Abstract

Background

The impact of psoriasis in special areas (i.e., scalp, nails, palms, soles, genitals) on patient physical functioning, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and work abilities has not been fully characterized. We assessed associations between disease severity and special area involvement in psoriasis symptoms, HRQoL, and work/activity impairment.

Methods

Patients with psoriasis from the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry who initiated systemic treatment between 04/2015–06/2020 were included. Outcomes were change from baseline in psoriasis symptoms, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and work/activity impairment at 6 months stratified by baseline disease severity and special area involvement.

Results

Among 2620 patients, increasing disease severity was associated with worsening patient-reported outcomes. Patients with (46.0%; N = 1205) versus without (54.0%; N = 1415) psoriasis in special areas reported greater HRQoL and work/activity impairment. Over 6 months, patients with unchanged or worsening disease severity had reduced HRQoL and increased symptom severity; incremental increases in patient HRQoL and decreases in symptom severity were associated with improved disease severity.

Conclusions

Higher disease severity and special area involvement was associated with worse outcomes and impaired work abilities. These data highlight the significant impact that adequate treatment of severe psoriasis and/or special area involvement may have on patient HRQoL and function.

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated disease characterized by inflammation and painful skin lesions that is estimated to affect up to 3% of the US population, of which approximately 18% have moderate to severe disease (Citation1–3). Treatment targets include decreasing the body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis, which can greatly improve patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and work abilities (Citation4–7).

Psoriasis on the scalp, nails, palmoplantar region, and genitals, often deemed ‘difficult-to-treat’ and referred to involvement of ‘special areas’ herein, is often recalcitrant to treatment and associated with significantly reduced HRQoL (Citation8). While not all patients with psoriasis consistently have lesions in these areas, up to 90% will experience lesions in one of these areas at least once during their lifetime (Citation4,Citation6,Citation7). Treatment guidelines for psoriasis in special areas recommend that systemic therapies be considered, especially if topical therapies have been ineffective (Citation8).

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are crucial to understanding how patients view their disease and its impact on their daily lives. Further, PROs can be used to assess patient-perceived effectiveness, which is a driving factor in medication persistence (Citation9). Given significant impact on HRQoL and difficulty of adequately treating the disease, psoriasis in special areas may be considered more severe, even if based on the extent of BSA affected, standard disease measures would typically classify it as mild disease (Citation5,Citation6). Thus, while BSA may be a good marker for disease activity, it alone does not capture the impact of psoriasis on HRQoL.

Improvements in BSA have been associated with significantly improved HRQoL (Citation10,Citation11). Moreover, these data demonstrated that patients can perceive a meaningful difference between clear and almost clear skin, and that with current therapeutic options, clear skin is a realistic treatment target (Citation11). However, these studies did not include patients with psoriasis in special areas, thus its impact on disease severity and PROs has not been characterized. Therefore, this study sought to examine associations between disease severity and PROs among patients with plaque psoriasis, including the impact of special area involvement.

Materials and methods

Database, study design and participants

Data on adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with psoriasis by a dermatologist were collected by the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry, a prospective, multicenter, non-interventional registry that collects data on adult patients with psoriasis. Baseline and longitudinal follow-up data was collected from both patients and their treating dermatologists during routine clinical encounters using Registry questionnaires, which collect data on patient socio-demographics, health characteristics and behaviors, psoriasis treatment history, disease severity, and physician- and patient-reported outcomes. Blood collection and other diagnostic tests are not required for participation; however, relevant standard of care laboratory and imaging results are reported when available. The CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry was launched in April 2015, and as of July 31, 2023, had enrolled 19,276 subjects with psoriasis from 267 private and academic clinical sites, with 630 physicians throughout 48 states and provinces in the US and Canada. This study leveraged de-identified registry data, and no identified information was used; thus, ethics committee approval was not required.

Patients included in the study were diagnosed with plaque psoriasis, initiated a biologic or non-biologic therapeutic agent on the day of a registry visit between April 2015 and August 2020, and had 6-month (5–9 months) follow-up data available. Eligible medications included tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (i.e., adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, infliximab), interleukin 12/23 inhibitors (i.e., ustekinumab), interleukin 23 inhibitors (i.e., guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab), interleukin 17 inhibitors (i.e., secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab) and non-biologic systemic therapies (i.e., methotrexate, cyclosporine, apremilast).

Impact of disease severity and involvement of special areas of interest at baseline on PROs

Psoriasis disease severity at baseline was assessed by BSA involvement (mild: <3% BSA, moderate: 3-10% BSA, or severe: >10% BSA). The presence of psoriasis in special areas, defined as psoriasis on scalp, nails, palms, soles, and/or genitals, was also assessed within the mild, moderate, and severe disease categories.

Change from baseline to 6 months PROs by level of skin clearance

Patients were categorized based on the level of skin clearance achieved from baseline to 6-month follow-up. Cohorts included those that had no change or worsening in % BSA (i.e. ≤0%) or that showed improvement in % BSA from baseline (i.e., 1%–49%, 50%–74%, 75%–89%, or 90%–100%).

Sensitivity analyses using PASI-defined disease severity

Sensitivity analyses for the impact of disease severity and presence of psoriasis in special areas at baseline on PROs and the change from baseline to 6 months in PROs by level of skin clearance were also evaluated using patients’ PASI scores at baseline and 6 months. Patients were stratified based on PASI-defined disease severity (mild: <5, moderate: 5–12, or severe: >12) instead of BSA.

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient-reported outcomes assessed at baseline and 6 months included the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), psoriasis symptoms (patient-reported itch, fatigue, and skin pain), and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) scores.

The DLQI has a total score range of 0–30, with higher scores indicating poorer HRQoL (Citation12). For this study, HRQoL impairment was defined as DLQI ≥2.

Psoriasis symptoms (skin pain, fatigue, and itch/pruritis) were assessed on 100-point visual analog scales (VAS) (Citation13). Patients scored each symptom from 0 (no pain/fatigue/itching) to 100 (worst pain/fatigue/itch imaginable).

The WPAI questionnaire was used to assess work and activity impairment. The WPAI consists of four domains (i.e., presenteeism, absenteeism, work impairment, and activity impairment), each scored as percent impairment (0–100%), with higher scores indicating greater impairment (Citation14). Presenteeism, absenteeism, and work impairment were measured only among patients reporting employment at baseline.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics were summarized for the overall cohort, as well as stratified by disease severity. Differences in PRO measures and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported between those with and without a history of psoriasis in special areas for each disease severity level. The mean change with standard deviations in each PRO from baseline to 6–months follow-up was reported separately and stratified by percent change in BSA. Tests for trends among mean changes in PROs by BSA or PASI response at 6 months were determined by a fixed-effects logistic regression model based on five-levels of change ((Citation1) <50%, including those who did not improve (Citation2); 50–74% (Citation3); 75–89% (Citation4); 90–99%; and (Citation5) 100%).

Results

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 2620 patients with psoriasis met inclusion criteria for this study (). Most patients had moderate or severe disease (47.0%, N = 1231 and 39.7%, N = 1039, respectively) as measured by percent BSA% involvement.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by BSA-measured disease severity.

More than half of patients included in this study (54.0%, N = 1415) did not have a history of psoriasis in any of the special areas of interest (i.e., hands, feet, scalp, nails, or genitals). Of the 46.0% of patients that did have a history of psoriasis in special areas: 38.9% (N = 1019), 15.7% (N = 412), 10.6% (N = 278), and 8.9% (N = 179) had scalp, nail, palmoplantar, and genital psoriasis, respectively.

At baseline, most patients (N = 2268; 86.9%) reported HRQoL impairment (i.e. DLQI ≥2). Based on 100-mm VAS assessments, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for patient-reported itch, fatigue, and skin pain was 51.8 ± 33.2, 37.4 ± 29.6, and 34.3 ± 32.1, respectively. The mean percent work impairment was 17.8 ± 24.3 with a mean percent activity impairment of 23.9 ± 27.6.

Overall, patient characteristics were generally similar regardless of disease severity () or involvement of psoriasis in special areas ().

Table 2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by BSA-measured psoriasis disease severity and involvement of special areas.

Disease severity and involvement of special areas at baseline on PROs

When stratified by disease severity (% BSA), HRQoL impairment increased with worsening disease severity (). Similar trends were reported for psoriasis symptoms (i.e., itch, fatigue, and skin pain) and work and activity impairment.

Patients with psoriasis in special areas reported greater HRQoL impairment, as evidenced by higher total DLQI scores, more troublesome symptoms, and greater work and activity impairment compared with patients who reported the same level of disease severity but without psoriasis in special areas ().

Change from baseline to 6 months in HRQoL and psoriasis symptoms by BSA response

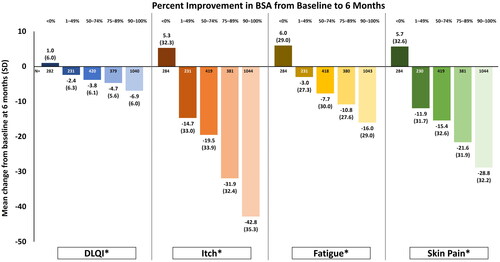

An increase in mean DLQI scores was observed in patients with worsening or no improvement in BSA (i.e., <0% change from baseline) at 6 months after systemic therapy initiation (). Improvement in HRQoL was demonstrated by increasing levels of BSA response such that patients with a 1–49% improvement in BSA had a mean (±SD) 2.4 ± 6.3-point reduction in DLQI, whereas those with a 90–100% improvement had a mean 6.9 ± 6.0-point reduction. Similar trends were also demonstrated with patient-reported itch, fatigue, and skin pain. Patients with no change or worsening in disease severity reported worse symptom severity.

Figure 1. Mean change from baseline in HRQoL and psoriasis symptoms among all patients (N = 2620) by percent improvement in BSA at 6-month follow-up.Change in BSA <0% refers to patients who had either no change or an increase in percent BSA from baseline. *p < 0.001 for trend among response groups. BSA: body surface area; DLQI: dermatology life quality index; PsO: psoriasis; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; SD: standard deviation.

Change from baseline to 6 months in work and activity impairment by BSA response

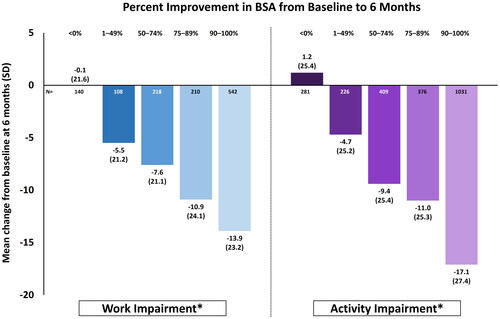

A trend toward decreasing work impairment with increasing BSA improvement was found (). Patients achieving 1-49% improvement in BSA had a corresponding mean (±SD) 5.5 ± 21.2-point reduction in work impairment. This increased to a mean 13.9 ± 23.2-point reduction in work impairment for patients with 90-100% improvement in BSA. Similarly, patients reported a mean 4.7 ± 25.2-point and mean 17.1 ± 27.4-point reduction in activity impairment when BSA improved by 1-49% and 90-100%, respectively.

Figure 2. Mean change from baseline in work and activity impairment among all patients (N = 2620) by BSA response at 6-month follow-up. Change in BSA <0% refers to patients who had either no change or an increase in percent BSA. *p < 0.001 for trend among response groups. Work impairment was measured only among those actively employed at baseline (N = 1764). BSA, body surface area; SD, standard deviation.

Results from sensitivity analyses, wherein disease severity was defined by PASI, were generally consistent (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Figures 1–2).

Discussion

This analysis of adult patients with psoriasis who initiated a new systemic therapy from the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry showed that, at baseline, increasing disease severity, as well as involvement of special areas, were associated with worse HRQoL, more severe psoriasis symptoms, and greater work and activity impairment. The magnitude of HRQoL and psoriasis symptom improvements 6 months after systemic therapy initiation were positively associated with improvements in disease activity, as measured by changes in BSA or PASI. Indeed, this study demonstrated minimally clinical important differences (>4-point improvement) in DLQI scores among patients with 75–89% and 90–100% improvement in BSA at 4.7 and 6.9 points, respectively (Citation15).

The presence of psoriasis in special areas can have a profound effect on HRQoL and the ability to participate in work or leisure activities. Patients most frequently reported feelings of shame, embarrassment, self-consciousness, and stigmatization that negatively affected their daily lives (Citation16,Citation17). Recently published guidelines from the International Psoriasis Council (IPC) specifically recommend the use of systemic therapies in patients with psoriasis in special areas, even for those with otherwise mild disease (Citation8). The IPC guidelines also highlight that BSA and PASI measures do not adequately capture the impact of psoriasis in special areas, in either disease severity or HRQoL measurements, and therefore should not be exclusively relied on (Citation8).

While our findings that HRQoL among patients with psoriasis improved with improving BSA are in line with previous reports (Citation10,Citation11), few studies have assessed how involvement of special areas as a function of disease severity impacts HRQoL (Citation1,Citation5,Citation18). This study showed that patients with involvement of psoriasis in special areas, despite having similar BSA and PASI disease severity scores, reported consistently greater HRQoL impairment and symptom severity compared with patients without special area involvement. These results were most profound among patients with mild disease activity as measured by BSA. This is further real-world evidence to support the IPC recommendations for treatment of patients with mild skin involvement who also have psoriasis in special areas. Using Pearson correlation analyses, other studies have shown that improvement of psoriasis in special areas was associated with improved HRQoL. Indeed, a positive relationship between disease severity measures (PASI and the Nail Psoriasis Area Severity Index) and HRQoL improvement (DLQI) was shown in patients with psoriasis in special areas (Citation5) or nail psoriasis (Citation18) receiving systemic therapy (Citation18).

This study also demonstrated marked improvement in work and leisure activity in patients as the level of skin clearance improved. Similar to previous studies, both disease and symptom severity, as well as presence of psoriasis in special areas, were found to negatively affect work productivity and the ability to perform daily activities (Citation19–21). Patients reported that they were more likely to miss work or be less productive whenever symptom severity, especially itching or scaling, worsened (Citation20). A study using real-world data demonstrated that mean annual indirect costs due to work productivity loss amounted to $3,742-$9,591 per patient with psoriasis (Citation22).

Despite the variety of treatment options available, some patients may be hesitant to receive care due to fear or stigma (Citation7). It is important that healthcare professionals approach patients with psoriasis in special areas with compassion and convey the goals and beneficial outcomes of treatment (Citation7). The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) states that an acceptable response to treatment at 3 months for patients with psoriasis is either BSA ≤3% or a 75% improvement in BSA; the treatment target is BSA ≤1% maintained at every 6-month evaluation (Citation23). As shown in this study, improvement in disease severity was coupled with improvement in patients’ HRQoL and work abilities. Indeed, patients achieving ≥75% improvement in BSA, the NPF acceptable change, had marked improvement in HRQoL, psoriasis symptoms, and work and activity impairment, and these improvements only increased as skin clearance exceeded 90%.

A strength of this study is that the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry is a longitudinal prospective registry that collects data that are not available in claims databases, such as disease activity scores and PROs. Limitations of the study are that the registry includes a sample of adults with psoriasis that may not be representative of all adults with psoriasis in North America. While overall improvements in patient-reported outcomes and impairment were assessed, this study could not assess improvement of psoriasis in special areas.

Conclusions

In this real-world study, HRQoL, burden of psoriasis symptoms, and impairment worsened as disease severity at baseline increased. In addition, patients with psoriasis with a history of special area involvement reported worse HRQoL, psoriasis symptoms, and impairment than those without a history of psoriasis with involvement of special areas with the same disease severity. Upon initiating a new biologic or non-biologic therapy, greater improvements in PROs were reported in patients as the level of skin clearance increased, as measured by BSA or PASI.

Ethical approval

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice (GPP). All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting noninterventional research involving human subjects with a limited dataset. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central Institutional Review Board (IRB), the New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB; no. 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive authorization to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from their respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to CorEvitas, LLC before the site’s participation and initiation of any study procedures. All patients in the registry were required to provide written informed consent and authorization before participating.

Authors contributions

All authors substantially contributed to study conception and design, interpretation of data, and drafting and critically revising for intellectual content. AS and JJ contributed to acquisition of data; AS, JJ, MP, HP, and VG contributed to interpretation of data.

Author disclosures

B Strober has served as a consultant (received honoraria) for AbbVie, Alamar, Alumis, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aristea, Asana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Immunic Therapeutics, Kangpu Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Dermavant, Evelo Biosciences, Janssen, Leo, Eli Lilly, Maruho, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera Health, Protagonist, Nimbus, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, Sun Pharma, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, Union Therapeutics, Ventyxbio, and vTv Therapeutics; has stock options for Connect Biopharma and Mindera Health; has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Arcutis, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme; is a co-scientific director (consulting fee) for CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry; and as an investigator for CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry and serves as an Editor-in-Chief (honorarium) for the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

K Callis Duffin is an investigator for, has received research grants from, and served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Stiefel, and Xenoport.

M Lebwohl is an employee of Mount Sinai and receives research funds from: AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis, Avotres, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cara therapeutics, Dermavant Sciences, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, and UCB, Inc., and is a consultant for Aditum Bio, Almirall, AltruBio Inc., AnaptysBio, Arcutis, Inc., Aristea Therapeutics, Avotres Therapeutics, Brickell Biotech, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Celltrion, CorEvitas, Dermavant Sciences, Dr. Reddy, EPI, Evommune, Inc., Facilitation of International Dermatology Education, Forte Biosciences, Foundation for Research and Education in Dermatology, Galderma, Helsinn, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Pfizer, Seanergy, Strata, Trevi, and Verrica.

A Sima and J Janak are employees of CorEvitas, LLC (formerly Corrona, LLC). CorEvitas is supported through contracted subscriptions with multiple pharmaceutical companies. The manuscript was a collaborative effort between CorEvitas and AbbVie with financial support provided by AbbVie.

M Patel, H Photowala, and V Garg are employees of AbbVie Inc., and may hold stock or stock options.

J Bagel has received research funds payable to Psoriasis Treatment Center from AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, CorEvitas LLC, Dermavant Sciences, Dermira, Eli Lilly and Company, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Janssen Biotech, Kadmon Corporation, LEO Pharma, Lycera Corp, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma, Taro Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, and UCB; consultant fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene Corporation, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Biotech, Novartis, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and UCB; and speakers fees from AbbVie, Celgene Corporation, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biotech, and Novartis.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the investigators, their clinical staff, and patients who participate in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry. The CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry was developed in collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF). Medical writing services provided were by Samantha Francis Stuart, PhD, of Fishawack Facilitate Ltd, part of Fishawack Health, and funded by AbbVie. Editorial support was provided by Alicia Beeghly, MPH, PhD, of CorEvitas, LLC. The authors would like to thank Tin-Chi Lin for assistance with the statistical analysis and contributions to the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry and this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Merola JF, Qureshi A, Husni ME. Underdiagnosed and undertreated psoriasis: nuances of treating psoriasis affecting the scalp, face, intertriginous areas, genitals, hands, feet, and nails. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(3):1. doi: 10.1111/dth.12589

- Egeberg A, See K, Garrelts A, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis in hard-to-treat body locations: data from the Danish skin cohort. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12895-020-00099-7.

- Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003–2006 and 2009–2010 national health and nutrition examination surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(1):37–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.012.

- Kivelevitch D, Frieder J, Watson I, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches for treating psoriasis in difficult-to-treat areas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(6):561–575. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1448788.

- Lanna C, Galluzzi C, Zangrilli A, et al. Psoriasis in difficult to treat areas: treatment role in improving health-related quality of life and perception of the disease stigma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(1):531–534. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1770175.

- Lanna C, Zangrilli A, Bavetta M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in difficult-to-treat psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13374. doi: 10.1111/dth.13374.

- Aldredge LM, Higham RC. Manifestations and management of difficult-to-treat psoriasis. J Dermatol Nurses’ Assoc. 2018;10(4):189–197. doi: 10.1097/JDN.0000000000000418.

- Strober B, Ryan C, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Recategorization of psoriasis severity: delphi consensus from the international psoriasis council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.026.

- Volpicelli Leonard K, Robertson C, Bhowmick A, et al. Perceived treatment satisfaction and effectiveness facilitators among patients with chronic health conditions: a self-reported survey. Interact J Med Res. 2020;9(1):e13029. doi: 10.2196/13029.

- Wu JJ, Schrader A, McLean RR, et al. Improvement in body surface area is associated with better quality of life among patients with psoriasis in the corrona psoriasis registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(6):1715–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.039.

- Korman NJ, Malatestinic W, Goldblum OM, et al. Assessment of the benefit of achieving complete versus almost complete skin clearance in psoriasis: a patient’s perspective. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(2):733–739. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1772454.

- Jorge MFS, Sousa TD, Pollo CF, et al. Dimensionality and psychometric analysis of DLQI in a Brazilian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01523-9.

- Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, et al. It’s good to feel better but it’s better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1720–1727. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110392.

- Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, et al. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire–general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):R177. doi: 10.1186/ar3141.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33. doi: 10.1159/000365390.

- Sampogna F, Linder D, Piaserico S, et al. Quality of life assessment of patients with scalp dermatitis using the Italian version of the scalpdex. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(4):411–414. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1731.

- Hawro M, Maurer M, Weller K, et al. Lesions on the back of hands and female gender predispose to stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(4):648–654 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.040.

- Prevezas C, Katoulis AC, Papadavid E, et al. Short-term correlation of the psoriasis area severity index, the nail psoriasis area severity index, and the dermatology life quality index, before and after treatment, in patients with skin and nail psoriasis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5(6):344–349. doi: 10.1159/000499348.

- Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, et al. Association of patient-reported psoriasis severity with income and employment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.023.

- Lewis-Beck C, Abouzaid S, Xie L, et al. Analysis of the relationship between psoriasis symptom severity and quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis using structural equation modeling. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:199–205. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S39887.

- Hayashi M, Saeki H, Ito T, et al. Impact of disease severity on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;72(2):188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.06.003.

- Villacorta R, Teeple A, Lee S, et al. A multinational assessment of work-related productivity loss and indirect costs from a survey of patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(3):548–558. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18798.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.017.