ABSTRACT

The present study focused on the differential effects of two German PD programs in the ECEC field. We examined whether PD programs are equally effective for all ECEC professionals or whether ECEC professionals benefit differently from these learning opportunities. An experimental pre-post-follow-up study was conducted in the field with random assignment of participants (N = 50) to one of two language-based PD programs. In addition, transfer-relevant factors (transfer motivation, self-efficacy, support from supervisors and colleagues) were taken into account to investigate whether possible differences in changes in the quality of instructional support were related to the transfer conditions. Using longitudinal multilevel analyses, we found that the PD program “Talking with Children”, which focuses on language promotion strategies, is equally effective for all participants. Even with minimal perceived support from colleagues and supervisors, strategies learned in the PD program can be implemented to improve the quality of instructional support. Our results suggest the importance of considering transfer conditions to better support ECEC professionals in implementing what they have learned in PD programs in the future.

Several studies have shown that high-quality instructional support (i.e., concept development, quality of feedback, language modeling) in early childhood settings is positively related to the development of children’s language skills (Howes et al., Citation2008; Mashburn et al., Citation2008). However, German and international studies have revealed that the average quality of emotional support and classroom organization is moderate to high, while the quality of instructional support is rather low to moderate (Eckhardt & Egert, Citation2017; Hu, et al., Citation2016; Peisner-Feinberg, et al., Citation2015). Given the importance of the quality of instructional support in ECEC settings, the question arises as to how it can be improved. Meta-analyses indicate a high potential for improving the quality of instructional support through professional development (hereafter: PD; Egert, et al., Citation2020). However, we still know relatively little about the differential effects of PD programs.

Professional development programs to improve instructional support quality

PD programs in early childhood education and care (ECEC) vary widely in terms of format, content, or delivery methods (Oberhuemer, Citation2012; Schachter, Citation2015). Variations in how PD is defined and operationalized make it difficult to compare different PD programs and thus determine which components are most effective (Buysse, Winton, & Rous, Citation2009). Efforts to define PD have been undertaken by National Professional Development Center on Inclusion (National Professional Development Center on Inclusion [NPDCI], Citation2008) to provide a framework for various trainings: “Professional development is facilitated teaching and learning experiences that are transactional and designed to support the acquisition of professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions as well as the application of this knowledge in practice” (p. 3). Key components of PD encompass the characteristics and context of learners and PD providers (“who”), the content (“what”), and the organization and facilitation of learning experiences (“how”) (Buysse, Winton, & Rous, Citation2009). By systematically examining these intersecting components, it may be possible to understand which PD program is most effective for whom, for what outcome, and under what conditions (Egert, Fukkink, & Eckhardt, Citation2018). This approach could help create a better match between supply (PD programs offered) and use. Research on transfer also addresses factors that are considered relevant to the application of learning to the work context. These factors include the characteristics of the trainees, the work environment, and the design of the training (Blume, Ford, Baldwin, & Huang, Citation2010; Holton, Bates, & Ruona, Citation2000; Kauffeld, Bates, Holton, & Mueller, Citation2008).

According to Egert’s Logit Model, it can be assumed that PD programs affect pedagogical quality through latent outcomes (awareness, orientation, knowledge, and competence) and manifest outcomes (job performance) among ECEC professionals (Egert & Kappauf, Citation2019). The effectiveness of PD programs in the ECEC field has been demonstrated in several meta-analyses (Egert, Dederer, & Fukkink, Citation2020; Lee & Sung, Citation2023; Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017; Werner, Linting, Vermeer, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2016). Despite the promising findings from meta-analyses, it is not possible to draw conclusions from the aggregate results about the differential effects on the quality of instructional support provided by ECEC professionals. Moreover, the study results included in the meta-analyses vary considerably, ranging from negative to positive, and the width of the confidence intervals for each outcome indicates that ECEC professionals benefit from PD programs to varying degrees (Egert, Fukkink, & Eckhardt, Citation2018; Fukkink & Lont, Citation2007).

Differential effects of PD programs on instructional support quality

Overall, there are only a few studies that address differential effects in PD programs (Lohse-Bossenz, Bahn, Busch, & Brandtner, Citation2022). Given this desideratum, it is warranted to focus on the question of for whom PD programs are effective, rather than on the content (“what”) and the training design (“how”). Offer-and-use-models suggest that individuals perceive, process, and use learning opportunities differently (Lipowsky, Citation2019). In particular, learners’ cognitive, motivational, and social prerequisites are considered important in this context, as learners participate in PD programs with different preexisting skills, knowledge, and dispositions (Lipowsky, Citation2019; Schachter, Citation2015).

Most (quasi-)experimental studies of PD programs in the ECEC field have used only teacher demographics to explain differential effects on outcomes. A study of the effects of on-site consultation found that teachers in the intervention condition, but not in the control condition, made larger gains in quality over time if they had more experience compared to less experience (Bryant et al., Citation2009). Similar findings were reported by Dickinson and Caswell (Citation2007), who found that more experienced teachers were more likely to adopt new (language and literacy) practices. In contrast, Early, Maxwell, Ponder, and Pan (Citation2017) reported stronger effects of a PD program for teachers with fewer years of education on two of the three quality measures. Other studies found no differential effects related to teacher education level or years of experience (Pianta, Mashburn et al., Citation2008; Zan & Donegan-Ritter, Citation2014). Overall, the evidence for the moderating effect of professional education or teacher experience on PD outcomes is inconsistent. Research on the influence of teacher education levels has indicated that factors beyond education alone are important in improving classroom quality (Early et al., Citation2007). Therefore, it seems to be a research concern to investigate additional intrapersonal characteristics of ECEC professionals (Sheridan, Edwards, Marvin, & Knoche, Citation2009), such as motivation and self-efficacy, as well as the work environment.

Motivational orientations of ECEC professionals

Motivational orientations are considered important for professional action because they are crucial for maintaining intentions, monitoring, and regulating educational practices over a long time (Baumert & Kunter, Citation2013). Based on a multidimensional understanding of motivation (Kunter, Citation2014), not only the quantity but also the quality of motivation needs to be accounted for. The multidimensionality of the motivation construct was addressed by Rzejak et al. (Citation2014) in a cross-sectional study (N = 102) by assessing different qualities of teachers’ motivation to participate in PD programs. It was found that the degree of motivation for social interaction with colleagues in the context of PD and the motivation to develop one’s professionalism and teaching were positively correlated with the degree of perceived effectiveness of PD in terms of the usefulness and implementability of PD content. In particular, human resource development (HRD) research has focused on the motivational orientations associated with learning transfer. In this context, transfer motivation is defined as the “direction, intensity, and persistence of effort toward utilizing in a work setting skills and knowledge learned” (Holton, Bates, & Ruona, Citation2000, p. 344). A meta-analysis showed that transfer motivation, along with expectancy and instrumentality, had the greatest effect on transfer (Gegenfurter, Citation2011). Furthermore, a meta-analytic path analysis demonstrated that motivational variables can affect learning outcomes beyond cognitive ability (Colquitt, LePine, & Noe, Citation2000).

In particular, self-efficacy is considered important because these beliefs influence one’s goals as well as one’s effort and perseverance for action and thus performance, and vice versa, the perceived quality of the individual’s performance can change self-efficacy beliefs (Hoeltge, Citation2018; Tschannen-Moran, Hoy, & Hoy, Citation1998). Some research findings suggest that the self-efficacy of ECEC professionals is related to the instructional support quality. A nonexperimental study indicated that ECEC professionals with higher self-efficacy ratings were more likely to provide higher quality literacy instruction (r = .20), but not higher quality language instruction (Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, & Pianta, Citation2008). Comparable results were revealed in a German cross-sectional study of ECEC professionals (N = 120), which found a positive relationship between the quality of instructional support and self-efficacy beliefs (Wolstein, Citation2021). In contrast to these findings, Hu, Guan, LoCasale-Crouch, Yuan, and Guo (Citation2022) found that the effect of a PD program was the strongest for those with low prior teacher efficacy scores, while it was the weakest for teachers with high scores of prior teacher efficacy. Other studies have failed to find correlations between self-efficacy and interaction quality (Guo, Piasta, Justice, & Kaderavek, Citation2010; Spear et al., Citation2018). Findings from HRD research confirm the positive relationship between (post-training) self-efficacy and the quality of implementation (Kauffeld, Bates, Holton, & Mueller, Citation2008) or transfer (Blume, Ford, Baldwin, & Huang, Citation2010).

Work environment: support from supervisor and colleagues

In addition to these individual characteristics of ECEC professionals that are considered important for transfer, the work environment in which the acquired competencies are to be implemented needs to be taken into account. On the one hand, the supervisor can play an essential role in the transfer process by encouraging the employee, providing feedback, and helping to identify appropriate situations in which to apply what has been learned (Elangovan & Karakowsky, Citation1999). Furthermore, it is assumed that supervisors can serve as role models and guide others in implementing high-quality practice (Whalley, Citation2011). On the other hand, colleagues can have a positive impact on one’s teaching practice and student achievement (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, Citation2008). Opportunities for professional learning can arise from conversations among colleagues discussing classroom experiences (Horn & Little, Citation2010) or from observing each other teaching (Supovitz, Sirinides, & May, Citation2010). Resa, Groeneveld, Turani, and Anders (Citation2017) have shown in their quasi-experimental study that professional exchange within the team contributes significantly to the development of language-related process quality. The importance of the work environment was demonstrated in a study of the transfer process of an in-service PD program for teachers (N = 129). It was found that particularly good transfer conditions, including sufficient time as well as support from colleagues and supervisors, could buffer the negative effects of low motivation on transfer (Dreer, Dietrich, & Kracke, Citation2017). These findings are consistent with HRD research results. The meta-analysis by Blume, Ford, Baldwin, and Huang (Citation2010) revealed a positive correlation between transfer and social support. Findings from individual survey studies contrast the supportive influence of supervisors and colleagues. They suggest that a perceived lack of collegial unity and cooperation (Stes, Clement, & Van Petegem, Citation2007) and low supervisor openness to new ideas (Piekarek, Citation2006) may be potential barriers.

Current study

Given the inconsistent findings on the differential effects of PD programs in ECEC, there is a need for high-quality studies to identify the conditions that lead to sustainable effects. Moreover, empirical knowledge on both facilitating and hindering transfer factors in the ECEC field is rather sparse. Therefore, a promising strategy is to build on findings from HRD research and transfer them to the ECEC field. Based on theoretical approaches in teacher development that refer to the same factors as in HRD research (such as the offer-and-use model by Lipowsky, (Citation2019), which is widely accepted in Germany), it can be assumed that the mechanisms of transfer in the field of education are comparable (Dreer, Dietrich, & Kracke, Citation2017). This suggests that factors such as transfer motivation, self-efficacy, and support from colleagues and supervisors may predict differences in PD effects.

This study examines the differential long-term effects of the PD program “Talking with Children” (TwC; German: “Mit Kindern im Gespräch,” Kammermeyer et al., Citation2017) on the instructional support quality of ECEC professionals. The first hypothesis states that the development of the instructional support quality differs between the treatment conditions from pretest to posttest, as well as from pretest to follow-up test. It is assumed that there is a more favorable change over time in the intervention condition than in the comparison condition. The second hypothesis is that the changes from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test in the quality of instructional support through participation in the PD program differ depending on the support from colleagues and supervisor. In the third hypothesis, we assume that the changes from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test in the quality of instructional support through participation in the PD program differ depending on the extent of transfer motivation and self-efficacy.

Method

Design

A pre-post-follow-up field study was conducted in which ECEC professionals (N = 50) were randomly assigned to the intervention condition or the comparison conditionFootnote1. In both conditions, nine days of training were provided between pretest and posttest (September 2014 to July 2015). Training sessions took place approximately once a month. In addition, both conditions received four half-day refresher sessions in the post-training year.

Intervention condition

The language-based PD approach “Talking with Children” (TwC; Kammermeyer et al., Citation2017) focuses on language promotion strategies to improve the quality of interactions in day care centers. The approach was developed in 2008 and has been the curriculum of the PD program for language promotion specialists in Rhineland-Palatinate (a federal state in Germany) since 2017. The PD approach consists of nine modules and 60 hours in which phases of input, practice, and reflection alternate. The aim is to support ECEC professionals in the acquisition of language promotion strategies and their application in everyday situations. Didactically, this PD approach is based on the concept of “situated learning.” This concept combines various individual didactic features (e.g., authentic learning situations, cooperative learning, reflection, and articulation) that contribute to the generation of flexible and transferable knowledge (Foelling-Albers, Hartinger, & Moertl-Hafizovic, Citation2004). This includes hands-on activities that allow participants to try out strategies in their pedagogical practice and to share ideas with other professionals. In addition to the training sessions, two one-hour individual coaching sessions were conducted based on videos of language promotion situations submitted by ECEC professionals. During these coaching sessions, the focus was on analyzing one’s behavior in the pedagogical setting, especially the use of strategies. These aspects were discussed together with one of the trainers and alternative courses of action were developed. This was intended to facilitate the transfer to one’s practice. Two research assistants involved in the development of the PD approach conducted all training sessions. However, the data was analyzed by the first author, who was not involved in the development of the PD approach.

Comparison condition

The comparison group received a PD approach based on a curriculum that has been mandatory in Rhineland-Palatinate since 2008 to qualify as a language promotion specialist (“Sprache – Schlüssel zur Welt;” Baltrusch et al., Citation2009). Until 2017, both PD programs (TwC and the alternative approach) were available. The alternative approach was broader in terms of content. The focus was on the acquisition of content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and professional action competence. The training sessions were conducted by two trainers with many years of experience in this PD approach. Conventional adult education methods such as lectures and discussions were used. The contents of the two PD programs are compared in .

Table 1. Content of the PD approaches.

Participants

The sample was recruited from ECEC professionals who were enrolled in the regular PD program for language promotion specialists at the largest regional training providers in Rhineland-Palatinate. All ECEC professionals agreed in advance to participate in either the regular or the alternative PD program leading to the same certificate. They were then randomly assigned to one of the two intervention groups or to the comparison group. There were 18 people in the comparison group and 16 people in each of the two intervention groups. All participants were female, except for one male participant in the intervention condition. Participants had completed training as educators or assistants, except for two individuals with academic degrees and one with missing information. Additional sociodemographic data are presented in .

Table 2. Sociodemographic data.

No demographic differences were found between the two intervention groups using Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon test. Since these groups (B1 and B2) received the same PD program with the same materials and the same trainers, and since the two groups were comparable in terms of structural conditions (group composition within the training and the premises), these two groups were combined as the intervention condition for further calculations. The models were made more parsimonious by including only the condition variable (binary).

Measures

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System Pre-K (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, Citation2008) was used as an observational measure of teacher-child interactions. In this study, CLASS served as the outcome assessment. The CLASS measure consists of 10 dimensions that are rated by certified observers using a 7-point Likert scale (low range: 1, 2; middle range: 3, 4, 5; high range: 6, 7) with three subscales: Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support. Two certified CLASS raters viewed and coded 20-minute videotapes. The rating process was blinded, meaning that the two raters did not know whether the videos were from the pre-, post-, or follow-up data, nor whether they were from the intervention or comparison condition. 20% of the project videos were double-coded using a calibration procedure to prevent observer drift. Overall, there was 95.3% agreement in the ratings of Instructional Support. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated for the dimensions Concept Development, Language Modeling, and Quality of Feedback and ranged from 0.74–0.87, indicating high inter-rater agreement.

The German Learning Transfer System Inventory (GLTSI, Kauffeld, Bates, Holton, & Mueller, Citation2008) is the German version of the Learning Transfer System Inventory (LTSI) by Holton, Bates, and Ruona (Citation2000). The GLTSI was used in this study to identify transfer-relevant factors that may be catalysts or barriers to the transfer of learning from training to the work context. The GLTSI is based on self-assessments by training participants. Ratings are given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). A theory-driven selection of items from the GLTSI was conducted. A total of 13 items were selected from the 51 items related to supervisor support, colleague support, transfer motivation, and self-efficacy. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Promax rotation was conducted to examine the dimensionality of the transfer-related factors. According to Holton, Bates, and Ruona (Citation2000), supervisor and colleague support refers to the extent to which supervisors or colleagues “support and reinforce use of training on the job” (pp. 344–345). Motivation to transfer learning is understood as “[t]he direction, intensity, and persistence of effort toward utilizing in a work setting skills and knowledge learned” (p. 344) and self-efficacy as “[a]n individual’s general belief that he is able to change his performance when he wants to” (p. 346).

Data collection procedures

From September to November 2014, prior to the intervention, language promotion interactions were videotaped for each participant (baseline). At the end of the intervention (May to July 2015), videos were videotaped again (posttest). During this period, participants completed the questionnaire. Follow-up data (videotapes) were collected one year later (May to June 2016). In the video recordings, the ECEC professionals were free to choose a language activity with an average of five children. The considerations regarding the number of children are related to the structural conditions in Germany, where additional language promotion was often provided in small groups at that time.

Data analysis procedures

Longitudinal multilevel analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses. First, a null model was specified to examine the proportion of the variance of instructional support quality at the between-person level (Model 0). Second, we included the predictor time to see if there were differential changes in the instructional support quality (Model 1). Third, the additional predictor intervention was included (Model 2) to test the cross-level interaction between intervention and time in the next step (Model 3). In the fourth step, we included work environment factors (support from colleagues and supervisor) to test the cross-level interaction between intervention and time and work environment (Model 4). In the last step, characteristics of the ECEC professionals (self-efficacy and transfer motivation) were included as predictors to test the cross-level interaction between intervention and time and characteristics of the ECEC professionals (Model 5).

All models were analyzed in RStudio (version 2022.12.0.353; Posit team, Citation2022) with the nmle package (Pinheiro et al., Citation2023) using restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML). REML provides less biased estimates, especially when the number of clusters is small (Hox, Moerbeek, & van de Schoot, Citation2018).

Results

Descriptive statistics

A total of seven ECEC professionals (14% of the original sample) left the study between pretest and follow-up test. The reasons for dropping out were changes in employment, pregnancy, and illness. Of these ECEC professionals, one was assigned to TwC and six were assigned to the comparison condition. Pretest scores on the CLASS domain Instructional Support for the seven ECEC professionals were compared with pretest scores for the 43 ECEC professionals for whom pretest, posttest and follow-up scores were available. No significant differences in pretest scores were found between participants who dropped out and those who remained in the study. These seven ECEC professionals were excluded from all further analyses.

shows the descriptive statistics of the variable Instructional Support with its dimensions Language Modeling, Concept Development, and Feedback Quality, which were measured with the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) by Pianta, La Paro, and Hamre (Citation2008). It is shown that participants in the comparison condition had baseline scores on the quality of instructional support that were approximately half a point lower than participants in the intervention condition. Follow-up scores in the intervention condition were more than one scale point (on a scale of 1 to 7) higher than in the comparison condition.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics: instructional support quality.

A descriptive analysis of the transfer-relevant factors shows that colleague support is in the middle range in both conditions (on a five-point Likert scale). Supervisor support for the transfer of what was learned in the PD program is slightly lower. This low level is equally noticeable in both conditions. Transfer motivation and self-efficacy are high in both conditions. There is little variance (SD < 0.7) in participants’ responses to these two variables (see ).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics: transfer-relevant factors (post-intervention).

Longitudinal effects on instructional support quality

The intraclass correlation (ICC) was calculated based on the null model. Results indicate that 18.5% of the total variance was due to between-person differences in the quality of instructional support. Therefore, a multilevel analysis was conducted to examine whether there were interindividual differences in changes in instructional support over time, with time (D1 fixed at post data point, D2 fixed at follow-up data point) as the first level predictor (Model 1). The predictors time D1 (b = 1.09, p < .001) and time D2 (b = 1.24, p < .001) were statistically significant, indicating an increase from pretest to posttest as well as an increase from pretest to follow-up test. Next, we tested for treatment effectiveness by including the predictor treatment in Model 2 and additionally including the interaction term treatment x time in Model 3. Results revealed that the main effect of treatment in Model 2 was statistically significant (b = 1.14, p < .001). The interaction effects of treatment x time D1 (b = 1.08, p < .05) and treatment x time D2 (b = 0.99, p < .05) in Model 3 were also statistically significant. These results indicate the effectiveness of the TwC approach, as the improvement from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test was greater than in the comparison condition (see ).

Table 5. Multilevel modeling results: instructional support quality.

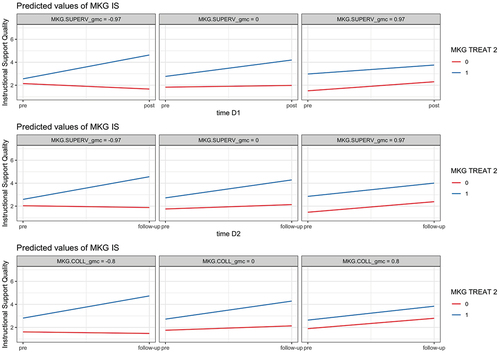

Differential effects of the PD program by transfer conditions

In Model 4, the predictors supervisor support and colleague support were included to test whether changes from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test in the quality of instructional support from participation in PD programs differed by colleague and supervisor support. These predictors were included at Level 2 and centered around the grand mean. Results indicate a statistically significant negative interaction between time D1 and treatment and supervisor support (b = − 1.09, p < .05; see ). This finding demonstrates that those who reported minimal supervisor support for transferring what they learned in PD made greater gains from pretest to posttest as a result of participating in the TwC approach, compared to those who reported higher supervisor support. The interaction terms of time D1/time D2 and treatment remained statistically significant (b = 1.25, p < .05; b = 1.15, p < .01).

Table 6. Multilevel modeling results: instructional support quality and transfer conditions.

In Model 5, the predictors self-efficacy and transfer motivation were included to test the influence of the characteristics of ECEC professionals. These predictors were included at Level 2 and centered around the grand mean. Neither the main effect of the predictors self-efficacy and transfer motivation nor the interaction effects between these predictors and time and treatment were statistically significant. However, the interaction terms of time D1/time D2 and treatment remain statistically significant (b = 1.10, p < .05; b = 1.06, p < .05).

Model 6 included all predictors of the work environment and the characteristics of the ECEC professionals. Results revealed a statistically significant negative main effect of supervisor support (b = −0.51, p < .05). Furthermore, the interaction effects between time D1/time D2 and treatment and supervisor support were statistically significant. The negative interaction effect indicates that individuals who reported minimal supervisor support made greater gains from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test through their participation in the TwC approach than those who reported higher supervisor support (b = −1.32, p < .05; b = −0.98, p < .05; see ). The results also suggest that there was a negative interaction effect between time D2 and treatment and reported colleague support (b = −1.10, p < .05; see also ). This interaction effect was not statistically significant for time D1, i.e., the development from pretest to posttest. As in Models 4 and 5, the interactions between time D1/time D2 and treatment in Model 6 were positive and statistically significant (b = 1.27, p < .05; b = 1.19, p < .01).

Determining effect sizes

The effect sizes were calculated according to Rights and Sterba (Citation2019) based on linear models.Footnote2 Model 1 with the single predictor time explained a total of 40.5% of the variance, with 14.9% explained by the predictor time and 25.6% by random intercepts. Model 3 with the interaction effect time x treatment explained a total of 43.2% of the variance, with 33.9% explained by all predictors (time, treatment) and 9.2% by random intercepts. Model 4 with the additional predictors colleague and supervisor support explained a total of 46.6% of the variance (38.3% by predictors and 8.3% by random intercepts) and Model 5 with the additional predictors transfer motivation and self-efficacy explained a total of 44.2% of the variance (35.6% by predictors and 8.6% by random intercepts). The overall model with all predictors explained a total of 48.4% of the variance, with 40.4% explained by the predictors and 8.0% by random intercepts.

Discussion

The present study investigated the differential long-term effects of a language-based PD program for ECEC professionals on the quality of instructional support. It was examined whether the TwC approach is equally effective for all ECEC professionals and whether the conditions of the work environment and the characteristics of the ECEC professionals play a role in the transfer of the acquired competencies from the PD program to pedagogical practice. This was accomplished by adopting transfer approaches from organizational psychology and applying them to the ECEC field. The question of whether changes from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up differ between treatment conditions can be answered based on the experimental design of the study. It has been shown that there are more favorable developments in the quality of instructional support in the treatment condition than in the comparison condition, both from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up test. This result demonstrates the overall effectiveness of the TwC approach.

Interesting results emerged regarding the differential effects due to colleague and supervisor support. The study revealed that individuals who reported minimal supervisor support in transferring what they learned in PD made greater gains from pretest to posttest and follow-up test through participation in the TwC approach compared to those who reported higher supervisor support. A similar picture emerges for colleague support, but only for the development from pretest to posttest. This finding suggests that the acquired language promotion strategies can be implemented and increase instructional support quality even when they perceive minimal support from colleagues and supervisors. Given the assumption that interactions between ECEC professionals and children are positively influenced by team quality (Wertfein, Mueller, & Danay, Citation2013), the result seems rather counterintuitive. It is conceivable that professionals who perceive minimal support from colleagues or supervisors in implementing language promotion strategies may use their experiences with children as feedback that reinforces the use of these strategies. The importance of the perceived response from children to the use of strategies learned in PD has also been emphasized in qualitative studies (Kämpfe, Betz, & Kucharz, Citation2021). Furthermore, PD programs may provide an additional setting in which professional exchange can take place. This assumption is supported by research showing that the opportunity for social interaction is a motive for participation in PD programs (Rzejak et al., Citation2014). This argument is plausible, as many opportunities for exchange and collaboration were created within the TwC approach. However, exchange with colleagues and supervisors from one’s own institution was not an explicit focus of the PD approach. It should also be noted that only one ECEC professional per institution was trained, not other team members. Therefore, it is also conceivable that participants in the TwC program, especially those who perceived minimal support, did not experience dissonance from their supervisors or colleagues who used other forms of language education with children. The role of colleagues and supervisors in the implementation of acquired competencies needs to be further investigated, as support was rather low in both conditions. The identification of supportive structures is a major concern, especially considering the low quality of instructional support in the ECEC field (Eckhardt & Egert, Citation2017; Hu, Dieker, Yang, & Yang, Citation2016; Peisner-Feinberg, Schaaf, Hildebrandt, & Pan, Citation2015).

While interactions with treatment and time were found for colleague and supervisor support, transfer motivation and self-efficacy of ECEC professionals did not have a significant impact on PD effects. Given these findings, it can be assumed that all ECEC professionals benefit equally from the PD program, regardless of how motivated or self-efficacious they perceive themselves to be. The low variance in the self-efficacy variable was a striking finding (see ). This could be because the PD program increased the self-efficacy of all professionals, and therefore there was little difference between the professionals after the PD program. The assumption of a reciprocal effect, i.e., self-efficacy as a cause and consequence of the PD program, is supported by research findings (Holzberger, Philipp, & Kunter, Citation2013). A reciprocal effect could not be investigated in the present study because self-efficacy and transfer motivation were measured only once (after the training). However, it can be argued that, in contrast to the context effects, the motivational characteristics of the professionals are less stable and more subject to change.

Overall, the results indicate that the TwC approach is effective and that language promotion strategies can be implemented even with minimal perceived support from colleagues and supervisors. This finding is remarkable because the implementation of language education integrated into daily routines seems to be more challenging than additive language education programs, which are generally based on pre-prepared materials and a manual. In contrast, the creation of spontaneous language stimuli is fundamental to integrated language interventions (Resa, Groeneveld, Turani, & Anders, Citation2017). This includes, for example, asking open-ended questions, self- and parallel-talk, and communication extensions (Kammermeyer et al., Citation2017). Given the high demands on ECEC professionals to implement child-centered approaches (Walsh, McGuinness, Sproule, & Trew, Citation2010), high-quality in-service PD programs have proven to be particularly effective interventions for implementing such approaches. The results of this study, which emphasize the importance of PD programs for improving the quality of instructional support, are consistent with recent findings from various meta-analyses of PD programs from different nations (Egert, Dederer, & Fukkink, Citation2020; Lee & Sung, Citation2023; Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017; Werner, Linting, Vermeer, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2016).

Study limitations

When interpreting the results, the limited sample size (N = 50) must be taken into account. It is therefore difficult to draw conclusions about the population. However, the present study is characterized by an experimental study design, which has a high ecological validity due to the field research approach. Furthermore, it remains unclear how the two hours of individual coaching affected the development of ECEC professionals’ instructional support. Since there was no experimental variation of PD formats (e.g., coursework, coaching), it is not possible to assess the contribution of individual coaching in terms of effects in the present study. These aspects will be addressed in a current research project on improving the quality of instructional support through different PD formats using the TwC approach by further investigating the promising results on a broader empirical basis. Another limitation is the one-time measurement of transfer factors, which does not adequately account for the potential interaction between the PD program and the transfer factors (especially motivation and self-efficacy). Contextual factors, i.e., support from supervisors and colleagues, are likely to be more stable. In this context, it remains unclear how initial conditions in terms of participants’ transfer factors affect the implementation of language promotion strategies in pedagogical practice.

Conclusions

The present study investigated the differential long-term effects of the TwC approach. Particular attention was paid to transfer-relevant factors, taking into account both the characteristics of ECEC professionals and the work environment. The results suggest that (1) the TwC approach is equally effective for all professionals, and (2) the strategies learned in the PD program can be implemented even with minimal perceived support from colleagues and supervisors. It is noteworthy that motivational factors (transfer motivation and self-efficacy) were not found to be significant. This finding should be further investigated in larger studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All study participants provided informed consent, and the study design was approved by the appropriate ethics review board.

2. Calculation of effect sizes based on the contrast models (where time was fixed at the post- or follow-up data point) was not possible because there was no level 1 residual. For linear models 1 to 6, the same predictors were used with the same centering methods as in the contrast models.

References

- Autorengruppe Fachkräftebarometer. (2017). Fachkräftebarometer Frühe Bildung 2017. Weiterbildungsinitiative Frühpädagogische Fachkräfte. https://www.fachkraeftebarometer.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikation_FKB2017/Fachkraeftebarometer_Fruehe_Bildung_2017_web.pdf

- Baltrusch, C., Dietsch, K., Kieferle, C., Knisel-Scheuring, G., Lattschar, B., Rausch, M., and Vanderheiden, E. 2009. Sprache – Schlüssel zur Welt: Materialien zur Qualifizierung von Sprachförderkräften in Rheinland-Pfalz. [Language – the key to the world: Materials for the qualification of language promotion specialists in Rhineland-Palatinate]. Katholische Erwachsenenbildung Rheinland-Pfalz Landesarbeitsgemeinschaft.

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2013). Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften [Professional competence of teachers]. In I. Gogolin, H. Kuper, H. H. Krueger, & J. Baumert (Eds.), Stichwort: Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft (pp. 277–337). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., & Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of training: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1065–1105. doi:10.1177/0149206309352880

- Bryant, D. M., Wesley, P. W., Burchinal, M., Sideris, J., Taylor, K., Fenson, C., & Iruka, I. U. (2009). The QUINCE-PFI study: An evaluation of a promising model for child care provider training: Final report. FPG Child Development Institute, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://www.researchconnections.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rc18531.pdf

- Buysse, V., Winton, P. J., & Rous, B. (2009). Reaching consensus on a definition of professional development for the early childhood field. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 28(4), 235–243. doi:10.1177/0271121408328173

- Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 678–707. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.678

- Dickinson, D. K., & Caswell, L. (2007). Building support for language and early literacy in preschool classrooms through in-service professional development: Effects of the literacy environment enrichment program (LEEP). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(2), 243–260. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.03.001

- Dreer, B., Dietrich, J., & Kracke, B. (2017). From in-service teacher development to school improvement: Factors of learning transfer in teacher education. Teacher Development, 21(2), 208–224. doi:10.1080/13664530.2016.1224774

- Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Burchinal, M., Alva, S., Bender, R. H. … Zill, N. (2007). Teachers’ education, classroom quality, and young children’s academic skills: Results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development, 78(2), 558–580. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01014.x

- Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Ponder, B. D., & Pan, Y. (2017). Improving teacher-child interactions: A randomized controlled trial of making the most of classroom interactions and my teaching partner professional development models. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38(1), 57–70. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.08.005

- Eckhardt, A. G., & Egert, F. (2017). Prozess- und Interaktionsqualität in Kindertageseinrichtungen in Ost- und Westdeutschland: Eine explorative Studie [Process and interaction quality in day care centers in East and West Germany: An explorative study]. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung, 12(3), 361–366. doi:10.3224/diskurs.v12i3.07

- Egert, F., Dederer, V., & Fukkink, R. G. (2020). The impact of in-service professional development on the quality of teacher-child interactions in early education and care: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 29, 100309. Article 100309. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100309

- Egert, F., Fukkink, R. G., & Eckhardt, A. G. (2018). Impact of in-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(3), 401–433. doi:10.3102/0034654317751918

- Egert, F., & Kappauf, N. (2019). Wirksamkeit von Weiterbildungen für pädagogische Fachkräfte – ein schwieriges Unterfangen? [Effectiveness of in-service training for educational professionals – a difficult undertaking?]. Pädagogische Rundschau, 73(2), 139–154. doi:10.3726/PR022019.0013

- Elangovan, A. R., & Karakowsky, L. (1999). The role of trainee and environmental factors in transfer of training: An exploratory framework. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 20(5), 268–276. doi:10.1108/01437739910287180

- Foelling-Albers, M., Hartinger, A., & Moertl-Hafizovic, D. (2004). Situiertes Lernen in der Lehrerbildung [Situated learning in teacher education]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 50(5), 727–747.

- Fukkink, R. G., & Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 294–311. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.04.005

- Gegenfurter, A. (2011). Motivation and transfer in professional training: A meta-analysis of the moderating effects of knowledge type, instruction, and assessment conditions. Educational Research Review, 6(3), 153–168. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2011.04.001

- Guo, Y., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2010). Relations among preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom quality, and children’s language and literacy gains. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1094–1103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.005

- Hoeltge, L. (2018). Diagnostik und individuelle Förderung im Kindergarten: Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen und Wissen frühpädagogischer Fachkräfte [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Goethe University Frankfurt.

- Holton, E. F., Bates, R. A., & Ruona, W. E. A. (2000). Development of a generalized learning transfer system inventory. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11(4), 333–360. doi:10.1002/1532-1096.

- Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., & Kunter, M. (2013). How teachers’ self-efficacy is related to instructional quality: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 774–786. doi:10.1037/a0032198

- Horn, I. S., & Little, J. W. (2010). Attending to problems of practice: Routines and resources for professional learning in teachers’ workplace interactions. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 181–217. doi:10.3102/0002831209345158

- Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Ready to learn? children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 27–50. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.05.002

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & van de Schoot, R. (2018). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Hu, B. Y., Dieker, L., Yang, Y., & Yang, N. (2016). The quality of classroom experiences in Chinese kindergarten classrooms across settings and learning activities: Implications for teacher preparation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.001

- Hu, B. Y., Guan, L., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Yuan, Y., & Guo, M. (2022). Effects of the MMCI course and coaching on pre-service ECE teachers’ beliefs, knowledge, and skill. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 61(4), 58–69. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.05.008

- Justice, L. M., Mashburn, A. J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2008). Quality of language and literacy instruction in preschool classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 51–68. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.004

- Kammermeyer, G., King, S., Roux, S., Metz, A., Leber, A., Lämmerhirt, A., and Goebel, P. (2017). Mit Kindern im Gespräch (Kita): Strategien zur Sprachbildung und Sprachförderung von Kindern in Kindertageseinrichtungen [Talking with children. Strategies for language education and language promotion of children in day-care centers] (2nd ed.). Augsburg: Auer.

- Kämpfe, K., Betz, T., & Kucharz, D. (2021). Wirkungen von Fortbildungen zur Sprachförderung für pädagogische Fach- und Lehrkräfte [Effects of PD on language promotion for educators and teachers]. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 24, 909–932.

- Kauffeld, S., Bates, R., Holton, E. F., & Mueller, A. C. (2008). Das deutsche Lerntransfer-System-Inventar (GLTSI): psychometrische Überprüfung der deutschsprachigen Version [The German version of the Learning Transfer Systems Inventory (GLTSI): Psychometric validation]. Zeitschrift für Personalpsychologie, 7(2), 50–69. doi:10.1026/1617-6391.7.2.50

- Kunter, M. (2014). Forschung zur Lehrermotivation [Research on teacher motivation]. In E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, & M. Rothland (Eds.), Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf (pp. 698–711). Münster: Waxmann.

- Lee, J. Y., & Sung, J. (2023). Effects of in-service programs on childcare teachers’ interaction quality: A meta-analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 124, 104017. Article 104017. 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104017

- Lipowsky, F. (2019). Wie kommen Befunde der Wissenschaft in die Klassenzimmer? – Impulse der Fortbildungsforschung [How do findings from science get into classrooms? – Impulses from training reserach]. In C. Donie, F. Foerster, M. Obermayr, A. Deckwerth, G. Kammermeyer, G. Lenske, M. Leuchter, & A. Wildemann (Eds.), Grundschulpädagogik zwischen Wissenschaft und Transfer (pp. 144–161). Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Lohse-Bossenz, H., Bahn, M., Busch, J., & Brandtner, M. (2022). Unterschiede in der Reflexion pädagogischer Praxis erklären Unterschiede in der Wirksamkeit von Fortbildungsmaßnahmen zur frühen naturwissenschaftlichen Bildung [Differences in how pedagogical practice is reflected explain differences in the effectiveness of professional development courses in early science education]. Frühe Bildung, 11(1), 2–11. doi:10.1026/2191-9186/a000553

- Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C. B., Piasta, S. B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L. M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38(1), 97–115. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002

- Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A. … Howes, C. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732–749. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

- National Professional Development Center on Inclusion [NPDCI]. (2008). What do we mean by professional development in the early childhood field?. FPG Child Development Institute, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://npdci.fpg.unc.edu/sites/npdci.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NPDCI_ProfessionalDevelopmentInEC_03-04-08_0.pdf

- Oberhuemer, P. (2012). Fort- und Weiterbildung frühpädagogischer Fachkräfte im europäischen Vergleich: Eine Studie der Weiterbildungsinitiative Frühpädagogische Fachkräfte (WiFF). Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V. https://www.weiterbildungsinitiative.de/publikationen/detail/fort-und-weiterbildung-fruehpaedagogischer-fachkraefte-im-europaeischen-vergleich

- Oberhuemer, P., Schreyer, I., & Neuman, M. J. (2010). Professionals in early childhood education and care systems: European profiles and perspectives. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., Schaaf, J. M., Hildebrandt, L. M., & Pan, Y. (2015). Children’s pre-k outcomes and classroom quality in Georgia’s pre-K program: Findings from the 2013–2014 evaluation study. FPG Child Development Institute, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resource-files/GAPreKEval2013-2014%20Report.pdf

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS) manual, pre-K. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

- Pianta, R. C., Mashburn, A. J., Downer, J. T., Hamre, B. K., & Justice, L. (2008). Effects of web-mediated professional development resources on teacher-child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(4), 431–451. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.02.001

- Piekarek, S. (2006). Vom Lernen zum Anwenden: Transferuntersuchung der hochschuldidaktischen Weiterbildungsveranstaltung “Start in die Lehre“ [From learning to applying: Transfer study of the university didactic training course ”Start in die Lehre“]. Journal Hochschuldidaktik, 17(2), 8–10. doi:10.17877/DE290R-12920

- Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D., EISPACK Authors, Heisterkamp, S., Van Willigen, B., Ranke, J., & R Core Team. (2023). Package ‘nlme’ (Version 3.1-162) [Computer software]. https://svn.r-project.org/R-packages/trunk/nlme/

- Posit team (2022). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (version 2022.12.0.353) [Computer software]. https://www.rstudio.com/

- Resa, E., Groeneveld, I., Turani, D., & Anders, Y. (2017). The role of professional exchange in improving language-related process quality in daycare centres. Research Papers in Education, 33(4), 472–491. doi:10.1080/02671522.2017.1353671

- Rights, J. D., & Sterba, S. K. (2019). Quantifying explained variance in multilevel models: An integrative framework for defining R-squared measures. Psychological Methods, 24(3), 309–338. doi:10.1037/met0000184

- Rzejak, D., Künsting, J., Lipowsky, F., Fischer, E., Dezhgahi, U., & Reichardt, A. (2014). Facetten der Lehrerfortbildungsmotivation – eine faktorenanalytische Betrachtung [Facets of teachers’ motivation for professional development – Results of a factorial analysis]. Journal for Educational Research Online, 6(1), 139–159.

- Schachter, R. E. (2015). An analytic study of the professional development research in early childhood education. Early Education and Development, 26(8), 1057–1085. doi:10.1080/10409289.2015.1009335

- Sheridan, S. M., Edwards, C. P., Marvin, C. A., & Knoche, L. L. (2009). Professional development in early childhood programs: Process issues and research needs. Early Education and Development, 20(3), 377–401. doi:10.1080/10409280802582795

- Spear, C. F., Piasta, S. B., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Ottley, J. R., Justice, L. M., & O’Connell, A. A. (2018). Early childhood general and special educators: An examination of similarities and differences in beliefs, knowledge, and practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(3), 263–277. doi:10.1177/0022487117751401

- Stes, A., Clement, M., & Van Petegem, P. (2007). The effectiveness of a faculty training programme: Long-term and institutional impact. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(2), 99–109. doi:10.1080/13601440701604898

- Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., & May, H. (2010). How principals and peers influence teaching and learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 31–56. doi:10.1177/1094670509353043

- Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. doi:10.3102/00346543068002202

- Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004

- Walsh, G. M., McGuinness, C., Sproule, L., & Trew, K. (2010). Implementing a play-based and developmentally appropriate curriculum in Northern Ireland primary schools: What lessons have we learned? Early Years, 30(1), 53–66. doi:10.1080/09575140903442994

- Werner, C. D., Linting, M., Vermeer, H. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Do intervention programs in child care promote the quality of caregiver-child interactions? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prevention Science, 17(2), 259–273. doi:10.1007/s11121-015-0602-7

- Wertfein, M., Mueller, K., & Danay, E. (2013). Die Bedeutung des Teams für die Interaktionsqualität in Kinderkrippen [The importance of the team for the quality of interactions in day-care centers]. Frühe Bildung, 2(1), 20–27. doi:10.1026/2191-9186/a000073

- Whalley, M. (2011). Leadership of practice: The role of the early years professional. In M. Whalley & S. Allen (Eds.), Leading practice in early years settings (pp. 1–15). Exeter: Learning Matters.

- Wolstein, K. (2021). Selbstwirksam und kompetent? Zusammenhänge zwischen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen, Interaktionsverhalten und weiteren ausgewählten Kompetenzfacetten bei frühpädagogischen Fachkräften. [ Doctoral dissertation, University of Education Freiburg]. Publication Server of PH Freiburg. https://phfr.bsz-bw.de/files/895/2021_Dissertation_Katrin_Wolstein.pdf

- Zan, B., & Donegan-Ritter, M. (2014). Reflecting, coaching and mentoring to enhance teacher–child interactions in head start classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(2), 93–104. doi:10.1007/s10643-013-0592-7