Abstract

Background:

Methotrexate is an off-label therapy for atopic dermatitis. A lack of consensus on dosing regimens poses a risk of underdosing and ineffective treatment or overdosing and increased risk of side effects. This systematic review summarizes the available evidence on dosing regimens.

Materials and methods:

A literature search was conducted, screening all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and guidelines published up to 6 July 2023, in the MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases.

Results:

Five RCTs and 21 guidelines were included. RCTs compared methotrexate with other treatments rather than different methotrexate dosing regimens. The start and maintenance doses in RCTs varied between 7.5–15 mg/week and 14.5–25 mg/week, respectively. Despite varied dosing, all RCTs demonstrated efficacy in improving atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms. Guidelines exhibited substantial heterogeneity but predominantly proposed starting doses of 5–15 mg/week for adults and 10–15 mg/m2/week for children. Maintenance doses suggested were 7.5–25 mg/week for adults and 0.2–0.7 mg/kg/week for children. One guideline suggested a test dose and nearly half advised folic acid supplementation.

Conclusion:

This systematic review highlights the lack of methotrexate dosing guidelines for atopic dermatitis. It identifies commonly recommended and utilized dosing regimens, serving as a valuable resource for clinicians prescribing methotrexate off-label and providing input for an upcoming consensus study.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic, and inflammatory skin disorder. Systemic treatment becomes necessary in moderate-to-severe cases where topical medications and phototherapy fail or are contraindicated. This affects a small percentage of pediatric (less than 0.5%) (Citation1) and adult (1–10%) AD patients (Citation2–4). Methotrexate (MTX), prescribed off-label, is one of the widely employed systemic treatment options for AD. However, despite its broad usage (Citation5–19) a consensus on MTX dosing for AD is lacking.

MTX is known for its inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase and DNA synthesis, as well as its immune-modifying effects (Citation20). Due to this latter characteristic, MTX has become essential in the treatment of various rheumatologic (Citation21) and dermatological conditions. While officially approved for psoriasis and mycosis fungoides (Citation22), it is frequently used off-label for other cutaneous diseases, including AD (Citation5,Citation6,Citation19,Citation23–25).

Among the systemic treatment choices available for AD, MTX is classified as a conventional therapy, contrasting the newer biologics and small molecules. Regulatory norms in many regions necessitate dermatologists to initiate with a conventional systemic therapy, only transitioning to biologics or small molecules in cases of ineffectiveness or contraindications. Research has shown that MTX is prescribed widely as a first-line treatment (Citation26,Citation27) and that it is the most commonly used second-line treatment in the Netherlands (Citation27) and the UK (Citation28). This can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, its long history of use across various medical conditions has provided a significant depth of experience. Secondly, its affordability makes it accessible worldwide, also in regions where cost is a barrier to obtaining other medications. Lastly, its effectiveness. Although on-label cyclosporine is commonly considered the initial conventional therapy choice for AD due to the substantial evidence supporting its efficacy (Citation8,Citation10), findings from two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that MTX demonstrates comparable efficacy to cyclosporine, with potentially lower incidence of treatment-related adverse events (Citation29,Citation30). Another study also shows significantly prolonged drug survival and post-drug survival for MTX in comparison to cyclosporine (Citation31). MTX, however, does come with a risk of severe side effects, including gastrointestinal disorders, pulmonary fibrosis, and hepatotoxicity (Citation32,Citation33). Folic acid is often administered to mitigate these side effects (Citation5,Citation6).

The lack of knowledge regarding MTX dosing regimens can be explained by the fact that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved MTX for psoriasis in 1972, a period during which dose range studies were not mandated. However, to compensate for this knowledge gap, dose-dependent safety and effectiveness of MTX have been investigated in rheumatoid arthritis, revealing a correlation between dosage, safety, and effectiveness (Citation34–36). Furthermore, literature reviews and consensus studies on dosing have been conducted for MTX in psoriasis (Citation37–40). Unfortunately, the existing scientific literature lacks clear recommendations regarding MTX dosing specifically for AD.

This systematic review aims to conduct a meta-analysis if possible and provide an overview of the evidence on MTX dosing regimens used for AD, serving as a resource for off-label prescribers and laying the groundwork for future research, including a consensus study on MTX dosing in AD.

Materials and methods

The systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID number: CRD42020211922) and conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Citation41).

Search strategy

A literature search was performed screening all articles published until 6 July 2023 across the MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane (Systematic Reviews and Central of Trials) databases. The search strategies are provided in Table S1.

Study selection

Two authors independently selected articles based on title, abstract, and (if applicable) full text. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and, if necessary, consultation with another author (P.S.) was performed. RCTs were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: five or more patients (children and adults) with AD; oral, subcutaneous, or intramuscular MTX used as a monotherapy (additional topical therapy was permitted); and a clinical outcome parameter of AD is given. Guidelines were included if they provided recommendations regarding aspects of MTX dosing for AD. If a guideline had multiple versions, only the most recent version was included.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted the following information: author, year, and country of publication; patient group demographics; number of patients with MTX treatment; details on MTX use (i.e., test dose, starting dose, maintenance dose, dosing schedule, and dosing adjustments); the use of folic acid; efficacy and safety data and information on monitoring MTX treatment.

Primary outcomes:

RCTs and guidelines: the MTX dosing regimen used or recommended

RCTs: an efficacy outcome such as Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) or SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD)

Secondary outcomes:

RCTs: Quality of life, for example measured with Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

RCTs: Safety (adverse events and tolerability (i.e., withdrawals due to adverse events))

Analysis

Our objective was to conduct a meta-analysis using the extracted data from the included RCTs whenever the available data allowed for it. This involved pooling the data related to physician- and patient-reported outcome measures if they were employed across all RCTs and thus comparable. In cases where the heterogeneity of the studies precluded a meta-analysis descriptive statistics were employed to present a comprehensive overview of the collected data. Included guidelines were analyzed by descriptive statistics to provide an overview of the available guidance on MTX dosing regimens.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias (RoB) in RCTs was assessed by two authors using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool (Citation42). This tool encompasses five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. We specifically assessed the risk of bias for the primary efficacy outcomes in all the included RCTs.

Results

Search and selection results

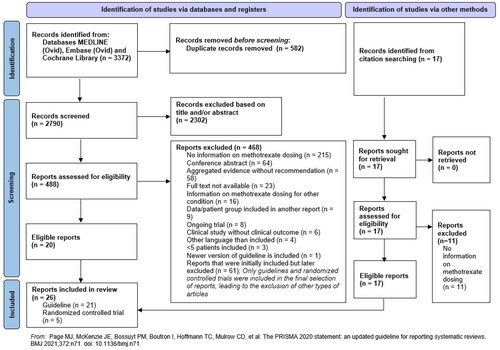

The PRISMA flow diagram () summarizes the selection process. The initial literature search identified a total of 3372 articles. After deduplication 2790 articles underwent screening of their titles and abstracts. This left 488 articles for further evaluation, wherein a full report assessment led to the exclusion of 468 articles. This left 20 articles for inclusion. Additionally, 17 articles identified through citation searching were screened, of which 11 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 6 were included. Ultimately, 26 eligible articles were included, consisting of 5 RCTs (Tables S2–S4) (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation29,Citation30) and 21 guidelines (Citation6–8,Citation10,Citation19,Citation43–56). The main findings are described below.

RCTs

Of the five RCTs, two (Citation15,Citation18) were follow-up studies of the RCT by Schram et al. (Citation16). The RCTs were conducted in the Netherlands (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18), France (Citation30), and Egypt (Citation29). Four RCTs included adults (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation30) and one included children (Citation29). In total 172 patients were randomized. No RCTs comparing different MTX dosing regimens for AD were identified. Instead, the five included RCTs focused on comparing MTX with other treatments, namely, azathioprine and cyclosporine.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was not feasible due to the methodological and clinical heterogeneity of the studies. This was primarily due to the absence of overlapping physician- or patient-reported outcome measures that were expressed in the same unit and assessed at the same time points (see Table S3) and differences in patient population.

MTX dosing regimens

All included RCTs used oral MTX. Four (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation29) out of five employed a test dose. Start doses were 10 mg/week (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18) and 15 mg/week (Citation30) for adults and 7.5 mg/week for children (Citation29). Maintenance doses ranged from 10–22.5 mg/week (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18) to 15–25 mg/week (Citation30) for adults, while for children, it stayed at 7.5 mg/week (Citation29). The frequency of administration was once a week in most RCTs, except in the case of the RCT involving children where it was divided into three doses 12 h apart. Folic acid supplementation was 5 mg/week on the day after MTX (Citation15,Citation16,Citation18) or 5 mg daily except on MTX day (Citation30) for adults and 400 µg/week for children (Citation29). Refer to for a summary of the dosing regimens used (see Table S2 for detailed information).

Table 1. RCTs, MTX dosing regimens.

Efficacy

The SCORAD index, employed by all the included RCTs, serves as a measure to evaluate disease severity, with a potential score range of 0 to 103. A score of < 25 corresponds to mild disease, 25–50 to moderate disease, and ≥50 signifies severe disease. All RCTs showed comparable mean SCORAD indexes at baseline (ranging from 52.6 to 57.9) and week 24 (ranging from 26.9 to 31.4). The reductions in the mean SCORAD ± standard deviation from the original RCTs by El-Khalawany et al. (Citation29), Goujon et al. (Citation30), and Schram et al. (Citation16) were very similar, namely, 26.50 ± 2.24, 26.80 ± 4.15, and 25.70 ± 2.59 at week 24, respectively. More detailed information on SCORAD results can be found in Table S3. Additional outcome measures aligned with the Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) core outcome set (Citation57,Citation58), such as EASI, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), and peak Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), were employed. However, unlike the SCORAD index, no other outcome measures were consistently employed across all RCTs, preventing comparability. This inconsistency extended to measures of quality of life, making an analysis of this aspect unfeasible.

Safety

Adverse events during MTX treatment were observed in the RCTs, although the methods of reporting varied among the studies, making direct comparisons challenging (see Table S4). As a result of this variation in reporting, no correlation could be established between adverse events and dosing regimen. The most frequently reported adverse events included infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevations in liver enzyme levels.

Risk of bias

Table S5 displays the results of the bias risk assessment. The study by El-Khalawany et al. (Citation29) was found to have a high risk of bias due to missing information regarding whether an intention-to-treat analysis was performed, how participant dropouts were managed, and whether they were included in the final analysis. In the study by Schram et al. (Citation16), concerns arose because of the absence of a predefined analysis plan, preventing verification of method consistency. Additionally, none of the RCTs utilized blinding of outcome assessment except for Goujon et al. (Citation30).

Guidelines

Guidance for MTX dosing regimens

21 dermatological guidelines provided explicit recommendations on the dosing regimen of MTX for AD. These guidelines originated from various countries in South America (n = 1) (Citation43), North America (n = 4) (Citation19,Citation48,Citation53,Citation59), Asia (n = 5) (Citation45,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52,Citation60), Europe (n = 10) (Citation6–8,Citation44,Citation46,Citation49,Citation51,Citation55,Citation56,Citation61), and one intercontinental guideline (Citation54). Sixteen guidelines applied to adults and 18 to children. Certain guidelines suggest that dosages should be determined according to weight, age, or body surface area. This implies that not only dosages vary among guidelines, but also the units in which they recommend dosages. This results in a significant diversity that is challenging to summarize. The most commonly mentioned recommendations for each aspect of MTX dosing are summarized in , while more detailed information can be found in Table S6.

Table 2. The most commonly cited recommendations from 21 guidelines regarding MTX dosing for adults and children with AD.

The guidelines were primarily based on the aforementioned RCTs, supplemented by retrospective studies, case series, and expert opinion. Additionally, references were made to MTX guidelines in psoriasis.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the variability and limited evidence and guidance on MTX dosing regimens for AD treatment. The start and maintenance doses in RCTs varied between 7.5–15 mg/week and 14.5–25 mg/week, respectively. These ranges partially coincide with the most frequently recommended start and maintenance doses in adult guidelines; 5–15 mg/week and 7.5–25 mg/week, respectively. However, notable differences exist in the case of pediatric start and maintenance dose recommendations, which were 10–15 mg/m2/week and 0.2–0.7 mg/kg/week respectively. These differences can be attributed in part to the diverse units used to calculate and express dosages in children, encompassing mg/week, mg/kg/week, and mg/m2/week, in contrast to the more standardized units for adults. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that for both adults and children the most commonly advised and used dosing regimen encompass a wide range, without specifying the circumstances under which the prescriber should choose the upper or lower limit of the range. This lack of specific guidance or rationale makes the dosing decision-making process more complex.

When evaluating the efficacy of dosing regimens in the RCTs based on SCORAD outcomes, all regimens show relatively comparable efficacy, which raises the question of whether differences in dosing have significant impact. However, the diversity among the included studies introduces difficulties in establishing dependable conclusions. Furthermore, the inconsistent reporting of adverse events across the studies makes it challenging to thoroughly assess the safety profile of various MTX dosing regimens and their impact on safety. To mitigate side-effects, folic acid was administered in all RCTs and is recommended by almost half of the guidelines. The remaining guidelines neither explicitly mention the use of folic acid nor provide recommendations against its use. This suggests a prevailing consensus in favor of using folic acid supplementation.

A crucial aspect of MTX dosing pertains to the dosing schedule. Our systematic review highlights that the most commonly recommended dosing schedule is once a week; it is the most frequently used dosing schedule in the RCTs and the most frequently recommended dosing schedule in guidelines (see and ). Nevertheless, dosing divided over several days is still frequently mentioned in guidelines (see Table S5) and used in one of the five included RCTs (Citation29). The significance of this topic arises from the fact that MTX has been associated with dosing errors, wherein some patients unintentionally take MTX daily instead of weekly (Citation62,Citation63). Recognizing this issue, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) Safety Committee (PRAC) emphasized the importance of once-weekly dosing for MTX in 2019 (Citation64). Therefore, if a divided dose regimen is chosen, it is crucial to engage in a clear discussion with the patient to ensure their complete understanding of the prescribed regimen and minimize the risk of dosing errors.

Our findings show similarities with systematic reviews concerning MTX dosing in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. In rheumatoid arthritis, optimal dosing involved initiating methotrexate at 15 mg/week orally, escalating by 5 mg/month to 25–30 mg/week, or the highest tolerable dose, and subsequently transitioning to subcutaneous administration if the response was inadequate (Citation36). In psoriasis, recommended starting dosages were commonly 7.5 mg/week and 15 mg/week in RCTs and evidence-aggregated documents, respectively (Citation39). Most psoriasis studies advocate a weekly oral dosing regimen and the widely reported maximum dosage is 25 mg/week or 30 mg/week, surpassing the recommended AD limit of 25 mg/week. There are variating opinions on how the MTX dosing regimen for AD should compare to the one for psoriasis. One European Dermatology Forum (EDF) guideline suggests that the MTX dose for AD should be comparable to or slightly lower than for psoriasis (Citation5). Some argue that the dose for AD should be higher, as studies have shown that systemic T-cell subsets show a higher activation status in AD than in psoriasis (Citation65), and the immunosuppressive effect of MTX is mediated by its ability to induce apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated T cells (Citation66,Citation67). Until more is known, incorporating the psoriasis literature in the decision-making process for AD seems sensible.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review provides an overview of the available evidence on MTX dosing regimens for AD. Certain limitations should be acknowledged. The heterogeneity among the included RCTs prevented the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis and direct comparisons. There were no studies directly comparing the efficacy and safety of different MTX dosing regimens. Specific aspects of MTX treatment, such as cessation, combination therapy, dosing in patients with renal insufficiency, potential interactions, and monitoring were not addressed. Long-term data on this topic are limited. High-quality studies comparing various MTX dosing regimens in AD are necessary for a better substantiation of the appropriate dosing regimen.

Conclusion

This systematic review underscores the variability and limited guidance in MTX dosing for AD treatment. While efficacy comparisons suggest similar outcomes among dosing regimens, heterogeneity of RCTs challenges conclusive findings. We identified the most commonly used and guideline-recommended dosing regimens, making it a valuable resource for off-label prescribers.

Future perspectives

Due to MTX’s affordability and global accessibility, enhancing MTX treatment could significantly benefit the care of numerous AD patients worldwide. However, the lack of strong evidence complicates the ability to make well-informed decisions regarding MTX dosing for AD. While conducting RCTs comparing MTX dosing regimens would be optimal, financial limitations may hinder their feasibility. Alternatively, real-world data from registries can provide valuable insights into daily MTX dosing practices, long-term safety, and effectiveness. Furthermore, the pursuit of globally harmonized guidelines is desirable. As a step toward harmonized MTX treatment, an international eDelphi consensus study, similar to the one for psoriasis (Citation38), is currently underway.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: P.I. Spuls, am van Huizen, and A.G.M. Caron; literature search: N.P. Denswil; study selection and data extraction: M. Bloem, H. El Khattabi, A.C. de Waal, and A.G.M. Caron; data analysis: M. Bloem and A.G.M. Caron; supervision: P.I. Spuls and L.A.A. Gerbens. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.G.M. Caron and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (382 KB)Disclosure statement

P.I. Spuls received departmental independent research grants for the TREAT NL registry from Pharma since December 2019. She is engaged in conducting clinical trials with several pharmaceutical industries producing drugs for treating conditions such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Compensation is provided to the department/hospital for these endeavors. She is Chief Investigator (CI) of the systemic and phototherapy atopic eczema registry (TREAT NL) for adults and children. P.I. Spuls is one of the authors of three of the included follow-up RCTs: Gerbens et al. Schram et al. and Roekevisch et al. P.I. Spuls and L.A.A. Gerbens made contributions to one of the included guidelines authored by Aoki et al. L.A.A. Gerbens is one of the main investigators of the TREAT NL registry. She is the first author of one of the included RCTs: Gerbens et al. and is an author of the EuroGuiDerm guideline authored by Wollenberg et al. A.G.M. Caron and am van Huizen served as a subinvestigators in clinical trials and observational studies for AbbVie and Janssen and as a subinvestigators for the TREAT NL registry.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Vekeman F, et al. Treatment patterns of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a claims data analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.105.

- Abuabara K, Magyari A, McCulloch CE, et al. Prevalence of atopic eczema among patients seen in primary care: data from the health improvement network. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(5):354–356. doi: 10.7326/M18-2246.

- Megna M, Napolitano M, Patruno C, et al. Systemic treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a review [review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7(1):1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0170-1.

- Johansson EK, Brenneche A, Trangbaek D, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with atopic dermatitis in secondary care: a national, observational, non-interventional, retrospective study in Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00774. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.1986.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888.

- Arents BWM, Breukels MA, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, et al. Constitutioneel eczeem - Richtlijn 2019. Nederlandse Vereniging Voor Dermatologie En Venereologie (NVDV) website. 2019. Available from: https://nvdv.nl/professionals/richtlijnen-en-onderzoek/richtlijnen/richtlijn-constitutioneel-eczeem (Accessed: 12 September 2023).

- Damiani G, Calzavara-Pinton P, Stingeni L, et al. Italian guidelines for therapy of atopic dermatitis-adapted from consensus-based european guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis). Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(6):e13121. doi: 10.1111/dth.13121.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717–2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892.

- Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, et al. ETFAD/EADV eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(5):729–747. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13599.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based european guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II [letter. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888.

- Lyakhovitsky A, Barzilai A, Heyman R, et al. Low-dose methotrexate treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(1):43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03351.x.

- Purvis D, Lee M, Agnew K, et al. Long-term effect of methotrexate for childhood atopic dermatitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55(12):1487–1491. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14478.

- Weatherhead SC, Wahie S, Reynolds NJ, et al. An open-label, dose-ranging study of methotrexate for moderate-to-severe adult atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(2):346–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07686.x.

- Chen KS, Tan TH, Yesu PD. Clinical, demographic and laboratory characteristics of methotrexate‐responsive eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2015;11:158–159.

- Gerbens LAA, Hamann SAS, Brouwer MWD, et al. Methotrexate and azathioprine for severe atopic dermatitis: a 5-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial [comparative study, pragmatic clinical trial, randomized controlled trial]. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(6):1288–1296. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16240.

- Schram ME, Roekevisch E, Leeflang MM, et al. A randomized trial of methotrexate versus azathioprine for severe atopic eczema [randomized controlled trial]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.024.

- Shah N, Alhusayen R, Walsh S, et al. Methotrexate in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(5):484–487. doi: 10.1177/1203475418781336.

- Roekevisch E, Schram ME, Leeflang MMG, et al. Methotrexate versus azathioprine in patients with atopic dermatitis: 2-year follow-up data [comparative study letter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):825.e10–827.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.033.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents [practice guideline, research support, N.I.H., extramural]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030.

- Shah RA, Nwannunu CE, Limmer AL, et al. Brief update on dermatologic uses of methotrexate [review]. Skin Therapy Lett. 2019;24(6):5–8.

- Malaviya AN. Landmark papers on the discovery of methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other systemic inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a fascinating story. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(9):844–851. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12862.

- Methotrexate 2.5 mg and 10 mg Tablets SmPC. 2023. Available from: https://www.geneesmiddeleninformatiebank.nl/smpc/h09957_smpc.pdf (Accessed: 12 September 2023).

- Bulur I, Erdoğan HK, Karapınar T, et al. Morphea in middle anatolia, Turkey: a 5-year single-center experience. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34(4):334–338. doi: 10.5114/ada.2017.69313.

- Kjellman P, Eriksson H, Berg P. A retrospective analysis of patients with bullous pemphigoid treated with methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(5):612–616. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.612.

- Lim SL, Kwon IS, Im M, et al. Low-dose systemic methotrexate therapy for recalcitrant alopecia areata. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(3):263–267. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.3.263.

- Eckert L, Amand C, Gadkari A, et al. Treatment patterns in UK adult patients with atopic dermatitis treated with systemic immunosuppressants: data from the health improvement network (THIN). J Dermatol Treat. 2019;31(8):815–820. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1639604.

- Garritsen FM, van den Heuvel JM, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, et al. Use of oral immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(8):1336–1342. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14896.

- Taylor K, Swan DJ, Affleck A, et al. Treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic eczema in adults within the U.K.: results of a national survey of dermatologists. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(6):1617–1623. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15235.

- El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt [comparative study, multicenter study, randomized controlled trial]. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(3):351–356. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1893-3.

- Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Salle D, et al. Methotrexate Versus cyclosporine in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized noninferiority trial [clinical trial, phase III, multicenter study, randomized controlled trial, research support, non-U.S]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):562.e3–569.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.007.

- Law Ping Man S, Bouzille G, Beneton N, et al. Drug survival and postdrug survival of first-line immunosuppressive treatments for atopic dermatitis: comparison between methotrexate and cyclosporine [comparative study]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(8):1327–1335. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14880.

- Prezzano JC, Beck LA. Long-term treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):335–349. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.007.

- Shen S, O’Brien T, Yap LM, et al. The use of methotrexate in dermatology: a review. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00839.x.

- Schnabel A, Reinhold-Keller E, Willmann V, et al. Tolerability of methotrexate starting with 15 or 25 mg/week for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1994;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00302669.

- Verstappen SMM, Jacobs JWG, van der Veen MJ, et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer assisted management in early rheumatoid arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(11):1443–1449. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071092.

- Visser K, van der Heijde D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1094–1099. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092668.

- Menting SP, Dekker PM, Limpens J, et al. Methotrexate dosing regimen for plaque-type psoriasis: a systematic review of the use of test-dose, start-dose, dosing scheme, dose adjustments, maximum dose and folic acid supplementation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):23–28. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2081.

- van Huizen AM, Menting SP, Gyulai R, et al. International eDelphi study to reach consensus on the methotrexate dosing regimen in patients With psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(5):561–572. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0434.

- van Huizen AM, Sikkel R, Caron AGM, et al. Methotrexate dosing regimen for plaque-type psoriasis: an update of a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(8):3104–3118. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2117539.

- Damiani G, Amerio P, Bardazzi F, et al. Real-world experience of methotrexate in the treatment of skin diseases: an Italian Delphi consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13(6):1219–1241. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00930-2.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Aoki V, Lorenzini D, Orfali RL, et al. Consensus on the therapeutic management of atopic dermatitis - Brazilian society of dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(2 Suppl 1):67–75. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.2019940210.

- Chiricozzi A, Belloni Fortina A, Galli E, et al. Current therapeutic paradigm in pediatric atopic dermatitis: practical guidance from a national expert panel [review]. Allergol Immunopathol. 2019;47(2):194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2018.06.008.

- Chow S, Seow CS, Dizon MV, et al. A clinician’s reference guide for the management of atopic dermatitis in asians. Asia Pac Allergy. 2018;8(4):e41. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2018.8.e41.

- Ertam İ, Su Ö, Alper S, et al. The turkish guideline for the diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis-2018. Turkdem - Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2018;52(1):6–23. doi: 10.4274/turkderm.87143.

- Kulthanan K, Tuchinda P, Nitiyarom R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2021;39(3):145–155.

- Lansang P, Lam JM, Marcoux D, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of pediatric patients With atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section III: treatment options for pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(5_suppl):19S–31S. doi: 10.1177/1203475419882647.

- Nowicki RJ, Trzeciak M, Kaczmarski M, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Interdisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society, Polish Society of Allergology, Polish Pediatric Society and Polish Society of Family Medicine. Part II. Systemic treatment and new therapeutic methods. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(2):129–134. doi: 10.5114/ada.2020.94829.

- Parikh D, Dhar S, Ramamoorthy R, et al. Treatment guidelines for atopic dermatitis by ISPD task force 2016. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2018;19(2):108–115. doi: 10.4103/ijpd.IJPD_28_18.

- Popadic S, Gajic-Veljic M, Prcic S, et al. National guidelines for the treatment of atopic dermatitis [review]. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2016;8(3):129–153.

- Rubel D, Thirumoorthy T, Soebaryo RW, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis: an Asia-Pacific perspective. J Dermatol. 2013;40(3):160–171. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12065.

- Sidbury R, Kodama S. Atopic dermatitis guidelines: diagnosis, systemic therapy, and adjunctive care. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.05.008.

- Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the international eczema council [consensus development conference, systematic review]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):623–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.042.

- Deleuran M, Fage S, Bang K, et al. Investigation and treatment of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) (in Danish). Danish Dermatological Society website. 2020. Available from: https://dds.nu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/AD-guideline-oktober-2020.pdf (Accessed: 12 September 2023).

- Tiplica G, Salavastru CM, Szepietowski J, et al. Recommended strategies for atopic dermatitis management in Romania. Ro Med J. 2019;66(4):335–341. doi: 10.37897/RMJ.2019.4.8.

- Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al. The harmonising outcome measures for eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.043.

- Williams HC, Schmitt J, Thomas KS, et al. The HOME core outcome set for clinical trials of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(6):1899–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.03.017.

- Siegfried EC, Arkin LM, Chiu YE, et al. Methotrexate for inflammatory skin disease in pediatric patients: consensus treatment guidelines. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40(5):789–808. doi: 10.1111/pde.15327.

- Yao TC, Wang IJ, Sun HL, et al. Taiwan guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pediatric atopic dermatitis: consensus statement of the Taiwan academy of pediatric allergy, asthma and immunology. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2022;55(4):561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2022.03.004.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I - systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(9):1409–1431. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18345.

- Grissinger M. Severe harm and death associated with errors and drug interactions involving low-dose methotrexate. Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):191–248.

- Vesseur J, Feenstra J. Methotrexaat; fatale doseringsfouten door onoplettendheid. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1996;140(30):1533–1535.

- European Medical Agency (EMA). PRAC recommends new measures to avoid dosing errors with methotrexate. EMA website. 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/methotrexate-article-31-referral-prac-recommends-new-measures-avoid-dosing-errors-methotrexate_en.pdf (Accessed: 12 September 2023).

- Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Shemer A, et al. Skin-homing and systemic T-cell subsets show higher activation in atopic dermatitis versus psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.032.

- Genestier L, Paillot R, Fournel S, et al. Immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate: apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated peripheral T cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(2):322–328. doi: 10.1172/JCI2676.

- Goujon C, Nicolas JF, Nosbaum A. Methotrexate in atopic eczema. Comments to: consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(4):e154–e155. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15386.