ABSTRACT

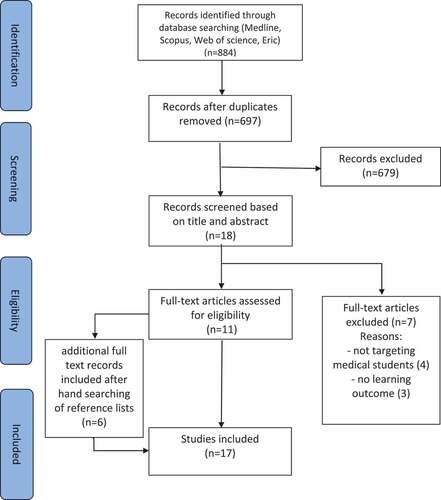

Practicing Multiple-choice questions is a popular learning method among medical students. While MCQs are commonly used in exams, creating them might provide another opportunity for students to boost their learning. Yet, the effectiveness of student-generated multiple-choice questions in medical education has been questioned. This study aims to verify the effects of student-generated MCQs on medical learning either in terms of students’ perceptions or their performance and behavior, as well as define the circumstances that would make this activity more useful to the students. Articles were identified by searching four databases MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and ERIC, as well as scanning references. The titles and abstracts were selected based on a pre-established eligibility criterion, and the methodological quality of articles included was assessed using the MERSQI scoring system. Eight hundred and eighty-four papers were identified. Eleven papers were retained after abstract and title screening, and 6 articles were recovered from cross-referencing, making it 17 articles in the end. The mean MERSQI score was 10.42. Most studies showed a positive impact of developing MCQs on medical students’ learning in terms of both perception and performance. Few articles in the literature examined the influence of student-generated MCQs on medical students learning. Amid some concerns about time and needed effort, writing multiple-choice questions as a learning method appears to be a useful process for improving medical students’ learning.

Introduction

Active learning, where students are motivated to construct their understanding of things, and make connections between the information they grasp is proven to be more effective than passively absorb mere facts [Citation1]. However, medical students, are still largely exposed to passive learning methods, such as lectures, with no active involvement in the learning process. In order to assimilate the vast amount of information they are supposed to learn, students adopt a variety of strategies, which are mostly oriented by the assessment methods used in examinations [Citation2].

Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) represent the most common assessment tool in medical education worldwide [Citation3]. Therefore, it is expected that students would favor practicing MCQs, either from old exams or commercial question banks, over other learning methods to get ready for their assessments [Citation4]. Although this approach might seem practical for students as it strengthens their knowledge and gives them a prior exam experience, it might incite surface learning instead of constructing more elaborate learning skills, such as application and analysis [Citation5].

Involving students in creating MCQs appears to be a potential learning strategy that combines students’ pragmatic approach and actual active learning. Developing good questions, in general, implies a deep understanding and a firm knowledge of the material that is evaluated [Citation6]. Writing a good MCQ requires, in addition to a meticulously drafted stem, the ability to suggest erroneous but possible distractors [Citation7,Citation8]. It has been suggested that creating distractors may reveal misconceptions and mistakes and underlines when students have a defective understanding of the course material [Citation6,Citation9]. In other words, creating a well-constructed MCQ requires more cognitive abilities than answering one [Citation10]. Several studies have shown that the process of producing questions is an efficient way to motivate students and enhance their performance, and linked MCQs generation to improve test performance [Citation11–15]. Therefore, generating MCQs might develop desirable problem-solving skills and involve students in an activity that is immediately and clearly relevant to their final examinations.

In contrast, other studies indicated there was no considerable impact of this time-consuming MCQs development activity on students’ learning [Citation10] or that question-generation might benefit only some categories of students [Citation16].

Because of the conflicting conclusions about this approach in different studies, we conducted a systematic review to define and document evidence of the effect of writing MCQs activity on students learning, and understand how and under what circumstances it could benefit medical students, as to our knowledge, there is no prior systematic review addressing the effect of student-generated multiple-choice questions on medical students’ learning.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) [Citation17]. Ethical approval was not required because this is a systematic review of previously published research, and does not include any individual participant information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

summarizes the publications’ inclusion and exclusion criteria. The target population was undergraduate and graduate medical students. The intervention was generating MCQs of all types. The learning outcomes of the intervention had to be reported using validated or non-validated instruments. We excluded studies involving students from other health-related domains, those in which the intervention was writing questions other than MCQs, and also completely descriptive studies without an evaluation section of the learning outcome. Comparison to other educational interventions was not regarded as an exclusive criterion because much educational research in the literature is case-based.

Table 1. Inclusion & exclusion criteria

Search strategy

On May 16th, 2020, two reviewers separately conducted a systematic search on 4 databases, ‘Medline’ (via PubMed), ‘Scopus’, ‘Web of Science’ and ‘Eric’ using keywords as (Medical students, Multiple-choice questions, Learning, Creating) and their possible synonyms and abbreviations which were all combined by Boolean logic terms (AND, OR, NOT) with convenient search syntax for each database (Appendix 1). Then, all the references generated from the search were imported to a bibliographic tool (Zotero®) [Citation18] used for the management of references. The reviewers also checked manually the references list of selected publications for more relevant papers. Sections as ‘Similar Articles’ below articles (e.g., PubMed) were also checked for possible additional articles. No restrictions regarding the publication date, language, or origin country were applied.

Study selection

The selection process was directed by two reviewers independently. It started with the screening of all papers generated with the databases search, followed by removal of all duplicates. All papers whose titles had a potential relation to the research subject were kept for an abstract screening, while those with obviously irrelevant titles were eliminated. The reviewers then conducted an abstract screening; all selected studies were retrieved for a final full-text screening. Any disagreement among the reviewers concerning papers inclusion was settled through consensus or arbitrated by a third reviewer if necessary.

Data collection

Two reviewers worked separately to create a provisional data extraction sheet, using a small sample made of 4 articles. Then, they met to finalize the coding sheet by adding, editing, and deleting sections, leading to a final template, implemented using Microsoft Excel® to ensure the consistency of collected data. Each reviewer then, extracted data independently using the created framework. Finally, the two reviewers compared their work to ensure the accuracy of the collected data. The items listed in the sheet were article authorship and year of publication, country, study design, participants, subject, intervention and co-interventions, MCQ type and quality, assessment instruments, and findings.

Assessment of study methodological quality

There are few scales to assess the methodological rigor and trustworthiness of quantitative research in medical education, to mention the Best Medical Education Evaluation global scale [Citation19], Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [Citation20], and Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [Citation21]. We chose the latter to assess quantitative studies because it provides a detailed list of items with specified definition, solid validity evidence, and its scores are correlated with the citation rate in the succeeding 3 years of publication, and with the journal impact factor [Citation22,Citation23]. MERSQI evaluates study quality based on 10 items: study design, number of institutions studied, response rate, data type, internal structure, content validity, relationship to other variables, appropriateness of data analysis, the complexity of analysis, and the learning outcome. The 10 items are organized into six domains, each with a maximum score of 3 and a minimum score of 1, not reported items are not scored, resulting in a maximum MERSQI score of 18 [Citation21].

Each article was assessed independently by two reviewers; any disagreement between the reviewers about MERSQI scoring was resolved by consensus and arbitrated by a third reviewer if necessary. If a study reported more than one outcome, the one with the highest score was taken into account.

Results

Study design and population characteristics

Eight hundred eighty-four papers were identified after the initial databases search, of which 18 papers were retained after title and abstract screening (see ). Seven of them didn’t fit in the inclusion criteria for reasons as the absence of learning outcome or the targeted population being other than medical students. Finally, only 11 articles were retained, added to another 6 articles retrieved by cross-referencing. For the 17 articles included, the two reviewers agreed about 16 articles, and only one paper was discussed and decided to be included.

The 17 included papers reported 18 studies, as one paper included two distinct studies. Thirteen out of the eighteen studies were single group studies representing the most used study design (See ). Eleven of these single group studies were cross-sectional while two were pre-post-test studies. The second most frequent study design encountered was cohorts, which were adopted in three studies. The remaining two were randomized controlled trials (RCT). The studies have been conducted between 1996 and 2019 with 13 studies (79%) from 2012 to 2019.

Table 2. Demographics, interventions, and outcome of the included studies

Regarding research methodology, 10 were quantitative studies, four were qualitative and four studies had mixed methods with a quantitative part and a qualitative one (students’ feedback).

Altogether, 2122 students participated in the 17 included papers. All participants were undergraduate medical students enrolled in the first five years of medical school. The preclinical stage was the most represented, with 13 out of the 17 papers including students enrolled in the first two years of medical studies.

Most studies used more than one data source, surveys were present as a main or a parallel instrument to collect data in eight studies. Other data sources were qualitative feedback (n = 8), qualitative feedback turned to quantitative data (n = 1), pre-post-test (n = 4), and post-test (n = 5).

Quality assessment

Overall, the MERSQI scores used to evaluate the quality of the 14 quantitative studies were relatively above average which is 10.7, with a mean MERSQI score of 10.75, ranging from 7 to 14 (see details of MERSQI score for each study in ). Studies lost points on MERSQI for using single group design, limiting participants to a single institution, the lack of validity evidence for instrument (only two studies used valid instrument) in addition to measuring the learning outcome only in terms of students’ satisfaction and perceptions.

Table 3. Methodological quality of included studies according to MERSQI

Findings

The evaluation of the educational effect of MCQs writing was carried out using objective measures in 9 out of the 18 studies included, based on pre-post-tests or post-tests only. Subjective assessments as surveys and qualitative feedbacks were present as second data sources in 7 of these 9 studies, whereas they were the main measures in the remaining nine studies. Hence, 16 studies assessed the learning outcome in terms of students’ satisfaction and perceptions towards the activity representing the first learning level of the Kirkpatrick model which is a four-level model for analyzing and evaluating the results of training and educational programs [Citation24]. Out of these 16 studies, 3 studies wherein students expressed dissatisfaction with the process and found it disadvantageous compared to other learning methods, whereas 4 studies found mixed results as students admitted the process value though they doubted its efficiency. On the other hand, nine studies provided favorable results of the exercise which was considered of immense importance and helped students consolidate their understanding and knowledge, although students showed reservations about the time expense of the exercise in three studies.

Regarding the nine studies that used objective measures to assess students’ skills and knowledge, which represent the second level of the Kirkpatrick model, six studies reported a significant improvement in students’ grades doing this activity, whereas two studies showed no noticeable difference in grades, and one showed a slight drop in grades.

One study suggested that students performed better when writing MCQs on certain modules compared to others. Two studies found the activity beneficial to all students’ categories while another two suggested the process was more beneficial for low performers.

Four Studies also found that writing and peer review combinations were more beneficial than solely writing MCQs. On the other hand, two studies revealed that peer-reviewing groups didn’t promote learning and one study found mixed results.

Concerning the quality of the generated multiple-choice questions, most studies reported that the MCQs were of good or even high quality when compared to faculty-written MCQs, except for two studies where students created MCQs of poor quality. However, only a few studies (n = 2) reported whether students wrote MCQs that tested higher-order skills such as application and analysis or simply tested recalling facts and concepts.

The majority of interventions required students to write single best answer MCQs (n = 6), three of which were vignettes MCQs. Assertion reason MCQs were present in two studies, and in one study, students were required to write only the stem of the MCQ, while in another study, students were asked to write distractors and the answer, while the rest of studies did not report the MCQs Type.

Discussion

Data and methodology

This paper methodically reviewed 17 articles investigating the impact of writing multiple-choice questions by medical students on their learning. Several studies pointedly examined the effect of the activity inquired on the learning process, whereas it only represented a small section of the article, which was used for the review. This is due to the fact that many papers focused on other concepts like assessing the quality of students generated MCQs or the efficiency of online question platforms, reflecting the scarce research on the impact of a promising learning strategy (creating MCQs) in medical education.

The mean MERSQI score of quantitative studies was 10.75 which is slightly above the level suggestive of a solid methodology set to 10.7 or higher [Citation21]. This indicates an acceptable methodology used by most of the studies included. Yet, only two studies [Citation30,Citation31] used a valid instrument in terms of internal structure, content, and relation to other variables, making the lack of the instrument validity, in addition to the use of a single institution and single group design, as the main identified methodological issues.

Furthermore, the studies assessing the outcome in terms of knowledge and skills scored higher than the ones appraising the learning outcome regarding perception and satisfaction. Hence, we recommend that future research should provide more details on the validity parameters of the assessment instruments, and also focus on higher learning outcome levels; precisely skills and knowledge as they are typically more linked with the nature of the studied activity.

Relation with existing literature

Apart from medical education, the impact of students’ generated questions has been a relevant research question in a variety of educational environments. Fu-Yun & Chun-Ping demonstrated through hundreds of papers that student-generated questions promoted learning and led to personal growth [Citation32]. For example, in Ecology, students who were asked to construct multiple-choice questions significantly improved their grades [Citation33]. Also, in an undergraduate taxation module, students who were asked to create multiple-choice questions significantly improved their academic achievement [Citation34].

A previous review explored the impact of student-generated questions on learning and concluded that the process of constructing questions raised students’ abilities of recall and promoted understanding of essential subjects as well as problem-solving skills [Citation35]. Yet, this review gave a general scope on the activity of generating questions, taking into consideration all questions formats. Thus, its conclusions will not necessarily concord with our review because medical students define a special students’ profile [Citation36], along with the particularity of multiple-choice questions. As far as we know, this is the first systematic review made to appraise the pedagogical interest of the described process of creating MCQs in medical education.

Students’ satisfaction and perceptions

Students’ viewpoints and attitudes toward the MCQ generation process were evaluated in multiple studies, and the results were generally encouraging, despite a few exceptions where students expressed negative impressions of the process and favored other learning methods over it [Citation4,Citation10]. The most pronouncing remarks were essentially on the time-consumption limiting the process efficiency. This was mainly related to the complexity of the task given to students who were required to write MCQs in addition to other demanding assignments.

Since the most preferred learning method for students is learning by doing, they presumably benefit more when instructions are conveyed in shorter segments, and when introduced in an engaging format [Citation37]. Thus, some researchers tried more flexible strategies as providing the MCQs distractors and asking students for the stem or better providing the stem and requesting distractors as these were considered to be the most challenging parts of the process [Citation38].

Some authors used online platforms to create and share questions making the MCQs generation smoother. Another approach to motivate students was including some generated MCQs in examinations, to boost students’ confidence and enhance their reflective learning [Citation39]. These measures, supposed to facilitate the task, were perceived positively by students.

Students’ performance

Regarding students’ performance, MCQs-generation exercise broadly improved students’ grades. However, not all studies have reported positive results. Some noted no significant effect of writing MCQs on students’ exam scores [Citation10,Citation31]. This was explained by the small number of participants, and the lack of instructors’ supervision. Moreover, students were tested on a broader material than the one they were instructed to write MCQs on, meaning that students might have effectively benefited from the process if they created a larger number of MCQs covering a wider range of material or if the process was aligned with the whole curriculum content. Besides, some studies reported that low performers benefited more from the process of writing MCQs, concordantly with the findings of other studies which indicate that activities promoting active learning advantage lower-performing students more than higher-performing ones [Citation40,Citation41]. Another suggested explanation was the fact that low achievers tried to memorize student-generated MCQs when these made part of their examinations, reversely favoring surface learning instead of the deep learning anticipated from this activity. This created a dilemma between enticing students to participate in this activity and the disadvantage of memorizing MCQs. Therefore, including modified student-generated MCQs after instructors’ input, rather than the original student-generated version in the examinations’ material, might be a reasonable option along with awarding extra points when students are more involved in the process of writing MCQs.

Determinant factors

Students’ performance tends to be related to their ability to generate high-quality questions. As suggested in preceding reviews [Citation35,Citation42], assisting students in constructing questions may enhance the quality of these students’ generated questions, encourage learning, and improve students’ achievement. Also, guiding students to write MCQs makes it possible to test higher-order skills as application and analysis besides recall and comprehension. Accordingly, in several studies, students were provided with instructions on how to write high-quality multiple-choice questions, resulting in high-quality student-generated MCQs [Citation10,Citation43–45]. Even so, such guidelines must take into account not making students’ job more challenging to maintain the process as pleasant.

Several papers discussed various factors that influence the learning outcome of the activity, as working in groups and peer checking MCQs, which were found to be associated with higher performance [Citation30,Citation38,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46–49]. These factors were also viewed favorably by students because of their potential to broaden and deepen one’s knowledge, as well as to notice any misunderstandings or problems, according to many studies, that highlighted a variety of beneficial outcomes of peer learning approaches in the education community [Citation42,Citation50,Citation51]. However, in other studies, students preferred to work alone and demanded that time devoted to peer-reviewing MCQs be reduced [Citation38,Citation45]. This was mostly due to students’ lack of trust in the quality of MCQs created by peers; thus, evaluating students’ MCQs by instructors was also a component of an effective intervention.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation of the present review is the scarcity of studies in the literature. We used a narrowed inclusion criterion leading to the omission of articles published in non-indexed journals and papers from other health-care fields that may have been instructive. However, the choice of limiting the review scope to medical students only was motivated by the specificity of the medical education curricula and teaching methods compared to other health professions categories in most settings. Another limitation is the weak methodology of a non-negligible portion of studies included in this review which makes drawing and generalizing conclusions a delicate exercise. On the other hand, this is the first review to summarize data on the learning benefits of creating MCQs in medical education and to shed light on this interesting learning tool.

Conclusion

Writing multiple-choice questions as a learning method might be a valuable process to enhance medical students learning despite doubts raised on its real efficiency and pitfalls in terms of time and effort.

There is presently a dearth of research that examines the influence of student-generated MCQs on learning. Future research on the subject must use a strong study design, valid instruments, simple and flexible interventions, as well as measure learning based on performance and behavior, and explore the effect of the process on different students’ categories (eg. performance, gender, level), in order to reach the most appropriate circumstances for the activity to get the best out of it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lim J, Ko H, Yang JW, et al. Active learning through discussion: ICAP framework for education in health professions. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Dec;19(1):477.

- Hilliard RI. How do medical students learn: medical student learning styles and factors that affect these learning styles. Teach Learn Med. 1995 Jan;7(4):201–13.

- Al-Wardy NM. Assessment methods in undergraduate medical education. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2010 Aug;10(2):203–209.

- Wynter L, Burgess A, Kalman E, et al. Medical students: what educational resources are they using? BMC Med Educ. 2019 Jan;19(1):36.

- Veloski JJ, Rabinowitz HK, Robeson MR, et al. Patients don’t present with five choices: an alternative to multiple-choice tests in assessing physicians’ competence. Acad Med. 1999 May;74(5):539–546.

- Galloway KW, Burns S. Doing it for themselves: students creating a high quality peer-learning environment. Chem Educ Res Pract. Jan 2015;16(1):82–92.

- Collins J. Writing multiple-choice questions for continuing medical education activities and self-assessment modules. RadioGraphics. 2006 Mar;26(2):543–551.

- Coughlin PA, Featherstone CR. How to write a high quality multiple choice question (MCQ): a guide for clinicians. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017 Nov;54(5):654–658.

- Olde Bekkink M, Donders ARTR, Kooloos JG, et al. Uncovering students’ misconceptions by assessment of their written questions. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Aug;16(1):221.

- Palmer E, Devitt P. Constructing multiple choice questions as a method for learning. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2006 Sep;35(9):604–608.

- Shakurnia A, Aslami M, Bijanzadeh M. The effect of question generation activity on students’ learning and perception. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2018 Apr;6(2):70–77.

- Rhind SM, Pettigrew GW. Peer generation of multiple-choice questions: student engagement and experiences. J Vet Med Educ. 2012;39(4):375–379.

- Foos PW, Mora JJ, Tkacz S. Student study techniques and the generation effect. J Educ Psychol. 1994;86(4):567–576.

- Denny P, Hamer J, Luxton-Reilly A, et al., “PeerWise: students sharing their multiple choice questions,” in Proceedings of the Fourth international Workshop on Computing Education Research, New York, NY, USA, Sep. 2008, pp. 51–58. doi: 10.1145/1404520.1404526.

- Bottomley S, Denny P. A participatory learning approach to biochemistry using student authored and evaluated multiple-choice questions. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2011 Oct;39(5):352–361.

- Olde Bekkink M, Donders ARTR, Kooloos JG, et al. Challenging students to formulate written questions: a randomized controlled trial to assess learning effects. BMC Med Educ. 2015 Mar;15(1):56.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul;6(7):e1000097.

- Ahmed KKM, Al Dhubaib BE. Zotero: a bibliographic assistant to researcher. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2(4):303–305.

- Hammick M, Dornan T, Steinert Y. Conducting a best evidence systematic review. Part 1: from idea to data coding. BEME Guide No. 13. Med Teach. 2010 Jan;32(1):3–15.

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al., “The Ottawa hospital research institute,” Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. [Online]. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed: 2021 Jun 10.

- Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, et al. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Jul;23(7):903–907.

- Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the medical education research study quality instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale-education. Acad Med. 2015 Aug;90(8):1067–1076.

- Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, et al. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007 Sep;298(9):1002–1009.

- Kirkpatrick D, and Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2006.

- Shah MP, Lin BR, Lee M, et al. Student-written multiple-choice questions—a practical and educational approach. Med.Sci.Educ 2019 Mar;29(1):41–43.

- Herrero JI, Lucena F, Quiroga J. Randomized study showing the benefit of medical study writing multiple choice questions on their learning. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Jan;19(1):42.

- Rajendiren S, Dhiman P, Rajendiren S, et al. Making concepts of medical biochemistry by formulating distractors of multiple choice questions: growing mighty oaks from small acorns. J Contem Med Edu. 2014 Jun;2(2):123–127.

- McLeod PJ, Snell L. Student-generated MCQs. Med Teach. 1996 Jan;18(1):23–25.

- Walsh JL, Harris BHL, Denny P, et al. Formative student-authored question bank: perceptions, question quality and association with summative performance. Postgrad Med J. 2018 Feb;94(1108):97–103.

- Grainger R, Dai W, Osborne E, et al. Medical students create multiple-choice questions for learning in pathology education: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2018 Aug;18(1):201.

- Rick Stone M, Kinney M, Chatterton C, et al. A crowdsourced system for creating practice questions in a clinical presentation medical curriculum. Med.Sci.Educ 2017 Dec;27(4):685–692.

- Fu-Yun Y, Chun-Ping W. Student question-generation: the learning processes involved and their relationships with students’ perceived value. Jiaoyu Kexue Yanjiu Qikan. 2012 Dec;57:135–162.

- Teplitski M, Irani T, Krediet CJ, et al. Student-generated pre-exam questions is an effective tool for participatory learning: a case study from ecology of waterborne pathogens course. J Food Sci Educ. 2018;17(3):76–84.

- Doyle E, Buckley P. The impact of co-creation: an analysis of the effectiveness of student authored multiple choice questions on achievement of learning outcomes. Inter Learning Environ. Jun 2020:1–10.

- Song D. Student-generated questioning and quality questions: a literature review. Res J Educ Stud Rev. 2016;2:58–70.

- Buja LM. Medical education today: all that glitters is not gold. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Apr;19(1):110.

- Twenge JM. Generational changes and their impact in the classroom: teaching generation me. Med Educ. 2009 May;43(5):398–405.

- Kurtz JB, Lourie MA, Holman EE, et al. Creating assessments as an active learning strategy: what are students’ perceptions? A mixed methods study. Med Educ Online. 2019 Dec;24(1):1630239.

- Baerheim A, Meland E. Medical students proposing questions for their own written final examination: evaluation of an educational project. Med Educ. 2003 Aug;37(8):734–738.

- Hassumani D, Cancellieri S, Boudakov I, et al. Quiz discuss compare: using audience response devices to actively engage students. Med Sci Educator. 2015;3(25):299–302.

- Koles P, Nelson S, Stolfi A, et al. Active learning in a Year 2 pathology curriculum. Med Educ. 2005 Oct;39(10):1045–1055.

- Rosenshine B, Meister C, Chapman S. Teaching students to generate questions: a review of the intervention studies. Rev Educ Res. 1996 Jun;66(2):181–221.

- Chamberlain S, Freeman A, Oldham J, et al. Innovative learning: employing medical students to write formative assessments. Med Teach. 2006 Nov;28(7):656–659.

- Walsh J, Harris B, Tayyaba S, et al. Student-written single-best answer questions predict performance in finals. Clin Teach. 2016 Oct;13(5):352–356.

- Jobs A, Twesten C, Göbel A, et al. Question-writing as a learning tool for students – outcomes from curricular exams. BMC Med Educ. 2013 Jun;13(1):89.

- Gooi ACC, Sommerfeld CS. Medical school 2.0: how we developed a student-generated question bank using small group learning. Med Teach. 2015;37(10):892–896.

- Harris BHL, Walsh JL, Tayyaba S, et al. A novel student-led approach to multiple-choice question generation and online database creation, with targeted clinician input. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):182–188.

- Bobby Z, Radhika MR, Nandeesha H, et al. Formulation of multiple choice questions as a revision exercise at the end of a teaching module in biochemistry. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2012 May;40(3):169–173.

- Papinczak T, Peterson R, Babri AS, et al. Using student-generated questions for student-centred assessment. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 2012 Jun;37(4):439–452.

- Dehghani MR, Amini M, Kojuri J, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of peer-learning method in nutrition students of Shiraz University of medical sciences. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2014 Apr;2(2):71–76.

- Goldsmith M, Stewart L, Ferguson L. Peer learning partnership: an innovative strategy to enhance skill acquisition in nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2006 Feb;26(2):123–130.

- Sircar SS, Tandon OP. Involving students in question writing: a unique feedback with fringe benefits. Am J Physiol. 1999 Dec;277(6 Pt 2):S84–91.

Appendix:

Search strategy

Medline:

Query: ((((Medical student) OR (Medical students)) AND (((Create) OR (Design)) OR (Generate))) AND ((((multiple-choice question) OR (Multiple-choice questions)) OR (MCQ)) OR (MCQs))) AND (Learning)

Results: 300

Scopus:

Query: ALL (medical PRE/0 students) AND ALL (multiple PRE/0 choice PRE/0 questions) AND ALL (learning) AND ALL (create OR generate OR design)

Results: 468

Web of science:

Query: (ALL = ‘Multiple Choice Questions’ OR ALL = ‘Multiple Choice Question’ OR ALL = MCQ OR ALL = MCQs) AND (ALL = ‘Medical Students’ OR ALL = ‘Medical Student’) AND (ALL = Learning OR ALL = Learn) AND (ALL = Create OR ALL = Generate OR ALL = Design)

Results: 109

ERIC:

Query: ‘Medical student’ AND ‘Multiple choice questions’ AND Learning AND (Create OR Generate OR Design)

Results: 7

Total = 884

After deleting double references: Number: 697