Abstract

Background

Understanding the patient journey is important to optimize care for patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) and overcome challenges in diagnosis and management.

Objective

To explore patient and caregiver perspectives regarding their experience with AD.

Methods

Patients and caregivers of patients with AD completed a pre-meeting survey and were invited to join an advisory board meeting in their country (China, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan and Lebanon) to discuss the survey results. Data were analyzed descriptively.

Results

The survey included 31 participants (patients and caregivers) from Hong Kong (n = 7), China (n = 7), Ireland (n = 6), Japan (n = 6) and Lebanon (n = 5). The most challenging factors in the AD journey were management of symptoms before a confirmed diagnosis (68%), sudden recurrence of flares or worsening of symptoms (68%) and lifestyle changes (52%). In terms of overall AD management, 35% of participants indicated that AD was managed well, 23% had a clear treatment plan and 19% were generally satisfied with disease management. A collaborative relationship with healthcare professionals was favored.

Conclusion

A holistic assessment of AD includes understanding patient and caregiver preferences, needs, experiences and disease perceptions. Addressing the identified gaps may improve the management of AD.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disease that is characterized by dry skin; acute, subacute or chronic pruritic eczematous lesions; and compromised barrier function (Citation1–3). The prevalence of AD varies worldwide (Citation4), affecting 15% to 30% and 2% to 10% of the pediatric and adult populations, respectively (Citation5). AD often manifests during the first year of life (early onset); however, it may manifest at any age (Citation6–8).

Although the goal of treatment in AD is to reduce symptoms and prevent exacerbation, treatments often fail to maintain disease control. This can be frustrating for patients and caregivers (Citation9,Citation10). Moreover, treatment adherence may be affected by factors including cost, the incidence of adverse effects and comprehension of correct use and convenience (Citation9,Citation11,Citation12). In addition, access to specialized services to ensure the appropriate management of more severe cases is often limited (Citation13–17). The burden of AD on patients and their caregivers’ quality of life (QoL) is substantial but often underestimated and not fully understood. In previous studies, patients with AD and caregivers of patients with AD have expressed that they must play a more active role in communicating the physical and emotional impact of AD and that there needs to be greater emphasis on shared decision-making when considering potential treatment options (Citation18,Citation19). AD affects the physical and mental health of patients because of its relapsing-remitting nature, with clinical features including itching, inflammation, skin pain and secondary complications such as sleep disturbance and infections (Citation3,Citation20,Citation21). Such symptoms may also lead to emotional or behavioral changes such as irritability, embarrassment, anxiety, depression and/or suicidality (Citation21–23). Embarrassment due to skin discoloration, lesions, and itch often have an impact on social functioning (Citation21,Citation24,Citation25). In addition, AD is often associated with a substantial economic burden driven by the direct costs of prescriptions, over-the-counter treatments, and healthcare practitioner visits as well as indirect costs, including absenteeism and lost productivity (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26).

Information about the patient journey and the perspectives of patients and caregivers about burden of the disease is sparse. Such insights may improve patient care and disease outcomes. Herein we discuss the perspectives of patients and caregivers of patients with AD regarding their experience with the disease, information needs at each stage of the AD journey and their expectations around decision-making and treatment choices for the effective management of AD.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Pfizer Inc. and CGI Health, a healthcare communications agency, worked with patient advocacy groups to recruit patients and caregivers. Advisory board meetings were conducted virtually with participants from Hong Kong, China, Ireland, Japan and Lebanon. Participants included patients and caregivers of patients with AD who had internet access and were willing to participate in a 2-h virtual meeting. Participants were identified and contacted by GCI Health in partnership with Pfizer Inc., and this process was facilitated in the respective countries by the Lebanese Society of Dermatology, the China Atopic Dermatitis Family, Allergy-wo-kangaeru hahanokai in Japan, the Irish Skin Foundation, the Hong Kong Allergy Association and the Hong Kong Asthma Society. Countries were selected based on local regulations and compliance requirements for patient advisory boards, as well as feasibility assessments with patient advocacy groups who were interested in assisting with patient and caregiver recruitment.

Participant criteria that were preferred included: patients and/or caregivers of patients with mild-to-moderate AD with experience using topical prescriptions, who were responsible for making decisions on AD management products, had previously sought out or were currently seeking doctors’ advice for AD management; and patients who had a longer duration of disease. However, these were not requirements for participation. Patients and caregivers were not permitted to participate if they worked for a competitor industry or were a healthcare professional. There was no limit on age for either patients or caregivers, unless local regulations precluded the participation of minors. Minors required parental approval to participate. Where an adult accompanied a minor, the adult was not considered as a recruited caregiver.

After identifying suitable patients and caregivers through the regional patient network, CGI Health contacted eligible participants for further screening. Screened patients and caregivers confirmed their participation in the advisory board with signed contracts.

A pre-meeting survey developed by Pfizer Inc. and GCI health was distributed to the participants before the meeting (see Supplementary Materials). The survey focused on four areas: experience living with AD, current AD management, perspectives on making decisions on and living with AD and expectations regarding AD management in the future. Some participants did not provide a response for every question. Patients were allowed as much time as needed from recruitment until the day of the advisory board to complete their surveys; this typically ranged from one to three weeks. All individuals who completed the survey were invited to join the advisory board meeting. Key themes identified from the pre-meeting survey were used to guide the group discussions. These group discussions included sharing personal experiences during each stage of the AD management journey (pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, treatment initiation, treatment adjustment, resolution and maintenance, flares, ongoing considerations), decision making with regards to management of AD and expectations for the treatment and future management of AD. The meetings were sponsored by Pfizer Inc. and were independently moderated by GCI Health. Meetings were conducted between December 2020 and June 2021 in the most commonly used language in each geographical area depending on the geographical location.

Ethical approval

The survey complied with the local ethical guidelines of each participating country and all meeting material met local regulations. All participants provided electronic informed consent.

Statistical analysis

All information collected from the survey and the advisory board meetings was presented descriptively, with no formal statistical analysis performed.

Results

The survey was administered between December 2020 and June 2021.

Baseline characteristics

Age range and duration of AD

The survey included 31 participants (patients and caregivers) from Hong Kong (n = 7), China (n = 7), Ireland (n = 6), Japan (n = 6) and Lebanon (n = 5). The ranges of patient ages were 10–46 years of age for Ireland, 3–40 years of age for Lebanon, 10–49 years of age for Japan, 14–66 years of age for Hong Kong and 4–34 years of age for China; not all participants indicated age. Duration of AD was ≤10 years for 55% of patients (n = 17) and >10 years for 45% of patients (n = 14) (). In Lebanon, 100% of patients (n = 5) had a disease duration of <10 years, and 50% of patients (n = 3) from Ireland had a disease duration of >20 years ().

Table 1. Age range and duration of disease.

Impact of AD on QoL

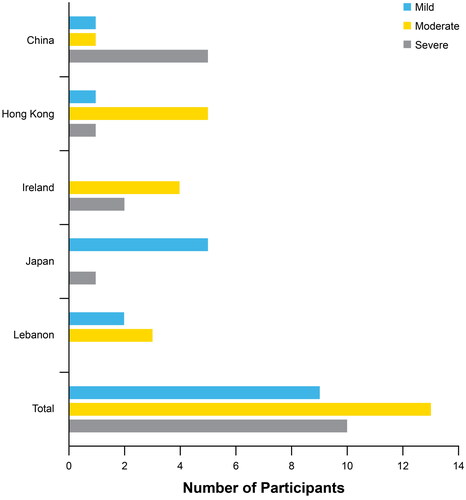

Patients and caregivers were asked to rate the impact of AD on their own QoL, or that of the person they were caring for, as mild, moderate or severe when skin-related symptoms were at their worst over the last 12 months (mild impact was defined as AD having a minimal impact or not causing frequent disruption to QoL, moderate impact was defined as AD being associated with a clear disruption to QoL and a severe impact was defined as AD causing a significant disruption to QoL). Out of 31 participants, the majority indicated that their QoL and/or QoL of their family members was moderately (42%) or severely (29%) affected (); 71% (n = 5) of participants from China reported their QoL and/or the lives of their family members as severely affected. All of the participants (n = 5) from Lebanon reported QoL as mildly/moderately affected, and 83% (n = 5) of participants from Japan reported their QoL as mildly affected.

Figure 1. Impact of AD on patient QoL (classified as mild,a moderateb or severec) as per the participants in each region when their skin-related symptoms were at their worst over the past 12 months. aMild: The condition has minimal impact or does not cause frequent disruption to life and/or the lives of family members (e.g., rarely disturbed sleep, no or low impact on work/school performance). bModerate: The condition clearly causes disruption to life and/or the lives of family members (e.g., sometimes disturbed sleep, moderate impact on work/school performance). cSevere: The condition causes significant disruption to life and/or the lives of family members (e.g., frequently disturbed sleep, high impact on work/school performance). AD: atopic dermatitis; QoL: quality of life.

AD has influenced our lives in all respects. We can’t sleep well; we can’t be in a good mood, and we have no appetite during attacks. Our kid is suffering [from] skin lesions; he is so afraid of having a bath as it really hurts. He can’t focus on study[ing] as it itches all the way. ꟷ Caregiver from China

Patients and caregivers noted that the disease seemed to affect every aspect of their lives, with symptoms such as itch, pain and swelling often becoming unbearable. One patient from Ireland said that the itch was so difficult to deal with, he would prefer to blow hot air from a hairdryer on his skin and deal with that pain instead. Another patient from Ireland left his family and job to move to a warmer country because he considered this the only way to manage his condition. Lack of sleep was also identified as a common problem. Participants complained that they woke up multiple times through the night, which affected their overall mood and caused them to feel tired.

I never sleep through the night. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

In terms of their mental health, participants reported feelings of depression and anxiety; some had a fear that there would never be a treatment that would work for them and that their symptoms might be with them forever. It was hard for parents/caregivers to see their loved ones suffering.

I was depressed. ꟷ Patient in China

It was very hard to see my kid suffering. ꟷ Caregiver in Lebanon

Most participants highlighted the stigmatization associated with AD and the resultant social isolation. Patients were embarrassed when their skin itched in public, causing them to constantly scratch. They often felt distressed due to people staring. These factors affected school and work as well as their social lives.

My peers in school bullied me because I looked different from them. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

Could not go to school. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Skin-related symptoms

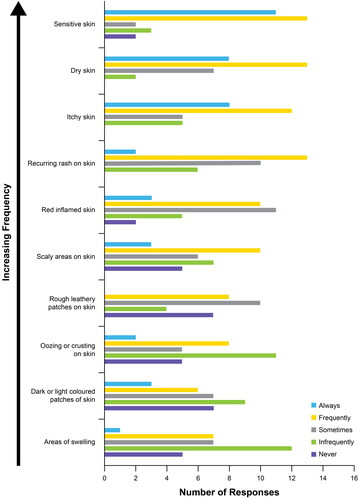

Participants were asked to rate the incidence of their skin-related symptoms on a scale of 1–5 (1 indicating ‘never’ to 5 indicating ‘always’) over the past six months; 35% (n = 11), 29% (n = 9), and 26% (n = 8) of participants reported always experiencing sensitive, dry, and itchy skin, respectively (). Furthermore, ≥25% of participants reported skin that was frequently dry, itchy, scaly or red (inflamed) with recurring rashes, rough leathery patches, oozing or crusting and sensitivity. The persistence of symptoms despite treatment is often disheartening to patients and caregivers. Two patients from Ireland said that their skin was continuously affected by AD-related symptoms negatively influencing their daily activities.

Figure 2. Patient experience with skin-related AD symptoms over the past six months according to frequency. Disturbance was rated on a scale of 1–5, where 1 indicates ‘never,’ 2 indicates ‘infrequently,’ 3 indicates ‘sometimes,’ 4 indicates ‘frequently’ and 5 indicates ‘always.’ ‘Increasing frequency’ as indicated on the y-axis was determined by the sum of the number of ‘always’ and ‘frequently’ endorsements by participants. AD: atopic dermatitis.

Challenges during the AD journey

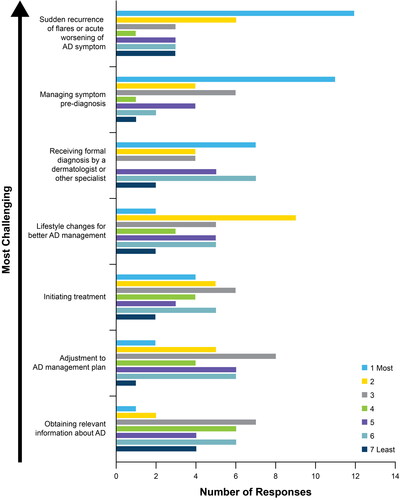

When asked to rate the most challenging stages of their AD journey on a scale of 1–7 (1 indicating ‘most challenging’ and 7 indicating ‘least challenging’), 68%, 68% and 52% of participants reported managing symptoms before a confirmed AD diagnosis, the sudden recurrence of flares or acute worsening of AD symptoms and lifestyle changes for the better management of AD, respectively, as the most challenging ().

Figure 3. Patient journey with AD: challenges with different stages of the AD journey according to the participants ranked from most challenging to least challenging. Disturbance was rated on a scale of 1–7, where 1 indicates ‘most challenging’ and 7 indicates ‘least challenging.’ AD: atopic dermatitis.

Symptoms were often managed unsuccessfully for extended periods because of an initial misdiagnosis before receiving an accurate diagnosis. One participant from Japan shared that it had taken 10 years to diagnose their AD and their symptoms had worsened significantly during this time. This was a period filled with trial-and-error management. Moreover, treatments prescribed for a misdiagnosis other than AD were often ineffective, causing patients to feel anxious and frustrated.

Before building the accurate diagnosis, the treatments prescribed by our pediatrician were not helping. ꟷ Caregiver in Lebanon

I changed 5 pediatricians before being referred to a dermatologist who made the accurate diagnosis and prescribed the right treatment. ꟷ Caregiver in Lebanon

Once diagnosed, patients and caregivers struggled with optimal management. Participants reported that additional information on basic skin care at the time of diagnosis would have helped with disease management. Some of the participants communicated that they lacked confidence in healthcare professionals because of their own prior negative experiences within the healthcare system; access to health care professionals with expertise in AD management was also considered limited.

Participants discussed the effect of flares on their lives. Flares would often come without warning and resulted in patients feeling stressed and fatigued, with severe flares resulting in repeated hospital admissions. Some participants felt that they lacked effective treatment to manage these flares. Not only did this have cost implications; it also resulted in loss of workdays.

The older my son gets, the more his rash intensifies every time the season changes. ꟷ Caregiver in Lebanon

I want preventative effective treatment to be used on a daily basis that would lower the severity of AD if flared. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

Current AD management plan

Most participants (87% [n = 27]) currently reported using ointments and creams (both over-the-counter [OTC] and prescription) for their AD, more than half of participants (58% [n = 18]) used oral medication, 32% (n = 10) used injection therapy, 29% (n = 9) used phototherapy and 26% (n = 8) used traditional Chinese medicine (7 of the 8 participants using traditional Chinese medicine were from Hong Kong and Japan). Ointments and creams used included topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, PDE-4 inhibitors, and emollients. Most participants used more than 1 type of treatment; 45% of participants (n = 14) reported lifestyle changes including dietary modifications, spending more time outdoors in sunlight (including moving to a warmer climate for large periods of the year) and ensuring their skin remained moist (keeping humidity levels high indoors).

Safety and efficacy were ranked as the most important aspects of the treatment options used, in addition to perceptions regarding convenience and how different types of treatments fit into their daily lives.

Injections are very effective, but it is hard to inject yourself. ꟷ Patient in Japan

I would like to avoid injections, they are scary. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Sticky ointment is a problem when going to work, as it stains clothes and underwear. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Topical ointment would be safer and convenient. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

If it’s about a lifestyle change, I would like to have a try… like converting my diet to vegetarian… it seems healthy as a whole for physical health. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

If there is an oral medication that will work for a week that would be best. ꟷ Patient from Japan

If there are meds that can be applied in any part of the body, something like a mist. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Although many participants indicated that they preferred oral and topical treatment options because of convenience, 1 participant noted that any effective route of administration would be acceptable.

Route of administration is irrelevant if it worked. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

One patient from Japan was extremely dissatisfied and felt that perhaps there were no options that would fully control their AD-related symptoms.

Maybe no suitable medications for myself. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Participants emphasized that often a lack of knowledge on the correct use of medicines may have influenced the level of satisfaction with certain treatments.

No explanation on correct usage or about medication or how to care. ꟷ Caregiver in Japan

What I learned from visiting dermatologists was that even if you use the same medication (steroids), how you use it can be different depending on the doctor. I used it wrongly and suffered from side effects. I feel if all dermatologists can properly direct patients about the usage according to the guideline, AD patients will be able to feel safe about undergoing treatment. ꟷ Patient in Japan

For so many years, not a single doctor has ever told us to pay attention to skin barrier repair, moisturizing etc. ꟷ Patient in China

When I know that my children need skincare products, I always buy a large amount of them online for my children during shopping festivals. ꟷ Caregiver in China

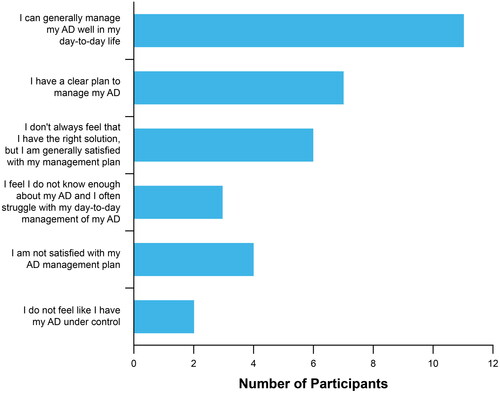

Overall, 35% of participants agreed that they were generally able to manage AD well in their day-to-day life and 23% had a clear plan to manage their AD, while 19% did not always feel that they had the right solution but were generally satisfied with their management plan (). However, 6% of participants agreed that they did not have their AD under control, 13% were not satisfied with their AD management plan and 10% felt they did not know enough about their AD and often struggled with its day-to-day management ().

Figure 4. Patient journey with AD: satisfaction with overall AD management. Participants indicated which statement(s) best matched their level of satisfaction with overall AD management. AD: atopic dermatitis.

I hope there would be a new AD medication available. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

I don’t want any preventative treatment anymore; I just want to cure my AD. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

I understand that I always need to use lotions and creams for moisturizing but once triggered, my AD intensifies, regardless of the options used ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

I am tired of applying creams and ointments, I want a permanent solution. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

Management of flares and worsening of AD symptoms

For managing flares or worsening AD symptoms, 58% of participants reported seeing a healthcare practitioner right away (n = 9) or within a few days (n = 10), 26% waited a few weeks (n = 5) or until their next scheduled healthcare practitioner visit (n = 3) and 6% self-managed and rarely visited a healthcare practitioner for flares (n = 2). Of participants in China, 100% reported seeing a healthcare practitioner right away or within few days of experiencing a flare or worsening symptoms.

I will go to the hospital directly when the disease is about to attack. ꟷ Patient in China

Most of the participants included in this survey had a long-standing history of AD, and some participants were confident that they had sufficient knowledge to handle the worsening of symptoms or flares on their own. During the group discussions, many of the participants indicated that access to certain healthcare professionals, especially dermatologists, was limited. Thus, the delay in seeking assistance from healthcare providers may be partly attributed to this lack of availability.

I usually will try some accessible or convenient ways on my own to settle different AD situations…If that’s not effective in 2–3 days or situation get worse, I will go for healthcare professional for consultations e.g., specialists or dermatologists…But they are sometimes too busy and hard to be booked for consultations. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

Facetime with dermatologists is limited. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

It’s great when you get to a dermatologist, but it can be a long wait. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

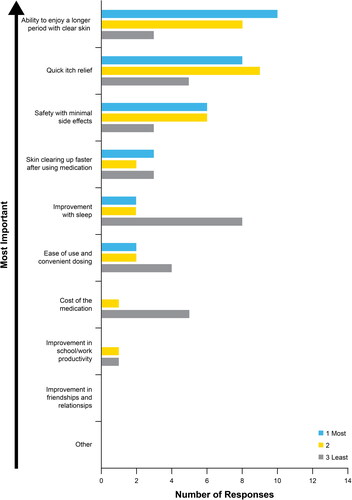

Choice of treatment

The ability to enjoy a longer period with clear skin, quick itch relief and safety with minimal side effects were the most important factors for choosing an AD treatment as evident from the survey () and the subsequent advisory board meetings.

Figure 5. Factors considered important for decision making regarding the choice of treatment for the management of AD when given a choice of two treatments by a healthcare professional. The three most important factors were ranked, where 1 indicates ‘most important’ and 3 indicates ‘least important.’ AD: atopic dermatitis.

I want to have a long-term solution that works for me. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

Would like it to be like a blood pressure tablet, taken and then not have to worry. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

Will only use new medications if they are for the long-term, not willing to try if this is not the case. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

Itching affects physically and mentally. It’s better for patients if it can stop as quick as possible. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Ideally meds should work immediately. ꟷ Patient in Japan

My biggest concern is safety. ꟷ Patient in China

I received an injection, itching subsided the next day, but I suffered side effects, my eyes were swollen, and my face reddened. ꟷ Patient in Japan

Steroid phobia was extensively discussed and was expressed as a concern within each group from all the countries represented in the survey despite the efficacy of steroid treatment.

I started to use steroids with the same amount of faith as jumping off a cliff. ꟷ Patient in Japan

I would not take any medication or ointment that contains steroids. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

I totally agree that steroids only accounts for short term but not a complete cure of AD. It will lead to thinner skin, and after that you will be easier to cause more serious hurts after scratch. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

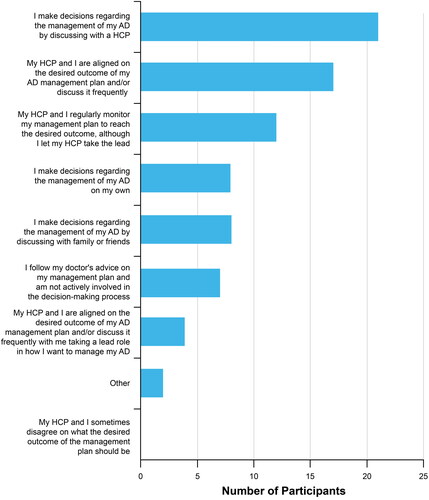

Involvement with AD management

Types of involvement in AD management included those with collaborative decision making with their healthcare provider (48%), scenarios with their healthcare provider taking the lead (24%) and those with patient-led decision making (15%) ().

Figure 6. Patient involvement in the management of their AD. AD: atopic dermatitis; HCP: healthcare professional.

Many participants felt being involved in AD management gave them a feeling of control. Patients and caregivers who indicated that they collaborated with their healthcare provider and those who allowed healthcare providers to take the lead in managing their AD emphasized the importance of trust, communication and transparency in these relationships.

It took me a long time to meet a doctor I can trust…lots of doctor shopping. ꟷ Patient in Japan

I was asked ‘How do you feel?’ by the dermatologist and it was the first time anyone has asked me that, rather than just asking about my skin. This was a great step forward for me. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

Because I totally trust my current doctor, if he/she recommends that a medicine is good then I would like to choose that medicine. ꟷ Patient in Japan

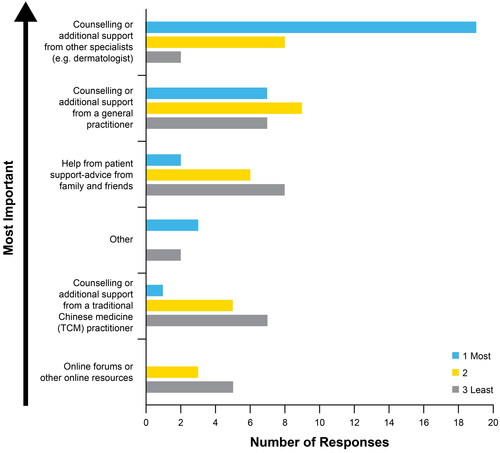

Future AD management

Of factors that would influence their management of AD in the future, 61% of participants ranked counseling or additional support from other specialist (e.g., dermatologists) as the most important factor, followed by counseling or additional support from a GP (19%) (). Overall, patients and caregivers expressed that they trusted their specialists and GPs when making choices.

Figure 7. Importance of different factors to participants when selecting future AD management. The three top influences were ranked on a scale of 1–3, where 1 indicates ‘most important’ and 3 indicates ‘least important.’

I don’t change my routine treatment without consulting with my doctor. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

Information on AD

Sources for obtaining information on AD management

Thirty-two percent of participants ranked obtaining relevant information on AD as 1 of the 3 most challenging factors in the AD journey. Although it was important for participants to find reliable sources of information, misinformation was a problem. One participant from Japan mentioned that there was information everywhere encouraging AD patients to stop taking steroids, and 1 patient from Hong Kong had received conflicting advice from different sources.

When asked where they obtain information on the management of AD as part of a multi-response question, 61% got information from their dermatologist, 35% used social media, 10% referred to personal anecdotes shared by other patients and 10% obtained the necessary details from their GP or community clinics.

I would like to seek more advice from doctor and understand more on the disease and treatment alternatives. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

First, I ask my parents what to do and they would tell me to consult with my dermatologist. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

I never ask the pharmacist about treatment options; I trust my dermatologist. ꟷ Patient in Lebanon

Although participants in most countries reported dermatologists as the most common source of information, 71% of participants from Hong Kong reported social media to be one of their most common sources. Often specialized services may be difficult to access, which may have contributed the increased use of social media as a source in Hong Kong. This may differ depending on the country or region in which the participant lives.

Social media and online resources are the most accessible and convenient channels. Some posts from patient group’s Facebook Page and in-depth interviews by a dermatologist on YouTube are more trustworthy. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

A relatively smaller proportion of participants reported using resources shared by their patient support groups (16%), a different specialist (16%), healthcare publications (13%), pediatric physician (10%), advice from family/friends who did not have direct experience with AD (6%) or traditional media (3%); in Lebanon, 50% used personal anecdotes of other patients, emphasizing the importance of patient associations.

In the patient group, you can learn enough information when people talk and communicate freely. ꟷ Patient in China

Seminars could be helpful where you can meet with people who experience what you experience. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

As quite a few of my family members are also AD patients, I am familiar with different situations of AD and I will always go to them first for [advice]. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

Half of my class in secondary school were also AD patients. We naturally exchange information with each other. ꟷ Patient in Hong Kong

Sources of new information on AD management

For new AD management information, 58% discussed it with their specialist, 35% conducted online searches, 16% would reach out to their support group and 3% indicated changing their current plan before they are able to meet their healthcare practitioner.

When I receive new information, I text my doctor and ask for his opinion. ꟷ Patient in Ireland

Most participants from all participating countries (except China) discussed new information with their specialist for more advice.

Doctors in general provincial cities seldom attend such international conferences and are unable to learn new drugs and treatment means. ꟷ Patient in China

In Ireland, 67% of participants conducted an online search for more information, and 57% of participants from China reached out to their support group for more advice.

In fact, our doctor here has done a very good job, as he has helped us create a patient group where we can present our questions in daily life, and he will check and give us answers on a regular basis. ꟷ Patient in China

Discussion

The early stages of AD patient journey may be the most difficult, largely driven by challenges with misdiagnosis and subsequent delays in appropriate treatment. With the typical features of AD (including pruritus, erythema, flaking and scaling) being common to many other skin conditions and the lack of a definitive laboratory test, making a definitive diagnosis can be difficult (Citation13,Citation26,Citation27). In addition, the symptoms and distribution of AD differs depending on the patient’s age at presentation (Citation26). The time between symptom onset and correct diagnosis frustrates patients and caregivers and contributes to the potential for disease progression and side effects secondary to inappropriate drug therapy (Citation28). Increased awareness and education on all the spectrums of AD and its distinguishing features among healthcare professionals may help remedy these challenges (Citation13).

The results of the survey, highlighting the failure of current treatments to achieve lasting disease control, suggest an unmet need for improved options. Patients are looking for treatments that achieve quick itch relief and longer periods of clear skin. Although efficacy was important to patients, safety was also a crucial factor when considering different treatment options. When making decisions regarding their future treatment options, patients emphasized their trust in their dermatologists and GPs in helping them to achieve these goals. Most participants indicated that counseling or additional support from specialists and GPs would be the most important factor influencing their decisions about future treatments.

Most participants in the survey indicated that decisions regarding the management of AD were made by means of joint discussions with a healthcare practitioner. However, the success of this collaboration can be impacted by a mismatch in the perception of disease severity between patient and healthcare practitioner (Citation19). Patients have previously reported that the impact of AD on their physical and emotional well-being can be underestimated by healthcare practitioners (Citation19). The symptoms of AD described by patients in social media were found to be discordant from those used in scientific literature, which further reinforces the potential differences between the respective perceptions of AD-related symptoms by patients and healthcare professionals (Citation29).

Acceptance and recognition of the physical, emotional, and psychological burden associated with AD is important to patients. A care plan tailored to the patient’s preferences and needs in combination with adequate education can assist in optimizing adherence and subsequently the patient’s health-related outcomes (Citation12,Citation19,Citation30,Citation31). Improved communication between the patient and the various healthcare professionals involved in the management of AD throughout its different stages as well as access to reliable sources of information and appropriate care may be vital to this process (Citation31,Citation32). To achieve this, it is important that patients feel understood and heard (Citation33). A trusting relationship helps ensure good communication and confidence in the decisions made (Citation19,Citation34).

As indicated during the survey and group discussions, dermatologists and general practitioners are both valued care providers and sources of information; however, access to specialized services (e.g., a dermatologist) is often limited. This can be due to the patient’s geographical location and their socioeconomic circumstances (Citation13–17). In addition, the public healthcare system in each country and, in some cases, different regions within a country have specific regulations that need to be followed to access certain levels of care and may result in prolonged wait times for a dermatologist (Citation13,Citation14). Because of difficulties in accessing specialized care, patients often seek assistance from other healthcare professionals throughout the different stages of AD; however, these professionals may not have sufficient expertise to manage the more complex cases of AD (Citation35–37). Access to a dermatologist may be important for patients with chronic moderate-to-severe AD, flares, and refractory AD (Citation36,Citation38–40). For all patients, follow-up visits to adjust therapy when needed may help to achieve and maintain disease control (Citation36,Citation38,Citation39). In addition, as indicated during the survey, patients may turn to social media as a source of information which may not be correct or relevant to the patient; this may occur more frequently when access to specialized care is limited (Citation41).

The small sample size and lack of response by some participants limited the interpretation and generalizability of the study results, as there is a large patient inter-variability. No statistical analyses were possible with the small dataset, and the data are subsequently presented as descriptive summaries with quotes from participant discussions. Studies with a larger number of participants are recommended to understand more nuanced perspectives of AD treatment and impact based on age and geographical location. Furthermore, aggregation of patient and caregiver data precludes any comparison between patient and caregiver perspectives, which may differ in priorities and sentiment. Finally, patients’ and caregivers’ opinions of disease severity are not the recommended way to perform a formal assessment of the effect of AD on patient QoL. While the focus of this study was to give personal context to participant perspectives, future studies using established QoL measurement tools are recommended.

A holistic assessment of AD includes insights gained from patients’ and caregivers experience with AD, their needs at each stage of the journey, their expectations around decision-making and treatment choices. Addressing the identified gaps including delays in accurate diagnosis, limited effective treatment options appropriate for long-term management and inadequate access to specialized services may help improve the treatment and management of patients with AD.

Author contributions

All authors prepared and revised the draft manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (158.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Editorial and medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by David Gibson, PhD, CMPP, and Chantell Hayward, PharmD, at ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA, and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(9):1298–1304. doi: 10.7326/M22-1460).

Disclosure statement

Steven R. Feldman has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Accordant, Almirall, Arcutis, Arena, Argenx, Alovtech, Amgen, Biocon, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Caremark, Celgene, Dermavant, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline/Stiefel, Eurofins, Forte, Galderma, Helsinn, Informa, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Menlo, Merck & Co., Micreos, Mylan, National Biological Corporation, National Psoriasis Foundation, Novan, Novartis, Ono, Ortho Dermatology, Qurient, Regeneron, Samsung, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Tealdoc, UCB, UpToDate, and vTv Therapeutics. He is the founder and part owner of Causa Research and owns stock in Sensal Health. Alson Wai Ming Chan has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Pfizer Inc., Abbott, AbbVie, ALK, Novartis, Sanofi and Stallergenes Greer. Alfred Ammoury has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis and Sanofi. Jianzhong Zhang has received speaking and/or consulting support from Pfizer Inc. Akio Tanaka has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Maruho, Otsuka Pharma, Sanofi, and Torii Pharma. XingXiang Shi has no conflict of interest to declare. Amy Cha and Helen Tran are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

References

- Brown SJ. Atopic eczema. Clin Med. 2016;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-1-66.

- Fleming P, Yang YB, Lynde C, et al. Diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(4):626–635. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.04.190449.

- Maliyar K, Sibbald C, Pope E, et al. Diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31(12):538–550. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000547414.38888.8d.

- Urban K, Chu S, Giesey RL, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of atopic dermatitis in 195 countries and territories: an ecological study from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. JAAD Int. 2021;2:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2020.10.002.

- Luger TA, Hebert AA, Zaenglein AL, et al. Subgroup analysis of crisaborole for mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in children aged 2 to < 18 years. Pediatr Drugs. 2022;24(2):175–183. doi: 10.1007/s40272-021-00490-y.

- Baron SE, Cohen SN, Archer CB. Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of atopic eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(Suppl 1):7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04336.x.

- Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(Suppl 2):52. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0281-6.

- Al-Naqeeb J, Danner S, Fagnan LJ, et al. The burden of childhood atopic dermatitis in the primary care setting: a report from the Meta-LARC consortium. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(2):191–200. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.02.180225.

- Johnson BB, Franco AI, Beck LA, et al. Treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:181–192. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S163814.

- Nowicki RJ, Trzeciak M, Kaczmarski M, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Interdisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society, Polish Society of Allergology, Polish Pediatric Society and Polish Society of Family Medicine. Part I. Prophylaxis, topical treatment and phototherapy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(1):1–10. doi: 10.5114/ada.2020.93423.

- Tier HL, Balogh EA, Bashyam AM, et al. Tolerability of and adherence to topical treatments in atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(2):415–431. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00500-4.

- Eicher L, Knop M, Aszodi N, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease - strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):2253–2263. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15913.

- Siegfried EC, Paller AS, Mina-Osorio P, et al. Effects of variations in access to care for children with atopic dermatitis. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12895-020-00114-x.

- Hester T, Thomas R, Cederna J, et al. Increasing access to specialized dermatology care: a retrospective study investigating clinical operation and impact of a university-affiliated free clinic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(1):105–115. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00462-z.

- Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, et al. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(4):322–325. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5411.

- Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2324–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285.

- Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):194. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-194.

- McKenna SP, Doward LC. Quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8(3):228–231. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282ffd6cc.

- de Wijs LEM, van Egmond S, Devillers ACA, et al. Needs and preferences of patients regarding atopic dermatitis care in the era of new therapeutic options: a qualitative study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;315(1):75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00403-021-02321-z.

- Koszoru K, Borza J, Gulacsi L, et al. Quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2019;104(3):174–177.

- Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(3):192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22303.x.

- Bashyam AM, Ganguli S, Mahajan P, et al. Lifelong impact of severe atopic dermatitis on quality of life: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(3):1065–1070. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00515-x.

- Na CH, Chung J, Simpson EL. Quality of life and disease impact of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis on children and their families. Children. 20192;6(12):133. doi: 10.3390/children6120133.

- Drucker AM. Atopic dermatitis: burden of illness, quality of life, and associated complications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38(1):3–8. doi: 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4005.

- Huang J, Choo YJ, Smith HE, et al. Quality of life in atopic dermatitis in Asian countries: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;314(5):445–462. doi: 10.1007/s00403-021-02246-7.

- Frazier W, Bhardwaj N. Atopic dermatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(10):590–598.

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med. 2015;4(5):884–917. doi: 10.3390/jcm4050884.

- Weidinger S, Nosbaum A, Simpson E, et al. Good practice intervention for clinical assessment and diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: findings from the atopic dermatitis quality of care initiative. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(3):e15259.

- Silverberg JI, Feldman SR, Smith Begolka W, et al. Patient perspectives of atopic dermatitis: comparative analysis of terminology in social media and scientific literature, identified by a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(11):1980–1990. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18442.

- Burgener AM. Enhancing communication to improve patient safety and to increase patient satisfaction. Health Care Manag. 2020;39(3):128–132. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000298.

- Lang EV. A better patient experience through better communication. J Radiol Nurs. 2012;31(4):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jradnu.2012.08.001.

- Timmers T, Janssen L, Kool RB, et al. Educating patients by providing timely information using smartphone and tablet apps: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e17342. doi: 10.2196/17342.

- Pehrson C, Banerjee SC, Manna R, et al. Responding empathically to patients: development, implementation, and evaluation of a communication skills training module for oncology nurses. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(4):610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.021.

- Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, et al. Discordance between physician- and patient-reported disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis: a US cross-sectional survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(6):825–835. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0284-y.

- Wong ITY, Tsuyuki RT, Cresswell-Melville A, et al. Guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis (eczema) for pharmacists. Can Pharm J. 2017;150(5):285–297. doi: 10.1177/1715163517710958.

- Berruyer M, Delaunay J. Atopic dermatitis: a patient and dermatologist’s perspective. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(2):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00497-w.

- Eczema Society of Canada. The atopic dermatitis patient journey. Ontario (Canada): Eczema Society of Canada; 2020 [updated 2022 Aug 5; cited 2022 Sept 29].

- Willems A, Tapley A, Fielding A, et al. General practice registrars’ management of and specialist referral patterns for atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11(1):e2021118. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1101a118.

- Azizan NZ, Ambrose D, Sabeera B, et al. Management of atopic eczema in primary care. Malays Fam Phys. 2020;15(1):39–43.

- Arkwright PD, Motala C, Subramanian H, et al. Management of difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(2):142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.09.002.

- Suarez-Lledo V, Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e17187.doi: 10.2196/17187.