Abstract

Background

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a prevalent dermatologic disease that negatively affects life, current therapies remain suboptimal. Hence, there is an urgent need to identify effective and safe treatment.

Objective

Assess the efficacy and safety of compound glycyrrhizin (CG) combined with second-generation nonsedated antihistamine for the treatment of CU.

Methods

Nine databases were queried to screen RCTs related. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias using Cochrane Collaboration. Primary objective was the total efficiency rate, while secondary was rate of recurrence, adverse events, and cure. Statistical analyses using Review Manager 5.4 and Stata17.

Results

Twenty-four RCTs were identified. Significant differences were noted in rate of total efficiency (n = 2649, RR = 1.36, 95%CI:1.30–1.43, p < 0.00001), cure (n = 2649, RR = 1.54, 95%CI:1.42–1.66, p < 0.00001) and recurrence (n = 446, RR = 0.34, 95%CI:0.20–0.58, p < 0.00001) between the combination of CG with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine and antihistamine monotherapy. Contrastingly, adverse events rate (n = 2317, RR = 0.76, 95% CI:0.59–0.97, p = 0.03) was comparable between the two groups. Our results indicated that CG combined with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine could significantly mitigate the symptoms in CU compared with antihistamine monotherapy. No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

CG combined with second-generation nonsedated antihistamine is effective for CU. Nevertheless, higher-quality studies are warranted to validate our results.

1. Introduction

Urticaria is a disease characterized by rashes (hives), angioedema, or both (Citation1,Citation2). Its clinical manifestations are often accompanied by pruritus, and its etiology is generally challenging to determine (Citation3). Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as urticaria persisting for over 6 weeks (Citation4). It affects a significant portion of the population globally, appears to be more prevalent in Asians (Citation5). The duration of CU generally ranges from 1 to 5 years and may be longer in severe cases (Citation6). According to its pathogenic factors, CU can be categorized into chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and chronic inducible urticaria (CIU); they may occur simultaneously or independently (Citation7,Citation8). Current guidelines recommend the continuous use of standard-dose second-generation nonsedated H1-antihistamine, at the lowest effective dose, as first-line therapy for CU (Citation2,Citation9,Citation10). Nevertheless, the response of several patients to licensed doses remains suboptimal (Citation11).

Herbal medicines are commonly used as complementary and alternative medicines in Western countries, particularly in the United States and United Kingdom, where up to 50% of patients with dermatological disorders use them in combination with traditional therapies (Citation12–14). Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) is a commonly administered Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) (Citation15) that exerts anti-allergic effects (Citation16). Meanwhile, compound glycyrrhizin (CG) is composed of monoammonium glycyrrhizinate, glycine L, and half cystine and exerts anti-allergic effects as well as boosts immunity (Citation17–19). It is widely used for the treatment of dermatological diseases and generally has an acceptable safety profile (Citation20). In the past few years, clinicians have opted for the combination of CG with antihistamine, such as loratadine and levocetirizine, for the treatment of CU. Indeed, numerous clinical trials have established that this combination is effective for the treatment of CU. However, CG dosage formulations and antihistamine options remain limited. This study was designed to systematically evaluate the efficacy and safety of CG (including tablet, capsule, and injection) combined with second-generation nonsedated antihistamine for the treatment of CU and to provide a theoretical basis for rational drug use in the clinical setting. Additionally, the purpose of this meta-analysis was to elucidate the clinical efficacy of the drugs in order to discover optimized treatment options for CU in the future.

2. Method

This review was performed in accordance with the declaration of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) (Table S1).

2.1. Protocol registration

The protocol for this study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with the number CRD42020156153, as published in Medicine (Citation21). The review methodology was in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols and the Cochrane Handbook (Citation22). All reviewers underwent standardized training to guarantee a comprehensive understanding of the manuscript-reviewing process, including its context and purpose.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included following the PICOS principles (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design). Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) enrolling CU patients were eligible for inclusion in this study. Interventions were CG combined with a second-generation non-sedated antihistamine or conventional second-generation nonsedated antihistamine monotherapy. Based on the guidelines (Citation2,Citation23), the domestic clinical efficacy evaluation criteria for chronic urticaria-Urticaria Symptom Score Reduction Index (SSRI) was employed to evaluate efficacy (Citation24). SSRI was calculated as follows: SSRI = (symptom score before treatment-symptom score after treatment)/symptom score before treatment × 100%. SSRI ≥ 90% indicated that the patients were cured, the significantly effective rate was classified as 60% < SSRI < 89%, slight improvement as 20% < SSRI < 60%, and the rate of invalidity as SSRI ≤ 20%. The total efficiency rate equals significantly effective rate + cure rate. Studies in which the treatment group received additional drugs, encompassing vitamins or Chinese medicine, were excluded. Likewise, trials that did not report primary objectives or those with ambiguous outcome indicators, for which we were unable to acquire the necessary information from the authors, were excluded from this analysis.

2.3. Search strategy

The Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Database, Wangfang, and China Biology Medicine (CBM) databases were queried for RCTs on CG combined with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine for the treatment of CU from database inception to May 31st, 2022. The search algorithm utilized a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) subject headings and free terms, specifically: ‘chronic urticaria’ OR ‘chronic urticarias’ OR ‘urticaria, chronica’, and ‘antihistamine’ OR ‘histamine antagonists’, and ‘compound glycyrrhizin’ OR ‘glycyrrhizin’. Next, the identified studies were manually screened. The search strategy in the different databases is summarized in Table S2.

2.4. Data extraction

The articles were independently screened by two researchers (QY and ZHZ). After eliminating duplicate studies, the titles and abstracts for the remaining articles were reviewed, and the full texts of studies that appeared to meet the selection criteria were meticulously examined. Disagreements were arbitrated by a third researcher (SJC). The following information was independently extracted from the studies by two reviewers (WC and LW): the first author, publication year, demographic characteristics (age and gender), interventions, outcome indicators, and other information. Discrepancies were resolved by a third researcher (SJC).

2.5. Risk of bias assessment

The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs (Cochrane RoB 2.0) was employed by two reviewers (QY and ZHZ) to assess the risk of bias in each study. This evaluation considered elements such as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients and trial personnel, deviations from expected interventions, lack of outcome data, and selection of reported outcomes. Disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third researcher (SJC).

2.6. Evidence quality evaluation

The evidence for outcome indicators was graded using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework. Evaluations included limitations, inconsistencies, discontinuities, and imprecision. Reporting bias was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low in terms of quality of evidence.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Review Manager 5.4 software. The relative risk (RR) was used as a measure of effect for dichotomous variables, whereas the mean difference (MD) was used for continuous variables, both presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The I2 test was used to examine heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was low (I2≤50%, p ≥ 0.1), a fixed-effect model was adopted. Contrastingly, a random-effect model was adopted if heterogeneity was high (I2>50%, p < 0.1). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Citation25,Citation26). Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were carried out to identify the source of heterogeneity when I2≥ 50%. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the formulation of CG (tablet, capsule, injection). Sensitivity analyses were performed by repeatedly excluding a specific study to assess whether particular trials significantly affected heterogeneity and pooled effects. Funnel plots were used to detect publication bias for the primary outcome indicator.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

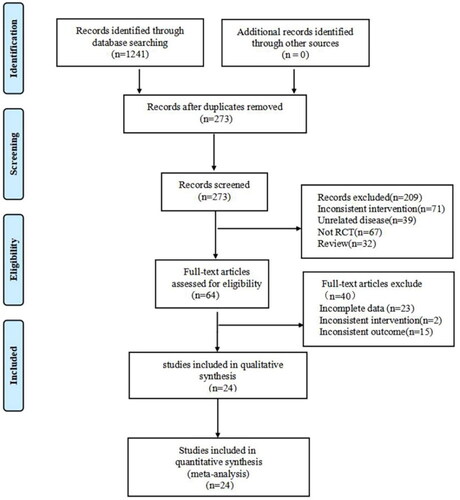

As illustrated in , the initial search strategy yielded a total of 1241 citations. Among them, none of the literature was derived from the Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, PubMed, or MEDLINE databases, while 272 articles were retrieved from CNKI, 378 from Wan Fang, 300 from VIP, and 291 from CBM. After excluding 968 duplicate articles, 273 studies were retained. Then, 209 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria of this study (Inconsistency of intervention, unrelated diseases, nonrandomized study design, and case review). Among the remaining 64 articles, 40 did not meet all inclusion criteria (incomplete data, inconsistent interventions, and inconsistent outcomes) and were therefore excluded. Eventually, 24 eligible studies (Citation27–50) were included in this study.

All 24 included studies were single-center studies with a sample size ranging from 35 to 130 participants. Patients were exclusively of Chinese descent, with ages ranging from 5 to 72 years and disease courses ranging from 6 weeks to 18 years. All studies compared the effectiveness of the combination of CG with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine to antihistamine monotherapy. The generic names of second-generation non-sedated antihistamine administered in these studies comprised desloratadine, levocetirizine hydrochloride, loratadine, mizolastine, epinastine, cetirizine hydrochloride, levocetirizine, ebastine, phenopenadine hydrochloride, epistin hydrochloride, and cetirizine. Participant characteristics, drug history, controls, and outcome measures are detailed in .

Table 1. Studies included.

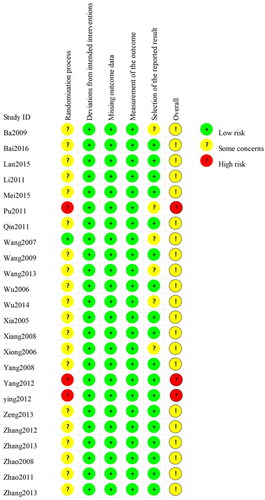

3.2. Risk of bias assessment

None of the studies provided detailed descriptions of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. A high risk of bias was reported in three studies owing to unclarities on whether a random element was used in the generation of the allocation sequence. displays the results of the bias risk assessment.

3.3. Outcomes measurements

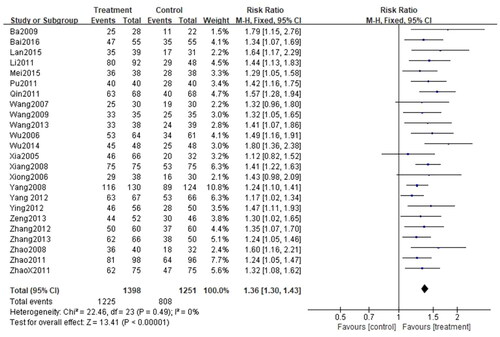

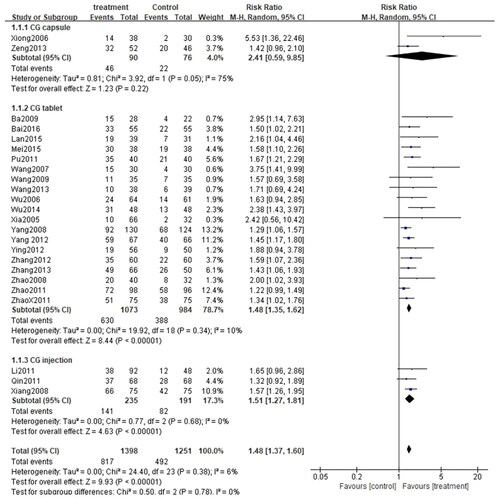

3.3.1. Total efficiency rate

All 24 studies (Citation27–50) assessed the total efficiency rate, with a total of 2649 patients, including 1398 cases in the treatment group and 1251 cases in the control group. Given that I2<50% (p = 0.49, I2=0%), the fixed-effect model was applied. There was a significant difference in the total efficiency rate between the two groups. In other words, the total efficiency rate of patients treated with CG, in conjunction with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine, was significantly higher than that of patients treated with antihistamine alone (n = 2649, RR = 1.36, 95%CI:1.30–1.43, p < 0.00001) ().

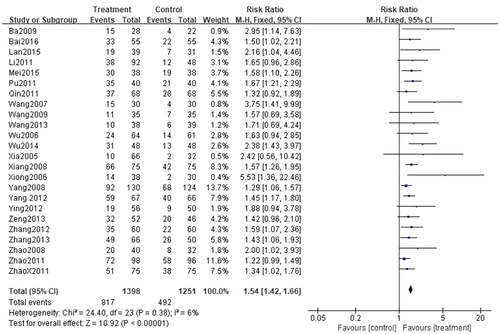

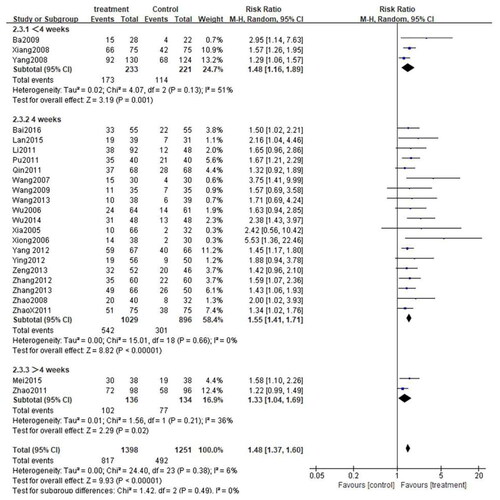

3.3.2. Cure rate

This indicator was recorded in all 24 studies (Citation27–50). Considering that I2<50% (p = 0.38, I2=6%), the fixed-effect model was applied for analysis. There was a significant difference between the two groups. Indeed, patients treated with the combination of CG and second-generation nonsedated antihistamine had a significantly higher cure rate than those treated with antihistamine alone (n = 2649, RR = 1.54, 95%CI:1.42–1.66, p < 0.00001) ().

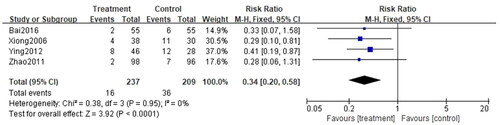

3.3.3. Recurrence rate

Recurrence rate was reported in 4 studies (Citation28,Citation38,Citation45,Citation46), involving a total of 446 cases, with 237 cases in the treatment group and 209 participants in the control group. Ascribed to the low heterogeneity (p = 0.95, I2=0%), the fixed-effect model was applied for analysis. The recurrence rate for patients treated with the combination of CG and second-generation non-sedated antihistamine was significantly lower than that of antihistamine alone. Additionally, follow-up post-treatment revealed a significant difference in the prevention of urticaria recurrence between the two groups (n = 446, RR = 0.34, 95%CI:0.20-0.58, p < 0.00001) ().

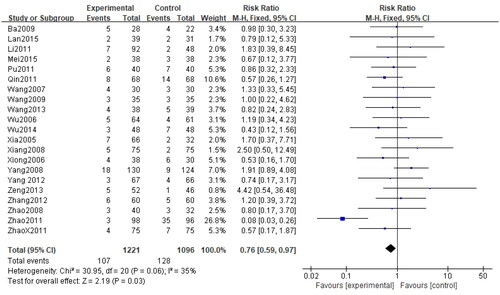

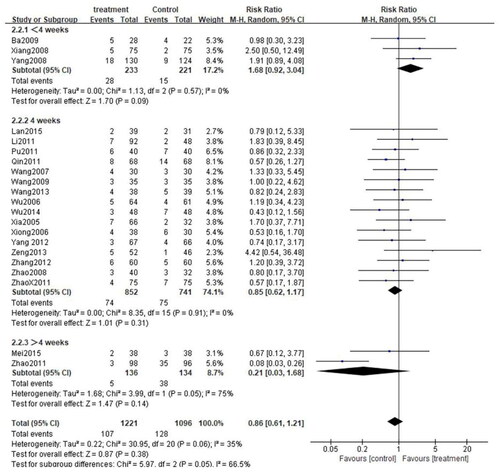

3.3.4. Rate of adverse events

Among 24 RCTs, 21 studies (Citation28–37,Citation39–44,Citation46–50) evaluated the frequency of adverse events. A total of 2317 cases of CU were documented, including 1221 in the treatment group and 1096 in the control group. Given the low heterogeneity among studies (p = 0.06, I2=35%), the fixed-effect model was selected for the analysis. The results revealed that the rates of adverse events were comparable between the two groups (n = 2317, RR = 0.76, 95%CI:0.59–0.97, p = 0.03) ().

3.4. Subgroup analysis

In order to investigate the influence of different intervention factors on the outcomes, subgroup analysis was performed according to the treatment duration and the formulation of CG.

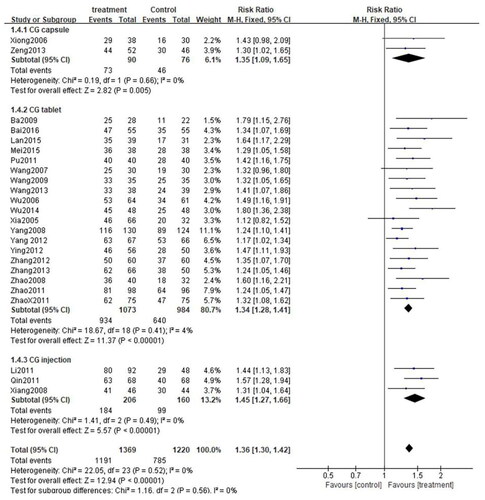

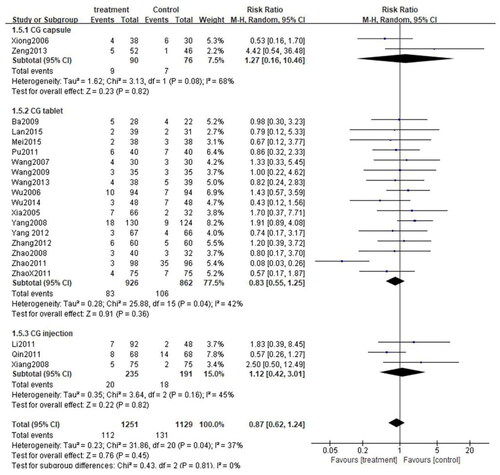

3.4.1. CG formulation

These 24 studies were stratified into three categories based on the formulation used in the studies: CG capsule, CG tablet, and CG injection. Since there was no significant heterogeneity among the three subgroups (CG capsule: p = 0.66, I2=0%; CG tablet: p = 0.41, I2=4%; CG injection: p = 0.49, I2=0%), the fixed-effect model was adopted. As anticipated, the total efficiency rate of each subgroup was significantly higher than that of the control group (CG capsule: [RR = 1.35, 95%CI: 1.09–1.65, p = 0.005]; CG tablet: [RR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.28–1.41, p < 0.00001]; CG injection:[RR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.27–1.66, p < 0.00001]) (). Similarly, subgroup analysis was performed on the rate of adverse events. Owing to high heterogeneity among the three subgroups (CG capsule: p = 0.08, I2=68%; CG tablet: p = 0.04, I2=42%; CG injection: p = 0.16, I2=45%), the random effects model was applied. The results exposed that the rate of adverse events was comparable between each subgroup and the control group (CG capsule:[RR = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.16–10.46, p = 0.82]; CG tablet: [RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.55–1.25, p = 0.36]; CG injection: [RR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.42–3.01, p = 0.82]) (). Besides, subgroup analysis was performed for the cure rate. Given the low heterogeneity among the subgroups (CG capsule: p = 0.05, I2=75%; CG tablet: p = 0.34, I2=10%; CG injection: p = 0.68, I2=0%), the fixed-effect model was applied. Interestingly, the cure rate in the CG tablet and injection subgroups was significantly higher than that of the control group (CG tablet: [RR = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.35–1.62, p < 0.00001]; CG injection: [[RR = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.27–1.81, p < 0.00001]. On the other hand, the cure rate was similar between the CG capsule subgroup and the control group (CG capsule: [RR = 2.41, 95%CI: 0.59–9.85, p = 0.22]) ().

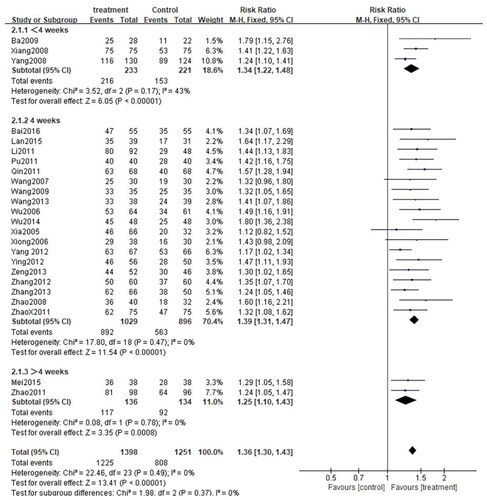

3.4.2. Treatment duration

Depending on the treatment duration, the CG combined with the second-generation nonsedated antihistamine group was further stratified into three subgroups: <4 weeks, 4 weeks, and >4 weeks. Given the low heterogeneity among the three subgroups (<4 weeks: p = 0.17, I2=43%; 4 weeks: p = 0.47, I2=0%, >4 weeks: p = 0.78, I2=0%), the fixed-effect model was adopted. As expected, the total efficiency rate was significantly higher in all subgroups compared to that in the control group(< 4 weeks: [RR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.22–1.48, p < 0.00001]; 4 weeks: [RR = 1.39, 95%CI: 1.31–1.47, p < 0.00001]; >4 weeks: [RR = 1.25. 95%CI: 1.10–1.43, p = 0.0008]) (). Subgroup analysis was also carried out for the rate of adverse events. Due to the high heterogeneity among the three subgroups (<4 weeks: p = 0.57, I2 = 0%; 4 weeks: p = 0.91, I2 = 0%, >4 weeks: p = 0.05, I2 = 75%), the random effects model was adopted. The results demonstrated that the rate of adverse events among the three subgroups was comparable to that in the control group. (< 4 weeks: [RR = 1.68, 95%CI: 0.92–3,04, p = 0.09]; 4 weeks: [RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.62–1.17, p = 0.31]; >4 weeks: [RR = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.03–1.68, p = 0.14]) (). What is more, a subgroup analysis of cure rates was also performed. Due to the high heterogeneity between subgroups (<4 weeks: p = 0.13, I2 = 51%; 4 weeks: p = 0.66, I2 = 0%, >4 weeks: p = 0.21, I2 = 36%), the random effects model was used. The cure rate in all subgroups was significantly higher than that in the control group (<4 weeks: [RR = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.16–1.89, p = 0.001]; 4 weeks: [RR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.41–1.71, p < 0.00001]; > 4 weeks: [RR = 1.33. 95%CI: 1.04–1.69, p = 0.02]) ().

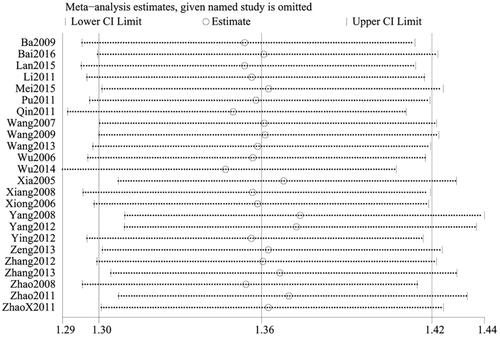

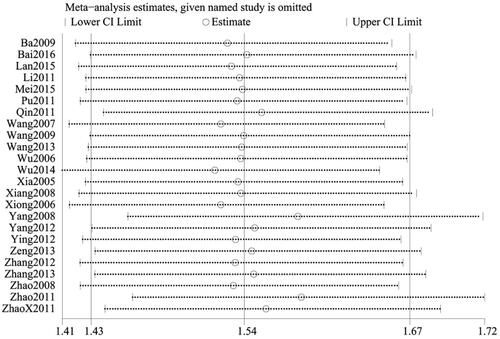

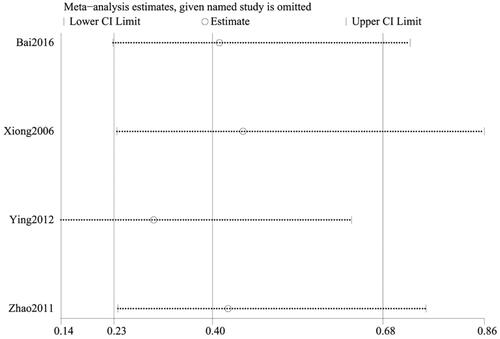

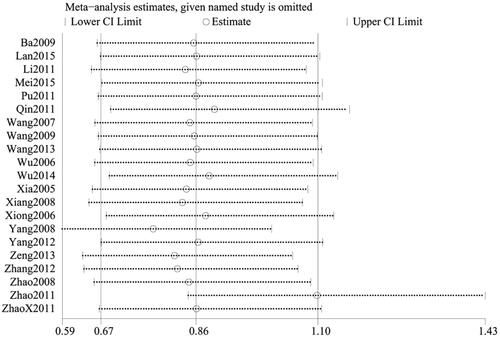

3.5. Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the reliability of our results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the one-by-one elimination method. After excluding each study, there was minimal fluctuation within a narrow range of the 95%CI. Additionally, the total efficiency rate, cure rate, and recurrence rate results remained statistically significant in the remaining studies, highlighting the reliability of our results. Conversely, the pooled results of the remaining studies were not statistically significant for the rate of adverse events (95%CI including 1) after excluding the majority of studies, which was consistent with the original findings, suggesting that the results of the meta-analysis did not significantly alter despite changes in the number of studies ().

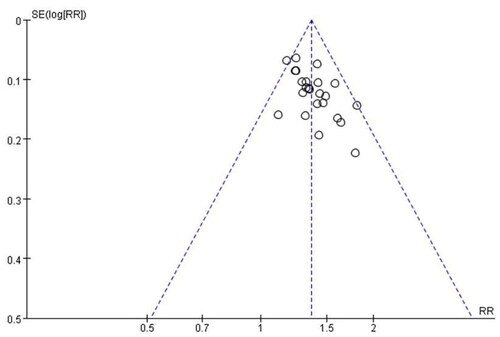

3.6. Publication bias

Publication bias for the primary outcome measure was examined using a funnel plot, which exhibited an asymmetric shape, suggesting the possibility of publication bias ().

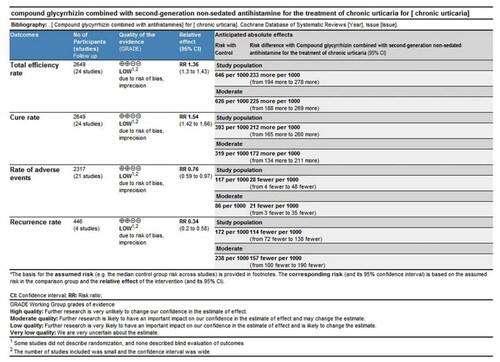

3.7. Overall quality of evidence by GRADE

The quality of all outcomes was assessed using the GRADE system (). Evidence quality for the total efficiency rate, cure rate, rate of adverse events, and recurrence rate was rated as "LOW", "LOW", "LOW", and "LOW". Downgrading factors included the absence of detailed randomization descriptions in some studies and the lack of blinded outcome evaluations. In addition, the limited number of included studies resulted in wide confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

This study systematically reviewed 24 RCTs on the combination of CG with second-generation non-sedated antihistamine for the treatment of CU. The results indicated that combination therapy was superior to antihistamine monotherapy in terms of total efficiency rate, cure rate, and recurrence rate. Notably, the recurrence rate was significantly lower using CG combined with antihistamine compared with antihistamine monotherapy, presenting a significant prognostic advantage. In terms of the rate of adverse events, there was no significant significance between the two groups. This observation signifies that the use of combination therapy does not significantly elevate the risk of adverse events.

To assess the impact of different factors on the outcomes, subgroup analyses based on CG formulation and treatment duration were performed. Regardless of the duration of treatment or formulation, the rate of adverse events was not statistically different. On the other hand, each subgroup outperformed the control group in terms of the total effective rate and cure rates. Similarly, CG tablets and injections, in combination with antihistamine, yielded higher cure rates compared to antihistamine monotherapy. Nonetheless, there was no evidence that the cure rates were higher using CG capsules compared to the control group.

TCM plays a vital role in complementary and alternative therapies (Citation51). Licorice is a type of Chinese herbal medicine classified under ‘medicine and food homology’ that is extensively used as a health food and natural sweetener. Of note, it possesses anti-tumorigenic, anti-bacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties and thus is conducive to the treatment of dermatologic, hepatic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular diseases (Citation43–47). It is worthwhile emphasizing that it contains several naturally active compounds, including over 20 triterpenes, 300 flavonoids, licorice extract, 3 triterpenes, and 13 flavonoids. It decreases the levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs), prostaglandin E2(PGE2), and free radicals, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects (Citation52). Existing evidence from experimental studies suggests that licorice extracts, in particular glycyrrhizin and its derivatives, are efficacious for the treatment of dermatological disorders (Citation15).

Compared to previous systematic reviews (Citation53–55), there were no restrictions in the formulation of CG and the types of antihistamine in our study, thereby encompassing more diverse treatment modalities. Indeed, our study also considered different formulations of CG and treatment durations. Our results implied that irrespective of the CG formulation and type of antihistamine used, the combination of CG and a second-generation non-sedate antihistamine significantly reduced urticaria symptom scores in CU patients. Moreover, the rate of adverse events was comparable to that of antihistamine monotherapy. Methodologically, the quality of the included studies was assessed using the current Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2), which is universally recognized for its systematic evaluation of intervention effects (Citation56). Noteworthily, RoB 2 is more elaborate and comprehensive than the Cochrane Risk of Bias Risk Assessment Tool (Citation57). Besides, given that the GRADE system is widely applied in medicine and public health for determining the certainty of evidence outcomes in systematic reviews (Citation58), it was used to assess the strength of our findings.

5. Limitations

This study has some limitations that merit acknowledgment. First of all, articles were retrieved from only Chinese and English databases. Secondly, all included studies were undertaken in China, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings to a global population. Thirdly, all studies were single-center studies. Multicenter RCTs are necessitated in the future to ensure a wider global dissemination. Secondly, CU, a chronic disease, requires a relatively longer follow-up duration. However, only four RCTs reported follow-up recurrence data. Lastly, while all studies performed randomization, none explicitly detailed the method of random sequence generation.

6. Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that the combination of CG with a second-generation non-sedated antihistamine is effective and safe for the treatment of CU, particularly in alleviating clinical manifestations. Due to the limited quality of evidence included in the studies, additional larger-sample, high-quality RCTs with long-term follow-up durations are warranted to validate our findings.

Author’s contributions

Conception and design: SJC, WC

Administrative support: XJX and YL

Provision of study materials or patients: QY, ZHZ

Collection and assembly of data: WC, LW

Data analysis and interpretation: QY, ZHZ and SJC

Writing – original draft: SJC and WC contributed equally to this work as co-first authors

Writing – review & editing: XJX, RHW

All authors contributed to the research and allowed the submission.

Supplementary data description

Supplementary data to this article ( Studies included/Table S1 PRISMA_2020_checklist/Table S2 Search strategy) has been submitted as a supplementary material.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (379.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Saini S, Shams M, Bernstein JA, et al. Urticaria and angioedema across the ages. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.030.

- Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77(3):734–766. doi: 10.1111/all.15090.

- Corral-Magaña O, Gil-Sánchez JA, Bover-Bauzá C, et al. Chronic urticaria in children under 15 years of age: clinical experience beyond the clinical trials. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(2):385–389. doi: 10.1111/pde.14455.

- He L, Yi W, Huang X, et al. Chronic urticaria: advances in understanding of the disease and clinical management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61(3):424–448. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08886-x.

- Fricke J, Ávila G, Keller T, et al. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75(2):423–432. doi: 10.1111/all.14037.

- Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x.

- Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: latest developments in aetiology, diagnosis and therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(6):304–313. doi: 10.1177/2040622315603951.

- SáNCHEZ J, Amaya E, Acevedo A, et al. Prevalence of inducible urticaria in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: associated risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.029.

- Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. Methods report on the development of the 2013 revision and update of the EAACI/GA2 LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2014;69(7):e1-29–29. doi: 10.1111/all.12370.

- Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1393–1414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397.

- Cataldi M, Maurer M, Taglialatela M, et al. Cardiac safety of second-generation H(1) -antihistamines when updosed in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(12):1615–1623. doi: 10.1111/cea.13500.

- Fuhrmann T, Smith N, Tausk F. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with skin disease: updated results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(6):1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.009.

- Baron SE, Goodwin RG, Nicolau N, et al. Use of complementary medicine among outpatients with dermatologic conditions within yorkshire and South Wales, United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(4):589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.058.

- Smith N, Shin DB, Brauer JA, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with skin disease: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(3):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.905.

- Yu JJ, Zhang CS, Coyle ME, et al. Compound glycyrrhizin plus conventional therapy for psoriasis vulgaris: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(2):279–287. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1254605.

- VAN Rossum TG, Vulto AG, DE Man RA, et al. Review article: glycyrrhizin as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(3):199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00309.x.

- Wang J, Yu S, Xiao W. Clinical application of compound glycyrrhizin (meineng) in liver disease [J]. China Pharmacy. 2002;08:52–54. (in Chinese).

- Segal R, Pisanty S. Glycyrrhizin gel as a vehicle for idoxuridine–I. Clinical investigations. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1987;12(3):165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1987.tb00522.x.

- Khaksa G, Zolfaghari ME, Dehpour AR, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive activity of disodium glycyrrhetinic acid hemiphthalate. Planta Med. 1996;62(4):326–328. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957894.

- Cheng Zhuhai DSCT. Pharmacokinetics and clinical application of compound glycyrrhizin. Chinese J Modern Appl Pharm. 2005;22(0z3):830–832. (in Chinese).

- Cao W, Xiao X, Zhang L, et al. Compound glycyrrhizin combined with antihistamines for chronic urticaria: a protocol for systematic review and meta analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(33):e21624.), doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000021624.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- URTICARIA RESEARCH CENTER D A V S C M A. Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of urticaria 2018 edition. Chinese J Dermatol(Zhonghua Pifuke Zazhi). 2019;52(1):5. (in Chinese). doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2019.01.001.

- Shi CXG, Wang M, ET AL. Investigation on evaluation criteria of clinical efficacy of chronic urticaria in China. Chinese J Med Library Inform Sci. 2014;12:5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-3982.2014.12.011.

- Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. [M/OL]. 2014

- Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10(10):Ed000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.Ed000142.

- Zhang J, Yang Y, Jiang G, et al. Observation of clinical efficiency of desloratadine combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of 66 patients with chronic urticaria. Chinese J Dermatovenereol. 2013;27(7):755–756. (in Chinese).

- Zhao H, Peng X, Yang S. Effect observation of desloratadine combined compound glycyrrhizin in treatment of chronic urticaria. J Med Forum. 2011;32(7):53–55. (in Chinese).

- Yang Yuming MP. Therapeutic effect of desloratadine plus compoud glycyrrhizin intreatment of chronic urticaria. Channel Pharmacy. 2008;20(10):100–101. (in Chinese).

- Wang Shiming CY. Clinical observation of 30 cases of chronic urticaria treated by compound glycyrrhizin combined with desloratadine. J Zunyi Med Univ. 2007;118(01):58–59. (in Chinese).

- Yongzhong W. Efficacy of compound glycyrrhizin combined with desloratadine in the treatment of chronic urticaria. J Diag Therapy Dermato-Venereolog. 2006;13(3):227–229. (in Chinese).

- Yingzhu B. The treatment of compound glycyrrhizin combined with loratadine was slow clinical observation of sexual urticaria. Northwest Pharmaceut J. 2009;24(3):213–214. (in Chinese).

- Xia Jianxin ZF, Yinghui CUI. Effect of compound glycyrrhizin combined with mizolastine in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Food and Drug. 2005;7(11):67–68. (in Chinese).

- Jing W. Observation of clinical efficacy of compound glycyrrhizin combined with cetirizine in treatment of chronic urticaria. Med J Chinese People’s Health. 2014;26(21):76–77. (in Chinese).

- Yang Yanlong JG, Jin Z. Effect of compound glycyrrhizin combined with fexofenadine hydrochloride on chronic urticaria. China J Leprosy Skin Dis. 2012;28(05):371. (in Chinese).

- Jianhua P. Observation of curative effects on treating chronic urticaria with compound glycyrrhizin concomitant with cetirizine. Chinese J Med Guide. 2011;13(1):71–72. (in Chinese).

- Zeng Zhaolin LJ, Huifang YANG, Xiaoying YE. Effect of compound glycyrrhizin combined with epistin hydrochloride on chronic urticaria. J China Prescrip Drug. 2013;11(6):41–42. (in Chinese).

- Mengxia Y. Efficacy of compound glycyrrhizin combined with levoxitirizine hydrochloride tablets in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Modern Pract Med. 2012;25(2):181–182. (in Chinese).

- Xia Z. Clinical observation of compound glycyrrhizin combined with levocetirizine dihydrochloride in treatment of chronic urticaria. Chinese Foreign Med Res. 2011;9(23):13–14. (in Chinese).

- Mei Zhen YX, Jieping C. Clinical observation of compound glycyrrhizin combined with epistin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Chinese J Clin Rational Drug Use. 2015;8(32):69–70. (in Chinese).

- Jinru W. Effect analysis of compound glycyrrhizin combined with levoxitirizine in the treatment of chronic urticaria in children. Front Med. 2013;(25):219–220. (in Chinese).

- Wang Lixia GC, Xiaoning Z. Effect of compound glycyrrhizin combined with levocetirizine in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Dermatol Venereol. 2009;31(1):28–37. (in Chinese).

- Man LAY. The clinical observation of compound glycyrrhizin injection combined with mizolastine in treatment of chronic urticaria. Clin Misdiagnosis Mistherapy. 2011;24(11):19–21. (in Chinese).

- Ye L. Efficacy of desloratadine citrate combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Journal of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine. 2015;38(6):57–60. (in Chinese).

- Minghui B. Clinical study of desloratadine citrate combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. China J Leprosy Skin Dis. 2016;32(9):546–566. (in Chinese).

- Ying X. Therapeutic effect of meilone tablet combined with cetirizine hydrochloride on chronic urticaria. China J Leprosy Skin Dis. 2006;22(10):878–879. (in Chinese).

- Jianguang X. Efficacy of mizolastine combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. China Pract Med. 2008;3(29):91–92. (in Chinese).

- Zhang Yunying ZR, Zhao YE, Caixia TU. Effect of epistin hydrochloride combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Chinese J Dermatovenereol Integ Trad Western Med. 2012;11(2):116. (in Chinese).

- Jigao Q. Clinical observation of levoxitirizine hydrochloride capsule combined with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria [J]. Chinese Aesthetic Med. 2011;20(5):285. (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-6455.2011.z5.297.

- Zhao Chunhua QX. Effect of epistin combined with compound glycyrrhizin on chronic urticaria. China Foreign Med Treat. 2008;28(10):125–174. (in Chinese).

- Jin G, Jin LL, Jin BX. The rationale behind the four major anti-COVID-19 principles of chinese herbal medicine based on systems medicine. Acupunct Herb Med. 2021;1(2):90–98. doi: 10.1097/HM9.0000000000000019.

- Rui Y, Yuan BC, Ma YS, et al. The anti-inflammatory activity of licorice, a widely used Chinese herb. Pharm Biol. 2017;55(1):5–18. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1225775.

- Wen Y, Tang Y, Li M, et al. Efficiency and safety of desloratadine in combination with compound glycyrrhizin in the treatment of chronic urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pharm Biol. 2021;59(1):1276–1285. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2021.1973039.

- Lu Tao ZK, Jin-Bo ZOU, Xiao-Lin1 DU, et al. Compound glycyrrhizic acid glycosides combine with cetirizine for chronic urticaria: a systematic review of efficacy and safety. Chinese J Dermatovenereol. 2013;27(11):1083–1087. (in Chinese).

- Peng-Fei Z. Efficacy and safety of compound glycyrrhizin combined with levocetirizine in the treatment of chronic urticaria: a meta-analysis. Clin Medication J. 2022;20(2):60–66. (in Chinese).

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Minozzi S, Cinquini M, Gianola S, et al. The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) showed low interrater reliability and challenges in its application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;126:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.015.

- Schwingshackl L, Rüschemeyer G, Meerpohl JJ. [How to interpret the certainty of evidence based on GRADE (grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation)] [J]. Urologe A. 2021;60(4):444–454. doi: 10.1007/s00120-021-01471-2.