ABSTRACT

This paper examines new configurations of the urban periphery in a digital age. It moves beyond current scholarship in urban and regional studies which points to the emergence of suburbia and informal settlements as the new urban periphery. The paper argues that while suburban growth has been a key force in the production of the urban periphery so far, the coming of a digital age breaks down the conventional conflation of urban edge with the urban periphery. The periphery in a digital age is located simultaneously across the geographic centre and edge, across material and digital urban worlds. The uneven, fragmented and disconnected nature of physical and digital infrastructures in the contemporary world has produced a far more fragmented and dispersed nature of the periphery that requires deeper examination and analysis.

Introduction

In April 2022, I was in a taxi travelling along the road towards Bhiwandi, a small town located 47 km on the north-eastern periphery of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR). Bhiwandi has been known for a very long time as the “Manchester of India” for its powerloom industries which have shaped the textile economy of the region since the early nineteenth century. The road from Mumbai to Bhiwandi, passes through a landscape of extremes – lush green farmlands, dense high-rise housing developments, office complexes, chemical factories, busy motorways, roadside service stations, and forever traffic jams. Making the journey from Mumbai to Bhiwandi can take up to five hours during the Monsoons.

This is a heavily urbanised industrial corridor, and yet as you reach Bhiwandi you realise that this is a place unlike no other town in Mumbai’s fringes. Unlike other satellite towns of Mumbai, such as Kalyan or Thane, Bhiwandi feels out of place within Mumbai’s striking global reach. As a manufacturing town, almost half (49%) of Bhiwandi’s one million population live in slums and informal settlements. It exhibits all the outwardly signs of a developmental crisis – it has a low literacy rate (79.48%), a low sex ratio (709 females/1000 males) mainly because of the migrant labour, a majority (56%) Muslim population with high indices of deprivation and with poor access to urban basic services such as water, sanitation, energy and network connectivity. It also has very high digital inequalities among young Muslim women, elderly and migrant workers in terms of access and capacity to use mobile phones and digital platforms (Shaban, Datta, and Fatima Citation2023).

One can hear Bhiwandi before reaching it. By this, I do not just mean the noise of the traffic and the people on the streets. Rather, as one approaches the city particularly at night or in the early hours of the day when traffic is slower, one can hear the constant hum of the powerlooms () – the continuous click clack of the warp and weft which are woven into one of the best cotton cloths in India – supplying raw material for well-known textile hubs in other parts of India such as Gujarat and Rajasthan. These powerlooms do not stop – ever. They slow down during the Friday prayers, but the constant hum gives an auditory identity to the city – a working home-based industrial town made and run by migrant labour from across India. As one loom worker said to us, “You can come to Bhiwandi in the morning, and you will find work by evening”.

But just outside Bhiwandi on the Mumbai-Agra Highway, one begins to see a territorialisation of India’s digital age. Miles upon miles of the highway that stretches from Bhiwandi are dominated by mega-scale warehouses. Indeed, Bhiwandi is now India’s largest e-commerce and logistics hub (), with companies like Amazon, Flipcart and Nyka holding their goods here. This is the paradox of India’s digital urban age – while Bhiwandi is bypassed by Mumbai’s regional development initiatives, the advancement of digital infrastructures and technologies in the region sustains some of the most sophisticated logistics facilities in Bhiwandi. This, then, is the periphery in a digital age where territory, logistics and people come together in uneven ways to produce a networked marginality.

Fuelled by a ready supply of large agricultural land parcels around Bhiwandi, logistics now defines the temporality of the city. Late evening and early morning drives in and out of Bhiwandi mean navigating through the heavy goods vehicles and lorries which often break down or crash by the side of the highway. A whole bevvy of roadside eateries or Dhabas have emerged along the highway that is now supporting a vibrant local nightlife for its youth and businessmen. Bhiwandi’s complex transformation raises the question – what constitutes the urban periphery in a digital age?

This paper is about a rather unfashionable subject – information. As compared to a more topical subject – data, I am interested here in examining how informational power over land, infrastructure and people materialises in the periphery. Here I take the definition offered by Zins (Citation2007):

Data are the basic individual items of numeric or other information, garnered through observation; but in themselves, without context, they are devoid of information. Information is that which is conveyed, and possibly amenable to analysis and interpretation, through data and the context in which the data are assembled. (Zins Citation2007, 479)

I argue that Bhiwandi captures a territorial politics of the “informational peripheries” (Datta Citation2023) that can offer us a different vantage point for understanding the spaces of exclusion and fragmentation created in the margins of metropolitan regions in the global south. The informational periphery extends the idea of a periphery beyond geography to informational space. It attends to diverse and heterogenous forms of digitally mediated urbanization that are taking shape in metropolitan regions. Instead of considering the periphery as a primarily geographical metaphor, I approach informational peripheries as both geographically and digitally distant space that is entangled with regimes of territory, logistics, and people. It includes subjects who are uncountable as well as territories that are unmappable – digitally, socially and materially. I propose that the empirical and theoretical development of informational peripheries can provide an important vantage point for interrogating the political and technological relations that are at the heart of the emergence of urban peripheries in the digitalized state.

In this paper, I will make three key arguments. First, there needs to be renewed attention to the concept of territories in understanding peripheralization in the global south. Although the rich scholarship on urban peripheries and peripheralization articulate how networks of state and non-state actors intersect and overlap across the governance of public land and private capital (Gururani and Kennedy Citation2021), territory in an informational age is more than land or financial assets. For Elden (Citation2010), territory is a political technology – it demands a particular technical and legal apparatus of the state governance that is strategic. Using Elden’s notion of territory, I argue that the digital is another category of political-technological space. It is not just territory that is digitised and transformed into information; the digital also has a territoriality that impacts the periphery. Fibre-optic cables, sensors, barcodes, robotics, and CCTV enact political-technological transformations of spaces in uneven and unequal ways in the periphery that are also tied to how people, knowledge, and narratives shape the periphery.

Second, moving beyond earlier conceptualizations of the “infrastructural turn” in the periphery, I argue that the periphery should be seen through a “logistics turn” (Cavalier Citation2016; Cowen Citation2014; Keith and Santos Citation2021; Lyster Citation2016; Mutter Citation2023). Logistics focus exclusively on speed, which in return depends on the capability of informational flows to move smoothly as well as to stick around for when required on-demand. Cavalier calls this logistification (Cavalier Citation2016), which (like industrialisation) is a process of transformation that produces a frenzied rush of information through space and time to speed up the movement of material things. Cavalier notes that logistification may appear to be embedded nowhere, but it is a deeply territorial process. Seen through this lens of logistification, the periphery emerges as an informational space inherently tied to the territorialisation of global e-commerce (in the form of warehouses and logistics parks) that circulates capital, goods, labour and information precisely because of the ways that they are networked through the digital.

My final argument is that transformations in the informational periphery deploy extractive technologies of data, labour and resources that could be seen as forms of “settler colonialism” (Yiftachel Citation2009). Logistics are enabled by flows of people – their embodied labours shape the ways that global e-commerce stick in and flow through these places by pushing labouring bodies within its shadows. However, settler colonialism in the context of Bhiwandi is not the long-term occupation of land by colonisers, but rather a more complex process where settler colonialism unfolds by proxy. I argue that forms of settler colonialism are evident in the ways that global logistics settle in Bhiwandi as warehouses, and the local networks of casteist, ethnic and religious connections to land and its accumulation enable this stickiness.

Informational periphery

In the global south, conceptualisations of the periphery have been largely driven by debates around capital accumulation and dispossession. The rich scholarship on the periphery has presented a number of concepts that capture the periphery as – desakota, suburban, rurban, and so on. This approach towards the periphery is often conflated with the “peri-urban” interface of cities and rural areas. Seen as comprised of industrial zones, business technology parks, gated communities and slums/informal settlements, among others, peripheries are often understood as the result of land acquisition, auto-construction, housing and municipalisation (Caldeira Citation2017; Erman and Eken Citation2004; Hernandez and Titheridge Citation2016; Kohli Citation2004; Pieterse Citation2019; Sood Citation2021). Peripheries in this framing become the outcome of “rapid and unplanned” urbanisation and urban growth – a geographic metaphor to stand for exclusion from the city.

I argue that the geographical notion of periphery around suburban, peri-urban and exurban neighbourhoods that has persisted in urban studies needs to be rethought through the capacities afforded by digital infrastructures and technologies. In urban studies, although there has been a move towards understanding digitally mediated cities, in particular the now prolific literature on smart cities – periphery is, however, not a common focus in this work. A consideration of the impacts of a digital age complicates a material geography of the periphery. The periphery need not necessarily be in the urban edge; rather, the uneven and disconnected infrastructures of a digital age produce a far more fragmented and dispersed nature of the periphery. From the digital sentience proposed by smart city scholars (Gabrys Citation2014) to the geographical expansion of the city critiqued as suburbanisation (Keil Citation2017) or agrarian transformations (Bhagat Citation2005), how do we reimagine the notion of periphery today? Given that much of the information about cities today is mediated through the digital, what then constitutes the urban periphery in a digital age?

Over a decade ago, AbdouMaliq Simone conceived of the periphery through “shared colonial histories, development strategies, trade circuits, regional integration, investment flows and geographical articulation.” (Simone Citation2010, 10). For Simone, peripheries have a double status – as a “space of insufficiency and incompletion” (40) – and although peripheries refer to the outskirts of cities in common usage, Simone urges us to rethink cities in the global south also as located within the peripheries of urban theory. Simone proposes that peripheries are

a buffer, a space in-between the nation or city and something else that is formally more foreign, more divergent than the city or nation for which it acts as a periphery … where more direct forms of confrontation among cities, regions and nations (41–42)

heterotopic, exceptional, intensely specific, hidden in plain sight, prefigurative, or dissolute. In all instances the surrounds are infrastructural in that they entail the possibilities within any event, situation, setting or project for something incomputable and unanticipated to take (its) place. (Simone Citation2022, 5)

To consider the impacts of a digital age on the periphery, I borrow from Anita Say Chan’s (Chan Citation2013) idea of the “networked periphery,” which conceives peripheries as spaces made through networked power and embody notions of “banishment, dispossession, disempowerment and primitive accumulation.” Chan argues that we need to focus on the nature of fragmented and splintered relationships that are being produced across cities and regions that makes “networked digitisation as a unique infrastructural violence of the periphery.” Here periphery becomes at once a site, a node, and an outcome of information flows. As digital infrastructures connect physical and virtual worlds, “[w]hat … counted as a credible piece of information, what was granted epistemological virtue and by what social criteria” (Stoler Citation2002, 101) remains fluid and contested in the networked periphery. Informational flows and blockades in the periphery follow material infrastructures and regulatory landscapes, making peripheries both geographically grounded and spatially dispersed.

I extend this conceptualisation of the networked periphery by incorporating a logistical lens in the periphery. This follows on from the well-established “infrastructural turn” which has so far produced rich scholarship on the ways that infrastructures produce new urban geographies in the urban and peri-urban margins (Du Citation2019; Easterling Citation2016; Furlong Citation2021; Kanai and Schindler Citation2019). Indeed, Easterling argues that infrastructural space forms the bedrock of how the state governs through “extrastatecraft” (Easterling Citation2016). However, an infrastructural lens seems inadequate to explain Bhiwandi’s territorial expansion through the mushrooming of warehouses, which on the outside has been driven by the networks and circulation of global capital on the one hand, and the speed of informational exchange enabled by a local population on the other hand. A wider understanding of its transformation requires a closer look at what is recently called a “logistics turn” in urbanisation (Cavalier Citation2016; Cuppini and Frapporti Citation2018; Keith and Santos Citation2021; Lyster Citation2016; Mutter Citation2023). Keith and Santos argue that “logistics emerges as a category of analysis as the combination of infrastructures, networks and urban speed” (Keith and Santos Citation2021, 168). Although logistics have a genealogy in the war machine particularly in its emphasis on speed and connectivity of military operations, logistics have recently become entrenched in the capitalist system driving the ways that goods, commodities, information and people can be moved great distances with tremendous speed. In her important work “The Deadly Life of Logistics,” Deborah Cowen (Cowen Citation2014) argues that logistics is at the heart of contemporary political economies of globalisation. By extending this lens, logistics brings in an entanglement of temporality and territoriality in earlier notions of infrastructural space. Logistics depend on speed, which in return depends on the capability of these flows to move smoothly as well as to stick around for when required on-demand.

A logistics turn in the periphery thus emerges from the deep relationship between information, territory and people. Logistics, as Lyster notes, draws together places “anywhere, nowhere and everywhere” (Lyster Citation2016, 18). As Cavalier argues, “[r]ather than seeking density, logistics aspires to coverage” and therefore is “an agent in the transformation of territory” (Cavalier Citation2016, 6). Logistics includes infrastructure, but it extends beyond infrastructural space. It brings together “informational systems, physical systems and mediating systems” (Cavalier Citation2016, 51), thus moving beyond infrastructural fluidity to territorial fluidity. Logistics aims at coverage, but in order to circulate anywhere it also needs to materialise as holding spaces – in territories where it can remain ready, on-demand, and available to move anytime anywhere with speed. Logistics is mobilised through buildings, roads, ports, trucks, wires and cables which carve out territories for time–space compression. Logistics leverages the transformation of territory even as it appears to become invisible in terms of its territorial reach everywhere. Logistics is informational and therefore virtual, but it is also sticky and territorial as it descends in places that are located at the nodes of a vast global network which seeks to establish maximum coverage.

While a logistical lens enables us to understand how territory becomes fungible and therefore ready for transformation, I argue that in Bhiwandi this transformation of territory begins from a different genealogy of logistics rooted in social marginalisation. This proposes colonisation as the earliest form of logistics. As Cuppini and Frapporti (Citation2018) argue, slave trade was a global supply, demand and flow of human bodies reduced to bare life that enabled access to and extraction from territories.

[M]odern logistics is not just about how to transport large amounts of commodities or information or energy, or even how to move these efficiently, but also about the sociopathic demand for access: topographical, jurisdictional, but as importantly bodily and social access. (Cuppini and Frapporti Citation2018, 96, original emphasis)

As Cavalier argues – “logistical territory is fungible” (Cavalier Citation2016), i.e. based on a general set of characteristics. The fungibility of territory depends upon its positioning within the informational periphery. On the one hand, this territory is positioned at the intersections of high-speed transport and digital infrastructure flows, and on the other hand, it lies at the margins of social and informational access. Here information refers to contextually relevant data to which a certain logic has been applied for it to carry meaning and serve a purpose (Jordan Citation2015). Those who face increasing marginalisation are located in the informational periphery, as they are stripped of their access to meaningful information, while being available as precarious labour for logistics flows. A logistics turn in the periphery then produces an “urbanization of information” (Shaw and Graham Citation2017) whereby information flows and infrastructures are directed towards an urban extractivism in the peripheries.

Methodology

This paper is based on a two-year research project titled “Digitising the Periphery” whose larger aim was to investigate how peripheral municipalities implement national digitisation initiatives within systems of local governance, the struggles faced by marginal citizens in accessing public services in the peripheries, and the pathways they use to overcome these struggles and build resilience. The research team involved the author as principal investigator located in a British university, and a co-investigator and post-doctoral fellow located in Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. The project aimed to use methods such as surveys, semi-structured interviews and focus group meetings, and finally produce a toolkit for digital democracy and sustainable urbanisation.

Although initially warehouses were outside the scope of the research, since our case study was Bhiwandi (and warehouses are located outside Bhiwandi municipal boundaries), it became clear pretty soon that if we were to understand the impacts of digitising the periphery, we needed to pay closer attention to the rapid transformations in the peripheries of Bhiwandi. It seemed particularly amongst the younger sections of Bhiwandi, that employment in the warehousing sector was seen as the future. So while powerlooms were declining, younger people were turning their back on this traditional sector and reaching out towards global logistical networks through the informational space afforded by digital infrastructures and technologies. As our interviews snowballed, we were led towards informants who had more to do with the warehousing sector than the powerlooms.

Perhaps this was to do with the gatekeepers who were approached. We started with a local vocational college, whose principal was a close friend of my co-investigator, who then introduced us to a number of important stakeholders in Bhiwandi. Since Bhiwandi is a smaller urban centre and has a Muslim-majority population, the most important stakeholders in the city are well-networked with each other. My positionality as Indian and a Professor in a British university, as well as my co-investigator’s positionality as a Muslim man and a senior academic in a reputed Indian university was significant in gaining access and trust with most of the participants. As the project started in 2021 during the COVID-19 lockdown, our initial interviews and some focus group meetings were conducted via Zoom. Once the lockdown was lifted and the research team could travel to Bhiwandi, we conducted an in-person focus group meeting in the vocational college. There we were introduced to Saif, a young Muslim man who had become a successful broker in the warehousing sector. Saif was the protégé of an influential engineer-turned-developer in Bhiwandi who had built several warehouses there and in the Middle East. Saif was responsible for setting up several meetings with warehouse developers, managers, brokers as well as locally elected officials.

All of our participants were residents of Bhiwandi, and all the participants in the warehousing sector were men. Even though many were directly benefitting from the warehousing economy, they could see how its emergence had led to the channelling of resources away from the Bhiwandi-Nizampur Municipal Corporation. We were unable to interview any warehouse workers because of the demanding nature of their work as well as the surveillance and control that they faced, which increased their insecurities about answering questions related to their work.

Bhiwandi’s peripheral futures

Bhiwandi’s origins as a municipality are vested in its connections to the British Empire and its subsequent making as a migrant town since the early nineteenth century. In 1857, after the Sepoy MutinyFootnote1 was violently suppressed by the British East India Company, thousands of Muslim weavers in North India travelled southwards along the Mumbai-Agra Highway to Bhiwandi. They carried with them their skills and their tools – the powerlooms, which established Bhiwandi and the region around it as one of the most prosperous textile manufacturing regions in the country. As population rapidly increased, Bhiwandi was given the status of a Municipal Corporation in 1864. As Bhiwandi prospered over the next few decades, a nearby town of Nizampur was incorporated within its boundaries and was named the Bhiwandi-Nizampur Municipal Corporation in 1918.

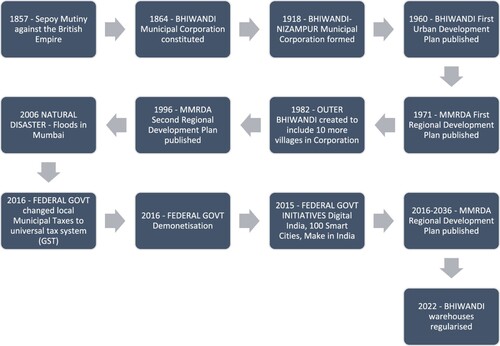

As evident from the timeline in , no comprehensive effort was made to plan the city till 1960, when the first Development Plan of the city was prepared. The Municipal boundary was further extended in 1982 to include ten villages within the municipal limits. This new extension is today collectively identified as Outer Bhiwandi. While the powerlooms thrived and attracted migrant workers from across the country to work here, the powerloom sector itself remained largely unregulated and informal with mainly cash-based transactions, employing thousands of migrant workers across India. This “informal” and unregulated status of powerlooms was largely due to these being home-based industries, set up as family businesses over generations, where families lived on the upper floors of houses which had powerlooms on the ground floor. Bhiwandi now has approximately 650,000 powerlooms, which is roughly 33% of the country’s total powerlooms (Basu Citation2020). Despite its prosperity and significance as a national textile hub, it is this informal status which led to Bhiwandi being bypassed in successive Regional Development plans produced by the Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Authority (MMRDA) in 1971 and 1996.

In around the early 1990s, warehouses began to relocate from Mumbai as commercial rents increased in the metropolis and Bhiwandi became a cheaper location to store goods with its easy access to airports, seaports and the Mumbai-Agra Highway. In 2006, as Mumbai was hit with severe floods and many goods were destroyed, there was a mass exodus of warehouses into Bhiwandi. Around this time, highway networks were also expanded in the region, particularly the Mumbai-Nashik Road (which passes through Bhiwandi) was widened. After a decade of supporting warehouses, Bhiwandi’s strength as a warehousing hub was reinforced through regulatory financial instruments. In 2016, the national government removed Octroi – local sales taxes levied by each regional state for industries or businesses – and installed General Standard Taxes (GST) across India. With GST, there was now one universalised taxing system for commercial transactions, which meant that warehouses would pay the same taxes in any part of the country. So post GST, Bhiwandi became even more attractive for warehousing as it had vast amounts of cheaply available land in addition to its locational advantage.

Initially, though, farmers were reluctant to sell their land, but recent transactions use a “vadai” system in which the farmer receives a portion of the rent generated by the warehouse and therefore is ensured a continuous income. This has led to increased interest and desire among the large agricultural landholders to lease their land for warehouses. However, these are irregular legal instruments to transfer land from the farmer to the developers, as they are all located outside the boundaries of the municipal corporation in the villages. Thus it was possible to circumvent the building approval processes leading to the proliferation of warehouses in Bhiwandi’s peripheral villages. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown exacerbated a demand for online shopping and e-commerce that led to the mushrooming of warehouses since 2020.

In the last few decades, there has been a revolution of sorts in the spread and improvement of digital infrastructure in the MMR. With the rising demands for increased and better connectivity as India’s economic capital, the Mumbai region now has some of the most advanced information and communication technologies in India. In recent years, with the launch of the national Digital India Initiative in 2015, the MMR has seen the setting up of large data centres and Business Processing Outsourcing (BPOs) operations in the peripheries of Mumbai and in the satellite township of Navi Mumbai. Digital infrastructure – such as fibre-optic cables, real-time communication, surveillance, barcoding, automations, heat management and robotics at par with international standards – that form the foundation of advanced warehousing facilities are therefore readily available in and around Bhiwandi. Along with this, the entry of Middle Eastern steel companies such as Jameel Steel, which introduced mega-scale prefabricated steel construction, led to the transformation of the warehouse buildings from a modest 20,000 square feet to up to 600,000 square feet ().

The warehousing industry has transformed Bhiwandi into a “supermarket for e-commerce players” (Borah Citation2020) and is now seen as Bhiwandi’s future as well as the future of the MMR. Companies from 200 countries now have warehouses in Bhiwandi, occupying 210 million square feet of warehouse area. While its older powerloom industry has fallen into rapid decline, the warehouses are deemed to be the industry of the future. The most recent 2016–2036 MMRDA Regional Development Plan mentions investment into warehouses as a future strategy, and indeed most of these warehouses were regularised in 2022.

Settler colonial logistics

Cities in settler-colonial contexts, occupy a paradoxical kind of site in relationships between colonizer and colonized. They occupy Indigenous lands and form a central component of the settler society, yet at the same time render Indigeneity profoundly out of place. The settler city is often portrayed as a symbol of a “new world,” a space of liberalism and democracy, a hub of globalization, a magnet for international migration, or a center of investment and corporate power – all dominant discourses that conceal their ongoing colonial nature. (Porter and Yiftachel Citation2019, 177)

Warehouses in Bhiwandi are brought about by their classification within the industrial sector that enables ease of economic transactions and generation of loans to the sector. Three types of regulatory mechanisms that enable the extraction of value from land lead to the production of warehouses. First is the agreement with the investor who invests in the land and in the warehouse. Second is the agreement with the maintenance company which supplies the physical and digital infrastructure and maintains them. Third is the agreement with the farmer to whom these companies pay a nominal “vadai” charge per square foot. These three regulatory instruments enable the companies to territorialise the logistics turn in the region. These practices also enable what Porter and Yiftachel call the “paradoxical” nature of settler colonialism, whereby warehouses occupy ancestral land held for generations in farming families, and in doing so also render the agricultural way of life in the region profoundly incompatible with the future of the region.

Through these regulatory practices, three types of warehouses have emerged in Bhiwandi. First are the express warehouses, which work 24/7 and often store perishable goods primarily related to groceries or e-commerce such as Big Basket, Kmart, Amazon, Flipkart and so on. In this, the goods come in and out mostly from the same region, and these are reliant on fast speedy connections. Second are the logistics warehouses, which occupy the largest warehousing spaces in the world (around 700,000 square feet) and, therefore, also demand a huge amount of power supply. Third are the custom bonded warehouses, which are primarily focussed on brand changing and repricing and are therefore deterritorialised from the economic and regulatory constraints of the region. These warehouses store goods and labels that are not produced or sold in India, and therefore they do not pay any customs or excise duties in India. For example, their goods are brought from China, the labels are changed in these warehouses, and then they are sold to markets in UK and Europe.

But settler colonialism does not happen through regulatory practices alone. As Cuppini and Frapporti note,

Logistics delivers humans, animals, energy, earthly materials to an end, to a point, the point of production. But this includes, crucially, the point of production of the settler, the production of the entrepreneur, the banker, the slave trader, and the investor. (Cuppini and Frapporti Citation2018, 99–100)

It is also possible to maintain these activities and the extractive value of land through intimate communication systems between businesses, brokers and their investors. In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, when investors were unable to meet face to face, the Community Tree App became a popular platform of communication when downloaded to their smartphones. The Community Tree App connected different castes and ethnic communities and has continued even after the lockdown was lifted.

Fungible labour

During a very hot Ramadan afternoon, we were sitting in Ajmal’s office to cool down. Ajmal is a middleman who runs an “educational institution,” which in reality is more like a vocational college. Ajmal was a small-time businessman who lost his business during the COVID-19 pandemic. Close to bankruptcy, he literally received a lifeline when e-commerce companies began to flourish at the same time. Ajmal’s main livelihood now was receiving commissions by matching floating labour in Bhiwandi with e-commerce companies, and he has recently employed seven staff just to facilitate this. Ajmal agreed that it was very exploitative currently, as workers in the warehouses were not allowed to unionise. He compared this to the gig sector, where employees can be hired and fired instantly. The desirable age for warehouse workers is 18–38 – the younger the better. Engineers are always employed as data operators; the less educated are employed in loading and unloading work. Workers need to have a very short half-page CV. If the warehouse hires them, then they stamp “on trial” basis on that CV, with most positions lasting up to three months. Ajmal agreed that this was illegal as per national employment laws, but the warehousing sector uses a loophole in the regulation. Ajmal is now organising a committee to challenge this. He said,

Companies like migrant labour more because they are just working. The labourers from adjacent villages do not work for more than two-three months and they get tired and earn enough for pocket money and leave the job. But the migrant labour from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or West Bengal migrate to earn. They are not distracted and only focus on work. They are here to earn, so they are preferred. [B007]

There is a whole ecosystem then of middlemen or employment brokers from the local community in Bhiwandi who circulate fungible labour through the warehouses. Here fungible labour refers to a particular embodied quality – migrant worker, non-unionised, fit and able to do manual work, which makes them indistinguishable from each other and only focus on earning. There are three types of labourers – un/loading, floor managers, and lastly placing and sorting managers. Apart from these, there are also sweatshop labourers in some warehouses who produce the products that are part of the logistics supply chain – car covers, toothbrushes, packing boxes – you name it, they have it. The demand for these jobs, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, shows how each worker is interchangeable with others. These workers are kept in the informational periphery as they have very little access to information or rights, while information about them is also hidden from plain sight in the hundreds of WhatsApp lists administered by local brokers.

One locally elected official shared with us that migrant labour in Bhiwandi struggle like “slaves.” Although informality and precarity is also a feature of migrant labour in the powerloom sector, this was, however, seen as more craft-based with training and skills development on the job. In the warehousing sector, however, labour is dispensable and interchangeable, and the e-commerce companies are complicit in creating precarity.

A lot of these logistical parks have provided employment to the youth and given job but labour laws are not being implemented. But 95 percent of the people are paid less than minimum wages but I don’t want to touch that subject now because if I do that it will look anti-industry and people will not come to Bhiwandi. So I am letting them do that, settle down. Some companies have their own ethics but by the time it travels from USA, to Europe to India it changes completely and become Indianised. It is a huge concern area. But it is true that labour exploitation is huge and it’s an East India company kind of attitude by these multinationals. [B002]

Conclusions

In this paper, I have argued that urban studies scholarship needs to (re)position itself by paying attention to a logistical turn in the periphery. For this, we need to start rethinking urban studies from the periphery and then rethinking the periphery itself in a digital age. Peripheries are not just about informality or suburban sprawl; rather, peripheries are made through an uneven and unequal access to networked connectivity, as concentrated nodes of informational space emerge within longstanding structural disadvantages. As I have shown, logistics, digital infrastructures, and a changing political economy of technology are remaking the periphery in the global south. As the digital revolution takes root in the global south, the periphery in this context reflects a “spatial fix” of a global logistics network that is facilitated by informational access. Privileged information rests as much on a political technology of fungible land that makes it the ground zero of logistical territory as well as a ready supply of fungible labour that is required to constantly move goods, on-demand and in real-time. But the periphery is more. It is also re-emerging as a crucial site of regional futures as it gets increasingly positioned on global networks of territory, logistics and people.

I have also argued that a settler colonial logistics in the periphery is as much entrenched within local privileges as it is an external force of global capital. Settler coloniality works simultaneously through the regulatory practices and the intimate local networks of caste and ethnic privilege that enable warehouses to remain in the region as a permanent temporality. Settler colonial logistics require fungible land and labour, and in Bhiwandi, the ready availability of both on account of vast swathes of agricultural land and migrant workers makes it the hub of a “settled” logistics. Settler colonial logistics also work through the squeezing out of the traditional powerloom economy and the shifting of investment and interest towards warehousing as the future of the region.

This is what I have labelled as “informational periphery” – the paradoxical nature of informational flows, networks and stickiness in the urban and metropolitan peripheries of the global south. The informational periphery is located both materially and epistemologically in the intersection of multiple imaginaries of the urban and digital, speed and decay, settling and moving. The informational periphery is a paradox. The informational periphery is a particular product of a logistics turn in urbanisation that focuses on speedy, on-demand, real-time information for some while withholding information from others. On the one hand, the periphery is radically shifting the territorial focus of metropolitan regions towards enabling a logistics model, whereby “logistification” (Cavalier Citation2016) concentrates in declining industrial centres (such as Bhiwandi) to reinforce local privileges of caste, religion and ethnicity. On the other hand, it is produced by redlining the direction and flows of informational spaces. Digital transformations in the periphery deploy extractive technologies over people through the sedimentation of developmental delays, data deficits and information gaps. This has led to the production of fungible bodies and spaces which reflect what Simone has noted as the “surrounds” – “a space of insufficiency and incompletion” (Simone Citation2010, 40). The information periphery then is built upon a global informational economy where Castells has argued “the power of flows have become more important than the flows of power” (Castells Citation2011, 500).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the work done by Sheema Fatima, post-doctoral research fellow in the British Academy project, as well as the participants in Bhiwandi who have patiently answered our questions and extended their support towards this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Sepoy Mutiny is considered the first war of independence in India and was led by the Indian soldiers fighting in the British East India Company. Their aim was to reinstate the last Mughal Emperor as the ruler of the Indian subcontinent. The uprising was violently crushed by the East India Company, the last Mughal emperor sent to die in exile in Burma and India was declared as ruled by the British Crown thereafter.

References

- Basu, B. 2020. “Crisis in Bhiwandi Powerloom Sector.” Indian Textile Journal (Blog). 19 June 2020. https://indiantextilejournal.com/crisis-in-bhiwandi-powerloom-sector/.

- Bhagat, R. B. 2005. “Rural-Urban Classification and Municipal Governance in India.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 26 (1): 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0129-7619.2005.00204.x.

- Borah, Upamanyu. 2020. “BHIWANDI—India’s Centralised Stocking and Distribution Point | Cargo Connect.” 27 July 2020. http://www.cargoconnect.co.in/hub/bhiwandi-indias-centralised-stocking-and-distribution-point/.

- Caldeira, Teresa PR. 2017. “Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, Transversal Logics, and Politics in Cities of the Global South.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479.

- Castells, Manuel. 2011. The Rise of the Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cavalier, Jesse. 2016. The Rule of Logistics: Walmart and the Architecture of Fulfillment. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota University Press.

- Chan, Anita Say. 2013. Networking Peripheries: Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cowen, Deborah. 2014. The Deadly Life of Logistics. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749j.ctt7zw6vg.

- Cuppini, Niccolò, and Mattia Frapporti. 2018. “Logistics Genealogies: A Dialogue with Stefano Harney.” Social Text 36 (3): 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-6917802.

- Datta, Ayona. 2023. “The Digitalising State: Governing Digitalisation-as-Urbanisation in the Global South.” Progress in Human Geography 47 (1): 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221141798.

- Du, Yue. 2019. “Urbanizing the Periphery: Infrastructure Funding and Local Growth Coalition in China’s Peasant Relocation Programs.” Urban Geography 40 (9): 1231–1250. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1568811.

- Easterling, Keller. 2016. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London, UK: Verso.

- Elden, Stuart. 2010. “Land, Terrain, Territory.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510362603.

- Erman, Tahire, and Aslýhan Eken. 2004. “The “Other of the Other” and “Unregulated Territories” in the Urban Periphery: Gecekondu Violence in the 2000s with a Focus on the Esenler Case, Istanbul.” Cities 21 (1): 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2003.10.008.

- Furlong, Kathryn. 2021. “Geographies of Infrastructure II: Concrete, Cloud and Layered (in)Visibilities.” Progress in Human Geography 45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520923098.

- Gabrys, Jennifer. 2014. “Programming Environments: Environmentality and Citizen Sensing in the Smart City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (1): 30–48.

- Gururani, Shubhra, and Loraine Kennedy. 2021. “The Co-production of Space, Politics and Subjectivities in India’s Urban Peripheries.” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online]. 26, Online since 03 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.7365.

- Hernandez, Daniel Oviedo, and Helena Titheridge. 2016. “Mobilities of the Periphery: Informality, Access and Social Exclusion in the Urban Fringe in Colombia.” Journal of Transport Geography 55 (July): 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.12.004.

- Jordan, Tim. 2015. Information Politics. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Kanai, J Miguel, and Seth Schindler. 2019. “Peri-Urban Promises of Connectivity: Linking Project-Led Polycentrism to the Infrastructure Scramble.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51 (2): 302–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18763370.

- Keil, Roger. 2017. Suburban Planet: Making the World Urban from the Outside In. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Keith, Michael, and Andreza Aruska de Souza Santos. 2021. African Cities and Collaborative Futures: Urban Platforms and Metropolitan Logistics. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526155351

- Kohli, Atul. 2004. State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lyster, Clare. 2016. Learning from Logistics: How Networks Change Our Cities. Basel: Birkhauser.

- Mutter, Samuel. 2023. “Distribution, Dis-Sumption and Dis-Appointment: The Negative Geographies of City Logistics.” Progress in Human Geography 47 (1): 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221132563.

- Pieterse, Marius. 2019. “Where Is the Periphery Even? Capturing Urban Marginality in South African Human Rights Law.” Urban Studies 56 (6): 1182–1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018755067.

- Porter, Libby, and Oren Yiftachel. 2019. “Urbanizing Settler-Colonial Studies: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Settler Colonial Studies 9 (2): 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2017.1409394.

- Shaban, Abdul, Ayona Datta, and Sheema Fatima. 2023. “Overlapping Marginalities: Digital Education and Muslim Female Students in Bhiwandi.” Economic & Political Weekly 58 (29), https://www.epw.in/journal/2023/29/special-articles/overlapping-marginalities.html.

- Shaw, Joe, and Mark Graham. 2017. “An Informational Right to the City? Code, Content, Control, and the Urbanization of Information.” Antipode. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12312.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2010. City Life from Jakarta to Dakar: Movements at the Crossroads. London, UK: Routledge.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2022. The Surrounds: Urban Life Within and Beyond Capture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sood, Ashima. 2021. “The Speculative Frontier: Real Estate, Governance and Occupancy on the Metropolitan Periphery.” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 26. https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.7204.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2002. “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance.” Archival Science 2 (1-2): 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2009. “Critical Theory and ‘Gray Space’: Mobilization of the Colonized.” City 13 (2-3): 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902982227.

- Zins, Chaim. 2007. “Conceptual Approaches for Defining Data, Information, and Knowledge.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58 (4): 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20508.