Abstract

In February 2017, Sweden’s oldest and largest professional Sámi ensemble, Giron Sámi Teáhter, produced the politically outspoken production CO2lonialNATION – A Theatrical Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a collective documentary theatre project that assembled anonymized witness testimonies from all over Sápmi. Using CO2lonialNATION as a highly representative example of Giron Sámi Teáhter’s repertoire, this essay highlights the decolonial labour of contemporary Sámi performance. It teases out the dramaturgical implications of mounting a theatrical truth and reconciliation commission by exploring the preparation and research process, the embodied performance onstage including the script, spatial arrangement, and relationship between performers and audiences, as well as the production’s roots in Sámi visual, material, and musical culture. Indebted to the work of political sciences and Indigenous studies scholar Rauna Kuokkanen, the essay’s core argument suggests that Sámi performance constitutes a gift that foregrounds Indigenous knowledges, rehearses and enacts political change and social justice, and engenders relationships that are characterized by respect, responsibility, and reciprocity. Finally, the essay ponders some of the ethical responsibilities and methodological challenges that a non-Sámi spectator faces when witnessing a performance that outlines the manifold legacies of settler colonialism.

Sitting on red metallic chairs in front of a large stylized map depicting the mountains, rivers, and lakes of Sápmi – the homeland of the Sámi people that stretches across the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, and Finland all the way to the Kola Peninsula in Russia – three actors solemnly recite a poem together in Northern Sámi:

Look around.

Everywhere, there is a story.

Thousands of impulses for stories

piercing you, impulses you have

experienced, lived through; that have

been manipulated and planted in you,

suggested for you, left to be interpreted;

all of them around you, stretching away

into infinity.Footnote1

The poem, whose opening lines are reproduced here in English translation, was conceived by the Skolt Sámi film and theatre director Pauliina Feodoroff and served to establish some of the questions explored by her politically charged production CO2lonialNATION – A Theatrical Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which opened in February 2017.Footnote2 Feodoroff, who has a degree from the Helsinki Theatre Academy, is an outspoken activist whose work combines art and politics, protests the industrial exploitation of Sápmi, and underscores ecological restoration and biodiversity. She has also been the former president of the Saami Council, a non-government organization founded in 1956 that represents all the Sámi people by bridging political divisions and promoting Sámi rights and culture in and across the four nation states.Footnote3

CO2lonialNATION was a collective documentary theatre project that assembled anonymized oral histories and witness testimonies from all over Sápmi to explore the manifold legacies of centuries of settler colonialism in Northern Europe. A key impulse for the project was provided by the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), whose final report was published in 2015.Footnote4 As hinted at in the intriguing spelling, CO2lonialNATION (pronounced: Colonial Nation) confronted multiple intersecting colonial realities that the Sámi people face, including the negative effects of the geopolitical borders that continue to divide Sápmi, the struggle for self-determination, and the impact of global climate change on their land and living conditions. An equally prominent dimension of CO2lonialNATION, as manifested in the opening lines, was the demand to tell one’s own story on one’s own terms and to give a voice to colonized people whose stories, experiences, and identities are often manipulated, commercialized, or silenced by majoritarian society.

Staging Contemporary Sámi Decolonization

CO2lonialNATION was staged by Sweden’s oldest and largest professional Sámi ensemble, Giron Sámi Teáhter, which has its administration and production base in Kiruna/Giron, an industrial town located 145 km north of the Arctic circle. Giron Sámi Teáhter is a touring company whose origins may be traced back to 1971, when a group of young Sámi activists staged a play to protest the damming of a lake by a Swedish hydroelectric power company. The theatre’s mandate is ‘to carry out professional performing arts based on the Sámi culture and identity and to promote the Sámi languages by raising current issues’.Footnote5 For the last three decades, the theatre has been actively lobbying to be awarded official status as a fully state-funded National Sámi Theatre, which would result in a more secure funding stream that, in turn, would allow for an increased production and touring schedule, as well as the additional hiring and training of young Sámi talent.Footnote6

Taking CO2lonialNATION as a highly representative example of Giron Sámi Teáhter’s repertoire, this essay seeks to highlight how contemporary Sámi performance in the Swedish part of Sápmi confronts the legacies of settler colonialism and constitutes a vital part of the decolonial struggle towards Sámi self-determination. Indebted to the work of political sciences and Indigenous studies scholar Rauna Kuokkanen, explained further, I propose conceptualizing the labour carried out by Sámi performers as a gift.

Although I limit my discussion to one specific theatre and one individual production to illustrate the artistic, political, and pedagogical importance of contemporary Sámi performance, I am equally invested here in anchoring this example in a broader historical and political context. Rather than analyzing the rich and multifaceted performance cultures cultivated by Giron Sámi Teáhter as regionally or nationally isolated, I conceptualize them from what literature scholar Harald Gaski designates a ‘pan-Sami perspective’. Gaski not only acknowledges ‘the substantial internal differences that exist between the different languages’ but also argues for ‘the significance and necessity of seeing Sami culture as one culture with common foundational values’.Footnote7 As demonstrated by CO2lonialNATION, Giron Sámi Teáhter manages to represent different Sámi language groups and respect contextually situated experiences of colonialism while simultaneously defying the geopolitical borders implemented by the four nation states to celebrate pan-Sámi cultural expressions, historical traditions, and modes of resistance.

Finally, my interest here lies in further opening up the discussion of these cross-border creative practices and influences by examining the impact of Canada’s TRC on CO2lonialNATION. Such a circumpolar approach to Sámi performance is meant to flout the geopolitical boundaries imposed by settler colonial nation states, honour the mutual political and artistic influences of Indigenous communities across the Arctic, and foreground contemporary Sámi performance as a prominent dimension of the decolonial processes that are unfolding across the circumpolar North.

As a Non-Indigenous Scholar

To achieve my objectives, I subscribe to a methodology of decolonization, that is, ‘a continuous process of anti-colonial struggle that honours Indigenous approaches to knowing the world, recognizing Indigenous land, Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous sovereignty’.Footnote8 A decolonizing approach, crucially in this context, also interpellates western researchers into engaging in ‘research [that] can be used for social justice’.Footnote9 The essay is written from the perspective of a white European who immigrated to Sweden as a young adult and thereafter spent a significant number of years living and working in Canada, where I witnessed the ongoing impact of the TRC on society and, more specifically, the performing arts and theatre scholarship.Footnote10 Upon my return to Sweden soon after the publication of the Commission’s final report in 2015, I was struck by the prevailing scholarly lack of knowledge of Indigenous performance in the country. My aspiration is therefore to advocate for the political and pedagogical importances of the labour of Sámi cultural workers and facilitate knowledge of their artistic practices, while simultaneously challenging my own academic discipline, which has marginalized Sámi performance in its limited framing of ‘Swedish’ theatre and transmission of knowledge to students.Footnote11

This approach is indebted to Kuokkanen’s rich scholarly work on Sámi self-determination, which prescribes a consistent decolonial methodology that makes room for Indigenous systems of knowledge in western universities and emphasizes the social, moral, and academic responsibility of western scholars to help implement the necessary changes for a broader and genuinely diverse university.Footnote12 According to Kuokkanen, ‘it is up to the academy to do its homework and address its own ignorance so that it will be able to recognize and give an unconditional welcome to indigenous peoples’ worldviews and philosophies’.Footnote13 ‘Doing one’s homework’, in turn, requires a recognition of the narrow understanding of what constitutes knowledge upon which western universities base their curricula and research programmes. To oppose the ‘epistemic ignorance’Footnote14 that has also left its trace on the discipline of theatre and performance studies, I rely on Kuokkanen’s notion of ‘the gift’, which she suggests as a means to highlight Indigenous forms of knowledge and encourage relationships that are characterized by respect, responsibility, and reciprocity. Propelled by a drive to derail intellectual discrimination, Kuokkanen argues for ‘a new paradigm based on the logic of the gift as it is understood in indigenous thought. […] The logic of the gift foregrounds a new relationship – one that is characterized by reciprocity and by a call for responsibility toward the “other”’.Footnote15 Following Kuokkanen, I propose approaching Sámi performance as a gift to embrace the relationships and responsibilities that this denotes. Accepting this gift means to treat it respectfully, continue to educate myself, work in close dialogue with Sámi performing artists, and circulate this gift to my non-Sámi colleagues and students, most of whom have never been exposed to Sámi history and culture.

A decolonial methodology requires a continuous reflection on how the research is intended to benefit and be relevant for the community, in this case, Giron Sámi Teáhter and its audiences.Footnote16 As a theatre scholar invested in social justice, I intend to argue for the political, cultural, and pedagogical contributions of contemporary Sámi performance and help spread knowledge of Sámi artists’ decolonial labour by inserting contemporary Sámi performance into national and international academic discourses, particularly, although not exclusively within theatre and performance studies, and do so in dialogue with Giron Sámi Teáhter.

The importance of respectful relationships – often denied to Indigenous peoples – is also underlined by Māori Indigenous Education scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith who states: ‘Through respect the place of everyone and everything in the universe is kept in balance and harmony. Respect is a reciprocal, shared, constantly interchanging principle which is expressed through all aspects of social conduct’.Footnote17 Performance, perhaps more than any other art form, is about mutual relationships, respect, trust, and communication, as well as affective and intellectual exchanges, which, I believe, makes it particularly suitable as a decolonial tool of protest. As a result of the generosity and hospitality of the artists and staff at Giron Sámi Teáhter, I have been able to learn from them through extended guest visits that allowed me to follow rehearsal processes for several productions in recent years, talk to key Knowledge Holders, and establish an ongoing dialogue that also extends to inviting guest speakers to my courses. A key imperative is to make room for Indigenous knowledge by centring the Sámi performing artists’ experiences and expertise. In this essay, I purposefully offer numerous direct quotations by the involved artists, some of whom I also interviewed, to locate their voices and experiences front and centre.

Equally important here is to highlight the importance of and credit the contributions made by Indigenous scholarship, which frames this article. Sámi studies (Sámi dutkan) is a vibrant academic discipline, but as Gaski reminds us, Sámi methodologies also need to be seen as part of Indigenous studies on an international scale.Footnote18 This argument is particularly relevant here, as I trace the influence of Canada’s TRC on Giron Sámi Teáhter and rely on Indigenous literature produced in various contexts, including Turtle Island.Footnote19 Still, there are methodological implications and challenges when writing about Sámi performance as a non-Indigenous scholar, including a continuous critical problematization of my own positionality, its potential contributions and limits, and the question of how to approach a production ethically, one that is explicitly designed to attack the realities of settler colonialism.

Ethical Witnessing and Resistance to Colonial Consumption

Considering the academy’s historical damages done to Indigenous peoples through both erasure and exploitation, Smith cautions that ‘indigenous research is a humble and humbling activity’.Footnote20 Humbling oneself is also, to a large extent, inspired by the actual production CO2lonialNATION that purposefully boycotted the colonial gaze, refused to feed into narratives of Sámi victimhood, and set the terms for its own truth and reconciliation commission within the first 5 min. Directly after the opening poem, actor Elina Israelsson stepped forward to address non-Sámi audiences in Swedish and to thank them for attending the performance. The ritualistic act of welcoming audiences into the performance space that would be shared for the duration of the event was an act of generosity. Translating this generosity into a scholarly context provokes both a sense of discomfort and humility because it serves as a painful reminder of the inhospitable attitude of western universities vis-à-vis Indigenous knowledges and students, accurately summarized by Kuokkanen: ‘The academy seems inhospitable, if not openly hostile, to many indigenous people for three main reasons: lack of relevance, lack of respect, and lack of knowledge about indigenous issues’.Footnote21 In contrast, CO2lonialNATION was offered as a gift. Accepting this gift also meant honouring the responsibilities that came with this gifting. Israelsson asked non-Sámi audiences to maintain a respectful distance and realize that catering to them was not the primary concern of the production: ‘Colonization is not a shared experience between the one who is colonizing and the one who is subjected to it. We have two entirely different roles in this history’.Footnote22 Israelsson further explained the lack of Sámi visibility in mainstream culture and discourse, which is why the performance marked an intervention: ‘We’re talking about our shared experience as a people, as Sámi. And you are welcome to share our shared experience with us, to witness. And maybe this can become a shared experience, the fact that we are sharing’. Actor Sarakka Gaup then proceeded to welcome the rest of the audience in Sámi and English, repeatedly reassuring them that: ‘I welcome you and I love you’, and briefly explained the influence of Canada’s TRC on the project.

What does it mean to be invited as a witness? How does one prevent the act of witnessing from turning into the voyeuristic consumption of a spectacle of victimhood? And what does it mean to be accountable as a scholar who witnesses the narratives that are conveyed by a truth and reconciliation commission? With particular reference to the Northwest Coast tradition in Canada, settler scholar of Indigenous literature David Gaertner warns of falsely universalizing the understandings and implications of the act of witnessing for Indigenous communities and emphasizes that ‘responsibility and action […] must go hand-in-hand with the passive act of receiving information’.Footnote23 His colleague Sam McKegney suggests that settler scholars need to realize that they cannot simply refrain from getting involved as ‘silence is not an apolitical stance’ and proposes that ‘ethical witnessing of trauma involves working toward the ideological and political changes that will create conditions in which reconciliation becomes possible’.Footnote24

The ethics and responsibilities of witnessing Indigenous testimonies in performance were key concerns articulated in CO2lonialNATION. From the start, the cast highlighted its own Indigenous perspective and encouraged critical reflections about privilege and positionality. Audience members were compelled to take a moment and ponder their presence in this shared performance space and their own identification with and their investment in this specific theatrical event. Non-Sámi audiences were interpellated as witnesses and asked to remain humble but were not abdicated of any responsibility. Through this kind, yet firm gesture, Feodoroff and her cast immediately rescued CO2lonialNATION from potentially becoming a spectacle to be consumed by majoritarian society. Métis artist and visual arts scholar David Garneau accurately summarizes the voracious appetite of the unexamined colonial gaze:

The colonial attitude is characterized not only by scopophilia, a drive to look, but also by an urge to penetrate, to traverse, to know, to translate, to own and exploit. The attitude assumes that everything should be accessible to those with the means and will to access them; everything is ultimately comprehensible, a potential commodity, resource, or salvage.Footnote25

Feodoroff’s direction of CO2lonialNATION, as I demonstrate throughout the essay, evaded the colonial gaze and desire for traumatic spectacle by purposefully recentring the Indigenous perspective as the primary point of reference and speaking to Sámi audiences in their own language to explore historical and contemporary relationships critically among Sámi and between the Sámi and the colonial state. The production engendered a public forum and safe space for Sámi experiences to be staged in a theatrical truth and reconciliation commission, performing the labour that should be carried out by the national government and parliament.

Labouring Towards a National Truth Commission

The Sámi Parliament of Sweden (Sámediggi) has long advocated for the need for a national Truth Commission (sanningskommission) to investigate and document the colonial abuses endured by the Sámi over centuries as well as the negative impact of the geopolitical borders dividing the Sámi people.Footnote26 The impact of these historically shifting borders has ranged from double taxation and impediments related to cross-border reindeer herding, to enforced dislocations and the separation of entire families and communities. Sámi cultural workers to this day have to negotiate different political regulations, legislative systems, and national funding bodies, which create unequal working conditions and complicate collaborations across borders.Footnote27

The colonization of Sápmi started gradually with Nordic and Russian monarchs laying claim to Northern territories and collecting taxes in the late Middle Ages. It expanded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the arrival of farmer settlers, business people looking for precious metals, and missionaries who forcefully converted the Sámi to Christianity and tried to erase any traces of Shamanism and Animism. It peaked in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the implementation of nationalist and assimilation politics, forced displacements, and scientific racism, including anthropometric observations.Footnote28 In Sweden, the government’s official Sámi policy implemented a devastating ‘divide-and-conquer’ politics that decided that ‘real’ Sámi had to be reindeer herders and live a nomadic existence, whereas those Sámi whose primary mode of subsistence was farming or fishing were to be assimilated into Swedish citizenship. All of these political developments resulted not only in the loss of language and cultural identity for many Sámi but also in internal divisions and conflicts that continue to haunt present-day Sámi societies.Footnote29

In November 2021, almost 5 years after the opening of Giron Sámi Teáhter’s production CO2lonialNATION, the Swedish government officially announced its intent to inaugurate a Truth Commission to ‘chart and scrutinize the policy pursued towards the Sámi from an historical perspective and its consequences for the Sámi people’ and propose ‘measures that contribute to redress and promote reconciliation’.Footnote30 Since the term reconciliation is contested among Indigenous activists and scholars, Sweden conducts a Truth – as opposed to a Truth and Reconciliation – Commission.Footnote31 The aim is to publish a final report in December 2025.

Sámi Testimonies and Performance

For Giron Sámi Teáhter, CO2lonialNATION marked an activist intervention to speed up the process. Giron Sámi Teáhter’s artistic director, Åsa Simma explained how exasperated she felt by all the political delays for a national Truth Commission, which prompted the need for her and Feodoroff to take matters into their own hands: ‘We started in August [2015], with the attitude if you politicians are not going to do it, we are going to do it’.Footnote32 In addition to being an actor, playwright, and dramaturge, Simma is a highly accomplished yoik performer.Footnote33 Simma received her education at Tuukkaq Teatret in Denmark and, over the course of her career, has cultivated an international outlook of Sámi performance through collaborations with artists from all over Sápmi in addition to Indigenous performers from Canada, Greenland, Mongolia, and Australia. Simma has also influenced the company’s direction by establishing a repertoire with a pronounced decolonial agenda and, in the process, has promoted the revitalization of Sámi languages.Footnote34

To prepare for the project, Simma and Feodoroff, accompanied by the two creative writers Niillas Holmberg and Simon Issát Marainen, travelled across Sápmi and lived in six different locations under an extended period of time, getting to know locals, and talking to Knowledge Holders. While collecting interviews and witness testimonies across Sápmi, the ensemble was inspired by the Canadian TRC, whose methodology was based on town hall hearings. They were also accompanied by a psychologist affiliated with the Sámi Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Mental Health and Substance Use (SANKS). This psychologist was specifically trained in matters pertaining to Sámi people’s psycho-social health and was present for support and additional conversations with interviewees. Simma later revealed the arduous process of collecting stories for a theatrical truth and reconciliation commission:

For my part and as a cultural worker, I must say that it has been an extremely important journey. Getting to know the Sámi and hearing all the sad stories – I am still in tears now. It was not an easy journey but it was an important one. […] We often cried in the evening because things were so tragic. Then we kept saying: ‘we need to do this, we need to do this … ’. That’s why I’m telling you, so you know, that it’s not just theatre, I want to do so much more. It’s community building, building a society, that’s what I’m interested in.Footnote35

For CO2lonialNATION, the personal narratives were re-arranged into a dramatic collage and performed by three professional performers: Sarakka Gaup, Elina Israelsson, and Mio Negga.Footnote36 Gaup has a degree from the Oslo National Academy of the Arts and a rich acting experience from both Giron Sámi Teáhter and Beaivváš Sámi Našunálateáhter, the Sámi National Theatre of Norway. Israelsson is a musician and actor who made her debut at Giron Sámi Teáhter in 2015. Negga works foremost as a musician, producer, and composer who fuses yoik with contemporary electropop. During performances, Negga often acted as an interviewer or facilitator, while Gaup and Israelsson impersonated a number of different witnesses who narrated testimonies of colonial experiences (see ). These individual narratives addressed heavy issues such as the loss of language, land, and identity; experiences of physical and sexual assault; depression and psycho-social illness caused by systemic racism; suicide attempts; and the destructive effects of the forestry, mining, and hydroelectric industries on reindeer husbandry. Crucially, they also conveyed Indigenous resistance, celebrated circumpolar arts, and proudly promoted Sámi languages and culture.

Image 1. Sitting in front of a stylized map of Sápmi, Mio Negga (right) acts as a facilitator for the witness testimonies offered by Elina Israelsson (centre) and Sarakka Gaup (left), Photograph by Ilkka Volanen. © Giron Sámi Teáhter.

Smith highlights the pain and performativity of giving testimony: ‘Indigenous testimonies are a way of talking about an extremely painful event or series of events. […] A testimony is also a form through which the voice of a “witness” is accorded space and protection. It can be constructed as a monologue and as a public performance’.Footnote37 She further notes the political implications of giving testimony to call out colonial crimes and thereby recentre Indigenous peoples’ experiences of past events: ‘On the international scene it is extremely rare and unusual when indigenous accounts are accepted and acknowledged as valid interpretations of what has taken place. And yet, the need to tell our stories remains the powerful imperative of a powerful form of resistance’.Footnote38

During the performance, all interviews and oral histories were anonymized, except for one testimony that each of the three actors wrote and incorporated into the production. Gaup paid tribute to her father, Ailo Gaup (1944–2014), a key figure in Sámi literature whose works, including In Search of the Drum (Trommereisen, 1988) and The Shamanic Zone (Sjamansonen, 2005), have been translated into English, French, German, and Polish. Gaup explains how her father was taken away from his mother as a baby and adopted by a Norwegian family. Ailo eventually managed to rediscover and reclaim his origins, but, in spite of being one of the most acclaimed Sámi authors, he was never fully proficient in the Sámi language and wrote his major works in Norwegian. Gaup’s testimony – tellingly narrated in SámiFootnote39 – was not only a declaration of love for her father and a celebration of a seminal Sámi artist and activist but also illustrated how a young generation of Sámi is working hard to regain and preserve their language and cultural heritage. Israelsson also took inspiration from her father, whom she impersonated in a scene that, in Swedish, recounted a traumatic memory of how he had once been forced to shoot one of his own reindeers that became caught in a toxic tailings dam adjacent to an iron ore mine. The scene viscerally captured the pain felt by a reindeer herder who could not save one of his animals from drowning. Given the central position of the reindeer in Sámi society and culture, the scene also illustrates the damages of industrial exploitation and the threat it poses to the Sámi economy, lifestyle, and cosmology.

The stage, as cultural historian Veli-Pekka Lehtola argues, offers the means to take control of Sámi self-representation, promote Sámi languages, negotiate cultural identities, and foster positive self-identification.Footnote40 Through the means of performance, Giron Sámi Teáhter allows intergenerational traumatic memories and narratives to enter into public discourse, in a safe space in which many Sámi are present and in which Sámi is often the primary means of communication. Switching between short scenes in Swedish and extended segments performed in Lule Sámi (julevsámegiella) and Northern Sámi (davvisámegiella) – in addition to incorporating elements from Southern, Pite, Ume, and Skolt Sámi – CO2lonialNATION manifested and embraced Sámi visibility and presence, which in turn acted as a manifestation of cultural sovereignty.Footnote41 Performing in Indigenous languages that governments and the national Evangelical Churches systematically tried to eradicate through assimilation techniques, enforced separation of families, and shaming devices marks a striking decolonial statement and offers a means for Sámi cultural performers to regain control over their representation and tell their story on their own premises. The act of performing in Sámi re-centres Sámi epistemologies and dictates how traumatic memories are communicated, how the experience of colonialism is transmitted, and to whom these narratives are directed. Feodoroff explains that: ‘What we have tried to do in this performance is that we speak as Sámi to our own people, we talk about all that has happened to avoid our identity being reduced to mere victims, the target of colonization, [to show] that we are so much more’.Footnote42

Swedish or Finnish surtitles, however, were incorporated to facilitate comprehension for non-Sámi speaking audiences. This consistent multilingualism is a vital aspect of the labour of Sámi performance, which addresses significantly heterogeneous audiences in terms of language skills, historical knowledge, and self-identification not only throughout Sápmi but also while touring in southern Sweden and Finland. In the words of Lehtola, Sámi arts need to perform the ‘the dual role’ of speaking ‘with two mouths’, which is ‘a familiar tradition for the Sami, already from colonial times’.Footnote43 Considering the history of Swedish and Nordic settler colonialism, the use of surtitles is part of Giron Sámi Teáhter’s generosity vis-à-vis majoritarian audiences and should be considered as part of the gift offered by a hospitable performance space. There is, however, also a political necessity driving this choice, as many Sámi, whose parents or grandparents are survivors of residential Nomad schools, lost the ability to speak or understand their own language.

In addition to personal witness testimonies, scholarly research and documents were incorporated into the production. Negga read verbatim extracts from the White Paper Project that helped ground the collected personal narratives in an historical context and tease out the specificities of Swedish and Nordic settler colonialism. Published in 2016, the White Paper Project is a research endeavour that was initiated by the Church of Sweden and executed in collaboration with Umeå University to explore the Church’s complicity in the colonization of the Sámi ever since Lutheran missionaries forcefully converted the Sámi in the early seventeenth century and eradicated their own spiritual institutions based on Animism and Shamanism.Footnote44 A key area explored by the White Paper Project, and from which Negga quoted, is how the Church contributed to the segregation of the Sámi people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with the implementation of Nomad schools.Footnote45

Through the implementation of legal paragraphs – in particular, the 1913 Nomad School Act and the 1928 Reindeer Grazing Act – the Swedish state, with the active support of the Church of Sweden, realized a divide-and-conquer politics, which led to generations of Sámi losing not only their cultural identity and language but also their lands and legal rights. As stipulated in these paragraphs – and as briefly addressed above – only nomadic reindeer herders were recognized as Sámi. In accordance with the reigning paternalistic attitude vis-à-vis Indigenous peoples, they allegedly had to be sheltered from too much influence by western civilization. Hence, their children would only receive a low-quality, 6-year education to prepare them for a nomadic lifestyle, while the children of settled Sámi would be assimilated into Swedish society.Footnote46 In the Nomad schools, which the Church administered until their reformation in the 1960s, Sámi children were often forbidden from speaking their language, taught that they were racially and intellectually inferior, and subjected to various forms of physical and emotional abuse.Footnote47 Additionally, the staff and teachers at the Nomad schools welcomed scientists from the State Institute for Racial Biology, instigated in 1922 and running until 1958, who, driven by Social Darwinist ideologies and obsessed with fears of racial degeneration, subjected the Sámi children to anthropometric observations.Footnote48 In performance, Gaup expressed grief: ‘The racial biologists were here. They humiliated people. They measured everyone who lived here. My grandfather, my grandmother, my grandfather’s mother. Everybody. In 1923’. Negga added: ‘In Finland, skulls were still measured as late as 1969’.

The production’s clever juxtaposition of documented historical and contemporary injustices with personalized narratives describing emotional sufferings painted a complex picture of the intergenerational traumas caused by settler colonialism. In a review of CO2lonialNATION, the Norwegian performance scholar Ragnhild Freng Dale suggested: ‘The theatre thus becomes both a space for therapy and collective processing, a call to take control of one’s own history, and a political contribution to a debate on who should have the right to define history’.Footnote49 This attempt to reclaim authority over their own historiography and their own representation is a central aspect of the labour of Sámi performance.

A Visualized and Spatialized Witness Testimony

The aesthetic dimension of Giron Sámi Teáhter’s theatrical truth and reconciliation commission extended to the performance space, courtesy of Vihtori Rämä and Ilkka Volanen, which was arranged in an oval shape, enhancing the proximity between performers and spectators. This near-circular arrangement was also a reflection of Indigenous dramaturgies that highlight holistic thinking and marked a spatial manifestation of philosophies that seek to create ‘harmony and balance with the wider community’ by establishing ‘communal relationships, grounded in oral traditions, and tied to sacred relationships with the land’.Footnote50

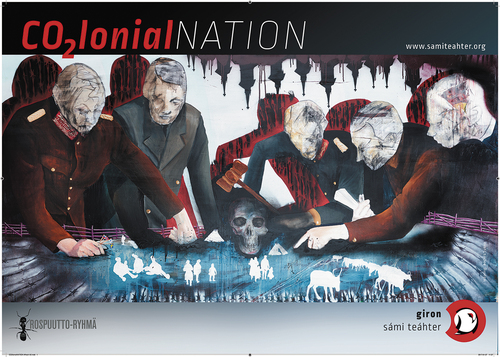

One end of the oval-shaped stage was dominated by the previously mentioned stylized map of Sápmi. On the opposite side hung an almost Expressionist collage painting by the Sámi artist Anders Sunna. This painting also served as the promotional poster for the production and as the artist’s own visual witness testimony about the damage rendered by colonial borders and politics (see ). Sunna graduated from the University College of Arts, Crafts, and Design in Stockholm in 2009 and is one of his generation’s most influential Sámi artists, exhibiting in both national and international contexts. His art depicts contemporary forms of racism against the Sámi and castigates the tacit power mechanisms enacted by government agencies. State bureaucrats are often depicted wearing a brown military uniform and a red armband, a not-so-subtle allusion to Nazi outfits. Visual arts scholar Moa Sandström describes Sunna’s work as ‘a valve for anger and frustration’.Footnote51 Sunna’s work also protests how his own family has been penalized by the segregation of the Sámi people and lost their rights of reindeer husbandry due to the Swedish state’s Sámi policy. The artist himself claims: ‘People say that in Sweden we live in a democratic society; this is not something which I experience. I am a stateless person in a dictatorship’.Footnote52 Other recurring motifs in his large-style paintings, prints, collages, and street art works include chilling allusions to racial biology, violently enforced dislocations, and hate speech. Cultural scholar Anne Heith asserts that Sunna’s art ‘is not a heart-warming tale of progression and inclusion, but the narrative of a colonized, indigenous people subjected to racism and enforced relocations’.Footnote53

Image 2. Artist Anders Sunna’s visual testimony and promotional artwork for the production. © Anders Sunna and Giron Sámi Teáhter.

Sunna’s painting for CO2lonialNATION viscerally captures the division of Sápmi by the four nation states. A group of sinister-looking white male figures lean over a schematic map demarcated by wooden and barbed-wired fences and complete with scaled-down people, reindeer, and goahtis (Sámi huts or tents). The men’s clothes and accessories identify them as figures of authority. The judge carries a hammer, while the military general’s jacket is decorated with marks of honour, and politicians wear standard dark three-piece suits. These figures project blood-red shadows onto the background. From the top of the painting, church towers hang upside-down and drip blood, a reference to the religious trials and forced conversion of the Sámi to Lutheranism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The middle of the painting is dominated by a large human skull, representing the anthropometric observations to which Sámi people were subjected by racial biologists. Finally, one of the characters holds miniature national flags of Russia, Norway, Finland, and Sweden in his hand. Sunna’s painting constituted a visual frame for the entire production of CO2lonialNATION and is a formidable representation of how the four colonial powers, supported by the national churches and the medical establishment, drew up geopolitical borders right through Sápmi that, to this day, have palpable consequences for the Sámi. As Sunna states:

They make a difference between the Sámi in Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Russia, and also between Southern, Northern, Lule [Sámi], and blah blah. […] The state does not want a united people. Because then you gather to fight united against a common enemy.Footnote54

The central prop that distinguished the performance space was a white crystal sphere filled with water and placed on a pedestal centre stage. The sight and sound of water dripping from the sphere onto the stage floor became a visceral materialization of the ecological changes happening in the circumpolar North (and South) and the irreversible effects these are having on the planet. It is in the polar regions where average temperatures are rising at a faster pace than any other place on the earth. As a result of melting layers of snow and ice (including glaciers and permafrost), to say nothing of forest fires in recent years, both the terrestrial and marine ecosystems are changing rapidly, which in turn has tremendous effects on the food, water, and health safety of the communities and people living in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions.Footnote55

This simple, yet potent, gesture of drawing attention to climate change with a leaking crystal sphere helps tease out an additional dimension of Sámi performance as a gift, namely its devotion to sustainability and opposition to short-sighted capitalist gains. Sámi activists, along with other Indigenous people and people living in the Global South, are on the frontlines of global climate activism, both as Knowledge Holders of sustainable relationships with the environment and as protesters against industrial exploitation of land and water resources.Footnote56 In a short film that contains excerpts from CO2lonialNATION and forms part of the transnational video project ‘Climate Justice in Sápmi’, Gaup and Negga succinctly articulate the predicament of the Sámi who have always sought to live in harmony with nature for centuries and whose land and water resources are being exploited by national and international mining companies, forestry industries, and hydroelectric power plants in search of short-sighted financial profits.Footnote57

To illustrate my argument further about sustainability and opposition to capitalist exploitation, let us compare two statements by Simma and Kuokkanen that, independent from each other, capture the political and philosophical dimensions of the gift. In an interview, Simma emphasizes her agenda as artistic director of Giron Sámi Teáhter and the utopian potential of the performing arts as an alternative to corporate industrialism:

I would like the Sámi to work with us instead of in the mine. In a Sámi environment. Yes, I want to bring my people back home, and the theatre is a good home. Not everyone needs to stand onstage or write scripts, there are so many functions. It is an open space where a lot is allowed.Footnote58

Kiruna/Giron is home to the largest active iron ore mine in Europe. Nightly underground explosions rattle and shake significant parts of the town, which, because of massive networks of tunnels, has become so unstable that its core is being demolished and relocated 3 km away through an extensive urban redesign process. Simma conjures the stage as an alternative space to the values of market capitalism as represented by this mine. Moreover, her utopian understanding of theatre, I suggest, manages to convey essential dimensions of Kuokkanen’s notion of the gift. Kuokkanen opposes the neoliberal commodification of human lives and posits the gift as a potential alternative to capitalism’s seemingly endless craving for more resources and profits. Of central importance for her is the recognition and restoration of a mutually respectful relationship between humans and the environment:

[T]he gift is a reflection of a particular worldview, one characterized by the perception that the natural environment is a living entity which gives its gifts and abundance to people provided that they observe certain responsibilities and provided that those people treat it with respect and gratitude. Central to this perception is that the world as a whole comprises an infinite web of relationships, which extend and are incorporated into the entire social condition of the individual.Footnote59

Kuokkanen highlights the holistic and intimate relationships between humans and land and reminds us that the gift is intimately tied to Indigenous philosophies and practices of sustainability that emphasize both collective and individual responsibilities for the well-being of the community and the environment. Giving and accepting the gift is not motivated by short-sighted personal interest nor is it a commodity deployed in an economic exchange that chases the accumulation of capital. Instead, the gift opens up new spaces to establish and sustain relationships that are characterized by reciprocity and accountability. Live performance is of crucial significance because, by default, it constitutes relationships and, to paraphrase Jill Dolan, carries significant potential to forge utopian communities between performers and spectators, thereby sowing seeds that may grow into future forms of social activism.Footnote60

A Refusal of Aristotelian Closure and a Dramaturgy of Healing

When Gaup announced nearly 45 min into the performance that it was time for an interval, the audience was not allowed to take a mental or emotional reprieve. Instead, a TV set was carried onstage to confront spectators with some of the consequences of the historically shifting, geopolitical borders that cut right through Sápmi. A 15-min documentary devoted particular focus to the experiences of the Skolt Sámi, of whom director Feodoroff is a member. The Skolt Sámi are an eastern language group who have traditionally lived on territories stretching from the Kola Peninsula to Lake Inari and who have been tremendously affected by twentieth-century politics. The combined effects of the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the ensuing Cold War resulted in hundreds of Skolt Sámi being relocated from the Soviet territories to the Inari region in the Finnish part of Sápmi, losing their homes, belongings, and reindeer.Footnote61

The documentary shown during the ‘interval’ of CO2lonialNATION addressed this separation of the Skolt Sámi as well as the living conditions on the Kola Peninsula during the Soviet regime when entire community structures (siidas) were eradicated, the area became a testing site for nuclear weapons, and radioactive waste was dumped into the Barents Sea. Here, Feodoroff’s direction deliberately bordered on sensory overload to exhaust the spectator. This artistic choice, I suggest, functioned as a thought-provoking political strategy to showcase how regional, national, and global politics have shaped Sámi people’s colonial experiences in different ways, with Skolt communities living with some of the most destructive consequences. By purposefully depriving audiences of the emotional and mental reprieve that an interval would have provided, CO2lonialNATION did not let them off the hook and resisted any form of cathartic closure offered by Aristotelian dramaturgy.

While extended parts of CO2lonialNATION were emotionally draining and text-heavy, yoiking and physicality also constituted important aesthetic features. A mini-soundtrack with three yoiks composed by Negga was released onto streaming and download platforms under the moniker 169, an allusion to the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention from 1989, which supports Indigenous peoples' rights of self-determination over the use of their lands, territories, and resources and which Sweden has yet to ratify. In these songs, Negga fused yoiking with electronic music, honouring an ancient tradition, and giving it a contemporary dimension. In a lighter moment, the actors also performed a lively tribute to circumpolar artists, such as the singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie from Turtle Island, the Greenlandic mask dancer Elisabeth Heilmann Blind, and the choreographer and film director Elle Sofe Sara from the Norwegian part of Sápmi. Accompanied by the sounds of rhythmic drumming, Gaup and Israelsson impersonated two children who ran across the stage and lovingly imitated characteristic features of the artists mentioned, including a highly entertaining attempt at mimicking the practice of Greenlandic mask dancing (uaajeerneq). Not only did these moments work as an effective contrast to the emotionally heavy scenes but they also constituted an acknowledgement and celebration of the labour of circumpolar artists, many of them being women. This was underlined by Israelsson’s defiant claim that Sámi arts and culture have survived despite the four colonial states’ consistent attempts to strip the Sámi of their land, social structures, cosmology, and language: ‘They have not been able to take away the arts and crafts and cultural expressions from my people’.

The celebration of circumpolar arts and the yoiks composed by Negga points to a key component of the production and, I suggest, the entire agenda of Giron Sámi Teáhter: that art and performance have a transformative agency. The Algonquian-performing artist Yvette Nolan has proposed that Indigenous performance works as metaphorical medicine to extract the poison and damage caused by settler colonialism: ‘Indigenous theatre artists make medicine by reconnecting through ceremony, through the act of remembering, through building community, and by negotiating solidarities across communities’.Footnote62 Similar sentiments were echoed by the Sámi ensemble that staged CO2lonialNATION. In a documentary on climate justice, Gaup stated: ‘We want to tell the truth, so that we can heal and move on to something better and more beautiful’.Footnote63 Feodoroff explained in a promotional interview for CO2lonialNATION: ‘For the first time in my adult life I have the chance to work within my own culture. It was a healing experience’.Footnote64 In a radio interview, Simma paraphrased the political activist and Former Grand Chief of the Four Nations Confederacy, Lyle Longclaws, to explain the objective of the production and how healing, for Indigenous peoples engaged in a decolonial process, has both an embodied and a spiritual dimension: ‘Before the healing can take place, the poison must first be exposed’.Footnote65 These wounds were exposed not only through witness testimonies but also through visual, spatial, musical, and material culture, which added to the political and artistic richness of the production.

The Affirmative Power of Duodji

Nowhere did the opposition to turning Sámi experiences into narratives of passive victimhood become more apparent and visceral than in the closing scenes of CO2lonialNATION, in which the desire to reclaim hope, agency, and cultural sovereignty received a palpable and embodied illustration. Israelsson performed a character who attempted suicide due to the constant psycho-social pressures of living under a colonial structure. She lifted the crystal sphere that constituted the main scenographic element and brought it close to her lips, as if she were poised to sip some water. Instead, she took a deep breath, bent her head downwards, and let her long hair cover the entire sphere, in an attempt to drown herself. Gaup ran to her rescue, cradled her head in her arms, and resuscitated her through massage (see ). Negga then joined them and gently put the same gákti (Sámi regalia) on Israelsson that she had worn in a previous scene that paid tribute to her father.Footnote66

Image 3. Sarakka Gaup and Elina Israelsson hold the white crystal sphere filled with water which was the central prop of the production of CO2lonialNATION. Photograph by Ilkka Volanen. © Giron Sámi Teáhter.

The scene segued into a different setting when Israelsson’s character turned to the Swedish health-care system for help. She explained the constant feelings of estrangement she experienced and how, as a result, she seemed to have lost control over her own life. Gaup impersonated a Swedish medical doctor or psychologist who was quick to diagnose Israelsson with a form of depression, thereby individualizing and pathologizing her condition. Israelsson, however, protested and explained how the political and personal are intertwined and that the root of her malaise was to be found in the ongoing colonization of Sápmi: ‘I don’t think that I’m sick. But I live in a sick situation and that’s why I get sick’. At this point, the power dynamics began to shift. As the therapist continued to prescribe a long list of psychoanalytical treatments and anti-depressive medications to cure her patient, Israelsson silently put on a large, red Sámi belt with a simple line of gold embroidery and a silver buckle. She then braided her hair and adjusted her gákti. As the therapist vanished from the stage, Israelsson addressed the audience with a closing monologue and, once again, spoke directly to Swedish spectators:

[Y]ou, a member of the colonizing culture. Our relative. Our disease is not endemic. Your culture’s disease has even infected me, even me. I don't think your disease is endemic either. But I don’t know what has infected you. You have to find out for yourself. So I’m asking you: seek care, seek help. Ask for help before you’ll destroy even more. Or cease to exist and leave the rest of us in peace. Let us recover from you.

Refusing to conceptualize trauma as a pathological condition that isolates people, Israelsson’s actions illustrated Ann Cvetkovich’s important argument to use trauma as the raw material for community-building and grassroots activism.Footnote67 To drive home her point, Israelsson put on a Sámi headgear with a red bottom and a navy-blue pointed top part, a mátjuk, which stems from the Gällivare/Jiellevárri area.Footnote68

Duodji is a craft and artistic expression that, on the one hand, creates garments and artefacts that fulfil practical necessities and, on the other hand, is closely tied to Sámi traditional knowledge, cultural practices, and spiritual values. In the words of the scholar and artist Gunvor Guttorm, ‘the concept of duodji should be understood as putting Indigenous knowledge and experience to work’.Footnote69 While duodji is deeply rooted in Sámi culture and tradition, it is also a dynamic practice that changes over space and time and thus allows for the personal artistic temperament and vision of the artist to make its mark. This dynamic aspect is apparent in the art and practice of duodji artist Anna-Stina Svakko, who created Israelsson’s stage attire (see ).Footnote70 As a professional designer, Svakko seeks to help Sámi people reconnect with their cultural identity and roots: ‘If you can make a person strong from the soul and the root, then you can strengthen an entire people’.Footnote71 The garment for Israelsson took shape in close dialogue with the actor:

I always work with a person’s roots. […] We came to the conclusion after conversations that her father’s roots should be shown. […] Because each actor got to choose a story that would be reflected in performance and hers was very strongly connected to her father. This is the scene when the reindeers have to be shot in the tailings dam and she is sitting in the helicopter.Footnote72

Image 4. Duodji artist Anna-Stina Svakko’s gákti for Elina Israelsson. Photograph by Anna-Stina Svakko. © Anna-Stina Svakko.

Another characteristic of Svakko’s work is that she uses the traditional cut and pattern of a gákti as a starting point but then pulls it into the contemporary moment and adds her own creative visions by working with modern textiles (including, for example, jeans and plastic fabrics) and embroidering Sámi words and phrases onto them. For Israelsson’s coat, she used actual Giorgio Armani textiles and embroidered ‘iellema árbbe l duosstel’ – an expression that is meant as an encouragement to be daring and literally translates into ‘life’s heritage is to dare’ – on the inside of the collar, sleeves, and hem. The idea was to empower Israelsson with the help of exclusive textiles and the embroidered statement, which onstage culminated in a final act of resistance to settler colonialism.Footnote73 Israelsson’s attire marked an act of reclaiming history and culture, bringing it into the present, not as an historical artefact to be stored or locked in a vitrine in a museum but as a living object that carried meaning and allowed for an active rediscovery of Sámi history, traditional knowledge, and cultural legacy. To bookend the production and further support this affirmation of Sámi pride, the three actors stepped forward and performed the yoik ‘Sogiid siste’ (‘Inside the birches’), a composition that Negga described as a ‘national anthem for a decolonial nation’.Footnote74

Conclusion: Sámi Performance as a Gift

In his seminal book Theatre of the Oppressed, Augusto Boal famously posits: ‘Perhaps the theater is not revolutionary in itself; but have no doubts, it is a rehearsal of revolution!’Footnote75 Years before the Swedish government instigated a national Truth Commission, Giron Sámi Teáhter’s production CO2lonialNATION constituted more than a rehearsal of how to stage a theatrical truth and reconciliation commission in an ethical and culturally sensitive way. CO2lonialNATION demonstrated how to organize such an endeavour on Sámi premises and in a way that allowed Sámi testimonies to take centre stage and circumvent any colonial desire for consuming spectacles of victimhood. As a result of the careful preparation and design of the project, the artists harnessed the form and content of their commission, offered personal testimonies in a safe space that protected the witnesses, and foregrounded consistently an Indigenous perspective that honoured Sámi knowledges, languages, and cultural traditions. As a result, the stage became a political forum to articulate relevant critiques against the historical amnesia imposed by the settler colonial states, verbalize centuries of oppression to stimulate a healing process, and propose an alternative to the twinned projects of colonial and capitalist exploitation. No matter how utopian it may sound, the combined artistic, political, pedagogical, and philosophical dimensions of contemporary Sámi performance constitute a gift that encapsulates the very necessity and contribution of theatre to the decolonial project. This decolonial labour offers an abundance of gifts to Sámi audiences and communities, not least by giving them a platform to tell their own stories and honour Indigenous values of holistic and sustainable relationships with each other and the natural environment. Additionally, this gift encourages ethical forms of witnessing Sámi performance for non-Indigenous spectators and incites a necessary, critical engagement with Swedish and Nordic settler colonialism through artistic practice, scholarly discourse, and critical pedagogy.

Notes on Contributor

Dirk Gindt is a Professor of Theatre Studies in the Department of Culture and Aesthetics at Stockholm University. He is the co-editor of the volume Viral Dramaturgies: HIV and AIDS in Performance in the Twenty-First Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018) and the author of the monograph Tennessee Williams in Sweden and France, 1945-1965: Cultural Translations, Sexual Anxieties and Racial Fantasies (Bloomsbury, 2019). Gindt’s current research, financed by a four-year grant from the Swedish Research Council, analyses Indigenous performance in the Swedish part of Sápmi.

Acknowledgments

I thank the two anonymous reviewers for their generous feedback and astute suggestions, as well as Dr Sarah Thomasson for careful editorial guidance. I am indebted to the generosity of Åsa Simma, who continuously shares her rich knowledge and contact network, in addition to offering ethical advice. My gratitude goes to all the artists and staff at Giron Sámi Teáhter for their hospitality and trust. I thank Anna-Stina Svakko for kindly granting me an interview and permission to reproduce one of her images. I am also grateful to Anders Sunna for allowing me to reproduce his artwork for CO2lonialNATION. Finally, I express my appreciation for John Potvin’s and Linda Morra’s intellectual encouragement and editorial skills.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Pauliina Feodoroff, ‘Look Around’, CO2lonialNATION playbill, Giron Sámi Teáhter, 2017, 33-35 (33). Archived at Giron Sámi Teáhter.

2. The opening of CO2lonialNATION took place on 10 and 11 February 2017 in conjunction with the twenty-first Saami Conference that was held in Trondheim/Tråante in the Norwegian part of Sápmi. The conference celebrated the 100-year anniversary of the first Sámi National Assembly organized by the activist Elsa Laula Renberg, which marked a key event in the political organization of the Sámi people across national borders.

3. In 2022, Feodoroff, along with the visual artist Anders Sunna and the sculptor and author Máret Ánne Sara, was invited to the Venice Biennale to design the Nordic Pavilion as a specifically Sámi Pavilion.

4. Established in 2008, the TRC’s primary mandate was to investigate and document the manifold crimes and long-term traumas endured by the children of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, who were forced to attend the residential schools that had been instigated by the federal government in 1879 and were administered by the Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian, and United Churches until 1996. The final report of the TRC also included a list of ninety-four concrete ‘Calls to Action’ with recommendations to increase the rights of Indigenous peoples, promote their welfare, and implement compensations for the colonial crimes committed. All documents, recordings, and reports pertaining to the TRC are housed by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba: https://nctr.ca/map.php (accessed January 16, 2023).

5. Giron Sámi Teáhter, https://www.samiteahter.org/en/ (accessed July 9, 2022).

6. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2012), 119.

7. Harald Gaski, ‘Indigenism and Cosmopolitanism: A Pan-Sami View of the Indigenous Perspective in Sami Culture and Research’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 9, no. 2 (2013): 113–24 (114–15); original emphases.

8. Ranjan Datta, ‘Decolonizing both Researcher and Research and its Effectiveness in Indigenous Research’, Research Ethics 14, no. 2 (2018): 1–24 (2).

9. Ibid., 3.

10. See for example: Jesse Rae Archibald-Barber, Kathleen Irwin, and Moira J. Day, eds., Performing Turtle Island: Indigenous Theatre on the World Stage (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2019); Yvette Nolan, Medicine Shows: Indigenous Performance Culture (Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2015); Yvette Nolan and Ric Knowles, eds., Performing Indigeneity (Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2016).

11. Two influential scholarly volumes on Swedish theatre history ignore the topic entirely: Tomas Forser, ed., Ny svensk teaterhistoria (3 vols) (Hedemora: Gidlunds, 2007); Lena Hammergren, Karin Helander, Tiina Rosenberg, and Willmar Sauter, eds., Teater i Sverige (Hedemora: Gidlunds, 2004).

12. Rauna Johanna Kuokkanen, Reshaping the University: Responsibility, Indigenous Epistemes, and the Logic of the Gift (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007).

13. Ibid., 2-3.

14. Ibid., 49-73.

15. Ibid., 2.

16. Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 175–76.

17. Ibid., 125.

18. Gaski, ‘Indigenism and Cosmopolitanism’, 123; see also: Harald Gaski, ‘Indigenous Aesthetics: Add Context to Context’, in Sámi Art and Aesthetics: Contemporary Perspectives, eds. Svein Aamold, Elin Kristine Haugdal, and Ulla Angkær Jørgensen (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2017), 179-93; Pirjo Kristiina Virtanen, Pigga Keskitalo, and Torjer Olsen, eds., Indigenous Research Methodologies in Sámi and Global Contexts (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

19. This is not meant to suggest that TRC’s in other countries, such as South Africa, would not have had an effect on the performing arts. See for example: Geoffrey Davis, ‘Addressing the Silences of the Past: Truth and Reconciliation in Post-Apartheid Theatre’, South African Theatre Journal 13, no. 1 (1999): 59–72.

20. Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 5.

21. Kuokkanen, Reshaping the University, 52.

22. All quotations from CO2lonialNATION are based on a video recording of performances from Kiruna/Giron (February 6–7, 2017) and Helsinki (April 28, 2017) which Giron Sámi Teáhter graciously shared with me. All translations are my own.

23. David Gaertner, ‘“Aboriginal Principles of Witnessing” and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’, in Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, eds. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 135–55 (142).

24. Sam McKegney, ‘“pain, pleasure, shame. Shame.”: Masculine Embodiment, Kinship, and Indigenous Reterritorialization’, in Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, eds. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 193–214 (196).

25. David Garneau, ‘Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation’, in Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, eds. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 21–41 (23).

26. Marie Enoksson, ‘Preparations before a truth commission on the violations of the Sami people by the Swedish State’, Sámediggi, 2021, https://www.sametinget.se/160524 (accessed January 19, 2022).

27. Rauna Kuokkanen, ‘Borders Crossings, Pathfinders and New Visions: The Role of Sámi Literature in Contemporary Society’, Nordlit 15 (2004): 91-103; Elin Anna Labba, Herrarna satte oss hit: Om tvångsförflyttningarna i Sverige (Stockholm: Norstedts, 2020); Patrik Lantto, ‘The Consequences of State Intervention: Forced Relocations and Sámi Rights in Sweden, 1919-2012’, The Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 8, no. 2 (2014): 53-73; Veli-Pekka Lehtola, ‘“The Soul Should Have Been Brought along”: The Settlement of Skolt Sami to Inari in 1945–1949’, Journal of Northern Studies 12, no. 1 (2018): 53–72; Lynette McGuire, ‘The Fragmentation of Sápmi: A Nordic Model of Settler Colonialism’, Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal/Études scandinaves au Canada 29 (2022): 1–12.

28. Gabriel Kuhn, Liberating Sápmi: Indigenous Resistance in Europe’s Far North (Oakland: PM Press, 2020), 20-63; Roger Kvist, ‘The Racist Legacy in Modern Swedish Saami Policy’, Canadian Journal of Native Studies 14, no. 2 (1994): 203-20; Veli-Pekka Lehtola, The Sámi People: Traditions in Transition (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2004); Teemu Ryymin, ‘The Rise and Development of Nationalism in Northern Norway’, in The North Calotte: Perspectives on the Histories and Cultures of Northernmost Europe, eds. Maria Lähteenmäki and Päivi Maria Pihlaja (Inari: Puntsi, 2005), 54–66.

29. Patrik Lantto, Lappväsendet: tillämpningen av svensk samepolitik 1885-1971 (Umeå: Umeå University, 2012); Ulf Mörkenstam, Om ‘Lapparnes privilegier’: Föreställningar om samiskhet i svensk samepolitik 1883-1997, PhD diss. Stockholm University, 1999.

30. Government Offices of Sweden, ‘Sanningskommission för det samiska folket’, November 3, 2021, https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2021/11/sanningskommission-for-det-samiska-folket/ (accessed November 10, 2021). All translations from Swedish are mine, unless otherwise noted.

31. See for example: Robinson and Martin, eds. Arts of Engagement; Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonization Is not a Metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

32. Åsa Simma, interview with the author, April 12, 2021.

33. Yoik (Northern Sámi: luohti; Southern Sámi: vuelie) is the traditional Sámi song. According to Gaski, the yoik is central to ‘Sami consciousness because of its traditional role both as a mark of identity and, in the old religion, as the music of the shaman, noaidi, in Sami’. Harald Gaski, ‘Song, Poetry and Images in Writing: Sami Literature’, Nordlit 27 (2011): 33-54 (33).

34. The Minority Language Act from 2000, revised in 2010 (Prop. 1998/99:143 and § 2009:724) identifies Sámi as an official minority language in Sweden, along with Finnish, Yiddish, Meänkieli, and Romani Chib. In total, there exist nine different Sámi languages, out of which five are spoken in the Swedish part of Sápmi: Northern Sámi, Southern Sámi, Lule Sámi, Pite Sámi, and Ume Sámi.

35. Simma, interview with the author.

36. The final manuscript was put together by Pauliina Feodoroff, Niillas Holmberg, Simon Issát Marainen, Elina Israelsson, Sarakka Gaup, and Mio Negga.

37. Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 145.

38. Ibid., 36.

39. I am indebted to a Norwegian translation and transcription by Solgunn Solli, ‘Kraften i kunst - CO2lonialNation - Giron Sámi Teáhter’, Solgun sitt, September 7, 2017, http://solgunnsin.blogspot.com/2017/09/kraften-i-kunst-co2lonialnation-giron.html (accessed September 20, 2020). For Ailo Gaup’s own account of events, see: Ailo Gaup, ‘Min mor på vidda’, in I min mors hus: Tretten sønner forteller, ed. Knut Johansen (Oslo: Pax, 1989), 29–47.

40. Veli-Pekka Lehtola, ‘Staging Sami Identities: The Roles of Modern Sami Theatre in a Multicultural Context – The Case of Beaivvás Teáhter’, in L’Image du Sápmi: Études comparées, ed. Kajsa Andersson (Örebro: Örebro University, 2009), 436–58.

41. Gaski acknowledges the significant dialectal and linguistic differences between these languages, but also warns of the risk of overemphasizing cultural differences or divisions among the Sámi. Gaski, ‘Indigenism and Cosmopolitanism’, 121.

42. Feodoroff quoted in Helene Alm, ‘Koloniala skador utforskas av samiska teatern’, Sveriges Radio, February 2, 2017, https://sverigesradio.se/avsnitt/857766 (accessed July 4, 2020).

43. Lehtola, ‘Staging Sami Identities’, 454.

44. Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström, eds, De historiska relationerna mellan Svenska kyrkan och samerna: En vetenskaplig antologi (Skellefteå: Artos & Norma, 2016), www.svenskakyrkan.se/samiska/vitboken (accessed April 20, 2022).

45. Gunlög Fur, ‘Att sona det förflutna’, in De historiska relationerna mellan Svenska kyrkan och samerna, eds. Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström (Skellefteå: Artos & Norma, 2016), 153–90.

46. Patrik Lantto, ‘Från folkspillra till erkänt urfolk: Svensk samepolitik från 1800-tal till idag’, in Sápmi i ord och bild I, ed. Kajsa Andersson (Stockholm: On Line Förlag, 2015), 58-83; Erik-Oscar Oscarsson, ‘Rastänkande och särskiljande av samer’, in De historiska relationerna mellan Svenska kyrkan och samerna, eds. Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström (Skellefteå: Artos & Norma, 2016), 943–60.

47. Lindmark and Sundström, De historiska relationerna mellan; Kaisa Huuva and Ellacarin Blind, eds, ‘När jag var åtta år lämnade jag mitt hem och jag har ännu inte kommit tillbaka’: Minnesbilder från samernas skoltid (Stockholm: Verbum, 2016), https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/samiska/nomadskoleboken (accessed April 30, 2022).

48. Maja Hagerman, Käraste Herman: rasbiologen Herman Lundborgs gåta (Stockholm: Norstedt, 2015).

49. Ragnhild Freng Dale, ‘En sanningskommisjon på scenen’, Scenekunst, May 11, 2017, http://www.scenekunst.no/sak/en-sanningskommisjon-pa-scenen/ (accessed September 20, 2020).

50. Jaye T. Darby, Courtney Elkin Mohler, and Christy Stanlake, Critical Companion to Native American and First Nations Theatre and Performance: Indigenous Spaces (London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2020), 8 and 12.

51. Moa Sandström, Dekoloniseringskonst: Artivism i 2010-talets Sápmi, PhD diss. Umeå University, 2020, 65.

52. Anne Heith, ‘Enacting Colonised Space: Katarina Pirak Sikku and Anders Sunna’, Nordisk Museologi 2 (2015): 69-83 (78).

53. Ibid., 80.

54. Sunna quoted in Sandström, Dekolonise-ringskonst, 91.

55. Ekaterina Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, December 2019, 1-16 (3-6), https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/sipribp1912_geopolitics_in_the_arctic.pdf (accessed June 16, 2020).

56. Moa Sandström, ‘DeCo2onising Artivism’, in Samisk kamp: Kulturförmedling och rättviserörelse, eds. Marianne Liliequist and Coppélie Cocq (Umeå: h:ström, 2017), 62–115.

57. ‘Climate justice in Sápmi: Sarakka Gaup & Mio Negga, Actress/music producer & actor’, 350.org, July 8, 2017, https://350.org/saami-climate-justice/ (accessed May 24, 2020).

58. Åsa Simma, interview with the author, May 14, 2021.

59. Kuokkanen, Reshaping the University, 32.

60. Jill Dolan, Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005).

61. Lehtola, ‘“The Soul Should Have Been Brought along”’, 55–57.

62. Nolan, Medicine Shows, 3. See also: Inga Juuso, ‘Yoiking Acts as Medicine for Me’, in No Beginning, No End: The Sami Speak Up, eds. Elina Helander and Kaarina Kailo (Edmonton: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, 1998), 132–46.

63. Gaup quoted in ‘Climate Justice in Sápmi’.

64. Feodoroff quoted in Elin Swedenmark, ‘Koloniserade samers vittnesmål blir teater’, Sydsvenskan, February 3, 2017, https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2017-02-03/koloniserade-samers-vittnesmal-blir-teater (accessed September 20, 2020).

65. Simma quoted in Alm, ‘Koloniala skador utforskas av samiska teatern’. The quote was used as the epigraph to Tomson Highway’s Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, a seminal play in Indigenous Canadian theatre history, first performed in 1989 in Toronto.

66. There are many regional variations of the gákti, some of which have elaborate embellishments, while others are more subdued. The different shapes, colours, and buttons also communicate information about gender, social, or marital status. Lehtola, The Sámi People, 12-14; Tom G. Svensson, ‘Clothing in the Arctic: A Means of Protection, a Statement of Identity’, Arctic 45, no. 1 (1992): 62–73.

67. Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

68. There exist many regional variations of Sámi regalia and, as the duodji artist Anna-Stina Svakko explained to me, Israelsson’s hat, belt, and gákti were meant to pay tribute to her father who originated from the Gällivare/Jiellevárri area. Anna-Stina Svakko, interview with the author, July 5, 2021.

69. Gunvor Guttorm, ‘The Power of Natural Materials and Environments in Contemporary Duodji’, in Sámi Art and Aesthetics: Contemporary Perspectives, eds. Svein Aamold, Elin Kristine Haugdal, and Ulla Angkær Jørgensen (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2017), 163–177 (165).

70. In a highly unusual move, each of the actors got to choose the designer with whom they wanted to work.

71. Svakko, interview with the author.

72. Ibid.

73. Ibid.

74. 169, public post, Facebook, August 10, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/pg/ily169/posts/?ref=page_internal (accessed June 2, 2020). ‘Sogiid siste’ was composed and produced by Mio Negga. Niillas Holmberg wrote the lyrics and the recorded yoik was performed by the three actors and Niko Valkeapää.

75. Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed, trans. Charles A. McBride (New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1993), 155.