Abstract

Background

Previous clinical trials presented efficacy and safety of Janus kinase 1 inhibitor upadacitinib through 52 weeks for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib through 48 weeks in real-world clinical practice for Japanese AD patients (aged ≥12 years).

Methods

This retrospective study included 287 patients with moderate-to severe AD treated with 15 mg (n = 216) or 30 mg (n = 71) of upadacitinib daily. Effectiveness was assessed using eczema area severity index (EASI) scores, atopic dermatitis control tool (ADCT), peak pruritus-numerical rating scale (PP-NRS), and investigator’s global assessment (IGA). Safety was evaluated through the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events.

Results

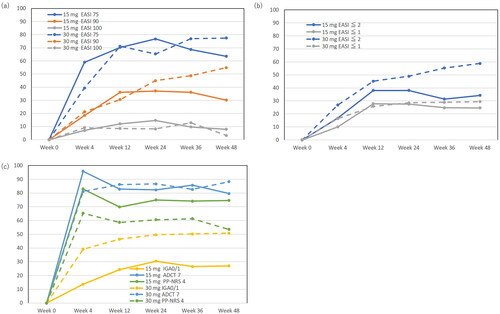

From baseline, EASI, ADCT, PP-NRS, and IGA rapidly reduced at week 4, and the reduction was maintained until week 48 of treatment with upadacitinib at both doses. Achievement rates of EASI 75, EASI 90, and EASI 100 at week 48 were 63.5, 30.2, and 7.9 in 15 mg group, and 77.4, 54.8, and 3.2% in 30 mg group, respectively. Acne and herpes zoster were frequent, but no serious adverse events occurred.

Conclusions

Upadacitinib was therapeutically effective and tolerable for moderate-to-severe AD through 48 weeks in real-world clinical practice.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by type 2-skewed immune responses, pruritus, and skin barrier impairment [Citation1,Citation2]. The pathogenesis of AD is related to cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, IL-22, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and IL-31, which intracellularly transduce signals through Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathways [Citation3].

Various clinical trials presented high efficacy and safety of the oral JAK1 inhibitor upadacitinib for patients with moderate-to-severe AD [Citation4–14]. Favorable effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib have also been reported in real-world clinical practice for AD [Citation15–21]. Furthermore, reports indicate that upadacitinib is effective for AD in challenging areas such as the face, hands, and eyelid region [Citation22]. In addition to the JAK inhibition mechanism of upadacitinib, it is noteworthy that dupilumab acts by blocking IL-4Rα, interfering with IL-4 and IL-13 pathways, and baricitinib functions as a JAK1/2 inhibitor, offering different approaches to modulating the immune response in AD. However, there are only limited data on the effectiveness and safety of long-term treatment (around 1 year) with upadacitinib for AD in real-world clinical practice [Citation23].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the long-term (through 48 weeks) effectiveness and safety of daily 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib treatment for Japanese patients with AD in real-world clinical practice.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2004) and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital. Between August 2021 to September 2023, 287 Japanese patients (aged ≥12 years) with moderate-to-severe AD were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg (n = 216) and 30 mg (n = 71). The diagnosis of AD was made clinically based on the Japanese Atopic Dermatitis Guidelines 2021 [Citation24]. Patients were considered to have moderate-severe AD if they had total eczema area severity index (EASI) score ≥16 or EASI of head and neck ≥2.4. The Japanese Atopic Dermatitis Guidelines 2021 do not specify distinct criteria for prescribing 15 mg versus 30 mg upadacitinib doses in AD treatment yet, leading to variations in practice, among adolescents and those over 65 who often start on 15 mg. Patients tended to start on upadacitinib 15 mg based on patient preference and safety.

It’s important to note that for the upadacitinib 30 mg group, some patients had initially met these criteria with EASI scores above 16 but were swiftly transitioned to upadacitinib 30 mg due to insufficient response to other systemic therapies without a washout period. These patients initially met the inclusion criteria with EASI scores above 16 before their systemic treatment prior to upadacitinib. However, we acknowledge not all pretreatment EASI scores from previous systemic therapies were tracked for these patients. Patients were considered to have moderate-severe AD if they had total eczema area severity index (EASI) score ≥16 or EASI of head and neck ≥2.4. Topical corticosteroids of moderate to highest potency were administered twice daily concomitantly to all the patients.

Before treatment, we collected data on the patients’ age, sex, body mass index (BMI), disease duration, presence of bronchial asthma (BA), allergic conjunctivitis, or allergic rhinitis, previous treatment with dupilumab 300 mg q2W, upadacitinib 15 mg, or baricitinib 4 mg.

Therapeutic effectiveness

The EASI, atopic dermatitis control tool (ADCT), peak pruritus-numerical rating scale (PP-NRS), and investigator’s global assessment (IGA) were analyzed at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 of treatment.

We calculated the proportions of patients whose EASI decreased by at least 75, 90, or 100% from baseline (EASI 75, EASI 90, or EASI 100, respectively) and of patients who achieved EASI scores ≤2 or ≤1 (EASI ≤2 or ≤1). We calculated the proportion of patients who achieved IGA = 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) with ≥2-grade reduction from baseline, specifically for those with a baseline IGA of at least 2/3 (IGA 0/1). We examined the proportion of patients whose PP-NRS was reduced by ≥4-point from baseline among the patients with baseline PP-NRS ≥4 (PP-NRS 4). We calculated the proportion of patients who achieved an ADCT score <7-point, a threshold for control of AD, among patients with baseline ADCT >7-point (ADCT 7). Throughout the study duration, there was a reduction in the number of patients available for follow-up assessments, attributed to missing data and the inability of some patients to complete the study period.

Safety

Safety was assessed by the occurrence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during upadacitinib treatment, until 30 days after the last dose of upadacitinib. A TEAE was defined as any adverse event (AE) that began or worsened after the initiation of treatment.

Informed consent was obtained from patients through an opt-out process before the study commenced, ensuring all participants were informed and had the opportunity to decline participation. Data were then retrospectively analyzed using medical records.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for variables with a normal distribution, and as the median and interquartile range for variables with a nonparametric distribution.

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the significance of differences in the frequency distributions.

Differences between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test for variables with a normal distribution, and Mann–Whitney U test for variables with a non-parametric distribution. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We performed all statistical analyses using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical School).

Results

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, BMI, the frequencies of prior usage of dupilumab, upadacitinib 15 mg, or baricitinib 4 mg were higher while IGA, EASI, ADCT, and PP-NRS were lower in 30 mg group compared to 15 mg group ().

Table 1. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients with atopic dermatitis treated with upadacitinib.

The progression of total EASI, ADCT and PP-NRS during treatment with upadacitinib 15 or 30 mg

In upadacitinib 15 mg group, EASI significantly decreased at week 4 by median [interquartile range] 77. 4 [87.2–70.3]% of baseline, and plateaued thereafter (). ADCT significantly decreased at week 4 by 85. 0 [71.4–95.8]% of baseline, and plateaued thereafter. PP-NRS significantly decreased at week 4 by 75. 0 [57.1–88.9]% of baseline, and plateaued thereafter. In upadacitinib 15 mg group, IGA scores improved significantly, with rapid decrease in proportions of severe (score 4) and moderate (score 3) at week 4 and a noticeable increase in proportion of clear or almost clear (score 0 or 1) until week 24.

Table 2. The clinical indexes at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 of upadacitinib 15 mg treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis, and the comparisons between the stages.

In the upadacitinib 30 mg group, EASI significantly decreased at week 4 by 67.1 [50.0–83.7]% of baseline, and gradually decreased until week 12 with 82.7 [71.5–93.2]% reduction from baseline, and plateaued thereafter (). ADCT significantly decreased at week 4 by 66. 6 [41.3–92.6]% of baseline, and plateaued thereafter (). PP-NRS significantly decreased at week 4 by 66. 7 [33.3–77.8]% of baseline, and plateaued thereafter (). In 30 mg group, IGA scores improved significantly, with rapid decrease in proportions of severe (score 4) and moderate (score 3) at week 4 and increase in proportion of clear or almost clear (score 0 or 1) until week 24.

Table 3. The clinical indexes at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48 of upadacitinib 30 mg treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis, and the comparisons between the stages.

Achievement rates of EASI 75, EASI 90, EASI 100, EASI ≤2, EASI ≤1, IGA 0/1, PP-NRS 4, and ADCT 7 during treatment with upadacitinib 15 or 30 mg

In the upadacitinib 15 mg group, significant improvements were observed across various clinical indexes (EASI 75, EASI 90, EASI ≤2, and IGA 0/1), with notable increases in achievement rates by week 48. Dose-dependent enhancements were observed, with achievement rates for clinical indexes gradually increasing, indicating a pronounced effect at upadacitinib 30 mg.

When the progression of these achievement rates are compared between 15 and 30 mg groups, some differences can be observed. The achievement rates of EASI 90 (), EASI ≤2 (), and IGA 0/1 () were peaked and plateaued at week 12 or 24 in 15 mg group while these gradually increased until week 48 in 30 mg group. The achievement rates of EASI ≤2 () and IGA 0/1 () were higher at each time-point while that of EASI 90 () was higher at later time-points (week 24–48) in 30 mg group compared to 15 mg group. Those progression indicate dose-dependent therapeutic effects of upadacitinib on clinical signs. On the other hand, the achievement rate of PP-NRS 4 () appeared higher in 15 mg group than in 30 mg group at each time-point.

Figure 1. Achievement rates of eczema area and severity index (EASI) 75, EASI 90, EASI 100 (a), EASI ≤2, EASI ≤1 (b), investigator’s global assessment (IGA) 0/1, atopic dermatitis control tool 7 (ADCT 7), peak pruritus numerical rating scale 4 (PP-NRS 4) (c), during upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg treatment in patients with atopic dermatitis (n = 216, or 71, respectively).

Safety outcomes

TEAEs occurred in 93 patients (43.1%) of 15 mg group and in 31 patients (52.1%) of 30 mg group (). Regarding severe AEs, peritonsillar abscess or herpes zoster (HZ) occurred each in 1 patient of 15 mg group, HZ or pneumonia occurred each in 1 patient of 30 mg group. Neither 15 mg nor 30 mg treatment was associated serious AEs or AEs leading to death.

Table 4. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during 48-week treatment with upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg in patients with atopic dermatitis.

AEs leading to drug discontinuation were acne (2 patients), HZ (1 patient), peritonsillar abscess (1 patient), nausea (2 patients), and arthritis (1 patient) in 15 mg group while that was pneumonia (1 patient) in 30 mg group.

Infection-related AEs were effectively managed with standard treatments. Specifically, herpes zoster was occurred in 2.8% of patients in the 15 mg group and in 8.5% of patients in the 30 mg group. Herpes labialis occurred in 4.2% of the 15 mg group and 8.2% of the 30 mg group. Peritonsillar abscess was occurred in 0.5% of the 15 mg group and 1.4% of the 30 mg group.

Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption was occurred in 1 patient (0.5%) in the 15 mg group and 3 patients (4.2%) in the 30 mg group. All instances were classified as either mild or moderate in severity, and all patients achieved remission with outpatient antiviral therapy.

Abnormal laboratory values were generally mild and included anemia in 3.7% of the 15 mg group and 2.8% of the 30 mg group, neutropenia in 0.5% of the 15 mg group and 1.4% of the 30 mg group, hepatic disorder (elevated transaminases) in 2.8% of the 15 mg group and 1.4% of the 30 mg group, and elevated creatinine phosphokinase in 21.3% of the 15 mg group and 23.9% of the 30 mg group.

Acne was reported in 19.9% of patients in the 15 mg group and 23.9% in the 30 mg group, with all cases being manageable through standard treatments.

Neither dosage of upadacitinib treatment generated non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), other types of cancer, lymphoma, adjudicated gastrointestinal perforation, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), or adjudicated venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Discussion

In our real-world study, both 15 and 30 mg doses of upadacitinib significantly reduced EASI, ADCT, PP-NRS, and IGA scores by week 4, with these improvements sustained through week 48. This indicates effectiveness of upadacitinib in rapidly and lastingly ameliorating clinical signs and symptoms of AD. Higher achievement rates for EASI ≤2 and IGA0/1 were consistently observed at a 30 mg dose, indicating a dose-dependent effect. On the other hand, the 15 mg group was associated with a higher achievement rate of PP-NRS4, likely due to the 30 mg group including fewer patients with high baseline PP-NRS scores, which indicates a constrained potential for PP-NRS improvement.

In this real-world study, the achievement rates of EASI 75, EASI 90, or EASI 100 at week 48 of upadacitinib treatment were 63.5, 30.2, or 7.9% in 15 mg group, and 77.4, 54.8, or 3.2% in 30 mg group, respectively. In AD Up trial including Japanese patients, the achievement rates of EASI 75, EASI 90, or EASI 100 at week 52 were 50.8, 33.5, or 13.1% in 15 mg group, and 69.0, 55.4, or 23.6% in 30 mg group, respectively [Citation10]. Thus our real-world data of EASI 75 and 90 are comparable to those in AD Up trial while achievement rates of EASI 100 appear lower. On the other hand, two large Phase III trials showed higher achievement rates of EASI 75 at week 52 compared to our present data; 82.0 or 84.9% in MEASURE Up 1, and 79.1 or 84.3% in MEASURE Up 2, for 15 or 30 mg group, respectively [Citation25]. Furthermore, a real-world study by Chiricozzi A et al. showed achievement rates of EASI 75, 90, or 100 87.6, 69.1, or 44.3%, respectively at week 48 in integrated data of 15 mg and 30 mg doses [Citation23], which was higher compared to our present real-world study. The relatively lower achievement rates of EASI 75, 90, or 100 in our present study compared to previous real-world study or clinical trials may be possibly due to the differences in patients’ age, sex proportion, ethnicities, patient-surrounding environments (climates or exposure to allergens), complications, previous systemic treatments, which may influence the balance of type 1, 2, and 3 immunities or status of skin barrier or microbiota, and alter the treatment responsiveness. Further the treatment responsiveness may be influenced by the differences in strength, doses, or treatment adherence of topical corticosteroids combined with upadacitinib. Especially the lower baseline EASI of 30 mg group in this study might result in the lower achievement rates of EASI 75, 90, and 100 at week 48 compared to the previous studies; baseline EASI was median [interquartile range] 13.2 [8.8–19.8] in this study, compared to the mean ± SD 24.9 ± 12.0 in real-world study by Chiricozzi A et al. [Citation23], 29.7 ± 11.8 in AD Up study [Citation10]. Previous reports on psoriasis indicated that the percent change of psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) increases with increasing baseline PASI, resulting in the lower achievement rate of PASI 75 in patients with lower baseline PASI [Citation26]. Similar tendency may be considered for EASI.

The achievement rate of EASI ≤2 was 34.4 or 58.8% and that of EASI ≤1 was 25.7 or 29.4% at week 48 of 15 or 30 mg upadacitinib treatment, respectively, in this real-world study. Since previous clinical trials and real-world studies did not evaluate the achievement rate of EASI ≤2 or ≤1 in treatment with upadacitinib, our present data should be evaluated in comparison with future real-world studies analyzing these indexes. Since the achievement rates of EASI 75, 90, or 100 depend on the baseline EASI scores, using those of EASI ≤2 or ≤1 might be recommended as another clinical end-point.

We observed that the achievement rate of ADCT 7 was peaked at week 4, which was maintained until week 48 at both 15 and 30 mg doses. The results indicate that both doses of upadacitinib might control AD at early time-point and sustain the control until week 48. Since previous clinical trials and real-world studies did not evaluate ADCT scores in long-term treatment with upadacitinib, our findings may serve as a baseline for subsequent real-world study analyzing ADCT as an index of disease control.

In our real-world clinical study, there were no serious AEs or AEs leading to death until week 48 of treatment, which are largely in line with those reported in previous clinical trials [Citation8–10,Citation12,Citation13]. No new safety concerns were identified for upadacitinib. Though acne, HZ, and elevated creatine phosphokinase were seen, these were mostly manageable by standard treatments.

Throughout the 48-week treatment period of this study, no AEs of malignancy such as NMSC, other types of cancer, or lymphoma were observed in either 15 or 30 mg group, which aligns with the safety profile in an integrated analysis of Phase IIb/III clinical trials of upadacitinib [Citation8]. However, a 48-week period may be too short to evaluate the risk of malignancy, and thus further longer-term studies are necessary to fully assess the potential risk of malignancy in upadacitinib treatment.

Given the recommendations of European Medicines Agency on the use of JAK inhibitors and the safety data from studies such as Oral Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial Surveillance, it is crucial to use upadacitinib with caution, particularly in patients with increased risk of MACE, VTE [Citation27]. Studies of clinical trials and real-world clinical practice have not reported increase in the frequency or severity of MACE or VTE by upadacitinib treatment for AD.

This study has several limitations. First, the participants of this study were limited to Japanese, necessitating further research on patients of different ethnicities. Second, the number of patients treated with 30 mg upadacitinib was smaller compared to that with 15 mg. Thirdly, there is a possibility that some AEs occurring between visits (up to three months) may not have been reported by patients if they resolved naturally and were deemed not significant enough to mention. Fourthly, the progression from upadacitinib 15–30 mg in patients who did not respond adequately to the 15 mg group may have introduced a bias toward lower baseline clinical indexes, such as EASI and NRS, in the 30 mg group. This aspect complicates the evaluation of the real effectiveness of the 30 mg group, as starting measures were potentially influenced by prior treatment outcomes. Additionally, the results obtained for the upadacitinib 15 mg may predominantly reflect outcomes from patients who responded well to this dosage, introducing a potential bias in favor of more favorable results for the 15 mg group.

Conclusion

Upadacitinib treatment at both 15 and 30 mg reduced EASI, ADCT, PP-NRS, and IGA rapidly at week 4, and the reduction was maintained until week 48 of treatment. There were no serious AEs or AEs leading to death throughout the 48-week treatment period. The results support that upadacitinib might be an efficient and tolerable treatment for AD through 48 weeks.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital (protocol code H-2022-945 and 10 February 2022 of approval).

Author contributions

Teppei Hagino conceptualized the study, and mainly organized the manuscript. Naoko Kanda supervised the study. Hidehisa Saeki and Eita Fujimoto revised the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Honda T, Kabashima K. Reconciling innate and acquired immunity in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.02.008.

- Nakajima S, Tie D, Nomura T, et al. Novel pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis from the view of cytokines in mice and humans. Cytokine. 2021;148:155664. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155664.

- Uchida H, Kamata M, Egawa S, et al. Newly developed erythema and red papules in the face and neck with detection of demodex during dupilumab treatment for atopic dermatitis improved by discontinuation of dupilumab, switching to upadacitinib or treatment with oral ivermectin: a report of two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(3):e300–e302. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18743.

- Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(9):1047–1055. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3023.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (measure up 1 and measure up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2151–2168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.025.

- Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2169–2181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00589-4.

- Burmester GR, Cohen SB, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib over 15 000 patient-years across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and atopic dermatitis. RMD Open. 2023;9(1):e002735. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002735.

- Blauvelt A, Ladizinski B, Prajapati VH, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from dupilumab to upadacitinib versus continuous upadacitinib in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label extension of the phase 3, randomized, controlled trial (heads up). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.05.033.

- Silverberg JI, de Bruin-Weller M, Bieber T, et al. Upadacitinib plus topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis: week 52 AD up study results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(3):977–987.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.036.

- Paller AS, Ladizinski B, Mendes-Bastos P, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of the measure up 1, measure up 2, and AD up randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(5):526–535. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0391.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Safety of upadacitinib in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis of phase 3 studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151(1):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.023.

- Katoh N, Ohya Y, Murota H, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib for atopic dermatitis in Japan: 2-year interim results from the phase 3 rising up study. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13(1):221–234. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00842-7.

- Thyssen JP, Thaçi D, Bieber T, et al. Upadacitinib for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: stratified analysis from three randomized phase 3 trials by key baseline characteristics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(9):1871–1880. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19232.

- Kosaka K, Uchiyama A, Ishikawa M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib in japanese patients with atopic dermatitis: a two-centre retrospective study. Eur J Dermatol. 2022;32(6):800–802. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2022.4365.

- Tran V, Ross G. A real-world Australian experience of upadacitinib for the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64(4):e352–e356.

- Schlösser AR, Boeijink N, Olydam J, et al. Upadacitinib treatment in a real-world difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis patient cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(2):384–392. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19581.

- Hagino T, Saeki H, Fujimoto E, et al. The differential effects of upadacitinib treatment on skin rashes of four anatomical sites in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34(1):2212095.

- Hagino T, Yoshida M, Hamada R, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of upadacitinib on individual types of rash in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2023;50(12):1576–1584. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16950.

- Hagino T, Yoshida M, Hamada R, et al. Effectiveness of switching from baricitinib 4 mg to upadacitinib 30 mg in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a real-world clinical practice in Japan. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34(1):2276043.

- Hagino T, Saeki H, Kanda N. The efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in real-world practice in Japan. J Dermatol. 2022;49(11):1158–1167. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16549.

- Licata G, Tancredi V, Calabrese G, et al. Atopic dermatitis and difficult-to-treat areas: a case series of four patients with dupilumab-resistant primary atopic blepharitis and successfully treated with upadacitinib. Dermatitis. 2023. doi: 10.1089/derm.2023.0196.

- Chiricozzi A, Ortoncelli M, Schena D, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib for atopic dermatitis in a real-world setting: an interim analysis through 48 weeks of observation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24(6):953–961. doi: 10.1007/s40257-023-00798-0.

- Saeki H, Ohya Y, Furuta J, et al. Executive summary: Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis (ADGL) 2021. Allergol Int. 2022;71(4):448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2022.06.009.

- Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the measure up 1 and measure up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):404–413. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029.

- Norlin JM, Nilsson K, Persson U, et al. Complete skin clearance and psoriasis area and severity index response rates in clinical practice: predictors, health-related quality of life improvements and implications for treatment goals. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):965–973. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18361.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316–326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109927.