ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to analyse the dynamics of violence against educational facilities and students in northwest Nigeria, specifically carried out by bandits. By employing qualitative and quantitative research methodologies, a comprehensive understanding of these attacks is sought. The paper notes schools and students are disproportionately targeted by bandits and are becoming vulnerable for various reasons. These include pervasive failure of governance, diminishing presence of the state in maintaining order, general lack of protection by the government, perceived weakness of students to mount resistance, and bandits’ propensity for illicit profit through ransom payment by victims. These affect the students in six principal ways: loss of lives, increasing burden of fear, rise in sexually transmitted diseases, decreasing enrolment in school, abandonment of educational facilities and forced displacement. In the milieu of banditry in Nigeria’s northwest, it is crucial to adopt the peacebuilding approach and implement security sector reform, safe school initiatives, development, social support and strategic health care delivery to victims in order to successfully eliminate, neutralise, and disrupt (END) attacks by bandits targeting educational facilities.

Everyone is worried about the spate of killing, kidnapping, rape, torturing and maiming in our communities. We are also very nervous whenever we are in school teaching or conducting other activities because we know that bandits could attack at any hour. We are teaching and at the same time looking through the windows, and listening to the noises in the distance so as to be sure they are not bandits attacking our schools. Teaching and learning have become very uninteresting activities nowadays. We have all lost passion in this occupation. We are only doing it because we have to. Because we have no alternative.Footnote1

Introduction

The rise of contemporary research on banditry can be attributed to the pioneering study by Eric Hobsbawm, particularly his exploration of social banditry. Hobsbawm's influential thesis contends that the collapse of state power and governance in most regions worldwide, combined with the diminishing capability of even well-established states to uphold certain normative framework of law and security governance attained in preceding centuries, it is crucial to recognise the historical, economic, political and sociological factors that facilitate the thriving of endemic banditry.Footnote2 Banditry manifests through criminal acts such as livestock theft, abduction for ransom, armed robbery, drug misuse, arson, sexual assault, and the gruesome massacre of individuals residing in agrarian communities, through the use of small and sophisticated weaponry.Footnote3 These bandits are commonly regarded as social outcasts, and individuals with inclination for violent crime who operate outside the law. They have no fixed abode or destination, instead they are constantly roaming through the forests and mountains in order to evade detection, identification, and arrest by law enforcement authorities and security forces.Footnote4

Banditry has a long history and can be traced back to different periods and regions. In Latin America, for instance, banditry was prevalent during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and served as a means of political rebellion and economic survival in times of limited opportunities. Bandits targeted both individuals and possessions, driven primarily by personal gain. Interestingly, local elites sometimes provided more support to these outlaws than the common people, blurring the boundaries of social class. As a result, outlawed networks emerged, engaging in criminal activities for various motives.Footnote5 Hobsbawm asserts that through such actions, banditry poses a simultaneous challenge to the economic, social, and political structure by openly opposing those in authority, the legal system, and the control of resources.Footnote6

Over the past ten years, the study of banditry has gained significant traction as an academic discipline in Nigeria. Through captivating, rigorous, and essential analysis, various schools of thought have emerged to theorise the origin and progression of banditry in Nigeria’s northwest. As of December 2022, the incessant violence by bandits has caused the displacement of 1,087,875 people in rural communities.Footnote7 Over the course of 2010 to May 2023, the number of deaths linked to banditry amounted to approximately 13,485.Footnote8 These also include violence against educational facilities and students. However, the sheer conversations about the impact of banditry on education are heavily concentrated in media reports. There is a notable scarcity of empirical studies that have sought to provide a scholarly analysis on this dimension of bandits’ attacks in Nigeria’s northwest. In this context, this study posits that this dearth of research has impeded a comprehensive understanding of the challenge. Hence, this research endeavours to bridge this gap in the existing literature by drawing upon series of in-depth qualitative interviews were carried out with teachers, education officials, residents, victims, bandits, and repentant bandits (defectors) in the study area. The selected research participants were specifically inquired about the undercurrents of banditry prevailing in their respective villages. Questions raised include: What is the nature of violence against educational facilities and students in northwest Nigeria? What are the conditions in which the violence against educational facilities and students is taking place? What is the motivation for the strategic violence against education facilities by bandits in the conflict setting? What are the real and potential impacts of violence against educational facilities and students in the communities? Are there possibilities for mitigation and support to ameliorate the lingering trauma experienced by the victims of violence against educational facilities in northwest Nigeria?

Materials and methods

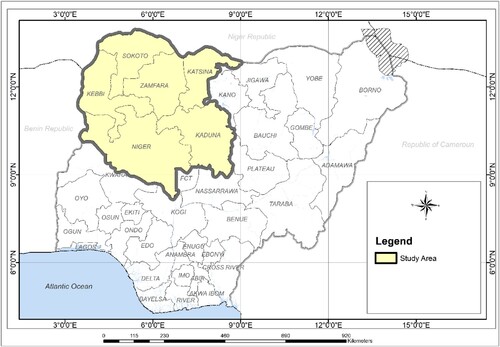

The research approach employed a combination of primary and secondary data sources. The investigation incorporated a comprehensive literature review alongside the information regarding the attacks by bandits extracted from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. Fieldwork was carried out in the locations and communities affected by banditry in Nigeria’s northwest from February 9th to September 16th, 2023. This study specifically concentrated on the geographical and historical northwest of Nigeria, encompassing Zamfara, Sokoto, Niger, Kebbi, Katsina and Kaduna states, as illustrated in . The respondents were selected to foster differing views so as to ensure that the discussions capture the full range of scale, experiences and explanations on the subject of banditry and violent attacks on schools.

Figure 1. Nigeria’s map indicating Kebbi, Zamfara, Sokoto, Niger, Katsina and Kaduna states. Source: Authors’ design through Google Earth software.

Selecting respondents for this study involved a thoughtful and purposeful process to ensure that the chosen participants can provide rich and meaningful insights related to the research. To determine and select the population that is most relevant to this study, demographic characteristics and experiences that align with the study were considered. These include factors such as age, gender, occupation, and specific experiences of bandits and defectors. Purposive sampling technique was adopted in selecting participants who can provide in-depth insights into the research topic through specific criteria such as expertise, knowledge, or unique experiences relevant to the study. Thus, teachers, parents and other community members were selected. Author also adapted the sampling strategy as the field work progressed. This became pivotal as iterative nature of the qualitative research required adjustments to the sample based on emerging insights and themes. In this regard some teachers advised the author and field assistant to consider interviewing security and law enforcement officials in the communities. This was implemented until the field work reached data saturation point, where additional interviews were unlikely to provide substantially new information. Author and field assistant ensured that the selection process adhered to ethical guidelines, respect for participant autonomy, and confidentiality.

A total of 32 respondents drawn from 18 Local Government Areas (LGAs), and comprising teachers, bandits, community residents, and defectors were interviewed in 30 villages and towns (see ). In order to ensure the dependability, vailidity, and impartiality of data gathering and examination, the interviews were conducted in a comprehensive manner. The research questions were further refined, allowing for a more thorough investigation. A diverse set of independent sources was utilised to gather evidence, employing different approaches. These approaches included comparing and triangulating oral testimonies with existing literature and quantitative research findings. Participants agreed to be quoted and referenced anonymously to maintain the confidentiality of the research.

Table 1. Communities selected and interviewed participants.

Furthermore, ACLED gathers quantitative data from a mix of primary and secondary outlets on acts of violence occurring within countries, including the actions of armed groups. ACLED coders compile information from news sources – both international and local using different records, making use of media channels spanning local, national, and international spheres to chronicle violent incidents on a global scale. This data is then organised by day, site, and the persons or groups involved, and presented in an excel file. Subsequently, this excel file is modified and converted into a.csv file for utilisation in Arcmap. After assigning ‘x’ and ‘y’ values to the.csv file, it is transformed into a shapefile. This shapefile is then imported into the Arcmap environment as a layer. The scope, concentration, and spatial pattern of bandit attacks are determined and analysed by referencing the map coordinates extracted from the ACLED excel file. Moreover, specific incidents related to key indicators of banditry, such as ransom kidnappings, violent killings of students in rural communities, sexual violence against schoolgirls by bandits, and the unlawful possession and utilisation of firearms by bandits in school settings, are extracted for further data analysis. This methodology is of utmost importance as it significantly contributes to academic and policy works by providing a first-hand examination of the undercurrents of banditry and plotting incidents of violence against educational facilities and students by bandits in northwest Nigeria. Mapping cases of violence by bandits can serve as a valuable tool for the law enforcement and security agencies to comprehend the variations in the spatial distribution, extent, and intensity of attacks, as well as to identify alternative strategic responses. Additionally, this methodology establishes a stronger connection between theory and practice, offering a scientific understanding of the subject of banditry.

Theoretical perspectives

At the fundamental level, the UNESCO’s framework on protecting education from attack provides a useful model for understanding violence against schools by suggesting a broader view. Among its various points, the report underscores the significance of assessing how opportunity and the capabilities of attackers influence specific types of attacks and depending on the target, geographical location, perpetrator, motive, political and legal framework, or the dynamics of the conflict within a particular context.Footnote9 These indications serve to illustrate that the origins of targeted violence surpass the scope of an individual perpetrator, and are instead influenced by wider community and societal factors that facilitate the proliferation of violence in all its manifestations. Therefore, in building the arguments that explain the attacks on schools in armed conflict, scholars, policy makers and advocates must first understand the wider dynamics of the evolution and operations of armed groups.

According to the theory of social disorganisation, the breakdown of informal social controls in disorganised communities or societies lacking collective efficacy creates an environment conducive to the emergence of criminal and violent cultures. In current scholarly debates on violent crime, such places are often characterised as ungoverned spaces. The proponents of ungoverned spaces basically argue that almost all countries have remote areas within which formal governments do not matter much. The notion of ungoverned spaces is gaining prominence as a critical threat to governments and their interests on a global scale. These spaces are frequently equated with failed states or territories that face challenges in effectually asserting their sovereign authority. The ungoverned space theory suggests that violent actors often emerge where there is a lack of effective authorities and institutions to stop them.Footnote10 In Africa, this situation typically arises as a result of a capacity constraint. This is because, even when the states enact laws to engender protection and welfare of citizens, they may not have the resources to guarantee their enforcement.Footnote11 However, study by Taylor asserts that Ungoverned areas have the potential to pose a security risk, yet armed groups are seldom the culprits behind their formation. Rather, the reason for their emergence is poor governance that limit the quality of life and deprives the population.Footnote12 Routine activity theory, developed by Cohen and Felson (1979), emphasises that crime occurs when three elements converge: (1) a motivated offender, (2) a suitable target, and (3) the absence of a capable guardian.

Gaining a thorough understanding of the motivations behind attacks on different targets is a fundamental in safeguarding educational institutions from being targeted by armed factions. Existing research indicates that the motives for such attacks can be categorised differently. In certain cases, attacks on schools are driven by religious extremism and socio-cultural tendencies towards violence. For example, in Thailand, Muslim separatist movement is active in the provinces situated in the southern part of the country. Schools are frequently the focus of their attacks, resulting in harm to students and teachers due to the symbolic significance of schools in villages, representing the government's authority that they oppose. Moreover, schools are perceived as easier targets compared to others. The Taliban's gender-driven motives are clearly discernible in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as they resort to issuing formal and written threats to enforce their agenda of closing girls’ schools or impeding educational opportunities for girls.Footnote13 Other academics additionally observe that the occurrence of violence targeting educational institutions is partially attributed to the significant influence exerted by global networks like al-Qaida and IS, which actively promote such acts. Furthermore, terrorist affiliates acquire knowledge from one another and perceive it as an effective means to garner global or regional attention for their cause, coerce governments into compliance, or suppress communities and ideas, such as education. A second pattern noted by scholars is that groups that carry out attacks on schools tend to possess some common attributes. They are often in alliances with other armed groups, and these alliances offer additional resources to organisations, which are crucial for carrying out extensive attacks.Footnote14

Another study conducted in Nigeria's northeast indicates that targeting school children has proven to be an effective strategy for negotiating the release of detained members of terrorist groups. Additionally, this approach provides an opportunity for these groups to demand substantial ransoms, which they can then use to purchase weapons and finance their operations. Furthermore, armed groups are also interested in children as a means to achieve visibility both locally and internationally, showcasing their strength and seeking collaborations with similar organisations. Moreover, children hold utilitarian value for these terrorist groups, as they can be deployed to carry out various tasks such as planting explosives, acting as human shields or suicide bombers, and gathering intelligence without arousing suspicion. Lastly, the attacks on schools align with the central ideology driving terrorism in the countries of the Lake Chad Basin, which revolves around opposition to Western education. The increased targeting of schools serves the purpose of creating insecurity and an unfavourable environment for teaching and learning in the region. Additionally, girls are specifically targeted by these armed groups for sexual exploitation, with abducted girls often being subjected to rape or forced into marriages within their camps.Footnote15 the reason behind terrorists targeting educational institutions lies in the fact that these establishments are considered softer targets, where a considerable number of people come together, making them susceptible to potential mass casualties.Footnote16 Within the scope of this study, the aforementioned theories are relevant in two specific areas – the evolution of banditry and the vulnerability of educational facilities to bandits’ attacks. The subsequent sections of this study will highlight, analyse, and contextualise the findings within these theories.

Evolution of banditry in northwest Nigeria

Over the years, the phenomenon of banditry in Nigeria's northwest has undergone a transformative process, and has given rise to four distinct lines of argument.Footnote17 The first line of argument proposes that the violent activities of bandits in this region can be traced back to its historical context, particularly in relation to organised crime on an international scale. The earliest notable account of attack by bandits in the area occurred in 1901, prompting both French and British colonial establishments to express their deep dismay at the high number of traders who fell victim to bandits. Within the context of this well-documented event, an astonishing number of 12,000 camels, carrying a diverse range of grains, were deliberately targeted by bandits. Their valuable cargo was stolen during their journey from western part of Hausaland to the region of Tahoua in contemporary Niger. Estimate by the French authorities revealed that the stolen property holds a collective value of £165,000, and the devastating incident claimed the lives of 210 traders. Although this particular incident stands out as a significant bandit operation within the French colonial experience in Niger, it is important to acknowledge that there were also several minor incidents during that period, as evidenced by historical accounts.Footnote18

Placed in a recent historical context, the second line of argument delves into the resurgence of banditry in Nigeria’s northwest. This resurgence can be traced back to an incident in Chilin, Dan-Sadau Emirate of Zamfara state, where the brutal killing of Alhaji Isshe, a revered Fulani leader, occurred. On the 16th of August, 2012, Alhaji Isshe was murdered by the Yan-Sa-Kai vigilante group, who accused him of sheltering and aiding herders engaging in cattle rustling. In response to his death, the followers of Alhaji Isshe mobilised combatants and contacted affiliated gangs for the purpose of retaliatory attacks. As time passed, these gangs transformed into bandits, growing in numbers, acquiring weapons, and strengthening their connections in 2013. Furthermore, by 2016, there was a noticeable increase in diversity and transnational involvement, as they began to attract individuals from nearby nations like Chad, Mali and Niger. Notably, this included Tuaregs who had connections to Sahelian rebels.Footnote19 The motivation observed among bandits is effectively positioned within the academic argument, suggesting that individuals who have a common ethnicity and national identity are more likely to be part of organised crime groups and engage in violent acts within the same geographical area. This finding aligns with the concept that recruiting individuals from a limited region with the same ethnicity or nationality fosters collaboration among armed groups.Footnote20 Over time, banditry has evolved from its basic and isolated origins into a multifaceted and rapidly expanding security menace that transcends national boundaries. Nevertheless, certain individuals involved in the conflict zone believe that achieving lasting peace in the northwest region may prove challenging unless the government adequately addresses their concerns. The subsequent excerpt from an interview with a prominent bandit leader offers a unique perspective.

… For over 40 years, Fulani people are being attacked by other people and the government has never been serious about ending the senseless attacks on the Fulani all over the country. This is the reason many of us have taken up arms in order to defend ourselves. I am about 42 years now. This thing has been happening long before I was born … We will take revenge for all the killings and destruction Fulanis have experienced. Let them prepare for 100 years of killing, torturing, kidnapping and terror. Our children will continue where we stop. That is exactly what our attackers have done against us.Footnote21

I joined banditry through my friend whose father was butchered by people believed to be farmers. Few days before his death some of his cattle transgressed to a nearby farm as he was grazing his animals. The animals destroyed very few crops. My friend's father demanded that the damage should be quantified in monetary value so that he would pay. The owner said he didn't want compensation but rather would take action he deemed fit. One morning as he was grazing his animals in the bush, the farmer and his friend attacked the man and cut off his neck vein with a knife. Since then my friend and his siblings vowed to take the worst retaliation against the entire farming community here in Gundumi and Kamarawa communities in Isa. One of his children was my friend and he invited [me] to help him fulfil his vows. This case is one out of thousands. Similar incidents have happened to so many of us.Footnote22

… We were seriously facing economic difficulties because there were no jobs apart from hard labour on the farm. You could be hired to work on the farm for the whole day for just ₦1000 [$1.4 USD] or even less. It was not enough to live on less than ₦1000 a day and that could only be gotten after 12 hours work on farm. It was because of that extreme poverty that we formed our own bandit group and started attacking people. Our group developed and became one of the most dangerous bandits groups in the whole of Birnin Gwari LGA. We did all the atrocities on the people. We abducted many children and their mothers and collected millions of naira as ransom in the 7 years I took as bandit.Footnote23

We started [banditry] with a single local gun, but within a very short period of time we acquired about 34 semi-automatic rifles. Arms from various parts of the country are reaching us through our arms traffickers and couriers. Most of the arms we used when I was in banditry were gotten from one arms dealer in Nasarawa state. He used to bring foreign arms to many bandits, not only our group. He said he was getting the arms from another dealer in Anambra. The AK 47 is the preferred type of weapon by bandits. Some groups have very few and it's often circulated among the members of a group or given to a leader all the time.Footnote26

Banditry is worse in border communities like Jibia due to the influx of people and weapons from outside. Bandits get their AK 47 from Niger and the original sources of those arms are usually Libyan desert and Mali. This is usually the link between Nigerian bandits and bandits from Niger. It happens at the level of arms trafficking in addition to the transborder linkages.Footnote27

Why schools and students are increasingly targeted by bandits

The strategic targeting of educational facilities and students should be viewed and analysed in the context of pervasive failure of governance and diminishing presence of government which enable an overall surge in violence against civilians, regardless of their demographic characteristics in Nigeria’s northwest. This has assumed a complex dimension in remote villages and towns where state security agents are virtually non-existent and surveillance remains very poor. Security official in such areas confirmed the situation has degenerated due to negligence by the government.

Schools in most of our communities are not properly protected, guarded and secured. Long before now, security agents have been advising government to safeguard our schools because intelligence reports have shown that bandits would attack schools in many of our communities. There was a time a joint patrol between armed corps of NSCDC, police, vigilantes and army were organized to be patrolling schools in Isa communities. We requested additional patrol vehicles and regular fueling from the local government. The chairman promised his administration's support, but at the end of it they have not given us the vehicle and other kinds of assistance. That is how that operation collapsed.Footnote30

Banditry in Riba and in other parts of Danko-Wasagu LGA is dreadful. Most of those bandits come from the bush neighboring Bukkuyum LGA in Zamfara State. This is a very dangerous forest because it harbors all the notorious bandits that have been attacking our communities in Danko-Wasagu, Sakaba, Gumi, Bukkuyum and other areas in Kebbi and Zamfara States.Footnote34

The bandits also carry out mass attack and kidnapping of students to foster a climate of fear and propaganda is deliberately. The systematic assault on educational institutions and the abduction of countless students are tactics employed to depict bandits as heartless, thereby pressuring individuals to remain submissive and encouraging innocent civilians to comply with the bandits’ demands both prior to and following their attacks.Footnote36 The large-scale kidnapping incident captures significant media spotlight, painting the government as incapable and emboldening the bandits.Footnote37 According to a teacher at Kandarawa village in Bakori LGA of Katsina state, the prevailing fear hinders the reporting of the horrifying cases to the authorities.

Students and teachers are the victims of banditry in this area. Many abductions are not reported at all. Even last month, 11 years old child was abducted by bandits on his way to the school. Students are the worst victims of the attacks compared to their teachers and other school workers. Attacking students tends to generate more outcry and panic among people, perhaps that is why students are often targeted.Footnote38

Real and potential impacts of banditry on education

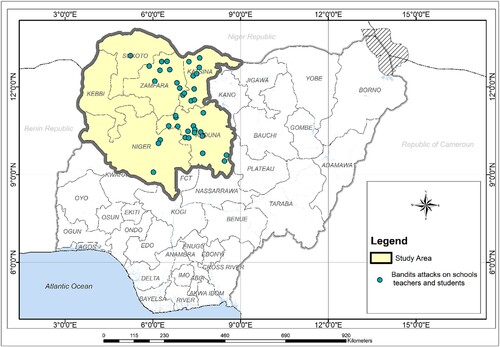

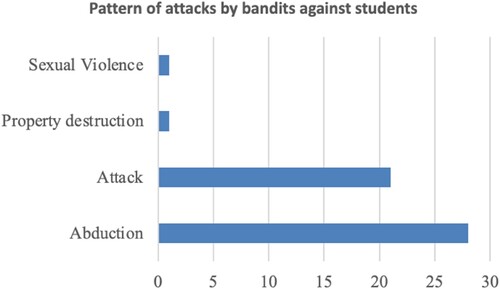

Education in Nigeria's northwest has been greatly affected due to the resurgence of bandits and their continued access to illegal weaponry. The destructive activities carried out by these criminals, in conjunction with the continuous extension of areas embroiled in conflicts, pose a significant threat to the lives of students residing in this region (see ). Attacks and kidnapping for ransom by bandits affect learning and students in six principal ways. They are: loss of lives, increasing burden of fear, rise in sexually transmitted diseases, decreasing enrolment in school, abandonment of educational facilities and forced displacement.

Figure 2. Map of northwest displaying the spatial spread of bandits’ attacks on schools. Source: Authors’ collection from ACLED produced through Arcmap.

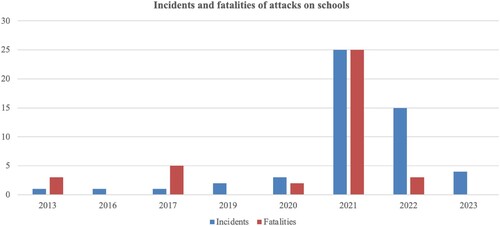

According to the ACLED project, violence against educational facilities and students by the bandits has continued on the upward trend since 2020. From 2013 to 2019, attacks against students and educational facilities by bandits were intermittent and surged to 25 incidents and 25 fatalities in 2021. There were 15 reported incidents and 3 fatalities in 2022. A total of 51 persons have been killed as a result of attacks against schools and students from 2013 to 19 May 2023 (see ). ACLED's data collection process relies heavily on information provided by local groups and media reports. However, it is important to acknowledge that there may be other significant incidents that go unrecorded.

Figure 3. Incidents and fatalities of attacks by bandits in the study area (2013–May 2023). Source: Authors’ compilation from ACLED.

To buttress the severity of violence against educational facilities and students by bandits in the study area, one teacher at Gatawa in Sabon-Birni LGA of Sokoto state highlighted the complex effect of violent attacks by bandits on students in northwest Nigeria.

Banditry has done more damage to our education than what is being reported. Some communities have closed schools for years. Children have forgotten when last they were taught in classes. Government doesn't care. It will be difficult for the north to bounce back in the next 20 years. In major towns and cities, there are many out-of-school children roaming our streets. Banditry has forced many of them out of schools.Footnote39

Figure 4. Pattern of attacks against students by bandits across the study area (2013–May 2023). Source: Authors’ compilation from ACLED.

Bandits have killed and abducted so many school children in this community. There are 7 pupils that were kidnapped on their way to this primary school about 2 years back and still not released after the payment of ransom. Attendance by students is very minimal especially after every new attack on people and communities. Girl child education is stifled completely in our communities. The long-term effects will be difficult to live with. Many of our people don't allow their girls to be enrolled in schools. This is why there is a staggering number of out-of-school girls in this community, and the scariest thing is that, solution to banditry is not in sight.Footnote41

Bandits are merciless. They are wicked. There are reported instances of sexual molestation involving minor. There was a 13 year old girl raped by bandits and was tested HIV positive after she was released. These are some of abuses that children including students abducted went through.Footnote43

Payment of ransom is not what parents lament about when their children are kidnapped. Money can be raised by selling some assets or by fundraising from family and friends. But no one can do anything about the possible abuse that your child will be subjected to by bandits. There is tendency for rape. If that occurs, the physical, mental, psychological and emotional health of the child can be jeopardized. Children are sometimes brutalized with bruises on their bodies after release.Footnote45

Girl child education has been seriously affected by banditry in all our communities. Girls have resorted to selling Dawo, Fura, Aya, Gyada (all local foods) on the streets instead of going to schools. About 70% of school age girls are out of schools in this community. Insecurity in the region has compounded the problem.Footnote46

Strategic options for resilience

Addressing the challenges of attack against educational facilities and students must take cognisance of the enablers and drivers of banditry. Ending these challenges durably in northwest Nigeria would require five strategies – security sector reform, development, peacebuilding approach, safe school initiatives, social support and strategic health care delivery to victims. The first step in promoting harmonious coexistence entails nurturing and promoting mutually agreed consensus between herdsmen and sedentary farmers – communities residing in the countryside. Research participants stress the importance of addressing the historical and deep-seated grievances spanning multiple generations that have defined the relationship between the Hausa and Fulani, in order to establish a harmonious coexistence.Footnote48 Some defectors additionally hinted at considering the option of transitional justice through re-evaluating the amnesty initiative for eager and would-be deserters. They confirmed that a majority of the outlaws might be inclined to surrender their weapons and embrace tranquility in an environment where they are guaranteed the government's safeguard.Footnote49

To effectively address the challenge of banditry, it is imperative to prioritise securing the forest areas and other unregulated spaces that serve as sanctuaries for the armed groups. This approach forms an integral part of the holistic solutions that can be implemented by the government by partnering with the affected communities.Footnote50 To effectively combat banditry in the northwest, it is imperative to recognise the indispensability of implementing comprehensive security sector reform throughout the nation. Hence, it is crucial to review and amend extensively, the section 214 of Nigeria’s 1999 constitution that currently concentrates the exercise of policing and security power with the central government. This amendment would enable the establishment of a decentralised policing system that focuses on local communities and their specific needs. By involving communities in the human, organisational, and operational resources aspects of policing, we can ensure a more effective and efficient security apparatus that safeguards the people.Footnote51 Strengthening existing customs and immigration checks through the deployment of electronic border surveillance systems would additionally bolster security at unmanned border corridors.Footnote52

Moreover, it is crucial that the central and subnational governments prioritise targeted socio-economic programmes to mitigate the impact of poverty and limited opportunities on the youth who are being recruited into banditry. A significant allocation of resources towards education, infrastructure, agriculture, and other avenues to enhance youth employment is indispensable in addressing these challenges. The government can revitalise the Safe School Initiative (SSI) programme, which was launched by the federal government in 2021, to effectively rebuild, rehabilitate, and restore a conducive learning environment.Footnote53 For SSI to be truly effective, it is essential to place the communities at the heart of its execution. These communities possess invaluable knowledge, situational awareness about the dynamics of insecurity in their specific areas, making them the most suitable candidates to devise practical solutions. By leveraging their local relationships and community agency, they can effectively advocate for and monitor schools, ensuring they remain safe and peaceful environments. To facilitate this initiative, it is recommended that the federal government redirects the mandate of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) to take the lead in providing foolproof security for schools, as directed.

Lastly, the state must update its current approach to countering armed banditry to include preventive methods of psychotherapy and primary health care supports to female students who have become victims of rape by bandits in the states. The pragmatic options here would first involve the acknowledgment of the severity of this problem in the armed conflict zones where bandits are wreaking havoc in vulnerable schools. Then, both federal and sub national governments can identify and resource safe spaces where victims of sexual violence by bandits can safely report and seek social, medical and psychological support.

Conclusion

The present study presents compelling evidence regarding the progression of banditry and the changing patterns of violence directed towards educational institutions and students in northwest Nigeria. By gathering firsthand accounts from teachers, residents, bandits, and their defectors, this research sheds light on the underlying factors and facilitators of banditry. Furthermore, it makes a substantial contribution to our understanding by examining the actual and potential consequences of violence against educational facilities and students, as well as delving into the reasons behind the escalating targeting of these institutions by bandits. The study presents significant findings that contribute to the existing body of knowledge and offers recommendations for policy actions to address the problem of banditry and the associated violence against educational facilities and students in northwest Nigeria. The paper posits that a multi-faceted solution is essential. The paper concludes that in order to effectively combat the strategic violence carried out by bandits in northwest Nigeria, it is imperative to adopt a peacebuilding approach and implement security sector reform, safe school initiatives, development, social support and strategic health care delivery to victims.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Oluwole Ojewale

Oluwole Ojewale PhD is the ENACT Regional Organised Crime Observatory Coordinator for Central Africa at the Institute for Security Studies in Dakar, Senegal. His research interests span transnational organised crime, urban governance, security, conflict and resilience in Africa. At various times, he has undertaken studies and stakeholders’ engagements in Cameroon, Chad, Central Africa Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, São Tomé and Senegal. He is the co-author of ‘Urbanization and Crime in Nigeria’ (Palgrave, 2019) – adjudged as the first comprehensive book on the intersection between urbanisation and crime in Nigeria. His public policy and advocacy commentaries have been published in Harvard Bulletin, ISS Today, The Brookings Institution, The Africa Report, Africa at LSE, and The Conversation. He features frequently as a public affairs analyst on CNN, FRANCE24, BBC, Newzroom Afrika, TVC, News Central and CGTN among others.

Notes

1 Interview with a primary school teacher at Bargaja, Isa LGA, Sokoto state on May 18, 2023.

2 Hobsbawm, Bandits.

3 Uche and Chijioke, ‘Nigeria: Rural Banditry and Community Resilience’.

4 Ojewale, ‘Theorising and Illustrating Plural Policing Models’.

5 Slatta, ‘Banditry as Political Participation’.

6 Hobsbawm, Bandits.

7 ReliefWeb, ‘Displacement Tracking Matrix’.

8 Ojewale and Sadiq, ‘Why Nigeria’s Bandits Are Recruiting Women’.

9 UNESCO, ‘Protecting Education from Attack’.

10 Clunan and Trinkunas, Ungoverned Spaces: Alternatives to State Authority.

11 Whelan, ‘Africa’s Ungoverned Space’.

12 Taylor, ‘Thoughts on the Nature and Consequences’.

13 UNESCO, ‘Education Under Attack’.

14 Phillips, ‘Why Schoolchildren are Regularly Being Targeted’.

15 Onapajo, ‘Why Children are Prime Targets’.

16 Naveed, ‘Why Terrorists Attack Education’.

17 Ojewale, ‘The Bandits’ World’.

18 Rufai, ‘Cattle Rustling and Armed Banditry’.

19 Auwal, ‘How Banditry Started in Zamfara’.

20 Campana and Varese, ‘The Determinants of Group Membership’.

21 KII with a battlefield bandit in in Gundumi, Isa Local Government Area of Sokoto State on July 18, 2023.

22 KII with a battlefield in Gundumi, Isa Local Government Area, Sokoto State on July 18, 2023.

23 KII with a former bandit in Sabon Layi, Birnin-Gwari Local Government Area of Kaduna State on July 9, 2023.

24 National Bureau of Statistics, ‘Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index’.

25 Ojewale, ‘Rising Insecurity in Northwest Nigeria’.

26 KII with a former bandit in Sabon Layi, Birnin-Gwari Local Government Area of Kaduna State on July 9, 2023.

27 KII with a former bandit in Bugaje, Jibia Local Government Area of Katsina state on July 13, 2023.

28 Yenwong-Fai, ‘The Nigerian Militant Islamic Movement’.

29 Ojewale, ‘Theorising and Illustrating Plural Policing’.

30 Interview with a senior officer at NSCDC Divisional Office, Isa LGA, Sokoto State on May 25, 2023.

31 Abdullahi, ‘Seized for Pleasure’.

32 Interview with a teacher at Garin Haladu, Birnin-Magaji, Zamfara state on May 13, 2023.

33 Interview with Police officer in Zurmi, Zamfara State on March 13, 2023.

34 Interview with the official of LGEA office at Riba, Danko-Wasagu LGA of Kebbi state on May 20, 2023.

35 Interview with a teacher at Nasarawa Mai-Layi in Birnin-MagajiLGA of Zamfara state on May 13, 2023.

36 KII with a defector in Allawa, Shirioro LGA, Niger state on July 4, 2023.

37 KII with a defector in Tagina, Rafi LGA, Niger state on July 6, 2023.

38 Interview granted by a teacher at Kandarawa in Bakori Local Government Area of Katsina state on May 9, 2023.

39 Interview granted by a teacher at Gatawa in Sabon-Birni Local Governemnt Area of Sokoto state on May 17, 2023.

40 Winsor and Bwala, ‘Hundreds of Nigerian Schoolgirls’.

41 Interview with a teacher at Kandarawa Primary School in Bakori, Katsina on May 9, 2023.

42 Mohammed, ‘Sex for Protection’; Ewepu, ‘Horror in Sokoto, Niger, Kaduna’; Oluwasanjo, ‘We Now Farm for Bandits’.

43 Interview with a Teacher at Kandarawa Primary School in Bakori, Katsina on May 9, 2023.

44 Center for Civilians in Conflict, ‘Nigeria Needs to Do More; Ewepu, ‘“I’m in a State of Shock”’.

45 Interview with a member of Parents and Teachers Association at Gatawa, in Sabon-Birni LGA of Sokoto state on May 17, 2023.

46 Interview with a primary school headmaster at Gatakawa in Kankara area of Katsina state on May 10, 2023.

47 Interview with a teacher at Nasarawa Mai-Layi, Birnin-Magaji Local Government Area of Zamfara state on May 17, 2023; Interview with a Teacher at Gatawa in Sabon-Birni LGA of Sokoto state on May 17, 2023.

48 Interview with a former bandit defector in Tagina, Rafi LGA, Niger State on July 6, 2023.

49 Interview with a former bandit in Bugaje, Jibia Local Government Area of Katsina state on July 13, 2023.

50 Interview with former bandit in Jere, Kagarko Local Government Area of Kaduna State on July 10, 2023.

51 Interview with a former bandit in Dansadau, Birnin-Magaji Local Government Area of, Zamfara State on July 14, 2023.

52 Interview with a former bandit in Allawa, Shiroro Local Government Area of Niger State on July 4, 2023.

53 Federal Ministry of education, ‘Minimum Standards for Safe School’.

Bibliography

- Abdullahi, M. ‘Seized for Pleasure: The Tragic Plight of Girls, Women Abducted by Bandits’. 2022. https://www.thecable.ng/seized-for-pleasure-the-tragic-plight-of-girls-women-abducted-by-bandits-in-niger.

- Aina, F., J. Ojo, and S. Oyewole. ‘Shock and Awe: Military Response to Armed Banditry and the Prospects of Internal Security Operations in Northwest Nigeria’. African Security Review 32, no. 4 (2023): 440–57. doi:10.1080/10246029.2023.2246432.

- Auwal, A. ‘How Banditry Started in Zamfara’. 2021. https://dailytrust.com/how-banditry-started-in-zamfara/.

- Campana, P., and F. Varese. ‘The Determinants of Group Membership in Organized Crime in the UK: A Network Study’. Global Crime 23, no. 1 (2020): 5–22. doi:10.1080/17440572.2022.2042261.

- Center for Civilians in Conflict. ‘Nigeria Needs to Do More to Prevent & Respond to Conflict-Related Sexual Violence’. 2023. https://civiliansinconflict.org/blog/nigeria-needs-to-do- more-to-prevent-respond-to-conflict-related-sexual-violence/.

- Clunan, A., and H. Trinkunas. Ungoverned Spaces: Alternatives to State Authority in an Era of Softened Sovereignty. Stanford: Stanford Security Studies, 2010.

- Ewepu, G. ‘Horror in Sokoto, Niger, Kaduna: “Bandits Kill Farmers, Seize Survivors” Harvest, Turn Abducted Women into Sex Slaves’. 2022. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2022/02/horror-in-sokoto-niger-kaduna-bandits-kill-farmers-seize-survivors-harvest-turn-abducted-women-into-sex-slaves/.

- Ewepu, G. ‘“I’m in a State of Shock”, Says Father of Girl Raped Multiple Times by Bandits’. 2020. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/12/im-in-a-state-of-shock-says-father-of-girl-raped-multiple-times-by-bandits/.

- Federal Ministry of education. ‘Minimum Standards for Safe School’. 2021. https://education.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Minimum-Standards-for-Safe-Schools.pdf.

- Hobsbawm, E. Bandits. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2000.

- Mohammed, I. ‘Sex for Protection: Travails of Women, Girls in Banditry-Torn North Western Sokoto State’. September 23, 2023. https://wikkitimes.com/sex-for-protection-travails-of-women-girls-in-banditry-torn-north-western-sokoto-state/.

- National Bureau of Statistics. ‘Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index’. 2022. https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/pdfuploads/nigeria%20multidimensional%20poverty%2 0index%20survey%20results%202022.pdf.

- Naveed, H. ‘Why Terrorists Attack Education’. 2016. https://protectingeducation.org/news/why-terrorists-attack-education/.

- Ojewale, O. ‘Theorising and Illustrating Plural Policing Models in Countering Armed Banditry as Hybrid Terrorism in Northwest Nigeria’. Cogent Social Sciences 9, no. 1 (2023): 2174486. doi:10.1080/23311886.2023.2174486.

- Ojewale, O. ‘The Bandits’ World: Recruitment Strategies, Command Structure and Motivations for Mass Casualty Attacks in Northwest Nigeria’. Small Wars & Insurgencies 35, no. 2 (2024): 228–255. doi:10.1080/09592318.2024.2301713.

- Ojewale, O. ‘Rising Insecurity in Northwest Nigeria: Terrorism Thinly Disguised as Banditry’. 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/rising-insecurity-in-northwest-nigeria-terrorism-thinly-disguised-as-banditry/.

- Ojewale, O., and M. Sadiq. ‘Why Nigeria’s Bandits are Recruiting Women for Gunrunning’. ISS Today, August 14, 2023. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/why-nigerias-bandits-are-recruiting-women-for-gunrunning.

- Oluwasanjo, A. ‘We Now Farm for Bandits; They Rape Our Wives, Daughters at Will: Katsina Elder’. 2022. https://gazettengr.com/we-now-farm-for-bandits-they-rape-our-wives-daughters-at-will-katsina-elder/.

- Onapajo, H. ‘Why Children are Prime Targets of Armed Groups in Northern Nigeria’. 2021. https://theconversation.com/why-children-are-prime-targets-of-armed-groups-in-northern-nigeria-156314.

- Phillips, B. J. ‘Why Schoolchildren are Regularly Being Targeted by Terrorist Groups in Many Countries’. 2023. https://theconversation.com/why-schoolchildren-are-regularly-being-targeted-by-terrorist-groups-in-many-countries-208341.

- ReliefWeb. ‘Displacement Tracking Matrix: Nigeria North-West and North-Central Crisis’. Monthly Dashboard #1, December 23, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/displacement-tracking-matrix-nigeria-north-west-and-north-central-crisis-monthly-dashboard-1-23-december-2022.

- Rosenje, M., and O. Adeniyi. ‘The Impact of Banditry on Nigeria’s Security in the Fourth Republic: An Evaluation of Nigeria’s Northwest’. Zamfara Journal of Politics and Development 2, no. 8 (2021): 56–81.

- Rufai, M. ‘Cattle Rustling and Armed Banditry along Nigeria Niger Borderlands’. OSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 23, no. 4 (2018): 66–73.

- Slatta, R. ‘Banditry as Political Participation in Latin America from Criminal Justice History’. An International Annual 1 (1990): 171–187.

- Taylor, A. J. ‘Thoughts on the Nature and Consequences of Ungoverned Spaces’. SAIS Review of International Affairs 36, no. 1 (2016): 5–15. doi:10.1353/sais.2016.0002.

- Uche, J., and I. Chijioke. ‘Nigeria: Rural Banditry and Community Resilience in the Nimbo Community’. Conflict Studies Quarterly 24 (2018): 71–82.

- UN Chief Condemns Attack on School in Nigeria. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/02/1085022.

- UNESCO. ‘Education Under Attack: A Global Study on Targeted Political and Military Violence Against Education Staff, Students, Teachers, Union and Government Officials, Aid Workers and Institutions’. 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000186809.

- UNESCO. ‘Protecting Education from Attack: A State-of-the-Art Review’. 2019. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000186732?posInSet = 1&queryId = 2de8e2a9- 77aa-45d9-990a-eeb663ab36d3.

- Whelan, T. ‘Africa’s Ungoverned Space’. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs, Briefing Addressed at the Portuguese National Defense Institute, Lisbon, May 24, 2006.

- Winsor, M., and J. Bwala. ‘Hundreds of Nigerian Schoolgirls Freed Days After Being Kidnapped, Official Says’. March 2, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/International/hundreds-nigerian-schoolgirls-freed-days-kidnapped-official/story?id = 76198012.

- Yenwong-Fai, U. ‘The Nigerian Militant Islamic Movement, Boko Haram, Poses a Threat Beyond Nigeria's Borders at Greatest Risk are Cameroon and Niger’. 2012.