, such as participatory documentaries and Indigenous media, we can argue that an encounter is staged between the camera and the people filmed.Footnote21 In these cases ideas of access and exchange are still associated with the use of documentary media. Within the epistemological frame of modernity/coloniality, Indigenous peoples provide the viewer with so-called authentic images of Indigenous life and expression in exchange for access to modern technologies and institutional platforms. However, we can question the inevitability of this relationship, moving from a logic of ‘owning’ to ‘owing’, as advocated by Mignolo and Vázquez.Footnote22 One of the examples they give of this kind of shift is moving from a position of speaking for the other to a position of listening to the other. In the case of visual media, I suggest, an option can be to move from the position of viewer in an abstract representational space to the position of visitor in a lived counter-space of hospitality.

In a space of lived relations, the disjunction between lives framed by modernity and those framed by coloniality can be felt. In the representational space of the encounter, the viewer is assumed to take up a position that coincides with the Western ethnographer’s ‘ciné-eye’ of discovery.Footnote23 The viewer as passive consumer is placed at the centre of the experience and provided with images of another world to add to the imagined global archive of peoples. As Trinh T Minh-ha notes in relation to the documentary norm,

the viewer, Everyman, continues to be taught that He is first and foremost a Spectator. Either one is not responsible for what one sees (because only the event presented to him counts) or the only way one can have some influence on things is to send a monetary donation… What is presented as evidence remains evidence, whether the [filmmaker’s] observing eye qualifies itself as subjective or objective.Footnote24

In the documentary norm, the viewer is trained to see the other’s land as an inhospitable zone, separated from the possibility of lived relations. Even when we see images of lived experience, the camera and aesthetics of viewing police the divide between subject and object. The product is an image as evidence of an event that is already historicised, separated from the viewer by the expert eye of the camera. In this case, the image functions as archival in the way Derrida describes; as central to the actualisation of the law and connected to ‘an irrepressible desire to return to the origin’.Footnote25 Derrida’s analysis of the archive connects the idea of the origin to a place of commencement and commandment, ‘from which order is given’.Footnote26 Within this frame of understanding, the image of the colonial ‘other’ always returns to the original moment of their documented ‘discovery’ and their legalised separation from their lived experience of the land by Eurocentric forces of authority.

In the work of the Karrabing Collective, the image does not separate the land from the lived experience of its inhabitants. Rather, in establishing a moment and place of authority, members of the Collective describe image-making in terms of mingling with the land. As Natasha Bigfoot Lewis reflects, ‘the country you go to, it has your sweat in it. It’s like that with the films. The stories become stuck inside you because the films have your sweat inside them.’Footnote27 Through the process of returning to lived space, the image-makers reaffirm their kinship with the land, with each other and with their ongoing stories. The image becomes an element of kinship, another way of making oneself visible to ancestors in this space. As members declare in Staying with the ancestors (Karrabing Film Collective, 2020), ‘you have to sing out first, before you go back to your country. Let the ancestors know you are there.’Footnote28 In lived space, access is not guaranteed by a lineage of ownership traced back to an authoritative origin, and relationships of hospitality must be tended to.

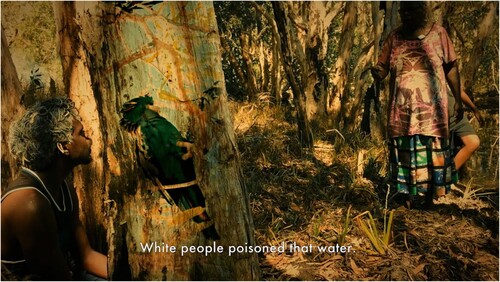

Reflecting on this relationship in Keeping Country Open (Karrabing Film Collective, 2020), they share: ‘When people don’t go back and mind their country properly, don’t go back and attend to their ancestors. Countries shut themselves up. They hide everything.’Footnote29 A film such as The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (Karrabing Film Collective, 2018) does not simply attempt to document these traditional beliefs while foreshadowing their eventual extinction; it can be regarded as science fiction, transporting the viewer into a time in the future when settler extractions have poisoned the land and only Indigenous people can survive outside. In the film, when the white people try to extract an antidote from Indigenous bodies and lands, the ancestors turn away. While this presents an image of a land increasingly precarious to life, the act of filming is itself a way of keeping the relationship to the land and the ancestors alive. Rather than the visual being used to document an essential relationship to land along a genealogy of primitive to modern, image-making is used as an act of attentive presence and collective imagination.

Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland, 2018, HD video, sound, 26ʹ29ʺ, film still

The image is not produced solely for the Collective, their ancestors or for Indigenous peoples. But as a guest in a space of lived relations, the viewer cannot assume that the rights to ownership of the land and authorship of its images exist in the conventional representational sense of encounter and exchange. A viewer who has been trained to see through modernity/coloniality’s lens might be disorientated by the absence of hierarchical origins and progressions. For example, in When the Dogs Talked and Windjarrameru, The Stealing C*nt$ (Karrabing Film Collective, 2015) the films’ protagonists come across signs of the representational space of settler appropriation such as fences, warning signs and permits. These signs do not determine the narrative’s progression in the expected direction, however. We are shown how these blockages and limits to movement are interpreted differently for lives framed by coloniality. Fences around private property indicate stolen lands, warnings not to enter areas contaminated by radiation point to zones of protection from corrupt police, and mining permits caution against poisoned food and water. From the settler state’s point of view, these markers of representational space coincide with the edges of civilisation, relegating Indigenous people’s lives to the peripheries of the living and liveable world. Shifting to the position of the visitor, however, we might see and hear that the Karrabing Collective’s relationship to place is shaped by movement and presence. It involves attending to traces in the landscape and messages connected to their ancestors as well as to signs of humans. In their movements and travels, questions of legal or illegal access linked to the logic of land ownership are trumped by questions of hospitality and memory tied to reciprocity with the land.

Travelling Visions

The Karrabing Collective’s approach to collaboration is also important for the process of delinking from modernity/coloniality’s way of seeing the land and each other. As mentioned, karrabing means ‘low tide turning’ or ‘tide out’ in the Emmiyengal language. The collective brings together different groups and families, who have their own stories in relation to the land but are all connected to the same coast. This coast is not a border in the sense of modernity/coloniality, which would be mapped as a fixed line and used to designate ownership. As Rex Edmunds observes, ‘White people introduced the idea… forced people to say that the land is just for that people… Everyone’s a traditional owner of a little bit of land.’Footnote30 Instead, the Karrabing Collective’s reference to the tide contains an acknowledgment of the living, shifting agency of the relationship between land and water, humans and the environment, the past and the present. The spontaneous nature of the group’s practice is led by the act of visiting the country and telling different members’ stories in relation to a place and event, interweaving different plot lines and perspectives. Through memories pieced together from different members’ stories, ancestors also play a part in this travelling collaboration. The ancestors’ voices emerge at the intersection of different perspectives in time and space, rather than being claimed by a single spokesperson.

Rejecting the politics of separation installed by the settler state, the Karrabing Collective enacts a fluid vision that allows space for complex relations between generations, families, language groups and cultures to develop. While the use of film as archival documentation produces and excavates an event that is temporally limited, this fluid vision is part of a travelling movement that enables living interactions between the past and the present. As member Gavin Biannamu states, ‘we come to know the places and Dreamings because we come to know we are still there and we are still continuing the story… the story is still there. If you go there you can see it – right there, staring at you. No matter what form of transport you want to go, by sea or by air, or by car, you can see it.’Footnote31 Thus, the story of The Mermaids, where the land has been poisoned by white settlers, is a vision of the future that is read in and through the traces of the past and the present. Like many of the Karrabing Collective’s other films, the story evolves through conversations between different generations, as the young protagonist, Aiden, travels with his father and brother across their country. In their attempt to interpret the future and possibilities for survival, they point out signs in the landscape and ask questions. Are the mermaids part of an ancestral world threatened with destruction? Do they continue to exert their own power? Or, are they collaborating with the settlers to kidnap children for experiments? Aiden’s perspective, as a young man who was taken by white people as a baby to be part of a medical experiment, is just as important to these dialogues as that of the two older men, who know stories of the ancestors and Dreamings. Just as peripheral vision registers cues at the edges of our visual field that trigger us to follow a dash of movement or glimpse of colour, seeing becomes a trigger for listening and travelling through different space-times. In the film the edges of the civilised world, the ‘outside’ of the hospital, where experiments are carried out, becomes the place from which to interpret the future in collaboration with different visions from the past.

The idea that a story exists in a place at multiple times and can be seen even when approached from several perspectives is very different from the modern archival idea that the image of a place fixes it to a singular event and division of relations. As Derrida observes regarding the principles of commencement and commandment, ‘archivization produces as much as it records the event’.Footnote32 Not only does the archive produce the event; it also produces a privileged perspective from which to access its account. This privileged perspective is one of authority, which centralises a particular experience of the event while erasing other possible relationships to it. The Karrabing Collective’s approach to the event as a continuing story removes the focus from the authorship and authority of images, on to the actions and attention needed to allow this story to remain open. This includes welcoming other perspectives to this story, even from those who might be considered outsiders to a traditional group.

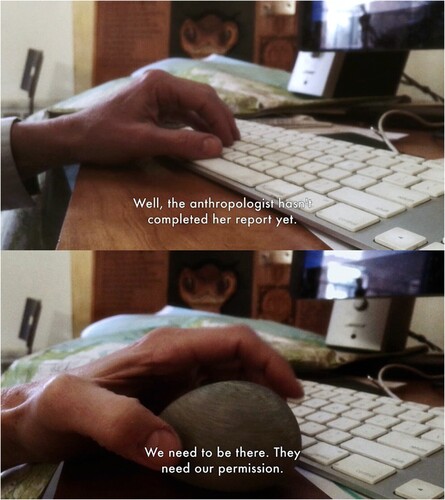

Thinking in settler-colonial terms of origins and ownership, the role of Elizabeth Povinelli in the collective would be that of an authority or expert. This role assigns authenticity and truth to knowledge from a seemingly neutral, objective and global position. In the logic of the colonial encounter, the Western settler perspective is the only one that counts, as it represents inclusion in a universal world view. As Azoulay has argued, the position of the expert is another hallmark of modernity, established alongside Western institutions and at the expense of the owners of traditional and lived knowledge.Footnote33 It is not surprising, then, that the Australian government has required all Indigenous land claims to be ratified by Western-trained anthropologists and lawyers. Functioning as gatekeepers, these authorities and experts register the colonised other’s activities and ratify them for inclusion in the representational archives of modernity/coloniality.

Povinelli’s membership of the collective can be understood as a refusal to be defined by this relationship of expertise through extraction. Rather than becoming the authority of the ‘real’ by taking on the role of the commissioner, judge or archivist of an authentic traditional image, Povinelli participates in a process of belonging to the land through visiting it and travelling through it. She is a participant in the storytelling, often acting in the role of the berragut (‘white person’, ‘European’, ‘non-Indigenous person’), for example as a miner or as a zombie in The Family (Karrabing Film Collective, 2021). This way of working allows the Western perspective, and its violence, to be acknowledged as part of an ongoing story while interpreting it as part of a living archive with lessons for community survivance.

The term ‘survivance’ is used by Anishinaabe theorist Gerald Vizenor to describe ‘an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories’ and ‘renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry’.Footnote34 The Karrabing Collective’s stories do not exist merely as a reaction to settler violence, but as a continuation of evolving forms of kinship, which circumvent the racial and cultural binaries of colonialism. This does not mean that the shifting and transcultural composition of the group is free-floating, however. The emphasis on active presence involves responsibility for keeping both meaning and memory open and allowing multiple voices to be heard. The number of actors and participants in the Karrabing Collective changes with each project, but it is always majority Indigenous. And there is an acknowledgment of the different pressures enacted upon white and Indigenous members of the group in the agreement that Povinelli will contribute financially to their productions. In this way individuals are in active dialogue and there is an ongoing acknowledgment of pressures and obstacles of colonialism.

The Collective’s stated aim to ‘reject the idea that you are either on your own or you are in an undifferentiated space’ functions as a reminder that the land is constantly being shaped by and shaping different relational pressures.Footnote35 It is the land that can decide not to respond, to hide, not to continue the story in this moment or with this constellation of perspectives and agencies. Not all visitors can see the same things, and some see more than others. This is an insight reflected in the first credit line of Aiden in Wonderland: ‘starring the mermaids, those who see them and those who don’t’.Footnote36 The existence of different lines of sight is connected to the responsibility to find intersecting perspectives. In the Karrabing Collective’s travelling vision, one can be an outsider and still receive hospitality, but one’s ability to see is not connected to the right to take an abstract position of authority or extraction outside of lived space. Possibilities for vision, movement and storytelling must continuously be negotiated with the land and its human, non-human and more-than-human inhabitants. There is no single point of overview or authority that can be claimed in relation to this process of negotiation. For this reason, there is also no single claim to authorship that can be made in the Karrabing Collective’s works. Their process of creating and envisioning can be understood as one of owing rather than owning.

Visiting and Hospitality

The credit line quoted above, ‘starring the mermaids, those who see them and those who don’t’, could also be understood as an invitation to the viewer to reflect on the gaps in their own frame of vision, and to attend to others’ interpretations of what might only appear at the edges of that frame. This would require us to approach their images without the expectation of being granted full and transparent access to their content. How can non-Indigenous viewers retune our potential to be present to the kind of visual aesthesis the Karrabing works present while acknowledging that we can never fully inhabit their perspective? The feminist scholar Donna Haraway seems to be thinking about this question when she describes the work of philosopher Vinciane Despret as a form of politeness while referencing Hannah Arendt’s use of the term ‘visiting’. Discussing Despret’s reflexive ethnology of bird scientists interpreting the behaviour of babblers in the Negev desert, Haraway notes:

In every sense, Despret’s cultivation of politeness is a curious practice. She trains her whole being, not just her imagination, in Arendt’s words, ‘to go visiting.’ Visiting is not an easy practice; it demands the ability to find others actively interesting, even or especially others most people already claim to know all too completely, to ask questions that one’s interlocutors truly find interesting, to cultivate the wild virtue of curiosity, to retune one’s ability to sense and respond—and to do all this politely!… Visiting is a subject- and object-making dance, and the choreographer is a trickster.Footnote37

From a decolonial perspective, visiting requires delinking from modernity’s colonisation of the senses and embodiment. When thinking in terms of the colonial encounter, interest in an image of another society or culture implies a connected interest in ownership, appropriation and extraction. The aesthetic of the encounter is repeated to train an expectation of return on this investment and to condition the viewer’s senses to identify with the coloniser’s interest. The type of visiting that Haraway describes suggests the need to resist the aesthetic of representation that confirms information about ‘others most people already claim to know all too completely’. This description could fit both the so-called othered peoples, whose identities are transcribed in the colonial archive, and the seemingly neutral position of the observer in the modern world of vision. Peripheral visiting involves stepping over an imaginative spatial threshold and having to reorientate and retune the senses in response to surroundings which are not one’s own.

Peripheral visiting also involves considering what might interest one’s interlocutors, what might invite different interpretations, extended dialogues and shared experiences rather than what might entice an economic exchange. Seeing and viewing become processes of interpretation that include the invisible or barely visible. In the same way peripheral vision and the ability to detect movement, danger or opportunity at the edges of one’s visual field increases the chances of survival, so the ability to imaginatively take on other perspectives is essential to peripheral visiting. In the Karrabing Collective’s works, this involves interpreting the views and desires of land and ancestors: ‘Country gets jealous like people. Ancestors too. You don’t sweeten them up, visit, you know, and they get jealous and punish you.’Footnote39 The epistemological frame of modernity/coloniality attempts to visualise everything in terms of divine or economic calculations. From this perspective images are connected to reality in the same way a contract attempts to sum up all the possibilities of a relation. But practices of visiting teach us that not all aspects of a relation or reality can be seen from a single point of view. As Gustavo Esteva and Madhu Suri Prakash observe,

The margins alone can teach others what they are doing to regenerate their places beyond the reign of economics, reinventing ancient traditions of hospitality… It is very difficult if not impossible for individual selves to be hospitable. Traditions of hospitality are kept alive only by those who enjoy and participate in communal memory.Footnote40

Hospitality is thus connected to shared memory, to a sense of place that is embodied and visualised by intersecting perspectives and which can only be told as a story that moves fluidly between past, present and future. As already mentioned, many fences, road signs and paths spring up in the Karrabing Collective’s works, and it is not immediately clear on which side we are expected to be positioned as spectators. As can be the case when visiting, rules and signs we may have believed were clear no longer mean what we thought. People jump over fences; boats glide across invisible barriers; tides run in and out; landmarks connect histories. The abstract treaties, regulations and territories invented by settlers lose their purchase in this lived space. In a state of disorientation, we might fall back on instinctive and unfocused modes of vision. Not recognising all the aspects of the stories told in the films, non-Indigenous viewers may feel the need to abandon modernity/coloniality’s standards of quality, authenticity and reality, to go instead at least part of the way into an environment that is turned away from us. Rather than being given an image to consume, we apprehend some of the risk that comes with visiting. We might begin to reactivate a kind of vision that senses movement, danger or the opportunity for transformation at the edge of our habitual perimeters of experience. In the absence of familiar progressions from landmarks to abstraction, we find ourselves attempting to navigate a wider, more pluralised space of familiarity based on peripheral kinship. We might forget to establish ourselves as authorities and experts, and ‘re-member’ ourselves as guests.Footnote41

In these new surroundings, roles can be reversed and the relationship between subject and object reshuffled. As we have seen, the separation of subject and object is a key element of the aesthetics of modernity/coloniality. Representations based on the Doctrine of Discovery objectified lands and people as territories and populations to be managed and exploited by Christian subjects. The wound of the colonial encounter is, among other things, a wound of abused hospitality and an erasure of the communal subject relations that sustain life in familiar and unfamiliar places. Rather than a ‘subject- and object-making dance’, then, I would characterise peripheral visiting as an embodied meditation on what it means to host and be hosted. People can be held and hosted by more-than-human environments, and the peripheries of vision do not merely contain objects and subjects waiting to be identified. Instead, our vision is informed by shifting edges, making us both subject and object, host and guest.

The aesthetics of modernity/coloniality renders images as abstract vessels of information, which are seemingly objective and accessible through Western hosting institutions. However, these museums, archives and collections of images can be compared to Esteva and Prakash’s description of institutions such as shelters, asylums, hospitals and hospices, as

rooted in the long tradition of intolerance masked as the ‘ideal’ of ‘tolerance’ that defines modern hospitality. This hospitality is shaped by the same mindset that breaks commons and communities, replacing them with the lonely privacy and competitive public corporations of ‘homeless’ minds; individual selves doomed to the futile search for home.Footnote42

Reflecting on my first experiences of watching the Karrabing Collective’s films, the sense of disorientation I felt was related to this reciprocal ethics of hospitality and visiting. In viewing these works, I was taking up the challenge of visiting, of becoming familiar with a place and a community, without relying on a transactional relationship of exchange. This involved travelling through the images without prior ownership of the narrative’s navigational tools and images. In a state of disorientation, it is not so easy to take a distanced view of things. Without recourse to the comparative aesthetic categories of quality and authenticity, I understood that the Karrabing Collective’s videos feel like lived spaces precisely because of the viewer’s disorientation. While the members of the Collective revisit their relationship to the land, to their ancestors, to the past and to the future through their video works, non-Indigenous viewers are invited to revisit themselves in relation to the communal and its absence. This experience led me to acknowledge my own and others’ colonial wounds of homelessness, as well as the places where homelessness might intersect with possibilities for hospitality, if approached with humility. Tolerance is pretending not to see where the other’s perspective intersects with your space, where it affects your space, and where you affect theirs. In the living archives of peripheral visiting we lose the overview of the map, which attempts to transfer everything into an object of sight.

Thinking back to the Q&A with the Karrabing Collective at Tate Modern in 2017, what I sensed was the kind of familiarity and belonging that can travel, a sense of being comfortable with being hosted in a space, not based on authority but on an interest in dialogue. Through their practice of travelling vision, the Collective’s embodied kinship seems to have become an extension of lived space. Their common language comes from being able to both negotiate a plurality of perspectives and navigate multiple levels of space. What we can learn from their mode of vision is that where the modern archive of representations is an abstract space connected to the search for limited origins, as visitors of a living archive we need to find a way to sense the next step in an ongoing story. The activation of peripheral vision can make us aware of the way our sensorium is extended by our environment in a way that is relational rather than extractive. We are invited to feel out from the edges of ourselves, to become part of the storytelling of survivance by acknowledging the wounds of abused hospitality. From a position of owing rather than owning, becoming part of the story of the land does not mean laying claim to it or being able to take over its representation. The space of the Collective’s work is a living archive of possible perspectives.

Conclusion

The Karrabing Collective’s practice is an important example of the ways in which modes of vision and image-making can play a part in the healing of colonial wounds, specifically those related to the destruction of Indigenous life-worlds and relationships to land. This healing practice of image-making is radically different from the representational incorporation of colonised peoples, objects and environments into the modern view of the world. It involves a delinking from the aesthetics of modernity/coloniality, which colonises the senses and erases other modes of being in the world. I see the video works of the Collective as a movement away from the dominance of central vision, with its logics of extraction and access. Central vision can be linked to the ethnographic documentary tradition of registering and repeating the moment of the colonial encounter between coloniser and colonised. By representing this moment as defined by discovery, images of colonised lands and peoples become reduced to the logic of exchange and preservation. The image of the colonial encounter is used as evidence of the settler-colonist’s right to extract and exploit the land; it is contained and enshrined as part of the colonial archive. In this way, the logic of modernity/coloniality perpetuates the abused hospitality of violent colonial appropriation. Land becomes territorialised as an abstract space defined by ownership rather than relation.

The Collective’s films offer more pluralising invitations to what I call peripheral visiting. Delinking from the signs and borders that determine modernity/coloniality’s limited representation mapping of space, their works are embedded in collaborative, travelling and interpretative modes of relating to the world. Decolonial theory often places an emphasis on practices of listening, so as to shift from the logic of owning to the logic of owing. I argue that the Collective’s practices of image-making and seeing also connect to the experience of owing to the land, by drawing on the position of the visitor in lived space. Their films are connected to a need to travel to places connected to their ancestors and to Dreamings, to keep these alive. The stories to which they relate in these places cannot be extracted, fixed to a particular moment in time, archived as a closed event; they are connected to the living voices of ancestors, Dreamings and the land. This archive is seen through the travelling vision of members of different generations and families, who point out, question and interpret traces and signs in the land. The intersection of these different perspectives through movement leads to dialogue and an ongoing storytelling that connects present, past and future.

Although they are shown around the world, the works of the Karrabing Collective create their own context and lived space through a way of seeing and showing that is an extension of their relational movement through and with the land. They are not an expansion of modernity/coloniality’s archive of the ‘peoples of the world’. The reality, authenticity and quality of the images are not determined by the judgment of an external expert or authority. Instead, Elizabeth Povinelli’s membership in the Collective entails a refusal to look for legitimacy or representation outside the Collective’s locally embedded practice. Her involvement addresses the complex transcultural dimensions of settler-colonial past and present, and commits to a process of hospitality that builds on communal memory and responsibility. This hospitality includes space both for those who can see the ancestors and Dreamings of Indigenous kinship, and those who cannot. This does not translate into easy access for the non-Indigenous viewer. It acknowledges the agency of the land and of present, past and future inhabitants to turn towards or away from the viewer as visitor. To extend and revive the hospitality that can heal colonial wounds, the viewer must unlearn the territorialising habits of central vision and allow for the experience of disorientation that comes with visiting a place that is not familiar in the sense of ownership. Through peripheral vision, the viewer is invited to turn towards the traces of movement and embodied memories at the edges of their habitual field of vision. This involves retuning one’s senses to imagine the host’s interests and their own relationality with the living archive of images. This way of seeing images acknowledges the ongoing support of the human and non-human environment towards the intersection of perspectives.

Notes

1 Natasha Lewis Bigfoot, quoted in Karrabing Film Collective, ‘Growing up Karrabing: A Conversation with Gavin Bianamu, Sheree Bianamu, Natasha Lewis Bigfoot, Ethan Jorrock and Elizabeth Povinelli’, un Magazine, vol 11, no 2, 2017

2 In Interview with Karrabing Film Collective (Mik Gaspay, 2018), members explain that ancestral spirits (nyudj) are called ‘totems’ by some but are referred to as ‘Dreamings’ by their group. Kadist online, https://kadist.org/program/karrabing-film-collective-2/.

3 The Karrabing Film Collective use the term ‘Indigenous’ to refer to most of their members, rather than ‘Aboriginal’, ‘First Nations’ or ‘First Peoples’, and so I also use this term.

4 Thanks to Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield, who curated this meaningful screening event.

5 Jeremy Elphick, ‘Low Tide Turning – An Interview with the Karrabing Collective’, 4:3 Online, 5 August 2015, https://fourthreefilm.com/2015/08/low-tide-turning-an-interview-with-the-karrabing-film-collective/

6 The term ‘social majorities’ comes from Esteva and Prakash, who distinguish between ‘social minorities’ as ‘groups in both the North and the South that share homogeneous ways of modern (Western) life’ and ‘social majorities’ who ‘have no regular access to most of the goods and services defining the average ‘standard of living’ in the industrial countries. Their definitions of a ‘a good life’, shaped by their local traditions, reflect their capacities to flourish outside the ‘help’ offered by ‘global forces’. Gustavo Esteva and Madhu Suri Prakash, Grassroots Post-Modernism: Remaking the Soil of Cultures, Zed Books, London, 2014, p 16.

7 Walter D Mignolo and Rolando Vázquez, ‘Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings’, Social Text, 15 July 2013, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/

8 Mignolo and Vázquez build on the work of Quijano, who coined the term ‘colonial power matrix’ to describe the coloniality of power that constitutes the modern/colonial world through racialised social classifications and exploitation. Aníbal Quijano, ‘Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America’, Nepantla: Views from South, vol 1, no 3, 2000, pp 533–580. The idea that modern civilisation is inseparable from colonial violence and thought is of course also present in the work of many other postcolonial, decolonial and Indigenous thinkers. See eg Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism [1950], Joan Pinkham, trans, Monthly Review Press, New York, 2000.

9 Mignolo and Vázquez, ‘Decolonial AestheSis’, op cit

10 Ibid

11 Mignolo and Vázquez’s emphasis on plurality draws on the work of Escobar in articulating a ‘pluriversal politics’, which affirms the coexistence of many possible worlds while resisting the extractivist model of the destruction of worlds for the progress of one singular (Western, capitalist) world. Arturo Escobar, Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2020.

12 Mignolo and Vázquez, ‘Decolonial AestheSis’, op cit

13 Karrabing Film Collective, ‘Medium Earth’, online exhibition curated by Ruby Arrowsmith-Todd for Together in Art, The Art Gallery of New South Wales, October 2020, https://togetherinart.org/karrabing-in-medium-earth/

14 In my current AHRC-funded doctoral research at Kingston University, on peripheral vision and co-authorship in transcultural moving image works, I am elaborating on the decolonial aesthesis of image-making.

15 Mignolo and Vázquez, ‘Decolonial AestheSis’, op cit

16 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, Continuum, London, 2004

17 David MacDougall, ‘The Visual in Anthropology’, in Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy, eds, Rethinking Visual Anthropology, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 1997, pp 276–295

18 The Doctrine of Discovery was based on Pope Alexander VI’s 1493 decree that any land not inhabited by Christians was available to be discovered, claimed and exploited by Christian rulers. ‘Inter Caetera’ Demarcation Bull, 4 May 1493, Gilder Lehrman Collection.

19 Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, Verso, New York, 2019, p 94

20 According to Lefebvre, lived space exists within perceived space and conceived space, as the lived uses of a space can be limited and predetermined by (modern) society’s normative perceptions and conceptions. Lefebvre’s description of the ‘abstract space’ produced by capitalist and neocapitalist societies overlaps with the logic of modernity/coloniality in its substitution of exchange value for use value. Abstract space is shaped by homogenisation, repetitiveness, interchangeability and totalising centrality: ‘a centrality of this order expels all peripheral elements with a violence that is inherent in space itself’. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, Donald Nicholson-Smith, trans, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1991, pp 332, 382.

21 The initiative and resources for participatory documentaries and Indigenous media projects often come from Western-based filmmakers or NGOs, and the history of these projects is entangled with that of neocolonial ‘aid’ in complex ways. The image-making practices often require a reclaiming of the technologies, structures and aesthetics of the moving image before they can become sustainable elements of local community practice.

22 Mignolo and Vázquez, ‘Decolonial AestheSis’, op cit

23 Jean Rouch, ‘The Camera and Man’, Studies in Visual Communication, vol 1, no 1, 1974, pp 37–44, p 41, https://repository.upenn.edu/entities/publication/37f8e212-8631-4e00-a045-10b926a6accb. While Rouch advocates for the ciné-eye as a ritual, subjective participant rather than a mechanical observer in the act of filming, it can still be argued that his films are structured as an exchange and are aimed at a final product for mainly Western, Eurocentric consumption.

24 Trinh T Minh-ha, When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics, Routledge, New York and London, 1991, p 35

25 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Eric Prenowitz, trans, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1998, p 91

26 Ibid, p 1

27 Karrabing Film Collective, ‘Growing up Karrabing’ op cit

28 Karrabing Film Collective, Medium Earth, op cit

29 Ibid

30 Transcript of video interview conducted by and with the Karrabing Film Collective, February 2021, The National 4: New Australian Art Now, 2021, https://www.the-national.com.au/artists/karrabing-film-collective/day-in-the-life-/

31 Karrabing Film Collective, ‘Growing up Karrabing’, op cit

32 Derrida, Archive Fever, op cit, p 17

33 Azoulay, Potential History, op cit, pp 182–183

34 Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1999, p vii

35 Karrabing Film Collective, Medium Earth, op cit

36 Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland, 2018

37 Donna J Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2016, pp 126–127

38 Hannah Arendt, Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1989, pp 42–43

39 Karrabing Film Collective, ‘We burn grass when it’s properly dry – but what are we gonna do when the whole world fried?’, Versopolis, 6 February 2020, https://www.versopolis.com/author/343/the-karrabing-film-collective

40 Esteva and Prakash, Grassroots Postmodernism, op cit, pp 86–87

41 ‘The remembering that is a part of the “memory” of a village story-teller, telling thousands of times the same story, each and every time with a difference, is critical for the re-membering without which there can be no community.’ Esteva and Prakash, Grassroots Postmodernism, op cit, p 72

42 Esteva and Prakash, Grassroots Postmodernism, op cit, p 89