ABSTRACT

COVID-19 disrupted many aspects of domestic violence services including sheltering, in-person advocacy, and access to mental health, visitation, and legal services. Increased demand for services occurred concurrent with the highest levels of pandemic disruptions. Adaptations to many systems and services were made to address survivor’s changing needs. To understand how various aspects of service provision were disrupted during the pandemic, we surveyed a national census of U.S. based domestic violence direct service agencies. Email addresses were collected from online directories and each agency received a link to complete a survey using the online platform Qualtrics. The survey included five sections: services provided; work environment during COVID-19; disruptions caused by COVID-19; personal and organizational disaster preparedness; and demographics. Twenty-two percent of 1,341 agencies responded to the survey. At the start of the pandemic, the most disrupted services were legal and court, sheltering, and mental health/counselling services. Hazard pay, flexible scheduling, and additional information technology support were most frequently mentioned supports provided to mitigate disruptions and support providers and advocates. Disruptions and supports changed over the course of the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the provision of services and advocacy to victims and survivors of domestic violence. Adaptations were made as new control measures were available (e.g. vaccines) and lessons learned were identified (e.g. successful implementation of virtual legal and court services). Maintaining supportive measures post-pandemic will require continued investment in this chronically underfunded, yet critical, sector and applying lessons learned from COVID-19 related disruptions and adaptations.

Introduction

Services provided to clients in many health and social services sectors were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. While many service fields felt the weight of these disruptions, the gaps in accessibility were particularly difficult for fields serving vulnerable and marginalized populations, including unhoused individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and survivors of domestic and gender-based violence (DV/GBV) (Lewis et al., Citation2022). At the onset of the pandemic, disruptions to DV/GBV services were primarily the result of public health control measures such as shelter-in-place orders, which increased the time spent at home and, consequently, the proportion of police calls that were related to domestic violence (Bullinger et al., Citation2020). The effects of COVID-19 were felt over the course of the pandemic, and, while services are still recovering, many DV/GBV services are also facing intensified pre-pandemic challenges (Garcia et al., Citation2022). Many areas of service provisions were disrupted, but sheltering, legal services, and mental health supports faced some of the largest challenges to maintaining and adapting services during the pandemic.

Early in the pandemic, most in-person support services for survivors were disrupted, including critical services like counselling and legal advocacy. Within rapidly changing environments, courts often developed piecemeal policies for remote court processes that did not adequately address access barriers including financial costs, adequate access to information, services, or victim support personnel, and the digital divide (Teremetskyi et al., Citation2021). For example, while prioritizing urgent proceedings like emergency protections, courts were often unable to ensure that survivors could ‘locate a safe space away from their abuser, complete an application, draft a witness statement and attend a telephone hearing’ or get access to legal aid (Speed et al., Citation2020). A longstanding focus on incident-based physical violence and a lack of understanding of the increased risks faced by survivors as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic often allowed for the continuation of coercive control without the availability of adequate legal protections (Koshan et al., Citation2021).

Many forms of emergency sheltering were unequipped to handle the number of people seeking shelter while remaining compliant with public health guidelines, which exacerbated existing shortages. In 2019, the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) reported that an average of 42,964 victims were provided with emergency shelter through their local DV/GBV programs each day (NNEDV, Citation2020). After the onset of the pandemic in 2020, only 38,586 victims per day were accommodated in emergency shelters, a reduction of more than 10% during a time of rapidly increasing demand (NNEDV, Citation2021). According to NNEDV, in 2020 there were 11,047 reports of unmet services daily, 57% of which were for emergency shelter (NNEDV, Citation2021). In the U.S., domestic violence service calls spiked 10% in just the first 5 weeks following the initial March 2020 lockdown (Leslie & Wilson, Citation2020).

Domestic violence has profound effects on the psychological health of survivors, ranging from shame and guilt to self-harm (Ali et al., Citation2021). Trauma, stress, financial insecurity, disability status, and isolation are all risk factors for both domestic violence and for mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Lund, Citation2020; Newnham et al., Citation2022). This makes access to counselling and mental health services critical to survivors of DV/GBV. Factors that limit access to mental health services during non-disaster periods, such as cost, stigma, and a shortage of providers, were intensified by COVID-19, which resulted in increased rates of psychological distress and isolation, as well as burnout among providers of mental health services due to high workloads and limited access to resources (Zivin et al., Citation2022).

In any emergency, needs evolve over the period of response, recovery, and preparedness for the next disruptive event. For example, burnout – particularly among frontline workers – was not anticipated and subsequently poorly managed, placing additional stressors on the individuals providing vital services throughout the pandemic (Denning et al., Citation2021; Gwon et al., Citation2023; Scales et al., Citation2021; Zivin et al., Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented set of obstacles for individuals and organizations that provide services to survivors of DV/GBV. Increases in demand for emergency services came at precisely the same time that these services were being disrupted the most by the early response to the pandemic. Over time, adaptations were made to many systems and services. This study documents disruptions to, and the adaptation of, DV/GBV systems and services across the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings can be used to create plans for supportive measures not only for future disasters and emergencies, but for a more robust system that can remain trauma informed while maintaining services considering increasing complex and compounding impacts to health.

Methods

Survey

A cross-sectional survey of individuals working in domestic violence services in the U.S. was conducted using the Qualtrics platform (Provo, UT). Domestic violence shelters and service providers included in the directory of either domesticshelters.org or the Tribal Resource Tool received an initial invitation and 4 weekly reminders between 19 April 2023, and 1 May 2023, to complete the survey via email. All materials were reviewed by the University of Delaware’s Institutional Review Board (IRB 1597257) and determined to be exempt under Category 2 of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ regulations for the protection of human subjects in research. As part of this review, a waiver of consent was approved and therefore, oral or written consent from participants was not required.

The survey included 34 questions in 5 domains: work characteristics and services provided, work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions to domestic violence services caused by COVID-19, perceptions of personal and organizational preparedness, and demographics. Occupational characteristics included agency/organization type (criminal justice, local/state/federal government, hospital or healthcare-based, community-based or non-profit, therapeutic, other); years of experience of the respondent (<1 year, 1–3 years, 4–5 years, 6–10 years, >10 years); and years in current job (<1 year, 1–3 years, 4–5 years, 6–10 years, >10 years). Respondents also reported their National Network to End Domestic Violence region (New England Mid-Atlantic, Gulf States, Southern States, Upper Midwest, Lower Midwest, Mountain States, of West Coast).

Personal characteristics of the survey respondents included gender (man, woman, trans-man, trans-woman, non-binary, self-identify, prefer not to answer); sexual orientation (bisexual, heterosexual, homosexual other, prefer not to answer); race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Asian American, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, prefer not the answer, some other race or ethnicity not listed, other); ethnicity (Spanish or Latino/a origin – yes/no/prefer not to answer); and education (less than high school, high school diploma or equivalent, vocational or technical school after high school, some college or associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, professional or doctorate degree).

The services provided by the agency or organization were reported (victim advocacy, hotline, shelter, mental health and counseling, healthcare, family visitation, services for children and teens, housing assistance, police-based victim services, legal and court services, culturally specific services, and other services). The disruption of these services was reported at three time points in the COVID-19 pandemic: the start of the pandemic (March 2020 – February 2021), the ongoing pandemic (March 2021 – May 2022), and post-pandemic (June 2022 and later).

Supportive measures provided to employees were also reported. Supportive measures included free or low-cost mental health services, financial support for mental health services, free or low-cost childcare or eldercare services, financial support for childcare or eldercare services, stress-reduction tips or tools, free meals or food options for in-person staff, flexible scheduling, hazard pay, purchase of new technology for staff, information technology support for remote work at home, and other. The availability of these supportive measures was also reported for three time points: before the pandemic (prior to March 2020; during the pandemic (March 2020 – May 2022), and post-pandemic (June 2022 and later).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess data collected via the previously described retrospective survey. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for occupational and demographic variables. The frequency of disrupted services and supportive measures were calculated across the three times points mentioned above. Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportion of respondents reporting service disruptions across phases of the pandemic. All data analyses were conducted using SAS Studio (Cary, NC).

Results

Of 1,341 email addresses collected, 301 individuals responded to the survey (Response Rate = 22.4%). The final analytic sample for this study included 180 of 301 (59.8%) individual respondents; individuals were excluded from analysis if they completed less than two-thirds of the total survey.

Occupational and demographic characteristics

Nearly all respondents worked for a not-for-profit or community-based organization (n = 170; 94.4%). Respondents had long tenures in both the field of domestic violence and in their organizations. A majority (n = 102; 56.57%) had more than 10 years of experience and two in five (n = 73; 40.5%) had been in their current job for more than 10 years. Respondents were from all eight regions of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, with the largest number of respondents from the Lower Midwest (n = 35; 19.44%), South (n = 26; 14.44%), and West (n = 26; 14.4%) (NNEDV [Internet], Citation2024). Respondents’ organizations most frequently provided victim advocacy (96.11%), hotlines (89.44%), shelter (83.89%), housing assistance (71.11%), and legal and court (71.67%) services.

Most respondents were female (n = 164; 91.11%), white (n = 136; 75.56%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (n = 149; 82.78%), and heterosexual (n = 134; 74.44%). Approximately 40% had a bachelor’s degree (n = 70) or a graduate degree (n = 66).

Respondent organization services

More than 70% of the respondents represented organizations that provided victim advocacy (96.11%), hotlines (89.44%), shelter (83.89%), housing assistance (71.11%), and legal and court (71.67%) services ().

Table 1. Services provided by survey respondents’ organizations (n, %).

Disrupted services through the course of the COVID-19 pandemic

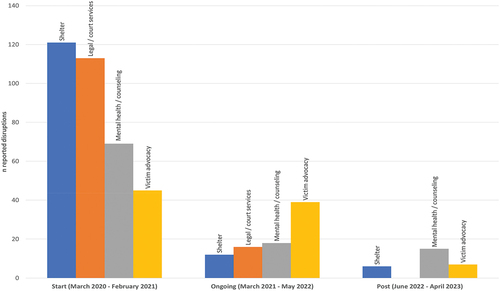

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 – February 2021), respondents identified sheltering, legal and court, and mental health/counselling services as the most severely disrupted services (; ). As vaccines became available and the pandemic evolved between March 2021–May 2022, legal and court, and mental health/counselling services remained disrupted, but victim advocacy services were the most frequently mentioned disrupted service during the second year. Disruptions to mental health and counselling services were still reported post-pandemic. Victim advocacy and shelter services also experienced persistent disruptions. The frequency of reported disruption significantly decreased between the start of the pandemic and the ongoing phase for sheltering (Chi-square = 141.67; p-value <0.0001), legal and court service (Chi-square = 113.67; p-value <0.0001), and mental health counselling (Chi-square = 39.42; p-value <0.0001) services. Disruptions to victim advocacy were consistently reported between the start and ongoing phases of the pandemic (Chi-square = 0.56; p-value = 0.46), but these disruptions significantly decreased from the ongoing to post-pandemic phases (Chi-square = 32.46; p-value <0.0001). Family visitation and culturally specific services were the least frequently reported disrupted service across the initial, ongoing, and post-pandemic periods.

Table 2. Disrupted services through the course of the COVID-19 pandemic (n, column percentages).

Most impacted client groups through the course of the COVID-19 pandemic

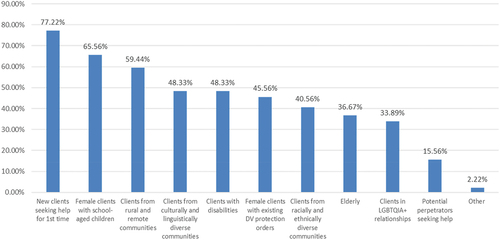

Respondents shared that new clients seeking help for the first time were the most impacted by service disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic (77.22%). Roughly 48% of respondents identified disruptions in services provided to individuals living with disabilities and clients from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Nearly 41% of respondents reported disruptions for clients from racially and ethnically diverse communities. Service disruptions for clients in LGBTQIA+ relationships were reported by 34% of survey respondents. Client disruptions are shown in .

Supportive measures before, during, and after COVID-19 pandemic

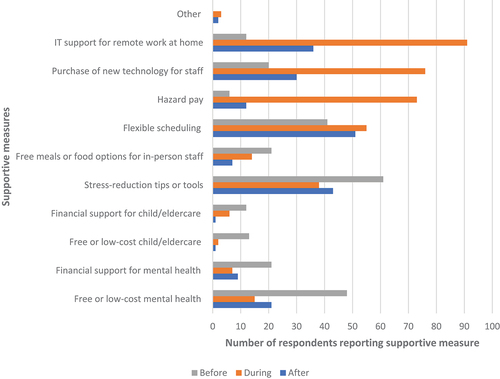

Respondents were asked to identify all supportive measures for employees provided prior to the pandemic, adopted during the pandemic, and maintained by their respective organizations and agencies after the pandemic (). Stress-reduction tips or tools were available before COVID-19, but those resources dropped off during and after the pandemic. Mental health services were less available during the pandemic than before. Hazard pay increased during the pandemic. Flexible scheduling increased during the pandemic and remained a supportive measure for employees after the pandemic. Information technology support for remote work commensurately increased during the pandemic and remained available, although to a lesser degree, after the pandemic.

Discussion

While there have been several analyses of DV/GBV service provision, there is not a wealth of literature on the impacts of COVID-19 on these services (Garcia et al., Citation2022; Kim & Royle, Citation2023). However, of the published research that is available, findings are remarkably consistent across providers and locations. A systematic review by Kim and Royle found DV service providers had to migrate services to remote platforms, contributing to narrowed service repertoires (Kim & Royle, Citation2023). These findings are reflected in our study, where respondents noted persistent challenges in maintaining standard service provision and in expanding services to meet the unique needs stemming from the pandemic. Specifically, respondents in our study reported legal services, sheltering, and mental health and counselling services were the most negatively impacted services.

Further, although this survey was only completed by U.S. based service providers, findings are similar to other studies globally. Research conducted in Victoria and Queensland, Australia demonstrated a similar disruption to DV services immediately following the emergence of the pandemic and shelter-in-place orders (Pfitzner et al., Citation2022). The vast majority of in-person, community services were suspended, which required service providers to adapt unique forms of supportive measures. These adaptations included developing all-female ride shares to transport survivors to safe houses, Child Welfare Officers delivering food and toiletries during the night, and using encrypted software to Zoom video-conference with survivors for increased security from in-home perpetrators (Pfitzner et al., Citation2022). Other countries reported similarly drastic increases in DV/GBV reports during the shelter-in-place orders: France reported a 30% increase, Brazil estimated a 40–50% increase, and China with a 300% increase (Campbell, Citation2020). A United Nations policy brief examining the impacts of COVID-19 on women also reported 25% increases in DV/GBV reports during the onset of the lockdowns in Argentina, Singapore, and Cyprus (United Nations, Citation2020).

DV/GBV service providers reported increased support for remote work and information technology needs during the pandemic, with these supports maintaining higher levels of availability to providers after the height of the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic. The US Department of Health and Human Services delineated rules and practices for telework and remote work for their commissioned corps in 2022 to bolster the workforce as well as improve continuity of operations (COOP) in emergency events (Levine, Citation2022). Without the separation of work and life provided by going into a physical office, in addition to social, economic, and family stressors exacerbated to the pandemic, workers across fields experienced high levels of burnout (Scales et al., Citation2021). Steps such as expanding flexible scheduling and increased availability of mental health supports were adopted in an effort to better support employees and prevent burnout across sectors. Respondents in our study also reported more flexible scheduling during and after the pandemic. Public health practitioners noted that schedule flexibility and remote work had both positive and negative implications for burnout experiences (Scales et al., Citation2021). However, the preponderance of literature around the utility of flexible scheduling for combating burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic is among clinical providers. This underscores the importance of including DV/GVB professionals as essential, frontline workers in future public health emergencies as well as the need to include the DV/GVB workforce in research. Increasing capacity and providing flexibility are important for improving COOP for DV/GBV services and preparing the DV/GBV workforce to meet the needs of the populations they serve in future public health emergencies.

This research has several important limitations. The sample size was relatively small although responses were comparable to current research related to response rates and nonresponse bias (Hendra & Hill, Citation2019). To assess bias, we compared complete responses and responses that included less than two-thirds of the survey, and there were no statistically significant differences in these two groups for any personal and work-related variables (e.g. region, years of experience, years in current job, type of organization). Demographic information was missing for all those excluded from the analysis, likely because these were the last five questions on the survey. Additional information on organizational characteristics, such as the number of individuals served, funding, and staffing were not assessed in the survey. However, these data could have contributed additional insights for this study.

Conclusions

Like nearly all social services systems, domestic violence services and advocacy were extensively disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the public health measures implemented initially to control its spread. However, the disruptions and limitations to the provision of services documented here should not be blamed on providers or advocates; rather it should be examined more holistically as a systemic obstacle DV/GBV providers had to adapt to and overcome – largely without adequate support measures and in the context of increased demand. Lessons learned were identified (e.g. successful implementation of virtual legal and court services) and applied in real time. It is, however, essential for service providers and advocates to take time post-pandemic to document additional lessons learned to ensure that supportive measures can be better maintained in future disasters and emergencies, which are increasing in frequency and severity. Recognizing the vital role played by DV/GVB providers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, these professionals should be considered as essential workers in public health emergencies. These individuals and organizations need both financial investments and other supports to apply lessons learned from COVID-19 related disruptions and adaptations.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no relevant or material financial or other interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Data availability statement

Supporting data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ali, P., Rogers, M., & Heward-Belle, S. (2021, August). COVID-19 and domestic violence: Impact on mental health. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 11(3), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCP-12-2020-0050

- Bullinger, L. R., Carr, J. B., Packham, A. (2020, August). COVID-19 and crime: Effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence. NBER Working Papers [Internet]. Retrieved December 21, 2023, from https://ideas.repec.org//p/nbr/nberwo/27667.html

- Campbell, A. M. (2020, December). An increasing risk of family violence during the covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International Reports, 2, 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089

- Denning, M., Goh, E. T., Tan, B., Kanneganti, A., Almonte, M., Scott, A., Martin, G., Clarke, J., Sounderajah, V., Markar, S., Przybylowicz, J., Chan, Y. H., Sia, C.-H., Chua, Y. X., Sim, K., Lim, L., Tan, L., Tan, M., Sharma, VK., … Purkayastha, S. (2021). Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 16(4), e0238666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238666

- Garcia, R., Henderson, C., Randell, K., Villaveces, A., Katz, A., Abioye, F., DeGue, S., Premo, K., Miller-Wallfish, S., Chang, J. C., Miller, E., & Ragavan, M. I. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intimate partner violence advocates and agencies. Journal of Family Violence, 37(6), 893–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00337-7

- Gwon, S. H., Thongpriwan, V., Kett, P., & Cho, Y. (2023, January). Public health nurses’ perceptions and experiences of emergency preparedness, responsiveness, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nursing, 40(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13141

- Hendra, R., & Hill, A. (2019, October). Rethinking response rates: New evidence of little relationship between survey response rates and nonresponse bias. Evaluation Review, 43(5), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X18807719

- Kim, B., & Royle, M. (2023, February). Domestic violence in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: A synthesis of systematic reviews. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 25(1), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231155530

- Koshan, J., Mosher, J., & Wiegers, W. (2021, January). COVID-19, the shadow pandemic, and access to justice for survivors of domestic violence. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 57(3), 739–799. https://doi.org/10.60082/2817-5069.3605

- Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020, September). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241

- Levine, R. L. (2022). Telework and remote work [internet]. US Department of Health and Huamn Services. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://dcp.psc.gov/ccmis/ccis/documents/CC313.01.pdf

- Lewis, R. K., Martin, P. P., & Guzman, B. L. (2022, August). COVID‐19 and vulnerable populations. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(6), 2537–2541. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22880

- Lund, E. M. (2020). Interpersonal violence against people with disabilities: Additional concerns and considerations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Rehabilitation Psychology, 65(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000347

- Newnham, E. A., Chen, Y., Gibbs, L., Dzidic, P. L., Guragain, B., Balsari, S., Mergelsberg, E. L. P., & Leaning, J. (2022, January 21). The mental health implications of domestic violence during COVID-19. International Journal of Public Health, 66, 1604240. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.1604240

- NNEDV. (2020). 14th annual domestic violence counts report [internet]. https://nnedv.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Library_Census-2019_Report_web.pdf

- NNEDV. (2021). 15th annual domestic violence counts report [internet]. https://nnedv.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/15th-Annual-DV-Counts-Report-National-Summary.pdf

- NNEDV [Internet]. (2024, January 10). NNEDV Coalition Regions. https://nnedv.org/content/nnedv-coalition-regions/

- Pfitzner, N., Fitz-Gibbon, K., & Meyer, S. (2022). Responding to women experiencing domestic and family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring experiences and impacts of remote service delivery in Australia. Child & Family Social Work, 27(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12870

- Scales, S. E., Patrick, E., Stone, K. W., Kintziger, K. W., Jagger, M. A., & Horney, J. A. (2021, November). A qualitative study of the COVID-19 response experiences of public health workers in the United States. Health Security, 19(6), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2021.0132

- Speed, A., Thomson, C., Richardson, K., & Stay Home, Stay Safe, Save Lives? (2020, December 1). An analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on the ability of victims of gender-based violence to access justice. The Journal of Criminal Law, 84(6): 539–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018320948280

- Teremetskyi, V., Duliba, Y., Drozdova, O., Zhukovska, L., Sivash, O., & Dziuba, I. (2021). Access to justice and legal aid for vulnerable groups: New challenges caused by the Сovid-19 pandemic. Journal of Legal, Ethical & Regulatory Issues, 24(1), 1–11.

- United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women [internet]. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf

- Zivin, K., Chang, M. U. M., Van, T., Osatuke, K., Boden, M., Sripada, R. K., Abraham, K. M., Pfeiffer, P. N., & Kim, H. M. (2022, June). Relationships between work–environment characteristics and behavioral health provider burnout in the veterans health administration. Health Services Research, 57(Suppl S1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13964