Abstract

Purpose: Ruxolitinib (selective Janus kinase [JAK] 1 and JAK2 inhibitor) cream demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) in the phase 3 TRuE-AD studies. In TRuE-AD1/TRuE-AD2 (NCT03745638/NCT03745651), adults and adolescents with mild to moderate AD were randomized to apply twice-daily ruxolitinib cream or vehicle for eight weeks. Here, we evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of ruxolitinib cream by anatomic region, focusing on head/neck (HN) lesions that are typically difficult to manage and disproportionately affect quality of life (QoL).

Materials and methods: Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) responses in anatomic regions were evaluated in the pooled population (N = 1208) and among patients with baseline HN involvement (n = 663). Itch, Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), QoL, and application site tolerability were also assessed.

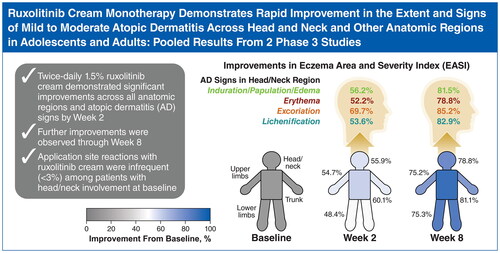

Results: By Week 2 (earliest assessment), ruxolitinib cream application resulted in significant improvements across all EASI anatomic region subscores and AD signs versus vehicle, with further improvements through Week 8. Significantly more patients with HN involvement who applied ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle achieved clinically meaningful improvements in itch, IGA, and QoL. Application site reactions with ruxolitinib cream were infrequent (<3%), including in patients with HN involvement.

Conclusions: These results support the use of ruxolitinib cream for AD treatment across all anatomic regions, including HN.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a highly pruritic, inflammatory skin disease that can affect multiple regions of the body, including the head and neck (Citation1,Citation2). Head and neck involvement is more common in children but is also frequent among adults (Citation2,Citation3). AD involvement in body regions differentially affects patient quality of life (QoL) (Citation2,Citation4). AD lesions on highly visible areas, including the face, are associated with reduced QoL compared with other body regions, such as the back and pelvis (Citation4,Citation5). Similarly, AD may also be challenging to treat depending on body region affected (Citation6,Citation7) as treatment options are more limited for sensitive areas, such as the face (Citation8). For example, irritation and burning in sensitive regions may be exacerbated by treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and crisaborole (Citation8,Citation9). Prolonged use of topical corticosteroids can be associated with skin atrophy, periorificial dermatitis, rebound dermatitis, hypopigmentation, rosacea, and striae (Citation1,Citation3,Citation10–12), which may be increased in sensitive areas, including the face and skin folds (Citation8,Citation13). Because AD is a chronic disease with episodes of acute disease flare (Citation1), there is a need for effective and well-tolerated treatments that can be used long term, particularly on sensitive areas (e.g., head and neck), to maintain disease control.

Janus kinases (JAKs) mediate proinflammatory cytokines in skin and sensory neurons and thus play an important role in the development of itch and the pathogenesis of AD (Citation14,Citation15). Ruxolitinib cream is a topical formulation of ruxolitinib, a selective inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 (Citation16). In 2 phase 3 randomized studies of identical design in adolescent and adult patients with AD (TRuE-AD1 [NCT03745638], TRuE-AD2 [NCT03745651]), ruxolitinib cream improved AD signs and demonstrated antipruritic action versus vehicle and was well tolerated (Citation17). Here, we present the efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream by anatomic region and signs of AD, with particular focus on head and neck areas, using pooled data from the eight-week, vehicle-controlled period of the TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2 studies.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

The study design, primary outcome, and patient populations for TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2 (identical design) have been previously described (Citation17). TRuE-AD1 (NCT03745638) and TRuE-AD2 (NCT03745651) were phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies of identical design; both studies were registered on November 19, 2018. Eligible patients were aged ≥12 years and had AD for ≥2 years, an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 2 or 3, and AD involvement of 3% to 20% body surface area (BSA), excluding scalp. Patients with AD lesions exclusively on the hands or feet with no prior history of AD involvement in classic areas of presentation, including the face or skin folds, were excluded.

Patients in both studies were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to either of 2 ruxolitinib cream strength regimens (0.75% twice daily [BID], 1.5% BID) or vehicle cream BID for eight weeks of double-blind treatment. Patients were instructed to apply ruxolitinib cream to all affected areas of the body; patients who developed AD lesions in additional (i.e., new) areas were permitted to treat those areas with investigators’ approval, provided that the total treated BSA was ≤20%. Patients were not permitted to use any AD systemic or topical therapies during the washout period and study beyond bland emollients, and rescue treatment was not permitted at any time.

Both studies were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and applicable regulations. The study protocols were approved by all relevant institutional review boards or ethics committees. Before enrollment, all patients provided written informed consent or assent.

Assessments

The extent and severity of AD was assessed using the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), a validated measure to assess BSA involvement of four signs of AD (induration/papulation/edema, erythema, excoriations, and lichenification) across body regions (head/neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs), with higher scores indicative of worse disease severity (range, 0–72) (Citation18). Further details regarding EASI calculations for body regions are included in the Supplement. Least squares mean percentage changes from baseline in EASI anatomic region subscores and signs of AD were assessed at Weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Patients with a baseline EASI head and neck area subscore >0 were included in the subgroup analysis of patients with head and neck involvement. Investigators were instructed to exclude scalp for EASI assessment of the head and neck region. Changes from baseline in the head and neck region at Weeks 2, 4, and 8 were assessed in the population with head and neck involvement at baseline using response thresholds of ≥50%, ≥75%, and ≥90% improvement in EASI head and neck subscores relative to baseline (EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90, respectively). Improvements in EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90 responses using composite EASI scores in the overall population were also assessed for qualitative comparison. Efficacy was also assessed at Weeks 2, 4, and 8 by achievement of IGA treatment success (IGA-TS; IGA score of 0 or 1 and ≥2-grade improvement from baseline) and ≥4-point improvement in itch numerical rating scale score from baseline (NRS4) in the patient population with head and neck involvement at baseline as well as the overall population (for qualitative comparison). Patients documented their worst itch for a 24-h recall period each evening in an electronic diary. For each study visit, itch NRS scores were determined by averaging the 7 daily itch NRS scores before the visit; if ≥4 daily scores were missing, the itch NRS score was classified as missing.

Changes in QoL were assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Citation19) and the children’s version (CDLQI) (Citation20). Both instruments are validated assessments to measure the effect of dermatologic disease on patient QoL, wherein higher scores indicate a greater effect on QoL (range, 0–30). Patients aged ≥16 years and patients aged 12–15 years completed the DLQI and CDLQI assessments, respectively. Both instruments were assessed in patients with head and neck involvement at baseline as well as the overall population. Application site tolerability was also assessed in patients with head and neck involvement at baseline as well as the overall population.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using pooled data from both studies. Efficacy analyses included randomized patients from TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2; patients from one study site in TRuE-AD2 were excluded (n = 41) because of quality issues (Citation17). Safety analyses included all randomized patients from both studies with ≥1 study drug application. Percentage changes from baseline in EASI total scores and subscores were analyzed with a mixed-effect model with repeated measures (MMRM); missing data were handled implicitly by the MMRM model. Change from baseline in DLQI and CDLQI scores were calculated using analysis of covariance with as-observed data. Binary efficacy endpoints were analyzed by logistic regression with statistical significance determined at Week 8; patients with missing postbaseline values were imputed as nonresponders at Weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Results

Patients

Of 1249 randomized patients, 696 (55.7%) had head and neck involvement (excluding scalp) at baseline (0.75% ruxolitinib cream, n = 280; 1.5% ruxolitinib cream, n = 275; vehicle cream, n = 141). Among patients with head and neck involvement, the median age was 30 years (range, 12–77 y) and most patients (80.5%) had moderate baseline disease, defined as an IGA score of 3. The baseline mean (SD) composite EASI score was 9.1 (5.1); the mean (SD) EASI head and neck subscore was 1.2 (0.9). Demographic and patient characteristics in patients with head and neck involvement were similar compared with the overall population (). A total of 1208 patients were evaluable for efficacy in the overall population; 41 patients from one study site in TRuE-AD2 were excluded from efficacy analyses because of quality issues (Citation17). Among patients included in the efficacy analysis, 663 (54.9%) had head and neck involvement at baseline (0.75% ruxolitinib cream, n = 265; 1.5% ruxolitinib cream, n = 262; vehicle cream, n = 136).

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics among patients with head and neck involvement and the overall population.a

Efficacy

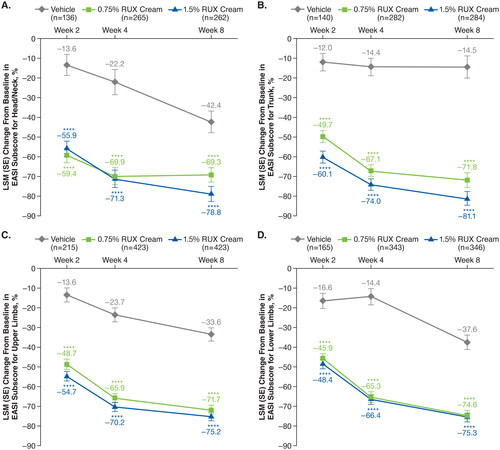

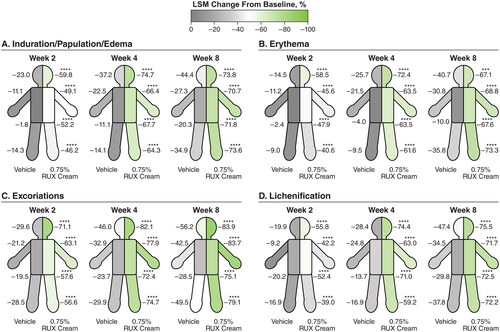

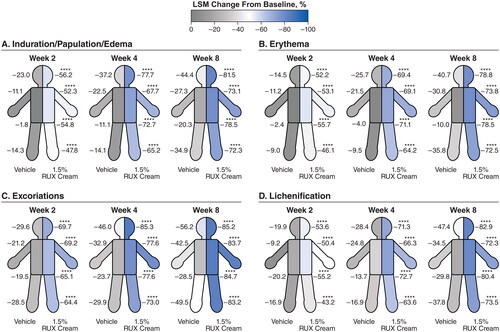

Significant improvements (p < .0001 vs vehicle) in EASI subscore with either strength of ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle were noted as early as two weeks (first assessment) in the head and neck (), trunk (), upper limbs (), and lower limbs (). Improvements for both strengths of ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle continued through Week 8. Within each anatomic region, EASI subscores for induration/papulation/edema, erythema, excoriations, and lichenification were also significantly improved among patients who applied 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle as early as Week 2, with further improvements observed through Week 8 ( and ).

Figure 1. LSM percentage improvements from baseline in total EASI anatomic region subscores for head/neck (A), trunk (B), upper limbs (C), and lower limbs (D) in patients applying 0.75% or 1.5% RUX cream versus vehicle. EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; LSM: least squares mean; RUX: ruxolitinib. ****p < .0001 vs vehicle.

Figure 2. LSM percentage improvements from baseline in EASI anatomic region subscores for induration/papulation/edema (a), erythema (B), excoriations (C), and lichenification (D) in patients applying 0.75% RUX cream versus vehicle. EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; LSM: least squares mean; RUX: ruxolitinib. Data are shown for head/neck, trunk, upper limbs, and lower limbs regions. ***p < .001 vs vehicle; ****p < .0001 vs vehicle.

Figure 3. LSM percentage improvements from baseline in EASI anatomic region subscores for induration/papulation/edema (a), erythema (B), excoriations (C), and lichenification (D) in patients applying 1.5% RUX cream versus vehicle. EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; LSM: least squares mean; RUX: ruxolitinib. Data are shown for head/neck, trunk, upper limbs, and lower limbs regions. ****p < .0001 vs vehicle.

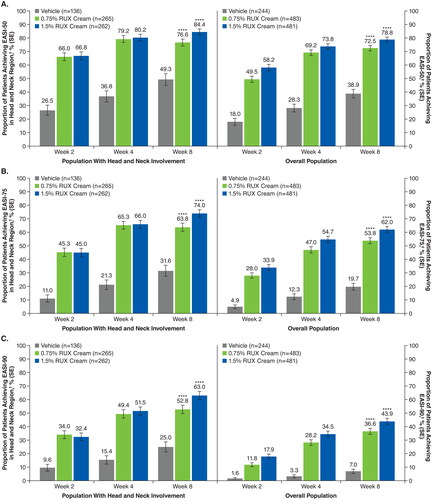

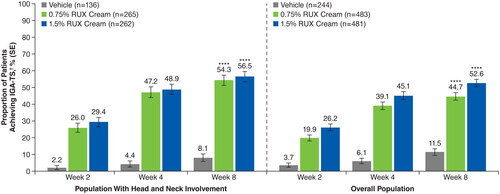

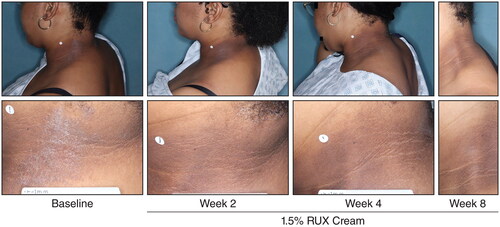

Among patients with baseline head and neck involvement, significantly more patients who applied 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle achieved EASI-50 (76.6% or 84.4% vs 49.3%, respectively), EASI-75 (63.8% or 74.0% vs 31.6%), and EASI-90 (52.8% or 63.0% vs 25.0%) in the head and neck region subscore at Week 8 (p < .0001 for both ruxolitinib cream regimens vs vehicle; ); results were slightly higher versus composite EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90 in the overall population. IGA-TS () and itch NRS4 (Supplemental Figure) were also achieved by significantly more patients who applied 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream compared with vehicle at Week 8 (p < .0001 for both ruxolitinib cream regimens vs vehicle); similar data, albeit slightly lower numerically, were observed in the overall population. Representative photographs of improvements to AD in the head and neck region in a patient who applied 1.5% ruxolitinib cream are shown in .

Figure 4. EASI-50 (a), EASI-75 (B), and EASI-90 (C) based on head and neck region subscore in patients with head and neck involvement and composite score in the overall population. EASI-50: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score from baseline; EASI-75: ≥75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score from baseline; EASI-90: ≥90% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score from baseline; RUX: ruxolitinib. ****p < .0001 vs vehicle. †Includes patients with an EASI head and neck region score >0 at baseline; patients with missing postbaseline values were imputed as nonresponders at Weeks 2, 4, and 8. ‡Includes all patients who were evaluable for efficacy; patients with missing postbaseline values were imputed as nonresponders at Weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Figure 5. IGA-TS in patients with head and neck involvement and the overall population. IGA-TS: Investigator’s Global Assessment treatment success; RUX: ruxolitinib. ****p < .0001 vs vehicle. †Defined as patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 with an improvement of ≥2 points from baseline. Patients with missing postbaseline values were imputed as nonresponders at Weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Figure 6. Representative clinical photographs of AD lesions in the head and neck region. AD: atopic dermatitis; RUX: ruxolitinib.

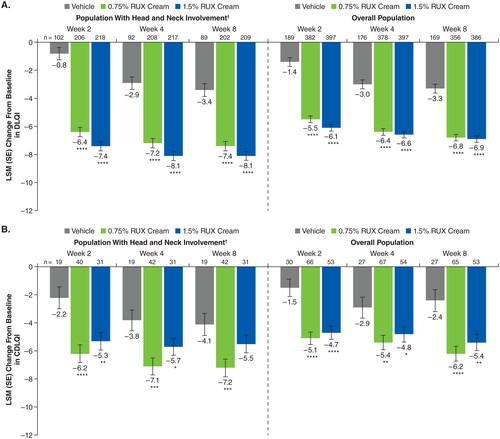

Among patients with head and neck involvement, significant improvements in DLQI were observed at Week 2 and were sustained at Week 8 for both strengths (0.75% and 1.5%) of ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle (least squares mean change from baseline, −7.4 and −8.1 vs −3.4; p < .0001 for both ruxolitinib cream strengths vs vehicle; ). Similar results were observed with CDLQI, although the difference at Week 8 was not statistically significant for 1.5% ruxolitinib cream versus vehicle (). For both DLQI and CDLQI, improvements were slightly higher in patients with head and neck involvement compared with the overall population.

Figure 7. LSM improvements from baseline in DLQI (A) and CDLQI (B) in patients with head and neck involvement and the overall population. CDLQI: children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; LSM: least squares mean; RUX: ruxolitinib. *p < .05 vs vehicle; **p < .01 vs vehicle; ***p < .001 vs vehicle; ****p < .0001 vs vehicle. †Includes patients with an EASI head and neck region score >0 at baseline.

Safety

Application site reactions were infrequent (<3%) in patients who applied ruxolitinib cream regardless of head and neck involvement and were more frequent in patients who applied vehicle (). All types of application site reactions occurred in ≤1% among patients who applied ruxolitinib cream, including the subset with head and neck involvement. Among patients who applied ruxolitinib cream, application site pain was reported in 5 of 555 patients (0.9%) with head and neck involvement and 7 of 999 patients (0.7%) in the overall population. Among patients who applied vehicle, application site pain was reported in 8 of 141 patients (5.7%) and 13 of 250 patients (5.2%) in the population with head and neck involvement and overall population, respectively. Application site reactions with ruxolitinib cream did not result in discontinuations during the eight-week, vehicle-controlled period; these events were nonserious and the majority were grade 1 (i.e., mild).

Table 2. Application site reactions in the population with head and neck involvement and overall populations up to Week 8.

Discussion

In this analysis of pooled data from the TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2 studies, both ruxolitinib cream regimens resulted in significant improvements in all EASI body region subscores (head/neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs) and signs of AD (induration/papulation/edema, erythema, excoriations, lichenification) versus vehicle. Significant improvements were observed at Week 2 (first assessment), with further improvements observed through Week 8. Early reductions in lichenification may be clinically meaningful because this sign can often require longer treatment time for improvement (Citation21), although the improvements at Week 2 observed with ruxolitinib cream should be confirmed in a real-world setting.

Marked improvements in EASI subscales were observed in the head and neck region with ruxolitinib cream, and significantly more patients with baseline head and neck involvement achieved EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90 in the head and neck region versus vehicle. Patients with head and neck involvement at baseline who applied 0.75% and 1.5% ruxolitinib cream had superior (total body) efficacy at Week 8 compared with those who applied vehicle, as demonstrated by IGA-TS and itch NRS4; these results are consistent with the efficacy observed in the overall population. Lower responses may have resulted because of the use of nonresponder imputation, a conservative and widely used statistical approach for evaluating dichotomous efficacy endpoints in clinical trials. It is notable that the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream was numerically greater in patients with head and neck involvement versus the overall population, although a statistical comparison was not done; this comparison is complicated by the inclusion of patients with or without head and neck involvement in the overall population. Facial AD lesions are often painful (Citation22), so the rapid improvement of AD lesions observed in patients with head and neck involvement coupled with the minimal pain observed with topical application at the site of an AD lesion underscores the potential benefit of ruxolitinib cream monotherapy for patients with head and neck involvement.

In addition to improvements in signs and symptoms of AD, patients with head and neck involvement who applied ruxolitinib cream had improvements in QoL, assessed by DLQI and CDLQI, versus those who applied vehicle cream. For reference, a ≥ 4-point improvement and a ≥ 6-point improvement in DLQI and CDLQI, respectively, represent a clinically meaningful change in patients with AD (Citation23,Citation24), and these thresholds were achieved by patients who applied ruxolitinib cream. Furthermore, the QoL improvements observed in this study are consistent with the finding that visible lesions are often reported as most bothersome and the presence of lesions in the head and neck region is associated with a reduction in multiple DLQI domains (Citation4).

Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated at the site of application (including low rates of stinging and burning) in patients with head and neck involvement, with a profile comparable to that seen in the overall population. Moreover, the higher frequency of application site reactions among patients who applied vehicle cream versus ruxolitinib cream could be attributed to worsening of the underlying disease in the absence of an active treatment.

The etiology of head and neck region involvement in patients with AD is not fully understood, and management may be challenging (Citation3,Citation11). Malassezia colonization may contribute to head and neck involvement, although evidence regarding the efficacy of antifungal therapy is conflicting (Citation25,Citation26). Use of nonsteroidal topical therapies (e.g., calcineurin inhibitors and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors) on the face is associated with stinging or burning, and use of topical corticosteroids has a higher risk of cutaneous adverse events (e.g., skin atrophy, redness) (Citation8). New onset or exacerbation of facial dermatitis may also occur with systemic therapy (Citation27). Although there have been published findings describing the safety and efficacy of systemic agents, including oral JAK inhibitors, in combination with topical therapy for AD in the head and neck region (Citation28,Citation29), this is the first analysis to describe rapid, effective, and well-tolerated monotherapy with a topical JAK inhibitor. Results from the double-blind, vehicle-controlled periods of the TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2 studies indicate that ruxolitinib cream is an efficacious and well-tolerated monotherapy regardless of anatomic region involvement, including traditionally difficult-to-treat areas, such as the head and neck. Additionally, published data in the overall population demonstrate that ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated and provided effective disease control over 44 weeks when applied as needed (Citation30).

Our study has several limitations. This was a post hoc analysis and limited to eight weeks of follow-up. Although a large proportion of patients had head and neck involvement at baseline, mean EASI head and neck subscores for this population were relatively low. Longer-term efficacy by anatomic region was not assessed because EASI data were only collected during the double-blind period of the study. In this study, methods used to score efficacy by anatomic region did not distinguish the specific distribution of improvements within each body region; future prospective or observational data may be collected to address this limitation. Although the QoL improvements observed with CDLQI were clinically meaningful, these analyses were limited by a small sample size. The incidence of application site reactions by anatomic region was not evaluated, although the incidence of application site reactions in the population with head and neck involvement was low. Safety analyses included herein were limited to eight weeks, although an analysis of long-term safety and tolerability from TRuE-AD1/TRuE-AD2 demonstrated no new safety signals (Citation30).

In summary, rapid improvements in the extent and signs of AD (induration/papulation/edema, erythema, excoriations, and lichenification) across anatomic regions were observed with ruxolitinib cream monotherapy (without rescue) in this post hoc analysis. In patients with head and neck involvement as well as in the overall population, ruxolitinib cream showed superior improvement of inflammatory skin lesions and itch reduction compared with vehicle as early as two weeks with further improvements through Week 8. Ruxolitinib cream resulted in a clinically meaningful improvement in patient QoL. Application site reactions with ruxolitinib cream monotherapy were infrequent, including in patients with head and neck involvement; there were no discontinuations of ruxolitinib cream due to application site reactions in the eight-week, vehicle-controlled period of the studies. These findings are consistent with results observed in the overall study population (Citation17) and support the use of ruxolitinib cream monotherapy in adolescents and adults with mild to moderate AD regardless of lesion location.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (175.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, investigators, and investigational sites whose participation made the study possible.

Disclosure statement

ELS is an investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron and is a consultant with honorarium for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Forte, Galderma, Incyte Corporation, LEO Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Valeant. RB has served as an advisory board member, consultant, speaker and/or investigator and received honoraria and/or grants from AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena Pharma, Aristea, Asana BioSciences, Bellus Health, Bluefin Biomedicine, Boehringer Ingelheim, CARA, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Evidera, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Inmagene Bio, Kiniksa, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Novan, Pfizer, Ralexar, RAPT Therapeutics, Regeneron, Respivant, Sanofi-Genzyme, Sienna, Target RWE, and Vyne Therapeutics and is an employee and shareholder of Innovaderm Research. ZCCF has served as a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, the National Eczema Association, AbbVie, Beiersdorf, Incyte Corporation, and Pfizer; has received research grants from Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, and Vanda for work related to atopic dermatitis and Menlo Therapeutics for work related to prurigo nodularis; and has received honoraria for continuing medical education work in atopic dermatitis sponsored by education grants from Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. HK, DS, and HR are employees and shareholders of Incyte Corporation. LFSG has served as an investigator, advisor, and/or speaker for AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte Corporation, Ortho Derm, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi.

Data availability statement

Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA) is committed to data sharing that advances science and medicine while protecting patient privacy. Qualified external scientific researchers may request anonymized datasets owned by Incyte for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. Researchers may request anonymized datasets from any interventional study (except phase 1 studies) for which the product and indication have been approved on or after 1 January 2020 in at least one major market (e.g., US, EU, JPN). Data will be available for request after the primary publication or two years after the study has ended. Information on Incyte’s clinical trial data sharing policy and instructions for submitting clinical trial data requests are available at: https://www.incyte.com/Portals/0/Assets/Compliance%20and%20Transparency/clinical-trial-data-sharing.pdf?ver=2020-05-21-132838-960.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):1–10. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1.

- Silverberg JI, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, et al. Distribution of atopic dermatitis lesions in United States adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(7):1341–1348. doi:10.1111/jdv.15574.

- Maarouf M, Saberian C, Lio PA, et al. Head-and-neck dermatitis: diagnostic difficulties and management pearls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(6):748–753. doi:10.1111/pde.13642.

- Lio PA, Wollenberg A, Thyssen JP, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis lesion location on quality of life in adult patients in a real-world study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(10):943–948. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5422.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson B, Abuabara K, et al. Prevalence and burden of atopic dermatitis involving the head, neck, face, and hand: a cross sectional study from the TARGET-DERM AD cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):519–528. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.052.

- Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, et al. Extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2018;45(2):150–157. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14116.

- Vittrup I, Krogh NS, Larsen HHP, et al. A nationwide 104 weeks real-world study of dupilumab in adults with atopic dermatitis: ineffectiveness in head-and-neck dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(5):1046–1055. doi:10.1111/jdv.18849.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(1):e1–e20. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.029.

- Pao-Ling Lin C, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1451–1453. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.054.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(4):340–357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514.

- Jaros J, Hendricks AJ, Shi VY, et al. A practical approach to recalcitrant face and neck dermatitis in atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2020;31(3):169–177. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000590.

- Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM, et al. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal (“steroid addiction”) in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(3):541–549.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.024.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zach S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717–2744. doi:10.1111/jdv.16892.

- Bao L, Zhang H, Chan LS. The involvement of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis. JAKSTAT. 2013;2(3):e24137. doi:10.4161/jkst.24137.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171(1):217.e13–228.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.006.

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115(15):3109–3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):863–872. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.085.

- Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11–18. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942–949. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x.

- Glazenburg EJ, Mulder PG, Oranje AP. A statistical model to predict the reduction of lichenification in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):294–297. doi:10.2340/00015555-1881.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Pain is a common and burdensome symptom of atopic dermatitis in United States adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(8):2699.e7–2706.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.055.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33. doi:10.1159/000365390.

- Simpson EL, de Bruin-Weller M, Eckert L, et al. Responder threshold for Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) in adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9(4):799–805. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00333-2.

- Glatz M, Bosshard PP, Hoetzenecker W, et al. The role of Malassezia spp. In atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med. 2015;4(6):1217–1228. doi:10.3390/jcm4061217.

- He D, Han Y, Wu H, et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis using topical antifungal drugs: a meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(12):e15930. doi:10.1111/dth.15930.

- Soria A, Du-Thanh A, Seneschal J, et al. Development or exacerbation of head and neck dermatitis in patients treated for atopic dermatitis with dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(11):1312–1315. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2613.

- Alexis A, de Bruin-Weller M, Weidinger S, et al. Rapidity of improvement in signs/symptoms of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis by body region with abrocitinib in the phase 3 JADE COMPARE study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(3):771–785. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00694-1.

- Hagino T, Saeki H, Fujimoto E, et al. The differential effects of upadacitinib treatment on skin rashes of four anatomical sites in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34(1):2212095. doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2212095.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(5):1008–1016. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.060.