ABSTRACT

The word cunt is the second most popular subject of offensive language charges and infringement notices in New South Wales, after fuck. While the latter word has been the subject of considered academic and judicial critique, the basis for any legal offensiveness ascribed to the former term has received inadequate scholarly and jurisprudential attention. Noting the power of judicial discourse to shape what is criminally offensive, in this article, I evaluate judicial views on the ‘c-word’ with reference to sociolinguistic literature on swearing. I find that many of the judicial representations do not withstand scrutiny. The article may aid lawyers attempting to demonstrate evolving views on the word cunt in courtroom advocacy.

Introduction

Words are like stories, don’t you think, Mr Sweatman? They change as they are passed from mouth to mouth; their meanings stretch or truncate to fit what needs to be said. The Dictionary can’t possibly capture every variation, especially since so many have never been written down.

There is no doubt that cunt is a powerful word. It performs a range of interactional, rhetorical, psychological and physical functions—to express shock, relieve pain, abuse, ridicule, build solidarity and even convey affection (Stapleton et al., Citation2022). This has not always been the case, for cunt has not always been a swear word. In Middle English, it appeared in medical textbooks, and was even used in surnames, street and plant names as a denotative term for vagina (Hughes, Citation2006). Although a steadfast component of the English vernacular, the word was unwritable in Victorian English and also unutterable—at least in ‘polite company’ (Mohr, Citation2013). While individual perspectives on its offensiveness vary, many still consider cunt to be one of the most objectionable words in the English language (Millwood-Hargrave, Citation2000). Readers who share this view are forewarned that the word is necessarily repeated throughout this article.

The present inquiry was inspired by two questions. Have societal attitudes towards the word cunt changed? And if they have, how should its use be judged by the criminal law?

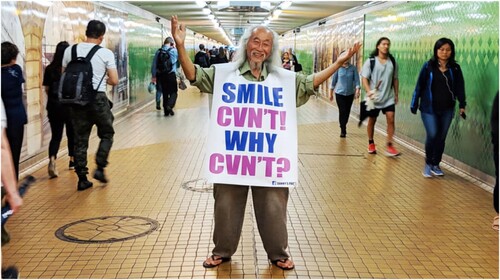

Such questions were considered by Magistrate Milledge in the New South Wales (NSW) Local Court case, R v Lim (Citation2019). At 9am on 11 January 2019, Danny Lim, a 75-year-old pensioner, accompanied by his companion dog Smarty, was standing at a pedestrian thoroughfare in Sydney’s CBD. Lim is a well-known Sydney personality. Smiling and gesturing a peace sign, he is regularly seen sporting vivid sandwich boards displaying political and humorous slogans at busy thoroughfares. Lim’s motivation? To make people ‘think out of the box’, ‘smile’ and to ‘show them life is for living’ (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2019, p. 2, 16).

Lim was approached by two police officers—Constable Ashleigh Hodge and Leading Senior Constable Salman. The officers had received a complaint from a 41-year-old female about a man wearing an ‘offensive sign’. They informed Lim about the complaint, explaining: ‘on first glance it looks like the rude word’. The officers requested him to remove it and ‘move on from the area’ (Hodge, Citation2019). The sign read on one side ():

SMILE

CVN’T!

WHY

CVN’T?

HORNY

SAX

LOVE

CVN’T BLOW

Figure 1. Danny Lim at Sydney’s Central Station (Double Bay Today, Citation2019).

Lim elected to challenge the fine in court. Acquitting Lim in an ex tempore judgment, Magistrate Milledge commented that personally, she did not like his language (R v Lim, Citation2019, p. 40). However, her Honour found that the hypothetical reasonable person would find the sign ‘provocative and cheeky’ but ‘not offensive’ (p. 41).

The legal offensiveness of ‘cunt’

Like this article’s title, Lim’s sign did not explicitly use, but alluded to, the word cunt. While many English speakers report this word to be among the most offensive terms in the language, attitudes towards this and other swear words vary individually, cross-culturally and at different points in history (Allan & Burridge, Citation2006; Burridge, Citation2016; Stapleton et al., Citation2022). As Justice Harlan opined in the well-known US Supreme Court First Amendment case, Cohen v California (Citation1971): ‘one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric’.

Cunt is the second most popular subject of offensive language charges and infringement notices in NSW, after the word fuck (NSW Ombudsman, Citation2009; Trollip et al., Citation2019). The phrases fucking cunt, fuck off cunts, dog cunts and variations on these themes appear frequently in offensive language cases, usually used towards or in the presence of police (Trollip et al., Citation2019). The legal offensiveness of fuck has received substantial academic and practitioner consideration (see, eg, Commissioner of Police v Anderson, Citation1996; Lawrence et al., Citation2016), with defence lawyers commonly citing Magistrate Heilpern’s consideration of the social usage and reception of fuck in the unreported case Police v Butler (Citation2003) to argue the word is losing its edge. Similarly, Mullighan J held in Hortin v Rowbottom (Citation1993) that fuck ‘is now used in ordinary conversation by both men and women … without offending contemporary standards of decency’ (p. 389). Not all Australian judges have adopted a liberal attitude towards the public utterance of fuck in recent decades, however. For instance, in Heanes v Herangi (Citation2007), Johnson J in the Supreme Court of Western Australia upheld the appellant’s disorderly conduct conviction on the grounds that the words ‘fuck off’ said to a police officer challenged the officer’s authority (for discussion, see [deleted for peer review]).

Less attention has been paid to the legal offensiveness of cunt, perhaps due to a perceived heightened taboo status among judges, academics and practitioners. Given its frequent appearance in offensive language cases, it is time the criminal law’s treatment of cunt receives critical scholarly examination.

This article interrogates views on the word cunt expressed in offensive language case law. I do so through a case study analysis of R v Lim and then relating the magistrate’s opinions to broader judicial discourse. Few of the thousands of offensive language incidents recorded each year make it to a contested hearing (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Citation2022). Of those that do, even fewer are likely to be reported or publicised. The court transcript and reasons for decision in R v Lim thus provide rare insight into judicial decision-making around offensive language and behaviour.

Noting the power of judicial discourse to constitute identities, attitudes and power relations in the criminal law (Ehrlich, Citation2001), I analysed the transcript and decision in R v Lim to understand how the magistrate determined whether cunt was offensive. My analysis paid close attention not only to the linguistic content and meaning of the transcript and judgment, but also to the relationship of these texts with broader offensive language jurisprudence and social contexts. The analysis therefore integrates Fairclough’s method of critical discourse analysis that is ‘concerned with continuity and change’ at a ‘more abstract, more structural, level, as well as with what happens in particular texts’ (Citation2003, p. 3).

Sociolinguistic literature on contemporary and historical usage of, and attitudes towards, cunt is drawn upon to critique judicial representations of swearing. Sociolinguistics offers a suitable body of literature from which to analyse offensive language jurisprudence because its primary concern is with how language is used in social contexts (Eades, Citation2010). Modern sociolinguistics recognises that language change is inevitable, ubiquitous and related to social factors (Eades, Citation2010, p. 7). Its insights can counter popular myths about how words can and should be used, such as the belief that language is in a state of ‘moral decline’ (Eades, Citation2010, p. 6).

Having summarised the facts of R v Lim and my methodology in Part One, Part Two outlines the law prohibiting offensive conduct and language before explaining the theoretical concept of language ideologies in Part Three. Part Four identifies language ideologies—‘common sense’ views about language—articulated about cunt in R v Lim. These include that swear words are an unnecessary part of the English language, the word cunt should be eliminated from public space, language standards are slipping, cunt has only one, sexual meaning and cunt offends women. I evaluate these judicial views with reference to sociolinguistic research on swearing, finding that many do not withstand scrutiny. Part Five considers how cunt and other swear words can be deployed to challenge power structures, while noting the inextricable link between taboo language and prohibition. I conclude by arguing that criminal defence advocacy may be assisted by sociolinguistic evidence to demonstrate evolving views on the ‘c-word’. However, advocacy can only play a limited role while police remain the gatekeepers—and often the sole arbiters—of criminal offensiveness.

The law prohibiting offensive language and conduct

The offence with which Lim was charged, and of which he was ultimately acquitted, was offensive conduct in public contrary to s 4(1) of the Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW). That sub-section provides:

A person must not conduct himself or herself in an offensive manner in or near, or within view or hearing from, a public place or a school.

Police may take one of several actions when faced with suspected offensive language or behaviour in public: they may ignore the conduct, issue a caution, a warning or a criminal infringement notice (if aged 18 or over), or charge someone with a criminal offence. Arrest should be used as a last resort (DPP v Carr, Citation2002). To prove either charge:

the conduct/language must be voluntary (Jeffs v Graham, Citation1987);

the conduct/language must be objectively offensive, meaning that it must evoke a significant emotional reaction of resentment, outrage, disgust or hatred in the mind of a reasonable person (Monis v The Queen, Citation2013, [303], per Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ; State of New South Wales v Beck, Citation2013); and

the conduct/language must take place in or near, or within view or hearing from, a public place or school (Summary Offences Act 1988, ss 4(1) and 4A(1)).

Case law has established that what is considered offensive changes with community standards (Ball v McIntyre, Citation1966). Regard must be had to the context in which the behaviour occurred (Dowse v State of New South Wales, Citation2012). A member of the public need not actually be caused offence; it is sufficient if the hypothetical reasonable bystander, who is neither thick- nor thin-skinned and is reasonably tolerant and contemporary, would be offended (Ball v McIntyre, Citation1966; McCormack v Langham, Citation1991). The case law is not settled on the question of whether the prosecution need prove mens rea—that the defendant intended or foresaw the possibility of causing offence (Lawrence et al., Citation2016; McNamara & Quilter, Citation2013). The language or behaviour must be offensive enough to warrant the intervention of the criminal law (Brokus v Brennan, Citation2022; Ferguson v Walkley, Citation2008). As a defence to either charge, the defendant may satisfy the court, on the balance of probabilities, that they had a ‘reasonable excuse’ for conducting themselves in the manner alleged (Summary Offences Act Citation1988, ss 4(3) and 4A(2)).

History repeating

This was not the first time that Lim had been the subject of arrest or charge for displaying a sign that alluded to the word cunt. Nor would it be the last. On 21 November 2022, Lim, wearing the same sign as that described above, was hospitalised after police performed a leg sweep which threw Lim off-balance, causing his head to impact the tiled floor of Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building. The officers had earlier instructed Lim to ‘move on’ following a complaint from a security guard regarding the sign (Koziol, Citation2022). The matter was subject to internal police investigation, but no charges were laid against police (Rose, Citation2022).

Two years earlier, in 2017, a Sydney magistrate convicted the septuagenarian of offensive conduct for displaying this message in Sydney’s eastern suburbs:

PEACE SMILE

PEOPLE CAN CHANGE

“TONY YOU

CɄN’T..”

LIAR, HEARTLESS, CRUEL

PEACE BE WITH YOU.

The prevalence of the impugned word [cunt] in Australian language is evidence that it is considered less offensive in Australia than other English speaking countries, such as the United States. However, that also appears to be changing as is evidenced from the increase in American entertainment content featuring the impugned word. (Lim v The Queen (Citation2017), [50])

Theoretical framework for analysis of judicial representations of swearing

The judicial statements extracted above are examples of language ideologies: socially produced representations through which language is imbued with cultural meaning (Cameron, Citation2014, p. 281; citing Schieffelin et al., Citation1998). Language ideologies are spoken and written representations of language, which can encompass beliefs. Such representations are seldom only about language but extend to ‘other areas of cultural discourse such as the nature of persons, of power, and of a desirable moral order’ (Cameron, Citation2014, p. 282). For example, if I were to declare that adults should not swear in the presence of children because this will teach them bad habits, I am not only representing swearing as contagious; I am also making a comment about the nature of children as they relate to adults—implying that the former are more innocent and impressionable than the latter. Judgments about words being off-limits or distasteful tend to mirror prevailing social mores that can be ‘very deep seated’ (Andersson & Trudgill, Citation1992, p. 64). The identification of language ideologies allows us to unpack their historical basis and challenge the linguistic and social orders such representations normalise (Eades, Citation2010, p. 242).

Language ideologies permeate the legal process and regularly go unchallenged (Eades, Citation2010; Eades et al., Citation2023). The tertiary education of legal practitioners in aspects of spoken and written language engenders a ‘strong’—and at times misplaced—‘confidence in their knowledge about language’ (Eades et al., Citation2023, p. 12). This can lead to lawyers and judges failing to grasp that linguistics is a distinct field of study with a scientific orientation and also, to appreciate how linguistic findings can ‘undermine apparent facts of common knowledge’ (Eades et al., Citation2023, p. 13).

The proliferation of common misconceptions about language is observable in offensive language and behaviour cases, the resolution of which require a decision maker to determine whether the defendant’s words, in the context in which they were used, would significantly offend the reasonable bystander (Monis v The Queen, Citation2013). To do this, the magistrate must consider ‘contemporary community standards’ (Heanes v Herangi, Citation2007). When determining community standards, courts have largely eschewed expert evidence such as that from linguists about the meaning or usage of a particular word, reasoning that ‘[m]agistrates with a wide experience of life and human foibles are generally in the best position’ to judge whether language is offensive (Heanes v Herangi, Citation2007, p. 218; citing Mogridge v Foster, Citation1999, [7]—[8]). However, the refusal to allow linguistic evidence in offensive language cases may be changing, as I explain in the concluding discussion of a recent offensive language case, Brokus v Brennan (Citation2022).

Language ideologies in R v Lim and other cases

Swear words are unnecessary

Several ‘common sense’ ideas about cunt, and swearing more generally, can be identified in Magistrate Milledge’s ex tempore judgment in R v Lim. One such example is that swear words are an unnecessary part of the English language. Another is that it would be desirable for them to be eliminated from public space. When determining whether Lim’s sign was offensive, her Honour referred to the fashion label F-C-U-K and to the ‘crude slogans’ of Wicked Campers (p. 33).Footnote2 Her Honour stated:

I personally find that type of advertising distasteful, I cannot see any need for it … I do not like it, but I am not the hypothetical reasonable person. I do not like it, I wish those vans were off the road, I wish the signs were off the city streets. (pp. 34, 40, emphasis added)

Standards are slipping

Additional language ideologies articulated in Magistrate Milledge’s judgment include that swearing is uncivilised, language standards are slipping and that something must be done to rectify this language decay. These views can be observed in the following three quotes in R v Lim:

we are lowering our standards and nobody seems to be doing anything about it (p. 34).

the authorities are changing all the time, because standards are changing. I think they are diminishing. I think they are reducing (p. 41).

when he speaks of Tony [Abbott] being a ‘C-U-N-apostrophe-T’, I would find that offensive and I would think that it was out of place in a decent and civilised community (p. 34).

Such claims are by no means unprecedented in Australian judicial and broader social discourse. Similar views were articulated by a magistrate in 1919, that ‘the practice of foul language’ was on the rise, with ‘disgusting terms … used quite frequently before women, even mothers—a thing undreamt of a few years ago’ (Geelong Advertiser, Citation1919). Decades before this, in 1883, a letter to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald remarked that ‘the disgusting habit, so prevalent in this city, of cursing and swearing in the streets’ was ‘the worst … of any place that I have visited’. The author added that ‘the most disgusting language … has emanated from women’ (Citation1883). A century later, an editorial in the same publication argued: ‘A large section of the population—say, anybody over 35—can remember when it was possible to go from one week’s end to another without hearing an obscenity spoken in public’ (Jones, Citation1985). Depicting a bygone era or faraway cities that have cultivated a more genteel society than the one complained about, these statements share the assumptions that swearing is becoming more prevalent; swearing is worse in particular locations (coincidentally, where the author is writing about); the swear words used today are more depraved than those of the past; and the language used by a population reflects its state of refinement (with bad language associated with those of lower social status). Consistent with the myth that swearing is a sign of an ‘impoverished vocabulary’, Lim, for example, is described by Magistrate Milledge as: ‘A bizarre 75 year old, who seems not to know how to use language properly’ (p. 35). As previously noted, language ideologies are rarely about language alone; they pass judgment on the nature of people and what amounts to a desirable moral order. Thus, inherent in the idea that language standards are diminishing is that moral depravity is increasing.

Cunt has a singular, sexual meaning

The next passage from Magistrate Milledge’s judgment contains numerous language ideologies, namely, that the word fuck is adaptable while cunt is not; because of this, fuck is more acceptable than cunt; and cunt has only one meaning:

I hear what the sergeant says with regards to the ‘C-U-N-T’ word, that does have a very different meaning to it. He said that the word ‘fucked’, and he used that in court, can be used a number of ways. It can be used to express somebody’s feelings, as well as an action. He said that there is a myriad of ways that that word can be used, but the word ‘C-U-N-T’ can only be used one way, and that would suggest that its level of acceptance is somewhat less than the ‘F-U-C-K’ word. (R v Lim, p. 34, emphasis added)

The idea that the word cunt is less acceptable than fuck due to the former word’s supposed singular, sexual meaning has been repeated in other offensive language cases. In Jolly v The Queen (Citation2009), for example, Cogswell DCJ interpreted the defendant’s phrase dog cunts literally as a ‘reference to animals’ and voiced disgust at ‘[t]he images conjured up by such language’ (see Methven, Citation2016, for further discussion). It may be that the judge in Jolly v The Queen and the magistrate in R v Lim consciously selected literal interpretations over more probable, contextual interpretations. Alternatively, their adherence to the ideology of literalism might be a result of ignorance, and a failure of the defence to submit evidence of common contextual usages of swear words (for instance, the phrase dog cunts is commonly used to challenge police authority in a way that is largely divorced from any denotative meaning).Footnote3 Nonetheless, both cases show how advocacy and interpretative choices influence the offensiveness attributed to cunt.

This is not to ignore the historical period in which cunt was commonly used denotatively. Many modern taboo expressions emerged in written texts in the eleventh century, when an ‘informal, earthier vocabulary begins to appear in writing’ (Crystal, Citation2012, p. xviii). Earliest among such expressions is cunt—‘the great survivor’ of terms that refer to the vagina if interpreted denotatively (Green, Citation2014, p. 184). While its historical origins have not been identified with certainty, linguist Crystal (Citation2012) cites the Old Norse word kunta as having the same meaning, suggesting it could have been brought with the Vikings. The word did not appear in Old English texts (which tended to formalise, and so provide an inaccurate record of speech) and was ‘rare’ in Middle English, suggesting that it was ‘sensitive’ at the time.Footnote4 Variations of cunt also appeared as euphemisms in Middle English, including quaint and the alternatives cunny, quim and quoniam (Crystal, Citation2012, p. 66; Hughes, Citation2006).

In the High Middle Ages, cunt shed its stigma and was used as a descriptive term for vagina. Cunt appeared in thirteenth and fourteenth century street names (such as Gropecunt Lane, now called Magpie Lane), plant names, medical texts and surnames (as in Bele Wydecunthe, Godwin Clawecucthe or John Fillecunt) (Hughes, Citation2006; Mohr, Citation2013). Demonstrating the ever-changing meanings of words and attitudes towards them, cunt again underwent a period of heightened proscription from the mid-fifteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, a period over which the most offensive language changed from religious and blasphemous terms to those associated with body parts, bodily functions and sex (McEnery, Citation2006). Cunt was nonetheless included in the poetry of the Earl of Rochester John Wilmot (1647-1680) who wrote of a lewd cunt and devouring cunt, and George Etherege (1636-1691) (Hughes, Citation2006, pp. 110–12). In his 1811 edition of the Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Francis Grose (Citation1811) demonstrated a misogynistic attitude towards female sexual anatomy by defining ‘c**t’ as ‘a nasty name for a nasty thing’.

Although unprintable in the Victorian period—‘the apogee of the rise of civility’ (Mohr, Citation2013, pp. 190–91), cunt very much survived in spoken English. It was not until the First World War, however, that cunt is recorded as assuming a non-denotative meaning, with some soldiers even adding—ing on the end to deploy cunting as an adjective (Cook, Citation2013).

Cunt is inflexible

Related to the idea that cunt should be interpreted literally (as an offensive term for vagina) is the assumption repeated in R v Lim that this word ‘can only be used one way’. While there may not be as many variations of cunt as the ‘chameleon-like’ (De Klerk, Citation2011, p. 40) swear word fuck (unfuckingbelievable, fuckload and fuckhead being just some examples), the syntactical functions of, and meanings conveyed by, cunt have multiplied. Reflecting this, the Oxford English Dictionary added the derivatives cunted, cunting, cuntish and cunty in 2014 (Oxford University Press, Citation2014). These words do not convey a predominantly sexual meaning. Cunty (adj.), for example, describes someone who is ‘despicable; highly unpleasant; extremely annoying’.

Burridge (Citation2016) explains that cunt serves a variety of pragmatic and interpersonal functions in Australian English: to ‘let off steam, abuse, offend—and express mateship and endearment’, the latter conveyed through phrases such as Love that cunt! or What a sick cunt! Its use is prolific among certain groups and sub-cultures, with McLeod’s (Citation2011) research finding that the word regularly features in the speech of Australian tradies to express humour, build solidarity and differentiate themselves from other groups. The Australian Macquarie Dictionary (Citation2023) now records multiple senses in which cunt is used, including five nouns, an adjective and the following phrases:

a cunt of a, an extremely difficult, unpleasant, disagreeable, etc., … : a cunt of a job

a mad cunt, a person who is thought to be eccentric or weird

a sick cunt, a person who is much admired.

While these definitions demonstrate cunt’s growing flexibility, Wajnryb (Citation2005) has warned against depending on dictionaries alone to decipher the meaning of swear words. Swear words convey connotative meanings and are primarily used to express emotions (Jay & Janschewitz, Citation2008). Dictionary definitions can unduly shift one’s focus away from ‘the actual felt quality of connotation’, which ‘can only be derived from the situation or context of use’ (Wajnryb, Citation2005, p. 69).

Cunt is infrequently used in spoken language and popular culture

Having clarified that cunt has many meanings and functions, we now turn to another language ideology that features in offensive language cases: that cunt is infrequently used in spoken language and popular culture, and accordingly, offensive. Danny Lim, giving evidence at his 2019 trial, attempted to counter this idea by relaying that he had encountered the word cunt:

in Chaucer's Canterbury Tale, I've studied that in Malaysia. I didn't know the meaning till 30 years later … and it was in Shakespeare in Hamlet and in Lady Chatterley’s Lover it came up 14 times. (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2019, p. 19)

One should not overlook the extra effect of the addition of the epithet ‘cunt’. While today many erstwhile obscenities have lost some of their effect because of their frequent use in films, books and general speech, in my opinion that word remains one which would be considered offensive to most people, particularly when used as an abusive expletive.

Censorious attitudes towards ‘four-letter words’ became more relaxed in 1970s England, with evolving attitudes coinciding with more relaxed social standards towards sex and the naked body (Mohr, Citation2013). The word cunt was introduced into the Oxford English Dictionary in 1972, having been excluded since its first publication.Footnote6 Another first was in 1979 when English rock singer, Marianne Faithfull, became the first woman to use cunt in popular music in her song Why’d Ya Do It? The song included the lyrics ‘Every time I see your dick I imagine her cunt in my bed’ (McEnery, Citation2006, p. 120).

In 1970s Australia, double standards on swearing—particularly with regard to who was allowed to swear—persisted. Wilson (Citation1978) noted the irony of Indigenous Australians in Moree being fined or jailed for saying fuck, cunt or cock while ‘middle class males and females flock’ to hear these words in Don’s Party or Mad Dog Morgan (pp. 55–56). Meanwhile, a liberalisation was taking place in Australian academia, with linguists and criminologists studying ‘four-letter words’ as a legitimate part of Australian English (see, eg, Taylor, Citation1976; Wilson, Citation1978).

With the arrival of the twenty-first century, cunt peppered popular culture mediums including music, film, musicals and television. The word featured in the television series Weeds, The Wire, Sex and the City, The Sopranos, The Thick of It and House of Cards, for example (Barnes, Citation2006). These shows provided a less sanitised—and hence, more accurate—portrayal of the speech of police, politicians, criminal gang members and professional women (Methven, Citation2018b).

Despite an increased presence on screens and over the airwaves, restrictions are still placed on modern audiences’ exposure to cunt. The coarse language guide of the Australian Classification Board (ACB) assigns an indicative classification of MA15 + to a film featuring cunt, with former Director Margaret Anderson explaining ‘You don’t expect to take your grandmother to an M film and have c—t language thrown at you’ (Koziol, Citation2019). With the rise of cable TV and streaming services, however, regulatory bodies like the ACB have less control over who can hear swear words, and when they can hear them.

In 2015, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) aired the word cunt-struck unbleeped in its Four Corners investigative journalism program (ABC, Citation2015). An opinion piece in Sydney tabloid, the Daily Telegraph, identified this as a sign of linguistic decline, arguing that Australians could ‘look forward to some lively language’ during evening weather reports, such as ‘a c … of a storm is developing in Cairns’ (Blair, Citation2015). While such liberal primetime broadcasting of cunt did not eventuate, the Macquarie Dictionary now contains a separate entry for cunt-struck: ‘adjective Colloquial (taboo) infatuated with a woman or women’ (Macquarie Dictionary, Citation2023).

The ABC faced further complaints, including from the Federal Communications Minister when, in a 2018 comedy sketch for the television show Tonightly, cunt was repeated multiple times by comedian Greg Larsen. In the sketch, Larsen suggested that the electorate of Batman be renamed ‘Batman was a cunt’ in light of the founder of the city of Melbourne, John Batman’s, involvement in the massacres of First Nations people (ABC, Citation2018). The Australian Media and Communications Authority investigated the skit and cleared the broadcaster of any wrongdoing (Briggs, Citation2009). Australian Federal Ministers, and even Prime Ministers (Davidson, Citation2014), have been caught using or alluding to the word. A prominent example was in 2014 when Federal Health Minister Christopher Pyne is alleged to have said to Opposition Leader Bill Shorten ‘You’re such a cunt’ in Parliamentary Question Time.Footnote7

In Australian news media, cunt is still commonly referred to as ‘the c-word’ or ‘c***’, especially in public-facing titles. This too is changing. The Guardian style guide provides that the word ‘can be spelt out in full’ (The Guardian, Citation2021). The ABC leaves such vocabulary choices to the ‘common sense’ of authors and editors, advising that ‘isolated swearing in a lengthy news feature, for example, would generally be less likely to cause offence than that same coarse language used in children’s programming’ (ABC, Citationn.d.). Simply put, while the broadcast and publication of cunt is regulated in modern popular culture, it also regularly evades censure, particularly when used in satirical and factual contexts.

Cunt should be avoided in the courtroom

Circumlocution strategies are employed throughout the hearing and judgment in R v Lim. This is exemplified in the extract above, where the magistrate spelt ‘C-U-N-T’ like a parent might do to hide a word from an illiterate toddler. This functions as a charade of sorts—the adult audience in the courtroom being literate, and thus aware of the word alluded to. Her Honour spelt the word ‘C-U-N’T’ three times in the judgment, and also replaced cunt with the words ‘it’ and ‘that word’. In fact, Magistrate Milledge only used the word cunt three times in her judgment, once in inverted commas and the other times when quoting what Constable Salman said in evidence.

The magistrate’s lexical choices in these examples were likely influenced by those of the police prosecutor, who used circumlocutions such as spelling C-U-N-T, the phrase ‘the c-word’ or simply ‘that word’ to avoid repeating cunt directly. The prosecutor went to such great lengths to avoid saying cunt aloud that the magistrate remarked: ‘Look, we’re not going to faint if you say the word, sergeant’ (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2019, p. 25). The language ideology expressed through these avoidance strategies is that the repetition of a swear word, even in the decontextualised setting of a courtroom, can taint its user or offend its audience.

Word avoidance functions as a persuasive advocacy strategy in offensive language trials to strengthen the perceived offensiveness of a word. I have elsewhere described how, in Australian obscene language trials during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the words alleged to have been spoken by the defendant would be written on a slip of paper, then handed to the magistrate (Methven, Citation2020). This method of containment had the effect of conveying to those in the courtroom that the mere repetition of swear words, divorced from their original spoken context, was obscene. Conversely, in recent decades, research has demonstrated how repeated exposure to a word (such as the repetition of cunt in this article) can desensitise users and audiences to any emotive effect (Wajnryb, Citation2005, p. 71; Stephens & Umland, Citation2011).

Cunt is more offensive when used in the presence of a woman

An additional language ideology expressed in R v Lim is that cunt is more offensive if used in the presence of a woman. This view was articulated by the 41-year-old witness who initially complained to police about Lim’s sign, explaining that she ‘understood’ it to say cunt and ‘as a woman I found the word highly offensive’ (Hodge, Citation2019).

The idea that cunt in particular, and swear words more generally, are more offensive if repeated in the presence of, or towards, women, is a widely-held folk belief in many English-speaking societies (McEnery, Citation2006, p. 34). It has also been repeated in offensive language and disorderly conduct cases (Methven, Citation2020). For instance, in Del Vecchio v Couchy (Citation2000), the trial magistrate held that cunt was insulting ‘to a female, be it a police officer or otherwise’. Justice Gummow in the High Court of Australia remarked that the gender of the female officer to whom the phrase ‘You fucking cunt’ was uttered was ‘significant’, with Callinan J adding that any men present might be provoked to respond ‘physical[ly]’ to the words, citing ‘chivalry’ as a justification (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2004). Eades (Citation2008) has similarly documented how, in the Pinkenba case, evidence of an Indigenous child saying cunt in a police car was recontextualised in police questioning as disrespectful and embarrassing to the female officer present, aiding the depiction of the boy as a ‘juvenile delinquent’ (p. 159).

On the other hand, Higgins J in the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory remarked upon the irony that ‘a male person not offended by indecent words is offended by their utterance in the presence of a female person even if that female person is herself not shown to be offended’ (Saunders v Herold (Citation1991), p. 7). Justice Higgins found that the reasonable bystander outside the Canberra’s Worker’s Club at 11pm would not find the words uttered by the appellant: ‘Why don't you cunts just fuck off and leave us alone?’ offensive (p. 8).

The reclamation of cunt

Cunt is one of a litany of English words that can be used to convey disgust towards women or the female body—including terms such as bitch, whore, cow and slut (Wajnryb, Citation2005, p. 133). When the police prosecutor suggested to Lim that his sign was ‘meant to be the C word’, which was offensive on gendered grounds, Lim rejected these propositions, responding: ‘I’ve got the highest respect for the C word’ (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2019, p. 19). Lim’s subversion of the prosecution’s attempt to represent cunt as misogynistic resembles broader feminist efforts to ‘reclaim’ cunt, stripping the term of its disparaging connotations much like Black Americans have reclaimed the n-word, the gay community—queer, or Australians of Greek or Italian heritage—wog (Allan & Burridge, Citation2006; Rahman, Citation2011).Footnote8

English language historian, Melissa Mohr (Citation2013, p. 214) has argued that alongside the development of feminism, ‘many swearwords have become more equal opportunity, not less. Bitch can now be applied to men and women, as can cunt.’ Wiles (Citation2014) has even suggested that cunt is ‘etymologically, more feminist than vagina, which is dependent on the penis for its definition, coming from the Latin for ‘sword sheath’’.

The word cunt garners clashing responses from those who wish to celebrate it, and those who would rather banish it from public discourse. When artist Greg Taylor displayed 141 porcelain sculptures of vaginas taken from casts of women’s genitals in his 2009 exhibition ‘CUNTS … and other conversations’, Australia Post banned postcards advertising it, warning they were in breach of federal law (Harrington, Citation2018, p. 57). A spokeswoman for the Conservative Australian Family Association stated that ‘women, in particular’, would find the exhibition’s images and words ‘deeply offensive’ (Harrington, Citation2018, p. 57). Conversely, one of Taylor’s models found the experience of having her ‘cunt portrait’ taken ‘empowering’, being ‘from a generation that never even looked down there. I wasn’t even told about the menstrual cycle until I thought I was bleeding to death’ (Harrington, Citation2018, p. 57). Taylor’s own response to the censorship attempts was to question why ‘the vile and most disgusting thing’ in Australian culture would be a cunt (Harrington, Citation2018, p. 58). The exhibition has been on regular display at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art.

In 1971, writer and feminist Germaine Greer advocated for women to celebrate cunt in her essay ‘Lady love your cunt’ (Greer, Citation1994). Love it, Greer argued, because ‘nobody else is going to. Primitive man feared the vagina, as well he might, as the most magical of the magical orifices of the body’ (p. 74). Decades later, Greer expressed perverse pleasure in how cunt had retained its power:

I love the idea that this word is still so sacred that you can use it like a torpedo, that you can hole people below the waterline. You can make strong men go pale. This word for our female ‘sex’ is an extraordinarily powerful reminder of who we are and where we came from. It's a word of immense power – to be used sparingly. (Barnes, Citation2006)

Swearing as power; swearing as resistance

A theme that runs through Lim’s court testimony is the disruption of taken-for-granted social and linguistic orders. Lim described how he wears his sandwich boards at busy thoroughfares and protests to provoke Sydneysiders to ‘think out of the box’, counter rhetoric that stokes fear on racial grounds, and spread peace (Transcript of Proceedings, Citation2019, p. 16). He subverted the idea that cunt is offensive by referring to its use in literature, and his respect for gender equality and the women in his life (p. 19).

The deployment of swear words to challenge authority and express political resistance has been identified as a theme in offensive language cases (Lennan, Citation2006; Eades, Citation2008, pp. 300–308; Walsh, Citation2017; Methven, Citation2018a). Linguists and language historians have similarly documented a strong link between swearing, power and resistance (see Eades, Citation2008; Mohr, Citation2013; Stapleton et al., Citation2022). To express opposition is among the most important functions of swear words; they are ‘the most powerful words we have with which to express extreme emotion, whether negative or positive’ (Mohr, Citation2013, p. 13). The power of swear words is also impossible to extricate from social and legal proscriptions on their use. It is a ‘circular effect’—the stronger the prohibitions placed on a word, the greater its power (Bryson, Citation2009, p. 214).

Thus, for example, swear words are prevalent in rap music, being the ‘go-to words … for resisting “the system” and the dominant culture that expects certain kinds of “good” language and behaviour’ (Mohr, Citation2013, pp. 247–48). Their use is not restricted to the left side of the political spectrum (Montiel et al., Citation2022), even if anti-swearing movements are conventionally associated with conservative politics (Harrington, Citation2018). In a 2016 rally for then US Republican presidential nominee, Donald Trump, for example, an attendee was photographed wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with: ‘She’s a Cunt. Vote for Trump’ (Saltz, Citation2016), where ‘She’ referred to Democrat presidential nominee Hillary Clinton. , on the other hand, shows a protestor in Scotland holding a sign that reads ‘TRUMP IS A CUNT’ (Godley, Citation2016).

Figure 2. Scottish comedian Janey Godley protesting the arrival of Donald Trump in Scotland (Godley, Citation2016).

While linguistic research has shown that most swear words fall into the themes of religion, sex, bodily excretions and body parts (Jay, Citation1999, p. 194; Hitchings, Citation2011, p. 241), recent surveys have demonstrated an uplift in the taboo status of insults on the grounds of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, disability or sexuality (see, eg, New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority, Citation2018). When NSW rugby league coach Andrew Johns stepped down after calling Dunghutti rugby player Greg Inglis a ‘black cunt’, for instance, it was the reference to the colour of his skin coupled with the epithet that formed the basis of Johns’ apology (Wilson, Citation2010).

Police do not typically use offensive language laws to protect minorities from racism. Instead, studies and inquiries have documented how police have used these laws as an instrument of racism (Anthony et al., Citation2021; Feerick, Citation2004; White, Citation2002; Wootten, Citation1991). The excessive enforcement of offensive language laws against First Nations Australians has been linked to the fiction of Australia as terra nullius, with Watego (formerly Bond) et al. (Citation2018) arguing:

The presence of Blackfullas exposes the lie of unoccupied land, and offends white sensibilities. Consequently, it is the bodies, acts and speech of Blackfullas that must be regulated, curtailed and caged as a means to contain the lie, or at the very least, rationalize the imperative for lying. (p. 422)

Whether racism played any role in the police officers’ decisions to arrest and use force against Lim, who was born in Malaysia, is unclear. The transcript does, however, record how Lim has been subjected to racist taunts from members of the Australian public while wearing his sandwich board signs:

When people come … and … tell you, ‘Go home you bloody slope head, go home,’ and so on. What do you do? You, you take it.’ I've been here for so long … I never learned to hate. (p. 29)

Conclusion: taking the sex out of swearing

This article has shed light on the role judicial choices, advocacy and criminal prohibition play in constructing and reinforcing the offensiveness of the word cunt. Through analysis of the transcript and judgment in R v Lim and broader criminal jurisprudence on offensive language, I identified several judicial language ideologies about cunt and swearing. These include that cunt is dispensable; it should be eliminated from public use; it is inherently offensive; it only conveys one (sexual) meaning; language standards are slipping; it is especially offensive to women; and its repetition should be avoided in the courtroom. I questioned the desirability of having speech policed and judged according to these ideas, particularly when they are undermined by sociolinguistic literature.

My analysis of judicial language ideologies, set against sociolinguistic perspectives on swearing, may be useful to legal practitioners countering ill-informed myths about ‘bad’ language. The Northern Territory Supreme Court case Brokus v Brennan (Citation2022) is illustrative in this respect. In that case, the appellant had pleaded not guilty to the charge of behaving in a disorderly manner in public, contrary to s 47(a) of the Summary Offences Act 1923 (NT). Police alleged that the appellant had repeatedly told them to ‘Fuck off’ and called them ‘cunts’ when they approached him in Gregory Terrace car park. The appellant continued to swear while patrons were leaving Uncle’s Tavern and crossing Gregory Terrace to access the car park. His speech was slurred, and at least two women and possibly another man were in the immediate vicinity.

The Local Court Judge found that the appellant had used obscene language and sentenced him to fourteen days' imprisonment for disorderly behaviour. On appeal to the Northern Territory Supreme Court, Blokland J adopted counsel for the defence’s submissions, finding neither the language to be obscene nor the behaviour, offensive. Her Honour justified her decision with reference to sociolinguistic literature:

It does not appear the appellant meant the words ‘fuck’ and ‘cunt’ or ‘cunts’ in their literal sense or original meaning as referring to sexual intercourse or female genitalia. Words such as ‘fuck’ and ‘cunt’ do not necessarily have a sexual connotation in current usage or in this context …

… Although unpleasant and sexist in some contexts, the use of the word ‘cunt’ seems to rarely refer to ‘vagina’. While ‘[F]ar fewer people will be upset by the word vagina than will be appalled to hear the word cunt’, there is nothing in the context here that would indicate use of the word cunt conveyed the idea of a vagina. (Brokus v Brennan, Citation2022, [53]-[55]; citing Hitchings, Citation2011, p. 241 and Methven, Citation2016, p. 128-9)

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the participants and co-convenor, Professor Penny Crofts, of the Unmasking Power workshop at the Faculty of Law, University of Technology Sydney, for their valuable feedback. Thank you also to the anonymous reviewers for their cogent advice on matters of law and language. All errors and omissions remain my own responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 In addition, the judge found that ‘the political nature’ of the communication amounted to a reasonable excuse. Having resolved the matter on that basis, Scotting DCJ decided it was not necessary to decide whether s 4 was invalid because it burdened the constitutionally implied freedom of political communication (Lim v The Queen (Citation2017), [48]–[53]).

2 Wicked Campers are a campervan rental company founded in Brisbane, Australia, known for displaying sexual, sexist and racist statements and images.

3 Trollip et al. (Citation2019, p. 503) provide examples in their examination of NSW Police offensive language narrative reports of police being called ‘dog cunts’ or a ‘dog cunt’, usually when the speaker ‘was resisting police instruction’ and/or was expressing ‘frustration with police intervention’. Walsh (Citation2017, p. 343) gives the example in R v Brown (Citation2013) of a First Nations person telling police: ‘Fuck you, you dog. Captain Cook white cunts’.

4 Although variations of cunt do not appear in records of Old English (a predominantly Germanic language existing from the 5th to mid-12th century), this does not conclusively indicate that it, or a similar word, was not used. Old English written language sources were ‘formal or oratorical in character’ and so do not provide an accurate reflection of colloquial patterns (Crystal, Citation2012, pp. xviii, 66).

5 The novel was first published privately in 1928.

6 The Oxford English Dictionary was originally published in fascicles issued from 1884, with its first complete volume published in 1933. The second supplement was added in 1972 (Oxford University Press, Citationn.d.).

7 Pyne’s office denied this, saying he had instead said ‘grub’, but it is alleged the recording suggests otherwise (Jabour, Citation2014).

8 A key distinction is that the direct use of the ‘n-word’ by non-Black Americans is still generally considered highly offensive due to its linguistic history — it is a word that ‘has historically wreaked symbolic violence … often accompanied by physical violence’ (Rahman, Citation2011, p. 6).

References

- AAP. (2019). Body camera of Danny Lim’s arrest in Sydney. August 30, 2019. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/raw-body-camera-of-danny-lims-arrest-in-sydney/video/11189e7629cbe2ad0aebf45c3c484779.

- Allan, K., & Burridge, K. (2006). Forbidden words: Taboo and the censoring of language. Cambridge University Press.

- Andersson, L., & Trudgill, P. (1992). Bad language. Penguin Books.

- Anthony, T., Jordan, K., Walsh, T., Markham, F., & Williams, M. (2021). 30 Years on: Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Recommendations Remain Unimplemented. https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2021/4/WP_140_Anthony_et_al_2021_0.pdf.

- Australian Broadcasting Commission. (2015). Four Corners. Jackson and Lawler: Inside the eye of the Storm. Aired October 19, 2015.

- Australian Broadcasting Commission. (2018). Tonightly with Tom Ballard. Season 1, Episode 64. Aired March 15, 2018.

- Australian Broadcasting Commission. (n.d.). The ABC Style Guide. https://about.abc.net.au/abc-editorial/the-abc-style-guide/.

- Australian Law Reform Commission. (2018). Pathways to justice–An inquiry into the incarceration rate of aboriginal and Torres strait Islander peoples. Final Report No. 133. https://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/indigenous-incarceration-report133.

- Barnes, A. (2006). The C Word *. The Independent, January 22, 2006. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-c-word-340215.html.

- Blair, T. (2015). I c. t believe they used that word. Daily Telegraph, October 21, 2015.

- Briggs, K. (2009). Oe and ME cunte in place-names. Journal of the English Place-Name Society, 41, 19.

- Bryson, B. (2009). Mother tongue: The story of the English language. Penguin Books.

- Burridge, K. (2016). The ‘c-word’ may be the last swearing taboo, but doesn’t shock like it used to. The Conversation, February 17, 2016. http://theconversation.com/the-c-word-may-be-the-last-swearing-taboo-bdoesn’tsnt-shock-like-it-used-to-54813.

- Cameron, D. (2014). Gender and language ideologies. In S. Ehrlich, M. Meyerhoff, & J. Holmes (Eds.), The handbook of language, gender and sexuality (2nd ed, pp. 281–296). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cook, T. (2013). Fighting words: Canadian soldiers’ slang and swearing in the great War. War in History, 20(3), 323. doi: 10.1177/0968344513483229

- Crystal, D. (2012). The story of English in 100 words. St Martin’s Press.

- Davidson, H. (2014). Gough Whitlam – in His Own Words. The Guardian, October 21, 2014. https://www.theguar21ustraliaaustralia-news/2014/oct/21/gough-whitlam-in-his-own-words.

- De Klerk, V. (2011). A N***** in the woodpile? A racist incident on a South African university campus. Journal of Languages and Culture, 2(3), 39.

- Double Bay Today. (2019). Gun-wielding police arrest man wearing ‘FCUK’ Branded T-Shirt. January 13, 2019. https://doublebaytoday.com/gun-wielding-police-arrest-man-wearing-fcuk-branded-t-shirt/.

- Eades, D. (2008). Courtroom talk and neocolonial control. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Eades, D. (2010). Sociolinguistics and the legal process. Multilingual Matters.

- Eades, D., Fraser, H., & Heydon, G. (2023). Forensic linguistics in Australia. Cambridge University Press.

- Ehrlich, S. (2001). Representing rape: Language and sexual consent. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

- Feerick, C. (2004). Policing indigenous Australians: Arrest as a method of oppression. Alternative Law Journal, 29(4), 188. doi: 10.1177/1037969X0402900405

- Geelong Advertiser. (1919). How can foul language and swearing be stopped? June 10, 1919.

- Godley, J. (2016). One Night Only Trump is a cunt at leicester square theatre Nov 15th. June 28, 2016. https://medium.com/@janeygodley_42972/i-welcomed-trump-to-scotland-cc1b34be5471.

- Green, J. (2014). Language! 500 years of the vulgar tongue. Atlantic Books.

- Greer, G. (1994). The madwoman’s underclothes: Essays and occasional writings. Atlantic Monthly Press: 74.

- Grose, F. (1811). Classical dictionary of the vulgar tongue. Scholar Press.

- The Guardian. (2021). Guardian and observer style Guide: C April 30, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/guardian-observer-style-guide-c.

- Harrington, E. (2018). Women, monstrosity and horror film. Routledge.

- Hitchings, H. (2011). The language wars: A history of proper English. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Hodge, A. (2019). Statement of Police in the Matter of Police v Lim.

- Hughes, G. (2006). An encyclopedia of swearing: The social history of oaths, profanity, foul language, and ethnic slurs in the English-speaking world. ME Sharpe.

- Jabour, B. (2014). Christopher Pyne Denies Using C-Word in Attack on Bill Shorten. The Guardian, May 15, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/15/christopher-pyne-denies–c-word-against-bill-shorten.

- Jay, T. (1999). Why We curse: A neuro-psycho-social theory of speech. John Benjamins.

- Jay, T. (2009). The utility and ubiquity of taboo words. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01115.x

- Jay, T., & Janschewitz, K. (2008). The pragmatics of swearing. Journal of Politeness Research, 4, 267. doi: 10.1515/JPLR.2008.013

- Jones, M. (1985). The Curse of OK Obscenity. The Sydney Morning Herald, April 26, 1985.

- Jones, S. (1997). Sexsorship: The case of I love, You love. Limina, 3, 33.

- Koziol, M. (2019). Bongs, bare bottoms and bad language: Behind the scenes with Australia’s Chief Censor. The Sydney Morning Herald. September 7, 2019. https://www.smh.com.au/national/bongs-bare-bottoms-and-bad-language-behind-the-scenes-with-australia-s-chief-censor-20190904-p52nwd.html.

- Koziol, M. (2022). Street personality Danny Lim in hospital after attempted arrest at QVB. The Sydney Morning Herald. November 22, 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/street-personality-danny-lim-in-hospital-after-attempted-arrest-at-qvb-20221122-p5c0fa.html.

- Langton, M. (1988). Medicine square. In I. Keen (Ed.), Being black: Aboriginal cultures in settled Australia (pp. 201). Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Lawrence, S., Graham, F., & Hearne, C. (2016). ‘You Fucking Beauty’, ‘Fuck Fred Nile’ and Other Inoffensive Comments: A Discussion Paper on the Law of Offensive Language. https://criminalcpd.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/You-Fucking-Beauty-Fuck-Fred-Nile-Stephen-Lawrence-Feliciy-Graham-Christian-Hearn.pdf.

- Lennan, J. (2006). The ‘janus faces’ of offensive language laws: 1970-2005. UTS Law Review, 8, 118.

- Macquarie Dictionary. (2023). 9th ed. Online: Macmillan.

- McCullough, M. (2014). The gender of the joke: Intimacy and marginality in murri humour. Ethnos, 79(5), 677. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2013.788538

- McEnery, T. (2006). Swearing in English: Bad language, purity and power from 1586 to the present. Routledge.

- McLeod, L. (2011). Swearing in the ‘tradie’ environment as a tool for solidarity. Griffith Working Papers in Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication, 4(1/2), 1.

- McNamara, L., & Quilter, J. (2013). Time to define the cornerstone of public order legislation: The elements of offensive conduct and language under the summary offences Act 1988 (NSW). University of New South Wales Law Journal, 36, 534.

- Methven, E. (2016). Weeds of our Own making: Language ideologies, swearing and the criminal law. Law Context: A Socio-Legal Journal, 34, 117.

- Methven, E. (2018a). A little respect: Swearing, police and criminal justice discourse. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 7(3), 58. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i1.428

- Methven, E. (2018b). Offensive language crimes in law, media, and popular culture. In R. Nicole and M. Brown (Eds.), The Oxford encyclopedia of crime, media and popular culture. Oxford University Press.

- Methven, E. (2020). ‘A woman's tongue’: Representations of gender and swearing in Australian legal and media discourse. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 46(1), 57. doi: 10.1080/13200968.2020.1820747

- Methven, E. (2023). Skipping straight to the punishment: Criminal infringement notices and factors that influence police discretion. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 35(1), 100.

- Millwood-Hargrave, A. (2000). Delete expletives? Broadcasting standards commission. http://ligali.org/pdf/ASA_Delete_Expletives_Dec_2000.pdf.

- Mohr, M. (2013). Holy shit: A brief history of swearing. Oxford University Press.

- Montiel, C., Uyheng, J., & de Leon, N. (2022). Presidential profanity in duterte's Philippines: How swearing discursively constructs a populist regime. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 41(4), 428. doi: 10.1177/0261927X211065780

- New South Wales Legislative Council Select Committee. (2021). The high level of first nations people in custody and oversight and review of deaths in custody. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/lcdocs/inquiries/2602/Report%20No%201%20-%20First%20Nations%20People%20in%20Custody%20and%20Oversight%20and%20Review%20of%20Deaths%20in%20Custody.pdf.

- New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority. (2018). Language that may offend in broadcasting. https://www.bsa.govt.nz/assets/oldsite/Final_Report_-_Language_That_May_Offend_in_Broadcasting_2018.pdf.

- NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. (2022). New South Wales crime statistics. quarterly update. https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Publications/RCS-Quarterly/NSW_Recorded_Crime_Dec_2022.pdf.

- NSW Ombudsman. (2009). Review of the impact of criminal infringement notices on aboriginal Communities. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/tp/files/19933/FR_CINs_ATSI_review_Aug09.pdf.

- Oxford University Press. (2014). New Words List March 2014. Oxford English Dictionary. https://public.oed.com/updates/new-words-list-march-2014/.

- Oxford University Press. (n.d). OED Editions. Oxford English Dictionary https://www.oed.com/information/about-the-oed/history-of-the-oed/oed-editions/.

- Rahman, J. (2011). The N word: Its history and Use in the African American community. Journal of English Linguistics, XX(X), 1.

- Revenue NSW. (2023). Criminal Infringement Notice Scheme (CINS) Offences. https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/help-centre/resources-library/statistics.

- Rose, T. (2022). Danny Lim: NSW police to internally investigate arrest that left Sydney personality with brain bleed. The Guardian Australia. November 23, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/nov/23/danny-lim-nsw-police-to-internally-investigate-qvb-arrest-sydney-signs-personality-hospital-brain-bleed.

- Saltz, J. (2016). @jerrysaltz October 11, 2016. https://twitter.com/jerrysaltz/status/785672979460030465.

- Schieffelin, B., Woolard, K., & Kroskrity, P. (eds.). (1998). Language ideologies: Practice and theory. Oxford University Press.

- Stapleton, K., Fägersten, K. B., Stephens, R., & Loveday, C. (2022). The power of swearing: What We know and what We don’t. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue Internationale De Linguistique Generale, 277, 103406.

- Stephens, R., & Umland, C. (2011). Swearing as a response to pain — effect of daily swearing frequency. The Journal of Pain, 12(12), 1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.09.004

- The Sydney Morning Herald. (1883). Use of bad language: To the editor of the Herald, June 14, 1883.

- Taylor, B. (1976). Towards a sociolinguistic analysis of ‘swearing’ and the language of abuse in Australian English. In M. Clyne (Ed.), Australia talks: Essays on the sociology of Australian immigrant and aboriginal languages (pp. 43–62). Australian National University Press.

- Transcript of Proceedings. (2004). Couchy v Del Vecchio 520. HCATrans.

- Transcript of Proceedings. (2019). R v danny Lim. Magistrate Milledge.

- Trollip, H., McNamara, L., & Gibbon, H. (2019). The factors associated with the policing of offensive language: A qualitative study of three Sydney local area commands. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 31(4), 493. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2019.1639591

- Wajnryb, R. (2005). Expletive deleted: A good look at Bad language. Simon and Schuster.

- Walsh, T. (2017). Public nuisance, race and gender. Griffith Law Review, 26(3), 334. doi: 10.1080/10383441.2018.1449055

- Watego (formerly Bond), C., Mukandi, B., & Coghill, S. (2018). ‘You cunts Can Do as You like’: The obscenity and absurdity of free speech to blackfullas. Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 32(4), 415. doi: 10.1080/10304312.2018.1487126

- White, R. (2002). Indigenous young Australians, criminal justice and offensive language. Journal of Youth Studies, 5, 21. doi: 10.1080/13676260120111742

- Wiles, K. (2014). Swearing: The fascinating history of our favourite four-letter words. The New Statesman, February 18, 2014. https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/02/swearing-fascinating-history-our-favourite-four-letter-words.

- Williams, P. (2020). The dictionary of lost words. Affirm Press.

- Wilson, A. (2010). Andrew Johns resigns as New South Wales coach after racist comment. The Guardian, June 13, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2010/jun/13/andrew-johns-resigns-greg-inglis.

- Wilson, P. (1978). What Is deviant language? In P. Wilson, & J. Braithwaite (Eds.), Two faces of deviance: Crimes of the powerless and the powerful. University of Queensland Press.

- Wootten, H. (1991). The royal commission into aboriginal deaths in custody. AGPS.

Legislation

- Summary Offences Act 1923 (NT).

- Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW).

Cases

- Ball v McIntyre (1966) 9 FLR 237.

- Brokus v Brennan [2022] NTSC 54.

- Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971).

- Commissioner of Police v Anderson (1996) NSWCA 116.

- Del Vecchio v Couchy (Unreported, Brisbane Magistrates Court, Magistrate Herlihy, 7 December 2000).

- Dowse v State of New South Wales [2012] NSWCA 337.

- DPP v Carr (2002) 127 A Crim R 151.

- Ferguson v Walkley (2008) 17 VR 647.

- Green v Ashton [2006] QDC 8.

- Heanes v Herangi (2007) 175 A Crim R 175.

- Hortin v Rowbottom (1993) 68 A Crim R 381.

- Lim v The Queen [2017] DCR 231.

- Jeffs v Graham (1987) 8 NSWLR 292.

- Jolly v The Queen [2009] NSWDC 212.

- McCormack v Langham (Unreported, Supreme Court of NSW, Studdert J, 5 September 1991

- Mogridge v Foster [1999] WASCA 177.

- Monis v The Queen (2013) 249 CLR 92.

- Police v Butler [2003] NSWLC 2.

- R v Brown [2013] QCA 185.

- R v Lim (Unreported, Downing Centre Local Court, Magistrate Milledge, 30 August 2019).

- R v Penguin Books (1961) Crim LR 176.

- Saunders v Herold (1991) 105 FLR 1.

- State of New South Wales v Beck [2013] NSWCA 437.